Medical Nutrition Therapy for Psychiatric Conditions

Sections of this chapter were written by Monica Woolsey, MS, RD for the previous edition of this text.

Psychiatric disorders (mental illnesses) involve altered brain or nervous system function that may result in altered perception and response to the environment. There are more than 450 million people with mental, neurologic, or behavioral problems throughout the world (World Health Organization, 2010). One in four individuals will suffer some type of mental illness during their lifetime. Indeed, many famous individuals have suffered from mental illnesses in the past (Focus On: Who Has Suffered from Mental Illness?)

Classification

The American Psychiatric Association classifies conditions into two different categories: Axis I and Axis II disorders. Axis I disorders often do not improve without medication. In fact, left unchecked, they can be degenerative and permanently destructive to brain and nervous system tissue. Axis II disorders are personality disorders. These disorders are primarily learned behaviors and do not respond to medication, with the possible exception of bipolar disorders, which may respond to very-long chain ω-3 fatty acids (e.g., fish oil) supplementation.

Axis I Disorders

The primary Axis I disorders include depression, anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, bipolar disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), schizophrenia, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The eating disorders (anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder) are also classified as Axis I disorders. Thus eating disorders are not merely behavioral issues; they require medical, nutritional, and often pharmacologic treatment in addition to psychotherapy. See Chapter 23. These interventions can be the foundation for successful response to psychotherapy. Nutrition is crucial for the rehabilitation of every mental health issue, not just eating disorders. In 1990 the United States Congress voted to establish the first week of October as Mental Illness Awareness Week, and much progress has been made in the past several decades. Box 42-1 lists psychiatric disorders that can have nutritional implications.

Despite their strong physiologic component, Axis I disorders are diagnosed primarily through behavioral criteria and psychological testing (e.g., the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory). Because there currently is no definitive diagnostic testing (e.g., blood tests, genetic tests, brain scans) for these disorders, it can be difficult to convince a person with such a diagnosis that he or she has a medical issue requiring treatment. It can also be difficult for friends, family members, and colleagues to understand that challenging behaviors affecting relationships and productivity are sometimes medical or biochemical in origin. For both parties, frustration, shame, and destructive behavior can result from attempting to willfully change behaviors that will not respond to anything less than intensive biologic intervention.

Altered food or eating behaviors can be the first indication that an Axis I disorder exists. For example, a person with obsessive-compulsive disorder may struggle making choices in grocery stores and restaurants, where a multitude of choices exist. They may seek help from a registered dietitian (RD) for specific direction (e.g., “just tell me what to eat”) to lessen the stress that these daily activities can induce. A person with bipolar disorder may alternate between periods of mania and depression. During the manic phase consumption of sugar, caffeine, and large quantities of food can be extreme and during the depression phase food intake may cease completely. These mood fluctuations often manifest as weight fluctuations and can even be misidentified as hypoglycemia. Often the medical comorbidity, not the core mental health diagnosis, is the reason an individual seeks an initial nutrition consultation.

A nutritionist’s job is to recognize unusual eating behaviors so that appropriate recommendations for treatment can be made. In general, when an individual seems to be genuinely trying to follow nutrition treatment recommendations or to change behavior, yet seems to be driven to behaviors that counter those intentions, the existence of an Axis I disorder should always be considered and the individual should be evaluated.

Axis II Disorders

The personality disorders listed in the American Psychological Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, IV (DSM-IV) include antisocial, narcissistic, histrionic, schizoid, avoidant, dependent, and borderline behavior. Psychotherapy is required to achieve symptom relief. Axis II disorders differ from Axis I disorders because, to the individual who has an Axis II disorder, the personality change serves an important purpose. A person with low self-esteem or who knows from experience that he or she struggles with interpersonal relationships may develop an Axis II disorder to prevent abandonment. For a person who does not have alternative communication, conflict resolution or coping skills, the perceived potential loss of that connection to others can be traumatizing. Whereas treating an Axis I disorder can provide great relief and improved well-being, treating an Axis II disorder may actually temporarily increase distress and behavioral acting out as treatment progresses.

Comorbidity

Axis I and Axis II disorders are often comorbid conditions. When an Axis I diagnosis impairs an individual’s ability to interact with his or her environment, an Axis II disorder may develop as a coping mechanism. For example, a person with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is likely to be easily overstimulated and fluctuate between periods of intense anxiety and depression. Borderline personality disorder is a common condition occurring comorbidly with PTSD. This person with this personality type often engages in extreme behaviors, including hypersexuality, emotional volatility, poor impulse control, manipulative behavior, and suicide attempts to (1) provide an emotional diversion from the physical wear and tear that the PTSD inflicts, and (2) maintain relationships with loved ones the individual perceives might otherwise abandon him or her.

