Health Promotion of the School-Age Child and Family

http://evolve.elsevier.com/wong/ncic

Dental Health, Ch. 14

Eating Disorders, Ch. 21

Health Problems of Middle Childhood, Ch. 18

Injuries and Health Problems Related to Sports Participation, Ch. 39

Injuries—the Leading Killer, Ch. 1

Limit Setting and Discipline, Ch. 3

Nutrition, Ch. 13

Physical and Developmental Assessment of the Child, Ch. 6

Psychosocial History, Ch. 6

Sleep Problems, Chs. 12 and 15

Television, Ch. 2

Promoting Optimum Growth and Development

The segment of the life span that extends from age 6 years to approximately age 12 years has a variety of labels, each of which describes an important characteristic of the period. The middle years are most often referred to as school age or the school years. This period begins with entrance into the wider sphere of influence represented by the school environment, which has a significant impact on development and relationships.

Physiologically the middle years begin with the shedding of the first deciduous tooth and end at puberty with the acquisition of the final permanent teeth (with the exception of the wisdom teeth). In the 5 to 6 years before the school-age period, children progressed from helpless infants to sturdy, complicated individuals with the capacity to communicate, conceptualize in a limited way, and become involved in complex social and motor behavior. Physical growth was been equally rapid. In contrast, the period of middle childhood— between the rapid growth of early childhood and the prepubescent growth spurt—is a time of gradual growth and development, with more even progress in both physical and emotional aspects.

Biologic Development

During middle childhood, growth in height and weight assumes a slower but steady pace compared with the earlier years. Between the ages of 6 and 12 years, children grow an average of 5 cm (2 inches) per year to gain 30 to 60 cm (1 to 2 feet) in height and will almost double in weight, increasing 2 to 3 kg (4.4 to 6.6 lb) per year. The average 6-year-old child is about 116 cm (46 inches) tall and weighs about 21 kg (46.3 lb); the average 12-year-old child stands about 150 cm (59 inches) tall and weighs approximately 40 kg (88.2 lb). During this age period girls and boys differ little in size, although boys tend to be slightly taller and somewhat heavier than girls. Toward the end of the school-age years both boys and girls begin to increase in size, although most girls begin to surpass boys in both height and weight, to the acute discomfort of both sexes.

Physical Changes

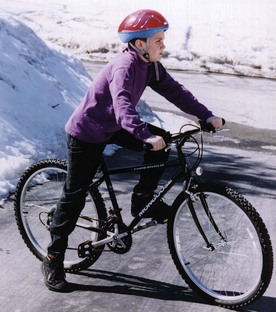

School-age children are more graceful than they were as preschoolers, and they are steadier on their feet. Their bodies take on a slimmer look with longer legs, varying body proportions, and a lower center of gravity. Posture improves over that of the preschool period to facilitate locomotion and efficiency in using the arms and trunk. These proportions make climbing, bicycle riding, and other activities much easier. Fat gradually diminishes, and its distribution patterns change, which contributes to the thinner appearance of children during the middle years.

Accompanying the skeletal lengthening and fat diminution is an increase in the percentage of body weight represented by muscle tissue. By the end of this age period, both boys and girls have doubled their strength and physical capabilities, and their steady and relatively consistent acquisition of refined coordination increases their poise and skill. However, this increased strength is often misleading. Although strength increases, muscles are still functionally immature when compared with those of the adolescent, and they are more readily injured by overuse.

The most pronounced changes that seem best to indicate increasing maturity in children are a decrease in head circumference in relation to standing height, a decrease in waist circumference in relation to height, and an increase in leg length related to height. These indicators often provide a clue to a child’s degree of maturity and have proved useful in predicting readiness for meeting the demands of school. There appears to be a correlation between physical indicators of maturity and success in school.

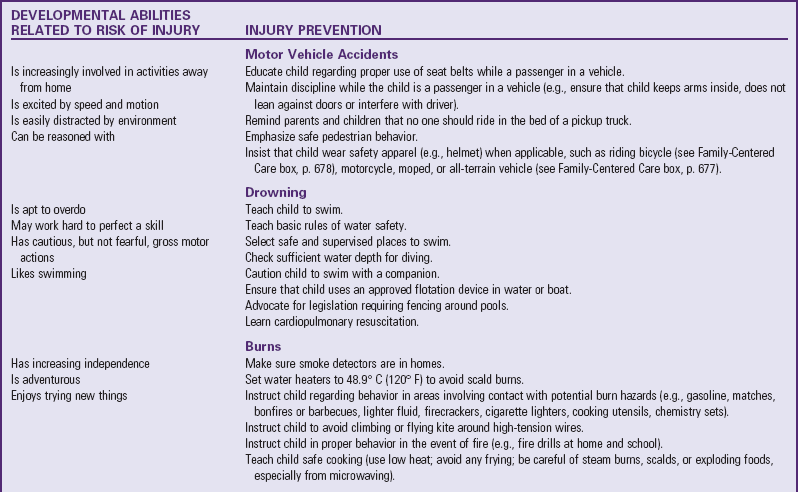

Certain physiologic and anatomic characteristics are typical of school-age children. Facial proportions change as the face grows faster in relation to the remainder of the cranium. The skull and brain grow very slowly during this period and increase little in size thereafter. Because all of the primary (deciduous) teeth are lost during this age span, middle childhood is sometimes known as the age of the loose tooth (Fig. 17-1) and the early years of middle childhood as the ugly duckling stage, when the new secondary (permanent) teeth appear to be much too large for the smaller face.

Maturation of Systems

As the gastrointestinal system matures, the child has fewer stomach upsets; better maintenance of blood sugar levels; and an increased stomach capacity, which permits retention of food for longer periods. The school-age child does not need to be fed as carefully, as promptly, or as frequently as before. Caloric needs are lower than they were in the preschool years and lower than they will be during the coming adolescent growth spurt.

Physical maturation occurs in other body tissues and organs. Bladder capacity, although differing widely among individual children, is generally greater in girls than in boys. There are individual variations in frequency of urination and differences in the same child according to circumstances such as temperature, humidity, time of day, amount of fluids ingested, and emotional state.

The heart grows more slowly during the middle years and is smaller in relation to the rest of the body than at any other period of life. Heart and respiratory rates steadily decrease, and blood pressure increases between ages 6 to 12 (see inside back cover).

The immune system becomes more competent in its ability to localize infections and produce an antibody-antigen response. Because of increased exposure to others in school classes, children can have several infections in the first 1 to 2 years of school while immunity develops.

Bones continue to ossify throughout childhood, but because mineralization is not completed until maturity, children’s bones resist pressure, and muscles pull less than with mature bones. Consequently, parents must be careful to prevent alterations in bone structure and provide children with well-fitted shoes and with chairs and desks that allow correct sitting posture with the feet able to reach the floor and the hips able to fit well back in the seat. Children should have ample opportunity to move around and be cautious about carrying heavy loads. For example, they should shift books and/or tote bags from one arm to the other. Back packs, when worn correctly, distribute weight more evenly.

Wider differences between children are seen at the end of middle childhood than at the beginning; such differences are sometimes striking. These differences become increasingly apparent and, if extreme or unique, may create emotional problems. The nurse should explain the associated characteristics of height and weight relationships, rapid or slow growth, and other important features of development to children and their families. Physical maturity is not necessarily correlated with emotional and social maturity. Seven-year-old children who look like 10-year-old children will think and act like 7-year-olds. To expect behavior appropriate for 10-year-old children from them is unrealistic and can be detrimental to their development of competence and self-esteem. Conversely, to treat 10-year-old children as though they were 7 years old is an equal disservice to them.

Prepubescence

Preadolescence is the period that begins toward the end of middle childhood and ends with the thirteenth birthday. Puberty signals the beginning of the development of secondary sex characteristics, and prepubescence, the 2-year period that precedes puberty, typically occurs during preadolescence.

