Chapter 12 Loss and bereavement

Introduction

The death of a significant person is the most difficult loss most people will face and nurses have an important role to play in supporting people who are dying and their families. The first part of this chapter explores issues of loss and bereavement, including death, and the impact of different types of loss on people. Consideration is given to bereavement, including understanding grief responses and planning care.

The middle section focuses on the palliative care approach to care, which encompasses care of people with life-limiting conditions such as cancer, chronic heart disease and some degenerative neurological illnesses. Caring for people at the end of life is a challenging part of the nursing role. Several members of the multidisciplinary team (MDT) are likely to be involved in the care and support of patients/clients with advanced disease and their families. However, nurses are generally the health professionals who have most contact. Nurses therefore have a significant role in supporting individuals through illness, at the end stages of life and families who are bereaved. The skills and knowledge of nurses caring for those with advanced, non-curable illness are crucial to the delivery of high quality care. Strategies for communication and the management of distressing symptoms are discussed. Helping nurses to understand the philosophy of the palliative care approach and the services available is the focus of this section.

The last section is about the care of people facing death – both the person who will die and those who are close to them. A framework for providing care around death is suggested. Finally, ethical concerns at the end of life are identified and the role of the nurse in the last act of care and in the provision of palliative care is identified.

Loss including death

This section considers factors relating to loss and bereavement. Death of a significant other is recognized as a difficult loss to cope with. Nurses are important in helping people to deal with losses which result from injury, illness and death. Therefore it is important to consider how experiences of loss – expected, planned or unexpected – throughout life prepare individuals to cope with significant losses.

Types of loss

Loss and change are part of everyday life and everyone will experience both of these during their lifetime. Loss is experienced in the absence of a person, miscarriage/stillbirth, own impending death, an object, body part, a function (e.g. walking), change related to age/milestones, loss of status, loss/change of job/retirement, a move into a care home, or from institutional to community care, or emotion, which was formerly present. There are several types of loss, the most traumatic of which include:

These losses may be thought of as rather less traumatic than that of a significant person. However, responses to loss are individual and linked to a range of other personality and lifestyle factors (Box 12.1). For example, non-animal lovers may find it hard to understand why a person is devastated at the loss of a much-loved pet. As a person’s pet may have been their constant companion, the loss is significant and its impact should never be underestimated.

Reactions to loss

Identify an object you have recently lost, e.g. keys, handbag, or breakage of a favourite item, etc.

Student activities

It is likely that many of the feelings you experienced are similar to those associated with loss through bereavement (see this page and p. 301). Therefore, even apparently trivial loss can result in a range of distressing feelings. It is important that nurses do not assume how people feel about loss, as insignificant loss to one person may be catastrophic to another.

Loss is an inherent part of any change, even where people have decided to make changes such as getting married or having a child. The losses associated with significant life events are expected and normally occur as the person matures from one stage of life to another and makes decisions about how they want life to develop (see Chs 8, 11). If progress through life’s normal milestones is not achieved, then feelings of loss may result. For example, parents whose children do not achieve normal life milestones due to disabilities or illness often find it hard to cope. Similarly, if a couple find they cannot have children, apart from dealing with their own feelings, they may feel pressurized by others who expect them to have children. Therefore, response to loss is shaped by context and culture.

Throughout life people form attachments and the stronger the attachment, the greater the loss experienced when that attachment is broken. When an attachment is broken, people cope by revising and reconstructing their life, thereby adapting to loss and subsequent change, often with support from family and friends. Professional intervention may be required if an individual cannot cope with significant loss such as a major change in body image or death. For most people, loss associated with life events they have not ‘chosen’ is the most difficult to cope with.

Bereavement

In most healthcare settings, nurses will encounter patients/clients and/or carers who are experiencingloss or have suffered bereavement (the loss of somebody or something of value, especially through death). It is often the nurse who assumes the role of helping the patient/client or carer. Bereaved individuals need open acknowledgement of the death and opportunities to display expressions of grief and mourning in order to help them come to terms with the loss. To do this effectively the nurse requires knowledge of what loss is and how people react to and cope with loss. There is also considerable evidence to suggest that professionals working with people who are dying find this enormously stressful (Smith 1992, Phillips 1996, Lockhart-Wood 2001). This type of stress has been referred to as the ‘emotional labour’ of nursing (James 1989). Through understanding the theories relating to the process of dying and grieving, the nurse is better equipped to support patients and carers in their journey.

For the purpose of this chapter the following definitions (Stroebe et al 2002) will guide understanding:

Models that describe dying and bereavement demonstrate that these processes usually involve a series of stages and that individuals take varying lengths of time in each stage and may move from one to the other and back again. Thus it is important to remember that each individual‘s reaction to loss is unique and there is no right or wrong way to grieve.

To date, Elisabeth Kubler-Ross’ (1969) ‘preparing to die’ model of dying has been the most influential. This seminal work was one of the first attempts to explain the process of dying in relation to the emotional and psychological adaptations which accompany the process. This theory made the previously taboo subject of death and dying one that could be openly discussed. For the first time healthcare professionals were able to relate to a theoretical model which made sense of their patients’ behaviours and actions.

The five stages of this model are:

Denial

This suggests that when given the knowledge that they have an incurable disease the patient will go into denial by refusing to believe that it is true. Denial is now recognized as a protective stage that allows for psychological adjustment to the news. This contradicts the earlier belief that people should be helped out of denial and made to face up to reality. Emerging theory suggests that forcing a person out of denial when they are not ready may be psychologically damaging.

Anger

Families and the patient when coming to terms with a diagnosis of serious illness often feel anger. Anger is often directed towards healthcare staff, especially doctors involved in the diagnosis. It may be perceived that the symptoms were missed or diagnosis took longer and therefore the illness progressed beyond a cure in that time.

Bargaining

Patients and families may seek to ‘make deals’; often this is done in private through prayer. It is an attempt to postpone the reality of loss and its presentation may be similar to denial.

Depression

This occurs when the reality of loss is felt and can no longer be denied. It is often accompanied with overwhelming sadness, feelings of loneliness and withdrawal from social activities.

Acceptance

The person has come to terms with the reality of their life now being limited. This is the final and desirable stage of this model. However, it is criticized, as acceptance may not always be achieved and there is a danger of healthcare professionals and other carers trying to push the person through the stages in order to reach this desired state.

