The Child with Gastrointestinal Dysfunction

http://evolve.elsevier.com/wong/ncic

Alternative Feeding Techniques, Ch. 27

Cystic Fibrosis, Ch. 32

Disorders of the Gastrointestinal Tract, Ch. 11

Encopresis, Ch. 18

Feeding Resistance, Ch. 10

Gastrointestinal Disorders, Ch. 29

Intestinal Parasitic Diseases, Ch. 16

Nursing Care of High-Risk Newborns, Ch. 10

Ostomies, Ch. 27

Pain Assessment; Pain Management, Ch. 7

Preparation for Diagnostic and Therapeutic Procedures, Ch. 27

Procedures Related to Elimination, Ch. 27

Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, Ch. 13

Surgical Procedures, Ch. 27

Venous Access Devices, Ch. 28

Gastrointestinal Structure and Function

The primary function of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is the digestion and absorption of nutrients. The GI tract also has secretory, barrier, endocrine, and immunologic functions (Box 33-1). The extensive surface area of the GI tract and its digestive function represent the major means of exchange between the human organism and the environment. Thus any dysfunction of the GI tract can cause significant problems with the exchange of fluids, electrolytes, and nutrients.

Development of the Gastrointestinal Tract

The development of the GI tract (from mouth to anus) occurs in several stages from conception through birth. The GI tract may be divided into three parts in intrauterine life: foregut (esophagus, stomach, and proximal duodenum), midgut (distal duodenum, jejunum, ileum, cecum, and proximal colon), and hindgut (distal colon and rectum). The salivary glands, liver, gallbladder, and pancreas are outgrowths of the foregut and midgut.

The esophagus develops from the foregut and can be identified by 4 weeks of gestation. It elongates rapidly after the fourth week to a length of approximately 10 cm (4 inches) at term. The stomach also develops from the primitive foregut and can be identified by the fourth week of gestation. It continues to develop in the second trimester. From the fifth week of gestation until term, the intestine lengthens a thousandfold.

The third trimester is the period of most extensive and rapid growth of the gut. At full term, the small intestine is approximately 250 to 300 cm (98 to 118 inches) and will grow to approximately 2 to 4 m (6.5 to 13 feet) in the adult. The large intestine develops from the midgut and the hindgut and is approximately 30 to 50 cm (12 to 20 inches) at term.

During pregnancy the fetus receives nutrients via the placenta. At birth the full-term infant is capable of adaptation to extrauterine nutrition. This adaptation process includes coordinated sucking and swallowing, efficient gastric emptying and intestinal motility, regulation of digestive secretions and enzymes, efficient digestion and absorption, and excretion of waste products. The infant’s capacity to adapt to enteral nutrition depends on the gestational age at birth and the type of nutrients to which the GI tract is exposed.

Movement of nutrients through the GI tract occurs as a result of contraction of the intestinal smooth muscles. A combination of myogenic, neural, and neuroendocrine input during fasting and digestion regulates GI movement. By 26 weeks of gestation, uncoordinated contractions occur, but gastric emptying is slow. By 36 weeks of gestation, motility is similar to that of the full-term infant, and coordinated sucking and swallowing allow preterm infants to feed orally. Intestinal motility improves with gestational age, but it is not known whether the introduction of enteral feeding initiates coordinated motor activity. Meconium, a thick greenish black material consisting of epithelial cells, digestive tract secretions, and residue of swallowed amniotic fluid, is normally expelled from the intestine shortly after birth and provides evidence of patency of the GI tract.

At term the mechanical functions of digestion are relatively immature. Swallowing is an automatic reflex action for the first 3 months, and the infant has no voluntary control of swallowing until the striated muscles in the throat establish their cerebral connections. This begins at approximately 6 weeks of age. By 6 months the infant is capable of swallowing, holding food in the mouth, or spitting it out at will. The mechanism of sucking is also a reflexive activity in the newborn, and the muscular action of the tongue has a typical forward thrust. With neural and muscular development, the infant gradually acquires the ability to perform the coordinated muscular action typical of the adult type of swallowing. (See Chapter 12.) The eruption of the primary teeth facilitates chewing. The timing of dietary changes closely parallels these progressive developmental capabilities. First foods are those that require merely swallowing; these are followed by foods that need no mastication and finally those that require biting and chewing.

The stomach, which lies horizontally, is round until the child is approximately 2 years of age. It then gradually elongates until approximately 7 years of age, when it assumes the shape and anatomic position of the adult stomach. This anatomic placement of the stomach in infancy influences positioning practices during and after feeding. (See Chapter 8.) At birth the stomach capacity is small, but it increases rapidly with age.

The frequency and character of stools are affected by the rate of peristalsis and the nature of ingested food. The frequent, yellow stools of the neonate gradually assume a more adult regularity and character in the infant. When compared with the older child, the capacity of the infant’s stomach is smaller, but the emptying time is faster. Both the stomach capacity and the emptying time have implications for the amount and frequency of feedings during infancy.

The secretory cells of the GI tract are believed to be functional at birth. However, because most of the digestive enzymes depend on a specific pH, their efficiency may be impaired. The newborn produces only small amounts of saliva, which contain the starch-splitting enzyme amylase. Therefore its primary purpose at this time is to moisten the mouth and throat. By the end of the second year, the salivary glands have increased in size about five times to reach their full size and function.

Digestion

![]() Three processes—digestion, absorption, and metabolism—are necessary for the body to convert nutrients into forms it can use. Nutrients are composed of six major substances: carbohydrates, proteins, fats, vitamins, minerals, and water. Digestion is the initial preparation of food for use by the body. Two basic activities are involved: mechanical or muscular activity producing GI motility (movement) and chemical or enzymatic activity resulting from GI secretions.

Three processes—digestion, absorption, and metabolism—are necessary for the body to convert nutrients into forms it can use. Nutrients are composed of six major substances: carbohydrates, proteins, fats, vitamins, minerals, and water. Digestion is the initial preparation of food for use by the body. Two basic activities are involved: mechanical or muscular activity producing GI motility (movement) and chemical or enzymatic activity resulting from GI secretions.

![]() Animation—Passage of Food Through the Digestive Tract

Animation—Passage of Food Through the Digestive Tract

Mechanical digestion occurs through a series of neuromuscular actions that move and mix food along the GI tract at a rate suitable for digestion and absorption. Three types of muscles in the stomach and intestines contribute to this motility: (1) circular muscles churn and mix food particles; (2) longitudinal muscles propel the food mass; and (3) sphincter muscles (the lower esophageal, pyloric, ileocecal, and anal sphincters) control passage of the food mass to the next segment. The nervous system regulates these muscular actions. The intramural plexus forms the complex network of nerves within the GI wall that control smooth muscle contractions.

Chemical digestion involves five types of GI secretions: (1) enzymes (specific actions on degradation of nutrients), (2) hormones (stimulate or inhibit GI secretions), (3) hydrochloric acid (produces the pH necessary for the activity of specific enzymes), (4) mucus (lubricates and protects the GI tract), and (5) water and electrolytes (transport nutrients for digestion and absorption). Numerous cells and glands produce these secretions. The cells that secrete mucus and GI hormones are found primarily in the mucosa of the stomach and small intestine. The salivary glands and pancreas secrete enzymes, the gastric glands secrete enzymes and hydrochloric acid, and the liver secretes bile.

Mechanical and chemical digestion begins in the mouth. Biting and chewing mix food with saliva and reduce the food into a bolus. The saliva moistens the food to aid in swallowing. Salivary amylase begins the process of digestion of complex carbohydrates, or starches.

![]() The next phase of digestion is swallowing, or deglutition. Safe swallowing requires coordination of the oral and pharyngeal phases of swallowing to prevent food material from entering the airway. The coordination of swallowing is controlled by the interaction of the cranial nerves and the muscles of the mouth, pharynx, and esophagus. The oral phase of swallowing is voluntary. The pharyngeal phase is involuntary and consists of elevation of the palate, uvula, and larynx, followed by a peristaltic wave. The upper esophageal sphincter (UES) then relaxes to allow passage of the bolus into the esophagus. Peristalsis (wavelike movements that squeeze food along the entire length of the alimentary tract) moves the food through the esophagus, and the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) relaxes to allow the food to enter the stomach.

The next phase of digestion is swallowing, or deglutition. Safe swallowing requires coordination of the oral and pharyngeal phases of swallowing to prevent food material from entering the airway. The coordination of swallowing is controlled by the interaction of the cranial nerves and the muscles of the mouth, pharynx, and esophagus. The oral phase of swallowing is voluntary. The pharyngeal phase is involuntary and consists of elevation of the palate, uvula, and larynx, followed by a peristaltic wave. The upper esophageal sphincter (UES) then relaxes to allow passage of the bolus into the esophagus. Peristalsis (wavelike movements that squeeze food along the entire length of the alimentary tract) moves the food through the esophagus, and the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) relaxes to allow the food to enter the stomach.

Once a bolus of food has entered the stomach, the LES contracts to prevent food from refluxing (returning) into the esophagus. The stomach stores, mixes, and empties the food during digestion. The gastric glands secrete enzymes, hydrochloric acid, and mucus, which mix with the food to continue the process of digestion. The enzyme pepsin, formed from pepsinogen, begins the breakdown of whole proteins into polypeptides. Hydrochloric acid, secreted by the parietal cells, aids in the digestion of proteins. The hormone gastrin is released in the stomach in response to food. Gastrin stimulates the parietal cells to produce more hydrochloric acid. When the pH is very low, a feedback mechanism stops secretion of gastrin to prevent excessive acid formation. The mucus serves primarily to form a protective barrier between the acid and the gastric mucosa.

