Health Promotion of the Infant and Family

Promoting Optimum Growth and Development,

http://evolve.elsevier.com/wong/ncic

Colic, Ch. 13

Communicable Diseases, Ch. 16

Dental Health, Ch. 14

Health Problems During Infancy, Ch. 13

Infant Mortality, Ch. 1

Ingestion of Injurious Agents, Ch. 16

Injury Prevention, Ch. 14

Intramuscular Administration (of Medication), Ch. 27

Limit Setting and Discipline, Ch. 3

Mammal Bites, Ch. 18

Preschool and Kindergarten Experience, Ch. 15

Promotion of Parent-Infant Bonding (Attachment), Ch. 8

Provision of Optimum Nutrition, Ch. 8

Separation Anxiety, Ch. 26

Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, Ch. 13

Sunburn, Ch. 18

Temperament, Ch. 14

Promoting Optimum Growth and Development

![]() At no other time in life are physical changes and developmental achievements so dramatic as during infancy. All body systems undergo progressive maturation. Concurrent development of skills allows infants to increasingly respond to the environment. Acquisition of these fine and gross motor skills occurs in an orderly head-to-toe and center-to-periphery (cephalocaudal-proximodistal) sequence.

At no other time in life are physical changes and developmental achievements so dramatic as during infancy. All body systems undergo progressive maturation. Concurrent development of skills allows infants to increasingly respond to the environment. Acquisition of these fine and gross motor skills occurs in an orderly head-to-toe and center-to-periphery (cephalocaudal-proximodistal) sequence.

![]() Case Study—Infant Growth and Development

Case Study—Infant Growth and Development

Proportional Changes

Growth is rapid during the first year, especially during the initial 6 months. Infants gain 680 g (1.5 lb) per month until age 5 months, when the birth weight has at least doubled. An average weight for a 6-month-old child is 7.26 kg (16 lb). Weight gain decreases by half that amount during the second 6 months. By 1 year of age the infant’s birth weight has tripled, to an average of 9.75 kg (21.5 lb). Infants who are breast-fed beyond 4 to 6 months of age typically gain less weight than those who are bottle-fed, yet head circumference is more than adequate (Lawrence and Lawrence, 2005). (See Family-Centered Care box, p. 263.)

Height increases by 2.5 cm (1 inch) per month during the first 6 months and by half that amount per month during the second 6 months. Increases in length occur in sudden spurts rather than in a slow, gradual pattern. Average height is 65 cm (25.5 inches) at 6 months and 74 cm (29 inches) at 12 months. By 1 year birth length has increased by almost 50%. This increase occurs mainly in the trunk rather than the legs and contributes to the characteristic physique of the older infant (see Fig. 12-8, A).

Head growth is also rapid and an important determinant of brain growth. Head circumference increases approximately 2 cm (0.75 inch) per month from birth to 3 months, 1 cm (0.4 inch) per month from 4 to 6 months, and 0.5 cm (0.2 inch) per month during the second 6 months. The average head size is 43 cm (17 inches) at 6 months and 46 cm (18 inches) at 12 months. By 1 year of age head size has increased by almost 33%. Closure of the cranial sutures occurs, with the posterior fontanel fusing by 6 to 8 weeks of age and the anterior fontanel closing by 12 to 18 months of age (the average age being 14 months).

It is important to note that genetic, metabolic, environmental, and nutritional factors strongly influence infant growth; thus the previous statements are general guidelines only. Use the appropriate growth charts reflecting weight for length and head circumference in each case to determine appropriate growth parameters.

Expanding head size reflects the growth and differentiation of the nervous system. By the end of the first year the brain has increased in weight approximately two and one half times. Maturation of the brain is exhibited in the dramatic developmental achievements of infancy (see Table 12-3). The primitive reflexes (see Table 8-4) are replaced by voluntary, purposeful movement, and new reflexes that influence motor development appear (Box 12-1 and Fig. 12-1).

The chest assumes a more adult contour, with the lateral diameter becoming larger than the anteroposterior diameter. The chest circumference approximately equals head circumference by the end of the first year. The heart grows less rapidly than does the rest of the body. Its weight is usually doubled by 1 year of age, whereas body weight triples over the same period. The size of the heart is still large in relation to the chest cavity; its width is approximately 55% of the chest width.

Sensory Changes

During infancy, visual acuity gradually improves and binocular fixation is established. Box 12-2 lists the major developmental characteristics of vision during infancy. Binocularity, or the fixation of two ocular images into one cerebral picture (fusion), begins to develop by 6 weeks of age and should be well established by age 4 months (Fig. 12-2). Lack of binocular vision results in strabismus and must be detected early to prevent permanent blindness.

Fig. 12-2 Three-month-old infant focuses on visual object and reaches toward it. (Courtesy Paul Vincent Kuntz, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston.)

Depth perception (stereopsis) begins to develop by age 7 to 9 months but may exist earlier as an innate safety mechanism. At approximately 7 months the parachute reflex appears and may be a protective response during a fall (see Fig. 12-1 and Box 12-1).

Infants have a visual preference for looking at the human face; this preference also has a developmental sequence. At age 6 weeks infants show more interest in a picture of a face with eyes than in one without eyes. By 10 weeks of age a picture with both eyes and eyebrows elicits more response, and by 20 weeks of age the mouth is also necessary. By age 6 months infants respond to facial expressions and can distinguish between familiar and strange faces. This is about the time that separation anxiety begins to occur (see p. 480).

With progressive myelination of the auditory pathway, the specific responses of locating sound replace the generalized response of the neonate. Box 12-3 lists the major developmental characteristics of hearing. (For further discussion of hearing and the senses of smell, taste, and touch, see Chapter 8.)

Maturation of Systems

Other organ systems also change and grow during infancy. The respiratory rate slows somewhat (see inside back cover) and is relatively stable. Respiratory movements continue to be abdominal. Several factors predispose the infant to severe and acute respiratory problems. Given the proximity of the trachea to the bronchi and its branching structures, an infectious agent is rapidly transmitted from one anatomic location to another. The short, straight eustachian tube closely communicates with the ear, allowing infection to ascend from the pharynx to the middle ear. In addition, the immune system’s inability to produce immunoglobulin (Ig) A in the mucosal lining provides less protection against infection in infancy than in later childhood. The entire respiratory tract’s ability to produce mucus is diminished, decreasing the humidification of the large volume of inspired air.

Although the lumen of the trachea and bronchi enlarges during infancy, it remains small in comparison with the total size of the lung, maintaining high resistance to the volume of air inspired. The small airways are easily blocked by edema, mucus, or a foreign body. The pliant (flexible) rib cage has less elastic recoil, and during respiratory distress the work of breathing is increased. In addition, the volume of dead space (that amount of air needed to fill the respiratory passages with each breath) is large, requiring the infant to breathe approximately twice as fast as the adult to provide the body with the needed amount of oxygen.

As the infant grows, the heart rate slows (see inside back cover), and the rhythm is often sinus arrhythmia (rate increases with inspiration and decreases with expiration). Blood pressure also changes during infancy (see inside back cover). Systolic pressure rises during the first 2 months as a result of the left ventricle’s increasing ability to pump blood into the systemic circulation. Diastolic pressure decreases during the first 3 months then gradually rises to values close to those at birth. Fluctuations in blood pressure occur during varying states of activity and emotion.

Significant hematopoietic changes occur during the first year (see Appendix D). Fetal hemoglobin (HgbF) is present up to the first 5 months, with adult hemoglobin steadily increasing through the first half of infancy. HgbF results in a shortened survival of red blood cells (RBCs) and thus a decreased number of RBCs. A common result at 2 to 3 months of age is physiologic anemia. High levels of HgbF depress the production of erythropoietin, a hormone released by the kidney that stimulates RBC production.

Maternally derived iron stores are present for the first 5 to 6 months and gradually diminish, which also accounts for lowered hemoglobin levels toward the end of the first 6 months. The occurrence of physiologic anemia is not affected by an adequate iron supply. However, when erythropoiesis is stimulated, iron stores are necessary for the formation of adequate amounts of hemoglobin.

The digestive processes are relatively immature at birth. Although full-term newborn infants have some limitations in digestive function, studies indicate that human milk has properties that partially compensate for decreased digestive enzymatic activity, thus enabling the infant to receive optimum nutrition during the first several months of life (Lawrence and Lawrence, 2005). The enzyme ptyalin (also called amylase) is present in small amounts but usually has little effect on the foodstuffs because of the small amount of time the food stays in the mouth. Gastric digestion in the stomach relies primarily on the action of hydrochloric acid and rennin, an enzyme that acts specifically on the casein in milk to cause the formation of curds (coagulated semisolid particles of milk). The curds cause the milk to be retained in the stomach long enough for digestion to occur.

Digestion also takes place in the duodenum, where pancreatic enzymes and bile begin to break down protein and fat. Secretion of the pancreatic enzyme amylase, which is needed for digestion of complex carbohydrates, is limited until about the fourth to sixth months of life. Lipase is also limited, and infants do not achieve adult levels of fat absorption until 4 to 5 months of age. Trypsin is secreted in sufficient quantities to catabolize protein into polypeptides and some amino acids.

