Anatomy of Local Anesthesia

1 Define and pronounce the key terms and anatomic terms in this chapter.

2 List the tissue and structures anesthetized by each type of injection and describe the target areas.

3 Locate and identify the anatomic structures used to determine the local anesthetic needle’s penetration site for each type of injection on a skull and a patient.

4 Demonstrate the correct placement of the local anesthetic needle for each type of injection on a skull and a patient.

5 Identify the tissue penetrated by the local anesthetic needle for each type of injection.

6 Discuss the symptoms and complications of local anesthesia of the oral cavity associated with anatomic considerations for each type of injection.

7 Correctly complete the review questions and activities for this chapter.

8 Integrate an understanding of the anatomy of the trigeminal nerve and associated tissue into the administration of local anesthesia in clinical dental practice.

(in-fil-tray-shun) Type of injection that anesthetizes a small area—one or two teeth and associated structures—when the local anesthetic agent is deposited near terminal nerve endings.

Anatomic Considerations for Local Anesthesia

The management of pain through local anesthesia by dental professionals requires a thorough understanding of the anatomy of the skull, trigeminal nerve, and related structures. This text discusses the anatomic considerations for local anesthesia. Dental professionals will also want to refer to a current text on the administration of local anesthesia in dentistry for more information on actual clinical technique (see Appendix A).

The skull bones involved in local anesthetic administration are the maxilla, palatine bone, and mandible (see Chapter 3). Soft tissue structures of the face and oral cavity may serve the dental professional as initial landmarks to visualize and palpate for local anesthesia (see Chapter 2). However, there are many variations in soft tissue anatomic topography among patients. Thus to increase the reliability of local anesthesia procedures, the dental professional must learn to rely mainly on both visualization and palpation of hard tissue structures as landmarks when injecting patients.

The dental professional must also know the location of certain adjacent soft tissue structures, such as major blood vessels and glandular tissue, so as to avoid inadvertently injecting them (see Chapters 6 and 7). If certain soft tissue structures are accidentally injected with local anesthetic agent, complications may occur. Infections may also be spread to deeper tissue by needle-tract contamination (see Chapter 12).

The fifth cranial or trigeminal nerve provides sensory information for the teeth and associated tissue (see Chapter 8). Thus branches of the trigeminal nerve are anesthetized before most dental procedures. Understanding the location of these nerve branches in relation to facial bones, as well as soft tissue, increases the reliability of each injection.

Two types of local anesthetic injections are used commonly in dentistry: local infiltration and nerve block. The type of injection used for a given dental procedure is determined by the type and length of the procedure.

Local infiltration anesthetizes a small area, including one or two teeth and associated tissue, by injection near their apices. For this type of local anesthetic injection, the local anesthetic agent is deposited near terminal nerve endings. This localized deposition has varying degrees of success depending on the anatomy of the region.

Nerve block affects a larger area than local infiltration and thus, more teeth. With nerve block, the local anesthetic agent is deposited near large nerve trunks. This generalized deposition has a higher degree of success than infiltration. This type of injection is discussed in this chapter.

The proper amount of local anesthetic agent should always be used because there will be possible failure of the anesthesia if too little agent is used. This is commonly noted in the patient who may have large teeth with unusually long roots. The bone surrounding the roots may also be excessively thick in a patient needing more volume of agent.

In addition, it is important to not start the dental treatment before the local anesthetic can take effect. This is a particular problem with injections for mandibular teeth due to the anatomy of the nerve pathway. In addition, when working within the confines of quadrant dentistry, the injections should be administered from posterior to anterior, with the dental treatment commencing in the same directions due to the anatomy of the nerve pathway.

Finally, there must never be an injection directly through an area with an abscess, cellulitis, or osteomyelitis so as to prevent the spread of dental infection (see Chapter 12). Also, the effectiveness of local anesthetic agents is greatly reduced when administered adjacent to areas of infection, so additional amounts may be needed keeping the maximal recommended dosage always in mind for each patient.

Maxillary Nerve Anesthesia

The maxillary nerve and its branches can be anesthetized in a number of ways depending on the tissue requiring local anesthesia (Figure 9-1, Table 9-1). Most local anesthesia of the maxilla is more successful than that of the mandible because the facial plates of bone of the maxillae are less dense than that of the mandible over similar teeth and even lingual anesthesia from the palatal surface is easily accomplished; this can be easily noted with a panoramic radiograph (see Figure 3-46). Less variation exists in the anatomy of the maxillae and palatine bones and associated nerves with respect to local anesthetic landmarks as compared with similar mandibular structures, making the maxillary injections more routine, and usually without the need for any troubleshooting if there is failure of anesthesia (see Chapter 3).

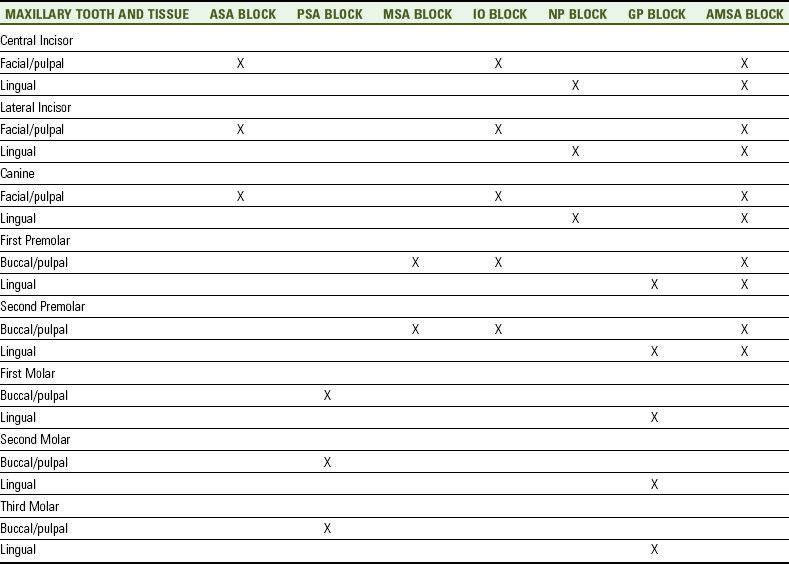

TABLE 9-1

Summary of Maxillary Local Anesthesia of the Teeth and Associated Tissue

The anesthesia is not included for the mesiobuccal root of the first molar nor for anatomic variants.

AMSA, Anterior middle superior alveolar; ASA, anterior superior alveolar; GP, greater palatine; IO, infraorbital; MSA, middle superior alveolar; NP, nasopalatine; PSA, posterior superior alveolar.

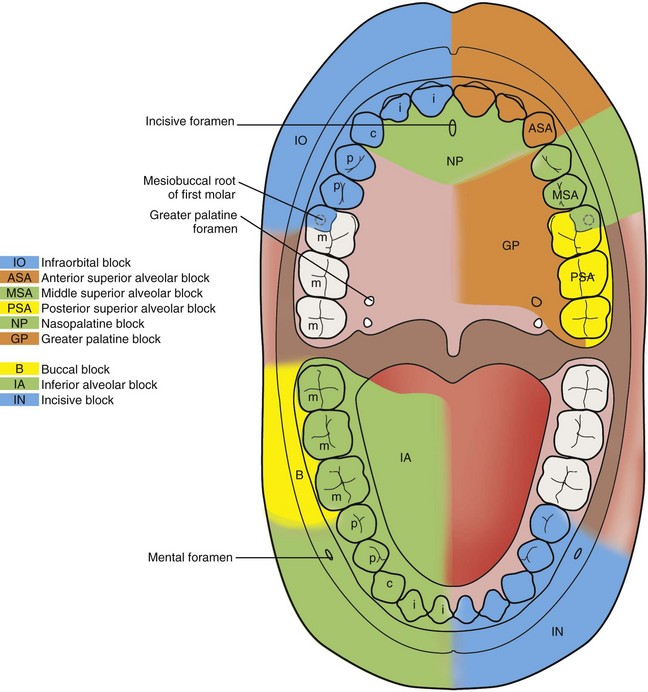

FIGURE 9-1 Local anesthetic blocks with the tissue and structures anesthetized individually highlighted (note that the anterior middle superior alveolar, mental, or Gow-Gates mandibular blocks are not included; see associated figures for clarification of these blocks).

Pulpal anesthesia is achieved through anesthesia of each tooth’s dental branches as they extend into the pulp by way of the apical foramen. Both the hard and soft tissue of the periodontium are anesthetized by way of the interdental and interradicular branches for each tooth.

The posterior superior alveolar block is generally recommended for anesthesia of the maxillary molar teeth and associated buccal tissue in one quadrant. The middle superior alveolar block is generally recommended for anesthesia of the maxillary premolars and associated buccal tissue in one quadrant. The anterior superior alveolar block is recommended for anesthesia of the maxillary canine and incisors and their associated facial tissue in one quadrant. The infraorbital block is generally recommended for anesthesia of the maxillary anterior and premolar teeth and associated facial tissue in one quadrant since it anesthetizes both regions covered by the middle and anterior superior alveolar blocks.

Palatal anesthesia usually involves anesthesia of the soft and hard tissue of the periodontium of the palatal area such as the gingiva, periodontal ligament, and alveolar bone. Palatal anesthesia usually does not provide any pulpal anesthesia to the maxillary teeth or associated facial or buccal tissue. The greater palatine block is generally recommended for anesthesia of the palatal tissue distal to the maxillary canine in one quadrant. The nasopalatine block is generally recommended for anesthesia of the palatal tissue between the maxillary right and left canines.

