Inflammatory Bowel Disease

IBD should not be confused with IBS. IBD is a term used to refer to two major forms of chronic intestinal inflammation: CD and ulcerative colitis (UC). CD and UC have similar epidemiologic, immunologic, and clinical features, but they are distinct disorders.

In addition to GI symptoms, both CD and UC are characterized by extraintestinal and systemic inflammatory responses. Exacerbations and remissions without complete resolution are also characteristics of IBD. Growth failure, particularly common in CD, is an important problem unique to the pediatric population. CD is also more disabling, has more serious complications, and is often less amenable to medical and surgical treatment than is UC. Because UC is confined to the colon, theoretically it may be cured by a colectomy.

The prevalence of IBD is between 12 and 40 per 100,000 persons, with 25% of these individuals being diagnosed before 20 years of age (Wong, Clark, Garnett, et al, 2009). Over the past 30 years the incidence of CD has risen, while the incidence of UC in children has remained stable. Children 6 to 17 years of age with CD appear to have a more complicated disease course compared with that of 0- to 5-year-old children (Gupta, Bostrom, Kirschner, et al, 2008).

Etiology

Despite decades of research, the etiology of IBD is not completely understood, and there is no known cure. There is evidence to indicate a multifactorial etiology. Research is focused on theories of defective immunoregulation of the inflammatory response to bacteria or viruses in the GI tract in individuals with a genetic predisposition (Silbermintz and Markowitz, 2006). In CD the chronic immune process is characterized by a T helper 1 cytokine profile, whereas in UC the response is more humoral and mediated by T helper 2 cells (Silbermintz and Markowitz, 2006).

Development of IBD has a genetic influence. Several IBD susceptibility genes have now been identified through family and twin studies (Sauer and Kugathasan, 2010). Family-based genetic studies have linked chromosome 6 in UC and the NOD2 gene in CD (Sauer and Kugathasan, 2010).

Pathophysiology

The inflammation found with UC is limited to the colon and rectum, with the distal colon and rectum the most severely affected. Inflammation affects the mucosa and submucosa and involves continuous segments along the length of the bowel with varying degrees of ulceration, bleeding, and edema. Thickening of the bowel wall and fibrosis are unusual, but longstanding disease can result in shortening of the colon and strictures. Extraintestinal manifestations are less common in UC than in CD. Toxic megacolon is the most dangerous form of severe colitis.

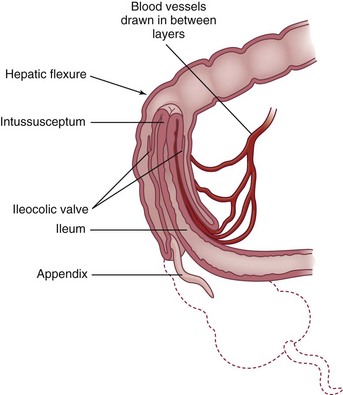

The chronic inflammatory process of CD involves any part of the GI tract from the mouth to the anus but most often affects the terminal ileum. The disease involves all layers of the bowel wall (transmural) in a discontinuous fashion, meaning that between areas of intact mucosa, there are areas of affected mucosa (skip lesions). The inflammation may result in ulcerations; fibrosis; adhesions; stiffening of the bowel wall; stricture formation; and fistulas to other loops of bowel, bladder, vagina, or skin.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

Children with UC may experience mild, moderate, or severe symptoms, depending on the extent of mucosal inflammation and systemic symptoms. Most include bloody diarrhea or occult fecal blood, abdominal pain, and varying degrees of systemic manifestations and growth abnormalities (Beattie, Croft, Fell, et al, 2006; Leichtner and Higuchi, 2004). One of the earliest signs of UC may be growth failure with decreased linear growth velocity (Beattie, Croft, Fell, et al, 2006). Growth failure is most likely a result of chronic poor dietary intake caused by anorexia related to GI symptoms. UC often manifests with the insidious onset of diarrhea, possibly with hematochezia, and usually without fever or weight loss. The course of the disease may remain mild with intermittent exacerbations. Some children and adolescents are seen with grossly bloody diarrhea, cramps, urgency with defecation, mild anemia, fever, anorexia, weight loss, and moderate signs of systemic illness. Severe UC is characterized by frequent bloody stools, abdominal pain, significant anemia, fever, and weight loss. Extraintestinal manifestations are less common in UC than in CD and may precede colitis. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) may be elevated, indicating a systemic response to an inflammatory process. Enlarged lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy), arthritis, and the skin lesions of erythema nodosum may be present.