The immaturity of the digestive processes is evident in the appearance of stools. During infancy, solid foods (e.g., peas, carrots, corn, and raisins) are passed incompletely broken down in the feces. An excessive quantity of fiber easily disposes the child to loose, bulky stools. During infancy the stomach enlarges to accommodate a greater volume of food. By the end of the first year the infant is able to tolerate three meals a day and an evening bottle and may have one or two bowel movements daily. However, with any type of gastric irritation the infant is vulnerable to diarrhea, vomiting, and dehydration. (See Chapters 28 and 29.)

The liver is the most immature of all the gastrointestinal organs throughout infancy. The ability to conjugate bilirubin and secrete bile is achieved after the first couple of weeks of life. However, the capacities for gluconeogenesis, formation of plasma protein and ketones, storage of vitamins, and deaminization of amino acids remain relatively immature for the first year of life.

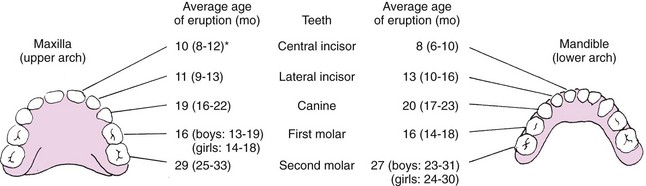

Maturation of the sucking, swallowing, and breathing reflexes and the later eruption of teeth parallel the changes in the gastrointestinal tract and prepare the infant for the introduction of solid foods.

Sucking activity can occur in utero as early as 15 to 18 weeks of gestation. Weak, disorganized mouthing movements may be noted at 27 to 28 weeks of gestation. Complete maturation of sucking, swallowing, and breathing patterns are usually synchronized by 36 to 38 weeks, although some sucking and swallowing synchrony is seen by 32 to 34 weeks (Blackburn, 2007). Sucking is further divided into nutritive and nonnutritive; the latter is observed in infants of all ages and is reported to be primarily for the purpose of satisfying the basic sucking urge. On the other hand, nutritive sucking has as its primary purpose the intake of food. Suckling is a term often used for breast-feeding (Lawrence and Lawrence, 2005), yet use of the term varies among different sources.

Swallowing (deglutition) is the ability to collect the food (bolus) and propel it into the esophagus. During the infantile (visceral) swallow reflex food lies in a shallow groove on the top (dorsum) of the tongue. As the tongue is pressed upward toward the palate, the milk flows by gravity down the sloping tongue and along the sides of the mouth in lateral furrows between the tongue, cheek, and gum pads. As the bolus moves downward, the posterior wall of the pharynx comes forward to displace the soft palate. This swallowing process is efficient for fluids but not for solids.

As the infant grows, the tongue becomes smaller in proportion to the oral cavity and attains greater motility, the orofacial muscles develop, and teeth erupt. Consequently, the mature (somatic) swallow reflex is significantly different. The tongue remains behind the central incisors, and the mandible no longer thrusts forward. The dorsum of the tongue is less concave and remains higher and parallel, not inclined, against the palate. The lateral furrows are absent because of tooth eruption. Tongue pressure and movement against the hard palate push the bolus back into the pharynx.

Infants also exhibit a special reflex called the Santmyer swallow. When a puff of air is directed at the face, the infant will exhibit a reflexive swallow. Because the infant cannot respond to a verbal command to swallow, this reflex is often useful in the administration of small amounts of fluids or medications.

The immunologic system undergoes numerous changes during the first year. The full-term newborn receives significant amounts of maternal IgG, which for approximately 3 months confers immunity against many antigens to which the mother was exposed. After birth IgG levels gradually fall as maternal IgG is catabolized and the newborn produces limited IgG. The lowest IgG levels occur at approximately 2 to 4 months, and levels remain low until approximately 6 months (Blackburn, 2007). Infants reach approximately 40% of adult levels by 1 year of age; therefore during the first 6 to 12 months of life the infant is at higher risk for infections. Significant amounts of IgM are produced at birth yet specificity is decreased, thus limiting recognition of certain pathogens. Adult levels of IgM are reached by 9 to 12 months of age. The production of IgA, IgD, and IgE is much more gradual, and maximum levels are not attained until early childhood.

Secretory IgA (sIgA) is not present at birth but is found in saliva and tears by 2 to 5 weeks. sIgA is present in large amounts in human colostrum. Researchers believe this has a protective role in the gastrointestinal tract against many bacteria such as Escherichia coli and viruses such as poliovirus. The development of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) occurs during infancy. In part, this system prevents colonization and passage of bacteria across the infant’s mucosal barrier (Lawrence and Lawrence, 2005). The function and quantity of T lymphocytes, lymphokines, interleukins, tumor necrosis factor alpha, interferon-γ, and complement are reduced in early infancy, thus preventing optimum response to certain bacteria and viruses. Prebiotic oligosaccharides found in breast milk produce probiotic bacteria such bifidobacteria and lactobacilli, which in turn stimulate synthesis and secretion of sIgA. sIgA coats the gastrointestinal mucosa to further protect the infant from certain pathogens (Blackburn, 2007). Probiotics may have a significant role in helping the gastrointestinal tract establish a “good” bacterial colonization in the gut to prevent many illnesses, including possibly necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants (Caplan, 2009; Goldin and Gorbach, 2008).

There is evidence that vernix caseosa, a white oily substance that coats the term infant’s body and is often found in abundance in the creases of the axillae and groin, has innate immunologic properties that serve to protect the newborn from infection (Narendran and Hoath, 2006).

During infancy thermoregulation becomes more efficient; the skin’s ability to contract and of muscles to shiver in response to cold increases. The peripheral capillaries respond to changes in ambient temperature to regulate heat loss. The capillaries constrict in response to cold, conserving core body temperature and decreasing potential evaporative heat loss from the skin surface. The capillaries dilate in response to heat, decreasing internal body temperature through evaporation, conduction, and convection. Shivering (thermogenesis) causes the muscles and muscle fibers to contract, generating metabolic heat, which is distributed throughout the body. Increased adipose tissue during the first 6 months insulates the body against heat loss.

A shift in total body fluid occurs. At birth 78% of the infant’s body weight is water, while a significant amount of that is extracellular fluid (ECF). As the percentage of body water decreases, so does the amount of ECF—from 44% at term to 20% in adulthood. The high proportion of ECF, which is composed of blood plasma, interstitial fluid, and lymph, predisposes the infant to more rapid loss of total body fluid and, consequently, dehydration. The loss of 5% to 10% of the term newborn’s initial birth weight in the first 5 days of life is attributed to ECF compartment contraction, enhanced renal tubular function, and rapidly increasing glomerular filtration rate (Blackburn, 2007).

The immaturity of the renal structures also predisposes the infant to dehydration. Complete maturity of the kidney occurs during the latter half of the second year, when the cuboidal epithelium of the glomeruli becomes flattened. Before this time the filtration capacity of the glomeruli is reduced. Infants void urine frequently, and it has a low specific gravity (1.008 to 1.012). At term most infants produce and excrete approximately 15 to 60 ml/kg/24 hr, and an output of less than 0.5 ml/kg/hr after 48 hours of age is considered to be oliguria (Blackburn, 2007).

The endocrine system is adequately developed at birth, but its functions are immature. The interrelatedness of all the endocrine organs has a major effect on the function of any one gland. The lack of homeostatic control because of various functional deficiencies renders the infant especially vulnerable to imbalances in fluid and electrolytes, glucose concentration, and amino acid metabolism. For example, corticotropin (adrenocorticotropic hormone [ACTH]) is produced in limited quantities during infancy. ACTH acts on the adrenal cortices to produce their hormones, particularly the glucocorticoids and aldosterone. Because the feedback mechanism between ACTH and the adrenal cortex is immature during infancy, there is much less tolerance for stressful conditions, which affect fluid and electrolytes and the metabolism of fats, proteins, and carbohydrates. In addition, although the islets of Langerhans produce insulin and glucagon during fetal life and early infancy, blood glucose levels tend to remain labile, particularly under conditions of stress.

Fine Motor Development

Fine motor behavior includes the use of the hands and fingers in the prehension (grasp) of an object. Grasping occurs during the first 2 to 3 months as a reflex and gradually becomes voluntary. At 1 month of age the hands are predominantly closed, and by 3 months they are mostly open. By this time infants demonstrate a desire to grasp an object, but they “grasp” it more with the eyes than with the hands. If a rattle is placed in the hand, the infant will actively hold onto it. By 4 months of age the infant regards both a small pellet and the hands and then looks from the object to the hands and back again. By 5 months the infant is able to voluntarily grasp an object.

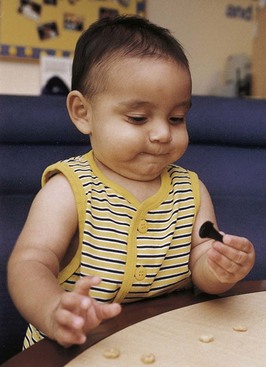

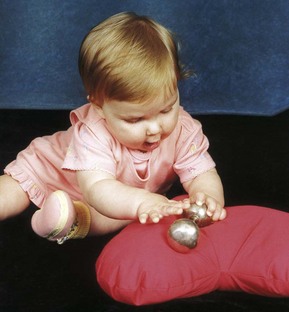

Gradually the palmar grasp (using the whole hand) is replaced with a pincer grasp (using the thumb and index finger). By 8 to 9 months of age the infant uses a crude pincer grasp (Fig. 12-3), and by 10 months of age the pincer grasp is sufficiently established to enable infants to pick up a raisin and other finger foods. By 11 months the infant has progressed to a neat pincer grasp (Fig. 12-4).

