Chapter 4 Learning and teaching

Introduction

Nursing programmes aim to provide safe, knowledgeable, skilful and caring practitioners who are able to provide effective evidence-based care (see Ch. 5). Nursing students take on the role of learner at both university and in placements. In placements, mentors are involved in formal and informal teaching and learning experiences with students and patients/clients. From an early stage you will be involved in informal and simple patient/client teaching activities, assuming the role of teacher while the patient/client becomes the learner. It is therefore important to understand the processes of teaching and learning from both learner and teacher perspectives to maximize both your own learning and that of the people in your care.

‘Learning is the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience’ (Kolb 1984, p. 38). Learning is all about educating oneself to think, as well as appreciating the importance of reflecting on that thinking in order to learn. Individuals learn and behave in different ways as a result of their educational experiences. The result of learning is commonly seen as a relatively permanent change in behaviour.

Theories of learning

There are different theories of learning, none of which has gained universal acceptance, and these are discussed in this section.

Behaviourism

Behaviourism as a theory of learning was dominant in the 1960s. Its origins lie with the Russian psychologist, Pavlov, and the American behavioural psychologist, Skinner.

Classical conditioning is the type of learning made famous by Pavlov’s experiments with dogs where Pavlov found that if he rang a bell and at the same time fed the dogs, the dogs began to associate the sound of the bell with food. Eventually the dogs would salivate when they heard the bell despite not receiving food. This is called a ‘conditioned response’.

Skinner’s experimental work involved rats, pigeons and latterly humans. Skinner found that rats or pigeons placed within a cage-like box containing a food tray and a lever to release food would demonstrate trial and error behaviour until the lever was pressed. Over time, the animal learned the connection between pressing the lever and the release of food. Skinner’s work led to what is known as ‘operant conditioning’, by which a new behaviour can be taught assuming that rewards are related to the learner producing successive approximations to the desired behaviours.

Behaviourists assert that memory is the result of strengthening of associations between a stimulus and a response. It therefore follows, according to behaviourists, that almost all kinds of learning can be described and explained in terms of the gradual learning of stimulus and response. A stimulus is equivalent to an event, person or thing in an environment, whereas a response is something that the learner does. The theory of stimulus–response in learning is most useful in providing advice regarding how to teach simple knowledge and skills, and has also made a valuable contribution to training programmes for people who have a learning disability (Bastable 2003).

Any event that increases the probability of a piece of behaviour being displayed by the learner is called a ‘reinforcer’. Skinner proposed that by providing reinforcement to an individual in a particular situation displaying certain behaviour, they would be more likely to display this behaviour again when in a similar set of stimulus conditions. For example, when training an animal to perform particular tasks, the teacher looks for behaviour consistent with what is desired and positively reinforces that until the animal displays the desired behaviour. This technique is called ‘shaping’. Following shaping, prompting or guiding, or ‘chaining’ can be commenced.

Once each component of a task has been learned, the steps have to be joined together into a sequence so that completion of the first step becomes a stimulus signal-ling the second step, and so on. Backward chaining can alsobe useful, particularly when teaching children and peoplewith a learning disability (Box 4.1).

Box 4.1 Using backward chaining in teaching

Goal: John will put his trousers on.

The technique involves breaking down the task or skill to be learned into small manageable steps. For example, teaching John how to put on trousers with an elasticated waist could be broken down as follows.

To use backward chaining, the teaching sequences would start with step 6. The teacher would carry out steps 1–5 for John and then get him to do step 6 himself.

On completion of step 5, John would be asked to put his hands on the sides of his trousers with his thumbs inside the waistband. Then, while guiding John’s hands, the teacher asks him to pull his trousers up. On completion of the task, praise is given by saying, e.g. ‘That’s great, you pulled your trousers up!’

Once John has learned step 6, he would then start at step 5 and so on until he is able to complete all six steps by himself.