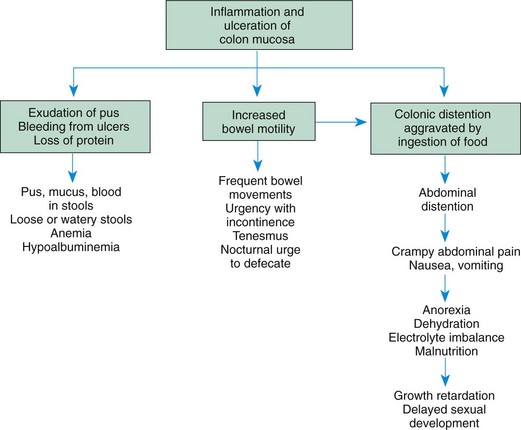

Common presenting manifestations of CD include diarrhea, abdominal pain with cramps, fever, and weight loss. Mild GI symptoms, poor growth, and extraintestinal manifestations may be present for several years before overt GI symptoms are present. Both malabsorption and anorexia are factors that contribute to the growth problems that are prevalent in CD. The effects of UC and CD are listed in Fig. 33-4.

Children with CD have multiple risk factors for impaired bone accrual, including poor growth, delayed maturation, malnutrition, decreased activity, chronic inflammation, and steroid therapy (Dubner, Shults, Baldassano, et al, 2009). Growth delay persists in many children with CD following diagnosis, despite improved disease activity (Pfefferkorn, Burke, Griffiths, et al, 2009).

The disease process can also involve the colon, causing diarrhea, cramps, and urgency with defecation. Signs of colitis, such as gross rectal bleeding or stool with occult blood, are similar to those seen in UC. Perianal disease, including skin tags, abscesses, fissures, and fistulas, is a feature of CD. Extraintestinal manifestations include erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, arthralgia and arthritis, uveitis and episcleritis, sclerosing cholangitis, autoimmune hepatitis, nephrolithiasis, and pneumonitis (Silbermintz and Markowitz, 2006). Table 33-2 provides a comparison of UC and CD.

TABLE 33-2

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASES

| CHARACTERISTICS | ULCERATIVE COLITIS | CROHN DISEASE |

| Rectal bleeding | Common | Uncommon |

| Diarrhea | Often severe | Moderate to severe |

| Pain | Less frequent | Common |

| Anorexia | Mild or moderate | May be severe |

| Weight loss | Moderate | May be severe |

| Growth retardation | Usually mild | May be severe |

| Anal and perianal lesions | Rare | Common |

| Fistulas and strictures | Rare | Common |

| Rashes | Mild | Mild |

| Joint pain | Mild to moderate | Mild to moderate |

Diagnostic Evaluation

The diagnosis of UC and CD comes from the history, physical examination, laboratory evaluation, and other diagnostic procedures. Laboratory tests include a CBC to evaluate anemia and an ESR or CRP to assess the systemic reaction to the inflammatory process. Levels of total protein, albumin, iron, zinc, magnesium, vitamin B12, and fat-soluble vitamins may be low in children with CD. Stools are examined for blood, leukocytes, and infectious organisms. A serologic panel is often used in combination with clinical findings to diagnose IBD and to differentiate between CD and UC. Observational studies on the utility of blood tests to detect perinuclear antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies (pANCA) and anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCA) showed that the combination is specific, but not sensitive for diagnosing ulcerative colitis (Reese, Constantinides, Simillis, et al, 2006).

In patients with CD, an upper GI series with small bowel follow-through assists in assessing the existence, location, and extent of disease. Upper endoscopy and colonoscopy with biopsies are an integral part of diagnosing IBD (Langan, Gotsch, Krafczyk, et al, 2007). Endoscopy allows direct visualization of the surface of the GI tract so that the extent of inflammation and narrowing can be evaluated. CT and ultrasound also may be used to identify bowel wall inflammation, intraabdominal abscesses, and fistulas. CD lesions may pierce the walls of the small intestine and colon, creating tracts called fistulas between the intestine and adjacent structures such as the bladder, anus, vagina, or skin.

