Health Promotion of the Preschooler and Family

http://evolve.elsevier.com/wong/ncic

Alternative Child Care Arrangements, Ch. 12

Cognitive Development, Ch. 14

Dental Health, Ch. 14

Habits (Sleep), Ch. 6

Injury Prevention, Ch. 14

Limit Setting and Discipline, Ch. 3

School Phobia, Ch. 18

Sibling Rivalry, Ch. 14

Speech Impairment, Ch. 24

Temper Tantrums, Ch. 14

Working Mothers, Ch. 3

Promoting Optimum Growth and Development

The combined biologic, psychosocial, cognitive, spiritual, and social achievements during the preschool period (3 to 5 years of age) prepare preschoolers for their most significant change in lifestyle: entrance into school. Their control of bodily systems, experience of brief and prolonged periods of separation, ability to interact cooperatively with other children and adults, use of language for mental symbolization, and increased attention span and memory prepare them for the next major period: the school years. Successful achievement of previous levels of growth and development is essential for preschoolers to refine many of the tasks that were mastered during the toddler years.

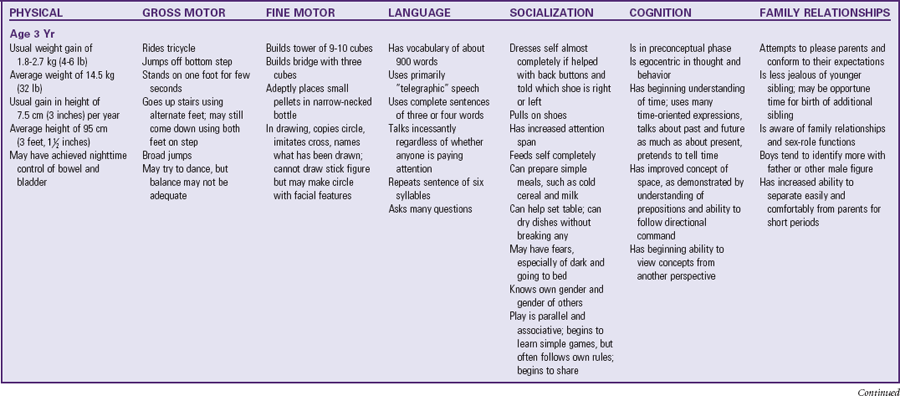

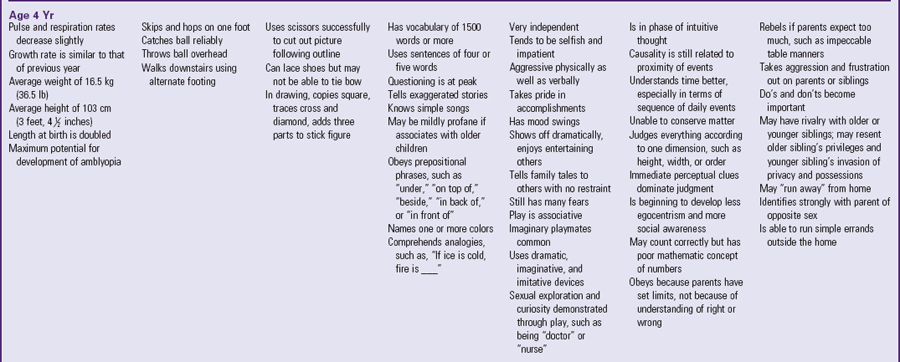

Biologic Development

The rate of physical growth slows and stabilizes during the preschool years. The average weight is 14.5 kg (32 lb) at 3 years, 16.5 kg (36.5 lb) at 4 years, and 18.5 kg (41 lb) at 5 years. The average weight gain remains approximately 2 to 3 kg (4.5 to 6.5 lb) per year.

Growth in height also remains steady at a yearly increase of 6.5 to 9 cm (2.5 to 3.5 inches). The legs of a preschooler, rather than the trunk, increase in length. The average height is 95 cm (37.5 inches) at 3 years, 103 cm (40.5 inches) at 4 years, and 110 cm (43.5 inches) at 5 years.

Physical proportions no longer resemble those of the squat, pot-bellied toddler. The preschooler is slender but sturdy, graceful, agile, and posturally erect. There is little difference in physical characteristics according to sex, except in factors such as dress and hairstyle.

Most organ systems can adjust to moderate stress and change. During this period, most children are toilet trained. For the most part, motor development consists of increases in strength and refinement of previously learned skills, such as walking, running, and jumping. However, muscle development and bone growth are still far from mature. Excessive activity and overexertion can injure delicate tissues. Good posture, appropriate exercise, and adequate nutrition and rest are essential for optimum development of the musculoskeletal system.

Gross and Fine Motor Behavior

By 36 months, preschoolers are walking, running, climbing, and jumping well. Refinement in eye-hand and muscle coordination is evident in several areas. At age 3, the preschooler rides a tricycle, walks on tiptoe, balances on one foot for a few seconds, and broad jumps. By age 4, the child skips and hops proficiently on one foot (Fig. 15-1) and catches a ball reliably. By age 5, the child skips on alternate feet, jumps rope, and begins to skate and swim.

Achievement in fine motor development is evident in the child’s increasingly skillful manipulation. Drawing shows several advancements in the perception of shape and the development of fine muscle coordination. The 3-year-old child copies a circle and imitates a cross and vertical and horizontal lines. He or she holds the writing instrument with the fingers rather than the fist. The child scribbles or scrawls drawings but can name what has been drawn. The 3-year-old is not able to draw a complete stick figure but draws a circle, later adds facial features, and by age 5 or 6 years can draw several parts (head, arms, legs, body, and facial features). Between 4 and 5 years of age, the child can trace a cross and copy a square. The triangle and diamond are usually the last geometric figures to be mastered, sometime between ages 5 and 6.

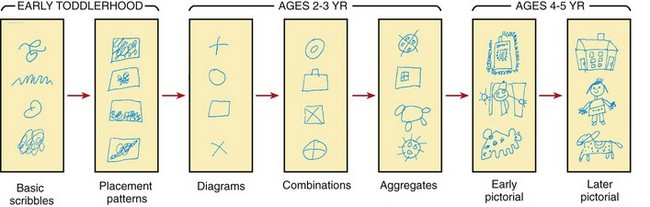

As children progress from scribbling to picture making, they advance through four distinguishable stages (Kellogg, 1969). In the placement stage, 15-month-old children place their earliest spontaneous scribblings on the paper in a specific placement pattern, such as in the center, all over, across the lower half, or across the page in a diagonal direction (Fig. 15-2). Approximately 17 different placement patterns appear by age 2 years and, once developed, are never lost.

Fig. 15-2 Sequential development in self-taught art. (From Kellogg R: Understanding children’s art. In Readings in psychology today, Del Mar, Calif, 1969, Communications/Research/Machines.)

By 3 years of age, children are in the shape stage. They draw single-line outline forms such as rectangles, circles, ovals, crosses, and other odd shapes. As soon as they draw diagrams, they almost immediately progress to the design stage, in which simple forms are drawn together to make structured designs. When two diagrams are united, the resulting design is called a combine. Three or more united diagrams produce an aggregate. Between the ages of 4 and 5, most children enter the pictorial stage, in which their designs are recognizable as familiar objects. Early pictorial drawings are suggestive of human figures, houses, animals, and trees. Later pictorial drawings are more clearly defined and recognizable; they are not representations of the actual object but aesthetically satisfying structures that resemble familiar objects. For example, the initial human figure drawing is a circle with arms attached to the head. It is more an aggregate drawing than any attempt to copy a human figure. Drawings of animals follow the human figure drawing but are only a slight modification, such as attaching ears to the top of the head.

Kellogg (1969) suggests that uninhibited scribbling and drawing are necessary for children to learn to read and that children who have been free to experiment and produce abstract forms have developed the mental set required for learning symbolic language. Scribbling and drawing also help develop the fine muscle skills and eye-hand coordination eventually required for making precise letters and numbers.

