Core Interview

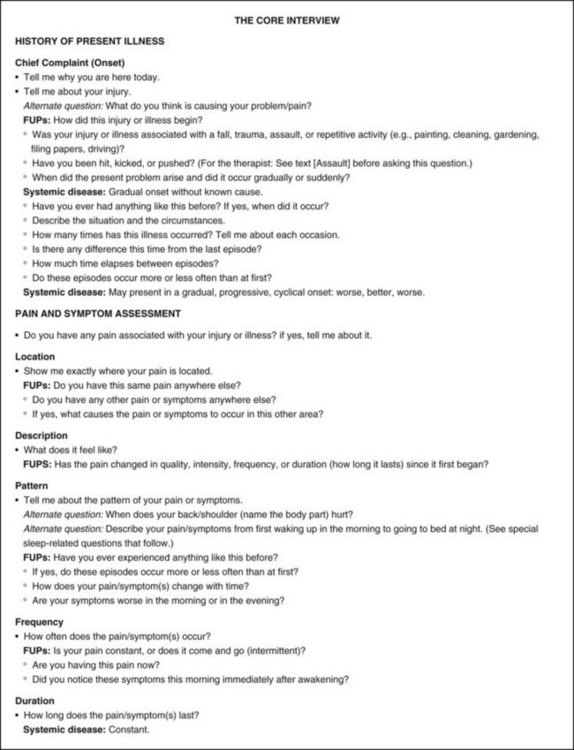

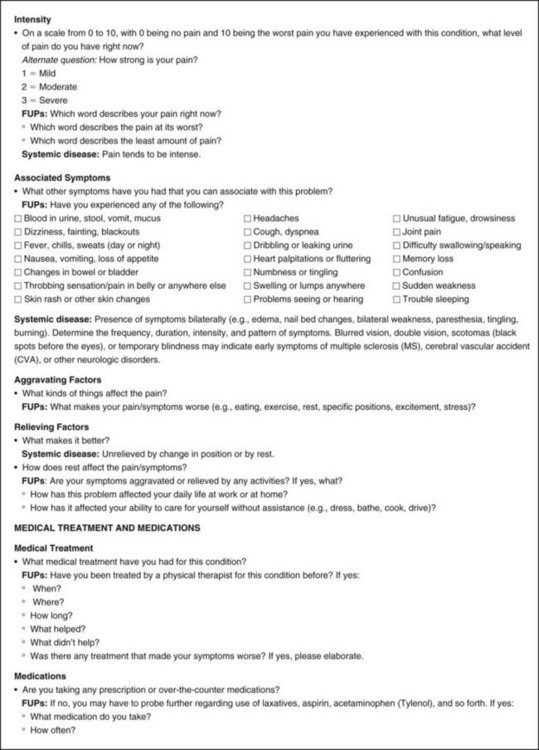

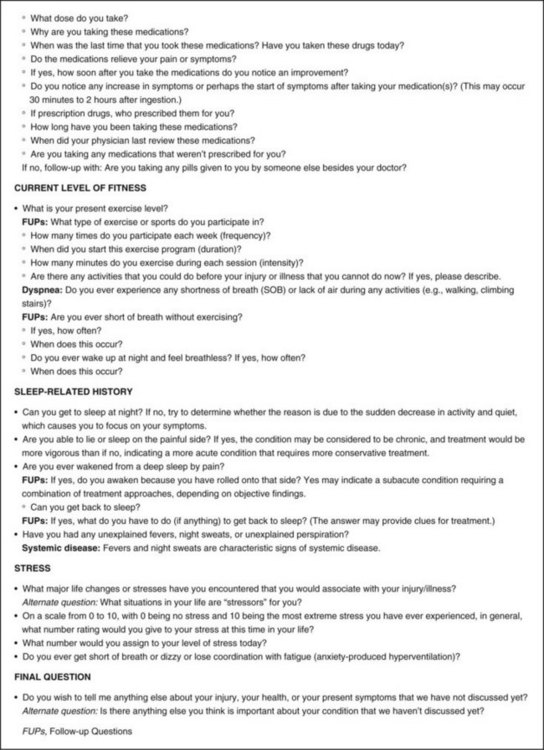

Once the therapist reviews the results of the Family/Personal History form and reviews any available medical records for the client, the client interview (referred to as the Core Interview in this text) begins (Fig. 2-3).

Screening questions may be interspersed throughout the Core Interview and/or presented at the end. When to screen depends on the information provided by the client during the interview.

Special questions related to sensitive topics such as sexual history, assault or domestic violence, and substance or alcohol use are often left to the end or even on a separate day after the therapist has established sufficient rapport to broach these topics.

History of Present Illness

The history of present illness (often referred to as the chief complaint and other current symptoms) may best be obtained through the use of open-ended questions. This section of the interview is designed to gather information related to the client’s reason(s) for seeking clinical treatment.

The following open-ended statements may be appropriate to start an interview:

During this initial phase of the interview, allow the client to carefully describe his or her current situation. Follow-up questions and paraphrasing as shown in Fig. 2-3 can be used in conjunction with the primary, open-ended questions.

Pain and Symptom Assessment

The interview naturally begins with an assessment of the chief complaint, usually (but not always) pain. Chapter 3 of this text presents an in-depth discussion of viscerogenic sources of NMS pain and pain assessment, including questions to ask to identify specific characteristics of pain.

For the reader’s convenience, a brief summary of these questions is included in the Core Interview (see Fig. 2-3). In addition, the list of questions is included in Appendices B-28 and C-7 for use in the clinic.

Beyond a pain and symptom assessment, the therapist may conduct a screening physical examination as part of the objective assessment (see Chapter 4). Table 4-13 and Boxes 4-15 and 4-16 are helpful tools for this portion of the examination and evaluation.

Insidious Onset

When the client describes an insidious onset or unknown cause, it is important to ask further questions. Did the symptoms develop after a fall, trauma (including assault), or some repetitive activity (such as painting, cleaning, gardening, filing, or driving long distances)?

The client may wrongly attribute the onset of symptoms to a particular activity that is really unrelated to the current symptoms. The alert therapist may recognize a true causative factor. Whenever the client presents with an unknown etiology of injury or impairment or with an apparent cause, always ask yourself these questions:

Trauma

When the symptoms seem out of proportion to the injury or when the symptoms persist beyond the expected time for that condition, a red flag should be raised in the therapist’s mind. Emotional overlay is often the most suspected underlying cause of this clinical presentation. But trauma from assault and undiagnosed cancer can also present with these symptoms.

Even if the client has a known (or perceived) cause for his or her condition, the therapist must be alert for trauma as an etiologic factor. Trauma may be intrinsic (occurring within the body) or extrinsic (external accident or injury, especially assault or domestic violence).

Twenty-five percent of clients with primary malignant tumors of the musculoskeletal system report a prior traumatic episode. Often the trauma or injury brings attention to a preexisting malignant or benign tumor. Whenever a fracture occurs with minimal trauma or involves a transverse fracture line, the physician considers the possibility of a tumor.

Intrinsic Trauma: An example of intrinsic trauma is the unguarded movement that can occur during normal motion. For example, the client who describes reaching to the back of a cupboard while turning his or her head away from the extended arm to reach that last inch or two. He or she may feel a sudden “pop” or twinge in the neck with immediate pain and describe this as the cause of the injury.

Intrinsic trauma can also occur secondary to extrinsic (external) trauma. A motor vehicle accident, assault, fall, or known accident or injury may result in intrinsic trauma to another part of the musculoskeletal system or other organ system. Such intrinsic trauma may be masked by the more critical injury and may become more symptomatic as the primary injury resolves.

Take, for example, the client who experiences a cervical flexion/extension (whiplash) injury. The initial trauma causes painful head and neck symptoms. When these resolve (with treatment or on their own), the client may notice midthoracic spine pain or rib pain.

The midthoracic pain can occur when the spine fulcrums over the T4-6 area as the head moves forcefully into the extended position during the whiplash injury. In cases like this, the primary injury to the neck is accompanied by a secondary intrinsic injury to the midthoracic spine. The symptoms may go unnoticed until the more painful cervical lesion is treated or healed.

Likewise, if an undisplaced rib fracture occurs during a motor vehicle accident, it may be asymptomatic until the client gets up the first time. Movement or additional trauma may cause the rib to displace, possibly puncturing a lung. These are all examples of intrinsic trauma.