Partially digested food and watery secretions (chyme) are delivered to the small intestine. Up to this time, most of the digestion has been mechanical. The major part of chemical digestion, as well as several types of movement that aid in mechanical digestion, occurs in the small intestine. The small intestine secretes a large number of enzymes, each of which is specific for one of the fundamental types of nutrients. The mucosa of the small intestine secretes disaccharidases (maltase, lactase, and sucrase) that convert maltose, lactose, and sucrose to monosaccharides (glucose, fructose, and galactose). Aminopeptidase and dipeptidase convert polypeptides to smaller peptides and amino acids.

Secretions from the liver and pancreas complete the process of chemical digestion. The pancreas produces insulin (a hormone necessary for the metabolism of carbohydrates, fats, and proteins) and several enzymes that digest nutrients. Amylase converts starch to disaccharides. Trypsin and chymotrypsin convert proteins and polypeptides to smaller polypeptides. Lipase converts fats to glycerides and fatty acids. These pancreatic enzymes become active only after the inactive forms are secreted into the small intestine. For example, the enzyme enterokinase, secreted by the intestinal mucosal glands, is necessary for trypsinogen to be converted into trypsin. Otherwise, activated enzymes would digest the pancreas and pancreatic duct.

Another important aid in digestion and absorption in the small intestine is bile. Bile is produced in the liver and stored by the gallbladder. When fat enters the small intestine, the hormone cholecystokinin, which stimulates the gallbladder to release bile, is secreted by the intestinal mucosal glands. Bile, an emulsifying agent for fats that facilitates the digestion of fats by lipase, is necessary for the absorption of the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K. Absence of bile causes increased amounts of ingested fat to appear in the feces (steatorrhea), as well as a deficiency of these vitamins.

Absorption

After digestion of the food is complete, the simplified nutrient end products—monosaccharides (glucose, fructose, and galactose) from carbohydrates, fatty acids and glycerides from fats, and small peptides and amino acids from proteins—are ready for absorption. Vitamins and minerals are also released as a result of digestion. Water and electrolytes contribute to the fluid food mass that is finally absorbed.

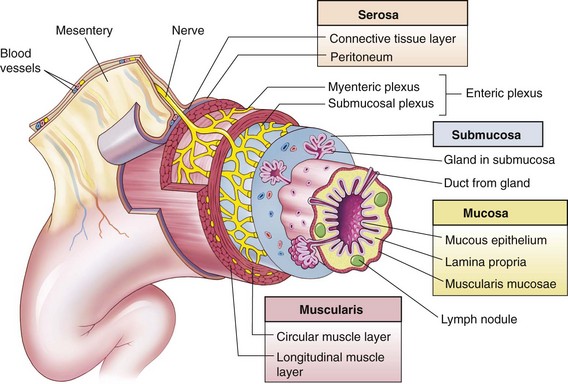

The principal site for absorption of nutrients in the GI tract is the small intestine. The wall of the GI tract consists of folds and projections that are progressively smaller (Fig. 33-1). These mucosal folds, villi, and microvilli increase the inner surface area approximately 600 times over the outer serosa, yielding an extremely large surface for absorption.

Pathophysiology Review

Fig. 33-1 Wall of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. The wall of the GI tract is made up of four layers with a network of nerves between the layers. Shown here is a generalized diagram of a segment of the GI tract. Note that the serosa is continuous with a fold of serous membrane called a mesentery. Note also that digestive glands may empty their products into the lumen of the GI tract by way of ducts. (From Patton KT, Thibodeau GA: Anatomy and physiology, ed 7, St Louis, 2010, Mosby.)

The mucosal folds are elevated folds along the mucosa. The villi can be seen by light microscope and are small, fingerlike projections covering the mucosal folds. The villi increase the surface area further. Each villus has a vascular supply, including venous and arterial capillaries and lacteals (lymphatic vessels in the small intestine that contain the substance chyle). The microvilli, numerous minute projections on the surface of each villus (visible by electron microscope), form the brush border.

The small intestine has several mechanisms of absorption, including passive diffusion, carrier-mediated diffusion, active energy-driven transport, and engulfment. Passive diffusion (osmosis) occurs across the epithelial membrane in the direction from higher concentration to lower concentration. Carrier-mediated diffusion occurs as molecules are carried across the epithelial cells of microvilli by a molecule that serves as a vehicle. Large molecules must be combined with a smaller molecule to pass from a greater pressure gradient to a lesser one. For example, vitamin B12 requires intrinsic factor to be carried into the intestinal circulation.

In active energy-driven transport, nutrients require energy to be absorbed and to cross the intestinal epithelial membrane. This mechanism is referred to as a pump. The pump transports molecules across the membrane by means of energy supplied by the cell’s metabolism. The sodium pump, which transports glucose, is an example of this mechanism.

Engulfment, or pinocytosis, is the process that allows large macromolecules to be absorbed by the epithelial cells of the villi. The epithelial cell engulfs the macromolecule and opens to allow the particle to enter the interior of the cell. The particle then enters the capillary blood. This mechanism transports some whole proteins and fat droplets.

After absorption by these mechanisms, the end products of carbohydrates and proteins are absorbed into the intestinal capillaries and enter the portal blood circulation of the liver, where further metabolic conversion occurs. The transfer of the end products of fat digestion is unique in that the fat molecules pass between the cells of the intestinal mucosa and into the lacteals of the villi. From there, they enter the larger lymph vessels and then the portal blood flow at the thoracic duct. Exceptions include the medium- and short-chain fatty acids, which can be absorbed directly into the blood circulation of the villi. Most of the fats commonly consumed are long-chain fatty acids, however, which are transported by way of the lacteals.

Fat-soluble vitamins are absorbed with digested fats in the presence of bile. Water-soluble vitamins, vitamin B complex, and vitamin C are absorbed in the small intestine. Absorption of vitamin B12 takes place only in the ileum. The majority of water and electrolyte absorption also takes place in the small intestine.

The large intestine completes the process of absorption and functions primarily to absorb sodium and additional water. The remainder of the products of digestion passes into the large intestine through the ileocecal valve. The muscular activity of the large intestine propels the mass forward. Most of the water and sodium is absorbed into the bloodstream in the proximal half of the colon. The colonic bacteria synthesize vitamin K, vitamin B12, and some of the vitamin B complex. Bacteria also affect the color and odor of the stool and gas formation. The odor is primarily caused by products of bacterial action and depends on the type of colonic flora and ingested food. (Defects in digestion or absorption notably alter the odor and appearance of feces.) Color is the result of bilirubin end products converted by bacteria to urobilinogen and then oxidized to urobilin (stercobilin). The feces that are excreted consist of undigested residue, water, bacteria, and mucus. Defecation occurs when the internal and external anal sphincters relax following distention of the rectum by feces.

Assessment of Gastrointestinal Function

The most common consequences of GI disease in children include malabsorption, fluid and electrolyte disturbances, malnutrition, and poor growth. (See Dehydration, Chapter 28, and Acute Diarrheal Disease, Chapter 29.) A thorough GI assessment includes history questions, general observations, clinical examination, and specific tests and procedures. The most important basic nursing assessments include measurement of intake and output, height and weight, abdominal examination, and simple stool and urine tests.

Numerous clinical manifestations provide clues to specific GI problems (Box 33-2). Some cases involve only one manifestation, whereas others may involve several signs and symptoms as part of the disease complex or syndrome.

