Nutrition in Eating Disorders

Eating disorders (EDs) are debilitating psychiatric illnesses characterized by a persistent disturbance of eating habits or weight control behaviors that result in significantly impaired physical health and psychosocial functioning. American Psychiatric Association (APA) diagnostic criteria are available for anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS), and binge eating disorder (BED). Childhood eating disturbances and the female athlete triad are also characterized by disordered eating and weight control behaviors (see Chapters 22 and 24).

Diagnostic Criteria

Diagnostic criteria for EDs have been established by the APA and are currently published in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV, TR (DSM-IV-TR); however, these criteria are currently under revision. For an update on the status of proposed revisions, the reader is referred to the following APA website: http://www.dsm5.org.

Anorexia Nervosa

A core clinical feature of anorexia nervosa (AN) is voluntary self-starvation resulting in emaciation. The reported lifetime prevalence of AN in women is 0.3% to 3.7%, depending on how strictly diagnostic criteria are defined (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2006). Among men, lifetime prevalence has recently been estimated at 0.3% (Treasure et al., 2010). AN is more prevalent in Westernized, postindustrialized societies; however, more global distribution of EDs (Becker, 2004), including third world countries is expected. Genetic, biologic, and psychosocial factors contribute to the pathogenesis of this disorder (Treasure et al., 2010).

Initial presentation of AN typically occurs during adolescence or young adulthood; however, later onset (i.e., initial onset at age 25 or older) may develop in response to adverse life events. Incidence rates for AN among middle-age women (older than age 50) account for less than 1% of newly diagnosed AN patients (APA, 2006).

Criteria for the establishment of a diagnosis of AN were first published in 1972 by Feighner and associates. The APA first published criteria for the diagnosis of AN in 1980; however, it was not until 1987 that the APA recognized AN and BN as two separate and distinct clinical entities. See Box 23-1 for the current diagnostic criteria for AN.

The DSM-IV-TR defines AN “refusal to maintain a body weight at or above a minimally normal weight for age and height (e.g., body weight less than 85% of that expected)” (APA, 2000). The weight deficit may occur secondary to purposeful weight loss or manifest as failure to gain weight during periods of linear growth in children and adolescents. The DSM-5 is likely to eliminate the 85% cutoff point for body weight deficit.

Determination of “minimally normal weight” is problematic. Metropolitan Life Insurance Company weight standards are often used; however, recommended weight for height differs between the 1959 and 1983 tables. Dietitians often calculate desirable body weight using the Hamwi method.* This is not recommended in patients with an ED because it calculates a “normal” body weight much lower than other standards. Use of BMI has become increasingly accepted in the management of AN patients. Although a body mass index (BMI) of 19-25 kg/m2 is considered normal for most healthy individuals, a BMI of 19-20 kg/m2 represents a low-normal target body weight for AN patients (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2005).

In children and adolescents, growth records should be obtained to determine if linear growth has deviated from premorbid height curves. If stunting has occurred, calculation of the weight deficit should be based on the premorbid height percentile. In 11- to 17-year-olds a normal body weight can be derived from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) weight and height tables (see Appendixes 11 and 15).

BMI norms (see Appendixes 12 and 16) vary with age; therefore assessment of BMI in children and adolescents should be related to BMI percentiles (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2005). Once again, if growth retardation is suspected, assessment of BMI should be based on expected rather than actual height. A BMI in the range of the 14th to 39th percentile can be used to assign an initial treatment goal weight, with adjustments made for prior weight, stage of pubertal development, and anticipated growth (Golden et al., 2008).

Patients with AN have body image distortion, causing them to feel fat despite their often cachectic state. Some individuals feel overweight all over, whereas others are overly concerned about the fatness of a specific body part such as the abdomen, buttocks, or thighs.

Amenorrhea, defined as the absence of at least three consecutive menstrual cycles in postmenarcheal women, is a problematic diagnostic criterion because some patients continue to menstruate regardless of a low body weight (Attia and Roberto, 2009); this criterion will most likely be eliminated from DSM-5 to be released soon. Development of AN during prepubescence may result in arrested sexual maturation and delayed menarche (primary amenorrhea). Young adolescent males with AN may have estrogen and testosterone deficiency and arrested growth and sexual development.

AN is categorized into two diagnostic subtypes: restricting and binge eating and purging. The restricting type is characterized by food restriction without binge eating or purging (self-induced vomiting or misuse of laxatives, enemas, or diuretics). Binge eating and purging is characterized by regular episodes of binge eating or purging behavior. Patients may initially present with the restricting subtype but migrate to the binge-and-purge subtype as the duration of their illness progresses.

Psychological features associated with AN include perfectionism, compulsivity, harm avoidance, feelings of ineffectiveness, inflexible thinking, overly restrained emotional expression, and limited social spontaneity. Several psychiatric conditions may also coexist with AN, and these include depression, anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), personality disorders, and substance abuse.

Lifetime comorbid depression has been reported in 50% to 75% of AN patients; however, symptoms may remit during the course of nutrition rehabilitation and weight restoration. Because the rate of suicide is greater among individuals with AN than in the general population, ongoing psychiatric assessment is critical More than 40% of AN patients also have OCD. Onset of OCD frequently predates AN, and many patients remain symptomatic despite weight restoration (APA, 2006).

Crude mortality rates range from 0% to 8% across studies, with a cumulative mortality rate of 2.8% (Keel, 2010). Malnutrition, dehydration, and electrolyte abnormalities may precipitate death by inducing heart failure or fatal arrhythmias (McCallum et al., 2006). Overall, approximately 50% of deaths are attributed to medical complications directly related to AN (Steinhausen, 2002).

Bulimia Nervosa

Bulimia nervosa (BN) is a disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of binge eating followed by one or more inappropriate compensatory behaviors to prevent weight gain. These behaviors include self-induced vomiting, laxative misuse, diuretic misuse, compulsive exercise, or fasting. The lifetime prevalence of BN among young adult women in the United States is estimated to be 1% to 3%. The rate of occurrence in men is approximately one tenth that in women.

Unlike AN patients with binge-and-purge subtype, patients with BN are typically within the normal weight range. Like their AN counterparts, these individuals place considerable importance on body shape and size, and they are often frustrated by their inability to attain an underweight state.

It is commonly thought that vomiting is the predominant feature of BN; however, it is the binge eating behavior that is central to the diagnosis. A binge is consumption of an unusually large amount of food in a discrete period (usually approximately 2 hours). There is a sense of lack of control over the eating episode. Although the amount of food and caloric content of a binge vary, binges are often in the range of 1000 to 2000 calories (Fairburn and Harrison, 2003). Although BN patients typically binge on energy-dense foods like desserts and savory snacks, binges can also include lower-calorie foods like fruit and salad. Patients may report a binge episode when the amount of food consumed is clearly not excessive. Although these “subjective binges” may not support a diagnosis of BN, these individuals have feelings about their eating behavior that merit further exploration.

BN patients engage in compensatory behaviors intended to offset food binges. The choice of compensatory behaviors further classifies BN into purging and nonpurging subtypes. Patients with purging type BN regularly engage in self-induced vomiting or the misuse of laxatives, enemas, or diuretics. Those with nonpurging-type BN do not regularly engage in purging behaviors but rather fast or excessively exercise to compensate for their binge. To meet full DSM-IV-TR criteria for BN bingeing, both binge eating and recurrent inappropriate compensatory behaviors must occur, on average, at least twice a week for 3 months; the frequency at which these behaviors are required to occur are likely to decrease in the upcoming DSM-5. Current APA diagnostic criteria for BN are listed in Box 23-1.

