Fasciae and Spaces

1 Define and pronounce the key terms and anatomic terms in this chapter.

2 Locate and identify the fasciae of the head and neck on a diagram, skull, and patient.

3 Locate and identify the major spaces of the head and neck on a diagram, skull, and patient.

4 Discuss the communication between the major spaces of the head and neck.

5 Correctly complete the review questions and activities for this chapter.

6 Integrate an understanding of fasciae and spaces into the overall study of head and neck anatomy as well as a clinical dental practice.

Fasciae and Spaces Overview

Fascia (plural, fasciae) consists of layer upon layer of fibrous connective tissue. The fascia lies underneath the skin and surrounds the muscles, bones, vessels, nerves, organs, and other structures.

Potential spaces are created between the layers of fascia of the body because of the sheetlike nature of fasciae. These potential spaces are termed fascial spaces or fascial planes. It is important to remember that these fascial spaces are not actually empty spaces as they contain loose connective tissue. Other spaces are also present in the head but not necessarily created by fasciae but by other structures such as by bones and muscles; both types of spaces are considered in this chapter.

Thus this chapter discusses the fasciae of the face and neck that surround both superficial and deep structures. Potential spaces created between the body’s layers of fasciae are also discussed, as well presenting as a three-dimensional view of the systems and structures of the head and neck for a more thorough understanding of these anatomic regions (see Chapter 1).

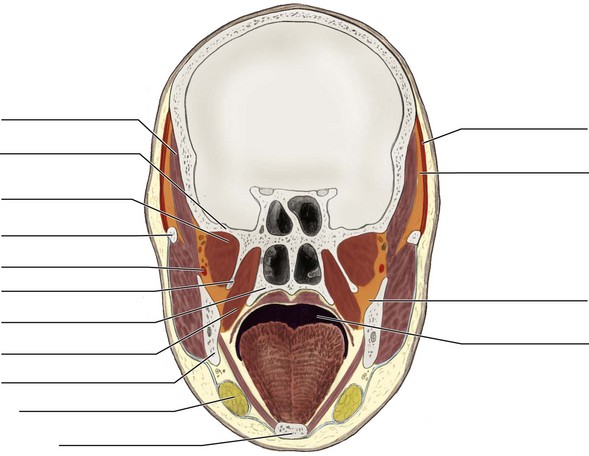

Fasciae of Head and Neck

In all areas of the body including the head and neck, the fasciae can be divided into either the superficial fasciae or the deep fasciae. Layers of superficial fascia are found just deep to and attached to the skin. In most cases, the layers of superficial fascia separate skin from deeper structures, allowing the skin to move independently of these deeper structures. The layers of superficial fascia vary in thickness in different parts of the body and are composed of fat as well as irregularly arranged connective tissue. The vessels and nerves of the skin also travel in the superficial fascia, many of the larger ones already discussed in previous chapters.

In contrast, the layers of deep fascia cover the deeper structures of the body including the head and neck such as the bones, muscles, vessels, and nerves. Again, many of these structures have been already discussed in previous chapters. These layers of fascia consist of a dense and inelastic fibrous tissue forming sheaths around these deeper structures.

Superficial Fasciae of Face and Neck

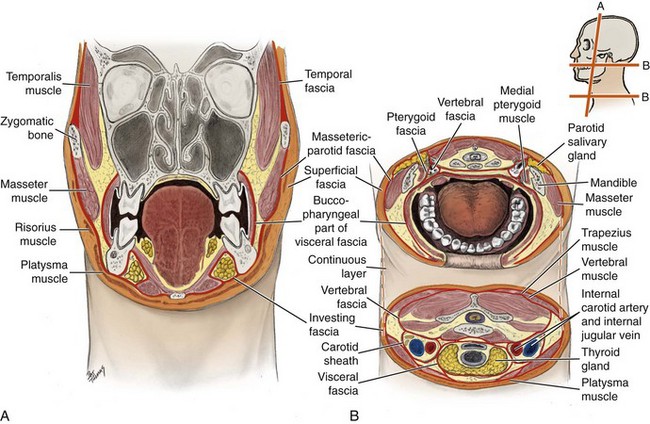

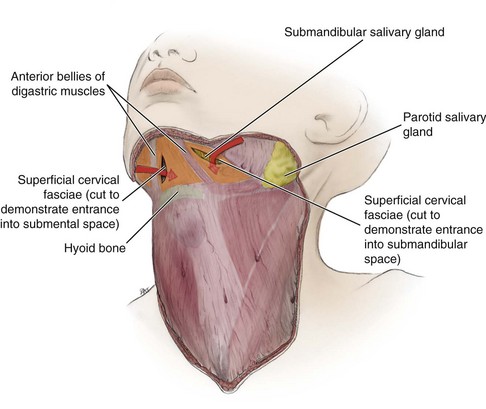

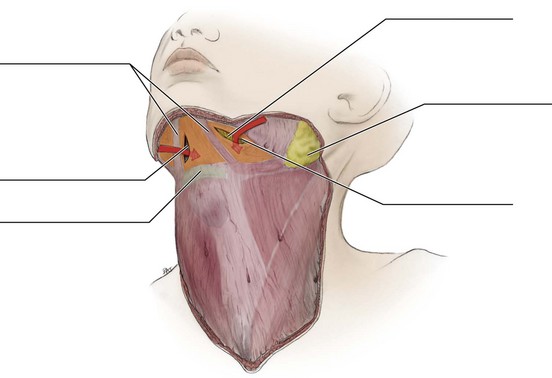

The layers of superficial fasciae of the body do not usually enclose muscles, except for the superficial fasciae of the face and neck (Figure 11-1). The superficial fascia of the face encloses the muscles of facial expression (see Figure 4-5). The superficial cervical fascia of the neck contains the platysma muscle, which covers most of the anterior cervical triangle (see Figures 2-23 and 4-17 ).