Separate from these palatal blocks that only provide palatal tissue anesthesia is another block administered on the palate, the anterior middle superior alveolar block. This block is generally recommended for anesthesia of most of the maxillary teeth and their associated tissue in one quadrant, except for those innervated by the posterior superior alveolar nerve. Thus the posterior superior alveolar block can be administered to allow complete anesthetic coverage of the maxillary quadrant.

Posterior Superior Alveolar Block

The posterior superior alveolar block (al-vee-o-lar) or PSA block is used to achieve pulpal anesthesia in the maxillary third, second, and first molars in most patients. Thus the PSA block is indicated when the dental procedure involves two or more maxillary molars or their associated buccal tissue.

However, in some patients the mesiobuccal root of the maxillary first molar is not innervated by the PSA nerve but by the MSA nerve. Therefore a second injection to anesthetize the MSA nerve may be necessary to insure pulpal anesthesia of all the roots of the maxillary first molar.

The PSA block also anesthetizes the buccal periodontium overlying the maxillary third, second, and first molars including the associated gingiva, periodontal ligament, and alveolar bone. If anesthesia of the lingual (or palatal) tissue is desired, the greater palatine block also may be necessary.

Target Area And Injection Site For Psa Block

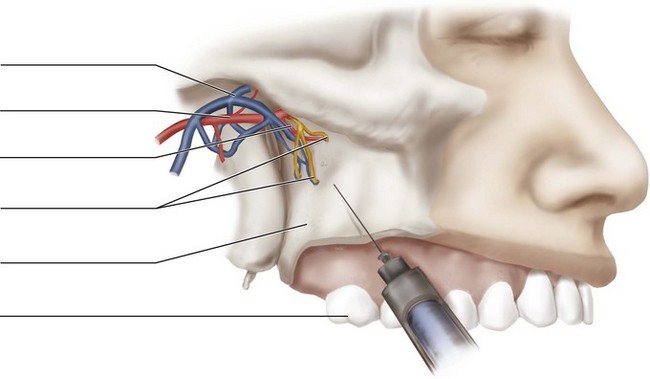

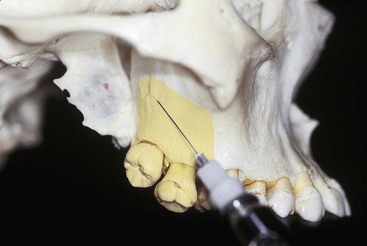

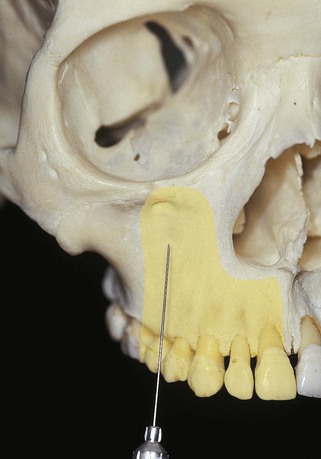

The target area for the PSA block is the PSA nerve as it enters the maxilla through the posterior superior alveolar foramina on the maxilla’s infratemporal surface (Figures 9-2 and 9-3, see Figures 3-47 and 8-13 ). This area is posterosuperior and medial on the maxillary tuberosity. However, intraoral surface landmarks are also used to insure proximity to the target area.

FIGURE 9-2 Target area for the posterior superior alveolar block is the PSA nerve at the posterior superior alveolar foramina on the infratemporal surface of the maxilla, posterosuperior and medial to the maxillary tuberosity, with anesthetized area highlighted.

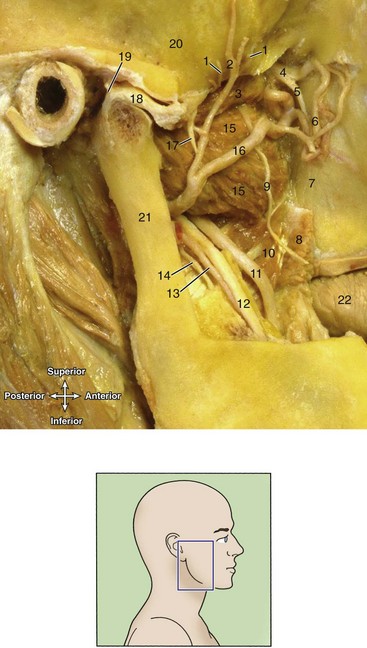

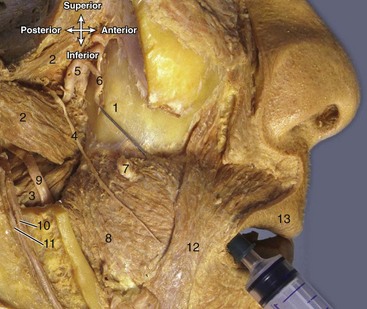

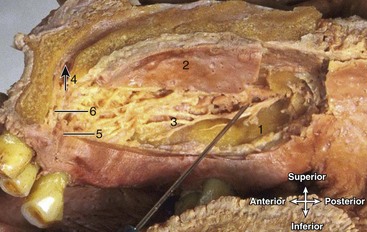

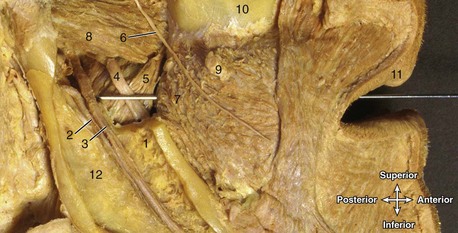

FIGURE 9-3 Dissection of the right infratemporal fossa (inset, note zygomatic arch and mandible have been removed) in target area for the posterior superior alveolar block (as well as inferior alveolar block discussed later, see Figure 9-31). 1, Deep temporal nerve; 2, deep temporal artery; 3, lateral pterygoid muscle; 4, maxillary nerve; 5, PSA nerve; 6, PSA artery; 7, infratemporal surface of maxilla; 8, buccinator muscle; 9, buccal nerve; 10, medial pterygoid muscle; 11, lingual nerve; 12, IA nerve; 13, IA artery; 14, nerve to mylohyoid muscle; 15, lateral pterygoid muscle; 16, maxillary artery; 17, masseteric nerve; 18, disc of the joint and mandibular condyle; 19, joint capsule; 20, temporal bone; 21, mandibular ramus; 22, tongue. (From Logan BM, Reynold PA, Hutching RT: McMinn’s color atlas of head and neck anatomy, ed 4, London, 2010, Mosby Ltd.)

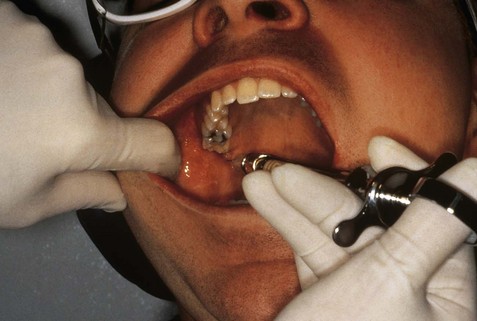

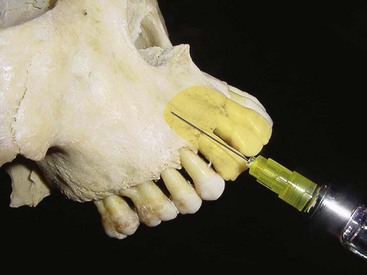

The injection site for the PSA block is at the height of the mucobuccal fold superior to the apex of the maxillary second molar, distal to the zygomatic process of the maxilla (Figures 9-4 and 9-5). The needle is inserted into the mucobuccal fold in a distal and medial direction to the tooth and maxilla without contacting the maxilla in order to reduce trauma, and then the injection is administered (Figure 9-6).

FIGURE 9-4 Dissection with needle at the injection site for a posterior superior alveolar block. 1, Posterior surface of maxilla; 2, lateral pterygoid muscle; 3, medial pterygoid muscle; 4, buccal nerve; 5, maxillary artery; 6, PSA nerve and vessels; 7, parotid duct; 8, buccinator muscle; 9, lingual nerve; 10, IA nerve; 11, IA artery; 12, labial commissure; 13, upper lip. (From Logan BM, Reynold PA, Hutching RT: McMinn’s color atlas of head and neck anatomy, ed 4, London, 2010, Mosby Ltd.)

FIGURE 9-5 Injection site for the posterior superior alveolar block is palpated at the height of the mucobuccal fold at the apex of the maxillary second molar.

FIGURE 9-6 Needle penetration during a posterior superior alveolar block of the mucobuccal fold at the apex of the maxillary second molar without contacting the maxilla, with injection site highlighted.

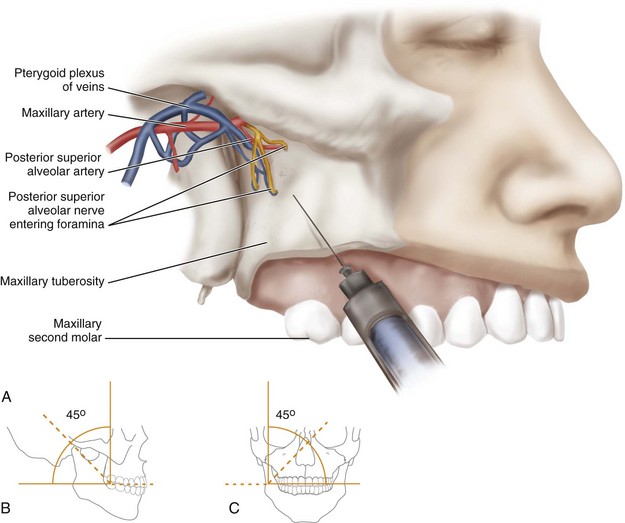

In addition, a certain angulation of the needle to the injection site must be maintained throughout. The angulation of the needle should be upward or superiorly at a 45° angle to the occlusal plane, inward or medially at a 45° angle to the occlusal plane, and backward or posteriorly at a 45° angle to the long axis of the second maxillary molar. The syringe barrel should be extended from the ipsilateral labial commissure to help with this angulation.

