Chapter 48 Drugs Affecting the Skin

The skin is the largest organ of the body; together with the hair and nails it forms the integumentary system. It serves as a barrier against the environment, protects underlying tissues, helps regulate body temperature and produces vitamin D. Drugs may be administered via topical and systemic routes for treatment of skin conditions or may be applied to the skin intended for transcutaneous absorption and systemic action. This chapter reviews the various formulations and topical products available and indications for their use. Groups of drugs that commonly cause adverse reactions in the skin are listed.

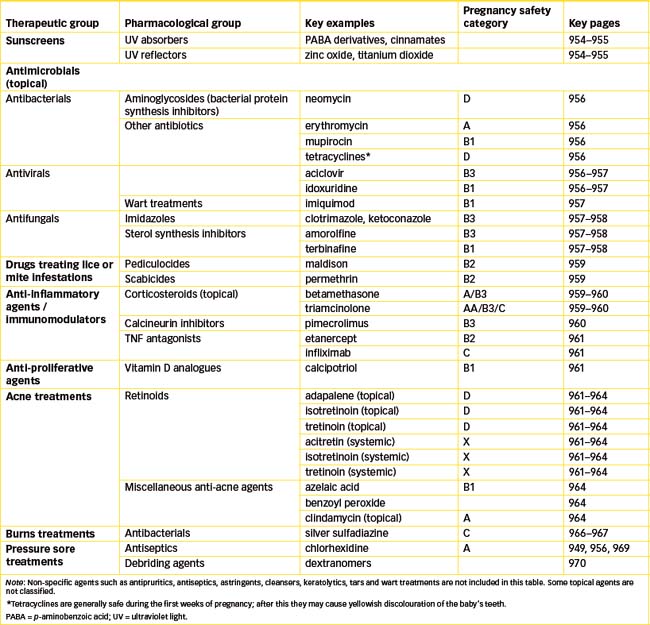

Drugs commonly applied to the skin include sunscreen preparations, antimicrobials, anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressant agents and drugs used in the treatment of acne, burns, pressure sores and leg ulcers. Their pharmacological actions, clinical uses and adverse effects are described.

Key abbreviations

Key background: structure, functions and pathologies of the skin

THE skin (or integument) has been described as the largest organ in the body. As the tissue most at risk of environmental damage, the skin often becomes infected, inflamed or impaired by antigens, mechanical injury or radiation. Medications for most diseases are administered at a site distant from the target organ, but in dermatology, medications can readily be applied directly to the target site. In addition, lipid-soluble drugs can be applied to the skin with the intention that they will be absorbed into the systemic circulation to act at distant sites, and drugs can be administered systemically to treat skin disorders.

Structure and functions of the skin

The skin is made up of two main layers, the epidermis and the dermis.

Epidermis

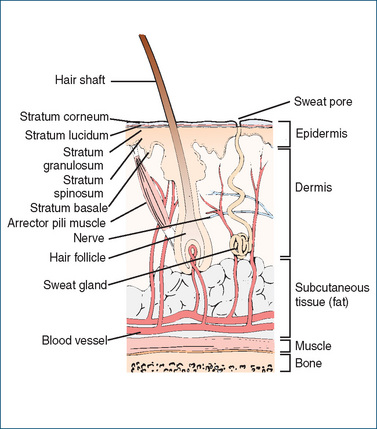

The epidermis, or thin outer skin layer, has no direct blood supply of its own; it is nourished only by diffusion. It consists of four layers of epithelial cells (see Figure 48-1):

Figure 48-1 Structures of the skin.

Note: Details of nerves (autonomic and sensory) and sensory nerve endings are not shown.

Melanocytes, which are responsible for synthesising melanin, a pigment that occurs naturally in the hair and skin, are also located deep in the stratum germinativum. The more melanin that is present, the deeper brown the skin colour. Melanin is a protective agent: it blocks ultraviolet rays, thus preventing injury to the underlying dermis and tissues.

Dermis

The dermis lies between the epidermis and subcutaneous fat. It is about 40 times thicker than the epidermis and contains elastic and connective tissues that provide support for its blood vessels, nerves, lymphatic tissue, sweat glands, sebaceous glands and hair follicles.

Below the dermis is the hypodermis, or subcutaneous layer, which contributes flexibility to the skin. Subcutaneous fat tissue is an area for thermal insulation, nutrition and cushioning or padding.

The skin contains three types of exocrine glands opening on the surface of the skin through ducts in the epithelium: sebaceous (producing lubricating sebum), eccrine (producing sweat and helping cooling) and apocrine (producing odoriferous compounds). Normal skin pH is 4.5–5.5, which is weakly acidic and hence has a protective and antiseptic function. The appendages of the skin are the hair and nails.

Functions of the skin

The skin serves many functions in the body; some of the major functions are listed here.

Protection

The skin forms a protective covering for the entire body. As the old song puts it, ‘Skin’s what keeps your insides in’ and, more importantly, keeps the outsides out. Thus it is a barrier against microorganism invasion, chemicals, loss of water and heat and physical abrasion.

Sensation

Nerve endings permit the transfer of sensations, such as heat, cold, touch, pressure and pain.

Body temperature regulation

Skin helps maintain body temperature homeostasis by regulating heat loss or heat conservation. Blood vessels in the dermis area can dilate, and perspiration increases when the body temperature is elevated, encouraging evaporative cooling. If the body temperature is below normal, the skin blood vessels constrict and perspiration is decreased.

Body image

Skin (and hair) contributes to the concept of body image and a feeling of wellbeing. A disfiguring or chronic skin condition such as psoriasis, acne or alopecia can lead to emotional problems and depression.

Absorption, metabolism and excretion

Skin excretes fluid and electrolytes (via sweat glands), stores fat and synthesises vitamin D: when skin is exposed to sunlight or ultraviolet rays, the steroid 7-dehydrocholesterol, which is normally present in the skin, is converted to vitamin D3 (see Figure 33-3G, and Clinical Interest Box 37-2). Skin can also be a site for absorption of drugs, fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E and K), oestrogens, corticosteroid hormones and lipid-soluble agents (see Clinical Interest Box 48-1).

Clinical Interest Box 48-1 Poisoned through the skin!

Some of the most toxic agents liable to be absorbed through the skin are the organophosphorus anticholinesterases, such as dyflos and malathion (now known as maldison). These were intended to be highly lipid-soluble, as they were developed to be absorbed through the lungs and skin of humans (as war gases) or through the cuticle of insects (as insecticides). Cases of toxicity occurring after transdermal absorption of these agents are quite common, e.g. in chemical workers, pest controllers and gardeners.

A case was reported in Melbourne in 1997 of an ambulance transporting an elderly man who had accidentally ingested insecticide solution (metasystox), mistaking it for a cough mixture. One of the ambulance officers also became dizzy, disoriented and nauseous from the fumes in the ambulance; he had been poisoned indirectly both by handling the clothing and by inhaling fumes escaping through the skin of the patient. Both patient and ‘ambo’ were successfully treated.

Source: The Age, Melbourne, 11 April 1997.

Skin disorders

Causes of skin disorders

Disorders of the skin may be due to allergy, infection, sensitivity to drugs or other chemicals, emotional stress, genetic predisposition (e.g. atopic eczema or psoriasis), hormonal imbalances or degenerative disease. Sometimes the cause of the skin disorder is unknown and the treatment is empirical, in the hope that the right remedy will be found; corticosteroids are often used in skin disorders for their anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressant actions.

Chemicals causing skin disorders

Table 48-1 is a summary of the vast range of dermatological reactions caused by chemicals (including drugs); some of these can be life-threatening, with high fever, pharyngitis, neck stiffness and epidermal necrolysis. It is important to be aware of the patient’s drug history and current therapy in order to relate such reactions to the appropriate cause, as simply discontinuing a particular drug may resolve a complicated dermatological problem of unknown origin.

Table 48-1 Drugs and other chemicals commonly causing dermatological conditions

| Skin condition | Description of pathology | Drugs & other chemicals potentially involved |

| Exfoliative dermatitis | Skin is inflamed, red and scaly & will eventually slough off; hair & nails may also be affected; hyperkeratosis, pruritis & physiological dysfunctions may occur. Eruption may take weeks or months to resolve after causative agent is stopped; can be fatal | Amiodarone, barbiturates, carbamazepine, frusemide, gold salts, griseofulvin, nifedipine, penicillin, phenothiazines, phenytoin, sulfonamides, tetracyclines |

| Stevens–Johnson syndrome (erythema multiforme) | Severe form involves widespread mucocutaneous lesions usually on face, neck, arms, legs, hands & feet. May also involve fever, haemorrhagic crusts, ocular lesions leading to blindness & multi-system involvement; can be life-threatening | Many drugs, especially carbamazepine, penicillins & cefalosporins, phenytoin, sulfonamides, tetracyclines |

| Lupus erythematosus | Autoimmune connective tissue disorder; erythematous rash may be flat or elevated on cheeks and across nose (butterfly); joint swelling & pain, rash, oral ulcers, serositis; renal, haematological, pulmonary & other systems may be affected. Reversible when drug is stopped | Hydantoins, hydralazine, isoniazid, procainamide, quinidine |

| Acneiform reaction | Reddened skin lesions resembling acne, an inflammatory disease of the pilosebaceous unit (hair follicle & sebaceous gland) | ACTH, androgenic hormones, corticosteroids, cyanocobalamin, hydantoins, iodides, oral contraceptives |

