Family-Centered Care of the Child with Chronic Illness or Disability

Perspectives in the Care of Children with Special Needs

Impact of Chronic Illness or Disability on the Child

The Family of the Child with Special Needs

Assessing Family Strengths and Adjustment

Accepting the Child’s Condition and Receiving Support at the Time of Diagnosis

Managing the Condition on an Ongoing Basis

Meeting the Child’s Normal Developmental Needs

Meeting Developmental Needs of Other Family Members

Coping with Ongoing Stress and Periodic Crises

http://evolve.elsevier.com/wong/ncic

Birth of a Child with a Physical Defect, Ch. 11

The Child with Cognitive, Sensory, or Communication Impairment, Ch. 24

Childhood Morbidity, Ch. 1

Communicating with Families, Ch. 6

Developmental Assessment, Ch. 6

Discharge Planning and Home Care (High-Risk Newborn), Ch. 10

Facilitating Parent-Infant Relationships (High-Risk Newborn), Ch. 10

Family-Centered Care, Ch. 1

Family-Centered Care of the Child During Illness and Hospitalization, Ch. 26

Family-Centered End-of-Life Care, Ch. 23

Family-Centered Home Care, Ch. 25

Family Structure, Ch. 6

Health Promotion: Infant, Ch. 12; Toddler, Ch. 14; Preschooler, Ch. 15; School-Age Child, Ch. 17; Adolescent, Ch. 19

School Phobia, Ch. 18

Social, Cultural, and Religious Influences on Child Health Promotion, Ch. 2

Perspectives in the Care of Children with Special Needs

Significant changes in the health care system have increased the need for services and benefits to children with chronic illness or disability (Stein, Shenkman, Wegener, et al, 2003). A major obstacle in the effort to provide these services has been the issue of how best to define populations of children with chronic conditions. For many years a number of terms have been used to classify and describe children with special health care needs (Box 22-1).

More recently there has been a drive to develop a definition of children with special health care needs that could be used by federal and state programs to facilitate planning of comprehensive, family-centered, community-based services for this population (Jackson, 2009; Beers, Kemeny, Sherritt, et al, 2003; Miller, Recsky, and Armstrong, 2004). To date, children with special health care needs, as defined by the federal Maternal and Child Health Bureau (Msall, Avery, Tremont, et al, 2003), are “children who have or are at increased risk for a chronic physical, behavioral, developmental, or emotional condition and who also require health and related services of a type or amount beyond that required by children in general.”

Each year in the United States, 6 million children ranging from newborns to 17-year-olds are hospitalized for a variety of conditions, and the average length of stay for those patients is approximately  days (Weiner, 2008). Advances in biomedical science and technology have resulted in dramatic improvement in the health care of pediatric chronic conditions (Varni, Limbers, and Burwinkle, 2007). There is now improved management of infectious diseases, identification of children with previously unrecognized illnesses, and implementation of preventive and public health measures (Jackson, 2009). With these medical advances and decreasing patient lengths of stay, many more patients are requiring care in the home setting. The burden of care is then carried by the family and outpatient care facilities to provide services required.

days (Weiner, 2008). Advances in biomedical science and technology have resulted in dramatic improvement in the health care of pediatric chronic conditions (Varni, Limbers, and Burwinkle, 2007). There is now improved management of infectious diseases, identification of children with previously unrecognized illnesses, and implementation of preventive and public health measures (Jackson, 2009). With these medical advances and decreasing patient lengths of stay, many more patients are requiring care in the home setting. The burden of care is then carried by the family and outpatient care facilities to provide services required.

For example, the median life expectancy of children with cystic fibrosis today is more than 30 years, in contrast to 5 years in 1955. In 1955, 90% of children born with spina bifida died in infancy. Today 90% survive infancy and have a normal life expectancy if they have appropriate and timely medical intervention such as improved surgical advances and management of urinary tract infections (Jackson, 2009). In addition, advances in combination antiretroviral therapy have resulted in a decreased mortality rate for children infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (Fahrner and Mario, 2009; Yogev and Chadwick, 2007). Infants with very low birth weight and extreme prematurity are living longer (Jackson, 2009), and more than 80% of children diagnosed with cancer today will be cured of their disease (Gurney and Bondy, 2010; Horner, Ries, Krapcho, et al, 2008).

The dramatic decline in mortality rates has led to an increase in the number of children with special health care needs and has implications for the provision of comprehensive, long-term health care services for these patients (Jackson, 2009; Palfrey and Richmond, 2005). Chronic illness has surpassed acute illness as the major health concern for children (Perrin, Bloom, and Gortmaker, 2007). In the United States an estimated 18% of children (12.6 million) have a chronic illness or disability that requires health care services beyond those usually required by children (Perrin, Bloom, and Gortmaker, 2007; Arango, 2005; Newacheck, McManus, Fox, et al, 2000).

The most common chronic childhood conditions causing disability are respiratory diseases (primarily asthma), impairments of speech and sensory functions, and mental and nervous system disorders (Arango, 2005). Asthma is the single most prevalent cause of disability in children and has been largely responsible for much of the recent increase in childhood disability. Mental and nervous system disorders account for about one sixth of all childhood disability. The prevalence of disability is higher in boys, in children older than 5 years of age, and in children from single-parent and low-income families (Newacheck and Halfon, 2000; Schiller, Adams, and Nelson, 2005).

The impact of chronic illness and disability on children’s health and functional status is profound. Children with disabilities spend three times as many days ill in bed and days absent from school as other children. They make 26 million more visits per year to the physician than typical children and spend 5 million more days in the hospital annually (Arango, 2005). They are limited in their daily activities for slightly more than 2 weeks each year, and one tenth of all children with disabilities are unable to play or attend school (Arango, 2005). In addition, children with disabilities are more likely to be a victim of emotional or sexual abuse, have behavioral problems, drop out of school, and be involved in the juvenile justice system than are their peers without disabilities (Perrin, Bloom, and Gortmaker, 2007).

Chronic illness and disability have substantial effects on family functioning. Chronic conditions present most families with additional tasks, responsibilities, and concerns such as the additional caretaking needs of the child, identification of and access to educational and medical services, payment for services, uncertainty about the future, emotional grieving, stigmatizing reactions from the community, social isolation, and lost social opportunities. These demands can be grouped according to their personal impact on a parent, the financial impact on the family, and the impact on social and family relationships.

Parents are caught in a juggling act of meeting their child’s normal growth and development needs and dealing with the consequences of the chronic illness (Sullivan-Bolyai, Knafl, Sadler, et al, 2004). Parents of children with disabilities are more likely to report depression than parents of children without disabilities (Sullivan-Bolyai, Sadler, Knafl, et al, 2003). Family members of children with disabilities are more likely to experience behavioral and psychologic symptoms. Parents may miss days from work, experience financial strain, and be challenged both physically and emotionally while they deal with caring for a child with a chronic illness or disability. Siblings may experience a wide range of feeling and concerns and often have to identify and deal with these concerns in the absence of the parent, who is either physically separated or emotionally unavailable to the well sibling (Pearson, 2005). Frequently, siblings’ lives reflect the routines imposed by the affected child’s chronic condition.