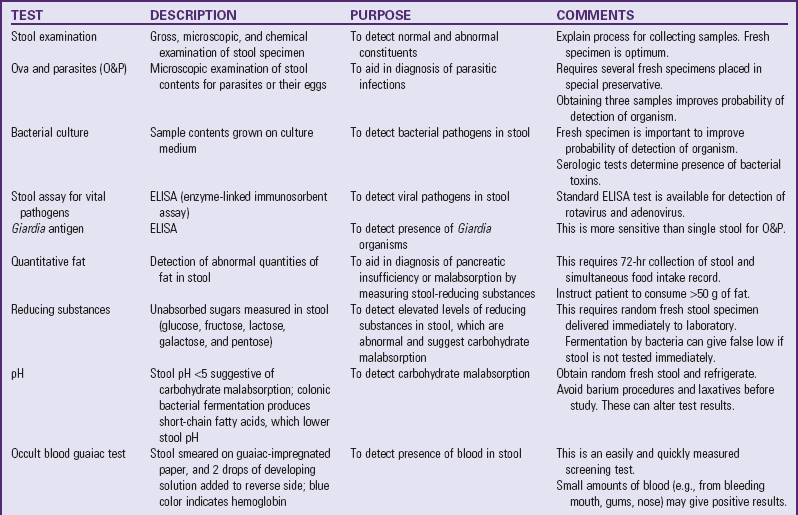

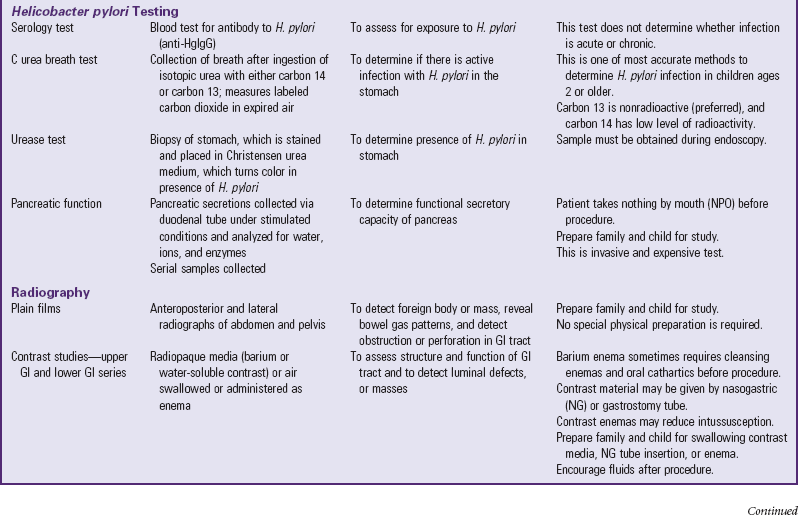

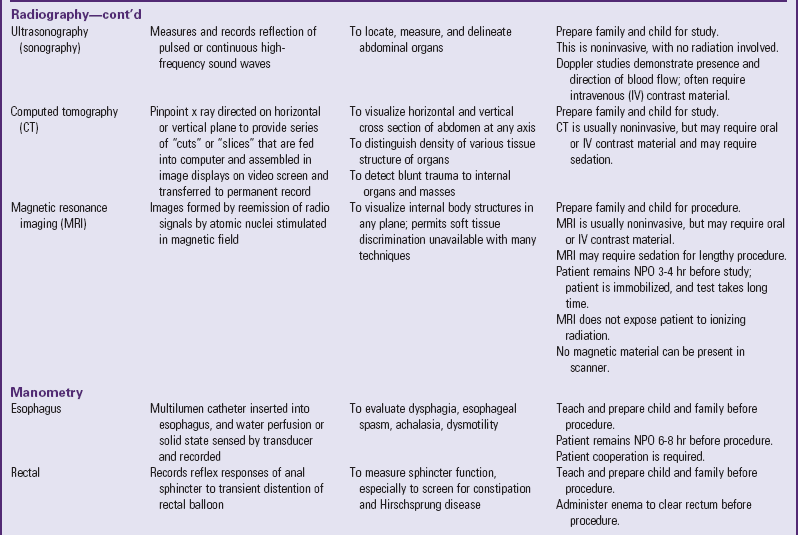

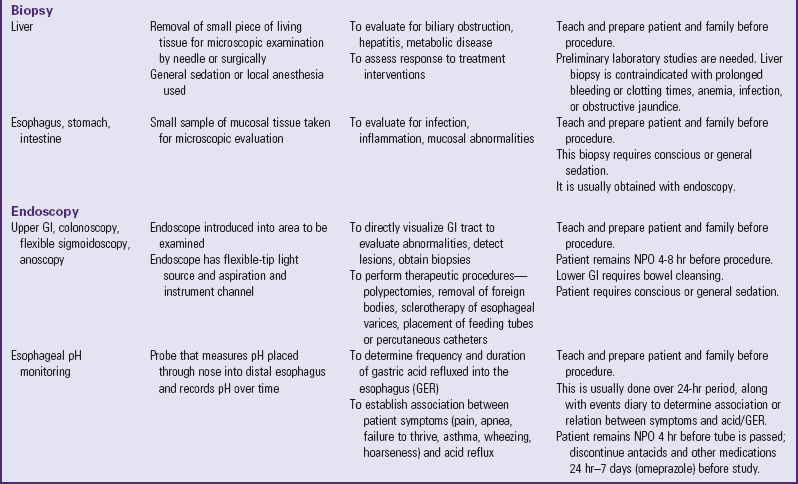

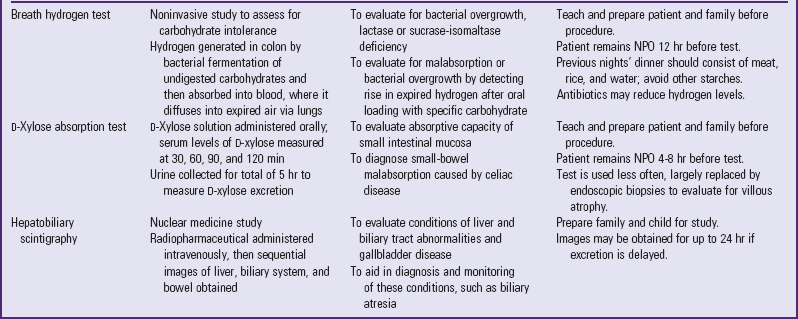

A number of tests assess GI function (Table 33-1). Nurses are often responsible for collecting specimens. (See Collection of Specimens, Chapter 27.) Because children may refuse to drink contrast media, generally dislike enemas, and are frightened by unfamiliar equipment, they need preparation for procedures and collection of specimens. (See Preparation for Diagnostic and Therapeutic Procedures, Chapter 27.)

Ingestion of Foreign Substances

![]() Children are prone to ingesting foreign substances because they frequently put their hands or other objects or substances in their mouth. Infants and small children in particular instinctively explore items with the mouth. Older children often place items in their mouth and accidentally swallow them. Rarely, a child deliberately swallows unusual objects or substances. Hands come into contact with dirt and contaminated objects that may contain lead, bacteria, or parasites. (See Chapter 16.)

Children are prone to ingesting foreign substances because they frequently put their hands or other objects or substances in their mouth. Infants and small children in particular instinctively explore items with the mouth. Older children often place items in their mouth and accidentally swallow them. Rarely, a child deliberately swallows unusual objects or substances. Hands come into contact with dirt and contaminated objects that may contain lead, bacteria, or parasites. (See Chapter 16.)

![]() Critical Thinking Exercise—Ingestion of a Foreign Body

Critical Thinking Exercise—Ingestion of a Foreign Body

Pica

Pica is an eating disorder characterized by the compulsive and excessive ingestion of both food and nonfood substances. Food picas include the excessive eating of ordinary foods or unprepared food substances, such as coffee grounds or uncooked cereals. Nonfood picas include the ingestion of substances such as clay, soil, stones, laundry starch, paint chips, ice, hair, paper, rubber, and feces. Pica is more common in children, women (especially during pregnancy), individuals who have autism or cognitive impairment, and those with anemia or chronic renal failure. In some cultures pica is an accepted practice based on the presumed nutritional or therapeutic properties or on religious or superstitious beliefs.

There are several theories on the cause of pica, including psychologic theories (compulsive neurosis) and nutritional theories (craving caused by a nutrient deficiency). Pica is clearly associated with both iron and zinc deficiencies, although controversy exists regarding whether pica is the cause or the result of the deficiency. Pica has also been reported as the presenting symptom in children with celiac disease thought to be caused by iron deficiency. Pica for dirt (geophagia) is the principal risk factor for visceral larva migrans (a common parasite in children and adults).

In some instances pica is relatively harmless. However, when the ingested substance contains a toxic ingredient (e.g., lead in paint), the consequences can be serious. Surgical complications, such as intestinal obstruction, perforation, inflammation, or hemorrhage, can result.

The nurse can detect pica by the history, physical examination, and radiologic studies. However, it is often unrecognized, and children may deny any unusual eating behaviors. The nurse should consider pica when children known to be at risk for this condition develop abdominal pain, other GI symptoms, or anemia. Children exhibiting signs of this disorder should be evaluated, and if a potentially harmful substance is involved, it should be removed from the child’s environment. Nursing education regarding the dangers of pica, especially lead, and assistance in helping families remove the substance are important. (See Chapter 16.)

Foreign Bodies

Foreign body ingestions are most common in infants and children between the ages of 6 months and 3 years, and are the leading cause of accidental death in children less than 6 years of age (Hollinger, 2007). Annually 300 children die in the United States from choking, and approximately 85% of these are younger than 3 years. The peak incidence is between the ages of 1 and 2 years. Boys are twice as likely as girls to aspirate, and children with neurologic problems are at greatest risk. Coins, peanuts, nuts, vegetables, metal or plastic objects, and bones are the most frequently aspirated items.

Where the foreign bodies are retained depends on the GI tract’s size, shape, diameter, and motility. Foreign bodies tend to become impacted at normally narrow sites of the GI tract. Pathologic narrowing of the intestine or intestinal stomas can also be a cause of foreign body obstruction. Foreign bodies in the stomach or intestine usually pass on their own. However, if they do become impacted, it generally occurs at the ileocecal valve, and sometimes at the pylorus, duodenum, or appendix. The most common anatomic sites in the esophagus are (1) the thoracic inlet (upper third of the esophagus), at the border of the cricopharyngeal muscle (UES); (2) the point where the esophagus crosses the aortic arch in the midesophagus; and (3) the LES (Gilger, 2003).

Signs and Symptoms

A history of choking followed by an acute episode of coughing is the most common presentation of foreign body ingestion (Lea, Nawaf, Yoav, et al, 2005). Initial signs and symptoms also may include dyspnea and wheezing. Aspirated foreign bodies that lodge in the larynx or trachea cause stridor. When these are in the large bronchi, crepitations and wheezes can be found. Wheezes and crepitations can be heard in both lungs, but unilateral findings have a higher specificity for foreign body aspiration (Kadmon, Stern, Bron-Harlev, et al, 2008).

