Pediatric Variations of Nursing Interventions

GENERAL CONCEPTS RELATED TO PEDIATRIC PROCEDURES

Preparation for Diagnostic and Therapeutic Procedures

Subcutaneous and Intradermal Administration

Nasogastric, Orogastric, or Gastrostomy Administration

PROCEDURES FOR MAINTAINING RESPIRATORY FUNCTION

On completion of this chapter the reader will be able to:

Identify those instances in which informed consent is required and in which minors may be considered emancipated.

Identify those instances in which informed consent is required and in which minors may be considered emancipated.

Formulate general guidelines for preparing children for procedures, including surgery.

Formulate general guidelines for preparing children for procedures, including surgery.

Implement play in therapeutic procedures.

Implement play in therapeutic procedures.

List general strategies for enhancing compliance in children and families.

List general strategies for enhancing compliance in children and families.

Outline general hygiene and care procedures for hospitalized children.

Outline general hygiene and care procedures for hospitalized children.

Implement feeding techniques that encourage food and fluid intake.

Implement feeding techniques that encourage food and fluid intake.

Describe methods of reducing temperature of child with fever or hyperthermia.

Describe methods of reducing temperature of child with fever or hyperthermia.

Describe systems that can be used for infection control.

Describe systems that can be used for infection control.

Describe safe methods of administering oral, parenteral, rectal, optic, otic, and nasal medications to children.

Describe safe methods of administering oral, parenteral, rectal, optic, otic, and nasal medications to children.

Identify nursing responsibilities in maintaining fluid balance.

Identify nursing responsibilities in maintaining fluid balance.

Demonstrate correct procedures for postural drainage and tracheostomy care.

Demonstrate correct procedures for postural drainage and tracheostomy care.

Describe the procedures involved in providing nutrition via gavage, gastrostomy, and parenteral routes.

Describe the procedures involved in providing nutrition via gavage, gastrostomy, and parenteral routes.

Describe the procedures involved in administering an enema and ostomy care to children.

Describe the procedures involved in administering an enema and ostomy care to children.

GENERAL CONCEPTS RELATED TO PEDIATRIC PROCEDURES

Before undergoing any invasive procedure, the patient or the patient’s legal surrogate must receive sufficient information on which to make an informed health care decision. Informed consent should include the expected care or treatment, potential risks, benefits, alternatives, and what might happen if the patient chooses not to consent. To obtain valid informed consent, the following three conditions must be met:

1. The person must be capable of giving consent; he or she must be over the age of majority (usually age 18) and must be considered competent (i.e., possessing the mental capacity to make choices and understand their consequences).

2. The person must receive the information needed to make an intelligent decision.

3. The person must act voluntarily when exercising freedom of choice without force, fraud, deceit, duress, or other forms of constraint or coercion.

The patient has the right to accept or refuse any health care. If the patient is treated without consent, the hospital or health care provider may be charged with assault and held liable for damages.

Requirements for Obtaining Informed Consent

Written informed consent of the parent or legal guardian is usually required for medical or surgical treatment, including many diagnostic procedures. One universal consent is not sufficient. Separate informed permissions must be obtained for each surgical or diagnostic procedure, including major or minor surgery, diagnostic tests with an element of risk (e.g., bronchoscopy), and medical treatments with an element of risk (e.g., blood transfusion, radiotherapy).

Other situations that require parental consent include:

Photographs for medical, educational, or public use

Photographs for medical, educational, or public use

Removal of the child from the health care institution against medical advice

Removal of the child from the health care institution against medical advice

Postmortem examinations, except in unexplained deaths, such as sudden infant death, violent death, or suicide

Postmortem examinations, except in unexplained deaths, such as sudden infant death, violent death, or suicide

Decision making involving the care of older children and adolescents should include, to the extent feasible, the patient’s assent as well as that of the parents (see Evidence-Based Practice box). Assent means the child or adolescent has been informed about what will happen during the treatment or procedure and is willing to permit a health care provider to perform it. Assent should include the following elements:

Helping the patient achieve a developmentally appropriate awareness of the nature of his or her condition

Helping the patient achieve a developmentally appropriate awareness of the nature of his or her condition

Telling the patient what he or she can expect

Telling the patient what he or she can expect

Making a clinical assessment of the patient’s understanding

Making a clinical assessment of the patient’s understanding

Soliciting an expression of the patient’s willingness to accept the proposed procedure of care

Soliciting an expression of the patient’s willingness to accept the proposed procedure of care

Multiple methods should be used to provide information, including age-appropriate methods (e.g., videotapes, peer discussion, diagrams, and written materials). An assent form should be provided to each child to sign, and the child should keep a copy (Broome, 1999). By including children in the decision-making process and gaining their acceptance, staff members demonstrate respect for the child. Assent is not a legal requirement but an ethical one to protect the rights of children.

Eligibility for Giving Informed Consent

Informed Consent of Parents or Legal Guardians: Parents have full responsibility for the care and rearing of their minor children, including legal control over them. As long as children are minors, their parents or legal guardians are required to give informed consent before medical treatment is rendered or any procedure is performed. If parents are married to each other, consent from only one parent is required for nonurgent pediatric care. If the parents are divorced, consent usually rests with the parent who has legal custody (Berger and AAP Committee on Medical Liability, 2003). Parents also have a right to withdraw consent at any time.

Evidence of Consent.: Obtaining informed consent varies from state to state, and policies differ at each health care facility. It is the physician’s responsibility to explain the procedure, risks, benefits, and alternatives. The nurse witnesses the patient’s, parent’s, or legal guardian’s signature on the consent form and may reinforce what the patient has been told. A signed consent form is the legal document that signifies that the process of informed consent has occurred. If parents are unavailable to sign consent forms, verbal consent may be obtained via the telephone in the presence of two witnesses. Both witnesses record that informed consent was given and by whom. Their signatures indicate that they witnessed the verbal consent.

Informed Consent of Mature and Emancipated Minors.: State laws differ with regard to the so-called age of majority, the age at which a person is considered to have all the legal rights and responsibilities of an adult. In most states, 18 is the age of majority. Competent adults can give informed consent on their own behalf. An emancipated minor is one who is legally under the age of majority but is recognized as having the legal capacity of an adult under circumstances prescribed by state law, such as pregnancy, marriage, high school graduation, living independently, or military service.

Treatment Without Parental Consent.: Exceptions to requiring parental consent before treating minor children occur when children need urgent medical or surgical treatment and a parent is not readily available or refuses to give consent. For example, a child may be brought to an emergency department accompanied by a grandparent, child care provider, teacher, or others. In the absence of parents or legal guardians, persons in charge of the child may be given permission by the parents to give informed consent by proxy. In emergencies, including danger to life or the possibility of permanent injury, appropriate care should not be withheld or delayed because of problems obtaining consent (Berger and AAP Committee on Medical Liability, 2003; American Academy of Pediatrics, 2003). Efforts made to obtain consent should be documented.

Refusal to give consent can occur when the treatment, such as blood transfusions, conflicts with the parents’ religious beliefs. All states recognize such exceptions and have statutory procedures to permit treatment if the life or health of such a minor is in jeopardy or if delayed treatment would create a risk to the minor’s health. In most states evaluation for child abuse or neglect can occur without parental consent and without notification of the state prior to evaluation.

Adolescents, Consent, and Confidentiality.: The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) was passed to help protect and safeguard the security and confidentiality of a person’s health information. Because adolescents are not yet adults, parents have the right to make most decisions on their behalf and receive information. Adolescents, however, are more likely to seek care in a setting in which they believe their privacy will be maintained. All 50 states have enacted legislation that entitles adolescents to consent to treatment without their parents’ knowledge for one or more “medically emancipated” conditions, such as sexually transmitted infections, alcohol and drug abuse, and need for contraceptive advice (Anderson, Schaechter, and Brosco, 2005; Tillett, 2005). Consent to abortion is controversial, and statutes vary widely by state. State law preempts HIPAA regardless of whether that law prohibits, mandates, or allows discretion about a disclosure.

