Oxidative Metabolism of Lipids in Liver and Muscle

Introduction

Fats are normally the major source of energy in liver and muscle, and in other tissues, with two exceptions: brain and red cells

Triglycerides are the storage and transport form of fats; fatty acids are the immediate source of energy. Fatty acids are released from triglyceride stores in adipose tissue, transported in plasma in association with albumin, and delivered to cells for metabolism. The catabolism of fatty acids is entirely oxidative; after they have been transported through the cytoplasm, their oxidation proceeds in both the peroxisome and the mitochondrion, primarily by a cycle of reactions known as β-oxidation. Carbons are released, two at a time, from the carboxyl end of the fatty acid; the major end products are acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) and the reduced forms of the nucleotides FADH2 and NADH. In muscle, the acetyl-CoA is metabolized via the tricarboxylic acid cycle and oxidative phosphorylation to produce ATP. In liver, acetyl-CoA is converted largely to ketone bodies (ketogenesis), which are water-soluble lipid derivatives that, like glucose, are exported for use in other tissues. Fat metabolism is controlled primarily by the rate of triglyceride hydrolysis (lipolysis) in adipose tissue, which is regulated by hormonal mechanisms involving insulin and glucagon, epinephrine, and cortisol. These hormones coordinate the metabolism of carbohydrate, lipid and protein throughout the body (see Chapter 21).

Activation of fatty acids for transport into the mitochondrion

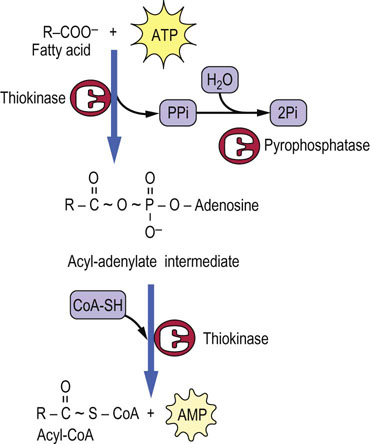

Fatty acids are activated by formation of a high energy thioester bond with Coenzyme A

Fatty acids do not exist to a significant extent in free form in the body – salts of fatty acids are soaps; they would dissolve cell membranes. In blood, fatty acids are bound to albumin, which is present at ∼0.5 mmol/L concentration (35 mg/mL) in plasma. Each molecule of albumin can bind 6–8 fatty acid molecules. In the cytosol, fatty acids are bound to a series of fatty acid-binding proteins and enzymes. As the priming step for their catabolism, the fatty acids are activated to their CoA derivative, using ATP as the energy source (Fig. 15.1). The carboxyl group is first activated to an enzyme-bound, high-energy acyl-adenylate intermediate, formed by reaction of the carboxyl group of the fatty acid with ATP. The acyl group is then transferred to CoA by the same enzyme, fatty acyl-CoA synthetase. This enzyme is commonly known as fatty acid thiokinase, because ATP is consumed in the formation of the thioester bond in acyl-CoA.

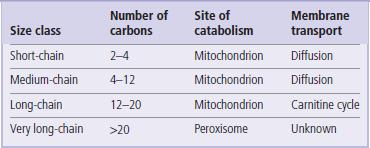

The length of the fatty acid dictates where it is activated to CoA

Short- and medium-chain fatty acids (Table 15.1) can cross the mitochondrial membrane by passive diffusion, and are activated to their CoA derivative within the mitochondrion. Very long-chain fatty acids from the diet are shortened to long-chain fatty acids in peroxisomes. Long-chain fatty acids are the major components of storage triglycerides and dietary fats. They are activated to their CoA derivatives in the cytoplasm and are transported into the mitochondrion via the carnitine shuttle.