Deep Fasciae of Face and Jaws

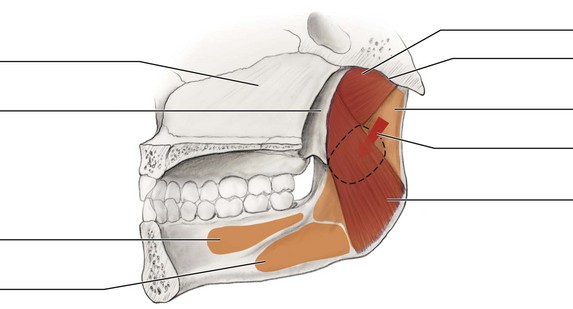

The layers of deep fasciae of the face and jaws are divided into the temporal, the masseteric-parotid, and the pterygoid, which are continuous with each other and with the deep cervical fasciae discussed next (see Figure 11-1).

The temporal fascia (tem-poh-ral) covers the temporalis muscle and structures superior to the zygomatic arch. The masseteric-parotid fascia (mass-et-tehr-ik-pah-rot-id) covers the masseter muscle and structures inferior to the zygomatic arch, surrounding the parotid salivary gland. The pterygoid fascia (ter-i-goid) is located on the medial surface of the medial pterygoid muscle. These fasciae are all continuous with the investing layer of the deep cervical fascia.

Deep Cervical Fasciae

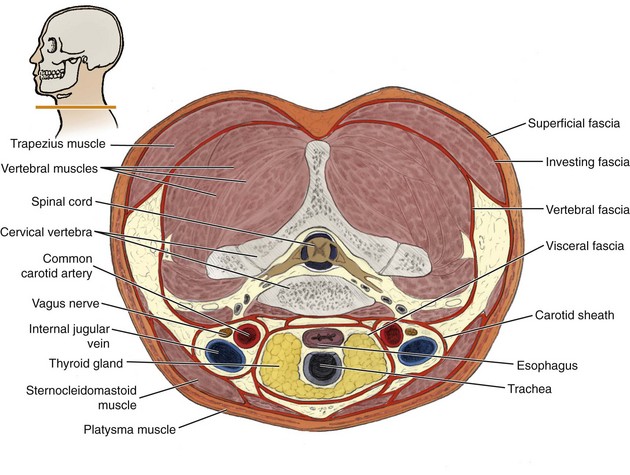

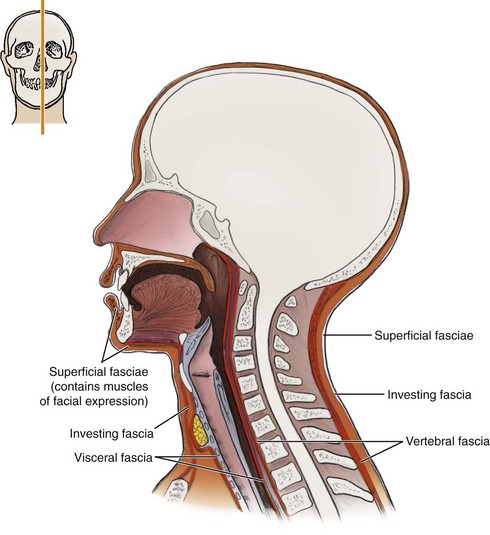

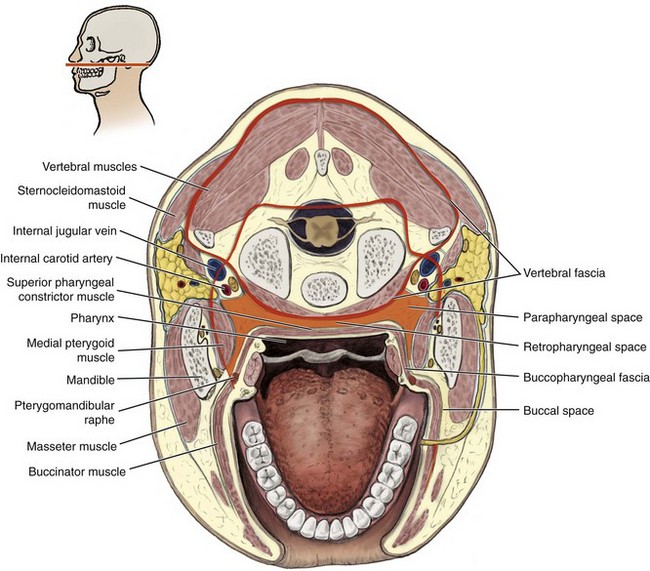

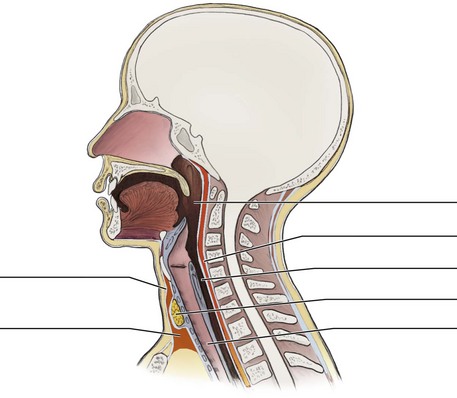

The layers of deep cervical fasciae include the investing fascia, the carotid sheath, the visceral fascia, buccopharyngial fascia, and the vertebral fascia (Figures 11-2 and 11-3; see Chapter 3). Again, it is important to note that the layers of the various regions of deep cervical fasciae are continuous with each other and also with the deep fasciae of the face and jaws.

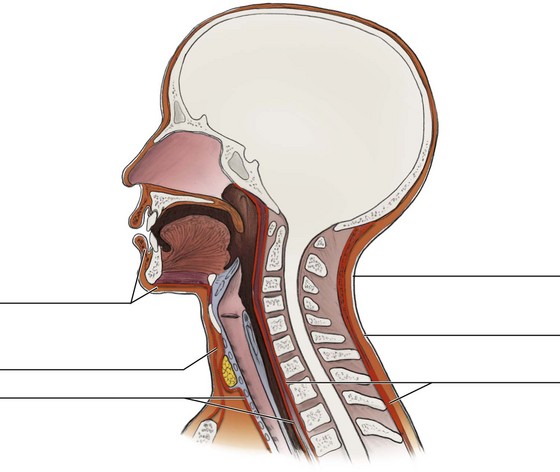

FIGURE 11-2 Midsagittal section of the head and neck (see inset) highlighting the deep cervical fasciae.