Extrinsic Trauma: Extrinsic trauma occurs when a force or load external to the body is exerted against the body. Whenever a client presents with NMS dysfunction, the therapist must consider whether this was caused by an accident, injury, or assault.

The therapist must remain aware that some motor vehicle “accidents” may be reported as accidents but are, in fact, the result of domestic violence in which the victim is pushed, shoved, or kicked out of the car or deliberately hit by a vehicle.

Assault: Domestic violence is a serious public health concern that often goes undetected by clinicians. Women (especially those who are pregnant or disabled), children, and older adults are at greatest risk, regardless of race, religion, or socioeconomic status. Early intervention may reduce the risk of future abuse.

It is imperative that physical therapists and physical therapist assistants remain alert to the prevalence of violence in all sectors of society. Therapists are encouraged to participate in education programs on screening, recognition, and treatment of violence and to advocate for people who may be abused or at risk for abuse.189

Addressing the possibility of sexual or physical assault/abuse during the interview may not take place until the therapist has established a working relationship with the client. Each question must be presented in a sensitive, respectful manner with observation for nonverbal cues.

Although some interviewing guidelines are presented here, questioning clients about abuse is a complex issue with important effects on the outcome of rehabilitation. All therapists are encouraged to familiarize themselves with the information available for screening and intervening in this important area of clinical practice.

Generally, the term abuse encompasses the terms physical abuse, mental abuse, sexual abuse, neglect, self-neglect, and exploitation (Box 2-8). Assault is by definition any physical, sexual, or psychologic attack. This includes verbal, emotional, and economic abuse. Domestic violence (DV) or intimate partner violence (IPV) is a pattern of coercive behaviors perpetrated by a current or former intimate partner that may include physical, sexual, and/or psychologic assaults.190,191

Violence against women is more prevalent and dangerous than violence against men,192 but men can be in an abusive relationship with a parent or partner (male or female).193,194 For the sake of simplicity, the terms “she” and “her” are used in this section, but this could also be “he” and “his.”

Intimate partner assault may be more prevalent against gay men than against heterosexual men.195 Many men have been the victims of sexual abuse as children or teenagers.

Child abuse includes neglect and maltreatment that includes physical, sexual, and emotional abuse. Failure to provide for the child’s basic physical, emotional, or educational needs is considered neglect even if it is not a willful act on the part of the parent, guardian, or caretaker.187

Screening for Assault or Domestic Violence: The American Medical Association (AMA) and other professional groups recommend routine screening for domestic violence. At least one study has shown that screening does not put victims at increased risk for more violence later. Many victims who participated in the study contacted community resources for victims of domestic violence soon after completing the study survey.196

As health care providers, therapists have an important role in helping to identify cases of domestic violence and abuse. Routinely incorporating screening questions about domestic violence into history taking only takes a few minutes and is advised in all settings. When interviewing the client it is often best to use some other word besides “assault.”

Many people who have been physically struck, pushed, or kicked do not consider the action an assault, especially if someone they know inflicts it. The therapist may want to preface any general screening questions with one of the following lead-ins:

Several screening tools are available with varying levels of sensitivity and specificity. The Woman Abuse Screening Tool (WAST) has direct questions that are easy to understand (e.g., Have you been abused physically, emotionally, or sexually by an intimate partner?) but have not been independently validated.197 There is also the Composite Abuse Scale (CAS),198 the Partner Violence Screen (PVS),199 and Index of Spouse Abuse.

The PVS, a quick three-question screening tool, may be easiest to use as it is positive for partner violence if even one question is answered “yes”199 (see FUPs just below). When compared with other screening tools, the PVS has 64.5% to 71.4% sensitivity in detecting partner abuse and 80.3% to 84.4% specificity.199

Follow-up questions will depend on the client’s initial response.187 The timing of these personal questions can be very delicate. A private area for interviewing is best at a time when the client is alone (including no children, friends, or other family members). The following may be helpful:

During the interview (and subsequent episode of care), watch out for any of the risk factors and red flags for violence (Box 2-9) or any of the clinical signs and symptoms listed in this section. The physical therapist should not turn away from signs of physical or sexual abuse.

In attempting to address such a sensitive issue, the therapist must make sure that the client will not be endangered by intervention. Physical therapists who are not trained to be counselors should be careful about offering advice to those believed to have sustained abuse (or even those who have admitted abuse).

The best course of action may be to document all observations and, when necessary or appropriate, to communicate those documented observations to the referring or family physician. When an abused individual asks for help or direction, the therapist must always be prepared to provide information about available community resources.

In considering the possibility of assault as the underlying cause of any trauma, the therapist should be aware of cultural differences and how these compare with behaviors that suggest excessive partner control. For example:

Elder Abuse: Health care professionals are becoming more aware of elder abuse as a problem. Last year, more than 5 million cases of elder abuse were reported. It is estimated that 84% of elder abuse and neglect is never reported. The International Network for the Prevention of Elder Abuse has more information (www.inpea.net).

The therapist must be alert at all times for elder abuse. Skin tears, bruises, and pressure ulcers are not always predictable signs of aging or immobility. During the screening process, watch for warning signs of elder abuse (Box 2-10).

Clinical Signs and Symptoms: Physical injuries caused by battering are most likely to occur in a central pattern (i.e., head, neck, chest/breast, abdomen). Clothes, hats, and hair easily hide injuries to these areas, but they are frequently observable by the therapist in a clinical setting that requires changing into a gown or similar treatment attire.

Assessment of cutaneous manifestations of abuse is discussed in greater detail in this text in Chapter 4. The therapist should follow guidelines provided when documenting the nature (e.g., cut, puncture, burn, bruise, bite), location, and detailed description of any injuries. The therapist must be aware of Mongolian spots, which can be mistaken for bruising from child abuse in certain population groups (see Fig. 4-25).

In the pediatric population, fractures of the ribs, tibia/fibula, radius/ulna, and clavicle are more likely to be associated with abuse than with accidental trauma, especially in children less than 18 months old. In the group older than 18 months, a rib fracture is highly suspicious of abuse.200

A link between a history of sexual or physical abuse and multiple somatic and other medical disorders in adults (e.g., cardiovascular,201 GI, endocrine,202 respiratory, gynecologic, headache and other neurologic problems) has been confirmed.203

Workplace Violence: Workers in the health care profession are at risk for workplace violence in the form of physical assault and aggressive acts. Threats or gestures used to intimidate or threaten are considered assault. Aggressive acts include verbal or physical actions aimed at creating fear in another person. Any unwelcome physical contact from another person is battery. Any form of workplace violence can be perpetrated by a co-worker, member of a co-worker’s family, by a client, or a member of the client’s family.205

Predicting violence is very difficult, making this occupational hazard one that must be approached through preventative measures rather than relying on individual staff responses or behavior. Institutional policies must be implemented to protect health care workers and provide a safe working environment.206

Therapists must be alert for risk factors (e.g., dependence on drugs or alcohol, depression, signs of paranoia) and behavioral patterns that may lead to violence (e.g., aggression toward others, blaming others, threats of harm toward others) and immediately report any suspicious incidents or individuals.205

Clients with a mental disorder and history of substance abuse have the highest probability of violent behavior. Adverse drug events can lead to violent behavior, as well as conditions that impair judgment or cause confusion, such as alcohol- or HIV-induced encephalopathy, trauma (especially head trauma), seizure disorders, and senility.205

The Physical Therapist’s Role: Providing referral to community agencies is perhaps the most important step a health care provider can offer any client who is the victim of abuse, assault, or domestic violence of any kind. Experts report that the best approach to addressing abuse is a combined law enforcement and public health effort.

Any health care professional who asks these kinds of screening questions must be prepared to respond. Having information and phone numbers available is imperative for the client who is interested. Each therapist must know what reporting requirements are in place in the state in which he or she is practicing (Case Example 2-9).

The therapist should avoid assuming the role of “rescuer” but rather recognize domestic violence, offer a plan of care and intervention for injuries, assess the client’s safety, and offer information regarding support services. The therapist should provide help at the pace the client can handle. Reporting a situation of domestic violence can put the victim at risk.

The client usually knows how to stay safe and when to leave. Whether leaving or staying, it is a complex process of decision making influenced by shame, guilt, finances, religious beliefs, children, depression, perceptions, and realities. The therapist does not have to be an expert to help someone who is a victim of domestic violence. Identifying the problem for the first time and listening is an important first step.