The carnitine shuttle

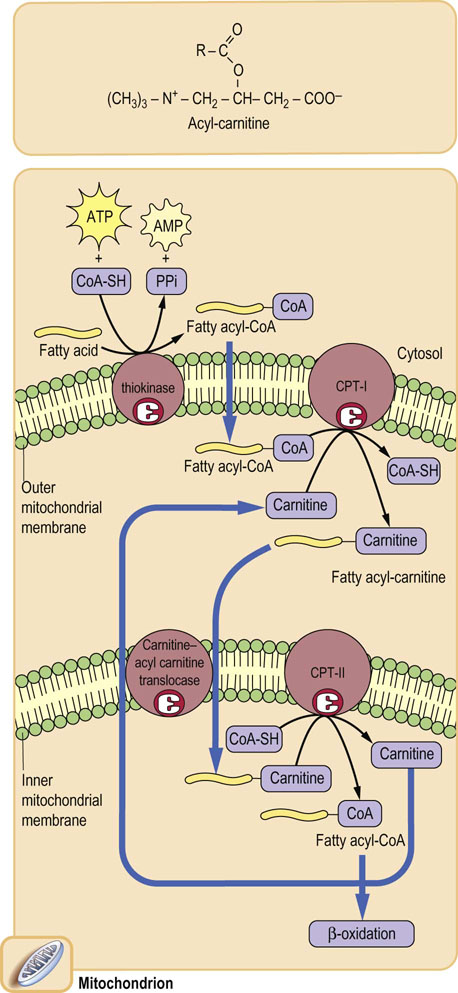

The carnitine shuttle bypasses the impermeability of the mitochondrial membrane to Coenzyme A

CoA is a large, polar, nucleotide derivative (Fig. 14.2), and cannot penetrate the mitochondrial inner membrane. Thus, for the transport of long-chain fatty acids, the fatty acid is first transferred to the small molecule, carnitine, by carnitine palmitoyl transferase-I (CPT-I), located in the outer mitochondrial membrane. An acyl-carnitine transporter or translocase in the inner mitochondrial membrane mediates transfer of the acyl-carnitine into the mitochondrion, where CPT-II regenerates the acyl-CoA, releasing free carnitine. The carnitine shuttle (Fig. 15.2) operates by an antiport mechanism in which free carnitine and the acyl-carnitine derivative move in opposite directions across the inner mitochondrial membrane. The shuttle is an important site in the regulation of fatty acid oxidation. As discussed in the next chapter, the carnitine shuttle is inhibited by malonyl-CoA after the ingestion of carbohydrate-rich meals. Malonyl-CoA prevents the futile cycle in which newly synthesized fatty acids would be oxidized in the mitochondrion.

Oxidation of fatty acids

Mitochondrial β-oxidation

Oxidation of the β-carbon (C-3) facilitates sequential cleavage of acetyl units from the carboxyl end of fatty acids

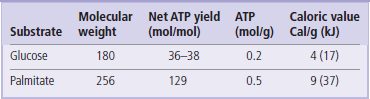

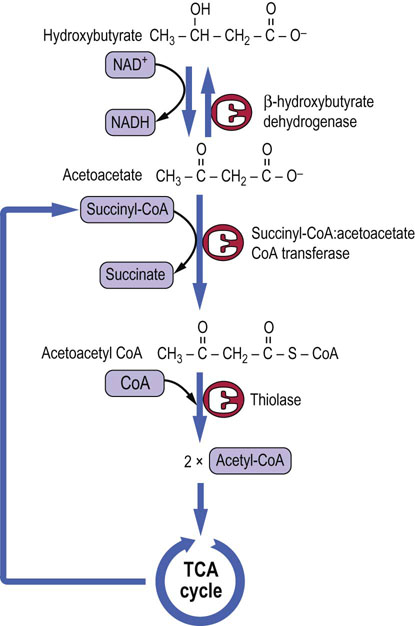

Fatty acyl-CoAs are oxidized in a cycle of reactions involving oxidation of the β-carbon to a ketone: hence the term β-oxidation (Figs 15.3 and 15.4). The oxidation is followed by cleavage between the α- and β-carbons by a thiolase, rather than hydrolase, reaction; in this way the high energy of the thioester bond is preserved to provide the thermodynamic driving force for subsequent reactions. One mole each of acetyl-CoA, FADH2 and NADH is formed during each cycle, along with a fatty acyl-CoA with two fewer carbon atoms. For a 16-carbon fatty acid, such as palmitate, the cycle is repeated seven times, yielding 8 moles of acetyl-CoA (see Fig. 15.3), plus 7 moles of FADH2 and 7 moles of NADH + H+. This process occurs in the mitochondrion, and the reduced nucleotides are used directly for synthesis of ATP by oxidative phosphorylation (Table 15.2).