Adverse emotional states such as labile mood, frustration, anxiety, and impulsivity are often found in patients with BN. Psychiatric comorbidities, including depression, anxiety disorders, personality disorders, substance abuse, and self-injurious behaviors, are also common in BN. Compared with AN, BN patients are usually embarrassed and distressed by their symptoms, making it easier to engage them in treatment.

Causal factors proposed for the development of BN include addictive, family, sociocultural, cognitive-behavioral, and psychodynamic models (APA, 2006). BN, with or without comorbid psychiatric illness, should be treated and monitored by a mental health professional.

Mortality rates for BN are lower than those for AN. Crude mortality rates range from 0% to 2% across studies, with a cumulative mortality rate of 0.4% (Keel and Brown, 2010).

Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified

Under DSM-IV, approximately half of the individuals with EDs fall into the eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS) diagnostic group. Essentially these individuals meet most, but not all, of the criteria for AN or BN (e.g., a woman might meet all diagnostic criteria for AN except amenorrhea; a previously obese patient who, despite extreme weight loss, pathologic eating behavior, and amenorrhea fails to meet the AN criterion of body weight less than 85% of expected; a person who binges and purges, but with less frequency or for a shorter duration, than is specified for BN; or the individual who does not binge but vomits after eating a normal-size meal or snack). Clinically the EDNOS patient should receive treatment consistent with reasonable and customary care for either AN or BN. Inadequate treatment may lead to the development of full criteria AN or BN. In addition, patients who meet criteria for BED, a diagnostic group for research purposes only, are clinically diagnosed with EDNOS. See Box 23-1 for APA diagnostic criteria for EDNOS. Proposed revisions to the diagnostic criteria (DSM-V) are likely to result in a greater number of patients meeting criteria for AN and BN, and fewer meeting criteria for a subclinical ED (i.e., EDNOS).

Binge Eating Disorder

Research criteria for binge eating disorder (BED) are listed in Box 23-1. Binge eating, similar to that seen in BN, is characteristic of BED; however, there are no inappropriate compensatory behaviors after the binge. Binge episodes must occur at least 2 days per week for a period of 6 months.

Persons with BED experience a feeling of powerlessness over their eating, similar to that felt by BN patients. Significant emotional distress characterized by feelings of disgust, guilt, and depression occurs after a binge. Onset of BED generally occurs in late adolescence or in the early twenties, with women being 1.5 times more likely to develop this disorder than men.

Most patients with this disorder are overweight, with 15% to 50% prevalence among participants in weight-control programs. Patients with BED may have a higher lifetime prevalence of major depression, substance abuse, and personality disorders.

Eating Disorders in Childhood

Onset of EDs most typically occurs during adolescence and young adulthood. When an ED is suspected in a child or young teen, use of DSM criteria may be problematic because clinical presentation often differs from that seen in older adolescents and young adults. Complaints of nausea, abdominal pain, and difficulty in swallowing may coexist with concerns about weight, shape, and body fatness. Food avoidance, self-induced vomiting, and excessive exercise may occur, but laxative misuse is uncommon.

Any child or adolescent practicing unhealthy weight-control practices or thinking obsessively about food, body weight or shape, or exercise may be at risk for an ED. Other obsessive behaviors and depression may coexist in these children as well. Early-onset AN may result in delayed or stunted growth, osteopenia, and osteoporosis. AN has been reported in children as young as 7 years of age. The boy/girl ratio may be higher in this younger age group, and it appears in many different cultures and ethnic groups. BN in children is rare (APA, 2006).

The relationship between problematic childhood eating behaviors and subsequent development of EDs in later life is of concern. A longitudinal study of 800 children found that eating conflicts, food struggles, and unpleasant meals were risk factors for the later development of an ED (Kotler et al., 2001).

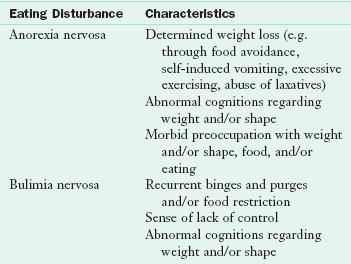

Childhood eating disturbances described by Bryant-Waugh (2007) include AN and, rarely, BN, as well as food avoidance emotional disorder, selective eating, restrictive eating, food refusal, functional dysphagia, and pervasive refusal syndrome (Table 23-1). Changes in the diagnostic criteria for childhood EDs have also been proposed for DSM-5 and are being developed (Bryant-Waugh et al., 2010).

Treatment Approach

Treatment of EDs requires a multidisciplinary approach that includes psychiatric, psychological, medical, and nutrition interventions. Treatment, provided at several levels of care depending on severity of illness, includes inpatient hospitalization, residential treatment, day hospitalization, intensive outpatient treatment, and outpatient treatment.

Inpatient treatment can be provided on a psychiatric or medical unit; a behavioral protocol developed specifically for the management of eating-disordered patients is highly recommended. Residential treatment programs also provide 24-hour care, but they are not usually equipped to handle the medically or psychiatrically unstable patient. Day hospital programs are also available. In this setting, patients initially receive 6 to 8 hours of specialized multidisciplinary treatment for 5 to 7 days per week. As treatment progresses, required attendance tapers off. The least intensive form of treatment is outpatient care; however, this still requires the ongoing, coordinated effort of physicians, psychotherapists, and nutritionists. Intensive outpatient treatment programs are also available. In this setting, patients receive several hours of multidisciplinary care each week. This may be scheduled in the late afternoon or early evening so the patient can attend after school or work.

The Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Eating Disorders (APA, 2006) provides comprehensive guidelines for the formulation and implementation of treatment plans in patients with AN, BN, EDNOS, and BED. These guidelines provide specific treatment recommendations (e.g., nutritional rehabilitation, medical management, psychological interventions, medication management) and level-of-care guidelines for patients with EDs. In addition, the Society for Adolescent Medicine (SAM, 2003), the American Academy of Pediatrics (2003), Committee on Adolescence (Rosen et al., 2010) and the American Dietetic Association (ADA, 2006) have published policy statements and positions regarding guidelines for effective treatment of EDs.

Clinical Characteristics and Medical Complications

Although EDs are classified as psychiatric illnesses, they are associated with significant medical complications, morbidity, and mortality. Numerous physiologic changes result from the weight-control habits of patients with AN and BN. Some are minor changes that occur secondary to reduced energy intake, some are pathologic alterations that may have long-term consequences, and a few represent potentially life-threatening conditions.

Anorexia Nervosa

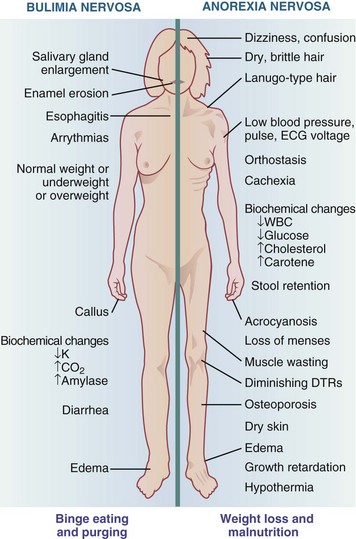

Patients with AN have a typical and distinctive appearance (Figure 23-1). Their cachectic and prepubescent body habitus often makes them look younger than their age. Common physical findings include lanugo, soft, downy hair growth, dry and brittle hair, hypercarotenemia, cold intolerance, and cyanosis of the extremities.

FIGURE 23-1 Physical and clinical signs and symptoms of bulimia nervosa and anorexia nervosa. DTRs, Deep tendon reflexes; ECG, electrocardiogram; WBC, white blood cell.

Protein-energy malnutrition with resultant loss of lean body mass is associated with reduced left ventricular mass and systolic dysfunction in AN. Cardiovascular complications include bradycardia, orthostatic hypotension, and cardiac arrhythmias. Protein-calorie malnutrition and deficiencies of thiamin, phosphorus, magnesium, and selenium have been associated with heart failure in AN; however, cardiac function is largely reversible with correction of dietary deficiencies and adequate weight restoration (Birmingham and Gritzner, 2007).