During intervention procedures, the therapist must be aware that hands-on techniques, such as pushing, pulling, stretching, compressing, touching, and rubbing, may impact a client with a history of abuse in a negative way. Behaviors, such as persistence in cajoling, cheerleading, and demanding compliance, meant as encouragement on the part of the therapist may further victimize the individual.207

Reporting Abuse: The law is clear in all U.S. states regarding abuse of a minor (under age 18 years) (Box 2-11):

When a professional has reasonable cause to suspect, as a result of information received in a professional capacity, that a child is abused or neglected, the matter is to be reported promptly to the department of public health and human services or its local affiliate.208

Guidelines for reporting abuse in adults are not always so clear. Some states require health care professionals to notify law enforcement officials when they have treated any individual for an injury that resulted from a domestic assault. There is much debate over such laws as many domestic violence advocate agencies fear mandated police involvement will discourage injured clients from seeking help. Fear of retaliation may prevent abused persons from seeking needed health care because of required law enforcement involvement.

The therapist should be familiar with state laws or statutes regarding domestic violence for the geographic area in which he or she is practicing. The Elder Justice Act of 2003 requires reporting of neglect or assault in long-term care facilities in all 50 U.S. states. The Elder Justice Act and the Patient Safety Abuse Prevention Act of 2010 provides funding ($3.9 billion) to establish advisory departments, justice resource centers, ombudsman training, nursing home training, and support for Adult Protective Services (APS). The National Center on Elder Abuse (NCEA) has more information (www.ncea.aoa.gov).

Documentation: Most state laws also provide for the taking of photographs of visible trauma on a child without parental consent. Written permission must be obtained to photograph adults. Always offer to document the evidence of injury. The APTA publications on domestic violence, child abuse, and elder abuse provide reproducible documentation forms and patient resources.187,209,210

Even if the client does not want a record of the injury on file, he or she may be persuaded to keep a personal copy for future use if a decision is made to file charges or prosecute at a later time. Polaroid and digital cameras make this easy to accomplish with certainty that the photographs clearly show the extent of the injury or injuries.

The therapist must remember to date and sign the photograph. Record the client’s name and injury location on the photograph. Include the client’s face in at least one photograph for positive identification. Include a detailed description (type, size, location, depth) and how the injury/injuries occurred.

Record the client’s own words regarding the assault and the assailant. For example, “Ms. Jones states, ‘My partner Doug struck me in the head and knocked me down.’ ” Identifying the presumed assailant in the medical record may help the client pursue legal help.211

Resources: Consult your local directory for information about adult and child protection services, state elder abuse hotlines, shelters for the battered, or other community services available in your area. For national information, contact:

• National Domestic Violence Hotline. Available 24 hours/day with information on shelters, legal advocacy and assistance, and social service programs. Available at www.ndvh.org or 1-800-799-SAFE (1-800-799-7233).

• Family Violence Prevention Fund. Updates on legislation related to family violence, information on the latest tools and research on prevention of violence against women and children. Posters, displays, safety cards, and educational pamphlets for use in a health care setting are also available at http://endabuse.org/ or 1-415-252-8900.

• U.S. Department of Justice. Office on Violence Against Women provides lists of state hotlines, coalitions against domestic violence, and advocacy groups (www.ovw.usdoj.gov/).

• Elder Care Locator. Information on senior services. The service links those who need assistance with state and local area agencies on aging and community-based organizations that serve older adults and their caregivers www.eldercare.gov/ or 1-800-677-1116.

• U.S. Department of HHS Administration for Children and Families. Provides fact sheets, laws and policies regarding minors, and phone numbers for reporting abuse. Available at www.acf.hhs.gov/ or 1-800-4-A-CHILD (1-800-422-4453).

Specific websites devoted to just men, just women, or any other specific group are available. Anyone interested can go to www.google.com and type in key words of interest.

The APTA offers three publications related to domestic violence, available online at www.apta.org (click on Areas of Interest>Publications):

Medical Treatment and Medications

Medical treatment includes any intervention performed by a physician (family practitioner or specialist), dentist, physician’s assistant, nurse, nurse practitioner, physical therapist, or occupational therapist. The client may also include chiropractic treatment when answering the question:

In addition to eliciting information regarding specific treatment performed by the medical community, follow-up questions relate to previous physical therapy treatment:

Knowing the client’s response to previous types of treatment techniques may assist the therapist in determining an appropriate treatment protocol for the current chief complaint. For example, previously successful treatment intervention described may provide a basis for initial treatment until the therapist can fully assess the objective data and consider all potential types of treatments.

Medications

Medication use, especially with polypharmacy, is important information. Side effects of medications can present as an impairment of the integumentary, musculoskeletal, cardiovascular/pulmonary, or neuromuscular system. Medications may be the most common or most likely cause of systemically induced NMS signs and symptoms.

Please note the use of a new term: hyperpharmacotherapy. Whereas polypharmacy is often defined as the use of multiple medications to treat health problems, the term has also been expanded to describe the use of multiple pharmacies to fill the same (or other) prescriptions, high-frequency medications, or multiple-dose medications. Hyperpharmacotherapy is the current term used to describe the excessive use of drugs to treat disease, including the use of more medications than are clinically indicated or the unnecessary use of medications.

Medications (either prescription, shared, or OTC) may or may not be listed on the Family/Personal History form at all facilities. Even when a medical history form is used, it may be necessary to probe further regarding the use of over-the-counter preparations such as aspirin, acetaminophen (Tylenol), ibuprofen (e.g., Advil, Motrin), laxatives, antihistamines, antacids, and decongestants or other drugs that can alter the client’s symptoms.

It is not uncommon for adolescents and seniors to share, borrow, or lend medications to friends, family members, and acquaintances. In fact, medication borrowing and sharing is a behavior that has been identified in patients of all ages.212

Most of the sharing and borrowing is done without consulting a pharmacist or medical doctor. The risk of allergic reactions or adverse drug events is much higher under these circumstances than when medications are prescribed and taken as directed by the person for whom they were intended.213

Risk Factors for Adverse Drug Events: Pharmacokinetics (the processes that affect drug movement in the body) represents the biggest risk factor for adverse drug events (ADEs). An ADE is any unexpected, unwanted, abnormal, dangerous, or harmful reaction or response to a medication. Most ADEs are medication reactions or side effects.

A drug-drug interaction occurs when medications interact unfavorably, possibly adding to the pharmacologic effects. A drug-disease interaction occurs when a medication causes an existing disease to worsen. Absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion are the main components of pharmacokinetics affected by age,56 size, polypharmacy or hyperpharmacotherapy, and other risk factors listed in Box 2-12.

Once again, ethnic background is a risk factor to consider. Herbal and home remedies may be used by clients based on their ethnic, spiritual, or cultural orientation. Alternative healers may be consulted for all kinds of conditions from diabetes to depression to cancer. Home remedies can be harmful or interact with some medications.

Some racial groups respond differently to medications. Effectiveness and toxicity can vary among racial and ethnic groups. Differences in metabolic rate, clinical drug responses, and side effects of many medications, such as antihistamines, analgesics, cardiovascular agents, psychotropic drugs, and CNS agents, have been documented. Genetic factors also play a significant role.214,215

Women metabolize drugs differently throughout the month as influenced by hormonal changes associated with menses. Researchers are investigating the differences in drug metabolism in women who are premenopausal versus postmenopausal.216

Clients receiving home health care are at increased risk for medication errors such as uncontrolled hypertension despite medication, confusion or falls while on psychotropic medications, or improper use of medications deemed dangerous to the older adult such as muscle relaxants. Nearly one third of home health clients are misusing their medications as well.217

Potential Drug Side Effects: Side effects are usually defined as predictable pharmacologic effects that occur within therapeutic dose ranges and are undesirable in the given therapeutic situation. Doctors are well aware that drugs have side effects. They may even fully expect their patients to experience some of these side effects. The goal is to obtain maximum benefit from the drug’s actions with the minimum amount of side effects. These are referred to as “tolerable” side effects.

