Health Promotion of the Adolescent and Family

Promoting Optimum Growth and Development

Promoting Optimum Health During Adolescence

Adolescents’ Perspectives on Health

Factors That Promote Adolescent Health and Well-Being

Health Concerns of Adolescence

Parenting and Family Adjustment

Intentional and Unintentional Injury

Dietary Habits, Eating Disorders, and Obesity

Sexual Behavior, Sexually Transmitted Infections, and Unintended Pregnancy

Use of Tobacco, Alcohol, and Other Substances

Physical, Sexual, and Emotional Abuse

Infectious Diseases and Immunizations

http://evolve.elsevier.com/wong/ncic

Adolescent Pregnancy, Ch. 20

Eating Problems and Disorders, Ch. 21

Health Problems of the Female Reproductive System, Ch. 20

Health Problems of the Male Reproductive System, Ch. 20

Health Problems Related to Sexuality, Ch. 20

Hyperlipidemia, Ch. 34

Immunizations, Ch. 12

Injury Prevention, Ch. 17

Obesity, Ch. 21

Precocious Puberty, Ch. 38

Problems Related to Sports Participation, Ch. 39

Sexually Transmitted Infections, Ch. 20

Substance Abuse, Ch. 21

Suicide, Ch. 21

Systemic Hypertension, Ch. 34

Promoting Optimum Growth and Development

Adolescence is a period of transition between childhood and adulthood, a time of profound biologic, intellectual, psychosocial, and economic change. During this period individuals reach physical and sexual maturity, develop more sophisticated reasoning abilities, and make educational and occupational decisions that will shape their adult careers. The changes of adolescence have important implications for understanding the kinds of health risks to which young people are exposed, the health-enhancing and risk-taking behaviors in which they engage, and the major opportunities for health promotion among this population.

In the process of examining widely accepted theories of adolescent development, researchers have challenged many popular notions. For example, a common belief is that teenagers’ behaviors are overwhelmingly determined by “raging hormones,” and that adolescence is a period when rebellious and risky behavior is the norm. Both notions are misguided, but these mistaken beliefs are not benign. They may have detrimental effects on attitudes and interactions with individual adolescents and on policy and program development. Although current research supports a more positive view of this life period, it also confirms that adolescence involves a complex interplay of biologic, cognitive, psychologic, and social change, perhaps more so than at any other time of life. Unfortunately, some perceive that the United States as a society often has provided little help to individuals as they try to cope with the normal changes of adolescence.

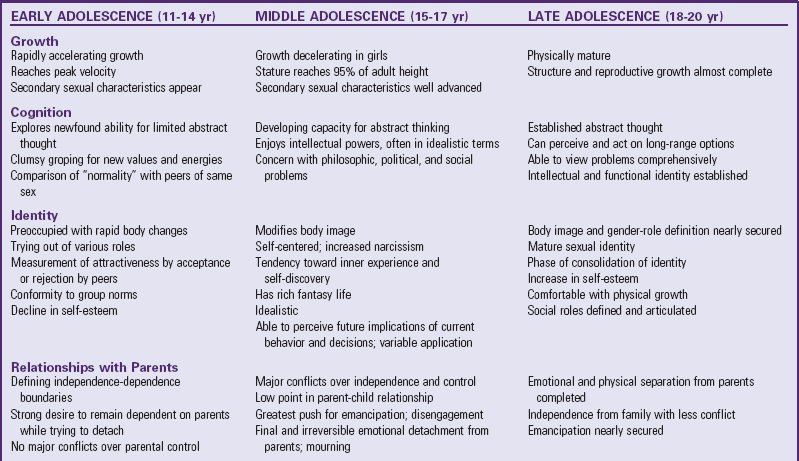

Change during adolescence occurs on multiple levels. On the individual level, changes include biologic maturation, cognitive development, and psychologic development. Change also occurs in the social contexts of adolescents’ families, peer groups, schools, and workplaces. Adolescence involves three distinct subphases: early adolescence (ages 11 to 14), middle adolescence (ages 15 to 17), and late adolescence (ages 18 to 20). The changes, opportunities, pressures, skills, and resources available to young people differ during these subphases. For example, early adolescence is characterized primarily by the changes of puberty and responses to those changes. Middle adolescence is characterized by transition to a dominant peer orientation, with all the stereotypic adolescent preoccupations of music, technology, dress and appearance, language, and behavior. Late adolescence involves transition into adulthood, including taking on adult work roles and developing adult relationships (Table 19-1).

Biologic Development

![]() Neuroendocrine Events of Puberty

Neuroendocrine Events of Puberty

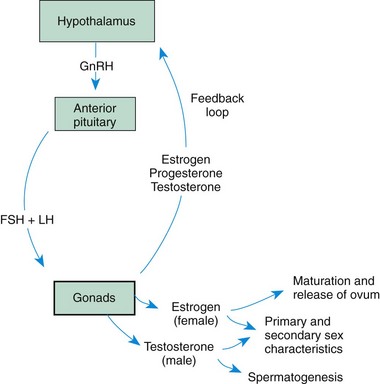

The fundamental biologic changes of adolescence are collectively referred to as puberty. Puberty involves a predictable sequence of hormonal and physical changes that occur universally over a defined period of time. It encompasses both sexual maturation and physical growth. It is generally accepted that the events of puberty are triggered by hormonal influences and are controlled by the anterior pituitary gland in response to a stimulus from the hypothalamus.

![]() Animation—Ovarian Growth in the Child

Animation—Ovarian Growth in the Child

Puberty begins as some not completely understood cluster of events triggers the production of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) by the hypothalamus (Fig. 19-1). GnRH travels through a network of capillaries to the anterior pituitary gland, where it stimulates the production and secretion of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH). Increasing levels of FSH and LH in the blood stimulate gonadal response. For females, FSH stimulates growth of ovarian follicles and production of estrogen. LH initiates ovulation, the formation of the corpus luteum, and progesterone production. For males, LH acts on testicular Leydig cells, prompting maturation of the testicles and testosterone production. FSH, acting with LH, stimulates sperm production. The sex steroids—estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone and other androgens—are released from the gonads and effect biologic changes in various organs, including muscles, bones, skin, and hair follicles. Increasing serum levels of sex steroids also provide feedback to the hypothalamus, causing decreases in GnRH secretion. When serum sex hormone levels decrease, the hypothalamus is stimulated to increase GnRH secretion, again initiating the sequence that produces the appropriate gonadal responses.

Fig. 19-1 Hormonal interaction between hypothalamus, pituitary, and gonads. GnRH, Gonadotropin-releasing hormone; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone.

Initiation of Puberty: The precise mechanism that institutes the changes at puberty is not completely understood. Although the pituitary gland and gonads are capable of mature function and can respond to stimuli at any age, the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal system is kept in a dormant state throughout childhood by some central nervous system inhibitory mechanism in the region of the hypothalamus. It is believed that the receptor sites in the hypothalamus are so highly sensitive that the most minute quantities of circulating sex hormones are sufficient to inhibit the secretion of GnRH during childhood. The hypothalamus loses this negative sensitivity at puberty, which allows the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal mechanism to attain full secretory function. As puberty progresses, the pituitary and gonads become increasingly sensitive to positive hormonal stimulation.

Changes in Reproductive Hormones

Females: The primary sexual characteristic in girls is the development and release of an egg, or ovum, from the ovaries approximately every 28 days. Beginning in early puberty, FSH stimulates estrogen production by the ovaries. However, concentrations of estrogen do not reach levels high enough to cause ovulation. By the time girls reach midpuberty, the body produces estrogen in larger amounts. This quantity of estrogen production results in the building of an endometrial lining of the uterus and first menstruation, or menarche. At menarche, ova still do not generally mature enough to be released. However, as puberty progresses, usually one ovarian follicle becomes dominant during each menstrual cycle and produces increasing amounts of estrogen during the early-cycle, follicular phase. This follicle then releases an ovum, a process termed ovulation, around day 14 of the menstrual cycle. After ovulation the follicle involutes and its estrogen production decreases. This leads to a drop in serum estrogen and progesterone. The pituitary gland responds to the drop in these hormone levels with increased production of FSH, initiating the start of a new menstrual cycle.