Therapeutic Management

The natural history of the disease continues to be unpredictable and characterized by recurrent flare-ups that can severely impair patients’ physical and social functioning (Vernier-Massouille, Balde, Salleron, et al, 2008). The goals of therapy are to (1) control the inflammatory process to reduce or eliminate the symptoms, (2) obtain long-term remission, (3) promote normal growth and development, and (4) allow as normal a lifestyle as possible. Treatment is individualized and managed according to the type and the severity of the disease, its location, and the response to therapy.

Medical Treatment: The goal of any treatment regimen is first to induce remission of acute symptoms and then to maintain remission over time. 5-Aminosalicylates (5-ASAs) are effective in the induction and maintenance of remission in mild to moderate UC. Mesalamine, olsalazine, and balsalazide are now preferred over sulfasalazine because of reduced side effects (headache, nausea, vomiting, neutropenia, and oligospermia). Suppository and enema preparations of mesalamine are used to treat left-sided colitis. These drugs decrease inflammation by inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis. 5-ASAs can be used to induce remission in mild CD. Corticosteroids, such as prednisone and prednisolone, are indicated in induction therapy in children with moderate to severe UC and CD. These drugs inhibit the production of adhesion molecules, cytokines, and leukotrienes. Although these drugs reduce the acute symptoms of IBD, they have side effects that relate to long-term use, including growth suppression (adrenal suppression), weight gain, and decreased bone density (Baron, 2002). High doses of IV corticosteroids may be administered in acute episodes and tapered according to clinical response. Budesonide, a synthetic corticosteroid, is designed for controlled release in the ileum and is indicated for ileal and right-sided colitis; budesonide has fewer side effects than prednisone and prednisolone (Silbermintz and Markowitz, 2006). Rectal steroid therapy (enemas and foam-based preparations) are available for both induction and maintenance therapy in left-sided colitis.

Immunomodulators, such as azathioprine and its metabolite 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP), are used to induce and maintain remission in children with IBD who are steroid resistant or steroid dependent and in treating chronic draining fistulas. They block the synthesis of purine, thus inhibiting the ability of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA) to hinder lymphocyte function, especially that of T cells. Side effects include infection, pancreatitis, hepatitis, bone marrow toxicity, arthralgia, and malignancy. Methotrexate is also useful in inducing and maintaining remission in CD patients unresponsive to standard therapies. Cyclosporine and tacrolimus have both been effective in inducing remission in severe steroid-dependent UC. 6-MP or azathioprine is then used to maintain remission. Patients on immunomodulating medications require regular monitoring of their CBC and differential to assess for changes that reflect suppression of the immune system, since many of the side effects can be prevented or managed by dose reduction or discontinuation of medication.

Antibiotics, such as metronidazole and ciprofloxacin, may be used as an adjunctive therapy to treat complications such as perianal disease or small bowel bacterial overgrowth in CD. Side effects of these drugs are peripheral neuropathy, nausea, and a metallic taste.

Biologic therapies act to regulate inflammatory and antiinflammatory cytokines. With the emergence of the biologic agents, specifically the use of antitumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) agents, progress has been made in targeting specific pathogenetic mechanisms and achieving a more prolonged clinical response (Ricart, García-Bosch, Ordás, et al, 2008; Hyams and Markowitz, 2005). TNF-α is believed to influence active inflammation.

Nutritional Support: Nutritional support is important in the treatment of IBD. Growth failure is a common serious complication, especially in CD. Growth failure is characterized by weight loss, alteration in body composition, retarded height, and delayed sexual maturation. Malnutrition causes the growth failure, and its etiology is multifactorial. Malnutrition occurs as a result of inadequate dietary intake, excessive GI losses, malabsorption, drug-nutrient interaction, and increased nutritional requirements. Inadequate dietary intake occurs with anorexia and episodes of increased disease activity. Excessive loss of nutrients (protein, blood, electrolytes, and minerals) occurs secondary to intestinal inflammation and diarrhea. Carbohydrate, lactose, fat, vitamin, and mineral malabsorption, as well as vitamin B12 and folic acid deficiencies, occur with disease episodes and with drug administration and when the terminal ileum is resected. Finally, nutritional requirements are increased with inflammation, fever, fistulas, and periods of rapid growth (e.g., adolescence).