Investing Fascia

The investing fascia is the most external layer of deep cervical fascia. This fascia surrounds the neck, continuing onto the masseteric-parotid fascia. This fascia also splits around two salivary glands (submandibular and parotid) and two muscles (sternocleidomastoid and trapezius), enclosing them completely. Branching laminae from this fascia also provide the deep fasciae that surround the infrahyoid muscles, from the hyoid bone inferiorly to the sternum.

Carotid Sheath with Visceral and Buccopharyngeal Fasciae

The carotid sheath (kah-rot-id) is a tube of deep cervical fascia deep to the investing fascia and sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM), running inferiorly along each side of the neck from the base of the skull to the thorax. This sheath contains the internal carotid and common carotid arteries and the internal jugular vein, as well as the tenth cranial or vagus nerve. All these structures travel between the braincase and thorax.

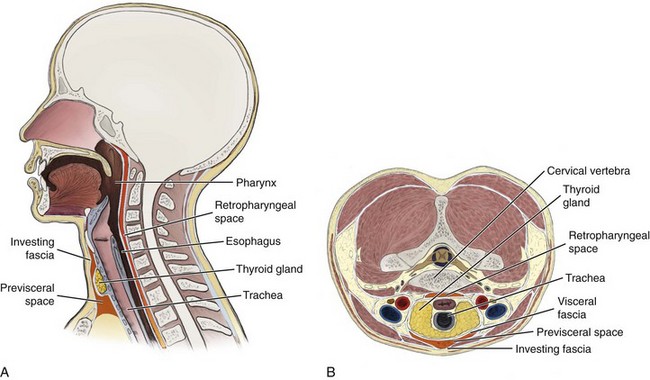

Deep and parallel to the carotid sheath is the visceral fascia (vis-er-al) or pretracheal fascia, which is a single, midline tube of deep cervical fascia running inferiorly along the neck. This fascia surrounds the air and food passageway including the trachea, esophagus, and thyroid gland.

Nearer to the skull, the visceral fascial layer located posterior and lateral to the pharynx is known as the buccopharyngeal fascia (buk-o-fah-rin-je-al). This deep cervical fascia encloses the entire superior part of the alimentary canal and is continuous with the fascia covering the buccinator muscle, where that muscle and the superior pharyngeal constrictor muscle come together at the pterygomandibular raphe (see Figure 4-29).

Vertebral Fascia

The deepest layer of the deep cervical fascia, the vertebral fascia (ver-teh-brahl) or prevertebral fascia, covers the vertebrae, spinal column, and associated muscles. Some anatomists distinguish a separate layer of the vertebral fascia, called the alar fascia, which runs from the base of the skull to connect with the visceral fascia inferiorly in the neck.

Spaces of Head and Neck

A dental professional must have an understanding of the anatomic aspects of the spaces of the head and neck when examining a patient. These spaces communicate with each other directly, as well as through their blood and lymph vessels contained within. Thus communication may allow the spread of dental or odontogenic infection from an initial superficial area in the face and jaws to more vital deeper structures in the neck or even brain. The spread of infection by way of these spaces may have serious consequences; the role of spaces in the spread of dental or odontogenic infection is discussed further in Chapter 12. Again, the study of these spaces also allows the clinician to form a three-dimensional view of head and neck anatomy (see Chapter 1).

Spaces of Face and Jaws

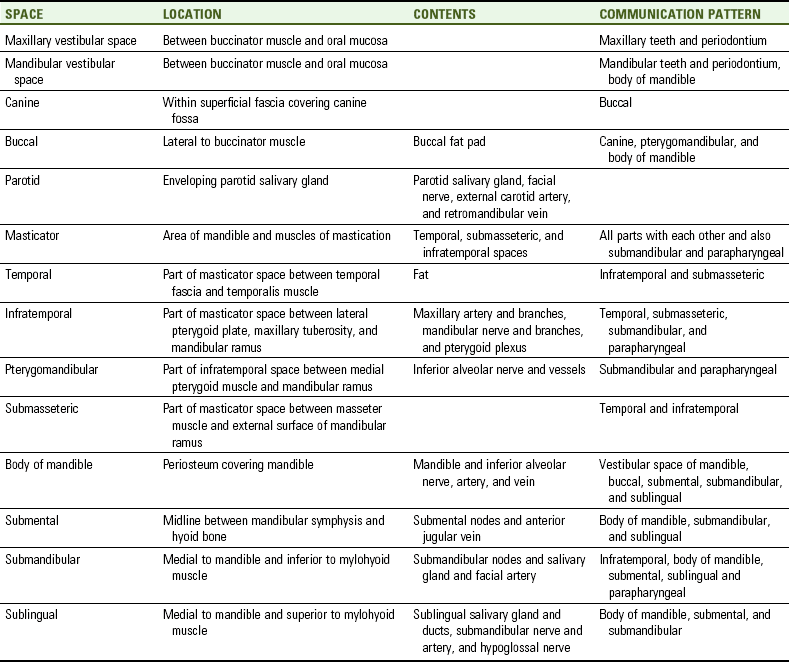

The spaces of the face and jaws can communicate with each other and with the cervical fascial spaces (see earlier discussion). However, unlike the neck, the spaces of the face and jaws are often defined by the arrangement of muscles and bones forming boundaries, in addition to the surrounding fasciae. Thus many of the major spaces located in the head are not strictly considered fascial spaces. The major spaces of the face and jaws include: the maxilla, mandible, canine, parotid, buccal, masticator, body of the mandible, submental, submandibular, and sublingual spaces (Table 11-1).

