Chapter 3 Anamnesis (History)

The importance of a detailed clinical history, the anamnesis, cannot be overemphasized. Information is divided into two categories: basic facts necessary for every horse, and additional information from questions tailored to the specific horse. The veterinarian must understand the breed, use, and level of competition of each horse, because prognosis varies greatly among different types of sports horses. Firsthand experience of the particular type of sports horse being examined is useful but is not essential. Clinicians must understand the language associated with the particular sporting event, and this may be a challenge. For some sporting events, understanding the clinical history and having the ability to ask the right questions are like speaking a different language. A veterinarian unfamiliar with the sporting activity should briefly review the type of activities performed and the array of potential lameness problems encountered with them (see Chapter 106Chapter 107Chapter 108Chapter 109Chapter 110Chapter 111Chapter 112Chapter 113Chapter 114Chapter 115Chapter 116Chapter 117Chapter 118Chapter 119Chapter 120Chapter 121Chapter 122Chapter 123Chapter 124Chapter 125Chapter 126Chapter 127Chapter 128Chapter 129). In some instances the veterinarian may lose credibility when talking to trainers or riders, particularly those involved in upper-level competition, if they perceive unfamiliarity.

The veterinarian must understand the difference between subjective and objective information in the clinical history. Objective information is gained from the horse, and subjective information is perceived by the rider or owner. Knowledge about a horse’s performance such as “the horse is bearing out,” “the horse is on the right line,” “the horse is lugging in,” “the horse has just started to refuse fences,” or “the horse no longer takes the right lead” is valuable objective information. Common examples of information perceived by the owner or rider include “the horse feels off behind,” “the horse is stiff behind,” or “the horse is lame behind” and it “feels up high.” Such information generally is useful and indicates a change in the horse’s gait, but only an experienced rider or trainer can discriminate accurately between forelimb and hindlimb lameness at any gait. Erroneous information obtained from the rider can complicate communication during lameness examination, particularly if the individual is strong-willed and seemingly authoritative; this situation occurs if riders or trainers insist they are correct and the veterinarian disagrees. In my experience, many horses considered to have hindlimb lameness by a rider actually are lame in front, but convincing a disbelieving trainer is difficult. Similarly, lameness perceived as “up high” (in the upper hindlimb, pelvis, or back) in most horses originates from the lower part of the hindlimb. The veterinarian must understand that everyone is trying to resolve the problem, but sometimes diplomacy is needed for successful communication. The veterinarian must be forthright and objective to determine the current source of lameness, even if the determination contradicts well-intentioned but strong-willed trainers.

Clinical history is important but should not override clinical findings. In racehorses that perform at high speed, physical examination generally supports the finding that a horse bears away from the source of pain. During counterclockwise racing or training and with left forelimb lameness, a Thoroughbred (TB) will lug out (away from the inside of the track) and a Standardbred (STB) will be on the “left line” (bearing out; the driver must pull harder on the left line). Some horses, however, especially STBs with medial right forelimb pain, bear out particularly in the turns, presumably because the source of pain is medial or on the compression side of the limb.

The veterinarian must seek out as much information as possible, particularly if the problem is complex or not readily apparent. Videotapes are useful, particularly if the gait deficit, behavioral problem, or any other circumstances necessary to elicit the suspected lameness cannot be duplicated during the examination. Paraprofessionals working with the horse provide useful information, but not everyone may agree about the source of the problem, and in some instances diplomacy is key to negotiating among concerned individuals.