The increased prevalence of chronic illness and disability in children and the far-reaching effects on the child and family members have many implications for nursing. Nurses need to take an active role in early screening, case finding, and assessment and provide supportive and educational interventions that decrease the disruptive effects of the chronic condition on the child and family members. In addition, nurses should attempt to prevent disabling conditions by removing their known causes; this entails encouraging adherence with immunization programs, identifying infants and mothers at risk, recognizing the disability early, fostering injury prevention programs and policies, and providing innovative health education programs. Skilled case management is necessary to ensure that the family of a child with special needs has the support to successfully adapt to the consequences of the child’s chronic condition. This includes providing community-based, comprehensive, and culturally appropriate care to the child with special needs (McPherson, Weissman, Strickland, et al, 2004).

Trends in Care

Because of advances in technology, economic effects, and the demand for more meaningful models of care, care has changed not only in the types of services and care children receive, but also in where services are provided and by whom.

Developmental Focus

Using a developmental approach rather than one based on chronologic age when caring for children with special health care needs helps the nurse to determine where children are at present and to understand their response to the chronic illness or disability. Developmental changes in the child continue despite the added stress of coping with a chronic illness. The chronic condition imposes a dimension of behavioral and developmental risk (Rittey, 2003). Because children with chronic conditions are more alike than different, a noncategorical approach emphasizing the commonalities of these children, rather than solely the illness, is beneficial. Referring to children by the names of their disabilities or illnesses affects professional and parental attitudes, as well as the assessment of the child’s present abilities and future expectations (Green, 2003). Therefore parents and the health care team should work jointly for the benefit of the child who has an illness rather than allowing the illness to define the child. Knowledge of the developmental theory perspective is paramount in providing the support necessary for children to successfully adjust to a stressful life experience such as a chronic illness or disability.

Family Development

A developmental approach also includes an assessment of family development. The family life cycle focuses on the changing ages and developmental tasks of both children and adults and on the changing external demands as the family grows older. Families are expected to accomplish certain tasks at various stages (e.g., finding, furnishing, and maintaining their first home during the married couple stage). A diagnosis of chronic illness in a family member has a profound effect on every member of the family unit (Sullivan-Bolyai, Sadler, Knafl, et al, 2003). As with individual development, family development may be interrupted or even regress to a previous level of functioning. For example, having a child with a chronic illness may impose an added stress on the newly married couple who are in the midst of establishing a family identity. Nurses can apply family developmental theory when planning interventions for families of children with special health care needs. (See Developmental Theory, Chapter 3.)

Family-Centered Care

Family-centered care is paramount in the care of children with special health needs. Over the past 40 years significant changes have occurred in parents’ responsibilities for providing and coordinating the care of their ill child. Today families of chronically ill children have comprehensive and complex caretaking responsibilities in the hospital and at home (Sullivan-Bolyai, Knafl, Sadler, et al, 2004).

The increasing numbers of chronically ill children and the families who are assuming the major burden of coordinating their children’s care have reinforced the demand for new approaches in the health care system. The outcome has been the emergence of family-centered care to reflect, recognize, and facilitate the changing roles of families in care delivery. Because a cure is not likely for a number of chronic conditions, health care professionals must focus their efforts on care.

The federal legislation Public Law (PL) 99-457, which affords states the opportunity to extend the benefits of PL 94-142 (Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975) to children from birth to age 5 years, targets family-centered care. This legislation establishes a process whereby families become active participants in decision making about the care of their children.

The goal of care is to minimize the manifestations of the illness and maximize the child’s cognitive, physical, and psychosocial potential. Advocating a family-centered approach to care facilitates attainment of this goal (Vessey and Mebane, 2009). (See Family-Centered Care, Chapter 1.) Integrating family-centered care in practice requires health professionals to (1) acknowledge and respect the family’s individuality and strengths, (2) foster the family’s competence and confidence in caring for the child, and (3) empower the family to advocate for the child when dealing with the health care system (Vessey and Mebane, 2009). In the family-centered framework, consistent attention is given to the effects of the child’s chronic illness on all family members, not only on the affected child. This is paramount, because the best predictors of the well-being of children with special health needs include factors associated with family functioning.

As parents become knowledgeable about their child’s special health needs, they frequently become experts in providing care. As part of the health care team, nurses are adjuncts in the child’s care and need to build alliances with parents, respecting and drawing on their expertise. One of the key principles in family-centered care is the involvement of family members in decision making about their child’s physical care. Collaboration—consistent sharing of information about the illness, responsibility, and decision making—is necessary to establish effective and trusting partnerships with parents.

Care conferences with the child’s family and members of the health care team, including nurses, offer opportunities for mutual sharing of thoughts and concerns about the child’s care. Being attentive the parent’s observations helps assure them that their role is valued and their opinions important.

In fostering effective family-centered care, the nurse not only acknowledges that the family is a key component of the child’s care and illness experience but also recognizes and respects the family’s expertise in caring for the child within and outside of the hospital milieu. In the absence of the child’s family during hospitalization, the nurse should try to maintain routines established by the family. In the family’s presence, the nurse, child, and parent form a relationship in which the process of care negotiation occurs. This relationship is pivotal to the needs of the child and family and is where roles are defined and guidelines are developed. Through open communication, the nurse values the parents’ roles by viewing them as the ultimate experts in caring for their child. Simultaneously the family looks to the nurse for empowerment, support, education, and expertise in caring for their child (Fazil, Wallace, Singh, et al, 2004; Sullivan-Bolyai, Knafl, Sadler, et al, 2004).

Normalization

Normalization refers to establishing a normal pattern of living (see Nursing Care Guidelines box, p. 855). Normalization occurs on several levels. It implies child and family access to services in as usual a fashion and environment as possible, with a focus placed on the home and community. Application of the principles of normalization means that daily routines for the child with illness or disability should be fitted to the family’s schedule, rather than vice versa. Age-appropriate expectations for the child’s behavior should be applied. As necessary, the environment should be structured to encourage the child’s engagement in age-appropriate activities. Thus consequences of the illness are minimized, and the child and family live as normal a life as possible given the disability.

Nurses can facilitate the normalization process for families of children with special needs by acknowledging their normalcy, strengths, and weaknesses. Being supportive of the child’s illness and treatment and actively including the family in all aspects of the care will improve their self-esteem and promote further development (Shepard and Mahon, 2009).

Home Care

Along with the trend toward normalization, there has also been a trend of earlier discharge of children from acute or chronic care facilities to the family and community. Home care refers to the return to a system and set of priorities whereby family values are as significant in the care of a child with a chronic illness as they are in the care of healthy children. The primary incentive for home care of children with special health needs was a parental need to keep these children at home and professionals’ willingness to work with families to attain this goal. The goal of home care is to:

• Normalize the life of the child with special needs, including the child with technologically complex care, in a community and family setting

• Lessen the disruptive impact of the child’s condition on the family

With appropriate support and training, families today can accomplish complex treatments and procedures in the home. Parents are challenged to maintain a homelike setting in the midst of ventilators, monitors, and other sophisticated equipment. Throughout this text home care is discussed as appropriate for specific conditions. Chapter 25 focuses on family-centered home care; the process of transition from the hospital to the home setting is described in Chapter 26.

Mainstreaming

Mainstreaming refers to a process of integrating children with special needs into regular classrooms and child care centers. Attending school allows these children to acquire a sense of self and understanding of their place with respect to their peers. It also provides important opportunities for socialization with nondisabled children, which enables the latter group to develop respect for and acceptance of their peers with special needs. A crucial developmental task for children 5 years of age and older is to move beyond the family environment into the school community, where social competence, academic achievement, and regular attendance are important goals (Vessey and Jackson, 2009). A variety of supplemental programs exist in the school system to accommodate children with special needs and thereby afford them equal educational opportunity.