Toward the end of middle childhood the discrepancies in growth and maturation between boys and girls become apparent. On the average, there is a difference of approximately 2 years between girls and boys in the age of onset of pubescence. For many, especially for girls, preadolescence is a period of rapid growth. For others, mostly boys, it is generally a period of continued steady growth in height and weight.

There is no universal age at which children assume the characteristics of preadolescence. The first physiologic signs appear at about 9 years (particularly in girls) and are usually clearly evident in 11- to 12-year-old children. Although preadolescent children do not want to be different, variability in physical growth and physiologic changes among children of the same sex, and between the two sexes, is often striking at this time. This variability, especially in relation to the onset of secondary sex characteristics, is of utmost concern to the preadolescent. Either early or late appearance of these characteristics is a source of embarrassment and uneasiness to both sexes. Early appearance of secondary sex characteristics in girls is often associated with dissatisfaction with physical appearance, greater general unhappiness, and lower self-esteem. Late-developing boys often have a negative self-concept. Both early appearance of physical characteristics in girls and late appearance in boys have been linked to participation in risk-taking behaviors (early sexual activity, substance use, and reckless vehicle use).

Preadolescence is a time when considerable overlapping of developmental characteristics occurs, with elements of both middle childhood and early adolescence apparent. However, there are sufficient unique characteristics to set this period apart as an age category. Generally, puberty begins no earlier than 10 years in girls and 12 years in boys, but its onset in either sex after the age of 8 years is considered normal. The average age of puberty is 12 years in girls and 14 years in boys. Boys experience little sexual maturation during preadolescence.

Psychosocial Development

Middle childhood is the period of psychosexual development that Freud described as the latency period, a time of tranquility between the oedipal phase of early childhood and the eroticism of adolescence. During this time children experience relationships with same-sex peers following the indifference of earlier years and preceding the heterosexual fascination that occurs for most boys and girls in puberty.

Developing a Sense of Industry (Erikson)

Successful mastery of Erikson’s first three stages of psychosocial development is probably the most important accomplishment in terms of development of a healthy personality (Erikson, 1963). Successful completion of these stages requires a loving environment within a stable family unit that has prepared the child to engage in experiences and relationships beyond this intimate group. During childhood, children affiliate with age-mates, receive the systematic instruction prescribed by their individual cultures, and develop the skills needed to become useful, contributing members of their social communities.

A sense of industry, or a stage of accomplishment, occurs somewhere between age 6 years and adolescence. The goal of this stage of development is to achieve a sense of personal and interpersonal competence through the acquisition of technologic and social skills. School-age children are eager to build skills and participate in meaningful and socially useful work. Interests expand, and, with a growing sense of independence, children want to engage in tasks that they can complete (Fig. 17-2). Failure to develop a sense of accomplishment may result in a sense of inferiority.

Fig. 17-2 School-age children are motivated to complete tasks. A, Working alone. B, Working with others.

Many aspects of industry contribute to the child’s sense of competence and mastery. Intrinsic motivation is associated with increased competence in mastering new skills and assuming new responsibilities. Children gain a great deal of satisfaction from independent behavior in exploring and manipulating their environment and from interaction with peers. Extrinsic sources of reinforcement in the form of grades, material rewards, additional privileges, and recognition provide encouragement and stimulation. Often the acquisition of skills is a means for achieving success in special activities such as athletics or social organizations. Peer approval is a strong motivating factor.

The danger inherent in this period of personality development is the occurrence of situations that might result in a sense of inadequacy or inferiority. This may happen if the previous stages have not been successfully mastered or if a child is incapable of or unprepared to assume the responsibilities associated with developing a sense of accomplishment. Feelings of inferiority or lack of worth come from children themselves or from the social environment. Children with physical or mental limitations are sometimes at a disadvantage for acquisition of certain skills. When the reward structure is based on evidence of mastery, children who are incapable of developing these skills are at risk for feeling inadequate and inferior.

Even children without chronic disabilities show such a wide range of individual differences in capabilities and preferences that they experience feelings of inadequacy in some areas. No child is able to do well in everything, and children must learn that they will not be able to master each skill that they attempt. All children, even children who in most instances have positive attitudes toward work and their own capabilities, feel some degree of inferiority in regard to a specific skill that they cannot master.

For some children, success or aptitude in one area may compensate for failure or ineptitude in another. However, the differences in reinforcement provided for success in various areas have significant effects on feelings of adequacy. For example, in the United States, reading proficiency is more highly rewarded than the mechanical aptitude needed for tinkering with broken automobile engines. Society places a higher value on success in team sports than on success in repairing a bicycle. Compensating for the inability to excel in more socially valued skills through mastery of other, less valued skills is difficult for children. If the social environment places a negative value on any failure, feelings of inferiority may be increased in the less capable child. Repeated failures can generate such strong feelings that eventually the child is reluctant to attempt any new task or is fearful of not being able to perform as well as his or her peers. Thus intrinsic motivation toward engaging in a task for the pleasure of the challenge conflicts with the external forces that cause feelings of doubt and inferiority. Consequently, the child may no longer try.

A child’s concept of success or failure is important. Children who aspire to more than they are capable of usually experience failure. In contrast, children who set their aspirations lower than their level of achievement are likely to experience success. Most accomplishments during the school years are very public. Family, teachers, and peers are all aware of success or failure in school. In school and sometimes at home, feelings of inferiority may be produced through comparisons with others that suggest the child is not as good as a peer, sibling, or member of another group. This inadequacy becomes a source of embarrassment. The child may even be shamed for the failure. Earlier conflicts of doubt and guilt are closely associated with feelings of inferiority.

A sense of accomplishment also involves the ability to cooperate, to compete with others, and to cope effectively with people. Middle childhood is the time when children learn the value of doing things with others and the benefits derived from division of labor in the accomplishment of goals. Children need and want real achievement. When they can accomplish tasks that need to be done and perform well despite individual differences in capacities and emotional development, and when they are suitably rewarded, children develop a sense of industry and accomplishment that prepares them for establishing a stable identity later in life.

Temperament

The reactivity patterns or temperamental traits identified in infancy may continue to influence behavior in middle childhood. Analyzing behavioral patterns observed in past situations can provide clues to the way that a child may react to new situations, although long-range projections are not always successful. Through interaction with the environment, experiences, motives, and abilities, many children change. In some children major temperamental characteristics persist into adolescence; in others they do not.

Many children tend to be identified with one of three broad temperament categories: easy, slow to warm up, and difficult. Parents and teachers are in an excellent position to assess a child’s behavioral style and to try to make their demands and expectations consonant with the individual child’s temperamental characteristics. With easy children this rarely poses a problem. They adapt readily to many childrearing programs and new situations. School entry and other changes usually go smoothly and are accomplished with minimal stress. Difficulties arise with children who are slow to warm up or are difficult or easily distracted.

Slow-to-warm-up children usually exhibit discomfort when introduced to new situations and need time to become accustomed to a new environment, authority figures, and expectations. These children may respond with tears, somatic complaints, or other maneuvers to avoid the event. The nurse should encourage them to try new experiences but allow them to adapt to their surroundings at their own speed. Pressure to move quickly into new situations only strengthens the tendency to withdraw. After-school activities can be a cause for reaction, but attending with a friend or contracting for permission to withdraw after a trial of a specified number of times may provide them with sufficient incentive to try (see Critical Thinking Exercise).

Difficult or easily distracted children may benefit from “practice” sessions in which they are prepared for a given event by role playing, visiting the site, or reading or listening to stories, or use of other methods to acquaint them with what to expect. Children who are persistent need to know when to stop what they are doing so that the signal to stop will not come as a surprise or trigger a reaction. Nurses need to handle children with difficult temperaments with exceptional patience, firmness, and understanding so that they can learn appropriate behavior in their interactions with others. If possible, teachers’ styles and characteristics should match the temperament of children to ensure a good fit.