By direct action, estrogens cause growth and development of the vagina, uterus, and fallopian tubes. The skin of the labia majora, as well as that of the breast areola and nipples, grows and darkens under the influence of estrogen. Estrogen is responsible for breast enlargement. Estrogen also promotes the growth of pubic and axillary hair, and widening of the hips. At low levels estrogen tends to stimulate skeletal growth in both boys and girls, but at higher levels it inhibits growth.

Males: The primary male sexual characteristic is the development of viable sperm. During puberty, FSH acts on testicular cells, stimulating the production of viable sperm. FSH and LH also act on a different group of testicular cells, resulting in increased production and secretion of testosterone. In this process of sexual development, boys do not experience a discrete event analogous to menstruation or ovulation in girls. However, just as the production of a mature ovum tends to occur 1 year or more after menarche in girls, the production of viable sperm tends to follow boys’ first ejaculations. The capacity to ejaculate appears relatively early in boys’ sexual development, approximately 1 year after initial testicular enlargement and the appearance of pubic hair. From a clinical perspective, however, an adolescent should be considered potentially fertile with a first menstrual period or a first ejaculation.

Testosterone and other androgens have a direct impact on growth of the penis, scrotum, prostate, and seminal vesicles of the testicles. The tremendous growth-promoting properties of these hormones also result in rapid increases in muscle mass, skeletal growth, bone age, and bone density. In both sexes androgens are responsible for the development of pubic, axillary, facial, and body hair. Clinically, increased activity of androgens is associated with pubertal conditions such as acne, body odor, deepening of the voice, a spurt in height, and an increase in red blood cell levels.

Pubertal Sexual Maturation

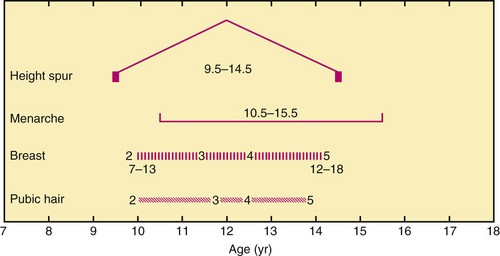

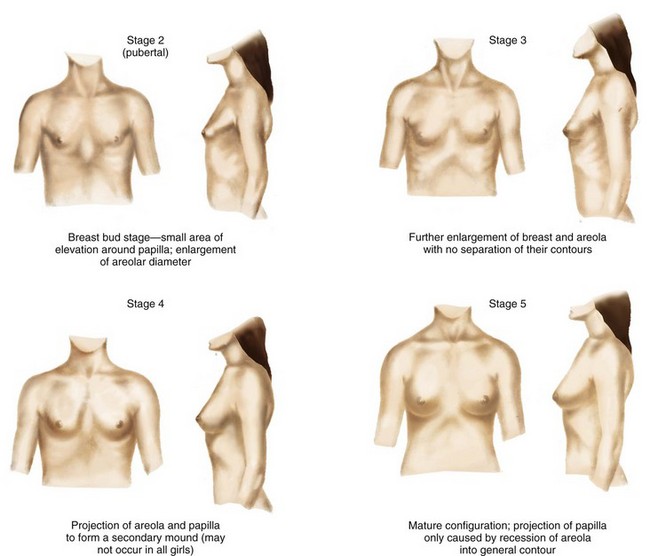

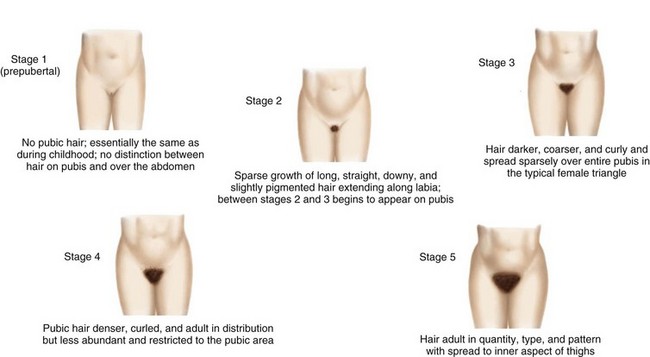

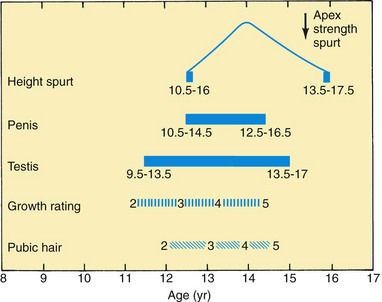

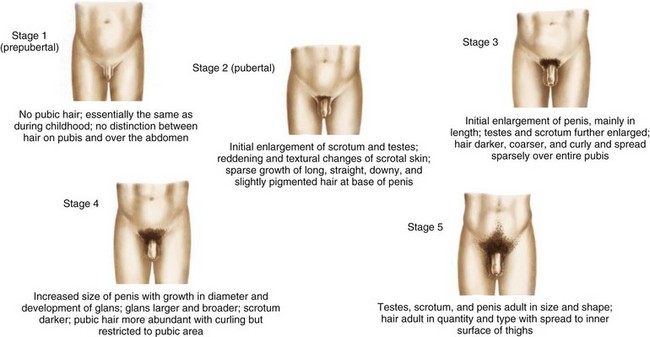

Increases in reproductive hormones are responsible for dramatic changes in secondary sexual characteristics that occur during puberty. As with general growth, development of secondary sexual characteristics occurs in a predictable sequence. This sequence has been divided into a series of five phases termed the Tanner stages (Box 19-1 and Figs. 19-2 to 19-6). Although the sequence of sexual development is predictable, the ages at which these changes occur and the rate of developmental progression vary considerably among individuals. Over the course of pubescence, many young people have questions about the timing, rate, and normalcy of their body changes. These concerns provide nurses with a prime opportunity to discuss health-related topics such as puberty, sexuality, birth control, prevention of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), nutrition, exercise, and safe methods of weight control.

Fig. 19-2 Approximate timing of developmental changes in girls. Numbers indicate stages of development. Range of ages during which some of the changes occur is indicated by inclusive numbers below them. See Figs. 19-3 and 19-4 for explanation. (Based on revised data from Herman-Giddens M, Slora EJ, Wasserman RC, et al: Secondary sexual characteristics and menses in young girls seen in office practice: a study from the Pediatric Research in Office Settings Network, Pediatrics 99(4):505-512, 1997.)

Fig. 19-3 Development of breasts in girls. Average age span is 6 to 13 years. Stage 1 (prepubertal—elevation of papilla only) is not shown. (Modified from Marshall WA, Tanner JM: Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls, Arch Dis Child 44(235):291-303, 1969; and Daniel WA, Paulshock BZ: A physician’s guide to sexual maturity, Patient Care 13:122-124, 1979.)

Fig. 19-4 Growth in pubic hair in girls. Average age span for stages 2 through 5 is 11 to 14 years. (Modified from Marshall WA, Tanner JM: Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls, Arch Dis Child 44(235):291-303, 1969; and Daniel WA, Paulshock BZ: A physician’s guide to sexual maturity, Patient Care 13:122-124, 1979.)

Fig. 19-5 Approximate timing of developmental changes in boys. Numbers indicate stages of development. Range of ages during which some of the changes occur is indicated by inclusive numbers below them. See Fig. 19-6 for explanation. (From Marshall WA, Tanner JM: Variations in the pattern of pubertal changes in boys, Arch Dis Child 45(239):13-23, 1970.)

Fig. 19-6 Developmental stages of secondary sexual characteristics and genital development in boys. Average age span is 12 to 16 years. (Modified from Marshall WA, Tanner JM: Variations in the pattern of pubertal changes in boys, Arch Dis Child 45(239):13-23, 1970; and Daniel WA, Paulshock BZ: A physician’s guide to sexual maturity, Patient Care 13:122-124, 1979.)

Sexual Maturation in Girls: In four out of five girls, changes in the nipple and areola and development of a small bud of breast tissue (thelarche) are the earliest, most easily visible changes of puberty. The average age of thelarche for Caucasian girls is 10 years, with a range of 8 to 12.75 years; for African-American girls, the average age of thelarche is earlier, around 9 years, with a range of 7 to 11 years (Herman-Giddens, Slora, Wasserman, et al, 1997; Herman-Giddens, 2006). The appearance of pubic hair (pubarche) usually follows initial breast development by about 2 to 6 months; however, in a minority of normally developing girls, pubic hair may precede breast development. Early in puberty there is often an increase in normal vaginal discharge (physiologic leukorrhea), associated with uterine development. Girls or their parents may be concerned that this vaginal discharge is a sign of infection. The nurse can reassure them that the discharge is normal and a sign that the uterus is preparing for menstruation.