Clinical History: Basic Information

Signalment

Age

The age, sex, breed, and use of the horse are basic vital facts (Box 3-1). Flexural deformities, physitis, other manifestations of osteochondrosis, and angular limb deformities are age-related problems. Infectious arthritis (hematological origin), lateral luxation of the patella, and rupture of the common digital extensor tendon are conditions usually unique to foals. Emphasis on training skeletally immature, 2- and 3-year-old racehorses causes predictable soft tissue and bone changes, often resulting in stress-related cortical or subchondral bone injury. Liautard observed more than 100 years ago: “When an undeveloped colt, whose stamina is not yet established and constitution not yet confirmed, with tendons and ligaments relatively tender and weak, and bones scarcely out of the gristle, is unwisely condemned to hard labor, it is irrational to expect any other results than lesions of one or another portion of the abused apparatus of locomotion. They will be fortunate if they escape a fate still worse, and become sufferers from nothing worse than mere lameness.”1 This statement aptly summarizes the situation then and now. The high value of races for 2- and 3-year-olds results in high-intensity training for early 2-year-olds, which may result in injury such as maladaptive or nonadaptive remodeling of the third carpal bone (C3), precluding racing at a young age.

Basic and Specific Information

Some problems are unique to older horses (Box 3-2). Overall, osteoarthritis (OA) and other degenerative conditions such as navicular disease are most common but certainly are not unique to the geriatric horse. Some horses have a remarkably early onset of navicular disease or OA despite little physical work, suggesting a genetic predisposition to the condition. These problems worsen with advancing age, particularly if several limbs are involved. In former racehorses, progressive OA is of particular concern; this condition most commonly affects the carpal and metacarpophalangeal joints (Figure 3-1). Occasionally in older horses, severe, progressive OA of the carpometacarpal joint occurs without any history of carpal lameness (Figure 3-2). In some horses, angular deformities (the most common is carpus varus) develop at the carpometacarpal joint. Inexplicably severe OA of the carpometacarpal and middle carpal joints is most commonly seen in Arabian horses (see Chapter 38). Primary OA of this joint is rare in young horses, even in racehorses with middle carpal joint abnormalities, unless C3 slab fracture or infectious arthritis occurs. OA of the coxofemoral joint is rare in horses with the exception of young horses with osteochondrosis, but it does occur in older horses.

BOX 3-2 Summary of Lameness Conditions of the Geriatric Horse

* Some of these conditions are unique to the older horse and often are unexplainable.

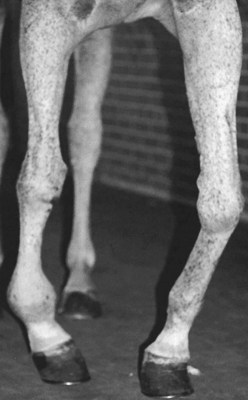

Fig. 3-1 An aged Thoroughbred broodmare with severe forelimb deformity caused by primary severe osteoarthritis of the right metacarpophalangeal joint and secondary or compensatory (chronic overload) carpus varus in the left forelimb.

Fig. 3-2 Dorsopalmar digital radiographic image of the right carpus in a 13-year-old Arabian mare with pronounced lameness as a result of severe, progressive osteoarthritis of the carpometacarpal and middle carpal joints (medial is to the right). There is substantial varus limb deformity present. Comfort improved after partial carpal arthrodesis.

(Courtesy Dr. Dean Richardson.)

An unusual group of soft tissue injuries of unknown origin occurs in older horses. Superficial digital flexor tendonitis and suspensory desmitis generally are considered overuse injuries and usually occur in upper-level performance horses or racehorses. However, severe tendonitis and desmitis do occur, often suddenly and without provocation, in older (teenage) horses. Horses usually are turned out at pasture when initial lameness is observed. In some horses, superficial digital flexor tendonitis is severe and progressive, later leading to flexural deformity because of adhesions. Suspensory desmitis may be unilateral or bilateral, may involve the forelimbs or hindlimbs but is more common in the hindlimbs, and is most common in the older broodmares. The name degenerative suspensory (ligament) desmitis (DSD) was given to a syndrome, often seen in older horses and most common in Peruvian Pasos, in which severe, often bilateral suspensory desmitis occurred2-4 (see Chapter 72). In a recent study horses other than Peruvian Pasos were affected, and an alternative name—equine systemic proteoglycan accumulation—was proposed, because abnormal accumulation of proteoglycans in many connective tissues was found.4 However this has recently been disputed5; the suspensory ligaments (SLs) and other tissues from affected Peruvian Pasos and unaffected STB and Quarter Horses were examined using Safranin-O staining for detection of proteoglycan. Proteoglycan deposition was not unique to the affected Peruvian Pasos, being present in the nuchal ligament, heart, muscle, and other tissues, with similar or greater amounts in the control horses. However greater amounts were detected in the SLs of affected horses compared with control horses. It was concluded that cartilage metaplasia and associated proteoglycan deposition in affected SLs was the response to injury rather than the cause. Further work is needed to define this important disease.