Cognitive Development (Piaget)

When they enter the school years, children begin to acquire the ability to relate a series of events and actions to mental representations that they can express both verbally and symbolically. This is the stage that Piaget describes as concrete operations, when children are able to use their thought processes to experience events and actions. The term operation implies an action that is performed on an object or set of objects; thus a mental operation is an alteration or transformation that an individual carries out in thought rather than in action. Toddlers or preschool children can perform acts that involve ordering, such as correctly arranging a graduated set of circles from largest to smallest on a stick, and can find their way to a friend’s house, but they are unable to verbalize the actions involved in the process. School-age children are able to articulate the process and perform the actions mentally without the need to carry out the behaviors.

As children move from the preschool years into the school years, their conceptual abilities become increasingly flexible. During the concrete operational period, they acquire the ability to perform cognitive operations and apply these new skills when thinking about objects, situations, and events. Their rigid, egocentric outlook is replaced by thought processes that allow them to see things from another’s point of view. They become aware of a variety of perspectives and become more sensitive to the fact that others do not always perceive events exactly as they do. They are able to delay an action until they have evaluated alternative responses to situations. Their steady reduction in egocentricity helps form the basis for logical thought and the development and maturation of morality.

The concrete operational stage occurs between the ages of 7 and 11 years. During this stage children develop an understanding of relationships between things and ideas. They progress from making judgments based on what they see (perceptual thinking) to making judgments based on what they reason (conceptual thinking). They are increasingly able to master symbols and to use their memory store of past experiences to evaluate and interpret the present.

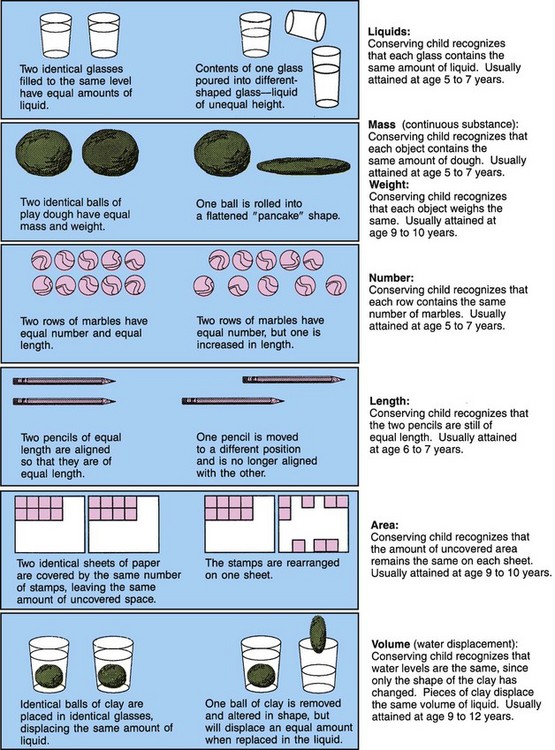

One of the major cognitive tasks of school-age children is mastering the concept of conservation—that physical matter does not appear and disappear by magic. They learn that certain properties of the environment are not changed simply by altering their disposition in space. They are able to resist perceptual cues that suggest alterations in the physical state of an object.

The nurse can use commonplace items to demonstrate the conservation of liquid, mass, number, length, area, and volume (Fig. 17-3). To explain the observation that the mass of the clay in the figure has not been altered, children use one of three concepts:

1. Identity—Because nothing has been added and nothing has been taken away, the pancake is still the same clay. Nothing has changed but the shape.

2. Reversibility—The clay can be reshaped into its original form (a ball).

3. Reciprocity—Although the pancake appears larger in circumference, the ball is much thicker. In this instance the child demonstrates the ability to deal with two dimensions at the same time and to comprehend that a change in one dimension compensates for a change in another.

When children are able to use the concepts of identity, reversibility, and reciprocity, they can conserve along any physical dimension. They perceive the concept of volume in relation to container size and shape, recognize that size is not necessarily related to weight or volume, and are able to manipulate or “see” in a concrete manner. They recognize that logical operations move in two directions (such as addition and subtraction or multiplication and division) and that certain properties are invariant (e.g., 7 remains 7 whether it is represented by 3 + 4, 2 + 5, seven buttons, seven stars, or seven boys).

There appears to be a developmental sequence in children’s capacity to conserve matter. Children usually grasp conservation of numbers (ages 5 to 6) before conservation of substance. Conservation of liquids, mass, and length usually is accomplished at about ages 6 to 7, conservation of weight sometime later (ages 9 to 10), and conservation of volume or displacement last (ages 9 to 12).

Children use reversibility in selecting a course of action, which thus provides greater control over themselves and their environment. They have the ability to think through an action sequence, anticipate the consequences, and, if needed, return to the beginning and rethink the action in a different direction. They no longer need to experience an action before they can anticipate the results. Reversibility allows mental action and enables children to disassemble and reassemble certain kinds of things in their thoughts.

Classification skills involve the ability to group objects according to the attributes that they have in common. School-age children can place things in a sensible and logical order, group and sort, and hold a concept in their minds while they make decisions based on that concept. In middle childhood children get a great deal of enjoyment from classifying and ordering their environment. They become occupied with numerous and varied collections of objects, such as stamps, shells, dolls, cars, stones, cards, stuffed animals, and anything that is classifiable (Fig. 17-4). They even begin to order friends and relationships (e.g., first best friend, second best friend).

As children mature, they progress from collecting simply for the sake of collecting and become more selective and discriminating. Their classification systems become more complex and are based on abstract ideas rather than on perception and experience. Much of the pleasure of collections is in the appraising, ordering, and reordering of the parts.

School-age children are able to serialize, or to arrange objects according to some ordinal scale or quantified dimension such as size, weight, or color. They develop the ability to understand relational terms and concepts, such as bigger and smaller; darker and paler; heavier and lighter; to the right of and to the left of; first, last, and intermediate (e.g., fourth, second); and more than and less than. They can see family relationships in terms of reciprocal roles; for example, to be a brother, one must have a sibling.

During the school-age years children develop combinatorial skills—the ability to manipulate numbers and to learn the skills of addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. They learn to apply the basic operations to any object or quantity. They learn the alphabet and the ever-widening world of symbols called words that can be arranged in terms of structure and their relationship to the alphabet. They learn to tell time, to see the relationship of events in time (history) and places in space (geography), and to combine time and space relationships (geology and astronomy).

The most significant skill, the ability to read, is acquired during the school years and becomes the most valuable tool for independent inquiry. Children’s capacity for exploration, imagination, and expansion of knowledge is enhanced by the ability to read as they progress from the repetition and confusion of early efforts to increasing facility and comprehension. Formal academic learning begins at ages 5 to 6 years, when children’s intellectual capabilities and cognitive processes allow them to attain intellectual achievements.

Moral Development (Kohlberg)

As children move from egocentrism to more logical patterns of thought, they also move through stages in the development of conscience and moral standards. Young children do not believe that standards of behavior come from within themselves but that others establish and enforce these rules. During preschool years, children perceive rules as definite and require no reason or explanation. Children learn the standards for acceptable behavior, act according to these standards, and feel guilty when they violate the standards. Although children 6 or 7 years old know the rules and what they are supposed to do, they do not understand the reasons behind them. Young children usually judge an act by its consequences. Rewards and punishment guide their judgment; a “bad” act is one that breaks a rule or causes harm. When a child and an adult differ in judging an act, the adult is right. Children may believe that what other people tell them to do is right and that what they themselves think is wrong. Consequently, children 6 or 7 years old are more likely to interpret accidents and misfortunes as punishment for misdeeds or “bad” acts.