Gastrointestinal complications secondary to starvation include delayed gastric emptying, decreased small bowel motility, and constipation. Complaints of abdominal bloating and a prolonged sensation of abdominal fullness complicate the refeeding process.

Significant bone loss occurs frequently and early in the course of illness among both males and females, with an estimated 92% having bone mineral density (BMD) consistent with a diagnosis of osteopenia, and 40% having BMD consistent with a diagnosis of osteoporosis (Mehler and MacKenzie, 2009). Hormone replacement therapy and treatment with bisphosphonates have been found to be ineffective or inadequately studied in AN. Weight restoration is recommended as the first line of treatment for improved BMD in adolescent girls with AN (Golden, 2005). Unfortunately, AN patients often have a protracted course of illness associated with frequent relapse resulting in weight loss. Under these circumstances, reversibility of bone mineralization may be difficult and some studies demonstrate that bone density is not fully recoverable (Mehler and MacKenzie, 2009).

Children and adolescents with AN develop unique medical complications that affect normal growth and development such as growth retardation, reduction in peak bone mass, and structural abnormalities in the brain (SAM, 2003).

Bulimia Nervosa

Clinical signs and symptoms of BN are more difficult to detect because patients are usually of normal weight and secretive in behavior. When vomiting occurs, there may be clinical evidence such as (1) scarring of the dorsum of the hand used to stimulate the gag reflex, known as Russell sign; (2) parotid gland enlargement; and (3) erosion of dental enamel with increased dental caries resulting from the frequent presence of gastric acid in the mouth.

Chronic vomiting can result in dehydration, alkalosis, and hypokalemia. Common clinical manifestations include sore throat, esophagitis, mild hematemesis (vomiting of blood), abdominal pain, and subconjunctival hemorrhage. More serious gastrointestinal complications include Mallory-Weiss esophageal tears, rare occurrence of esophageal rupture, and acute gastric dilation or rupture. Ipecac, used to induce vomiting, may cause irreversible myocardial damage and sudden death.

Laxative abuse may lead to dehydration, elevation of serum aldosterone and vasopressin levels, rectal bleeding, intestinal atony, and abdominal cramps. Diuretic abuse may lead to dehydration and hypokalemia. Cardiac arrhythmias can occur secondary to electrolyte and acid-base imbalance caused by vomiting, laxative, and diuretic abuse. Although the profound amenorrhea associated with AN is uncommon in BN, menstrual irregularities may occur (see Figure 23-1).

Psychological Management

EDs are complex psychiatric illnesses that require psychological assessment and ongoing treatment. Evaluation of the patient’s cognitive and psychological stage of development, family history, family dynamics, and psychopathologic condition is essential for the development of a comprehensive psychosocial treatment program.

The long-term goals of psychosocial interventions in AN are (1) to help patients understand and cooperate with their nutritional and physical rehabilitation, (2) to help patients understand and change behaviors and dysfunctional attitudes related to their EDs, (3) to improve interpersonal and social functioning, and (4) to address psychopathologic and psychological conflicts that reinforce or maintain eating-disordered behaviors.

In the acute stage of illness, malnourished AN patients are typically negativistic and obsessional, making it difficult to conduct formal psychotherapy. At this stage of treatment, psychological management is often focused on positive behavioral reinforcement of weight restoration. This includes praise for positive efforts, reassurance, coaching, and encouragement. Inpatient behavioral management typically uses reinforcers that link attainment of privileges such as physical activity (versus bed rest), off-unit passes, and visitation privileges with attainment of targeted weight gain and improved eating behaviors.

Once acute malnutrition has been corrected and weight restoration is underway, the AN patient is more likely to benefit from psychotherapy. Psychotherapy can help the patient understand and change core dysfunctional thoughts, attitudes, motives, conflicts, and feelings related to his or her ED. Associated psychiatric conditions, including deficits in mood, impulse control, and self-esteem, as well as relapse prevention, should be addressed in the psychotherapeutic treatment plan. Several years of ongoing psychotherapy may be necessary for recovery.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a highly effective intervention for treatment of the acute symptoms of BN (Fairburn, 2008). Nevertheless, clinicians may combine elements of several types of psychotherapy during treatment. In some cases, adjunctive family and marital therapy may also be beneficial.

Several validated psychological instruments and questionnaires are available for the assessment of patients with EDs self-report measures may be used for screening purposes, whereas structured interviews are often used to confirm the diagnosis. Representative instruments include the Eating Attitudes Test, Eating Disorder Inventory, Eating Disorder Examination, Eating Disorders Questionnaire, and the Yale-Brown-Cornell Eating Disorder Scale (APA, 2006).

Nutrition Rehabilitation and Counseling

Nutrition rehabilitation includes nutrition assessment, medical nutrition therapy (MNT), nutrition counseling, and nutrition education. Although the EDs are distinct illnesses, similarities exist in nutritional consequences and nutritional management.

Nutrition Assessment

Nutrition assessment routinely includes a diet history and the assessment of biochemical, metabolic, and anthropometric indices of nutrition status.

Diet History

Guidelines should include assessment of energy intake, macronutrient, micronutrient, and fluid consumption, as well as eating attitudes, and eating behaviors (see Chapter 4).

Anorexia Nervosa

Patients with restricting subtype AN generally consume less than 1000 kcal/day. Assessment of typical energy intake prevents overfeeding or underfeeding at the inception of nutritional rehabilitation and opens a dialogue regarding caloric requirements during the refeeding and weight-maintenance phases of nutritional rehabilitation. Inadequate energy intake results in decreased consumption of carbohydrate, protein, and fat. Patients with AN were historically described as carbohydrate restrictors, but at present there is a tendency to avoid fat-containing foods. Observed food intake in 30 patients revealed that patients with AN consumed significantly less fat (15% to 20% of calories) than healthy controls. Percent of calories contributed by protein may be in the average to above-average range, but the adequacy of intake is relative to total caloric consumption. For example, the percentage of calories may remain the same, but as the calorie intake continues to drop, the actual amount of protein falls also. Patients with binge-purge subtype AN have more chaotic diet patterns, and energy consumption should be assessed across the spectrum of restriction and binge eating (Burd et al., 2009).

Vegetarianism is common among AN patients. The nutritionist should determine if adoption of the vegetarian diet predated the development of AN. A vegetarian diet adopted during the course of AN is a covert means of limiting food choice that may justifiably be considered as part of the psychopathologic findings of the disorder (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2005). Many treatment programs prohibit vegetarian diets during the weight restoration phase of treatment; others allow it. The relationship of social, cultural, and family influences, as well as religious beliefs relative to the patient’s vegetarian status must also be explored. If an AN patient is permitted to follow a vegan or vegetarian diet during weight restoration, care must be taken to provide adequate phosphate for prevention of hypophosphatemia, particularly during the initial stage of refeeding (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2005).

Inadequate caloric intake, limited variety in the diet, and poor food group representation result in inadequate vitamin and mineral consumption in AN. In general, micronutrient intake parallels macronutrient intake; thus AN patients who consistently restrict dietary fat are at greater risk for inadequate essential fatty acid intake and fat-soluble vitamin intake. Based on a 30-day diet history, Hadigan and colleagues (2000) found that more than 50% of 30 AN patients failed to meet dietary reference intake requirements for vitamin D, calcium, folate, vitamin B12, magnesium, copper, and zinc.

When obtaining a diet history, typical fluid intake should also be determined because abnormalities in fluid balance are prevalent in this population. Some patients severely restrict intake because they are intolerant of feeling full after fluid ingestion, whereas others drink excessive amounts, attempting to stave off hunger. Extremes in fluid restriction or ingestion may require monitoring of urine specific gravity and serum electrolytes.