For the most part this change facilitating normalization for these children has resulted from the passage of PL 94-142, the Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975, which provides children with “free and appropriate public education,” including special education and related services, rendered at public expense, under public supervision, and without charge, that meet the standards of the state educational agency (Vessey and Jackson, 2009). The 1990 amendment to this law, PL 101-476, changed the name of the act to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). Passage of PL 101-476, along with current federal child care mandates and increasing public concern about child care, demonstrates a national commitment to the concept that early services are crucial if children with disabilities are to achieve their full potential. In December 2004 PL 108-446 was passed, resulting in a major reauthorization and revision of IDEA. This reauthorized state and local aid for special education and related services for children with disabilities, specifically in development and maintaining early intervention programs for infants and toddlers with disabilities.

PL 94-142 requires states to identify, diagnose, teach, and provide related services to children with disabilities from 5 to 18 years of age. In 1977 the age range was extended to include children 3 to 21 years of age, with services for children ages 3 to 5 years optional. In accordance with this law, a multidisciplinary team writes an individualized education program (IEP), which includes specific therapeutic and educational goals and strategies for each eligible child referred for special education. Parents may intervene in educational decisions and have the right to a hearing when they believe the team’s decision is harmful or inappropriate. Because many parents are unaware of this or other laws providing rights for disabled children, it is imperative that nurses inform them of what the laws are and where to obtain information. Nurses may also be involved in formulating IEPs.

Early Intervention

Early intervention includes any systematic and sustained effort to assist young, disabled, and developmentally vulnerable children from birth to 3 years of age. PL 99-457, the Education of the Handicapped Act Amendments of 1986, directs states to develop and enact statewide coordinated, comprehensive, multidisciplinary interagency programs of early intervention services for infants and toddlers with disabilities, in addition to support services for their families.

An important component of the law’s implementation is the individualized family service plan (IFSP). As a product of collaboration between professionals and families, the IFSP consists of information relating to the infant’s or toddler’s current level of development, family needs and strengths for improving development, main outcomes anticipated, services required, designation of a case manager, and transition steps to preschool services. All outcomes and services concern the needs of the child and family. The IFSP represents a commitment to families and children that their strengths will be acknowledged and built on, that their needs will be satisfied in a manner that respects their values and beliefs, and that their aspirations will be fostered and empowered.

Nurses can provide many services for children covered by PL 99-457. Implementation of family-centered care and clinical expertise in practice provide nurses with a role in early identification and assessment of children at risk for disability, in multidisciplinary assessment, and in case management. Nurses can assess children in preschool settings, implement ongoing staff and patient education, coordinate care with the heath care team, become actively involved in community nursing networks, and develop health promotion programs for school personnel and family members.

Managed Care

Managed care health plans have become the primary form of health care coverage in the United States (Jackson, 2009; Smucker, 2001). An evaluation of out-of-pocket expenditures for insured versus uninsured children with special health care needs revealed higher out-of-pocket burden and financial problems among the uninsured (Jeffrey and Newacheck, 2006). Not only has managed care expanded rapidly, particularly for Medicaid-eligible patients, but the roles and responsibilities of state Title V programs for children with special health needs have changed as well (McPherson, Weissman, Strickland, et al, 2004; Inkelas, 2005). Provision of direct services by specialty clinics funded through Title V were reduced while managed care systems attempted to provide services to children within the managed care organization.

Implementing managed care for children with disabilities differs from providing care for adults with disabilities in three ways (McPherson, Weissman, Strickland, et al, 2004): (1) the changing dynamics of child development affect the needs of these children at various developmental stages and change their anticipated outcomes; (2) the prevalence and epidemiology of childhood disabilities, with few common conditions and many low-incidence or rare ones, vary considerably from those of adults, for whom there are many common conditions and few rare ones; and (3) because of children’s need for adult guidance and protection, their development and health rely heavily on their families’ socioeconomic status and health. These differences have implications for monitoring care provided to children with chronic conditions in managed care settings. The diverse effects of managed care on these children are seen in seven major domains: access to care, use of services, quality of care, satisfaction with care, cost of care, health outcomes, and family impact (Newacheck, Hung, and Wright, 2002; van Dyck, Kogan, Heppel, et al, 2004).

Families offer four basic suggestions for improving services for their children with chronic conditions: (1) reduce barriers to programs and services; (2) improve the quality of services; (3) improve the training given to families, health care professionals, and the community relating to chronic conditions and their management; and (4) increase the availability and quality of community-based services (van Dyck, Kogan, Heppel, et al, 2004). All of these suggestions require two factors: universality of care and adequate funding (Vessey and Jackson, 2009). Health care providers play an important role in working jointly with the leaders of managed care programs to ensure high-quality care for children with chronic conditions.

Cultural Issues

Increasing migration around the world in the past 10 years has led to heterogeneity in many nations, including the United States. For this reason, cultural competence is an important goal of nursing practice.

For many minority and ethnic populations, cultural understanding of disability and illness, social roles for disabled individuals, the structure of family life, and other factors associated with the perception of children vary from those of “mainstream” American culture. These factors may affect family choices regarding the care of the child with special needs.

Although culture cannot fully define how an individual will act and think, knowledge of cultural perspectives can assist nurses in anticipating and understanding why families make certain decisions. Cultural attributes, including beliefs and values concerning disability or illness and its causes, family structure, social roles for the disabled, the role of children, childrearing practices, spirituality, and time orientation, also influence a family’s reaction to a chronic condition. Although eliciting health beliefs and negotiating interventions can be challenging, it is necessary for compliance, collaboration, patient/family satisfaction, and optimal care (see Nursing Care Guidelines box).

Recognizing the growing cultural diversity in our society, nurses must incorporate cultural competence in their clinical practice to promote delivery of effective and sensitive care to children with chronic illness and their families. Care should be consistent with the cultural practices and beliefs of the child’s family whenever possible; increasing cultural competence will improve communication and promote respect for human diversity (Rehm, 2009) (see Cultural Competence box).

Impact of Chronic Illness or Disability on the Child

A child’s reaction to chronic illness or disability depends largely on his or her developmental level. Knowledge of developmental stages is essential for nurses to understand how children interpret events. Because children’s cognitive abilities change as they grow, they require varied explanations of their chronic illness as they mature. Normal development should occur in the context of the child’s temperament, intelligence, motor skills, and relationships with family and friends. Identifying the child’s coping strategies and promoting successful adaptation to the illness are essential. Factors influencing coping include the developmental stage, age, gender, type and duration of illness, and family cohesion (Schmidt, Petersen, and Bullinger, 2003). Caring for the child involves health education efforts, normalization principles, and assistance to the growing child in planning realistic future goals.

Promoting Normal Development

Normative developmental tasks throughout childhood center on developing a sense of self and acquiring autonomy in all areas of life (Turkel and Pao, 2007). The impact of a chronic illness or disability on a child is affected by the child’s age at the onset of the illness or disability (Vessey and Mebane, 2009). Chronic illness can affect children of all age-groups, although each age-group faces its own specific challenges. Children redefine their illness and its implications as they develop and grow. Accordingly, nurses must plan and implement care that promotes the child’s successful progression from one stage of development to the next.