The goals of nutritional support include (1) correction of nutrient deficits and replacement of ongoing losses, (2) provision of adequate energy and protein for healing, and (3) provision of adequate nutrients to promote normal growth. Nutritional support includes both enteral and parenteral nutrition. A well-balanced, high-protein, high-calorie diet is recommended for children whose symptoms do not prohibit an adequate oral intake. There is little evidence that avoiding specific foods influences the severity of the disease. Supplementation with multivitamins, iron, and folic acid is recommended.

Special enteral formulas, given either by mouth or continuous NG infusion (often at night), may be required. Elemental formulas are completely absorbed in the small intestine with almost no residue. A diet consisting only of elemental formula not only improves nutritional status but also induces disease remission, either without steroids or with a diminished dosage of steroids required. An elemental diet is a safe and potentially effective primary therapy for patients with CD. Unfortunately, remission is not sustained when NG feedings are discontinued unless maintenance medications are added to the treatment regimen.

TPN has also improved nutritional status in patients with IBD. Short-term remissions have been achieved after TPN, although complete bowel rest has not reduced inflammation or added to the benefits of improved nutrition by TPN. Nutritional support is less likely to induce a remission in UC than in CD. Improvement of nutritional status is important, however, in preventing deterioration of the patient’s health status and in preparing the patient for surgery.

Surgical Treatment: Surgery is indicated for UC when medical and nutritional therapies fail to prevent complications. Surgical options include a subtotal colectomy and ileostomy that leaves a rectal stump as a blind pouch. A reservoir pouch is created in the configuration of a J or S to help improve continence postoperatively. An ileoanal pull-through preserves the normal pathway for defecation. Pouchitis, an inflammation of the surgically created pouch, is the most common late complication of this procedure and had been reported to occur in up to 50% of cases. In many cases UC can be cured with a total colectomy.

Surgery may be required in children with CD when complications cannot be controlled by medical and nutritional therapy. Segmental intestinal resections are performed for small bowel obstructions, strictures, or fistulas. Partial colonic resection is not curative, and the disease often recurs.

Prognosis: IBD is a chronic disease. Relatively long periods of quiescent disease may follow exacerbations. The outcome is influenced by the regions and severity of involvement, as well as by appropriate therapeutic management. Malnutrition, growth failure, and bleeding are serious complications. The overall prognosis for UC is good.

The development of colorectal cancer (CRC) is a long-term complication of IBD. In UC, the cumulative incidence of CRC is 2.5% after 20 years, increasing to 10.8% after 30 years (Rutter, Saunders, Wilkinson, et al, 2006). Surveillance colonoscopy with multiple biopsies should begin approximately 10 years after diagnosis of UC or Crohn colitis and continue every 1 to 2 years (Rubin and Kavitt, 2006). Removal of the diseased colon prevents development of CRC. In CD, however, surgical removal of the affected colon does not prevent cancer from developing elsewhere in the GI tract.

Nursing Care Management

The nursing considerations in the management of IBD extend beyond the immediate period of hospitalization. These interventions involve continued guidance of families in terms of (1) managing diet; (2) coping with factors that increase stress and emotional lability; (3) adjusting to a disease of remissions and exacerbations; and (4) when indicated, preparing the child and parents for the possibility of diversionary bowel surgery.

Because nutritional support is an essential part of therapy, encouraging the anorexic child to consume sufficient quantities of food is often a challenge. Successful interventions include involving the child in meal planning; encouraging small, frequent meals or snacks rather than three large meals a day; serving meals around medication schedules when diarrhea, mouth pain, and intestinal spasm are controlled; and preparing high-protein, high-calorie foods such as eggnog, milkshakes, cream soups, puddings, or custard (if lactose is tolerated). (See Feeding the Sick Child, Chapter 27.) Using bran or a high-fiber diet for active IBD is questionable. Bran, even in small amounts, has been shown to worsen the patient’s condition. Occasionally the occurrence of aphthous stomatitis further complicates adherence to dietary management. Mouth care before eating and the selection of bland foods help relieve the discomfort of mouth sores.