Many AN patients consume excessive amounts of artificial sweeteners and artificially sweetened beverages (Marino et al., 2009). Use of these products should be addressed during the course of nutrition rehabilitation.

Bulimia Nervosa

Chaotic eating, ranging from restriction to normal eating to binge eating, is a hallmark feature of bulimia nervosa Energy intake in BN can be unpredictable. The caloric content of a binge, the degree of caloric absorption after a purge, and the extent of calorie restriction between binge episodes make assessment of total energy intake challenging. Bulimic patients assume that vomiting is an efficient mechanism for eliminating calories consumed during binge episodes; however, this is a common misconception. In a study of the caloric content of foods ingested and purged in a feeding laboratory, it was determined that, as a group, BN subjects consumed a mean of 2131 kcal during a binge and vomited only 979 kcal afterward (Kaye et al., 1993). As a rule of thumb, patients should be advised that approximately 50% of energy consumed during a binge is retained.

Because of day-to-day variability, a 24-hour recall is not a particularly useful assessment tool. To assess energy intake, it is helpful to estimate daily food consumption over the course of a week. First determine the number of nonbinge days (which may include restrictive and normal intake days) and approximate their caloric content; then determine the number of binge days and approximate caloric content, and deduct 50% of the caloric content of binges that are purged (vomited); finally, average the caloric intake over the 7-day period. Determination of this average energy intake, as well as the range of intake, will be useful information for the counseling process.

Nutrient intake in patients with BN varies with the cycle of binge eating and restriction, and it is likely that overall diet quality and micronutrient intake is inadequate. A 14-day dietary intake study of 50 BN patients revealed that at least 50% of participants consumed less than two thirds of the recommended dietary allowance (RDA) for calcium, iron, and zinc on nonbinge days. Furthermore, 25% of participants still had inadequate intakes of zinc and iron when overall intake (i.e., binge and non-binge days) was assessed (Gendall, 1997). It is important to note that even when the diet appears adequate, nutrient loss will occur secondary to purging, thus making it difficult to assess true adequacy of nutrient intake. Use of vitamin and mineral supplements should also be determined but, once again, retention after purging must be considered.

Eating Behavior

Characteristic attitudes, behaviors, and eating habits seen in AN and BN are shown in Box 23-2. Food aversions, common in this population, include red meat, baked goods, desserts, full-fat dairy products, added fats, fried foods, and caloric beverages. Patients with EDs often regard specific foods or groups of foods as absolutely “good” or absolutely “bad.” Irrational beliefs and dichotomous thinking about food choices should be identified and challenged throughout the treatment process.

In the assessment it is important to determine unusual or ritualistic behaviors, which may include ingestion of food in an atypical manner or with nontraditional utensils; unusual food combinations; or the excessive use of spices, vinegar, lemon juice, and artificial sweeteners. Meal spacing and length of time allocated for a meal should also be determined. Many patients save their self-allotted food ration until late in the day; others are fearful of eating past a certain time of day.

Many AN patients eat in an excessively slow manner, often playing with their food and cutting it into small pieces. This is sometimes regarded as a tactic to avoid food intake, but it may also be an effect of starvation (Keys et al., 1950). Time limits for meal and snack consumption are frequently incorporated into behavioral treatment plans.

Many BN patients eat quickly, reflecting their difficulties with satiety cues. In addition, BN patients may identify foods they fear will trigger a binge episode. The patient may have an all-or-nothing approach to “trigger” foods. Although the patient may prefer avoidance, assistance with reintroduction of controlled amounts of these foods at regular times and intervals is helpful.

Biochemical Assessment

The marked cachexia of AN may lead one to expect biochemical indices of malnutrition (see Chapter 8), but this is rarely the case. Compensatory mechanisms are remarkable, and laboratory abnormalities may not be observed until the illness is far advanced.

Significant alterations in visceral protein status are uncommon in AN. Indeed, adaptive phenomena that occur in chronic starvation are aimed at the maintenance of visceral protein metabolism at the expense of the somatic compartment. Serum albumin levels are generally within normal limits, but may be masked by dehydration in early treatment (Swenne, 2004).

Despite consumption of a typically low-fat, low-cholesterol diet, a high total cholesterol level is commonly found in malnourished AN patients (Rigaud et al., 2009). Despite hyperlipidemia, a fat- and cholesterol-restricted diet is not warranted during nutritional rehabilitation. If hyperlipidemia predated the development of AN, or if a strong family history of hyperlipidemia is identified, the patient should be reassessed after weight restoration and a period of weight stabilization.

Patients with BN may also have abnormal lipid levels. Patients with BN are prone to eating low-fat, low-energy foods during the restriction phase and high-fat, high-sugar foods during binge episodes. Premature prescription of a low-fat, low-cholesterol diet may only reinforce this dichotomous approach to eating. Care must be taken to balance extremes in the types and amounts of foods consumed. An accurate lipid profile can be obtained only after a period of dietary stabilization. Patients with BN may also have difficulty complying with the fast required for an accurate lipid profile.

Low serum glucose results from a deficit of precursors needed for gluconeogenesis and glucose production. Thyroid hormone production tends to be normal, but the peripheral deiodination of thyroxine favors formation of the less metabolically active reduced triiodothyronine (rT3) rather than triiodothyronine (T3) resulting in low T3 syndrome (Figure 32-2). This metabolic state is characteristic of AN and typically resolves with weight restoration. Thyroid hormone replacement is not recommended (APA, 2006).

Vitamin and Mineral Deficiencies

Hypercarotenemia is a common finding in AN, attributed to mobilization of lipid stores, catabolic changes caused by weight loss, and metabolic stress. Excessive dietary intake of carotenoids is less common. Normalization of serum carotene occurs during the course of nutrition rehabilitation.

Despite obviously deficient diets, reports of clinical and biochemical findings of true deficiency diseases are uncommon. The decreased need for micronutrients in a catabolic state, use of vitamin supplements, and selection of micronutrient-rich foods may be protective. Documented cases of riboflavin, vitamin B6, thiamin, niacin, folate, and vitamin E deficiencies have been reported in lower-weight and more chronically ill patients with AN (Altinyazar et al., 2009; Castro, 2004; Jagielska et al., 2007; Prousky, 2003). Patients avoiding animal foods may also be at risk for B12 deficiency (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2005).

Iron requirements in AN are decreased secondary to amenorrhea and the overall catabolic state. At treatment onset, the hemoglobin level may be falsely elevated as a result of dehydration resulting in hemoconcentration. Malnourished patients may also have fluid retention, and associated hemodilution may falsely lower the hemoglobin level. In severely malnourished AN patients, iron use may be blocked. Loss of lean tissue results in decreased red blood cell mass. Iron released from red cell mass is bound to ferritin and stored. Saturated ferritin-bound iron stores increase the risk of unbound iron that may result in cell damage, and use of iron supplements should be avoided at this phase of treatment (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2005). During nutrition rehabilitation and weight restoration, ferritin-bound iron is taken out of storage; this is generally adequate to meet the need for cellular repair and increased red blood cell mass. Patients should, however, be periodically reassessed for depletion of their reserve and the possible need for supplemental iron later in treatment. Hutter and colleagues (2009) presents a comprehensive review of hematological changes that occur in AN.

Zinc deficiency may occur secondary to inadequate energy intake, avoidance of red meat, and the adoption of vegetarian food choices. Although zinc deficiency may be associated with altered taste perception and weight loss, there is no evidence that deficiency causes or perpetuates symptoms of AN. Although supplemental zinc is purported to enhance food intake and weight gain in AN patients, there is poor evidence to support this claim (Lock and Fitzpatrick, 2009).

