The Occupational Therapy Practice Framework and the Practice of Occupational Therapy for People with Physical Disabilities

After studying this chapter, the student or practitioner will be able to do the following:

1 Briefly describe the history of the evolution of the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework, both the original OTPF and OTPF-2.

2 Describe the need for the OTPF-2 in the practice of occupational therapy (OT) for persons with physical disabilities.

3 Describe the fit between the OTPF-2 and the International Classification of Function and Disability (ICF) and how they inform and enhance the occupational therapist’s understanding of physical disability.

4 Describe the elements of the OTPF-2, including domain and process and the relationship of each to the other.

5 List and describe the components that make up the occupational therapy domain, and give examples of each.

6 List and describe the components that make up the occupational therapy process, and give examples of each.

7 Briefly describe the occupational therapy intervention levels, and give an example of each as it might be used in a physical disability practice setting.

The Occupational Therapy Practice Framework, Second Edition: Overview

Many changes have occurred in the practice of occupational therapy (OT) for persons with physical disabilities since the publication of the previous edition of Occupational Therapy: Practice Skills for Physical Dysfunction in 2006. Occupational therapy practice settings are increasingly moving away from traditional healthcare environments, such as the hospital and rehabilitation center, and have made significant strides moving more toward the home and community milieu. The provision of occupational therapy service has become more client centered and the concept of occupation is increasingly and proudly named as both the preferred intervention and the desired outcome of the services. Clinicians, researchers, and scholars have sought to implement evidence-based practice by learning more about the benefits of occupation to not only remediate problems after the onset of physical disability but also to anticipate and prevent physical disability and promote wellness. Not surprisingly, economic concerns have severely shortened the amount of time allotted for OT services, thus necessitating more deliberate and resourceful decisions about how these services can most effectively be delivered.

In response to these changes, and many other practice advances, came a change, or evolution, in the language with which occupational therapists describe what they do and how they do it. This change resulted in a document called the “Occupational Therapy Practice Framework” (OTPF) and the now updated second edition (OTPF-2), a tool developed by the profession to more clearly articulate and enhance the understanding of what OT practitioners do (occupational therapy domain) and how they do it (occupational therapy process). The intended beneficiaries of the OTPF and OTPF-2 were envisioned as including not only OT practitioners (an internal audience) but also the recipients of OT services (called clients), other healthcare professionals, and those providing reimbursement for OT services (comprising an external audience).

The OTPF was developed, resulting in the “Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process,”1 which was published in the American Journal of Occupational Therapy (AJOT) in 2002. This initial iteration of the Framework was put to practice and its relevance and efficacy assessed resulting in the now updated OTPF-2, which was developed and thoroughly articulated in the “Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process,” Second Edition,2 which was published in the AJOT in 2008. This is an important document every OT practitioner will want to have and reference frequently. It can be downloaded from the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) website by selecting AJOT Online and the November/December 2008 issue. Another helpful tool for learning the OTPF is the original introductory article in the November/December 2002 issue of the AJOT by Youngstrom titled “The Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: The Evolution of Our Professional Language.”22

It is not the intention of this chapter to supplant the comprehensive OTPF-2 document but, rather, to describe and increase the reader’s understanding of the OTPF-2 and its relationship to the practice of occupational therapy with adults who have physical disabilities. To achieve this, the chapter begins with a discussion of the history of the OTPF-2 followed by sections describing the need for the OTPF-2 and the fit between the OTPF-2 and the World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Classification of Function and Disability (ICF). Next, a detailed description of the Framework II is presented with emphasis on fully explicating the domain of occupational therapy through examples from the case study and introducing the occupational therapy process, which will be discussed more thoroughly in Chapter 3 on application of the OTPF to physical dysfunction. The types of occupational therapy intervention proposed by the Framework II are examined and illustrated by examples typically employed in physical disabilities practice settings. The chapter concludes with suggestions and strategies for learning the OTPF-2 and an overview of how the Framework II is integrated as a unifying thread throughout the remaining chapters in the book.

History of the Evolution of the OTPF

In 1999, the Commission on Practice (COP) of the AOTA was charged with reviewing the “Uniform Terminology for Occupational Therapy,” Third Edition (UT-III).3 Under the leadership of its chair, Mary Jane Youngstrom, the COP sought feedback from numerous and varied OT practitioners, scholars, and leaders in the profession regarding the continued suitability of the UT-III to determine whether to update the document or to rescind it. Previous editions of the UT in 1979 and 1989 had been similarly reviewed and updated to reflect the changes and evolving progress of the profession. The reviewers found that the UT-III, though considered a valuable tool for occupational therapists, was lacking in clarity for both consumers and professionals regarding what occupational therapists do and how they do it. Furthermore, they found that the UT-III did not adequately describe or emphasize OT’s focus on occupation, the foundation of the profession.

Given the feedback from the review, the COP determined the need for a new document that would preserve the intent of the UT-III (outlining and naming the constructs of the profession) while providing increased clarity about what occupational therapists and occupational therapy assistants do and how they do it. Additionally, it was determined that this new document would refocus attention to the primacy of occupation as the cornerstone of the profession and desired intervention outcome as well as show the process occupational therapists use to help their clients achieve their occupational goals.

Need for the OTPF

The original OTPF and the revised OTPF 2 make it clear that the profession’s central focus and actions are grounded in the concept of occupation. Although some of what occupational therapists do could be construed by clients and other healthcare professionals as similar to or even duplication of the treatment efforts of other disciplines, formally delineating occupation as the overarching goal of all that OT does, and clearly documenting such goals, establishes the profession’s unique contribution to client intervention.

This is not to say that prior to the OTPF, OT practitioners did not recognize or focus on occupation or occupational goals with their clients—most did; but in the physical disabilities practice setting, with the reductionistic, bottom-up approach and pervasive influence of the medical model, occupation was seldom mentioned or linked to what was being done in OT. A premium seemed to be placed on “medical speak,” and it was difficult, if not impossible, to document occupational performance or occupational goals in the types of documentation that were characteristic of physical disabilities practice settings. Kent, the therapist from the case study, still occasionally experiences the medical team members’ heightened interest as he reports muscle grades and sensory status, contrasted with their quizzical, glazed-over looks when he describes his clients’ difficulties with resuming homemaking, leisure, or other home and community skills. The OTPF-2 provides a vehicle to communicate with others besides occupational therapists that engagement in occupation should be the primary outcome of all intervention.

The OTPF-2 provides a language and structure that communicates occupation more meaningfully. It empowers occupational therapists to restructure evaluation, progress, and other documentation forms to reflect the primacy of occupation to what OT does, and shows the interaction of all the aspects that contribute to supporting or constraining the client’s participation. Thus, by clearly showing and articulating the comprehensive nature of OT’s domain of practice to clients, healthcare professionals, and other interested parties, occupational therapists enlist support and demand for their services and, most important, ensure that clients will receive the unique and important services that only OT provides. Of equal importance is that the Framework II positions the client as a collaborator with the occupational therapist at every step of the process, thus empowering the individual as a change agent and reframing the image of the client as a passive recipient of services.