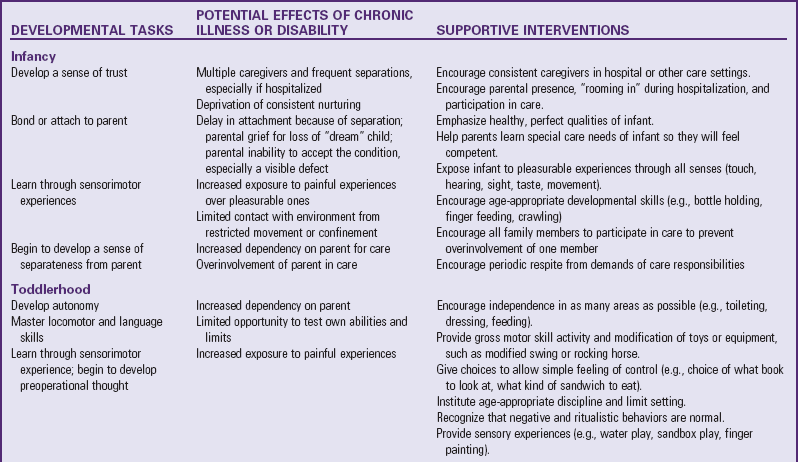

In addition to learning about the illness and its effects on the child’s abilities, the family needs to acquire strategies to promote appropriate development in their child. Even with delays in achievement of developmental milestones, nurses need to be instrumental in teaching parents how best to help their child reach his or her developmental potential (Vessey and Mebane, 2009). Table 22-1 describes developmental aspects of chronic illness or disability in children and accompanying supportive interventions.

Infant

During infancy the child is establishing trust and learning about the environment through sensorimotor exploration (Vessey and Mebane, 2009). However, the diagnosis of a chronic illness, accompanied by a disruption in routines and physical discomfort, may compromise the dependability and consistency of an infant’s environment and hinder the development of basic trust. Disability or chronic illness frequently impairs the child’s motor abilities, restricting the child to a crib and decreasing contact with the environment. Illness may influence the infant’s growth and developmental parameters by its effects on mobility, sleeping, feeding, and sensory functions. Separation of infant and parent as a result of frequent hospitalizations may prevent attachment and the emergence of a trusting relationship for the infant.

For the infant with a painful illness, exploration of his or her environment is restricted, which further curtails development (Vessey and Mebane, 2009). Messages transmitted to infants about their bodies are affected by the amount of pain and discomfort they experience. Associating pain with touch can lessen the infant’s ability to give and receive affection. Lack of pleasant sensations can result in an irritable and unhappy child. Parents may interpret this behavior as indicative of their inadequacy in satisfying the child’s emotional and physical needs, which further affects the parent-child relationship and the development of trust. Illness may threaten the parents’ feelings of confidence and competence in their newly acquired parenting roles.

The presence of a visible or serious defect can hinder parental attachment while the parents mourn the loss of the perfect child. They may gain little comfort from trying to satisfy their child’s basic needs despite their best efforts. Physical deformity or fatigue may influence a child’s responsiveness to his or her parents, who may in turn react differently to their child. A poor prognosis for the child may cause some parents to emotionally detach themselves from their infant to protect themselves from future emotional pain (Vessey and Mebane, 2009).

Nurses can be pivotal in helping parents care for their infant with special needs. They may need assistance in learning how best to meet their infant’s needs, for example, how to hold a flaccid or rigid infant, how to comfort an irritable infant, how to feed a child with dyspnea or tongue thrust, or how to stimulate a child unable to develop common skills.

Nurses should advocate for practices and policies that support the developmental needs of the infant and the family. Twenty-four-hour visitation in the neonatal intensive care unit and other infant units is paramount and lessens the infant’s experience of separation. In addition, nurses need to limit the number of caregivers for the infant to enhance consistency and continuity of care. Showing parents how to hold and touch their infant will foster their competence and confidence. Kangaroo care (with skin-to-skin contact) has been demonstrated to be both beneficial and safe for the infant. (See Chapter 10.) Give support to mothers who want to breast-feed, and provide a private room with refrigerated storage for the woman who pumps or nurses. Promote sibling visitation as well.

Toddler

The toddler is acquiring a sense of autonomy, developing self-control, and forming symbolic representation through language acquisition. The need for parental involvement in managing the child’s illness may interfere with the toddler’s need for increasing independence and impede his or her sense of autonomy and self-control. Mobility is possibly the primary tool used by the toddler to experiment with attaining control. For the toddler who is incapacitated, a sense of helplessness results that is difficult to overcome at a later time.

If a child’s chronic illness prevents daily activities, this may impede autonomy in tasks such as feeding, toileting, and building larger social networks. Developmental tasks that have just been mastered are often easily lost in the toddler suffering from an acute exacerbation of the illness. Behavioral regression, commonly seen in toddlers, is worsened by stress related to pain and separation.

Because of the toddler’s desire for autonomy, the mastery of language and locomotor skills is very important. The child learning to talk and walk progresses toward being a separate individual, both psychologically and physically. A toddler’s limited ability to verbally communicate thoughts and feelings makes it especially difficult for the child to cope with the stresses imposed by a chronic illness. In the presence of disability or illness, mobility to explore and master the environment is impeded, and the child is prevented from acquiring these skills. Within the constraints of the illness or disability, the nurse should help parents provide safe opportunities that foster independence in these and other areas for their toddler, both at home and in the hospital (Fig. 22-1).

Fig. 22-1 Wheelchairs designed for children can help a child with disabilities gain mobility and promote growth and development.

Illness can impose separations that cause anxiety in the toddler. A disability or chronic illness can entail frequent painful procedures and hospitalizations. The latter may hinder the normal development of trusting relationships within the family. If the hospital does not help maintain the parent-child relationship, the child may become depressed and eventually detach from parents. Children appear to have a great ability to withstand stress as long as they retain their attachment to the parent.

Toddlers are especially sensitive to changes in familiar routines, in addition to hospitalizations. They may perceive disruption of normal daily activities and hospitalization as punishment. If invasive and painful medical procedures are required in the treatment of the child’s illness, this perception is further validated. Therefore encourage parents to bring in familiar toys for the toddler during hospitalization, and establish routines so the child can become acclimated.

Parents of toddlers may seek out daycare or respite care, which can be difficult to find for the child with special needs.* Caregivers need time away from caring for their child to allow for their own growth and development. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) requires that daycare providers make “reasonable modifications” for equal access to program participation (Mahoney, Wheeden, and Perales, 2004). Special medical daycare facilities are emerging in some areas (Mahoney, Wheeden, and Perales, 2004).

Preschooler

The preschooler is focused on acquiring a sense of initiative to successfully meet the challenges of his or her growing world. Preschoolers with a chronic illness may lack the resources or energy to plan and engage in such activities; thus opportunities for building social relationships, learning about the environment, and developing a sense of purpose and self-confidence are often limited. Illness may restrict the preschooler to the home and cause the child to fall behind in social skills beneficial in school or group settings.

It may be difficult for preschoolers to build a healthy sexual identity and body image, especially if most of their body awareness is linked with pain and disability. Children’s understanding of their body is confined to what they see, feel, and use. In the presence of a chronic illness, their body awareness may be focused on the anxiety and pain elicited. The chronically ill child may lose control over newly acquired bowel and bladder function, which results in feelings of embarrassment and inferiority. The child with a disability may find it difficult to form a mental image of impaired body parts, for example, paralyzed extremities. This poorly developed sense of body integrity causes children to be particularly fearful of mutilating or intrusive experiences, which can occur frequently during a lengthy illness. Thus before any medical procedure children should be given a brief, honest explanation of what the procedure is, how it will be performed, and the duration and intensity of any accompanying pain.