Although the high prevalence of osteopenia and osteoporosis in AN is largely due to hormone imbalance and weight loss, concurrent dietary deficiencies of calcium, magnesium, and vitamin D likely contribute to the overall pathogenesis. Dual x-ray absorptiometry to determine the degree of impaired bone mineralization is recommended (see Chapter 25).

Fluid and Electrolyte Balance

Vomiting and laxative and diuretic use can result in significant fluid and electrolyte imbalances in patients with EDs. Laxative use may result in hypokalemia, and diuretic use can also cause hypokalemia and dehydration. Vomiting may result in dehydration, hypokalemia, and alkalosis with hypochloremia. Hyponatremia is another serious complication, but is seen less frequently.

Urine concentration is decreased, and urine output is increased in semistarvation. Edema may occur in response to malnutrition and refeeding. Depletion of glycogen and lean tissue is accompanied by obligatory water loss that reflects characteristic hydration ratios. For example, the obligatory water loss associated with glycogen depletion may be in the range of 600-800 mL. Varying degrees of fluid intake, ranging from restricted to excessive, may affect electrolyte values in AN patients (see Chapter 7).

Energy Expenditure

Resting energy expenditure (REE) is characteristically low in malnourished AN patients (de Zwaan et al., 2002). Weight loss, decreased lean body mass, energy restriction, and decreased leptin levels have been implicated in the pathogenesis of this hypometabolic state. Refeeding increases and normalizes REE in AN patients. An exaggerated diet-induced thermogenesis (DIT) has also been reported in AN during the course of refeeding (de Zwann et al., 2002). This may pose metabolic resistance to weight gain during the course of nutritional rehabilitation in patients with AN (see Chapter 2).

Patients with BN can have unpredictable metabolic rates. Dietary restraint between episodes of binge eating may place bulimic patients in a state of semistarvation (resulting in a hypometabolic rate). However, binge eating followed by purging can increase the metabolic rate secondary to a preabsorptive release of insulin, which activates the sympathetic nervous system (de Zwann et al., 2002).

Baseline and follow-up assessment of REE may be clinically useful throughout the course of nutritional rehabilitation (Dragani et al., 2006; Schebendach, 2003); however, access to standard indirect calorimetry is typically limited to research settings. Although portable, handheld devices like the MedGem have been increasingly popular in the general population, a recent study of AN patients found poor agreement between MedGem and a standard indirect calorimeter measurements of REE (Hlynsky et al., 2005).

Anthropometric Assessment

Patients with AN have protein-energy malnutrition characterized by significantly depleted adipose and somatic protein stores, but a relatively intact visceral protein compartment. These patients meet the criteria for a diagnosis of severe protein-energy malnutrition. A goal of nutritional rehabilitation is restoration of body fat and fat-free mass. Although these compartments do regenerate, the extent and rate vary.

Percent body fat can be estimated from the sum of four skinfold measurements (triceps, biceps, subscapular, and suprailiac crest) (see Figures 6-4, 6-5, and 6-6) using the calculations of Durnin and colleagues (Durnin and Rahaman, 1967; Durnin and Womersley, 1974) (see Appendix 24). This method has been validated against underwater weighing to assess percentage of body fat in adolescent girls with AN (Probst, 2001). A more accurate measurement of percentage of body fat can be obtained from underwater weighing or from a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan (see Figure 6-10) equipped with body composition software; however, these methods are not generally available in an office or clinic setting (see Chapter 6 on Physical Assessment).

Bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) is more readily available, but shifts in intracellular and extracellular fluid compartments in patients with severe EDs may affect the accuracy of body fat measurement. To improve the validity of BIA measurement in AN patients (see Figure 6-9), the measurement should be done in the morning before ingestion of all food and liquid, using a reclining chair that is always reclined to the same position to prevent differential pooling of fluids (Sunday and Halmi, 2003). A comparison of body composition measurements assessed by several impedance methods, as well as DEXA, has been reported in AN patients and healthy controls (Moreno et al., 2008).

For practical purposes the midarm muscle circumference, derived from midarm circumference and triceps skinfold measurements (see Figure 6-7), can be easily obtained and compared with sex- and age-matched population standards (see Appendixes 25 and 26). Baseline and follow-up measurements can be easily obtained during nutritional rehabilitation.

Body weight is assessed and routinely monitored in patients with EDs. In AN weight gain is necessary. In BN the short-term goal should be weight maintenance. Although weight loss may be warranted, this cannot be addressed until chaotic eating patterns are stabilized.

Rate of weight gain in AN may be affected by hydration status, glycogen stores, metabolic factors, and changes in body composition (Box 23-3). Rehydration and replenished glycogen stores contribute to weight gain during the first few days of refeeding. Thereafter weight gain results from increased lean and fat stores. It is generalized that one needs to increase or decrease caloric intake by 3500 kcal to cause a 1-lb change in body weight, but the true energy cost depends on the type of tissue gained. More energy is required to gain fat versus lean tissue, but weight gain may be a mix of fat and lean tissue.

In adult women with AN, short-term weight restoration has been associated with a significant increase in truncal fat with central adiposity (Grinspoon, 2001; Mayer, 2005; Mayer et al., 2009); however, this abnormal distribution appears to normalize within 1 year of weight maintenance (Mayer et al., 2009). In adolescent girls with AN, short-term weight restoration is associated with normalization of body fat without increased central adiposity (de Alvaro et al., 2007; Misra, 2003).

The anthropometric status of patients with EDs should be assessed and monitored regularly (see Chapter 6). The patient’s goal weight can be determined by various methods, none of which is perfect. The height, weight, and BMI percentile tables of the NCHS should be used to assess boys and girls up to 20 years of age (see Appendixes 11 and 12 and 15 and 16). A bone age can be obtained in adolescents with stunted height to determine catch-up growth potential.

If a patient is hospitalized, a daily preprandial, early-morning weight should be obtained. On an outpatient basis a gowned weight should be obtained on the same scale, at approximately the same time of day, at least once a week in early treatment. Before weigh-in the patient should void, and urine specific gravity should be checked for dehydration or fluid loading. If the patient claims to be unable to provide a urine specimen, the physician should examine the patient to see whether the bladder is full. Patients may resort to deceptive tactics (water loading, hiding heavy objects on their person, and withholding urine and bowel movements) to make a mandated weight goal.

Medical Nutrition Therapy and Counseling

Treatment of an ED may begin at one of four levels of care: outpatient, intensive outpatient, day treatment, inpatient. The registered dietitian (RD) is an essential part of the treatment team at all levels of care.

In AN the chosen level of care is determined by the severity of malnutrition, degree of medical and psychiatric instability, duration of illness, and growth failure. In some instances, treatment begins on an inpatient unit but is stepped down to a less intensive level of care as weight restoration progresses. In other instances, treatment begins on an outpatient basis; however, if the rate of weight gain is inadequate, care is stepped up to a more intensive level.

In BN treatment typically begins and continues on an outpatient basis. On occasion a BN patient may be directly admitted to an intensive outpatient or day treatment program. However, inpatient hospitalization is relatively uncommon and generally is of short duration and for the specific purpose of fluid and electrolyte stabilization.

Anorexia Nervosa

Guidelines for MNT in AN are summarized in Box 23-4. Goals for nutrition rehabilitation include restoration of body weight and normalization of eating patterns and behaviors. Although MNT is an essential component of treatment, guidelines are largely based on clinical experience rather than scientific evidence.

Weight restoration is essential for recovery. The medically unstable, severely malnourished, or growth-retarded patient typically requires supervised weight gain in a specialized hospital unit or residential ED treatment program. In these settings, the energy prescription and desired rate of weight gain are usually determined by the medical doctor or the treatment team. Treatment programs often have three phases to the weight restoration process: weight stabilization and prevention of further weight loss, weight gain, and weight maintenance. Although the duration of these phases vary, the weight restoration process is typically the longest and is obviously influenced by patient’s state of malnutrition.