Nutrition for the Brain and Nervous System

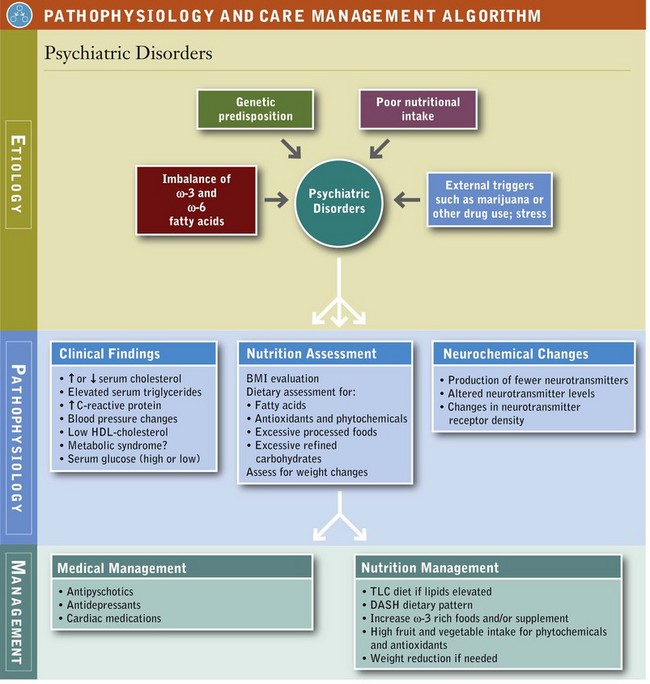

One of the most important contributions of nutrition to mental health is the maintenance of the structure and function of the neurons and brain centers coordinating communication within the body and between the body and the environment. See Pathophysiology and Care Management Algorithm: Psychiatric Disorders.

Omega-3 Fatty Acids

Omega-3 (ω-3) polyunsaturated fatty acids are preferred fatty acids in the brain and nervous system. From conception through maturity, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) ω-3 fatty acids make unique, important, and irreplaceable contributions to overall brain and nervous system functioning. Clinical research has shown effective and promising roles for EPA and DHA ω-3 fats in various psychiatric conditions.

Alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), another ω-3 fat with a chain length of 18 carbons and 3 double bonds (18 : 3 ω-3), is found in the oil of some seeds (e.g., flax, chia, sunflower) and some nuts (walnuts are the best source). Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) is a 20-carbon ω-3 fatty acid with 5 double bonds (20 : 5 ω-3), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) is a 22-carbon fatty acid with 6 double bonds (22 : 6 ω-3). EPA and DHA occur naturally in fatty fish and seafood.

Conversion Factors

ALA serves as a precursor for EPA and DHA. Research has shown that conversion of ALA to EPA and DHA in humans is low: conversion of ALA to EPA is approximately 5% to 10%, and conversion of ALA to DHA is even lower (<3%). Health status and other nutritional factors appear to influence conversion rates. There are also genetic variations in conversion (e.g., production of delta-6 desaturase enzyme), and recent studies have suggested possible differences in conversion rates between vegetarians and carnivores. Individuals with mental health conditions often have compromised nutritional intake or eating habits. Most nutrition and mental health experts do not recommend reliance on ALA as a source of EPA or DHA (Davis and Kris-Etherton, 2003; Harris et al, 2009; Kris-Etherton and Innis, 2007).

Omega-3s, Omega-6s and Mental Health

EPA works in balance with arachidonic acid (ARA), a 20-carbon ω-6 fatty acid with 4 double bonds (20 : 4 ω-6). ARA and EPA are eicosanoids, that is, precursors to prostaglandins, thromboxanes, and leukotrienes, which are involved with inflammation, vasoconstriction, and a multitude of metabolic regulations. Although specific mechanisms remain unclear, clinical research has shown the importance of sufficient EPA intake for general mental health, and particularly for nutrition support in conditions such as depression, suicide ideation, and homicide. In general, EPA works better when ingested with DHA. They also occur together naturally in foods.

DHA is preferred and selectively stored in brain and nerve cells. Similar to EPA, DHA is involved with metabolic regulation. DHA is required for normal brain growth, development, and maturation. DHA is involved with neurotransmission (how brain cells communicate with each other), lipid messaging, genetic expression, and cell membrane synthesis. DHA also provides vital structural contributions; DHA is concentrated in the phospholipids of brain cell membranes. Box 42-2 lists conditions in which DHA and EPA play a role.

Diet Is First

Although deep-sea oily fish such as salmon and tuna contain more EPA and DHA per serving, all fish and seafood contain some ω-3 in varying amounts. Sardines, for example, are an excellent choice, whereas tilapia is low in ω-3 fatty acids. There are additional benefits of consuming fish in the diet; fish provides lean protein and trace minerals and can displace other less nutritious food choices. However, the white fish used in processed food fish fillets is lower in ω-3; and because of the added batter and frying, the caloric contribution of ω-3s may be less than the other fat calories in these convenience foods. See Appendix 40.

During Pregnancy and Lactation

Experts recommend that pregnant women consume at least 200-300 mg DHA during pregnancy for proper infant development (Koletzko, 2007). The role of DHA and EPA in pregnancy and lactation is discussed in Chapter 16.

Up to 10% of pregnant women can experience depression, and there is considerable interest in finding effective alternatives to prescription medication. Several pilot trials using EPA and DHA from fish oil have been conducted in depressed pregnant women and women with post-partum depression. One dose-ranging study reported measurable improvements in women who consumed as little as 500 mg of combined EPA and DHA. Experts have also recently suggested that a daily intake of 900 mg DHA during pregnancy may be necessary to support both infant and maternal needs. A landmark study that followed more than 9000 pregnant women and their children for 8 years reported lower intelligence quotient and social development in the children of those women who consumed less than 12 ounces of fish a week while pregnant. In other words, the children of the women who ate fish two or more times a week during their pregnancy fared better emotionally and mentally in their youth (Freeman et al, 2006a, 2006b; Hibbeln et al, 2007b, Hibbeln and Davis, 2009).

During Infancy

Breast milk contains EPA and DHA ω-3 and ARA ω-6. In 2002 the United States began fortifying infant formula with DHA and ARA. Because DHA has an identified role in infant development (brain, eyes, central nervous system), experts agree that DHA should be considered an essential nutrient in infancy, particularly among preterm infants. DHA accumulation in the brain begins in utero and continues into adolescence. It is important to remember that humans (including infants) cannot synthesize ω-3 fatty acids; the amount taken in depends on the feeding source. Infants can convert EPA and DHA from ALA, but again conversion of ALA to DHA has been shown to be inadequate for infant needs. A precise role for ω-3s in neurologic conditions, such as autism spectrum disorder, is currently being considered but remains unclear. See Chapter 45.