Fit between the OTPF-2 and the ICF

There appears to be an excellent fit between the OTPF-2 and the ICF. At about the same time the UT-III was being studied for continued suitability regarding contemporary language and practice, the WHO was also revising its language and classification model. The resulting WHO International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) contributes to the understanding of the complexity of having a physical disability.21 The ICF “moved away from being a ‘consequences of disease’ classification to become a ‘components of health’ classification” (p. 4),21 progressing from impairment, disability, and handicap to body functions and structures, activities, and participation. In the ICF, the term body structures refers to the anatomic parts of the body and body functions refers to a person’s physiologic and psychological functions. Also considered in this model is the impact of environmental and personal factors as they relate to functioning. The ICF adopted a universal model that considers health along a continuum where there is a potential for everyone to have a disability.

The ICF also provides support and reinforcement for OT to specifically address activity and activity limitations encountered by persons with disabilities.21 This document describes, as well, the importance of participation in life situations, or domains, including (1) learning and applying knowledge, (2) general tasks and task demands, (3) communication, (4) movement, (5) self-care, (6) domestic life areas, (7) interpersonal interactions, (8) major life areas associated with work, school, and family life, and (9) community, social, and civic life. All of these domains are historically familiar areas of concern and intervention to the profession of OT. Although a physical disability may compromise a person’s ability to reach up to brush his or her hair, the ICF redirects the service provider to also consider activity limitations that may result in restricted participation in desired life situations such as sports or parenting. A problem with a person’s bodily structure, such as paralysis or a missing limb, is recognized as a potentially limiting factor, but that is not the focus of intervention.

Occupational therapy practitioners believe that intervention provided for people with physical disabilities should extend beyond a focus on recovery of physical skills and address the person’s engagement, or active participation, in occupations. This viewpoint is the cornerstone of the Framework II. Such active participation in occupation is interdependent on the client’s psychological and social well-being, which must be simultaneously addressed through the occupational therapy intervention. This orientation is congruent with the emphasis of the WHO ICF.

The language of the UT-III was, in many instances, different from that used and understood by the external audience of other healthcare professionals. Similarly, the terminology of the previous WHO classification frequently differed from that used by the audience with whom the organization was trying to communicate (e.g., healthcare professionals and other service providers). The goals of the new WHO classifications, the ICF, are to increase communication and understanding about the experience of having a disability and unify services. In a similar manner, the original OTPF, and now the updated OTPF-2, was designed to increase the knowledge and understanding of the OT profession to others and, where appropriate, incorporate the language of the ICF, as will be seen in the following discussion of the OT domain and process. Detailed information on the ICF can be found in the document referenced in this chapter,21 or an overview of the document can be downloaded from www3.who.int/icf/cfm.

The OTPF-2: Description

The OTPF-2 is composed of two interrelated parts, the domain and the process. The domain comprises the focus and factors addressed by the profession, and the process describes how occupational therapy does what it does (evaluation, intervention, and outcomes)—in other words, putting the domain into practice. Central to both parts is the essential concept of occupation. The definition of occupation used by the developers of the original Framework is as follows:

Activities … of everyday life, named, organized, and given value and meaning by individuals and a culture. Occupation is everything people do to occupy themselves, including looking after themselves, … enjoying life, … and contributing to the social and economic fabric of their communities. (p. 32)13

In the revised Framework II, rather than adopting one definition, occupation is defined in the document as the numerous iterations presented in the OT literature. The committee charged with the revision of the OTPF ultimately suggest that an array of several selected definitions of occupation offered by the scholars of the profession add to an understanding of this core concept. These selected definitions can be found on pages 628-629.2

Adopting the essence of these definitions, the developers of the OTPF-2 represent or characterize the profession’s focus on occupation in a dynamic and action-oriented form, which they articulate as supporting health and participation in life through engagement in occupation. This phrase links both parts of the Framework II, providing the unifying theme or focus of the occupational therapy domain, as well as the overarching outcome of the occupational therapy process.

The Occupational Therapy Domain

The domain of occupational therapy encompasses the gamut of what occupational therapists do, along with the primary concern and focus of the profession’s efforts. Everything that the OT does or is concerned about, as depicted in the domain of the OTPF-2, is directed at supporting the client’s engagement in meaningful occupation that ultimately affects the health, well-being, and life satisfaction of that individual.

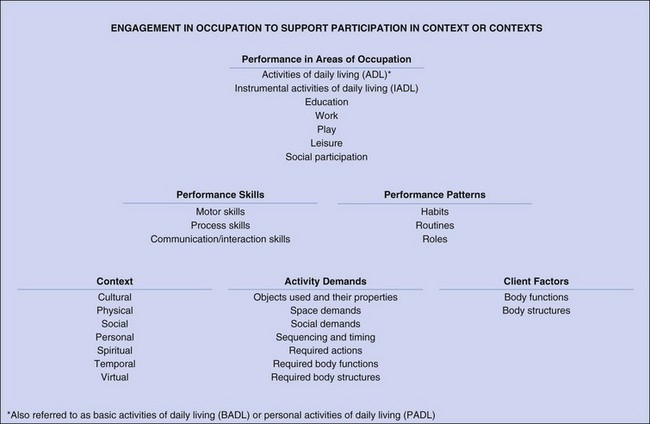

The six broad areas or categories of concern that constitute the occupational therapy domain include performance in areas of occupation, performance skills, performance patterns, context, activity demands, and client factors (Figure 1-1). The developers of the Framework point out that there is a complex interplay among all of these areas or aspects of the domain, that no single part is more critical than another, and that all aspects are viewed as influencing engagement in occupations. Furthermore, the success of the occupational therapy process (evaluation, intervention, and outcomes) is incumbent on the occupational therapist’s expert knowledge of all aspects of the domain.

FIGURE 1-1 Occupational therapy domain. (From American Occupational Therapy Association: Occupational therapy practice framework: domain and process, Am J Occup Ther 62(6):625-688, 2008.)

Performance in Areas of Occupation

Occupational therapists frequently use the terms occupation and activity interchangeably. Within the Framework II, the term occupation encompasses the term activity. Occupations may be characterized as being meaningful and goal directed but not necessarily considered by the individual to be of central importance to her or his life. Similarly, occupations may also be viewed as (1) activities in which the client engages, (2) activities that have the added qualitative criteria of giving meaning to the person’s life and contributing to one’s identity, and (3) activities in which the individual looks forward to engaging. For example, Karen, Kent’s client with quadriplegia, regards herself as an excellent and dedicated clothes and accessories shopper; holidays and celebrations always include her engagement in her treasured occupation of shopping. Kent, on the other hand, regards the activity of shopping for clothes as important only to keep himself clothed and maintain social acceptance. Kent avoids the activity whenever possible. Each engages in this activity to support participation in life but with a qualitatively different attitude and level of enthusiasm. Within the OTPF-2, both of these closely related terms are used, recognizing that individual clients will determine those that they regard as meaningful occupations and those that are simply necessary occupations or activities that support their participation in life; for Kent, shopping is a necessary occupation or activity, but for Karen, it is a favorite occupation.