Fig. 12-3 Crude pincer grasp at 8 to 10 months of age. (Courtesy Paul Vincent Kuntz, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston.)

Fig. 12-4 Neat pincer grasp at 11 months of age. (Courtesy Paul Vincent Kuntz, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston.)

By 6 months of age infants have increased manipulative skill. They hold their bottle, grasp their feet and pull them to their mouth, and feed themselves a cracker. By 7 months they transfer objects from one hand to the other, use one hand for grasping, and hold a cube in each hand simultaneously. They enjoy banging objects and will explore the movable parts of a toy. By 10 months of age infants can deliberately let go of an object and will offer it to someone. By 11 months they put objects into a container and like to remove them. By age 1 year infants try to build a tower of two blocks but fail.

Gross Motor Development

Gross motor behavior includes developmental maturation in posture, head balance, sitting, creeping, standing, and walking. The full-term neonate is born with some ability to hold the head erect and reflexively assumes the postural tonic neck position when supine. Several of the primitive reflexes have significance in terms of development of later gross motor skills. The righting reflexes elicit certain postural responses, particularly of flexion or extension. They are responsible for certain motor activities, such as rolling over, assuming the crawl position, and maintaining normal head-trunk-limb alignment during all activities. The neck-righting reflex, which turns the body to the same side as the head, enables the child to roll over from supine to prone. Other reflexes, such as the otolith-righting and labyrinth-righting reflexes, enable the infant to raise the head (see Box 12-1).

The asymmetric tonic neck reflex, which persists from birth to 3 months, prevents the infant from rolling over. The symmetric tonic neck reflex, which is evoked by flexing or extending the neck, helps the infant assume the crawl position. When the head and neck are extended, the extensor tone of the upper extremities and the flexor tone of the lower extremities increase. The child extends the arms and bends the knees. Because of the strong flexor tone of the lower extremities, the infant may initially crawl backward before crawling forward. This reflex disappears when neurologic maturity allows actual crawling to occur because independent limb movement is required.

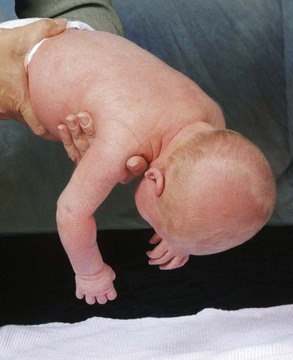

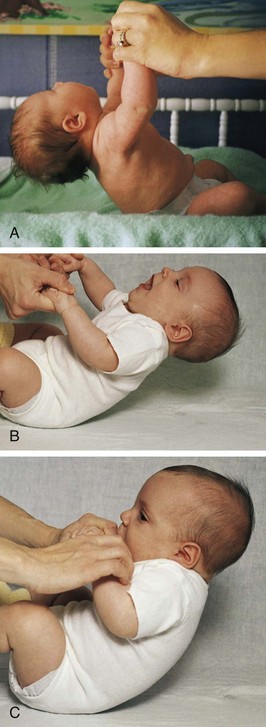

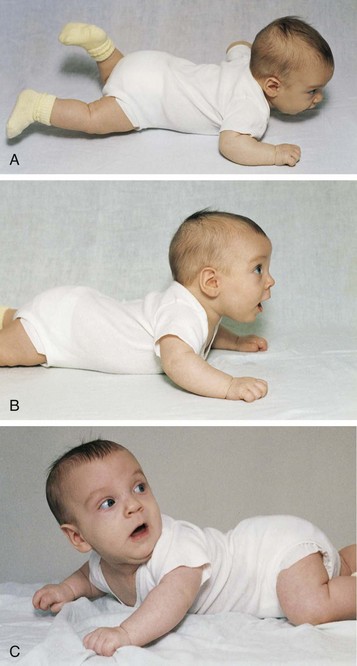

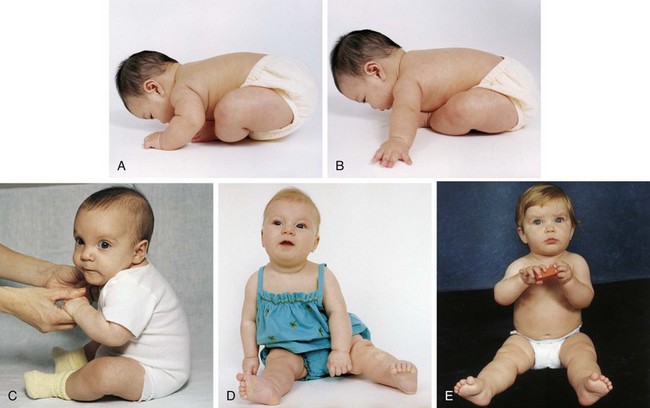

Head Control: The full-term newborn can momentarily hold the head in midline and parallel when the body is suspended ventrally and can lift and turn the head from side to side when prone (see Fig. 8-8). This is not the case when the infant is lying prone on a pillow or soft surface; infants do not have the head control to lift their head out of the depression of the object and therefore risk possible suffocation. (See Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, Chapter 13.) Marked head lag is evident when the infant is pulled from a lying to a sitting position. By 3 months of age infants can hold their head well beyond the plane of the body. By 4 months of age infants can lift the head and front portion of the chest approximately 90 degrees above the table, bearing their weight on the forearms. Only slight head lag is evident when the infant is pulled from a lying to a sitting position, and by 4 to 6 months head control is well established (Figs. 12-5 and 12-6).

Fig. 12-5 Head control while pulled to sitting position. A, Complete head lag at 1 month. B, Partial head lag at 2 months. C, Almost no head lag at 4 months.

Fig. 12-6 Head control while prone. A, Infant momentarily lifts head at 1 month. B, Infant lifts head and chest 90 degrees and bears weight on forearms at 4 months. C, Infant lifts head, chest, and upper abdomen and can bear weight on hands at 6 months. Note how this position facilitates turning from abdomen to back.

Rolling Over: Newborns may roll over accidentally because of their rounded back. The ability to willfully turn from the abdomen to the back occurs at 5 months, and the ability to turn from the back to the abdomen occurs at 6 months. It is noteworthy that the parachute reflex (see Fig. 12-1), which elicits a protective response to falling, appears at 7 months.

Sitting: The ability to sit follows progressive head control and straightening of the back (Fig. 12-7). For the first 2 to 3 months the back is uniformly rounded. The convex cervical curve forms at approximately 3 to 4 months of age, when head control is established. The convex lumbar curve appears when the child begins to sit, at about age 4 months. As the spinal column straightens, the infant can be propped in a sitting position. By age 7 months infants can sit alone, leaning forward on their hands for support. By age 8 months they can sit well while unsupported and begin to explore their surroundings in this position rather than in a lying position. By 10 months they can maneuver from a prone to a sitting position.

Fig. 12-7 Development of sitting. A, Back is completely rounded; infant has no ability to sit upright at 1 month. B, At 2 months, infant exhibits more control; back is still rounded, but infant can try to pull up with some head control. C, Back is rounded only in lumbar area; infant is able to sit erect with good head control at 4 months. D, Infant can sit alone, leaning on hands for support, at 7 months. E, Infant sits without support at 8 months. Note the transferring of objects that occurs at 7 months. (Courtesy Paul Vincent Kuntz, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston.)

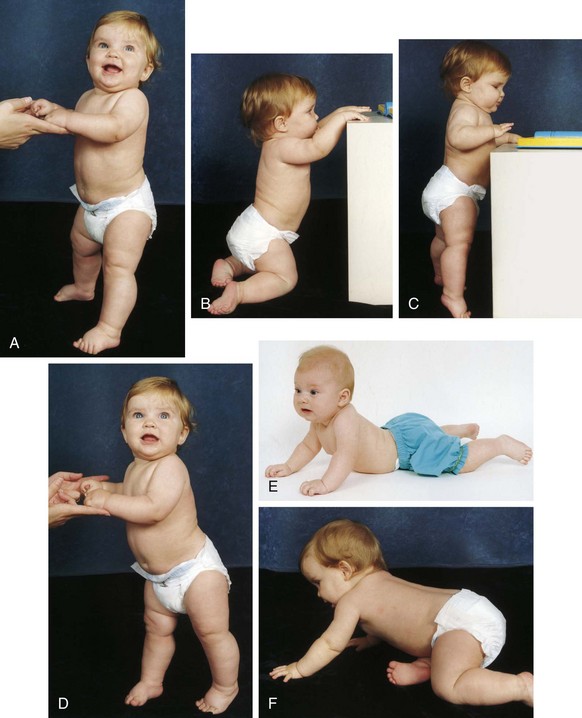

An infant who does not pull to a standing position by 11 to 12 months of age should be further evaluated for possible developmental dysplasia of the hip. (See Chapter 11.) Although infants vary considerably in regard to the achievement of these milestones, they provide guidelines for early intervention.