Informed Consent and Parental Right to the Child’s Medical Chart.: Some state statutes give parents the unrestricted right to a copy of children’s medical records. In states without statutes, the best practice is to allow parents to review or have a copy of minors’ charts under reasonable circumstances. Practitioners should avoid restrictive requirements such as review permitted only in the presence of a clinician. Rather, an appropriate practitioner should be available to answer any questions that parents may have during reviews.

PREPARATION FOR DIAGNOSTIC AND THERAPEUTIC PROCEDURES

Technologic advances and changes in health care have resulted in more pediatric procedures being performed in a variety of settings. Many procedures are both stressful and painful experiences. For most procedures the focus of care is psychologic preparation of the child and family. However, some procedures require the administration of sedatives or analgesics.

Psychologic Preparation

Preparing children for procedures decreases their anxiety, promotes their cooperation, supports their coping skills and may teach them new ones, and facilitates a feeling of mastery in experiencing a potentially stressful event. Many institutions have developed preadmission teaching programs designed to educate the pediatric patient and family by offering hands-on experience with hospital equipment, information about the procedure to be performed, and an overview of departments they may visit (Algren, Ireland, and Stewart, 1998). Preparatory methods may be formal, such as group preparation for hospitalization. Most preparation strategies used by nurses are informal, focus on providing information about the experience, and are directed at stressful or painful procedures. The most effective preparation includes providing sensory-procedural information and helping the child develop coping skills, such as imagery, distraction, or relaxation (Broome, Rehwaldt, and Fogg, 1998).

General guidelines for preparing children for procedures are described in Box 22-1, and age-specific guidelines that consider children’s developmental needs and cognitive abilities are presented in Box 22-2. In addition to these suggestions, nurses should consider the child’s temperament, existing coping strategies, and previous experiences. Children who are distractible and highly active, as well as those who are “slow to warm up,” may need individualized sessions that are shorter for the active child but more slowly paced for the shy child. Youngsters who tend to cope well may need more emphasis on using their present skills, whereas those who appear to cope less adequately can benefit from more time devoted to simple coping strategies, such as relaxing, breathing, counting, squeezing a hand, or singing.

Children differ in their “information-seeking dimension.” Some actively solicit information about the intended procedure, whereas others avoid information. Parents can often guide nurses in deciding how much information is enough, since parents know whether the child is typically inquisitive or satisfied with short answers. Asking older children their preferences about the amount of explanation is also important. Drawings may also be helpful in preparing children for procedures.

The exact timing of the preparation for a procedure varies with the child’s age and type of procedure. No exact guidelines govern timing, but in general the younger the child, the closer the explanation should be to the actual procedure to prevent undue fantasizing and worrying. With complex procedures, more time may be needed for assimilation of information, especially with older children. For example, the explanation for an injection can immediately precede the procedure for all ages, whereas preparation for surgery may begin the day before for young children and a few days before for older children (although older children’s preferences should be elicited).

Establish Trust and Provide Support.: The nurse who has spent time with and established a positive relationship with a child will usually find it easier to gain cooperation. If the relationship is based on trust, the child will associate the nurse with caregiving activities that give comfort and pleasure most of the time rather than discomfort and stress. If the nurse does not know the child, it is best to be introduced by another staff person whom the child trusts. The first visit with the child should not include any painful procedure and ideally should focus on the child first, then on the explanation of the procedure.

Parental Presence and Support.: Children need support during procedures, and for young children the greatest source of support is the parents. They represent security, safety, and comfort. Controversy exists regarding the role parents should assume during the procedure, especially if discomfort is involved. Parental presence is preferable, however, since it can reduce patient and parent anxiety and decrease the need for sedation (Nelson, 1999). The nurse should assess the parents’ preferences for assisting, observing, or waiting outside the room, as well as the child’s preference for parental presence. The child’s and parents’ choice should be respected. Parents who wish to stay should be given appropriate explanation about the procedure and coached about what to do, where to sit or stand, and what to say to help the child through the procedure. Simple instructions such as clarifying where parents can stand or sit in the room and positioning them where they have eye contact with the child provide support and lessen anxiety. Parents who do not want to be present or participate are supported in their decision and encouraged to remain close by so that they can be available to console the child immediately after the procedure. Parents should also know that someone will be with their child to provide support. Ideally, this person should inform the parents after the procedure about how the child did.

Provide an Explanation.: Age-appropriate explanations are one of the most widely used interventions for reducing anxiety in children undergoing procedures. Before performing a procedure, explain what is to be done and what is expected of the child. The explanation should be short, simple, and appropriate to the child’s level of comprehension. Long explanations may increase anxiety in a young child. When explaining the procedure to parents with the child present, the nurse uses language appropriate to the child because unfamiliar words can be misunderstood (see Nursing Care Guidelines box). If the parents need additional preparation, this is done in an area away from the child. Teaching sessions are planned at times most conducive to the child’s learning (e.g., after a rest period) and for the usual span of attention.

Special equipment is not necessary for preparing a child, but for young children who cannot yet think in concepts, using objects to supplement verbal explanation is important. Allowing children to handle actual items that will be used in their care, such as a stethoscope, sphygmomanometer, or oxygen mask, helps them develop familiarity with these items and reduces the threat often associated with their use. Miniature versions of hospital items such as gurneys and x-ray and intravenous (IV) equipment can be used to explain what the children can expect and permit them to safely experience situations that are unfamiliar and potentially frightening. Written and illustrated materials are also valuable aids to preparation.*

Physical Preparation.: One area of special concern is the administration of sedation and analgesia before stressful procedures. Refer to Chapter 7 for information on sedating children.

Performance of the Procedure

Supportive care continues during the procedure and can be a major factor in a child’s ability to cooperate. Ideally, the same nurse who explains the procedure should perform or assist with the procedure. Before beginning, all equipment is assembled and the room is readied to prevent unnecessary delays and interruptions that increase the child’s anxiety.

If possible, procedures should be performed in a special treatment room rather than the child’s hospital room. Traumatic procedures should never be performed in “safe” areas, such as the playroom. If the procedure is lengthy, avoid conversation that could be misinterpreted by the child. As the procedure is nearing completion, inform the child that it is almost over in language the child understands.

Expect Success.: Nurses who approach children with confidence and who convey the impression that they expect to be successful are less likely to encounter difficulty. It is best to approach a child as though cooperation is expected. Children sense anxiety and uncertainty in an adult and respond by striking out or actively resisting. Although it is not possible to eliminate such behavior in every child, a firm approach with a positive attitude tends to convey a feeling of security to most children.

Involve the Child.: Involving children helps to gain their cooperation. Permitting choices gives them some measure of control. However, a choice is given only in situations in which one is available. Asking children, “Do you want to take your medicine now?” leads them to believe they have an option and provides them with the opportunity to legitimately refuse or delay the medication. This places the nurse in an awkward, if not impossible, position. It is much better to state firmly, “It’s time to drink your medicine now.” Children usually like to make choices, but the choice must be one that they do indeed have (e.g., “It’s time for your medicine. Do you want to drink it plain or with a little water?”).

Many children respond to tactics that appeal to their maturity or courage. This also gives them a sense of participation and achievement. For example, preschool children will be proud that they can hold the dressing during the procedure or remove the tape. The same is true for the school-age child, who often cooperates with minimal resistance.

Provide Distraction.: Distraction is a powerful coping strategy during painful procedures (Algren and Algren, 1997). It is accomplished by focusing the child’s attention on something other than the procedure. Singing favorite songs, listening to music, counting aloud, or blowing bubbles to “blow the hurt away” are effective techniques.

For other nonpharmacologic interventions that may lessen discomfort, see Pain Management, Chapter 7.

Allow Expression of Feelings.: The child should be allowed to express feelings of anger, anxiety, fear, frustration, or any other emotion. It is natural for children to strike out in frustration or to try to avoid stress-provoking situations. The child needs to know that it is all right to cry. Behavior is children’s primary means of communication and coping and should be permitted unless it inflicts harm on them or those caring for them.