Included in the areas of occupation category of the domain are eight comprehensive types of human activities or occupations. Each is outlined in the following discussion, with a listing of typical activities that are included in each and examples from the physical disability perspective as provided by Karen’s circumstances.

Activities of daily living (ADLs) (also referred to as personal activities of daily living [PADLs] or basic activities of daily living [BADLs]) are activities that have to do with accomplishing one’s own personal body care. The body care activities included in this category are bathing/showering, bowel and bladder management, dressing, eating, feeding, functional mobility, personal device care, personal hygiene and grooming, sexual activity, and toilet hygiene.

Instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) are “activities to support daily life within the home and community that often require more complex interactions than self-care used in ADL” (p. 631).2 The specific IADLs included in the domain are care of others (including selecting and supervising caregivers), care of pets, child rearing, communication management, community mobility, financial management, health management and maintenance, home establishment and management, meal preparation and cleanup, religious observance, safety and emergency maintenance, and shopping. Knowing that the IADL of shopping was certain to be a priority occupation for Karen, Kent made a note of the full description of shopping from the corresponding lists of IADLs in Table 1: Areas of Occupation of the OTPF-2 document. Shopping is described there as “Preparing shopping lists (grocery and other); selecting and purchasing items; selecting method of payment; and completing money transactions” (p. 631).2 This is not as detailed as some descriptions, but it is a good start for looking at the related activities that would have to be addressed if Kent and Karen were to collaborate on Karen’s resumption of engagement in shopping. Kent noted too that community mobility included driving and using public transportation, another IADL that would be important to explore with Karen as she contemplates returning to paid work. In fact, the entire list of IADLs held numerous concerns to be addressed in OT.

Rest and sleep, formerly considered a subcategory in the area of occupation of ADLs, is now afforded recognition as a separate area of occupation in the OTPF-2 and “includes activities related to obtaining restorative rest and sleep that supports healthy active engagement in other areas of occupation” (p. 632).2 The component activities constituting rest and sleep include rest, sleep, sleep preparation, and sleep participation (see Chapter 13 for an expanded discussion of this important area of occupation). For Karen, her sleep occupations will be significantly changed as the result of her diagnosis with the need for frequent repositioning during the night for skin precautions as well as setting up equipment to manage her bladder function while she sleeps, to name just a few concerns that OT will need to address.

Education is an area of occupation that includes “activities needed for learning and participating in the environment” (p. 632).2 Specific education activity subcategories include formal education participation, informal personal educational needs or interests exploration (beyond formal education), and informal personal education participation. Table 1 of the OTPF similarly includes more details regarding what specific activities each of these subcategories could entail.

Work includes activities associated with both paid work and volunteer efforts. Specific categories of activities and concerns related to work include employment interests and pursuits, employment seeking and acquisition, job performance, retirement preparation and adjustment, volunteer exploration, and volunteer participation.

Activities associated with play are described as “any spontaneous or organized activity that provides enjoyment, entertainment, amusement, or diversion” (p. 252).16 Considered under this area of occupation are play exploration and play participation.

Leisure is defined as “nonobligatory activity that is intrinsically motivated and engaged in during discretionary time, that is, time not committed to obligatory occupations such as work, self-care or sleep” (p. 250).16 Leisure exploration and leisure participation are the major categories of activity in the leisure area of occupation. Karen shared with Kent her interests in spending leisure time listening to music, traveling, antiquing, swimming, playing bridge, and reading books. When looking at the description of leisure, it occurred to Kent that for Karen, shopping might also be characterized as a leisure activity as well as an IADL. It would probably depend on the circumstances or context in which it was engaged, he thought, another parameter of the OTPF-2 domain he would be learning.

Social participation is an area of occupation that encompasses the “organized patterns of behavior that are characteristic and expected of an individual or a given position within a social system” (p. 633).2 The area of social participation further encompasses engaging in activities that result in successful interaction at the community, family, and peer/friend levels. Just as in previously discussed areas of occupation, Table 1 of the OTPF-2 provides definitions and more detailed information regarding the breadth of activities that constitute OT’s involvement in work, play, leisure, and social participation. Like Kent, readers who are currently learning the OTPF-2 could benefit from studying these expanded lists to broaden their understanding of occupational therapy’s domain. As Kent studied these sections of Table 1, he found it helpful to make note of the content of each as illustrated by activities that were relevant to Karen in these areas of occupation. For example, Kent considered the range of job skills and work routines necessary for Karen to return to her paid position as an administrative assistant as well as similar concerns involved with resumption of her preferred play and leisure occupations including swimming, reading, and board games. Kent was also reminded of the importance of considering the activities that can support or constrain Karen’s continued social participation in her community as a Girl Scout leader, in her family as the oldest daughter, and with her treasured circle of friends.

Performance Skills and Performance Patterns

The reader is reminded throughout the OTPF-2 document that there is no correct or incorrect order in which to study or follow the areas of the domain—“all aspects of the domain transact to support engagement, participation, and health” (p. 628)—there is no hierarchy.2 With this in mind, the next main areas of the domain to consider are performance skills and performance patterns. Both are related to the client’s capabilities in performance in the areas of occupation previously described and can be viewed as the actions and behaviors that are observed by the OT as the client engages in occupations.

The category of performance skills includes five components of concern: motor and praxis skills, sensory-perceptual skills, emotional regulation skills, cognitive skills, and communication and social skills. The client’s successful engagement in occupation or occupational performance is dependent on having or achieving adequate ability in performance skills. In the OTPF-2, performance skills are defined as the abilities clients demonstrate in the actions they perform. Problems in any of the five areas of performance skills are the focus for formulating short-term goals or objectives to reach the long-term goal of addressing participation in occupation.

Motor skills consist of actions or behaviors a client uses to move and physically interact with tasks, objects, contexts, and environments including planning, sequencing, and executing new and novel movements. Definitions of praxis skills provided in Table 4 include “skilled purposeful movements; ability to carry out sequential motor acts as part of an overall plan rather than individual acts; ability to carry out learned motor activity, including following through on a verbal command, visual-spatial construction, ocular and oral-motor skills, imitation of a person or an object, and sequencing actions; and organization of temporal sequences of actions within the spatial context, which form meaningful occupations” (p. 640).2 Examples of motor and praxis skills include coordinating body movements to complete a job task, anticipating or adjusting posture and body position in response to environmental circumstances such as obstacles, and manipulating keys or a lock to open a door.

Kent observed Karen as she played a game of bridge with friends one afternoon in the OT clinic. Observing performance skills, particularly motor skills and praxis skills, Kent noted that Karen looped one elbow around the upright of her wheelchair, leaned her trunk toward the table, reached her other arm toward the cardholder, and successfully grasped a card using tenodesis grasp after three unsuccessful attempts (which Kent perceived as indicating planning, sequencing, and executing new and novel movements).