Other symptoms may be those that are common with GI complaints in general (e.g., dysphagia, excessive drooling, poor feeding, vomiting, gagging, anorexia, neck or throat pain, sensation of a foreign object, and refusal to eat or drink).

Complications

Less than 1% of esophageal bodies cause a significant problem. However, serious problems that can occur include mediastinitis, pleural effusion, pneumothorax, and lung abscess. Foreign bodies are generally classified as sharp or dull, pointed or blunt, and toxic or nontoxic.

Food bolus foreign bodies should be immediately removed if the child is in severe distress and unable to swallow secretions. Disc batteries are a medical emergency if they are lodged in the esophagus because, if both poles of the battery come in contact with the flat wall of the esophagus, it may result in liquefaction, necrosis, and perforation. However, if the battery passes into the stomach, it will generally pass without incident. Sharp objects (straight pins, needles, straightened paper clips) need to be removed if lodged in the esophagus. If they pass into the stomach, they generally will pass out of the body, but there is a 35% risk of complications.

Diagnostic Evaluation

As mentioned, there may be no signs or symptoms, but some children come to the physician for evaluation because of problems. The nurse should perform a complete history and physical examination. Assess the airway and breathing first. Findings on the chest evaluation might include inspiratory stridor or expiratory wheezing. Findings on an abdominal examination could be small bowel obstruction or perforation. The physical examination might demonstrate swelling, erythema, or crepitus suggestive of esophageal perforation.

Assessment often involves radiologic evaluation. A plain x-ray film of the neck, chest, and abdomen may be ordered. Biplane radiographic studies identify radiopaque esophageal foreign bodies. Flat objects such as coins may be visible in the coronal plane. Objects in the trachea generally orient into the sagittal plane and are easiest to see in the lateral projection. Hand-held metal detectors have been used to detect coins. Endoscopy should be done in patients with symptoms suggestive of obstruction even if the radiographic evidence is negative.

Therapeutic Management

Intervention is urgent when a child has sharp objects, magnets, or disc batteries lodged in the esophagus because of the risk of perforation or acid burns (Kiger, Brenkert, and Losek, 2008). Urgent intervention is also important any time the airway is compromised. If the child is asymptomatic and the foreign body does not carry an emergent risk, it is reasonable to wait 24 hours to see if it will pass. Foreign objects should not be allowed to remain in the esophagus for more than 24 hours because of the potential for complications such as erosion, perforation, or formation of fistulas.

Flexible endoscopy allows direct visualization of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum. It is the best approach for removing a foreign object. It involves passing a narrow tube with a camera on the end through the mouth into the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum with the patient under sedation. The foreign object can be detected and removed. Rigid endoscopy is used to remove impacted sharp objects at the level of the hypopharynx and cricopharyngeal muscle.

Another technique that has been used is bougienage (Uyemura, 2005). This involves passing a dilator to push objects into the stomach. The drawback is this method does not allow inspection of the esophagus to assess for injury or damage, and it increases the risk of perforation of the esophagus.

Another method involves passing a Foley catheter into the esophagus, inflating it distal to the obstruction, and then withdrawing it (Uyemura, 2005). Again there is a risk of airway obstruction and an inability to directly visualize the esophagus.

Coins have been removed using the penny pincher technique, which involves passing grasping forceps through a nasogastric (NG) tube using fluoroscopic guidance. This is an improvement over the Foley technique because it allows for direct control of the object, but again it does not permit inspection of the esophagus.

Important variables in the application of treatment guidelines include the type of foreign object, its location in the GI tract, and whether the patient is symptomatic. Of all foreign bodies that reach the stomach, 80% to 90% pass spontaneously, 10% to 20% require endoscopic removal, and 1% requires surgery (Byrne, 1999). The progress of a foreign body may be followed radiographically. Examine all stools to detect the passage of the object. The child should be fed the usual diet. Sharp objects such as long pins or chicken or fish bones should be removed endoscopically rather than risk perforation by allowing them to pass spontaneously (Byrne, 1999). Endoscopic or surgical intervention should be implemented if the object fails to progress through the GI tract (Uyemura, 2005).

Nursing Care Management

The primary nursing intervention is prevention of foreign body ingestion through family teaching. All children who are old enough to understand are taught not to put anything in their mouth except food. Infants and young children who cannot follow such advice must have their environment protected.

Prevention includes supervision and ongoing education as the child matures. Any small items, diaper pins, or sharp objects are placed out of the area where an infant is usually cared for, plays, or sleeps. As the infant becomes more mobile, the environment is inspected carefully for hazardous objects. Any potentially dangerous items are placed out of reach of a young child or discarded where they cannot be retrieved easily. Toys are carefully examined for small or removable parts that could be accidentally ingested. If infants and small children wear earrings, the earrings should have screw backs to prevent them from falling off. Infants and small children who wear other jewelry should be carefully supervised. Infants or young children should not be allowed to play with marbles, coins, or objects with small batteries.

Once an object is swallowed, parents need guidelines on seeking treatment (see Emergency Treatment box). When no treatment is advised and the object is left to pass spontaneously, parents should examine all stools for verification that the object has passed safely through the GI tract, usually within 3 or 4 days. For children in diapers, this is easily accomplished by squeezing the stool between the diaper to locate the object. For toilet-trained children a piece of plastic wrap placed across the toilet bowl to collect the stool makes it easier to examine the feces. A tongue blade or similar disposable object may be needed to break up the stool for inspection.

Disorders of Motility

![]() Constipation is a symptom, not a disease. It is defined as a decrease in bowel movement frequency or trouble defecating for more than 2 weeks (Philichi, 2008). Constipation is an alteration in the frequency, consistency, or ease of passing stool. Parents often define constipation as passing less than three stools per week. It may also be defined as painful bowel movements, which are often blood streaked or include the retention of stool, with or without soiling, even with a stool frequency of more than three stools per week (Loening-Baucke and Pashankar, 2006). The frequency of bowel movements, however, is not considered a diagnostic criterion because it varies widely among children. Having extremely long intervals between defecation is obstipation. Constipation with fecal soiling is encopresis.

Constipation is a symptom, not a disease. It is defined as a decrease in bowel movement frequency or trouble defecating for more than 2 weeks (Philichi, 2008). Constipation is an alteration in the frequency, consistency, or ease of passing stool. Parents often define constipation as passing less than three stools per week. It may also be defined as painful bowel movements, which are often blood streaked or include the retention of stool, with or without soiling, even with a stool frequency of more than three stools per week (Loening-Baucke and Pashankar, 2006). The frequency of bowel movements, however, is not considered a diagnostic criterion because it varies widely among children. Having extremely long intervals between defecation is obstipation. Constipation with fecal soiling is encopresis.

![]() Critical Thinking Exercise—Constipation

Critical Thinking Exercise—Constipation

Constipation may arise secondary to a variety of organic disorders or in association with a wide range of systemic disorders. Structural disorders of the intestine, such as strictures, ectopic anus, and Hirschsprung disease (HD), may be associated with constipation. Systemic disorders associated with constipation include hypothyroidism, hypercalcemia resulting from hyperparathyroidism or vitamin D excess, and chronic lead poisoning. Constipation is also associated with drugs such as antacids, diuretics, antiepileptics, antihistamines, opioids, and iron supplementation. Spinal cord lesions may be associated with loss of rectal tone and sensation. Affected children are prone to chronic fecal retention and overflow incontinence.

The majority of children have idiopathic or functional constipation, since no underlying cause can be identified. Chronic constipation may occur as a result of environmental or psychosocial factors, or a combination of both. Transient illness, withholding and avoidance secondary to painful or negative experiences with stooling, and dietary intake with decreased fluid and fiber all play a role in the etiology of constipation.

Infancy

The onset of constipation frequently occurs during infancy and may result from organic causes such as HD, hypothyroidism, and strictures. It is important to differentiate these conditions from functional constipation. Constipation in infancy is often related to dietary practices. It is less common in breast-fed infants, who have softer stools than bottle-fed infants. Breast-fed infants may also have decreased stools because of more complete use of breast milk with little residue. When constipation occurs with a change from human milk or modified cow’s milk to whole cow’s milk, simple measures such as adding or increasing the amount of cereal, vegetables, and fruit in the infant’s diet usually correct the problem. When a bottle-fed infant passes a hard stool that results in an anal fissure, stool-withholding behaviors may develop in response to pain on defecation (see Critical Thinking Exercise).

Childhood

Most constipation in early childhood is due to environmental changes or normal development when a child begins to attain control over bodily functions. A child who has experienced discomfort during bowel movements may deliberately try to withhold stool. Over time, the rectum accommodates to the accumulation of stool, and the urge to defecate passes. When the bowel contents are ultimately evacuated, the accumulated feces are passed with pain, thus reinforcing the desire to withhold stool.

Constipation in school-age children may represent an ongoing problem or a first-time event. The onset of constipation at this age is often the result of environmental changes, stresses, and changes in toileting patterns. A common cause of new-onset constipation at school entry is fear of using the school bathrooms, which are noted for their lack of privacy. Early and hurried departure for school immediately after breakfast may also impede bathroom use.