Vestibular Space of the Maxilla

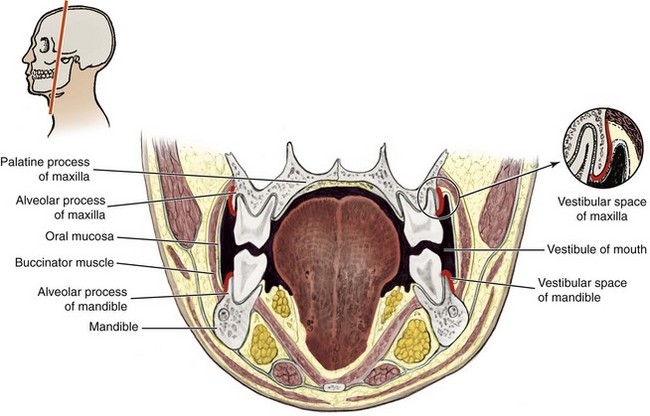

The space of the upper jaw, the vestibular space of the maxilla (mak-sil-ah), is located medial to the buccinator muscle and inferior to the attachment of this muscle along the alveolar process of the maxilla (Figure 11-4). Its lateral wall is the oral mucosa. This space communicates with the maxillary molar teeth and periodontium and thus can become involved with infections of this tissue.

Vestibular Space of the Mandible

The vestibular space of the mandible (man-di-bl) is located between the buccinator muscle and overlying oral mucosa (see Figure 11-4). This space is bordered by the attachment of the buccinator muscle onto the mandible. This important space of the lower jaw communicates with the mandibular teeth and periodontium, as well as the space of the body of the mandible.

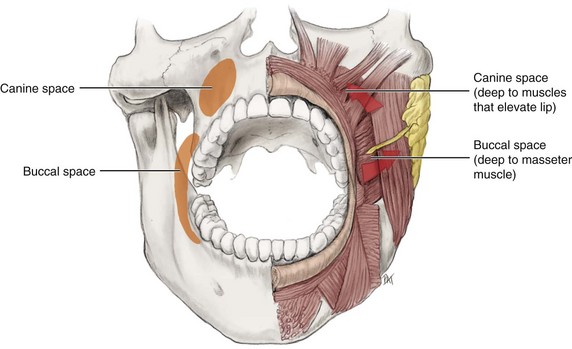

Canine Space

The canine space (kay-nine) is located superior to the upper lip and lateral to the apex of the maxillary canine (Figure 11-5). This space is deep to the overlying skin and muscles of facial expression that elevate the upper lip (levator labii superioris and zygomaticus minor) (see Figure 4-13). The floor of the space is the canine fossa, which is covered by periosteum (see Figure 3-47). This space is bordered anteriorly by the orbicularis oris muscle and posteriorly by the levator anguli oris muscle (see Figure 4-10). The canine space communicates with the buccal space. If involved in infection, the source is usually the maxillary canine and there is unilateral loss of the depth to the nasolabial sulcus (see Table 12-1 and Figure 2-7).

Buccal Space

The buccal space is the fascial space formed between the buccinator muscle (actually the buccopharyngeal fascia) and masseter muscle (see Figure 11-5). Therefore the buccal space is inferior to the zygomatic arch, superior to the mandible, lateral to the buccinator muscle, and medial and anterior to the masseter muscle.

This bilateral space is partially covered by the platysma muscle, as well as by an extension of fascia from the parotid salivary gland capsule (see Figure 4-17). The space contains the buccal fat pad (see Figure 2-12). The buccal space communicates with the canine space, pterygomandibular space, and space of the body of the mandible. If involved in infection, the source is usually either a maxillary or mandibular molar or premolar appearing similar to the cartoon of a wrapped swollen cheek due to a toothache (see Figure 12-6 and Table 12-1).

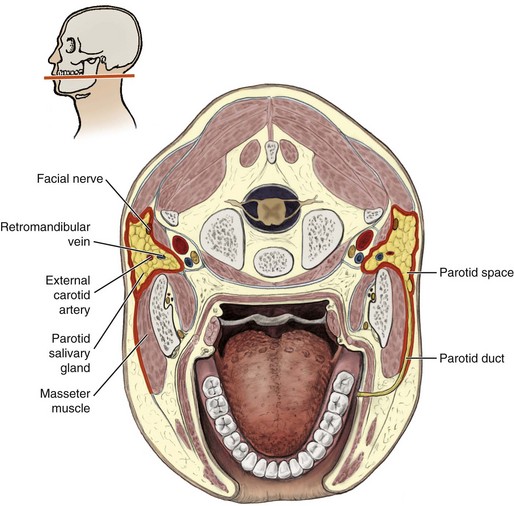

Parotid Space

The parotid space (pah-rot-id) is a fascial space created inside the investing fascial layer of the deep cervical fascia as it envelops the parotid salivary gland (Figure 11-6 and see Figure 7-2). The space contains not only the entire parotid salivary gland but also much of the seventh cranial or facial nerve and a part of the external carotid artery and retromandibular vein. The fascial boundaries of this space help to keep pathology associated with the parotid salivary gland (such as cancer) from spreading to other sites.

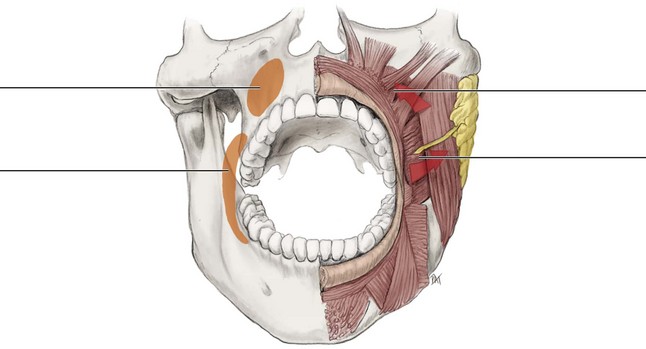

Masticator Space

The masticator space (mass-ti-kay-tor) is a general term used to include the entire area of the mandible and muscles of mastication (see Figures 4-19 to 4-23 ). Thus it includes the temporal, infratemporal, and submasseteric spaces, as well as the masseter muscle and both ramus and body of the mandible. All parts of the masticator space communicate with each other, as well as with the submandibular space and a cervical fascial space, the parapharyngeal space (discussed later).