Sensory-perceptual skills, a second category of performance skills, are the “actions or behaviors a client uses to locate, identify, and respond to sensations and to select, interpret, associate, organize, and remember sensory events based on discriminating experiences through a variety of sensations” (p. 640) that include all of the sensory systems.2 Among the many examples of sensory perceptual skills offered in Table 4 are positioning the body in the exact location for a safe jump and visually determining the correct size of a container for leftover soup.

Emotional regulation skills, the third category of performance skills, involve those “actions and behaviors a client uses to identify, manage and express feelings while engaging in activities or interacting with others” (p. 640).2 Such skills could include persisting in a task despite frustrations and displaying emotions that are appropriate for the situation.

Cognitive skills compose the fourth category of performance skills and are defined as the “actions or behaviors a client uses to plan and manage performance of an activity” (p. 640),2 including selecting necessary supplies and multitasking, which involves doing more than one thing at a time for tasks such as work.

The fifth category of performance skills—communication and social skills—is described as the “actions or behaviors a person uses to communicate and interact with others in an interactive environment” (Fisher, 2006) (p. 641).2 Among the examples offered are taking turns during an interchange with another person and acknowledging another person’s perspective during an interchange (Table 4).2

While Karen played cards, Kent was also able to observe a wide array of examples of Karen’s performance skills. Her sensory perceptual skills were evident as she set up her cardholder so that her cards were within her reach and not visible to her opponents (selecting proper equipment and arranging the space), perused her cards, paused, rearranged them using her tenodesis hand splint (attending to the task, using both knowledge of bridge and selection of proper equipment), and then stated her bid (demonstrating the cognitive skills of discernment and problem solving).

While playing cards, Karen was observed to be furrowing her brow, squinting her eyes shut in a thoughtful cogitating manner, pursing her lips, and showing neither happiness nor despair on her face as she studied her cards in the cardholder (expressing affect consistent with the activity of card playing and thus demonstrating or displaying appropriate emotions as well as cognitive skill in determining her next strategy). As she reached for the cards, the holder moved out of her reach; she asked the friend next to her to push it back, cautioning her in a smiling and light manner, “Don’t dare look!” (demonstrating her ability to multitask—asking for assistance and simultaneously using socially acceptable teasing behavior [communication and social skills] that enlists an opponent’s cooperation in preserving the secrecy of her cards, thus conveying the image indicative of a savvy card player). Her observable performance skills support Karen’s continued inclusion with friends in a favorite leisure occupation.

Each of these particular motor and praxis skills, sensory-perceptual skills, emotional regulation skills, cognitive skills, and communication and social skills categories has detailed lists of representative skills annotated with definitions, descriptions, and examples outlined in Table 4: Performance Skills, in the OTPF-2 document.

Performance patterns are observable patterns of behavior that support or constrain the client’s engagement in occupation. Types or categories of patterns include habits, routines, roles, and rituals.

In the OTPF-2, habits are described for the individual or person as “automatic behavior that is integrated into more complex patterns that enable people to function on a day-to-day basis”—they can be “useful, dominating, or impoverished and either support or interfere with performance in areas of occupation” (p. 642).2 Some examples of habits offered are automatically putting car keys in the same place and spontaneously looking both ways before crossing the street (Table 5A).2 Routines reflect the “patterns of behavior that are observable, regular, repetitive, and that provide structure for daily life. Furthermore, routines can be satisfying, promoting, or damaging. Routines require momentary time commitment and are embedded in cultural and ecological contexts” (p. 643).2 Routines reflect how the individual configures or sequences occupations throughout his or her daily life. Habits typically contribute (positively or negatively) to one’s occupational routines and both are established with repetition over time. The role category of performance patterns is regarded as being composed of “sets of behaviors expected by society, shaped by culture, and may be further conceptualized and defined by the client” (p. 643).2 Rituals are described as “symbolic actions with spiritual, cultural, or social meaning, contributing to the client’s identity and reinforcing values and beliefs. Rituals have a strong affective component and represent a collection of events” (p. 643).2 Definitions and examples of performance patterns for organizations and for populations are outlined in Tables 5B and 5C on page 644 of the OTPF-2 document. Performance patterns for the individual or person and how these can support (or by inference hinder) occupational performance are further illustrated in Part 3 of the threaded case study, “Kent and Karen.”

Context and Environment

The OTPF-2 states that a “client’s engagement in occupation takes place within a social and physical environment situated within context. The physical environment refers to the natural and built nonhuman environment and the objects in them and the social environment encompasses the presence, relationships, and expectations of persons, groups, and organizations with whom the client has contact” (p. 642).2 Contexts are regarded as the interrelated conditions, circumstances, or events that surround and influence the client and in which the client’s daily life occupations take place. Contexts can either support or constrain health and participation in life through engagement in occupation. In the domain of OTPF-2, contexts are composed of six categories or types including cultural, physical, social, personal, temporal, and virtual. Several of the categories of context are regarded as external to the individual such as physical, social, and virtual contexts; some are viewed as internal to the client, such as personal context. Some contexts, such as culture, provide an external expectation of behavior that is often converted into an internal belief. Table 6 in the OTPF-2 document provides detailed definitions and examples of each of these categories. For example, the category of context labeled “physical” encompasses the “nonhuman aspects of contexts. It includes the accessibility to and performance within environments having natural terrain, plants, animals, buildings, furniture, objects, tools or devices” (p. 645).2 Personal context describes “features of the individual that are not part of the health status” (p. 17).21 Personal context includes age, gender, socioeconomic status, and educational status.

Each of these contexts and environments, as they pertain to Karen’s specific circumstances, will significantly affect her future engagement in occupation. Karen’s physical context includes aspects that will support her engagement in occupation including an accessible work site and a reliable and accessible system of public transportation in her neighborhood as well as a well-appointed downtown area of stores, shops, and restaurants within wheelchair distance. Those aspects of her physical environment and context that may interfere with resumption of occupation include Karen’s inaccessible second floor apartment and small inaccessible bathroom. Supportive aspects of Karen’s personal context are her college education in business and the fact that she has unemployment insurance that will supplement her sick leave and continue her health coverage. From a social context perspective, Karen is supported by both her family and friends; additionally, her employer and coworkers are anxious to have her come back to the law firm. The mainstream American cultural context in which Karen was reared—which values and supports the concepts of hard work overcoming adversity (doing rather than being) and the importance of independence (individualism)—seemingly motivates Karen to resume engagement in previous levels of occupation for full participation in all contexts of her life.7

Given the difficulty that resuming Karen’s shopping occupation may present, Kent suggested the possibility of using online shopping for some items. Although interested, Karen indicated that her preference was to shop “in the real world” instead of using the virtual context of computers and airways. Her ultimate decisions will no doubt be influenced by the changes she experiences in her temporal contexts as Karen experiences and adjusts to the increased amounts of time, and scheduling of and around the time of others, required to accomplish basic daily routines that, in turn, support her engagement in preferred occupations.