Drawing is also a tool used for assessing intelligence, personality development, and psychosocial adjustment. The precise value of using drawing to measure such concepts is still a nebulous science. However, children (especially school-age children) do reveal thoughts about themselves in their drawings. It is generally not necessary to have in-depth knowledge of children’s drawings to make assumptions about their significance. Being receptive to all the clues, both verbal and nonverbal, is essential to understanding how and what children are communicating to others (see Cultural Competence box).

Psychosocial Development

Developing a Sense of Initiative (Erikson)

If preschoolers have mastered the tasks of the toddler period, they are ready to face the developmental challenges of the preschool period. Erikson maintained that the chief psychosocial task of this period is acquiring a sense of initiative. Children are in a stage of energetic learning. They play, work, and live to the fullest and feel a real sense of accomplishment and satisfaction in their activities. Conflict arises when children overstep the limits of their ability and inquiry and experience guilt for not having behaved appropriately. Feelings of guilt, anxiety, and fear may also result from thoughts that differ from expected behavior.

A particularly stressful thought is wishing one’s parent dead. As a sense of rivalry or competition develops between the child and the same-sex parent, the child may think of ways to get rid of the interfering parent. In most situations, this contest is resolved when the child strongly identifies with the same-sex parent and peers during the school years. However, if that parent dies before the identification process is completed, the preschooler can be overwhelmed with guilt for having wished and therefore “caused” the death. Clarifying for children that wishes cannot make events occur is essential in helping them overcome their guilt and anxiety.

Development of the superego, or conscience, starts toward the end of the toddler years and is a major task for preschoolers. Learning right from wrong and good from bad is the beginning of morality (see Cultural Competence box). Children in this age-group are generally unable to understand why something is acceptable or unacceptable. They are aware of appropriate behavior primarily through punishment or reward and rely almost completely on parental principles for developing their own moral judgment. Verbal enforcement of limits is much more effective in this age-group than with toddlers. For example, to prevent injuries, parents need to supervise toddlers, keep them contained within protected areas, and tell them not to run into the street. The preschooler still needs close supervision but is much more aware of danger and can listen and obey in most instances. If allowed to disagree and question, they will develop socially acceptable behavior and independence in thought and action.

Oedipal Stage (Freud)

As soon as children comprehend their separateness as persons, they begin to realize that there are categories of objects, such as things, people, males, females, children, and adults. One of the principal goals in further differentiation of oneself from others is learning sex differences and sexually appropriate behavior.

Freud described this goal in psychosexual terms and labeled the period the oedipal, or phallic, stage. He believed that conflict arises when a boy realizes that his father is much stronger and more powerful than he. Subconsciously, he wishes that his father were dead so he could marry his mother (Oedipus complex). Concurrently, he notices physical sexual differences, specifically that boys have a penis and girls do not. In his mind, he supposes that girls have lost their penis for some wrongdoing. His guilt regarding his feelings toward his father makes him fear the same punishment of mutilation, resulting in the castration complex. Girls have similar wishes to marry their father and kill their mother (the Electra complex). However, girls do not fear castration; rather they experience penis envy (desire to have a penis). The resolution of the Oedipus or Electra complex is identification with the same-sex parent.

Cognitive Development

One of the tasks related to the preschool period is readiness for school and scholastic learning. Many of the thought processes of this period are crucial for achieving such readiness, and it is intentional that the child begins school between ages 5 and 6 rather than earlier.

Preoperational Phase (Piaget)

Piaget’s cognitive theory does not include a period specifically for children 3 to 5 years old. The preoperational phase covers the age span from 2 to 7 years and is divided into two stages: the preconceptual phase, ages 2 to 4, and the phase of intuitive thought, ages 4 to 7. One of the main transitions during these two phases is the shift from totally egocentric thought to social awareness and the ability to consider other viewpoints (Fig. 15-3). Egocentricity, however, is still evident. Children are able to think and verbalize their mental processes without having to act out their thinking. They can think of only one idea at a time and are unable to think of all parts in terms of the whole.

Language continues to develop during the preschool period. Speech remains primarily a vehicle of egocentric communication. Preschoolers assume that everyone thinks as they do and that a brief explanation of their thinking makes them understood by others. Because of this self-referenced, egocentric verbal communication, it is often necessary to explore and understand young children’s thinking through other, nonverbal approaches. For children in this age-group, the most enlightening and effective method is play, which becomes the child’s way of understanding, adjusting to, and working out life’s experiences. Because of a child’s rich imagination and unlimited ability to invent and imitate, all types of play hold therapeutic and communicative value.

Preschoolers increasingly use language without comprehending the meaning of words, particularly concepts of right and left, causality, and time. Children may use the concepts correctly but only in the circumstances in which they have learned them. For example, they may know how to put on shoes by remembering that the buckle is always on the outside of the foot. However, if different shoes have no buckles, they cannot reason which shoe fits which foot. They do not understand the concept of right and left.

Superficially, causality resembles logical thought. Preschoolers explain a concept as they have heard it described by others, but their understanding is limited. For example, since preschoolers do not completely understand time, they interpret it according to their own frame of reference, such as “A long time means until Christmas.” Consequently, time is best explained in relation to an event, such as “Your mother will visit you after you finish your lunch.” Avoiding words such as “yesterday,” “tomorrow,” “next week,” or “Tuesday” to express when an event is expected to occur and associating time with usual expected daily occurrences help children learn about temporal relationships while increasing their trust in others’ predictions.

Preschoolers’ thinking is often described as magical thinking. Because of their egocentrism and transductive reasoning, they believe that thoughts are all powerful. Such thinking places them in the vulnerable position of feeling guilty and responsible for bad thoughts that may coincide with the occurrence of a wished event. A typical example is wishing a new sibling dead. If that sibling does die, young children think their wish caused the death. Their inability to reason the cause and effect of illness or injury makes it especially difficult for them to understand such events.

Preschoolers believe in the power of words and accept their meaning literally. A significant example of this type of thinking is calling children “bad” because they did something wrong. In their minds, telling children that they are bad means that they are bad. For this reason, it is better to relate such words to the act by saying, for example, “That was a bad thing to do.”

Moral Development (Kohlberg)

Moral development theory is based on cognitive development theory and consists of three major levels: preconventional, conventional, and postconventional (Kohlberg, 1968). Young children’s development of moral judgment is at the most basic level. They have little, if any, concern for why something is wrong. They behave because of the freedoms or restrictions placed on actions. In the punishment and obedience orientation, children (approximately ages 2 to 4 years) judge whether an action is good or bad according to whether it results in reward or punishment. If children are punished for it, the action is bad. If they are not punished, the action is good, regardless of its meaning. For example, if parents allow hitting, the child will perceive that hitting is good because it is not associated with punishment.

From approximately 4 to 7 years of age, children are in the stage of naive instrumental orientation, in which actions are directed toward satisfying their needs and, less commonly, the needs of others. They have a concrete sense of justice and fairness during this period of development.

Spiritual Development

Children learn about faith and religion from significant others in their environment, usually from parents and their religious beliefs and practices. However, cognitive level influences young children’s understanding of spirituality. Preschoolers have a concrete conception of a God with physical characteristics, often like an imaginary friend. They understand simple stories and memorize short prayers, but have limited understanding of the meaning of these rituals. They benefit from concrete representations of religious practices, such as picture books and small statues.

Development of the conscience is strongly linked to spiritual development. At this age, children are learning right from wrong and behave correctly to avoid punishment. Wrongdoing provokes guilt, and preschoolers often misinterpret illness as punishment for real or imagined transgressions. It is important that children view God as one who bestows unconditional love, rather than as a judge of good or bad behavior. Observing religious traditions and participating in a religious community often help children and their families cope during stressful periods, such as illness and hospitalization (Speraw, 2006).

Development of Body Image

The preschool years play a significant role in the development of body image. With increasing comprehension of language, preschoolers recognize that individuals have undesirable and desirable appearances. They recognize differences in skin color and racial identity and are vulnerable to learning prejudices and biases. They are aware of the meaning of words such as “pretty” or “ugly,” and they reflect the opinions of others regarding their own appearance. By 5 years of age, children compare their size with that of their peers and can become conscious of being large or short, especially if others refer to them as “so big” or “so little” for their age. Research indicates that negative associations between weight status and self-concept are present in girls as young as 5 years of age, and weight status can affect the psychologic well-being of both males and females (Wardle and Cooke, 2005).