The most common side effects of medications are constipation or diarrhea, nausea, abdominal pain, and sedation. More severe reactions include confusion, drowsiness, weakness, and loss of coordination. Adverse events, such as falls, anorexia, fatigue, cognitive impairment, urinary incontinence, and constipation, can occur.55

Medications can mask signs and symptoms or produce signs and symptoms that are seemingly unrelated to the client’s current medical problem. For example, long-term use of steroids resulting in side effects, such as proximal muscle weakness, tissue edema, and increased pain threshold, may alter objective findings during the examination of the client.

A detailed description of GI disturbances and other side effects caused by nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) resulting in back, shoulder, or scapular pain is presented in Chapter 8. Every therapist should be very familiar with these.

Physiologic or biologic differences can result in different responses and side effects to drugs. Race, age, weight, metabolism, and for women, the menstrual cycle can impact drug metabolism and effects. In the aging population, drug side effects can occur even with low doses that usually produce no side effects in younger populations. Older people, especially those who are taking multiple drugs, are two or three times more likely than young to middle-aged adults to have adverse drug events.

Seventy-five percent of all older clients take OTC medications that may cause confusion, cause or contribute to additional symptoms, and interact with other medications. Sometimes the client is receiving the same drug under different brand names, increasing the likelihood of drug-induced confusion. Watch for the four Ds associated with OTC drug use:

Because many older people do not consider these “drugs” worth mentioning (i.e., OTC drugs “don’t count”), it is important to ask specifically about OTC drug use. Additionally, alcoholism and other drug abuse are more common in older people than is generally recognized, especially in depressed clients. Screening for substance use in conjunction with medication use and/or prescription drug abuse may be important for some clients.

Common medications in the clinic that produce other signs and symptoms include:

• Skin reactions, noninflammatory joint pain (antibiotics; see Fig. 4-12)

• Muscle weakness/cramping (diuretics)

• Muscle hyperactivity (caffeine and medications with caffeine)

• Back and/or shoulder pain (NSAIDs; retroperitoneal bleeding)

• Hip pain from femoral head necrosis (corticosteroids)

• Gait disturbances (Thorazine/tranquilizers)

• Movement disorders (anticholinergics, antipsychotics, antidepressants)

• Hormonal contraceptives (elevated blood pressure)

• Gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, indigestion, abdominal pain, melena)

This is just a partial listing, but it gives an idea why paying attention to medications and potential side effects is important in the screening process. Not all, but some, medications (e.g., antibiotics, antihypertensives, antidepressants) must be taken as prescribed in order to obtain pharmacologic efficacy.

Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs): NSAIDs are a group of drugs that are useful in the symptomatic treatment of inflammation; some appear to be more useful as analgesics. OTC NSAIDs are listed in Table 8-3. NSAIDs are commonly used postoperatively for discomfort; for painful musculoskeletal conditions, especially among the older adult population; and in the treatment of inflammatory rheumatic diseases.

The incidence of adverse reactions to NSAIDs is low—complications develop in about 2% to 4% of NSAID users each year.218 However, 30 to 40 million Americans are regular users of NSAIDs. The widespread use of readily available OTC NSAIDs results in a large number of people being affected. It is estimated that approximately 80% of outpatient orthopedic clients are taking NSAIDs. Many are taking dual NSAIDs (combination of NSAIDs and aspirin) or duplicate NSAIDs (two or more agents from the same class).219

Side Effects of NSAIDs: NSAIDs have a tendency to produce adverse effects on multiple-organ systems, with the greatest damage to the GI tract.220 GI impairment can be seen as subclinical erosions of the mucosa or more seriously, as ulceration with life-threatening bleeding and perforation. People with NSAID-induced GI impairment can be asymptomatic until the condition is advanced. NSAID-related gastropathy causes thousands of hospitalizations and deaths annually.

For those who are symptomatic, the most common side effects of NSAIDs are stomach upset and pain, possibly leading to ulceration. GI ulceration has been reported in up to 30% of adults using NSAIDS.221 With the use of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors, serious GI side effects have modified this figure down to 4% of chronic NSAID users.222 Physical therapists are seeing a large percentage of people taking NSAIDs routinely and are likely to be the first to identify a problem. NSAID use among surgical patients can cause postoperative complications such as wound hematoma, upper GI tract bleeding, hypotension, and impaired bone or tendon healing.223

NSAIDs are also potent renal vasoconstrictors and may cause increased blood pressure and peripheral edema. Clients with hypertension or congestive heart failure are at risk for renal complications, especially those using diuretics or angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors.224 NSAID use may be associated with confusion and memory loss in the older adult.

People with coronary artery disease taking NSAIDs may also be at a slightly increased risk for a myocardial event during times of increased myocardial oxygen demand (e.g., exercise, fever).

Older adults taking NSAIDs and antihypertensive agents must be monitored carefully. Regardless of the NSAID chosen, it is important to check blood pressure when exercise is initiated and periodically afterwards.

Screening for Risk Factors and Effects of NSAIDs: Screening for risk factors is as important as looking for clinical manifestations of NSAID-induced complications. High-risk individuals are older with a history of ulcers and any coexisting diseases that increase the potential for GI bleeding. Anyone receiving treatment with multiple NSAIDs is at increased risk, especially if the dosage is high and/or includes aspirin.

As with any risk-factor assessment, we must know what to look for before we can recognize signs of impending trouble. In the case of NSAID use, back and/or shoulder pain can be the first symptom of impairment in its clinical presentation.

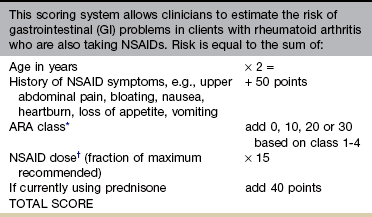

Any client with this presentation in the presence of the risk factors listed in Box 2-13 raises a red flag of suspicion.225 Look for the presence of associated GI distress such as indigestion, heartburn, nausea, unexplained chronic fatigue, and/or melena (tarry, sticky, black or dark stools from oxidized blood in the GI tract) (Case Example 2-10). A scoring system to estimate the risk of GI problems in clients with rheumatoid arthritis who are also taking NSAIDs is presented in Table 2-6 (Case Example 2-11).

TABLE 2-6

Is Your Client at Risk for NSAID-Induced Gastropathy?

ARA Criteria for Classification of Functional Status in Rheumatoid Arthritis:

Class 1 Completely able to perform usual ADLs (self-care, vocational, avocational)

Class 2 Able to perform usual self-care and vocational activities, but limited in avocational activities

Class 3 Able to perform usual self-care activities, but limited in vocational and avocational activities

Class 4 Limited in ability to perform usual self-care, vocational, and avocational activities

For example, the value 1.03 indicates the client is taking 103% of the manufacturer’s highest recommended dose. Most often, clients are taking the highest dose recommended. They receive a 1.0. Anyone taking less will have a fraction percentage less than 1.0. Anyone taking more than the highest dose recommended will have a fraction percentage greater than 1.0. See Case Example 2-11.

Risk Calculation: To determine the risk (%) of hospitalization or death caused by GI complications over the next 12 months, use the TOTAL SCORE in the following formula:

Risk %/year = [TOTAL SCORE − 100] ÷ 40

Risk percentage is the likelihood of a GI event leading to hospitalization or death over the next 12 months for the person with rheumatoid arthritis on NSAIDs. Higher Total Scores yield greater predictive risk. The risk ranges from 0.0 (low risk) to 5.0 (high risk).

†NSAID dose used in this formulation is the fraction of the manufacturer’s highest recommended dose. The manufacturer’s highest recommended dose on the package insert is given a value of 1.00. The dose of each individual is then normalized to this dose.

*American Rheumatism Association (ARA) FUNCTIONAL CLASS

+0 points for class 1 (normal)

+10 points for ARA class 2 (adequate)

Data from Fries JF, Williams CA, Bloch DA, et al: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-associated gastropathy: incidence and risk factor models, Amer J Med 91(3):213-222, 1991.

Correlate increased musculoskeletal symptoms after taking medications. Expect to see a decrease (not an increase) in painful symptoms after taking analgesics or NSAIDs. Ask about any change in pain or symptoms (increase or decrease) after eating (anywhere from 30 minutes to 2 hours later).

Ingestion of food should have no effect on the musculoskeletal tissues, so any change in symptoms that can be consistently linked with food raises a red flag, especially for the client with known GI problems or taking NSAIDs.