Postprocedural Support

After the procedure, the child continues to need reassurance that he or she performed well and is accepted and loved. If the parents did not participate, the child is united with them as soon as possible so that they can provide comfort.

Encourage Expression of Feelings.: Planned activity after the procedure is helpful in encouraging constructive expression of feelings. For verbal children, reviewing the details of the procedure can clarify misconceptions and garner feedback for improving the nurse’s preparatory strategies. Play is an excellent activity for all children. Infants and young children are given the opportunity for gross motor movement. Older children are able to vent their anger and frustration in acceptable pounding or throwing activities. Play-Doh is a remarkably versatile medium for pounding and shaping. Dramatic play provides an outlet for anger and places the child in a position of control, in contrast to the position of helplessness in the real situation. Puppets can also allow the child to communicate feelings in a nonthreatening way. One of the most effective interventions is therapeutic play, which includes well-supervised activities such as permitting the child to give an injection to a doll or stuffed toy to reduce the stress of injections (Fig. 22-1).

Provide Positive Reinforcement.: Children need to hear from adults that they know the youngsters did the best they could in the situation, no matter how they behaved. It is important for children to know that their worth is not being judged on the basis of their behavior in a stressful situation. Reward systems, such as earning stars, stickers, or a badge of courage, are appealing to children.

Returning to the child a short while after the procedure helps the nurse strengthen a supportive relationship. Relating with the child in a relaxed and nonstressful period allows him or her to see the nurse not only as someone associated with stressful situations but as someone with whom to share pleasurable experiences.

Use of Play in Procedures

The use of play is an integral part of relationships with children. As such, its value in specific situations is discussed throughout this book, such as in Chapter 21, in relation to hospitalization. Many institutions have elaborate and well-organized play areas and programs under the direction of child life specialists; other institutions have limited facilities. No matter what the institution provides for children, nurses can include play activities as part of nursing care. Play can be used to teach, express feelings, or achieve a therapeutic goal. Consequently, it should be included in preparing children for and encouraging their cooperation during procedures. Play sessions after procedures can be structured, such as directed toward needle play, or general, with a wide variety of equipment available for children to play with. Routine procedures such as measuring blood pressure and oral administration of medication may be of concern to children. Box 22-3 offers suggestions for incorporating play into nursing procedures and activities for the hospitalized child that facilitate learning and adjustment to a new situation.

SURGICAL PROCEDURES

Children experiencing surgical procedures require both psychologic and physical preparation. In general, psychologic preparation is similar to that previously discussed for any procedure and employs many of the same techniques used in preparing a child for hospitalization, such as films, books, brochures, play, and tours. However, some important differences exist. Even though children are asleep for the actual surgical intervention, they are subjected to numerous preoperative and postoperative procedures. Stress points before and after surgery include the admission process, blood tests, injection of preoperative medication (if prescribed), transport to the operating room, and the stay in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU).

Psychologic intervention consisting of systematic preparation, rehearsal of the forthcoming events, and supportive care at each of these points has been shown to be more effective than a single-session preparation or consistent supportive care without systematic preparation and rehearsal. Play is always an effective strategy in preparing children, and increased familiarity with medical procedures decreases anxiety.

Surprisingly little research has been conducted on children’s perception of the surgical experience and their fears of the event. Although fear of anesthesia is thought to be a major concern among children, little evidence exists. School-age children report few remembered events and even fewer fears. Those events recalled most often were riding to and arriving in the operating room, receiving the preoperative or induction injection, waking up in pain, and not being allowed to eat or drink. The most feared events were the preoperative injection and the mask on the face.

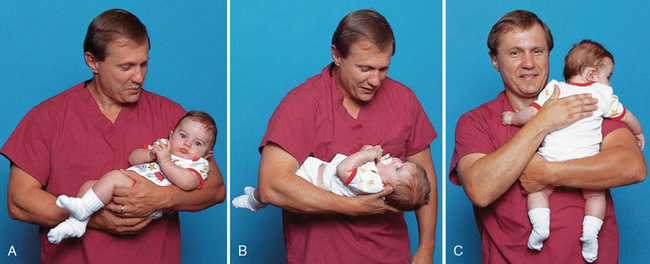

Parental presence during induction of anesthesia is allowed in some institutions (Fig. 22-2). Potential benefits include minimizing the need for premedication and reducing the struggle that often occurs during separation (Kain, Caldwell-Andrews, and Wang, 2002). Other benefits are controversial but may include decreasing the child’s anxiety during induction (e.g., breath holding and laryngospasm) and decreasing long-term behavioral effects of surgery (Romino, Keatley, Secrest, and others, 2005). Although few institutions endorse the policy, reports from parents who attend the induction are favorable (Kain, Caldwell-Andrews, Krivutza, and others, 2004). Even though some parents may become anxious, most control their anxiety, do not disrupt the induction, and support the child (Hall, Payne, Stack, and others, 1995; LaRosa-Nash and Murphy, 1997; Munro and D–Errico, 2000). Clinical observations show parental presence decreases anxiety in the child and reduces the need for heavy doses of preoperative sedation (Fennell, 1999).

FIG. 22-2 Parental presence during induction of anesthesia can minimize child’s and parents’ anxiety during the preoperative period.

Some concern exists regarding the appropriateness of this practice for all parents. Some parents may become upset by the rapid succession of induction events, by observing their child becoming limp, and by leaving the child in the care of strangers. Parents who are anxious before surgery tend to become even more anxious after the induction, whereas the reverse is true of parents with little anxiety.

However, based on the parents’ favorable response to the practice and most children’s desire to have parents with them during any stressful procedure, parents should have the option of attending the induction. Appropriate education is essential to help parents understand the stages of anesthesia, what to expect, and how to support their child (Fennell, 1999), combined with a program that prepares them for what to expect and what is expected of them. When parents choose not to or are not allowed to attend this induction, leaving a favorite possession with the child and uniting the child and parents as soon as possible after surgery (preferably in the PACU) are important interventions. During surgery the family should have a designated place to wait and should be kept informed of the child’s progress. They also should know where and when they can visit the child after surgery.

Aside from possibly being separated from the parents before and after surgery, children may be cared for by a number of unfamiliar practitioners, which promotes fear and uncertainty. Although the same supportive nurse should remain with the child through as many of the procedures as possible, the child may have other nurses, especially if the patient returns to a special care unit postoperatively. Many hospitals have surgical tours for children and parents to familiarize them with the strange environment and to introduce them to other individuals who will be involved in their care.

An important concern is restriction of food and fluids before surgery to avoid aspiration during anesthesia. Infants require special attention to fluid needs. They should not be without oral fluids for an extended period preoperatively to avoid glycogen depletion and dehydration. Current preoperative fasting guidelines are found in Table 22-1.

TABLE 22-1

Fasting Recommendations to Reduce the Risk of Pulmonary Aspiration*

| INGESTED MATERIAL | MINIMUM FASTING PERIOD (hours)† |

| Clear liquids‡ | 2 |

| Breast milk | 4 |

| Infant formula | 6 |

| Nonhuman milk§ | 6 |

| Light meal¶ | 6 |

*These recommendations apply to healthy patients who are undergoing elective procedures. They are not intended for women in labor. Following the guidelines does not guarantee a complete gastric emptying has occurred.

†Fasting periods noted in chart apply to all ages.

‡Examples of clear liquids include water, fruit juices without pulp, carbonated beverages, clear tea, and black coffee.

§Because nonhuman milk is similar to solids in gastric emptying time, the amount ingested must be considered when determining appropriate fasting period.

¶A light meal typically consists of toast and clear liquids. Meals that include fried or fatty foods or meat may prolong gastric emptying time. Both the amount and type of foods ingested must be considered when determining appropriate fasting period.

