Health Promotion of the Toddler and Family

http://evolve.elsevier.com/wong/ncic

Attachment, Ch. 12

Childhood Injuries, Ch. 1

Dental Disorders, Ch. 18

Enuresis, Ch. 18

Family Influences on Child Health Promotion, Ch. 3

Fears, Ch. 15

Ingestion of Injurious Agents, Ch. 16

Injury Prevention: Infant, Ch. 12

Injury Prevention: Preschooler, Ch. 15

Limit Setting and Discipline, Ch. 3

Mammal Bites, Ch. 18

Sleep Problems, Ch. 12

Social, Cultural, and Religious Influences on Child Health Promotion, Ch. 2

Spiritual Development, Ch. 15

Promoting Optimum Growth and Development

The term terrible twos has often been used to describe the toddler years, the period from 12 to 36 months of age. It is a time of intense exploration of the environment as children attempt to find out how things work; what the word “no” means; and the power of temper tantrums, negativism, and obstinacy. “Getting into things” is their way of learning about their world, especially relationships. Successful mastery of the tasks of this age requires a strong foundation of trust during infancy and frequently necessitates guidance from others when parent and toddler face the struggles of toilet training, limit setting, and sibling rivalry. Nurses who understand the dynamics of growth and development of the toddler can help families deal effectively with the tasks of this age.

Biologic Development

Growth slows considerably during toddlerhood. The average weight at 2 years is 12 kg (26.5 lb). The average weight gain is 1.8 to 2.7 kg (4 to 6 lb) per year. By  years of age, toddlers have quadrupled their birth weight. The rate of increase in height also slows. The usual increment is an addition of 7.5 cm (3 inches) per year and occurs mainly in elongation of the legs rather than the trunk. The average height of a 2-year-old is 86.6 cm (34 inches). In general, adult height is about twice the child’s height at 2 years of age. Accurate measurement of height and weight during the toddler years should reveal a steady growth curve that is steplike rather than linear (straight), which is characteristic of the growth spurts during the early childhood years.

years of age, toddlers have quadrupled their birth weight. The rate of increase in height also slows. The usual increment is an addition of 7.5 cm (3 inches) per year and occurs mainly in elongation of the legs rather than the trunk. The average height of a 2-year-old is 86.6 cm (34 inches). In general, adult height is about twice the child’s height at 2 years of age. Accurate measurement of height and weight during the toddler years should reveal a steady growth curve that is steplike rather than linear (straight), which is characteristic of the growth spurts during the early childhood years.

The rate of increase in head circumference slows somewhat by the end of infancy, and head circumference is usually equal to chest circumference by 1 to 2 years of age. The usual total increase in head circumference during the second year is 2.5 cm (1 inch). Then the rate of increase slows until age 5 years, when the increase is less than 1.25 cm (0.5 inch) per year. The anterior fontanel closes between 12 and 18 months of age.

Chest circumference continues to increase and exceeds head circumference during the toddler years. Its shape also changes as the transverse (or lateral) diameter exceeds the anteroposterior diameter. After the second year the chest circumference exceeds the abdominal measurement, which, in addition to the growth of the lower extremities, gives the child a taller, leaner appearance. However, the toddler retains a squat, “pot-bellied” appearance because of the less well-developed abdominal musculature and short legs (Fig. 14-1). The legs retain a slightly bowed or curved appearance during the second year from the weight of the relatively large trunk.

Sensory Changes

Visual acuity of 20/40 is considered acceptable during the toddler years. Full binocular vision is well developed, and any evidence of persistent strabismus should receive professional attention as early as possible to prevent amblyopia. Depth perception continues to develop, but because of the child’s lack of motor coordination, falls from heights remain a persistent danger.

The senses of hearing, smell, taste, and touch become increasingly well developed, coordinated with each other, and associated with other experiences. Toddlers use all the senses to explore the environment. Toddlers visually inspect an object by turning it over; they may taste it, smell it, and touch it several times before they are satisfied with their investigation. They will shake it to see if it makes noise and vigorously test its durability.

Another example of the integrated function of the senses is the toddler’s development of specific taste and texture preferences. The child is much less likely than infants to try a new food because of its appearance or smell, not just its taste. Likewise a toddler is likely to reject a new food because of its texture. Nonsensory associations with objects also take on significance. For example, if parents refuse a particular food because of their dislike, they will transfer this negative connotation to the child before the child has had an opportunity to taste it. Awareness of these factors is important in several areas of childrearing, such as feeding, teaching socially acceptable habits, and reinforcing appropriate behavioral responses to various situations.

Touch continues to be important to the toddler. Descending development of the spinal tract is evidenced by increased sensation in the lower extremities, such as ticklish feet. Pleasant tactile sensations soothe and comfort the toddler, especially in times of stress or fatigue.

Maturation of Systems

Most of the physiologic systems are relatively mature by the end of toddlerhood. By the end of the first year, all the brain cells are present but continue to increase in size. Myelination of the spinal cord is almost complete by 2 years of age, which parallels the completion of most of the gross motor skills associated with locomotion. Brain growth is 75% completed by the end of 2 years.

Development of various areas of the brain seems to correspond with the child’s progressive intellectual capacity. As development progresses, specific changes take place in various areas of the cerebral cortex, such as the Broca area for speech and cortical areas for control of the legs, hands, feet, and sphincters. Because this neuromotor organization is so inclusive, complex, and intricate, the child is limited in the ability to attend to any one aspect of behavior for more than a few minutes.

Between 2 and 3 years of age, coordination and consolidation of these voluntary functions allow the toddler to listen better, look longer, and have an extended attention span. Although postural control is increasingly developed as myelination of the spinal cord advances, the immaturity of this control, combined with the child’s limited experiences and lack of visual perception, makes it difficult to do simple acts such as seating oneself in a chair or climbing down stairs.

Volume of the respiratory tract and growth of associated structures continue to increase during early childhood, lessening some of the factors that predisposed the child to frequent and serious infections during infancy. However, the internal structures of the ear and throat continue to be short and straight, and the lymphoid tissue of the tonsils and adenoids continues to be large. As a result, otitis media, tonsillitis, and upper respiratory tract infections are common. The respiratory and heart rates slow, and the blood pressure increases (see inside back cover). Respirations continue to be abdominal.

The digestive processes are fairly complete by the beginning of toddlerhood. The acidity of the gastric contents continues to increase and has a protective function because it destroys many types of bacteria. Stomach capacity increases to allow for the usual schedule of three small meals a day.

One of the more prominent changes of the gastrointestinal system is the voluntary control of elimination. With complete myelination of the spinal cord, the toddler gradually achieves control of anal and urethral sphincters. The physiologic ability to control the sphincters occurs somewhere between ages 18 and 24 months. Bladder capacity also increases considerably. By 14 to 18 months of age the child is able to retain urine for up to 2 hours or longer.

The skin functionally matures during early childhood. The epidermis and dermis are more tightly bound together, increasing their resistance to infection and irritation and creating a more effective barrier against fluid loss. Production of sebum is minimal, which contributes to the development of dry skin. The eccrine glands are functional during early childhood and react to changes in temperature, but they produce minimum amounts of sweat. Hair grows thicker and coarser and usually darkens and loses some curliness. Fine hair is evident on the lower arms and legs. Production of adipose tissue declines as hyperplasia of muscle cells increases. With the concurrent growth of the lower extremities, the child assumes more adultlike proportions.

Under conditions of moderate variation in temperature, the toddler rarely has the difficulties of the young infant in maintaining body temperature. The capillaries are able to conserve core body temperature by constricting in response to cold and dilating in response to heat. Shivering, an involuntary act that results in rhythmic muscle contraction, which increases cellular metabolism and produces heat, is much more effective as a source of thermogenesis. The child also learns mechanisms to control body temperature—putting on clothing when cold or removing it when warm.

The defense mechanisms of the tissues and blood, particularly phagocytosis, are much more efficient in the toddler than in the infant. The production of antibodies is well established. Immunoglobulin G, which neutralizes microbial toxins, reaches adult levels by the end of the second year of life. Passive immunity from maternal transfer during fetal life disappears by the beginning of toddlerhood. Immunoglobulin M, which responds to artificial immunizing techniques and combats serious infection, attains adult levels during late infancy. Immunoglobulins A, D, and E increase gradually, not reaching eventual adult levels until later childhood. Many young children demonstrate a sudden increase in colds and minor infections when entering daycare or preschool because of exposure to new antigens.