Treatment plans typically include a targeted rate of expected rate of weight gain. Gains of 2 to 3 lb/week for the hospitalized patient and 0.5 to 1 lb/week for the outpatient are reasonable and attainable goals. Although the initial calorie prescription may be in the range of 1000 to 1600 kcal/day (30 to 40 kcal/kg of body weight per day), progressive increases in energy intake will be needed to promote a consistent and targeted rate of weight gain. To accomplish this, the caloric prescription is often increased in 100 to 200 calorie increments every 2 to 3 days. In some treatment programs, however, the prescription is increased in larger increments (e.g., in 500-calorie increments) (Yager and Andersen, 2005).

Aggressive refeeding of severely malnourished AN patients (i.e., those weighing less than 70% standard body weight) may precipitate life-threatening complications of the refeeding syndrome during the first week of oral, nasogastric, or intravenous refeeding. Manifestations of the syndrome are fluid and electrolyte imbalance; cardiac, neurologic, and hematologic complications; and sudden death. High-risk patients need to be carefully monitored with daily measurements of serum phosphorus, magnesium, potassium, and calcium for the first 5 days of refeeding and every other day for several weeks thereafter. Supplemental phosphorus, magnesium, and potassium may be given orally or intravenously. Children and adolescents with AN may be at increased risk for refeeding syndrome and care must be taken not to over-prescribe calories in this age group (O’Connor and Goldin, 2010) (see Chapter 14).

Caloric prescriptions in the range of 3000 to 4000 kcal/day (70 to 100 kcal/kg of body weight per day) may ultimately be needed later in the course of weight restoration, and male AN patients may require even more—4000 to 4500 kcal/day (APA, 2006). Changes in REE, DIT, and the type of tissue gained are all factors. In addition, the energy cost of physical activity must be considered because many AN patients expend significant amounts of energy in physical activity or fidgeting behavior (de Zwann et al., 2002).

Patients who require extraordinarily high energy intakes should be questioned or observed for discarding of food, vomiting, exercising, and excessive physical activity, including fidgeting. After the goal weight is attained, the caloric prescription may be slowly decreased to promote weight maintenance. However, caloric prescriptions may remain at higher levels in adolescents with the potential for continued growth and development.

AN patients receiving care in less structured treatment settings such as outpatient treatment programs may be particularly resistant to formalized meal plans. A practical approach may be the addition of 200 to 300 calories per day to the patient’s typical (baseline) energy intake. However, the nutritionist must carefully query and assess intake as these patients may overestimate their food and energy consumption.

Once the caloric prescription is calculated, a reasonable distribution of macronutrients must be determined. Patients may express multiple food aversions. Extreme avoidance of dietary fat is common, but continued omission will make it difficult to provide concentrated sources of energy needed for weight restoration. A dietary fat intake of approximately 30% of calories is recommended. This can be accomplished easily when AN patients are treated on inpatient units or in day hospital programs. However, on an outpatient basis small, progressive increases in dietary fat intake rather than a set optimal amount right away may be met with less resistance. Although some patients will accept small amounts of added fat (such as salad dressing, mayonnaise, or butter), many do better when the fat content is less obvious (as in cheese, peanut butter, granola, and snack foods). Encouraging the gradual change from fat-free products (fat-free milk) to low-fat products (1% or 2% milk) and finally to full-fat items (whole milk) is also acceptable to some patients.

A protein intake in the range of 15% to 20% of total calories is recommended. To ensure adequacy the minimum protein prescription should equal the RDA for age and sex in grams per kilogram of ideal body weight (see inside front cover). Vegetarian diets are often requested but should be discouraged during weight restoration.

Carbohydrate intake in the range of 50% to 55% of calories is well tolerated. Sources of insoluble fiber should be included for optimal health, but also to relieve the constipation frequently seen in this population.

Although vitamin and mineral supplements are not universally prescribed, the potential for increased needs during the later stages of weight gain must be considered. Prophylactic prescription of a vitamin and mineral supplement providing 100% of the RDA may be reasonable, but iron supplementation may be contraindicated early in treatment. During weight restoration, prophylactic thiamin supplementation, at a dose of 25 mg/day, may also be warranted; and higher doses may be required if thiamin deficiency is biochemically confirmed (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2005). Owing to the increased risk of low BMD, liberal amounts of calcium and vitamin D–rich foods must be encouraged. There is, however, no clear consensus on the use of calcium and vitamin D supplements in this population., however vitamin D status should be assessed. See Chapter 8.

Delayed gastric emptying with complaints of abdominal distention and discomfort after eating are common in AN. In early treatment intake is generally low and can be tolerated in three meals per day. However, as the caloric prescription increases, between-meal feedings become essential. The addition of an afternoon or evening snack may relieve the physical discomfort associated with larger meals, but some patients express feelings of guilt for “indulging” between meals. Commercially available, defined-formula liquid supplements containing 30 to 45 calories per fluid ounce are often prescribed once or twice daily. Patients are fearful that they will become accustomed to the large amount of food required to meet increased caloric requirements; thus use of a liquid supplement is appealing because it can easily be discontinued when the goal weight is attained.

Institutions vary with respect to their menu-planning protocol. In some institutions the meal plan and food choices are initially fixed without patient input. As treatment progresses and weight is restored, the patient generally assumes more responsibility for menu planning. In other inpatient programs the patient participates in menu planning from the beginning of treatment. Some institutions have established guidelines that the patient must comply with to maintain the “privilege” of menu planning. Guidelines may require a certain type of milk (e.g., whole versus low fat), and the inclusion of specific types of foods such as added fats, animal proteins, desserts, and snacks. A certain number of servings from the different food groups may be prescribed at different calorie levels. Meal-planning systems also vary among treatment programs. Some design their own, others use food group exchanges or the MyPlate system, and some formulate an individualized meal plan for each patient.

There are no outcome studies to suggest that one method of meal planning is superior to another, and treatment programs tend to have their own philosophy about menu planning. Despite differences in protocol, AN patients consistently find it difficult to make food choices. The RD can be extremely helpful in providing a structured meal plan and guidance in the selection of nutritionally adequate meals. In a study of recently weight-restored, hospitalized AN patients, those who selected more energy-dense foods and a diet with greater variety had better treatment outcomes during the 1-year period immediately following hospital discharge, and this effect was independent of total caloric intake (Schebendach et al., 2008).

In an outpatient setting the treatment team obviously has less control over the AN patient’s food choices, energy intake, and energy distribution. Under these circumstances the RD must use counseling skills to begin the process of developing a plan for nutritional rehabilitation. AN patients are typically precontemplative and, at best, ambivalent about making changes in eating behavior, diet, and body weight; some are defiant and hostile on initial presentation. At this point the nutrition counselor’s use of motivational interviewing techniques may help the AN patient resolve ambivalence toward the idea of change and move beyond the precontemplative stage (see Figure 15-3). Use of cognitive behavior therapy may be useful in the nutrition counseling of AN patients (ADA, 2006); the reader is referred to Fairburn (2008) for a thorough review of these techniques.

Effective nutritional rehabilitation and counseling must ultimately result in weight gain and improved eating attitudes and behaviors. A comprehensive review of nutrition counseling techniques can be found in Chapter 15 and in Herrin (2003) and Stellefson Myers (2006).

Bulimia Nervosa

Guidelines for MNT in BN are summarized in Box 23-5. BN is described as a state of dietary chaos, characterized by periods of uncontrolled, poorly structured eating, which are often followed by a periods of restrained food intake. The nutritionist’s role is to help develop a reasonable plan of controlled eating while assessing the patient’s tolerance for structure. Because BN patients are hospitalized infrequently, nutrition counseling will most likely begin in an outpatient treatment setting.