Activity Demands

Activity demands are focused on the activity and what is required to engage in the activity. Included in this section are several aspects that must be addressed for a client to perform that specific activity, including the following: objects and their properties, space demands, social demands, sequencing and timing, required actions, required body functions, and required body structures. Table 3 of the OTPF-2 document provides a comprehensive list of definitions and examples for a clearer understanding of each of these categories.2 Consider Karen’s interest in shopping in the “real world” instead of making clothing purchases online using a virtual context. The materials or tools needed would be a purse or credit card holder. The space demands would be the accessibility of the store or shopping mall and the dressing room for Karen to try on the clothes before making a purchase. The social demands include paying for the items before leaving the store. The sequence and timing process includes being able to make a selection, go to the register, potentially wait in line, place the clothing on the counter, pay for the item, and then leave the store. The required actions refers to the necessary performance skills to engage in this activity such as the coordination needed to try on clothing, the process skills needed to select one sweater or blouse from a large array of possible choices, and the communication skills needed to ask for assistance or directions if needed.

These performance skills are not viewed in isolation but are seen as Karen engages in the activity of clothes shopping. The required body functions and structures refer to the basic client factors needed to perform the activity of shopping. The act of shopping requires a level of consciousness because inherent in the activity of shopping is having the opportunity to make a choice between available items. Karen’s ability to engage in the activity demand of making a choice of purchases is indicative of her adequate level of consciousness for shopping.

Client Factors

The OTPF-2 describes client factors in a manner similar to the ICF.2,21 There are three categories in this portion of the OTPF-2: values, beliefs, and spirituality; body functions; and body structures. These three client factor categories are regarded as residing within the client and may affect performance in areas of occupation.2

The client factor category of values, beliefs, and spirituality includes values (principles, standards, or qualities considered worthwhile or desirable by the client who holds them), beliefs (described as cognitive content held as true), and spirituality (representing one’s “personal quest for understanding answers to ultimate questions about life, about meaning, and the sacred”) (p. 28).14 For example, Karen’s values, including her strong work ethic and her beliefs and spirituality provide her the reassurance that her spinal cord injury (SCI) was part of a higher power’s plan for her and that she will be given the strength to cope and succeed.

The body structure category refers to the integrity of the actual body part such as the integrity of the eye for vision (see Chapter 24) or the integrity of a limb (see Chapter 43). When the integrity of the body structure is compromised, it can impact function or require alternative approaches to engagement in activities, such as enlarged print for persons with macular degeneration or the use of a prosthesis for a person who sustained a below-elbow amputation. It is unlikely that this category of the domain would have application to Karen, because the integrity of her body structures is not necessarily compromised by her diagnosis. Should she develop a pressure sore, a possible complication of SCI, where the integrity of the body structure (i.e., skin) is compromised, her ability to engage in occupation could become significantly limited requiring alternative approaches such as positioning devices and adaptive equipment to compensate for the need to stay off the pressure sore.

The body function category of client factors refers to the physiologic and psychological functions of the body and includes a variety of systems including, for example, the neuromusculoskeletal and movement-related functions. This category of body functions includes muscle function, which in turn includes muscle strength. A distinction is made between body functions and performance skills. Performance skills, as was described earlier, are observed as the client engages in an occupation or activity. The category of body function refers to the available ability of the client’s body to function. A client may have the available neuromuscular function (client factor of body function; specifically, muscle strength) to hold a comb and bring the comb to the top of the head, and strength to pull the comb through the hair, but when you ask the client to comb his or her hair (an activity), you observe that the client has difficulties manipulating the comb in the hand (motor skill of manipulation) and smoothly using the comb to comb hair (motor skill of flow). These motor skills are included as performance skills in the OTPF-2.

In Karen’s case, absence of functioning muscles in her hands necessitates the use of a functional hand splint or adaptive writing device to enable her to sign the credit card receipt, a required action in her shopping occupation. In order to use a wrist-driven flexor hinge (i.e., tenodesis) hand splint to hold the pen, she must have adequate body function, in this case, fair or better muscle strength in her radial wrist extensors. However, Karen must also have adequate performance skills including the motor skills to exert enough force to adequately write her name, the cognitive or discerning skills to select a type of pen that requires minimum effort to operate, and the communication/social skills to ask sales personnel for a firm writing surface (clipboard) for her lap to compensate for the inaccessibility of the checkout counter.

The mental functions group includes affective, cognitive, and perceptual abilities. This group also includes the experience of self and body image (see Chapters 6, 25, and 26). A client, such as Karen, who has sustained a physically disabling injury, frequently may have an altered self-concept, lowered self-esteem, depression, anxiety, decreased coping skills, and other problems with emotional functions following the injury18 (see Chapter 6). Sensory functions and pain are also included in the body functions category (see Chapters 23 and 28 ). Neuromuscular and movement-related functions refer to the available strength range of motion and movement (see Chapters 19 through 22) but do not refer to the client’s application of these factors to activities or occupations as was seen in the example of Karen signing a credit card receipt as part of engaging in the occupation of shopping. The body functions category also refers to the ability of the cardiovascular, respiratory, digestive, metabolic, and genitourinary systems to function to support client participation. These are further described in both the OTPF-2 and the ICF. The reader is referred to the OTPF-2 Table 2 for a more detailed description of each function included in this category.

The Occupational Therapy Process

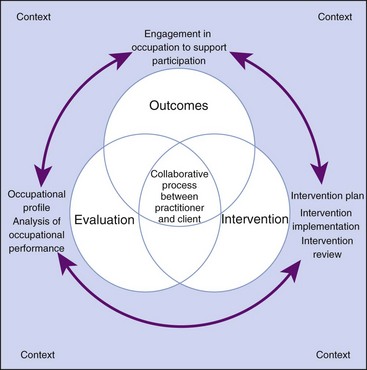

As described at the beginning of this chapter, the OTPF-2 consists of two parts: the domain and the process (Figure 1-2). From a very general perspective, the domain describes the scope of practice or answers the question “What does an occupational therapist do?” The process describes the methods of providing occupational therapy services or answers the question “How does an occupational therapist provide occupational therapy services?”

FIGURE 1-2 Occupational therapy process. (From American Occupational Therapy Association: Occupational therapy practice framework: domain and process, Am J Occup Ther 62(6):625-688, 2008.)

The process is briefly outlined here for continuity but the reader is referred to Chapter 3 for a more in-depth discussion. The primary focus of the OTPF-2 process is evaluation of the client’s occupational abilities and needs to determine and provide services (intervention) that foster and support occupational performance (outcomes). Throughout the process the focus is on occupation; the evaluation begins with determining the client’s occupational profile and occupational history. Preferred intervention methods are occupation based and the overall outcome of the process is the client’s health and participation in life through engagement in occupation.