Older school-age children are able to judge an act by the intentions that prompted it rather than just by the consequences. Rules and judgments become less absolute and authoritarian and begin to be founded more on the needs and desires of others. Rules of conduct are more readily considered in terms of mutual agreement and are based on cooperation and respect for others. Older children will likely view a rule violation in relation to the total context in which it appears; reactions are influenced by the situation as well as by the morality of the rule itself. However, it is not until adolescence or beyond that children are able to view morality on an abstract basis with sound reasoning and principled thinking. Although younger children can judge an act only according to whether it is right or wrong, older children take into account a different point of view to make a judgment. They are able to understand and accept the concept of treating others as they would like to be treated.

Spiritual Development

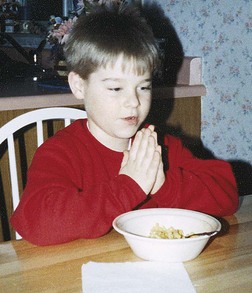

Children at this age think in very concrete terms but are avid learners and have a great desire to learn about their God or deity. They picture God as human and use adjectives such as “loving” and “helping” to describe their deity. They are fascinated by heaven and hell and, with a developing conscience and concern about rules, they fear going to hell for misbehavior. School-age children want and expect to be punished for misbehavior and, if given the option, tend to choose a punishment that “fits the crime.” Often they view illness or injury as a punishment for a real or imagined misdeed. The beliefs and ideals of family and religious personages are more influential than those of their peers in matters of faith.

School-age children begin to learn the difference between the natural and the supernatural but have difficulty understanding symbols. Consequently, religious concepts must be presented to them in concrete terms. They try to relate phenomena in the world in a logical, systematic manner, which is both satisfying and occasionally disheartening. Religion is a means whereby children can relate to their deity in a direct and personal way.

Prayer and other religious rituals are often a comfort to children, and if these activities are a part of children’s daily lives, they can help children cope with threatening situations (Fig. 17-5). Their petitions to their God in prayers tend to be for tangible rewards. Although younger children expect their prayers to be answered, as children get older they begin to recognize that this does not always occur and become less concerned when prayers are not answered. They are able to discuss their feelings about their faith and how it relates to their lives (see Cultural Competence box).

Language Development

Children enter middle childhood with remarkably efficient language skills, but they make many important linguistic achievements during the school-age years. During the elementary school years they learn to correct previous syntactic errors and begin to use more complex grammatical forms, such as correct past tenses for irregular verbs, correct plurals for irregular nouns, and correct personal pronouns.

Word usage and the ability to find and retrieve words quickly when called on to produce what they know in a relatively short time grow considerably during the school years. Children learn to apply the minimum-distance principle—the rule that the subject of a verb in an active sentence is the noun or pronoun that immediately precedes it. For example, a 6-year-old child will understand the sentence “Ask Mary her last name” but until age 9 or 10 years will be confused by the sentence “Ask Mary what to bring to the party.”

Narrative skills improve markedly. School-age children are increasingly able to provide directives that others can correctly interpret without visual data (e.g., explain directions over the telephone). By age 10 to 12 years the child should be able to use factitive words (such as know, think, and believe), as well as complex pronouns and conjunctions, and be able to form grammatically correct sentences. School-age children gradually become more proficient at making inferences about meanings and learn the subtle exceptions to grammatical rules. This makes them less likely to engage in literal interpretation of messages.

They rapidly develop metalinguistic awareness—an ability to think about language and to comment on its properties. This enables them to appreciate jokes, riddles, and puns that involve play on words, sounds, or double meanings. They are beginning to understand metaphors and figurative statements, such as “A stitch in time saves nine.” The acquisition of cognitive skills enables them to think about the quality of their own and others’ speech and to evaluate and clarify messages.

Social Development

At the beginning of middle childhood, children enter a period of less intense emotions, secure in their dependency on their parents and family and with self-confidence tempered by a more realistic perspective. They have the energy to explore the environment beyond the family, to gradually increase the scope of interpersonal interactions, and to invest their curiosity in understanding the world.

Identification with peers is a strong influence in children’s gaining independence from parents. The aid and support of peers provides children with enough security to risk the moderate parental rejection brought about by each small victory in their development of independence.

Questions of masculinity and femininity take on importance as sex-role learning assumes more prominence. Boys associate with boys, and girls with girls, each group pursuing its own interests, with communication between the sexes confined to that which is necessary. Much of the child’s concept of the appropriate sex role is acquired through relationships with peers. During the early school years there is little difference relative to sex in the play experiences of children. Both girls and boys share games and other activities. However, in the later school years the differences become marked.

Social Relationships and Cooperation

Daily relationships with age-mates provide the most important social interactions for school-age children. For the first time, children are able to join in group activities with unrestrained enthusiasm and steady participation. Previously, interactions were limited to short periods under considerable adult supervision. With increased skills and wider opportunities, children become involved with one or several peer groups in which they can gain status as respected members.

Valuable lessons are learned from daily interaction with age-mates. First, children learn to appreciate the numerous and varied points of view that are represented in the peer group. As they play together, children discover that there are many occupations for fathers and mothers, more than one version of the same song, different rules for the same game, and different customs for celebrating the same holiday. As children interact with peers who see the world in ways that are somewhat different from their own, they become aware of the limits of their own point of view. Because age-mates are peers and are not forced to accept one another’s ideas as they are expected to accept those of adults, other children have a significant influence on decreasing the egocentric outlook of the individual child. Consequently, children learn to argue, persuade, bargain, cooperate, and compromise to maintain friendships.

Second, children become increasingly sensitive to the social norms and pressures of the peer group. The peer group establishes standards for acceptance and rejection, and children may be willing to modify their behavior to be accepted by the group. They are judged by the physical impression they convey, the skills they possess, and other abilities they can demonstrate. The need for peer approval becomes a powerful influence toward conformity. Children learn to dress, talk, and otherwise behave in a manner acceptable to the group. A variety of roles, such as class joker or class hero, may be assumed by the individual child to gain approval from the group. However, no child can adapt perfectly to all the requirements of the peer group. If some children find differences between the values of the peer group and the values of their families to be too great, they may relinquish the pleasure of interaction with the group to abide by the regulations established in the home. Thus, to diminish conflict within the family, some children may be forced into a position outside the peer group.

Third, the interaction among peers leads to the formation of intimate friendships between same-sex peers (Fig. 17-6). School age is the time when children have “best friends” with whom they share secrets, private jokes, and adventures; they come to one another’s aid in times of trouble. In the course of these friendships, children also fight, threaten, break up, and reunite. These dyadic relationships, in which children experience love for and closeness with a peer, seem to be important as a foundation for heterosexual relationships in adulthood. The conflicts encountered in the relationship are usually resolved in terms that children are able to control. Because neither child has authority over the other, as in an adult-child relationship, children must work through their differences within the framework of their commitment to each other.

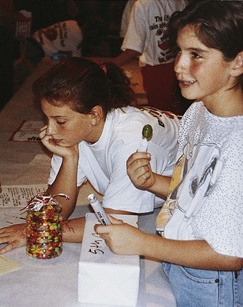

Clubs and Peer Groups: One of the outstanding characteristics of middle childhood is the formation of formalized groups or clubs. Initially, children in the early middle years merely hang around the periphery of the formalized group, watching, learning, practicing various skills, and participating in group activities whenever the members of the group allow them to do so. As they age, children eventually take their places as full-fledged participating group members.

A prominent feature of middle childhood groups is the code of rigid rules imposed on the members. Exclusiveness is evident in the selection of persons given the privilege of joining. Acceptance in the group often depends on a pass-fail basis according to social or behavioral criteria. Conformity is the core of the group structure. There are often secret codes, shared interests, special modes of dress, and special words that signify membership in the group. Each child must follow a standard of behavior established by the group. Conforming to the rules provides children with feelings of security and relieves them of the responsibility of making decisions.