When the young child has a disability that affects motor development, there is the risk of shifting to development of compensatory intellectual pursuits before the child is ready. This could compromise attainment of initiative and autonomy and place the child at risk for emotional problems. Thus intervention must focus on providing activities that allow maximum motor development. For example, if a child has paraplegia, it is not enough to strengthen the upper extremities to compensate for the lower ones. Rather, the activity must consider the child’s need for a sense of control over the body, social interaction, feeling of achievement and competence, and outlet for aggression. Appropriate activities may include ball throwing; play with building blocks; water and swimming activities such as bubble blowing, splashing, and racing; or pounding with a hammer.† Children with disabilities may be able to ride a tricycle with minor changes such as self-adhering straps to protect the hands or feet.

One of the more crucial effects of chronic illness or disability on preschoolers is the feeling of guilt that they “caused” the illness through an imagined or real misdeed. This is less of an issue if the child is born with the condition than if it occurs during the preschool period. Such guilt can significantly affect the child’s developing but fragile self-esteem, especially if the child experiences frequent insults. In contrast, the child with a temporary physical disability has added opportunities for attaining mastery and overcoming feelings of inferiority and guilt. Structuring situations to foster success can assist a child in developing a sense of confidence and competence.

Another critical component for normal child development is discipline. Discipline is essential to the child’s sense of security because boundaries are necessary for the child to test behavior. It also teaches the child socially acceptable behavior. Applying appropriate discipline to the child who is chronically ill or disabled can also limit the resentment and hostility that can develop among siblings if parents apply different standards to each child. The nurse’s responsibility is to help parents learn successful methods of guiding the child.

When a chronic illness imposes restrictions that cause difficulty with mastery, it can inflict a lasting sense of failure. Preschoolers are egocentric and have naive reasoning, which may affect their interpretation and understanding of their illness.

Because preschoolers need to explore and acquire experience with pretend situations and objects before they really experience them, nurses need to facilitate opportunities for imaginative play (e.g., using dolls and syringes) and to give simple answers to children’s questions about their illness and treatment.

School-Age Child

School-age children focus on increasing mastery over their environment and independence. A lack of physical stamina may prevent the child with a chronic illness from engaging in school and extracurricular activities and result in feelings of inferiority or inadequacy. These activities help the child acquire social skills, develop a sense of achievement, gain the skills to achieve self-sufficiency, and learn to effectively deal with stress. School-age children should be involved as much as possible in their own care and in decision making about their treatment to facilitate their sense of control and mastery.

School-age children are mostly concerned with learning to take initiative. School initiates the processes of working toward independence from parents, gaining academic skills, and building peer relationships. Along with the family, school is the major context in which children develop their sense of self and understanding of their place relative to their peers.

During the school-age period, the child is increasingly able to distinguish fantasy from reality, self from others, and he or she advances to inductive reasoning and beginning logic. Coupled with this limited sense of causality comes a deeper understanding of differences. Children with an illness that is not obvious may try to hide its existence once they realize that it differentiates them from their peers (Vessey and Mebane, 2009).

School-age children also begin active inquiry. They are usually verbal regarding their condition and ask for information about all phases of the illness and treatment. In addition, they experience pride after they learn the correct label for the illness, treatment, and medication. From the beginning, nurses should respond to the child’s questions in a simple, direct manner.

The school-age child separates from parents more easily and becomes more active in peer relationships. Peers strongly influence school-age children’s opinions of themselves and their self-esteem (Murray, 2000). If not provided with the required skills to disseminate information about their illness to peers, school-age children may withdraw with a diminished self-concept (Vessey and Mebane, 2009).

The number of children with chronic illnesses who return to school continues to increase (Kliebenstein and Broome, 2000). Children need preparation before entering or resuming school. Having a tutor in the hospital or home as soon as children are physically able helps them realize that school will continue and gives them time to consider this prospect. They need to investigate possible answers to the many questions others will ask. One method of anticipatory preparation is to role-play, with the child as the “returned pupil” and the nurse as “other schoolmates.” The nurse asks questions about the reason for the child’s absence, the name of the disease, and so on. The child is provided with a safe opportunity to explore possible answers and to experience some of the possible reactions of others. If the child returns to school with some obvious physical change, such as hair loss, an amputation, or a visible scar, the nurse might also ask questions about these alterations to prompt preparatory responses from the child.

Initially the child may find it easier to attend half-day school sessions or to participate in a limited number of activities. It is preferable to plan the school program with as much participation and leadership from the child as possible. Once the child returns, regular assessments of the child’s progress in various areas (academic, social, physical) are essential to ensure a satisfactory adjustment.

Classroom peers also need preparation, and a joint plan involving the schoolteacher, nurse, parents, and child is best. At a minimum the classmates should be given a description of the child’s condition, prepared for any visible changes in the child, and allowed an opportunity to ask questions. The child should have the option to attend this session. As the child’s condition changes, particularly if the illness is potentially fatal, school personnel, including the students, need periodic apprisal of the child’s status and preparation for what to expect. (See Chapter 23.)

Children with special needs should maintain or reestablish relationships with peers and to participate according to their capabilities in any age-appropriate activities. Alternative activities may be substituted for those that are impossible or that place a strain on their health. It is important for these children to have the opportunity to interact with healthy peers, as well as to engage in activities with groups or clubs composed of similarly affected age-mates. Such organizations as ostomy clubs, diabetic clubs, and cerebral palsy groups share information and provide support related to the special problems the members face.

Programs such as the Special Olympics (www.specialolympics.org) offer children with physical disabilities an opportunity to compete with their peers and to achieve athletic skill. Summer camps* also provide children unique opportunities to associate with similarly affected peers and to develop a wide variety of skills, including increased independence in activities of daily living and self-care associated with their condition. With creativity, parents can make many adaptations in children’s environments to increase their mobility and independence.† Technology is rapidly advancing, especially in the application of computers, and parents should be directed to the latest developments that may help their child.

Children with special needs obtain enormous benefits from expressive activities, such as art, music, poetry, dance, and drama. With adaptive equipment and imagination, children can participate in a variety of activities. Organizations such as VSA (vision, strength, and artistic expression) arts* encourage children to celebrate and share their accomplishments.

Adolescent

Adolescence marks the transitional period from childhood to adulthood and is characterized by important changes in intellectual, physical, social, and psychologic growth and development. Adolescence is the time for achieving independence. This may be difficult for adolescents with chronic illness, especially those who are dependent on others for daily care or therapy.

Chronic illness may impose the additional burden of hospitalization, pain, surgery, extensive diagnostic testing, medications, school absences, and activity restrictions on the adolescent. Such stressors may provoke many anxieties, fears, and grief reactions. Illness-related fears include loss of physical integrity, inability to separate successfully from one’s parents, loss of control, being different from peers, and death. They must cope not only with complex normative developmental tasks but also with the stress related to the diagnosis and treatment of life-threatening or long-term illness (see Research Focus box).

Adolescents are striving for autonomy, which is threatened by the forced dependence, need for compliance, and loss of control associated with an illness and treatment. Consequently, dealing with the illness may be more difficult and adolescents may be at greater risk for depression, anxiety, and adjustment problems. Many adolescents wish to assume total responsibility for their care despite their inexperience; however, their extensive care needs may prevent this from occurring (Newacheck, Wong, Galbraith, et al, 2003). If the chronic illness is associated with mobility limitations forcing dependence on caregivers for basic needs, it may compromise the emergence of a secure sexual and physical identity and peer relationships.