Interventions also vary depending on the client—whether person, organization, or population. In the practice of occupational therapy with adults with physical disabilities, the term client—at the person or individual level—may vary depending on the treatment setting or environment. In a hospital or rehabilitation center the person might be referred to as a patient, whereas in a community college poststroke program the person receiving occupational therapy may be referred to as a student. The term client or consumer might best describe the person who receives occupational therapy intervention at a center for independent living where the individual is typically living in the community and seeking intervention for a specific self-identified problem or issue.

Types of Occupational Therapy Intervention

Table 1-1 shows the types of occupational therapy intervention typically used in physical disability practice and their relationship to the domain of occupational therapy. Five general categories of intervention are presented in the OTPF-2: (1) therapeutic use of self, (2) therapeutic use of occupations and activities, a category composed of preparatory methods, purposeful activity, and occupation-based activity, (3) consultation process, (4) education process, and (5) advocacy. Because the OTPF-2 has occupation as its primary focus, it is deceptive to think of the types of interventions as being selected or provided in any type of linear or stepwise order on a continuum. Rather, the occupational therapist reflects on the client’s goal of engagement in his or her preferred self-selected occupations and collaborates with the client in selecting the type, or types, of intervention the occupational therapist deems will most successfully facilitate achievement of the occupational goal.

TABLE 1-1

| Type of Intervention | Description |

| 1. Therapeutic use of self | OT uses own self and all that entails (knowledge, personality, and experience), conveying empathy and active listening, and establishing trust |

| 2. Therapeutic use of occupation and activity | Occupations and activities selected for specific clients that meet therapeutic goals |

| a. Occupation based | The client engages in the occupation and activities |

| b. Purposeful activity | The client learns and practices parts or portions of activity |

| c. Preparatory method | Methods that prepare the client for purposeful or occupation-based activity |

| 3. Consultation process | OT uses knowledge and expertise in collaborating with the client to identify problems and develop and try solutions; it is up to the client to implement final recommendation |

| 4. Education process | OT shares knowledge and expertise about engaging in occupation with the client, but the client does not actually engage in the occupation during the intervention |

| 5. Advocacy | Efforts directed toward promoting occupational justice and empowering clients to seek and obtain resources to fully participate in their daily life occupations |

Since the inception of the OTPF and continued in the OTPF-2, the previous concept of intervention levels has been dismissed in favor of viewing them as types of intervention in which no one type is considered of less or more importance than another, but rather each has a potential contribution in facilitating the ultimate goal of supporting health and participation in life through engagement in occupation.

Therapeutic Use of Self: The OTPF-2 describes the therapeutic use of self as “A practitioner’s planned use of his or her personality, insights, perceptions, and judgments as part of the therapeutic process” (p. 653).2 Occupational therapy literature describes an OT who successfully uses therapeutic use of self for intervention as having the qualities or attributes of showing empathy (including sensitivity to the client’s disability, age, gender, religion, socioeconomic status, education, and cultural background), being self-reflective and self-aware, and being able to communicate effectively using active listening and consistently keeping a client-centered perspective that in turn engenders an atmosphere of trust.5,8,17

The very focus of the occupational therapy process provides a favorable context to support the OT’s use of therapeutic use of self as intervention. By using a client-centered approach and beginning the process with an evaluation that seeks information about the client’s occupational history and occupational preferences, the therapist’s initial interactions with the client are characterized to the client as being interested in what the client does (occupational performance), who the client is (contexts and environments, and client factors such as values, beliefs and spirituality), and what occupations give meaning to the client’s life.

Therapeutic Use of Occupations and Activities: This category of occupational therapy intervention in the OTPF was adapted from the section “Treatment Continuum in the Context of Occupational Performance” (Chapter 1, p. 7) in the fifth edition of this book. The category is defined in the OTPF-2 as “Occupations and activities selected for specific clients that meet therapeutic goals. To use occupations/activities therapeutically, context or contexts, activity demands, and client factors all should be considered in relation to the client’s therapeutic goals” (p. 653).2 Specific activities considered to be representative of the category, therapeutic use of occupations and activities, are further separated into three types including occupation-based intervention, purposeful activity, and preparatory methods that will each be discussed here.

Occupation-Based Intervention: In the OTPF-2, the purpose of occupation-based intervention is described as allowing “clients to engage in client-directed occupations that match identified goals” (p. 653).2 Reading this description, Kent considers that occupation-based intervention would include providing intervention to promote engagement in all areas of occupation including ADL, IADL, rest and sleep, education, work, play, leisure, and social participation. Most of the occupational therapy intervention for Karen was occupation-based activity. To reach her targeted goal of resuming her favorite leisure occupation of clothes shopping, Kent and Karen took a trip to a nearby department store where Karen looked for a blouse with three-quarter-inch sleeves and a button-front closure. Karen perused the carousels inspecting the available blouses, asked for help from a salesperson, tried on blouses in the dressing room, made her selection, and paid for her purchase, all parts of a typical shopping excursion in a natural shopping environment. Kent demonstrated and gave suggestions when necessary for how Karen could perform some of the more difficult shopping activities, such as accessing the crowded carousels, negotiating her wheelchair into the dressing room from a narrow hallway, and transporting the hangers with blouses on her lap without having them slide to the ground.

Purposeful Activity: In this type of intervention “the client engages in specifically selected activities that allow the client to develop skills that enhance occupational engagement” (p. 653).2 A few examples offered in the OTPF-2 document include “practices how to select clothing and manipulate clothing fasteners” and “role plays when to greet people and initiates conversation” (p. 653).2 The description of the purpose and the examples offered caused Kent to reframe or slightly reconfigure his view of what purposeful activity entailed. Given the OTPF-2 categorization, he considered that he was providing purposeful activity intervention when he had Karen practicing activities that she would encounter as part of the occupation-based activity of clothes shopping. In the OT clinic, prior to the shopping trip, Karen and Kent collaborated on her being able to perform the purposeful activities of tearing checks out of her checkbook, accessing her credit card from her wallet, using a button hook to button her sweater, and lifting clothes on hangers out of a closet. Some of the shopping activities she encountered while buying her blouse were learned as part of other occupation-based interventions such as wheelchair mobility, writing, and dressing. When using purposeful activity, the OT practitioner is concerned primarily with assessing and remediating deficits in performance skills and performance patterns.

Preparatory Methods: Using intervention that is in nature preparatory, “the practitioner selects directed methods and techniques that prepare the client for occupational performance. It is used in preparation for or concurrently with purposeful and occupation-based activities” (p. 653).2 Preparatory methods used by occupational therapy may include exercise, facilitation and inhibition techniques, positioning, sensory stimulation, selected physical agent modalities, and provision of orthotic devices such as braces and splints. Occupational therapy services for persons with physical disabilities often introduce these methods and devices during the acute stages of illness or injury. When using these methods, the occupational therapist is likely to be most concerned with assessing and remediating problems with client factors such as body structures and body functions. It is important for occupational therapists to plan the progression of this type of intervention so that the selected methods are used as preparation for purposeful or occupation-based activity and are directed toward the overarching goal of supporting health and participation in life through engagement in occupation.