Older horses, particularly older broodmares, are at greater risk than younger horses to fracture long bones during recovery from general anesthesia.6 From 1988 to 1994, 9 of 14 horses with catastrophic fractures or dislocations that developed during recovery from general anesthesia were older than 10 years of age.

Age prominently affects prognosis. A common premise in considering lameness in foals is that young horses have time to outgrow the problem. Maturation will aid in angular limb deformities, some forms of osteochondrosis, and distal phalanx and diaphyseal fractures. However, fractures of important physes such as the proximal tibia may result in progressive angular deformities or disparity in limb length, limiting future prognosis. Early surgical management of flexural deformity of the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint before 6 to 8 months of age optimizes future soundness and the possibilities for normal hoof conformation. In one study the reported success rate was 80%.7 If surgical management is undertaken later in life or when deformity is severe, the prognosis decreases substantially. The prognosis for survival of foals treated for infectious arthritis is reasonable, but only 31% of TB foals and 36% of STB foals started one or more races, indicating that the prognosis for future racing performance is poor, because articular healing even in young foals is not possible.8

In middle-aged (12 to 18 years of age), upper-level performance horses, prognosis is difficult to assess, particularly in horses with several problems. Level of competition rather than age may be the most important factor, and often performance level declines.

Sex

Most lameness conditions affect stallions, geldings, and mares with similar frequency. Sex-specific conditions are unusual but do exist. The most important consideration, however, regarding the horse’s sex is future breeding potential or lack thereof in the case of geldings. In many types of horses, and specifically in racehorses, decisions about future performance or racing potential often are important when management options and financial aspects are considered. This factor is particularly important when life-or-death decisions must be made after catastrophic injury (see Chapters 13 and 104). Frank discussions about the prognosis for return to the current sporting activity or level of performance often are necessary, and the clinician should consider reproductive capability of the horse. Owners are more likely to refrain from racing females and elect treatment for geldings and, in some instances, stallions. Future stallion prospects usually must prove race or performance success, thereby putting pressure on trainers to continue horses in training or racing.

Behavioral abnormalities associated with the estrous cycle in fillies or mares are well recognized and may cause performance problems confused or misinterpreted as lameness (refusing fences, going off stride, striking) (see Chapter 12). An ill-defined behavioral problem in middle-aged nonracehorse mares could explain sudden performance problems often associated with or misinterpreted as lameness.9 Recurrent exertional rhabdomyolysis (RER) is more common in female TB racehorses10 and event horses.11 An association between sex and RER in STBs may exist and RER may be more common in fillies administered anabolic steroids.

Obscure or unexplained hindlimb lameness has been attributed, rightly or wrongly, to retained testicles. The origin of lameness in these horses is difficult to prove without removing the retained testicle, and anecdotal reports suggest that hindlimb lameness has resolved after castration in some horses. The origin of pain in an abdominal cryptorchid is difficult to explain and questionable. The source of pain may be easier to understand in a horse with a testicle located within the inguinal canal. Activity of the external and internal abdominal oblique muscles and tension on the spermatic cord are possible explanations.

Breed and Use

Most lameness conditions affect all breeds of horses. Although breed has considerable influence on sporting activity, sporting activity or use primarily has the greatest impact on lameness distribution (see Chapter 106Chapter 107Chapter 108Chapter 109Chapter 110Chapter 111Chapter 112Chapter 113Chapter 114Chapter 115Chapter 116Chapter 117Chapter 118Chapter 119Chapter 120Chapter 121Chapter 122Chapter 123Chapter 124Chapter 125Chapter 126Chapter 127Chapter 128Chapter 129).