Therapeutic Management

Treatment of constipation depends on the cause and duration of symptoms. A complete history and physical examination are essential to determine appropriate management (Tobias, Mason, Lutkenhoff, et al, 2008). Meconium plugs are often evacuated after digital examination. It may be necessary to facilitate passage of the obstruction by irrigation with a hypertonic solution or water-soluble enema such as diatrizoate meglumine (Gastrografin) or diatrizoate sodium (Hypaque). If the constipation is due to HD, surgical treatment may include resection of the intestine and saline irrigations.

Management of the infant should include education of the parents concerning normal bowel habits. Short, transient periods of constipation usually require no intervention. Mild constipation usually resolves as solid food is introduced in the diet. Stool softeners such as malt extract or lactulose may be used for hard stools or anal fissures. The persistent use of rectal stimulation with thermometers or cotton-tipped applicators is discouraged because these methods often result in anal fissures and increased pain that may trigger stool withholding.

The management of simple constipation consists of a plan to promote regular bowel movements. Often this is as simple as changing the diet to provide more fiber and fluids, eliminating foods known to be constipating, and establishing a bowel routine that allows for regular passage of stool. Stool-softening agents such as docusate or lactulose may also be helpful. Polyethylene glycol (PEG) 3350 without electrolytes (MiraLax) is a chemically inert polymer that has been introduced as a new laxative in recent years. Children tolerate it well because it can be mixed in a beverage of choice (Loening-Baucke and Pashankar, 2006). If other symptoms such as vomiting, abdominal distention, or pain and evidence of growth failure are associated with the constipation, investigate the condition further.

Management of chronic constipation requires an organized approach. It is important for families to realize that it usually requires at least 6 to 12 months of treatment to be effective (Tobias, Mason, Lutkenhoff, et al, 2008). The goals for management include restoring regular evacuation of stool, shrinking the distended rectum to its normal size, and promoting a regular toileting routine. This requires a combination of therapies and should include bowel cleansing, maintenance therapy to prevent stool retention, modification of diet, bowel habit training, and behavioral modification (Box 33-3).

After the impaction is removed, maintenance therapy often lasting for 6 to 12 months is necessary to promote easy passage of stool and to prevent stool retention. Maintenance therapy includes mineral oil, stool softeners, and laxatives. Stool softeners are often ineffective for severe constipation; laxative therapy may be necessary to return the rectum to its normal size. Polyethylene glycol is a more favorable constipation intervention than lactulose (Dupont, Leluyer, Maamri, et al, 2005). Polyethylene glycol increases fluid in the colon. The additional volume of fluid stimulates the urge to defecate.

Changes in the diet may be helpful but are usually not effective alone. A recent study comparing a liquid yogurt fiber mixture to lactulose in 147 children revealed comparable results in the treatment of constipation (Kokke, Scholtens, Alles, et al, 2008). Encouraging the intake of fiber ultimately helps maintain regular elimination once the rectum returns to normal size and the laxatives are tapered. Effective counseling is an essential element of the treatment plan for children with chronic constipation. Explain normal bowel function, the purpose of interventions, and the need for persistence to the child and family.

Retraining therapy involves habit training, reinforcement for sitting on the toilet and defecating, and emotional support. Parents should establish a regular toilet time once or twice a day, preferably after a meal. A reasonable amount of time (5 to 10 minutes) should be spent attempting to defecate completely. Biofeedback may be indicated as a form of behavior modification and as a means to teach children to relax the anal sphincter during defecation.

Nursing Care Management

Unfortunately, constipation tends to be self-perpetuating. A child who has difficulty or discomfort when attempting to evacuate the bowels has a tendency to retain the bowel contents, and thus constipation becomes a chronic problem. Nursing assessment begins with a history of bowel habits; diet; events that may be associated with the onset of constipation; drugs or other substances that the child may be taking; and the consistency, color, frequency, and other characteristics of the stool. If there is no evidence of a pathologic condition that requires further investigation, the nurse’s major task is to educate the parents regarding normal stool patterns and to participate in the education and treatment of the child.

Dietary modifications are helpful in preventing constipation. Fiber is an important part of the diet. Parents benefit from guidance about foods high in fiber (Box 33-4) and ways to promote healthy food choices in children. If bran is added to the diet, creative ways to disguise the consistency, such as adding it to cereal, peanut butter, mashed potatoes, fruit shakes, and baked goods, are helpful. Beans are often found in Mexican dishes children enjoy and can be added to soups, salads, and stews. Beyond the age when foreign body aspiration is a hazard, a good source of fiber is corn and popcorn.

Parents need reassurance concerning the prognosis for establishing normal bowel habits. Many parents are concerned about constipation and view the condition as dangerous. Families need thorough instructions about the treatment plan. If the child needs enemas or medication, give the family the appropriate instructions. It is important to discuss attitudes and expectations regarding toilet habits and the treatment plan.

Hirschsprung Disease (Congenital Aganglionic Megacolon)

HD is a congenital anomaly that results in mechanical obstruction from inadequate motility of part of the intestine. It accounts for about one fourth of all cases of neonatal intestinal obstruction. The incidence is 1 in 5000 live births. It is four times more common in males than in females and follows a familial pattern in a small number of cases. Mutations in the RET protooncogene have been found in 17% to 38% of children with short-segment HD and in 70% to 80% of those with long-segment involvement (Dasgupta and Langer, 2004). In more than 80% of cases the aganglionosis is restricted to the internal sphincter, rectum, and a few centimeters of the sigmoid colon and is termed short-segment disease (Theocharatos and Kenny, 2008).

Pathophysiology

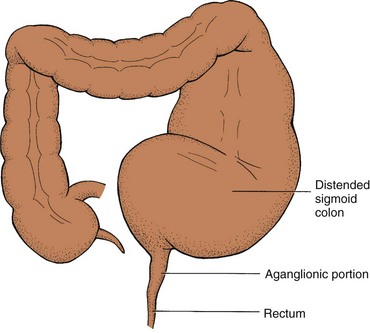

The pathology of HD relates to the absence of ganglion cells in the affected areas of the intestine, resulting in a loss of the rectosphincteric reflex and an abnormal microenvironment of the cells of the affected intestine (Theocharatos and Kenny, 2008). The term congenital aganglionic megacolon describes the primary defect, which is the absence of ganglion cells in the myenteric plexus of Auerbach and the submucosal plexus of Meissner (Fig. 33-2).

The absence of ganglion cells in the affected bowel results in a lack of enteric nervous system stimulation, which decreases the internal sphincter’s ability to relax. Unopposed sympathetic stimulation of the intestine results in increased intestinal tone. In addition to the contraction of the abnormal bowel and the resulting lack of peristalsis, there is a loss of the rectosphincteric reflex. Normally when a stool bolus enters the rectum, the internal sphincter relaxes and the stool is evacuated. In HD, the internal sphincter does not relax. In most cases the aganglionic segment includes the rectum and some portion of the distal colon. However, the entire colon or part of the small intestine may be involved. Occasionally, skip segments or total intestinal aganglionosis may occur.

Clinical Manifestations

Most children with HD are diagnosed in the first few months of life. Clinical manifestations vary according to the age when symptoms are recognized and the presence of complications, such as enterocolitis (Box 33-5). A neonate usually is seen with distended abdomen, feeding intolerance with bilious vomiting, and delay in the passage of meconium. Typically, 95% of normal term infants pass meconium in the first 24 hours of life, whereas less than 10% of infants with HD do so. In older children, a careful history is helpful.

Diagnostic Evaluation

In the neonate the diagnosis is suspected on the basis of clinical signs of intestinal obstruction or failure to pass meconium. In infants and children the history is an important part of diagnosis and typically includes a chronic pattern of constipation. On examination the rectum is empty of feces, the internal sphincter is tight, and leakage of liquid stool and accumulated gas may occur if the aganglionic segment is short. A barium enema often demonstrates the transition zone between the dilated proximal colon (megacolon) and the aganglionic distal segment. However, this typical megacolon and narrow distal segment may not develop until the age of 2 months or later.

To confirm the diagnosis, rectal biopsy is performed either surgically to obtain a full-thickness biopsy specimen or by suction biopsy for histologic evidence of the absence of ganglion cells. A noninvasive procedure that may be used is anorectal manometry, in which a catheter with a balloon attached is inserted into the rectum. The test records the reflex pressure response of the internal anal sphincter to distention of the balloon. A normal response is relaxation of the internal sphincter followed by a contraction of the external sphincter. In HD the external sphincter contracts normally but the internal sphincter fails to relax.

Therapeutic Management

The majority of children with HD require surgery rather than medical therapy with frequent enemas (Levitt, Martin, Olesevich, et al, 2009). Once the child is stabilized with fluid and electrolyte replacement, if needed, surgery is performed, with a high rate of success. Surgical management consists primarily of the removal of the aganglionic portion of the bowel to relieve obstruction, restore normal motility, and preserve the function of the external anal sphincter. The transanal Soave endorectal pull-through procedure is often performed and consists of pulling the end of the normal bowel through the muscular sleeve of the rectum, from which the aganglionic mucosa has been removed (Huang, Zheng, and Xiao, 2008). With earlier diagnosis the proximal bowel may not be extremely distended, thus allowing for a primary pull-through or one-stage procedure and eliminating the need for a temporary colostomy. Simpler operations, such as an anorectal myomectomy, may be indicated in very short–segment disease.

After the pull-through procedure, anal stricture and incontinence may occur and require further therapy, including dilations or bowel retraining therapy. Constipation and fecal incontinence are chronic problems in a significant proportion of patients after surgical correction for HD (Levitt, Martin, Olesevich, et al, 2009). As these children grow older, this can significantly affect their quality of life (Mills, Konkin, Milner, et al, 2008).