Membership in the group provides children with a comfortable place in society. Many of the qualities valued by the group, such as physical strength, daring, ingenuity, and comradeship, have not been stressed in the family. However, these are values that contribute to an individual child’s total personality. By merging their identity with the identities of their peers, children move from the family group to an outside group as a step toward further independence. They substitute conformity to a peer-group pattern for conformity to a family pattern while they are still too insecure to function independently.

During the early school years, groups are small and loosely organized, with changing membership and little formal structure. They do not demonstrate the elements of give and take, cooperation, and order that are seen in groups of older children. As a rule, girls’ groups are less formalized than boys’ groups, and although there may be a mixture of both sexes in groups in the earlier school years, those of later school years are composed predominantly of children of the same sex. Common interests are frequently the central element around which a group is structured.

Children’s strong desire not to be different creates problems for those who are, for various reasons, unable to meet the accepted standards of the peer group. Children with disabilities or those who are in some way unable to compete have a difficult time. Children become self-consciousness when they are unable to dress like other children, do not have spending money like other children, or appear different from other children.

Children who have physical characteristics that are obviously different (such as birthmarks, ears that “stick out,” or physical defects) may be set apart from the peer group and become a target for the criticism and ridicule. Peer-group identification and association are essential to socialization.

Poor relationships with peers and a lack of group identification can also contribute to bullying behavior. Bullying is the infliction of repetitive physical, verbal, or emotional abuse by one or more individuals intended to harm or bother another who is perceived as being less physically or psychologically powerful than the aggressor(s). Bullying can occur in varying degrees of severity in a physical, social, or emotional context. Boys usually participate in more direct or physical acts of bullying, whereas girls are commonly more involved with indirect acts such as spreading rumors or social exclusion. Although bullying can occur in any setting, it usually takes place in a classroom or on the playground when supervision is minimal (Vreeman and Carroll, 2007). Approximately 25% of students engage in bullying or are victims of bullying during elementary school, with bullying peaking on transition from elementary to secondary school (Jenson and Dieterich, 2007). Children who are bullies are often defiant, antisocial, impulsive, easily frustrated, and likely to break school rules.

Bullies and victims of bullying are at risk for long-term psychologic disturbances and psychiatric symptoms. Future problems of bullies include a higher risk for conduct problems, hyperactivity, school drop-out, and participation in criminal behavior (Gini, 2007; Jenson and Dieterich, 2007). Victims of bullying are at increased risk for low self-esteem; anxiety; feelings of insecurity; poor academic performance; and psychosomatic complaints such as feeling tense, tired, or dizzy (Gini, 2007; Jenson and Dieterich, 2007). Bullying can be reduced or prevented through supportive relationships with family, intervention of school personnel, and involvement with positive peer groups.* Many school districts have developed bullying prevention programs in response to local circumstances; however, these programs have yet to be critically evaluated for their effectiveness.

Although peer-group identification and association are essential to a child’s emergence into the world, dangers are inherent in strong peer-group attachment. Peer pressure may force children into taking risks, even against their better judgment. Peer-group activities that result in unacceptable, unlawful, or criminal gang violence are increasing in the United States and represent a significant challenge for health professionals and teachers who work with children (see Community Focus box).

Relationships with Families

Although the peer group is highly influential and necessary to normal child development, parents are the primary influence in shaping children’s personalities, setting standards for behavior, and establishing value systems. Family values usually predominate when parental and peer value systems come into conflict. Although children may appear to reject parental values while testing the new values of the peer group, ultimately they retain and incorporate many parental values into their own value systems. Peer associations seem to remain within the social class system.

As children move into a wider world of peer-group relationships, parents are faced with the task of letting go of control. Parents may find it difficult to face the rejection that children demonstrate as they become more involved with their peer groups. Children may want to spend more time in the company of their peers, may seem eager to leave the house, and often prefer activities of the peer group to family activities. During this time, children discover that parents can be wrong, and they begin to question the knowledge and authority of the parents who previously were considered to be all-knowing and all-powerful. Parents can best serve the interests of their children through tolerant understanding and support.

Although increased independence is the goal of middle childhood, children are not yet prepared to abandon parental control. Children need and want restrictions placed on their behavior; they are not yet prepared to cope with all of the problems of their expanding environment. They feel more secure knowing that there is an authority greater than themselves to implement controls and restrictions. Children may complain loudly about the restrictions and try to break down parental barriers, but they are uneasy if they succeed in doing so. Children feel secure with reasonable, consistent controls. They respect the adults on whom they can rely to prevent them from acting on each and every urge. Children see this behavior as an expression of love and concern for their welfare.

Children also need their parents as adults, not as “pals.” Sometimes parents, hurt by their children’s rejection, attempt to maintain their children’s love and gratitude by assuming the role of pal. Children need the stable, secure strength provided by mature adults to whom they can turn during troubled relationships with peers or stressful changes in their world. During a disruption in their lives, such as times of failure, periods of illness, or a move that separates them from the security of friends, children need the firm, secure anchor of parental interest and concern. With a secure base in a loving family, children are able to develop the self-confidence and maturity needed to stand independently.

Children’s relationships with siblings change during the middle years. Children view siblings as equal in power and status. In earlier years, older siblings were influential in the younger siblings’ learning. In the middle years the relationship becomes one of companionship. Positive emotional tone increases, but sibling conflict also increases as the siblings get older. Middle childhood is a period of transition for sibling relationships, a juncture between the open bickering of early childhood and the supportive relationships observed in adult siblings.

Development of Self-Concept

Closely associated with developing a sense of industry is developing a concept of one’s value and worth. With the emphasis on skill building and broadened social relationships, children are continually occupied in the process of self-evaluation. Children’s self-concepts are composed of their own critical self-assessments plus their interpretations of the opinions of others. Self-concept refers to a conscious awareness of a variety of self-perceptions, such as one’s physical characteristics, abilities, values, and self-ideals, and one’s idea of self in relation to others.

Body Image

Body image is what children think about their bodies. School-age children are knowledgeable about the human body, and social development during this period focuses to a large extent on the body and its capabilities. School-age children can draw a recognizable human figure, although individually their portrayal of body parts may vary considerably. They are acutely aware of their own bodies as well as those of their peers and those of adults. It is important that children know body functions and that adults correct any misinformation children have about the body (e.g., what is fat).

During the school years, children focus on peer relationships and conform to group norms. They evaluate how their physical appearance, body configuration, and coordination compare with those of their peers. The head is the most noticeable and, to them, important part of the body. They also model themselves after their parents and compare themselves to favored peers and images observed in the media.

Children are aware of physical disabilities in others, and it is not unusual for them to believe that their own bodies are not the right size or the right shape or are in some way defective. They respond to such concerns in a variety of ways. For example, they will conceal perceived shortcomings of body or performance, as in the obese child who refrains from going swimming, the child who conveniently forgets a gym suit, the child who conceals an imagined defect, or the child with enuresis who declines invitations to slumber parties. Children seldom express these concerns to families. However, they need reassurance about both the uniqueness and the sameness of their bodies while their privacy is respected and they are allowed appropriate protective strategies. Children who are different become aware of the differences and may find themselves excluded from the group. When children are teased or criticized about being different, the effect can last even into adulthood.

Self-Esteem

Self-esteem is children’s pictures of their individual worth and consists of both positive and negative qualities. Children actively strive to achieve internalized goals. At the same time, they continually receive feedback on the quality of their performance from individuals they consider to be authorities. By the time they reach school age, children have received messages regarding the extent to which they are able to accomplish tasks that have been delegated to them. For example, one child may have been given prestigious responsibilities at home or at school or received special commendation for an achievement. On the other hand, another child may have been sent to a special class for slow learners or may have been the last person selected when children chose sides for a game. These and other signs serve as clues to social worth that children incorporate as part of their self-evaluation.