Despite the advances in body image development, preschoolers have poorly defined body boundaries and little knowledge of their internal anatomy. Intrusive experiences are frightening, especially those that disrupt the integrity of the skin (e.g., injections and surgery). They fear that all their blood and “insides” can leak out if the skin is “broken.” Therefore preschoolers may believe it is critical to use bandages after an injury.

Development of Sexuality

Sexual development during the preschool years is important to a person’s overall sexual identity and beliefs. Preschoolers form strong attachments to the opposite-sex parent while identifying with the same-sex parent. Sex typing, or the process by which an individual develops the behavior, personality, attitudes, and beliefs appropriate for his or her culture and sex, occurs through several mechanisms during this period. Probably the most powerful mechanisms are childrearing practices and imitation. The ways in which parents dress, hold, cuddle, caress, discipline, and talk to their child express some aspect of sexually oriented behavior. Gender identification is a result of complex prenatal and postnatal psychologic factors, as well as biologic, social, and genetic influences. It is believed that most children are aware of their sex and the expected set of related behaviors by  to

to  years of age. Although toddlers might be aware of their particular sex, they do not possess the language and cognitive skills to investigate sexual identity as fully as preschoolers.

years of age. Although toddlers might be aware of their particular sex, they do not possess the language and cognitive skills to investigate sexual identity as fully as preschoolers.

As sexual identity develops beyond gender recognition, modesty and fears of mutilation may become a concern. Sex-role imitation and “dressing up” like Mommy or Daddy are important activities. Attitudes and responses of others to role-playing can condition the child to adopt particular views of self or others. For example, comments such as “Boys shouldn’t play with dolls” can influence a boy’s masculine self-concept.

Sexual exploration may be more pronounced now, particularly in terms of exploring and manipulating the genitalia. Preschoolers’ may have questions about sexual reproduction as they search for understanding. (See Sex Education, p. 596, and also Chapters 17 and 19.)

Social Development

During the preschool period, the separation-individuation process is completed. Preschoolers have overcome much of their anxiety associated with strangers and the fear of separation of earlier years. They relate to unfamiliar people easily and tolerate brief separations from parents with little or no protest. However, they still need parental security, reassurance, guidance, and approval, especially when entering preschool or elementary school. Prolonged separation, such as that imposed by illness and hospitalization, is difficult; however, preschoolers respond well to anticipatory preparation and concrete explanation. They can cope with changes in daily routine much better than toddlers but may develop more imaginary fears. They gain security and comfort from familiar objects such as toys, dolls, or photographs of family members. They are able to work through many of their unresolved fears, fantasies, and anxieties through play, especially if guided with appropriate play objects (e.g., dolls or puppets) that represent family members, health professionals, and other children.

Language

Language becomes more sophisticated and complex during the preschool years. Both cognitive ability and environment, particularly consistent role models, influence vocabulary, speech, and comprehension. Language becomes a major mode of communication and social interaction. Vocabulary increases dramatically, from 300 words at age 2 to more than 2100 words at the end of 5 years. Sentence structure, grammatical usage, and intelligibility also advance to a more adult level. Preschool children may even become bilingual (see Cultural Competence box).

Children between the ages of 3 and 4 years form sentences of approximately three or four words and include only the words most essential to convey meaning. Such speech is often termed telegraphic because of its brevity. Three-year-old children ask many questions and use plurals, correct pronouns, and the past tense of verbs. They name familiar objects (such as animals and parts of the body), relatives, and friends. They can give and follow simple commands. They talk incessantly, regardless of whether anyone is listening to or answering them. They enjoy musical or talking toys or dolls and imitate new words proficiently.

From ages 4 to 5 years, preschoolers use longer sentences of four or five words and use more words to convey a message, such as prepositions, adjectives, and a variety of verbs. They follow simple directional commands, such as “Put the ball on the chair,” but can carry out only one request at a time. They answer questions such as “What do you do when you are hungry?” by describing the appropriate action. The pattern of asking questions is at its peak, and children usually repeat the question until they receive an answer.

By age 6, children can use all parts of speech correctly, except for deviations from the rule. They can define simple objects and actions by describing their use, shape, or general category of classification, rather than simply describing their outward appearance. For example, they can define a ball as “round, something you bounce, or a toy,” rather than only describing its color. They can give some opposites, such as “If Mommy is a woman, Daddy is a man.” They can also describe an object according to its composition, such as “A spoon is made of metal.”

Personal-Social Behavior

The pervasive ritualism and negativism of toddlerhood gradually diminish during the preschool years. Although self-assertion is still a major theme, preschoolers demonstrate their sense of autonomy differently. They are able to verbalize their request for independence and perform independently because of their much-refined physical and cognitive development. By 4 or 5 years of age, they need little if any assistance with dressing, eating, or toileting (Fig. 15-4). They can also be trusted to obey warnings of danger, although 3- or 4-year-old children may exceed their boundaries at times.

Fig. 15-4 Most preschoolers are able to dress themselves but need help with more difficult items of clothing.

Preschoolers are much more sociable and willing to please than toddlers. They have internalized many of the standards and values of the family and culture. However, by the end of early childhood they begin to question parental values and compare them with those of their peer group and other authority figures. As a result, they may be less willing to abide by the family’s code of conduct. Preschoolers become increasingly aware of their position and role within the family. Although this is a more secure age for experiencing the addition of another sibling, relinquishing the position of first or youngest is still difficult and requires appropriate preparation. (See Sibling Rivalry, Chapter 14.)

Play

Various types of play are typical of this period, but preschoolers especially enjoy associative play, group play in similar or identical activities but without rigid organization or rules. Play should provide for physical, social, and mental development (see Table 15-1).

Play activities for physical growth and the refinement of motor skills include jumping, running, and climbing. Tricycles, wagons, gym and sports equipment, sandboxes, wading pools, and winter sleds can help develop muscles and coordination. Activities such as swimming, skating, and skiing teach safety and can also help develop muscles and coordination.

Manipulative, constructive, creative, and educational toys provide for quiet activities, fine motor development, and self-expression. Easy construction sets, large blocks of various sizes and shapes, a counting frame, alphabet or number flash cards, paints, crayons, simple carpentry tools, musical toys, illustrated books, simple sewing or handicraft sets, large puzzles, and clay are suitable toys (Fig. 15-5). Electronic games and computer programs are especially valuable in helping children learn basic skills, such as letters and simple words. Although their attention span is still short, preschoolers are beginning to enjoy crafts, especially with the guidance and assistance of adults. A helpful rule in planning creative activities is one simple project per year of age. For example, a 3-year-old child usually has the patience to decorate three eggs but will become bored and restless with more.

![]() Probably the most characteristic and pervasive preschooler activity is imitative, imaginative, and dramatic play. Dress-up clothes, dolls, housekeeping toys, dollhouses, telephones, farm animals and equipment, village sets, trains, trucks, cars, planes, hand puppets, and medical kits provide hours of self-expression (Fig. 15-6). Probably more than any other age-group, 4- and 5-year-old children are absorbed in the reproduction of the behavior of significant adults. Toward the end of the preschool period, children are less satisfied with make-believe or pretend objects and enjoy actually doing the activity, such as cooking and carpentry.

Probably the most characteristic and pervasive preschooler activity is imitative, imaginative, and dramatic play. Dress-up clothes, dolls, housekeeping toys, dollhouses, telephones, farm animals and equipment, village sets, trains, trucks, cars, planes, hand puppets, and medical kits provide hours of self-expression (Fig. 15-6). Probably more than any other age-group, 4- and 5-year-old children are absorbed in the reproduction of the behavior of significant adults. Toward the end of the preschool period, children are less satisfied with make-believe or pretend objects and enjoy actually doing the activity, such as cooking and carpentry.