Locomotion: Locomotion involves acquiring the ability to bear weight, propel forward on all four extremities, stand upright with support, and, finally, walk alone (Fig. 12-8). Following a cephalocaudal pattern, infants 4 to 6 months old have increasing coordination in their arms. Initial locomotion results in infants propelling themselves backward by pushing with the arms. By 6 to 7 months of age they are able to bear all their weight on their legs with assistance. Crawling (propelling forward with belly on floor) progresses to creeping on hands and knees (with belly off floor) by 9 months. At this time they stand while holding onto furniture and can pull themselves to the standing position, but they are unable to maneuver back down except by falling. By 11 months they walk while holding onto furniture or with both hands held, and by age 1 year they may be able to walk with one hand held. A number of infants attempt their first independent steps by their first birthday.

Fig. 12-8 Development of locomotion. A, Infant bears full weight on feet by 7 months. B, Infant can maneuver from sitting to kneeling position by 8 months. C, Infant can stand holding onto furniture at 8 to 9 months. D, While standing, infant takes deliberate step at 9 to 10 months. E, Infant crawls with abdomen on floor and pulls self forward and then, F, creeps on hands and knees at 9 months. (Courtesy Paul Vincent Kuntz, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston.)

Calculate an infant’s motor age (development) by calculating a motor quotient (MQ) using the following formula:

For example, if a 12-month-old infant begins to creep, the motor quotient is 9 (MA for this skill) divided by 12 (chronologic age) times 100, which equals 75. Values above 85 are considered within normal limits, values below 70 are abnormal, and values between 70 and 85 are borderline (Johnson and Blasco, 1997).

Psychosocial Development

![]() Developing a Sense of Trust (Erikson)

Developing a Sense of Trust (Erikson)

![]() Summary of Personality, Cognitive, and Moral Development Theories

Summary of Personality, Cognitive, and Moral Development Theories

Erik Erikson’s (1963) phase I (birth to 1 year) is concerned with acquiring a sense of trust while overcoming a sense of mistrust. Erikson was a neo-Freudian who incorporated much of Freud’s theory. (See Chapter 3.) The trust that develops is a trust of self, of others, and of the world. Infants “trust” that their feeding, comfort, stimulation, and caring needs will be met. The crucial element for the achievement of this task is the quality of both the relationship between the parent (or caregiver) and child and the care the infant receives. The provision of food, warmth, and shelter by itself is inadequate for the development of a strong sense of self. The infant and parent must jointly learn to satisfactorily meet their needs for mutual regulation of frustration to occur. When this synchrony fails to develop, mistrust is the eventual outcome. Frustration is heightened in situations in which the parent is emotionally immature and does not understand the infant’s behavioral cues because of his or her own self-centered phase of development.

Failure to learn delayed gratification leads to mistrust. Mistrust can result from either too much or too little frustration. If parents always meet their children’s needs before the children signal their readiness, infants will never learn to test their ability to control the environment. If the delay is prolonged, infants will experience constant frustration and eventually mistrust others in their efforts to satisfy them. Therefore consistency of care is essential.

The trust acquired in infancy provides the foundation for all succeeding phases. Trust allows infants a feeling of physical comfort and security, which assists them in experiencing unfamiliar, unknown situations with a minimum of fear. Erikson has divided the first year of life into two oral-social stages. During the first 3 to 4 months, food intake is the most important social activity in which the infant engages. The newborn can tolerate little frustration or delay of gratification. Primary narcissism (total concern for oneself) is at its height. However, as bodily processes such as vision, motor movements, and vocalization become better controlled, infants use more advanced behaviors to interact with others. For example, rather than cry, infants may put their arms up to signify a desire to be held.

The next social modality involves a mode of reaching out to others through grasping. Grasping is initially reflexive, but even as a reflex it has a powerful social meaning for the parents. The reciprocal response to the infant’s grasping is the parents’ holding on and touching. There is pleasurable tactile stimulation for both the child and the parents.

Tactile stimulation is extremely important in the total process of acquiring trust. The degree of mothering skill, the quantity of food, or the length of sucking does not determine the quality of the experience. Rather, it is the total quality of the interpersonal relationship that influences the infant’s formulation of trust.

During the second stage, the more active and aggressive modality of biting occurs. Infants learn that they can hold onto what is their own and can more fully control their environment. During this stage infants may be confronted with one of their first conflicts. If they are breast-feeding, they quickly learn that biting causes the mother to become upset and withdraw the breast. Yet biting also brings internal relief from teething discomfort and a sense of power or control.

This conflict has a variety of solutions. The mother may wean the infant from the breast and begin bottle-feeding, or the infant may learn to bite substitute “nipples,” such as a pacifier, and retain pleasurable breast-feeding. The successful resolution of this conflict strengthens the mother-child relationship because it occurs at a time when infants are recognizing the mother as the most significant person in their life.

Cognitive Development

The theory most commonly used to explain cognition, or the ability to know, is that of Piaget (1952). The period from birth to 24 months is termed the sensorimotor phase and is composed of six stages. However, because this discussion centers on ages birth to 12 months, only the first four stages are discussed (Table 12-1; see Table 14-1 for the stages from 13 to 24 months).

During the sensorimotor phase, infants progress from reflexive behaviors to simple repetitive acts to imitative activity. Three crucial events take place during this phase. The first event involves separation, in which infants learn to separate themselves from other objects in the environment. They realize that others besides themselves control the environment and that certain adjustments must take place for mutual satisfaction to occur. This coincides with Erikson’s concept of the formation of trust and mutual regulation of frustration.

The second major accomplishment is achieving the concept of object permanence, or the realization that objects that leave the visual field still exist. A typical example of the development of object permanence is when infants are able to pursue objects they observe being hidden under a pillow or behind a chair (Fig. 12-9). This skill develops at approximately 9 to 10 months of age, which corresponds to the time of increased locomotion skills.

Fig. 12-9 Nine-month-old is able to find hidden object under pillow. (Courtesy Paul Vincent Kuntz, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston.)

The last major intellectual achievement of this period is the ability to use symbols, or mental representation. The use of symbols allows the infant to think of an object or situation without actually experiencing it. The recognition of symbols is the beginning of the understanding of time and space.

The first stage, from birth to 1 month, is identified by the infant’s use of reflexes. At birth the infant expresses individuality and temperament through the physiologic reflexes of sucking, rooting, grasping, and crying. The repetitious nature of the reflexes is the beginning of associations between an act and a sequential response. When infants cry because they are hungry, a nipple is put in the mouth, and they suck, feel satisfaction, and sleep. They are assimilating this experience while perceiving auditory, tactile, and visual cues. This experience of perceiving certain patterns, or ordering, provides a foundation for the subsequent stages.

The second stage, primary circular reactions, marks the beginning of the replacement of reflexive behavior with voluntary acts. During the period from 1 to 4 months, activities such as sucking or grasping become deliberate acts that elicit certain responses. The beginning of accommodation is evident. Infants incorporate and adapt their reactions to the environment and recognize the stimulus that produced a response. Previously they would cry until the nipple was brought to the mouth. Now they associate the nipple with the sound of the parent’s voice. They accommodate this new piece of information and adapt by ceasing to cry when they hear the voice—before receiving the nipple. What is taking place is a realization of causality and recognition of an orderly sequence of events. The infant takes in the environment with all the senses and with whatever motor ability is present.

The secondary circular reactions stage is a continuation of primary circular reactions and lasts until 8 months of age. In this stage the primary circular reactions are repeated and prolonged for the response that results. Grasping and holding now become shaking, banging, and pulling. Infants shake objects to hear a noise, not solely for the pleasure of shaking. Quality and quantity of an act become evident. “More” or “less” shaking produces different responses. Causality, time, deliberate intention, and separateness from the environment begin to develop.

Three new processes of human behavior occur. Imitation requires the differentiation of selected acts from several events. By the second half of the first year infants can imitate sounds and simple gestures. Play becomes evident as they take pleasure in performing an act after they have mastered it. Much of infants’ waking hours are absorbed in sensorimotor play. Affect (outward manifestation of emotion and feeling) is evident as infants begin to develop a sense of permanency. During the first 6 months infants believe that an object exists only for as long as they can visually perceive it; in other words, out of sight, out of mind. A reaction to external objects is evident when the object continues to be remembered even though it is beyond the range of perception. Object permanence is a critical component of parent-child attachment and is seen in the development of separation anxiety at 6 to 8 months of age (p. 480).

During the fourth sensorimotor stage, coordination of secondary schemas and their application to new situations, infants use previous behavioral achievements primarily as the foundation for adding new intellectual skills to their expanding repertoire. This stage is largely transitional. Increasing motor skills allow for greater exploration of the environment. They begin to discover that hiding an object does not mean that it is gone but that removing an obstacle will reveal the object. This marks the beginning of intellectual reasoning. Furthermore, they can experience an event by observing it, and they begin to associate symbols with events (e.g., “bye-bye” with “Daddy goes to work”), but the classification is purely their own. In this stage they learn from the object itself. This is in contrast to the second stage, in which infants learn from the type of interaction between objects or individuals. Intentionality is further developed in that infants now actively attempt to remove a barrier to the desired (or undesired) action (see Fig. 12-9). If something is in their way, they attempt to climb over it or push it away, whereas previously they would have given up any attempt to achieve the desired goal.

Development of Body Image

The development of body image parallels sensorimotor development. Infants’ kinesthetic and tactile experiences are the first perceptions of their body, and the mouth is the principal area of pleasurable sensations. Other parts of the body are primarily objects of pleasure—the hands and fingers to suck and the feet to play with. As physical needs are met, they feel comfort and satisfaction with their body. Messages conveyed by the caregivers reinforce these feelings. For example, when infants smile, they receive emotional satisfaction from others who smile back.