If bone is contacted too early or resistance is felt, the angle of the needle toward the midline is too great (more than 45°) and the syringe barrel needs to be closer to the occlusal plane, thereby reducing the angle (less than 45°). A conservative insertion technique should be used so as to reduce possible complications and still insure an effective outcome (discussed next).

Symptoms And Possible Complications Of Psa Block

Usually there are no symptoms with the PSA block since there is not any soft tissue anesthesia, only hard tissue anesthesia. Thus the patient frequently has difficulty determining the extent of anesthesia because the lip or tongue does not feel numb (i.e., with the more commonly used inferior alveolar or mandibular block). Instead, the patient will state that the teeth in the area feel dull when gently tapped, and there will be an absence of discomfort during dental procedures. It may be necessary to inform the patient of this before starting the procedure so as to reduce fears that the anesthetic has not worked.

Complications can occur if the needle is advanced too far distally into the tissue during a PSA block (Figure 9-7 and see Figure 6-13). The needle may penetrate the pterygoid plexus of veins and the maxillary artery if overinserted. This results in a bluish-reddish extraoral swelling of hemorrhaging blood in the tissue on the affected side of the face in the infratemporal fossa a few minutes after the injection, progressing over time inferiorly and anteriorly toward the lower anterior region of the cheek, ending over time in an extraoral hematoma (see Figure 3-61).

FIGURE 9-7 Insertion of the needle during a posterior superior alveolar block (A). If the needle is overinserted, it can penetrate the pterygoid plexus of the veins and maxillary artery, which may lead to complications such as a hematoma. Note (B) the needle angulation at a 45° angle to the maxillary occlusal plane and (C) at a 45° angle to the midsagittal plane on the skull.

If the needle is contaminated, there may be a spread of infection to the cavernous sinus (see Chapter 12). Aspiration should always be attempted in all injections before administration in order to avoid injection into blood vessels, and strict standard precautions of infection control should be observed.

Inadvertent and harmless anesthesia of branches of the mandibular nerve may occur with a PSA block because they are located lateral to the PSA nerve. This may result in varying degrees of lingual anesthesia and anesthesia of the lower lip in some patients.

Middle Superior Alveolar Block

The middle superior alveolar block or MSA block is indicated for dental procedures on the maxillary premolars and mesiobuccal root of the maxillary first molar. This block is utilized even if the MSA nerve is not present in order for completeness of anesthesia to the entire maxillary quadrant or when working only on the maxillary premolars. Where the MSA nerve is absent, the area is innervated by both the PSA and ASA nerves.

Thus the MSA block anesthetizes the pulp of the maxillary first and second premolars and possibly the mesiobuccal root of the maxillary first molar and the associated buccal periodontal tissue including the gingiva, periodontal ligament, and alveolar bone if the MSA nerve is present, which occurs in only 28% of the population. If lingual tissue (or palatal) anesthesia of these teeth is desired, the greater palatine block may also be necessary.

Target Area And Injection Site For Msa Block

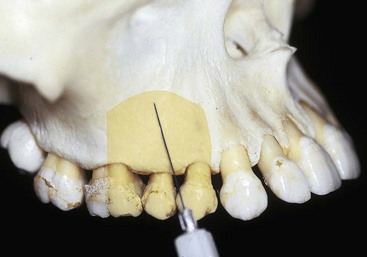

The target area for the MSA block is the MSA nerve at the apex of the maxillary second premolar (Figures 9-8 and 9-9 and see Figure 8-13). Thus the injection site is at the height of the mucobuccal fold at the apex of the maxillary second premolar (Figure 9-10). The needle is inserted into the mucobuccal fold until its tip is located superior to the apex of the maxillary second premolar without contacting the maxilla in order to reduce trauma, and then the injection is administered (Figure 9-11).

FIGURE 9-8 Target area for the middle superior alveolar block is the MSA nerve at the apex of the maxillary second premolar with anesthetized area highlighted.

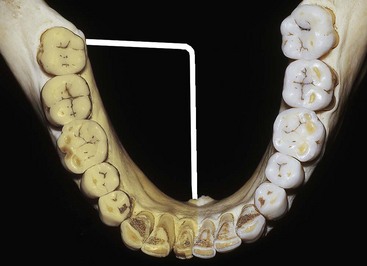

FIGURE 9-9 Dissection showing a coronal section of maxilla and buccal mucosa through the permanent maxillary first premolar. With one needle (left) at the injection site for middle superior alveolar block and the other needle (right) at the injection site for the anterior middle superior alveolar block. 1, Upper lip; 2, height of mucobuccal fold; 3, alveolar process of maxilla; 4, apex of tooth; 5, pulp cavity; 6, gingival margin; 7, mucoperiosteum of hard palate; 8, labial mucosa. (From Logan BM, Reynold PA, Hutching RT: McMinn’s color atlas of head and neck anatomy, ed 4, London, 2010, Mosby Ltd.)

Anterior Superior Alveolar Block

The anterior superior alveolar block or ASA block is commonly used in conjunction with an MSA block instead of using an infraorbital block alone. Communication occurs between the ASA nerve and the MSA and PSA Nerves. In addition, many times the ASA nerve provides crossover-innervation to the contralateral side in a patient; this may need to be taken into account when using local anesthesia in this area. Bilateral injections of the ASA block or local infiltration over the contralateral maxillary central incisor may be indicated.

The ASA block anesthetizes the pulp of the maxillary canine and incisor teeth, as well as the associated facial periodontal tissue including the gingiva, periodontal ligament, and alveolar bone. If lingual (or palatal) tissue anesthesia of these teeth is desired, a nasopalatine block may also be indicated.

Target Area And Injection Site For Asa Block

The target area for the ASA block is the ASA nerve at the apex of the maxillary canine (Figure 9-12 and see Figures 3-47 and 8-13 ). The injection site is at the height of the mucobuccal fold at the apex of the maxillary canine, just anterior to and parallel with the canine eminence. Note that this is over the canine fossa located anterior to the canine eminence (Figure 9-13). The needle tip is placed superior to the apex of the maxillary canine without contacting the maxilla so as to reduce trauma, and then the injection is administered (Figure 9-14). This is approximately at 10° angle off an imaginary line drawn parallel to the long axis of the maxillary canine tooth.

FIGURE 9-12 Target area for the anterior superior alveolar block is the ASA nerve at the apex of the maxillary canine, with anesthetized area highlighted.

Infraorbital Block

The infraorbital block (in-frah-or-bit-al) or IO block is a useful block because it anesthetizes both the MSA and ASA nerves thus covering the region for both the MSA and ASA blocks. The IO block is used for anesthesia of the maxillary premolars, canine, and incisors. The IO block is indicated when the dental procedures involve more than two maxillary premolars or anterior teeth and the overlying facial periodontium including the gingiva, periodontal ligament, and alveolar bone. If lingual (or palatal) tissue anesthesia is necessary, a nasopalatine block may also be indicated.

In many patients the ASA nerve provides crossover innervation to the contralateral side, so bilateral injections of the IO block or local infiltration over the contralateral maxillary central incisor may be indicated.

Target Area And Injection Site For Io Block

The target area for the IO block is the ASA and MSA nerves as they move superiorly to join the IO nerve after it enters the infraorbital foramen (Figure 9-15 and see Figures 3-47 and 8-13 ). Branches of the IO nerve to the lower eyelid, side of the nose, and upper lip are also inadvertently anesthetized.

FIGURE 9-15 Target area for the infraorbital block is the anterior superior alveolar and middle superior alveolar nerves at the infraorbital foramen, with anesthetized area highlighted. Note the position of the infraorbital rim.

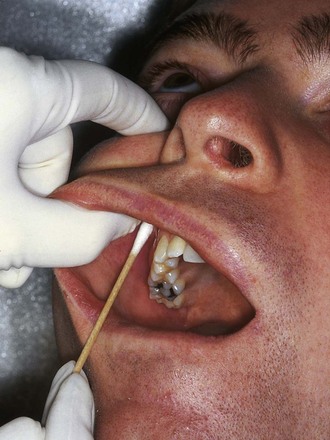

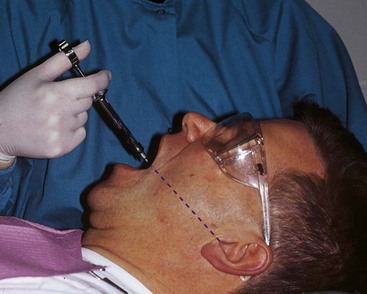

To locate the infraorbital foramen, palpate extraorally the patient’s infraorbital rim and then move slightly downward about 10 mm, applying pressure until the depression created by the infraorbital foramen is located (Figure 9-16). The patient may feel a dull aching sensation when pressure is applied to the nerves in the region. The infraorbital foramen is about 1 to 4 mm medial to the pupil of the eye if the patient looks straightforward. There is a linear relationship between the pupil of the eye, the infraorbital notch, and the ispsilateral labial commissure.

FIGURE 9-16 Palpation for the infraorbital block of the depression created by the infraorbital foramen by moving slightly downward on the face from the infraorbital rim.