The peak effect for NSAIDs when used as an analgesic varies from product to product. For example, peak analgesic effect of aspirin is 2 hours, whereas the peak for naproxen sodium (Aleve) is 2 to 4 hours (compared to acetaminophen, which peaks in 30 to 60 minutes). Therefore the symptoms may occur at varying lengths of time after ingestion of food or drink. It is best to find out the peak time for each antiinflammatory taken by the client and note if maximal relief of symptoms occurs in association with that time.

The time to impact underlying tissue impairment also varies by individual and severity of impairment. There is a big difference between 220 mg (OTC) and 500 mg (by prescription) of naproxen sodium. For example, 220 mg may appear to “do nothing” in the client’s subjective assessment (opinion) after a week’s dosing.

What most adults do not know is that it takes more than 24 to 48 hours to build up a high enough level in the body to impact inflammatory symptoms. The person may start adding more drugs before an effective level has been reached in the body. Five hundred milligrams (500 mg) can impact tissue in a shorter time, especially with an acute event or flare-up; this is one reason why doctors sometimes dispense prescription NSAIDs instead of just using the lower dosage OTC drugs.

Older adults taking NSAIDs and antihypertensive agents must be monitored carefully. Regardless of the NSAID chosen, it is important to check blood pressure when exercise is initiated and periodically afterwards.

Ask about muscle weakness, unusual fatigue, restless legs syndrome, polyuria, nocturia, or pruritus (signs and symptoms of renal failure). Watch for increased blood pressure and peripheral edema (perform a visual inspection of the feet and ankles). Document and report any significant findings.

Women who take nonaspirin NSAIDs or acetaminophen (Tylenol) are twice as likely to develop high blood pressure. This refers to chronic use (more than 22 days/month). There is not a proven cause-effect relationship, but a statistical link exists between the two.226

Acetaminophen: Acetaminophen, the active ingredient in Tylenol and other OTC and prescription pain relievers and cold medicines, is an analgesic (pain reliever) and antipyretic (fever reducer) but not an antiinflammatory agent. Acetaminophen is effective in the treatment of mild-to-moderate pain and is generally well tolerated by all age groups.

It is the analgesic least likely to cause GI bleeding, but taken in large doses over time, it can cause liver toxicity, especially when used with vitamin C or alcohol. Women are more quickly affected than men at lower levels of alcohol consumption.

Individuals at increased risk for problems associated with using acetaminophen are those with a history of alcohol use/abuse, anyone with a history of liver disease (e.g., cirrhosis, hepatitis), and anyone who has attempted suicide using an overdose of this medication.227

Some medications (e.g., phenytoin, isoniazid) taken in conjunction with acetaminophen can trigger liver toxicity. The effects of oral anticoagulants may be potentiated by chronic ingestion of large doses of acetaminophen.228

Clients with acetaminophen toxicity may be asymptomatic or have anorexia, mild nausea, and vomiting. The therapist may ask about right upper abdominal quadrant tenderness, jaundice, and other signs and symptoms of liver impairment (e.g., liver palms, asterixis, carpal tunnel syndrome, spider angiomas); see discussion in Chapter 9.

Corticosteroids: Corticosteroids are often confused with the singular word “steroids.” There are three types or classes of steroids:

1. Anabolic-androgenic steroids such as testosterone, estrogen, and progesterone

2. Mineralocorticoids responsible for maintaining body electrolytes

3. Glucocorticoids, which suppress inflammatory processes within the body

All three types are naturally occurring hormones produced by the adrenal cortex; synthetic equivalents can be prescribed as medication. Illegal use of a synthetic derivative of testosterone is a concern with athletes and millions of men and women who use these drugs to gain muscle and lose body fat.229

Corticosteroids used to control pain and reduce inflammation are associated with significant side effects even when given for a short time. Administration may be by local injection (e.g., into a joint), transdermal (skin patch), or systemic (inhalers or pill form).

Side effects of local injection (catabolic glucocorticoids) may include soft tissue atrophy, changes in skin pigmentation, accelerated joint destruction, and tendon rupture, but it poses no problem with liver, kidney, or cardiovascular function. Transdermal corticosteroids have similar side effects. The incidence of skin-related changes is slightly higher than with local injection, whereas the incidence of joint problems is slightly lower.

Systemic corticosteroids are associated with GI problems, psychologic problems, and hip avascular necrosis. Physician referral is required for marked loss of hip motion and referred pain to the groin in a client on long-term systemic corticosteroids.

Long-term use can lead to immunosuppression, osteoporosis, and other endocrine-metabolic abnormalities. Therapists working with athletes may need to screen for nonmedical (illegal) use of anabolic steroids. Visually observe for signs and symptoms associated with anabolic steroid use. Monitor behavior and blood pressure.

Opioids: Opioids, such as codeine, morphine, tramadol, hydrocodone, or oxycodone, are safe when used as directed. They do not cause kidney, liver, or stomach impairments and have few drug interactions. Side effects can include nausea, constipation, and dry mouth. The client may also experience impaired balance and drowsiness or dizziness, which can increase the risk of falls.

Addiction (physical or psychologic dependence) is often a concern raised by clients and family members alike. Addiction to opioids is uncommon in individuals with no history of substance abuse. Adults over age 60 are often good candidates for use of opioid medications. They obtain greater pain control with lower doses and develop less tolerance than younger adults.230

Prescription Drug Abuse: The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration has reported that more than 7 million Americans abuse prescription medications.231 The CDC reports drug overdose of opioids are now the second leading cause of accidental death in the United States (second only to motor vehicle accidents). Opioid misuse and dependence among prescription opioid patients in the United States is likely higher than currently documented.232 Medical and nonmedical prescription drug abuse has become an increasing problem, especially among young adolescents and teenagers.233

Oxycodone, hydrocodone, methadone, benzodiazepines, and muscle relaxants used to treat pain and anxiety and stimulants used to treat learning disorders are listed as the most common medications involved in nonmedical use.234,235 Prescription opioids are monitored carefully and withdrawn or stopped gradually to avoid withdrawal symptoms. Psychologic dependence tends to occur when opioids are used in excessive amounts and often does not develop until after the expected time for pain relief has passed.

Risk factors for prescription drug abuse and nonmedical use of prescription drugs include age under 65, previous history of opioid abuse, major depression, and psychotropic medication use.232 Teen users raiding the family medicine cabinet for prescription medications (a practice referred to as “pharming”) often find a wide range of mood stabilizers, painkillers, muscle relaxants, sedatives, and tranquilizers right within their own homes. Combining medications and/or combining prescription medicines with alcohol can lead to serious drug-drug interactions.231

Hormonal Contraceptives: Some women use birth control pills to prevent pregnancy while others take them to control their menstrual cycle and/or manage premenstrual and menstrual symptoms, including excessive and painful bleeding.

Originally, birth control pills contained as much as 20% more estrogen than the amount present in the low-dose, third-generation oral contraceptives available today. Women taking the newer hormonal contraceptives (whether in pill, injectable, or patch form) have a slightly increased risk of high blood pressure, which returns to normal shortly after the hormone is discontinued.

Age over 35, smoking, hypertension, obesity, bleeding disorders, major surgery with prolonged immobilization, and diabetes are risk factors for blood clots (venous thromboembolism, not arterial), heart attacks, and strokes in women taking hormonal contraceptives.236 Adolescents using the injectable contraceptive Depo-Provera (DMPA) are at risk for bone loss.237

Anyone taking hormonal contraception of any kind, but especially premenopausal cardiac clients, must be monitored by taking vital signs, especially blood pressure, during physical activity and exercise. Assessing for risk factors is an important part of the plan of care for this group of individuals.

Any woman on combined oral contraceptives (estrogen and progesterone) reporting break-through bleeding should be advised to see her doctor.

Antibiotics: Skin reactions (see Fig. 4-12) and noninflammatory joint pain (see Box 3-4) are two of the most common side effects of antibiotics seen in a therapist’s practice. Often these symptoms are delayed and occur up to 6 weeks after the client has finished taking the drug.

Fluoroquinolones, a class of antibiotics used to treat bacterial infections (e.g., urinary tract; upper respiratory tract; infectious diarrhea; gynecologic infections; and skin, soft tissue, bone and joint infections) are known to cause tendinopathies ranging from tendinitis to tendon rupture.

Commonly prescribed fluoroquinolones include ciprofloxacin (Cipro), ciprofloxacin extended release (Cipro ER, Proquin XR), gemifloxacin (Factive), levofloxacin (Levaquin), norfloxacin (Noroxin), ofloxacin (Floxin), and moxifloxacin (Avelox). Although tendon injury has been reported with most fluoroquinolones, most of the fluoroquinolone-induced tendinopathies of the Achilles tendon are due to ciprofloxacin.