When NG feedings or TPN is indicated, nurses play an important role in explaining the purpose and the expected outcomes of this therapy. The nurse should acknowledge the anxieties of the child and family members and give them adequate time to demonstrate the skills necessary to continue the therapy at home if needed (see Critical Thinking Exercise).

The importance of continued drug therapy despite remission of symptoms must be stressed to the child and family members. Failure to adhere to the pharmacologic regimen can result in exacerbation of the disease. (See Compliance, Chapter 27.) Unfortunately, exacerbation of IBD can occur even if the child and family are compliant with the treatment regimen; this is difficult for the child and family to cope with.

Family Support: The nurse should attend to the emotional components of the disease and assess any sources of stress. Frequently, the nurse can help children adjust to problems of growth retardation, delayed sexual maturation, dietary restrictions, feelings of being “different” or “sickly,” inability to compete with peers, and necessary absence from school during exacerbations of the illness.

If a permanent colectomy-ileostomy is required, the nurse can teach the child and family how to care for the ileostomy. The nurse can also emphasize the positive aspects of the surgery, particularly accelerated growth and sexual development, permanent recovery, the eliminated risk of colonic cancer in UC, and the normality of life despite bowel diversion. Introducing the child and parents to other ostomy patients, especially those who are the same age, is effective in fostering eventual acceptance. Whenever possible, offer continent ostomies as options to the child, although they are not performed in all centers in the United States.

Because of the chronic and often life-long nature of the disease, families benefit from the educational services provided by organizations such as the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America (CCFA).* If diversionary bowel surgery is indicated, United Ostomy Associations of America† and the Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society‡ are available to assist with ileostomy care and provide important psychologic support through their self-help groups. Adolescents often benefit by participating in peer-support groups, which are sponsored by the CCFA.

Peptic Ulcer Disease

Peptic ulcers may be classified as acute or chronic, and peptic ulcer disease (PUD) is a chronic condition that affects the stomach or duodenum. Ulcers are described as gastric or duodenal and as primary or secondary. A gastric ulcer involves the mucosa of the stomach; a duodenal ulcer involves the pylorus or duodenum. Most primary ulcers occur in the absence of a predisposing factor and tend to be chronic, occurring more frequently in the duodenum. Stress ulcers result from the stress of a severe underlying disease or injury (e.g., severe burns, sepsis, increased intracranial pressure, severe trauma, multisystem organ failure) and are more frequently acute and gastric.

About 1.7% of children in general pediatric practices have PUD, and the disease represents about 3.4% per 10,000 pediatric hospital admissions. Primary ulcers are more common in children older than 6 years, and stress ulcers are more common in infants younger than 6 months. Except for very young children, the incidence is two to three times greater in boys than in girls.

Etiology

The exact cause of PUD is unknown, although infectious, genetic, and environmental factors are important. There is an increased familial incidence, and the disease is increased in persons with blood group O.

There is a significant relationship between the bacterium Helicobacter pylori and ulcers. H. pylori is a microaerophilic, gram-negative, slow-growing, spiral-shaped, and flagellated bacterium known to colonize the gastric mucosa in about half of the population of the world (Sung, Kuipers, and El-Serag, 2009). H. pylori synthesizes the enzyme urease, which hydrolyses urea to form ammonia and carbon dioxide. Ammonia then absorbs acid to form ammonium, thus raising the gastric pH. H. pylori may cause ulcers by weakening the gastric mucosal barrier and allowing acid to damage the mucosa. It is believed that it is acquired via the fecal-oral route, and this hypothesis is supported by finding viable H. pylori in feces.

In addition to ulcerogenic drugs, both alcohol and smoking contribute to ulcer formation. There is no conclusive evidence to implicate particular foods, such as caffeine-containing beverages or spicy foods, but polyunsaturated fats and fiber may play a role in ulcer formation. Psychologic factors may play a role in the development of PUD, and stressful life events, dependency, passiveness, and hostility have all been implicated as contributing factors.