During Childhood

Depression among children is increasing. The few clinical trials conducted in depressed children have shown significant benefit from EPA and DHA fish oil supplementation. At the same time, the few studies measuring consumption of EPA and DHA in children report very low average intakes.

Most clinical trials using EPA and DHA from fish oil supplements in children with attention-deficit disorder (ADD) or ADHD have reported benefit, but not all. The difference in findings may be due to many variables, including study design, dose, age of supplementation, the background diet, genetics, and teacher or family dynamics. However, it has been shown that children with ADD, ADHD, behavior problems, or who are overweight tend to have lower levels of EPA and DHA in their blood (Antalis et al, 2006; Richardson, 2000, 2006). Box 42-3 lists questions about fatty acids and a person’s early feeding history that may be useful in a nutrition assessment.

During Adulthood

According to the World Health Organization, major depression is the leading cause of disability around the world. Depression is a mental health condition; diagnosis and treatment by a mental health professional is recommended. A significant number of depressed individuals feel ashamed and do not seek treatment. Those who suffer from depression tend to report lower quality of life, social impairment, and problems in the workplace. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey suggests that more than 1 in 20 adults in the United States are experiencing depression, and it is more common among women and the poor. Depression is often associated with poor health and higher health care costs.

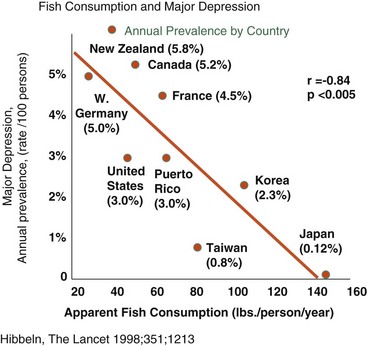

Epidemiologic research has identified associations between lower seafood consumption and increased rates of depression around the world. See Fig. 42-1. Dozens of clinical studies using EPA and DHA ω-3 supplements for depression have been conducted, and results are mixed but generally positive (Martins, 2009). Questions remain regarding the dose of ω-3s, the form, and the duration of supplementation. In 2011 more than 30 clinical trials are investigating the relationship between ω-3s and depression. Omega-3s are often provided in conjunction with antidepressant medication and usually show additive benefit (Freeman et al, 2006a; Jazayeri et al, 2008).

FIGURE 42-1 Fish Consumption and Major Depression

This inverse relationship between the amount of fish consumed by a population and the incidence of depression in that population is thought to be related to amount of ω-3 fats contributed by fish in the diet, and resulting body and brain tissue levels of ω-3 fats. (Hibbeln JR: Fish consumption and major depression, Lancet 351:1213, 1998.)

Increases in homicide occurrence have been associated with less seafood consumption. This finding led to an article in the New York Times entitled “Does Eating Salmon Lower the Murder Rate?” (Mihm, 2006). When EPA and DHA ω-3s and multivitamins were given to prison inmates, antisocial behavior, including violence, fell significantly, compared with those on placebo. In another study, teens who had previously attempted suicide made fewer suicide attempts when given EPA and DHA (Hallahan et al, 2007; Hibbeln, 2001, 2007a).

During the Aging Years

Omega-3 fatty acids are also considered important in maintaining cognitive function with age. Research suggests that individuals who consume more fish and seafood during their lifetimes have better cognitive function as they age. Higher blood levels of DHA have been associated with better cognitive function in middle adulthood. Some studies have shown that eating fish or supplementing with EPA and DHA ω-3s improves cognition (e.g., delays cognitive decline) and the onset of dementia, but not all studies report positive findings and questions remain, including the role of genetics in risk factors for onset of cognitive difficulties. Researchers and dietitians question if EPA and DHA ω-3s have a greater effect in prevention or intervention for mental health (Dangour et al, 2010; Muldoon et al, 2010; Vannice, 2005; Whalley et al, 2004). Neurologic disorders are discussed in Chapter 41.

Although much focus is on DHA, it is interesting to note that research has generally shown that consuming both EPA and DHA, but more EPA relative to DHA is necessary for clinical benefit in many psychiatric conditions. To date clinical intervention studies in mental health using DHA alone have been generally disappointing. Researchers are actively seeking answers. Freeman et al, 2006; Marangell et al, 2003, Martins, 2009.

The American Dietetic Association recommends that children and adults eat fish at least twice a week. A minimum intake of 500 mg EPA and DHA is recommended for adults (Kris-Etherton and Innis, 2007). The International Society for the Study of Fatty Acids and Lipids also recommends a daily minimum of 500 mg combined of EPA and DHA (Cunnane, 2004). American Psychiatric Association recommendations for ω-3 intake are shown in Table 42-1.

TABLE 42-1

American Psychiatric Association Recommendations for Omega-3 Intake

| Who | Recommendation |

| All adults | Eat fish two or more times per week. |

| Individuals with mood, impulse-control, or psychotic disorders | Consume 1 g (1000 mg) EPA and DHA per day. |

| Patients with mood disorders | Use a supplement providing 1-9 g of EPA and DHA. Use of more than 3 g/day should be monitored by a physician. |

DHA, Docosahexaenoic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid.

Source: Freeman MP et al: Omega-3 fatty acids: evidence base for treatment and future research in psychiatry, J Clin Psychiatry 67:1954, 2006.