From American Society of Anesthesiologists: Practice guidelines for preoperative fasting and the use of pharmacologic agents to reduce the risk of pulmonary aspiration: application to healthy patients undergoing elective procedures, Anesthesiology 90(3):896-905, 1999; retrieved from http://www.asahq.org/publicationsAndServices/NPO.pdf.

Although most preoperative care procedures are routine, nurses should keep in mind that they can be anxiety provoking for children and parents. For example, wearing a hospital gown without the security of underpants or pajama bottoms can be traumatic. Therefore these articles of clothing should be allowed to be worn into the operating room and removed after induction of anesthesia.

Preoperative Sedation.: Historically the most upsetting event for children has been the preoperative injection. Significant increases have recently occurred in the number of anesthesiologists who use preoperative sedatives, usually midazolam (Versed), and parental presence for children undergoing surgery (Kain, Caldwell-Andrews, Krivutza, and others, 2004). When drugs are administered, they should be delivered atraumatically via oral or IV routes. Numerous preanesthetic drug regimens are used with children, and no consensus exists on the optimal method. The goals for using preoperative medications include (1) anxiety reduction, (2) amnesia, (3) sedation, (4) antiemetic effect, and (5) reduction of secretions (Landsman and Cook, 1998; Manworren and Fledderman, 2000). Midazolam provides excellent preoperative anxiety reduction, amnesia, and sedation. It is popular because of its short duration, predictable onset, and rare occurrence of respiratory depression. Oral transmucosal fentanyl (OTFC, or Oralet) is available as a sweetened lozenge on a plastic stick. When first approved, this appeared to be an excellent, atraumatic route of administration. However, associated nausea and vomiting, respiratory depression, and the need for more intensive monitoring and observation than with other oral sedatives have limited its popularity (Klein, Diekema, Paris, and others, 2002). If children have no preoperative pain, are well prepared psychologically for surgery, and have their parents nearby, preoperative medication may be unnecessary.

Anesthesia induction of the pediatric patient is commonly accomplished by administering inhalation agents in combination with nitrous oxide and oxygen by mask. Children may fear induction of anesthesia by mask. Practices that can minimize anxiety related to inhalation anesthesia are (1) disguising the unpleasant odor of anesthetic gases by applying a pleasant-smelling substance on the mask; (2) using a transparent plastic mask rather than an opaque black mask and gradually bringing it toward the face; (3) directing a stream of gas toward the child’s face from the bare tube until the child becomes drowsy, then using the mask; (4) allowing the child to sit up rather than lie down for anesthesia induction; and (5) allowing preoperative play with a mask and a doll or manikin.

Postoperative Care

Various psychologic and physical interventions and observations are required to prevent or minimize possible untoward effects from anesthesia and the surgical procedure (see Nursing Care Guidelines box). Although the incidence of serious postoperative complications in healthy children undergoing surgery is less than 1% (Maxwell and Yaster, 2000), continuous monitoring of cardiopulmonary status is essential during the immediate postoperative period. Postanesthesia complications such as airway obstruction, postextubation croup, laryngospasm, and bronchospasm make maintaining a patent airway and maximum ventilation critical.

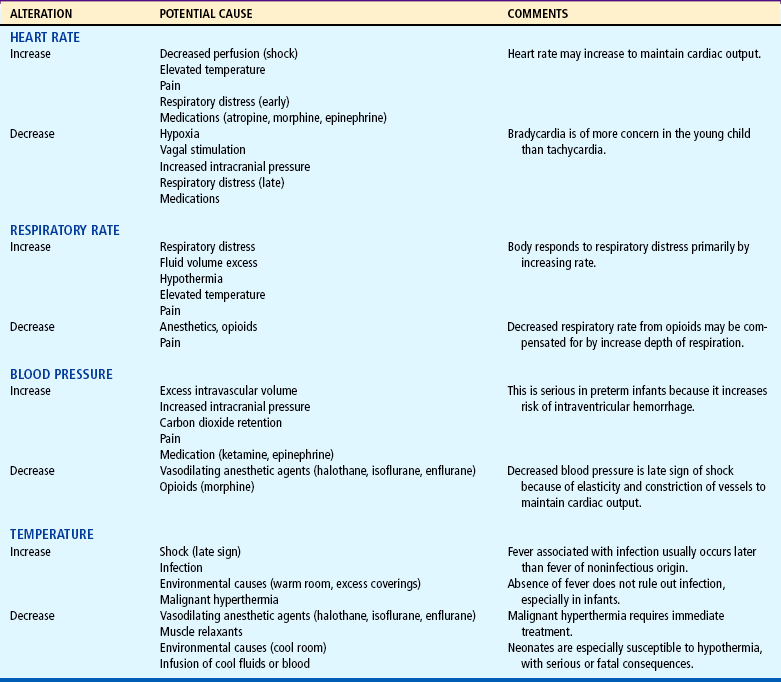

Monitoring oxygen saturation and providing supplemental oxygen as needed, maintaining body temperature, and promoting fluid and electrolyte balance are important aspects of immediate postoperative care. Vital signs are continuously monitored, and each vital sign is evaluated in terms of side effects from anesthesia, shock, or respiratory compromise (Table 22-2).

TABLE 22-2

Potential Causes of Postoperative Vital Sign Alterations in Children

From Smith DP: Comprehensive child and family nursing skills, St Louis, 1991, Mosby.

A change in vital signs that demands immediate attention in the perioperative period is caused by malignant hyperthermia (MH), a potentially fatal genetic myopathy. In susceptible children, anesthetics such as succinylcholine and halothane trigger the disorder, producing hypermetabolism, muscle rigidity, and an elevated temperature. Early symptoms of MH include tachycardia and tachyarrhythmias, tachypnea, hypercarbia, and metabolic and respiratory acidosis. An elevated temperature is considered by many to be a late sign of the disorder (Redmond, 2001). A family or previous history of sudden high fever associated with a surgical procedure and certain neuromuscular disorders increase risk for MH; children who have successfully undergone prior surgery without adverse effects may still be considered susceptible. Treatment includes immediate discontinuation of the triggering agent and surgical procedure, hyperventilation with 100% oxygen, and IV dantrolene sodium. Infusions of cool saline, cooling blankets, gastric or peritoneal lavage, packed ice bags in the axillae and groin, and, possibly, cardiopulmonary bypass reduce core temperature (Redmond, 2001). The patient should be transferred to an intensive care unit and closely monitored for stabilization of vital signs, metabolic state, and possible recurrence of symptoms.

Managing pain is a major nursing responsibility after surgery (see Chapter 7). The nurse should assess pain frequently and administer analgesics to provide comfort and facilitate cooperation with postoperative care such as ambulation and deep breathing. Opioids are the most commonly used analgesics. Routinely scheduled IV analgesics, patient-controlled analgesia, and epidural infusions, rather than as needed (PRN) orders, provide excellent analgesia in postoperative pediatric patients.

Because respiratory infections are a potential complication, every effort is taken to aerate the lungs and remove secretions. The lungs are auscultated regularly to identify abnormal sounds or any areas of diminished or absent breath sounds. To prevent hypostatic pneumonia, respiratory movement can be encouraged with incentive spirometers or other motivating activities (see Box 22-3). If these measures are presented as games, the child is more likely to comply. The child’s position is changed every 2 hours, and deep breathing is encouraged.

During the recovery period, some time should be spent with children to assess their perception of surgery. Play, drawing, and storytelling are excellent methods of discovering their thoughts. With such information the nurse can support or correct their perceptions and boost children’s self-esteem for having endured a stressful procedure.

COMPLIANCE

Compliance, also termed adherence, refers to the extent to which the patient’s behavior coincides with the prescribed regimen in terms of taking medication, following diets, or executing other lifestyle changes. In developing strategies to promote compliance, the nurse must first assess level of compliance. Because many children are too young to assume partial or total responsibility for their care, parents are usually primarily responsible for home management.