During midpuberty, breast enlargement occurs, and pubic hair progresses to adult-type sexual hair covering the mons pubis and labia majora. Most girls reach their peak height velocity and peak weight velocity in midpubescence.

The hallmark of late puberty is the first menstrual period, or menarche. Initial menstrual periods are usually scanty and irregular and may not be accompanied by ovulation. Ovulation and regular menstrual periods usually begin 6 to 14 months after menarche. Menarche occurs about 2 years after the appearance of breast buds, approximately 9 months after attainment of peak height velocity, and 3 months after attainment of peak weight velocity. The mean age of menarche in the United States is 12.55 years for non-Hispanic Caucasian, 12.06 for African-American, and 12.25 for Mexican-American girls, with a normal age range of  to

to  years (Chumlea, Schubert, Roche, et al, 2003). Menarche has been reported to occur at about 17% body fat, with 22% body fat reported to be required to maintain menstruation. Girls may be considered to have precocious puberty if breast development or pubic hair occurs before age 7 years for Caucasian girls or age 6 years for African-American girls, or if menarche occurs before age 10 years (Kaplowitz and Oberfield, 1999). Girls may be considered to have pubertal delay if breast development has not occurred by age 13 or if menarche has not occurred within 2 to

years (Chumlea, Schubert, Roche, et al, 2003). Menarche has been reported to occur at about 17% body fat, with 22% body fat reported to be required to maintain menstruation. Girls may be considered to have precocious puberty if breast development or pubic hair occurs before age 7 years for Caucasian girls or age 6 years for African-American girls, or if menarche occurs before age 10 years (Kaplowitz and Oberfield, 1999). Girls may be considered to have pubertal delay if breast development has not occurred by age 13 or if menarche has not occurred within 2 to  years of the onset of breast development.

years of the onset of breast development.

In the United States and most developed countries, the mean age of menarche has gradually decreased over the past century, corresponding to population improvements in nutrition, sanitation, and control of infectious diseases. This decline in the average age of menarche appears to have leveled off in recent years (Patton and Viner, 2007). Internationally, a decline in the average age at first menses has not been seen in countries where children are more likely to be malnourished and suffer from chronic illness.

Sexual maturation influences young peoples’ satisfaction with their appearance, but the effects appear to differ for girls and boys. For girls, physical maturation can lead to greater dissatisfaction with their appearance. For example, recent studies indicate that adolescent girls are more dissatisfied with their appearance and significantly more likely to identify themselves as being overweight than adolescent boys, even when they are at a normal weight for height (Smith, Stewart, Peled, et al, 2009). Normal increases in weight and fat deposition that accompany puberty among girls conflict with cultural norms that emphasize a slender look. Early-maturing girls suffer most because they begin to develop at a time when their age-mates still exemplify prepubertal slimness. Unfortunately, an all-too-common response to changes in body shape among teenage girls is to engage in extensive dieting at a time when nutritional requirements are at a peak. For some, the focus on slimness and dieting may trigger the development of eating disorders. (See Chapter 21.) Consequently, health promotion efforts related to pubertal growth, eating behaviors, and body image are important for adolescent girls, especially early-maturing girls.

Sexual Maturation in Boys: The first pubescent changes in boys are testicular enlargement accompanied by thinning, reddening, and increasing looseness of the scrotum. These events usually occur between  and 14 years of age. Early puberty is also characterized by the initial appearance of pubic hair. Penile enlargement begins, and testicular enlargement and pubic hair growth continue throughout midpuberty. During this period boys also undergo increasing muscularity, early voice changes, and development of early facial hair. Gynecomastia (breast enlargement and tenderness) is common during midpuberty. It occurs in up to one third of boys and is usually temporary. The spurts in height and weight occur concurrently toward the end of midpuberty. For most boys, breast enlargement disappears within 2 years. By midpuberty, there is a definite increase in the length and width of the penis, testicular enlargement continues, and first ejaculation occurs. Axillary hair develops, and facial hair extends to cover the anterior neck. Final voice changes occur secondary to the growth of the larynx.

and 14 years of age. Early puberty is also characterized by the initial appearance of pubic hair. Penile enlargement begins, and testicular enlargement and pubic hair growth continue throughout midpuberty. During this period boys also undergo increasing muscularity, early voice changes, and development of early facial hair. Gynecomastia (breast enlargement and tenderness) is common during midpuberty. It occurs in up to one third of boys and is usually temporary. The spurts in height and weight occur concurrently toward the end of midpuberty. For most boys, breast enlargement disappears within 2 years. By midpuberty, there is a definite increase in the length and width of the penis, testicular enlargement continues, and first ejaculation occurs. Axillary hair develops, and facial hair extends to cover the anterior neck. Final voice changes occur secondary to the growth of the larynx.

Precocious puberty in boys may be a concern if secondary sexual characteristics occur before age 9. Concerns about pubertal delay should be considered for boys who exhibit no enlargement of the testes or scrotal changes by ages  to 14, or if genital growth is not complete 4 years after the testicles begin to enlarge.

to 14, or if genital growth is not complete 4 years after the testicles begin to enlarge.

Changes in the size and shape of the penis and testicles and changes in genital functioning can be areas of great concern for adolescent boys. Although the ability for penile erection is present at birth, only with pubertal maturation do boys have seminal emissions. Ejaculation may occur spontaneously as a nocturnal emission, or “wet dream”; as a result of self-stimulation (masturbation); or during sexual activity with others. Unless they are prepared, boys may find spontaneous ejaculations puzzling, troublesome, and embarrassing. Pubertal changes and related concerns create important opportunities for health promotion among young teenage boys. Health care professionals can be a resource for boys and provide appropriate information and guidance around issues related to sexual maturation.

Physical Growth During Puberty

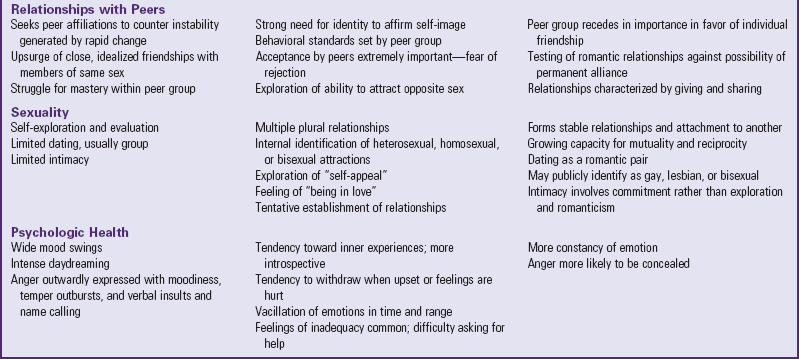

Along with increases in reproductive hormones and sexual maturation, major changes in skeletal and lean body mass occur during puberty. The final 20% to 25% of linear growth is achieved during puberty, and up to 50% of ideal adult body weight is gained during this time as well. The pubertal growth spurt refers to the general increase in growth of the skeleton, muscles, and internal organs, which reaches a peak rate at about 12 years of age in girls and about 14 years of age in boys. Although accelerated growth occurs in all adolescents, the age of onset, duration, and extent vary among individuals. Genetic endowment is the most important determinant of the onset, rate, and duration of pubertal growth, although adequate nutrition also plays a role.

Normal Patterns of Growth: Once the process of growth begins, the sequence of changes is progressive and usually predictable. Awareness of this sequence is not only important for reassuring concerned adolescents and parents but also useful in diagnosing conditions associated with abnormal growth. In general, girls begin puberty and reach maturity about  to 2 years earlier than boys. The pubertal growth spurt begins as early as

to 2 years earlier than boys. The pubertal growth spurt begins as early as  years or as late as

years or as late as  years in girls, and as early as

years in girls, and as early as  years and as late as 16 years in boys.

years and as late as 16 years in boys.

General growth includes accumulation of body mass, along with increases in height and weight. Lean body mass, primarily muscle mass, increases in both girls and boys during early puberty. For girls, the rate of muscle mass growth peaks at menarche and then slows. For boys, muscle mass continues to increase throughout puberty, resulting in the attainment of significantly higher lean body mass in boys than in girls. In girls, gain in fat mass increases markedly early in puberty and continues to increase after menarche. In boys there is a peak deceleration in the rate of fat mass accumulation at the time of their growth spurt, and thereafter a slower and much less dramatic increase than in girls.