Current Lameness

Determination of the Problem

Accurate information is necessary to determine precisely the horse’s current problem. Obtaining reliable information may be difficult if the horse has been purchased recently, if the horse has been claimed or changed trainers, or if you are giving a second opinion and have no past history with the horse. Additional objective information may be necessary to assess the effect of lameness on the horse’s performance. Evaluation of the horse’s race record may indicate when the problem began and if it is ongoing or new. The groom, rider (if not the owner), assistant trainer, blacksmith, and other paraprofessionals may have other pertinent information. Horses with poor performance usually are lame, although respiratory problems, rhabdomyolysis, shoeing, tack or equipment, and other medical problems can contribute.

The horse’s past history is important in determining the cause of the current problem, particularly in racehorses training or racing with existing low-grade OA that develop new overload injury to supporting limbs (secondary or compensatory lameness). Existing problems such as OA worsen insidiously but may reach critical levels, causing sudden, severe unexpected lameness. OA of the metacarpophalangeal joint may exist for months in racehorses without causing obvious lameness, although in many horses joint effusion ultimately leads to treatment (“maintenance injections”). The horse suddenly may be much lamer after racing or training, and the trainer may assume the cause is different. Because intraarticular analgesia may only partially relieve lameness, persuading the trainer that the problem is still the fetlock may be difficult. Horses can endure extensive cartilage damage in any joint for many months, but at some point they reach a threshold level beyond which they cannot tolerate the pain.

History of Trauma

Many lameness problems develop during or shortly after a traumatic incident, but unfortunately many owners presume trauma played a role even when no one witnessed an alleged incident. A common but often erroneous assumption when examining a lame foal is that the dam stepped on it, but usually infection is the cause. Clinical signs of osteochondritis dissecans of the shoulder or stifle often are expressed after a traumatic incident, and yet most lame weanlings or yearlings are assumed to be lame because of trauma, not a developmental problem. Some lameness problems appear after specific forms of trauma. Palmar carpal fractures occur most commonly in jumpers, but horses recovering from general anesthesia are at risk for this injury. Horses may be only mildly lame immediately after recovery, and the extent of injury is often not discovered until nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medication is discontinued, sometimes 7 to 10 days after the surgical procedure. A common history of horses with subluxation of the scapulohumeral joint (often called Sweeny or suprascapular nerve injury) is sudden profound lameness after being outside in a thunderstorm. Injury likely occurs when a horse runs into a solid object such as a tree, fence post, or building.

Duration

The veterinarian must understand the duration of the current lameness problem and determine whether a preexisting chronic, low-grade lameness exists and a sudden exacerbation of this problem has occurred, or a completely unrelated new problem has developed.

Worsening of Condition

The veterinarian must establish if the horse’s current problem is worsening or improving, under which conditions or circumstances the lameness deteriorates or improves, and if the horse responds to treatment such as shoeing or management changes. Most lameness problems worsen with time, particularly if training or performance continues despite owner or trainer recognition. Racehorses with stress-related bone injury often are noticeably lame after work but become sound relatively quickly, within 1 to 3 days. A minimal number of other clinical signs are present, particularly because the most commonly affected bones (tibia, humerus) are difficult to palpate and buried by soft tissue. This cycle of lame-sound-work-lame is an important part of the history.

Improvement of lameness with rest is important from historical and therapeutic perspectives. Lameness in most horses with severe articular damage, usually from severe OA, does not improve substantially with rest. Severe OA most commonly appears in the fetlock, femorotibial, and tarsocrural joints. Horses with fractures or mild to moderate soft tissue injuries generally improve with rest.

Warming into Lameness

Warming into lameness means the horse’s lameness worsens during the exercise period. Warming out of lameness means the lameness improves. This concept is important. Lameness associated with stress or incomplete fractures, soft tissue injuries (tendonitis and suspensory desmitis), splints, curb, and foot soreness worsens with exercise. In racehorses a worsening lameness appears as progressive bearing in or out during training or racing. In riding horses, this may be progressive stumbling, problems taking leads, progressive asymmetry in diagonals, or refusing to jump later fences. Horses with OA may be stiff and obviously lame at a walk, but lameness may improve with work. In western performance horses, OA of the proximal and distal interphalangeal joints and in some horses navicular syndrome cause lameness with this characteristic. The most dramatic example is distal hock joint pain, particularly in racehorses. Horses may be noticeably lame at a walk and trot, warm out of the lameness to the point of racing successfully, and then show pronounced lameness after a race.