[From Kubler-Ross (1969)]

Anticipatory grief

While Kubler-Ross’ model focuses on dying, it has close similarities with the concept of anticipatory grief. Anticipatory grief is grief occurring before death. It differs from post-death grief in its nature and course. Lindemann (1944) was the first to recognize this phenomenon and identified five characteristics of anticipatory grief:

Kubler-Ross noted that common behaviours include denial, reassurance seeking, secrecy about the diagnosis, anger and guilt. There are conflicting views of how helpful anticipatory grief is to the bereavement process, with some authors suggesting that it makes little difference. However, the predominant view is that it is helpful as it helps people to cope and reduces the length of time someone has to adjust to the news of impending death of a loved one. Parkes and Weiss (1983) found that those who have more than 2 weeks to adjust to loss had less difficulty in their adjustment than those who had less than 2 weeks. An alternative argument, however, could be that sudden deaths are more traumatic for the person and invoke a much stronger grief reaction.

One problem, however, is when the dying person appears to live longer than expected; the psychological preparation that goes with anticipatory grief and the state of ‘readiness’ may be achieved prior to the actual death.

Grief and mourning

Grief and mourning are terms used to describe the emotional reaction to loss or death and the expression of the emotion in relation to this event. Several theories have been proposed to aid understanding of the grieving pro-cess. Of these, Worden (1991) and Parkes (1998) are two of the most influential. These two theories complement each other (see Box 12.3, p. 302): Parkes’ theory describes the feelings and emotions the person affected by the loss is experiencing during different stages; Worden‘s theory illuminates the process of adjustment that is necessary to regain equilibrium.

Understanding the grief process

Reflect upon the theories of grieving and their relevance to clinical practice in your branch. You may wish to consider a patient/client and their family you have cared for. Although it is difficult to neatly package the actual experience into stages, you may have recognized some of the characteristics that would indicate the stage of grief.

Parkes (1998) describes four components of grief:

Parkes suggests that the components of grief must be worked through to enable the individual to ‘let go’ of the person they have lost and to be able to move on with their lives. He likens this process to the loss reaction and period of adjustment that people display when they have become disabled through the loss of a body part.

While each of these components is seen to be of equal significance, it is important to remember that people often do not clearly signal when one component is complete and they have moved into the next component. Indeed the boundaries are often blurred and people may oscillate between components before moving on. Parkes stresses the importance of allowing people to express their emotions and states that repression of grief is harmful and may result in delayed reactions and complicated grieving. Equally, obsessive grieving is harmful and may lead to chronic grief and depression.

Parkes’ theory describes the feelings relating to different stages of the grieving process. This is complemented by Worden’s theory of ‘grief work’ which focuses on the tasks that need to be completed to achieve resolution of these feelings. People sometimes talk about someone who has been recently bereaved as being in a ‘state of mourning’; however, Worden (1991) suggests that mourning is an active process which has to be ‘worked’ at. In his seminal work, Worden (1991) asserts that there are four ‘tasks’ of mourning that must be worked through in order for the person affected by the loss to be able to come to terms with their loss. They are:

Factors affecting grief

Many factors influence how people respond to loss and bereavement. Whether the death was expected or sudden has an impact on the bereavement process (see pp. 310–311). However, age, cognitive impairment (e.g. dementia or learning disabilities) and cultural differences are all factors that may influence the process of grieving.

Bereavement in children

Bereaved adults caring for a child are often left to support the child. Many are ill equipped to do so and this often results in a protective instinct to shield the child from the pain of the loss. However, with some support, even very young children are able to grasp the concept of death. Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that children who have suffered bereavement and not been able to express their grief are more susceptible to depression (Weller et al 1991). Thus helping and supporting the child to grieve is important.

In order to help children accept and come to terms with death there are a number of interventions that can be carried out to aid this process (Box 12.4). These include:

Bereavement in children and young people

Sue is dying and she and her partner have talked about how they can best prepare their children (Colin aged 15 and Kate aged 9) for Sue’s death and life without their mother.

Student activities

[Resource: Winston’s Wish – www.winstonswish.org.uk Available July 2006]

Bereavement in people with learning disabilities

It is widely accepted that the pattern of bereavement in people with learning disabilities is the same as everyone else, as is the case with people who have dementia. However, in some cases the grief reaction is delayed and is first manifest by a sudden change in behaviour such as violent outbursts and withdrawal. Due to the delay in response, it is often handled inappropriately using medication or behavioural therapy (Hollins & Esterhuyzen 1997). In her study of the provision of education for carers of people with learning disabilities, Bennett (2003) found that many felt inadequately prepared to provide bereavement support to their clients. This may indicate why people with learning disabilities are sometimes inappropriately managed with medications and behavioural therapies.

People with learning disabilities generally do better if they are adequately prepared for the loss and are supported through the bereavement. Crick (1988) identified areas of need in people with learning disabilities who had been bereaved. These include:

Complicated grief

While it is acknowledged that each person’s course of mourning will be unique, uncomplicated grief is characterized by the patterns and feelings described above. When grief becomes complicated it can lead to unusual patterns of behaviour. Several types of complicated grief are recognized. These are:

Palliative care

This part of the chapter explores what palliative care is and how palliative care services are organized within the UK. Nurses have an integral role to play in providing patients and families with high quality palliative care. The term palliative care is derived from the Latin word pallium, meaning ‘to cloak’. Thus palliative care focuses on symptom relief without curing the illness which is causing the symptoms.

Palliative care has been known by many terms over the years. These include terminal care, hospice care, care of the dying, end-of-life care and supportive care (Payne 2004). Problems have arisen with the terminology used previously. For example, Doyle et al (1998) argue that the term ‘terminal care’ is confusing because it implies there is little that can be done for the patient. This is in stark con-trast to the active and sometimes interventionist nature of palliative care, which may include chemotherapy (anti-cancer [cytotoxic] drugs to destroy cancer cells) and radiotherapy (the use of high energy X-rays to destroy cancer cells). Similarly the term ‘hospice care’ is misleading as it gives the impression that the approach is limited to those in the care of hospice professionals rather than indicating an approach to care that can be used in any setting and at every stage of the illness journey. This term, however, was first used to denote the hospice movement, which advocated a move away from acute hospital care for patients who were dying of incurable illnesses such as cancer. ‘End-of-life’ care similarly falls short of what encompasses palliative care as it implies that care is only given when the patient is at a certain stage of their illness. End-of-life care certainly falls within the remit of palliative care but palliative care is much broader, with many authors arguing that it should begin at the time of diagnosis. Palliative care then is essentially care of patients and their families whose illness is no longer curable and should begin when this is known.

What is palliative care?

The World Health Organization (WHO 2004) has provided a useful definition:

Palliative care improves the quality of life of patients and families who face life-threatening illness, by providing pain and symptom relief, spiritual and psychosocial support from diagnosis to the end of life and bereavement.

In this definition the holistic nature of palliative care is evident as it encompasses the multidimensional approach. The WHO outlines the principles that underpin the approach to palliative care, as follows:

Palliative care provides relief from pain and other distressing symptoms. It:

(WHO 2004).