The rate of linear growth (height) (Fig. 19-7) begins to increase in girls during early puberty, whereas in boys the rate does not increase until midpuberty. Peak height velocity (PHV) occurs at about 12 years of age in girls, around 6 to 12 months before menarche. PHV is used as a predictor of menarche; height at menarche is a predictor of ultimate adult height. Few girls grow more than 5 cm (2 inches) in height after menarche. Growth in girls’ height usually ceases 2 to  years after menarche. Boys typically reach PHV at about 14 years of age, after growth of the testicles and penis and the appearance of axillary and mature pubic hair. Among most boys, growth in height ceases at 18 or 20 years of age. Increases in leg length tend to precede growth of the trunk by about 6 to 9 months and that of the shoulders and chest by about 1 year. In short, teenagers tend to follow a linear growth pattern in which they outgrow their shoes first, then their pants, and finally their shirts. Peak weight velocity occurs about 6 months after PHV in girls. In contrast, weight and height spurts occur simultaneously for boys. On average, girls gain 5 to 20 cm (2 to 8 inches) in height and 7 to 25 kg (15.5 to 55 lb) in weight during adolescence, and boys gain 10 to 30 cm (4 to 12 inches) in height and 7 to 30 kg (15.5 to 66 lb) in weight during adolescence.

years after menarche. Boys typically reach PHV at about 14 years of age, after growth of the testicles and penis and the appearance of axillary and mature pubic hair. Among most boys, growth in height ceases at 18 or 20 years of age. Increases in leg length tend to precede growth of the trunk by about 6 to 9 months and that of the shoulders and chest by about 1 year. In short, teenagers tend to follow a linear growth pattern in which they outgrow their shoes first, then their pants, and finally their shirts. Peak weight velocity occurs about 6 months after PHV in girls. In contrast, weight and height spurts occur simultaneously for boys. On average, girls gain 5 to 20 cm (2 to 8 inches) in height and 7 to 25 kg (15.5 to 55 lb) in weight during adolescence, and boys gain 10 to 30 cm (4 to 12 inches) in height and 7 to 30 kg (15.5 to 66 lb) in weight during adolescence.

Other Physiologic Changes

In addition to the characteristic changes of puberty already discussed, numerous others occur. The size and strength of the heart, blood volume, and systolic blood pressure increase, whereas the heart rate decreases. Consistent with the general developmental timetable, these changes appear earlier in girls, who establish a slightly higher pulse rate and a slightly lower systolic blood pressure than boys. Blood volume, which has increased steadily during childhood, reaches higher levels in boys than in girls, a fact that may be related to the increased muscle mass in pubertal boys. Adult values are reached for all formed elements of the blood. For instance, there is a marked increase in serum iron, the number of red blood cells, hemoglobin, and hematocrit in boys, but not in girls.

The lungs increase in both diameter and length during puberty. The respiratory rate, decreasing steadily throughout childhood, reaches the adult rate in adolescence. Respiratory volume, vital capacity, and other physiologic properties related to respiratory function are increased, and to a greater extent in boys than in girls. The differences between the sexes are a result of the greater lung growth associated with boys’ increased shoulder and chest size.

The rate of steady decline in basal metabolic rate from birth to adulthood slows during puberty, coinciding with the growth spurt in both sexes, reflecting the increase in physiologic activities. A slightly higher metabolic rate in boys than in girls is probably a function of differences in androgenic hormones. Basal body temperature gradually decreases with age in both sexes, reaching adult values by 12 years of age in girls and somewhat later in boys.

Adolescence is also a time of continued brain growth. Although the number of neurons does not increase, there is a proliferation of the support cells that brace and nourish the neurons, and an increase in the number of neural connections. Development of these connections within the cortex of the brain continues during adolescence and may not reach adult levels until after age 20. In addition, the growth of the myelin sheath around the nerve cells continues through and beyond puberty, enabling faster neural processing. This “fine tuning” of the neural system coincides with development of the more advanced cognitive capacities of youth, but continues into early adulthood. Recent studies have shown, for example, that the frontal cortex areas of the brain, associated with executive functions, continue myelinization into the twenties, and may not be complete until as late as age 25.

Cognitive Development

Emergence of Formal Operational Thought (Piaget)

Jean Piaget (1972) described the shift from childhood to adolescence as a movement from concrete to formal operational thought. Children’s thinking is oriented to things and events that they can observe directly. Unable to think in terms of abstract possibilities, they process information based on what is directly observable. For most young people, emergence of formal operational thinking occurs between the ages of 11 and 14. Formal operational thought includes being able to think in abstract terms, think about possibilities, and think through hypotheses. Young people become able to think about abstractions; thus they can symbolically associate behaviors with abstract concepts such as attractiveness, adult status, or happiness. Adolescents also become capable of using a future time perspective rather than being tied to the here-and-now thinking of childhood. They are able to imagine possibilities, such as a sequence of future events that might occur, including college or occupational opportunities, or how current situations, such as relationships with parents or friends, could change to meet an imagined ideal.

Hypothetical reasoning is aligned with thinking about possibilities. To think through hypotheses, one needs to see beyond what is directly observable and reason in terms of what might be possible. Hypothetical thinking allows adolescents to systematically generate alternative possibilities and explanations and to compare what they actually observe with what they believe is possible. In practical terms, being able to plan ahead and identify future consequences of possible actions are skills dependent on being able to think hypothetically.

The health care provider’s ability to assess an adolescent’s level of cognitive development has important implications for health promotion. Older adolescents may be able to consider some of the symbolic and long-term implications of their behaviors. Thus they may respond to health promotion efforts that require a future time perspective or attention to symbolic rewards. For young people who primarily use concrete thinking (i.e., younger teenagers), health promotion efforts should emphasize immediate risks or benefits of the behavior.

Along with cognitive development, decision-making abilities increase over the adolescent period. Young people develop the ability to consider hypothetical risks and benefits of possible behaviors, along with potential consequences of such behaviors. In addition, the likelihood of teenagers consulting with adult experts, mentors, and role models increases over the junior and senior high school years. By middle adolescence, most teenagers are able to reason as well as adults. Health promotion efforts, especially those aimed at younger adolescents, should offer learning strategies that enhance decision-making skills. Such efforts might include discussions emphasizing health-promoting norms for behavior among young people and alternatives to unhealthy behaviors, along with opportunities to practice skills necessary to resist unhealthy behaviors.

Even with the best framework for health promotion, persons who are capable of formal operational thought and reasoned decision making do not use these processes all the time. When faced with time pressures, personal stress, or overwhelming peer pressure, young people are more likely to abandon rational thought processes. Thoughts about unfamiliar or emotionally arousing topics also tend to be less sophisticated and more vulnerable to the effects of stress and pressure. Unfortunately, many of the health-related decisions adolescents confront, such as those related to substance use or sexual behavior, involve issues that are personally stressful, emotion laden, or new. Under such conditions, people tend not to use their capacities for abstract formal reasoning, even if they typically use advanced decision-making skills.

Adolescent Conceptions of Self

With development of formal operational thought, adolescents become able to describe the self more abstractly. Compared with children, they are more psychologic in their self-descriptions, focusing on personal and interpersonal characteristics, beliefs, and emotional states. They also develop a more differentiated self-concept, recognizing that their behavior and performance vary from setting to setting. With time, they become able to integrate these disparate observations of self into abstract personal characterizations (e.g., “I am a sensitive person”).

Psychologic theories help explain how teens use these powerful new cognitive tools to make the transition to adult roles and relationships (Elkind, 1978; Lapsley, 1993). Being able to think about one’s own thoughts and emotions can lead to periods of extreme self-absorption, what Elkind called adolescent egocentrism. This self-absorption has also been described by Lapsley as a way of imagining and “trying on” various personas and practicing hypothetical interactions in an attempt to develop a separate sense of self.

Two common patterns of thinking help explain some of the health-related beliefs and behaviors of youth. The first, the imaginary audience, involves having such a heightened sense of self-consciousness that an adolescent imagines that everyone notices and is focused on his or her behavior. For example, a teen who has diabetes may worry about injecting insulin at school because “everybody will notice.” The second pattern of thinking, called the personal fable, is the belief that one’s feelings and experiences are completely unique, or that one is all-knowing or invulnerable. This helps explain the common accusation from younger teens towards adults, “You just don’t understand!” as well as some of their decisions around risk behaviors. For example, a sexually active adolescent may choose not to use condoms for safe sex, truly believing that “other people can get STIs, but not me,” or an adolescent who has been drinking may choose to drive home after a party, believing that he or she will not be affected by the alcohol.

