Postoperative surgical phase

After surgery a client’s care can become complex as a result of physiological changes that may occur. Clients who have undergone GA are more likely to face complications than those who have had only local anaesthesia. The client who requires GA has usually undergone extensive surgery as well. In contrast, a same-day surgery client who has had local anaesthesia with no sedation and has stable vital signs may be immediately discharged. A client who has undergone regional anaesthesia or GA is usually transferred to a high-dependency area in the operating suite called the post-anaesthesia recovery unit (PARU; also referred to as the post-anaesthetic care unit (PACU) in a number of settings) to be stabilised before discharge, whereas a client who has had local anaesthesia may go directly to the nursing unit or back to the same-day surgery centre.

A client’s postoperative course involves two phases: the immediate recovery period (in PARU/PACU) and postoperative rehabilitation. For a same-day surgery client, recovery normally lasts only 1–2 hours, and rehabilitation takes place at home. For a hospitalised client, recovery may last a few hours, and rehabilitation takes 1 or more days depending on the extent of surgery and the client’s response.

Immediate postoperative recovery

Immediately following surgery the client is transferred to the PARU. The client may ask the PARU nurse what the surgeon specifically did during the operation. It is the surgeon’s responsibility to describe the client’s status, the results of surgery and any complications that may have been encountered.

Discharge from the PARU

The recovery nurse evaluates client readiness for discharge from the PARU on the basis of several factors, including preoperative status, surgical procedure, anaesthetic, level of conscious state, level of pain, nausea and vomiting, and vital-sign stability (Phillips and others, 2011). Other outcomes for discharge include absence of complications, controlled wound drainage and adequate urine output. Clients with more-extensive surgery requiring anaesthesia of longer duration usually recover more slowly.

When the client has been assessed as ready to be discharged from the PARU, the nurse calls the nursing unit. The nurse from the unit attends the post-anaesthetic unit and receives a hand-over from the PARU nurse. The comprehensive hand-over includes specifics regarding the surgery performed and type of anaesthesia, and a report of vital signs, blood loss, level of consciousness, general physical condition, presence of IV lines, drainage tubes or catheters and any specific documented postoperative orders. The PARU nurse’s report helps the nurse in the acute-client-care area to anticipate special client needs and obtain necessary equipment. The client is usually returned to the surgical unit on a trolley. Nurses in the surgical unit assist to safely transfer the client to a bed.

Recovery in same-day surgery

The thoroughness and extent of postoperative assessment depends on the same-day surgery client’s condition, type of surgery and anaesthesia. In many cases, the assessment is identical to that conducted for hospitalised clients. However, if the client has undergone minor surgery (e.g. cosmetic removal of a mole), the postoperative recovery phase requires minimal assessment.

The time that a client spends in recovery depends on several factors. Outpatient anaesthesia is gauged to provide a quick recovery time, few after-effects and a speedy return to daily routines. The average time spent (without complications) is 1 hour. Clients are encouraged to gradually sit up on the trolley or bed and begin to take ice chips or sips of water while regaining full alertness. Some clients who have undergone minor surgery may be transferred directly to a room equipped with medical recliner chairs, side tables and foot rests. Kitchen facilities for preparing light snacks and beverages are usually located in the area, along with bathrooms. Considerations for discharge for ambulatory clients include condition of the dressing, intensity and location of pain, ability to stand and walk, tolerance of oral fluids and/or food and ability to urinate spontaneously (Herrera and others, 2007). Nurses review postoperative education and instructions with the client and their support person (Box 44-5).

BOX 44-5 CLIENT TEACHING OF POSTOPERATIVE INSTRUCTIONS FOR AMBULATORY SURGICAL CLIENT

TEACHING STRATEGIES

• Give instruction sheet with centre’s number and follow-up appointment date and time. Allow client and family to ask questions.

• Explain to family member the signs and symptoms of infection or other relevant complications to watch for.

• Explain name, dose, schedule and purpose of medications. Provide drug information leaflets.

• Explain activity restrictions, diet progression and any special wound care related to specific surgery. Provide instruction sheet with clear, focused explanations.

EVALUATION

• To confirm the client’s understanding after teaching, have the client ‘teach back’ discharge information to you (e.g. ‘What are you going to do when you get home?’)

• Client is able to explain when to call healthcare provider with problems.

• Client is able to state date for follow-up appointment.

• Client and family member describe signs and symptoms of infection or other relevant complications.

• Client able to state name of drug/s, dose and when to take.

• Client demonstrates appropriate activity/movement and wound care.

Postoperative rehabilitation

Same-day surgery clients are discharged to home when they meet certain criteria; for example, they are alert and oriented, have minimal nausea/vomiting, minimal postoperative pain and no excess bleeding or drainage, are able to void (if applicable) and walk, they have received written postoperative instructions and prescriptions, they understand these instructions and they are being discharged to a responsible adult.

THE NURSING PROCESS IN POSTOPERATIVE CARE

Nursing care in the PARU focuses on careful monitoring and maintenance of the patient’s airway, breathing, circulation and neurological status, as well as the management of acute pain and other postoperative complications. Other important factors to assess include temperature, skin and incision/wound status, fluid and electrolyte balance and genitourinary and GI function. These factors are not, however, unique to the PARU setting. The nurse in the acute care area continues assessment of these critical factors on a less-intensive and less-frequent basis until the client’s discharge from the acute care facility.

ASSESSMENT

After the client is transferred from the PARU to the acute care area, an initial assessment is conducted by the nurse. This focused body systems assessment is based on the nature of the surgery, type of anaesthetic given and the postoperative plan of care. An important component of postoperative monitoring to detect complications is the assessment of vital signs (see Skill 28-6) (Fernandez, 2005). Vital-sign assessment is often conducted every 30 minutes for 2–4 hours initially, and if the client’s condition is stable the frequency is reduced as per the institution policy and the client’s condition. The postoperative orders usually specify when vital-sign changes are to be reported. However, you must carefully monitor your client and use your clinical judgment skills. A client’s condition can change rapidly, especially during the postoperative period.