| Purpura | Multiple small haemorrhages in the skin and mucous membranes | ACTH, allopurinol, amitriptyline, anticoagulants, corticosteroids, digoxin, fluoxymesterone, gold salts, griseofulvin, iodides, nifedipine, paracetamol, penicillins, phenothiazines, quinidine, sulfonamides, thiazides |

| Urticaria | Skin oedema and wheals due to vasodilation & increased capillary permeability; may be immune-mediated | Aciclovir, amitriptyline, cefalosporins, chloramphenicol, chlorhexidine, enzymes, erythromycin, gold salts, griseofulvin, hydantoins, insulins, iodides, nitrofurantoin, opioids, penicillins, phenothiazines, salicylates, streptomycin, sulfonamides, tetracyclines, vaccines |

| Alopecia | Lack or loss of hair from area of skin where hair is normally present; baldness | Alkylating agents, anticoagulants, antimetabolites, antitumour antibiotics, heparin, lithium, norethisterone, spironolactone |

| Lichenoid reactions | Skin lesion resembling lichen, i.e. small, firm papules set close together | Chloroquine, gold salts, nifedipine, quinidine, thiazides |

| Fixed drug eruptions | Circumscribed inflammatory bullous or vesicular skin lesion that recurs at same site in response to administration of a drug, often with itching or burning, with rapid resolution after stopping the drug, possibly leaving residual pigmentation | Antihistamines, atropine, atorvastatin, barbiturates, bismuth salts, chloral hydrate, chlorpromazine, digoxin, disulfiram with alcohol, ergot alkaloids, eucalyptus oil, gold compounds, griseofulvin, iodine, opioids, penicillins, phenytoin, quinidine, quinines, salicylates, saccharin, streptomycin, sulfonamides, tetracyclines, vaccines |

| Contact dermatitis or eczema | Inflammation of the skin due to contact with a substance; may have allergic or irritant mechanism; allergic eczema = atopic dermatitis | Antihistamines, antiseptics, aspirin, bleomycin, captopril, cefalosporins, chloramphenicol, chlorpromazine, cosmetics, formaldehyde, glyceryl trinitrate, gold salts, iodine, lanolin, local anaesthetics, miconazole, neomycin, paraben preservatives, penicillins, peru balsam, phenol, quinines, streptomycin, sulfonamides, tetracyclines, transdermal patches |

| Photosensitivity | Abnormal response of the skin to sunlight or artificial light at wavelengths 280–400 nm; it may be photoallergy or phototoxicity | Amiodarone, anaesthetics (procaine group), antihistamines, antimalarials, barbiturates, benzene, bergamot (perfume), carbamazepine, carrots (wild), celery, chlorhexidine, chlorophyll, citrus fruits, clover, coal tar, corticosteroids (topical), desipramine, dill, disopyramide, dyes (fluorescein, methylene blue, toluidine blue), fennel, 5-fluorouracil, gold salts, grass (meadow), griseofulvin, haloperidol, mercaptopurine, methoxsalen, methoxypsoralen, mustards, naphthalene, oils (cedar, lavender, lime, sandalwood, vanillin), oral contraceptives, p-aminobenzoic acid, parsley, parsnips, phenolic compounds, phenothiazines, phenytoin, porphyrins, quinines, salicylates, silver salts, sulfasalazine, sulfonamides, sulfonylureas, sunscreens, tetracyclines, thiazide diuretics, toluene, tricyclic antidepressants, xylene |

Signs and symptoms

Common dermatological disorders include acne vulgaris (cystic acne and acne scars), atopic dermatitis, eczema, folliculitis, fungal infections, herpes simplex, lichen simplex, psoriasis, seborrhoeic dermatitis, skin cancers, verrucae (warts) and vitiligo. Reactions or disorders of the skin are manifested by symptoms such as itching, pain or tingling and by signs such as swelling, redness, papules, pustules, blisters and hives.

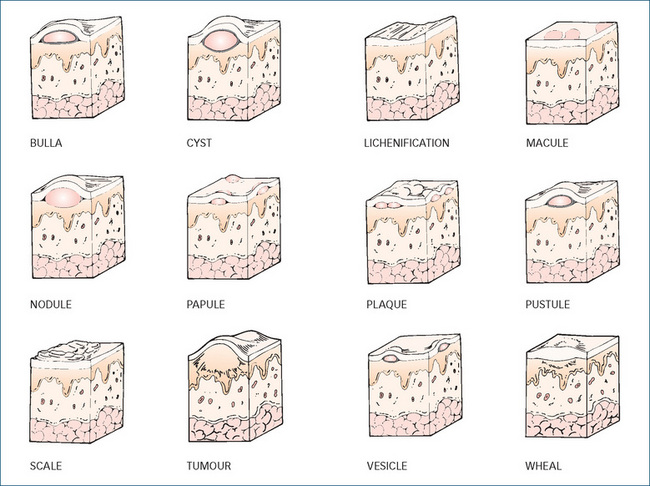

Dermatological diagnosis may require physical assessment; personal and family medical history; drug history including over-the-counter (OTC) medications; and laboratory tests, cytodiagnosis and biopsy. When the nature of the lesion has been established, its characteristics should be defined according to size, shape, surface and colour (Figure 48-2) and distribution on the body.

Figure 48-2 Different types of skin lesions and some conditions associated with them. Bulla: large vesicle containing serous fluid (examples: blister; pemphigus vulgaris). Cyst: elevated encapsulated cavity lined by epithelium; filled with liquid or semisolid material (example: sebaceous cyst). Lichenification: rough, thickened epidermis; accentuated skin markings due to rubbing or irritation (example: chronic dermatitis). Macule: flat; non-palpable; discoloured lesion, brown, red, purple or white (examples: freckle; flat mole; rubella; rubeola). Nodule: small collection of tissue, elevated; circumscribed; palpable; 1–2 cm in diameter (examples: erythema nodosum; lipoma). Papule: elevated; palpable; circumscribed; less than 1 cm in diameter (examples: wart; drug-related eruption; pigmented naevus; eczema). Plaque: elevated; flat-topped; solid; rough; superficial papule greater than 1 cm in diameter (examples: psoriasis; eczema). Pustule: visible collection of pus within or beneath epidermis; vesicle filled with purulent fluid (examples: impetigo; acne). Scale: irregular, thin, compacted flaky keratinised cells; dry or oily; varied size; silver, white, or tan (examples: psoriasis; exfoliative dermatitis). Tumour: elevated swelling; may or may not be clearly demarcated or differ in skin colour; growth is uncontrolled (examples: basal cell carcinoma; malignant melanoma). Vesicle: small, elevated, circumscribed, superficial sac filled with serous fluid; (examples: blister; varicella). Wheal, hives: smooth, slightly elevated, irregular-shaped area of oedema; solid, transient, often itchy (examples: urticaria; insect bite).

Source: Beare & Myers 1998; Dorland 2003.

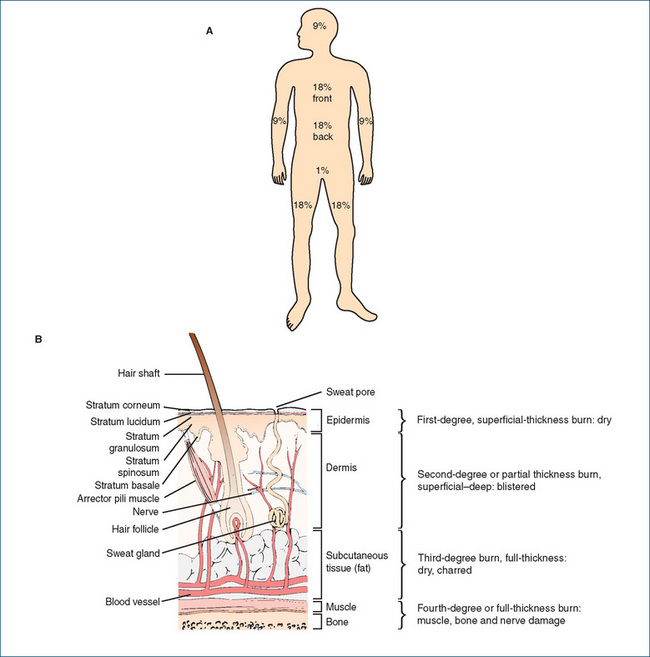

Skin conditions vary over time. Acute conditions tend to show red, burning, blistered or weeping skin (such as from burns); thick ointments cannot be applied to these lesions, which are best treated with lotions that cool by evaporation. Subacute conditions may be oedematous, hot and chapped; creams and gels can be applied. Chronic skin conditions tend to be scaling, lichenified, crusting and dry; moisturising creams and ointments may soften such skin.

Application of drugs to the skin

The general objectives of treatment of skin disorders are to:

Topical administration of drugs

Drugs may be administered to the skin for a topical or local effect, or with the intention that the drug be absorbed and have systemic actions elsewhere in the body. Even drugs that are applied for local actions may be absorbed, and systemic effects and toxicity can occur.

How much to prescribe?