There is growing evidence that the inward-focused or narcissistic egocentrism of early adolescence may be an important developmental mechanism that leads to positive mental health, but teens with a strong sense of invulnerability in their personal fable are more likely to engage in risky behaviors that can lead to injury, and teens whose personal fable is focused on their uniqueness may be at higher risk for depression and suicidal ideation (Aalsma, Lapsley, and Flannery, 2006).

Changes in Social Cognition

Gains in cognitive abilities also have an impact on perspective-taking capacities of young people. Adolescents are better able than children to “step into the shoes” of others. During elementary school, children begin to realize that other people have thoughts and feelings; however, they have difficulty understanding that what affects their own thoughts and feelings can also influence the thoughts and feelings of others. Preadolescents develop limited perspective-taking skills, first learning to step into the shoes of best friends, then peers and family members, and finally people of other ages and backgrounds.

Perspective-taking capacities develop further as adolescents become able to engage in mutual role taking. In other words, teenagers can both understand the perspectives of others and see how the thoughts or actions of one person can influence those of others. Role-taking capabilities continue to expand throughout adolescence. They are able to discuss various issues highlighting points of importance to people in various social roles (e.g., “From a parent’s perspective, having a curfew is important because …”). Older adolescents also realize that the perspectives people hold are complicated in that they are influenced by a range of intrapersonal, interpersonal, and sociocultural factors.

Ultimately, gains in perspective-taking skills that take place during adolescence lead to an increased capacity to learn from the experiences of others. Older adolescents are able to consider the choices, behaviors, and outcomes experienced by others in making their own health-related choices. This newfound capacity significantly expands the opportunities to learn health-promoting behaviors.

Development of Value Autonomy

With advances in cognitive development, adolescents’ beliefs become more abstract and increasingly rooted in general ideologic principles. At the same time, young people are gaining increasing emotional independence from parents, relying less on their parents’ beliefs and values than they did as children. Adolescents also progress toward greater behavioral independence, encountering situations and decisions they have not previously experienced. With these new capacities and experiences, young people face a variety of cognitive conflicts as they compare the advice of parents and friends and deal with competing pressures to behave in given ways. These conflicts may prompt young people to consider, in serious and thoughtful terms, what they themselves really believe. Whereas earlier in life they may have merely accepted the decisions or points of view of adults, adolescents begin to substitute a set of values distinct from those of significant adults in their lives. This struggle to clarify values, created in part by an expanded behavioral independence, is a large part of the process of developing what has been termed value autonomy (Steinberg, 1990). The development of a personal value system is a gradual process, with evidence that value autonomy occurs relatively late in adolescence, between the ages of 18 and 20 (Steinberg, 1990).

Moral Development

Moral development parallels advances in reasoning and social cognition. With the attainment of abstract thought and the realization that people’s perspectives and opinions may differ, the ways adolescents approach moral issues change. According to one theory of moral development (Kohlberg and Gilligan, 1972), older children and young adolescents function at a conventional level of moral reasoning in which absolute moral guidelines are seen to emanate from authorities such as parents or teachers. Thus judgments of right and wrong are made according to a set of concrete rules. A major concern is to act or behave in ways that will gain or maintain the approval of others. The correctness of society’s rules is not questioned—one “does one’s duty” by upholding and respecting the social order.

Elements of principled moral reasoning emerge during adolescence. With this level of reasoning, adolescents question absolutes and rules and view moral standards as subjective and based on points of view that are subject to disagreement. One may have a moral duty to abide by social standards for behavior, but only insofar as those standards support and serve human ends. Thus occasions arise in which social conventions ought to be questioned and when principles such as justice, caring, or quality of life take precedence over established social norms. Empirical research on Kohlberg’s theory has demonstrated that aspects of both conventional and principled reasoning are present during adolescence, and different levels of reasoning are used at different times and in different situations.

Kohlberg’s scheme of moral development focuses on an orientation to justice. This orientation holds as its ideal a morality based on reciprocity and equal respect. From this orientation the most important consideration in making moral decisions would be whether the individuals involved were treated “fairly” by the ultimate decision. Gilligan (1982) proposes that an equally valid alternative to the justice orientation is one that emphasizes caring. From this perspective, the ideal is a morality of attention to others and responses to human need. As opposed to the justice orientation, which assumes that moral decisions are best made from a detached position of objectivity, the caring orientation is rooted in the belief that moral decisions should be shaped by attachments and responsiveness to others. Studies have found that although both men and women are capable of approaching moral problems from the perspectives of justice and caring, women may be more likely to give caring-oriented responses before justice-oriented ones, whereas men are more likely to follow the opposite pattern (Gilligan, 1986; Walker, de Vries, and Trevethan, 1987).

Spiritual Development

Religious beliefs also become more abstract and principled during the adolescent years. Specifically, adolescents’ beliefs become more oriented toward spiritual and ideologic matters and less oriented toward rituals, practice, and the strict observance of religious customs. Compared with children, adolescents place more emphasis on the internal aspects of religious commitment, such as what a person believes, and less on the external manifestations, such as whether an individual attends religious worship (Elkind, 1978).

Generally, the stated importance of participation in organized religion declines somewhat during the adolescent years. More high school students than postsecondary school young people attend religious services regularly, and, not surprisingly, the younger the adolescents, the more likely they are to view religion as being important to them. Among older adolescents, the importance of organized religion declines more among college students than among those not in college. Late adolescence appears to be a time when individuals reexamine and reevaluate many of the beliefs and values of their childhood. Consistent with developmental changes in value autonomy, the religious beliefs of young people are likely to become more personalized and less bound to the traditional religious practices they may have been exposed to when they were younger.

Although religious cults and dramatic religious conversion have attracted a great deal of attention in the media, they remain rare phenomena among American adolescents and often reflect nonreligious concerns. Membership in a religious cult is often associated with a preceding period of psychologic stress, identity diffusion, rootlessness, and dissatisfaction with mainstream societal values.

Psychosocial Development

The task of identity formation is to develop a stable, coherent picture of oneself that includes integrating one’s past and present experiences with a sense of where one is headed in the future. Before adolescence the child’s identity is like pieces of a puzzle scattered on a table. Both cognitive development and social situations encountered during adolescence push individuals to combine puzzle pieces—to reflect on their place in society, the way others view them, their own sense of self-worth, and their options for the future. For most individuals, puzzle pieces first form a coherent whole sometime during late adolescence and early adulthood. Erik Erikson, one of the most influential theorists in the area of psychosocial development, describes identity achievement as one of the main psychosocial tasks of the adolescent years. According to Erikson (1968), “From among all possible and imaginable relations [the adolescent] must make a series of ever-narrowing selections of personal, occupational, sexual, and ideological commitments.”

Social forces play a large role in shaping an adolescent’s sense of self. Erikson (1968) argues that the key to identity achievement lies in adolescents’ interactions with others. The people with whom a young person interacts serve as mirrors that reflect information back to the adolescent about whom she or he is and who she or he ought to be. During the period of identity formation, adolescents also learn from others what they ought to keep doing and what they ought not to do. Society also plays an important role in determining the range of available alternatives open to young people involved in identity formation. Optimally, adolescents have the opportunity to explore a range of possible options related to ideologic, occupational, and interpersonal roles before making an identity commitment.

The status of personal commitments in occupational, social, and ideologic domains can measure progress towards identity achievement. The status of personal commitments has four proposed levels: achievement, moratorium, foreclosure, and diffusion (Marcia, 1966). Individuals who demonstrate identity achievement have established a coherent identity after actively exploring possible alternatives; individuals currently engaged in this exploration are in moratorium. Foreclosure refers to making identity commitments without a period of exploration or experimentation, and identity diffusion refers to a lack of firm identity commitments, along with a lack of effort to make those commitments. During adolescence, many individuals progress from diffusion to moratorium to identity achievement, or, alternatively, from diffusion to foreclosure.