The nurse documents the initial assessment, including vital signs, level of consciousness, condition of dressings and drains, pain level, IV fluid status and urinary output measurements. Client data can be entered on flow sheets, a computerised client record or progress notes; this is specific to the institution. The preoperative findings are used as a baseline for comparing postoperative changes.

After the first assessment is completed in the acute care area and immediate needs are attended to, the family may visit. The nurse can explain the purpose of postoperative procedures or equipment and how the client is. The family should know that the client may be sleepy from the effects of a general anaesthesia and pain medication. The family should also be informed that frequent assessments are to be expected and that loss of sensation and movement in the extremities remains for several hours if the client had spinal or epidural anaesthesia.

Respiration

Certain anaesthetic agents and opioid analgesics may cause respiratory depression. The first and most important clinical indicator of opioid-induced respiratory depression is increasing level of sedation (Chapter 41). The nurse is also alert for shallow, slow breathing and a weak cough. The nurse regularly assesses sedation score, respiratory rate, rhythm, depth, symmetry of chest-wall movement, breath sounds, and colour of mucous membranes. If breathing is unusually shallow, placement of the hand over the client’s face or mouth allows the nurse to feel exhaled air. Pulse oximetry is also used to monitor the client’s oxygen saturation (Fernandez, 2005).

If the client has an altered conscious state and is extremely drowsy, and there is difficulty rousing the client, consideration needs to be given regarding the ability of the client to maintain a patent airway, especially if there is any vomiting or secretions. The client may not be able to clear their own secretions and suction may be required. In the postanaesthetic client, the tongue causes the majority of airway obstructions.

It is important after the immediate postoperative period that the nurse providing ongoing care in the acute environment continues respiratory assessments, especially auscultation of lung sounds. Older clients and those with a history of respiratory disease or smoking are more prone to developing complications such as atelectasis or pneumonia. The client should also be assessed for signs of shortness of breath or difficulty breathing on exertion (e.g. when showering). A pulmonary infection caused by aspiration in the operating room or PARU setting may not be evident until several days later. Clients should also be instructed to report any symptoms to their medical practitioner after discharge, since the length of stay in acute care may be quite short.

The clinical example opposite gives a typical scenario for a patient with postoperative respiratory complications.

• CRITICAL THINKING

1. From the clinical example opposite, explain the most likely cause for Mr Summers’ postoperative respiratory complication. What postoperative nursing interventions might have prevented this complication?

2. Using the primary survey as a framework to prioritise, identify the priority interventions for Mr Summers’ postoperative respiratory compromise. Ensure that you can justify your priority interventions with scientific rationales and evidence-based literature.

3. For each intervention you have selected, outline two specific evaluation criteria that would indicate to you that this intervention is having the desired effect.

Circulation

The client is at risk of cardiovascular complications resulting from blood loss from the surgical site, side effects of anaesthesia, electrolyte imbalances and depression of normal circulatory regulating mechanisms. Careful assessment of heart rate and rhythm, along with blood pressure, reveals the client’s cardiovascular status. An ECG may be performed if, for example, the client has a cardiac history.

The nurse assesses peripheral perfusion by palpating pulses and noting colour, warmth, movement, sensation, and capillary refill time for the nail beds and skin. If the client has had vascular surgery or has casts or constricting devices that may impair circulation, the nurse assesses peripheral pulses distal to the site of surgery. For example, after surgery to the femoral artery, the nurse assesses posterior tibial and dorsalis pedis pulses. The nurse also compares pulses in the affected extremity with those in the non-affected extremity. Redness, pain and swelling, especially in a lower extremity, could be an indication of a DVT.

A common early circulatory problem is haemorrhage. Blood loss may occur externally through a drain or incision or internally within the surgical wound. Either type of haemorrhage may result in an elevated heart and respiratory rate; thready pulse; cool, clammy, pale skin; restlessness; and with progressive shock, decreased blood pressure. If haemorrhage is external, the nurse observes increased bloody drainage on dressings or through drains. Sometimes, the blood can ooze down the client’s side and collect in a pool under the client. It is important to always check under the client for drainage even if the dressing is not saturated. When haemorrhage is internal, the operation site becomes swollen and tight. For example, if a client bleeds within the abdomen, the abdomen becomes tight and distended. The first signs of suspected haemorrhaging should be reported to the surgeon immediately. The nurse maintains IV fluids and monitors the client’s vital signs every 15 minutes or more frequently until the client’s condition stabilises. Oxygen may be initiated and the client’s legs and head slightly elevated to promote venous return and increase the volume of blood available for supplying oxygen and nutrients to vital organ systems. Further medications and IV volume replacement such as blood products may be ordered.

Reproduced with permission of Queensland University of Technology.

Harry Summers, a 73-year-old man, was admitted to the orthopaedic ward 2 days ago following a fall down some stairs in his home. He lives alone, but his daughter lives with her family in the next suburb. On admission to the ward Mr Summers presented as follows:

| Glasgow Coma Scale | 15 |

| Heart rate | 90 beats/minute and regular |

| Blood pressure | 145/92 mmHg |

| Respiratory rate | 22 breaths/minute |

| SpO2 | 99% on 3 L/minute oxygen via nasal prongs |

| Temperature | 36.9°C |

| Neurovascular assessment: | ||

|---|---|---|

| RIGHT LEG | LEFT LEG | |

| Colour | Pale | Pink |

| Temperature | Cool | Warm |

| Capillary refill | > 2 secs | < 2 secs |

| Distal pulses | Present | Present |

| Oedema | Yes, to hip | Nil |

Mr Summers reported pain in his right leg and hip. There was some bruising and skin discolouration to his right upper thigh. His right leg was externally rotated and slightly shorter than the left.

He was diagnosed with a fractured right neck of femur and went to theatre for open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) of the right femur. He recovered satisfactorily postoperatively; however, he required supplemental oxygen to maintain oxygen saturations above 95%. Pain was managed with a morphine patient-controlled analgesia (PCA), 1 mg bolus dose with 5 minute lockout.