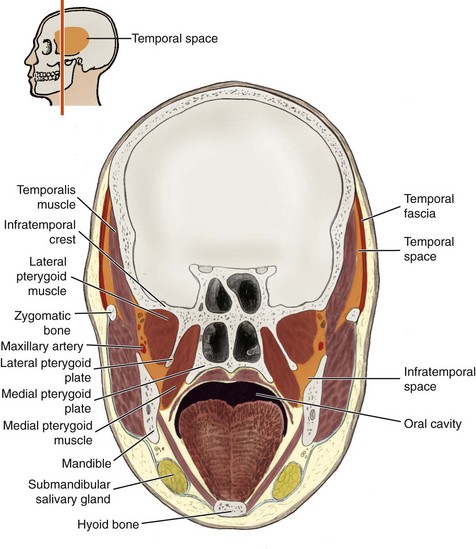

A part of the masticator space is the temporal space (tem-poh-ral), which is formed by the temporal fascia anterior to the temporalis muscle (Figure 11-7; see Figure 3-59). This space is between the fascia and muscle and therefore extends from the superior temporal line inferiorly to the zygomatic arch and infratemporal crest. The space contains fat tissue and communicates with the infratemporal and submasseteric spaces. If involved in infection, the source usually involves other masticator fascial spaces.

FIGURE 11-7 Frontal section of the head (see inset) highlighting both the temporal space and infratemporal space.

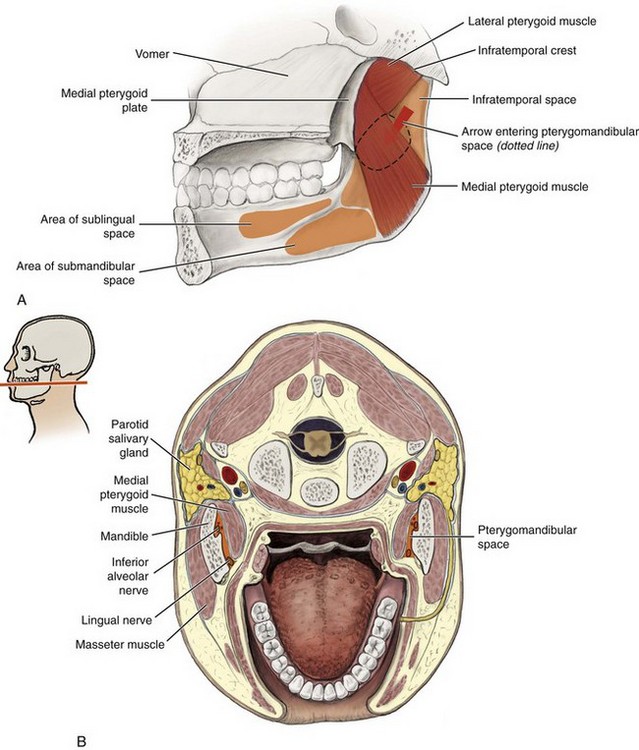

The infratemporal space (in-frah-tem-poh-ral) is also part of the masticator space and occupies the infratemporal fossa, an area adjacent to the lateral pterygoid plate of the sphenoid bone and maxillary tuberosity of the maxilla (Figure 11-8, A; see Figures 11-7 and Figure 3-61). The space is bordered laterally by the medial surface of the mandible and the temporalis muscle. Its roof is formed by the infratemporal surface of the greater wing of the sphenoid bone. Medially, the space is bordered anteriorly by the lateral pterygoid plate and posteriorly by the pharynx with its visceral layer of deep fascia. There is no boundary inferiorly and posteriorly, where the infratemporal space is continuous with a more inferior and deep cervical fascial space, the parapharyngeal space (discussed later).

FIGURE 11-8 A, Median section of the skull highlighting the infratemporal space and pterygomandibular space. B, Transverse section of the head and neck (see inset) highlighting the pterygomandibular space.

The infratemporal space contains a part of the maxillary artery as it branches, the mandibular nerve and its branches, and the pterygoid plexus of veins. It also contains the medial and lateral pterygoid muscles. This space communicates with the temporal and submasseteric spaces, as well as with the submandibular and parapharyngeal spaces. If involved in infection, the source is usually a maxillary third molar (see Table 12-1 and Figure 12-11).

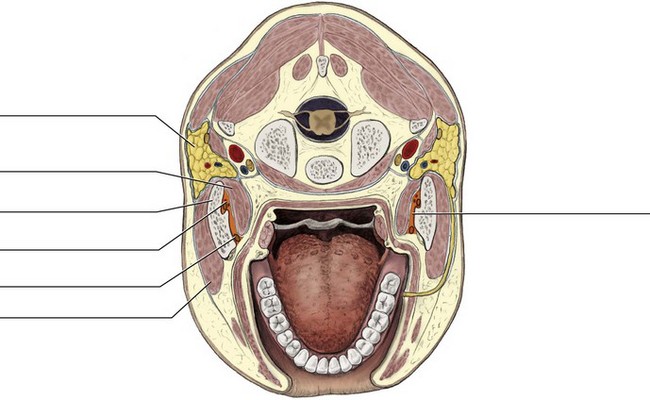

The pterygomandibular space (ter-i-go-man-dib-you-lar) is a part of the infratemporal space, and is formed by the lateral pterygoid muscle (roof), medial pterygoid muscle (medial wall), and mandibular ramus (lateral wall) (see Figure 11-8).

The pterygomandibular space is important to dental professionals because it contains the inferior alveolar nerve and vessels and is a landmark for the inferior alveolar block (see Figure 9-37). This space communicates with both the submandibular space and the parapharyngeal space of the neck (discussed later). If involved in infection, the source is usually either a mandibular molar or premolar, with trismus possible (see Table 12-1 and Chapter 5).