The WHO definition and the principles of palliative care illustrate the complexity of palliative care. For this reason it is unlikely that any one healthcare professional will be able to deliver palliative care in isolation, rather it has to be a MDT approach. Members of the MDT mayvary in their level of input over the course of the patient’s illness but examples of people involved are:

Furthermore, it is unlikely that palliative care will be delivered in a single place. Thus health and social care professionals working in hospitals, community, hospices and voluntary sectors must understand the palliative care approach (Box 12.5).

Teamwork in palliative care

Think back to a placement where you cared for a patient who had a terminal illness.

The MDT should have a shared idea of common roles and accepted objectives; in order to achieve these, traditional professional roles may have to be adjusted. There is great value in including family and carers within the team, as many patients express a wish to be cared for in their own homes. Families and carers must be well informed and supported in order for this to happen.

The provision of high quality palliative care is a multidisciplinary endeavour. However, nurses usually work very closely with patients and their families during the course of their illness and in bereavement, and therefore have a central role in providing information, care and support.

Palliative care for children

The WHO (2004) states that palliative care for children is closely related to adult palliative care and provides principles for care of children with chronic non-curative illness. Palliative care for children:

(WHO 2004).

Overview of palliative care services

Founding of the UK palliative care movement is widely attributed to Dame Cicely Saunders who pioneered the palliative care approach with the opening of St Christopher’s Hospice in 1967. However, it took a further two decades for palliative medicine to be recognized as a medical speciality.

The palliative care approach was developed in St Christopher’s Hospice with the aim of providing care that was informed by research and was sensitive to the needs of individual patients. Since then it has proliferated throughout the UK and it is now delivered in a variety of settings:

Palliative care has been subdivided into general and specialist palliative care.

General palliative care

This is based on the principles of palliative care and should be a core skill of every clinician. It is widely referred to as ‘the palliative care approach’. The aims are to promote both physical and psychosocial well-being and are a vital part of all clinical practice whatever the person’s illness or its stage. It includes holistic consideration of the family and domestic carers rather than purely medical/physical aspects.

Specialist palliative care

Specialists in palliative care provide specialist palliative care. According to Finlay and Jones (1995) it:

Palliative care in hospitals

Despite evidence that the majority of terminally ill patients wish to die at home, most people die in an NHS hospital. Reasons for this include:

Patients may be under the care of general physicians or surgeons and be nursed in general wards. The palliative care approach should be adopted in such cases and there are established hospital palliative care teams in the majority of UK hospitals.

Hospital palliative care teams are ideally multidisciplinary; however, some specialist nurses still work alone. The role of the MDT is to provide specialist advice and support for patients with complex palliative care needs and support and advice for general staff caring for the patient.

While many palliative care team members will have a background in cancer care, their remit extends to other diseases, e.g. heart failure. They provide advice on issues such as pain and symptom management, emotional support for the patient and family, advice and support to hospital staff and the primary care team, liaison with other palliative care services and bereavement care.

Hospice care

Hospice care developed largely from the work of charitable organizations such as Marie Curie Cancer Care, Sue Ryder and Macmillan Cancer Support. The services provided include:

Although hospice inpatient units were initially set up to deal with the needs of patients suffering from terminal cancer, hospice services are increasingly being sought from patients with other terminal illnesses such as motor neurone disease. On the other hand, children’s hospices have developed for the needs of a much broader range of diseases as children usually die of degenerative disease (Katz 2004).

Patients are admitted to inpatient hospice care for a variety of reasons, including assessment, rehabilitation, pain and symptom management, short respite stays to help relieve carers and terminal care. The environment is more homely than hospitals, and centres on the individual patient’s needs. Families are encouraged to be involved in care where appropriate and visiting tends to be open. Staff normally have access to specialized training and education in palliative care.

The main aim of hospice daycare is to enhance the quality of life of the patient, as well as providing respite for relatives caring for the patient at home. The focus of care is on providing support and advice on pain and other distressing symptoms, as well as providing emotional support and rehabilitation, all of which may enable the patient to remain at home. Most daycare units run as multidisciplinary community services where the patient remains under the care of the GP. The role of healthcare professionals in the daycare unit therefore necessitates close liaison with the patient’s GP and other members of the primary care team (see Ch. 3).

Hospice at home provides extra care and support to terminally ill patients in their own homes and offers support to relatives and carers. It supplements the services normally provided by district nurses. ‘Hands-on’ care and support are provided by a team of qualified nurses and auxiliary staff who provide most, if not all, of the nursing care that would be available in an inpatient hospice. This makes it possible for people to spend the last weeks or months of their illness in familiar surroundings, with their family and friends around them.

Marie Curie nurses care for almost 50% of all people with cancer who die in their own homes (Marie Curie Cancer Care 2005). They provide free expert nursing care and emotional support to families affected by cancer. They are available for periods during the day and night, which helps to reduce patient stress and anxiety (see Ch. 11) and gives carers the opportunity to rest or sleep.

Community palliative care team

A community palliative care team may consist of specialist palliative care nurses who visit patients and families in their own home, or they may be part of a bigger team such as those in a hospice. Increasingly, hospital and community are becoming more closely integrated and working across the boundaries.

Similar to the other palliative care services described above, the role of the community palliative care team includes providing support and advice on pain and other distressing symptoms, providing emotional support for the patient and their carers and also providing bereavement support. Charities such as Marie Curie Cancer Care and Macmillan Cancer Support have led the way in providing community-based support by providing nursing services.

Communicating with patients and families

Communication is central to high quality palliative care. Communication skills are often regarded as ‘something nurses can do’ (see Ch. 9). However, in palliative care effective communication requires considerable knowledge and skill. Studies exploring the perceptions of patients and families indicate that considerable scope exists to improve meeting their information and communication needs (Wilkinson 1991). Kinghorn (2001, p. 167) states that ‘effective and sensitive communication is the heart of comforting, assessment of need, expression of psychological/social/spiritual distress as planning for what may be perceived to be an undesirable and premature end to life’.

Speaking to dying patients and their families is difficult and uncomfortable and is usually led by experienced clinicians. Studies have identified that health professionals often ‘block’ patients when they seek information (Wilkinson 1991, Heaven & Maguire 1996). It is important to acknowledge that awkwardness when dealing with advanced illness and death is universal and nursesshould not view inabilities as personal failings. However, it is the responsibility of nurses and other healthcare professionals to develop, refine and advance their communication skills. While it is necessary to understand theories of communication, reflecting upon clinical practice to reach new understandings is critical (Box 12.6).

Care and symptom control

There are a variety of symptoms associated with terminal illness, e.g. pain. These are discussed below.