In BN much of the patient’s eating and purging behavior is aimed at weight loss. Although weight reduction may be a reasonable long-term goal, immediate goals must be interruption of the binge-and-purge cycle, restoration of normal eating behavior, and stabilization of body weight. Attempts at dietary restraint for the purpose of weight loss typically exacerbate binge-purge behavior in BN patients.

Patients with BN have varying degrees of metabolic efficiency, which must be taken into account when prescribing the baseline diet. Assessment of REE along with clinical signs of a hypometabolic state such as a low T3 level and cold intolerance are useful in determining the caloric prescription. If a low metabolism is suspected, a caloric prescription of 1500 to 1600 calories daily is a reasonable place to start. Another technique that is helpful in establishing an initial caloric prescription is to base it on the patient’s present intake by using the following method:

1. For a typical week ask the patient to estimate the number of binge-purge days, binge-nonpurge days, moderate-intake days, and restrained-intake days.

2. Have the patient describe a typical food intake on a binge-purge day, a binge-nonpurge day, a moderate-intake day, and a restrained-intake day.

3. Estimate 50% of the caloric intake on the binge-purge days and 100% of caloric intake on the binge-nonpurge days, moderate-intake days, and restrained-intake days.

4. Calculate the total caloric intake during the 7-day period.

5. Calculate an average daily intake. The RD can then formulate an initial eating and meal plan based on this estimated average daily intake.

Body weight should be monitored with a goal of stabilization. If the patient’s weight is stabilized on a lower-than-average caloric intake, small but consistent increases in the caloric intake should be prescribed every 1 to 2 weeks. This will induce incremental increases in the metabolic rate (Schebendach, 2003).

BN patients need a great deal of encouragement to follow weight-maintenance versus weight-loss diets. They must be reminded that attempts to restrict caloric intake may only increase the risk of binge eating and that their pattern of restrained intake followed by binge eating has not facilitated weight loss in the past.

A balanced macronutrient intake is essential for the provision of a regular meal pattern. This should include sufficient carbohydrates to prevent craving and adequate protein and fat to promote satiety. In general, a balanced diet providing 50% to 55% of the calories from carbohydrate, 15% to 20% from protein, and 25% to 30% from fat is reasonable. Small amounts of dietary fat should be encouraged at each meal. As is the case with AN, this may be better tolerated when provided in a less obvious manner, such as in peanut butter, cheese, or whole milk.

Adequacy of micronutrient intake relative to the caloric prescription and variety of intake should be assessed. A multivitamin and mineral preparation may be prescribed to ensure adequacy, particularly in the initial phase of treatment.

Bingeing, purging, and restrained intake often impair recognition of hunger and satiety cues. The cessation of purging behavior coupled with a reasonable daily distribution of calories at three meals and prescribed snacks can be instrumental in strengthening these biologic cues. Many patients with BN are afraid to eat earlier in the day because they are fearful that these calories will contribute to caloric excess if they binge later. They may also digress from their meal plans after a binge, attempting to restrict intake to balance out the binge calories. Patience and support are essential in this process of making positive changes in their eating habits.

CBT, a highly structured psychotherapeutic method used to alter attitudes and problem behaviors by identifying and replacing negative, inaccurate thoughts and changing the rewards of the behavior, is the treatment of choice in BN (APA, 2006). When applied to an ED, CBT is typically a 20-week intervention that consists of three distinct and systematic phases of treatment: (1) establishing a regular eating pattern, (2) evaluating and changing beliefs about shape and weight, and (3) preventing relapse.

When the BN patient is receiving CBT, the RD can be instrumental in helping the patient establish a regular meal pattern (phase 1). However, the RD and the psychotherapist must maintain active communication to avoid overlap in the counseling sessions. If the BN patient is engaged in a type of psychotherapy other than CBT, the RD should incorporate more CBT skills into the nutrition counseling sessions (Herrin, 2003). See Fairburn (2008) for guidance on CBT techniques.

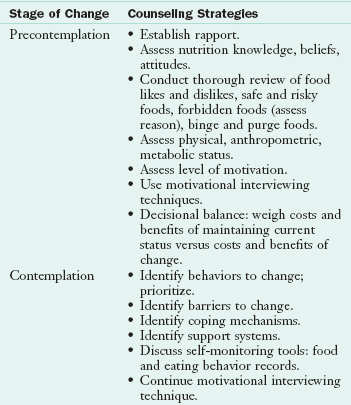

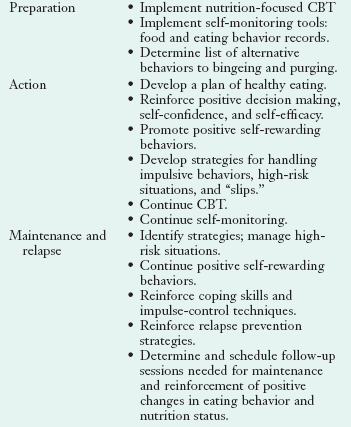

Patients with BN are typically more receptive to nutrition counseling than AN patients and less likely to present in the precontemplation stage of change. Suggested strategies for nutrition counseling at the precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance stages are given in Table 23-2 (see Chapter 15).

Binge Eating Disorder

Strategies for treatment of BED include nutrition counseling and dietary management, individual and group psychotherapy, and medication. Some treatment programs focus primarily on nutrition counseling and weight loss. Although successful weight loss and decreased frequency of binge eating episodes may result, relapse occurs often. Other treatment programs focus primarily on reduction of binge episodes rather than weight loss. Self-acceptance, improved body image, increased physical activity, and better overall nutrition are also goals of treatment in BED. Several self-help manuals are available for the treatment of BED (Sysko and Walsh, 2008), and these approaches can be augmented with guidance from psychotherapists and nutritionists.

Monitoring Nutritional Rehabilitation

Guidelines for patient monitoring are indicated in Box 23-6. The health professional, patient, and family must be realistic about treatment, which is often a long-term process. Although outcomes may be favorable, the course of treatment is rarely smooth, and clinicians must be prepared to monitor progress carefully.

Nutrition Education

Patients with EDs may appear quite knowledgeable about food and nutrition. Despite this, nutrition education is an essential component of their treatment plan. Indeed, some patients spend significant amounts of time reading nutrition-related information, but their sources may be unreliable, and their interpretation potentially distorted by their illness. Malnutrition may impair the patient’s ability to assimilate and process new information. Early- and mid-adolescent development is characterized by the transition from concrete to abstract operations in problem solving and directed thinking, and normal developmental issues must be considered when teaching adolescents with EDs (see Chapter 19).

Nutrition education materials must be thoroughly assessed to determine if language and subject matter are bias free and appropriate for AN and BN patients. For example, literature provided by many health organizations promotes a low-fat diet and low-calorie lifestyle for the prevention and treatment of chronic disease. This material is in direct conflict with a treatment plan that encourages increased caloric and fat intake for the purpose of nutritional rehabilitation and weight restoration.

Although the interactive process of a group setting may have advantages, these topics can also be effectively incorporated into individual counseling sessions. Topics for nutrition education are suggested in Box 23-7.

Prognosis

Relapse rates after weight restoration in AN are high, with as many as 50% of patients requiring rehospitalization within 1 year of inpatient treatment (Walsh et al., 2006). Follow-up studies suggest that two thirds of AN patients have enduring morbid food and weight preoccupation (APA, 2006). In general, adolescents have better outcomes than adults, and younger adolescents have better outcomes than older adolescents. Outcomes studies in treated BN patients suggest a short-term success rate of 50% to 70%; however, relapse rates in the range of 30% to 85% have also been reported (APA, 2006).