Children approach the process of self-evaluation from a framework of either self-confidence or self-doubt. Children who have mastered the maturational crises of autonomy and initiative are able to face the world with feelings of pride rather than shame. At first, children’s self-concepts are formed exclusively from their perceptions of their parents’ evaluation of them. During middle childhood the opinions of peers and teachers are important. Criticisms and peer approval are additional sources of data for evaluation. Parents and other adults are no longer the only persons who respond to their skills, talents, and abilities; peers also identify skills and capabilities. Each child soon begins to internalize these outside opinions. If children regard themselves as worthwhile or satisfactory persons, they have high self-esteem, self-confidence, and a positive self-concept. If they view themselves as worthless, they have low self-esteem.

Pets also influence a child’s self-esteem. Pets can have a positive effect on physical and emotional health and can teach children the importance of nurturing and nonverbal communication (Podberscek, 2006).

Children encounter difficulties assessing their own abilities because they rely on their own expectations or on the expectations expressed by others regarding their performance. They depend almost entirely on external evidence of worth, such as school grades, teachers’ comments, and parental and peer approval. Children do not yet have the capacity to develop their own independent criteria to evaluate their own accomplishments. It is especially difficult for them to assess their achievement in abstract skills.

Nothing succeeds like success. Significant adults in children’s lives can often manage to manipulate the environment so that children meet with success. Each small success can improve a child’s self-image. The more positive children feel about themselves, the more confident they feel in trying again for success. All children profit from feeling that they are special to significant adults. A positive self-image makes them feel likable, worthwhile, and capable of valuable contributions. Such feelings lead to self-respect, self-confidence, and a general feeling of happiness. Parents can help their school-age children develop self-esteem by being honest, by providing opportunities for creativity, by helping them succeed in activities, and by providing positive reinforcement. Nurses can enhance self-esteem by fostering supportive relationships between children and members of their families and by emphasizing children’s strengths and positive aspects of their behavior (see Community Focus box).

Development of Sexuality

Evidence indicates that many children experience some form of sex play during or before preadolescence as a response to normal curiosity, not as a result of love or sexual urge. Children are experimentalists by nature, and this play is incidental and transitory. Adverse emotional consequences or guilt feelings depend on how the parents manage the behavior and whether children view their actions as wrong in the eyes of significant persons, particularly their parents.

Children’s attitudes toward sex are acquired indirectly at an early age and affect the way they respond to sexual information presented later. Many parents discourage sexual exploration, either through subtle substitution of activities that divert their children’s attention from the genitalia or by expressions of anger or disgust at their children’s behavior. These tactics clearly communicate to children that they should not engage in such activities, discourage questions about sex, and limit the sources of information.

Sex Education

Parents may not teach young children the correct terminology for sexual organs or sexual feelings. Often the only vocabulary available to children is one that identifies sexual organs with excretory functions. If children learn that excretory organs and functions are dirty, they may associate “dirtiness” with the reproductive organs and functions. If children learn the correct terminology for the organs and their functions, this will eliminate or reduce this association.

Because parents often either repress or avoid their children’s sexual curiosity, sexual information received in childhood may be acquired almost entirely from peers. Such information is often transmitted in secret conversations and contains considerable misinformation. These communications can also create anxiety in children and inhibit spontaneous expressions or questioning of their parents.

Although middle childhood is an ideal time for formal sex education, this subject has created considerable controversy. Many parents and groups are unconditionally opposed to the inclusion of sex education in the schools. Others believe that information relating to sexual maturation and the process of reproduction should be presented as naturally as information about other natural phenomena, such as the growth of plants, the changing seasons, and the migratory habits of birds. When sex education is presented from a life span perspective and treated as a normal part of growth and development, the information is less likely to contain overtones of uncertainty, guilt, or embarrassment that could in turn produce anxiety in children.

Sex education programs have been successfully incorporated into a number of elementary school curricula. In many of these programs, sexuality is presented in the context of its central role as a biologic mechanism for the survival of the culture. Children learn that sexual maturation and reproduction represent each individual’s contribution to the natural order of things. This approach provides a natural entry into discussion of sexuality as a basis for family units, marriage, and attitudes toward children, as well as an entry into a presentation of the biologic facts of sexuality. Many sex education programs also emphasize that sexual intimacy is part of a close, personal relationship and a means of conveying love, as well as a means for ensuring the survival of the species.

Nurse’s Role in Sex Education

No matter where nurses practice, they can provide information on human sexuality to both parents and children. To discuss the topic adequately, nurses must understand the physiologic aspects of sexuality; know the common myths and misconceptions associated with sex and the reproductive process; understand cultural and societal values; and be aware of their own attitudes, feelings, and biases.

When nurses present sexual information to children, they should treat sex as a normal part of growth and development. Nurses should answer questions honestly, matter-of-factly, and at the child’s level of understanding. School-age children may be more comfortable when boys and girls are segregated for discussions; however, each group needs information about both sexes.

Children need help to differentiate sex and sexuality. Exercises focused on clarifying values, identifying role models, solving problems, and accepting responsibility are important to prepare school-age children for early adolescence and puberty. In addition, care providers need to explain sexual information that is discussed via the media or jokes. A comprehensive sex education program including information about abstinence, contraception, and birth control methods should be presented during the middle school years (Eisenberg, Bernat, Bearinger, et al, 2008). Teaching a child to be sexually responsible is an important component of sex education. Health care providers should supply specific information concerning sexually transmitted infections, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Anticipatory guidance should include information about prevention, transmission, and implications of sexually transmitted infections.

Preadolescents need precise and concrete information that will allow them to answer questions such as “What if I start my period in the middle of class?” or “How can I keep people from telling I have an erection?” It is important to tell them what they want to know and what they can expect to happen as they mature sexually.

During encounters with parents, nurses can be open and available for questions and discussion. They can set an example by the language they use in discussing body parts and their function and by the way in which they deal with problems that have emotional overtones, such as exploratory sex play and masturbation. Parents need help to understand normal behaviors and to view sexual curiosity in their children as a part of the developmental process. Assessing the parents’ level of knowledge and understanding of sexuality provides cues to their need for supplemental information that will prepare them for increasingly complex explanations as their children grow older.

Children with developmental disabilities need emotional and sexual relationships. Parents of children with developmental disabilities may need special assistance and help with sex education. In 1996 the American Academy of Pediatrics developed specific guidelines that discuss ways to teach these children about human anatomy, pubertal changes, expression of physical affection, protection from sexual abuse or exploitation, and independence in personal hygiene and self-care. Sex education for children with disabilities requires individualized techniques, depending on the type and degree of disability (Murphy and Young, 2005). Nurses must bring the issue of sexuality out in the open and promote the idea that sexuality is a part of every individual’s identity in order to address educational needs (Murphy and Young, 2005).

Sometimes participation in short classes or group discussions can help parents address disturbing behaviors and anticipate their children’s questions and learning needs. It is wise to include both parents in such activities when possible. Both parents should assume responsibility for sex education in the home so that the children will not acquire a distorted view of either the male or the female role that may alter relationships with the opposite sex in later life.

Play

As children enter the school years, their play takes on new dimensions that reflect a new stage of development. Not only does play involve increased physical skill, intellectual ability, and fantasy, but as children form groups and cliques, they begin to evolve a sense of belonging to a team or club. To belong to a group is of vital importance. Clubs, societies, and organizations are important parts of the culture of childhood.