Managing pain in palliative care

Cancer is not synonymous with pain; however, 75% of patients with cancer may experience pain (Twycross 1997). The WHO suggests that up to 80% of patients with pain may have their pain adequately controlled by following a simple three-step approach to pain management:

Box 12.7 WHO three-step analgesic ladder

Paracetamol or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), e.g. diclofenac sodium 6 adjuvant.

Drugs that are not analgesics act as adjuvants to relieve pain. For example, dexamethasone (a corticosteroid) is used to relieve pain resulting from raised intracranial (within the cranium) pressure, as it reduces swelling of the brain. Other adjuvants include anticonvulsants, e.g. carbamazepine and sodium valproate, or antidepressants, e.g. amitriptyline, for nerve pain. These drugs are used not for their primary action but for the actions that relieve the sensation of pain for the patient.

Step 2 – Mild to moderate pain

Weak opioid, e.g. codeine or dihydrocodeine 1paracetamol, or NSAIDs 6 adjuvant.

Step 3 – Moderate to severe pain

Opioid, e.g. morphine sulphate 1 paracetamol, or NSAIDs 6 adjuvant.

[From WHO (2005)]

The principles of pain management in adults outlined above are equally applicable to children. Assessment of pain is crucial to effective management. Pain assessment self-report scales have been developed specifically for children such as the ‘faces scale’ (see Ch. 23).

The WHO pain ladder (see Ch. 23) can be used for managing pain in children. However, calculation of drug dosages is complex and should be calculated according to the weight of the child (Goldman 1998).

Breathlessness (see Ch. 17)

Breathlessness (dyspnoea) is an unpleasant and often frightening sensation of being unable to breathe easily. It is a very common symptom in patients with all types of terminal illness.

Some causes of breathlessness may be reversible and therefore accurate assessment of the cause is vital (Table 12.1).

Table 12.1 Reversible causes of breathlessness

| Cause | Management |

|---|---|

| Infection | Antibiotics if appropriate |

| Anaemia | Iron supplementation or blood transfusion |

| Pleural effusion (presence of fluid in the pleural cavity) | Drainage of effusion |

| Bronchospasm (spasm of the smooth muscle of the bronchi leading to bronchoconstriction and narrowing) | Nebulized bronchodilators, e.g. salbutamol |

| Pulmonary embolism (clot in the blood supply to the lungs) | Anticoagulant therapy |

Hypoxia (reduced levels of oxygen in the tissues) may result from any of the above causes.

Oxygen therapy is used for hypoxia.

Care of the breathless patient should be individualized and a multidisciplinary approach is essential. Advice from the physiotherapist is often particularly helpful on positioning patients in a bed or chair, control of breathing rate and relaxation methods (Davis 1997) (see Chs 10, 17). Breathlessness has both physical and psychological elements. Not being able to breathe easily can cause intense fear, which causes the patient and family to become anxious, and the physical symptom worsens. This cyclical pattern requires sensitive support and careful management. Reassurance and support can help reduce anxiety, along with relaxation techniques (see Chs 10, 11) and anxiolytic drugs, e.g. lorazepam.

Excess respiratory secretions

Excess respiratory secretions often become problematic within the last days or hours of life. The build-up of secretions in the airways is due to the patient’s inability to cough up or swallow them. This presents as a noisy gurgle during breathing, often referred to as the ‘death rattle’ as it is associated with the terminal phase. The patient is usually in a state of altered consciousness at this stage and is not aware of the problem; however, it is particularly distressing for the family.

Careful positioning of the patient on their side may assist in relieving the problem for a short time. The registered nurse may carry out regular oral suctioning. Drugs such as hyoscine butylbromide may also be prescribed to reduce the secretions and hence the distressing sounds. These drugs, which also cause sedation, may be given by subcutaneous injection or via a syringe driver (see Chs 22, 23).

Fatigue

Fatigue is the most common symptom experienced by patients with advanced cancer. It is defined as ‘a total body feeling ranging from tiredness to exhaustion, creating an unrelenting overall condition which interferes with an individual’s ability to function to their normal capacity’ (Ream & Richardson 1996, p. 527). Fatigue is a difficult symptom to manage, as it is not merely corrected by rest. There are a number of physical and psychosocial causes of fatigue, some of which can be alleviated. They include:

Management of cancer-related fatigue is difficult and needs to be tailored to the needs of individual patients. Little research has been done in this area to support management strategies; however, reversible causes such as anaemia should be corrected. Some clinicians report an improvement in fatigue when patients are encouraged to do gentle exercise. It would appear that a balance between periods of rest and activity is the optimum for promoting well-being.

Nausea and vomiting

Patients may feel nauseated and retch for many hours before they vomit or they may not vomit but still suffer the unpleasant sensation of nausea. Nursing care such as ensuring easy access to vomit bowls, tissues and mouthwash, as well as ensuring privacy, can promote the patient’s comfort (see Ch. 19). Avoidance of strong odours and food smells can also help to reduce nausea. There are many causes of nausea and vomiting in patients with advanced illness (Lothian NHS Board 2001), including:

Some of the causes are reversible and treatment of nausea and vomiting depends very much on the cause. Reversible causes must be identified and treated appropriately through accurate assessment.

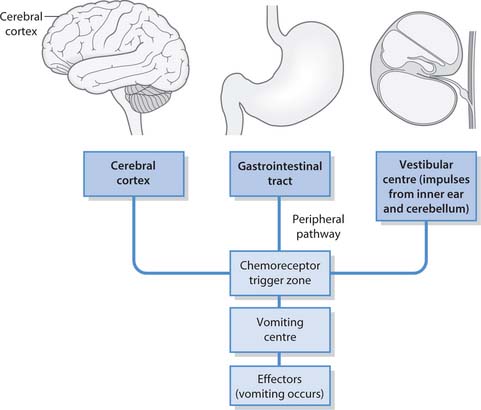

Vomiting is initiated and synchronized by two centres in the brain: the vomiting centre, which has overall control, and the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ). Both centres respond to various stimuli (Fig. 12.1). The vomiting centre and CTZ contain receptors able to respond to different stimuli arriving from the cerebral cortex, the vestibular centre (impulses from inner ear and cerebellum) and the gastrointestinal tract depending on the cause of vomiting. The receptors include histamine receptors (H1), acetylcholine receptors (AChm), dopamine receptors (D2) and those for 5-hydroxytryptamine receptors (5-HT3).

Nurses need to know about the receptors because each type of antiemetic (against vomiting) drug acts at a different type of receptor (Box 12.8). Therefore it is essential to use the appropriate antiemetic drug for the cause of the vomiting. They should always be prescribed and given when nausea and vomiting is anticipated, such as with some chemotherapy drugs. Nausea can be treated with oral drugs; however, alternative routes of administration must be used if the patient is vomiting, e.g. rectal, subcutaneous or intramuscular (see Ch. 22). It is important that the patient with nausea receives regular antiemetic drugs before vomiting occurs. Further reading suggestions (e.g. Prodigy guidance 2004) provide more information.