How much of a topical preparation is needed for one dose? This is less easy to estimate than the quantity of tablets or other solid dose forms. Current guidelines suggest that for a cream or ointment to cover an adult’s face and neck would require about 1.25 g for one application, so twice-daily application for 10 days would require a 25–30 g tube of cream. Another way to calculate is to follow the guidelines of the Australian Medicines Handbook, where it is suggested, for example, that for a 3–5-year-old child, twice-a-day application of a topical ointment for 1 week would require 10 g for the face and neck, 15 g for arm and hand, 20 g for leg and foot etc. Some creams are provided in a tube with dose advised by mm or cm of cream squeezed out; other prescribers might recommend ‘enough to cover a 10 cent coin’ or similar suggestion.

Hydration of skin

Keratin in the outer skin layer provides a waterproof barrier; to enhance drug absorption the epidermis needs to be hydrated. Some medications are therefore applied then covered with an occlusive dressing (such as plastic wrap, rubber gloves or shower cap; see Figure 48-3 later) or administered in an occlusive type of ointment (e.g. zinc cream or petroleum jelly) because both will trap and prevent water loss (sweat) from the skin, thus increasing epidermis hydration.

Transcutaneous absorption of drugs

Skin layers to be crossed

For transcutaneous absorption (aka percutaneous absorption) of drugs into the bloodstream, the layers of skin cells and membranes through which drugs must pass are:

Nicotine, hyoscine, oestrogens, fentanyl and glyceryl trinitrate are formulated in ointments or patches for transdermal absorption. Chemicals can also be absorbed unintentionally across the skin, with unexpected consequences (see case history in Clinical Interest Box 48-1).

Factors affecting transcutaneous absorption

Absorption through the skin is slow, incomplete and variable (except for lipid-soluble agents). The extent of absorption depends on:

Larger molecules and more water-soluble drugs can have their permeation through the skin enhanced by physical methods such as iontophoresis, ultrasound and skin abrasion.

Formulations and medications for topical application

There are many more types of formulations for topical administration than for any other route (see below). This is the field of pharmaceutics, and detailed methods of formulation are beyond the scope of this text.

Vehicles and emulsions

The drug is dissolved or mixed into a vehicle, i.e. the liquid or solid which carries the drug to the site of application on the skin. Many formulations are emulsions (liquid or semi-solid mixtures of an aqueous phase and an oily phase, with one phase distributed as tiny droplets in the other).1 A lipid-soluble drug such as oestradiol, nicotine or glyceryl trinitrate will distribute into the oily phase of an emulsion, whereas a water-soluble drug (diphen hydramine, lignocaine) will distribute into the aqueous phase. Microemulsions, with nanoparticle-sized droplets, are being formulated to increase markedly the surface area for delivery of the drug to the skin.

Wet or dry preparations

Some topical formulations or vehicles may provide a useful effect without an active ingredient—simply rubbing in or dabbing on may have a warming or drying effect. The old saying in dermatology was ‘If it’s wet, dry it; if it’s dry, wet it’. For dry, scaly skin as found in psoriasis or dry eczema, an ointment with an occlusive emollient (softening) effect is helpful, such as lanolin or zinc cream. An area of acute inflammation that is oozing often needs a soothing evaporative lotion such as aluminium acetate solution or calamine lotion or a powder. If the skin lesion is painful, wet and located on an area rubbed by clothing, then a dusting powder such as talcum or starch may be appropriate to reduce friction and help dry the area. However, it has been shown that lesions heal better with less scarring when kept moist, so the current emphasis is on moist wound healing, e.g. under a medicated dressing (described later under ‘Treatment of pressure sores’).

Multiple ingredients

Pharmaceutical formulations for topical administration may include a wide range of ingredients, such as ointment or cream bases, water, suspending agents, emulsifying agents, preservatives, antioxidants, thickening agents, long-chain fatty acid esters and alcohols, colouring agents and perfumes, as well as the active drug. For example, one commercial ‘lip revitaliser’ contains 38 listed ingredients plus flavours! (It has been said that calamine lotion may make a lot of mess without doing a lot of good. This could be said of many old-fashioned topical preparations, which may remain in the pharmacopoeia without ever having been subjected to controlled clinical trials of safety and efficacy.)

Formulations and agents

Antipruritic agents

Antipruritics (preparations that relieve itching) include dilute solutions containing phenol, menthol, pine tar, potassium permanganate, aluminium subacetate, boric acid or physiological saline solution. Lotions such as calamine or calamine with phenol, cornstarch or oatmeal baths, and hydrocortisone lotion or ointment may also be used. Local anaesthetics such as benzocaine can decrease pruritus, but they readily induce allergic reactions. Antihistamines are poorly absorbed topically, so are less useful than might be expected in relieving allergic and itchy conditions unless administered systemically.

Antiseptics

Antiseptics (or skin disinfectants) are products that reduce the microbial flora on the skin; they are generally broadspectrum but not active against spores. Examples are chlorhexidine, cetrimide, benzoyl peroxide, povidoneiodine and triclosan (see also Appendix 2).

Astringents

Astringents are solutions which, when applied topically, cause precipitation of proteins, vasoconstriction and reduced cell permeability; examples are aluminium acetate or calcium hydroxide solutions, calamine lotion, hama melis (witch hazel), potassium permanganate and the alcohol vehicle in aftershave lotions.

Baths and soaks

Baths and soaks are used to cleanse or medicate the skin or to reduce temperature, usually with soap and water or with oils that have a moistening and soothing effect. Water generally has an antipruritic (anti-itch) effect, as well as cooling and drying by evaporation. Soaps have a detergent and drying action and can be very alkaline.

Cleansers

These are usually free of soap or are modified soap products that are recommended for people with sensitive, dry or irritated skin, or for those who have had a previous reaction to a soap product. Soap-free cleansers are less irritating, may contain an emollient substance and may also have been adjusted to a less alkaline or neutral pH.

‘Cosmeceuticals’

This (dreadful) term, combining ‘cosmetic’ and ‘pharmaceutical’, has been coined to refer to preparations developed with the hope of pharmacological efficacy in reversing the effects of ageing on the skin and restoring a youthful appearance. Preparations containing epidermal growth factors with antioxidants, skin conditioners and ‘matrixbuilding agents’ are sold at great expense, with little evidence of efficacy.

Creams and ointments

Creams and ointments are thick semisolid preparations to be smoothed onto the skin; they may consist of one phase (usually oily, as in ointments) or may be emulsions, i.e. two-phase preparations (creams). Water-in-oil (W/O) creams, such as lanolin, zinc cream and cold cream, feel greasy, are occlusive and help retard water loss through the skin; they effectively deliver lipid-soluble drugs to the skin. Oil-in-water (O/W) preparations, such as aqueous cream and vanishing creams, have cooling and moisturising effects, are good vehicles for water-soluble drugs, but are more easily washed off. Creams and ointments have emollient and protective properties and may be used as the vehicle for active drugs, e.g. eye ointments containing antibiotics or anti-inflammatory agents, and aqueous cream as a base for drug application to the skin.

Emollients

Emollients are fatty or oily substances that are used to soften or soothe irritated skin or as a vehicle for other drugs. Examples of emollients include lanolin, petroleum jelly (Vaseline), soft paraffins, silicones (e.g. dimethicone), oils, vitamin A and D ointments and aqueous cream.

Gels

Gels are viscous, non-oily, water-miscible, semi-solid preparations that contain gelling agents; they have a cooling effect as the solvent evaporates and leave a film on the skin.

Keratolytics

Keratolytics (keratin dissolvers) are drugs that soften skin squames (scales) and loosen the outer horny layer of the skin. Salicylic acid (5%–20%), resorcinol, alpha-hydroxy acids and urea have been the drugs of choice; newer agents used to remove solar keratoses are diclofenac 3% gel, fluorouracil 5% cream or imiquimod 5% cream. Their action makes the penetration of other medicinal substances easier. Keratolytics may be used in treatment of psoriasis, eczema, ichthyosis, warts, corns, acne and dandruff. Salicylic acid is used at concentrations up to 20% in ointments, plasters or collodion; higher concentrations are used to remove warts and corns. In treatment of dandruff, a type of seborrhoeic dermatitis of the scalp, shampoos may contain active ingredients such as coal tar, pyrithione zinc, selenium sulfide, an imidazole antifungal agent and Aloe vera (see Clinical Interest Box 48-2).

Clinical Interest Box 48-2 Sydney university’s aloe vera: ancient plants with modern uses

The University of Sydney’s huge Aloe vera plants, growing along the Parramatta Road boundary, fascinated generations of students and locals. Aloe vera, the Cape aloe, and Aloe barbadensis, the Barbados or Curacao aloe, are members of the lily family. Aloe vera was originally called Aloe ferox (ferocious); it looks like enormous cactuses with thick spiky leaves and can grow to 10–20 m in height, with stems as thick as 3 m in circumference. Aloes currently have become trendy in topical formulations, as natural products.

Aloes (i.e. the reddish-brown, brittle, glassy solid deposit that remains after evaporation of the exudate from cut leaves) have been a valuable commodity since the Greek and Roman empires, when they were traded from Africa along with tortoiseshell, myrrh and other spices. There are records dating back to the 9th century AD of trade from China and Sumatra (Indonesia) via Arabia and Persia to Europe, with aloes, camphor, cloves, cardamom and sandalwood being highly prized. Aloes are also mentioned in the visions of the 12th century mystic, healer and composer Hildegard of Bingen (Germany). In traditional Chinese medicine, the juice is squeezed from the thick, succulent leaves, then boiled and stored; it is used ‘to purge faeces, to clear heat in the liver and to kill worms’.