Gross and Fine Motor Development

The major gross motor skill during the toddler years is the development of locomotion. By 12 to 13 months of age toddlers walk alone, using a wide stance for extra balance; by age 18 months they try to run but fall easily. Between 2 and 3 years of age, refinement of the upright, biped position is evident in improved coordination and equilibrium. By age 2 years toddlers can walk up and down stairs, and by age  years they jump using both feet, stand on one foot for a second or two, and manage a few steps on tiptoe. By the end of the second year they stand on one foot, walk on tiptoe, and climb stairs with alternate footing.

years they jump using both feet, stand on one foot for a second or two, and manage a few steps on tiptoe. By the end of the second year they stand on one foot, walk on tiptoe, and climb stairs with alternate footing.

Fine motor development is demonstrated in increasingly skillful manual dexterity. Once toddlers achieve pincer grasp, usually at 9 to 10 months of age, they combine this skill with other developing sensory and cognitive abilities. For example, by age 12 months they are able to grasp a very small object. By age 15 months they can drop a pellet into a narrow-necked bottle. Casting or throwing objects and retrieving them become an almost obsessive activity at about 15 months. By 18 months of age they can throw a ball overhand without losing their balance.

Visual perception of geometric shapes is also evident at this time. At age 12 months children selectively look at a round hole in a special form board but are unable to insert a round object. By age 15 months they promptly place the round object in the hole, even if the board is revised or turned upside down. Spatial relations also are evident in their ability to build a tower with blocks: by age 18 months, a tower of three or four blocks; by age 24 months, a tower of six or seven blocks; and by age 30 months, a tower of eight blocks or more.

Fine motor skill and visual ability are demonstrated in toddlers’ progressive adeptness in manipulating a pencil or crayon. By age 15 months they scribble spontaneously, and by age 24 months they imitate a circular stroke and a vertical line. By the end of the toddler period, the child can copy a circle and imitate a cross.

Mastery of gross and fine motor skills is evident in all phases of the child’s activity, such as play, dressing, language comprehension, response to discipline, social interaction, and propensity for injuries. Activities occur less in isolation and more in conjunction with other physical and mental abilities to produce a purposeful result. For example, the toddler walks to reach a new location, releases a toy and picks it up again or chooses a new one, and scribbles to look at the image produced. The possibilities of the exploration, investigation, and manipulation mastery of the environment—and its hazards—are endless.

Psychosocial Development

Toddlers are faced with the mastery of several important tasks. If the need for basic trust has been satisfied, they are ready to give up dependence for control, independence, and autonomy. Some of the specific tasks include:

• Differentiation of self from others, particularly the mother or primary caregiver

• Toleration of separation from parents

• Ability to withstand delayed gratification

• Control over bodily functions

• Acquisition of socially acceptable behavior

• Verbal means of communication

• Ability to interact with others in a less egocentric manner

Mastery of these goals is only begun during late infancy and the toddler years, and such tasks as developing interpersonal relationships with others may not be completed until adolescence. However, crucial foundations for successful completion of such developmental tasks are laid during these early formative years.

Developing a Sense of Autonomy (Erikson)

According to Erikson (1963), the developmental task of toddlerhood is acquiring a sense of autonomy while overcoming a sense of doubt and shame. As infants gain trust in the predictability and reliability of their parents, environment, and interaction with others, they begin to discover that their behavior is their own and that it has a predictable, reliable effect on others. However, although they are aware of their will and control over others, they are confronted with the conflict of exerting autonomy and relinquishing the much enjoyed dependence on others. Exerting their will has definite negative consequences, whereas retaining dependent, submissive behavior is generally rewarded with affection and approval. On the other hand, continued dependency creates a sense of doubt regarding their potential capacity to control their actions. This doubt is compounded by a sense of shame for feeling this urge to revolt against others’ will and a fear that they will exceed their own capacity for manipulating the environment. The latter fear is a basis for instituting limit setting and consistent discipline at this age. Without appropriate limits on what is acceptable versus unacceptable behavior, children have no guidelines for establishing the end points of their ability to control.

Just as the infant has the social modalities of grasping and biting, the toddler has the newly gained modality of holding on and letting go. Holding on and letting go are evident in how the toddler uses the hands, mouth, eyes, and, eventually, sphincters when toilet training is begun. Children constantly express these social modalities in play activities such as casting or throwing objects; taking objects out of boxes, drawers, or cabinets; holding on tighter when someone says, “No, don’t touch”; and spitting out food as taste preferences become strong.

Several characteristics, especially negativism and ritualism, are typical of toddlers in their quest for autonomy. As toddlers attempt to express their will, they often act with negativism, giving a negative response to requests. The words “no” or “me do” can be the sole vocabulary. Toddlers express emotions strongly, usually in rapid mood swings. One minute toddlers can be engrossed in an activity, and the next minute they might be violently angry because they were unable to manipulate a toy or open a door. If scolded for doing something wrong, they can have a temper tantrum and almost instantaneously pull at the parent’s legs to be picked up and comforted. Understanding and coping with these swift changes is often difficult for parents. Many parents find the negativism exasperating and, instead of dealing constructively with it, give in to it, which further threatens the child’s search for acceptable methods of interacting with others (see p. 568).

In contrast to negativism, which frequently disrupts the environment, ritualism, the need to maintain sameness and reliability, provides a sense of comfort. Toddlers can venture out with security when they know that familiar people, places, and routines still exist. One can easily understand why change, such as hospitalization, represents such a threat to these children. Without the comfortable rituals, they have little opportunity to exert autonomy. Consequently, dependency and regression occur (see p. 569).

Erikson focuses on the development of the ego, which may be thought of as reason or common sense, during this phase of psychosocial development. The child struggles to deal with the impulses of the id, tolerate frustration, and learn socially acceptable ways of interacting with the environment. The ego becomes evident as the child is able to delay gratification.

This stage also sees a rudimentary beginning of the superego, or conscience, which is the incorporation of the morals of society and the process of acculturation. With the development of the ego, children further differentiate themselves from others and expand their sense of trust in self. But as they begin to develop awareness of their own will and capacity to achieve, they also become aware of their ability to fail. This ever-present awareness of potential failure creates doubt and shame. Successful mastery of the task of autonomy necessitates opportunities for self-mastery while withstanding the frustration of necessary limit setting and delayed gratification. Opportunities for self-mastery are present in appropriate play activities, toilet training, the crisis of sibling rivalry, and successful interactions with significant others.

Cognitive Development

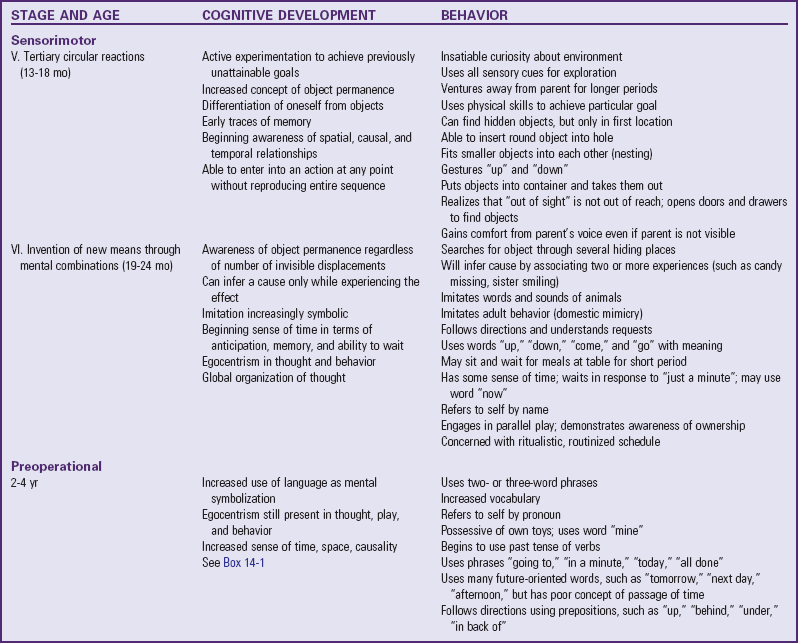

The period from 12 to 24 months of age is a continuation of the final two stages of the sensorimotor phase (Table 14-1). During this time the cognitive processes develop rapidly and at times seem similar to mature thinking. However, reasoning skills are still primitive and need to be understood to effectively deal with the typical behaviors of this age child. The main cognitive achievement of early childhood is the acquisition of language, which represents mental symbolism.