Adolescence is a time for achieving independence from the family and planning for future goals and responsibilities. Adolescents with long-term chronic illness may be less future directed and less independent than well peers. Enforced dependency from physical impairment can exacerbate the parent-child conflicts surrounding independence. Lack of understanding by both parties can result in bitter feelings and intrafamilial turmoil. The tendency toward rebellion may be directed at the disorder and reflected in decreased compliance with treatment; denial of the disorder to preserve a sense of normalcy with peers; and risk-taking behavior that can place the teenager in jeopardy, such as driving a car despite a disorder that increases the chance of an accident. Such behaviors can further strain an already tense parent-child relationship.

On the other hand, parents can promote independence by giving the adolescent a greater role in his or her own treatment regimen, encouraging the adolescent to develop a relationship with the physicians and nurses that is not mediated by parents, and promoting normalization principles.

During adolescence hormonal changes accompany the onset of puberty and a simultaneous preoccupation with body image. The major task of the adolescent is to develop his or her own identity. Hormone-related changes must be integrated into the self-image while the adolescent is gaining mastery and control over sexuality and increased physical abilities. During early adolescence this process occurs mostly within the peer group. The beginning of puberty, a period of uncertainty and rapid change, is even more confusing for teenagers with chronic illnesses.

Most adolescents are embarrassed by their appearance and emerging sexuality. For chronically ill adolescents the illness or its treatment may be most embarrassing and may influence their body image and hinder their sense of mastery and control over a changing body. It is difficult for the adolescent with a disability to incorporate the disability into a changing self-concept and body image. The young person who has a disability or is diagnosed with an illness during the critical adolescent years has more difficulty accomplishing these tasks than does the adolescent who has been affected since childhood. The earlier the onset of a limiting illness, the better the individual is able to adjust to it. The youngster with a newly acquired condition has the added task of grieving the loss while adapting to the changes occurring as a natural course of events. The adolescent often feels rejected because of personal appearance or inability to participate in activities expected of a healthy teenager.

Adolescence is a most difficult period to be seen as different by one’s peers, and some adolescents may withdraw from social relationships and activities that foster healthy psychosexual development. Appearance, abilities, and skills are highly regarded by peers; an adolescent who is limited in any of these qualities is subject to rejection by this influential group. A sense of feeling different from peers can cause isolation, loneliness, and depression. To be accepted by peers, some adolescents may decide to participate in risky behaviors such as unprotected sex and smoking, despite the possible harmful effects. Participation in groups of teenagers with chronic illnesses or disabilities can alleviate feelings of isolation and ease the transition to a meaningful relationship with one person in adulthood.

The topic of sexuality related to the effects of the illness is an important concern of adolescents, although they seldom initiate a discussion of this sensitive subject. Discuss any likely interference in sexual function due to the disability candidly and openly with the adolescent. Unfortunately, many nurses are reluctant to discuss sexual issues with teenagers. Adults often underestimate the degree to which adolescents participate in unrealistic fantasies about sexual activities and related matters, or even in sexual activity itself.

Nurses can facilitate the adolescent’s striving for autonomy by allowing and encouraging the adolescent’s participation in medical decisions by signing an assent as part of the informed consent document. Within the confines of the specific treatment center, the adolescent can be given control over the scheduling of procedures and treatments, allowed to view test results or radiographs, and included in discussions of alternative therapies. Adolescents should assume increasing responsibility for management of their illness consistent with their developmental stage, level of maturity, and understanding of their illness. Areas of responsibility may include monitoring their condition, assessing indicators of exacerbation and change, self-medicating, asking for assistance, and maintaining insurance coverage (Newacheck, Wong, Galbraith, et al, 2003).

Helping the Child Cope

Through ongoing contact with the child, the nurse (1) observes the child’s reactions to chronic illness or disability, ability to function, and adaptive behaviors within the environment and with significant others; (2) explores the child’s own understanding of his or her illness; and (3) provides support while the child learns to cope with his or her feelings. Encourage children to verbalize their concerns rather than allowing others to verbalize for them, since open discussions may lessen anxiety.

Parents often express concern because their child cannot communicate the anxieties he or she is feeling. If the child will not or cannot speak, the child may need to play out his or her feelings. Toys can be provided to facilitate expression of the meaning of stressful or threatening emotions. The nurse may realize that the child responds best to telling stories or drawing pictures. (See Chapter 6.)

Coping Mechanisms

Children’s innate and learned coping mechanisms are crucial in their ability to cope with their condition. Children with special needs are likely to use distinct coping patterns (Box 22-2). Children with more accepting and positive attitudes about their chronic illness use a more adaptive coping style, characterized by competence, optimism, and compliance. They display fewer behavior problems at school and at home.

Because it is often easier to recognize children who cope poorly with illness or disability, it is helpful to describe those behaviors typical of well-adjusted children. Well-adapted children gradually learn to accept their physical limitations.

Normalization: One of the most important interventions to promote coping is alleviating the child’s feeling of being different and normalizing his or her life as much as possible. The principles in the Nursing Care Guidelines box are fundamental in implementing the normalization process. The nurse can help parents assess the child’s daily routine for indications of normalizing practices. For example, the child who remains in a bedroom all day needs a restructured daily routine to provide activities in different parts of the house, such as eating in the kitchen with the family, and the inclusion of social, recreational, and academic activities in the care plan.

Children who are concerned that their condition detracts from their physical attractiveness need attention focused on the normal aspects of appearance and capabilities. Health professionals can help parents strengthen the child’s self-image by emphasizing the normal, while at the same time allowing children to express anger, isolation, fear of rejection, sadness, and loneliness. Parents should encourage anything that might improve attractiveness and contribute to a positive self-image, such as makeup for a teenager with a scar, clothing that disguises a prosthesis, or a hairstyle or wig to cover a deformity or lost hair.

The parent’s behavior, particularly in relation to childrearing, is one of the most critical influences on the child’s adaptation to chronic illness. For example, children who are raised by parents who establish reasonable limits are likely to develop independence that is appropriate for their age and achievement equal to their limitations. They frequently exhibit confidence and pride in their ability to cope successfully with the challenges resulting from their condition. On the other hand, children whose parents are overprotective are likely to show fearfulness, marked dependency, and inactivity and to have few outside interests. Using anticipatory guidance and encouragement of normalizing practices, the nurse may assist parents in facilitating positive adaptation in their children. Normalization is important because it focuses on the child, not the condition.

Nurses can demonstrate the process of normalization to the child’s family by acknowledging the strengths and weaknesses of the family unit, by being supportive and open about the child’s condition and treatment, and by actively including the family in all aspects of care (Shepard and Mahon, 2009). If the child’s family adopts a normalized view of management of the chronic illness, the child may be more confident in the home as well as in social and community situations. Thus the family’s perception of the impact and the integration of the chronic illness may directly or indirectly improve the child’s adaptation (Sullivan-Bolyai, Knafl, Sadler, et al, 2004).

Nurses also can assist parents by identifying and building on family strengths, promoting family and child competence, and fostering the development of a nurturing environment that addresses the needs of siblings and parents, as well as of the child with special needs.

Hopefulness: Children, especially adolescents, are sensitive to the presence or absence of hope. From a psychologic perspective, Erikson’s theory of psychosocial growth and development proposes that hope is a basic ego quality that is initially experienced in infancy and is the positive outcome of successful resolution of the developmental stage of trust versus mistrust (Ritchie, 2001).