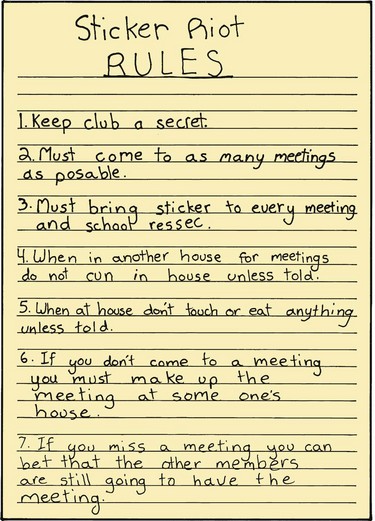

Rules and Rituals

The need for conformity in middle childhood is strongly manifested in the activities and games so important in the life of school-age children. Up to this point, they have either played games they have invented themselves or have played in the company of a friend or an adult, and rules more or less evolved with the game. Now they begin to see the need for rules, and the games they play have fixed and unvarying rules that may be bizarre and extraordinarily rigid (especially those made up by the group). But part of the enjoyment of the game is knowing the rules, because knowing means belonging. Once the rules are established and agreed on, the demand for conformity is strong (Fig. 17-7).

Conformity and ritual characterize the play of school-age children, not only in games, but also in behavior and language. Childhood is full of chants and taunts, such as “Eeny, meeny, miney, mo,” “Last one is a rotten egg,” and “Step on a crack, break your mother’s back.” Children receive a great deal of pleasure and power from such sayings, which have been handed down with few changes through generations.

Team Play: A more complex form of group play that develops from the need for peer interaction involves the team games and sports that are part of the school years. Such games may require a referee, umpire, or person of authority so the rules can be followed more accurately. Team membership has several characteristics that promote child development during the middle years.

Children learn to subordinate personal goals to group goals. Team membership means that each child is accountable to the other team members and that each member’s acts may affect the success or failure of the entire group. Each member’s behavior is open to public evaluation, and children risk ostracism, ridicule, or scapegoating if they contribute to a team loss. Although individual skills are recognized, team successes and failures are shared by all members. Children learn the concept of interdependence and the reliance of all players on one another.

Children learn that division of labor is an effective strategy for the attainment of a goal. Each person on a team has a specific function, which increases the team’s chances of winning. Once children learn that certain goals are best accomplished by dividing tasks among several individuals, they can transfer this knowledge to other social situations. Children also learn that some children are best equipped to perform one part of the task and other children are best suited to another aspect of the task.

Team play helps children learn about the nature of competition. In all team play there is a winning side and a losing side. Because losing is often interpreted as failure, children go to great lengths to avoid the public embarrassment and personal shame that accompany failure. The more a child identifies with the team and values membership in the group, the more distasteful losing becomes. Fear of losing and the failure it implies are strong incentives for group commitment; however, winning is not universally given high value. Some cultures and subcultures emphasize the game and consideration for one’s companions rather than the outcome.

Team play also contributes to children’s social, intellectual, and skill growth. Children work hard to develop the skills needed to become members of a team, to improve their contribution to the group effort, and to anticipate the consequences of their behavior for the group. Team play helps stimulate cognitive growth as children are called on to learn many complex rules, make judgments about those rules, plan strategies, and assess the strengths and weaknesses of members of their own and the opposing teams (Fig. 17-8).

Quiet Games and Activities

Although the play of school-age children can be highly active, they also enjoy many quiet and solitary activities. The middle childhood years are the time for collections, and young school-age children’s collections are an odd assortment of unrelated objects in messy, disorganized piles. Collections of later years are more orderly and selective and often are organized neatly in scrapbooks, on shelves, or in boxes.

School-age children become fascinated with increasingly complex board, card, and computer games. Children play these games alone or in groups. As in all games, the adherence to rules is fanatic. There is usually much discussion and argument, but children easily resolve disagreement by learning the appropriate rules of the game.

The newly acquired skill of reading becomes increasingly satisfying as school-age children begin to expand their knowledge of the world through books (Fig. 17-9). School-age children never tire of stories, and, like preschool children, they love to have stories read aloud. They also enjoy sewing, cooking, carpentry, gardening, and creative endeavors such as painting. Many creative skills, such as those involving music and art, and athletic skills, such as swimming, riding, hiking, dancing, and karate, are acquired during childhood and continue to be enjoyed into adolescence and adulthood (Fig. 17-10).

Hero worship is another characteristic of children and adolescents. The object of the adoration can be a friend, relative, teacher, or national sports or entertainment figure. However, problems can arise when the idol proves to be an inappropriate role model.

Ego Mastery

Play also affords children the means to acquire representational mastery over themselves, their environment, and other persons. Through play, children can feel as big, as powerful, and as skillful as their imaginations will allow, and they can attain vicarious mastery and power over whomever and whatever they choose. They need to feel in control in their play. School-age children still need the opportunity to use large muscles in exuberant outdoor play and the freedom to exert their newfound autonomy and initiative. They need space in which to exercise large muscles and to work off tensions, frustrations, and hostility. Physical skills practiced and mastered in play help to develop a feeling of personal competence, which contributes to a sense of accomplishment and helps provide a place of status in the peer group.

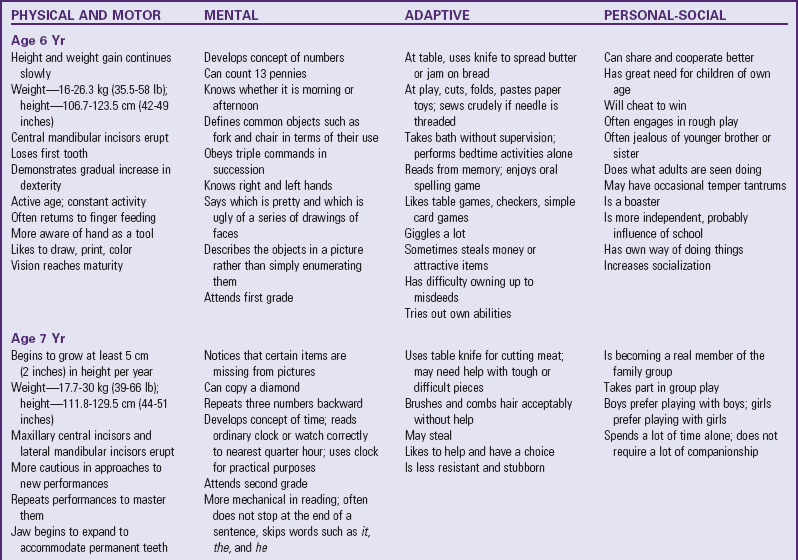

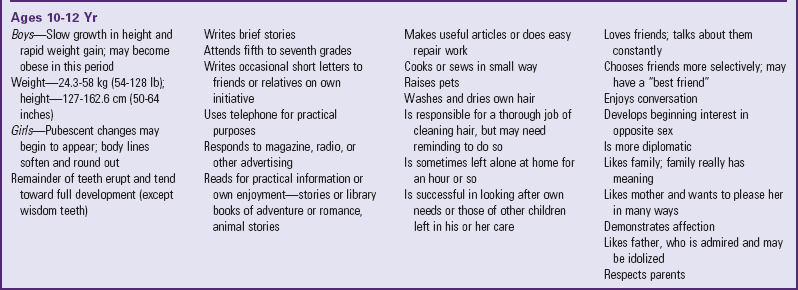

Table 17-1 presents a summary of growth and development in middle childhood. Because each child has a unique developmental pattern, any descriptions of the typical child of any age-group can represent only an average and should not be considered as absolute criteria for any given child.

Coping with Concerns Related to Normal Growth and Development

School serves as an agent for transmitting societal values to each succeeding generation of children and as a setting for many peer relationships. As a socializing agent second only to the family, school exerts a profound influence on the social development of children.

School entrance causes a sharp break in the structure of a child’s world. For some children it is their first experience in conforming to a group pattern imposed by an adult who is not a parent and who has responsibility for too many children to be constantly aware of each child as an individual. Children want to go to school and usually adapt to the new environment with little difficulty. Successful adjustment is directly related to the child’s physical and emotional maturity and the parents’ readiness to accept the separation associated with school entrance. Cooperation among parents and support for the child are successful ways of coping with school entry stress. Unfortunately, some parents express their unconscious attempts to delay their child’s maturity by clinging behavior, particularly with their youngest child.