TABLE 14-1

SENSORIMOTOR AND PREOPERATIONAL PHASES DURING TODDLERHOOD*

*For the previous four stages during early infancy, see Table 12-1.

In the fifth stage, tertiary circular reactions (from 13 to 18 months of age), the child uses active experimentation to achieve previously unattainable goals. Newly acquired physical skills are increasingly important for the function they serve rather than for the acts themselves. The child incorporates the old learning of secondary circular reactions and applies the combined knowledge to new situations, with emphasis on the results of the experimentation. In this way there is the beginning of rational judgment and intellectual reasoning. During this stage the child further differentiates self from objects. This is evident in the child’s increasing ability to venture away from the parent and to tolerate longer periods of separation.

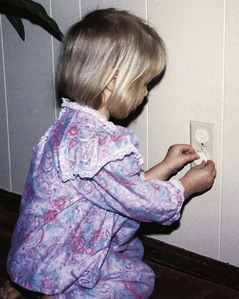

Awareness of a causal relationship between two events is apparent. After flipping a light switch, toddlers are aware that a response occurs. However, they are not able to transfer that knowledge to new situations. Therefore every time they see what appears to be a light switch, they must reinvestigate its function. Such behavior demonstrates the beginning of categorizing data into distinct classes, subclasses, and so on. Innumerable examples of this type of behavior occur as toddlers repeatedly explore the same object each time it appears in a new place. A classic example is their curiosity about electrical outlets. Even if they receive a shock from one of them, they will adamantly poke and inspect every other outlet. This inability to transfer information leaves toddlers particularly vulnerable to injuries. However, traces of memory are evident because they usually avoid the outlet where the shock occurred.

Because classification of objects is still basic, the appearance of an object indicates its function. For example, if the child’s toys are stored in a paper bag or large container, the toddler does not perceive a difference between that toy receptacle and the garbage pail or laundry basket. If allowed to turn over the toy receptacle, the child will just as quickly do the same to other similar objects because, in the child’s mind, there is no difference. Expecting toddlers to judge which receptacles are permissible to explore and which are not is inappropriate for this age-group. Instead, the forbidden object, such as the garbage pail, should be placed out of reach. This has significant implications for prevention of accidents and accidental ingestion of injurious agents.

The discovery of objects as objects leads to an awareness of their spatial relationships. Children are able to recognize different shapes and their relationship to each other. For example, they can fit slightly smaller boxes into each other (nesting) and can place a round object into a hole, even if the board is turned around, upside down, or reversed. However, they cannot do the same thing with a square until 2 years of age. Children are also aware of space and the relationship of their body to dimensions such as height. They will stretch, stand on a low stair or stool, and pull a string to reach an object.

Object permanence has also advanced. Although they still cannot find an object that has been displaced and is no longer visible or has been moved from under one pillow to another without their seeing the change, toddlers are increasingly aware of the existence of objects behind closed doors, in drawers, and under tables. Parents are usually acutely aware of this developmental achievement because they find high places and locked cabinets to be the only areas inaccessible to toddlers. Parents also experience toddlers’ protest behaviors when the parents leave because toddlers are aware that their parents are absent when they cannot see them.

During ages 19 to 24 months the child is in the final sensorimotor stage, invention of new means through mental combinations. This stage completes the more primitive, autistic thought processes of infancy and prepares the way for more complex mental operations during the phase of preoperational thought. One of the most dramatic achievements of this stage is in the area of object permanence. Children will now actively search for an object in several potential hiding places. In addition, they can infer a cause when only experiencing the effect. They can infer that an object was hidden in any number of places even if they only saw the original hiding place.

Imitation displays deeper meaning and understanding. Earlier, imitation was concrete and action oriented. For example, “bye-bye” was a behavioral response more than a conceptual gesture of departure. Now it has a broader meaning, such as Daddy is going to work, it is time for a walk, or something is no longer present. There is greater symbolization to imitation.

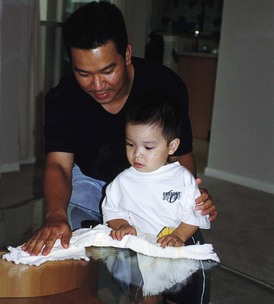

One type of symbolic imitation is domestic mimicry, the imitation of household activity. Toddlers are acutely aware of others’ actions and attempt to copy them in gestures and in words. They can imitate the parents’ performance of a household task both physically and verbally (Fig. 14-2). Parents often remark how accurately they see themselves when the child engages in domestic mimicry. Such activity is part of the child’s learning sex-role behavior. Identification with the parent of the same sex becomes apparent by the second year and represents the child’s intellectual ability to differentiate models of behavior and to imitate them appropriately.

The concept of time is still embryonic, but children have some sense of timing in terms of anticipation, memory, and the limited ability to wait. They may listen to the command, “Just a minute,” and behave appropriately. However, their sense of timing is exaggerated—1 minute can last an hour. Toddlers’ limited attention spans also indicate their sense of immediacy and concern for the present.

Egocentrism, or the inability to envision situations from perspectives other than one’s own, is evident in all aspects of toddlers’ behavior. They see, experience, and live every event in reference to themselves. A common example of egocentric behavior is the toddler who takes a toy away from another child. The toddler is concerned only with playing with the toy and is unable to conceptualize that taking the toy away will make the other child unhappy.

Preoperational Phase (Piaget)

At approximately 2 years of age the child enters the preconceptual phase of cognitive development, which lasts until about age 4 years. The preconceptual phase is a subdivision of the preoperational phase, which spans ages 2 to 7 years. The preconceptual phase is primarily one of transition that bridges the purely self-satisfying behavior of infancy and the undeveloped socialized behavior of latency. The principal characteristics of this stage are egocentric use of language and dependence on perception in problem solving.

From ages 2 to 4 years children learn a variety of words and increasingly use language. In fact, toddlers talk a lot. Speech is primarily of two types: egocentric or socialized. Egocentric speech consists of repeating words and sounds for the pleasure of hearing oneself and is not intended to communicate. This collective monologue reflects the child’s lingering self-centeredness.

Socialized speech is for communication; however, it is still egocentric in that children communicate about themselves to others. Before age 3 most speech is directed at self-fulfillment or self-reference, such as, “Want drink,” or “I do,” and is directed mostly toward adults. Because children think that everyone else’s world is the same as theirs, they expect others to understand their verbal messages even when limited information is conveyed.

Preoperational thinking implies that children cannot think in terms of operations—the ability to manipulate objects in relation to each other in a logical fashion. Rather, toddlers think primarily based on their perception of an event. Problem solving is based on what they see or hear directly rather than on what they recall about objects and events (Box 14-1).

Within the second year the child increasingly uses language symbolically and is concerned with the “why” and “how” of things. For example, a pencil is “something to write with” and food is “something to eat.” However, such mental symbolization is closely associated with prelogical reasoning. For instance, a needle is “something that hurts.” Such painful experiences take on new significance because memory is associated with the specific event and fears are likely to develop, such as resistance to people who wear uniform scrubs or rooms that look like the practitioner’s office. Sometimes parents and health care personnel underestimate the child’s ability to recall events and give little thought to preparation for visits to a practitioner’s office or other health facility, resulting in fears that can last a lifetime. Because of the vulnerability of these early years, it is essential to prepare children for new experiences, whether it is a new baby-sitter, a primary practitioner, or a visit to the dentist.

Moral Development: Preconventional or Premoral Level

Toddlers’ development of moral judgment is at the most basic level. They have little, if any, concern for why something is wrong. Kohlberg’s theory of moral development is influenced by Piaget’s theory of moral thought; the first phase of Kohlberg’s theory is called the preconventional phase, and it involves punishment and obedience. Young children behave in accordance with the freedom or restriction that is placed on actions. In the punishment and obedience orientation, whether an action is good or bad depends on whether it results in reward or punishment. If children are punished for it, the action is bad. If they are not punished, the action is good, regardless of the meaning of the act. For example, if parents allow hitting, the child will perceive that hitting is good because it is not associated with punishment. By the age of 36 months, developmental aspects of conscience may be present.