The learner is presented with a task with all the steps completed except the last one, which they must complete and the process of completion then reinforces the behaviour. In this way, the individual gains instant satisfaction of completing the task and is more likely to have a positive learning experience. In this type of learning it is important to use social reinforcement along with praise for completing the task because social approval is very powerful. Social reinforcers include non-verbal communication such as smiling, eye contact, winking, physical contact such as a hug or pat on the back, nodding or clapping (see Ch. 9). Social reinforcement can be particularly effective with children and young people and to some adults when given by people whose opinions are valued or respected (Box 4.2). It is vital that any form of social reinforcement is:

Social reinforcement

These Skinnerian techniques are reputed to be most effective in teaching social skills. They can also be used to decrease the occurrence of undesirable behaviours. To summarize, behaviour which is rewarded is likely to be repeated; conversely, behaviour which is ignored is likely to fade.

Another strategy to use in order to reduce behavioural problems is positive programming. LaVigna and Donnellan (1986) suggest this is the preferred strategy and provide an example of an individual who hits staff. Firstly, this behaviour needs to be seen within the context of the setting so that a judgement can be made as to whether it is inappropriate. Assuming it is, the reason for such behaviour needs to be identified. In this case, the individual hits staff when he’s engaged in an activity that he does not enjoy and hits out to signal that he wants a break. Using the positive programming strategy, the individual is provided with a card that says ‘Break’ and told that when he shows this to staff, they will allow him a 5-minute break before resuming the activity.

Cognitive theories of learning

Cognition relates to the mental processes involved in thinking, perceiving, problem-solving and remembering. The mainstay of cognitive theory is that thinking and reasoning play a major part in how people learn. Reinforcement is not an automatic process but rather the learner realizes the benefits of adopting certain behaviours. Through paying attention, the learner selectively observes and extracts what they perceive as valuable components of behaviour. Proponents of cognitive theory argue that people learn from experience, by ‘doing’, and that this learning is then inserted into their framework of existing knowledge. The act of doing involves repeated practice and the provision of reinforcement or rewards encourages further learning.

Gestalt learning theory is a form of cognitive theory that emphasizes that it is important to view the whole when learning rather than taking a reductionist approach which involves looking at small parts that make up the whole. For example, when teaching a skill it is best to demonstrate the whole procedure at normal speed so that the learner can gain a holistic view of what is expected. Thereafter, the skill is usually broken down into its component parts in order to learn. The aim is that, with practice, the learner will be able to perform the whole skill competently.

Another form of cognitive theory is the assimilation theory developed by Ausubel et al (1978). It is aptly named because it emphasizes the importance of integrating new knowledge with existing knowledge. Just before the preface of Ausubel et al’s (1978) book is an often-cited quotation by Ausubel:

Humanistic theories of learning

These emerged in the 1950s and 1960s from individuals such as Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers. Both Maslow and Rogers rejected the behaviourist theory that human beings were unthinking and can be shaped and programmed by patterns of rewards and punishments. Instead they focused on people’s potential, believing that humans strive to reach the highest possible level of achievement.

Maslow (1954) is best known for developing the hierarchy of needs which is important in respect to learning as these needs play an important role in motivation. The hierarchy is usually presented as a pyramid with the most basic needs (physiological) at the base. The key aspect of Maslow’s work is that, before someone can learn effectively, their most basic needs must be met. For example, if people are hungry, thirsty or in pain they are unlikely to be able to concentrate in order to learn. The next layer in the pyramid relates to safety needs. If learners’ physiological needs are met but they fear for their physical or psychological safety, then their learning will be impeded.

The third layer relates to the need to belong and be loved. Even if the previous two levels are met, if a learner feels excluded from a group, this will affect their learning because their belonging and love needs will not be met. The fourth layer relates to esteem. Despite having their belonging and love needs met, if they perhaps ask a question and someone ridicules them for asking a silly question, then that too will affect their learning as their self-esteem needs would not be met. Individual self-esteem needs can be met through recognition, acceptance, praise and a belief that others acknowledge their worth. The final layer in the pyramid is called self-actualization. This, according to Maslow, is the highest form of achievement where the learner achieves their full potential.