Aloin, the alcoholic extract of the leaf exudate, contains glycosides called anthraquinones, mono- and polysaccharides, lignans, sterols, salicylic acid and many vitamins and minerals. The extract has an enormously wide range of claimed medicinal properties, including laxative, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, immunostimulating and wound healing effects. It has again become very popular and is widely used particularly for treatment of skin conditions such as burns, ulcers, frostbite, psoriasis and dermatitis. Its more traditional uses are for constipation, dyspepsia, GIT ulcers and irritable bowel syndrome. Aloe vera is present in a wide range of commercial topical medicinal and cosmetic preparations such as creams, lotions, skin washes, shampoos and cleansers.

Sources: Braun & Cohen 2007; Bellamy & Pfister 1992.

Keratoplastics

These are agents that stimulate the epidermis and thus cause thickening of the cornified layer; examples are coal tar and sulfur preparations and low concentrations (1%–2%) of salicylic acid.

Liniments and rubs

These are indicated for pain relief for intact skin; pain caused by muscle aches, neuralgia, rheumatism, arthritis and sprains usually responds to these products. Simply massaging an oily substance into the skin causes dilation of skin blood vessels and has a rubefacient (reddening) effect and may assist healing. The ingredients in the preparations may include a counter-irritant (e.g. camphor or oil of cloves), an antiseptic (chloroxylenol, eugenol, thymol), a local anaesthetic (benzocaine) or analgesic (salicylate-containing substances such as methyl salicylate, aka Oil of Wintergreen).

Lotions and solutions

Liquid preparations have soothing and cooling effects due to their evaporation. They may be suspensions of an insoluble powder that is left behind on the skin, such as calamine lotion, or they may be mild acidic or alkaline solutions, such as boric acid solution, limewater or aluminium acetate, used as wet dressings and soaks. Aluminium acetate solution (Burow’s solution) is a mild astringent that coagulates bacterial and serum protein. It is diluted with 10–40 parts water before application.

Calamine lotion contains calamine (a powdered mixture of zinc carbonate and ferric oxide), zinc oxide, bentonite (a suspending agent), phenol and glycerol in a sodium citrate solution. It is a soothing, drying and mildly astringent lotion used for the dermatitis caused by plant secretions, insect bites, sunburn and prickly heat.

Pastes

These are very thick mixtures of solids in cream or oint ment bases. Magnoplasm is a commercial magnesium sulfate and glycerin paste with very high osmotic pressure, used to withdraw fluid from lesions such as boils.

Patches

A transdermal patch is rather like an adhesive dressing that has a reservoir of active drug incorporated in the dressing behind a rate-controlling polymer membrane designed to deliver the drug to the skin at a specified rate (see Figure 23-2). Patches are useful for delivery of potent lipid-soluble drugs, such as glyceryl trinitrate, oestradiol, fentanyl or nicotine. They eliminate many variables affecting oral absorption, including gastric emptying time, stomach acidity, presence of food and the first-pass effect; and obviate the need for frequent oral dosing.

Powders

Powders are mixtures of finely divided drugs in a dry form. Dusting powders based on talcum, zinc oxide or starch are intended for external application. They are useful in body fold areas, where they reduce friction and promote drying, and are used as vehicles for antimicrobial agents, especially antifungals for application to the feet.

Preservatives

These are chemicals added to aqueous formulations to retard oxidation or microbial growth. Common preservatives are hydroxybenzoates, alcohols, chlorocresol and benzalkonium chloride. Preservatives can frequently cause contact dermatitis. Preparations such as ointments and pastes with very little or no water usually do not pose a problem with respect to microbial growth (because of their high osmotic pressure) and hence do not require preservatives.

Protectants

Skin protectants are soothing, cooling preparations that form a film on the skin. They are used to coat minor skin irritations or to protect the person’s skin from chemical irritants. They can also help healing by preventing crusting and trauma.

Examples are Compound Benzoin Tincture (see below) and Collodion, a 5% solution of pyroxylin in a mixture of ether and alcohol; the solvents evaporate to leave a transparent, protective film that adheres to the skin. Non-absorbable powders (including zinc stearate, zinc oxide, certain bismuth preparations, talcum powder and aluminium silicate) are also protectants; however, they adhere to wet surfaces and may have to be scraped off.

Psoralens

Psoralens are plant constituents that have been known for centuries to induce pigmentation in skin, and are used for treatment of vitiligo, a condition in which there is patchy whitening of the skin and hair. They are photosensitising agents that absorb ultraviolet radiation (UVR), so are also used in conjunction with exposure to UVR in treatment of psoriasis. An example is methoxsalen (aka 8-methoxypsoralen), given orally or applied as a lotion or wash, 1–2 hours before exposure to UVR in phototherapy procedures.

Rubefacients

‘Rubefacient’ means ‘making red’—simply rubbing an inert lubricant such as an oil or cream into the skin can cause a mild inflammatory response with vasodilation and warmth and can act as a counter-irritant, distracting the mind from another itch or pain. Many ointments or creams, even with ingredients such as salicylates or antihistamines, have no proven pharmacological efficacy when applied topically, simply acting as rubefacients.

Soaps

Ordinary soap, the sodium salt of palmitic, oleic or stearic acids alone or in a mixture, is made by saponifying fats or oils with alkalis. The consistency of the soap depends on the acid and alkali used. All soaps are relatively alkaline and are potential sources of skin irritation, as are perfumes or antiseptics added to soaps. Soaps are irritating to mucous membranes and can be used in enemas.

Sprays

Sprays are fine mists or aerosols of drug in solution, often with a propellant gas. The vehicle evaporates and deposits the drug on the skin or mucous membrane. Sprays are used especially in the nose for topical administration of decongestants and antihistamines. Nasal sprays can also be utilised to administer drugs for systemic absorption, including hormones such as desmopressin, a posterior pituitary hormone (see Drug Monograph 33-3).

Tars

Extracts of coal tar, wood tar or bitumen are mild irritants to the skin, reduce epidermal thickness, suppress DNA synthesis and have antipruritic and antiseptic properties. Examples are coal tar solution, dithranol and ichthammol. They are used in treatment of dermatoses, including eczema, psoriasis and dandruff. Topically applied tars appear to be safe, whereas ingested or inhaled tars (such as from occupational exposure or cigarette smoking) can be carcinogenic. Tars should be kept away from sensitive areas of skin such as the face, groin, eyes and mucous membranes; some tar solutions stain the skin and clothes.

Tinctures

Tinctures are alcoholic solutions of chemicals or extracts of plant products. When the tincture is applied to the skin, the alcohol evaporates, leaving the ingredient on the skin. Alcohol has an astringent effect and can cause stinging of raw or damaged surfaces.

Compound Tincture of Benzoin (also known as Tinct Benz Co or Friar’s Balsam) is an alcoholic solution of three balsams (i.e. dried exudates from the cut stems of plants) and of aloes. It is administered as a paint or spray for its antiseptic, protective and styptic properties, and as an inhalation for upper respiratory tract infections.

Wet dressings

These liquids include some of the preparations discussed under solutions and lotions and are either a wet or an astringent type of dressing used to treat inflammatory skin conditions, e.g. due to insect bites and plant secretions. Moist dressings impregnated with antiseptics, antibiotics, collagen or honey are used to enhance wound healing.

Zinc oxide

Zinc oxide has long been used in ‘zinc cream’ as a sunscreen; however, it has many more medicinal uses in dermatology, for its astringent, soothing and protective properties in powders, ointments and lotions. Zinc is a required co-factor in healing, and zinc creams and lotions are often effective in treatment of mild inflammatory conditions such as musculoskeletal pains, skin irritations and allergic reactions, and nappy-rash in babies.

Types of drugs affecting the skin

So many dermatological products are available, both OTC and by prescription, that it would be difficult to discuss them all in this chapter. For the sake of simplicity, we discuss only a few selected groups of dermatological products: sunscreens, topical antimicrobials and antiinflammatories, retinoids and other drugs used to treat acne and agents used specifically for burns and pressure ulcers. (The detailed pharmacology of most of these drugs has been discussed in previous chapters, e.g. under hormones, anti-inflammatories and antimicrobial agents.)

Other general dermatological products include the astringents, cleansers, liniments, antiseptics and keratolytics described earlier and products such as antiperspirants, antiseptics, antidandruff shampoos, bath oils and body washes, face washes for acne, freezing sprays for warts, skin lighteners and darkeners, filling agents for wrinkles and lips, medicated toothpastes, insect repellents, hair removers and hair restorers. (Strictly speaking, topical agents acting on mucous membranes could also be included, such as eye-drops and ointments, nasal drops and sprays, mouthwashes and even suppositories and enemas.)

Natural plant extracts and oils with some proven or claimed antiseptic properties include oils of melaleuca (tea-tree), lemon, lemongrass, eucalyptus, clover leaf, thyme, pine, citronella and peppermint flowers, and extract of aloe vera (see Clinical Interest Box 48-2). Honey is also used for its antiseptic properties (and of course for sweetening, see Clinical Interest Box 32-3), and pawpaw as an analgesic and antipruritic. Most of these products are available OTC in pharmacies and supermarkets.