Mr Summers is now 2 days postsurgery and you are the registered nurse caring for him today. At the beginning of your shift you collect the following assessment data:

| Heart rate | 108 beats/minute and regular |

| Blood pressure | 165/98 mmHg |

| Respiratory rate | 28 breaths/minute, deep and laboured |

| Chest | |

| SpO2 | 89% on Hudson mask at 6 L/minute oxygen |

| Temperature | 38.5°C |

When assessing his pain, you note that he has utilised the PCA only once in the last 3 hours. He reports his pain is currently at 5 at rest on a 0–10 numerical rating scale. He is reluctant to move and, on questioning, states that he has not used the PCA much as he does not want to become addicted to the drugs.

Mr Summers is reviewed by the resident medical officer. A chest X-ray shows right-sided basal consolidation and collapse and he is diagnosed with right-sided pneumonia.

If the client is on prolonged bed rest or has reduced mobility, anticoagulants may be ordered in addition to the use of pneumatic compression stockings. This is to prevent the formation of a DVT. The risk of DVT decreases when the client begins to mobilise.

The clinical example on the next page describes a scenario in which a patient experiences cardiovascular complications following surgery.

Temperature control

The operating room and PARU environments are extremely cool. The client’s anaesthetically depressed level of body function results in a lowering of metabolism and a fall in body temperature. When clients begin to wake, they often complain of feeling cold. The length of time spent in the operating room and laminar flow rooms contributes to heat loss (Wagner and others, 2006). Surgeries that require an open body cavity also contribute to heat loss. Older adults and paediatric clients are at higher risk of developing problems associated with hypothermia.

Reproduced with permission of Queensland University of Technology.

Ken Petrovsky, a 57-year-old obese man, had a 3-month history of progressive anginal chest pain. His electrocardiogram (ECG) was unremarkable. His general practitioner referred him for an exercise stress test which was terminated after 3 minutes because he developed anterior chest pain and 2 mm ST-segment depression in leads V1 through V4. Sublingual glyceryl trinitrate times two was needed to relieve the chest pain.

Coronary angiography revealed severe triple-vessel coronary artery disease. Mr Petrovsky was scheduled for urgent coronary artery revascularisation with bypass grafts to the three involved coronary arteries. Following surgery, Mr Petrovsky had an uneventful postoperative recovery. By the second postoperative day, he had been extubated and pacing wires had been removed. An underwater seal chest drain (UWSD) and urinary catheter remained in situ. He was transferred to the cardiac ward with intravenous normal saline 0.9% running at 80 mL/hour, and a fentanyl patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) device in situ.

You are the graduate registered nurse responsible for Mr Petrovsky’s care. His initial assessment showed unremarkable vital signs, the intravenous normal saline running at 80 mL/hour and the fentanyl PCA. The UWSD showed minimal haemoserous drainage, no air loss and slight respiratory swing. His urine output for the last hour was 100 mL. He was pain-free at rest, and on examination of the PCA he had only utilised it twice in the preceding 2 hours. His wound was dry and intact.

You return to Mr Petrovsky’s room later in the shift to find him distressed. He states that he has pain rated 2 out of 10 at rest and you note he has used the PCA twice in the last hour. On inspection, the UWSD drain has 600 mL of bright red loss draining, respiratory swing is slight and there is no air loss. You take his vital signs and note the following:

| Temperature | 37.5°C |

| Blood pressure | 90/60 mmHg |

| Heart rate | 120 beats/minute and regular |

| Respiratory rate | 24 breaths/minute |

| Chest | Air entry equal, diminished in the bases, no adventitious sounds |

| SpO2 | 92% on room air |

| Urine output | 15 mL in the last hour |

| Skin | Cold, clammy with capillary refill > 4 seconds |

Mr Petrovsky is diagnosed with hypovolaemic shock, and it is decided that he needs to return to the operating theatre so you initiate this process.

• CRITICAL THINKING

1. From the clinical example above, identify the key pieces of assessment data that support a diagnosis of hypovolaemic shock.

2. Using the primary survey as a framework to prioritise, identify the priority interventions to implement for Mr Petrovsky while surgery is being organised.

3. For each intervention you have selected, outline two specific evaluation criteria that would indicate to you that this intervention is having the desired effect.

The nurse measures the client’s body temperature and provides warmed blankets if required. Shivering may not be a sign of hypothermia, but rather a side effect of certain anaesthetic agents. Deep-breathing and coughing help expel retained anaesthetic gases. If the client’s temperature is 35.6°C or below, a warming device may be used. Increasing body warmth causes the client’s metabolism to rise and circulatory and respiratory functions to improve.

In rare instances malignant hyperthermia can develop, a life-threatening complication of some anaesthetic drugs. Malignant hyperthermia causes tachypnoea, tachycardia, unstable blood pressure, cyanosis, skin mottling and muscular rigidity. Despite the name, an elevated temperature is a late sign. Although it is often seen during the induction phase of anaesthesia, symptoms may recur 24–72 hours postoperatively. Without proper treatment, it can be fatal.

Temperature is monitored relatively closely when a client who has had surgery is in the acute care area. An elevated temperature may be the first indication of an infection. If the client’s temperature is elevated, the nurse assesses the client for a potential source of infection, including the IV site (if present), the surgical incision/wound, the respiratory system (potential for chest infection) and the urinary system (potential for urinary tract infection). The medical officer must be notified, as further assessments may be ordered, including blood collection (e.g. blood cultures), sputum specimen and urinary specimen.

Fluid and electrolyte balance

Because of the surgical client’s risk of fluid and electrolyte abnormalities, the nurse assesses the hydration status and monitors cardiac and neurological function for signs of electrolyte alterations (see Chapter 39). Fluids are especially important as the client recovers from regional anaesthesia. Laboratory values will be monitored and compared with the client’s baseline values.

An important responsibility is assessment of the client’s IV site for signs and symptoms of infiltration and phlebitis. The client’s only source of fluid intake immediately after surgery may be through an IV.

To ensure adequate fluid intake, the nurse administers the infusion as ordered. If assessments indicate a fluid volume deficit or a fluid volume excess, the nurse should notify the medical officer of the data and the infusion and/or rate may be changed. As the client begins to commence oral fluids, the ordered IV rate will usually be decreased. When the client no longer requires a continuous IV infusion, the IV line may be capped (‘bunged off’) and normal saline flushes ordered to ensure IV cannula patency for medication administration (e.g. antibiotics). The client may also be ordered to receive blood products after surgery, depending on blood loss during surgery.