The type of discipline also affects children’s moral development. When parents use power to control behavior, such as physical punishment or withholding privileges, children receive a negative view of morals, especially toward authority figures, such as law enforcement officials. When parents withdraw love or attention, children behave primarily because of guilt, rather than from an internalization of morals. However, when parents give explanations for the misbehavior and try to help children change through positive approaches, such as consequences or rewards, children feel less hostility and are more likely to base their actions on an analysis of why an act may be wrong. Of course, the effect of discipline is not limited to the toddler years, and the sole use of explanation is inappropriate during this period. Because parents usually establish disciplinary techniques at this time, the use of constructive approaches should begin early. (See Limit Setting and Discipline, Chapter 3.)

Spiritual Development

Spiritual development in children is often discussed in terms of the child’s developmental level because the evolution of spirituality often parallels cognitive development (Elkins and Cavendish, 2004). The child’s family and environment strongly influence the child’s perception of the world around him or her, and this often includes spirituality. Furthermore, family values, beliefs, customs, and expressions of these will influence the child’s perception of his or her spiritual self (Elkins and Cavendish, 2004). The relationship between spirituality, illness in childhood, and nursing has been studied in the context of suffering, terminal illness such as cancer, and end-of-life care (McSherry, Kehoe, Carroll, et al, 2007; Bull and Gillies, 2007). In the past two decades there has been an increased interest in and focus on spiritual care in adults and children as further understanding of the influence of one’s spirituality on health, illness, and well-being has progressed.

Toddlers learn about God through the words and the actions of those closest to them. They have only a vague idea of God and religious teachings because of their immature cognitive processes; however, if God is spoken about with reverence, young children associate God with something special. During this period the designation of powerful religious symbols and images is strongly influenced by the manner in which they are presented; therein lies the potential for the development of guilt and fear or, conversely, love and companionship with religious symbols (Roehlkepartain, Benson, King, et al, 2006). Developmentally toddlers are unable to clearly distinguish between fantasy, make-believe, and factual representations; therefore the manner in which spiritual symbols and images are represented to them by the primary caretakers is extremely important in the ultimate development of the child’s sense of self and a higher power (Roehlkepartain, Benson, King, et al, 2006).

Toddlers begin to assimilate behaviors associated with the divine (e.g., folding hands in prayer). Routines such as saying prayers before meals or at bedtime can be important and comforting. Near the end of toddlerhood, when children use preoperational thought, there is some advancement of their understanding of God. Religious teachings, such as reward or fear of punishment (heaven or hell) and moral development (see Chapter 15), may influence their behavior (Fosarelli, 2003).

Development of Body Image

As in infancy, the development of body image closely parallels cognitive development. With increasing motor ability, toddlers recognize the usefulness of body parts and gradually learn their respective names. They also learn that certain body parts have various meanings; for example, during toilet training, the genitalia become significant and cleanliness is emphasized. By 2 years of age toddlers recognize gender differences and refer to self by name and then by pronoun. By age 3 years, toddlers have developed gender identity. Also by this time the child begins to remember events with reference to their personal significance, forming an autobiographic memory that helps establish a continuous identity throughout life’s events.

Once they begin preoperational thought, toddlers can use symbols to represent objects, but their thinking may lead to inaccuracies. For example, if someone who is pregnant is called “fat,” they will describe all “fat” ladies (sometimes even men!) as having babies. They have a beginning recognition of words used to describe physical appearance, such as “pretty,” “handsome,” or “big boy.” Such expressions eventually influence how children view their own bodies, and such labeling (negative or positive) becomes part of their body image.

Although little research has been done on body image development in young children, it is evident that body integrity is poorly understood and that intrusive experiences are threatening (Dahlquist, Busby, Slifer, et al, 2002). For example, toddlers forcefully resist procedures such as examining the ear or mouth and taking an axillary temperature. The procedure itself (e.g., taking vital signs) does not hurt the child, but it represents an intrusion into the child’s personal space, which elicits a strong protest. Toddlers also have unclear body boundaries and may associate nonviable parts, such as feces, with essential body parts. This can be seen in a toddler who is upset by flushing the toilet and watching the stool disappear.

Nurses can help parents foster a positive body image in their child by encouraging them to avoid negative labels, such as “skinny arms” or “chubby legs”; such self-perceptions are internalized and can last a lifetime. Body parts, especially those related to elimination and reproduction, should be called by their correct names. Respect for the body should be practiced.

Development of Gender Identity

Just as toddlers explore their environment, they also explore their bodies and find that touching certain body parts is pleasurable. Genital fondling (masturbation) can occur and involves manual stimulation, as well as posturing movements (especially in young girls) such as tightening of the thighs or mechanical pressure applied to the pubic or suprapubic area. Other demonstrations of pleasurable activities include rocking, swinging, and hugging people and toys. Parental reactions to toddlers’ sexual behavior influence the children’s own attitudes and should be accepting rather than critical. If such acts are performed in public, parents should not condone or bring attention to the behavior, but should teach the child that it is more acceptable to perform the behavior in private (Meyer, 2002).

Children in this age-group are learning vocabulary associated with anatomy, elimination, and reproduction. Certain associations between words and functions become significant and can influence future sexual attitudes. For example, if parents refer to the genitalia as dirty, especially in the context of elimination, this association between “genitalia” and “dirty” may be transferred to sexual functions. Sex-role differences become obvious to children and are evident in much of their imitative play. A sense of maleness or femaleness, or gender identity, is formed by age 3 years, and the child’s feelings about being male or female begin to form (Fonseca and Greydanus, 2007). Early attitudes are formed about affectionate behaviors between adults from observing parental and other adult sexual or sensual activities. (See also Sex Education, Chapter 15.) The quality of relationships with parents is important to the child’s capacity for sexual and emotional relationships later in life (DeLamater and Friedrich, 2002).

Social Development

A major task of the toddler period is differentiation of self from significant others, usually the mother. The differentiation process consists of two phases: separation, the children’s emergence from a symbiotic fusion with the mother; and individuation, those achievements that mark children’s assumption of their individual characteristics in the environment. Although the process begins during the latter half of infancy, the major achievements occur during the toddler years.

Toddlers have an increased understanding and awareness of object permanence and some ability to withstand delayed gratification and tolerate moderate frustration. They begin to lose some of their resistance to separation yet appear even more concerned about the parent’s whereabouts. They have learned from experience that parents exist when physically absent. Repetition of events such as going to bed without the parents but waking to find them again reinforces the reliability of such brief separations. Consequently, toddlers are able to venture away from their parents for brief periods because of the security of knowing that the parents will be there when they return. Verbal and visual reassurance from the parent gradually replaces some of the previous need to be physically close for comfort.

Toddlers also show less fear of strangers, but only when their parents are present. When left alone with a stranger, they are fearful and acutely anxious; manifest depressive behavior, such as crying and withdrawal; and may become restless, hyperactive, or passive, reverting to regressive behaviors. Such reactions may be evident when a child is left with a baby-sitter; is beginning kindergarten, preschool, or daycare; or is hospitalized. (See Chapter 26.)

These behaviors are not pathologic or harmful if parents realize how desperately their children need them. Indiscriminate friendliness toward strangers and lack of anxiety during separation from parents may be reasons for concern. Sensitive, perceptive parents will be aware of the child’s need for increased love, affection, and attention when they are together. An attitude such as “They will get used to the baby-sitter” will not help young children positively tolerate separation.

According to Harpaz-Rotem and Bergman (2006), the separation-individuation phase encompasses the phenomenon of rapprochement; as the toddler separates from the mother and begins to make sense of experiences in the environment, the child is drawn back to the mother for assistance in verbally articulating the meaning of the experiences. Developmentally the term rapprochement means the child moves away and returns for reassurance. If the mother’s response to the toddler is inappropriate, the toddler may experience insecurity and confusion.

Parents often need help in realizing the necessity of preparing children for an inevitable separation. Particularly with the firstborn, parents tend to overprotect children, shield them from any anxiety-producing experience, and insulate them from less than immediate gratification. Although this is not necessarily harmful, especially if opportunities for independence are allowed later, it does not prepare children for unexpected events. A typical example is the birth of a sibling. The child is faced with the crisis of sibling rivalry and separation from the parent. Allowing children to experience brief periods of separation during early infancy prepares them for such experiences later. Indeed, they may still manifest the typical behaviors of protest, but they will also have learned that their mother or father always returns. Therefore it is easy to appreciate the tremendous loss that the death of a parent represents for young children; unlike their other experiences with separation, this time the parent will not return.