![]() Critical Thinking Exercise—Imitative Play

Critical Thinking Exercise—Imitative Play

Television and DVDs also have their place in children’s play, although each should be only one part of their total repertoire of social and recreational activities. Parents and other caregivers should supervise the selection of programs, watch and discuss programs with their children, schedule limited hours for television viewing, and set a good example of television viewing (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2007). Children enjoy and learn from educational programs; however, television viewing may limit time spent in other meaningful activities such as reading, physical activity, and socialization (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2007). Television can become an interactive activity when adults view programs with children and discuss program content.

Play is so much a part of the young child’s life that reality and fantasy become blurred. The make-believe is reality during play and becomes fantasy only when toys are put away or dress-up clothes are removed. It is no wonder that imaginary playmates are so much a part of this age period. Imaginary companions usually appear between the ages of  and 3 years and, for the most part, last until the child enters school. Preschool girls have a higher incidence of creating imaginary companions, whereas preschool boys tend to impersonate characters (Carlson and Taylor, 2005). Imaginary companions serve many purposes; they become friends in times of loneliness, they accomplish what the child is still attempting, and they experience what the child wants to forget or remember. It is not unusual for the “friend” to have myriad vices and be blamed for wrongdoing. Sometimes the child hopes to escape punishment by saying, “My friend Brian broke the glass.” At other times the preschooler may fantasize that the “companion” misbehaved and play the role of parent. This becomes a way of assuming control and authority in a safe situation.

and 3 years and, for the most part, last until the child enters school. Preschool girls have a higher incidence of creating imaginary companions, whereas preschool boys tend to impersonate characters (Carlson and Taylor, 2005). Imaginary companions serve many purposes; they become friends in times of loneliness, they accomplish what the child is still attempting, and they experience what the child wants to forget or remember. It is not unusual for the “friend” to have myriad vices and be blamed for wrongdoing. Sometimes the child hopes to escape punishment by saying, “My friend Brian broke the glass.” At other times the preschooler may fantasize that the “companion” misbehaved and play the role of parent. This becomes a way of assuming control and authority in a safe situation.

Parents often worry about their child having imaginary playmates, not realizing how normal and useful they are. Parents should be reassured that the child’s fantasy is a sign of health that helps differentiate between make-believe and reality. Parents can acknowledge the presence of the imaginary companion by calling him or her by name and even agreeing to simple requests such as setting an extra place at the table, but they should not allow the child to use the playmate to avoid punishment or responsibility. For example, if the child blames the companion for messing up a room, the parents need to state clearly that the child is the only person they see, and therefore the child is responsible for cleaning up (see Critical Thinking Exercise).

Children also benefit from play that occurs between them and a parent. Mutual play fosters development from birth through the school years and provides enriched opportunities for learning. Through mutual play, parents can provide tactile and kinesthetic experiences, can maximize verbal and language abilities, and can offer praise and encouragement for exploration of the world. Additionally, mutual play encourages positive interactions between the parent and child, strengthening their relationship. Recommendations for mutual play should reflect the child’s developmental level and can incorporate readily available items found in the home or community (musical CDs, puppets, games, and puzzles).

Temperament

Temperament influences children’s social development and interactions. Chapters 12 and 14 discuss the importance of temperament during early childhood. Because temperamental characteristics tend to remain stable, the same considerations in terms of childrearing apply during the preschool years.

One major concern in the preschool age-group is the effect of temperament on adjustment in group situations, especially school, and the long-term consequences of temperamental characteristics. In particular, the degree of adaptability to new situations, intensity of response, distractibility, amount of persistence, mood, and activity level may influence a child’s chances for success in school. Consequently, parents can benefit from suggestions that can promote preschoolers’ adjustment. For example, children who are slow to warm up need gradual introduction to new situations and may benefit from the parent’s presence until they have settled in. Children with high activity levels tend to adjust better to environments that allow freedom of movement, rather than a structured or regimented classroom. The more aware parents are of their children’s unique behaviors, the better they are able to inform teachers or other caregivers of the children’s needs and successful approaches to handling the youngsters.

The Behavioral Style Questionnaire helps identify temperamental characteristics in children from 3 to 7 years old (McDevitt and Carey, 1978). Simply asking parents to rate their child as being much easier than, easier than, as easy as, more difficult than, or much more difficult than the average child may also be a valuable screening method.

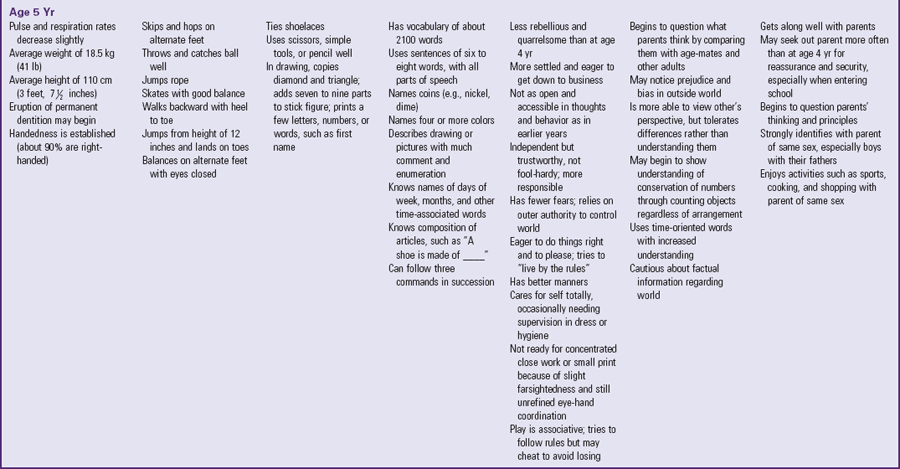

Table 15-1 summarizes the major developmental achievements for children 3, 4, and 5 years old.

Coping with Concerns Related to Normal Growth and Development

Preschool and Kindergarten Experience

Some children are home-schooled, but many children attend some type of early childhood program, usually preschool or a daycare center. Group care has become commonplace with the large number of parents currently employed outside the home. The effects of early education and stimulation on children have increasingly gained recognition. Because social development widens to include age-mates and other significant adults, preschool provides an excellent vehicle for expanding children’s experiences with others. It is also excellent preparation for entrance into elementary school.

In preschool or daycare centers, children have opportunities to learn about group cooperation; adjustment to sociocultural differences; and coping with frustration, dissatisfaction, and anger. In preschool centers, activities often provide for mastery and achievement, which makes children increasingly feel success, self-confidence, and personal competence. Whether structured learning is imposed is less important than the social climate, type of guidance, and attitude toward the children that is fostered by the teacher or leader. With a teacher who is aware of preschoolers’ developmental abilities and needs, children will learn from the activity provided. Most programs incorporate a daily schedule of quiet play, outdoor activity, group activities such as games and projects, creative or free play, and snack and rest periods.

Preschool is particularly beneficial for children who lack a peer-group experience, such as an only child, and for children from impoverished homes. It provides extensive stimulation for language, physical, and social development. It is also excellent preparation for kindergarten. For a child from an underprivileged home, elementary school can be so overwhelming that the sensory overload impedes all learning. Regular school places many more demands on children for prolonged attention, self-disciplined behavior, and demonstrated progress in performance and achievement than does the less-structured atmosphere of preschool.

One of the issues that parents face is the child’s readiness for preschool or kindergarten. School readiness is influenced by myriad elements, including a child’s social, emotional, and physical development; health status; ability and desire to learn; life experiences; family environment; and parental support. There are no absolute indicators for school readiness. The child’s social maturation, especially attention span, is as important as academic readiness.

The use of developmental screening tools and readiness testing varies by state and local district. Developmental screening differs from readiness testing, and there is controversy over the most beneficial form of evaluation in determining a child’s readiness to enter school. Readiness testing focuses on evaluation of skill acquisition, whereas developmental screening focuses on the potential to learn. Developmental screening tools address cognitive (especially language), social, and physical milestones and can identify children who may benefit from further diagnostic testing.

Schools and parents play integral roles in a child’s school readiness. Schools must be able to assist children with varying learning and physical abilities and should be able to provide diverse learning situations that serve as a foundation for continued growth and maturation. Parents should promote a positive attitude toward learning, read to their children, encourage their children to participate in a variety of activities to explore their talents and interests, and choose appropriate child care or preschool programs (Hagan, Shaw, and Duncan, 2008).