Omega-3 Supplements

As supplements, EPA and DHA ω-3 fatty acids are available from fish oil and cod liver oil. Other marine sources, such as krill and calamari, are coming to the market. An algal (vegetarian) source of DHA is also available. Omega-3 supplements are best absorbed when consumed with a fat-containing meal or snack. This practice also improves patient compliance, particularly with higher doses. Better ω-3 supplements include an antioxidant, such as vitamin E, in the formula. The purpose of adding an antioxidant is to stabilize and preserve the long-chain polyunsaturated fats. Fortification of foods with ω-3s is increasing, and as always, reading the label is imperative to know the form and dose of ω-3. Genetically modified forms of EPA and DHA are also coming to the market for use in fortified foods and supplements (Vannice, 2010). See Focus On: Genetically Modified (GM) Foods, in Chapter 27.

Vitamin D

Vitamin D affects hundreds of genes in the human body and is recognized as an important nutrient for brain health as well as for bone and skeletal health. Because vitamin D can be synthesized from sunlight, adequate sun exposure or vitamin D3 intake can help maintain mental health. Clinical research has associated vitamin D deficiency with the presence of an active mood disorder, with aspects of cognitive disorder as well as increased risk for both major and minor depression in older adults (Hoogendijk et al, 2008; Stewart et al, 2010; Wilkins et al 2006).

In November 2010 the Institute of Medicine (IOM) of the National Academies published new dietary reference intakes for vitamin D. Focusing on vitamin D and physical health, specifically bone health, the IOM report established a recommended dietary allowance (RDA) of 600 IU/day of vitamin D, an increase of 50% from 1997 (Institute of Medicine, 2010). The tolerable upper limit was increased to 4000 IU/day.

Serum levels of vitamin D are most often tested by assessing circulating levels of 25(OH)D, which is the combined product of skin synthesis from sun exposure and dietary sources (Calvo et al, 2005). Currently, no official agreement has been reached regarding blood levels of 25(OH)D that indicate deficiency, insufficiency, and sufficiency of vitamin D. Other biomarkers of nutritional vitamin D status include parathyroid hormone levels, intestinal calcium absorption, insulin sensitivity, beta cell function, and innate immune function.

The best sources of vitamin D are exposure to sunlight, foods such as oily fish and egg yolks, and fortified foods, such as cow, soy or other fortified milks, and cereals. Due to recent changes in lifestyle such as more time indoors and more use of sunscreens to protect against skin cancer, many people do not receive adequate exposure to sunlight. Similarly, many people do not eat egg yolks, oily fish, or fortified foods in sufficient quantity to meet the RDA for vitamin D. Therefore recommending supplements or ensuring regular consumption of fortified foods may be warranted.

B-Complex Vitamins

The B-complex vitamins are known for having an effect on neurologic and brain health and sufficient intake is important for individuals with psychiatric disorders. Recent human studies have identified genetic alterations that alter the production and function of serotonin, dopamine, and other neurotransmitters. These alterations may be identified by various biochemical or deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) testing. For example, the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) test can reveal alleles (C > T and A > C) that decrease production of serotonin and dopamine, as well as increase homocysteine retention. Clients with these genetic SNPs (see Chapter 5) usually require folate supplementation in a methylated form. A methylmalonic acid test can reveal whether B12 levels are sufficient to maintain low serum homocysteine levels. See Chapters 3, 8, and 33 for further discussion of the B vitamins and brain function.

The best sources of folate are brewer’s yeast, mushrooms, spinach, broccoli, brussels sprouts, asparagus, kale and other greens, legumes, liver, and orange juice. Vitamin B12 is found in animal sources only, such as beef, liver, clams, oysters, crab, tuna, and halibut. Thus, vegans must choose foods and supplements wisely. Pyridoxine (B6) is found in beef liver, oatmeal, bananas, chicken, potatoes, avocado, sunflower seeds, brewer’s yeast, halibut, pork, and brown rice.

Phytochemicals

New research suggests that plant-based foods rich in the bioactive chemicals, phytochemicals, make important nutritional and biochemical contributions to normal brain function and mental health. Foods such as berries, citrus fruits, green tea and some spices contain phytochemicals, as well as essential vitamins and minerals. The phytochemicals showing the most promise are 3 sub-classes of flavonoids: flavanols, anthocyanins and flavanones. These phytochemicals have antioxidant activity, but their more important contributions may be protecting and preserving brain cell structure and metabolism through a complex cascade of cellular mechanisms, including signaling, transcription, phosphorylation and gene expression (Williams et al, 2004; Dashwood, 2008; Spencer, 2010).

There is evidence that other plant-based foods have nutritional and possibly pharmacological effects in the brain, but the mechanisms are yet to be elucidated. These foods appear to impact brain health through antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and nutragenomic influences, and more mechanisms are plausible. Examples of these foods include onion, ginger, tumeric, oregano, sage, rosemary and garlic. This is an exciting area of research to watch in the 21st century (Jellin, 2011).

A summary of flavonoids and nutrients that support healthy brain and nervous system can be found in Table 42-2.

Weight Management

Managing weight, eating behaviors and diet can be challenging for psychiatric patients. Depression and other mental health conditions are known to affect nutrition choices, interpersonal relationships, and lifestyle habits such as smoking, drinking, and self-care and each of these factors influence food choices and cooking practices. Individuals with psychiatric disorders who are taking psychotropic medicines may experience rapid or excessive weight gain. In fact, a commonly known side-effect of anti-depressant medications is weight gain, and many patients cite this reason to avoid or cease use of their medication. Depressed individuals can also experience loss of appetite and unintentional weight loss or anorectic behavior (Freeman et al, 2006; Jensen, 2008; Murphy et al, 2009).