Accurate recording of fluid intake and output assists with assessment of renal and circulatory function. The nurse may need to document input and output on a fluid balance chart. This is dependent on the surgery, client’s past history, client condition and whether the client has an IV, drains and other interventions such as an IDC or NGT. The nurse measures all sources of output, including urine, drains, gastric drainage via emesis or NGT and drainage from wounds, and notes any insensible loss from diaphoresis.

Neurological function

WORKING WITH DIVERSITY FOCUS ON OLDER ADULTS

Acute delirium is common in older people following surgery, occurring in up to 30% of elderly clients. Delirium can be caused by many physiological problems, including metabolic imbalances, infection, dehydration and malnutrition. Nurses need to be alert to rapid changes in a client’s mental state which may include disorganised thinking, incoherent speech and restless, agitated behaviour. A focused nursing assessment is necessary to determine the cause of delirium, which is often reversible.

Poole J, Mott S 2003 Agitated older patients: nurses’ perceptions and reality. Int J Nurs Pract 9(5):306.

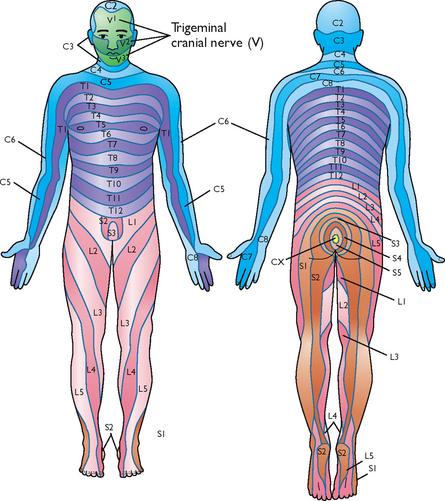

A client will have been orientated to the environment before being discharged from the PARU, and the nurse from the acute area should ensure that the client is rousable prior to agreeing to accept the client from the PARU. If a client has had surgery involving a part of the neurological system, the nurse conducts a thorough neurological assessment. For example, if the client has had low back surgery, the nurse assesses leg movement, sensation and strength. Clients with regional anaesthesia begin to experience a return in motor function before tactile sensation returns. Dermatome (a segmental skin area innervated by segments of spinal cord) assessment of the spinal nerves is performed (Figure 44-8). Typically, the nurse assesses the level of sensory block by testing the dermatome level at which the client reports a change in temperature sensation when ice or alcohol is applied to the skin.

FIGURE 44-8 Segmental dermatome distribution of spinal nerves. C, Cervical segments; T, thoracic segments; L, lumbar segments; S, sacral segments.

Modified from Thibodeau GA, Patton KT 2002 Anthony’s textbook of anatomy and physiology, ed 17. St Louis, Mosby.

Orientation to the environment is important in maintaining the client’s alertness. The nurse may need to re-orientate the client to the ward, explain that the surgery is completed and describe the nursing measures being carried out. The client who was properly prepared before surgery is likely to be less anxious when nurses begin their care.

Unless the client has undergone neurological surgery, the focus of the nursing assessment will be on a basic neurological examination. Of primary importance is the client’s level of consciousness. An altered level of alertness may be an indicator that client condition is deteriorating. Although the client may still be drowsy from anaesthesia, the nurse should be able to assess the client’s ability to follow commands and answer questions assessing their orientation. Extremity strength assessment is important if spinal or epidural anaesthesia has been administered.

Skin integrity

After surgery, most surgical wounds are covered with a dressing that protects the wound site and absorbs drainage. The nurse observes the dressing for drainage: colour, amount (marking around the ooze with a permanent pen, including date and time), consistency and odour. Some smaller wounds are covered with a transparent dressing only, facilitating ongoing assessment of the wound. The dressing is left intact, thereby reducing the risk for infection from dressing changes.

Many surgeons prefer to assess the incision and surrounding skin the first time the dressing is removed, or ‘taken down’. The nurse in the acute care area assesses the wound site and documents the assessment and any related interventions (see Chapter 30). The first assessment is important as it forms the baseline for continued wound evaluation during the client’s hospital stay.

It is also important to consider the client’s mobility level. If the client is unable or unwilling to turn, the client is at increased risk for pressure injury. The nurse should follow institutional policy regarding assessment of client risk for pressure injury (e.g. use of the Braden Scale). Appropriate preventive measures can then be implemented to manage the risk (see Chapter 30).

The nurse also assesses the condition of the client’s skin, noting rashes, abrasions, bruising or burns. A rash may indicate a drug sensitivity or allergy. Abrasions or bruising may result from inappropriate positioning during surgery. A burn may indicate that an electrical cautery grounding pad was incorrectly placed on the client’s skin during surgery. Burns or serious injury to the skin should be documented following institutional policy (e.g. completion of an incident report and entry into the risk-management system).

Genitourinary function

Depending on the surgery, a client may not regain voluntary control over urinary function for 6–8 hours after anaesthesia. An epidural or spinal anaesthetic may prevent the client from feeling bladder fullness or distension. The nurse palpates and percusses the lower abdomen just above the symphysis pubis for bladder distension. Clients may need an intervention to void if their bladder becomes distended. If an IDC is inserted, the expected minimum urine output is 0.5–1 mL per kg per hour (0.5–1 mL/kg/h) in adults. The nurse assesses not only the amount of urine, but also its colour and odour. A urinalysis may be conducted to ascertain specific gravity if fluid volume deficit is suspected.

Surgery involving portions of the urinary tract normally cause bloody urine for at least 12–24 hours, depending on the type of surgery. The acute care nurse will provide ongoing assessment of genitourinary function. If the client has an IDC, the goal should be to have it removed as soon as possible. Clients with an IDC are at high risk of developing a healthcare-associated bladder or urinary tract infection. This will contribute to client discomfort, increased costs and possible increase in length of hospitalisation.