Pathophysiology

Most likely, the pathologic condition is due to an imbalance between the destructive (cytotoxic) factors and defensive (cytoprotective) factors in the GI tract. The toxic mechanisms include acid, pepsin, medications such as aspirin and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), bile acids, and infection with H. pylori. The defensive factors include the mucus layer, local bicarbonate secretion, epithelial cell renewal, and mucosal blood flow. Prostaglandins play a role in mucosal defense because they stimulate both mucus and alkali secretion. The primary mechanism that prevents the development of peptic ulcer is the secretion of mucus by the epithelial and mucus glands throughout the stomach. The thick mucus layer acts to diffuse acid from the lumen to the gastric mucosal surface, thus protecting the gastric epithelium. The stomach and the duodenum produce bicarbonate, decreasing acidity on the epithelial cells and thereby minimizing the effects of the low pH (Chelimsky and Czinn, 2001). When abnormalities in the protective barrier exist, the mucosa is vulnerable to damage by acid and pepsin. Exogenous factors, such as aspirin and NSAIDs, cause gastric ulcers by inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis.

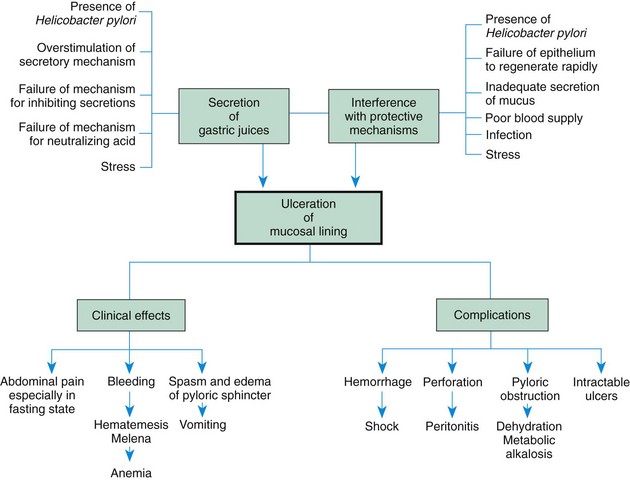

Zollinger-Ellison syndrome may occur in children who have multiple, large, or recurrent ulcers. This syndrome is characterized by hypersecretion of gastric acid, intractable ulcer disease, and intestinal malabsorption caused by a gastrin-secreting tumor of the pancreas. The pathogenesis, manifestations, and complications of PUD are outlined in Fig. 33-5.

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical manifestations of PUD vary according to the child’s age and the ulcer’s location. Common clinical manifestations include chronic abdominal pain, especially when the stomach is empty, such as during the night or early morning; recurrent vomiting; hematemesis; melena; chronic anemia; and abdominal tenderness (Box 33-9).

Diagnostic Evaluation

Diagnosis is based on the history of symptoms, physical examination, and diagnostic testing. The focus is on symptoms such as epigastric abdominal pain, nocturnal pain, oral regurgitation, heartburn, weight loss, hematemesis, and melena. History should include questions relating to the use of potentially causative substances such as NSAIDS, corticosteroids, alcohol, and tobacco. Laboratory studies may include a CBC to detect anemia, stool analysis for occult blood, liver function tests (LFTs), sedimentation rate, or CRP to evaluate IBD; amylase and lipase to evaluate pancreatitis; and gastric acid measurements to identify hypersecretion. A lactose breath test may be performed to detect lactose intolerance.

Radiographic studies such as an upper GI series may be performed to evaluate obstruction or malrotation. An upper endoscopy is the most reliable procedure to diagnose PUD. A biopsy can determine the presence of H. pylori. A blood test can also identify the presence of the antigen to this organism. The 13C urea breath test measures bacterial colonization in the gastric mucosa. This test is used to screen for H. pylori in adults and children. Polyclonal and monoclonal stool antigen tests are an accurate, noninvasive method both for the initial diagnosis of H. pylori and for the confirmation of its eradication after treatment (Gisbert, de la Morena, and Abraira, 2006).

Diagnosis is based on the history (pattern of pain) and physical examination. Frequently a history of epigastric and periumbilical pain accompanies PUD. However, children often find it difficult to describe the location of their pain and frequently indicate the location by moving their hand in a circular movement all around the stomach area. Asking the child to take one finger and point to the area where it hurts the most often helps to identify the location of the pain. Pain may also be elicited during the examination with palpation. Routine laboratory studies to diagnose PUD include a CBC with differential, ESR, blood chemistry studies, urinalysis, and stool analysis to identify anemia or inflammation and to rule out infection. A 13C urea breath test is often performed to determine the presence of antibodies to H. pylori. An upper GI series is rarely helpful in identifying ulcers in children; fiberoptic endoscopy is the most reliable way to detect PUD in children. Direct visualization of the gastric and duodenal mucosa with biopsy to determine the presence of H. pylori is the most commonly used and effective way to arrive at the diagnosis.