Rogers (1994) argues that human beings have a natural potential for learning, which is most significant when what is to be learned is perceived as relevant and the learner is active in the process. Furthermore, Rogers argues that self-concept and self-esteem are necessary during any learning experience. The most lasting form of learning, according to Rogers, is that which involves the learner being self-directed. In other words, the self-directed learner is motivated to explore a topic at their own pace and in their own time and relishes the experience of being independent and creative. If, however, learning involves a change in someone’s behaviour or is viewed as a threat to how they organize themselves or to the way they live, it is often resisted. That is why, for example, attempts to change one’s eating habits or sedentary behaviour can be very difficult to achieve.

Rogers (1994) developed ‘client-centred therapy’ in which he aimed to provide his clients with the knowledge and skills necessary to find their own solutions to their problems rather than being told what they should do. Roger’s work led to what we know today as student-centred learning. This involves the teacher being the facilitator of learning: guiding students on how to learn, fostering their enthusiasm, initiative and responsibility, and providing them with a variety of learning experiences through which they can discover and learn. Student-centred learning is defined by Cannon (2000, p. 2) as ‘ways of thinking about learning and teaching that emphasize student responsibility for such activities as planning learning, interacting with teachers and other students, researching and assessing learning’. It also encourages the use of group learning so that, as well as having peer support, students also learn about working in teams (Bastable 2003). Learning how to work effectively as a team member is a fundamental skill for all healthcare professionals.

Andragogy

Malcolm Knowles coined the term ‘andragogy’ at the end of the 1980s to differentiate it from ‘pedagogy’. Pedagogy, in its strictest sense, relates to how children learn. The word pedagogy is derived from the Greek words paid, meaning child, and agogus, meaning leader of, and therefore pedagogy literally means the art and science of teaching children. Pedagogy involves:

Andragogy is about how adults learn. Knowles et al (1998) argue that adults learn best when they are involved in doing something or are active in the process. In short, andragogy reflects a student-centred approach to learning. Being active in the learning process facilitates the formation of meaning and provides depth to understanding. Knowles identified certain characteristics in respect to adult learning. Adults need to know why they should be learning something and how it will be beneficial to their work or other facets of their lives. Adults’ approach to learning is more problem-solving in nature as opposed to subject-centred. Adults prefer to take charge of their own learning or, in other words, to be self-directive and responsible. Adults use their varied life experience as a rich resource for learning and connect any new learning to their existing knowledge and experience. When planning any educational activity involving adults, it should be underpinned by adult learning principles (Box 4.3).

Box 4.3 Summary of adult learning principles

[From Kaufman (2003, p. 213)]

In relation to the principles of adult learning, or andragogy, the models of experiential learning by Kolb (1984) and Race (1993) are now explored.

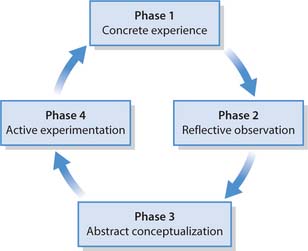

Kolb’s experiential learning cycle

Kolb (1984) presented a model of learning consisting of four phases, known as Kolb’s experiential learning cycle (Fig. 4.1). The cycle is based on the premise that people learn much more effectively when they are encouraged to be active in the process. Kolb suggests that learning results from two things: the way an individual perceives and the way the individual processes what they perceive. Kolb (1984) suggested that learning styles are composed of a combination of the four phases in his experiential learning cycle. He stated that individuals perceive either through concrete experience or through more abstract concepts and that they process information in one of twoways: through active experimentation or through reflec-tive observation.

Concrete experience

This phase starts with a concrete experience in that the individual begins by doing something. During the concrete experience, learners are actively involved and tend to rely on their feelings rather than using a systematic approach to problems or situations. According to Mills (2002) during concrete experience individuals use all five senses: sight, smell, touch, taste and hearing in order to deal with the obvious, i.e. the here and now.