Gastrointestinal function

Anaesthetics slow GI motility and may cause nausea. Normally, during the immediate recovery phase faint or absent bowel sounds can be auscultated in all four quadrants. Inspection of the abdomen rules out distension that may be caused by accumulation of gas. In a client who has had abdominal surgery, distension will develop if internal bleeding occurs. Distension may also occur in the client who develops a paralytic ileus from handling of the bowel in surgery. This paralysis of intestines with distension and symptoms of acute obstruction may also be related to the administration of anticholinergic drugs. This usually does not occur for 24 hours. The acute care nurse must be aware of the risk for paralytic ileus and observe for abdominal distension and reduction in bowel sounds.

The level of nausea should be regularly assessed as well as the effect of any interventions (e.g. administration of antiemetics). Because stomach emptying slows with the client under anaesthesia, the accumulated contents cannot escape, and nausea and vomiting develop. Normally a client does not receive fluids to drink in the PARU because of bowel sluggishness, with the risk of nausea and vomiting, and because of grogginess from general anaesthesia. If the client has an NGT on free drainage, the nurse assesses the output for amount and colour.

The client is likely to begin taking ice chips or sips of fluids when arriving in the acute care unit. If these are tolerated, diet can usually be commenced. In the case of some abdominal surgery, the bowel may need to be rested, and commencement of oral intake will not be indicated for several days.

Maggie Gordon, a 65-year-old woman, was admitted to your women’s health unit following a total abdominal hysterectomy for fibroids under a general anaesthetic. The post-anaesthesia recovery unit (PARU) nurse explains in hand-over that Maggie had a long stay in recovery because her pain was difficult to control, and she required a total of 20 mg of morphine IV titrated in 2 mg doses to achieve satisfactory pain relief. Otherwise she had an uneventful recovery and her vital signs remain stable. An IV morphine patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) device was initiated in the PARU with a prescription that allows Maggie to self-administer a 1 mg bolus dose every 5 minutes as needed, with no background infusion. Maggie’s husband and daughter are waiting in the room on admission.

Maggie opens her eyes and acknowledges the registered nurse’s request to assist with her transfer from the stretcher to the bed. During transfer to the bed Maggie moans and says her abdomen hurts, rating the pain intensity as an 8 on a scale of 0–10. Once settled in bed, she rates her pain as 7 and says she is mildly nauseated and then falls quickly back to sleep.

Your focused initial nursing assessment reveals the following:

• Pulse 80 beats/minute. Nail beds and general skin colour are pink.

• Respirations 12 breaths/minute; quiet, regular, shallow respirations. SpO2 99% on 2 L/minute oxygen via nasal prongs. Lung sounds equal and clear.

• Maggie is overweight with a disproportionately large neck; recorded body mass index (BMI) is 35.

• Her abdominal dressing is dry and intact. An indwelling urinary catheter is patent and draining clear urine. There is scant per vaginum loss.

• The PCA is piggybacked into a maintenance IV that is infusing Hartmann’s solution at 100 mL/h. The PCA pump program is verified to be correct. The PCA history shows 3 demands and deliveries, the last being 10 minutes ago.

The husband and daughter both express concern to you about the degree of pain that Maggie is experiencing and request that you give her additional pain medication.

Adapted from Pasero C 2011 Postoperative pain control: more opiods? Medscape www.medscape.com.

Comfort

As clients regain consciousness from general anaesthesia, the perception of pain becomes prominent. Pain can be perceived before full consciousness is regained. Acute incisional pain causes clients to become restless and may be responsible for changes in vital signs. It is difficult for clients to begin deep-breathing and coughing exercises when they experience pain. This is of particular significance for clients who have had abdominal, back or chest surgery, as the pain experienced will impede their ability to effectively perform these exercises, placing them at greater risk for chest infection. The client who has had regional or local anaesthesia usually does not experience pain initially, because the incision area is still anaesthetised.

Thorough assessment of the client’s pain and evaluation of pain-relief therapies are essential. Pain scales are an effective way for nurses to assess the severity of postoperative pain, evaluate response to analgesics and objectively document pain severity (see Chapter 41). Using preoperative pain assessments as a baseline, the nurse is able to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions throughout the client’s recovery.

It is common to administer opioid analgesics immediately after surgery for pain relief and to maximise the client’s ability to perform respiratory exercises such as deep-breathing and coughing. Initial analgesic doses are usually given IV in the PARU and titrated to client comfort. Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) may also be commenced. Many clients receive epidural analgesia that may be continued throughout the recovery period (see Chapter 41).

If the client has a PCA and is making attempts to use it more frequently than it is programmed for (the number of client demands is displayed on the machine) or pain is uncontrolled, the nurse should contact the acute pain team to change the order. The amount of medication the client can receive may be increased, the lockout period decreased or other medication may be commenced. As oral intake is tolerated, and dependent on the pain assessment, the client’s analgesia will usually be changed from IV to oral administration. Non-pharmacological interventions should also be implemented. An example is to lower the head of the bed and use a pillow for incisional splinting while turning a client with recent abdominal surgery.

• CRITICAL THINKING

1. What is the priority intervention to manage the patient’s pain in the clinical example above? Why would increasing the opioid dose be risky in this situation?

2. How could a multimodal analgesia approach (refer to Chapter 41) be used in this situation to add analgesia without producing any further sedation and increasing the potential for respiratory depression? Who would you contact about this prescription?

3. What non-pharmacological pain relief interventions would be appropriate for you to initiate in this situation?

4. How would you respond to Maggie’s family? What family teaching could you provide so that they can support Maggie’s recovery? What would you explain to them about the use of Maggie’s PCA?

NURSING DIAGNOSIS

The nurse evaluates the status of any problems identified from the preoperative nursing diagnoses and clusters new relevant data to ascertain if the diagnoses are still relevant postoperatively, modify any diagnoses or identify new ones. Previously defined diagnoses, such as impaired skin integrity, may continue as a postoperative problem (e.g. if the client has an incisional wound, then they clearly have impaired skin integrity). The nurse may also identify new risk factors leading to identification of nursing diagnoses (Box 44-6). For example, an older client who has undergone major abdominal surgery and who has a pre-existing problem of reduced hip mobility resulting from arthritis will have the nursing diagnosis of impaired physical mobility. The surgery itself may add risk factors for the client. The nurse also considers the needs of a client’s family when making diagnoses. For example, the inability of the family to cope with the client’s condition requires intervention.