Therapeutic Management

The major goals of therapy for children with PUD are to relieve discomfort, promote healing, prevent complications, and prevent recurrence. Management is primarily medical and consists of administration of medications to treat the infection and to reduce or neutralize gastric acid secretion. Antacids are beneficial medications to neutralize gastric acid. Histamine (H2) receptor antagonists (antisecretory drugs) act to suppress gastric acid production. Cimetidine, ranitidine, and famotidine are examples of these medications. These medications have few side effects.

PPIs, such as omeprazole and lansoprazole, act to inhibit the hydrogen ion pump in the parietal cells, thus blocking the production of acid. Although these drugs have not been well studied in children, thy are utilized in clinical practice to treat ulcers, GER, esophagitis, and gastritis. They appear to be well tolerated and to have infrequent side effects (e.g., headache, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting).

Mucosal protective agents, such as sucralfate and bismuth-containing preparations, may be prescribed for PUD. Sucralfate is an aluminum-containing agent that forms a barrier over ulcerated mucosa to protect against acid and pepsin. Sucralfate is available in both pill and liquid forms. Because sucralfate blocks the absorption of other medications, it should be given separately from other medications.

Bismuth compounds are sometimes prescribed for the relief of ulcers, but they are used less frequently than PPIs. Although these compounds inhibit the growth of microorganisms, the mechanism of their activity is poorly understood. In combination with antibiotics, bismuth is effective against H. pylori. Although concern has been expressed about the use of bismuth salts in children because of potential side effects, none of these side effects has been reported when these compounds have been used in the treatment of H. pylori infection.

Triple-drug therapy is the standard first-line treatment regimen for H. pylori (O’Connor, Gisbert, and O’Morain, 2009). Combination therapy has demonstrated 90% effectiveness in eradication of H. pylori when compared with antibiotic monotherapy. Examples of drug combinations used in triple therapy are (1) bismuth, clarithromycin, and metronidazole; (2) lansoprazole, amoxicillin, and clarithromycin; and (3) metronidazole, clarithromycin, and omeprazole. The benefits on the use of probiotics as an adjunct to treatment remain unclear, with conflicting literature on their effect on eradication and minimizing side effects (O’Connor, Gisbert, and O’Morain, 2009).

Common side effects of medications include diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting. In addition to medications, the child with PUD should have a nutritious diet and avoid caffeine. Warn adolescents about gastric irritation associated with alcohol use and smoking.

Children with an acute ulcer who have developed complications, such as massive hemorrhage, require emergency care. The administration of IV fluids, blood, or plasma depends on the amount of blood loss. Replacement with whole blood or packed cells may be necessary for significant loss.

Surgical intervention may be required for complications such as hemorrhage, perforation, or gastric outlet obstruction. Ligation of the source of bleeding or closure of a perforation is performed. A vagotomy and pyloroplasty may be indicated in children with recurring ulcers despite aggressive medical treatment.

Prognosis: The long-term prognosis for PUD is variable. Many ulcers are successfully treated with medical therapy; however, primary duodenal peptic ulcers often recur. Complications such as GI bleeding can occur and extend into adult life. The effect of maintenance drug therapy on long-term morbidity remains to be established with further studies.

Nursing Care Management

The primary nursing goal is to promote healing of the ulcer through compliance with the medication regimen. If an analgesic-antipyretic is needed, acetaminophen, not aspirin or NSAIDs, is used. Critically ill neonates, infants, and children in intensive care units should receive H2 blockers to prevent stress ulcers.

For nonhospitalized children with chronic illnesses, consider the role stress plays. In children, many ulcers occur secondary to other conditions, and the nurse should be aware of family and environmental conditions that may aggravate or precipitate ulcers. Children may benefit from psychologic counseling and from learning how to cope constructively with stress.