Fig. 15.3 Overview of β-oxidation of palmitate.

In a cycle of reactions, the carbons of the fatty acyl-CoA are released in two-carbon acetyl-CoA units; the yield of 28 ATP from this β-oxidation is nearly equivalent to that from complete oxidation of glucose. In liver, the acetyl-CoA units are then used for synthesis of ketone bodies, and in other tissues they are metabolized in the TCA cycle to form ATP. The complete oxidation of palmitate yields a net 106 moles of ATP, after correction for the 2-mole equivalents of ATP invested at the thiokinase reaction. The overall production of ATP per gram of palmitate is about twice that per gram of glucose, because glucose is already partially oxidized in comparison with palmitate. For this reason, the caloric value of fats is about twice that of sugars (Table 15.2).

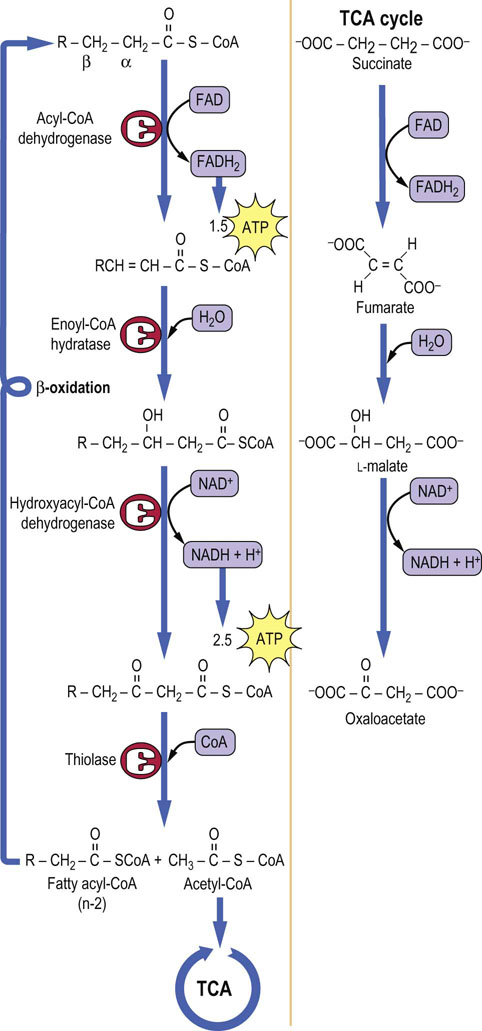

Fig. 15.4 β-Oxidation of fatty acids.

Oxidation occurs in a series of steps at the carbon that is β to the keto group. Thiolase cleaves the resultant β-ketoacyl-CoA derivative to give acetyl-CoA and a fatty acid with two fewer carbon atoms, which then re-enters the β-oxidation cascade. Note the similarity between these reactions and those of the TCA cycle, shown on the right.

The four steps in the cycle of β-oxidation are shown in detail in Figure 15.4. Note the similarity between the sequence of these reactions and those from succinate to oxaloacetate in the TCA cycle. In common with succinate dehydrogenase, acyl-CoA dehydrogenase uses FAD as a coenzyme, and is an integral protein in the inner mitochondrial membrane. Even the trans geometry of fumarate and the stereochemical configuration of L-malate in the TCA cycle are mirrored by trans-enoyl-CoA and L-hydroxyacyl-CoA intermediates in β-oxidation. The last step of the β-oxidation cycle is catalyzed by thiolase, which traps the energy obtained from the carbon–carbon bond cleavage as acyl-CoA, allowing the cycle to continue without the necessity of reactivating the fatty acid. The cycle continues until all the fatty acid has been converted to acetyl-CoA, the common intermediate in the oxidation of carbohydrates and lipids.