The injection site for the IO block is at the height of the mucobuccal fold at the apex of the maxillary first premolar. A preinjection approximation of the depth of needle penetration for the IO block can be made by placing one finger on the infraorbital foramen and the other one on the injection site and estimating the distance between them (Figure 9-17). The approximate depth of needle penetration for the IO block may vary: in a patient with a higher or deeper mucobuccal fold or more inferior infraorbital foramen, less tissue penetration will be required than in a patient with a lower or shallower mucobuccal fold or more superior infraorbital foramen.

FIGURE 9-17 Injection site for the infraorbital block is palpated at the height of the mucobuccal fold at the apex of the maxillary first premolar. Pressure over the infraorbital foramen is maintained throughout the injection.

The needle is inserted for the IO block into the mucobuccal fold while keeping the finger of the other hand on the infraorbital foramen during the injection to help keep the syringe toward the foramen (Figure 9-18). The needle is advanced while keeping it parallel with the long axis of the tooth to avoid premature contact with the maxilla. The point of contact of the needle with the maxilla should be the upper rim of the infraorbital foramen, and then the injection is administered. Keeping the needle in contact with the bone at the roof of the infraorbital foramen prevents overinsertion and possible puncture of the orbit.

FIGURE 9-18 Needle penetration during an infraorbital block at the height of the mucobuccal fold at the apex of the maxillary first premolar until contact is made with the maxilla. Injection site highlighted. Pressure over the infraorbital foramen and contact with the maxilla is maintained throughout the injection.

Symptoms And Possible Complications Of Io Block

Symptoms with the IO block include harmless tingling and numbness of the eyelid, side of the nose, and upper lip because there is inadvertent anesthesia of the branches of the IO nerve. Additionally, there is numbness in the teeth and associated tissue along the distribution of both the ASA and MSA nerves and absence of discomfort during dental procedures. Rarely the complication of a hematoma may develop across the lower eyelid and the tissue between it and the infraorbital foramen.

Greater Palatine Block

The greater palatine block (pal-ah-tine) or GP block is used during dental procedures that involve more than two maxillary posterior teeth or palatal soft tissue distal to the maxillary canine. This maxillary block anesthetizes the posterior part of the hard palate, anteriorly as far as the maxillary first premolar and medially to the midline as well as the lingual (or palatal) gingival tissue in the area.

Because the GP block does not provide pulpal anesthesia of the area teeth, the use of the ASA, PSA, and MSA blocks or the IO block may also be indicated. In addition, soft tissue anesthesia in the palatal area of the maxillary first premolar may prove inadequate because of overlapping nerve fibers from the nasopalatine nerve in the palatine process of the maxilla in the anterior hard palate. This lack of anesthesia may be corrected by additional administration of the nasopalatine block.

Because the overlying palatal tissue is dense and adheres firmly to the underlying palatal bone, the use of pressure anesthesia over the depression of the greater palatine foramen posterior to the injection site throughout the injection to blanch the tissue will reduce patient discomfort. This pressure anesthesia of the tissue produces a dull ache that blocks pain impulses that arise from needle penetration.

Target Area And Injection Site For Gp Block

The target area for the GP block is anterior to where the GP nerve enters the greater palatine foramen from its location between the mucoperiosteum and horizontal plate of palatine bone of the posterior hard palate (Figures 9-19 and 9-20 and see Figures 3-44 and 8-14 ). The greater palatine foramen is usually seen as a depression on the palatal surface at the junction of the maxillary alveolar process and posterior hard palate, at the apex of the maxillary second (in children) or third molar, about 10 mm medial and directly superior to the lingual (or palatal) gingival margin. In patients who have a vaulted palate, the foramen will appear closer to the dentition. Conversely, in patients with a more shallow palate, the foramen will appear closer to the midline. In patients lacking a visible depression, landmarks are useful, and palpation of the area will emphasize the depression of the foramen.

FIGURE 9-19 Target area for the greater palatine block is anterior to the greater palatine foramen, which is at the junction of the maxillary alveolar process and the hard palate, at the apex of the maxillary second or third molar. Area anesthetized highlighted.

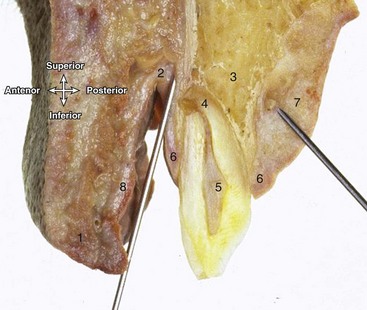

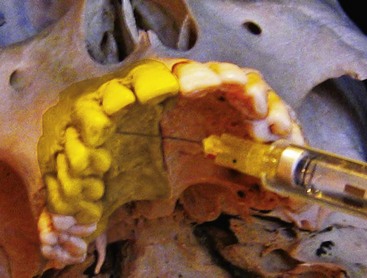

FIGURE 9-20 Dissection of hard palate with a needle at the injection site for the greater palatine block (also showing landmarks for nasopalatine block). 1, GP foramen; 2, mucoperiosteum of the hard palate; 3, GP nerve traveling horizontally; 4, incisive canal (and arrow); 5, incisive foramen; 6, nasopalatine nerve. (From Logan BM, Reynold PA, Hutching RT: McMinn’s color atlas of head and neck anatomy, ed 4, London, 2010, Mosby Ltd.)

The site of injection is in palatal tissue anterior to the depression created by the greater palatine foramen (Figure 9-21). This depression can be palpated about midway between the median palatine raphe and the lingual (or palatal) gingival margin of the maxillary molar tooth. The needle for the GP block is inserted into the previously blanched palatal tissue at a 90° angle to the palate, with the needle bowing slightly (Figure 9-22). The needle is advanced during the GP block until the palatine bone is contacted, and then the injection is administered. There is no need to enter the greater palatine canal. Although such an entrance is not potentially hazardous, it is not necessary for this block and would prove difficult with the angulation of the needle as recommended.

FIGURE 9-21 Palpation of the depression created by the greater palatine foramen. Surrounding palatal tissue is blanched throughout the injection for the greater palatine block to cause pressure anesthesia.

FIGURE 9-22 Needle penetration during a greater palatine block of the palatal tissue anterior to the greater palatine foramen until contact is made with maxilla. Injection site is highlighted. Needle may bow slightly and the blanching of surrounding palatal tissue is maintained throughout the injection.

Symptoms And Possible Complications Of Gp Block

Symptoms with the GP block are numbness in the posterior hard palate and an absence of discomfort during dental procedures. Some patients may become uncomfortable and may gag if the soft palate becomes inadvertently and harmlessly anesthetized, a distinct possibility given the proximity of the lesser palatine nerve.

Nasopalatine Block

The nasopalatine block (nay-zo-pal-ah-tine) or NP block is useful for anesthesia of the bilateral anterior part of the hard palate, from the mesial of the maxillary right first premolar to the mesial of the maxillary left first premolar. Both the right NP nerve and the left NP nerve are anesthetized by this block. The NP block is used when lingual (or palatal) soft tissue anesthesia is required for two or more maxillary anterior teeth.

The NP block does not provide pulpal anesthesia of these teeth, so additional anesthesia such as the MSA and ASA block or the IO block may be indicated. In addition, anesthesia in the lingual (or palatal area) of the maxillary canine may prove inadequate because of overlapping nerve fibers from the greater palatine nerve; this lack of anesthesia may be corrected by additional administration of the ipsilateral GP block if the patient is still feeling discomfort during treatment.

Because the dense overlying palatal tissue adheres firmly to the underlying maxilla, the use of pressure anesthesia on the contralateral side of the injection site of the incisive papilla throughout the injection to blanch the tissue will reduce patient discomfort. This pressure anesthesia to the tissue produces a dull ache to block pain impulses that arise from needle penetration.

Target Area and Injection Site for NP Block

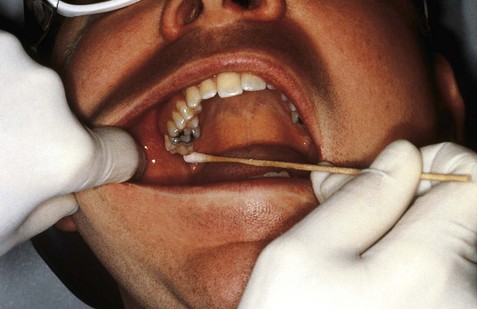

The target area for the NP block is both the right and left NP nerves as they enter the incisive foramen of the maxilla from the mucosa of the anterior hard palate, beneath the incisive papilla (Figures 9-23 and 9-24; see Figures 3-44, 8-14, and 9-9).

FIGURE 9-23 Target area for the nasopalatine block is both the right and left nasopalatine nerves at the incisive foramen on the anterior hard palate of the maxilla, lingual to the maxillary central incisors, with area anesthetized highlighted.

FIGURE 9-24 Dissection showing a sagittal section of the right side of the hard palate at the target area for the nasopalatine block. 1, Olfactory nerve; 2, NP nerve; 3, incisive canal; 4, anterior ethmoidal nerve; 5, incisive foramen; 6, upper lip. (From Logan BM, Reynold PA, Hutching RT: McMinn’s color atlas of head and neck anatomy, ed 4, London, 2010, Mosby Ltd.)

The injection site is the lingual (or palatal) tissue lateral to the incisive papilla, which is located at the midline, about 10 mm lingual to the maxillary central incisor teeth in case there is no telltale bulge of the structure of the incisive papilla (Figure 9-25). Never insert the needle directly into the incisive papilla since this can be extremely painful to the patient. Pressure anesthesia is performed on the palatal tissue on the contralateral side of the incisive papilla.