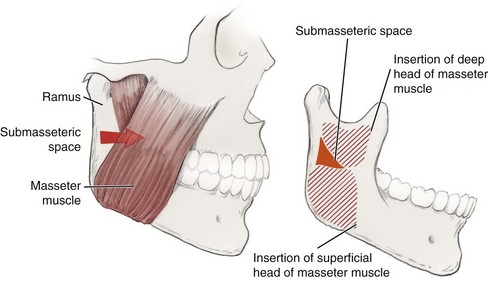

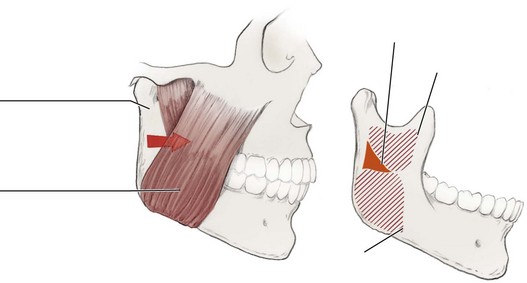

Another part of the masticator space, the submasseteric space (sub-mas-et-tehr-ik), is located between the masseter muscle and the external surface of the vertical mandibular ramus (Figure 11-9). This space communicates with both the temporal and infratemporal spaces. If involved in infection, the source is usually either a mandibular third molar, with swelling noted at the angle of the mandible with trismus possible (see Table 12-1 and Figure 2-9).

Space of the Body of the Mandible

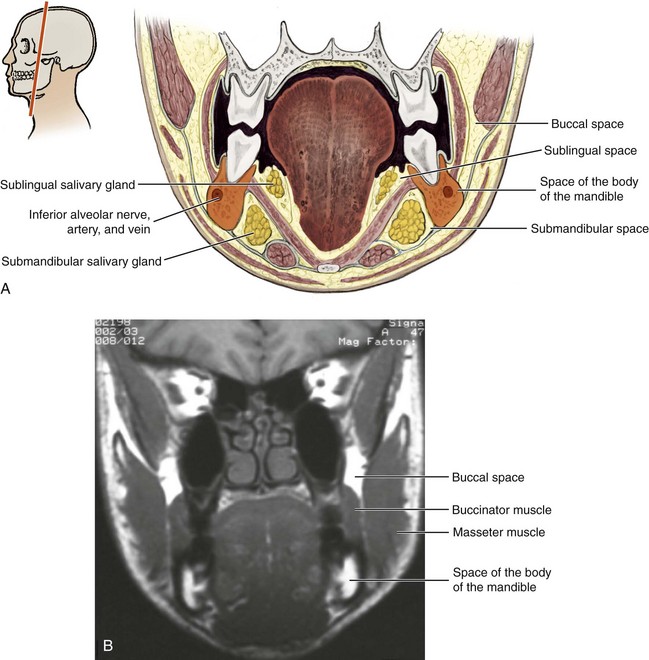

The space of the body of the mandible is formed by the periosteum, anterior to the body of the mandible from its symphysis to the anterior borders of the masseter and medial pterygoid muscles (Figure 11-10).

FIGURE 11-10 Frontal section of the head and neck (see inset). A, Highlighting the space of the body of the mandible; B, MRI. (From Reynolds PA, Abrahams PH: McMinn’s interactive clinical anatomy: head and neck, ed 2, London, 2001, Mosby Ltd.)

This potential space contains the mandible; a part of the inferior alveolar nerve, artery, and vein; and the dental and alveolar branches of these vessels, as well as the mental and incisive branches. The space of the mandible communicates with the vestibular space of the mandible, as well as with the buccal, submental, submandibular, and sublingual spaces.

Submental Space

The submental space (sub-men-tal) is located in the midline between the mandibular symphysis and hyoid bone (Figure 11-11). The floor of this space is the superficial cervical fascia covering the suprahyoid muscles. The roof is the mylohyoid muscle, covered by the investing fascia. Forming the lateral boundaries of this space are the diverging anterior bellies of the digastric muscles.

FIGURE 11-11 Anterolateral view of the neck with the skin removed, leaving the superficial cervical fasciae in place (platysma has been omitted). Location of both the submental space at the midline and the two lateral submandibular spaces is indicated.

The submental space contains the submental lymph nodes and the origin of the anterior jugular vein (see Figure 10-10). The space communicates with the space of the body of the mandible and the submandibular and sublingual spaces. If involved in infection, the source is usually the mandibular incisors (see Table 12-1).