Transitional objects, such as a favorite blanket or toy, provide security for young children, especially when they are separated from parents, are dealing with a new stress, or are just fatigued (Fig. 14-3). Security objects often become so important to toddlers that they refuse to let them be taken away. Such behavior is normal; there is no need to discourage this tendency. During separations, such as daycare, hospitalization, or even overnight stays with a relative, transitional objects should be provided to minimize any feelings of fear or loneliness.

Fig. 14-3 Transitional objects, such as a warm and fuzzy stuffed animal, are sources of security to a toddler.

Learning to tolerate and master brief periods of separation are important developmental tasks of children in this age-group. In addition, it is a necessary component of parenting because brief periods of separation from their children allow parents to recoup their energy and patience and to avoid directing their irritations and frustrations at the children.

Language Development

The most striking characteristic of language development during early childhood is the increasing level of comprehension. Although the number of words acquired—from about 4 at 1 year of age to approximately 300 at age 2 years—is notable, the ability to understand speech is much greater than the number of words the child can say. Bilingual children can also achieve their early linguistic milestones in each language at the same time and produce a substantial number of semantically corresponding words in each of their two languages from the first words or signs (Petitto, Katerlos, Levy, et al, 2001).

At age 1 year the child uses one-word sentences, or holophrases. The word “up” can mean “pick me up” or “look up there.” For the child the one word conveys the meaning of a sentence, but to others it may mean many things or nothing. At this age about 25% of the vocalizations are intelligible. By the age of 2 years the child uses multiword sentences by stringing together two or three words, such as the phrases, “mama go bye-bye” or “all gone,” and approximately 65% of the speech is understandable. At 30 months the toddler knows her or his full name. By 3 years the child puts words together into simple sentences, begins to master grammatical rules, acquires five or six new words daily, knows his or her age and gender, and can count three objects correctly (Feigelman, 2007). Looking at books during this period provides an ideal setting for further language development (Feigelman, 2007). Authorities have evaluated the impact of television viewing on toddler language development and found that those who started watching television at less than 12 months and who watched longer than 2 hours per day had significant language delays (Chonchaiva and Pruksananonda, 2008). Adult-child conversations with infants and toddlers have been shown to positively affect language development; the researchers recommend reading, storytelling, and interactive adult-child communication (Zimmerman, Gilkerson, Richards, et al, 2009).

Gestures (such as putting phone to ear or pointing) precede or accompany each of the language milestones up to 30 months of age. Once language is sufficiently mastered, gestures phase out and the pace of word learning increases (Bates and Dick, 2002).

Personal-Social Behavior

One of the most dramatic aspects of development in the toddler is personal-social interaction. Parents frequently wonder why their manageable, docile, lovable infant has turned into a determined, strong-willed, volatile-tempered little “tyrant.” In addition, the tyrant can swiftly and unpredictably revert back to the adorable infant. All this is part of growing up and is evident in such areas as dressing, feeding, playing, and establishing self-control.

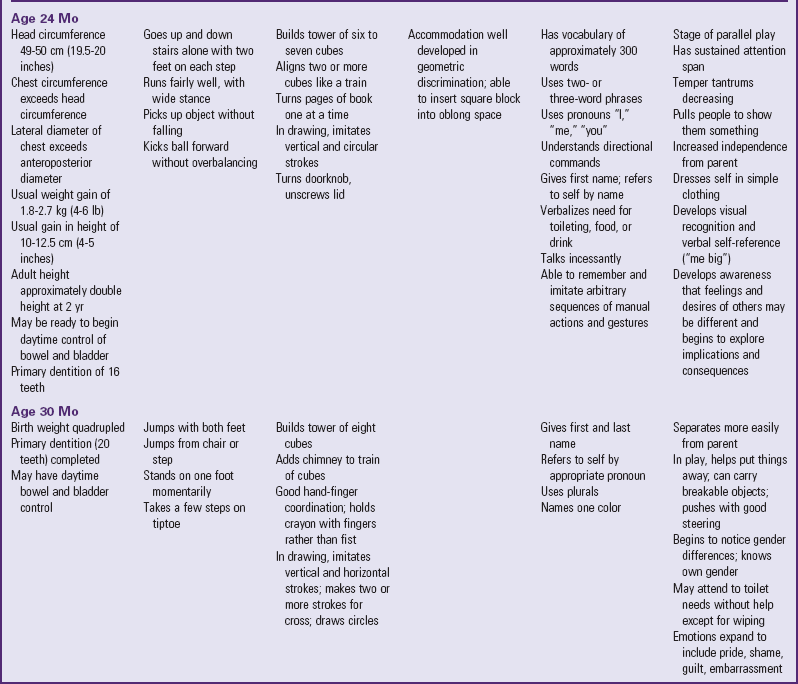

Toddlers are developing skills of independence, which are evident in all areas of behavior. By age 15 months children feed themselves, drink well from a covered cup, and manage a spoon, with considerable spilling. By age 24 months they use a spoon well, and by age 36 months they may be using a fork. Between ages 2 and 3 years they eat with the family and like to help with chores such as setting the table or removing dishes from the dishwasher, but they lack table manners and may find it difficult to sit through the family’s entire meal (see Table 14-3).

In dressing, toddlers also demonstrate strides in independence. The 15-month-old child helps by putting the arm or foot out for dressing and pulls shoes and socks off. The 18-month-old child removes gloves, helps with pullover shirts, and may be able to unzip. By age 2 years the toddler removes most articles of clothing and puts on socks, shoes, and pants without regard for right or left and back or front. Toddlers still need help to fasten clothes.

Toddlers also begin to develop concern for the feelings of others and develop an understanding of how adult expectations for behavior apply to specific situations (e.g., causing a sibling to cry while playing rough). As their understanding increases, they develop control. Age-appropriate discipline contributes to healthy social and emotional development. Positive reinforcement, redirection, and time-out are appropriate for most toddlers. It is recognized that social and emotional problems can develop in the youngest children. Early screening and intervention promote more positive outcomes as the young child grows and develops.

Play

Play magnifies toddlers’ physical and psychosocial development. Interaction with people becomes increasingly important. The solitary play of infancy progresses to parallel play—the toddler plays alongside, not with, other children. Although sensorimotor play is still prominent, there is much less emphasis on the exclusive use of one sensory modality. The toddler inspects the toy, talks to the toy, tests its strength and durability, and invents several uses for it.

Play assumes many forms and serves several functions. Toddlers benefit from a wide variety of play interactions (alone, with other children, with adults), environments (own home, other children’s homes, park), and activities (active, quiet, organized, unstructured).

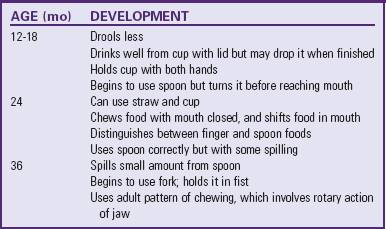

Imitation is one of the most distinguishing characteristics of play and enriches children’s opportunity to engage in fantasy. With less emphasis on sex-stereotyped toys, play objects such as dolls, carriages, dollhouses, dishes, cooking utensils, child-sized furniture, trucks, and dress-up clothes are used by both sexes; however, boys may be more interested than girls in activities related to trucks, trailers, cars, miniature plastic soldiers or superheroes, and building blocks, whereas girls may prefer doll-related activities (Fig. 14-4).

Increased locomotive skills make push-pull toys; stick horses; straddle trucks or cycles; a small, low gym and slide; variously sized balls; and rocking horses appropriate for the energetic toddler. Finger paints, thick crayons, chalk, chalkboard, paper, and puzzles with large, simple pieces use the child’s developing fine motor skills. Interlocking blocks in varied sizes (but large enough to avoid aspiration) and shapes provide hours of fun and, during later years, are useful objects for creative and imaginative play. The most educational toy is the one that fosters the interaction of an adult with a child in supportive, unconditional play. Parents and other providers are encouraged to allow children to play with a variety of simple toys that foster creative thinking (such as blocks, dolls, and clay), rather than passive toys that the child observes (battery-operated or mechanical). Active play time should also be encouraged over the use of computer or video games, which are more passive (Ginsburg and American Academy of Pediatrics, 2007). Toys are never substitutes for the attention of devoted caregivers, but toys can enhance these interactions (Glassy, Romano, and Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care, 2003).