Box 12.8 Controlling nausea and vomiting – antiemetics and other drugs

[Resources: British National Formulary (BNF) – www.bnf.org.uk; BNF for Children – http://www.bnfc.org/bnfc Available July 2006]

Oral problems

Oral hygiene is very important for patients with terminal illnesses, especially when there is difficulty taking food and fluids or dehydration (see Chs 16, 19). The most common problems encountered are dry or sore mouth, oral thrush (candidiasis) and ulceration.

Constipation

Constipation is a significant problem for patients requiring palliative care and is a particularly distressing symptom. Constipation may also be the cause of other problems such as nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain and cramps, bloating, and faecal soiling and diarrhoea from faecal overflow.

Constipation may have a number of causes, e.g. opioid analgesics. This should be anticipated and a prophylactic laxative prescribed and administered. Immobility, inadequate food and fluid intake, as well as the patient’s illness, may all be causes of constipation. As with all symptoms, accurate assessment is crucial to determine the cause of the constipation. The patient’s normal bowel habit is recorded in order to assess how this has changed.

Simple measures may help, such as ensuring privacy and acting promptly to requests for a commode or help to get to the lavatory. Interventions that prevent or alleviate constipation are discussed in Chapter 21. Ensuring adequate fibre and fluid intake where appropriate may help; however, with some patients this will not be possible if their illness is advanced.

Terminal agitation

Terminal agitation or restlessness is common in patients in the terminal phase of the illness. At this time the patient may become confused, agitated and may also be hallucinating (a perception of the presence of something which is not there). Care should be taken to identify any treatable causes such as unrelieved pain and constipation. Similarly, if the patient is clear in their thought processes, time should be spent trying to identify if the patient has unresolved issues, as fear and anxiety may exacerbate this symptom.

A quiet, calming environment with familiar surroundings or people known to the patient may help; however, it may be necessary to use sedation to resolve agitation and calm the patient. Opioids can have a sedative effect although their use in this instance is not appropriate as they may induce further confusion and/or hallucinations. Sedative drugs such as haloperidol and/or midazolam can be administered either as subcutaneous injection or via a syringe driver in order to sedate and calm the patient.

Terminal agitation can be very distressing for relatives to watch; however, a simple and clear explanation as to the reasons for the confusion and the strategies used to try to alleviate it may be helpful in reducing their distress.

Death and dying

It has been identified that the palliative care approach is applicable in the early stages of chronic, non-curative illness. However, at the end of life this is particularly appropriate as it promotes quality of life and comfort regardless of the stage of the illness. In this section issues relating to death and dying are considered.

Death may result from trauma, or sudden or progressive illness, and nurses have a role in supporting patients and their family and friends during this time. Personal experiences of death vary and the cause, circumstances and support available influence how individuals experience death and dying. The nurse’s actions at the time of death can profoundly affect bereavement, grief and adaptation to the loss. The circumstances surrounding death are unique to each individual and family; however, there are likely to be physical, psychosocial and spiritual needs and the requirement for open and honest information.

Sudden death

When a person dies suddenly this is due to cerebral ischaemia (lack of blood flow to the brain). This can be caused by a stroke, heart attack, cardiac arrest or haemorrhage due to trauma.

Sudden death may result from an acute illness or trauma, accidents or suicide. When death is unexpected, the family and those closest to the deceased are likely to experience profound shock, numbness, disbelief and feelings of chaos and disorder. Sudden death due to accidents, suicide or other trauma is the main cause of death in young adults, particularly males, so meeting the needs of those closest to these patients is challenging (Box 12.9).

Sudden death due to suicide

Ben, who was 25 years old, suffered from severe depression. He committed suicide while a voluntary patient in a mental health unit.

Discuss with your mentor the potential impact of Ben’s death on his family and friends and the staff.

Student activities

Visit the Office for National Statistics website (www.statistics.gov.uk) and find out:

Wright (2002) suggests that in grounding sudden death in reality, an individual needs to reach a level of resolution and adaptation with which they can cope. There are three important factors in this process: perception of the event, external resources and inner resources.

Perception of the event

People search for information to help attribute cause and seek an explanation for what has happened. Some people may be unable to cope with information immediately following the bereavement so information giving should be tailored to meet individual needs (see ‘Breaking bad news’, Ch. 9). Nurses should also consider where people get support and information once their contact with healthcare professionals has ceased.

External resources

It is important to establish what support is available for the bereaved person. Initially support is likely to be provided by family and friends. It is therefore important that nurses identify who can be called upon to provide support, e.g. with transport home from the hospital if a close relative has died suddenly. Careful consideration must be given to what information should be given over the phone by the registered nurse who does not know the person and how they are likely to respond, especially if a relative is being asked to come in to an emergency department. Dealing with sudden death is demanding and requires sophisticated communication skills (see Ch. 9). Knowing what to say and when is important and nurses need to discern what information to give the bereaved person who may be so shocked they cannot think what to ask.

For hospital-based staff, contact with people who experience the sudden death of a loved one may be extremely limited. For many bereaved people the full impact of their loss may not be apparent for some time following the death. Untimely, unexpected and traumatic deaths may cause severe and prolonged grieving. It is therefore important for nurses to be aware of local resources and types of help available and to give this information to bereaved relatives, including information relevant to different faiths. One such source of support is Cruse Bereavement Care, which exists to promote the well-being of bereaved people and help them to understand their grief and cope with their loss (see ‘Useful websites’, p. 317).

Inner resources

Very individual coping strategies will be used by bereaved people in order to deal with the crisis of sudden death and its aftermath. When a sudden, unexpected death occurs there is usually no opportunity to be present at the time of death. This is thought to complicate the grieving process and how people cope with the bereavement. One of the most important issues in helping people to accept the reality of the death is knowledge of what happened at the end and nurses can help (Box 12.10). Relatives may ask if the person suffered or what their last words were and registered nurses should not avoid giving this information or indeed any information they have. Rather than traumatizing relatives, as is often thought to be the case, it is likely that providing information will help them cope with the reality of the situation.

Death of a child

Louisa, the eldest of three children, has recently been killed in a road traffic accident. Her parents are devastated and her mother cannot accept that Louisa is really dead. They have visited the mortuary many times to see Louisa and spend long periods of time there. They are increasingly distressed following each visit.

Viewing the body is also important in achieving understanding of the loss. Generally, even in traumatic death, relatives who view the dead person, especially if they were not present at the time of death, find this helpful (Wright 2002). Preparation of the bereaved for viewing a loved one is an important nursing role that can help to lessen the impact of seeing significant changes in body colour or trauma (see pp. 312–313).