Kent reflected that in preparation for Karen’s occupation-based intervention of clothes shopping he used several interventions that would be considered preparatory methods. For example, he and Karen looked at her options for grasping items and decided on a tenodesis hand splint, using orthotics as an intervention. To use the splint more effectively she had to have stronger wrist extensors and, to push her wheelchair or to reach for and lift hangers with clothes, she needed stronger shoulder muscles; thus, the preparatory intervention of exercise was chosen to facilitate ultimate engagement in purposeful and occupation-based activities.

Consultation Process: Consultation is not a new activity or service provided by OT but is now viewed or labeled as an intervention and situated or integrated into what is considered part of the occupational therapy process. It is defined as “a type of intervention in which practitioners use their knowledge and expertise to collaborate with the client. The collaborative process involves identifying the problem, creating possible solutions, trying solutions, and altering them as necessary for greater effectiveness. When providing consultation, the practitioner is not directly responsible for the outcome of the intervention” (p. 113).10

As Kent studied this description, he considered that throughout his career he has provided occupational therapy services that he would now regard as consultative in nature as described in the OTPF-2. For example, Kent provided consultation with a small chain of grocery stores where he assessed the accessibility and made recommendations to help them reach compliance with the guidelines of the Americans with Disability Act (ADA) (see Chapter 15). Based on his extensive knowledge of the ADA and his expertise in the activity demands for grocery shopping, his recommendations included suggestions for accessible parking and store layout, arrangement of shelves, adaptive equipment to enhance the shopping activity for people with a variety of disabilities, employee training to increase awareness of the shopping needs of people with disabilities, and many other ideas for streamlining the shopping experience for this population. After Kent completed the report of his recommendations and shared them with his client (the owners of the grocery store chain/organization) he had completed his OT intervention and it was up to the client to implement his suggestions. Many of Kent’s clients with SCI could potentially benefit from the implemented suggestions he had made, but this is not part of the consultation process intervention. With Karen’s family he provided consultation intervention (on an individual or person level) when he gave them advice regarding what specifications to look for in an accessible apartment for Karen.

Education Process: The OTPF-2 describes education process as a “type of intervention process that involves the imparting of knowledge and information about occupation and activity and that does not result in the actual performance of the occupation/activity”(p. 654).2 Kent also considered this definition, thinking of instances when he provided this type of intervention. Most recently, with Karen, he responded to her concerns about returning to her job as an administrative assistant. She was having misgivings about the amount of physical work and energy involved; the modest amount of salary she received, which barely covered her preinjury expenses; and the additional expenses she would have for personal and household assistance. Using his years of knowledge and experience, Kent provided intervention in the form of educating Karen about her options by informing her about the services offered by vocational rehabilitation and educating her about the possibilities and opportunities for further education to support her work goal of becoming an attorney, a job position, he pointed out, that held potential for higher pay and one that could be less physically demanding than her administrative assistant position. He informed her about the similar circumstances of some of his former clients, describing the various scenarios and outcomes of each (being mindful to preserve the former clients’ anonymity and privacy), as well as using his wealth of experience to discuss the many resources available to facilitate such options. Karen was already preparing to resume her job (an occupational goal she prioritized) and was actively participating in OT by engaging in occupation-based activity that involved her actual work occupations and supporting activities. The education process intervention described, however, provided her knowledge of options but did not involve any actual performance of an activity during the intervention. Kent could use the same education intervention process with Karen’s vocational counselor as well as with the law firm for which Karen is employed.

The intervention type identified as advocacy is provided when efforts are directed toward promoting occupational justice (access to occupation) and empowering clients to seek and obtain resources to fully participate in their daily life occupations (p. 654).2 Kent worked with Karen and Karen’s work supervisor to advocate to the law firm partners for reasonable accommodations to support Karen’s continued employment. After a year of Karen’s successful job performance, Kent was invited to the state bar association conference to advocate for similar collaborations on behalf of other employees with disabilities.

Having studied the OTPF domain, process, and types of interventions and reinforcing his learning through application of his new knowledge to his own circumstances and those of his client Karen, Kent still felt the need for some additional suggestions or strategies for learning the OTPF more thoroughly. The next section explores these strategies.

Strategies for Learning the OTPF-2

The most effective first step in learning the OTPF-2 may be to obtain and thoroughly read the original document, making notations as points arise, drawing diagrams for increased understanding, writing questions or observations in the margins, and consulting tables, figures, and the glossary when directed, to reinforce or explicate new learning. The OTPF-2 is a comprehensive conceptualization of the profession that requires a substantial investment of time and commitment to study and apply to practice before one feels comfortable in its use. Box 1-1 provides an abbreviated list of some of the core terminology and concepts of the Framework to serve as a quick reference or to jog the reader’s memory when first learning and using the OTPF.

More experienced occupational therapists who are accustomed to using the first iteration of the OTPF will find it helpful to consult the comparison of terms section, Table 11: Summary of Significant Framework Revisions, on pages 665-667 at the end of the AJOT article on the OTPF-2,2 where terminology used in the Framework II is compared to that of the original OTPF. For those occupational therapists who are still using the UT-III, another, lengthier article titled “From UT-III to the Framework: Making the Language Work”9 similarly compares the three documents. Both articles provide helpful tables showing the language of the UT-III, the OTPF counterpart, and that of the ICF. For example, one section of this table shows Performance Area (UT-III), Performance in Areas of Occupation (OTPF), and Activities and Participation (ICF), giving indications of the specific language used by each to name similar constructs. The occupational therapist can easily find the previous or older designation in one column, consider the new replacement terminology of the OTPF in another column, and locate the corresponding term from the ICF in yet another column.

Several pioneering authors wrote helpful articles demonstrating application of the OTPF for the various AOTA special interest sections (SIS). Siebert, writing for the Home and Community Health SIS, encouraged that it is “not as important to learn the OTPF as to use it as a tool to communicate practice, to support practice patterns that facilitate engagement in occupation, and to reflect on and refine our practice” (p. 4).20 She also pointed out the dominant role that context plays in home and community practice by providing continuity to the client, noting how firmly the OTPF supports this concept. She expressed her belief that the focus of the Framework on occupation and the beginning of the process with the client’s occupational profile ensures that the results of OT intervention will matter to the client.20

Coppola, writing for the Gerontology SIS, described how the Framework can be applied to geriatric practice and explained that the evaluation is one of OT’s most powerful ways of informing others (including clients and colleagues) what OT is and what OT does. She provided a working draft of an Occupational Therapy Evaluation Summary Form that was developed to incorporate the OTPF and highlight occupation in a visual way into her practice in a geriatric clinic. The draft is unconstrained by the more traditional documentation forms that seem to bury occupation under diagnostic and clinical terminology.6

Similarly, Boss offered readers of the Technology SIS his reflection on how the Framework can be operationalized in an assistive technology setting. Addressing each of the categories of the domain, he offered examples of how assistive technology supports engagement in occupation (allowing completion of an activity or occupation) and how the use of assistive technology (personal device care and device use) can be an occupation in, and of, itself. He concluded his article by pointing out that “assistive technologies are all about supporting the client’s participation in the contexts of their choice and are therefore part of the core of occupational therapy” (p. 2).4

Another strategy intended to facilitate the reader’s education in the OTPF is the format of the chapters in this book as described next.