Sunscreen preparations

Skin damage from the sun

Phototoxicity and photoallergy reactions

Phototoxicity

Certain chemicals and drugs (e.g. dyes, suntanning preparations, tetracyclines, oestrogens, sulfonamides, thiazides and phenothiazines), plants, cosmetics and soaps can cause a phototoxic reaction—an excessive response to solar radiation occurring in the presence of a photosensitising agent. Photosensitivity, or phototoxicity, occurs when the inducing agent is present in the skin in sufficient amounts and is exposed to a particular sunlight wavelength. The substance absorbs the radiation and energy is transferred, producing a reactive molecule or free radical, which is destructive to cell membranes or lysosomes. The exposed skin rapidly becomes red, painful, prickling or burning, with peak skin reaction reached within 24–48 hours of exposure. This reaction does not involve the immune system but resembles excessive sunburn.

Photoallergy

A photoallergy reaction is different from a phototoxic reaction; it is less common and requires prior exposure to a photosensitising agent, which is activated to an allergen or hapten by radiation. The immune system is involved and when the photosensitiser reacts with UVR a delayed hypersensitivity reaction occurs, presenting as severe pruritus and a rash that can spread to skin areas that were not exposed to sunlight.

Ultraviolet radiation damage

Extended exposure to the sun, whether from sunbathing or as a normal consequence of an outdoor occupation or lifestyle, can lead to sunburn, premature ageing of the skin (photoageing), immunosuppression and skin disorders including cancers. The damage is caused by solar ultraviolet radiation (UVR), which comprises the part of the spectrum of electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths shorter than those of visible light (at the violet end of the colour spectrum) and longer than those of X-rays.

Effects of UVR

UVR has useful effects in activating sterols to vitamin D compounds and has been used to treat acne and neonatal jaundice (and thus prevent kernicterus and permanent brain damage). UVR can also damage DNA strands by causing thymine bases to link in dimers, and may activate or inactivate viruses. Excessive exposure to UVR can result in skin damage that progresses from minor irritations, blistering, skin darkening (tanning) and thickening, through severe sunburn to a precancerous skin condition and skin cancer later in life. Cutaneous malignant melanoma has been associated with excessive sun exposure, especially during childhood, whereas large cumulative UVR doses over a lifetime appear to increase the incidence of non-melanoma skin cancers (see Clinical Interest Box 48-3). UVR has been shown to cause mutations in the tumour-suppressor gene p53. Actinic (solar) keratoses, lesions that are potential precursors of squamous cell carcinomas, are sometimes treated with topical cytotoxic drugs, the anti-proliferative agent imiquimod (also used against warts) or with diclofenac gel (an NSAID).

Clinical Interest Box 48-3 Sunburn, skin cancer and SPF

Incidence

Skin cancers mainly comprise malignant melanomas and nonmelanocytic cancers (basal [BCC] and squamous cell [SCC] carcinomas). The incidence of skin cancers in Australia is now more than three times the incidence of all other can cers combined. Two out of three people who live their lives in Australia will require treatment for at least one skin cancer, and about 1000 Australians die each year from skin cancer, mainly melanomas. Because of excessive sun exposure and the largely fair-skinned populations, Australia and New Zealand have by far the highest rates of both incidence and mortality of melanoma in the world.

Statistics on the incidence of non-melanocytic cancers are not easy to ascertain, as the cancers are very common and may be treated by general practitioners without numbers being notified to a central cancer registry. BCCs make up around 80% of skin cancers, SCCs 15%, and melanomas about 5%. BCC and SCC are almost twice as common in men as in women, as they are closely related to sun exposure. In the 15–24 age group in Australia, melanomas are the most common cancers. The annual incidence of melanomas in Australia in 2001 was about 55 per 100,000 for males and 37 per 100,000 for females.

Preventive measures

Sun protection is necessary, as sunlight is the major external cause of skin cancer. Childhood exposure to sunlight is important in development of all types of skin cancers, with episodic high exposure causing burning a significant factor in later melanomas. There is a 10–20-year delay between the UVR exposure (especially UVB) and the appearance of skin cancer.

The primary means of protection is avoiding sunburns, especially in childhood and adolescence. If possible, avoid outdoor activities when the sun is strongest (‘from 11 to 3, stay under a tree’), wear protective clothing (broad-brimmed hat and long sleeves) and stay in the shade. A broad-spectrum sunscreen that blocks exposure to UVA and UVB light (sun protection factor [SPF] 15 or 30) should be applied liberally and reapplied every 2 hours and after swimming, vigorous activity and towelling dry. UVR can also affect the eyes, increasing the risk for cataracts and other eye disorders, and it can suppress the immune system. It is recommended that sunglasses that block 99%–100% of UVR be worn, especially by people with light-coloured eyes.

Treatment measures

Choice of treatment is based on assessment of type of tumour, site, size and stage; age and condition of the patient; and facilities and skills of the physician. Surgical excision is most common for all skin cancers and the only treatment for melanomas. Non-melanocytic cancers, if inaccessible by surgery, may be treated with radiotherapy, curettage and cryotherapy. Topical treatment with retinoids, antibiotics, powerful keratolytics and cytotoxic agents is being trialled. Lifelong follow-up is required for all patients who have been treated for a skin cancer, as they are at greater than normal risk of recurrence and of developing another primary tumour. Actinic (solar) keratoses, which can potentially develop into squamous cell carcinomas, are sometimes treated topically with diclofenac 3% gel, fluorouracil or imiquimod 5% cream or methyl aminolevulinate 16% cream plus red light photosensitisation.

Sources: Anti-Cancer Council of Victoria 1999; AIHW 2008; Australian Medicines Handbook 2010.

Most age-associated changes in skin appearance are due to UV-induced effects via mitochondrial damage, protein oxidation, reduction in transforming growth factor and DNA damage. Clinical signs include dryness, irregular darkened pigmentation, deep furrows, leathery appearance and reduced elasticity of skin and amount of collagen.

UVR spectrum

UVA, or long-wave radiation, has wavelengths in the range 400–320 nm and is the closest to visible light; it can pass through glass and penetrate into the dermis. It produces darkening of preformed melanin in the basal layer of the epidermis, results in a light suntan and contributes to skin cancer via immunosuppression. UVA is responsible for many photosensitivity reactions. (This is the wavelength used in commercial solariums.)

UVB has wavelengths of 320–290 nm. It causes erythema, sunburn and photoageing and is associated with vitamin D3 synthesis. UVB is responsible for skin cancer induction, and the carcinogenic properties of UVB appear to be augmented by UVA. Around 90% of UVB has in the past been blocked by the Earth’s ozone layer, hence the worldwide concern that ‘holes’ in the ozone layer (caused mainly by environmental pollutants and ‘greenhouse gases’ such as chlorofluorocarbons) will allow passage of greater proportions of solar UVB and increase the incidence of skin cancers.

Most of the UVC from the sun (wavelength 290–200 nm) does not reach the earth’s surface. Exposure to this type of radiation is usually from artificial sources such as mercury lamps and arc-welding. UVC can cause some erythema but will not stimulate tanning; it is very damaging to the retina.

In this context, ‘broad spectrum’ refers to sunscreens that block both UVA and UVB. Very little UVR is blocked by cloud cover, although infrared radiation that contributes to the sensation of heat is usually reduced, which can give a person a false sense of security against sunburn. The sun’s rays can be reflected onto skin from water, concrete, snow and sand, but are deflected by the Earth’s atmosphere and by sweat; hence sunburn is worse at high altitudes and in dry desert conditions.

Sunscreens

Absorbers or reflectors

Sunscreen preparations are applied to absorb and/or to reflect UVR, in order to reduce the risks of photo-ageing, sunburn and skin cancers. It should be noted that sunscreens may be more effective at preventing sunburn than preventing skin cancers.

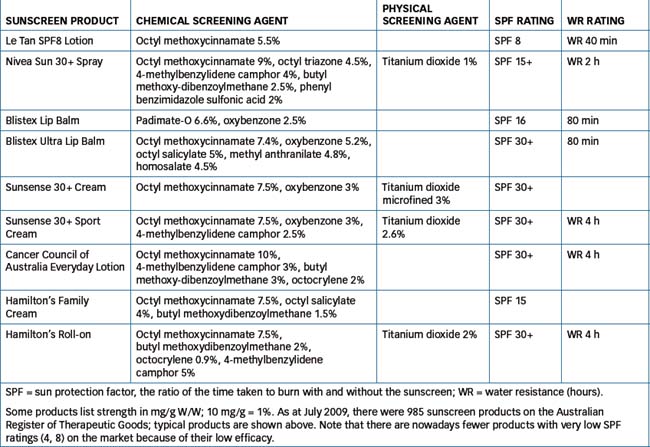

Absorbing chemicals absorb and block at least 85% of the UVB. Absorbing agents are chemicals such as p-aminobenzoic acid (PABA) derivatives, benzophenones (which absorb both UVA and UVB), cinnamates, some salicylates, camphors and anthranilates (see Table 48-2).

Physical or opaque sun blocks contain agents that reflect and scatter UVB and UVA but do not absorb it. Reflectors include chemicals such as titanium dioxide and zinc oxide. These agents are opaque (e.g. zinc creams, which look like thick white paste) and must be applied heavily to physically block out the UVR, thus they are not cosmetically acceptable to most people.