Factors relating to the care setting are important in ensuring compliance and should be considered in planning strategies to improve compliance. Basically, any aspect of the health care environment that increases the family’s satisfaction with the physical setting and the relationship with the practitioner positively influences adherence to the treatment regimen. However, the more complex, expensive, inconvenient, and disruptive the treatment protocol, the less likely the family is to comply. During long-term conditions that involve multiple treatments and considerable rearrangement of lifestyle, compliance is severely affected.

Although it is helpful to know those factors that influence compliance, assessment must include more direct measurement techniques. A number of methods exist, each with advantages and disadvantages. The most successful approach includes a combination of at least two of the following methods:

Clinical judgment—This is subject to bias and inaccuracy unless the nurse carefully evaluates the criteria used in assessment.

Self-reporting—Most people overestimate compliance by about 20% even when they admit to lapses.

Direct observation—This is difficult to employ outside the health care setting, and awareness of being observed frequently affects performance.

Monitoring appointments—Keeping appointments indirectly indicates compliance with the prescribed care.

Monitoring therapeutic response—Few treatments yield directly measurable results (e.g., decreased blood pressure, weight loss); record on a graph or chart.

Pill counts—The nurse counts the number of pills remaining in the original container and compares the number missing with the number of times the medication should have been taken. Families may forget to bring the container or deliberately alter the number of pills to avoid detection. This method is also poorly suited to liquid medication. Another technique is the use of pill container caps that record every opening as a presumptive dose.

Chemical assay—For certain drugs, such as digoxin and phenytoin, measurement of plasma drug levels provides information on the amount of drug recently ingested. However, this method is expensive, indicates only short-term compliance, and requires precise timing of the assay for accurate results.

Compliance Strategies

Strategies to improve compliance are composed of interventions that encourage families to follow the prescribed treatment regimen. Some evidence suggests that higher levels of self-esteem and increased autonomy favorably affect adolescent compliance (KyngAs, Kroll, and Duffy, 2000). However, family factors are important, and characteristics associated with good compliance include family support, family reminders, good communication, and expectations for successful completion of the therapeutic regimen (KyngAs, Kroll, and Duffy, 2000). No one approach is always successful, and the best results occur when at least two strategies are used.

Organizational strategies involve the care setting and the therapeutic plan. They include manipulating the factors listed in Box 22-4 that positively affect compliance. This may involve increasing the frequency of appointments, designating a primary practitioner, reducing the cost of medication by prescribing generic brands, reducing the treatment’s disruption of the family’s lifestyle, and using cues to minimize forgetting. Numerous devices are available commercially or can be improvised for cueing, such as pill dispensers; watches with alarms; charts to record completed therapy; messages on the refrigerator or morning coffee pot; and treatment schedules that incorporate the treatment plan into the daily routine, such as physical therapy after the evening bath.

Educational strategies instruct the family about the treatment plan. Although education is an important factor in enhancing compliance and patients who are more knowledgeable about their condition are more likely to comply, education alone does not ensure compliant behavior. The nurse should incorporate teaching principles known to enhance understanding and retention of material (see Nursing Care Guidelines box). Written materials are essential, especially in any regimen requiring multiple or complex treatments, and they need to be understandable to the average individual, who reads at about the fourth-grade level. Involvement of the immediate and extended family (e.g., grandparents) in education sessions may enhance compliance.

Treatment strategies relate to the child’s refusal or inability to take the prescribed medication. The family may also have difficulty following a prescribed treatment regimen. They may remember and understand the instructions but may not be able to give the medicine as prescribed. Assess the reason for refusal. For example, the child may not be able to swallow pills. In this case, perhaps pills can be crushed or a liquid medication substituted (always review medication to ensure that crushing is acceptable before giving this instruction).

Assess the treatment and medication schedule to determine if it is reasonable for a home situation. Although an every-6-hour or every-8-hour schedule is reasonable for hospitals, a parent would have difficulty getting up once or twice nightly; instead a medication could be given during the day at times that would be easy to remember.

Behavioral strategies are designed to modify behavior directly. Several strategies encouraging the desired behavior are effective with children. Ideally, positive reinforcement should be employed to strengthen the behavior and may consist of earning stars or tokens, which gains the child a special privilege or gift. At times, however, disciplinary techniques such as time-out for young children or withholding privileges for older children may be needed to improve compliance (see Limit Setting and Discipline, Chapter 3). Contracting, a formal process in which exact elements of desired behavior are explicitly outlined along with rewards or negative consequences, is an effective method with older children.

GENERAL HYGIENE AND CARE

MAINTAINING HEALTHY SKIN*

Maintaining an IV line, removing a dressing, positioning a child in bed, changing a diaper, using electrodes, and using restraints have the potential to contribute to skin injury. Skin care must go beyond the daily bath and become a part of each nursing intervention (see Nursing Care Guidelines box). Specific guidelines for skin care of neonates are provided in Skin Care, Chapter 9.

Assessment of the skin is most easily accomplished during the bath. Examine for early signs of injury. Risk factors include impaired mobility, protein malnutrition, edema, incontinence, sensory loss, anemia, infection, failure to turn the patient, and intubation. Critically ill children often are at higher risk of pressure ulcers and skin breakdown, since they often have several risk factors combined. Identification of risk factors helps to determine those children who need a more thorough skin assessment. Assessment should occur within 24 hours of admission so that pressure ulcers and wounds that occurred before admission can be identified (Ratliff and Rodheaver, 1999; Quigley and Curley, 1996).

When capillary blood flow is interrupted by pressure, the blood flows back into the tissue when the pressure is relieved. As the body attempts to reoxygenate the area, a bright red flush appears. This reactive hyperemia, or flush, is the earliest sign of tissue compromise and pressure-related ischemia. If pressure is prolonged, reactive hyperemia will not be sufficient to revitalize ischemic tissue (Calianno, 1999).

Staging of pressure ulcers is used to classify the amount of tissue damage.* Necrotic tissue must be removed so that the tissue depth can accurately be assessed. Accurate documentation of redness or obvious skin breakdown is essential. Color, size (diameter and depth), location, presence of sinus tracts, odor, exudate, and response to treatment are observed and recorded at least daily. (For treatment of wounds, see Chapter 30.)

Pressure ulcers can develop when the pressure on the skin and underlying tissues is greater than the capillary closing pressure, causing capillary occlusion. If the pressure remains unrelieved, vessels can collapse, resulting in tissue anoxia and cellular death. Pressure ulcers most often occur over bony prominences and are usually very deep, extending into subcutaneous tissue or even deeper into muscle, tendon, or bone. A pressure-reduction device reduces pressure but does not prevent pressure from causing capillary closure; therefore turning and repositioning are always included when using these devices. Most of these items are overlays that are placed on top of the regular mattress. A pressure-relief device maintains pressure below that which would cause capillary closure. These devices are usually high-technology beds that are used for patients who have multiple problems and cannot be turned effectively.

Friction and shear contribute to pressure ulcers. Friction occurs when the surface of the skin rubs against another surface, such as the bed sheets. Skin damage most often occurs over the elbows, heels, or occiput; is usually limited to the epidermal and upper layers; and may have the appearance of an abrasion. Prevention of friction injury includes the use of protective sheepskin over the elbows or heels; gel pillows under the head of infants and toddlers; moisturizing agents; transparent dressings over susceptible areas; and soft, smooth bed linen and clothing. Shear is the result of the force of gravity pushing down on the body and friction of the body against a surface, such as the bed or chair. For example, when a patient is in the semi-Fowler position and begins to slide to the foot of the bed, the skin over the sacral area remains in the same place because of the resistance of the bed surface. The blood vessels in the area are stretched and may cause small-vessel thrombosis and tissue death (Bryant and Doughty, 2000). Prevention of shear injury includes using lift sheets when repositioning a patient, elevating the bed no more than 30 degrees for short periods, and using the knee gatch to interrupt the pull of gravity on the body toward the foot of the bed.