Expected death and palliative care

Gradual expected death occurs when there is failure of one or more organs and/or systems that maintain the internal environment of the cells (homeostasis). As the internal environment deteriorates, an increasing number of cells and tissues malfunction, leading to system failure. For example, when the respiratory system fails, hypoxia (reduction of oxygen in the tissues) and hypercapnia (increased carbon dioxide in arterial blood) will result in the failure of other organs including the heart and brain (see Ch. 17).

When death is anticipated and expected, patients and families experience profound and individual physical and emotional consequences. Dealing with these experiences is crucial to the process of accepting and responding to the situation. Whatever stage of acceptance and resolution individuals have reached as the end of life approaches, appropriate care around the time of death is arguably one of the most challenging and responsible aspects of the nursing role.

The palliative care approach is applicable throughout the illness trajectory and, in the later stages of life, represents the best of care by combining the clinical, holistic and human dimensions of care. Uncontrolled physical symptoms in the last stages of life increase levels of distress for both the patient and family members (see pp. 306–309). Furthermore, the intense emotional impact for family members following death increases their risks of morbidity and mortality during the bereavement phase (Parkes 1998).

Recognizing that death is approaching

Knowing when a patient is likely to die is usually very important for family members, some of whom will normally wish to be present at the time of death. For people of many faiths it is especially important for the patient to have the next of kin present as religious rituals must be performed to ensure the dying person passes on to the next life (see pp. 314–315). Families may ask if they should take a break from sitting at the bedside or when they should contact other family members who live at a distance. An important role of the nurse at the end of life is ensuring that family members are alerted to the imminence of death and have privacy to say their goodbyes and grieve. While it is not possible to predict exactly the last stages of life, there are recognized signs that death is imminent (adapted from National Council for Hospice and Specialist Palliative Care Services 1997). They include:

Causes of death and the need for palliative care

People die in their own home, in a hospital, hospice or a residential/nursing home. Increased life expectancy and the shift from infectious diseases to degenerative diseases such as cancer, heart disease or stroke as causes of death have meant that deaths are concentrated in old age. Many people facing death live alone and lack informal support.

Addington-Hall (1996) surveyed the symptoms experienced in the last year of life in three groups of patients: those with cancer, heart disease and stroke. Symptoms including pain, nausea and vomiting, etc. were prevalent in advanced cancer. People with heart disease had breathlessness and people dying from strokes experienced mental confusion and incontinence. Significantly, this survey revealed that while people with cancer experienced more symptoms, the duration was shorter than for the other two groups. Palliative care is frequently associated with cancer; however, there is increasing recognition that all patients with advanced, non-curable illness require palliative care.

Main causes of death in the UK

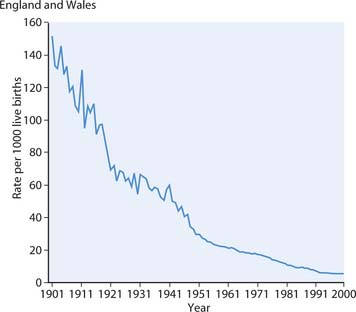

The 2001 census of the population of the UK identified that, for the first time, people over 60 years of age form a larger part of the population (21%) than children aged less than 16 years (20%) (National Statistics 2003a). Furthermore, people aged 85 and over have increased to 1.9% of the population. These population trends correspond with life expectancy (the expectation of number of years of life at birth), which continues to improve. In addition, ‘the infant mortality rate has fallen dramatically throughout the 20th century’ (National Statistics 2003b, p. 7) (Fig. 12.2, p. 312).

Fig. 12.2 Infant mortality rate 1901–2000 in England and Wales

(reproduced from National Statistics, Health Statistics Quarterly (18) Summer 2003, with permission of HMSO Licensing)

In the year 2000, around 80% of deaths were of people over 65 years of age compared with 20% in 1901. However, improvement in life expectancy is accompanied by significant rises in the so-called degenerative diseases which can be linked to lifestyle factors such as cancers and cardiovascular diseases. Therefore the correlation between life expectancy and healthy life expectancy is important, as evidence to date suggests that while life expectancy is increasing, healthy life expectancy is not, and the ‘burden of disability’ towards the end of life is increasing. Cardiovascular diseases and cancer are significant causes of death of adults in the UK and most European countries. These trends are predicted to continue due to increasingly sedentary lifestyles, smoking and diets high in saturated fats (National Statistics 2003a).

It is important for nurses to understand population trends and causes of morbidity (incidence of a disease) and mortality (numbers of deaths) as they are involved in meeting the health needs of populations and caring for patients and families around the time of death (Box 12.11).

Causes of death

Select a cause of death relevant to your chosen branch, e.g. suicide/injury undetermined deaths, sudden infant death syndrome, child deaths due to accidents or deaths from heart disease.

Student activities

[Resources: National Statistics 2005 Annual update 2003 mortality statistics: cause (England and Wales). Health Statistics Quarterly (25) Spring 2005. Online: www.statistics.gov.uk/downloads/theme_health/HSQ25.pdf; Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency – www.nisra.gov.uk/publications/default.asp?cmsid=20_22_37&cms=demography_Vital%20statistics_Deaths1by1cause&release=future Scottish Executive – www.scotland.gov.uk/Topics/Statistics/17861/10369 All available July 2006]

Death states and the physiology of dying

In order to help nurses cope with patients, relatives and their own feelings around the time of death, it is useful to understand what is happening when people die. Death may be sudden due to accident or illness, or be ‘expected’, for example when a patient has an advanced non-curable illness such as chronic respiratory disease, cardiovascular disease or cancer.

Death as a process begins with the failure of a body system, which then affects other systems (see p. 311). Medical interventions, which can keep people alive even when vital functions have been lost, have created difficulties in deciding when a person can be declared ‘dead’. This is particularly so when brain function is lost and a person’s body may continue to function or be supported on a ventilator/respirator. Distinctions are normally made between three states:

The physiological and physical events occurring at death include:

Care around the time of death

Whether a patient dies suddenly or the death is expected, the actions of those involved in caring for the patient and family are of utmost importance. Care that meets the needs of individuals around the time of death has been shown to impact on how well they cope following bereavement. Providing care when a patient reaches the last stages of life is an important nursing role. Regardless of the clinical area, nurses are likely to care for people who are dying. All nurses therefore require appropriate knowledge to inform care planning.

The Macmillan Gold Standards Framework (GSF) is designed to offer guidance to primary healthcare teams to improve the planning of palliative care so they can meet the needs of patients and carers. Evaluation of the GSF has shown that its implementation has improved care (Thomas 2004). While designed for primary care, the seven principles of the GSF provide guidance for nurses involved in caring for dying patients regardless of the clinical setting. Box 12.12 (see p. 313) outlines a framework for care.