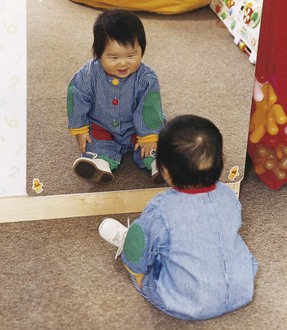

Achieving the concept of object permanence is basic to the development of self-image. By the end of the first year infants recognize that they are distinct from their parents. At the same time they have increasing interest in their image, especially in the mirror (Fig. 12-10). As motor skills develop, they learn that parts of the body are useful; for example, the hands bring objects to the mouth, and the legs help them move to different locations. All these achievements transmit messages to them about themselves. Therefore it is important to transmit positive messages to infants about their bodies.

Development of Gender Identity

Gender identity is reported to begin in utero because of hormonal influences that are not entirely understood. At birth the child is named and significant others, especially the parents, act certain ways toward the infant because of its gender. Touch is crucial to infant development and plays a primary role in gender development. Infants have a great oral sensitivity, which is manifested through sucking and mouthing. They enjoy skin-to-skin contact and explore their own body for pleasure. Infants are capable of genital self-stimulation to orgasm; erections in male infants are common. Parents’ responses to these early manifestations of sexuality influence children’s evolving attitudes. Therefore a healthy, accepting response by parents is important.

Social Development

Infants’ social development is initially influenced by their reflexive behavior, such as the grasp, and eventually depends primarily on the interaction between them and the principal caregivers. Attachment to the parent is increasingly evident during the second half of the first year. In addition, infants make tremendous strides in communication and personal-social behavior. Play is a major socializing agent and provides the stimulation needed to learn from interactions with the environment.

Attachment

Human physical contact is extremely important. Parenting is not an instinctual ability but a learned, acquired process. The attachment of parent and child, which begins before birth and assumes even more importance at birth (see Chapter 8), continues during the first year. In the following discussion of attachment, the word mother is used in the broad context of the consistent caregiver with whom the child relates more than anyone else. However, in a society with a changing social climate and dissolving sex-role stereotypes, this person may well be the father, grandmother, or other family member.

Studies on father-child attachment demonstrate that stages similar to maternal attachment occur and that fathers are more involved in child care when mothers are employed (although mothers continue to do the majority of infant care) (Jones and Heermann, 1992). Additional research has shown that inexperienced, first-time fathers are as capable as experienced fathers of developing a close attachment with their infants (Ferketich and Mercer, 1995). Studies of fathers of high-risk infants demonstrate that fathers experience feelings of love and affection toward their offspring during the newborn period; fathers in one study verbalized more positive feelings of love and affection toward the newborn when they were able to have close physical contact such as holding the child (Sullivan, 1999). The father has also been reported to have a significant role in supporting the mother in the perinatal period; fathers of high-risk infants reported concern about their mates’ well-being in addition to the status of the ill infant (Lundqvist and Jakobsson, 2003). Research demonstrates that fathers develop feelings of attachment with their offspring and that their relationship with the infant is an important factor in the mother’s emotional well-being. Breast-feeding mothers reported in one study that the most important factor in establishing and maintaining breast-feeding in early infancy was the father’s acceptance of breast-feeding and support for the mother (Arora, McJunkin, Wehrer, et al, 2000).

In one study children who had insecure attachment to their teenage mothers had a strong attachment to the grandmother who was also a primary caretaker (Patterson, 1997). With many single-parent families in existence, a grandmother (or other significant caretaker) may become the primary caretaker. It is important for nurses to recognize that infant-parent attachments may be present or absent in situations where caretaker roles are less well defined by those involved.

When the infant is not provided a safe haven and consistent and loving care, an insecure attachment develops; such infants do not feel they can trust the world in which they live. This insecure attachment may result in psychosocial difficulties as the child grows and may persist even into adulthood.

Attachment progresses during infancy, with the child assuming an increasingly significant role in the family. Two components of cognitive development are required for attachment: (1) the ability to discriminate the mother from other individuals and (2) the achievement of object permanence. Both these processes prepare the infant for an equally important aspect of attachment: separation from the parent. Separation-individuation should occur as a harmonious, parallel process with emotional attachment.

During the formation of attachment to the parent, the infant progresses through four distinct but overlapping stages. For the first few weeks infants respond indiscriminately to anyone. Beginning at approximately 8 to 12 weeks of age, they cry, smile, and vocalize more to the mother than to anyone else but continue to respond to others, whether familiar or not. At approximately 6 months of age, infants show a distinct preference for the mother. They follow her more, cry when she leaves, enjoy playing with her more, and feel most secure in her arms. About 1 month after showing attachment to the mother, many infants begin attaching to other members of the family, most often the father.

Infants acquire other developmental behaviors that influence the attachment process. These include (1) differential crying, smiling, and vocalization (more to mother than to anyone else); (2) visual-motor orientation (looking more at mother, even if she is not close); (3) crying when the mother leaves the room; (4) approaching through locomotion (crawling, creeping, or walking); (5) clinging (especially in presence of a stranger); and (6) exploring away from mother while using her as a secure base.

Effects of Prolonged Separation: Attachment is considered so critical to optimum child development that many researchers have documented the effects of prolonged and early separation on infants in the absence of high-quality parent substitutes. Some of the most famous research on emotional deprivation has been done by John Bowlby, John Robertson, and René Spitz. Bowlby (1969) studied the effects of the infant’s separation from the mother and noted severe cognitive and physical impairment, particularly if emotional deprivation occurred during the first 3 years of life. He observed that progressive impairment could be arrested or reversed if no further emotional deprivation occurred after the first 2 years, whereas prolonged, severe deprivation beginning early in the first year and lasting for 3 years led to severe, permanent effects. Among these were the inability to form trusting, intimate interpersonal relationships; language impairment; and deficiency in abstract thinking. Robertson (1953) and Bowlby (1969) found typical behavioral reactions of infants who were hospitalized and separated from their mothers. (See Separation Anxiety, Chapter 26.)

Spitz (1945) studied the effects of emotional deprivation on children raised in foundling homes or institutions. The infants were cared for by one nurse who had responsibility for eight children. Although the caregiver might be a loving, motherly person, she lacked the time to devote individual attention and stimulation to each child. As a result, the children were delayed in physical growth, were more susceptible to disease, and demonstrated decreasing developmental quotients over a 2-year period. Spitz found that children developed normally if given one-to-one attention by a mother substitute.

Although these studies represent extreme examples of young children reared in environments essentially devoid of high-quality mothering, rather than temporary separation such as daycare, the question remains regarding the long-term effects of separation and other stresses on children.

Reactive attachment disorder (RAD) is a psychologic and developmental problem that stems from maladaptive or absent attachment between the infant and parent (or primary caregiver) and may persist into childhood and even adulthood (Wilson, 2001; Zeanah and Fox, 2004). Infants at risk for RAD include those who have been victims of physical or sexual abuse or neglect; infants exposed to parental alcoholism, mental illness, and substance abuse; and infants who have experienced the absence of a consistent primary caregiver as a result of foster care, institutionalization, parental abandonment, or parental incarceration. RAD is a form of extreme insecure attachment. Two different patterns of RAD have emerged: the emotionally withdrawn–inhibited pattern and an indiscriminate-disinhibited pattern (Hornor, 2008; Zeanah and Fox, 2004). Signs of RAD usually occur before the age of 5 years in infants who had insecure attachments to the mother or other primary caretaker (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). The child may manifest behaviors such as not being cuddly with parents, failing to make eye contact with significant others, having poor impulse control, and being destructive to self and others. Without early intervention, some of these children fail to develop a conscience and suffer from an antisocial personality disorder that may lead to criminal acts. The American Psychiatric Association (2002) Position Statement on RAD emphatically recommends against the use of coercive holding therapies or rebirthing techniques for the treatment of RAD. It is not within the scope of this text to discuss every attachment disorder and associated therapies.

Based on such findings, nurses need to assess each family with the understanding that stress may or may not be necessarily harmful and that children can adapt even under adverse conditions. The nurse evaluates individual risk factors that influence a child’s coping ability, using tools such as the Revised Infant Temperament Questionnaire (see p. 478) to assess “goodness of fit.” When parental separation occurs, make every effort to help the family provide suitable caregiver substitutes for the child. Individuals who are warm, responsive, and interactive with the infant during separation can significantly minimize the physiologic and behavioral effects. The nurse emphasizes the child’s plasticity and resiliency in coping to minimize the family’s feelings of responsibility and guilt.

Separation Anxiety: Between the ages of 4 and 8 months the infant progresses through the first stage of separation-individuation and begins to have some awareness of self and mother as separate beings. At the same time, object permanence is developing, and the infant is aware that the parent can be absent. Therefore separation anxiety develops and is manifested through a predictable sequence of behaviors.

During the early second half of the first year infants protest when placed in their crib, and a short time later they object when the mother leaves the room. Infants may not notice the mother’s absence if they are absorbed in an activity. However, when they realize her absence, they protest. From this point on they become very alert to her activities and whereabouts. By 11 to 12 months they are able to anticipate her imminent departure by watching her behaviors, and they begin to protest before she leaves. At this point many parents learn to postpone alerting the child to their departure until just before leaving.