Peroxisomal catabolism of fatty acids

Peroxisomes are subcellular organelles found in all nucleated cells. They are involved in the oxidation of a number of substrates, including urate, and long-, very long- and branched-chain fatty acids. They are also the principal sites of production of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in the cell, and account for nearly 20% of oxygen consumption in hepatocytes. Peroxisomes have a carnitine shuttle and conduct β-oxidation by a pathway similar to the mitochondrial pathway, except that their acyl-CoA dehydrogenase is an oxidase, rather than a dehydrogenase. FADH2 produced in this and other oxidation reactions, including α- and ω-oxidation, is oxidized by molecular oxygen to produce H2O2. This pathway is energetically less efficient than β-oxidation in the mitochondrion where ATP is produced by oxidative phosphorylation. Peroxisomal enzymes cannot oxidize short-chain fatty acids, so products such as butanoyl-, hexanoyl- and octanoyl-carnitine are exported or diffuse from peroxisomes for further catabolism in the mitochondrion.

Zellweger syndrome, resulting from defects in import of enzymes into peroxisomes, is a severe multiorgan disorder, leading to death usually at about 6 months of age; it is characterized by accumulation of long-chain fatty acids in neuronal tissue, most likely because of the inability to turn over neuronal fatty acids. Peroxisomes also have anabolic functions. They are thought to have a role in production of acetyl-CoA for biosynthesis of cholesterol and polyisoprenoids (Chapter 17), and they contain the dihydroxyacetone-phosphate acyltransferase required for synthesis of plasmalogens (Chapter 28). The fibrates are a class of hypolipidemic drugs that act by inducing peroxisomal proliferation in liver.

Alternative pathways of oxidation of fatty acids

Unsaturated fatty acids yield less FADH2 when they are oxidized

Unsaturated fatty acids are already partially oxidized, so less FADH2, and correspondingly less ATP, is produced by their oxidation. The double bonds in polyunsaturated fatty acids have cis geometry and occur at three-carbon intervals, whereas the intermediates in β-oxidation have trans geometry and the reactions proceed in two-carbon steps. The metabolism of unsaturated fatty acids therefore requires additional isomerase and oxidoreductase enzymes, both to shift the position and to change the geometry of the double bonds.

Odd-chain fatty acids produce succinyl-CoA from propionyl-CoA

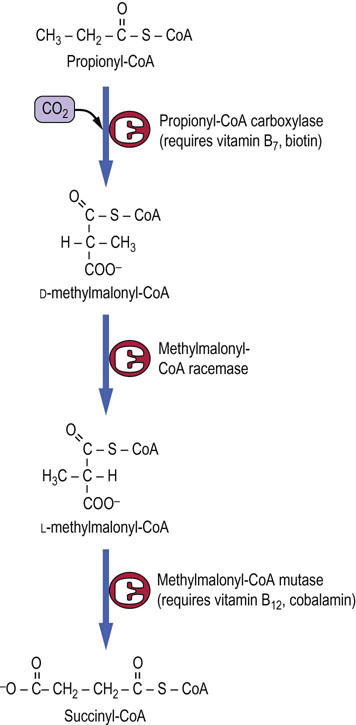

The oxidation of fatty acids with an odd number of carbons proceeds from the carboxyl end, like that of normal fatty acids, except that propionyl-CoA is formed by the last thiolase cleavage reaction. The propionyl-CoA is converted to succinyl-CoA by a multistep process involving three enzymes and the vitamins biotin and cobalamin (Fig. 15.5). The succinyl-CoA enters directly into the TCA cycle.

Fig. 15.5 Metabolism of propionyl-CoA to succinyl-CoA.

Propionyl-CoA from odd-chain fatty acids is a minor source of carbons for gluconeogenesis. The intermediate, methylmalonyl-CoA, is also produced during catabolism of branched-chain amino acids. Defects in methylmalonyl-CoA mutase or deficiencies in vitamin B12 lead to methylmalonic aciduria.