Experiences and opportunities within one’s social environment influence both the content of identity and progression toward identity achievement. Among ethnic minority adolescents, identity foreclosure may be more common than among teenagers from the majority culture because of restricted opportunities to explore alternative roles. Identity diffusion also appears to be more common among minority boys and men than among other groups. Possible barriers to identity formation among minority youth may include conflicting values between their minority ethnic group and the broader society, a lack of adult role models who exemplify positive ethnic identity, and inadequate preparation for stereotyping and prejudice that are frequently experienced. However, many ethnic minority adolescents develop effective bicultural identities and abilities to navigate the cultural expectations of home and society, and positive connections to cultural identities can foster healthy adolescent development.

Development of Autonomy

Becoming an autonomous, self-governing person is another of the fundamental psychosocial tasks of adolescence. Autonomy includes emotional, cognitive, and behavioral components. Emotional autonomy is that aspect of independence related to changes in an individual’s close relationships, and behavioral autonomy is the capacity to make independent decisions and follow through with them. Generally, emotional and behavioral autonomy are likely to surface as psychosocial concerns somewhat earlier during adolescence than value autonomy, which usually does not become a prominent concern until middle or late adolescence.

Individuals generally begin the process of emotional autonomy during early adolescence by becoming more emotionally independent from their parents but less separate from their friends. In the process of separating from their parents, younger adolescents often shift a portion of their emotional ties to other adults, often developing “crushes” on teachers, coaches, celebrities, or the parent of a best friend. By the end of adolescence, individuals are less emotionally dependent on their parents than they were as children. This emotional autonomy can be seen in several ways. First, older adolescents do not generally rush to their parents when they are worried or upset. Second, they no longer see their parents as all-knowing or all-powerful. Third, teenagers often have more emotional energy invested in relationships outside their families. Finally, older adolescents are able to see and interact with their parents as people, not just as their parents.

As adolescents increasingly find themselves in situations where adults are not present and where they must make decisions and take responsibility for their own actions, the extent to which they are capable of independent decision making and autonomous behavior takes on added importance. An individual who is behaviorally autonomous is able to turn to others for advice when it is appropriate, weigh alternative courses of action based on his or her own judgment and the suggestions of others, and reach an independent conclusion about how to behave. Behavioral autonomy includes the ability to make independent decisions based on one’s own choices rather than conforming to the opinions of others. Decision-making abilities improve over the adolescent years, with older adolescents being more likely than younger adolescents to be aware of risks and benefits involved with a particular decision, to consider future consequences, to turn to “experts” for advice, and to realize when vested interests may influence the advice of others. Conformity to parents’ opinions declines during early adolescence. However, conformity to peer influence increases during this time. During middle and late adolescence, conformity to both parent and peer opinions declines, allowing for genuine behavioral autonomy. Subjective feelings of self-reliance increase steadily over the adolescent years.

In contrast to popular stereotypes, the development of autonomy during adolescence does not typically involve rebellion, nor is it usually accompanied by strained or tense family relationships. In households where guidelines for adolescent behavior are clear and consistently enforced; where changes in guidelines are open to discussion; and where an atmosphere of interpersonal warmth, concern, and fairness exists, family relationships nurture a gradual and smooth maturational process over the course of the adolescent years. Problems in the development of autonomy are often understandable reactions to excessively controlling circumstances or to growing up in the absence of clear standards. In addition to dispelling the myths that major parent-child conflicts and adolescent rebellion are essential to the development of autonomy, research has shown that parent and peer influences are not necessarily opposing forces but can play complementary roles in the development of a healthy degree of individual independence.

Achievement

Another set of psychosocial tasks encountered during adolescence centers around achievement. Broadly speaking, achievement concerns the development of motives, capabilities, interests, and behaviors related to performance in evaluative situations. The study of achievement during adolescence has focused almost exclusively on young people’s performance in educational settings and on the development and implementation of plans for future scholastic and occupational careers. Various theories have attempted to explain why some young people achieve at higher levels in school. Some have focused on differences in individuals’ motivations to succeed. Others have examined young people’s beliefs about success and failure. Still others have pointed to differences in adolescents’ opportunities for success and to the roles of important adults and peers in their lives. Various indicators of achievement are highly interrelated. For example, success in school during the early elementary years leads to later success in school; doing well in school generally leads to higher levels of educational attainment, which in turn lead to more challenging forms of employment with greater earning power.

Although there are distinct differences among different occupations, the actual process leading toward occupational achievement can be a lengthy one in contemporary society. Because career options have expanded and changed so dramatically, and because increasing numbers of individuals enter college after completing high school, many people do not decide on a career until well into adulthood.

A definite relationship exists between social class and both educational and occupational achievement. A significant problem facing those interested in promoting achievement during adolescence is socioeconomic disparities in educational and occupational achievement. Beginning in early childhood, through no action of their own, many individuals find themselves on an educational course that directs them toward low levels of academic achievement, curtailed schooling, and limited occupational mobility. They reach adulthood with little hope and few dreams for their future. Understanding how this course is set in motion and identifying factors that help individuals from economically disadvantaged backgrounds succeed despite tremendous barriers are necessary steps in building interventions that promote the development and health of these young people.

Sexuality

Adolescence represents a critical time in the development of sexuality. Hormonal, physical, cognitive, and social changes that occur during adolescence all have an impact on sexual development. Of all the developmental changes that affect adolescent sexuality, none is more obvious than the impact of puberty. Adolescents must come to terms with hormonal influences, physiologic manifestations such as menstruation and ejaculation, and physical changes such as breast and genital development. All these changes have a profound impact on the way teenagers perceive their bodies (i.e., body image). In addition to transitions in body image, increasing levels of pubertal hormones contribute to increased levels of sexual motivation among both boys and girls. Evidence also suggests that early development of secondary sexual characteristics is associated with early sexual activity. For example, some early-maturing girls begin dating earlier and may have sexual intercourse at younger ages than their peers (Doswell, Millor, Thompson, et al, 1998). Even when physical development occurs at an average onset and pace, the degree to which adolescents feel comfortable with their bodies may affect sexual behaviors.

Changes in sexual motivations and feelings, happening at the same time as shifts in cognitive skills, contribute to painful conjectures (“Is what I’m feeling normal?”), self-conscious concern (“Am I good looking enough?”), and hypothetical thinking (“What if she wants to have sex?”). The emergence of formal operational thinking also increases adolescents’ decision-making capabilities concerning sexual issues. As they mature, teenagers become better able to think through potential risks and benefits of sexual behaviors before they engage in them. Older adolescents may also be able to conceptualize more long-term consequences of present behaviors. One of the important tasks of adolescence is to incorporate sexuality successfully into intimate relationships (Sullivan, 1953). This task is made possible by the advanced cognitive abilities that emerge over the course of adolescence.

Part of adolescent identity formation involves the development of sexual identity. As they begin to integrate changes involved with puberty, young adolescents also develop emotional and social identities separate from their families. For young adolescents, the process of sexual identity development usually involves forming close friendships with same-sex peers, with whom they may experiment sexually, often to satisfy curiosity. Sexual activity among young teenagers varies by gender. Masturbation provides an opportunity for sexual self-exploration; participation in this behavior is influenced by learned cultural attitudes and sex-role expectations. Boys typically begin masturbating during early adolescence; the age of first masturbation varies greatly for girls. Although some girls begin masturbating during early adolescence, many do not masturbate until after they have had intercourse. Similarly, a small number of teens may engage in oral sex during early adolescence, but the percentage of teens who report oral sex at each age is similar to the percentage of teens who report sexual intercourse, suggesting that oral sex does not necessarily precede intercourse (Brewster and Tillman, 2008; Smith, Stewart, Peled, et al, 2009). Although the age of initiating sexual intercourse has been getting older among teens in the past decade in the United States, about one third of teens have had sexual intercourse by age 15. These young people are at high risk for STIs and pregnancy.

Many teenagers begin to make a shift from relationships with same-gender peers to intimate relationships with opposite-gender partners during middle adolescence (Fig. 19-8). Opposite-gender relationships typically begin with peer activities involving both boys and girls. Pairing off as couples becomes more common as middle adolescence progresses. The type and degree of seriousness of partner relationships vary. Initial relationships are usually noncommittal, extremely mobile, and seldom characterized by any deep romantic attachments. Sexual activity (whether with same- or opposite-gender partners) becomes more common during middle to late adolescence. Nationally, approximately 38% of ninth-grade boys and 27% of girls report having had sexual intercourse. By twelfth grade, 62% of boys and 68% of girls report having had intercourse (Eaton, Kann, Kinchen, et al, 2008). Around 11% of girls and 5% of boys report same-gender sexual partners (Mulye, Park, Nelson, et al, 2009).