Reflective observation

During this phase the learner requires to take time out to consider, or reflect, on what has happened during the concrete (or doing) phase. The learner relies on objectivity and careful consideration to search for meaning by studying things from a variety of different perspectives and asking questions (Bastable 2003).

Abstract conceptualization

This phase involves trying to make sense of what has happened. It involves individuals visualizing, using their imagination and conceiving ideas to move beyond the obvious to uncover the more subtle implications (Mills 2002). The learner makes comparisons between what they have done and what they have reflected upon, and draws on their existing knowledge. Learners may draw on theories, models and previous observations and experiences. During abstract conceptualization, learners tend to rely more on logic and ideas in regard to problems or situations rather than on their feelings (Bastable 2003).

Active experimentation

This is the final phase of the cycle where the learner considers what they have learned and how they are going to implement it into practice. In other words, they place what they have learned into context so that it is both meaningful and useful to them (Bastable 2003).

Summary

The above way of thinking about learning follows the principle that learning is continuous, as people continually test out new ideas in practice and adjust their ideas and behaviour in light of their experience. Kolb highlighted two particular aspects:

At this point it may be useful to think about an example (Box 4.4).

Learning to ride a bicycle

Student activities

Race’s ripples model

Race, a British educationalist, presented his alternative experiential model of learning in 1993. This model is also based on experiential learning – or ‘learning by doing’ – and reflects Kolb’s view that by receiving feedback from others and reflecting on one’s learning is of paramount importance to the learning experience. Race’s model consists of four elements (Fig. 4.2), which together constitute successful learning. Race’s model differs from Kolb’s because, rather than using a cycle, Race’s model involves four processes that interact with one another rather like ripples on a pond.

Wanting

This is the central process and lies at the heart of the model. Race believes that wanting or needing to learn is crucial to the internal motivation that drives the learner in the first place. Motivation ripples out from the heart of the model into the surrounding layers.

Doing

From wanting or needing to learn the next process is doing, which corresponds with the belief that adults learn best by doing or being active in the process.

Digesting

This has parallels with the second stage in Kolb’s cycle as both involve the learner reflecting on their experience in order to make sense of it and developing a sense of ownership.

Feedback

The fourth process is feedback. Receiving timely feedback is viewed as essential since it is important to the quality of the learning experience to see both the results of one’s learning and to obtain feedback from others regarding how effective it was. According to Race’s model, feedback is as crucial as the central process of needing and wanting.

Summary

Figure 4.2 suggests that motivation ripples outwards in successive layers, with positive feedback sending the ripples back towards the centre; this in turn has a positive effect on needing and wanting. The position of feedback on the outside ring of the model symbolizes the fact that feedback is gained from external sources (teachers, peers, self-assessment) and needing and wanting are derived internally. In between these two are ‘doing’ and ‘digesting’, both of which are influenced by internally generated needing and wanting as well as by externally generated feedback.

Now carry out the activities in Box 4.5.

The learning process

People have a tendency to adopt ways of learning with which they feel most comfortable. These are known as learning styles, which are explored at the beginning of the section. Thereafter, approaches to learning and reflection are discussed.

Learning styles

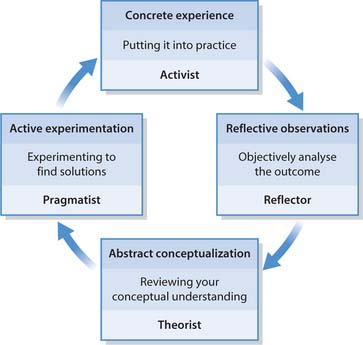

The term ‘learning styles’ refers to the way in which individuals choose to learn. According to Bastable (2003), learning style models are based on the idea that certain characteristics of learning styles are biological in origin, while others are developed as a result of environmental influences. Different people have different learning needs and bring their own individual knowledge, experience and resources to the learning process and learn in different ways. It is important to be aware of the differing learning styles because it is recognized that people learn better and more quickly when teaching methods match their preferred learning style. When someone learns successfully, their self-esteem increases, which in turn has a positive effect on their learning. Honey and Mumford (1992) built on Kolb’s work and identified four learning styles or learning preferences that individuals naturally prefer to use: activists, reflectors, theorists and pragmatists (Fig. 4.3). You should consider the activity in Box 4.6 as you read the remainder of this section about learning styles.