PLANNING

When a client is recovering from surgery, the nurse has a great deal of assessment data and information to inform the planning of the client’s nursing care. The preoperative history, postoperative assessment data and the postoperative orders all inform the nurse to plan specific patient-centred nursing interventions. Typical postoperative orders include the following:

• frequency of vital-sign monitoring and any focused assessments (e.g. related to drain tubes, NGTs, IDCs)

• IV fluids and rates of infusion

• postoperative medications (especially those for pain and nausea)

• fluids and food allowed by mouth

• level of activity the client is allowed to resume

WORKING WITH DIVERSITY FOCUS ON OLDER ADULTS

Being aware of older adults’ special needs and addressing them early can reduce the incidence of postoperative complications.

• Hearing and vision loss—ensure that the patient uses their hearing aid and/or glasses. Miscommunication has the potential to have serious adverse consequences. For example, hearing and vision losses may lead to confusion, increased anxiety and non-adherence to plan of care, based on misunderstanding.

• Comorbidities—older adults may present with vague symptoms that mask serious underlying conditions. Be aware of the likelihood of cardiovascular, respiratory, renal and central nervous system disorders.

• Polypharmacy—older adults may be prescribed multiple medications. It is essential that all current medications are noted during the admission assessment. For elective surgery, client should be asked to bring all medications in with them.

• Hypothermia—older people are more vulnerable to hypothermia than other age groups. Hypothermia can result in serious physical and psychological consequences: renal concentrating ability, drug clearance, wound healing and tissue oxygenation requirements can all be seriously impaired by hypothermia. The older client must be kept warm by using warm blankets, patient-controlled warming gowns, warmed infusion fluids and/or heated, humidified inspired gases.

Multidisciplinary clinical pathways are commonly used to plan care for the surgical client, although these must be individualised for each client based on the registered nurse’s assessment and clinical judgment. The nurse considers the effects of the stress of surgery and the limitations it produces when establishing expected outcomes and interventions for the individual client. Measurable outcomes help to facilitate the evaluation of appropriate recovery from surgery. For example, the client with impaired mobility should have specific outcomes selected that may include walking at least 20 metres 4 times a day, performing range-of-movement exercises (as taught) on the relevant joint every 2 hours while awake, a pain level no greater than 3 (on a scale of 0–10), wound edges approximated and absence of wound infection, performing deep-breathing and coughing exercises correctly every 1–2 hours when awake. Outcomes can then be evaluated as to whether they were met and whether any modifications need to be made.

Typical broad goals of postoperative care include the following:

IMPLEMENTATION

Regaining normal physiological function

The principal causes of postoperative complications are a surgical wound, the effects of prolonged immobility during surgery and recovery/rehabilitation and the influence of anaesthesia and analgesics. Nursing management is directed at preventing complications so that the client returns to the highest level of functioning possible. Failure of the client to become actively involved in recovery adds to the risk of complications (Table 44-6). Virtually any body system can be affected. The nurse must consider the interrelationship of all systems and therapies provided.

TABLE 44-6 POSTOPERATIVE COMPLICATIONS

MAINTAINING RESPIRATORY FUNCTION

To manage risk and prevent respiratory complications, the nurse begins aggressive pulmonary measures preoperatively. The benefits of thorough preoperative education are realised when clients are able to participate actively. The following measures promote expansion of the lungs.

• Encourage diaphragmatic breathing exercises at least every 2 hours while client is awake. Maximal inspirations lasting 3–5 seconds open up alveoli.

• Instruct clients to use an incentive spirometer for maximum inspiration.

• Encourage early ambulation. Walking means that clients assume a position that does not restrict chest wall expansion and stimulates an increased respiratory rate.

• Assist clients who are restricted to bed to turn on their sides every 1–2 hours while awake and to sit when possible. Turning permits expansion of the lungs. Sitting causes lowering of abdominal organs, thus facilitating diaphragmatic movement and lung expansion.

• Keep the client comfortable. A client who is comfortable will be able to participate in the postoperative regimen. Assess, document, treat and evaluate the client’s pain and nausea levels.

The following measures promote removal of pulmonary secretions if they are present:

• Encourage coughing exercises every 1–2 hours while the client is awake and effectively manage pain to promote a deep, productive cough. Note that for clients who have had eye, intracranial or spinal surgery, coughing may be contraindicated because of the potential increase in intraocular or intracranial pressure.

• Maintain adequate hydration (e.g. with IV or oral fluids as tolerated) and provide oral hygiene to help thin and expectorate secretions. Secretions become thick and tenacious and the oral mucosa becomes dry when clients are NBM or are placed on limited fluid intake.

• Initiate orotracheal or nasotracheal suction for clients who are too weak or are unable to cough (see Chapter 40).

MAINTAIN CIRCULATORY FUNCTION

Nursing interventions aimed at preventing the risk of circulatory complications need to be implemented. Some clients are at greater risk of venous stasis because of the nature of their surgery and/or postoperative care. The following measures promote venous return and circulatory blood flow.

• Remind the client to perform leg exercises at least every hour while awake. Exercise may be contraindicated in an affected extremity involving vascular repair or realignment of fractured bones and torn cartilage.

• Apply antiembolism stockings as ordered. The stockings should be removed every 8 hours and left off for 1 hour (see Chapter 33).

• Apply pneumatic compression stockings as prescribed. Each stocking wraps around a client’s leg and is kept in place with a Velcro attachment. Compressed air inflates the padded plastic stocking systematically from ankle to calf to thigh, and then deflates. The alternating inflation and deflation of the stocking reduces venous stasis.

• Encourage early ambulation. Most clients are expected to walk the evening of surgery, depending on the severity of the surgery and their condition. Even if a client has an epidural catheter or PCA device, walking should be encouraged. The degree of activity allowed progresses as the client’s condition improves. Before walking, assess the client’s vital signs. Abnormalities may contraindicate walking. If vital signs are normal, assist the client to sit on the side of the bed and encourage them to wiggle their toes. Dizziness may be a sign of postural hypotension. Recheck blood pressure to determine whether walking is safe. Ensure that the client is steady when they first stand and walk by the client’s side. Evaluate exercise tolerance.