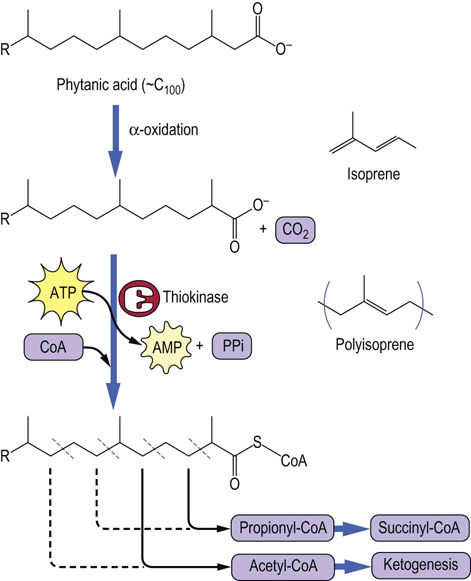

α-Oxidation initiates oxidation of branched-chain fatty acids to acetyl-CoA and propionyl-CoA

Phytanic acids are branched-chain polyisoprenoid lipids found in plant chlorophylls. Because the β-carbon of phytanic acids is at a branch point, it is not possible to oxidize this carbon to a ketone. The first and essential step in catabolism of phytanic acids is α-oxidation to a pristanic acid, releasing the α-carbon as carbon dioxide. Thereafter, as shown in Figure 15.6, acetyl-CoA and propionyl-CoA are released alternately and in equal amounts. Refsum's disease is a rare neurologic disorder, characterized by accumulation of phytanic acid deposits in nerve tissues as a result of a genetic defect in α-oxidation.

Ketogenesis – a metabolic pathway unique to liver

Ketogenesis in fasting and starvation

Ketogenesis is a pathway for regenerating CoA from excess acetyl-CoA

The liver uses fatty acids as its source of energy for gluconeogenesis during fasting and starvation. Fats are a rich source of energy and, under conditions of fasting or starvation, liver mitochondrial concentrations of fat-derived ATP and NADH are high, inhibiting isocitrate dehydrogenase and shifting the oxaloacetate–malate equilibrium toward malate. TCA cycle intermediates that are formed from amino acids released from muscle as part of the response to fasting and starvation (see Chapter 21) are also converted to malate in the TCA cycle. The malate exits the mitochondrion to take part in gluconeogenesis (Chapter 13). The resulting low level of oxaloacetate in hepatic mitochondria limits the activity of the TCA cycle, resulting in an inability to metabolize acetyl-CoA efficiently in the TCA cycle. Although the liver could obtain sufficient energy to support gluconeogenesis simply by the enzymes of β-oxidation, which generate both FADH2 and NADH, the accumulation of acetyl-CoA, with concomitant depletion of CoA, eventually limits β-oxidation.

What does the liver do with the excess acetyl-CoA that accumulates in fasting or starvation?