Hopefulness helps protect the adolescent from incapacitating despair and assists the adolescent in coping with unmet personal needs. A sense of hopefulness can result in increased participation in health-seeking behaviors and an improved sense of well-being. Nurses can be instrumental in fostering hopefulness through environmental and interpersonal means (see Nursing Care Guidelines box).

Health Education and Self-Care: Health education teaches children self-care behaviors and self-advocacy skills for dealing with the health care community. These are important skills for children and adolescents with chronic conditions to master because they are likely to use the health care system frequently throughout their lives (Vessey and Mebane, 2009). Active participation in care requires comprehensive family and patient education. Empowerment of individuals with disabilities is the philosophy that is currently advocated for provision of services. Gaining access to information helps the individual make informed decisions and acquire some control over the environment.

Children need information about how the body works, the characteristics of their condition, the treatment plan, the impact of illness or therapy, and, when age-appropriate, the intricacies of the health care system. Education is a primary component of self-care, and teaching methods must be modified to meet the child’s developmental age. In addition, children near puberty need to understand the maturation process and how their disability may change this event. For example, the child with Crohn disease should know that this illness is linked with delayed puberty and growth failure. The child with diabetes needs to understand that increased growth needs and hormonal changes will change insulin and food requirements at this time. The sexually active girl with systemic lupus erythematosus or sickle cell anemia needs to be aware of the risks of pregnancy. The information should not be provided during a single teaching session but rather timed appropriately to meet the child’s changing needs, and it should be described and repeated as frequently as the situation warrants.

For young children the information presented needs to be concise, simple, and honest, even if the news is not positive. Answer questions openly, since children need answers to the questions they are able to ask. If they have no confidence in the answer provided or are ignored, the only alternative left to them is to relate their experience to something fantasized or seen on television. If young children state that they do not want to learn more, then respect their wishes.

Developing the judgment and expertise for participating in self-care of chronic illness or disability is a process that occurs gradually. Self-care necessitates negotiation between child and parents. Nurses are instrumental in providing information on strategies for teaching children of various ages in self-care.

Realistic Future Goals: Because medical advances have led to prolonged survival for children with many chronic illnesses, these individuals are confronted with new decisions and problems such as employment,* marriage, medical and dental care access, and insurance coverage. Adolescents usually look forward to what their lives will be like in the future.

For some chronic illnesses or severe disabilities, one of the most difficult adjustments is establishing realistic goals for the child and for those involved in the child’s continual care. Occasionally the impact of these decisions does not surface until the child graduates from school or the parents move toward retirement, when a crisis can arise because of disruptions in the family roles and relationships that maintained stability.

For children with severe disabilities, preparing for the future should be a gradual process. All along the child and parents should consider realistic vocational options. For example, children with physical disabilities can be directed to artistic, intellectual, or musical pursuits. Children with developmental disabilities can be instructed in manual skills. Thus the child’s development progresses to self-support through gainful employment.

Unfortunately, vocational pursuits and independence are not realistic goals for all individuals. Persons with multiple or severe disabilities may require lifelong care and assistance. In these situations parents must look to the time when they will no longer be able to care for their child. Advance financial planning should be considered. Residential placement may be difficult unless the family mutually participates in the decision-making and planning processes. Parents should not view care outside the home as abandonment. Often it is the only way to preserve the family unit. The nurse should help the family investigate suitable placements, discuss their feelings regarding this decision, and explore measures to maintain meaningful communication with the member who has a disability. The nurse can take a larger advocacy role in educating the public regarding persons with special needs and helping normalize the experience for the child, the family, and the community.

Determining readiness for transfer to adult providers is a primary consideration. Arbitrary transfer to adult services based solely on an age criterion can compromise both psychosocial and physical care for some young adults. Many adolescents have received care in the same medical setting since birth and have established a trusting relationship with practitioners and staff. Moreover, age is not an indicator of adolescent readiness for transfer to an adult care provider. Important factors include (Reiss, Gibson, and Walker, 2005):

• Knowledge of the condition and its management

• Readiness to assume responsibility for treatment management

• Prior involvement in and compliance with the treatment regimen

• Demonstration of responsible and independent judgment

Nurses can take steps to help the adolescent prepare for the transition. These include presenting the idea of transfer; assessing the readiness of the adolescent and parent; coordinating a meeting with the adolescent, the family, and both pediatric and adult care providers; and formally acknowledging the transfer (Reiss, Gibson, and Walker, 2005).

Nurses are instrumental in assisting and supporting adolescents in assuming responsibility for managing their own care as much as possible. Adolescents should actively participate in the planning and decision-making processes for transition to adult care. In addition, nurses can foster continuity of care by providing information to adult health care providers about the adolescent’s needs relating to disease management and his or her compliance with the treatment regimen. The ultimate goal of transition care to adulthood for the adolescent with a chronic illness is to promote the achievement of responsible self-care and linkages to adult health care services and thus to provide the best prospects for educational options, social networks and relationships, community living, and employment.

The Family of the Child with Special Needs

A major goal in working with the family of a child with special needs is to support the family’s coping and help them function as best as they can throughout the child’s life. Long-term, comprehensive, family-centered approaches extend beyond supporting the child and family during the crucial periods of diagnosis and hospitalization. Comprehensive care involves building parent-professional partnerships that can support a family’s adaptation to the many changes that may be necessary in everyday life, defining expectations of and for the child, and providing a long-term perspective (Box 22-3).

Assessing Family Strengths and Adjustment

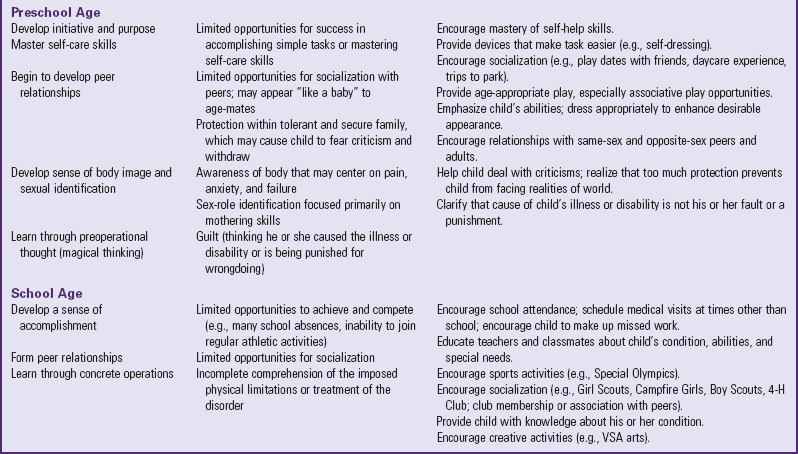

The purpose of a family assessment is to determine what assistance a family may need or want in managing their child’s care. Ideally the nurse should initiate an assessment as soon as the family learns the diagnosis. Integral to the family-centered care philosophy is the conception that the family should be an active participant in the process. Sample questions designed to elicit information for assessing the family’s adjustment are listed in Table 22-2. Family members should always be informed of the purpose of the assessment, including the rationale for asking personal questions. They should be afforded the opportunity to participate or not as they choose.