The relationship between love and sexual expression is brought into focus during middle adolescence. Most young people oppose exploitation, pressure, or force in sex as well as sex solely for the sake of physical enjoyment without a personal relationship. Many adolescents find it hard to believe that sex can exist without love; therefore they view each relationship as real love. However, some teen social groups have embraced norms that include sexual relationships with friends who are not considered exclusive romantic partners, but rather “friends with benefits.”

The meaning and implication of sexual activity as it affects psychosocial development may be quite different for adolescent boys and girls; that is, sexual socialization differs for males and females in our society. Typically, adolescent boys’ first sexual experiences are in early adolescence through masturbation. Before adolescent boys begin dating, they have generally already experienced orgasm and know how to arouse themselves sexually. For boys, the development of sexuality during adolescence revolves around efforts to integrate the formation of close relationships into an already existing sense of sexual capability. Girls’ first sexual experiences are likely to be different and to carry different meanings. Masturbation is a less prevalent activity among girls, and it is less regularly practiced. The adolescent girl, in contrast to the adolescent boy, is more likely to experience sexual intercourse for the first time in a perceived close relationship. For girls, the development of sexuality involves the integration of sexual activity into an existing capacity for emotional involvement.

An integrated sexual identity often emerges during late adolescence as individuals incorporate sexual experiences, feelings, and knowledge. For most, this identity is consistent with their own physical and mental capacities and with societal limits and expectations. Most older adolescents identify themselves as being predominantly heterosexual or mostly heterosexual, with a smaller number self-identifying as bisexual, or gay or lesbian; an even smaller group is still unsure of their sexual orientation, although this varies somewhat by ethnicity (Russell, Seif, and Truong, 2001; Saewyc, Poon, Wang, et al, 2007). Whatever their sexual orientation, most older teenagers possess the capacity to have intimate relationships that satisfy the emotional and sexual needs of both partners.

Sexual orientation is an important aspect of sexual identity. Sexual orientation is defined as a pattern of sexual arousal or romantic attraction toward persons of the opposite gender (heterosexual), of the same gender (homosexual, often called gay or lesbian), or of both genders (bisexual). Sexual orientation encompasses several dimensions, including attraction, fantasy, actual sexual behavior, and self-labeling or group affiliation. In individuals the direction and intensity of each dimension are not necessarily consistent with any of the others. For example, individuals may be attracted most strongly to their same gender, fantasize about both genders, have sexual activity only with the opposite gender, and identify as gay or lesbian. Other individuals may engage in same-gender sexual behavior, fantasize about both genders, but identify as heterosexual. As with all aspects of sexual identity, cultural meaning and expectation, gender, peer groups, opportunities for intimacy, and other environmental contexts all influence sexual orientation. Research has suggested that the trajectory of developing sexual orientation may be different for boys and girls, and that girls’ sexual behaviors and attractions may be more fluid (Diamond, 2000).

Adolescence is the period during which individuals commonly begin to identify their sexual orientation as part of their developing sexual identity. However, cultural beliefs and values, societal and family pressures, or a lack of similar peers can influence this identification process. The majority of adolescents eventually report an orientation toward exclusively heterosexual relationships. For adolescents whose orientation encompasses any same-gender dimensions, the identity process during adolescence can be complicated, especially when community norms disapprove of orientations other than heterosexual. Adolescents who have witnessed harassment or violence directed at gay, lesbian, and bisexual people, for example, may be reluctant to self-identify, even when their attractions and behaviors are exclusively same-gender or bisexual. In several population-based studies throughout the 1990s, researchers found approximately 1% to 5% of adolescents identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual, whereas 3% to 12% report same-gender or bisexual orientation in one or more of the other dimensions of sexual orientation (Reis and Saewyc, 1999).

The development of sexual orientation as part of sexual identity includes several developmental milestones during late childhood and throughout adolescence. These milestones do not necessarily occur in the same order for everyone, nor are they completed in the same amount of time (Rosario, Meyey-Bahlburg, Hunter, et al, 1996). They include (1) the realization of romantic or erotic attraction to people of one (or both) genders; (2) erotic daydreaming about one or both genders; (3) romantic partners or dates without sexual activity; (4) sexual activity with people of the preferred gender or genders (also, for some teens, sexual activity with a nonpreferred gender, due to curiosity or social pressure); (5) self-identification of the orientation that best fits one’s current circumstances and understanding; (6) publicly self-identifying that orientation, usually to intimate friends and family first, then the wider social group; and (7) an intimate, committed sexual relationship with a person of the gender appropriate to one’s orientation.

The order of these milestones varies greatly among adolescents, but adolescents who identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual tend to publicly self-identify later than their heterosexual peers. Without positive gay, lesbian, or bisexual role models or a supportive peer group, sexual minority teens can feel isolated, and they may not share their orientation with anyone for fear of rejection or violence (see Critical Thinking Exercise). When adolescents who would otherwise identify as bisexual can only find a peer group of gay and lesbian teens, they may focus on their same-gender dimensions of orientation and adopt the label of lesbian or gay; later, they may self-label as bisexual. Likewise, some gay and lesbian adolescents may first identify as heterosexual, then bisexual, before identifying as gay or lesbian. In studies among self-identified gay, lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual adolescents, many of the adolescents report changing their self-labels one or more times during their adolescence and beyond (Rosario, Meyey-Bahlburg, Hunter, et al, 1996; Diamond, 2000).

Although only a few states in the United States, some European countries, and Canada legally recognize same-gender marriages at present, some religious faiths and social groups do celebrate committed same-gender couples’ relationships. There is no evidence that gay, lesbian, or bisexual adults are more or less likely to create long-term, stable relationships than are heterosexual couples. It should be noted that bisexual adolescents and adults do not generally engage in sexual relationships with both genders concurrently; self-identification as bisexual usually refers to the ability to be attracted to either gender but does not imply that such a person requires partners of both genders, or that one must be equally attracted to and have sexual experience with both genders in order to be bisexual.

Intimacy

Intimate relationships are emotional attachments between two people characterized by concern for each other’s well-being; a willingness to disclose private, possibly sensitive topics; and a sharing of common interests and activities. Intimate relationships are distinct from sexual relationships. It is possible for individuals to have close relationships without becoming sexually involved. At the same time, people can be involved in sexual relationships that are not particularly intimate.

It is not until adolescence—a time characterized by pubertal changes, advances in social cognitive abilities, and broadening of social worlds—that truly intimate relationships first emerge. Adolescents’ close friendships are more likely to include a strong emotional foundation in which individuals understand and care about each other. The development of intimacy during adolescence involves changes in the adolescent’s needs for intimacy and in the capacity and opportunities to have intimate friendships. Puberty and its resultant changes in sexual impulses often raise new issues and concerns requiring serious, intimate discussions. Over the course of the adolescent years, individuals become more capable of and interested in emotional closeness with other people. The greater degree of behavioral independence often accompanying the transition into adolescence provides more opportunities for teenagers to be alone with friends and to come into meaningful contact with adults outside their families. Although research on intimacy during adolescence has focused on peer friendships, intimate relationships are by no means limited to peers. Teenagers may also develop intimate relationships with parents, siblings, and adults who are not part of their immediate families.

Harry Stack Sullivan (1953) was among the first to describe the developmental course of intimacy. Usually adolescents develop the capacity for intimacy through preadolescent and early adolescent relationships with same-gender peers. Intimate relationships with opposite-sex peers develop relatively late during adolescence. Opposite-gender friendships may play a more important role in the development of intimacy among boys than among girls, who may develop and experience intimacy with other girls earlier in adolescence.

Individuals move through a series of stages in their close relationships with others. Many adolescents move into role-focused friendships, behaving in ways that are dominated by conventional norms. In their close relationships, individuals at this level attempt to avoid controversy and control their emotions. Role-focused persons are generally more concerned with conforming to the appropriate roles and norms in a relationship (e.g., what the “good” girlfriend does) than with a friend as an individual. It is not until later in adolescence that people develop the capacity for having individuated-connected friendships. With this level of friendship, individuals form intimate relationships with others that acknowledge the complexity and contradictions in close relationships. Differences in outlook between individuals are not only tolerated but encouraged as part of what makes the relationship vital.