Certain aspects of play are related to emerging linguistic abilities. Talking is a form of play for toddlers who enjoy musical toys such as age-appropriate cassette players, talking dolls and animals, and toy telephones. Appropriate children’s television programs are excellent for children in this age-group, who learn to associate words with visual images. However, parents should limit total media time to 1 to 2 hours of high-quality programming per day (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2001). Toddlers also enjoy “reading” stories from a picture book and imitating the sounds of animals.

Tactile play is also important for the exploring toddler. Water toys, a sandbox with pail and shovel, finger paints, soap bubbles, and clay provide excellent opportunities for creative and manipulative recreation. Adults sometimes forget the fascination of feeling slippery textures such as mud, catching airy bubbles, squeezing and reshaping clay, or smearing paints. These types of unstructured activities are as important as educational play to allow children freedom of expression.

Toys

Toys are the inanimate objects with which children interact, and cognitive development appears to be related to the variety and accessibility of objects for children to explore, experiment with, and come to know. Access to playthings, particularly during the earlier years, correlates with the accessibility of caregivers who make objects available, react to children’s responses to the objects, encourage further exploration, and talk about what is happening. Consequently, although they can be significant in themselves, playthings assume an especially important aspect as a medium of social interchange.

Selecting Toys

The type of toys chosen by and provided for children can facilitate learning and development in the areas just described. Toys that are small replicas of the culture and its tools help children assimilate their culture and learn gender and occupational roles. Toys that require pushing, pulling, rolling, and manipulating teach children about the physical properties of the items and help develop muscles and coordination. Such toys also allow toddlers to use newly developed fine and gross motor skills; children can push, pull and bang away on such objects and release frustration rather than acting out with inappropriate behavior. Toddlers can learn rules and the basic elements of cooperation and organization through board games.

Because they can be employed in a variety of ways, raw materials or multidimensional toys are best for enhancing skills and stimulating the imagination. Through manipulation, playthings such as boxes, clay, and blocks can assume a multitude of symbolic forms and inspire creative impulses. For example, building blocks can be used to construct a variety of structures, to count, and to learn shapes and sizes. “Educational” toys such as puzzles are less flexible. Families can encourage children’s toy play in a number of ways.

Play materials do not need to be expensive or elaborate. Infants and small children get enjoyment from simple kitchen utensils such as wooden spoons and small plastic plates to bang, pot lids to clang together, and a nest of measuring spoons to rattle. Empty cartons, especially oversized ones used to ship furniture, can assume the function of clubrooms, hideaways, and other private places. For older toddlers, a mound of dirt can become a place for rolling toy cars and balls and digging holes during summer and a place for sliding in winter. Paper is a fascinating and versatile raw material for children of any age, and most books on toy materials include recipes for play dough and finger paint.

Toy Safety

The selection of toys and play equipment is a joint effort between parents and children, but evaluating their safety is the adult’s responsibility. Government agencies do not inspect and police all toys on the market. Therefore adults who purchase play equipment, supervise purchases, or allow children to use play equipment need to evaluate its safety, including toys that are gifts or those that are purchased by the children themselves. Adults should also be alert to notices of defective toys and manufacturer recalls. Parents and health care workers can obtain information on a variety of recalled products and can report potentially dangerous toys and child products to the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission* or, in Canada, the Canadian Toy Testing Council.† Printable tips on toy safety are also available from Safe Kids Worldwide (www.safekids.org).

Temperament

Temperamental characteristics of children during infancy tend to predominate during toddlerhood. Most difficult infants remain difficult during early childhood, but the easy infants also become less easy. Parents often perceive toddlers as more challenging, especially considering the typical negativistic traits of this age-group. Parents of easy infants may be particularly distressed by the behavior change, whereas parents of difficult children may be more prepared, because of a previously troublesome year, or be overwhelmed by the additional behaviors. The use of the Toddler Temperament Scale can assist in identifying temperamental characteristics that benefit from individualized approaches to childrearing (Stein, Carey, and Snyder, 2004). The Toddler Behavior Assessment Questionnaire has also proved to be a reliable assessment of toddler temperament and behaviors. For practitioners in a busy setting, asking parents about their impression of the child’s temperament can help professionals understand the parent-child interactional process.

Stein, Carey, and Snyder (2004) emphasize that an important step in the clinical management of a child with a difficult or adverse temperament is to help the parents understand and cope with the child’s behavior. The authors suggest that the recognition and discussion of temperament often elicits a positive response in the parent. Parents are often concerned that their child with an adverse temperament will develop a behavioral dysfunction that persists for a lifetime. The lack of fit between the child’s temperament and the parents’ expectations is often a source of conflict that may escalate if providers do not intervene (Stein, Carey, and Snyder, 2004). These authors point out that behavioral problems in children can be managed appropriately, but the child’s temperament cannot be changed.

Although temper tantrums are common in toddlers, certain temperament characteristics make some children more prone to such outbursts. Active, intensely responding children are apt to yell, scream, and fling items during tantrums. Discipline is also influenced by temperament. Easy children generally respond well to mild forms of discipline, including a stern voice and sustained eye contact. However, difficult children often need more structured types of discipline, such as time-out, physical containment, or rewards, and the effectiveness of one approach may be short lived. Efforts at preventing misbehavior are especially important with children who have persistent natures. (See Limit Setting and Discipline, Chapter 3.) Without “friendly warnings” such children often have difficulty terminating an activity. These children may be punished for behavior that is merely typical of their temperament, and if the unwarranted punishment continues, the pattern can develop into a behavior problem. Slow-to-warm-up children may also present challenges, especially when this characteristic is combined with the toddler’s usual fear of strangers. These children require gradual introduction to new situations, such as daycare and baby-sitters.

Coping with Concerns Related to Normal Growth and Development

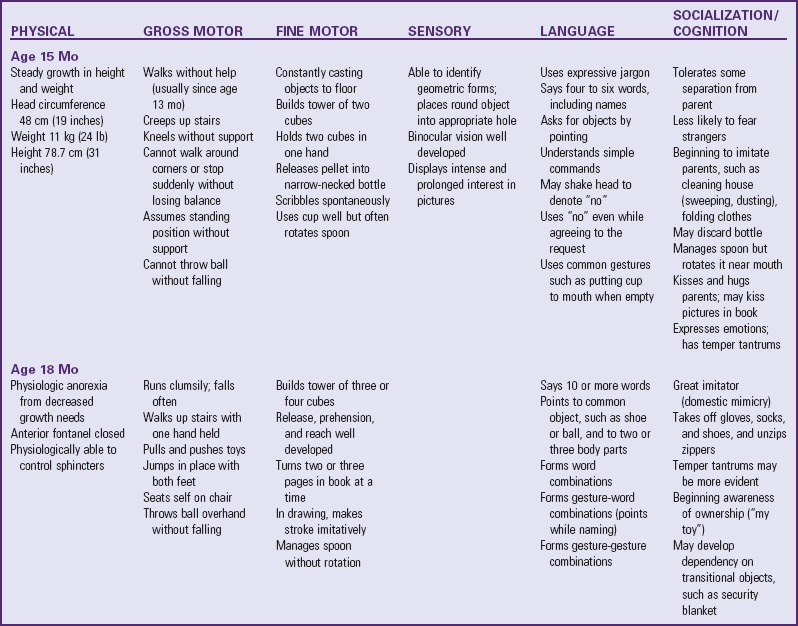

Table 14-2 summarizes the major features of growth and development for the age-groups of 15, 18, 24, and 30 months. The key developmental ages are 18 and 24 months, although the chronologic ages of 15 and 30 months are also significant. Fifteen months of age is a particularly integrative period of developmental achievement because it represents the completion or fruition of many skills that were unperfected at 1 year of age.

Toilet Training

![]() One of the major tasks of toddlerhood is toilet training. Voluntary control of the anal and urethral sphincters is achieved sometime after the child is walking, probably between ages 18 and 24 months. However, complex psychophysiologic factors are required for readiness. The child must be able to recognize the urge to let go and hold on and be able to communicate this sensation to the parent. In addition, the child may require some motivation in the desire to please the parent by holding on, rather than pleasing oneself by letting go.

One of the major tasks of toddlerhood is toilet training. Voluntary control of the anal and urethral sphincters is achieved sometime after the child is walking, probably between ages 18 and 24 months. However, complex psychophysiologic factors are required for readiness. The child must be able to recognize the urge to let go and hold on and be able to communicate this sensation to the parent. In addition, the child may require some motivation in the desire to please the parent by holding on, rather than pleasing oneself by letting go.