• Avoid positioning clients in a manner that interrupts blood flow to extremities. While in bed, clients should not have pillows or rolled blankets placed under the knees, as compression of the popliteal vessels can cause thrombi.

• Administer anticoagulant medication as prescribed. Anticoagulants, such as heparin, are often ordered for clients at risk of thrombus formation.

• Assess for adequate fluid intake, and when able to commence oral fluids encourage intake. Adequate hydration prevents concentrated build-up of formed blood elements, such as platelets and red blood cells. When the plasma volume is low, these elements may gather and form small clots within blood vessels.

PROMOTING ELIMINATION AND ADEQUATE NUTRITION

Interventions for preventing GI complications promote return of normal elimination and faster return of normal nutritional intake. It may take several days for a client who has had surgery on GI structures (e.g. a colon resection) to resume a normal diet. Normal peristalsis may not return for 2–3 days. In contrast, the client whose GI tract is unaffected directly by surgery can resume dietary intake after recovering from the effects of anaesthesia. The following measures promote return of normal elimination:

• Dependent on the surgery, the nurse may be required to assess for return of peristalsis. This involves auscultation of the abdomen to detect bowel sounds; 5–30 gurgles per minute over each quadrant indicate normal bowel sounds. Asking whether the client has passed flatus also indicates that peristalsis is returning. Abdominal distension should be reported to the medical officer.

• Maintain a gradual progression in dietary intake. A client having day-surgery may be able to eat and drink as soon as they wake from the anaesthetic. Some clients may receive only IV fluids for the first few hours after surgery. Once oral fluids and food can be commenced, it is sensible to encourage the client to start with water, progressing to clear fluids and a light diet (e.g. soup and sandwiches), as overloading with large amounts of fluids may lead to nausea and vomiting. Clients who have had abdominal surgery with interference to the bowel or GI tract are usually NBM for the first 24–48 hours. As peristalsis returns, clear fluids only may be ordered, followed by free fluids, then light food diet, and finally a regular diet.

• Promote walking and exercise. Physical activity stimulates a return of peristalsis. The client who suffers abdominal distension and ‘gas pain’ will often obtain relief while walking.

• Maintain an adequate fluid intake. Clients who have had surgery are often at a higher risk for constipation due to the side effects of pain medication and reduced mobility. Fluids keep faecal material soft for easy passage. Administer stool softeners and enemas as prescribed.

The following measures assist in maintaining an adequate dietary intake:

• Remove sources of noxious odours which may deter the client from eating.

• Assist the client into a comfortable position at meal-times. The client should sit if possible.

• Assist the client in selecting desired servings of food. For example, a client may be more willing to face the first meal when servings are small.

• Provide oral hygiene. Adequate hydration and cleansing of the oral cavity diminish dryness and bad tastes.

• Provide meals when the client is rested and free from pain. Often a client loses interest in eating if meal-time has been preceded by exhausting activities, such as walking, coughing and deep-breathing exercises or extensive dressing changes. When a client has pain, there may be associated nausea which will often cause a loss of appetite.

PROMOTING URINARY ELIMINATION

The depressant effects of anaesthetics and analgesics impair the sensation of bladder fullness and can cause urinary retention. If bladder tone is reduced, the client has difficulty voiding. However, clients should void within 8–12 hours after surgery. Clients who undergo surgery of the urinary system often have an IDC inserted to maintain free urinary flow until voluntary control of micturition returns. The following measures promote normal urinary elimination:

• If possible, considering the client’s medical condition, assist the client to assume their normal position when voiding. A male client may prefer to stand to void. A bedpan can make voiding difficult and a female client may prefer to use a toilet or bedside commode.

• Assess the client for the need to void. A surgical client restricted to bed needs assistance to handle and use bedpans or urinals. Often the client acquires a sudden feeling of bladder fullness and urgency to void and will need help quickly.

• Assess for bladder distension by palpating the lower abdomen above the symphysis pubis. A bladder scanner may be used to assess the volume of urine in the bladder. If a client does not void within 8 hours of surgery or bladder distension is present, it may be necessary to insert a urinary catheter so you need to notify the medical officer.

• Monitor intake and output. An accepted level of urinary output is at least 0.5–1 mL/kg/h for adults. If the urine is dark, concentrated and low in volume (< 30–60 mL per hour), the medical officer should be notified. A client can easily become dehydrated as a result of fluid loss from the surgical wound or a lengthy fasting preoperative period. Measure intake and output for several days after surgery until normal fluid intake and urinary output are achieved.

PROMOTING WOUND HEALING

A number of factors may affect surgical wound healing and place the client at risk for delayed healing, such as inadequate nutrition, impaired circulation and metabolic alterations (see Chapter 30). A wound may also undergo considerable physical stress. Strain on sutures from coughing, vomiting, distension and movement of body parts can disrupt the wound layers. The nurse has a role in promoting wound healing. If a wound becomes infected, the infection usually establishes itself 3–6 days after surgery. A clean surgical wound usually does not regain strength against normal stress for 15–20 days after surgery. The nurse uses aseptic non-touch technique during dressing changes and wound care (see Chapter 29). Surgical drains must remain patent so that accumulated secretions can escape from the wound bed. Assessment of the wound identifies early signs and symptoms of infection.

ACHIEVING REST AND COMFORT

A surgical client’s pain usually increases as the anaesthesia wears off. The incisional area may be only one source of pain. Irritation from drainage tubes, tight dressings or casts and the muscular strains caused from positioning on the operating-room table can make the client feel uncomfortable. As such, do not assume that expression of pain is only related to the incision.

Pain can significantly slow recovery. The client becomes reluctant to cough, breathe deeply, turn, walk or perform necessary exercises. The nurse assesses the client’s pain thoroughly (see Chapter 41) and ensures that interventions and therapies are adequate. If they are not, the nurse needs to collaborate with the acute pain service or medical staff to obtain more-effective pain relief. The nurse should also independently implement non-pharmacological interventions to promote pain relief, such as appropriate positioning that aids the client’s comfort, gentle back massage and use of hot or cold packs (if appropriate).