Submandibular Space

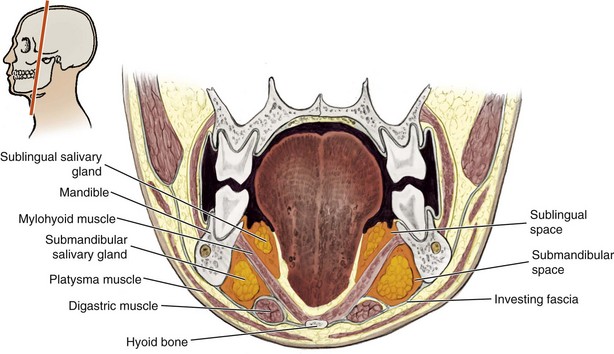

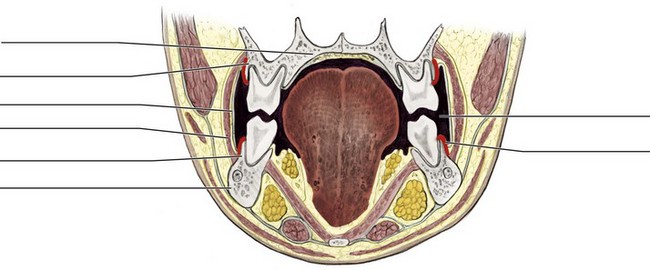

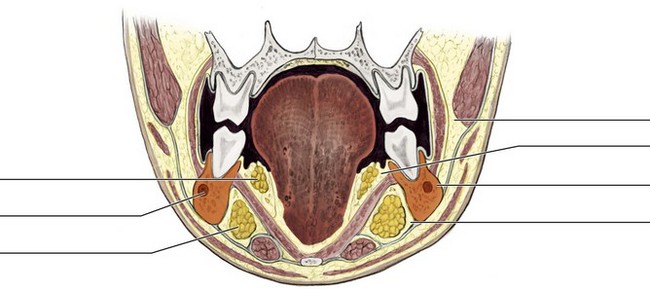

The submandibular space (sub-man-dib-you-lar) is located lateral and posterior to the submental space on each side of the jaws (Figure 11-12; see Figure 11-11). The cross-sectional shape of this bilateral space is triangular, with the mylohyoid line of the mandible being its superior boundary. The mylohyoid muscle forms the medial, as well as the superior boundary of the space, and the hyoid bone creates its medial apex.

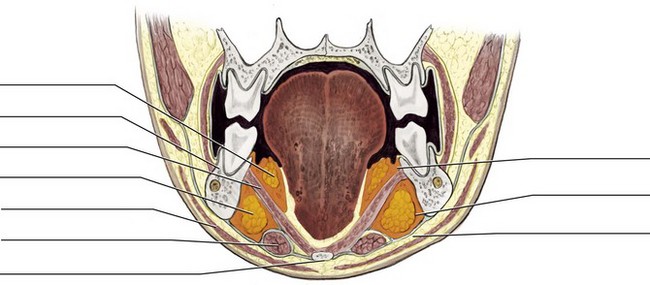

FIGURE 11-12 Frontal section of the head and neck (see inset) highlighting both the submandibular space and sublingual space.

The submandibular space contains the submandibular lymph nodes, most of the submandibular salivary gland, and parts of the facial artery (see Figures 7-5 and 10-10 ). This space communicates with the infratemporal, submental, and sublingual spaces and the parapharyngeal space of the neck (discussed later). If involved in infection, the source is usually either a mandibular molar or premolar with possible loss of the firmness of the inferior border of the mandible upon palpation (see Table 12-1). This space is also becomes involved if there is a spread of dental or odontogenic infection, which may result in the serious complication of Ludwig angina (see Figure 12-12).

Sublingual Space

The sublingual space (sub-ling-gwal) is located deep to the oral mucosa, thus making this tissue its roof (see Figure 11-12). The floor of this space is the mylohyoid muscle; thus this muscle creates the division between the submandibular and sublingual spaces with the sublingual space superior to the more inferior submandibular space. The tongue and its intrinsic muscles form the medial boundary of the sublingual space, and the mandible forms its lateral wall.

The sublingual space contains the sublingual salivary gland and ducts, the duct of the submandibular salivary gland, a part of the lingual nerve and artery, and the twelfth cranial or hypoglossal nerve (see Figure 7-7). The space communicates with the submental and submandibular spaces and the space of the body of the mandible. If involved in infection, the source is usually either a mandibular molar or premolar, which may result in only a swelling of the floor of the mouth but without anything visible or palpable extraorally during examination (see Table 12-1).

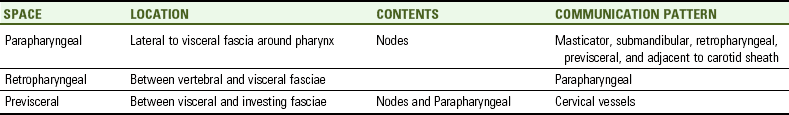

Cervical Spaces

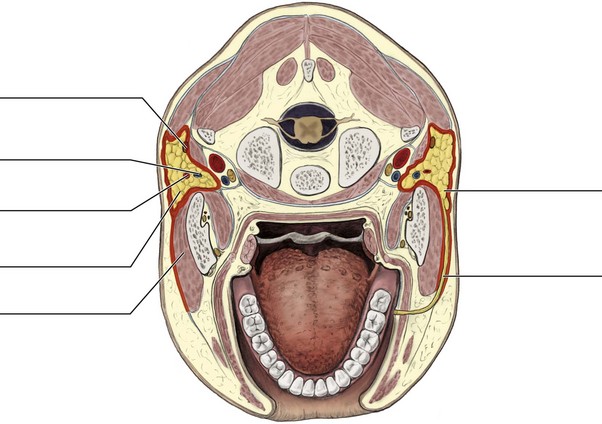

The cervical spaces can communicate with the spaces of the face and jaws, as well as with each other. Most importantly, these spaces connect the spaces of the face and jaws with those of the thorax, allowing dental or odontogenic infection to spread to vital organs such as the heart and lungs as well as the brain (see Chapter 12). The cervical spaces include the parapharyngeal, retropharyngeal, and previsceral spaces (Figures 11-13 and 11-14; Table 11-2).