Academy for Eating Disorders: For Professionals Working in the Area of Eating Disorders

National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders

National Eating Disorders Association

http://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org

American Psychiatric Association

Proposed revisions to eating disorders diagnostic criteria: http://www.dsm5.org/ProposedRevisions

References

Altinyazar, V, et al. Anorexia nervosa and Wernicke Korsakoff’s syndrome: atypical presentation by acute psychosis. Int J Eat Disord. 2009. [[Epub ahead of print.]].

American Academy of Pediatrics. Policy statement: identifying and treating eating disorders. Pediatrics. 2003;111:204.

American Dietetic Association. Nutrition intervention in the treatment of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and other eating disorders. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:2073.

American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and statistical manual for mental disorders. text revision. ed 4. Washington, DC: APA Press; 2000.

American Psychiatric Association, Practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with eating disorders. ed 3. Am J Psychiatry. 2006. Accessed 1 October 2006 from. www.Psych.org/edu/cme/pgeatingdisorders3rdedition.cfm

Attia, E, Roberto, CA. Should amenorrhea be a diagnostic criterion for anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42:581.

Becker, AE. New global perspectives on eating disorders. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2004;28:433.

Birmingham, CL, Gritzner, S. Heart failure in anorexia nervosa: case report and review of the literature. Eating Weight Disord. 2007;12:e7.

Bryant-Waugh, R. Overview of the eating disorders. In Lask B, Bryant-Waugh R, eds.: Eating disorders in childhood and adolescence, ed 3, East Sussex, UK: Routledge, 2007.

Bryant-Waugh, R. Feeding and eating disorders in childhood. Int J Eat Disord. 2010;43:98.

Burd, C, et al. An assessment of daily food intake in participants with anorexia nervosa in the natural environment. Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42:371.

Castro, J, et al. Persistence of nutritional deficiencies after short-term weight recovery in adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2004;35:169.

de Alvaro, M, et al. Regional fat distribution in adolescents with anorexia nervosa: effect of duration of malnutrition and weight recovery. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2007;157:473.

de Zwann, M, et al. Research on energy expenditure in individuals with eating disorders: a review. Int J Eating Disord. 2002;31:361.

Dragani, B, et al. Dynamic monitoring of restricted eating disorders by indirect calorimetry: a useful cognitive model. Eating Weight Disord. 2006;11:e9.

Durnin, JVGA, Rahaman, MM. The assessment of the amount of body fat in the human body from measurements of skinfold thickness. Br J Nutr. 1967;21:681.

Durnin, JVGA, Womersley, J. Body fat assessed from total body density and its estimation from skinfolds thickness: measurements of 481 men and women aged from 16 to 72 years. Br J Nutr. 1974;32:77.

Fairburn, CG. Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. New York: Guilford Press; 2008.

Fairburn, CG, Harrison, PJ. Eating disorders. Lancet. 2003;361:407.

Feighner, JP, et al. Diagnostic criteria for use in psychiatric research. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1972;26:57.

Gendall, KA, et al. The nutrient intake of women with bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 1997;21:115.

Golden, NH, et al. Alendronate for the treatment of osteopenia in anorexia nervosa: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2005;90:3179.

Golden, NH, et al. Treatment goal weight in adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2008;41:301.

Grinspoon, S, et al. Changes in regional fat distribution and the effects of estrogen during spontaneous weight gain in women with anorexia nervosa. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;73:865.

Hadigan, CM, et al. Assessment of macronutrient and micronutrient intake in women with anorexia nervosa. Int J Eating Disord. 2000;28(3):284.

Herrin, M. Nutrition counseling in the treatment of eating disorders. New York: Brunner-Routledge; 2003.

Hlynsky, J, et al. The agreement between the MedGem indirect calorimeter and a standard indirect calorimeter. Eating Weight Disord. 2005;10:e83.

Hutter, G, et al. The hematology of anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42:293.

Jagielska, G, et al. Pellagra: a rare complication of anorexia nervosa. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;16:417.

Kaye, WH, et al. Amounts of calories retained after binge eating and vomiting. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:969.

Keys, A, et al. The biology of human starvation. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; 1950;vols 1 and 2.

Keel, PK, Brown, TA. Update on course and outcome in eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2010;43:195.

Kotler, LA, et al. Longitudinal relationships between childhood, adolescent, and adult eating disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:1434.

Lock, JD, Fitzpatrick, KK. Anorexia nervosa. Clin Evid. 2009;10:1001. [Mar].

Marino, JM, et al. Caffeine, artificial sweetener, and fluid intake in anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42:540.

Mayer, L, et al. Body fat redistribution after weight gain in women with anorexia nervosa. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:1286.

Mayer, ES, et al. Adipose tissue redistribution after weight restoration and weight maintenance in women with anorexia nervosa. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:1132.

McCallum, K, et al. How should the clinician evaluate and manage the cardiovascular complications of anorexia nervosa? Eating Disord. 2006;14(1):73.

Mehler, PS, MacKenzie, TD. Treatment of osteopenia and osteoporosis in anorexia nervosa: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42:195.

Misra, S, et al. Regional body composition in adolescents with anorexia nervosa and changes with weight recovery. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:1361.

Moreno, MV, et al. Assessment of body composition in adolescent subjects with anorexia nervosa by bioimpedance. Med Eng Phys. 2008;30:783.

O’Connor, GO, Goldin, J. The refeeding syndrome and glucose load. Int J Eat Disord. 2010. [[Epub ahead of print.]].

Probst, M, et al. Body composition of anorexia nervosa patients assessed by underwater weighing and skin-fold thickness measurements before and after weight gain. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;73:190.

Prousky, JE. Pellagra may be a rare secondary complication of anorexia nervosa: a systematic review of the literature. Alternative Med Rev. 2003;8:180.

Rigaud, D, et al. Hypercholesterolaemia in anorexia nervosa: frequency and changes during refeeding. Diabetes Metab. 2009;35:57.

2010. Rosen DS and the Committee on Adolescence. Identification and management of eating disorders in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2010;126:1240.

Royal College of Psychiatrists: Guidelines for the nutritional management of anorexia nervosa, Council Report CR130, July 2005.

Schebendach, J. The use of indirect calorimetry in the clinical management of adolescents with nutritional disorders. Adoles Med. 2003;14:77.

Schebendach, J, et al. Dietary energy density and diet variety as predictors of outcome in anorexia nervosa. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:810.

Society for Adolescent Medicine. Position paper: eating disorders in adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2003;33:96.

Steinhausen, HC. The outcome of anorexia nervosa in the 20th century. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1284.

Stellefson Myers, E. Winning the war within: nutrition therapy for clients with eating disorders, ed 2. Dallas, Tex: Helm Publishing; 2006.

Sunday, SR, Halmi, KA. Energy intake and body composition in anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Phys Behav. 2003;78:11.

Swenne, I. The significance of routine laboratory analyses in the assessment of teenage girls with eating disorders and weight loss. Eating Weight Disord. 2004;9:269.

Sysko, R, Walsh, BT. A critical evaluation of the efficacy of self-help interventions for the treatment of bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2008;41:97.

Treasure, J, et al. Eating disorders. Lancet. 2010;375:583.

Walsh, BT, et al. Fluoxetine after weight restoration in anorexia nervosa: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(22):2605.

Yager, J, Andersen, AE. Anorexia nervosa. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1481.

*Hamwi Method for women: 100 lb for the first 5 feet of height plus 5 lb per inch for every inch over 5 feet plus 10% for a large frame and minus 10% for a small frame. For men: 106 lb for the first 5 feet of height plus 6 lb per inch for every inch over 5 feet plus 10% for a large frame and minus 10% for a small frame.