FIGURE 9-25 Injection site for the nasopalatine block is palpated at the palatal tissue lateral to the incisive papilla on the anterior hard palate. Palatal tissue on the contralateral side of the incisive papilla is blanched throughout the injection to cause pressure anesthesia.

The needle is inserted for this block into the previously blanched palatal tissue at a 45° angle to the palate (Figure 9-26). The needle is advanced into the tissue until the maxilla is contacted, and then the injection is administered. Also there is no need to enter the incisive canal via the foramen; in fact the needle cannot enter the foramen with the recommended position of the needle.

Anterior Middle Superior Alveolar Block

The anterior middle superior alveolar block or AMSA block is useful for soft tissue and pulpal anesthesia of the large area covered by the ASA, MSA, GP, and NP blocks in the maxillary arch. Thus the single-site palatal injection of the AMSA can anesthetize multiple teeth (from the maxillary second premolar through the maxillary central incisor and associated tissue), without causing usual collateral anesthesia to the soft tissue of the patient’s upper lip and face.

The use of pressure anesthesia throughout this injection near the injection site to blanch the tissue will reduce patient discomfort. This pressure anesthesia to the tissue produces a dull ache to block pain impulses that arise from needle penetration.

The AMSA, together with a traditional PSA block, will anesthetize a maxillary quadrant. This injection is commonly used in esthetic/cosmetic dentistry because after the procedures are completed, the patient’s smile line can be assessed immediately and accurately. However, studies show that this injection is best accomplished with a computer-controlled delivery device (CCDD) because it regulates the pressure and volume ratio of solution delivered, which is not readily attained with a manual syringe. In addition, more recent studies show that due to the extensive anatomy involved, this block may be variable in depth and duration of anesthesia.

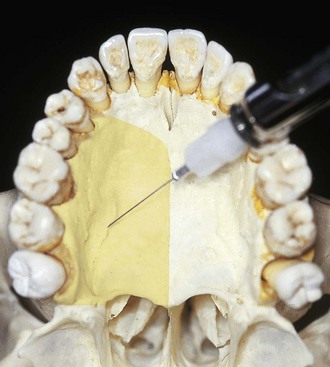

Target Area and Injection Site for AMSA Block

The target area for the AMSA block is the tissue of the hard palate (Figure 9-27; see figure 9-9). This block takes advantage of a number of small pores in the maxilla in the area and the tight attachment of the palatal tissue. As the agent penetrates the pores, it has access to the anterior to middle part of the dental plexus, which then anesthetizes the teeth and associated facial tissue as well as the lingual tissue of the surrounding palate.

FIGURE 9-27 Target area for the anterior middle superior alveolar block is on the hard palate of the maxilla, area anesthetized highlighted.

The injection site for the AMSA block is an area bisecting the apices of the maxillary premolars, as well as being midway between the median palatal raphe (overlying the median palatine suture) and the lingual (or palatal) gingival margin (Figure 9-28 and see Figure 3-48). Orientation of the syringe barrel should be from the contralateral premolars. The previously blanched tissue is approached with the needle at a 45° angle until the palatal tissue is penetrated and the maxilla is contacted, and then the injection is administered (Figure 9-29).

Symptoms and Possible Complications of AMSA Block

Symptoms with the AMSA block include variable numbness of the large area that is normally innervated by the ASA, MSA, GP, and NP blocks. Blanching also occurs on both the palatal and buccal tissue after the AMSA block and, if excessive, may cause postoperative tissue ischemia and sloughing. If excessive blanching is noted, slowing or stopping the injection for a few seconds to let the agent dissipate will diminish the chance of this postoperative event. Other complications are extremely rare.

Mandibular Nerve Anesthesia

The mandibular nerve and its branches can be anesthetized in a number of ways depending on the tissue and structures requiring anesthesia (Table 9-2; see Figure 9-1). However, infiltration anesthesia of the mandible is not as successful as that of the maxilla because overall the bone of the mandible is denser than the maxilla over similar teeth, especially in the area of the mandibular posterior teeth. This can be easily noted with a panoramic radiograph (see Figure 3-50). For this reason, nerve blocks are preferred to local infiltrations in most parts of the mandible, unlike the maxillae.

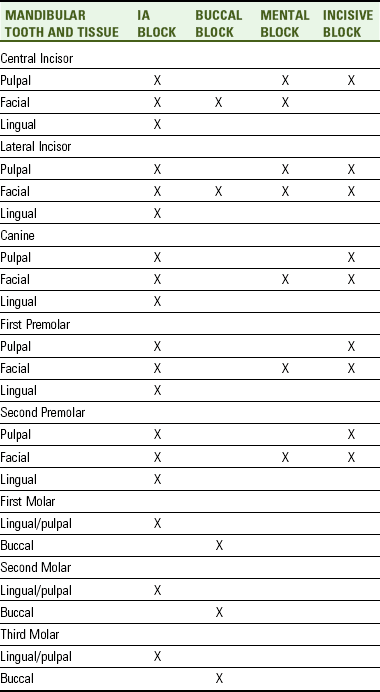

TABLE 9-2

Summary of Mandibular Local Anesthesia of the Teeth and Associated Tissue

Substantial variation also exists in the anatomy of local anesthetic landmarks of the mandibular bone and nerves compared with similar structures in the maxilla, complicating mandibular anesthesia, and possibly increasing the need for troubleshooting of failure cases. This text covers some of the most common mandibular variations; variation in the anatomy of the mandible is what mainly gives the face its character (see Chapter 3).

Pulpal anesthesia is achieved through anesthesia of each nerve’s dental branches as they extend into the pulp by way of each tooth’s apical foramen. Both the hard and soft tissue of the periodontium are anesthetized by way of the interdental and interradicular branches for each tooth.

The inferior alveolar block is generally recommended for anesthesia of the mandibular teeth and their associated lingual tissue to the midline, as well as the facial tissue anterior to the mandibular first molar. The buccal block is generally recommended for anesthesia of the tissue buccal to the mandibular molars.

The mental block is generally recommended for anesthesia of the facial tissue anterior to the mental foramen, usually mandibular premolars and anterior teeth. The incisive block is generally recommended for anesthesia of the teeth and associated facial tissue anterior to the mental foramen, usually mandibular premolars and anterior teeth. The Gow-Gates mandibular block anesthetizes most of the mandibular nerve and is useful for extensive procedures during quadrant dentistry or with failure of the inferior alveolar block.

Inferior Alveolar Block

The inferior alveolar block also known as the IA block, or incorrectly as the mandibular block, is the most commonly used injection in dentistry. The IA block is used when dental procedures are performed on the mandibular teeth and pulpal anesthesia is necessary. This block also provides anesthesia of the lingual periodontium of all the mandibular teeth, as well as anesthesia of the facial periodontium of the mandibular anterior and premolar teeth. Since not all of the mandibular nerve is anesthetized with an inferior alveolar block, it is not considered a mandibular block; in contrast, the Gow-Gates mandibular block is considered a mandibular block since all of the mandibular nerve is anesthetized (discussed later in this chapter).

Even though the IA block is the most commonly used dental injection, it is not always initially successful. This may mean that the patient must be reinjected to achieve the necessary anesthesia of the tissue. This lack of consistent success is due in part to anatomic variation in the height of the mandibular foramen on the medial side of the ramus and the great depth of soft tissue penetration required to achieve pulpal anesthesia. Other techniques to achieve mandibular anesthesia, such as the Gow-Gates mandibular block, may also be employed with failure of the IA block.

Additional use of the buccal block may be indicated if anesthesia of the buccal periodontium of the mandibular molars is also necessary. In some cases there is crossover-innervation between the left and right incisive nerves. The incisive nerve is a branch of the mandibular nerve that serves the pulp of the mandibular anterior teeth. If this is the case, a bilateral IA block can be used, but it is not recommended (discussed later).

Thus, bilateral IA blocks are usually avoided unless absolutely necessary. This is because bilateral mandibular injections produce complete anesthesia of the body of the tongue and floor of the mouth, which can cause difficulty with swallowing and speech, especially in patients with full or partial removable mandibular dentures, until the effects of the local anesthetic agent wear off. Comprehensive dental treatment planning can usually prevent the need for bilateral IA blocks by treating the mandible in quadrants or even sextants.

More often, the use of a contralateral incisive block or local infiltration at the apices of the mandibular teeth that fail to achieve initial pulpal anesthesia may be indicated or when larger scope of anesthesia is desired such as the full mandibular arch. However, local infiltrations on the facial surface of the anterior mandible are more successful than more posterior injections but less successful than injections over the maxillae in similar locations. Again, these differences in success rates are due to differences in the density of the facial plates of bone of the mandible as compared to those of the maxillae and even vary along the length of the mandible.