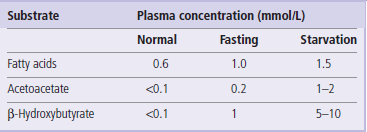

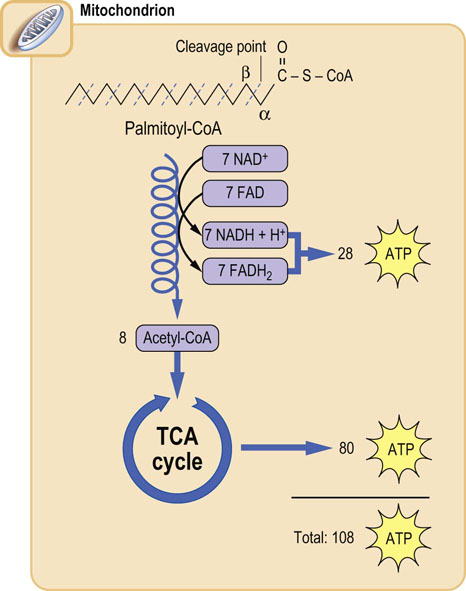

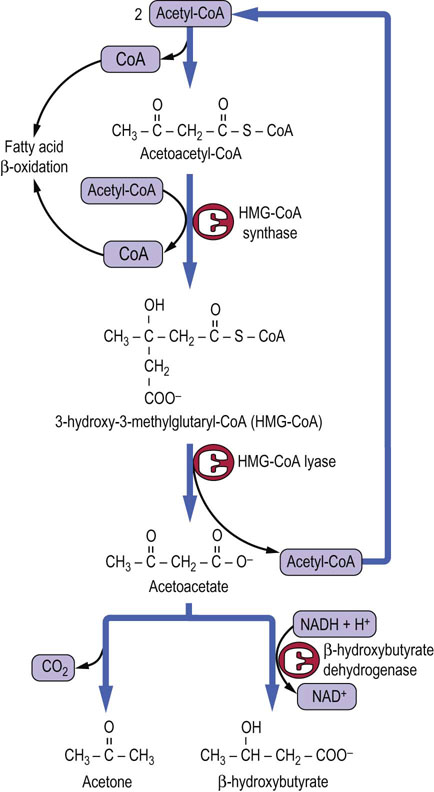

The problem of dealing with excess acetyl-CoA is a critical one because CoA is present in only catalytic amounts in tissues, and free CoA is required to initiate and continue the cycle of β-oxidation which is the primary source of ATP in liver during gluconeogenesis. To recycle the acetyl-CoA, the liver uses a unique pathway known as ketogenesis, in which free CoA is regenerated and the acetate group appears in blood in the form of three water-soluble lipid-derived products: acetoacetate, β-hydroxybutyrate, and acetone. The pathway of formation of these ‘ketone bodies’ (Fig. 15.7) involves the synthesis and decomposition of hydroxymethylglutaryl (HMG)-CoA in the mitochondrion. The liver is unique in its content of HMG-CoA synthase and lyase, but is deficient in enzymes required for metabolism of ketone bodies, which explains their export into blood.

Fig. 15.7 Pathway of ketogenesis from acetyl-CoA.

Ketogenesis generates ketone bodies from acetyl-CoA, releasing the CoA to participate in β-oxidation. The enzymes involved, HMG-CoA synthase and lyase, are unique to hepatocytes; mitochondrial HMG-CoA is an essential intermediate. The initial product is acetoacetic acid, which may be enzymatically reduced to β-hydroxybutyrate by β-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase, or may spontaneously (nonenzymatically) decompose to acetone, which is excreted in urine or expired by the lungs.

Ketone bodies are taken up in extrahepatic tissues, including skeletal and cardiac muscle, where they are converted to CoA derivatives for metabolism (Fig. 15.8). Ketone bodies increase in plasma during fasting and starvation (Table 15.3) and are a rich source of energy. They are used in cardiac and skeletal muscle in proportion to their plasma concentration. During starvation, the brain also converts to the use of ketone bodies for more than 50% of its energy metabolism, sparing glucose and reducing the demand on degradation of muscle protein for gluconeogenesis (see Chapters 13 and 21).

Mobilization of lipids during gluconeogenesis

Carbohydrate and lipid metabolism are coordinately regulated by hormone action during the feed-fast cycle