![]() Case Study—Toilet Training/Toddler Development

Case Study—Toilet Training/Toddler Development

Schmitt (2004) notes that comparative studies over the past five decades indicate that children in the 1990s in the United States were toilet trained at a later age (18 months in the 1960s versus 36 months in the 1990s). One possible contributing factor is the availability and convenience of disposable diapers. Another study showed that the child’s average age at initiation of toilet training was 20.6 months (Horn, Brenner, Rao, et al, 2006).

Five markers signal a child’s readiness to toilet train: bladder readiness, bowel readiness, cognitive readiness, motor readiness, and psychologic readiness (Schmitt, 2004). According to some experts, physiologic and psychologic readiness is not complete until ages 22 to 30 months (Schum, Kolb, McAuliffe, et al, 2002). Choby and George (2008) suggest that the mastery of skills required for training are not present before 24 months of age and that there is no benefit to intensive training before 27 months of age. However, Schmitt (2004) emphasizes that parents should begin preparing the child for toilet training earlier than 30 months. By this time the child has mastered the majority of essential gross motor skills, can communicate intelligibly, is in less conflict with parents in terms of self-assertion and negativism, and is aware of the ability to control the body and please the parent. There is no universal right age to begin toilet training or an absolute deadline to complete training. One of the nurse’s most important responsibilities is to help parents identify the readiness signs in their child (see Nursing Care Guidelines box).* On average, girls are developmentally ready to begin toilet training 2 to  months before boys (Schum, Kolb, McAuliffe, et al, 2002).

months before boys (Schum, Kolb, McAuliffe, et al, 2002).

Nighttime bladder control normally takes several months to years after daytime training. This is because the sleep cycle needs to mature so the child can awaken in time to urinate. Few children have night wetting episodes after achieving daytime dryness. However, those children who do not have nighttime dryness by the age of 6 years are likely to require intervention (Mercer, 2003).

Bowel training is usually accomplished before bladder training because of its greater regularity and predictability. The sensation for defecation is stronger than that for urination and easier for the child to recognize. A well-balanced diet that includes dietary fiber helps keep stool soft and supports the development and maintenance of regular bowel movements.

A number of techniques are helpful when initiating training, and cultural differences should be considered (see Cultural Competence box). In the United States some of the options recommended by practitioners include the Brazelton child-oriented approach, the American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines (which are similar to Brazelton method), Dr. Spock’s training method, and the intensive “toilet-training-in-a-day” (operant conditioning) approach by Azrin and Foxx (Choby and George, 2008). An extensive study and review by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality in 2006 (Klassen, Kiddoo, Lang, et al, 2006) concluded that the child-oriented method and the Azrin and Foxx methods were effective at toilet training healthy children (Choby and George, 2008). The following discussion of toilet training methods includes suggestions from the child-oriented approach.

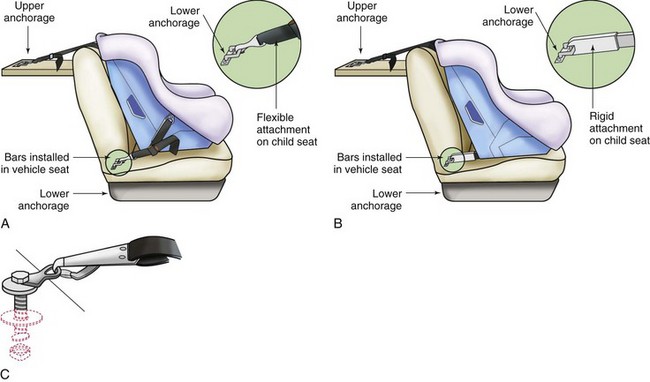

Parents should begin the readiness phase of toilet training by teaching the child about how the body functions in relation to voiding and having a stool. Schmitt (2004) suggests that parents talk about how adults and animals perform such functions on a routine basis. Another suggestion is to make toilet training as easy and simple as possible. Important considerations are the selection of the child’s clothing and the potty chair or use of the toilet. A freestanding potty chair allows children a feeling of security (Fig. 14-5, A). Planting the feet firmly on the floor also facilitates defecation. Another option is a portable seat attached to the regular toilet, which may ease the transition from potty chair to regular toilet. Placing a small bench under the feet helps stabilize the child’s position. It is probably best to keep the potty in the bathroom and to let the child observe the excreta being flushed down the toilet to associate these activities with usual practices. If a potty chair is not available, having the child sit facing the toilet tank provides added support (Fig. 14-5, B). Practice sessions should be limited to 5 to 8 minutes, and a parent should stay with the child, practicing sanitary habits after every session. Parents should praise children for cooperative behavior and successful evacuation. Dressing children in easily removed clothing; using training pants, “pull-on” diapers, or panties; and encouraging imitation by watching others are other helpful suggestions.

Fig. 14-5 A, Children may begin toilet training sitting on a small toilet. B, Sitting in reverse fashion on a regular toilet provides additional security to a young child.

When the child begins to show regular daytime dryness, parents may experiment with underwear during the day. Daytime accidents are common, particularly during periods of intense activity. Recognizing the child’s facial expressions when the need to urinate or defecate and suggesting a practice run to the potty is helpful. Young children become so engrossed in play activity that if they are not reminded, they will wait until it is too late to reach the bathroom. Therefore frequent reminders and trips to the toilet are necessary.

As the child develops each step of toileting (discussion, undressing, going, wiping, dressing, flushing, and hand washing), he or she gains a sense of accomplishment that parents should reinforce. If the parent-child relationship becomes strained, both may need a break to focus on enjoyable activities together. Regression may coincide with a stressful family situation or occur if the child is being pushed too hard and too fast. Regression is a normal part of toilet training and does not mean failure but should be viewed as a temporary setback to a more comfortable place for the child.

Daycare providers also play a role in the support and education of parents regarding toilet training practices. It is important for parents to inform all caregivers of their individual family values and the child’s specific needs when planning for training away from home. Ensuring consistency in care of the toddler and ensuring healthy practices in a sanitary environment allow for safe and effective toilet practices in all settings.

Sibling Rivalry

The term sibling rivalry refers to the natural jealousy and resentment of children to a new child in the family. It typically involves the arrival of a new infant but may be associated with anyone who joins the family. A common example is the merging of stepfamilies (blended families). However, the following discussion focuses on the sibling’s response to the birth of a newborn.

Toddlers do not hate or resent the infant but do resent the changes that this additional sibling brings, especially the separation from the mother during the birth. The parents now share their love and attention with someone else, the usual routine is disrupted, and toddlers may lose their crib or room—all at a time when they thought they were in control of their world. Sibling rivalry tends to be most pronounced in the firstborn, who experiences “dethronement” (loss of sole parental attention). It also seems to be most difficult for young children, particularly in terms of mother-child interaction.

Preparation of children for the birth of a sibling is individual, but age dictates some important considerations. Time is a vague concept for toddlers. A good time to start talking about the new baby is when toddlers become aware of the pregnancy and the changes occurring in the home in anticipation of the new member. Jealousy can develop from feeling left out; because fantasy dictates reality, fear of the unknown can lead to fear of abandonment, separation anxiety, and insecurity. To avoid additional stresses when the newborn arrives, parents should perform anticipated changes, such as moving the toddler to a different room or bed, well in advance of the birth.

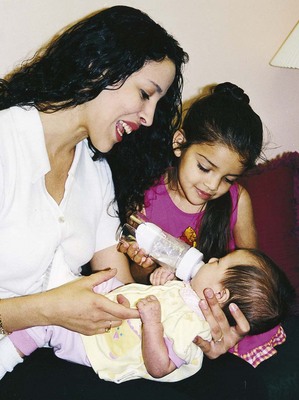

Toddlers need to have a realistic idea of what the newborn will be like. Telling them that a new playmate will come home soon sets up unrealistic expectations. Rather, parents should stress the activities that will take place when the baby arrives home, such as diapering, bottle- or breast-feeding, bathing, and dressing. At the same time, parents should emphasize which routines will stay the same, such as reading stories or going to the park. If toddlers have had no contact with an infant, it is a good idea to introduce them to one, if feasible. Providing a doll on which toddlers can imitate parental behaviors is another excellent strategy. They can tend to the doll’s needs (diapering, feeding) at the same time the parent is performing similar activities for the infant, then progress to helping with the sibling (Fig. 14-6).

Fig. 14-6 To minimize sibling rivalry, parents should include the toddler during caregiving activities.