Box 12.12 A framework for palliative care, dying and death

[Adapted from National Council for Hospice and Specialist Palliative Care Services (1997) and Thomas (2004)]

Communication

Coordination

Control of symptoms (see pp. 306–309)

Carer support

Integrated care pathways (ICPs), a multidisciplinary care tool designed to enhance communication and continuity of care (see Chs 3, 14), are increasingly being used and evaluated in palliative care. Information about ICPs in palliative care is provided in Further reading (e.g. Ellershaw & Wilkinson 2003).

Providing support and information around the time of death is important, particularly where a patient may be classified as being either brain stem dead or in a PVS. Tactful handling is required at a time when nurses may be struggling with their own feelings (Box 12.13). Many relatives may not have seen a dead person before so preparation and gentle explanation are necessary.

Personal experience of death

If you have experienced the death of someone close to you, reflect on the things others said or did, both helpful and unhelpful. If you have not experienced the death of someone close, think what might be helpful.

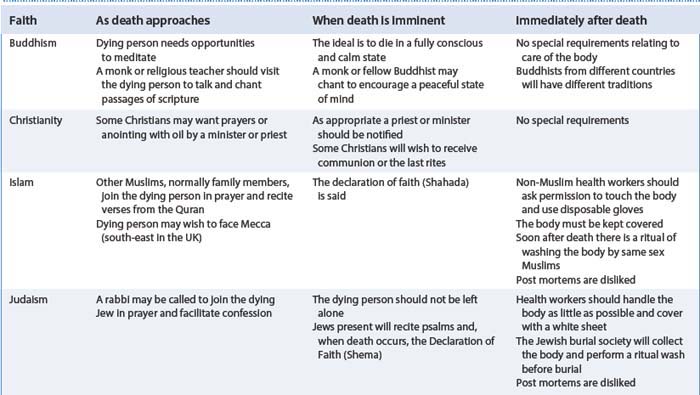

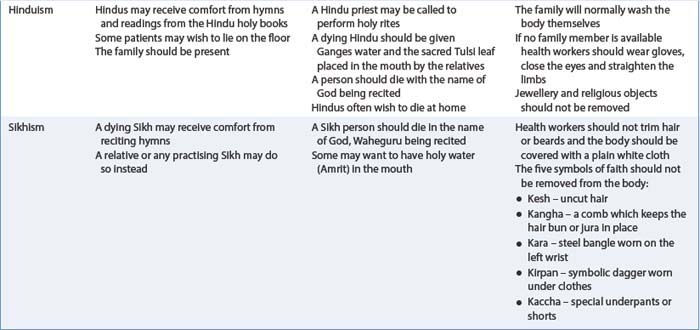

Cultural aspects of dying and death

If nurses are to provide appropriate care at the end of life they must understand and meet the spiritual and cultural needs of individuals. Different cultures and societies approach death and grieving differently and nurses need to communicate with patients and families to establish what their needs and wishes are and ensure particular requests are communicated among the MDT. Nurses should establish if patients have any religious beliefs, as some patients may not have a belief or faith. They may, however, have requests for care around the time of death, e.g. humanists who neither believe in God nor an afterlife but celebrate the life that has been (British Humanist Association 2005). Table 12.2 provides an overview of religious practices around the time of death (see also the BBC website in ‘Useful websites’, p. 317).

Caring for people who are dying or bereaved requires knowledge of specific cultural and religious rituals in order to provide culturally aware care. Nurses need to know who to contact and when from the person’s own culture or religion to ensure traditional practices are followed and the patient’s wishes are met. The best way to ensure appropriate end-of-life care is to take sufficient time to explore and assess the wishes and needs of the patient and family. Integration of cultural issues into care assessments and care planning is crucial as is the communication between team members (see Ch. 9). If the patient’s needs are carefully assessed, documented and communicated amongst team members, the experience of dying will significantly improve for those involved (Box 12.14).

Care after death

Certification of death is a legal requirement normally carried out by a doctor. After death, the patient is referred to as ‘the body’. The body should receive care – known as ‘laying out or last offices or last act of care’– as soon as possible to minimize tissue damage or disfigurement. If the patient has died at home, the undertaker/funeral director or family is likely to attend to the laying out of the body.

It is important to check with the family as some cultures and faiths have important rituals about how the body is treated after death (see Table 12.2). The family should be asked if they wish to be involved as many people find it helpful to accept the reality of the death if they are involved in a final act of care (Box 12.15, see p. 316).

The final act of care/last offices

What to do after a death

Think about the type and presentation of information needed by family or friends after a death.

Student activities

[Resource: Rights and responsibilities: death and bereavement – www.direct.gov.uk/RightsAndResponsibilities/Death/fs/en]

End-of-life ethical issues

Ethical issues at the end of life are complex and require careful consideration. Although students are not responsible for making care decisions at the end of life, they will be exposed to ethical issues and may contribute to debating issues and the plan of care. Decision-making in palliative care is governed by the ethical principles of respect of autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence and justice (see Ch. 7).

At the end of life there are numerous issues that present ethical dilemmas for those involved. These include:

Hydration at the end of life

The provision of nutrition and hydration is a part of the nursing role and failing to meet these needs may be seen as failing to work within the Nursing and Midwifery Council code of professional conduct: standards for conduct, performance and ethics (NMC 2004). However, in palliative care the beneficial effects of hydration are inconclusive and hydration may not be essential for comfort in the last stages and may even cause discomfort by increasing respiratory secretions and urinary output.

The psychological and emotional aspects of hydration must be considered alongside the physiological effects when active hydration is considered as part of care. Deciding whether it is acting in the patient’s best interests is complex and requires regular review of the evidence to support clinical decisions, the patient’s condition, prognosis and wishes of the patient and the family.

| BBC | www.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/people/features/world_religions/index.shtml |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Cancer Research UK | www.cancerresearchuk.org |

| Available July 2006 | |

| CancerBACUP | www.cancerbackup.org.uk |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Cruse Bereavement Care | www.crusebereavementcare.org.uk |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Hospice Information Service | www.hospiceinformation.info |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Macmillan Cancer Support | www.macmillan.org.uk |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Marie Curie Cancer Care | www.mariecurie.org.uk |

| Available July 2006 | |

| National Council for Palliative Care (NCPC) (many useful publications) | www.ncpc.org.uk |

| Available July 2006 | |

| PRODIGY (guidance available for many palliative care issues, e.g. cough, dyspnoea, respiratory secretions) | www.prodigy.nhs.uk/guidance |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Scottish Partnership for Palliative Care | www.palliativecarescotland.org.uk |

| Available July 2006 |

Addington-Hall J. Heart disease and stroke: lessons from cancer care. In: Ford G, Lewin I, editors. Managing terminal illness. London: Royal College of Physicians, 1996.