The incidence of this adverse event has been enough that in 2008, the U.S. FDA required makers of fluoroquinolone antimicrobial drugs for systemic use to add a boxed warning to the prescribing information about the increased risk of developing tendinitis and tendon rupture. At the same time, the FDA issued a notice to health care professionals about this risk, the known risk factors, and what to advise anyone taking these medications who report tendon pain, swelling, or inflammation (i.e., stop taking the fluoroquinolone, avoid exercise and use of the affected area, promptly contact the prescribing physician).238

The concomitant use of corticosteroids and fluoroquinolones in older adults (over age 60) are the major risk factors for developing musculoskeletal toxicities.239,240 Other risk factors include organ transplant (kidney, heart, and lung) recipients and previous history of tendon ruptures or other tendon problems.

Other common side effects include depression, headache, convulsions, fatigue, GI disturbance (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea), arthralgia (joint pain, inflammation, and stiffness), and neck, back, or chest pain. Symptoms may occur as early as 2 hours after the first dose and as late as 6 months after treatment has ended241 (Case Example 2-12).

Nutraceuticals: Nutraceuticals are natural products (usually made from plant substances) that do not require a prescription to purchase. They are often sold at health food stores, nutrition or vitamin stores, through private distributors, or on the Internet. Nutraceuticals consist of herbs, vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, and other natural supplements.

The use of herbal and other supplements has increased dramatically in the last decade. Exposure to individual herbal ingredients may continue to rise as more of them are added to mainstream multivitamin products and advertised as cancer and chronic disease preventatives.242

These products may be produced with all natural ingredients, but this does not mean they do not cause problems, complications, and side effects. When combined with certain food items or taken with some prescription drugs, nutraceuticals can have potentially serious complications.

Herbal and home remedies may be used by clients based on their ethnic, spiritual, or cultural orientation. Alternative healers may be consulted for all kinds of conditions from diabetes to depression to cancer. Home remedies and nutraceuticals can be harmful when combined with some medications.

The therapist should ask clients about and document their use of nutraceuticals and dietary supplements. In a survey of surgical patients, more than one in three adults had taken an herb that had effects on coagulation, blood pressure, cardiovascular function, sedation, and electrolytes or diuresis within 2 weeks of the scheduled surgery. As many as 70% of these individuals failed to disclose this use during the preoperative assessment.243

A pharmacist can help in comparing signs and symptoms present with possible side effects and drug-drug or drug-nutraceutical interactions. Mayo Clinic offers a list of herbal supplements that should not be taken in combination with certain types of medications (www.mayoclinic.com; type the words: herbal supplements in the search window). Other resources are available as well.244

The Physical Therapist’s Role: For every client the therapist is strongly encouraged to take the time to look up indications for use and possible side effects of prescribed medications. Drug reference guidebooks that are updated and published every year are available in hospital and clinic libraries or pharmacies. Pharmacists are also invaluable sources of drug information. Websites with useful drug information are included in the next section (see Resources).

Distinguishing drug-related signs and symptoms from disease-related symptoms may require careful observation and consultation with family members or other health professionals to see whether these signs tend to increase following each dose.245 This information may come to light by asking the question:

Because clients are more likely now than ever before to change physicians or practitioners during an episode of care, the therapist has an important role in education and screening. The therapist can alert individuals to watch for any red flags in their drug regimen. Clients with both hypertension and a condition requiring NSAID therapy should be closely monitored and advised to make sure the prescribing practitioner is aware of both conditions.

The therapist may find it necessary to reeducate the client regarding the importance of taking medications as prescribed, whether on a daily or other regular basis. In the case of antihypertensive medication, the therapist should ask whether the client has taken the medication today as prescribed.

It is not unusual to hear a client report, “I take my blood pressure pills when I feel my heart starting to pound.” The same situation may occur with clients taking antiinflammatory drugs, antibiotics, or any other medications that must be taken consistently for a specified period to be effective. Always ask the client if he or she is taking the prescription every day or just as needed. Make sure this is with the physician’s knowledge and approval.

Clients may be taking medications that were not prescribed for them, taking medications inappropriately, or not taking prescribed medications without notifying the doctor.

Appropriate FUPs include the following:

Many people who take prescribed medications cannot recall the name of the drug or tell you why they are taking it. It is essential to know whether the client has taken OTC or prescription medication before the physical therapy examination or intervention because the symptomatic relief or possible side effects may alter the objective findings.

Similarly, when appropriate, treatment can be scheduled to correspond with the time of day when clients obtain maximal relief from their medications. Finally, the therapist may be the first one to recognize a problem with medication or dosage. Bringing this to the attention of the doctor is a valuable service to the client.

Resources: Many resources are available to help the therapist identify potential side effects of medications, especially in the presence of polypharmacy or hyperpharmacotherapy with the possibility of drug interactions.

Find a local pharmacist willing to answer questions about medications. The pharmacist can let the therapist know when associated signs and symptoms may be drug-related. Always bring this to the physician’s attention. It may be that the “burden of tolerable side effects” is worth the benefit, but often, the dosage can be adjusted or an alternative drug can be tried.

Several favorite resources include Mosby’s Nursing Drug Handbook, published each year by Elsevier Science (Mosby, St. Louis), The People’s Pharmacy Guide to Home and Herbal Remedies,246 PDR for Herbal Medicines ed 4,247 and Pharmacology in Rehabilitation.245

A helpful general guide regarding potentially inappropriate medications for older adults called the Beers’ list has been published and revised. This list along with detailed information about each class of drug is available online at: www.dcri.duke.edu/ccge/curtis/beers.html.

Easy-to-use websites for helpful pharmacologic information include:

• MedicineNet (www.medicinenet.com)

• University of Montana Drug Information Service (DIS) (www.umt.edu/druginfo or by phone: 1-800-501-5491)[our personal favorite—an excellent resource]

• RxList: The Internet Drug Index (www.rxlist.com)

• DrugDigest (www.drugdigest.com)

• National Council on Patient Information and Education: BeMedWise. Advice on use of OTC medications. Available at www.bemedwise.org.

Current Level of Fitness

An assessment of current physical activity and level of fitness (or level just before the onset of the current problem) can provide additional necessary information relating to the origin of the client’s symptom complex.

The level of fitness can be a valuable indicator of potential response to treatment based on the client’s motivation (i.e., those who are more physically active and healthy seem to be more motivated to return to that level of fitness through disciplined self-rehabilitation).

It is important to know what type of exercise or sports activity the client participates in, the number of times per week (frequency) that this activity is performed, the length (duration) of each exercise or sports session, as well as how long the client has been exercising (weeks, months, years), and the level of difficulty of each exercise session (intensity). It is very important to ask:

The client should give a description of these activities, including how physical activities have been affected by the symptoms. Follow-up questions include:

If the Family/Personal History form is not used, it may be helpful to ask some of the questions shown in Fig. 2-2: Work/Living Environment or History of Falls. For example, assessing the history of falls with older people is essential. One third of community-dwelling older adults and a higher proportion of institutionalized older people fall annually. Aside from the serious injuries that may result, a debilitating “fear of falling” may cause many older adults to reduce their activity level and restrict their social life. This is one area that is often treatable and even preventable with physical therapy.

Older persons who are in bed for prolonged periods are at risk for secondary complications, including pressure ulcers, urinary tract infections, pulmonary infections and/or infarcts, congestive heart failure, osteoporosis, and compression fractures. See previous discussion in this chapter on History of Falls for more information.

Sleep-Related History

Sleep patterns are valuable indicators of underlying physiologic and psychologic disease processes. The primary function of sleep is believed to be the restoration of body function. When the quality of this restorative sleep is decreased, the body and mind cannot perform at optimal levels.

Physical problems that result in pain, increased urination, shortness of breath, changes in body temperature, perspiration, or side effects of medications are just a few causes of sleep disruption. Any factor precipitating sleep deprivation can contribute to an increase in the frequency, intensity, or duration of a client’s symptoms.

For example, fevers and sweats are characteristic signs of systemic disease. Sweats occur as a result of a gradual increase in body temperature followed by a sudden drop in temperature; although they are most noticeable at night, sweats can occur anytime of the day or night. This change in body temperature can be related to pathologic changes in immunologic, neurologic, or endocrine function.