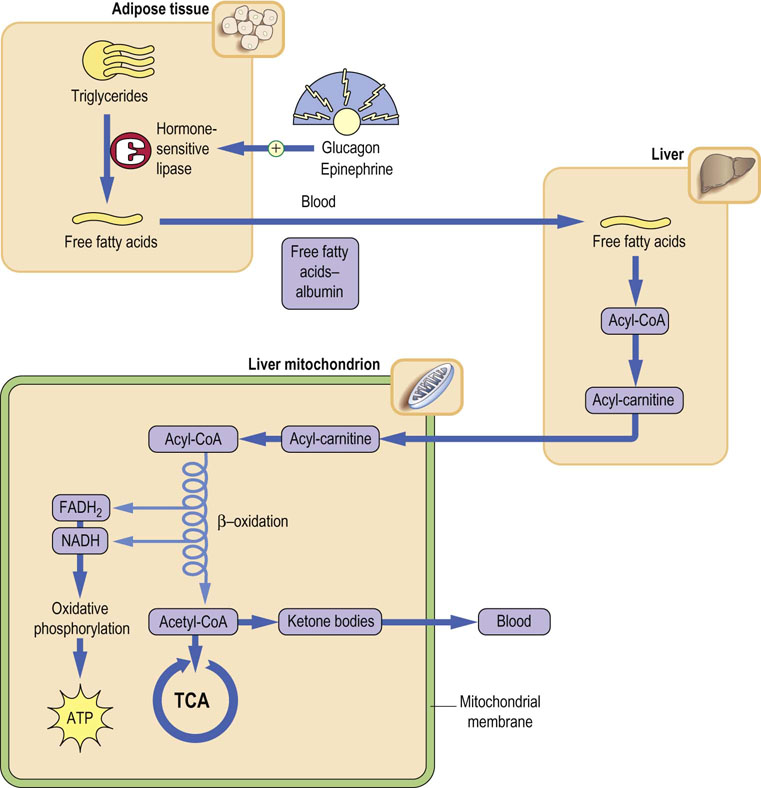

Insulin, glucagon, epinephrine, and cortisol control the direction and rate of glycogen and glucose metabolism in liver. During fasting and starvation, hepatic gluconeogenesis is activated by glucagon and requires the coordinated degradation of proteins and release of amino acids from muscle, and the degradation of triglycerides and release of fatty acids from adipose tissue. The latter process, known as lipolysis, is controlled by the adipocyte enzyme hormone-sensitive lipase, which is activated by phosphorylation by cAMP-dependent protein kinase A in response to increasing plasma concentrations of glucagon (Chapters 13 and 21). Like gluconeogenesis, lipolysis is inhibited by insulin.

The activation of hormone-sensitive lipase has predictable effects – increasing the concentration of free fatty acids and glycerol in plasma during fasting and starvation (Fig. 15.9); similar effects are observed in response to epinephrine during the stress response. Epinephrine activates both glycogenolysis in the liver and lipolysis in adipose tissue so that both fuels, glucose and fatty acids, increase in blood during stress. Cortisol exerts a more chronic effect on lipolysis and also causes insulin resistance. Cushing's syndrome (Chapter 39), in which there are high blood concentrations of cortisol, is characterized by hyperglycemia, muscle wastage, and redistribution of fat from glucagon-sensitive adipose depots to atypical sites, such as the cheeks, upper back, and trunk.

Fig. 15.9 Regulation of lipid metabolism by glucagon and epinephrine.

Glucagon and epinephrine activate hormone-sensitive lipase in adipose tissue, in coordination with activation of proteolysis in muscle and gluconeogenesis in liver. Metabolism of fatty acids through β-oxidation in liver yields ATP for gluconeogenesis. The acetyl-CoA is converted to and released to blood as ketone bodies. These effects are reversed by insulin following a meal.

Regulation of ketogenesis

Ketogenesis is activated in concert with gluconeogenesis during fasting and starvation

Ketogenesis increases when hormone-sensitive lipase is activated by glucagon in adipose tissue during fasting and starvation, and in diabetes. Under these conditions, plasma fatty acid concentration increases, and the liver uses these fatty acids to support gluconeogenesis. The energy is derived primarily from β-oxidation, and the product, acetyl-CoA, is metabolized by ketogenesis. Why isn't the acetyl-CoA used in the tricarboxylic acid cycle?

During gluconeogenesis, glucagon activation of the cAMP cascade in liver inhibits glycolysis (Fig. 13.9), limiting pyruvate flux from carbohydrates. Any pyruvate that is formed, mostly from lactate and alanine, is converted to oxaloacetate by pyruvate carboxylase, which is activated by acetyl-CoA (Fig. 13.8). The oxaloacetate is then converted to malate for gluconeogenesis and, because of the low level of oxaloacetate, a substrate for citrate synthase, the acetyl-CoA is directed to ketogenesis, rather than used for energy metabolism in the tricarboxylic acid cycle. The orientation toward ketogenesis is controlled by the energy charge of liver. The high ATP concentration, produced by fat metabolism, inhibits the tricarboxylic acid cycle at the isocitrate dehydrogenase step (Chapter 14). Further, by respiratory control (Chapter 9), high ATP leads to an increase in the mitochondrial membrane potential, which inhibits the electron transport chain. The resulting increase in the NADH/NAD+ ratio favors reduction of oxaloacetate to malate, which exits the mitochondrion for gluconeogenesis, rather than consumption in the tricarboxylic acid cycle. In summary, during gluconeogenesis, acetyl-CoA derived from fatty acid metabolism is converted to ketone bodies; it has nowhere else to go! The increase in ketone bodies in plasma (ketonemia) leads to their appearance in urine (ketonuria). In type 1 diabetes, the high rate of ketogenesis may lead to excessive ketonemia, and possibly to life-threatening diabetic ketoacidosis (Chapter 21).