Being proactive with patients is important. Keep in mind that eating behavior, appetite, focus, concentration, and even the circadian rhythm which affects the sleep/wake cycle can be altered. Individuals may lose or gain interest in food, shopping, and cooking, which affects their families as well as themselves. Working with patients to strategize healthy food choices, to practice supportive eating behaviors and meal planning is valuable. Knowing that one’s loved ones are cared for through a difficult period can be rewarding and psychologically uplifting. Encouraging regular physical activity and eating plans that support healthy weight and alleviate stress in the home and workplace is helpful (Gouin et al, 2010; Kiecolt-Glaser, 2010).

Addiction and Substance Abuse Recovery

Addiction is a chronic brain disorder that involves compulsive and relapsing behavior, with biochemical, psychological, and social vulnerabilities. A variety of behavioral and psychological anomalies result from ingestion of or exposure to a drug of abuse, medication, or toxin. The master “pleasure” molecule of addiction is dopamine; it is triggered by heroin, amphetamines, marijuana, alcohol, nicotine, and caffeine (Escott-Stump, 2012). In addition, poor diet and stress enhance the problems of the addicted individual and family members.

Alcohol dependence is a public health concern throughout the world. Event-related brain oscillations are seen, along with inherited neuroelectric deficits; for example, the serotonin receptor gene HTR7 is part of the biologic basis of alcohol dependence (Zlojutro et al., 2010). The addictive personality type is often perfectionistic and prone to depression; antidepressant medications may be useful for some individuals.

Eating disorders and substance abuse are similar; many clients have both. Eating disorders can arise from gene-environment interactions that alter genetic expression via epigenetic processes (Campbell et al., 2010). In most psychiatric disorders, either increased or decreased changes in appetite occur. It is important to be aware of the types of malnutrition and counseling techniques appropriate for this population. Counseling should include tips such as how a proper, nutritious diet can reduce cravings; how to choose a brain-healthy diet; maintaining physical activity; choosing nutrient-rich snacks; stress management; and tracking positive changes and successes (see Chapter 23).

Nutrition Interventions

The primary responsibility of a dietitian working with individuals who have a mental health diagnosis is to impart information and support for eating choices that minimize the negative effects of these illnesses on the client and their affected loved ones. Therapy for behavioral issues is primarily the responsibility of the psychotherapy team. Common nutrition diagnoses in this population may include:

• Deficit of food and nutrition knowledge

• Harmful food and nutrition attitudes and beliefs

• Imbalance of fats from foods

• Excessive carbohydrate intake

• Excessive intake of processed and refined foods

• Altered nutrition-related laboratory values

• Excessive or inadequate oral food and beverage intake

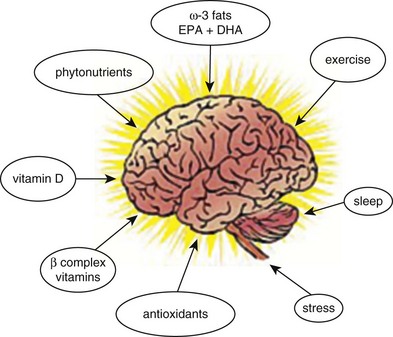

Individuals who have a psychiatric condition may not adapt readily to the fluctuations of life and changes in diet and lifestyle can exacerbate anxiety or depression. When working with the mentally ill, the dietitian should incorporate varying responses to diet, environment, genetics, behavior and stress and offer support and strategies to these individuals. See Fig. 42-2. For example, a primary goal of “behavioral change” in nutrition counseling is not usually easily embraced by members of this population. Although the long-term outcome of healthy food and lifestyle change is certainly positive, a person with a psychiatric condition, regardless of intelligence and life-stage, may find any change (e.g., food choices, relationships, or any life situation) overwhelming or even frightening. However, even small improvements in nutritional status can lead to meaningful results. And a positive experience with a dietitian can build a foundation and motivation to attempt other positive changes long after nutrition counseling is finished.

FIGURE 42-2 Brain function is affected by many more nutrients and lifestyle factors than previously thought, and research is rapidly revealing new connections. (© 2011 Photos.com a division of Getty Images. All rights reserved.)

For dietitians working in psychiatric units, suicide precautions are often needed. Therefore, those meals require special attention to prevent giving patients anything that they could use to do harm to themselves or others. Plastic utensils and paper goods may be a necessary precaution. A balanced, nutritious diet rich in ω-3 fatty acids and plant-based foods should be made available. Table 42-3 gives more specific guidance about nutrition in other psychiatric conditions.

TABLE 42-3

Nutrition for Specific Psychiatric Conditions

| Mental Disorder | Explanation | Relevance to Nutrition |

| Acute stress disorder or posttraumatic stress disorder | Development of anxiety and dissociative and other symptoms within 1 month following exposure to an extremely traumatic event; the symptoms may include reexperiencing the event, nightmares, and avoidance of trauma-related stimuli. | May increase or decrease appetite. Overall nutrition status may decline, or obesity may result. |

| Adjustment disorder | Maladaptive reaction to identifiable stressful life events. | May increase or decrease appetite. Overall nutrition status may decline, or obesity may result. |

| Amnestic disorder | Mental disorder characterized by acquired impairment in the ability to learn and recall new information, sometimes accompanied by inability to recall previously learned information, and not coupled with dementia or delirium. | Impaired ability to retain new information from nutrition counseling. |

| Anxiety disorders | A group of mental disorders in which anxiety and avoidance behavior predominate, including panic disorder, agoraphobia, specific phobias, social phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, acute stress disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder. | May increase or decrease appetite. Overall nutrition status may decline, or obesity may result. May respond to increased intake of ω-3 fats to 1-3 g/day. |