Nurses can help parents assess children’s readiness in terms of age, physical ability, and cognitive and social development (see Table 15-1). For example, a group experience may be difficult for young children with short attention spans. These children may require a different type of experience with more individualized attention.

Health care providers can also be helpful in guiding parents in selecting enriched social and educational early intervention programs, schools, and childcare centers. Careful selection of early childhood education is fundamental to future learning and development. Licensed and regulated programs must follow established standards, which represent minimum requirements and safeguards. Regulation is important to protect children from harm and to promote the conditions essential for a child’s healthy development and learning. The National Association for the Education of Young Children supports early childhood regulation on all levels.*

Other areas to evaluate are the facility’s daily program, teacher qualifications, staff/student ratio, discipline policy, environmental safety precautions, provision of meals, sanitary conditions, amount of indoor and outdoor space per child, and fee schedule. References from other parents help to evaluate a facility, but personal observation of the facility is recommended. Encourage parents to meet the director and some of the employees at a few facilities to make an informed choice.

Evaluation of the facility’s health practices is extremely important. Children in daycare centers have more illnesses than children not in daycare centers, especially gastrointestinal tract infections; respiratory tract infections; and hepatitis A, varicella-zoster virus, and cytomegalovirus infections (Nesti and Goldbaum, 2007). Health care providers can advise parents regarding the evaluation of a facility’s sanitary practices and can actively participate in educating staff in measures to minimize infection.

Preparing the Child: Children need preparation for the preschool or kindergarten experience.* For young children, these programs represent a change from their usual home environment and prolonged separation from their parents. Even if children have been cared for by a baby-sitter or in a group setting, preschool and kindergarten differ because there is less individualized attention, programs are more structured, and learning is usually expected.

Before children begin school, parents should present the idea as exciting and pleasurable. Talking to them about activities such as painting, building with blocks, or enjoying swings and other outdoor equipment allows children to fantasize about the forthcoming event in a positive manner. When the first day of school arrives, parents should behave confidently. Such behavior requires parents to have resolved their own feelings regarding the experience.

Parents should introduce their child to the teacher and the facility. In some instances, it is helpful for parents to remain for at least part of the first day until the child is comfortable. If parents stay, they should be available to the child but inconspicuous. A full-day routine is often too overwhelming for a child and could be shortened to a morning or afternoon session if possible. To decrease separation anxiety, parents can provide the school with detailed information about the child’s home environment, such as familiar routines, favorite activities, food preferences, names of siblings or pets, and personal habits. Such information helps the child feel at ease in the strange surroundings. A school that automatically requests this information demonstrates the staff’s awareness of each child’s needs, and the parent has a valuable clue to evaluating the quality of the program. Transitional objects, such as a favorite toy, may also help the child bridge the gap from home to school.

Sex Education

Preschoolers have assimilated a tremendous amount of information during their short lifetimes. Although their thinking may not be mature, they search constantly for explanations and reasons that are logical and reasonable to them. The word “why” seems to supplant the word “no,” which was common in toddlerhood. It is only natural that as they learn about “me,” they will also want to know “why me,” and “how me.” Questions such as “Where do babies come from?” are as casual as “Why is the sky blue?” “What makes it rain?” or “Who is that?” It is the way in which adults answer questions about procreation that conditions children, even the youngest, to separate these questions from others about their world. If adults answer these questions honestly and as matter-of-factly as any other inquiry, children will continue to search for answers. If they are answered with a “tall tale” or an anxious “You are too young to know about that,” children will learn to keep such questions to themselves. Unfortunately, as they harbor these silent mysteries, they formulate their own theories to explain birth. Because magical thinking need not be based on logic or fact, any fantastic and often terrifying explanation can substitute for the truth.

Two rules govern answering sensitive questions about topics such as sex. The first is to find out what children know and think. By investigating the theories children have produced as a reasonable explanation, parents can not only give correct information but also help children understand why their explanation is inaccurate. Another reason for ascertaining what the child thinks before offering any information is to avoid giving an “unasked for” answer. For example, 4-year-old Lauren asked her father, “Where did I come from?” Both parents quickly took this inquiry as a clue for offering sex education. After the explanation, Lauren exclaimed, “I don’t know about all that! All I know is Mary came from New York, and I want to know where I was born.”

The second rule for giving information is to be honest. True, the preschooler will forget or misunderstand much of the correct information, but the correct information can be restated until the child absorbs and comprehends the facts. Even though the correct anatomic words may be hard to pronounce or difficult to remember, they become important for explaining other concepts later on. Nurses have the opportunity to contribute to early sex education by conveying accurate information regarding genital terms during physical examinations.

Honesty does not imply imparting every fact of life or allowing excessive permissiveness in sexual curiosity. A child who asks one question is looking for one answer. When they are ready, children will ask about the other “unfinished” parts of the story. Sooner or later they will wonder how the “sperm meets the egg” and “how the baby gets out,” but it is best to wait until they ask.

If parents offer too much information, the child will simply become bored or end the conversation with an irrelevant question. Parents worry a great deal about whether they can “harm” their children with “too much” information or tell them things they will not understand. In general, knowledge is not harmful when delivered in a developmentally appropriate manner. It is likely that children may not comprehend everything parents explain initially; they will process information at their own pace. What matters is that parents are approachable and do not dismiss their child’s inquiries. It is also important for parents to recognize that children’s sex education is affected not only by the information they receive verbally but also by the relationship and sexual behavior they see their parents modeling and by the sexual content they are exposed to in their everyday environment (e.g., television, magazines, movies).

When a child does not ask questions, parents and health professionals should take advantage of natural opportunities to discuss reproduction, such as talking about someone who is pregnant or discussing a television program or movie about biologic aspects. Many excellent books on sex education are available for preschool children at public libraries, and the Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States,* local chapters of Planned Parenthood Federation of America,† and the American Academy of Pediatrics‡ have bibliographies of suggested reading material. Parents should read the book before giving or reading it to a child.

Regardless of whether children are given sex education, they will engage in games of sexual curiosity and exploration. At approximately 3 years of age, children are aware of the anatomic differences between the sexes and are concerned with how the other “works.” This is not really “sexual” curiosity because many children are still unaware of the reproductive function of the genitalia. They are curious about the eliminative function of the anatomy. Little boys wonder how girls can urinate without a penis, so they watch girls go to the bathroom. Because they cannot see anything but the stream of urine coming out, they want to observe further. “Doctor play” is often a game invented for just such investigation. Little girls are no less curious about boys’ anatomy. They find it intriguing to inspect this “thing” that girls do not have.

Parents often wonder how to handle such sexual curiosity. A positive approach is to neither condone nor condemn the behavior but to tell the children that, if they have questions, they should ask the parents; the parents should then encourage the children to engage in some other activity. In this way, children understand that they can satisfy their sexual curiosity in ways other than playing investigative games. This in no way condemns the act but stresses alternative methods by which to seek solutions and answers. Allowing children unrestricted permissiveness only intensifies their anxiety and concern, since exploring and searching usually yield little evidence to satisfy their curiosity.

Occasionally, parents are faced with special dilemmas (e.g., when a child accidentally witnesses sexual intercourse). When such an event occurs, parents must remember that sex education is much more than textbook facts. It is part of a broader concept called sexuality; two people unite intimately because of the special relationship they have together. Intercourse is not a physical act apart from feeling or emotion but a private act that two people share to express caring and for pleasure. Offering such an explanation teaches appropriate social behavior and, in particular, stresses the meaningful, intimate relationship between two adults. When children witness sexual acts, parents should use the opportunity immediately to communicate that sex is part of a healthy and natural adult relationship. However, to prevent subsequent interruptions, children are cautioned to always knock first; if they are too young to understand or comply, a lock on the door is appropriate.