Target Area And Injection Site For Ia Block

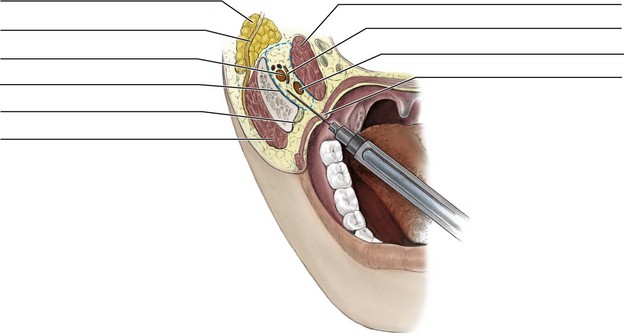

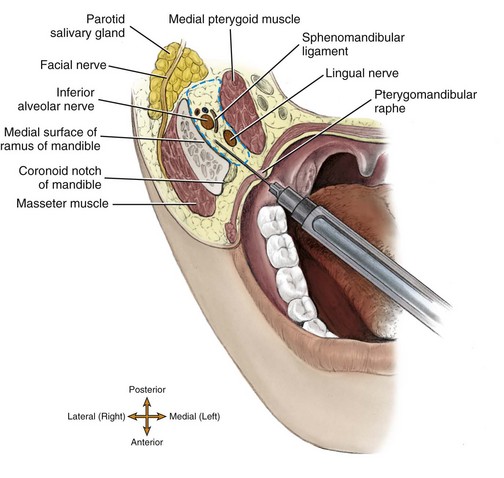

The target area for the IA block is at the entry point of the IA nerve as it moves inferiorly to enter into the mandibular foramen, overhung anteriorly by the lingula (Figures 9-30, 9-31, and 9-32; see Figures 9-3, 3-52, and 3-53). The adjacent anteriorly placed lingual nerve will also be anesthetized as the local anesthetic agent diffuses so there is no need for a separate injection to this nerve (see Figures 8-19 and 8-20). The local anesthetic agent must be accurately deposited within 1 mm of the target area to achieve anesthesia, which may prove difficult since most of the deeper anatomy is not visible and surface landmarks must be relied upon.

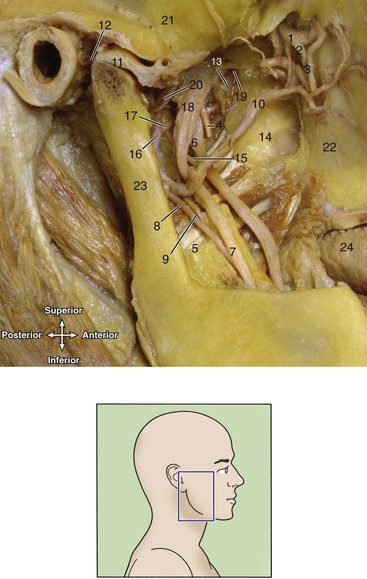

FIGURE 9-31 Dissection of the right infratemporal fossa (inset, note removal of lateral pterygoid muscle, zygomatic arch, and part of mandible) at target area for the inferior alveolar block (as well as posterior alveolar block discussed earlier, see Figure 9-3). 1, Maxillary nerve; 2, PSA nerve; 3, PSA artery; 4, buccal nerve; 5, medial pterygoid muscle; 6, lingual nerve; 7, IA nerve; 8, IA artery; 9, nerve to mylohyoid muscle; 10, maxillary artery; 11, disc of TMJ and mandibular condyle; 12, joint capsule; 13, nerve to medial pterygoid muscle; 14, lateral pterygoid plate; 15, chorda tympani nerve; 16, middle meningeal artery; 17, accessory meningeal artery; 18, mandibular nerve; 19, nerve to lateral pterygoid muscle; 20, auriculotemporal nerve; 21, temporal bone; 22, maxilla; 23, mandibular ramus; 24, tongue. (From Logan BM, Reynold PA, Hutching RT: McMinn’s color atlas of head and neck anatomy, ed 4, London, 2010, Mosby Ltd.)

FIGURE 9-32 Target area for the inferior alveolar block is the inferior alveolar nerve at the mandibular foramen on the medial surface of the mandibular ramus, inferior to the lingula, and at the same height as the coronoid notch.

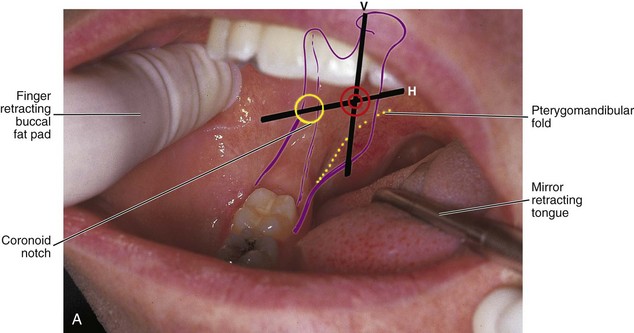

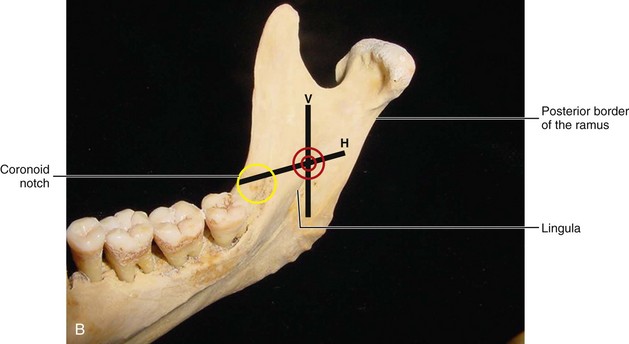

The injection site for the IA block is the mandibular tissue on the medial border of the mandibular ramus (Figures 9-33 and 9-34). Again, mainly hard tissue (such as the coronoid notch and the occlusal plane of the mandibular molars) is used for landmarks to locate the injection site to reduce errors caused by patient soft tissue variance.

FIGURE 9-33 Injection site for the inferior alveolar block is palpated at the depth of the pterygomandibular space on the medial surface of the ramus.

FIGURE 9-34 Dissection of the right infratemporal fossa with a needle at the injection site for the inferior alveolar block. 1, Lingula; 2, IA artery; 3, IA nerve; 4, lingual nerve; 5, medial pterygoid muscle; 6, buccal nerve; 7, buccinator muscle; 8, lateral pterygoid muscle; 9, parotid duct; 10, maxilla; 11, upper lip; 12, mandibular ramus. (From Logan BM, Reynold PA, Hutching RT: McMinn’s color atlas of head and neck anatomy, ed 4, London, 2010, Mosby Ltd.)

The height of the injection for the IA block is determined by palpating the coronoid notch, the greatest depression on the anterior border of the ramus (see Figures 3-52 and 3-53). To determine the injection height, it helps to visualize an imaginary horizontal line that extends posteriorly from the coronoid notch to the pterygomandibular fold (Figure 9-35). The pterygomandibular fold covers the deeper pterygomandibular raphe, which is located between the buccinator and superior pharyngeal constrictor muscles. This fold extends from behind the most distal mandibular molar and retromolar pad and runs horizontally to the posterior border of the mandible and then turns superior to the junction of hard and soft palates, separating the buccal mucosa from the pharynx (see Figure 2-21). This fold stretches to become accentuated as the patient opens the mouth wider, which is an important instruction to give to the patient when administering this block.

FIGURE 9-35 A, Insertion site for inferior alveolar block (bullseye) is determined from the intersection of an imaginary horizontal solid line (H) of the height with a vertical solid line (V) of the anteroposterior direction, which is at the depth of the pterygomandibular space, lateral to the pterygomandibular fold (dashed line), and at the same height as the coronoid notch (yellow circle). B, Medial surface of the mandible showing the bony landmarks and imaginary lines.

This imaginary horizontal line showing the height of the IA block injection site is also parallel to and 6 to 10 mm superior to the occlusal plane of the mandibular molar teeth in the majority of adults. In children and small adults, this imaginary horizontal line for the height of the injection should be at the occlusal plane of the mandibular molars (see Figure 9-35). For children, this is due to the fact that the mandible has not reached its mature size. The retracting finger can be kept at this height to help maintain it throughout the injection since being too inferior to the injection site is the most commonly cited cause of missed IA blocks. This will also help keep the needle and syringe parallel to the occlusal plane at all times to ensure correct placement of the needle tip near the mandibular foramen. In partially edentulous patients when the mandibular molars are absent, the mandibular foramen may appear to be more superior than when the dentition is present because the occlusal plane of the missing mandibular molars is not present as a guide.

The anteroposterior direction of the IA block injection is determined at the same time as the height of the injection. To determine this anteroposterior direction, it helps to visualize an imaginary vertical line, three fourths of the distance between the coronoid notch and the posterior border of the ramus, demarcated by the pterygomandibular fold as it turns upward toward the soft palate (see Figure 9-35).

Thus the injection site of the IA block is determined by the intersection of these two imaginary lines, one horizontal and one vertical, which is located at the deepest or most posterior part of the pterygomandibular space, lateral to the pterygomandibular fold and the sphenomandibular ligament (Figure 9-36; see Figures 9-35 and 11-8). To accomplish this, the syringe barrel is usually superior to the contralateral mandibular second premolar at the labial commissure.

FIGURE 9-36 Needle penetration during an inferior alveolar block of the mandibular tissue at the depth of the pterygomandibular space until contact with the medial surface of the mandible. Injection site is highlighted. Note that the syringe barrel is usually superior to the contralateral mandibular second premolar and at the labial commissure.

The needle is inserted into the tissue of the pterygomandibular space until the mandible is contacted, and then the injection is administered (Figures 9-37 and 9-38). It is not necessary to deposit small amounts of local anesthetic agent as the needle enters the tissue for the IA block to anesthetize the adjacent anteriorly placed lingual nerve because anesthesia of the lingual nerve will occur through diffusion of the local anesthetic agent as it is placed near the IA nerve. These small amounts injected early will also not reduce any tissue discomfort for the patient.

FIGURE 9-37 Needle penetration into the pterygomandibular space (dashed line) during an inferior alveolar block until contact with the medial surface of the mandible. If the needle is inserted too far posteriorly, it may enter the parotid salivary gland containing the facial nerve, causing the complication of transient facial paralysis.