Nursing Care Management

The nursing concerns depend on the child’s age and the type of treatment. If the disorder is diagnosed during the neonatal period, the main objectives are (1) to help the parents adjust to a congenital defect in their child, (2) to foster infant-parent bonding, (3) to prepare them for the medical-surgical intervention, and (4) to assist them in colostomy care after discharge.

Preoperative Care: The child’s preoperative care depends on the age and clinical condition. A child who is malnourished may not be able to withstand surgery until his or her physical status improves. Often this involves symptomatic treatment with enemas; a low-fiber, high-calorie, and high-protein diet; and in severe situations the use of total parenteral nutrition (TPN).

Physical preoperative preparation includes the same measures that are common to any surgery. (See Surgical Procedures, Chapter 27.) In the newborn, whose bowel is sterile, no additional preparation is necessary. However, in other children, preparation for the pull-through procedure involves emptying the bowel with repeated saline enemas and decreasing bacterial flora with oral or systemic antibiotics and colonic irrigations using antibiotic solution. Enterocolitis is the most serious complication of HD. Emergency preoperative care includes frequent monitoring of vital signs and blood pressure for signs of shock; monitoring fluid and electrolyte replacements, as well as plasma or other blood derivatives; and observing for symptoms of bowel perforation, such as fever, increasing abdominal distention, vomiting, increased tenderness, irritability, dyspnea, and cyanosis.

Because progressive distention of the abdomen is a serious sign, the nurse measures abdominal circumference with a paper tape measure, usually at the level of the umbilicus or at the widest part of the abdomen. The nurse marks the point of measurement with a pen to ensure reliability of subsequent measurements. Abdominal measurement can be obtained with the vital sign measurements and is recorded in serial order so that any change is obvious (see Atraumatic Care box).

The child’s age dictates the type and extent of psychologic preparation. Because a colostomy is usually performed, the child who is of preschool age is told about the procedure in concrete terms with the use of visual aids. (See Chapter 27.) It is important to time explanations appropriately to prevent the anxiety and confusion that could result from too much information. It is also important to stress to parents and older children that the colostomy for HD is temporary, unless so much bowel is involved that a permanent ileostomy must be performed. In most instances the extent of bowel resection is known before surgery, although the nurse should be aware of cases when doubt exists concerning repair. Remember that although a temporary colostomy is favorable in terms of future health and adjustment, it requires additional surgery, which may be stressful to parents and children.

Postoperative Care: Postoperative care is the same as that for any child or infant with abdominal surgery. (See Surgical Procedures, Chapter 27.) When a colostomy is part of the corrective procedure, stomal care is a major nursing task. (See Ostomies, Chapter 27.) To prevent contamination of an infant’s abdominal wound with urine, pin the diaper below the dressing. Sometimes a Foley catheter is used in the immediate postoperative period to divert the flow of urine away from the abdomen.

Discharge Care: After surgery, parents need instruction concerning colostomy care. Even a preschooler can be included in the care by handing articles to the parent, rolling up the colostomy pouch after it is emptied, or applying barrier preparations to the surrounding skin. Although the diagnosis of HD is less frequent in school-age children or adolescents, children this age can often be involved in colostomy care to the point of total responsibility.

Some institutions and communities have enterostomal therapists who provide expert assistance in planning home care. If families require financial assistance and psychologic support, referral to a social worker, home health care agency, or community health nurse provides continuity of care.

Gastroesophageal Reflux

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is defined as the transfer of gastric contents into the esophagus. This phenomenon is physiologic, occurring throughout the day, most frequently after meals and at night; therefore it is important to differentiate GER from gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). GERD represents symptoms or tissue damage that result from GER. Approximately 50% of infants less than 2 months old are reported to have GER (Suwandhi, Ton, and Schwarz, 2006). This “physiologic” GER usually resolves spontaneously by 1 year of age. GER becomes a disease when complications such as failure to thrive, bleeding, or dysphagia develop.

Certain conditions predispose children to a high prevalence of GERD, including neurologic impairment, hiatal hernia, repaired esophageal atresia, and morbid obesity (Suwandhi, Ton, and Schwarz, 2006). Sandifer syndrome is an uncommon condition, usually occurring in young children, characterized by repetitive stretching and arching of the head and neck that can be mistaken for a seizure. This maneuver likely represents a physiologic neuromuscular response attempting to prevent acid refluxate from reaching the upper portion of the esophagus (Cavataio and Guandalini, 2005).

Infants who are prone to develop GER include premature infants and infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Children who have had tracheoesophageal or esophageal atresia repairs, neurologic disorders, scoliosis, asthma, cystic fibrosis, or cerebral palsy are also prone to develop GER.

Clinical Manifestations

During infancy the most common clinical manifestation of GER is passive regurgitation or emesis. Recurrent vomiting occurs in 50% of infants in the first 3 months of life, 67% of 4-month-olds, and 5% of 10- to 12-month-old infants (Rudolph, Mazur, Liptak, et al, 2001). Vomiting generally resolves spontaneously in most of these infants. Clinical manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux are listed in Box 33-6. GER is one of the causes of apparent life-threatening events and has also been associated with chronic respiratory disorders, including reactive airways disease, recurrent stridor, chronic cough, and recurrent pneumonia in infants. Esophagitis can also cause discomfort in the chest area, which may be manifested as unusual irritability or poor intake of nutrients. Poor weight gain and poor growth may occur in a child with an insufficient intake of nutrients or with a large amount of regurgitation.

For preschool children GER may occur with intermittent vomiting. Older children tend to initially come to the physician with a more adultlike pattern of heartburn, regurgitation, and reswallowing. GERD may cause severe inflammation, chronic blood loss with anemia and hematemesis, hypoproteinemia, or melena. If the inflammation goes untreated, scarring and strictures may form. Barrett mucosa, another potential finding in the presence of chronic inflammation, is characterized by changes in the distal esophageal mucosa with metaplastic potentially malignant epithelium.

GER is common in children with asthma, but recurrent pneumonia caused by GER is uncommon except in children with neurologic impairments. Hoarseness has also been associated with GER in children.

Diagnostic Evaluation

The history and physical examination are usually sufficiently reliable to establish the diagnosis of GER. However, the upper GI series is helpful in evaluating the presence of anatomic abnormalities (e.g., pyloric stenosis, malrotation, annular pancreas, hiatal hernia, esophageal stricture). The 24-hour intraesophageal pH monitoring study is the gold standard in the diagnosis of GER (Suwandhi, Ton, and Schwarz, 2006). Endoscopy with biopsy may be helpful to assess the presence and severity of esophagitis, strictures, and Barrett esophagus and to exclude other disorders such as Crohn disease (CD). Scintigraphy detects radioactive substances in the esophagus after a feeding of the compound and assesses gastric emptying. It can differentiate between aspiration of gastric contents from reflux and aspiration from poor oropharyngeal muscle coordination.

Therapeutic Management

Therapeutic management of GER depends on its severity. No therapy is needed for the infant who is thriving and has no respiratory complications. Avoidance of certain foods that exacerbate acid reflux (e.g., caffeine, citrus, tomatoes, alcohol, peppermint, spicy or fried foods) can improve mild GER symptoms. Lifestyle modifications in children (e.g., weight control if indicated; small, more frequent meals) and feeding maneuvers in infants (e.g., thickened feedings, upright positioning) can help as well. Twenty research trials involving 771 children found thickened feeds reduced the regurgitation severity (Craig, Hanlon-Dearman, Sinclair, et al, 2004). Thickened feeding has a significant effect on the reduction of regurgitation frequency and amount in otherwise healthy infants. However, the occurrence of acid GER was not reduced (Wenzi, Schneider, Scheele, et al, 2003).

Feedings thickened with 1 tsp to 1 tbsp of rice cereal per ounce of formula may be recommended. This may benefit infants who are underweight as a result of GERD. Constant NG feedings may be necessary for the infant with severe reflux and failure to thrive until surgery can be performed. Elevating the head of the bed did not have any effect on GER symptoms in the Cochrane systematic review of 20 research trials (Craig, Hanlon-Dearman, Sinclair, et al, 2004). Prone positioning of infants also decreases episodes of GER but is recommended only with extreme caution when the risk of GERD complications exceeds the risk of sudden infant death syndrome (Cavataio and Guandalini, 2005). The American Academy of Pediatrics continues to recommend supine positioning for sleep. (See Chapter 11.)

Pharmacologic therapy may be used to treat infants and children with GERD. Both H2-receptor antagonists (cimetidine [Tagamet], ranitidine [Zantac], or famotidine [Pepcid]) and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs; esomeprazole [Nexium], lansoprazole [Prevacid], omeprazole [Prilosec], pantoprazole [Protonix], and rabeprazole [Aciphex]) reduce gastric hydrochloric acid secretion and may stimulate some increase in LES tone. Use of available prokinetic drugs (e.g., bethanechol [Urecholine] and metoclopramide) remains controversial. Careful analyses of published data have failed to demonstrate clinical efficacy in modifying the natural history or therapeutic outcomes of GER in childhood (Suwandhi, Ton, and Schwarz, 2006).