Another concern for some parents is masturbation, or self-stimulation of the genitalia. This occurs at any age for a variety of reasons and, if not excessive, is normal and healthy. For preschoolers, it is part of sexual curiosity and exploration. An important feature of normal childhood masturbation is that the child stops masturbating when distracted (Mallants and Casteels, 2008). If parents are concerned about their child masturbating, it is essential for nurses to investigate the circumstances associated with the activity. Masturbation can be associated with a genitourinary condition, or it may be an expression of anxiety, anger, or boredom; however, in the case of excessive sexual behavior, it may be associated with sexual abuse and emotional or behavioral problems (Mallants and Casteels, 2008). Management of normal childhood masturbation includes parent education and reassurance; redirection of the child to other activities, if masturbation is taking place openly and publicly; and avoidance of punishment, which may reinforce the behavior (Yang, Fullwood, Goldstein, et al, 2005). In addition, parents should emphasize that masturbation is a private act, thus teaching children socially acceptable behavior.

Gifted Children

The importance of identifying gifted children and their needs is increasingly being recognized. Although the definition of gifted varies, giftedness is traditionally defined as a minimum intelligence quotient (IQ) of 130 (Lovett and Lewandowski, 2006). A broader view, reflected in the term gifted-talented, considers signs of giftedness to include specific academic aptitudes, advanced memory skills, creative thinking, ability in the visual or performing arts, and psychomotor ability, either individually or in combination. Children may be identified as gifted when they enter school or are referred by parents or teachers and receive IQ tests. However, parents and caregivers should be aware that giftedness may be present in both academic and nonacademic areas. Therefore not all gifted children are identified when IQ tests alone are used to determine giftedness, which may result in the tragic loss of the opportunity to develop a child’s full potential (Lovett and Lewandowski, 2006). It is also important to recognize that giftedness can exist in children who have learning disabilities (Lovett and Lewandowski, 2006) or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (Antshel, Faraone, Stallone, et al, 2007). Nurses who are aware of the behavioral and developmental characteristics of giftedness can assess children’s mental and physical capabilities and assist in early identification (Box 15-1).

Gifted children can present unique challenges to parents. They often demand increased stimulation as infants and continue to seek a great deal of attention from their parents. Their high energy level and persistence can lead to discipline problems similar to those seen in children with difficult temperaments. Parents may be intimidated by having a child smarter than themselves and be hesitant to set limits. However, gifted children are children first and have the same needs for love, security, and consistent boundaries as other youngsters.

Sometimes children’s advanced skills in one area cause adults to exaggerate their abilities in all areas and thus expect excessively mature behavior. Parents may mislabel slower achievement in a particular skill as lack of trying, when really it represents children’s natural progression of abilities. These children benefit from academic settings that provide enrichment and accelerated learning commensurate with their capabilities. Consequently, early identification of gifted-talented children and appropriate parental guidance are critical to their optimum development and emotional adjustment (Liu, Lien, Kafka, et al, 2005).

Informational materials on parenting gifted and talented children is available from the National Association for Gifted Children,* the Council for Exceptional Children,† and local associations.

Aggression

The term aggression refers to behavior that attempts to hurt a person or destroy property. Aggression differs from anger, which is a temporary emotional state, but anger may be expressed through aggression. Hyperaggressive behavior in preschoolers is characterized by unprovoked physical attacks on other children and adults, destruction of others’ property, frequent intense temper tantrums, extreme impulsivity, disrespect, and noncompliance.

A complex set of biologic, sociocultural, and familial variables influence aggression. Evidence indicates that gender differences exist and that boys exhibit more physical aggression than girls during preschool years (Bendersky, Bennett, and Lewis, 2006; Benzies, Keown, and Magill-Evans, 2009); however, preschool girls exhibit more relational aggression than preschool boys (Ostrov and Bishop, 2008). Sociocultural factors that are associated with childhood aggression include exposure to community violence and violence in the media (Reebye, 2005). Familial variables such as maternal depression, low level of maternal education, and low socioeconomic status contribute to childhood aggression (Miner and Clarke-Stewart, 2008). Negative parenting practices, including coercive parent-child interactions (McKee, Colletti, Rakow, et al, 2008), low levels of positive interactions and warmth (McKee, Colletti, Rakow, et al, 2008), physical abuse (Sheehan and Watson, 2008), and punitive interactions such as yelling and threatening (Sheehan and Watson, 2008), also contribute to childhood aggression. Other factors that tend to increase aggressive behavior are frustration, modeling, and reinforcement.

Frustration, or the continual thwarting of self-satisfaction by parental disapproval, humiliation, punishment, and insults, can lead children to act out against others as a means of release. These children displace their anger on others, particularly peers and other authority figures, especially if they fear their parents. This type of aggression often applies to the child who is well behaved at home but a discipline problem at school or a bully among playmates.

Modeling, or imitating the behavior of significant others, is a powerful influencing force in preschoolers. Children who see their parents as physically abusive are observing behavior that they come to know as acceptable and therefore may exhibit this behavior with others (Benzies, Keown, and Magill-Evans, 2009). Also, early harsh discipline may lead to aggressive behavior (Miner and Clarke-Stewart, 2008). Another aspect of modeling is establishing a double-standard for acceptable conduct. For example, in some families aggression is synonymous with masculinity, and boys are encouraged to defend themselves. Although defending one’s rights is to be encouraged for both sexes, at times the principle of “being tough” or “standing up for yourself” is not tempered with judgment, fairness, or equality but becomes an excuse for ruling and dominating others. Such permissive aggression can produce extreme anxiety in children because it makes them feel out of control, even though outwardly they may appear to be the “boss” or “bully.”

Another significant source for modeling is television. Numerous studies have found a positive correlation between viewing violent programs and developing aggression; therefore parents need encouragement to supervise programming, especially for children with aggressive tendencies (Brown and Hamilton-Giachritsis, 2005). The American Academy of Pediatrics (2007) offers a list of recommendations for healthy television viewing.

Reinforcement can also shape aggressive behavior and is closely associated with modeling “masculine” behavior. Sometimes the reward for aggressive behavior is negative (e.g., punishment or disapproval) yet reinforcing because it brings attention. For example, children who are ignored by their parents until they hit a sibling learn that this act attracts attention. Additionally, parents who permit aggressive behavior by not interfering communicate silent, implicit approval of such acts.

One of the tasks of preschoolers is learning socially acceptable behavior and the ability to control aggression and redirect their anger. Parents can help children by modeling the appropriate behavior and encouraging children to express themselves verbally. For example, rather than condoning the hitting of another child for taking a toy, parents can suggest that the child state how he or she feels, such as “I am angry when you take my ball. Please give it back.”

Children should not be made to feel guilty or ashamed for being angry or frustrated. When children recognize these feelings, they are better able to channel them into constructive, not destructive, outlets. One of the earliest demonstrations of aggression is temper tantrums. (See Chapter 14.) Parents can handle them constructively by not attending to or reinforcing them and by helping children find control through appropriate play situations. In this way, young children learn to acknowledge such feelings and express them in alternate ways, such as pounding on clay or hitting a punching bag. When children are out of control, they may need to be physically restrained or removed from the scene to prevent them from hurting themselves or others.

Sometimes the type of discipline used to extinguish other forms of unacceptable behavior actually promotes aggressive behavior. For example, if a child is spanked for an aggressive act, aggression is being used to “teach” a lesson against aggression. In addition to physically aggressive discipline, inconsistency in disciplinary practices may also foster aggressiveness in children (Ostrov and Bishop, 2008). The use of time-out and solitary play is an effective intervention for aggression. Additionally, minimizing anger and frustration can lead to fewer opportunities for acting-out behavior.

When a child exhibits extreme behaviors, such as aggression, parents are often concerned about the need for professional help. Generally, the difference between normal and problematic behavior is not the behavior itself but its quantity (number of occurrences), severity (interference with social or cognitive functioning), distribution (different manifestations), onset (when the behavior started), and duration (at least 4 weeks). When aggressive tendencies are evaluated, these factors are assessed to distinguish between behaviors typically seen at various ages and those that may represent an underlying problem. Extreme aggression requires professional treatment and is often difficult to change.*

Speech Problems

The most critical period for speech development occurs between 2 and 4 years of age. During this period, children are using their rapidly growing vocabulary faster than they can produce the words. A failure to master sensorimotor integration results in stuttering or stammering as children try to say the word they are already thinking about. This dysfluency in speech pattern is called developmental stuttering and is common during language development in children ages 2 to 5 years (Nelson, 2008). Stuttering affects boys more frequently than girls, has been shown to have a genetic link, and usually resolves during childhood (Prasse and Kikano, 2008). The National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (2008) encourages parents and caregivers of children who stutter to speak slowly and clearly, refrain from correcting or criticizing the child’s speech, resist completing the child’s sentences, and take time to listen attentively. When parents or other significant caregivers place undue emphasis on a child’s stuttering, they may exacerbate the problem. A speech evaluation is indicated if stuttering persists for longer than 6 months with no improvement (Hagan, Shaw, and Duncan, 2008).