One frequent statement at the racetrack is that the horse throws the lameness away at speed. This decrease occurs with some lameness conditions, such as distal hock joint pain, but two other factors are important. A horse may be able to race with lameness but not be able to perform at peak, particularly if lameness is bilateral. Horses often can race with bilateral conditions and show minimal signs of lameness, but performance is reduced. Lameness at the gallop may be impossible to perceive, and even at the fast trot or pace, most persons have difficulty seeing lameness. The same limitation occurs in observing a dressage or jumping horse at the canter. The veterinarian may gain some information by observing that a horse is reluctant to take either the left or right lead, but lameness is difficult if not impossible to detect at the canter. Unless slow-motion video analysis is available, the horse appears to be able to “throw lameness away,” but lameness is present but difficult to see. In this situation, horses do not warm out of lameness but simply cope with the pain while racing. Horses in this situation are at risk for developing compensatory problems.

Older horses with OA may have difficulty in getting up and later may warm out of the lameness. Horses of any age with pelvic fractures or severe lameness may have difficulty in rising.

Recent Management Changes

Many lameness conditions start after a change in management. Changes in shoeing, training or performance intensity, surface, housing, and diet or other medical issues can have a profound effect on the musculoskeletal system. Changes in ownership often dictate changes in exercise intensity and certainly in owner expectations. The veterinarian must be careful in questioning and responding to questions if a horse has been purchased recently, especially if a colleague performed a prepurchase examination. Clinicians should avoid implying that a condition may have been preexisting or missed.

Shoeing

The veterinarian should determine when the horse was last shod and whether the shoeing strategy was changed. Nail bind often causes acute progressive lameness related temporally to shoe application. Abscesses that result from a “close nail” may take several days to cause lameness.

Foot balance is critical and, in some horses, changing foot angles results in lameness. A substantial increase or decrease in heel angle in a horse with chronic laminitis may exacerbate lameness. In horses with palmar foot pain, raising the heel angle may produce an obvious improvement in clinical signs briefly, whereas in horses with subchondral pain of the distal phalanx, raising the heel may worsen clinical signs. In racehorses with “sore feet” resulting from soft tissue and bone pain, changing shoes may result in improvement, related in part to temporary reduction in weight bearing in the painful area of the foot.

Temporary lameness often occurs in horses with recently trimmed but unshod hooves, particularly if the horses’ hooves are trimmed aggressively or the ground is unusually hard for that time of year. The veterinarian must remember that a horse with recently trimmed hooves often shows bilateral forelimb lameness when trotted on flat or uneven hard surfaces, regardless of the primary cause of the current lameness. The horse should be reassessed on a soft surface.

Attempts to make both front feet symmetrical may create substantial lameness immediately after trimming. Horses may cope well with different size and shaped front feet, but when radical trimming is performed, they may develop severe lameness.

The veterinarian must determine whether any recent or past changes in shoeing either improved or worsened lameness. Lameness in a STB trotter with foot pain may be improved by changing from conventional shoes, such as half-round or flat steel shoes in the front to a “flip-flop” shoe.

The farrier often first notices a common problem that a horse is reluctant to pick up the hindlimbs. In some horses this problem is purely behavioral, whereas in others it is a real sign of pain. This history most often is associated with conditions such as OA of one or more joints but also may be a sign of pelvic or sacroiliac pain. In Warmbloods, draft breeds, and draft-cross horses, reluctance to pick up a hindlimb may be an early sign of shivers.