A number of instruments can be used to assess the family’s overall functioning and support system. In addition, specific tools have been developed for families of children with chronic illness or disability. For example, the Coping Health Inventory for Parents (CHIPTS) is an 80-item checklist that provides self-report information about how parents perceive their overall response to the management of family life with a child with a chronic illness. Coping behaviors (e.g., “believing that my child[ren] will get better” or “talking with the hospital staff [nurses, social workers] when we visited the medical center”) are listed, and parents are asked to rate how helpful the coping items are to them in managing the home situation. Chapter 25 describes tools that a family can use to assess the home environment and resources.

Regardless of the approach, assessment is a continual process. Because support systems and the perception of events may change at any time during an illness, nurses must assist families on an ongoing basis in evaluating the effectiveness of changes and interventions in support needs.

Accepting the Child’s Condition and Receiving Support at the Time of Diagnosis

The impact of a child’s developmental or medical condition is often experienced as a crisis at the time of diagnosis, which may be during birth, after a long period of psychologic and/or physical testing, or soon after a tragic injury. It may also begin before the diagnosis, when parents know that something is wrong with their child but there has been no medical confirmation.

Interventions facilitating the parents’ adjustment to the diagnosis of their child’s chronic illness or disability and their ability to care for their child include planning the setting for informing parents, assessing the family’s prior knowledge of and experience with chronic conditions (see Family-Centered Care box), selecting strategies that best meet the family’s needs and situation, evaluating the family’s understanding of the information presented, and providing ongoing follow-up. Effectively discussing the diagnosis provides a vital foundation for a strong collaborative relationship between parents and health care providers that will be needed in the future.

The physician or advanced practice nurse usually informs the family of the child’s diagnosis. Nurses are also responsible for providing follow-up information and coordinating services with other agencies. Whatever role nurses assume, they can follow the guidelines in the Nursing Care Guidelines box during disclosure of the diagnosis to offer the family support at this crucial time.

The informing conference should take place in a private, comfortable setting free of interruptions and distractions (Fig. 22-2). The environment should be one in which parents feel free to show their emotions. If parents can express their emotions openly, the nurse will be able to determine their need for additional counseling. Parents often sense a certain attitude of rejection, acceptance, hope, or despair that may affect their ability to assimilate the shock and begin adapting to the implications of the illness for their future.

Fig. 22-2 Informing sessions should take place in a private, comfortable setting free of distractions and interruptions.

The parents’ emotional needs at the time of diagnosis are acknowledged by exhibiting acceptance of such expressions as sadness, crying, disappointment, and anger. Emotional support is provided by having tissues available if a family member cries and by showing through body and facial language that indeed this is a painful and difficult time. Even though touching is a strong expression of empathy, it must be used cautiously. For example, it can prematurely terminate free expression of feelings, particularly when combined with statements such as, “Everything will be all right.” Nurses should also be cognizant of cultural sensitivity regarding touching. (See Chapter 2.)

Nurses should observe the responses of family members on hearing the diagnosis. Their facial expressions, their ability to maintain eye contact with the nurse, the times they look down, behaviors that indicate they are avoiding what the nurse is saying (such as turning their heads, looking away, or looking around), and any other activities that demonstrate they are dealing with a difficult matter are observed.

One of the most supportive interventions is to accept the family’s emotional reactions to the diagnosis in a nonjudgmental manner. Although all families react differently and with varying degrees of intensity, three reactions are common and are frequently poorly managed: guilt, denial, and anger.

Parents should receive the kind of information they want. Most parents prefer a simple, clear explanation of the diagnosis, including what is and is not known about the diagnosis, a prediction of possible prospects for the child, advice on what to do next, an opportunity to ask questions, a sympathetic and warm listener, and, most important, time. Determine the family’s level of understanding and expectations. Assess comprehension of explanations with questions such as, “Is this clear to you?” or “Do you see what I mean?” Take notes for the family to refer to in the future. Provide parents with supplemental written information or a written summary of the diagnosis in keeping with their emotional readiness.

A crucial task for parents is to decide when, what, and how to tell their child about the diagnosis. Like parents, children later remember vividly what happened when the diagnosis was disclosed. Ideally the parents should be responsible for sharing this information with their child. However, they need much guidance in communicating information about the nature of the illness and the changes imposed on physical appearance and energy using a calm and honest approach. This is because parents frequently use euphemisms and try to protect their child from the harsh realities of the diagnosis and illness. Nurses can promote open communication between parents and ill child by providing them with information about how young children think and respond to illness and to changes in their parents (crying or increased concern).

The informing conference should not only include the presentation of devastating news, but emphasize the child’s strengths and potential for development. Also assure the parents that the nurse will be available to answer questions and to provide further assistance as needed. Because of the need for long-term follow-up of chronic conditions, the initial informing conference is only one in a series of ongoing discussions. In all interactions the family’s input is requested and included in the care plan (see Nursing Care Guidelines box, p. 872).

Managing the Condition on an Ongoing Basis

Promoting the family’s adaptation to the day-to-day management of the child’s condition involves education about the child’s condition, general health care, and developmental needs and about realistic goal setting. Emotional support and assessment of the family also play a pivotal role in adaptation. Encourage families to articulate their goals and approaches to managing their children’s condition, which provides vital information on how to intervene more thoughtfully with families based on their treatment approach.

Because the majority of mothers and fathers of children with special needs have little or no experience with children who have chronic or disabling conditions, the nurse can remind them of their child’s many strengths and normal traits. Mothers and fathers need to experience happiness, success, and pride with regard to their child. The nurse can model appropriate interventions with the child. Most important, the nurse should ensure that the siblings and parents learn to perceive the child as a child first, with unique and individual needs and characteristics. The nurse needs to convey an accepting, humanistic attitude toward the child so that the parents can observe this acceptance. This attitude of having concern for, liking, and demonstrating acceptance of the child should begin in early infancy and continue throughout the child’s life.

Special Information Needs

Educating the family about the child’s condition is actually a continuation of the diagnostic talk (see Nursing Care Guidelines box, p. 859). Education involves providing technical information regarding management of the condition, such as how to administer insulin injections, and assessing both parental skills and understanding. In childhood cancer, educational components may include understanding and following a chemotherapy protocol, administering chemotherapy medications at home, anticipating and treating side effects, managing the child’s adjustment to the illness, and arranging support and care from home health agencies and community resources (Hockenberry and Kline, 2010). Discussions with parents must also address the impact of the condition on the child. For example, children who have lost a limb require more than an explanation about the prosthetic leg. They need to know what restrictions it imposes on their activity level and how to function with it.

Parents also need guidance on how the child’s condition may interfere with activities of daily living, such as dressing, eating, toileting, and sleeping* (see Family-Centered Care box). Common nutritional problems include overnutrition, which results from a caloric intake in excess of energy expenditure and may be related to boredom and lack of stimulation in other areas, and undernutrition, usually caused by inappropriate restriction of food, vomiting, loss of appetite, increased metabolic needs, or motor deficits that interfere with feeding. Although the child has the same basic needs as other children, the daily requirements may vary. Special nutritional considerations are discussed throughout the text.

Another major area in which modifications are necessary is car transportation. Children with conditions such as orthopedic, respiratory, or neuromuscular problems or low birth weight often cannot safely use conventional car restraints. For example, children with hip spica casts are unable to sit properly in child safety seats. (See Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip, Chapter 11.) Alterations can be made to some commercial models,† and for older children a special vest‡ is available that secures the child in a lying-down position to the back seat. Children in wheelchairs present special challenges because the wheelchair should be anchored with four points of attachment to the vehicle (two in front and two behind) and should always face forward. The family should contact the wheelchair manufacturer for specific instructions to ensure safe car transportation.