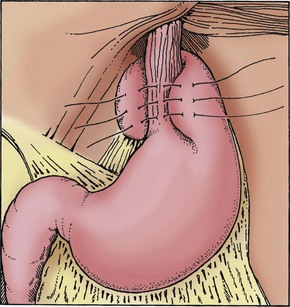

Surgical management of GER is reserved for children with severe complications such as recurrent aspiration pneumonia, apnea, severe esophagitis, or failure to thrive, and for children who have failed to respond to medical therapy. The Nissen fundoplication (Fig. 33-3) is the most common surgical procedure (Christian and Buyske, 2005). This surgery involves passage of the gastric fundus behind the esophagus to encircle the distal esophagus. Complications following fundoplication include breakdown of the wrap, small bowel obstruction, gas-bloat syndrome, infection, retching, and dumping syndrome (Rudolph, Mazur, Liptak, et al, 2001).

Fig. 33-3 Nissen fundoplication sutures passing through esophageal musculature. (Redrawn from Campbell A, Ferrara B: Toupet partial fundoplication, AORN J 57:671-679, 1993.)

Prognosis: The majority of infants with GER have a mild problem that generally improves by 12 to 18 months of age and requires only conservative lifestyle changes or medical therapy. If GER is severe and remains unsuccessfully treated, multiple complications can occur. Esophageal strictures caused by persistent esophagitis with scarring are one of the most significant complications. Recurrent respiratory distress with aspiration pneumonia, another serious complication, is an indication for surgery. Failure to thrive caused by GER can often be managed with medical therapy and nutritional support.

Nursing Care Management

Nursing care is directed at (1) identifying children with symptoms suggestive of GER; (2) educating parents regarding home care, including feeding, positioning, and medications when indicated; and (3) caring for the child undergoing surgical intervention. For the majority of infants, parental reassurance of the benign nature of the condition and its relationship to physiologic maturity is the most important intervention. To help parents cope with the inconvenience of dealing with a child who spits up or regurgitates frequently, simple tips such as using bibs and protective clothes during feeding and prone positioning when holding the infant after feeding are beneficial.

It is important to educate and reassure parents about positioning. In the past, recommendations encouraged upright positioning during sleeping for both infants and older children. The supine position for sleeping continues to be recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics (2005). Parents should not place infants on their sides as an alternative to fully supine sleeping, and avoidance of soft bedding and soft objects in the bed is important. Rescheduling of the family’s routine may be required to accommodate more frequent feeding times. If parents thicken formula with cereal, they should also enlarge the nipple opening for easier sucking. Usually breast-feeding may continue, and the mother may provide more frequent feeding times or express the milk for thickening with rice cereal. Parents should avoid feeding the child spicy foods or any foods that they find aggravate symptoms in general, and avoid caffeine, chocolate, tobacco smoke, and alcohol when breast-feeding. Other practical advice includes advising the parents to avoid vigorous play after feedings and to avoid feeding just before bedtime.

When regurgitation is severe and growth is a problem, continuous NG tube feedings may decrease the amount of emesis and provide constant buffering of gastric acid. Special preparation of caregivers is required when this type of nutritional therapy is indicated.

The nurse can support the family by providing information about all aspects of treatment. Parents often require specific information about the medications given for GER. PPIs are most effective when administered 30 minutes before breakfast so that the peak plasma concentrations occur with mealtime. If they are given twice a day, the second best time for administration is 30 minutes before the evening meal. Parents need to be reassured because it takes several days of administration to achieve a steady state of acid suppression. They may not see the results that they expect right away. A number of new formulations available in PPIs allow for more efficient administration. Some preparations are available in dissolvable pills. There are powder and granule preparations as well. Many pharmacies will compound the medication in a liquid form for administration.

Postoperative nursing care after the Nissen fundoplication is similar to that for other types of abdominal surgery. (See Chapter 27.) Gastric decompression by an NG tube or gastrostomy must be maintained to avoid distention in the immediate postoperative period. Usually the NG tube should not be replaced by the nurse if it is accidentally removed because of the risk of injury to the operative site. When postoperative ileus resolves, the NG tube is removed or the gastrostomy tube is elevated in preparation for feeding. If bolus feedings are initiated through the gastrostomy, the tube may need to remain vented for several days or longer to avoid gastric distention from swallowed air. Edema surrounding the surgical site and a tight gastric wrap may prohibit the infant from expelling air through the esophagus. Some infants benefit from clamping of the tube for increasingly longer intervals until they are able to tolerate continuous clamping between feedings. During this time, if the infant displays increasing irritability and evidence of cramping, some relief may be provided by venting the tube.

Preparation for Home Care: If medical management is prescribed or surgery is performed, nursing responsibilities include educating caregivers about administering drugs at home, special feeding regimens or formula preparation, gastrostomy care, and postoperative care. (See Chapter 27.) After surgery, reflux is completely controlled in most cases, with these children attaining normal health and growth. If a gastrostomy tube is inserted during surgery, it may be removed after several months unless nutritional supplementation is needed. In severe cases of bloating or dumping syndrome, continuous tube feedings may be better tolerated. Caregivers should be aware of potential postoperative problems, such as difficulty vomiting, bloating symptoms, or discomfort with large solid-food meals, and seek guidance from their health care provider as needed.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is one of the most common adult problems treated by gastroenterologists. Recently IBS has been identified as a cause of recurrent abdominal pain in 4% to 25% of school-age children (Huertas-Ceballos, Logan, Bennett, et al, 2009). (See Recurrent Abdominal Pain, Chapter 18.) IBS is classified as a functional GI disorder. As with other forms of recurrent abdominal pain, the symptoms should be present either recurrently or constantly over a 3-month period (Huertas-Ceballos, Logan, Bennett, et al, 2009). Children with IBS often have alternating diarrhea and constipation, flatulence, bloating or a feeling of abdominal distention, lower abdominal pain, a feeling of urgency when needing to defecate, and a feeling of incomplete evacuation of the bowel. IBS also has psychosocial effects.

The cause of IBS is not clear, but it is believed to involve a combination of motor, autonomic, and psychologic factors. Children with IBS are evaluated to rule out organic causes for their symptoms such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), lactose intolerance, and parasitic infections. Many children with symptoms appear active and healthy and have normal growth.

Therapeutic Management

The long-range goal of treatment is development of regular bowel habits and relief of symptoms. A Cochrane systematic review found weak evidence of any medication benefits for children with IBS (Huertas-Ceballos, Logan, Bennett, et al, 2009). A 2009 Cochrane systematic review found no high-quality evidence on the effectiveness of any dietary interventions that included fiber supplements, lactose free-diets, or lactobacillus supplementation for children with IBS (Huertas-Ceballos, Logan, Bennett, et al, 2009).

Nursing Care Management

![]() The primary nursing goal is family support and education. The disorder is stressful to children and parents. The nurse can help by providing support and reassurance that, although the symptoms are difficult to deal with, the disorder is not generally a threat to the child’s health (see Community Focus box).

The primary nursing goal is family support and education. The disorder is stressful to children and parents. The nurse can help by providing support and reassurance that, although the symptoms are difficult to deal with, the disorder is not generally a threat to the child’s health (see Community Focus box).

Inflammatory Conditions

![]() Appendicitis, inflammation of the vermiform appendix (blind sac at the end of the cecum), is the most common cause of emergency abdominal surgery in childhood. In the United States, 60,000 to 80,000 cases are diagnosed each year. The average age of children with appendicitis is 10 years, with boys and girls equally affected before puberty. Classically, the first symptom of appendicitis is periumbilical pain, followed by nausea, right lower quadrant pain, and later vomiting with fever (Kwok, Kim, and Gorelick, 2004). Perforation of the appendix can occur within approximately 48 hours of the initial complaint of pain. At the time of initial presentation, about one third of all cases involve an already perforated appendix. Complications from appendiceal perforation include major abscess, phlegmon, enterocutaneous fistula, peritonitis, and partial bowel obstruction (Kwok, Kim, and Gorelick, 2004). A phlegmon is an acute suppurative inflammation of subcutaneous connective tissue that spreads.

Appendicitis, inflammation of the vermiform appendix (blind sac at the end of the cecum), is the most common cause of emergency abdominal surgery in childhood. In the United States, 60,000 to 80,000 cases are diagnosed each year. The average age of children with appendicitis is 10 years, with boys and girls equally affected before puberty. Classically, the first symptom of appendicitis is periumbilical pain, followed by nausea, right lower quadrant pain, and later vomiting with fever (Kwok, Kim, and Gorelick, 2004). Perforation of the appendix can occur within approximately 48 hours of the initial complaint of pain. At the time of initial presentation, about one third of all cases involve an already perforated appendix. Complications from appendiceal perforation include major abscess, phlegmon, enterocutaneous fistula, peritonitis, and partial bowel obstruction (Kwok, Kim, and Gorelick, 2004). A phlegmon is an acute suppurative inflammation of subcutaneous connective tissue that spreads.