The OTPF-2: Its Use in This Book

In keeping with the OTPF-2’s central focus on the client and the importance of contexts and participation in occupation, each chapter begins with a case study and then integrates the information presented with consideration of that client and circumstances, similar to the use of Kent and Karen’s experiences as described and threaded throughout this chapter. As the particular content information is presented, the reader is frequently asked to reflect back to the case scenario and consider how the information applies to the specifics of the client portrayed. The probative questions asked at the conclusion of the initial portion (or Part 1) of the chapter’s case study are also answered throughout the text or addressed at the end of the chapter.

Summary

“The Occupational Therapy Practice Framework,” the original (2002) and the revised “Occupational Therapy Practice Framework,” Second Edition, were developed by the profession to reassert its focus on occupation and clearly articulate and enhance the understanding of the domain of occupational therapy (what OT practitioners do) and the occupational therapy process (how they do it) to both internal audiences (members of the profession) and external audiences (clients, healthcare professionals, and interested others). The overarching goal of Framework II is to support health and participation in life through engagement in occupation, which emphasizes the primacy of occupation, regarding it as both the theme of the domain and the outcome of the process.

The domain includes six categories that constitute the scope of occupational therapy, including performance in areas of occupation, performance skills and performance patterns, contexts, activity demands, and client factors. The OT process involves three interactive phases of occupational therapy services including evaluation, intervention, and outcomes, which occur in a collaborative and nonlinear manner. The types of occupational therapy intervention included in the Framework II and typically employed in physical disabilities practice settings include therapeutic use of self, therapeutic use of occupations and activities (including occupation-based activity, purposeful activity, and preparatory methods), consultation process, education process, and advocacy. In addition to studying the chapter, readers are encouraged to explore the AOTA’s OTPF-2 document in its entirety and reinforce their learning by applying Framework II to their own life experiences and those of the clients they encounter in the case studies presented throughout the chapters of the book as well as those they experience in the clinic.

1. Briefly describe the history of the evolution of the “Occupational Therapy Practice Framework,” Second Edition.

2. Describe the need for the OTPF-2 in the practice of occupational therapy for persons with physical disabilities.

3. Describe the fit between the OTPF-2 and the ICF and how they inform and enhance the occupational therapist’s understanding of physical disability.

4. List and describe the components that make up the occupational therapy domain, and give examples of each.

5. List and describe the components that make up the occupational therapy process, and give examples of each.

6. Briefly describe the occupational therapy intervention levels, and give an example of each as it might be used in a physical disability practice setting.

References

1. American Occupational Therapy Association. Occupational therapy practice framework: domain and process. Am J Occup Ther. 2002;56(6):609.

2. American Occupational Therapy Association. Occupational therapy practice framework: domain and process, ed 2. Am J Occup Ther. 2008;62(6):625–688.

3. American Occupational Therapy Association. Uniform terminology for occupational therapy, ed 3. Am J Occup Ther. 1994;48:1047.

4. Boss, J. The occupational therapy practice framework and assistive technology: an introduction. Technol Special Interest Section Quarterly. 13(2), 2003.

5. Cara, E. Methods and interpersonal strategies. In: Cara E, MacRae A, eds. Psychosocial occupational therapy: a clinical practice. Clifton Park, NY: Thomson/Delmar Learning; 2005:359.

6. Coppola, S. An introduction to practice with older adults using the occupational therapy practice framework: domain and process. Gerontol Special Interest Section Quarterly. 26(1), 2003.

7. Crabtree, JL, et al. Cultural proficiency in rehabilitation: an introduction. In: Royeen M, Crabtree JL, eds. Culture in rehabilitation: from competency to proficiency. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall; 2006:1.

8. Crawford, K, et al, Therapeutic use of self in occupational therapy. unpublished master’s project, San Jose, CA, San Jose State University, 2004.

9. Delany, JV, Squires, E. From UT-III to the Framework: making the language work. OT Practice. 20, May 10, 2004.

10. Dunn, W. Best practice in occupational therapy in community service with children and families. Thorofare, NJ: Slack; 2000.

11. Gutman, SA, Mortera, MH, Hinojosa, J, Kramer, P. Revision of the occupational therapy practice framework. Am J Occup Ther. 2007;61:119–126.

12. Hunt, L, Salls, J, Dolhi, C, et al. Putting the occupational therapy practice framework into practice: enlightening one therapist at a time. OT Practice. August 27, 2007.

13. Law, M, et al. Core concepts of occupational therapy. In: Townsend E, ed. Enabling occupation: an occupational therapy perspective. Ottawa, ONT: CAOT; 1997:29.

14. Moyers, PA, Dale, LM. The guide to occupational therapy practice, ed 2. Bethesda, MD: AOTA Press; 2007.

15. Nelson, DL. Critiquing the logic of the domain section of the occupational therapy practice framework: domain and process. Am J Occup Ther. 2006;60(5):511–523.

16. Parham LD, Fazio LS, eds. Play in occupational therapy for children. St Louis: Mosby, 1997.

17. Peloquin, S. The therapeutic relationship: manifestations and challenges in occupational therapy. In: Crepeau EB, Cohn ES, Schell BAB, eds. Willard and Spackman’s occupational therapy. ed 10. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003:157.

18. Pendleton, HMH, Schultz-Krohn, W. Psychosocial issues in physical disability. In: Cara E, MacRae A, eds. Psychosocial occupational therapy: a clinical practice. Clifton Park, NY: Thomson/Delmar Learning; 2005:359.

19. Roley, SA, Delany, J. Improving the occupational therapy practice framework: domain and process: The updated version of the Framework reflects changes in the profession. OT Practice. February 2, 2009.

20. Siebert, C. Communicating home and community expertise: the occupational therapy practice framework. Home Community Special Interest Section Quarterly. 10(2), 2003.

21. World Health Organization. International classification of functioning, disability, and health (ICF). Geneva: WHO; 2001.

22. Youngstrom, MJ. The occupational therapy practice framework: the evolution of our professional language. Am J Occup Ther. 2002;56(6):607.

Christiansen, CH, Baum, CM. editors: Occupational therapy: enabling function and well-being. Thorofare, NJ: Slack; 1997.

Law, M. Evidence-based rehabilitation: a guide to practice. Thorofare, NJ: Slack; 2002.

Law, M, et al. Occupation-based practice: fostering performance and participation. Thorofare, NJ: Slack; 2002.

Youngstrom MJ: Introduction to the occupational therapy practice framework: domain and process, AOTA Continuing Education Article, OT Practice, Bethesda, MD, September, CE-1-7, 2002.