Epidermal stripping results when the epidermis is unintentionally removed with tape removal. These lesions are usually shallow and irregularly shaped and may blister or weep. Babies are at increased risk for epidermal injury. Prevention includes using no tape when possible, securing dressings with laced binders (Montgomery straps) or stretchy netting (Spandage or stockinette). Using porous or low-tack tapes (e.g., Medipore, paper, hydrogel), using alcohol-free skin sealants (No Sting Barrier Film), or picture framing wounds with hydrocolloid or wafer barriers (e.g., DuoDERM, Coloplast, Stomahesive) and then taping on top of the barrier also will reduce epidermal stripping.

Tape is placed so that there is no tension, traction, or wrinkles on the skin. To remove tape, slowly peel the tape away while stabilizing the underlying skin. Adhesive remover may be used to break the adhesive bond but may be drying to the skin; adhesive removers should be avoided in preterm neonates, since absorption rates vary and toxicity may occur. The adhesive is removed with water to prevent absorption and irritation. Wetting the tape with water or alcohol-based foam hand cleansers may facilitate removal.

Chemical factors can also lead to skin damage. Fecal incontinence, especially when mixed with urine; wound drainage; or gastric drainage around gastrostomy tubes can erode epidermis. The skin can quickly progress from redness to denudement if exposure continues. Moisture barriers, gentle cleansing as soon after exposure as possible, and skin barriers can be used to prevent damage caused by chemical factors (see also Diaper Dermatitis, Chapter 30). In addition, foam dressings that wick moisture away from the skin are helpful around gastrostomy tubes and tracheostomy sites.

BATHING

Most infants and children can be bathed in a basin at the bedside, on the bed, or in a standard bathtub or shower. For infants and young children confined to bed, the towel method can be used. Two towels are immersed in a diluted soap solution and wrung damp. With the child lying supine on a dry towel, one damp towel is placed on top of the child and used to gently clean the body. This towel is discarded, and the child is dried and turned prone. The procedure is repeated using the second damp towel. Commercially available bath cloths may also be used.

Infants and small children are never left unattended in a bathtub, and infants who are unable to sit alone are securely held with one hand during the bath. The nurse should securely support the infant’s head with one hand, or grasp the farther arm firmly while the head rests comfortably on the nurse’s arm. Children who are able to sit without assistance need only close supervision and a pad placed in the bottom of the tub to prevent slipping and loss of balance.

School-age children and adolescents may shower or bathe. Nurses need to use judgment regarding the amount of supervision the child requires. Some can assume this responsibility unaided, whereas others will need someone in constant attendance. Children with cognitive impairments, physical limitations, or suicidal or psychotic problems (who may commit bodily harm) require close supervision.

Areas that require special attention are ears, between skinfolds, neck, back, and genital area. The genital area should be carefully cleansed and dried with particular care given to skinfolds, and in uncircumcised boys, usually those older than 3 years of age, the foreskin should be gently retracted, the exposed surfaces cleansed, and the foreskin then replaced. If the condition of the glans indicates inadequate cleaning, such as accumulated smegma, inflammation, phimosis, or foreskin adhesions, teaching proper hygiene is indicated. In the Vietnamese and Cambodian cultures the foreskin is traditionally not retracted until adulthood. Older children have the tendency to avoid cleaning the genitalia; therefore they may need a gentle reminder.

Children who are ill or debilitated need more extensive assistance with bathing, but should be encouraged to perform as much as they can without overtaxing their energies. Expect increasing involvement with improved strength and endurance.

ORAL HYGIENE

Mouth care is an integral part of daily hygiene and should be continued in the hospital. Infants and debilitated children require the nurse or a family member to perform mouth care. Although young children can manage a toothbrush and are encouraged to use it, most need assistance to perform satisfactorily. Older children, although capable of brushing and flossing without assistance, sometimes need to be reminded. (See Dental Health, Chapters 10 and 12, for specific oral hygiene techniques; mouth care of children with mucosal ulcers is discussed under nursing care of the child with leukemia in Chapter 26.)

HAIR CARE

Children should have their hair brushed and combed at least once daily. The hair is styled for comfort and in a manner pleasing to the child and parents. The hair should not be cut without parental permission, although clipping hair to provide access to a scalp vein for IV insertion may be necessary.

If children are hospitalized for more than a few days, the hair may need shampooing. With infants the hair may be washed during the daily bath or less frequently. For most children, washing the hair and scalp once or twice weekly is sufficient unless there is an indication for more frequent washing, such as following a high fever and profuse sweating. Adolescents normally have increased oily sebaceous secretions that require frequent hair care and more frequent shampoos.

Almost any child can be transported to an accessible sink for shampooing. Those who are unable to be transported can receive a shampoo in their beds with adequate protection, specially adapted equipment or positioning, or dry shampoo caps. When necessary, a shampoo basin may be used or the child may be positioned near the edge of the bed, towels placed under the shoulders, a large plastic garbage bag draped at the edge of the bed with one open end under the shoulders, and the hair placed inside the opening. The other end is opened and placed in a collection container. Water can be transported in a basin.

African-American children require special hair care. For the child with curly hair, most standard combs are inadequate and may cause hair breakage and discomfort. Use a special comb with widely spaced teeth. It is also much easier to comb the hair after shampooing when it is wet. Use a special hair dressing or pomade, which usually has a coconut oil base. The preparation is rubbed on the hands and then transferred to the hair to make it more pliable and manageable. Consult the parents regarding the preparation to use on their child’s hair and ask if they can provide some for use during the hospitalization. Petroleum jelly should not be used. If braiding or plaiting the hair, the nurse should weave it loosely while the hair is damp. The hair tightens as it dries, which could result in tension folliculitis.

FEEDING THE SICK CHILD

Loss of appetite is a symptom common to most childhood illnesses. Because an acute illness is usually short, the nutritional state is seldom compromised. Urging foods on the sick child may precipitate nausea and vomiting, and in most cases children can be permitted to determine their own need for food.

Refusing to eat may also be one way children can exert power and control in an otherwise helpless situation. For young children, loss of appetite may be related to the depression caused by separation from their parents. Parents’ concern with eating can intensify the problem. Forcing a child to eat meets with rebellion and reinforces the behavior as a control mechanism. Parents are encouraged to relax any pressure during an acute illness. Although it is best to encourage high-quality nutritious foods, the child may desire foods and liquids that contain mostly empty or nonnutritional calories. Some well-tolerated foods include gelatin, diluted clear soups, carbonated drinks, flavored ice pops, dry toast, and crackers. Even though these substances are not nutritious, they can provide necessary fluid and calories.

Dehydration is always a hazard when children are febrile or anorexic, especially when accompanied by vomiting or diarrhea. Offer small amounts of favored fluids at frequent intervals and provide salty foods (which increase thirst) if allowed. If diarrhea is present, avoid high-carbohydrate liquids (e.g., carbonated beverages, gelatin, flavored ice pops) because they may aggravate the diarrhea by an osmotic effect. Replacing abnormal losses with plain water or undiluted broth may worsen the electrolyte imbalance. Fluids should not be forced, and the child is not awakened to take fluids. Forcing fluids may create the same difficulties as urging unwanted food. Gentle persuasion with preferred beverages will usually meet with success. Using play techniques can also be very effective (see Nursing Care Guidelines box).

Once the child is feeling better, appetite usually begins to improve. It is best to take advantage of any hungry period by serving high-quality foods and snacks. If the child still refuses to eat, nutritious fluids, such as prepared breakfast drinks, should be encouraged. Parents can help by bringing in food items from home, especially if the family’s cultural eating habits differ from the hospital food. A clinical dietitian may also be consulted for alternative food choices.

When children are placed on special diets, such as clear liquids after surgery or during episodes of diarrhea, assessment of their intake and readiness to advance to more complex foods is essential. Regardless of the type of diet, charting of the amount consumed is an important nursing responsibility. Descriptions need to be detailed and accurate, such as “4 ounces of orange juice, one pancake, and 8 ounces of milk.” Comments such as “ate well” or “ate poorly” are inadequate. Charting the percentage of the meal eaten is also inadequate unless food is measured before serving.