FIGURE 9-38 Dissection showing a horizontal section of the right infratemporal fossa with a needle at the injection site for the inferior alveolar block. 1, Coronoid notch (superior to external oblique ridge); 2, mylohyoid line; 3, lingula; 4, mandibular foramen; 5, parotid salivary gland; 6, styloid process; 7, maxillary artery; 8, IA vein; 9, IA artery; 10, IA nerve; 11, lingual nerve; 12, sphenomandibular ligament; 13, medial pterygoid muscle; 14, buccal nerve; 15, temporalis muscle; 16, pterygomandibular raphe; 17, buccinator muscle; 18, masseter muscle; 19, mandibular ramus; 20, buccal fat pad; 21, tongue. (From Logan BM, Reynold PA, Hutching RT: McMinn’s color atlas of head and neck anatomy, ed 4, London, 2010, Mosby Ltd.)

Troubleshooting Ia Block

Even though the IA block is the most commonly used dental injection, it is not always initially successful; documented failure rates are approximately 15% to 20%. Remember, this lack of consistent success is due in part to anatomic variation in the height of the mandibular foramen on the medial side of the ramus and the great depth of soft tissue penetration required to achieve pulpal anesthesia.

If bone is contacted early when trying to administer an IA block, the needle tip is located too far anterior on the ramus. Correction is made by withdrawing the needle partially or completely and bringing the syringe barrel more closely over the mandibular anterior teeth. This correction moves the needle tip more posteriorly when it is newly directed or reinserted.

In contrast, if bone is not contacted when trying to administer an IA block even with the usual depth of penetration by the needle, the needle tip is located too far posterior on the ramus. Correction is made by withdrawing the needle partially or completely and bringing the syringe barrel more closely over the mandibular molars. This correction moves the needle tip more anteriorly when it is newly directed or reinserted.

At all times, it is important not to deposit the local anesthetic agent if bone is not contacted on initial insertion of the needle for an IA block. The needle tip may be too posterior and thus resting within the parotid salivary gland carrying the seventh cranial or facial nerve, resulting in complications (discussed later; see Figures 9-37 and 9-38).

In addition, if the insertion and deposition are too shallow and bone is not contacted, the more shallow (or medially located) sphenomandibular ligament can become an outer physical barrier that stops the important diffusion of the local anesthetic agent to the deeper mandibular foramen and IA nerve, thus preventing the deeper and more profound pulpal anesthesia, allowing only the lingual nerve to be anesthetized.

If there is failure of anesthesia, mainly on the mandibular first molar, even when troubleshooting the injection, there may be accessory innervation of the mandibular teeth. Current thinking supports the mylohyoid nerve as the nerve that may be involved in the accessory mandibular innervation of the mandibular first molar. To correct this problem, local anesthesia of the mylohyoid nerve using infiltration technique on the lingual border of the mandible is indicated. This additional anesthetic technique is discussed in most current dental local anesthesia texts (see Appendix A). An additional block that has a higher success rate than the IA block and provides additional anesthesia for the mylohyoid nerve, the Gow-Gates mandibular block may need to be attempted (discussed later in this chapter).

Whenever a bifid IA nerve is detected by noting a doubled mandibular canal on intraoral radiograph, incomplete anesthesia of the mandible may follow an IA block. In many such cases a second mandibular foramen, more inferiorly placed, exists; studies show that it occurs in less than 1% of the population. To correct this, the local anesthetic agent is deposited more inferior to the usual anatomic landmarks.

Symptoms and Possible Complications of IA Block

Symptoms with the IA block include harmless numbness and tingling of the lower lip because the mental nerve, a branch of the IA nerve, is anesthetized. This is a good indication that the IA nerve is anesthetized, but it is not a reliable indicator of the depth of anesthesia, especially concerning pulpal anesthesia.

Another symptom is harmless numbness and tingling of the body of the tongue and floor of the mouth, which indicates that the lingual nerve, a branch of the mandibular nerve, is anesthetized. Important to note is that this anesthesia of the tongue may occur without anesthesia of the IA nerve due to the outer barrier presented by the more shallow sphenomandibular ligament (see earlier discussion). Possibly the needle was not advanced deeply enough into the tissue to anesthetize the deeper IA nerve. The most reliable indicator of a successful IA block is an absence of discomfort during dental procedures.

Another symptom that can occur is “lingual shock” as the needle passes by the lingual nerve during administration. The patient may make an involuntary movement, varying from a slight opening of the eyes to jumping in the chair. This symptom is only momentary, and anesthesia will quickly occur.

One complication with an IA block is transient facial paralysis if the facial nerve is mistakenly anesthetized. This can occur because of an incorrect administration of anesthetic into the deeper parotid salivary gland (carrying the seventh cranial or facial nerve) because the mandibular bone was not contacted (see Figures 9-37 and 9-38). Symptoms of this temporary loss of the use of the muscles of facial expression include the inability to close the eyelid and the drooping of the labial commissure on the affected side for a few hours (see Chapter 4).

Other complications such as hematoma can occur since this injection has the highest positive aspiration rate of all block injections (see Figure 6-18). Muscle soreness or limited movement of the mandible is rarely seen with this injection. Self-inflicted trauma such as lower lip biting and resulting swelling can also occur.

Finally, damage can occur after administration of the IA block, causing paresthesia, usually from trauma to the lingual nerve (see Chapter 8). Paresthesia is an abnormal sensation from an area such as burning or prickling, like a “pins-and-needles” feeling. Recent studies demonstrate that paresthesia may be due to lack of adequate fascia around the lingual nerve or possibly neurotoxicity from the local anesthetic agent, especially in patients that receive multiple injections to the area; other studies do not reach any set conclusions but state that permanent nerve damage can occur during nerve blocks. Paresthesia can also occur with the spread of dental infection (see Chapter 12), but it mainly occurs due to problematic extraction of impacted molars.

Buccal Block

The buccal block (or long buccal block) is useful for anesthesia of the buccal periodontium of the mandibular molars including the gingiva, periodontal ligament, and alveolar bone. Many times this block is not necessary, such as when the buccal tissue are not impacted by the dental procedures performed. However, this is a successful dental injection because the buccal nerve is readily located on the surface of the tissue and not within bone.

Target Area And Injection Site For Buccal Block

The target area for the buccal block is the buccal nerve (or long buccal nerve) as it passes anteriorly to the anterior border of the ramus and through the buccinator muscle before it enters the buccal region (Figure 9-39 and see Figure 8-18). Thus the injection site is the buccal tissue distal and buccal to the most distal mandibular molar in the mandibular arch, on the anterior border of the ramus (Figure 9-40). The needle is advanced until it contacts the mandible, and then the injection is administered (Figure 9-41).

FIGURE 9-39 Target area for the buccal block is the buccal nerve on the anterior border of the mandibular ramus, with area anesthetized highlighted.

Symptoms And Possible Complications Of Buccal Block

The patient rarely feels any symptoms with the buccal block because of the location and small size of the anesthetized area. There is usually only an absence of discomfort with dental procedures. In some cases self-inflicted trauma such as cheek bites occurs. The complication of a hematoma rarely occurs.

Mental Block

The mental block (ment-il) is used to anesthetize the facial periodontium of the mandibular premolars and anterior teeth on one side, including the gingiva, periodontal ligament, and alveolar bone. If pulpal anesthesia is necessary on the mandibular premolar or anterior teeth, administration of an incisive block (discussed later) or use of the IA block may be considered instead. This block also does not provide any lingual tissue anesthesia of the involved teeth.

Target Area And Injection Site For Mental Block

The target area for the mental block is anterior to where the mental nerve enters the mental foramen to merge with the incisive nerve within the mandibular canal to form the IA nerve (Figures 9-42 and 9-43 and see Figures 3-52 and 8-19).

FIGURE 9-42 Target area for the mental block is anterior to the mental foramen where the mental nerve enters on the surface of the mandible, usually between the apices of the mandibular first and second premolars. Area anesthetized is highlighted.

FIGURE 9-43 Dissection with a needle at the injection site for either the mental and incisive blocks. 1, Mental foramen; 2, depressor anguli oris muscle; 3, depressor labii inferioris muscle; 4, mental nerve and vessels; 5, lower chin; 6, neck. (From Logan BM, Reynold PA, Hutching RT: McMinn’s color atlas of head and neck anatomy, ed 4, London, 2010, Mosby Ltd.)

The mental foramen is usually located on the surface of the mandible between the apices of the mandibular first and second premolars. The mental foramen in adults faces posterosuperiorly. The mental foramen can be located on a radiograph before performing the injection to allow for a better determination of its position during palpation.

To locate the mental foramen for the mental block, palpate intraorally the depth of the mucobuccal fold between the apices of the mandibular first and second premolars or at a site indicated by a radiograph until a depression is felt on the surface of the mandible, surrounded by smoother bone (Figure 9-44). The patient will comment that pressure in this area produces soreness as the mental nerve is compressed against the mandible near the foramen. However, studies show that the mental foramen can be as far posterior as the mandibular first molar or as far anterior as the distal surface of the mandibular canine.

FIGURE 9-44 Palpation for either the mental or incisive block of the depression created by the mental foramen, usually located in the depth of the mucobuccal fold between the apices of the mandibular first and second premolars.

Thus the insertion site for a mental block is anterior to the depression created by the mental foramen at the depth of the mucobuccal fold with the needle in a horizontal manner, the syringe barrel resting on the lower lip. The needle is advanced into the depth of the mucobuccal fold without contacting the mandible, and then the injection is administered (Figure 9-45). There is no need to enter the mental foramen to achieve anesthesia; in fact the needle cannot enter the foramen with the newer recommended use of a horizontal position for the syringe.