Your learning styles

Many people have a combination of characteristics from different learning styles rather than having characteristics from only one.

No one learning style is better or worse than another and learning styles change over time.

Activists

People who prefer doing things and involving themselves fully in new experiences are referred to as activists. They enjoy the concrete experience and have the following characteristics:

Reflectors

Reflectors prefer to reflect and observe. They tend to collect information, sift through it thoroughly, look at the issues from a range of perspectives and, not surprisingly, can be slow to make decisions or come to any conclusions. They have the following characteristics:

Theorists

People who prefer to focus on trying to understand reasons, ideas and relationships are called theorists and ask the question ‘What?’. They enjoy using their logic and ideas (rather than their feelings) in order to understand situations and problems (abstract conceptualization) and have the following characteristics:

Deep, strategic and surface learning

Another facet to learning styles is the depth of effort to which learners exert themselves. Different intentions lead to contrasting study strategies and learning experiences. People do not usually just adopt one approach but rather, based on the circumstances, choose the approach that most suits a particular set of circumstances. Using deep or strategic approaches is associated with a better quality of learning (Table 4.1).

Table 4.1 Characteristics of surface, strategic and deep learning approaches (after Ramsden 1988)

| Surface | Strategic | Deep |

|---|---|---|

| Intention to reproduce, memorize | Aware of learning context | Intention to understand |

| Passive approach | Active approach | Active approach |

| Rely on rote learning | Actively seeking information re-assessment requirements | Looking for meaning |

| Interacts actively with content | ||

| Driven by fear of failure | Extrinsic motivation | Intrinsic motivation |

| Not looking for relationships between ideas | Competitiveness and self-confidence | Relating ideas to previous knowledge/real life |

| Driven by hope for success | Examines evidence critically | |

| Intrinsic motivation |

Deep approach to learning

This approach is generally expected of learners studying at university. Students who adopt a deep approach to their learning study with the aim of deriving meaning from what they learn, and then compare that meaning to previous experiences and ideas. Such students are intrinsically motivated to learn successfully about the subject area and, as a result, the deep approach to learning is associated with long-term success (Kirby et al 2003). The same applies to patients or clients who learn about their illnesses or conditions, as those who adopt a deep approach are likely to access the Internet to obtain information and question healthcare professionals in order to clarify their understanding.

Strategic approach to learning

The intention of learners using this approach is to achieve the highest possible grades. Learners take a strategic (sometimes called achieving) approach to maximize their marks or grades by systematically managing the time and effort they put into their study. These learners, often motivated by competition, are alert to what the assessment criteria and requirements are and often gear their work towards the perceived preferences of lecturers.

Surface approach to learning

The intention in this approach is to cope with course requirements. Learners adopting this approach are primarily motivated by a fear of failing to meet course requirements. They study without reflecting on either what they are doing or why they are doing it. They treat each aspect of learning as an unrelated bit of knowledge, which in turn makes it difficult to make sense of new ideas. Learners try to ‘suss out’ what the teacher wants and aim to provide this by concentrating solely on assessment requirements and routinely memorizing facts and procedures. Learners using a surface approach rarely achieve understanding and it is therefore not surprising that this approach is asso-ciated with poor academic performance.

Summary

Before reading on, you should carry out the activities in Box 4.7. When overloaded with coursework it is likely that a strategic approach will be taken. If the subject matter is compulsory but boring, a surface approach may be taken in order to meet minimum requirements. Where there is an intrinsic interest in the subject matter, such as when a client or patient wishes to learn about a health problem, then a deep approach is more likely to be taken.