If parents are involved in the child’s care, they are encouraged to keep a list of everything eaten. Using a premeasured cup for fluids ensures a more accurate estimate of intake. A comparison of the intake at each meal can isolate food deficiencies, such as insufficient intake of meat or vegetables. Behaviors associated with mealtime also may point to possible factors influencing appetite. For example, the observation that “child eats well when with other children but plays with food if left alone in room” helps the nurse plan mealtime activities that stimulate the appetite.

CONTROLLING ELEVATED TEMPERATURES

An elevated temperature, most frequently from fever but occasionally caused by hyperthermia, is one of the most common symptoms of illness in children. This manifestation is of great concern to parents. To facilitate an understanding of fever, the following terms are defined:

Set point—The temperature around which body temperature is regulated by a thermostat-like mechanism in the hypothalamus

Fever (hyperpyrexia)—An elevation in set point such that body temperature is regulated at a higher level; may be arbitrarily defined as temperature above 38° C (100.4° F)

Hyperthermia—Body temperature exceeding the set point, which usually results from the body or external conditions creating more heat than the body can eliminate, such as in heatstroke, aspirin toxicity, seizures, or hyperthyroidism

Body temperature is regulated by a thermostat-like mechanism in the hypothalamus. This mechanism receives input from centrally and peripherally located receptors. When temperature changes occur, these receptors relay the information to the thermostat, which either increases or decreases heat production to maintain a constant set point temperature. However, during an infection, pyrogenic substances cause an increase in the body’s normal set point, a process that is mediated by prostaglandins. Consequently, the hypothalamus increases heat production until the core temperature reaches the new set point.

Most fevers in children are of brief duration with limited consequences and are viral in origin. When fever is caused by bacteria, endotoxins are produced that activate the inflammatory process and produce fever (Rote, Huether, and McCance, 2000). Contrary to popular belief, neither the rise in temperature nor its response to antipyretics indicates the severity or etiology of infection, which casts doubt on the value of using fever as a diagnostic or prognostic indicator.

Therapeutic management of elevated temperature depends on whether it is due to a fever or hyperthermia. Because the set point is normal in hyperthermia but increased in fever, different approaches must be used to lower body temperature successfully.

Fever

The principal reason for treating fever is the relief of discomfort. Relief measures include pharmacologic or environmental intervention. The most effective intervention is the use of antipyretics to lower the set point.

Antipyretic drugs include acetaminophen, aspirin, and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Acetaminophen is the preferred drug; aspirin should not be given to children because of the association between aspirin use in children and influenza virus or chickenpox and Reye syndrome. One nonprescription NSAID, ibuprofen, is approved for fever reduction in children as young as 6 months of age. Dosage is based on the initial temperature level: 5 mg/kg of body weight for temperatures less than 39.2° C (102.6° F) or 10 mg/kg for temperatures greater than 39.2° C. The recommended dosage for pain is 10 mg/kg every 6 to 8 hours, and the recommended maximum daily dose for pain and fever is 40 mg/kg. The duration of fever reduction is generally 6 to 8 hours and is longer with the higher dose (see Chapter 6). It may be given every 4 hours but no more than five times in 24 hours. Because body temperature normally decreases at night, three or four doses in 24 hours will control most fevers. The nurse should retake the temperature 30 minutes after the antipyretic is given to assess its effect, but temperature should not be repeatedly measured; the child’s level of discomfort is the best indication for continued treatment.

Environmental measures to reduce fever may be used if tolerated by the child and if they do not induce shivering. Shivering is the body’s way of maintaining the elevated set point by producing heat. Compensatory shivering greatly increases metabolic requirements above those already caused by the fever.

Traditional cooling measures, such as wearing minimum clothing, exposing the skin to the air, reducing room temperature, increasing air circulation, and applying cool, moist compresses to the skin (e.g., the forehead), are effective if employed approximately 1 hour after an antipyretic is given so that the set point is lowered. Cooling procedures such as sponging or tepid baths are ineffective in treating febrile children (these measures are effective for hyperthermia) either when used alone or in combination with antipyretics, and they cause considerable discomfort (Sharber, 1997).

Seizures associated with a fever occur in 3% to 4% of all children, usually those 3 months to 5 years of age. Although most children never have febrile seizures after the first occurrence, a younger age at onset and a family history of febrile seizures are associated with recurring episodes (Berg, Shinnar, Levy, and others, 1999; Shinnar, Pellock, Berg, and others, 2001). There is little evidence to support the use of antipyretic drugs to prevent febrile seizures; nursing interventions should focus on ways to provide care and comfort during a febrile illness (Purssell, 2000).

Hyperthermia

Unlike fever, antipyretics are of no value in hyperthermia because the set point is already normal. Consequently, cooling measures are used. Cool applications to the skin help reduce the core temperature. Cooled blood from the skin surface is conducted to inner organs and tissues, and warm blood is circulated to the surface, where it is cooled and recirculated. The surface blood vessels dilate as the body attempts to dissipate heat to the environment and facilitate the cooling process.

Commercial cooling devices, such as cooling blankets or mattresses, are available to reduce body temperature. Place on the bed and cover with a sheet or lightweight blanket. Frequent temperature monitoring is essential to prevent excessive cooling of the body.

Traditionally, cool compresses have been used to decrease high temperature. For tepid tub baths it is usually best to start with warm water and gradually add cool water until the desired water temperature of 37° C (98.6° F) is reached to accustom the child to the lower water temperature. Generally, the temperature of the water only has to be 1° C or 2° F less than the child’s temperature to be effective. The child is placed directly in the tub of tepid water for 15 to 20 minutes while water is gently squeezed from a washcloth over the back and chest or gently sprayed over the body from a sprayer. In the bed or crib, cool washcloths or towels are used, exposing only one area of the body at a time. The sponging is continued for approximately 20 minutes. After the tub or sponge bath, the child is dried and dressed in lightweight pajamas, a nightgown, or a diaper and placed in a dry bed. The child is dried by gently rubbing the skin surface with a towel to stimulate circulation. The temperature is retaken 30 minutes after the tub bath or sponge bath. The tub or sponge bath should not be continued or restarted until the skin surface is warm or if the child feels chilled. Chilling causes vasoconstriction, which defeats the purpose of the cool applications. In this condition, little blood is carried to the skin surface; the blood remains primarily in the viscera to become heated.

Whether a temperature elevation in the critically ill child is caused by fever or hyperthermia, it should be treated aggressively. The metabolic rate increases 10% for every 1° C increase in temperature and three to five times during shivering, thus increasing oxygen, fluid, and caloric requirements. If the child’s cardiovascular or neurologic system is already compromised, these increased needs are especially hazardous. In all children with elevated temperature, attention to adequate hydration is essential. Most children’s needs can be met through additional oral fluids.

FAMILY TEACHING AND HOME CARE

Although most children have learned self-care and hygiene in the home or at school, many have not. For some young children, this is their first introduction to the use of a toothbrush. Much health teaching can be accomplished even when the child is hospitalized for only a short time. The daily bath, hand washing before meals and after bowel and bladder evacuation, and conscientious dental hygiene are taught during routine care. Clean hair, nails, and clothing and good grooming are emphasized as being essential to a pleasing appearance. Positive reinforcement of good hygiene practices helps create a positive body image, enhances self-esteem, and prevents health problems (e.g., teaching girls to wipe the genital area from front to back after toileting).

Although sick children’s appetites may be poor and not characteristic of their home eating habits, the hospital stay provides numerous opportunities for nurses to assess the family’s knowledge of good nutrition and to implement teaching as needed to improve nutritional intake.