The best therapy for speech problems is prevention and early detection. Common causes of speech problems are hearing loss, developmental delay, autism, and lack of verbal or psychosocial stimulation (Feldman, 2005). Referral for further evaluation and treatment may be necessary to prevent a problem from interfering with learning. Anticipatory preparation of parents for expected developmental norms may calm caregiver anxiety.

Children pressured into producing sounds ahead of their developmental level may develop dyslalia (articulation problems) or revert to using infantile speech. Prevention involves educating parents regarding the usual achievement of speech production during childhood. The Denver Articulation Screening Examination is an excellent tool for assessing articulation skills in the child and for explaining to parents the expected progression of sounds. (See Appendix A.)

Stress

Although for parents the preschool years generally are less troublesome than toddlerhood, this period presents children with many unique stresses. Some are innate and stem from preschoolers’ unique understanding of the world, such as fears. Others are imposed, such as beginning school. Although minimum amounts of stress are beneficial during the early years to help children develop effective coping skills, excessive stress is harmful. Young children are especially vulnerable because of their limited capacity to cope.

To help parents deal with stress in their child’s life, they must be aware of signs of stress and be helped to identify the source (Box 15-2). Any number of stresses may be present, such as the birth of a sibling, marital discord, relocation, or illness. The best approach to dealing with stress is prevention. It is important to monitor the amount of stress in the child’s life so that levels do not exceed ability to cope. In many instances, structuring the child’s schedule to allow rest and preparing the child for change, such as entering school, are sufficient measures.

Because stress is a constant aspect of daily living, it is not too early to help preschool children learn to cope with it. They can learn the meaning of the word stress and recognize physical signs of a stress reaction, such as a rapid pulse, a pounding heart, or fatigue. Teaching children relaxation and imagery is effective. Young children can learn to “let their bodies go limp like a rag doll.” Parents can use stories to help their child imagine pleasurable events. As language skills improve, encourage preschoolers to talk about their feelings and explore other ways of expressing emotions. Play is an excellent vehicle for venting anger or frustration, and toys such as drums, clay, and punching bags provide alternative methods of dissipating anxiety and teach socially acceptable ways of dealing with such feelings.

Fears

The greatest number and variety of real and imagined fears are present during the preschool years. Preschoolers may fear the dark, being left alone (especially at bedtime), animals (particularly large dogs and snakes), ghosts, sexual matters (castration), and objects or persons associated with pain. The exact cause of children’s fears is unknown. Freudians believe that the upsurge of fears during the preschool years results from the anxiety of being injured and mutilated (castration complex). Piaget views fears as a product of the type of thinking in this age-group; preschoolers are caught between the egocentric thinking of infants, which protects them from imagined fears, and the more logical thought processes of school-age children, which help explain and dispel potential fears. Children in the preconceptual stage still engage in egocentric thought but are now able to imagine an event without actually experiencing it. For example, seeing someone hurt is sufficient for realizing what the hurt must be like and for consequently fearing that hurt. This is commonly observed in medical practice. When watching another child get an injection, the preschooler may become upset, almost as if he or she received the injection.

The concept of animism (ascribing life-like qualities to inanimate objects) helps explain why children fear objects. For example, a child may refuse to use the toilet after watching a television commercial in which the toilet bowl is portrayed as turning into a monster.

One fear peculiar to this age is fear of annihilation. Because of poorly defined body boundaries and improved cognitive abilities, young children develop concerns related to loss of body parts, such as their body going down the drain. Because preschool children cannot understand concepts of size, they cannot understand that their body is too large to disappear down the drain.

Preschoolers are also likely to develop parent-induced fears. When parents demonstrate their fears, these concerns are communicated to the children. Such fears tend to be long lasting and difficult to dispel.

The best way to help children overcome their fears is by actively involving them in finding practical methods to deal with frightening experiences. This may be as simple as keeping a dim night-light in the child’s bedroom for reassurance or letting the child bathe a doll so that the child can observe that large objects cannot go down the drain. In this way, the experience that created the fear in the child can be reconstructed without involving the child directly as the victim. The child is allowed alternative methods by which to feel in control while overcoming fear.

Exposing children to the feared object in a safe situation provides a type of conditioning, or desensitization. For instance, children who are afraid of dogs should never be forced to approach or touch one, but they may be gradually introduced to the experience by watching other children play with the animal. This type of modeling, having others demonstrate fearlessness, can be effective if children are allowed to progress at their own rate.

Usually by 5 or 6 years of age, children relinquish many of their fears. Explaining the developmental sequence of fears and their gradual disappearance may help parents feel more secure in handling preschoolers’ fears. However, sometimes fears do not subside with simple measures or developmental maturation. When children experience severe fears that disrupt family life, professional help is required. Successful training programs may include (1) muscle relaxation; (2) guided imagery; (3) positive self-talk or recitation of brave statements; or (4) thought stopping, or repetition of reassuring statements that block fearful thoughts. Rewards or “tokens” may be given for “bravery” and not being afraid. Nurses can apply such interventions in clinical settings to reduce fears (e.g., of being alone or of painful procedures).

Promoting Optimum Health During the Preschool Years

Healthy nutrition during childhood should include eating a variety of foods and consuming sufficient energy to promote growth and development, while avoiding the development of obesity (Kleinman, 2009). For preschoolers, the requirement for calories per unit of body weight decreases slightly to 90 kcal/kg, for an average daily intake of 1800 calories. Fluid requirements may also decrease slightly (to approximately 100 ml/kg/day) but depend on activity level, climatic conditions, and state of health. Protein requirements increase with age; the recommended intake for preschoolers is 13 to 19 g/day (0.45 to 0.67 oz/day) (Otten, Hellwig, and Meyers, 2006). In children over 2 years of age, intake of dietary fiber should equal the child’s age plus 5 in grams per day (Kleinman, 2009).

The American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition recommends the following guidelines for children over the age of 2 years: saturated fatty acid consumption should be less than 10% of total caloric intake, total fat over several days should be 20% to 30% of total caloric intake, and cholesterol consumption should be less than 300 mg/day (Kleinman, 2009). Evidence supports the efficacy of following these recommendations, and negative health effects have not been reported (American Heart Association, Gidding, Dennison, et al, 2006). These efforts are important in the prevention of childhood obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome. While limiting fat consumption, it is also important to ensure the diet contains adequate nutrients. This can be done simultaneously as in the following example regarding calcium. The recommendation for daily calcium intake for children 1 to 3 years old is 500 mg, and the recommendation for children 4 to 8 years old is 800 mg (Otten, Hellwig, and Meyers, 2006). Milk and dairy products provide a major source of calcium. Eating less fat does not necessarily require drinking less milk or eating fewer dairy products but instead replacing higher fat milk, cheese, and yogurt with lower fat or nonfat choices.

Excessive consumption of fruit juices and other sweetened beverages has been associated with adverse health effects such as dental caries, gastrointestinal conditions such as chronic diarrhea, and diets poor in nutritive value (Allen and Myers, 2006). The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends limiting the intake of 100% fruit juice to 4 to 6 oz/day for children ages 1 to 6 years (American Heart Association, Gidding, Dennison, et al, 2006). Nurses should counsel moderation in fruit juice consumption and at the same time provide suggestions for more appropriate sources of nutrients such as ascorbic acid, folate, magnesium, and potassium.