Nanoparticle sunscreens

Both types of agents are now also being prepared as nano-sized particles in sunscreens; these ‘micronised’ products are less opaquely white, but their long-term safety has yet to be established. At present, it appears that insoluble nanoparticles, such as titanium and zinc oxides, do not penetrate human skin and so are non-toxic (see Clinical Interest Box 42-4, and reviews by Nohynek et al [2008], Baron et al., 2008Baron et al [2008] and Lautenschlager et al [2007]). Consequently, the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) does not require that warnings about nanoparticles be placed on labels of such products. The TGA will continue to monitor the scientific literature with respect to safety concerns about nanoparticle products.

Sun protection factors

The sun protection factor (SPF) is a value given to a sunscreen preparation to indicate its effectiveness. It is largely determined by the sunscreening agents (whether chemical or physical) present in the preparation. The SPF for a product is the ratio between the exposures to UVB required to cause erythema (reddening) with and without the sunscreen. This is expressed as the MED, or the minimal erythemal dose: if a person experiences 1 MED with 25 units of UVR (in an unprotected state) and if after application of a sunscreen the person requires 250 units of radiation to produce the same amount of reddening, then this product will be given an SPF rating of 10. The higher the SPF, the longer it takes to burn or develop a tan. However, ‘SPF numbers should not be translated into burn times for individuals’ (Dermatology Expert Group 2009).

The SPF scale is a logarithmic scale rather than an arithmetic one, thus a sunscreen with SPF 2 gives a 50% reduction in UVB passage (50% penetration), SPF 4 gives 75% reduction (25% penetration) etc. Hence it can be calculated that SPF 16 (i.e. 15+) reduces UVB passage by about 94% of UVB, whereas a screen with SPF 32 (30+) reduces it by 97%. Thus, although they sound much more effective, there is little useful difference between preparations with very high SPF values. A more important consideration is the water-resistance time of the product, because this period may be much shorter than the ‘SPFallowed’ time.

Choice of SPF

The best way to choose a sunscreen is according to skin type, the length of time spent in the sun, whether water resistance is important, the usual intensity of the sun’s rays in the geographic area and the type of preparation or formulation preferred. People who tan gradually and don’t burn easily may use an SPF 15+ preparation, while those who burn easily and tan only minimally need a 30+ formulation. An SPF 30+ sunscreen is recommended for use by all fair-skinned people in tropical areas.

Water resistance of sunscreens

The efficacy of a sunscreen agent depends on its ability to remain effective during vigorous exercise, sweating and swimming. Two categories established are ‘water-resistant’ and ‘very water-resistant’ (waterproof). Water-resistant products maintain sun protection for at least 40 minutes in water; very water-resistant products maintain sun protection for at least 80 minutes in water. Water resistance is largely dependent on the vehicle used in the product, in particular how water-soluble it is; thus oil-based lotions and creams are likely to remain on the skin longer while swimming than are O/W creams or lotions.

Application of sunscreens

Sunscreens should be liberally applied to all exposed body areas (except eyelids) and reapplied frequently to achieve the maximum effectiveness. It has been recommended that sun block be applied 30 minutes before exposure to allow adequate skin penetration, and reapplied every 2 hours depending on factors such as the product used (the SPF and water resistance category), activity and sweating levels, time of day, cloud cover and reflections. It is recommended that individuals stay out of the sun when the UVR is at the highest intensity, usually between 11 am and 3 pm, when two-thirds of the daily solar radiation occurs.

Logically, it can be seen that reapplication does not ‘allow’ another number of hours of sun—if a person has already had enough UVR to reach the MED, then any further exposure will cause more erythema, i.e. burning. Because the amount of sunscreen applied is often only one-third to half of what is necessary, the theoretical SPF is rarely achieved, which explains why people get sunburnt despite applying sunscreen. Generally, Australians do not use enough sunscreen—a family of four on a beach holiday should use a bottle of sunscreen every couple of days, but many families make a bottle last a year! Sunscreens are dated products and may lose efficacy if kept after their use-by date.

Infants should be kept out of the sun; children older than 6 months should always wear protective clothing, hats and sunscreens, with SPF 15 to SPF 30. It has been projected that consistent use of SPF 15 products from 6 months through to 18 years of age will result in about 80% reduction in the risk of skin cancer over a person’s lifetime.

Sunscreens and low vitamin D

There has been an increasing incidence of vitamin D deficiency in Australia in the last few years, causing rickets or osteomalacia (see Chapter 37). This has been explained partly by immigration of dark-skinned people who may wear long covering clothing and veils (preventing sun activation of vitamin D in the skin) and partly by increasing protection of skin from the sun by use of shade, hats and sunscreens. The prevalence is also high in institutionalised elderly people. The Dermatology Expert Group (2009) suggests that ‘fair-skinned Australians should be able to maintain adequate vitamin D concentrations with 10 minutes of sun exposure to the face, arms and hands on most days of the week during summer, and for 2–3 hours per week over winter ... Patients who receive little sunlight should be investigated for vitamin D deficiency and when present, supplemental vitamin D should be offered’.

Topical antimicrobial agents

General principles of antimicrobial chemotherapy of skin infections

Antimicrobial agents used on the skin or to treat skin infections include antibacterial, antiviral, antifungal and antiparasitic agents. There is an increasing problem worldwide with organisms developing resistance to antimicrobials, hence concerted efforts are being made to rationalise the prescribing of broad-spectrum antibiotics and use drugs specific to organisms that are sensitive to them.

Antimicrobials used topically are preferably not the same as those used systemically, both to minimise the risk of development of resistance and to utilise drugs that may be toxic systemically but not topically. Whenever possible, skin or nail infections are treated with topical antimicrobials; however, in some severe infections, e.g. fungal nail infections or acne resistant to topical treatment, systemic chemotherapy may be required with antimicrobial agents administered orally.

All the antimicrobial drug groups (except those used to treat parasitic infestations) have been covered in detail in earlier chapters (44–46), so only summaries will be given here.

Antiseptics

Many topical preparations are available OTC, labelled as first-aid products to help prevent infection in minor cuts, burns or injuries. These generally contain simple antiseptic or disinfectant-type products and are effective for first-aid treatment but not for specific bacterial infections. Antiseptics (skin disinfectants) are solutions or creams of antimicrobial agents applied topically to the skin; they usually contain chemicals that are very effective but too toxic to be administered internally. Many have simple detergent, solubilising actions. Examples include benza lkonium chloride, triclosan, chlorhexidine, cetrimide, povidone–iodine and hypochlorite solutions (see Appendix 2). Plant products such as aloes, benzoin and oils of melaleuca, lemon, clove, thyme and lemongrass have mild antiseptic properties.

Antibacterial agents

The most frequent organisms causing skin infections are the common body flora bacteria Streptococcus pyogenes and Staphylococcus aureus, causing folliculitis, impetigo, furuncles (boils), carbuncles (multi-headed boils of several adjacent hair follicles) and cellulitis. To treat these common skin disorders, topical antibacterials including bacitracin, neomycin, sodium fusidate, polymyxin B, silver sulfadiazine, framycetin, gramicidin, mupirocin and metronidazole may be applied. Clindamycin and erythromycin are used in acne and silver sulfadiazine in burns (see later sections). Antimicrobial agents are sometimes formulated in combination with a corticosteroid, for treatment of inflammatory conditions in which there is a major component of infection as well.

Common adverse effects

Sensitisation to many topical antibiotics can occur. Prolonged use can produce superinfection as an overgrowth of non-susceptible organisms such as fungi. Photosensitivity is reported with topical gentamicin. Chloramphenicol used topically can cause systemic adverse effects, including bone marrow hypoplasia and blood dyscrasias, as well as local effects such as itching, burning, urticaria and vesicular and maculopapular dermatitis. Topical fusidic acid is likely to induce resistance.

Antibiotics only used topically

Neomycin

Neomycin is a broad-spectrum aminoglycoside antibiotic, indicated for topical application in infections such as impetigo (‘school sores’) and boils. It is also used in an anti-acne lotion and in preparations for application to eye or ear infections. Overgrowth of resistant organisms can occur with prolonged use.

Applied topically, neomycin occasionally irritates the skin, and allergic contact dermatitis has been reported. For conditions where percutaneous absorption of neomycin can occur (including burns and trophic ulceration), there is the potential for nephrotoxicity, ototoxicity and neomycin hypersensitivity reactions. Use in pregnancy can lead to ototoxicity and renal toxicity in the fetus (Pregnancy Safety Category D).

An ointment that combines neomycin, bacitracin and polymyxin B (‘triple antibiotic’) may be more efficacious in mixed infections (e.g. in the ear) than when these agents are used singly; see Drug Monograph 32-1.

Mupirocin

Mupirocin is a topical antibiotic obtained from Pseudomonas species; it inhibits RNA and protein synthesis and is active mainly against Gram-positive aerobes. It is used in treatment of impetigo caused by S. aureus and beta-haemolytic streptococci and in eradicating the nasal carrier status for S. aureus. It is usually applied to affected areas three times daily.

Antiviral agents

Aciclovir and idoxuridine

Aciclovir and idoxuridine are used for treatment of cutaneous herpes simplex infections of the lips (‘cold sores’) or genital areas. Aciclovir is activated in herpesinfected cells to a metabolite that inhibits viral DNA polymerase, thus inhibiting further viral replication. Topical aciclovir is used for the treatment of herpes simplex (non-life-threatening) in immunocompromised patients; however, systemic aciclovir is much more effective. Another guanine analogue, penciclovir, is also formulated in a lip cream for labial herpes simplex.