| Attention deficit disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder | Mental disorder characterized by inattention (such as distractibility, forgetfulness, not finishing tasks, and not appearing to listen), hyperactivity and impulsivity (such as fidgeting and squirming, difficulty in remaining seated, excessive running or climbing, feelings of restlessness, difficulty awaiting one’s turn, interrupting others, and excessive talking) or both types of behavior | Impaired ability to retain and use new information after nutrition counseling. May respond to increased intake of ω-3 fats to 1-3 g/day. |

| Autistic disorder | Severe pervasive developmental disorder with onset usually before 3 years of age and a biologic basis related to neurologic or neurophysiologic factors. Characterized by qualitative impairment in reciprocal social interaction (e.g., lack of awareness of the existence of feelings of others, failure to seek comfort at times of distress, lack of imitation), verbal and nonverbal communication, and capacity for symbolic play and by restricted and unusual repertoire of activities and interests. | May affect appetite, with increased needs common. Overall nutrition status may decline. May respond to increased intake of ω-3 fats, especially DHA, to 1-3 g/day. Gluten-free, casein-free, or soy-free diet may be useful. |

| Binge eating disorder | An eating disorder characterized by repeated episodes of binge eating, as in bulimia nervosa, but not followed by inappropriate compensatory behavior such as purging, fasting, or excessive exercise. | May affect nutrition status; health may decline or obesity may result. |

| Bipolar disorders | Mood disorders characterized by a history of manic, mixed, or hypomanic episodes, usually with concurrent or previous history of one or more major depressive episodes. | May increase or decrease appetite. Overall nutrition status may decline, or obesity may result. May respond to increased intake of ω-3 fats to 1-3 g/day preferably in combination with standard mood stabilizers. |

| Body dysmorphic disorder | A mental disorder in which a normal-appearing person is either preoccupied with some imagined defect in appearance or is overly concerned about some very slight physical anomaly. | Likely to cause altered eating habits with potential for decline in intake. May lead to eating disorder. May be prone to food fads or use of herbs or steroids. |

| Catatonia | Immobilization caused by the physiologic effects of a general medical condition. | May decrease appetite. Overall nutrition status may decline. |

| Childhood disintegrative disorder | Pervasive developmental disorder characterized by marked regression in a variety of skills, including language, social skills or adaptive behavior, play, bowel or bladder control, and motor skills after at least 2, but less than 10 years of apparently normal development. | May increase or decrease appetite. Overall nutrition status may decline; or obesity may result. |

| Conduct disorder | A type of disruptive behavior disorder of childhood and adolescence characterized by a persistent pattern of conduct in which rights of others or age-appropriate societal norms or rules are violated. | No specific nutritional challenges except that mealtimes may be disrupted. |

| Conversion disorder | Mental disorder characterized by conversion symptoms (loss or alteration of voluntary motor or sensory functioning suggesting physical illness, such as seizures, paralysis, dyskinesia, anesthesia, blindness, or aphonia) having no demonstrable physiologic basis. | May increase or decrease appetite. Overall nutritional status may decline or obesity may result. |

| Delusional disorder | Mental disorder marked by well-organized, logically consistent delusions, but lacking other psychotic symptoms. Most functioning is not markedly impaired, the criteria for schizophrenia are not met; symptoms of a major mood disorder are present only briefly, but delusional disorder may coexist with other psychiatric conditions. | May increase or decrease appetite. Overall nutrition status may decline, or obesity may result. |

| Depersonalization disorder | Dissociative disorder characterized by one or more severe episodes of depersonalization (feelings of unreality and strangeness in one’s perception of self or one’s body image) not caused by another mental disorder such as schizophrenia. The perception of reality remains intact; patients are aware of their incapacitation. Episodes are usually accompanied by dizziness, anxiety, or fears of going insane. | May increase or decrease appetite. An eating disorder or obesity can result; overall nutrition status may decline. |

| Depressive disorders | Mood disorders, such as major depressive disorder, dysthymia, or minor depression, in which depression is unaccompanied by manic or hypomanic episodes. | May increase or decrease appetite. Nutrition status may decline. May respond to increased intake of ω-3 fats to 1-3 g/day. |

| Dissociative disorders | Mental disorders characterized by sudden, temporary alterations in identity, memory, or consciousness, segregating normally integrated memories or parts of the personality from the dominant identity of the individual. | May increase or decrease appetite. Overall nutrition status may decline, or obesity may result. |

| Dissociative identity disorder | A disorder characterized by the existence in an individual of two or more distinct personalities, each having unique memories, characteristic behavior, and social relationships. Also referred to as multiple personality disorder. | May increase or decrease appetite. Overall nutrition status may decline, or obesity may result. |

| Dysthymic disorder | Mood disorder characterized by depressed feeling (sad, blue, low), loss of interest or pleasure in one’s usual activities, and by at least some of the following: altered appetite, disturbed sleep patterns, lack of energy, low self-esteem, poor concentration or decision-making skills, and feelings of hopelessness. Symptoms have persisted 2 years but are not severe enough to meet the criteria for major depressive disorder. | May increase or decrease appetite. Overall nutrition status may decline, or obesity may result. May coexist with an eating disorder. May respond to increased intake of ω-3 fats to 1-3 g/day. |

| Eating disorders | Any of several disorders in which abnormal feeding habits are associated with psychological factors; in DSM-IV these include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, pica and rumination disorder. | Overall nutrition status may decline, or obesity may result, depending on the specific condition. May respond to increased intake of ω-3 fats to 1-3 g/day. See Chapter 23. |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | Disorder characterized by the presence of excessive, uncontrollable anxiety and worry about two or more life circumstances for 6 months or longer, accompanied by some combination of restlessness, fatigue, muscle tension, irritability, disturbed concentration or sleep, and somatic symptoms. | May increase or decrease appetite. Overall nutrition status may decline, or obesity may result. May coexist with an eating disorder. May benefit from increased intake of ω-3 fats, especially DHA, 1-3 g/day. |