Anticipatory Socialization

By the time they enter school, most children have a fairly realistic concept of what school involves. They receive information regarding the role of pupil from parents, playmates, and the media. In addition, most children have had experience with daycare or preschool and kindergarten.

Children’s attitudes toward school and the extent of their adjustment are strongly influenced by their parents’ attitudes. Middle-class children have fewer adjustments to make and less to learn about expected behavior because the school tends to reflect dominant middle-class customs and values, although this may be tempered by the school’s location and predominant teachers and student body. Parents who view school as a place that they have helped to create and support and that is directed toward the same objectives for socialization as their own usually prepare their children with useful anticipatory socialization and furnish them with confidence to meet the challenge. Parents who view the school as an alien culture and one that they have little, if any, power to affect may unknowingly teach their children to be fearful and resentful toward school, even though the parents agree with its purposes and objectives.

The television, which influences the acquisition of information and attitudes, also provides anticipatory socialization. Television viewing has the potential to increase a child’s vocabulary, extend the child’s horizons, and enrich the school experience. However, television relies heavily on images to convey information. Consequently, it is difficult to explore complex issues by this medium. Extensive television viewing may also encourage children to seek simple answers to tough problems and to believe that violence is the most effective and quick solution to conflict.

Although most children have had some experience with schooling before they enter the first grade, the extent to which early childhood education prepares children for primary school varies. Some preschool programs provide custodial care; others also emphasize emotional, social, and intellectual development. Early childhood programming that stresses cognitive more than social aspects appears to be more effective in facilitating later academic achievement.

Role of the Teacher

To facilitate the transition from home to school, teachers should have personality characteristics that allow them to deal with the needs of young children. Because they react to the teacher on the basis of past experience, children respond best to teachers with attributes that they would find in a warm, loving parent. As a parental surrogate, teachers in the early grades perform many of the activities formerly assumed by the parents, such as recognizing the children’s personal needs (e.g., a need to go to the bathroom or for assistance with clothing) and helping to develop their social behavior (e.g., manners).

Teachers, like parents, are concerned about the psychologic and emotional welfare of children. Although the functions of teachers and parents differ, both place constraints on behavior, and both are in a position to enforce standards of conduct. However, the teacher’s primary responsibility is stimulating and guiding children’s intellectual development as opposed to providing for their physical welfare beyond the school setting.

Teachers share the parental influence in shaping a child’s attitudes and values. They serve as models with whom children can identify and whom they try to emulate. Children seek a teacher’s approval and avoid a teacher’s disapproval. The teacher is a significant person in the life of the early school-age child, and hero worship of a teacher may extend into late childhood and preadolescence. It is not uncommon for the first or second grader to be heartbroken and tearful at leaving a familiar teacher at the end of the school term or to be upset when faced with a substitute teacher for even a short period.

Children’s interest in school and learning and much of their social interaction and self-concept are related to interactions with the teacher (Fig. 17-11). The differential systems of reward and punishment administered by teachers affect the emotional adjustment and self-concept of children and how they respond to school in general.

Fig. 17-11 School represents an important change in a child’s life, and teachers exert a significant influence on the child.

The interaction between the teacher and an individual pupil affects the pupil’s acceptance by other children, which in turn affects the child’s self-concept. Behaviors praised by the teacher usually acquire a positive value, whereas those viewed negatively by the teacher are devalued by the children. In this way the teacher exerts considerable influence in a number of areas, such as attitudes toward minority groups, the disabled, or less favorably endowed children. Teacher approval of children and their self-acceptance are closely related.

The teacher sets the emotional tone of the classroom. Those who are able to establish a positive social climate are usually concerned about the mental health and social dynamics of children. Feeling a responsibility for personality development in their pupils, they are alert and sensitive to a child’s anxieties, peer-group relationships, self-concepts, and general attitudes toward school. Learner-centered behaviors, such as supportive statements that reassure or commend children, accepting and clarifying statements that help them refine ideas and feelings to provide a sense of being understood, and constructive assistance that aids them with their own problem solving, contribute to the expansion and development of a positive self-concept.

Role of the Parents

Parents share responsibility with the schools for helping children achieve their maximum potential. Parents can supplement the school program in numerous ways (see Family-Centered Care box). Cultivating responsibility is the goal of parental assistance. Being responsible for schoolwork helps children learn to keep promises, meet deadlines, and succeed at their jobs as adults. Responsible children may occasionally ask for help (e.g., with a spelling list), but usually they like to think through their work by themselves. Excessive pressure or lack of encouragement from parents may inhibit the development of these desirable traits.

Discipline

Numerous factors influence the amount and manner of discipline imposed on school-age children: the parents’ psychosocial maturity, their own childrearing experiences during childhood, the children’s temperament, the context of the children’s misconduct, and the children’s response to rewards and punishments. Discipline serves many purposes: (1) to help the child interrupt or inhibit a forbidden action; (2) to point out a more acceptable form of behavior so that the child knows what is right in a future situation; (3) to provide some reason, understandable to the child, that explains why one action is inappropriate and another action is more desirable; and (4) to stimulate the child’s ability to empathize with the victim of a misdeed.

As children are increasingly able to see a situation from the point of view of another, they are able to understand the effects of their reactions on others and themselves. Disciplinary techniques should help children control their own behavior.

To be effective, discipline should take place in an environment characterized by positive, supportive parent-child relationships and should involve strategies that instruct and guide desired behaviors and eliminate undesired or ineffective behaviors (Towe-Goodman and Teti, 2008). Parents should not use punitive actions or corporal punishment, since these methods are of limited value and are associated with increasingly disruptive behavior in children. Negative outcomes associated with corporal punishment are discussed in Chapter 3. In particular, physically aggressive parenting practices that involve spanking are linked to children with poor psychologic adjustment, including depression, anxiety, hopelessness, and destructive behavior such as aggression and violence (Durrant, 2008). Reasoning, on the other hand, is an effective disciplinary technique for school-age children; however, use of a time-out may be necessary to stop the behavior acutely (Towe-Goodman and Teti, 2008).

As their cognitive skills advance, school-age children are able to benefit from more complex disciplinary strategies. For example, withholding privileges, requiring recompense, imposing penalties, and contracting can be used with great success. Problem solving is the best approach to limit setting, and children themselves can be included in the process of determining appropriate disciplinary measures.

Dishonest Behavior

During middle childhood, children may engage in what is considered to be antisocial behavior. Lying, stealing, and cheating may become manifest in previously well-behaved children. This is especially disturbing to parents, who may have difficulty coping with such behavior.

Lying can occur for a number of reasons. Preschool children often have difficulty distinguishing between fact and fantasy. They do not have the cognitive capacity to deliberately mislead. Sometimes they misperceive or fail to remember an event. By the time they reach school age, they still tell stories but can distinguish between what is real and what is make-believe. If not, they need to learn to distinguish between fantasy and reality. Often children will exaggerate a story or situation as a means to impress their family or friends.

Young children lie to escape punishment or get out of some difficulty, even when the evidence of their misbehavior is before their eyes. Lying is more common in families in which punishment is severe. When parents model honesty and veracity, the children will often behave in the same way. If parents lie, the children will emulate their behavior. Older children may lie to meet expectations set by others to which they have been unable to measure up. They may also lie because of low self-esteem or as a means of getting ahead or acquiring something with little effort. However, most children are concerned with the wrongfulness of lying and cheating—especially in their friends. They are quick to tell on others when they detect cheating.

Parents need to be reassured that all children lie sometimes and that they often have difficulty separating fantasy from reality. Providers should help parents to understand the importance of their own behavior as role models and of being truthful in their relationships with children. Parents can discuss the issue with the children directly to impress on them how much of their own security and respect is lost when they are not believed.