Idoxuridine is an antimetabolite with a mechanism of action similar to those of the antitumour antimetabolites: its structure is very similar to that of the nucleic acid base thymidine, and it inhibits the incorporation of thymidine into viral DNA and hence blocks viral replication, analogous to the antimetabolites used in cancer chemotherapy (see Figure 42-1). It is available combined with lignocaine in a cream for use in herpes simplex infections (e.g. ‘cold sores’ on the lips).

Adverse reactions from topical application of aciclovir or idoxuridine include hypersensitivity reactions, pruritus and stinging. The dosage is enough for adequate covering of the lesions with ointment, from as early as possible in the infection, every 4 hours daily for 5 days.

Treatment of warts

Although warts are caused by a virus (human papillo mavirus, HPV), they are not treated with specific antiviral drugs. Warts usually resolve without treatment, as they are overcome by the body’s immune defences. In immunocompromised patients, however, they can become extensive. Anogenital warts are predominantly transmitted in young people by sexual intercourse. The condition can undergo malignant transformation, and in women there is a strong association with cervical cancer; there is now an effective vaccine against HPV.

Treatment for warts depends largely on the site involved and extent of spread. Topical application of keratolytics, such as salicylic acid and trichloroacetic acid, and topical antimicrobials, including podophyllotoxin and glutaraldehyde, have been used. Non-pharmacological treatments include curettage, electrosurgery and cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen or solid carbon dioxide.

A new drug, imiquimod, is used for treating external genital and perianal warts; it acts via agonist activity at toll-like receptor-7 to enhance the body’s immune response. (It has also been approved for use by topical application in treatment of solar keratoses and some non-melanocytic skin cancers such as superficial basal cell carcinomas when surgical removal is not appropriate.) For anogenital warts a 5% cream is applied topically at night 3 nights per week for a maximum of 16 weeks; severe inflammatory responses are possible.

Antifungal agents

Fungal skin infections

Three pathogenic fungi (dermatophytes) that can cause superficial fungal infections (dermatophytoses) without systemic infection are Microsporum, Trichophyton and Epidermophyton; there can also be mixed infections. Systemic mycoses usually occur only in severely immunocompromised patients.

Dermatophytes exist in moist, warm environments, such as skin areas covered by shoes and socks (tinea pedis, or athlete’s foot), or in the groin, scalp or trunk. The fungi invade the stratum corneum and cause inflammation and induce sensitivity when they penetrate the epidermis and dermis.

Because the stratum corneum is shed daily, spread of the fungi occurs by contact, commonly around swimming pools or in bathrooms. General hygiene measures such as wearing sandals in communal change-rooms and showers and drying skin well, especially between the toes, help reduce infection. Before starting treatment, skin or nail scrapings should be taken for microscopic identification of the causative organism. Treatment may be required for many months, and relapse after cessation is common.

Foot infections are particularly dangerous in people with diabetes, and fungal infections can lead to bacterial infections, gangrene and amputations (see Chapter 36). Onychomycosis (fungal infection of toenails) is a significant predictor of foot ulcers, so early intervention and good foot care are critical.

Antifungals

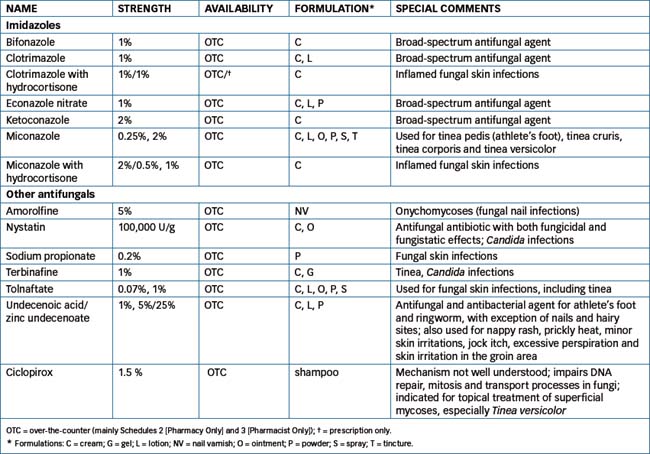

The primary topical antifungal agents include the imidazole group (clotrimazole, ketoconazole, bifonazole, miconazole etc), terbinafine and amorolfine, and miscellaneous antifungal agents, including undecylenic, benzoic, salicylic and propionic acid products, tolnaftate, the antibiotics nystatin and griseofulvin, povidone–iodine, a new antifungal ciclopirox and a variety of antifungal combination creams, ointments, powders, sprays, liquids and paints (see Chapter 45).

Fungal infections of the nails (onychomycoses) are particularly resistant to treatment by usual topical or oral formulations, so a medicated nail varnish has been developed (Drug Monograph 48-1). See Table 48-3 for the generic names, availability status (OTC or prescription) and comments on topical antifungal products. Adverse reactions with the use of the topical antifungals are generally mild and include local irritation, pruritus, erythema and stinging.

Drug Monograph 48-1 Amorolfine nail lacquer

Amorolfine is one of a pair of antifungal agents (the other is terbinafine) that have selective fungistatic and fungicidal actions against a broad spectrum of yeasts, dermatophytes and other fungi and moulds. They impair sterol synthesis in fungal cell membranes and are active both orally and topically. Amorolfine is the only antifungal agent that is sufficiently well absorbed through fingernails and toenails to be effective topically in treating fungal nail infections (onychomycoses); however, it is expensive and may have limited efficacy.

Indications

Amorolfine nail varnish is indicated for topical treatment of onychomycoses; it alleviates or cures 70%–80% of cases.

Pharmacokinetics

Amorolfine is very lipophilic but is virtually insoluble in intestinal fluids. After application to the nail, it permeates and diffuses through the nail plate and can reach measurable levels in the blood.

Adverse reactions

Because fungal sterols are different from those in mammalian cells, there are few adverse effects. Occasionally a slight burning sensation is felt after application; allergic reactions are rare.

Drug interactions

There are no known drug interactions; however, patients are advised not to use any other nail preparations (polishes, artificial nails) during treatment. If the fungal infection is too severe to be treated by amorolfine nail varnish as monotherapy, PO antifungals such as griseofulvin may be required concurrently.

Warnings and contraindications

Amorolfine is contraindicated if a previous hypersensitivity to it has occurred. Users are warned not to apply the varnish to the skin beside the nails. There is little information on the use of this product in pregnant or lactating women or in children, so its use in these people is not recommended.

Dosage and administration

Amorolfine is supplied as a 5% solution in a 5 mL nail lacquer base; also included in the kit are cleaning pads, nail files and spatulas to be used in applying the varnish. The varnish is applied 1–2 times weekly after first cleaning the nail and filing it down (including the nail surface) to remove as much as possible of the infected nail. Before the next application, the nail is cleaned to remove the remaining varnish and filed down again. Because nail infections are so difficult to eradicate, the process needs to be continued for about 6 months for fingernails and longer for toenails.

Ectoparasiticidal drugs

Ectoparasites are insects that live on the outer surface of the body; ectoparasiticides are drugs used against those parasites; they are referred to as pediculicides (against lice) and scabicides or acaricides (against mites), reflecting the type of parasite treated.

Treatment of pediculosis (lice infestation)

Pediculosis is a parasite infestation of lice on the skin of a human. Lice are transmitted from one person to the next by close contact with infested people, clothing, combs and towels. There are three types of infestations: (1) pediculosis pubis, caused by Phthirus pubis (pubic or crab louse); (2) pediculosis corporis, caused by Pediculus humanus corporis (body louse); and (3) pediculosis capitis, caused by Pediculus humanus capitis (head louse). In pediculosis corporis, except in heavily infested individuals, the parasite is often absent from the body but inhabits seams of clothing in the axillae, beltline or collar.

Common findings in a person who is infested include pruritus (itching), nits (eggs of lice) on hair shafts, lice on skin or clothes and, occasionally with pubic lice, blue macules on the inner thighs or lower abdomen. The drugs of choice are the pediculicides permethrin and maldison (malathion) in lotions or shampoos; local public health officers or school nurses usually recommend the optimal current treatment regimen, including use of medicated shampoo and combing of hair with a fine-tooth comb to remove nits. Affected family members may also require treatment, and hairbrushes, hats, clothing, bedding etc require cleaning.

Pediculicides

Permethrin acts on the nerve cell membranes of lice, ticks, mites and fleas. It disrupts the sodium channel depolarisation, thus paralysing the parasites. It has a high cure rate (up to 99%) in treating head lice after only a single application. The most common adverse reactions include pruritus, mild burning on application and transient erythema. Related compounds are the allethrins and the natural pyrethrins found in chrysanthemum flowers.

Maldison (also known as malathion) is an organophosphate cholinesterase inhibitor available for treating head lice and nits; it is relatively non-toxic to humans. This product is usually effective in lice-infested individuals within 24 hours and is well tolerated. Malathion lotion is rubbed into the scalp and left to air-dry. Because the drug is flammable, the individual must be warned to avoid open flames and smoking and not to use a hairdryer. The hair should be shampooed 8–12 hours after application; dead lice and nits are combed out.