Bennett D. Death and people with learning disabilities: empowering carers. British Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2003;31(3):118-122.

Black D. Childhood bereavement: distress and long-term sequelae can be lessened by early intervention. British Medical Journal. 1996;312(7045):1496.

British Humanist Association. 2005. Online: http://www.humanism.org.uk/site/cms. Available July 2006

Bruce L, Finlay T, editors. Nursing in gastroenterology. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1997.

Crick L. Facing grief. Nursing Times. 1988;84(28):61-63.

Davis CL. ABC of palliative care: breathlessness, cough, and other respiratory problems. British Medical Journal. 1997;315:931-934.

Doyle D, Hanks G, MacDonald N, editors. Oxford textbook of palliative medicine, 2nd edn, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Finlay I, Jones R. Definitions in palliative care. British Medical Journal. 1995;311:754.

Goldman A. ABC of palliative care: special problems of children. British Medical Journal. 1998;316:49-52.

Heaven K, Maguire P. Training hospice nurses to elicit patient concerns. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1996;23:280-286.

Hollins S, Esterhuyzen A. Bereavement and grief in adults with learning disabilities. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;170:497-501.

James N. Emotional labour: skill and work in the social regulation of feelings. The Sociological Review. 1989;37(1):15-42.

Katz JS. Overview. In: Payne S, Seymour J, Ingleton C, editors. Palliative care nursing: principles and evidence for practice. Buckingham: Open University Press, 2004.

Kindlen M, Smith V, Smith M. Loss, grief and bereavement. In: Lugton J, Kindlen M, editors. Palliative care: the nursing role. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1999.

Kinghorn S. Communication in advanced illness: challenges and opportunities. In: Kinghorn S, Gamlin R, editors. Palliative nursing. Bringing comfort and hope. Edinburgh: Baillière Tindall, 2001.

Kubler-Ross E. On death and dying. New York: Macmillan, 1969.

Lindemann E. Symptomatology and management of acute grief. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1944;101:141-148.

Lockhart-Wood K. Nurse–doctor collaboration in cancer pain management. International Journal of Palliative Nursing. 2001;7(1):6-16.

Lothian NHS Board. Lothian Palliative Care Guidelines. Edinburgh: Lothian NHS Board, 2001.

Marie Curie Cancer Care. 2005. Online: http://www.mariecurie.org.uk. Available September 2006.

National Council for Hospice and Specialist Palliative Care Services [now The National Council for Palliative Care (NCPC)]. Changing gear – guidelines for managing the last days of life in cancer. London: NCPC, 1997.

National Statistics 2003a Census. 2001 – National Report. Online: www.statistics.gov.uk/census2001/census2001.asp.

National Statistics. 2003b Twentieth century mortality trends in England and Wales. Health Statistics Quarterly (18) Summer 2003. Online: http://www.statistics.gov.uk/downloads/theme_health/HSQ18_revised_21Aug03.pdf. Available July 2006.

Nursing and Midwifery Council. code of professional conduct: standards for conduct, performance and ethics. London: NMC, 2004.

Open University. Religious practices wall chart. Milton Keynes: The Open University, Department of Health and Social Welfare, 1992.

Parkes CM. Coping with loss: bereavement in adult life. British Medical Journal. 1998;316(7134):856-859.

Parkes CM, Weiss RS. Recovery from bereavement. New York: Basic Books, 1983.

Payne S. Overview. In: Payne S, Seymour J, Ingleton C, editors. Palliative care nursing: principles and evidence for practice. Buckingham: Open University Press, 2004.

Phillips S. Labouring the emotions: expanding the remit of nursing work. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1996;24(1):139-143.

Ream E, Richardson A. Fatigue: a concept analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 1996;33(5):519-529.

Smith P. The emotional labour of nursing. London: Macmillan, 1992.

Stroebe MS, Hansson RO, Stroebe W, Schut H. Handbook of bereavement research: consequences, coping and care. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2002.

Thomas K. Caring for the dying at home. Oxon: Radcliffe Medical Press, 2004.

Twycross R. Symptom management in advanced cancer, 2nd edn. Oxon: Radcliffe Medical Press, 1997.

Weller RA, Weller EB, Fristad MA, Bowes JM. Depression in recently bereaved prepubertal children. American Journal Psychiatry. 1991;148:1536-1540.

Wilkinson S. Factors which influence how nurses communicate with cancer patients. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1991;16:677-688.

Winston’s Wish. 2005 For grieving children and their families. Online. Available: http://www.winstonswish.org.uk.

Worden JW. Grief counselling and grief therapy. London: Tavistock/Routledge, 1991.

World Health Organization. 2004 WHO definition of palliative care. Online: www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en.

World Health Organization. 2005 WHO’s pain ladder. Online: www.who.int/cancer/palliative/painladder/en.

Wright B. Death, grief and loss. In Walsh M, editor: Watson‘s clinical nursing and related sciences, 6th edn, Edinburgh: Baillière Tindall, 2002.

Department of Health. 2006 NHS Help is at hand. A resource for people bereaved by suicide and other sudden, traumatic death. Online: http://www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/13/90/07/04139007.pdf. Available September 2006

Diamond J. Because cowards get cancer too. London: Vermillion, 1998.

Dickenson D, Johnson M, Katz JS. Death, dying and bereavement. London: Open University Press, 2000.

Ellershaw J, Wilkinson S. Care of the dying. A pathway to excellence. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Faull C, Carter Y, Daniels L. Handbook of palliative care, 2nd edn. Oxford: Blackwell, 2005.

Gordon T. A need for living. Glasgow: Wild Goose Publications, 2001.

Holland K, Hogg C. Cultural awareness in nursing and health care. London: Arnold, 2001.

Kennedy C. Death and dying. In Kindlen S, editor: Physiology for health care and nursing, 2nd edn, Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2003.

Lugton J, McIntyre R. Palliative care: the nursing role, 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2006.

Picardie R. Before I say goodbye. London: Penguin, 1998.

Prodigy guidance 2004 Prodigy guidance. (2004, minor update 2005) Palliative care – nausea/vomiting/malignant bowel obstruction. Online: http://www.prodigy.nhs.uk/palliative_care_nausea_vomiting_malignant_bowel_obstruction. Available July 2006.

REFLECTIVE PRACTICE

REFLECTIVE PRACTICE CRITICAL THINKING

CRITICAL THINKING

NURSING SKILLS

NURSING SKILLS ETHICAL ISSUES

ETHICAL ISSUES