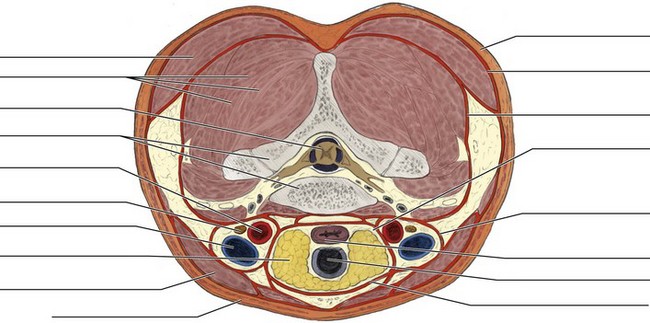

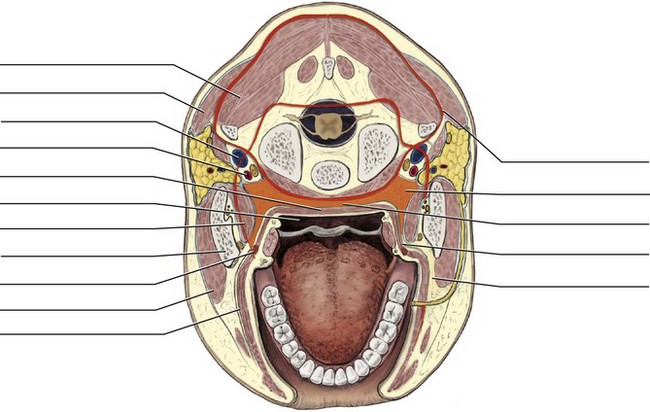

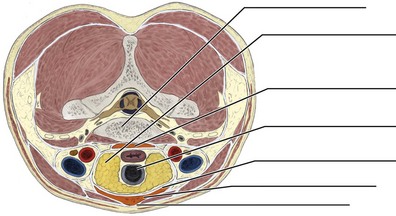

FIGURE 11-13 Transverse section of the oral cavity and neck (see inset) highlighting both the parapharyngeal space and retropharyngeal space.

FIGURE 11-14 A, Midsagittal section of the head and neck highlighting both the retropharyngeal space and previsceral space. B, Transverse section of the neck.

Parapharyngeal Space

The parapharyngeal space (pare-ah-fah-rin-je-al) or lateral pharyngeal space is a fascial space lateral to the pharynx and medial to the medial pterygoid muscle, parallel to the carotid sheath. The bilateral parapharyngeal space in its posterior part is adjacent to the carotid sheath, which contains the internal and common carotid arteries and the internal jugular vein, as well as the tenth cranial or vagus nerve. It is also adjacent to the ninth, eleventh, and twelfth cranial nerves as they exit the cranial cavity.

Anteriorly, the parapharyngeal space extends to the pterygomandibular raphe, where it is continuous with the infratemporal and buccal spaces. The parapharyngeal space anteriorly contains a few lymph nodes. Posteriorly, the space extends around the pharynx, where it is continuous with another cervical fascial space, the retropharyngeal space. Dental or odontogenic infections can become serious when they reach the parapharyngeal space because of its connection to the retropharyngeal space.

Retropharyngeal Space

The retropharyngeal space (re-troh-fah-rin-je-al) or retrovisceral space is a fascial space located immediately posterior to the pharynx, between the vertebral and visceral fasciae. The retropharyngeal space extends from the base of the skull, where it is posterior to the superior pharyngeal constrictor muscle, inferior to the thorax. This space communicates with the parapharyngeal spaces.

Because of the rapidity with which dental or odontogenic infections can travel inferiorly along the retropharyngeal space to the thorax, it can also be known as the “danger space” of the neck by dental professionals (see Chapter 12).

Identification Exercises

Identify the structures on the following diagrams by filling in each blank with the correct anatomic term. You can check your answers by looking back at the figure indicated in parentheses for each identification diagram.

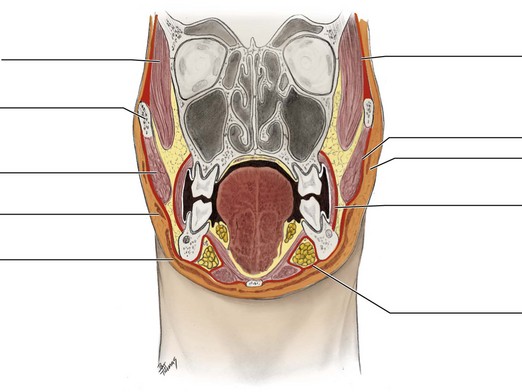

1. (Figure 11-1, A)

2. (Figure 11-1, B)

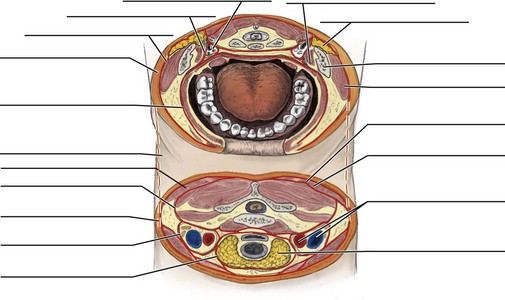

3. (Figure 11-2)

4. (Figure 11-3)

5. (Figure 11-4)

6. (Figure 11-5)

7. (Figure 11-6)

8. (Figure 11-7)

9. (Figure 11-8, A)

10. (Figure 11-8, B)

11. (Figure 11-9)

12. (Figure 11-10, A)

13. (Figure 11-11)

14. (Figure 11-12)

15. (Figure 11-13)

16. (Figure 11-14, A)

17. (Figure 11-14, B)

1. Which of the following statements CORRECTLY describes the deep fasciae?

A Dense and inelastic tissue forming sheaths around deep structures

B Fatty and elastic fibrous tissue found just deep to the skin

C Potential spaces containing loose connective tissue

D Fatty and elastic fibrous tissue forming spaces under the skin

E Dense and inelastic deep structures of the vascular system

2. Which of the following structures are located within the carotid sheath?

A Internal and common carotid arteries and tenth cranial nerve

B External and common carotid arteries and fifth cranial nerve

3. In which of the following spaces is the pterygoid plexus of veins located?

4. The masticator space includes the submasseteric space and which other space?

5. Which of the following tissue types surround the space of the body of the mandible?

6. The submandibular space communicates MOST directly with which of the following spaces?

7. The parapharyngeal space is located between the superior pharyngeal constrictor muscle and

8. Which space is located in the midline between the mandibular symphysis and the hyoid bone?

9. Which of the following nerves is located in the pterygomandibular space?

10. Which of the following areas MOST directly communicates with the retropharyngeal space?

11. Which of the following muscles forms the roof of the pterygomandibular space?

12. Which of the following blood vessels is located in the sublingual space?

13. Which of the following spaces is considered a “danger space” by dental professionals?

14. Which of the following fascial structures are also considered part of the deep fasciae of the face?

15. Which of the following structures are located in the superficial fasciae of the head and neck?