Be aware that many people, especially women, experience sweats associated with menopause, poor room ventilation, or too many clothes and covers used at night. Sweats can also occur in the neutropenic client after chemotherapy or as a side effect of other medications such as some antidepressants, sedatives or tranquilizers, and some analgesics.

Anyone reporting sweats of a systemic origin must be asked if the same phenomenon occurs during the waking hours. Sweats (present day and/or night) can be associated with medical problems such as tuberculosis, autoimmune diseases, and malignancies.248

An isolated experience of sweats is not as significant as intermittent but consistent sweats in the presence of risk factors for any of these conditions or in the presence of other constitutional symptoms (see Box 1-3). Assess vital signs in the client reporting sweats, especially when other symptoms are present and/or the client reports back or shoulder pain of unknown cause.

Certain neurologic lesions may produce local changes in sweating associated with nerve distribution. For example, a client with a spinal cord tumor may report changes in skin temperature above and below the level of the tumor. At presentation, any client with a history of either sweats or fevers should be referred to the primary physician. This is especially true for clients with back pain or multiple joint pain without traumatic origin.

Pain at night is usually perceived as being more intense because of the lack of outside distraction when the person lies quietly without activity. The sudden quiet surroundings and lack of external activity create an increased perception of pain that is a major disrupter of sleep.

It is very important to ask the client about pain during the night. Is the person able to get to sleep? If not, the pain may be a primary focus and may become continuously intense so that falling asleep is a problem.

If a change in position can increase or decrease the level of pain, it is likely to be a musculoskeletal problem. If, however, the client is awakened from a deep sleep by pain in any location that is unrelated to physical trauma and is unaffected by a change in position, this may be an ominous sign of serious systemic disease, particularly cancer. FUPs include:

Many other factors (primarily environmental and psychologic) are associated with sleep disturbance, but a good, basic assessment of the main characteristics of physically related disturbances in sleep pattern can provide valuable information related to treatment or referral decisions. The McGill Home Recording Card (see Fig. 3-7) is a helpful tool for evaluating sleep patterns.

Stress (see also Chapter 3)

By using the interviewing tools and techniques described in this chapter, the therapist can communicate a willingness to consider all aspects of illness, whether biologic or psychologic. Client self-disclosure is unlikely if there is no trust in the health professional, if there is fear of a lack of confidentiality, or if a sense of disinterest is noted.

Most symptoms (pain included) are aggravated by unresolved emotional or psychologic stress. Prolonged stress may gradually lead to physiologic changes. Stress may result in depression, anxiety disorders, and behavioral consequences (e.g., smoking, alcohol and substance abuse, accident proneness).

The effects of emotional stress may be increased by physiologic changes brought on by the use of medications or poor diet and health habits (e.g., cigarette smoking or ingestion of caffeine in any form). As part of the Core Interview, the therapist may assess the client’s subjective report of stress by asking:

Emotions, such as fear and anxiety, are common reactions to illness and treatment intervention and may increase the client’s awareness of pain and symptoms. These emotions may cause autonomic (branch of nervous system not subject to voluntary control) distress manifested in such symptoms as pallor, restlessness, muscular tension, perspiration, stomach pain, diarrhea or constipation, or headaches.

It may be helpful to screen for anxiety-provoked hyperventilation by asking:

After the objective evaluation has been completed, the therapist can often provide some relief of emotionally amplified symptoms by explaining the cause of pain, outlining a plan of care, and providing a realistic prognosis for improvement. This may not be possible if the client demonstrates signs of hysterical symptoms or conversion symptoms (see discussion in Chapter 3).

Whether the client’s symptoms are systemic or caused by an emotional/psychologic overlay, if the client does not respond to treatment, it may be necessary to notify the physician that there is not a satisfactory explanation for the client’s complaints. Further medical evaluation may be indicated at that time.

Final Questions

It is always a good idea to finalize the interview by reviewing the findings and paraphrasing what the client has reported. Use the answers from the Core Interview to recall specifics about the location, frequency, intensity, and duration of the symptoms. Mention what makes it better or worse.

Recap the medical and surgical history including current illnesses, diseases, or other medical conditions; recent or past surgeries; recent or current medications; recent infections; and anything else of importance brought out by the interview process.

It is always appropriate to end the interview with a few final questions such as:

If you have not asked any questions about assault or partner abuse, this may be the appropriate time to screen for domestic violence.

Special Questions for Women

Gynecologic disorders can refer pain to the low back, hip, pelvis, groin, or sacroiliac joint Any woman having pain or symptoms in any one or more of these areas should be screened for possible systemic diseases. The need to screen for systemic disease is essential when there is no known cause of the pain or symptoms.

Any woman with a positive family/personal history of cancer should be screened for medical disease even if the current symptoms can be attributed to a known NMS cause.

Chapter 14 has a list of special questions to ask women (see also Appendix B-37). The therapist will not need to ask every woman each question listed but should take into consideration the data from the Family/Personal History form, Core Interview, and clinical presentation when choosing appropriate FUPs.

Special Questions for Men

Men describing symptoms related to the groin, low back, hip, or sacroiliac joint may have prostate or urologic involvement. A positive response to any or all of the questions in Appendix B-24 must be evaluated further. Answers to these questions correlated with family history, the presence of risk factors, clinical presentation, and any red flags will guide the therapist in making a decision regarding treatment versus referral.

Hospital Inpatient Information

Treatment of hospital inpatients or residents in other facilities (e.g., step down units, transition units, extended care facilities) requires a slightly different interview (or information-gathering) format. A careful review of the medical record for information will assist the therapist in developing a safe and effective plan of care. Watch for conflicting reports (e.g., emergency department, history and physical, consult reports). Important information to look for might include:

An evaluation of the patient’s medical status in conjunction with age and diagnosis can provide valuable guidelines for the plan of care.

If the patient has had recent surgery, the physician’s report should be scanned for preoperative and postoperative orders (in some cases there is a separate physician’s orders book or link to click on if the medical records are in an electronic format). Read the operative report whenever available. Look for any of the following information:

• Was the patient treated preoperatively with physical therapy for gait, strength, range of motion, or other objective assessments?

• Were there any unrelated preoperative conditions?

• Was the surgery invasive, a closed procedure via arthroscopy, fluoroscopy, or other means of imaging, or virtual by means of computerized technology?

• How long was the operative procedure?

• How much fluid and/or blood products were given?

• What position was the patient placed in during the procedure?

Fluid received during surgery may affect arterial oxygenation, leaving the person breathless with minimal exertion and experiencing early muscle fatigue. Prolonged time in any one position can result in residual musculoskeletal complaints.

The surgical position for men and for women during laparoscopy (examination of the peritoneal cavity) may place patients at increased risk for thrombophlebitis because of the decreased blood flow to the legs during surgery.

Other valuable information that may be contained in the physician’s report may include:

• What are the current short-term and long-term medical treatment plans?

• Are there any known or listed contraindications to physical therapy intervention?

Associated or additional problems to the primary diagnosis may be found within the record (e.g., diabetes, heart disease, peripheral vascular disease, respiratory involvement). The physical therapist should look for any of these conditions in order to modify exercise accordingly and to watch for any related signs and symptoms that might affect the exercise program:

• Are there complaints of any kind that may affect exercise (e.g., shortness of breath [dyspnea], heart palpitations, rapid heart rate [tachycardia], fatigue, fever, or anemia)?

If the patient has diabetes, the therapist should ask:

Avoiding peak insulin levels in planning exercise schedules is discussed more completely in Chapter 11. Other questions related to medications can follow the Core Interview outline with appropriate follow-up questions:

• Is the patient receiving oxygen or receiving fluids/medications through an intravenous line?

• If the patient is receiving oxygen, will he or she need increased oxygen levels before, during, or following physical therapy? What level(s)? Does the patient have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) with restrictions on oxygen use?

• Are there any dietary or fluid restrictions?

• If so, check with the nursing staff to determine the full limitations. For example:

• Are ice chips or wet washcloths permissible?

• How many ounces or milliliters of fluid are allowed during therapy?

Laboratory values and vital signs should be reviewed. For example:

Anemic patients may demonstrate an increased normal resting pulse rate that should be monitored during exercise. Patients with unstable blood pressure may require initial standing with a tilt table or monitoring of the blood pressure before, during, and after treatment. Check the nursing record for pulse rate at rest and blood pressure to use as a guide when taking vital signs in the clinic or at the patient’s bedside.