Fever is one of the most common problems for which parents seek health care. Parental anxiety increases with temperature elevation and its management (Liebman and Barnsteiner, 2001). Parents need to know that sponging is indicated for elevated temperatures from hyperthermia rather than fever and that ice water and alcohol are inappropriate, potentially dangerous solutions (Axelrod, 2000). Parents should know how to take the child’s temperature and read the thermometer accurately and should have guidelines for seeking professional care (see Family-Centered Care box). Some of the newer temperature-measuring devices, such as plastic strips or digital thermometers, may be better suited for home use than hospital use (see Temperature, Chapter 6). If the use of acetaminophen or ibuprofen is indicated, the parents need instruction in administering the drug. Emphasize accuracy in both the amount of drug given and the time intervals at which the drug is administered.

SAFETY

Safety is an essential component of any patient’s care, but children have special characteristics that require an even greater concern for safety. Because small children in the hospital are separated from their usual environment and do not possess the capacity for abstract thinking and reasoning, it is the responsibility of everyone who comes in contact with them to maintain protective measures throughout their hospital stay. Nurses need to understand the age level at which each child is operating and plan for safety accordingly.

Identification bands are particularly important for children. Infants and unconscious patients are unable to tell or respond to their names. Toddlers may answer to any name or to a nickname only. Older children may exchange places, give an erroneous name, or choose not to respond to their own names as a form of joke, unaware of the hazards of such practices.

ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS

All of the environmental safety measures for the protection of adults apply to children, including good illumination, floors clear of fluid or objects that might contribute to falls, and nonskid surfaces in showers and tubs. All staff members should be familiar with the area-specific fire plan. Elevators and stairways should be made safe

All windows should be secured. Blind and curtain cords should be out of reach, with split cords to prevent strangulation.

Electrical equipment is maintained in good working order, is operated only by personnel familiar with its use, and is not in contact with moisture or situated near tubs. Electrical outlets should be provided with covers to prevent burns in small children, whose exploratory activities may extend to inserting objects into the small openings.

Staff members should practice proper care and disposal of small objects such as syringe caps, needle covers, and temperature probe covers (Fig. 22-3).

FIG. 22-3 To prevent needlestick injuries, used needles (and other sharp instruments) are not capped or broken and are disposed of in a rigid, puncture-resistant container located near the site of use. Note placement of the container to prevent children’s access to the contents.

Bathwater is carefully checked before placing the child in it, and children must never be left alone in a bathtub. Infants are helpless in water, and small children (and some older ones) may turn on the hot water faucet and be severely burned.

Furniture is safest when it is scaled to the child’s proportions, is sturdy, and is well balanced to prevent its being easily tipped over. A special hazard for children is the danger of entrapment under an electronically controlled bed when it is activated to descend. Infants and small children must be securely strapped into infant seats, feeding chairs, and strollers. Baby walkers should not be used because they provide access to hazards and can cause injuries by tipping over. Infants; young children; and those who are weak, paralyzed, agitated, confused, sedated, or cognitively impaired are never left unattended on treatment tables, on scales, or in treatment areas. Even preterm infants are capable of surprising mobility; therefore portholes in incubators must be securely fastened when not in use. Beds of ambulatory patients should remain locked in place and at a height that allows easy access to the floor.

Crib sides are kept up and fastened securely unless an adult is at the bedside. It is safer to leave crib sides up, regardless of the child’s ability to get out and even when the crib is unoccupied, to remove the child’s temptation to climb in. Anyone attending an infant or small child in a crib with the sides down should never turn away without maintaining hand contact with the child; that is, one hand should be kept on the child’s back or abdomen to prevent the child from rolling, crawling, or jumping from the open crib (Fig. 22-4). A child who is apt to or has demonstrated the inclination to climb over the sides of the crib is safest when placed in a specially constructed crib with a cover.

Toy Safety

Toys play a vital role in the everyday life of children, and they are no less important in the hospital setting. Nurses are responsible for assessing the safety of toys brought to the hospital by well-meaning parents and friends. Toys should be appropriate to the child’s age, condition, and treatment. For example, if the child is receiving oxygen, electrical or friction toys are not safe, since sparks can cause oxygen to ignite. Inspect toys to ensure they are nonallergenic, washable, and unbreakable and have no small, removable parts that can be aspirated or swallowed or in other ways injure a child. All objects within reach of children younger than 3 years should pass the choke tube test. A toilet paper roll is a handy guide. If a toy or object fits into the cylinder (items less than 1¼ inches across or balls smaller than 1¾ inches), it is a potential choking danger to the child. Latex balloons pose a serious threat to children of all ages. If the balloon breaks, a child may put a piece of the latex in his or her mouth. If it is aspirated or swallowed, the latex piece is difficult to remove, resulting in choking. Latex balloons should never be permitted in the hospital setting.

Preventing Falls

Multiple interventions are needed to minimize pediatric patients’ risk of falling. Once individual children are identified as at risk for falling, visual identification and communication of the risk among all health care providers is essential. Reduce the risk of falling through patient, family, and staff education.

1. Identify children at risk of falling. Perform a fall risk assessment on patients on admission and throughout hospitalization to identify patients at high risk for falls. Risk factors for hospitalized children include:

Medication effects–postanesthesia or sedation; analgesics or narcotics, especially in those who have never had narcotics in the past and in whom effects are unknown

Medication effects–postanesthesia or sedation; analgesics or narcotics, especially in those who have never had narcotics in the past and in whom effects are unknown

Altered mental status–secondary to seizures, brain tumors, or medications

Altered mental status–secondary to seizures, brain tumors, or medications

Altered or limited mobility–reduced skill at ambulation secondary to developmental age, disease process, tubes, drains, casts, splints, or other appliances; new to ambulation with assistive devices such as walkers or crutches

Altered or limited mobility–reduced skill at ambulation secondary to developmental age, disease process, tubes, drains, casts, splints, or other appliances; new to ambulation with assistive devices such as walkers or crutches

Postoperative children–risk of hypotension or syncope secondary to large blood loss, a heart condition, or extended bed rest

Postoperative children–risk of hypotension or syncope secondary to large blood loss, a heart condition, or extended bed rest

Infants or toddlers in cribs with side rails down or on the daybed with family members

Infants or toddlers in cribs with side rails down or on the daybed with family members

2. Visually identify patients at risk with one or more of the following:

Post signs on the door and at the bedside.

Post signs on the door and at the bedside.

Apply a special colored armband labeled “Fall Precautions.”

Apply a special colored armband labeled “Fall Precautions.”

Keep bed in lowest position, breaks locked, and side rails up.

Keep bed in lowest position, breaks locked, and side rails up.

Ensure that all necessary and desired items are within reach (e.g., water, glasses, tissues, snacks).

Ensure that all necessary and desired items are within reach (e.g., water, glasses, tissues, snacks).

Offer toileting on a regular basis, especially if patient is taking diuretics or laxatives.

Offer toileting on a regular basis, especially if patient is taking diuretics or laxatives.

Keep lights on at all times, including dim lights while sleeping.

Keep lights on at all times, including dim lights while sleeping.

Lock wheelchairs before transferring patients.

Lock wheelchairs before transferring patients.

Ensure that patient has appropriate size gown and nonskid footwear. Do not allow gowns or ties to drag on the floor when ambulating.

Ensure that patient has appropriate size gown and nonskid footwear. Do not allow gowns or ties to drag on the floor when ambulating.

Keep floor clean and free of clutter. Post “wet floor” sign if floor is wet.

Keep floor clean and free of clutter. Post “wet floor” sign if floor is wet.

Ensure that patient has glasses on if he or she normally wears them.

Ensure that patient has glasses on if he or she normally wears them.

4. Educate patients (as age appropriate):

Assist with ambulation even though the child may have ambulated well before hospitalization.

Assist with ambulation even though the child may have ambulated well before hospitalization.

Patients who have been lying in bed will need to get up slowly, sitting on the side of the bed before standing.

Patients who have been lying in bed will need to get up slowly, sitting on the side of the bed before standing.

Call the nursing staff for assistance, and do not allow patients to get up independently.

Call the nursing staff for assistance, and do not allow patients to get up independently.

Keep the side rails of the crib or bed up whenever patient is in the crib or bed.