| Impulse control disorders | Group of mental disorders characterized by repeated failure to resist an impulse to perform some act harmful to oneself or others. | May increase or decrease appetite. Overall nutrition status may decline, but more likely obesity may result. |

| Motor skills disorder | Any disorder characterized by inadequate development of motor coordination severe enough to limit locomotion or restrict the ability to perform tasks, schoolwork, or other activities. | No specific nutritional changes, but may have difficulty preparing food. |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | Anxiety disorder characterized by recurrent obsessions (often about fear of contamination, disease, or other harm or punishment) or compulsions that are severe enough to interfere significantly with personal or social functioning. Performing compulsive rituals may release tension temporarily, and resisting them causes increased tension. | May increase or decrease appetite. May be avoidance of specific foods or food groups. Overall nutrition status may decline, or obesity may result. |

| Oppositional defiant disorder | A type of disruptive behavior disorder characterized by a recurrent pattern of defiant, hostile, disobedient, and negativistic behavior directed toward those in authority, including such actions such as defying the requests or rules of adults, deliberately annoying others, arguing, spitefulness, and vindictiveness that occur much more frequently than would be expected on the basis of age and developmental stage. | May increase or decrease appetite. Overall nutrition status may decline, or obesity may result. Mealtimes and thus quality of nutritional intake may be disrupted. |

| Pain disorder | A somatoform disorder characterized by a chief complaint of severe chronic pain that causes substantial distress or impairment in functioning; the pain is neither feigned nor intentionally produced, and psychological factors appear to play a major role in its onset, severity, exacerbation, or maintenance. | May increase or decrease appetite. Overall nutrition status may decline, or obesity may result. May benefit from increased intake of ω-3 fats, especially EPA, for their inflammatory effect, 1-3 g/day. |

| Panic disorder | Anxiety disorder characterized by recurrent panic (anxiety) attacks, episodes of intense apprehension; fear or terror associated with somatic symptoms such as dyspnea, palpitations, dizziness, vertigo, faintness, or shakiness, and with psychological symptoms such as feelings of unreality or fears of dying, going crazy, or losing control. There is usually chronic nervousness and tension between attacks; often, but not always associated with agoraphobia. | May increase or decrease appetite. Food may be used to soothe. Overall nutrition status may decline, or obesity may result. |

| Personality disorders | Mental disorders characterized by enduring, inflexible, and maladaptive personality traits that deviate markedly from cultural expectations; are self-perpetuating; pervade a broad range of situations, and either generate subjective distress or result in significant impairments in social, occupational, or other functioning. Onset in adolescence or early adulthood. | May increase or decrease appetite. Overall nutrition status may decline, or obesity may result. May respond to increased intake of ω-3 fats to 1-3 g/day. |

| Pervasive developmental disorders |

Group of disorders characterized by impairment of development in multiple areas, including the acquisition of reciprocal social interaction, verbal and nonverbal communication skills, and imaginative activity, and by stereotyped interests and behaviors. Included are autism, Rett syndrome, childhood disintegrative disorder, and Asperger syndrome. | Comprehension of information shared during nutrition counseling may be affected. Autism and Asperger syndrome may benefit from dietary and nutrition changes. |

| Premenstrual dysphoric disorder | Premenstrual syndrome viewed as a psychiatric disorder. Often referred to as PMS. | May increase or decrease appetite. Overall nutrition status may decline, or obesity may result. May benefit from increasing intake of ω-3 fats to 1-3 g/day. |

| Rumination disorder | Eating disorder seen in infants younger than 1 year of age; after a period of normal eating habits, the child begins excessive regurgitation and rechewing of food, which is then ejected from the mouth or reswallowed. | If untreated, death from malnutrition may occur. May require enteral or parenteral nutrition. |

| Schizoaffective disorder | A mental disorder in which a major depressive episode, manic episode, or mixed episode occurs along with prominent psychotic symptoms characteristic of schizophrenia. Symptoms of the mood disorder are present for a substantial portion of the illness, and the disturbance is not the result of the effects of a psychoactive substance. | May increase or decrease appetite. Overall nutrition status may decline, or obesity may result. May respond to increased intake of ω-3 fats to 1-3 g/day, preferably in combination with antipsychotic drugs. |

| Seasonal affective disorder | A cyclic mood disorder characterized by depression, extreme lethargy, increased need for sleep, hyperphagia, and carbohydrate craving. It intensifies most commonly in winter months and is hypothesized to be related to melatonin levels. In DSM-IV terminology called “mood disorder with seasonal pattern.” Often referred to as “winter blues” in common parlance. | May increase or decrease appetite. Overall nutrition status may decline, or obesity may result. May respond to increasing ω-3 fat intake to 1-3 g/day. May benefit from increasing protein intake to balance blood sugar levels. |

| Sleep disorder | Chronic disorders involving sleep. Primary sleep disorders comprise dyssomnias and parasomnias. Causes of secondary sleep disorders may include a general medical condition, mental disorder, or psychoactive substance. | May affect appetite, with increased intake common; night eating syndrome may present. Obesity may result. |

DHA, Docosahexaenoic acid; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, IV; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid.

Data from Merck manual of medical information. Accessed 23 October 2010 from http://www.mercksource.com/pp/us/cns/cns_home.jsp.

References

Antalis, CJ, et al. Omega-3 fatty acid status in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2006;75:299.