Nursing Assessment

After reading the patient’s chart, check with the nursing staff to determine the nursing assessment of the individual patient. The essential components of the nursing assessment that are of value to the therapist may include:

The nursing staff are usually intimately aware of the patient’s current medical and physical status. If pain is a factor:

Pain tolerance is relative to the medications received by the patient, the number of days after surgery or after injury, fatigue, previous history of substance abuse or chemical addiction, and the patient’s personality.

To assess the patient’s physical status, ask the nursing staff or check the medical record to find out:

• Has the patient been up at all yet?

• If yes, how long has the patient been sitting, standing, or walking?

Ask about the patient’s orientation:

In other words, does the patient know the date and the approximate time, where he or she is, and who he or she is? Treatment plans may be altered by the patient’s awareness; for example, a home program may be impossible without family compliance.

• Are there any known or expected discharge plans?

• If yes, what are these plans and when is the target date for discharge?

Cooperation between nurses and therapists is an important part of the multidisciplinary approach in planning the patient’s plan of care. The questions to ask and factors to consider provide the therapist with the basic information needed to carry out an objective examination and to plan the intervention. Each individual patient’s situation may require that the therapist obtain additional pertinent information (Box 2-14).

Physician Referral

The therapist will be using the questions presented in this chapter to identify symptoms of possible systemic origin. The therapist can screen for medical disease and decide if referral to the physician (or other appropriate health care professional) is indicated by correlating the client’s answers with family/personal history, vital signs, and objective findings from the physical examination.

For example, consider the client with a chief complaint of back pain who circles “yes” on the Family/Personal History form, indicating a history of ulcers or stomach problems. Obtaining further information at the first appointment by using Special Questions to Ask is necessary so that a decision regarding treatment or referral can be made immediately.

This treatment-versus-referral decision is further clarified as the interview, and other objective evaluation procedures continue. Thus, if further questioning fails to show any association of back pain with GI symptoms and the objective findings from the back evaluation point to a true musculoskeletal lesion, medical referral is unnecessary and the physical therapy intervention can begin.

This information is not designed to make a medical diagnosis but rather to perform an accurate assessment of pain and systemic symptoms that can mimic or occur simultaneously with a musculoskeletal problem.

Guidelines for Physician Referral

As part of the Review of Systems, correlate history with patterns of pain and any unusual findings that may indicate systemic disease. The therapist can use the decision-making tools discussed in Chapter 1 (see Box 1-7) to make a decision regarding treatment versus referral.

Some of the specific indications for physician referral mentioned in this chapter include the following:

• Spontaneous postmenopausal bleeding

• A growing mass, whether painful or painless

• Persistent rise or fall in blood pressure

• Hip, sacroiliac, pelvic, groin, or low back pain in a woman without traumatic etiologic complex who reports fever, sweats, or an association between menses and symptoms

• Marked loss of hip motion and referred pain to the groin in a client on long-term systemic corticosteroids

• A positive family/personal history of breast cancer in a woman with chest, back, or shoulder pain of unknown cause

• Elevated blood pressure in any woman taking birth control pills; this should be closely monitored by her physician

1. What is the effect of NSAIDs (e.g., Naprosyn, Motrin, Anaprox, ibuprofen) on blood pressure?

2. Most of the information needed to determine the cause of symptoms is contained in the:

3. With what final question should you always end your interview?

4. A risk factor for NSAID-related gastropathy is the use of:

5. After interviewing a new client, you summarize what she has told you by saying, “You told me you are here because of right neck and shoulder pain that began 5 years ago as a result of a car accident. You also have a ‘pins and needles’ sensation in your third and fourth fingers but no other symptoms at this time. You have noticed a considerable decrease in your grip strength, and you would like to be able to pick up a pot of coffee without fear of spilling it.”

6. Screening for alcohol use would be appropriate when the client reports a history of accidents.

7. What is the significance of sweats?

8. Spontaneous uterine bleeding after 12 consecutive months without menstrual bleeding requires medical referral.

9. Which of the following are red flags to consider when screening for systemic or viscerogenic causes of neuromuscular and musculoskeletal signs and symptoms:

10. A 52-year-old man with low back pain and sciatica on the left side has been referred to you by his family physician. He has had a discectomy and laminectomy on two separate occasions about 5 to 7 years ago. No imaging studies have been performed (e.g., x-ray examination or MRI) since that time. What follow-up questions should you ask to screen for medical disease?

11. You should assess clients who are receiving NSAIDs for which physiologic effect associated with increased risk of hypertension?

12. Instruct clients with a history of hypertension and arthritis to:

References

1. Barsky, AJ. Forgetting, fabricating, and telescoping: the instability of the medical history. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(9):981–984.

2. A Normative Model of Physical Therapist Professional Education: Version 2004. Alexandria, VA: American Physical Therapy Association, 2004.

3. Davis, CM. Patient practitioner interaction: an experiential manual for developing the art of healthcare, ed 5. Thorofare, NJ: Slack; 2011.

4. Leavitt, RL. Developing cultural competence in a multicultural world, Part II. PT Magazine. 2003;11(1):56–70.

5. National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). Facts and Figures. Available online at http://nces.ed.gov. [Accessed August 27, 2010].

6. The Joint Commission. What did the doctor say? Improving health literacy to protect patient safety. www.jointcommission.org, 2007. [Available online at Accessed Dec. 7, 2010].

7. Marcus, EN. The silent epidemic- the health effects of illiteracy. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(4):339–341.

8. William, H, Mahood, MD, president of the American Medical Association Foundation, the philanthropic arm of the AMA. www.amaassn.org/scipubs/amnews/pick_00/hlse0320.htm.

9. National Adult Literacy Agency (NALA). Resource Room. Available at http://www.nala.ie/. [Accessed July 19, 2010].

10. Nordrum, J, Bonk, E. Serving patients with limited English proficiency. PT Magazine. 2009;17(1):58–60.

11. National Center for Education Statistics. U.S. Department of Education Institute of Education Sciences. Available at http://nces.ed.gov. [Accessed on June 26, 2010].

12. Weiss, BD. Assessing health literacy in clinical practice. Available online at www.medscape.com/viewprogram/8203, 2007. [Accessed March 4, 2010].

13. Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer AM, Kindig DA, eds. Health literacy: A prescription to end confusion. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2004.

14. Magasi, S. Rehabilitation consumers’ use and understanding of quality information: a health literacy perspective. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(2):206–212.

15. Lattanzi JB, Purnell LD, eds. Developing cultural competence in physical therapy practice. Philadelphia: FA Davis, 2005.

16. Spector, RE. Cultural diversity in health and illness, ed 7. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 2008.

17. Berens, LV, et al. Quick guide to the 16 personality types in organizations: understanding personality differences in the workplace. Huntington Beach, CA: Telos Publications; 2002.

18. Nardi, D. Multiple intelligences and personality type. Huntington Beach, CA: Telos Publications; 2001.

19. Cole, SA, Bird, J. The medical interview: The three-function approach, ed 2. St. Louis: Mosby-Year Book; 2000.

20. Coulehan, JL, Block, MR. The medical interview: Mastering skills for clinical practice, ed 5. Philadelphia: FA Davis; 2006.

21. National Council on Interpreting in Health Care. National Standards of Practice for Interpreters in Health Care. www.ncihc.org/mc/page.do?sitePageId=57768&orgId=ncihc, September 2005. [Available online at Accessed Aug. 31, 2010].

22. Assuring cultural competence in health care: Recommendations for national standards and an outcomes-focused research agenda. Office of Minority Health, Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1999.

23. APTA. Advocacy: Minority and international affairs. Available at http://www.apta.org/. [Click on left sided Advocacy menu. Type in research box: Minority Affairs or Cultural Competence. Accessed Oct 29, 2010].

24. U.S. Census Bureau. United States Census 2010. American Fact Finder. U.S. Census Projections. Available www.census.gov/. [Accessed Oct. 1, 2010].

25. Bonder, B, Martin, L, Miracle, A. Culture in clinical care. Clifton Park: Delmar Learning; 2001.

26. Leavitt, RL. Developing cultural competence in a multicultural world, Part I. PT Magazine. 2002;10(12):36–48.