Training or Performance Intensity

Lameness that worsens in response to recent increase in training intensity may be related to stress-related subchondral or cortical bone injury. Stress fractures, bucked shins, or maladaptive or nonadaptive stress-related injuries of subchondral bone occur typically during defined periods of training and often after brief periods of rest. When horses in active race training are given time off, even brief periods such as 7 to 21 days, bone undergoes detraining, leaving it subject to stress-related injury. If training resumes at the prerest level or is accelerated, stress fractures or bucked shins often develop. In 3-year-old TBs, stress fractures of the humerus often occur within 4 to 8 weeks after returning to training. Bucked shins often develop in 2-year-old TB racehorses after a brief rest period for an unrelated medical condition.

Surface

Most lameness conditions worsen if the horse performs on a harder surface. In show horses such as the Arabian or half-Arabian breeds, foot lameness often results when horses are warmed up or shown on harder surfaces. An association exists between fracture development and hard racing surfaces. A dramatic change in any racing surface may lead to unexpected episodic lameness in racehorses. On breeding farms, anecdotal evidence suggests drought conditions causing harder than normal pastures lead to a higher prevalence of osteochondrosis or distal phalanx fractures.

Lameness that is most pronounced on hard surfaces is often seen with conditions of the foot. Lameness that worsens on softer surfaces, however, may be associated with soft tissue injuries such as proximal suspensory desmitis. Uneven surfaces may exacerbate lameness and other gait abnormalities. Horses prone to stumbling on uneven surfaces may have palmar foot pain, proximal suspensory desmitis, or neurological disease. Horses with bilateral lameness may be lame in one leg going in a particular direction on a banked surface (such as a racetrack) and lame in the opposite leg going the other way. Bilateral lameness may be confused with other causes of poor performance because of inconsistencies in gait. Lameness may worsen or improve when a horse goes uphill or downhill.

Diet and Health

Changes in diet or dietary factors may lead to or exacerbate existing lameness conditions. Dietary factors, especially dietary excesses or deficiencies, are important in the many manifestations of developmental orthopedic disease (see Chapter 55). Sudden changes in diet, such as those associated with turning horses out on lush pastures or consumption of large quantities of grain (grain overload), may cause laminitis or exacerbate existing chronic laminitis. Overweight horses normally consuming a high-grain diet may be prone to laminitis or gastrointestinal tract disturbances that lead to laminitis.

Lameness may be associated with, or result from, other medical conditions. Obvious associations exist in foals; for example, conditions such as infectious arthritis and physitis are associated with umbilical, gastrointestinal, or respiratory tract infections. Immune-mediated synovitis also occurs in older foals with chronic infections (see Chapter 66). In adult horses, infectious arthritis generally develops after intraarticular injections or penetrating wounds, but may result from hematological spread of bacteria. Occasionally, horses develop distal extremity edema and lameness after vaccination, presumably caused by vasculitis or other immune-related mechanisms. Similar signs appear in horses with purpura hemorrhagica or viral illnesses such as equine viral arteritis.

Housing

Many lameness conditions develop while a horse is turned out, or as the result of turnout, often as the result of trauma such as kick wounds or fence-related injuries. Sudden changes in weather may excite horses, particularly those turned out at pasture. Minimizing problems with turnout requires the use of well-groomed and well-maintained pastures or paddocks with individual paddocks to reduce horse-to-horse interactions.

Dramatic housing changes have a substantial impact on the development of lameness. Shipping to and from sales, foaling, and weaning are associated with soft tissue injuries, puncture or kick wounds, and other injuries.

Current Medication Changes and Response

The veterinarian must establish if the horse currently is receiving medication or was administered medication recently and the response to treatment. Response to medication or a management change is important information in formulating a treatment plan. For example, recent improvement with rest and the administration of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs indicates more of the same treatment may be reasonable. The veterinarian must establish dosages of medication because a horse may not respond to phenylbutazone because of underdosage.

Many owners and trainers do not understand that although intraarticular analgesia relieves lameness, intraarticular medication may not, thus causing doubt about the diagnosis. This characteristic commonly appears in horses with subchondral bone pain and is useful in diagnosis. Horses with early OA and negative or equivocal radiological signs, or those with short, incomplete fractures, often do not respond to intraarticular medication. Negative radiological findings are a good sign because dramatic radiological evidence of subchondral lucency or fracture reduces the prognosis considerably. However, convincing the trainer of the validity of the diagnosis may be difficult.