Calvo, MS, et al. Vitamin D intake: a global perspective of current status. J Nutr. 2005;135:310.

Campbell, IC, et al. Eating disorders, gene-environment interactions and epigenetics. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35:784.

Cunnane, S. Report on Dietary Intake of Essential Fatty Acids. International Society for the Study of Fatty Acids and Lipids. 2004.

Dangour, AD, et al. Effect of 2-y n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation on cognitive function in older people: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1725.

Dashwood, RH. Flavonoids. Micronutrient Information Center, Linus Pauling Institute. http://lpi.oregonstate.edu/infocenter/phytochemicals/flavonoids, 2008. [Accessed April 25, 2011 from].

Davis, BC, Kris-Etherton, PM. Achieving optimal essential fatty acid status in vegetarians: current knowledge and practical implications. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78(Suppl):640S.

Escott-Stump, S. Nutrition and diagnosis-related care, ed 7. Baltimore: Lippincott-Williams & Wilkins; 2012.

Freeman, MP, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids: evidence base for treatment and future research in psychiatry. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:1954.

Freeman, MP, et al. Randomized dose-ranging pilot trial of omega-3 fatty acids for postpartum depression. Acta Psych Scand. 2006;113:31.

Gouin, JP, et al. Altered expression of circadian rhythm genes among individuals with a history of depression. J Affect Disord. 2010;126:161.

Hallahan, B, et al. Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation in patients with recurrent self-harm. British J Psychiatry. 2007;190:188.

Harris, WS, et al. Towards establishing dietary reference intakes for eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids. J Nutr. 2009;139:804S.

Hibbeln, JR. From homicide to happiness: a commentary on omega-3 fatty acids in human society: Cleave Award Lecture. Nutr Health. 2007;19:9.

Hibbeln, JR. Seafood consumption and homicide mortality. A cross-national ecological analysis. World Rev Nutr Diet. 2001;88:41.

Hibbeln, JR, Davis, JM. Considerations regarding neuropsychiatric nutritional requirements for intakes of omega-3 highly unsaturated fatty acids. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2009;81:179.

Hibbeln, JR, et al. Maternal seafood consumption in pregnancy and neurodevelopmental outcomes in childhood (ALSPAC study): an observational cohort study. Lancet. 2007;369:578.

Hoogendijk, WJ, et al. Depression is associated with decreased 25-hydroxyvitamin D and increased parathyroid hormone levels in older adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:508.

Institute of Medicine. Dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D. www.iom.edu/vitamind, 2010. [Accessed 22 December 2010 from].

Jazayeri, S, et al. Comparison of therapeutic effects of omega-3 fatty acid eicosapentaenoic acid and fluoxetine, separately and in combination, in major depressive disorder. Aust New Zealand J Pysch. 2008;42:192.

Jellin, J. Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database. Therapeutic Research Faculty. Stockton, CA 2011, Accessed April 24, 2011 from http://naturaldatabase.therapeuticresearch.com.

Jensen, GL. Drug-Induced Hyperphagia: What Can We Learn From Psychiatric Medications? J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2008;32:578.

Kiecolt-Glaser, JK. Stress, food, and inflammation: psychoneuroimmunology and nutrition at the cutting edge. Psychosom Med. 2010;72:365.

Koletzko, B, et al. for the Perinatal Lipid Intake Working Group: Dietary fat intakes for pregnant and lactating women. Br J Nutr. 2007;98:873.

Kris-Etherton, PM, Innis, S. Position of the American Dietetic Association and Dietitians of Canada: dietary fatty acids. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107:1599.

Marangell, LB, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the omega-3 fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid in the treatment of major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:996.

Martins, JG. EPA but not DHA appears to be responsible for the efficacy of omega-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation in depression: evidence from a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Am Coll Nutr. 2009;28:525.

Mihm, S, Does Eating Salmon Lower the Murder Rate? The New York Times Magazine 2006. April 16. Accessed Mar 22, 2011 from. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/16/magazine/16wwln_idealab.html

Muldoon, MF, et al. Serum phospholipid docosahexaenoic acid is associated with cognitive functioning during middle adulthood. J Nutrition. 2010;140:848.

Murphy, JM, et al. Obesity and weight gain in relation to depression: findings from the Stirling County Study. Int J Obes. 2009;33:335.

Richardson, AJ, Puri, BK. The potential role of fatty acids in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2000;63(1/2):79.

Richardson, AJ, Montgomery, P. Omega-3 fatty acids in ADHD and related neurodevelopmental disorders. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2006;18:155.

Spencer, JP. The impact of fruit flavonoids on memory and cognition. Br J Nutr. 2010;104:40S.

Stewart, R, et al. Relationship between vitamin D levels and depressive symptoms in older residents from a national survey population. Psychosomatic Med. 2010;72:608.

Vannice, GK. Cognition, aging and omega-3 fatty acids. J Applied Nutrition. 2005;55(1):2.

Vannice, GK. N-3s from fish and the risk of metabolic syndrome. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110:1014.

Williams, RJ, et al. Flavonoids: antioxidants or signaling molecules? Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;36:838.

Whalley, LJ, et al. Cognitive aging, childhood intelligence, and the use of food supplements: possible involvement of omega-3 fatty acids. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:1650.

Wilkins, CH, et al. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with low mood and worse cognitive performance in older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:1032.

World Health Organization. Mental health. http://www.who.int/en/, 2010. [Accessed 3 November 2010 from].

Zlojutro, M, et al. Genome-wide association study of theta band event-related oscillations identifies serotonin receptor gene HTR7 influencing risk of alcohol dependence. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2 November 2010. [[Epub ahead of print.]].