Stranger Fear: As infants demonstrate attachment to one person, they correspondingly exhibit less friendliness to others. Between ages 6 and 8 months fear of strangers and stranger anxiety become prominent and are related to infants’ ability to discriminate between familiar and unfamiliar people. Behaviors such as clinging to the parent, crying, and turning away from strangers are common (Fig. 12-11). Suggestions for coping with stranger fear and separation anxiety are on 1p. 480.

Language Development

The infant’s first means of verbal communication is crying. Crying as a biologic sign conveys a message of urgency and signals displeasure, such as hunger. However, crying is also a social event that affects the development of the parent-infant relationship—either by its absence, which usually has a positive effect on parents, or its presence, which may evoke a negative response or persuade parents to minister to the child’s physical or emotional needs.

In the first few weeks of life, crying has a reflexive quality and is mostly related to physiologic needs. Infants cry for 1 to  hr/day up to 3 weeks of age and then build up to 2 hours and even 4 hours by 6 weeks. Crying tends to decrease by 12 weeks. It is thought that the increase in crying for no apparent reason during the first few months may be related to the discharge of energy and the maturational changes in the central nervous system. By the end of the first year infants cry for attention; from fear (especially stranger fear); and from frustration, usually in response to their developing but inadequate motor skills.

hr/day up to 3 weeks of age and then build up to 2 hours and even 4 hours by 6 weeks. Crying tends to decrease by 12 weeks. It is thought that the increase in crying for no apparent reason during the first few months may be related to the discharge of energy and the maturational changes in the central nervous system. By the end of the first year infants cry for attention; from fear (especially stranger fear); and from frustration, usually in response to their developing but inadequate motor skills.

Many parents state that they can distinguish between different types of crying and from these messages are able to interpret the infant’s needs. However, crying can be a source of acute distress for parents, especially the inconsolable crying of colic. (See Chapter 13.) Parents benefit from an explanation of the variability of crying among infants and an assurance that periods of “unexplained fussiness” are normal. Some parents may need guidance in consoling techniques, such as holding, swaddling, massaging, caressing, rocking, walking, or stimulating sucking.

Vocalizations heard during crying eventually become syllables and words (e.g., the “mama” heard during vigorous crying). Infants vocalize as early as 5 to 6 weeks of age by making small throaty sounds. By 2 months they make single vowel sounds such as ah, eh, and uh. By 3 to 4 months the consonants n, k, g, p, and b are added, and the infants coo, gurgle, and laugh aloud. By 6 months they imitate sounds; add the consonants t, d, and w; and combine syllables (e.g., “dada”), but they do not ascribe meaning to the word until 10 to 11 months of age (see Family-Centered Care box). By 9 to 10 months they comprehend the meaning of the word “no” and obey simple commands accompanied by gestures. By age 1 year they can say three to five words with meaning and may understand as many as 100 words. Because language development is based on expressive (ability to make thoughts, ideas, and desires known to others) and receptive skills (ability to understand the words being spoken), it is important that infants are exposed to expressive speech and that delays in achieving milestones are carefully evaluated for potential hearing loss. (See Universal Newborn Hearing Screening, Chapter 8.)

Personal-Social Behavior

Personal-social behavior includes the child’s personal responses to the environment. It is the area most influenced by external stimuli but, as in the other fields of behavior, it follows certain developmental laws. Personal-social behavior implies communication with one’s self and with others. It provides the foundation for the successful mastery of skills such as feeding, control of bodily functions, independence, and cooperativeness in play.

Infants have the ability to shape their environment and to elicit certain responses. Newborns show visual preference for the human face and, as early as 1 week of age, begin to watch the parent intently as he or she speaks to them. As they regard the parent’s face, activity diminishes, their head bobs up and down, and their mouth moves, almost as if they were trying to say something.

By 6 to 8 weeks a social smile in response to pleasurable stimuli is present. This has a profound effect on family members and evokes continued responses from others. By 3 months infants show considerable interest in the environment—excitement when a toy is presented, refusal to be left alone, recognition of parent, and demonstration of pleasure by squealing. By 4 months they laugh aloud and enjoy strange, novel stimuli.

By 6 months infants are very personable. They play games such as peek-a-boo when their head is hidden in a towel, signal their desire to be picked up by extending their arms, and show displeasure when a toy is removed or their face is washed. They increasingly demonstrate their ability to control the environment. The acquisition of fine and gross motor skills allows much more independence in movement.

By the second half of the first year infants understand simple discipline, such as the meaning of the word “no” or a scolding remark. They comprehend different facial expressions and are sensitive to emotional changes in others. Imitation is developing during this time. They imitate actions and noises by 7 months, sounds by 8 months, and games such as pat-a-cake and peek-a-boo by 10 months.

From 11 months onward they are increasingly independent. They are learning to feed themselves; are using their fingers, spoon, and cup (with much spilling); and can help with dressing by putting the foot out for a shoe or pushing the arm through the sleeve. They not only comprehend the meaning of “no,” but also shake their head to indicate “no.” They can follow simple directions and gladly perform for others to attract and prolong attention.

Play

Play during infancy represents the various social modalities observed during cognitive development. Infants’ activity is primarily narcissistic and revolves around their own body. As discussed under Development of Body Image, body parts are primarily objects of play and pleasure.

During the first year, play becomes more sophisticated and interdependent. From birth to 3 months, infants’ responses to the environment are global and largely undifferentiated. Play is dependent; pleasure is demonstrated by a quieting attitude (1 month), a smile (2 months), and a squeal (3 months). From 3 to 6 months infants show more discriminate interest in stimuli and begin to play alone with a rattle or soft stuffed toy or with someone else. They interact much more during play. By 4 months of age they laugh aloud, show preference for certain toys, and become excited when food or a favorite object is brought to them. They recognize an image in a mirror, smile at it, and vocalize to it.

By 6 months to 1 year, play involves sensorimotor skills. Infants play actual games such as peek-a-boo and pat-a-cake. They demonstrate verbal repetition and imitation of simple gestures. Play is much more selective, not only in terms of specific toys but also in terms of “playmates.” Although play is solitary or one sided, infants choose with whom they will interact. At 6 to 8 months they usually refuse to play with strangers. Parents are definite favorites, and infants know how to attract their attention. At 6 months they extend the arms to be picked up, at 7 months cough to make their presence known, at 10 months pull the parent’s clothing, and at 12 months call them by name. This represents a tremendous advance from the newborn who signaled biologic needs by crying to express displeasure.

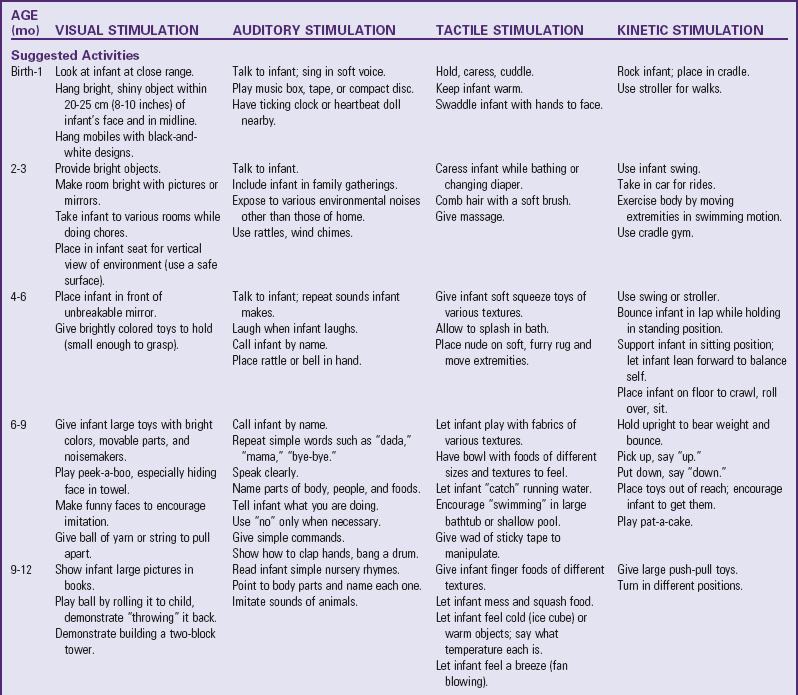

Stimulation is as important for psychosocial growth as food is for physical growth. Knowledge of developmental milestones allows nurses to guide parents regarding proper play for infants. It is not sufficient to place a mobile over a crib and toys in a playpen for a child’s optimum social, emotional, and intellectual development. Play must provide interpersonal contact and recreational and educational stimulation. Infants need to be played with, not merely be allowed to play. Although the type of play infants engage in is called solitary, this is only a figurative, not literal, term to denote one-sided play. The types of toys given to the child are much less important than the quality of personal interaction that occurs.

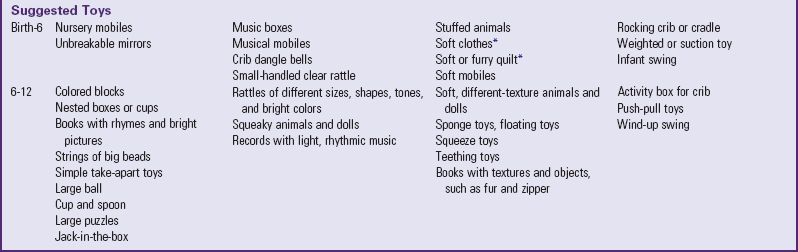

Table 12-2 lists play activities appropriate for the infant’s developmental level in terms of motor, language, and personal-social achievements. Although the activities are grouped according to the major mode of stimulation provided, many examples overlap. In addition, play activities suggested for one age-group may be appropriate for older infants but inappropriate for younger ones.