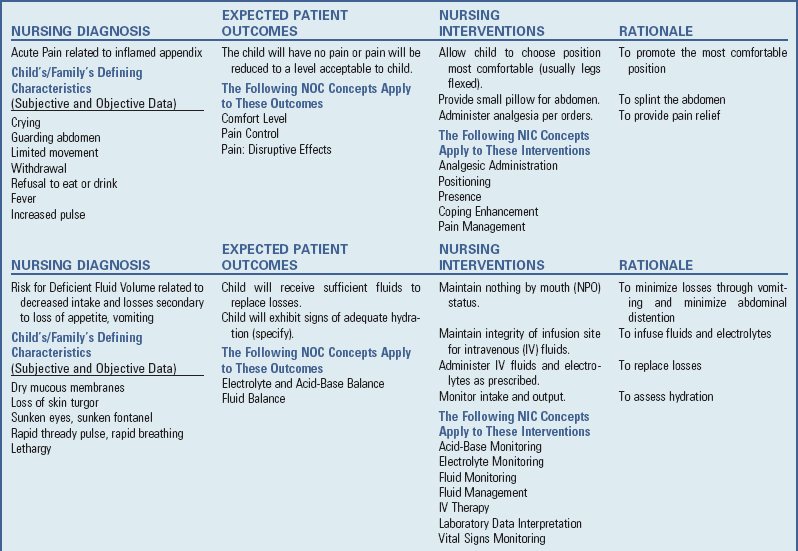

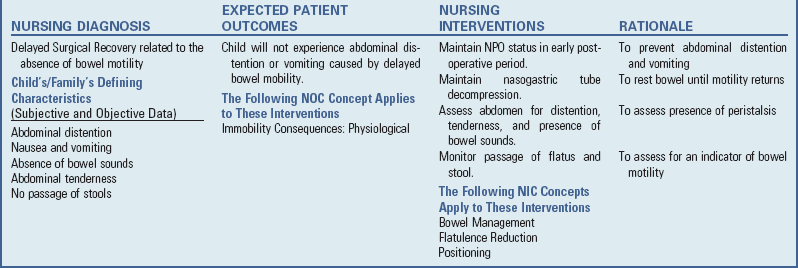

![]() Nursing Care Plan—The Child with Appendicitis

Nursing Care Plan—The Child with Appendicitis

Etiology

The cause of appendicitis is obstruction of the lumen of the appendix, usually by hardened fecal material (fecalith). Swollen lymphoid tissue, frequently occurring after a viral infection, can also obstruct the appendix. Another rare cause of obstruction is a parasite such as Enterobius vermicularis, or pinworms, which can obstruct the appendiceal lumen.

Pathophysiology

![]() With acute obstruction, the outflow of mucus secretions is blocked and pressure builds within the lumen, resulting in compression of blood vessels. The resulting ischemia is followed by ulceration of the epithelial lining and bacterial invasion. Subsequent necrosis causes perforation or rupture with fecal and bacterial contamination of the peritoneal cavity. The resulting inflammation spreads rapidly throughout the abdomen (peritonitis), especially in young children, who are unable to localize infection. Progressive peritoneal inflammation results in functional intestinal obstruction of the small bowel (ileus) because intense GI reflexes severely inhibit bowel motility. Because the peritoneum represents a major portion of total body surface, the loss of extracellular fluid to the peritoneal cavity leads to electrolyte imbalance and hypovolemic shock.

With acute obstruction, the outflow of mucus secretions is blocked and pressure builds within the lumen, resulting in compression of blood vessels. The resulting ischemia is followed by ulceration of the epithelial lining and bacterial invasion. Subsequent necrosis causes perforation or rupture with fecal and bacterial contamination of the peritoneal cavity. The resulting inflammation spreads rapidly throughout the abdomen (peritonitis), especially in young children, who are unable to localize infection. Progressive peritoneal inflammation results in functional intestinal obstruction of the small bowel (ileus) because intense GI reflexes severely inhibit bowel motility. Because the peritoneum represents a major portion of total body surface, the loss of extracellular fluid to the peritoneal cavity leads to electrolyte imbalance and hypovolemic shock.

Clinical Manifestations

The first symptom of appendicitis is usually colicky, cramping, abdominal pain located around the umbilicus (Box 33-7). Referred pain is the term used for this vague periumbilical localization. The midgut shares the same T10 dermatome, so pain is often perceived to be coming from this area. Generally, this pain progresses and becomes constant. The most important physical finding is focal abdominal tenderness. As the inflammation progresses to involve the serosa of the appendix and the peritoneum of the abdominal wall, the pain may shift to the right lower quadrant. The McBurney point, located two thirds the distance along a line between the umbilicus and the anterosuperior iliac spine, is the most common point of tenderness. Localized peritoneal signs may occur with gentle percussion or maneuvers such as heel strike or shaking the bed. Another helpful finding is Rovsing sign, tenderness in the right lower quadrant that occurs during palpation or percussion of other abdominal quadrants (Colvin, Bachur, and Kharbanda, 2007). Rebound tenderness—pain on deep palpation with sudden release—may be present, but is not a finding specific to appendicitis (Ceydeli, Lavotshkin, Yu, et al, 2006). Nausea, vomiting, and anorexia typically occur after the pain starts. Diarrhea, as well as other common signs of childhood illness such as upper respiratory tract congestion, poor feeding, lethargy, or irritability, may accompany appendicitis.

The child may not be able to walk well and may complain of pain in the right hip caused by inflammation in the psoas or iliopsoas muscles. Low-grade fever (>38° C [100.4° F]) may be present but occurs in only about 55% of all patients. The absence of fever does not exclude appendicitis. Temperature elevations of 38.8° to 39.4° C (102° to 103° F) can occur after perforation; however, very high fevers (>39.4° C [103° F]) are uncommon (Ceydeli, Lavotshkin, Yu, et al, 2006). Because of the great variability in the presentation and location of appendicitis, any child with focal tenderness, regardless of the location, should be considered to potentially have acute appendicitis (see Community Focus box).

Diagnostic Evaluation

![]() Diagnosis is not always straightforward. Fever, vomiting, abdominal pain, and an elevated white blood count are associated with appendicitis but are also seen in IBD, pelvic inflammatory disease, gastroenteritis, urinary tract infection, right lower lobe pneumonia, mesenteric adenitis, Meckel diverticulum, and intussusception. Prolonged symptoms and delayed diagnosis often occur in younger children, in whom the risk of perforation is greatest because of their inability to verbalize their complaints.

Diagnosis is not always straightforward. Fever, vomiting, abdominal pain, and an elevated white blood count are associated with appendicitis but are also seen in IBD, pelvic inflammatory disease, gastroenteritis, urinary tract infection, right lower lobe pneumonia, mesenteric adenitis, Meckel diverticulum, and intussusception. Prolonged symptoms and delayed diagnosis often occur in younger children, in whom the risk of perforation is greatest because of their inability to verbalize their complaints.

![]() Critical Thinking Case Study—Gastroenteritis

Critical Thinking Case Study—Gastroenteritis

![]() Critical Thinking Case Study—Gastrointestinal Problems

Critical Thinking Case Study—Gastrointestinal Problems

The diagnosis is based primarily on the history and physical examination (see Box 33-7). Pain, the cardinal feature, is initially generalized (usually periumbilical). However, it usually descends to the lower right quadrant. The most intense site of pain may be at McBurney point. Rebound tenderness is not a reliable sign and is extremely painful to the child. Referred pain, elicited by light percussion around the perimeter of the abdomen, indicates peritoneal irritation. Movement, such as riding over bumps in an automobile or gurney, aggravates the pain. In addition to pain, significant clinical manifestations include fever, a change in behavior, anorexia, and vomiting.

Laboratory studies usually include a complete blood count (CBC); urinalysis (to rule out a urinary tract infection); and, in adolescent females, serum human chorionic gonadotropin (to rule out an ectopic pregnancy). A white blood cell count greater than 10,000/mm3 and a C-reactive protein (CRP) are common but are not necessarily specific for appendicitis. An elevated percentage of bands (often referred to as “a shift to the left”) may indicate an inflammatory process. CRP is an acute-phase reactant that rises within 12 hours of the onset of infection.

Computed tomography (CT) scan has become the imaging technique of choice, although ultrasound may also be helpful in diagnosing appendicitis. A CT scan is considered positive in the presence of enlarged appendiceal diameter; appendiceal wall thickening; and periappendiceal inflammatory changes, including fat streaks, phlegmon, fluid collection, and extraluminal gas (Kaiser, Frenchner, and Jorulf, 2002).

Therapeutic Management

The treatment for appendicitis before perforation is surgical removal of the appendix (appendectomy). Usually antibiotics are administered preoperatively. Intravenous (IV) fluids and electrolytes are often required before surgery, especially if the child is dehydrated as a result of the marked anorexia characteristic of appendicitis.

The operation is usually performed through a right lower quadrant incision (open appendectomy). Laparoscopic surgery is increasingly being used to treat nonperforated acute appendicitis in pediatric patients. Three cannulas are inserted in the abdomen: one in the umbilicus, one in the left lower abdominal quadrant, and one in the suprapubic area. A small telescope is inserted through the left lower quadrant cannula, and an endoscopic stapler is inserted through the umbilical cannula. The appendix is ligated with the stapler and removed through the umbilical cannula. Advantages of laparoscopic appendectomy include reduced time in surgery and under anesthesia and also reduced risk of postoperative wound infection (Bensard, Hendrickson, Fyffe, et al, 2009).

Ruptured Appendix: Management of the child diagnosed with peritonitis caused by a ruptured appendix often begins preoperatively with IV administration of fluid and electrolytes, systemic antibiotics, and NG suction. Postoperative management includes IV fluids, continued administration of antibiotics, and NG suction for abdominal decompression until intestinal activity returns. Sometimes surgeons close the wound after irrigation of the peritoneal cavity. Other times, they leave the wound open (delayed closure) to prevent wound infection.