Incisive Block

The incisive block (in-sy-ziv) anesthetizes the pulp and facial tissue of the mandibular teeth anterior to the mental foramen, usually mandibular premolars and anterior teeth. The incisive block has a high success rate because the incisive nerve is readily accessible. If lingual anesthesia is necessary, an IA block would be administered instead because the incisive block does not provide lingual anesthesia, or local infiltration of the lingual tissue can also be considered (discussed earlier with IA block). This block is also useful when there is crossover-innervation from the contralateral incisive nerve and there is still discomfort on the mandibular anterior teeth after giving an IA block.

Target Area and Injection Site for Incisive Block

The target area for the incisive block is the same as the mental block: it is anterior to where the mental nerve enters the mental foramen to merge with the incisive nerve to form the IA nerve (Figure 9-46; see Figures 9-43, 3-52, and 8-19).

FIGURE 9-46 Target area for the incisive block is anterior to where the mental nerve enters the mental foramen on the surface of the mandible, usually between the apices of the mandibular first and second premolars. Area anesthetized is highlighted.

The mental foramen is usually located on the surface of the mandible between the apices of the mandibular first and second premolars. The mental foramen in adults faces posterosuperiorly. The mental foramen can be located on a radiograph before performing the injection to allow for a better determination of its position.

To locate the mental foramen for the mental block, palpate intraorally the depth of the mucobuccal fold between the apices of the mandibular first and second premolars or at a site indicated by a radiograph until a depression is felt on the surface of the mandible, surrounded by smoother bone (see Figure 9-44). The patient will comment that pressure in this area produces soreness as the mental nerve is compressed against the mandible near the foramen. However, studies show that the mental foramen can be as far posterior as the mandibular first molar or as far anterior as the distal surface of the mandibular canine.

Thus the insertion site for an incisive block is anterior to the depression created by the mental foramen at the depth of the mucobuccal fold with the needle in a horizontal manner, the syringe barrel resting on the lower lip. The needle is advanced into the depth of the mucobuccal fold without contacting the mandible, and then the injection is administered (see Figure 9-45).

More local anesthetic agent is deposited within the tissue for the incisive block than for the mental block, and pressure is applied intraorally after the injection. This pressure forces more local anesthetic agent into the mental foramen, anesthetizing first the shallow mental nerve and then the deeper incisive nerve. Thus anesthesia of the tissue innervated by the mental nerve will precede that of the deeper incisive nerve’s tissue; and soft tissue anesthesia precedes pulpal anesthesia. It is important to note that it is not necessary to have the needle enter the mental foramen to achieve a successful block; in fact the needle cannot enter the foramen with the newer recommended use of a horizontal position for the syringe.

Symptoms And Possible Complications Of Incisive Block

The symptoms with the incisive block are the same as the symptoms of the mental block with harmless tingling and numbness of the lower lip, except that there is pulpal anesthesia of the involved teeth, and there is an absence of discomfort during dental procedures. As with a mental block, a hematoma rarely occurs.

Gow-Gates Mandibular Block

The nerves anesthetized with the Gow-Gates mandibular block or G-G block are the inferior alveolar, mental, incisive, lingual, mylohyoid, and auriculotemporal, as well as the (long) buccal nerves in most cases (Figure 9-47 and see Figures 8-16 and 8-17 ). It is considered a mandibular block because it anesthetizes almost the entire V3.

FIGURE 9-47 Area anesthetized by Gow-Gates mandibular block is highlighted and includes almost the entire tissue and structures innervated by the mandibular nerve (division).

The Gow-Gates technique is used in quadrant dentistry in which buccal soft tissue anesthesia from most distal mandibular molar to midline and lingual soft tissue is necessary, and in some cases when a conventional IA block is unsuccessful. One of the major advantages of the block is that its success rate is higher than that of an IA block even taking into account a slightly more complicated procedure. Studies show that its success may be related to the block being able to provide additional anesthesia to the mylohyoid nerve that has been shown to be involved in failure of the IA block (see earlier discussion).

Target Area And Injection Site For Gow-Gates Mandibular Block

The target area for the Gow-Gates mandibular block is the anteromedial border of the neck of the mandibular condyle, just inferior to the insertion of the lateral pterygoid muscle (Figure 9-48 and see Figures 4-23, 8-18, and 8-20). The injection site is located intraorally on the oral mucosa on the mesial of the mandibular ramus, just distal to the height of the mesiolingual cusp of the maxillary second molar, following an imaginary line extraorally from the ipsilateral intertragic notch of the ear to the ipsilateral labial commissure (Figure 9-49).

FIGURE 9-48 Target area for the Gow-Gates mandibular block is at the anteromedial border of the neck of the mandibular condyle, just inferior to the insertion of the lateral pterygoid muscle.

FIGURE 9-49 Imaginary extraoral line (dashed line) for determining the direction of the Gow-Gates mandibular block that extends from the intertragic notch of the ear to the ipsilateral labial commissure.

The extraoral landmarks of the intertragic notch and labial commissure are first located (Figure 9-50 and see Figures 2-4 and 2-10 ). The condyle assumes a more frontal position with the mouth open, and the injection site becomes closer to the mandibular nerve trunk, which is preferred during this injection (see Chapter 5). In contrast, with a more closed mouth, the condyle will move out of the injection site and the soft tissue will become thicker. In addition, leaving the mouth open after administration will allow complete diffusion of the agent to the inferior alveolar nerve since it places the nerve closer to the injection site at the neck of the mandibular condyle.

FIGURE 9-50 Injection site for the Gow-Gates mandibular block is palpated at the soft tissue just distal to the height of the mesiolingual cusp of the maxillary second molar, with its direction determined by following a line extraorally from the intertragic notch to the ipsilateral labial commissure.

Then the needle is used to determine the height for the injection by placing the needle just inferior to the mesiolingual cusp of the maxillary second molar (Figure 9-51). The syringe barrel is maintained over the contralateral mandibular canine-to-premolar region, such that the direction of the injection parallels the imaginary line connecting the ipsilateral labial commissure and the intertragic notch until contact is made with the neck of the mandibular condyle; the injection is then administered (Figure 9-52). The height of insertion is more superior to the mandibular occlusal plane than that of an IA block, around 10 to 25 mm depending on the skull’s size. When a maxillary third molar is present, the site of injection will be just distal to that tooth.

Symptoms And Possible Complications Of Gow-Gates Mandibular Block

The mandibular teeth to midline, the buccal mucoperiosteum and mucous membranes, and lingual soft tissue and periosteum will be anesthetized. Inadvertently, the anterior two thirds of the tongue, the floor of the mouth, and the body of the mandible and inferior ramus, as well as the skin over the zygomatic bone and the posterior buccal and temporal regions, will feel numb.

The two main disadvantages of the Gow-Gates technique are the numbness of the lower lip, as well as the temporal region, and the longer time necessary for the anesthetic to take effect (see earlier discussion). The increased time is due to the larger size of the nerve trunk being anesthetized and the distance of the trunk from the site of deposition, which is 5 to 10 mm. However, another main advantage is that the injection also lasts longer than the IA block because the area of the injection is less vascular and a larger volume of anesthetic may be necessary. This injection is contraindicated in cases with limited ability to open the mouth, but trismus is rarely involved.

1. An extraoral hematoma can result from an INCORRECTLY administered posterior superior alveolar local anesthetic block because the needle was overinserted and penetrated which of the following?

2. Which of the following local anesthetic blocks has the SAME injection site as the incisive local anesthetic block?

3. Which of the following nerves is NOT anesthetized during an IA local anesthetic block?

4. Which of the following local anesthetic blocks uses pressure anesthesia of the tissue to reduce patient discomfort?

5. Which of the following are usually anesthetized during an infraorbital local anesthetic block?

A Bilateral anterior hard palate

B Buccal periodontium of maxillary molars

C Upper lip, side of nose, and lower eyelid

6. If the mesiobuccal root of the maxillary first molar is NOT anesthetized by a posterior superior alveolar local anesthetic block, the dental professional should administer a

7. Which of the following is an important landmark to locate before performing an inferior alveolar local anesthetic block?

8. The injection site for the greater palatine local anesthetic block is usually located on the palate near which of the following?

9. If an extraction of a permanent maxillary lateral incisor is scheduled, which of the following local anesthetic blocks can be administered instead of the infraorbital block?

10. Transient facial paralysis can occur with which INCORRECTLY administered local anesthetic block?

11. Which local anesthetic block anesthetizes the largest intraoral area?

12. Which of these situations can occur if bone is contacted early during an inferior alveolar local anesthetic block?

A Needle tip is located too far anteriorly on the ramus

B Needle tip is located too far posteriorly on the maxillary tuberosity

13. In which of the following locations is the outcome MOST successful when using local infiltrations of local anesthetic?

A Facial surface of anterior maxilla

B Facial surface of posterior maxilla

14. If working within the mandibular anterior sextant, which local anesthetic block is MOST successful and comfortable for the patient?

15. Which of the following local anesthetic blocks anesthetizes the buccal tissue of the mandibular molars?

16. The mental foramen is usually located between the apices of which of the following mandibular teeth?

17. To have complete anesthesia of the maxillary quadrant, which of the following local anesthetic blocks needs to be administered along with the anterior middle superior alveolar block?

18. Which of the following can serve as a landmark for the anterior middle superior alveolar local anesthetic block?

19. Which of the following is considered a mandibular local anesthetic block because it anesthetizes MOST of the mandibular nerve?

20. Which of the following landmarks are noted when administering a Gow-Gates mandibular local anesthetic block?