When the newborn arrives, toddlers keenly feel the changed focus of attention. Visitors may initiate problems when they inadvertently shower the infant with attention and presents while neglecting the older child. Parents can minimize this by alerting visitors to the toddler’s needs, having small presents on hand for the toddler, and including the child in the visit as much as possible. The toddler can also help with the care of the newborn by getting diapers and doing other small tasks. It is important to involve toddlers in their new sibling’s care, since even young infants learn to respond to the sounds of their siblings’ voices.

How children exhibit jealousy is complex. Some openly hit the infant, push the child off the mother’s lap, or pull the bottle or breast from the infant’s mouth. More often the expressions of hostility and resentment are more subtle and covert. Toddlers may verbally express a wish that the infant “go back inside Mommy,” or they will revert to more infantile forms of behavior, such as demanding a bottle, soiling their diaper, clinging for attention, using baby talk, or aggressively acting out toward others. The latter is particularly common in preschoolers, who may seem to accept the new sibling at home but behave poorly in daycare or preschool. This is a form of displacement that says, “I can’t let my parents know how I feel, so I will tell you.” Encouraging parents to explore how their older child is acting with other caregivers is an important aspect of intervention.

Regardless of how well adjusted and accepting toddlers or preschoolers appear, infants must be protected by supervising the interaction between siblings. Other safety considerations are “baby proofing” the house and instructing children regarding the dangers to infants of small, sharp, or pointed objects. Parents should keep crib rails fully raised and the mattress lowered to discourage toddlers from picking up the infant. Infant seats or bassinets should be on the floor so that young children cannot pull them off a raised surface to see or play with the baby.

The first few weeks at home with a newborn and toddler can be challenging for parents. Assuring them that this period will pass, that the toddler will learn to accept the changes in lifestyle, and that the newborn will sleep through the night is part of the intervention. Allowing parents to talk about their feelings of ambivalence and frustration and suggesting ways of dealing with the sibling jealousy help all members of the family with this experience. Indeed, sibling rivalry is so common, regardless of the children’s ages, that it is a part of family life. Suggestions such as spending time with each child, letting children settle their arguments, and accepting angry feelings while teaching children appropriate ways to express hostility are general guidelines for dealing with the eventual conflicts between brothers and sisters.

Temper Tantrums

Toddlers may assert their independence by violently objecting to discipline. They may lie down on the floor, kick their feet, and scream as loud as possible. Some have learned the effectiveness of holding their breath until the parent relents. Although holding one’s breath may cause fainting from lack of oxygen, the accumulation of carbon dioxide will stimulate the respiratory control center, resulting in no physical harm. Tantrums are an indication of the child’s inability to control emotions; toddlers are particularly prone to tantrums because their strong drive for mastery and autonomy is frustrated by adult figures or lack of motor and cognitive skills. Potegal, Kosorok, and Davidson (2003) analyzed temper tantrums and suggest that they are a result of two emotional and behavioral processes: anger and distress. Anger increases rapidly and peaks near the beginning of the tantrum; components of distress, such as crying and comfort seeking, increase as anger subsides. Three fourths of the temper tantrums observed in the study lasted 5 minutes or less.

The best approach toward tapering temper tantrums requires consistency and developmentally appropriate expectations and rewards. Ensuring consistency among all caregivers in expectations, prioritizing what rules are important, and developing consequences that are reasonable for the child’s level of development help manage the behavior. For example, a popular time for a tantrum is before bed. Active toddlers often have trouble slowing down and, when placed in bed, resist staying there. Parents can reinforce consistency and expectations by stating, “After this story it is bedtime.” Starting at 18 months, time-outs work well for managing temper tantrums.

During tantrums ignore the behavior, provided the behavior is not injurious to the child, such as violently banging the head on the floor. Continue to be present to provide a feeling of control and security to the child once the tantrum has subsided. At this time a toy or a favorite activity can be substituted for the request. (See also Limit Setting and Discipline, Chapter 3.) During periods of no tantrums, practice developmentally appropriate positive reinforcement.

Other suggestions for handling tantrums include (Needlman, Howard, and Zuckerman, 1995):

• Offering the child options instead of an “all or none” position

• Picking one’s battles carefully and ignoring small skirmishes over unimportant issues

• Giving comfort once the child is able to control emotions but not giving in to the original request

• Praising the child for positive behavior when he or she is not having a tantrum

Temper tantrums are common during the toddler years and essentially represent normal developmental behaviors. However, temper tantrums can be signs of serious problems. Nurses should be alert to situations that require further evaluation (see Nursing Care Guidelines box).*

Negativism

One of the more difficult aspects of rearing toddlers is related to their persistent negative response to every request. The negativism is not an expression of being stubborn or disrespectful, but a necessary assertion of control. One method of dealing with negativism is by reducing the opportunities for a “no” answer. Asking the child, “Do you want to go to sleep now?” is almost certain to be met with an emphatic “no.” A more appropriate approach is to tell the child when it will be time to go to sleep (preferably within a specific time frame, such as “after reading a story”) and proceed accordingly.

In their attempt to exert control, children like to make choices. When confronted with appropriate choices, such as “You can have a peanut butter–and-jelly sandwich or chicken noodle soup for lunch,” they are more likely to choose one than to automatically say no. However, if their response is negative, parents should make the choice for the child. This behavior is frustrating for both the child and the parent. Parents need to respond in a calm, reassuring manner. Many of the suggestions for preventing misbehavior in Chapter 3 also help minimize negativism.

Stress

Adults rarely think of young children as being exposed to stress or suffering its consequences. However, the normal demands of growing up coupled with the usual pressures most families experience mean that few, if any, young children grow up stress free. Small amounts of stress are beneficial during the early years to help children develop effective coping skills. However, excessive stress is destructive, and young children are especially vulnerable because of their limited ability to cope.

To deal with stress in their children’s lives, parents must be aware of the signs of stress and be able to identify the source. The normal stresses of toddlerhood are listed in Box 14-2. Any number of other stresses may be imposed on children, such as alternative caregiving arrangements, birth of a sibling, separation and divorce, relocation, or illness. Watching children at play can help identify stressors. For example, one child was seen pounding on a doll, yelling “Go away! Go away!” The parent was quick to observe that the child’s recent irritability was probably caused by the stress of a new sibling. Other signs of increased stress in a toddler’s life may include increased thumb sucking, aggressive behavior, and biting.

The best approach to dealing with stress is prevention—monitoring the amount of stress in children’s lives so that levels do not exceed their coping ability. In many instances this is as simple as increasing the child’s rest periods to allow for quiet recovery time. Often it involves adequately preparing the child for change, such as daycare or a new sibling. It also requires helping the child cope with stress. Unsupervised play is an excellent vehicle for releasing anger or frustration, and toys such as drums, play nails and hammer, clay, and play dough provide alternative methods of dissipating anxiety. They also begin to teach socially acceptable ways of dealing with such feelings. Another approach is the use of relaxation and imagery. Even young children can learn to “let their bodies go limp like a rag doll” or “imagine floating on a cloud.”

Regression is a retreat from a present pattern of functioning to past levels of behavior. It usually occurs in instances of stress, when one attempts to cope by reverting to patterns of behavior that were successful in earlier stages of development. Regression is common in toddlers because almost any additional stress lessens their ability to master present developmental tasks. Any threat to their autonomy, such as illness, hospitalization, separation, or adjustment to a sibling, represents a need to revert to earlier forms of behavior, such as increased dependency. This can include refusal to use the potty chair; temper tantrums; demand for the bottle or crib; and loss of newly learned motor, language, social, and cognitive skills.

At first, such regression appears acceptable and comfortable for children, but on closer inspection it becomes evident that the loss of newly acquired achievements is frightening and threatening, since children are aware of their total helplessness in the recent past. Parents, too, become concerned about regressive behavior and may force the child to cope with an additional source of stress: the pressure of living up to expected standards. Brazelton (1999) suggests that these predictable times of regression, or touchpoints, are an opportunity to prepare parents for the next step in their child’s development.

When regression does occur, the best approach is to ignore it while praising existing patterns of appropriate behavior. The child is saying, “I can’t cope with this present stress and accomplish this new skill as well, but I will eventually if given patience and understanding.” For this reason, it is advisable not to introduce new areas of learning when an additional crisis is present or expected, such as beginning toilet training shortly before a sibling is born or during a brief hospitalization.