Although teenagers may begin dating during early adolescence, these early dating relationships are not usually psychosocially intimate. Early dating relationships typically follow highly ritualized “scripts,” in which adolescents are more likely to play stereotypic roles than to really be themselves. Participating in mixed-gender group activities, such as going to parties or other events, may have a positive impact on young teenagers’ well-being. One-on-one dating during early adolescence, however, with a lot of time spent alone, may lead to sexual intimacy before a teen is ready. A moderate degree of dating, with serious relationships delayed until late adolescence, may be the ideal pattern of interpersonal involvement.

Social Environments

Although all adolescents experience similar biologic and cognitive changes and face similar psychosocial tasks, the health-related effects of these changes are not the same for all people. Why aren’t individuals affected in the same ways by puberty, by changes in thinking patterns, and by changes in social and legal status? The answer lies in the fact that biologic, cognitive, and social changes of adolescence are shaped by the social environment in which the changes take place (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). The social environment provides the opportunities, barriers, role models, and support for individuals’ development and health. Systems within the social environment, including family, peers, schools, community (including Internet-based community), and the larger society, all contribute uniquely to an adolescent’s development and health.

The nurse can use an ecologic model as a way of understanding adolescents’ social environments (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). In this model the social environment is divided into proximal and more distal systems. The social environment includes microsystems, mesosystems, exosystems, and macrosystems.

Microsystems are the most proximal social contexts in which adolescents participate directly, such as family, peer groups, school, and the workplace. All these contexts have substantial influences on the development and health-related behaviors of adolescents (Perry, Kelder, and Komro, 1993).

The next layer of social environment, mesosystems, is formed by linkages between microsystems. The extent to which individuals in one microsystem are involved in other systems determines the strength or “richness” of the mesosystem. For example, regular interactions between family members and school personnel, which have positive effects on student achievement and school performance, reflect a rich mesosystem.

The third layer of social environment, exosystems, consists of settings that influence adolescent behavior and development but in which they do not directly participate. Many community-level influences fall within this layer. These include opportunities within a community for health-enhancing or health-compromising behaviors, such as the availability of age-appropriate activities for young people that do not include alcohol, tobacco, or drugs.

The most distal social environment, macrosystems, consists of culturally based belief systems and economic and political systems. These systems can have profound effects on young people’s health-related behaviors and development, mostly through their influences on more proximal systems. Social systems are embedded within each other, and what happens within one system can influence what happens in others. To have the most impact on adolescent health promotion, interventions must address multiple environmental systems.

Families

Over the past several decades, changes have taken place within the family microsystem that have important implications for adolescent health. Higher rates of divorce and remarriage, increasing numbers of single-parent or blended families, and greater percentages of working mothers have become characteristic of contemporary U.S. society. The “ideal” family consisting of an employed father, an at-home mother, and two or more school-age children is no longer the norm for American society. Higher rates of divorce and the decisions of single women to have children have increased the number of U.S. children spending at least part of their childhood in a single-parent family. Correspondingly, many young people find themselves in blended families, thus developing relationships with stepparents during their adolescent years. A growing number of same-gender couples are raising their own or adopted children as well; in the 2000 census, an estimated 250,000 households were headed by same-gender partners (Bennett and Gates, 2004). Changes in family structure have been accompanied by changes in parent work patterns and a dramatic increase in the percentage of mothers who work outside the home (Gottfried and Gottfried, 1994). (See Family Structure, Chapter 3.)

These changes in family structure and parent employment have resulted in young people having more time unsupervised by adults with increased time alone or with peers. Although for mature adolescents little risk may be involved with minimum supervision, for less competent teenagers, decreased adult supervision may result in more risk-taking behaviors, such as substance use and sexual intercourse. Poorly monitored teenagers may also socialize with peers who engage in risky behaviors. Lack of adult supervision also decreases adolescents’ opportunities for communication and intimacy with a parent or other supportive adults. Although quantity of time does not guarantee quality, sufficient quantity is necessary for communication and the development of intimate relationships.

Consistently, adolescents who feel close to their parents show more positive psychosocial development and behavioral competence, less susceptibility to negative peer pressure, and lower tendencies to be involved in risk-taking behaviors (Resnick, Bearman, Blum, et al, 1997; Smith, Stewart, Peled, et al, 2009). In many situations lack of direct adult supervision may be counterbalanced by parent monitoring and communication about adolescents’ activities during parental absence.

On the other hand, in dysfunctional or abusive families, spending greater amounts of time with parents may compromise the health of teenagers. In these situations the type and content of communication may be the most important factors to address.

In addition to adult supervision, the overall parenting style affects adolescent development. Both effective conflict resolution within families and family cohesion create environments conducive to healthy adolescent development. These two characteristics, along with parent expectations for mature behavior on the part of the adolescent and the practice of setting and enforcing reasonable limits for behavior, form the basis of effective parenting. This parenting style, termed authoritative parenting, is related to greater psychosocial maturity and school performance and less substance abuse among young people.

Adolescents from low-income households are more likely than other adolescents to spend less supervised time with adults, to have parents working at more than one job, to drop out of high school, and to experience violence in their homes and communities. Although disorder within their larger social environments often creates a need for a buffer, which could include spending quality time with adults, poor adolescents often experience fewer of these health-enhancing activities.

Nurses should be cautious, however, in attributing differences in adolescent risk behaviors to racial or ethnic group membership, socioeconomic status, or family structure.

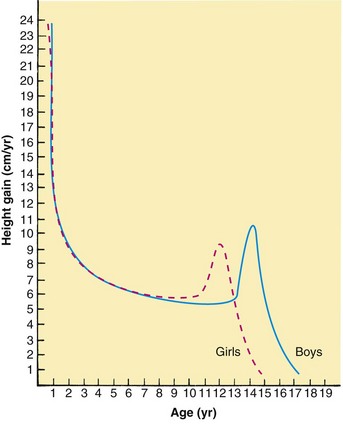

Peer Groups

One hallmark of adolescence is the increasing value young people place on friendships and relationships with peers (Fig. 19-9). Adolescents spend more time with their peers than do children. Compared with children, their peer groups are more autonomous and are more likely to include members of the opposite sex. Because of the changes that have taken place within family systems in contemporary society, peer groups play a significant role in the socialization of adolescents.

Peers serve as credible sources of information, role models of new social behaviors, sources of social reinforcement, and bridges to alternative lifestyles. Close and supportive peer friendships have beneficial effects for young people (Fig. 19-10). However, adolescents with greater peer identification than parental identification, especially when peers model and support problem behaviors, are more prone to negative and health-compromising behaviors. Thus the transition to greater peer involvement, like other developmental transitions of adolescence, is a process requiring guidance; skills; and, optimally, a prolonged time to complete the transition. At a time when they are developing interpersonal skills to deal with peer pressure, young adolescents who lack adult supervision and opportunities for communication with adults may be more susceptible to peer influences and at a higher risk for poor peer-group selection than teenagers who have close relationships with caring adults.

The heightened value placed on adolescent peer relationships leads to questions about the quality and nature of peer influence. Rather than thinking of all peer influence as either good or bad, it is important to recognize that the influence of peers varies from one adolescent to another, from one peer group to another, and across different societies and cultures. Adolescents’ selection of peer groups seems to be most strongly influenced by sociodemographic factors and by common patterns of behavior, including, for example, substance use, school achievement, and religious participation. Peers can have either positive or negative effects on adolescent behavior. Negative effects include increased substance use, gang membership, and violent behaviors. Positive effects include an orientation supporting academic achievement, an environmental commitment, or a commitment to religious or social youth groups.

Peers can also be a positive force in health promotion. Same-age and older adolescents can encourage healthy behavior by serving as positive role models and promoting positive health norms in the peer group (Rosenfeld, Keenan, Fox, et al, 2000; Tuttle, Bidwell-Cerone, Campbell-Heider, et al, 2000). For most adolescents, prosocial pressures from peers are greater than antisocial ones, and adolescents are influenced more by prosocial or neutral pressures than by pressures toward misconduct.

Schools

In contemporary society, schools play an increasingly important role in preparing young people for adulthood. Schooling is essential for a successful future for both boys and girls. Failure to complete high school reduces employment opportunities and the probability of earning an adequate income. Yet many schools in the United States do not meet the developmental needs of all young people.