Temperament

The infant’s temperament or behavioral style influences the type of interaction that occurs between the child and parents and other family members. In assessing a child’s temperament, it is the parents’ perception of the child and the degree of fit between their expectations and the child’s actual temperament that are important. The more dissonance (or lack of harmony) between the child’s temperament and the parent’s ability to accept and deal with the behavior, the greater the risk for subsequent parent-child conflicts.

Although many behavioral researchers agree that temperament has a strong biologic component, researchers also suggest that the environment, particularly the family, may modify temperament (Wilson, White, Cobb, et al, 2000). Family interaction with the infant is perceived as a circular process wherein each family member affects each other and the family as a unit. With these concepts in mind, the nurse has an important role in helping the family understand the infant’s temperament as it relates to family dynamics and the eventual well-being of the child and family unit (Wilson, White, Cobb, et al, 2000).

Some researchers speculate that infant temperament may contribute to maternal depression. Indeed when there is a lack of reciprocity between the infant and the mother or when the infant’s behavior does not meet maternal expectations, there is increased risk for discord. Beck’s (2001) meta-analysis found that infant temperament was a mild risk factor for postpartum depression, whereas self-esteem, marital status, socioeconomic status, and unplanned or unwanted pregnancy were much more significant in predicting maternal depression. Recently, McGrath, Records, and Rice (2008) found that depressed mothers (versus nondepressed mothers) rated their infant’s temperament at 2 and 6 months of age as more difficult. The researchers stress that depressed mothers need to be identified and assisted in making the transition to motherhood and in developing synchronicity with their newborn infants.

The Revised Infant Temperament Questionnaire (RITQ) (Carey and McDevitt, 1978) can be used as a screening tool with parents. The questionnaire focuses on nine temperament variables, with 95 questions related specifically to activities such as sleep, feeding, play, diapering, and dressing. The scores from the RITQ help identify the child’s temperamental style. Use of the RITQ is well accepted by parents and should be accompanied by an adequate explanation of the results. In discussing the results, it is best to avoid descriptors such as “difficult” by describing such infants in terms of characteristics such as “intense” or “less predictable.” The Early Infancy Temperament Questionnaire is a 76-item parent questionnaire that was adapted from the RITQ to evaluate temperament characteristics of infants 1 to 4 months old, whereas the RITQ is best suited for infants 4 months old and older (Medoff-Cooper, Carey, and McDevitt, 1993).

With knowledge of the infant’s temperament, nurses are better able to (1) provide parents with background information that will help them see their child in a better perspective, (2) offer a more organized picture of their child’s behavior and possibly reveal distortions in their perceptions of the behavior, and (3) guide parents regarding appropriate childrearing techniques.

Childrearing Practices Related to Temperament

Most parents realize that their infant is born with unique characteristics, and few parents of difficult infants need to be told of the challenge of caring for them. However, most parents are unaware of the significance of the temperamental characteristics and of constructive approaches to dealing with them. The following are examples of interventions that promote more positive parenting of infants with different temperament styles.*

“Difficult” children may respond better to scheduled feedings and structured caregiving routines than demand feedings and frequent changes in daily routines. These children sleep less and may need more structured approaches to bedtime to prevent problems. Highly distractible children may require additional soothing measures such as swinging, rocking, or being carried in a pack that the parent wears across the chest or back. Children with high activity levels require vigilant watching, and parents need to take extra precautions in safeguarding the home. These children benefit from increased opportunities for gross motor activity to constructively channel their energy.

The child who is “slow to warm up” may demonstrate more stranger fear than other children and may require gradual and frequent preparation for new situations, such as substitute child care. Even the “easy child” can present problems in that the parents may need reminders to feed the child who sleeps for prolonged intervals and rarely cries. They may need to “retrain” the child because of the ease of developing habits such as keeping the child up late or sleeping with the young one, which may later become troublesome.

Appropriate counseling based on awareness of the child’s temperament can greatly enhance the quality of interaction between parents and infant. Even just letting parents know that difficult traits are instinctive can relieve feelings of guilt and incompetence (see Temperament, Chapter 14).

Knowledge of the developmental sequence allows the nurse to assess normal growth and minor or abnormal deviations. It also helps parents gain realistic expectations of their child’s ability, and provides guidelines for suitable play and stimulation. Parents who lack knowledge of child growth and development may set inappropriate behavioral expectations for their child. Emphasizing the child’s developmental rather than chronologic age strengthens the parent-child relationship by fostering trust and lessening frustration. Therefore thorough understanding and appreciation of children’s growth and development are essential.

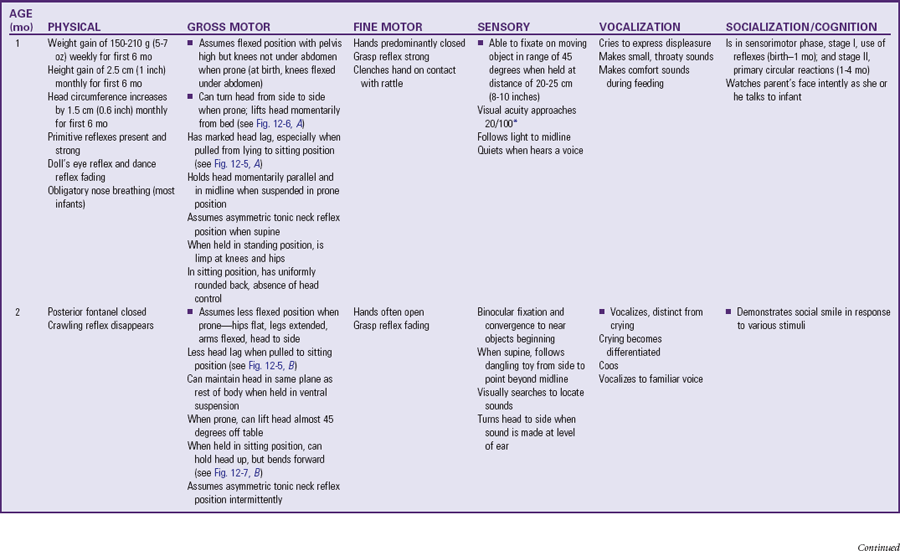

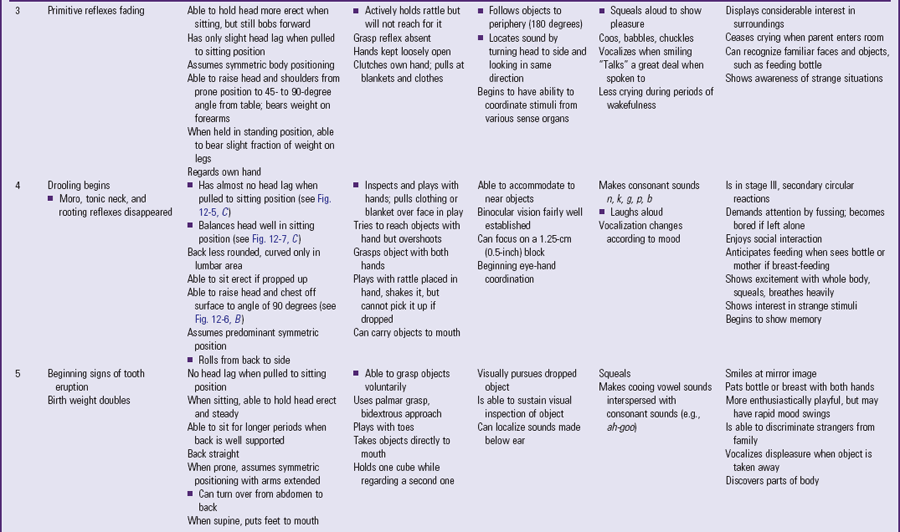

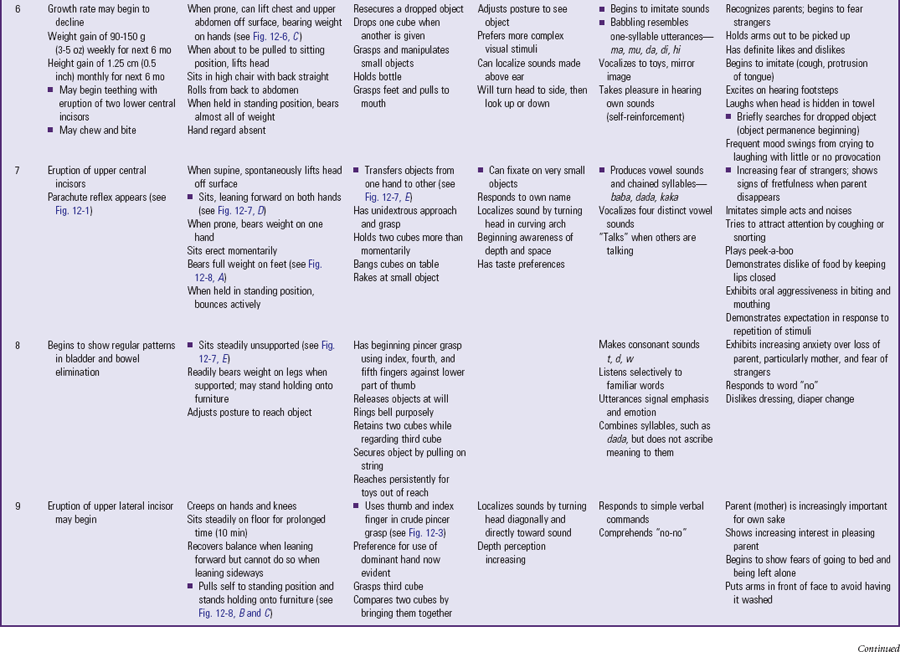

Because of the complexity of the developmental process during the first 12 months, Table 12-3 is presented to help organize and clarify the data already discussed. Although all milestones are important, some represent essential integrative aspects of development that lay the foundation for achievement of more advanced skills. These essential milestones are designated by a square ( ) in the table. The table represents the average monthly age at which infants attain various skills. Remember that, although the sequence is the same, the rate will vary among children.

