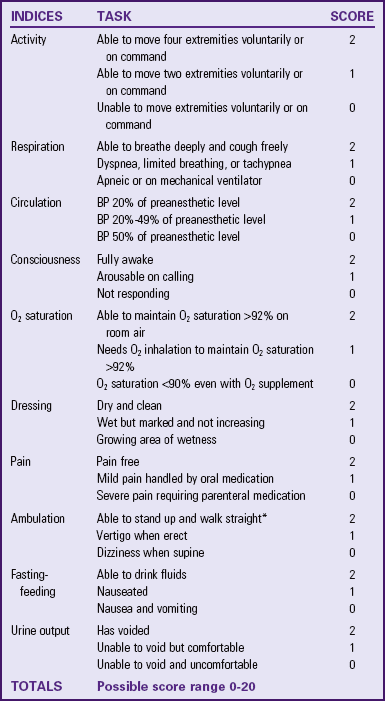

Aldrete, JA. Modifications to the post anesthesia score for use in ambulatory surgery. J Perianesth Nurs. 1998;13(3):148.

Aldrete, JA, Kroulik, D. A post-anesthetic recovery score. Anesth Analg. 1970;49:924.

Ambulatory Surgery Center Association. http://www.ascassociation.org, 2010 [accessed December 4, 2010 from].

American College of Surgeons, Patient education: partners in surgical care 2006. http://www.facs.org/patienteducation/index.html [Accessed November 10, 2011].

American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA). Practice guidelines for the perioperative management of patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Perioperative Management of Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:1081.

American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA). Practice guidelines for preoperative fasting and the use of pharmacologic agents to reduce the risk of pulmonary aspiration: application to healthy patients undergoing elective procedures: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Committee on Standards and Practice Parameters. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:495.

Association of periOperative Registered Nurses (AORN), AORN Position statement on care of the older adult in perioperative settings, AORN. Denver: AORN; 2010. http://www.aorn.org/PracticeResources/AORNPositionStatements/OlderAdult/

Association of periOperative Registered Nurses (AORN). Perioperative standards and recommended practices for inpatient and ambulatory setting. Denver: AORN; 2011.

Bond, LM, et al. Effects of preoperative teaching of the use of a pain scale with patients in the PACU. J Perianesth Nurs. 2005;20(5):333.

Bray, A. Preoperative nursing assessment of the surgical patient. Nurs Clin North Am. 2006;41(2):130.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Adverse events in hospitals: public disclosure of information about events. Washington, DC: Office of Inspector General; 2010. http://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-06-09-00360.pdf [Accessed January 25, 2012].

Cleveland Clinic. Your pulse and your target heart rate. Miller Family Heart & Vascular Institute at Cleveland Clinic, Preventive Cardiology and Rehabilitation Program my.clevelandclinic.org/heart, 2011. [Accessed August 12, 2011].

Costantini, R, et al. Controlling pain in the post-operative setting. MA Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;49(2):116.

Cronenwett, L, et al. Quality and safety education for nurses. Nurs Outlook. 2007;55(3):122.

Edelman, CL, Mandel, CL. Health promotion throughout the lifespan, ed 7. St Louis: Mosby; 2009.

Eliopoulos, C. Gerontologic nursing, ed 6. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 2005.

Fink, JB. Forced expiratory technique, directed cough and autogenic drainage. Respir Care. 2007;52(9):1210.

Galanti, GA. Caring for patients from different cultures, ed 4. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 2008.

Kaw, R, Stoller, JK. Pulmonary complications after noncardiac surgery: a review of their frequency and prevention strategies. Clin Pulmon Med. 2008;15(1):18.

Kruzik, N. Benefits of preoperative education for adult elective surgery patients. AORN J. 2009;90(3):381.

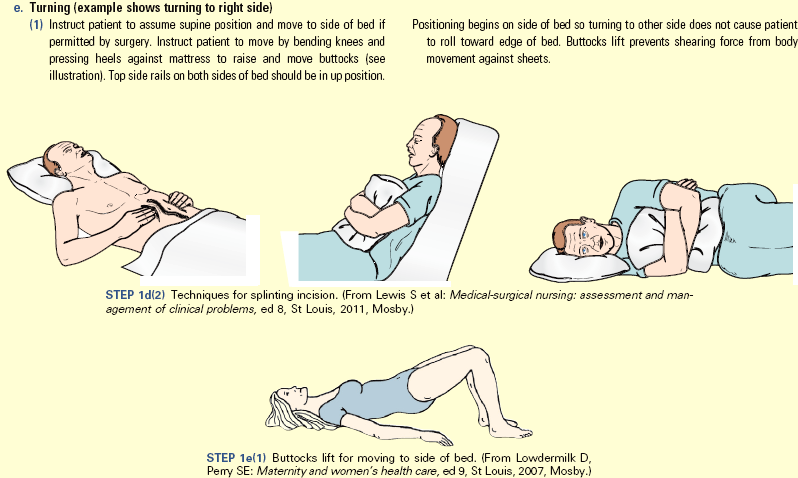

Lewis, S, et al. Medical-surgical nursing: assessment and management of clinical problems, ed 8. St Louis: Mosby; 2011.

Malignant Hyperthermia Association of the United States. Managing malignant hypertension: clinical update. online brochure http://www.mhaus.org, 2010. [Accessed September 2010].

Mamaril, ME. Nursing consideration in geriatric surgical patient: the perioperative continuum of care. Nurs Clin North Am. 2006;41:313.

McCaffrey, R. Make PONV prevention a priority. OR Nurse. 2007;1(2):39.

Meiner, SE. Gerontologic nursing, ed 4. St Louis: Mosby; 2011.

National Quality Forum (NQF). National voluntary consensus standards for public reporting of patient safety event information: a consensus report. Washington, DC: NQF; 2010.

Pruitt, B. Help your patient combat postoperative atelectasis. Nursing. 2006;36(5):64.

Rosén, S, et al. Calm or not calm: the question of anxiety in the perianesthesia patient. J Perianesth Nurs. 2008;23(4):237.

Rothrock, JC. Alexander’s care of the patient in surgery, ed 13. St Louis: Mosby; 2007.

Seet, E, Chung, F. Obstructive sleep apnea: preoperative assessment. Anesthesiol Clin. 2010;28(2):199.

Smetana, G. Postoperative pulmonary complications: an update on risk assessment and reduction. Cleveland Clin J Med. 2009;74(Suppl 4):60.

Sussman, G, Gold, M. Guidelines for the management of latex allergies and safe latex use in health care facilities, American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. http://www.acaai.org/patients/resources/allergies/Pages/latex-management-in-healthcare-facilities.aspx, 2010. [Accessed September 2010].

Turrentine, FE, et al. Surgical risk factors, morbidity and mortality in elderly patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203(6):865.

The Joint Commission (TJC). 2011 National Patient Safety Goals (NPGS). http://www.jointcommission.org/standards_information/npsgs.aspx, 2011.

Walton-Geer, PS. Prevention of pressure ulcers in the surgical patient. AORN J. 2009;89(3):538.