In 2008 the US Department of Agriculture released a new food guide system called MyPyramid for Preschoolers, created specifically for children age 2 to 5 years (US Department of Agriculture, 2009). This new system is comprehensive and provides information for developing a healthy lifestyle at an early age. MyPyramid for Preschoolers includes customizable eating plans and offers information on growth during the preschool years, healthy eating habits, physical activity, and food safety. Parents can use this information to assist their children in making healthy lifestyle choices and to help prevent adverse health conditions secondary to poor nutrition.

Some preschoolers still have food habits typical of toddlers, such as food fads and strong taste preferences. When children reach 4 years of age, they seem to enter another period of finicky eating, which is generally characteristic of the more rebellious behavior of children in this age-group. By age 5 years, children are more agreeable to trying new foods, especially if encouraged by an adult who allows the child to help with food preparation or experiments with a new taste or different dish (Fig. 15-7). Mealtime can become a battle if parents expect excellent table manners. A 5-year-old child is usually ready for the “social” side of eating, but the younger child still has difficulty sitting quietly through a long family meal.

Fig. 15-7 Preschool children enjoy helping adults and are more likely to try new foods if they are included in the preparation.

The amount and variety of foods young children eat vary greatly from day to day. Consequently, parents sometimes worry about the quantity and quality of food consumed by preschoolers. In general, the quality is much more important than the quantity, which nurses should stress during nutritional counseling. There is some evidence that children self-regulate their caloric intake. If they eat less at one meal, they compensate at another meal or snack.

One approach toward lessening parental concern is advising parents to keep a weekly record of everything the child eats. In particular, stress the need to measure the amount of food, such as setting aside  cup of vegetables and serving the child from this premeasured amount, to provide a more accurate estimate of food intake at each meal. When parents look at the food chart at the end of the week, they are usually amazed at how much the child consumed. In general, preschoolers eat only slightly more than toddlers, or approximately half of an adult’s portion. Resources are available for the health care provider and the caregiver to help build healthy eating habits for children* (see Critical Thinking Exercise).

cup of vegetables and serving the child from this premeasured amount, to provide a more accurate estimate of food intake at each meal. When parents look at the food chart at the end of the week, they are usually amazed at how much the child consumed. In general, preschoolers eat only slightly more than toddlers, or approximately half of an adult’s portion. Resources are available for the health care provider and the caregiver to help build healthy eating habits for children* (see Critical Thinking Exercise).

Sleep and Activity

Sleep patterns vary widely, but the average preschooler sleeps approximately 12 hours a night and infrequently takes daytime naps. Waking during the night is common throughout early childhood and may be related to social rather than developmental factors (Moore, Meltzer, and Mindell, 2008).

Motor activity levels continue to be high and allow preschoolers to explore their environment, begin learning physical games and sports, and interact with others. Motor activity is therefore encouraged. Quiet activities, such as television and video games, are increasingly appealing and can become an unhealthy substitute for active play.

Preschoolers’ increased gross motor abilities and coordination allow them to engage in many physical activities, if only at a novice level. Whether young children should begin formalized training in an activity at this early age is controversial. Training programs must consider the child’s physical and psychologic immaturity, and readiness must be determined individually. The American Academy of Pediatrics (2006) encourages free play and a variety of physical activities. However, the Academy also supports organized play when it is developmentally appropriate and occurs in a nonthreatening, fun, and safe environment.

Sleep Problems

![]() The preschool years are a prime time for sleep disturbances. As toddlers and preschoolers cope with separation anxiety and increasing autonomy, they may begin to have more sleep problems (Jenni, Fuhrer, Iglowstein, et al, 2005; Moore, Meltzer, and Mindell, 2008). Some have trouble going to sleep, especially after so much activity and stimulation during the day. Others may develop bedtime fears, wake during the night, or have nightmares or sleep terrors. Still others may prolong the inevitable bedtime through elaborate rituals.

The preschool years are a prime time for sleep disturbances. As toddlers and preschoolers cope with separation anxiety and increasing autonomy, they may begin to have more sleep problems (Jenni, Fuhrer, Iglowstein, et al, 2005; Moore, Meltzer, and Mindell, 2008). Some have trouble going to sleep, especially after so much activity and stimulation during the day. Others may develop bedtime fears, wake during the night, or have nightmares or sleep terrors. Still others may prolong the inevitable bedtime through elaborate rituals.

Recommendations for handling a sleep disturbance are offered only after a thorough assessment. Cultural traditions may dictate sleep practices contrary to certain well-accepted professional recommendations. Therefore parents may not perceive particular sleep habits as problematic (see Cultural Competence box).

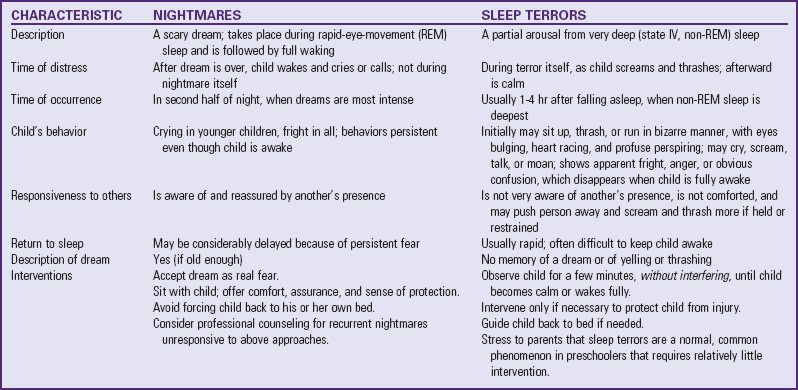

Interventions differ greatly; for example, nightmares and sleep terrors require different approaches (Table 15-2). For children who delay going to bed, a recommended approach involves counseling parents about the importance of a consistent bedtime ritual and emphasizing the normalcy of this type of behavior in young children. Parents should ignore attention-seeking behavior, and the child should not be taken into the parents’ bed or allowed to stay up past a reasonable hour. Other measures that may be helpful include keeping a light on in the room, providing transitional objects such as a favorite toy, or leaving a drink of water by the bed.

TABLE 15-2

COMPARISON OF NIGHTMARES TO SLEEP TERRORS

Modified from Ferber R: Solve your child’s sleep problems, New York, 1985, Simon & Schuster.

Helping children slow down before bedtime also reduces resistance to going to bed. One approach is to establish limited rituals that signal readiness for bed, such as a bath or story. Parents can reinforce the pattern by stating, “After this story, it is bedtime,” and consistently carrying through the routine. If anticipated extra stimulation (e.g., having visitors arrive at the children’s bedtime) disrupts this routine, it is advisable to settle children in bed beforehand.

Television viewing just before bedtime can also contribute to bedtime resistance and delay sleep onset. Research has revealed a direct correlation between extensive television viewing and sleep problems in children (Johnson, Cohen, Kasen, et al, 2004). Specific sleep problems related to television exposure include decreased sleep length, night wakings, impaired sleep quality, sleep onset problems, and sleep-wake transition disorders (Paavonen, Pennonen, Roine, et al, 2006). In addition to limiting the duration of television viewing, parents should ensure that television shows and other types of media are age appropriate and are not too frightening or overstimulating. Nurses should incorporate assessment of sleep patterns and education about the development of healthy sleep behaviors into every well-child visit.

Dental Health

By the beginning of the preschool period, the eruption of the deciduous (primary) teeth is complete. Dental care is essential to preserve these temporary teeth and to teach good dental habits. (See Chapter 14.) Although preschoolers’ fine motor control is improved, they still require assistance and supervision with brushing, and parents should perform flossing. Professional care and routine prophylaxis, especially fluoride supplements, should continue. The frequency of professional dental care should be based on a child’s individual risk assessment, including family history, socioeconomic status, dental development, presence or absence of dental disease, special health care needs, and dietary habits (Kagihara, Niederhauser, and Stark, 2009). Primary care providers are in an ideal situation to perform dental screenings and risk assessments and refer children to a dental home (Section on Pediatric Dentistry and Oral Health, 2008). The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry offers a Caries-Risk Assessment Tool for health care providers (www.aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/P_CariesRiskAssess.pdf), and the American Academy of Pediatrics provides a training program for pediatric health care professionals that presents information on dental screenings, risk assessments, and triage (www.aap.org/oralhealth/cme).