The amount of rest is important. Many acquired conditions, such as OA, or degenerative conditions, such as navicular syndrome, take many months and usually years to develop. Therefore expectation that a horse will show marked improvement with a brief rest period is unreasonable. Lameness in many horses with severe OA may not improve substantially, even with prolonged rest. In horses with early OA in which pain occurs primarily in subchondral bone and for which radiological findings are negative or equivocal, rest or controlled exercise for 3 to 6 months may be necessary. The same regimen applies for horses with navicular syndrome, fractures, and many soft tissue injuries.

Quality of rest is equally important. Did the horse receive absolute box stall rest with handwalking, or was it lunged or turned out in a paddock or field with other horses? Was a brief rest period followed by an attempt to ride or train the horse? Those associated with the horse often consider this type of intermittent rest complete rest, but many conditions remain chronically active. Without adequate rest, reinjury follows temporary improvement and early healing, highlighting that, in my opinion, turnout is the antithesis of healing!

Past Lameness History

Obtaining the horse’s entire lameness history may not be necessary or possible, but the veterinarian should gather as much information as is practically available. Prognosis for many injuries is affected adversely by recurrence, and often management options differ in these situations. Recurrence may prompt more aggressive therapy, considerations for referral, or perhaps surgical evaluation if the problem involves a joint. If a reliable diagnosis was made previously, retreatment for the past problem may be a reasonable or preferred management approach, particularly between races or competitions. If a horse responded previously to intraarticular medication, reinjection may be reasonable. However, in many horses with progressive OA, results of additional therapy often are diminished. The veterinarian should not assume that the failed response to intraarticular medication means the problem lies elsewhere because medication does not affect subchondral bone pain in early or late OA.

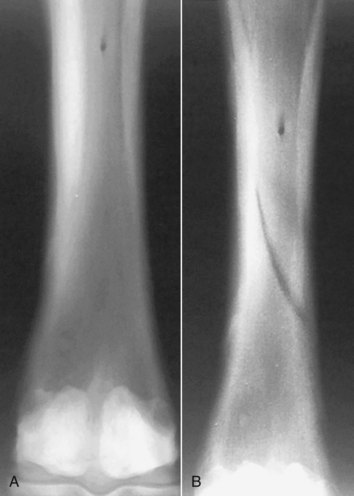

Recent history is important. Small, innocuous-looking wounds over the third metacarpal bone or third metatarsal bone, radius, or tibia may be associated with bone trauma with delayed-onset severe lameness. Incomplete or spiral fractures may develop from small cortical defects (Figure 3-3). Catastrophic failure of long bones occurs even when initial radiographs show no or minimal cortical trauma. The radius appears to be at greatest risk (Figure 3-4).

Fig. 3-3 Initial (A) and 2-week follow-up (B) dorsopalmar radiographic image of the left third metacarpal bone in an 18-year-old Thoroughbred gelding. The initial image was obtained after the horse was found to have a small skin wound in the region but was sound. Acute, severe lameness developed 9 days after initial injury, and the follow-up radiograph shows a long oblique fracture of the third metacarpal bone.

(Courtesy Dr. Janet Durso, 2001.)

Fig. 3-4 Craniocaudal radiographic image of the left antebrachium of a 5-year-old Thoroughbred mare showing a displaced, long oblique fracture of the radius. This filly had sustained a small puncture wound to the lateral aspect of the antebrachium 5 days earlier but was sound. The mare was turned out and developed acute, severe lameness and was later euthanized.

New problems may and often do arise despite a long history of recurrent lameness. Comprehensive reevaluation is the best and safest approach to avoid delays in proper diagnosis and treatment.

Further Information

Full understanding of a horse’s use, type and level of sporting activity, and value, all of which help the veterinarian assess prognosis, requires specific information. If a horse previously was under the veterinary care of another individual in the same or a different practice, it is important to obtain accurate case records and view previous radiographs and other images.