Summary

Unlike carbohydrate fuels, which enter the body primarily as glucose or sugars that are converted to glucose, lipid fuels are heterogeneous with respect to chain length, branching, and unsaturation.

Unlike carbohydrate fuels, which enter the body primarily as glucose or sugars that are converted to glucose, lipid fuels are heterogeneous with respect to chain length, branching, and unsaturation.

The catabolism of fats is primarily a mitochondrial process, but also occurs in peroxisomes.

The catabolism of fats is primarily a mitochondrial process, but also occurs in peroxisomes.

Using a variety of chain length-specific transport processes and catabolic enzymes, the primary pathways of catabolism of fatty acids involve their oxidative degradation in two-carbon units, a process known as β-oxidation, which produces acetyl-CoA.

Using a variety of chain length-specific transport processes and catabolic enzymes, the primary pathways of catabolism of fatty acids involve their oxidative degradation in two-carbon units, a process known as β-oxidation, which produces acetyl-CoA.

In most tissues, the acetyl-CoA units are used for ATP production in the mitochondrion.

In most tissues, the acetyl-CoA units are used for ATP production in the mitochondrion.

In liver, acetyl-CoA is catabolized to ketone bodies, primarily acetoacetate and β-hydroxybutyrate, by a mitochondrial pathway termed ketogenesis. The ketone bodies are exported from liver for energy metabolism in peripheral tissue.

In liver, acetyl-CoA is catabolized to ketone bodies, primarily acetoacetate and β-hydroxybutyrate, by a mitochondrial pathway termed ketogenesis. The ketone bodies are exported from liver for energy metabolism in peripheral tissue.

Ketonemia and ketonuria develop gradually during fasting, while ketoacidosis may develop during poorly controlled diabetes when fat metabolism is increased to high levels for support of gluconeogenesis.

Ketonemia and ketonuria develop gradually during fasting, while ketoacidosis may develop during poorly controlled diabetes when fat metabolism is increased to high levels for support of gluconeogenesis.

Cahill, GF, Jr. Fuel metabolism in starvation. Annu Rev Nutr. 2006; 26:1–22.

Islinger, M, Grille, S, Fahimi, HD, et al. The peroxisome: an update on mysteries. Histochem Cell Biol. 2012; 137:547–574.

Kossoff, EH, Hartman, AL. Ketogenic diets: new advances for metabolism-based therapies. Curr Opin Neurol. 2012; 25:173–178.

Longo, N, Amat di San Filippo, C, Pasquali, M. Disorders of carnitine transport and the carnitine cycle. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2006; 142:77–85.

McPherson, PA, McEneny, J. The biochemistry of ketogenesis and its role in weight management, neurological disease and oxidative stress. J Physiol Biochem. 2012; 68:141–151.

Rector, RS, Ibdah, JA. Fatty acid oxidation disorders: maternal health and neonatal outcomes. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010; 15:122–128.

Sass, JO. Inborn errors of ketogenesis and ketone body utilization. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2012; 35:23–28.

Solis, JO, Singh, RH. Management of fatty acid oxidation disorders: a survey of current treatment strategies. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002; 102:1800–1803.

Stojanovic, V, Ihle, S. Role of beta-hydroxybutyric acid in diabetic ketoacidosis: a review. Can Vet J. 2011; 52:426–430.

Wanders, RJ, Waterham, HR. Peroxisomal disorders: the single peroxisomal enzyme deficiencies. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006; 1763:1707–1720.

Wanders, RJ, Ferdinandusse, S, Brites, P, et al. Peroxisomes, lipid metabolism and lipotoxicity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010; 1801:272–280.

Wilcken, B. Fatty acid oxidation disorders: outcome and long-term prognosis. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2010; 33:501–506.

Wolfsdorf, J, Craig, ME, Daneman, D, et al. Diabetic ketoacidosis in children and adolescents with diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2009; 10(Suppl 12):118–133.

Carnitine. http://lpi.oregonstate.edu/infocenter/othernuts/carnitine/.

Lipids OnLine – slide library. www.lipidsonline.org/slides/.

Peroxisomal disorders. www.emedicine.com/neuro/topic309.htm.