Epidural infusion of local anaesthetic and opioids, such as morphine or fentanyl via patient-controlled epidural analgesia (PCEA), is another common method for administering effective postoperative analgesia for many surgical clients. These medications may be delivered as a continuous infusion or a preprogrammed bolus dose or interval, or both. Epidural opioids relieve severe pain, often without the central nervous system depression that can occur with systemic opioids. Recognising potential complications and what to do if they occur is an important role for the postoperative nurse (see Chapter 41 on preventing and managing complications of epidural analgesia).

MAINTAINING/ENHANCING SELF-CONCEPT

The appearance of wounds, bulky dressings, bruising, extruding drains and tubes affects a client’s self-concept. The effects of surgery, such as disfiguring scars, may create permanent changes for the client’s body image. If surgery leads to impairment in body function, the client’s role within the family can change significantly.

The nurse observes clients for alterations in self-concept. Clients may show revulsion towards their appearance by refusing to look at incisions, carefully covering dressings with bedclothes or refusing to get out of bed because of tubes and devices. The fear of not being able to return to a functional role in their families may even cause clients to avoid participating in their plan of care.

The family and significant others are important to improving the client’s self-concept. The nurse explains the client’s appearance to the family in a way that avoids non-verbal expressions of revulsion or surprise. The family needs to accept the client’s needs and still encourage the client’s independence. If the condition is permanent, the family learns to help the client through the grieving process so that the client can reach a stage of acceptance. The following measures maintain the client’s self-concept:

• Offer opportunities for the client to discuss feelings about appearance. A client who avoids looking at an incision may need to discuss fears or concerns. Many clients may worry about permanent scarring. When the client chooses to look at an incision for the first time, the area should be clean. If necessary, the client should eventually be able to care for the incision site by applying simple dressings or bathing the affected area.

• Provide privacy during dressing changes or inspection of the wound and appropriately drape the client so that only the dressing or incisional area is exposed.

• Maintain the client’s hygiene. Wound drainage and antiseptic solutions from the surgical skin preparation dry on the skin’s surface and cause irritation. A bed bath following surgery facilitates client wellbeing. When the gown becomes soiled by wound drainage, offer a clean gown and washcloth. Keep the client’s hair neatly combed and offer frequent oral hygiene, especially for the client who is NBM. Room deodorisers may be useful if the odour from drainage seems particularly troublesome to the client and family.

• The client sometimes becomes preoccupied with observing the drains and gradual collection of drainage. Drains can leak if they become too full; change or empty the drains as per institution policy.

• Maintain an environment conducive to recovery. Self-concept is heightened by being in pleasant, comfortable surroundings. Often the room of a surgical client becomes cluttered with extra dressings, rolls of tape and bottles of antiseptic solution. If the client requires frequent dressing changes, the room may take on the appearance of a supply room. Store or remove unused supplies and keep the client’s bedside and room orderly and clean.

• Provide the family and significant others with opportunities to discuss ways to promote the client’s self-concept. Encouraging independence can be difficult for a family member who has a strong desire to help the client in any way. By knowing about the appearance of a wound or incision, family members can be supportive during dressing changes. The topic or tone of a conversation can also help family members distract a client from dwelling on fears and concerns. Family members should not avoid discussing the future. However, they need help to know when it is appropriate to discuss future plans. This makes it possible for the client and family to work together to discuss realistic plans for the client’s return home.

• CRITICAL THINKING

Mrs Yao, an 82-year-old woman, was admitted to your orthopaedic unit after a fall at home resulting in a fractured neck of femur. Mrs Yao was born in China and lived there for over 50 years. She speaks very little English. Mrs Yao lives with her son, and those she sees socially are also Chinese. Mrs Yao is scheduled for a surgical repair (open reduction internal fixation) of the fractured femur.

1. Discuss the cultural considerations that may be relevant when caring for Mrs Yao.

2. Outline the postoperative complications which are relevant in the older client undergoing this type of surgery.

3. Decide on what nursing care you would provide to reduce the risk of these complications, both in the preoperative period and in the postoperative period. Ensure that you provide scientific rationales for the care identified.

EVALUATION

Client care

The nurse evaluates the effectiveness of care provided to the surgical client on the basis of expected outcomes of nursing interventions. In all acute settings, the nurse consults with the client and family to gather evaluation data. The nurse can evaluate the same-day surgery client’s outcomes by making a telephone call to the client’s home to follow up on the client’s recovery and see whether the client understands restrictions or medications. The call is usually placed 24 hours after surgery, which allows the nurse to evaluate the progress of recovery.

In an acute care setting, the evaluation of a surgical client is ongoing. If a client fails to progress as expected, the nurse revises the client’s plan of care based on the priorities of the client’s needs. Every effort is made to assist the client to return to an optimal functional status.

Part of the nurse’s evaluation is determining the extent to which the client and family have learned self-care measures. A client often has to continue dressing care, follow activity restrictions, continue medication therapy and observe for signs and symptoms of complications on returning home. Clients who are unable to perform self-care activities and who lack support may be referred to home healthcare agencies, or admitted to rehabilitation facilities. A comprehensive discharge summary should be provided to ensure continuity of care.

Client expectations

With short hospital stays and same-day surgery, it is especially important to evaluate client expectations early in the postoperative process. Pain relief is usually a priority in the surgical population. Asking clients whether they are satisfied with their pain relief and assessing the effectiveness of the interventions can determine whether the client’s needs have been met. Timeliness of response to the client’s needs, such as scheduled times for pain medication and prompt answering of a call light, may increase satisfaction. The client usually wants to be discharged from acute care as soon as possible and when indicated by the surgeon. Ensuring that discharge plans are in place facilitates that process and enhances the client’s satisfaction with care. A phone call to the client 24 hours after same-day surgery or after discharge from acute care provides reassurance that the healthcare team is concerned with progress towards a return to the pre-surgical state of wellness.