Benzyl benzoate is an older type of pediculicide, also effective as an acaricide against mites. It is sometimes used as an insect repellent, and clothes or mosquito nets can be soaked in a solution and dried; the repellent effect outlasts some washings. Permethrin is used in a similar manner to impregnate clothing and nets with repellent.

Treatment of scabies (mite infestation)

Scabies is a parasitic infestation caused by the itch mite Sarcoptes scabiei. It is an obligate parasite of humans and is transmitted by close contact with an infested individual. It bores into the horny layers of the skin in cracks and folds (almost exclusively at night), causing irritation and pruritus. The infestation in adults is usually generalised over the body, especially in web spaces between fingers, wrists, elbows and buttocks.

The acaricide of choice is permethrin cream or lotion, two applications 1 week apart. This is considered more effective than crotamiton or benzyl benzoate. Family members and close contacts should also be treated, and items such as bedding, clothes and soft toys should be sprayed.

Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulating agents

As many conditions manifested in the skin involve inflammatory or autoimmune pathological processes, drugs that modify these responses are widely used in derm atology to target mediators such as cytokines, receptors and inflammatory cells. Most commonly used topically are the corticosteroids; other immunosuppressants include drugs such as cyclosporin and methotrexate, and newer ‘immunobiological agents’ such as pimecrolimus, infliximab and etanercept (see Chapter 47). For optimal efficacy the drugs should penetrate into the deeper layers of the skin, but not be absorbed into the systemic circulation (to avoid systemic adverse effects) (see review by Pariser [2009]). In severe cases of inflammatory or autoimmune dermatological conditions, the drugs may need to be administered systemically.

Corticosteroids

Actions and uses

Topical corticosteroids are generally indicated for direct relief of inflammatory and pruritic dermatoses, with fewer systemic effects than from oral or parenteral administration; these drugs are discussed in greater detail in Chapters 35 and 47 (see Drug Monograph 35-1). They are used topically for their anti-inflammatory, antipruritic, vasoconstrictor and immunosuppressant actions in various types of dermatitis (eczema) and psoriasis, and in skin reactions to insect bites and sunburn. Topical corticosteroids may also stabilise epidermal lysosomes in the skin, and fluorinated steroids have antiproliferative (antimitotic) actions.

Adverse drug reactions

Adverse reactions for topical corticosteroids include skin atrophy and striae, acneiform eruptions, burning sensations, dryness, itching, hypopigmentation, purpura and haemorrhage, hirsutism (usually facial), folliculitis, alopecia (usually of scalp) and masking or aggravation of fungal infections. Contact dermatitis can be precipitated as an allergic reaction to topical corticosteroids, which may be difficult to distinguish from the inflammatory condition for which the drug is being applied.

If a significant amount of the corticosteroid is absorbed, systemic adverse effects can occur, with suppression of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and the classical cushingoid effects of moon face, fluid retention, skin striae, weak skin and bones, hypertension, immunosuppression, overgrowth of microorganisms leading to secondary infections, glaucoma and poor wound healing.

Potencies

Fluorinated corticosteroids are particularly recommended for topical application to thickened skin because of their potency, lipid solubility (hence topical efficacy) and low tendency to cause sodium retention. In decreasing order of potency, some topical corticosteroids are: betamethasone dipropionatef> betamethasone valeratef, mometasone, triamcinolonef> clobetasonef, flumethasonef, methylprednisolone > desonidef, hydrocortisone. (Those marked f are fluorinated compounds; potencies can vary depending on ester form and strength of formulation.)

Acute inflammatory eruptions usually respond to the medium- and low-potency steroids, whereas chronic hyperkeratotic lesions require potent or highly potent drugs.

Formulations

Corticosteroids are available in a wide range of topical formulations that are stable, easy to apply and rapid-acting, causing no pain, discolouration or odour on application. Inhalation of corticosteroids (see Drug Monograph 28-4) in treatment and prevention of asthma is a specialised topical application, in this case to the mucous membranes and thence to the smooth muscle of the airways.

Types of formulations for topical application of corticosteroids include creams, ointments, lotions, sprays, gels and scalp lotions, at various strengths. Combination preparations with antifungal or antibacterial antibiotics are also available for use in inflammatory dermatitis with a large component of infection.

The vehicle (aerosol, cream, gel, lotion, ointment, solution or tape) in which the corticosteroid is placed can alter the therapeutic efficacy. Corticosteroid penetration of the skin is enhanced by (in decreasing order of effectiveness) ointments, gels, creams and lotions. As a result of their occlusive nature, ointments hydrate the stratum corneum, enhancing steroid penetration. Lotions, sprays and gels are well suited to hairy areas or for lesions that are oozing and wet. Creams and ointments are suited to dry, scaling, thickened and pruritic areas.

The rate of transcutaneous penetration after application also influences therapeutic efficacy. It is limited by three factors: the rate of dissolution of the drug in the vehicle, the rate of passive diffusion of the drug across membranes and the drug penetration rate through the stratum corneum. Inflamed or moist skin absorbs topical steroids to a greater degree than thick or lichenified skin. Occlusive dressings (e.g. using an occlusive ointment base or wrapping in plastic cling-wrap, see Figure 48-3) increase the hydration of the skin and penetration of the drug up to 100-fold, hence systemic adverse effects are possible.

Dosage and administration

For most topical formulations, the adult dosage is one or two applications daily as directed. Application frequency depends on the site, response of the cutaneous eruption to medication and application technique.

In some conditions resistant to milder treatment, intralesional injection of corticosteroids is used. Triamcinolone is most often used, injected for example into the lesions of keloid scars, acne cysts or alopecia areata.

Newer immunomodulators

Calcineurin inhibitors

Pimecrolimus is a new calcineurin inhibitor related to tacrolimus and sirolimus, which are used mainly to prevent transplant rejection, and temsirolimus, an mTOR inhibitor used as an anti-angiogenesis agent in renal cell cancer therapy. These agents block T-cell activation and thus prevent release of inflammatory mediators. Pimecrolimus is indicated for short-term or intermittent use in treatment of psoriasis and eczema, applied twice daily as a cream. It can be used safely in children over 3 months, which is a benefit in childhood dermatoses. Main adverse reactions are local stinging and erythema and secondary infections.

TNF-alpha antagonists

Tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) is an important regulator of inflammation, and antagonists of its activity are some of the newer anti-inflammatory agents proving effective in treatment of psoriasis. Etanercept is a TNF-α receptor fusion protein, while adalimumab, infliximab and golimumab are monoclonal antibodies against TNF. They are given by injection, and reactions at the infusion or injection site are common. Serious adverse effects include opportunistic infections and reactivation of infections (especially tuberculosis). There may also be increased risk of multiple sclerosis and of malignancies.

Uses in eczema, psoriasis and urticaria

Eczema

Eczema, also known as dermatitis, is an inflammatory condition with genetic predisposition in which skin becomes red, itchy, scaly, moist and blistered. Emollient moisturisers are indicated to maintain skin hydration, tar preparations (coal tar, ichthammol) are used for their antipruritic effects and topical corticosteroids for antiinflammatory effects. The potent new immunosuppressant pimecrolimus is second-line therapy. Antibiotics may be required for infected patches of skin, and antihistamines, sedatives or analgesics for relief from itching. UVR therapy and avoidance of triggering factors such as soaps, perfumes and preservatives are also useful. Strategies with no proven benefit include homoeopathy, Chinese herbs, dietary restrictions, massage therapy, reduction of house dust and salt baths.

Atopic dermatitis is common in young children, with prevalence of 10%–20% in those under 10 years; itching and infections are likely. Prevention is best, with education of parents and avoidance of triggers and irritants such as harsh, perfumed or coloured bath additives. Topical corticosteroids are used short-term for flare-ups, and calcineurin inhibitors (e.g. pimecrolimus cream) can be administered to children over 2 years old with severe disease.

Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a common skin disease (with 2%–3% prevalence worldwide) characterised by abnormal immune response, epidermal proliferation and pink–red thickened patches of skin covered with silvery scales, with pain, itching and bleeding. Large areas of skin may be involved, with the elbows, knees, buttocks and scalp most frequently affected. There are various forms, mostly of the plaque variety; the abnormally thick lesions are packed with activated T cells causing chronic inflammation and impairing skin functions. There is a strong association with arthritis, liver disease, cardiovascular diseases and metabolic syndrome. Peak onset is in early adult years. The cause is unknown, although there appears to be an immunological involvement, and trigger factors include stress, injury, smoking, alcohol, infections and drugs such as some angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, β-blockers, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), quinine derivatives and lithium.

Drugs used in treatment include those administered for eczema (see above), plus the psoralens, vitamin D analogues (calcipotriol, calcitriol, which act as antiproliferative agents in the keratinocytes, see Chapter 37) and a retinoid (acitretin). In severe cases, systemic administration of the immunosuppressants cyclosporin and methotrexate (in considerably lower dose than that used in anticancer chemotherapy) may be required, with phototherapy. The new immunomodulators are also tried, especially the anti-TNF agents etanercept, infliximab and adalimumab and the new anti-interleukin antibody, ustekinumab. Adverse effects include infections, malignancies and induction of autoimmune conditions. Interestingly, some TNF inhibitors when used to treat autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn’s disease have actually induced psoriasis, a condition which they can be used to treat—this anomaly is being studied further. Tazarotene cream, a retinoid used in acne for its actions modifying cell proliferation and differentiation, is also indicated for use in plaque psoriasis.