) in the table. The table represents the average monthly age at which infants attain various skills. Remember that, although the sequence is the same, the rate will vary among children.

Coping with Concerns Related to Normal Growth and Development

Separation Anxiety and Stranger Fear

A number of fears can appear during infancy. However, the fear that causes many parents concern is related to strangers and separation. Although some erroneously interpret this as a sign of undesirable, antisocial behavior, stranger fear and separation anxiety are important components of a strong, healthy parent-child attachment. Nevertheless, this period can present difficulties for the parent and child. Parents may be more confined to the home because the infant violently protests having a baby-sitter. To accustom the infant to new people, encourage parents to have close friends or relatives visit often. This provides other persons with whom the child is comfortable and who can give parents time for themselves.

Infants also need opportunities to safely experience strangers. Usually toward the end of the first year infants begin to venture away from the parent and demonstrate curiosity about strangers. If allowed to explore at their own rate, many infants eventually “warm up.” If parents hold the child away from their face, the infant can observe while maintaining close physical contact.

A number of factors influence the intensity of a child’s stranger fears:

Gender, age, and size of the stranger—Female, younger age, and smaller size (including kneeling or sitting rather than standing) is less stressful.

Approach—Loud, sudden, intrusive approach causes more distress.

Child’s proximity to parent—Being closer to parent (on parent’s lap rather than in infant seat) is less stressful.

Consequently, the best approach for the stranger (including the nurse) is to talk softly; meet the child at eye level (to appear smaller); maintain a safe distance from the infant; and avoid sudden, intrusive gestures, such as holding the arms out and smiling broadly.

Parents also may wonder whether they should encourage the child’s clinging, dependent behavior, especially if there is pressure from others who view this as spoiling the child (see following discussion). Parents need reassurance that such behavior is healthy, desirable, and necessary for the child’s optimum emotional development. If parents can reassure the infant of their presence, the infant will learn to realize that they are still there even if not physically present. Talking to infants when leaving the room, allowing them to hear one’s voice on the telephone, and using transitional objects (e.g., a favorite blanket or toy) reassures them of the parent’s continued presence.

This is no less trying but a necessary time for infants, since parents cannot always be with them. An excellent example of necessary separation is bedtime. Fear of going to bed or being left alone in the dark commonly occurs during the second half of the first year. Fear at bedtime is only one of the many bedtime problems that can occur in young children (see p. 493 and Chapter 15).

Limit Setting and Discipline

As infants’ motor skills advance and mobility increases, parents are faced with the need to set safe limits (see Nurse’s Role in Injury Prevention, p. 516). Although numerous disciplinary techniques exist, some are more appropriate for this age than others. Parents can begin discipline using a negative voice and stern eye contact. When parents need to use more definitive measures, one of the most effective approaches is time-out. The basic principles are the same as those discussed in Chapter 3, except that the place for time-out needs to correspond with the child’s abilities. For example, the playpen is better for most infants than a chair. Although parents may be concerned with instituting discipline during infancy, it is important to stress that the earlier effective disciplinary methods are employed, the easier it is to continue these approaches.

Parents must recognize the infant’s cognitive and behavioral limitations and implement adequate protection from hazards because infants and toddlers do not understand a cause-and-effect relationship between dangerous objects and physical harm. Additionally, parents may need reassurance that their infant’s behavior is exploratory, not oppositional (at this age) and primarily centered on needs for warmth, love, food, security, and comfort. Parents may verbalize that comforting the infant too much or meeting his or her needs will result in a spoiled child; there is no substantial evidence that meeting the infant’s basic needs will result in such behaviors later in life. Children will innately test limits and explore during the exploratory phase of growth; instead of discouraging exploration, parents should provide safe alternatives, put away dangerous household items, and give children consistent discipline and nurturing. Effective teaching for injury prevention optimally begins in infancy by helping parents understand their child’s normal development. It must be reiterated continually that infants cry because a need is not being met, not to intentionally irritate an adult. The fussy or irritable infant is a potential victim of shaken baby syndrome (or other bodily harm), since adults and caretakers may not understand the nature of the infant’s crying.

A common concern of parents is that too much attention can spoil a child. Many of the recommendations for promoting attachment, such as attending to the infant’s needs to establish trust, accepting fear of strangers and separation from parent, and holding and rocking the crying child, are described by parents as methods of spoiling. However, research on parents’ response to crying during early infancy does not support the contention that picking up a crying baby leads to spoiling. Ainsworth (1982) found that the amount an infant cried during the first 3 months had no correlation with the frequency of crying during the rest of the first year. However, the degree of maternal responsiveness to crying did. Parents who were less responsive, such as not picking up the infant immediately on crying, had infants who cried more than those of parents who responded promptly to crying. Parents of colicky infants less than 3 months old who responded to the crying with increased attention successfully decreased the overall crying time.

If too much attention does not cause spoiling in early infancy, parents need to understand what “spoiling” really is and how it differs from normal behavior that may mimic aspects of spoiling. The spoiled child syndrome has been defined as “excessive self-centered and immature behavior, resulting from the failure of parents to enforce consistent, age-appropriate limits” (McIntosh, 1989). Spoiled children demand to have their own way; are inconsiderate of others; and have intrusive, obstructive, and manipulative behavior. Indulging children, when combined with clear expectations and limits, does not cause spoiling. However, indulgence with failure to provide guidelines for acceptable behavior can result in a child who expects to get her or his way all the time. Such expectations are unrealistic and do not help the child in the transition to older childhood, adolescence, and adulthood.

Several age-related normal behaviors and child characteristics can be mistaken for evidence of spoiling:

• Crying during early infancy that may or may not be associated with colic

• Toddler behaviors such as negativism, persistent exploration, and temper tantrums

• Children with difficult temperaments or ADHD

• Children experiencing extreme stress from marital discord; physical, emotional, or sexual abuse; substance abuse; or mental illness in a parent

With anticipatory guidance regarding expected but challenging behaviors and situations that may produce extreme stress in children, parents should feel comfortable in loving their infant without fear of spoiling. However, as the infant gets older, parents may need assistance in providing limits that prevent normal, disruptive behaviors, such as temper tantrums, from becoming problems.

Alternative Child Care Arrangements

For many parents, especially working mothers, locating safe and competent child care facilities for the infant is a challenge—one that is compounded by the number of mothers working outside the home. Over the past 40 years a marked shift has occurred in child care arrangements, with fewer children cared for at home and more children cared for in group centers or other settings.

Types of Child Care: The basic types of care are in-home care, either in the parents’ or caregivers’ home (family daycare), and center-based care, usually in a daycare center. In-home care may consist of a full-time baby-sitter who lives in the home, a full-time baby-sitter who comes to the home, cooperative arrangements such as exchange baby-sitting, and family daycare. A licensed small family child daycare home typically provides care and protection for up to six children for part of a day and does not include informal arrangements such as exchange baby-sitting or caregivers in the child’s own home. The six children include the family daycare provider’s own children younger than 5 years of age living in the home. Large family child care homes may provide care for 8 to 12 children. Unfortunately, many family daycare homes operate without a license and may care for large numbers of infants without adequate staff and facilities.

Child center-based care usually refers to a licensed daycare facility that provides care for six or more children, for 6 or more hours a day. Work-based group care is another option that is becoming increasingly popular as employers recognize the benefit of providing high-quality and convenient child care to their employees. Sick-child care may also be available for times when the youngster is ill. Such programs are often located in community hospitals or in work settings.

Guiding Parents in Selecting Child Care: An important nursing responsibility is guiding parents in locating suitable facilities that have a well-qualified staff. State licensing agencies can help parents identify daycare centers that accept children of specific age-groups and are convenient to home and work. Their records are available to the public and provide reports from the health, safety, and fire departments; periodic evaluations from the licensing agency; complaints filed against the center; and qualification of the center’s employees. State-licensed programs are supposed to follow established standards, which represent the minimum requirements and safeguards. However, enforcement of the standards is sometimes inadequate. Early childhood programs may also belong to a voluntary accreditation system, the National Academy of Early Childhood Programs/NAEYC,* which serves as a model for optimum care. References from other parents are also helpful, provided they have investigated the center carefully and have remained involved with the agency’s activities.