Reflection

Essentially reflection is an active, conscious act in which an individual examines their experiences, beliefs, values, behaviour and knowledge that leads to a new understanding and appreciation of the situation which prompted the reflective process (Boud et al 1985). It is a process that involves looking beyond the immediate situation and delving below the surface in order to provide care relevant to the particular context of the patient or client. Stepping back in this way informs practice, creates learning and brings new meaning. From that understanding, judgements can be made on how to ensure one’s practice is based firmly on evidence.

Dewey (1933) initially brought the idea of reflection to nurses’ attention. In the 1980s, Schon’s work highlighted the central role of reflection in professional practice, predominantly in teaching and nursing (Foster & Greenwood 1998). Schon (1983) described reflection as having two constituents:

Greenwood (1993) added a third dimension to reflective practice – ‘reflection-before-action’. Greenwood argued that reflection-before-action was important as it related to practitioners reflecting about what they intended to do before they actually did it and in this way minimize the risk of making errors.

Reflection is therefore the process of examining and thinking about what we do within the context of the world around us. Reflection is more than just describing what we do or an event that occurred. It goes beyond that to thinking about why we do things, whether they have gone as intended, why they did or did not go well and/or why and how we might do things differently the next time.

Purpose of reflection

Being a reflective practitioner is essential to being a nurse and, indeed, is an expected outcome of all healthcare programmes. Reflection facilitates understanding of both oneself and others within the context of practice and encourages thinking about practice. Nursing students must learn about the importance of reflection as a way of linking theory to practice. The emphasis placed on the process mirrors the value placed upon reflection for the profession as a whole. There are a number of ways to encourage the use and development of the skills of reflection. These include regular reflective group sessions with peers and academic staff, keeping a reflective journal, log or diary, and incorporating reflection within written assessments.

Johns (1999) began an article about reflection with the following:

A.A. Milne commenced Winnie-the-Pooh with the story of Edward Bear being dragged downstairs behind Christopher Robin bumping on the back of his head. Milne noted that as far as Edward Bear knew, it was the only way of coming downstairs, although it sometimes felt there was another way: ‘If only he could stop bumping for a moment and think about it.’ Taking the analogy further, the moment of reflection begins when the bumping stops and it is possible to stand back and think.

Models of reflection

There are several models of reflection and three are considered below. They all contain the same principles but are differentiated by the level of detail they provide.

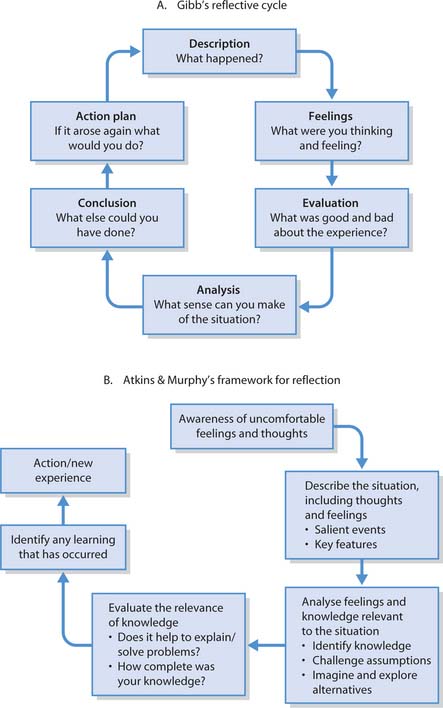

Gibbs’ reflective cycle

Gibbs (1988) presented a reflective cycle as a way of providing structure for practitioners to follow when reflecting. It consists of six sequential steps, beginning with the description of an event through to producing an action plan for future practice (Fig. 4.4A).

Fig. 4.4 Models of reflection. A Gibb’s reflective cycle (reproduced from Gibbs 1988). B Atkins and Murphy’s framework for reflection (reproduced from Atkins & Murphy 1993. The work is also available from www.glos.ac.uk)

Atkins and Murphy’s framework for reflection

Atkins and Murphy presented the framework for their reflective model in 1993 (Fig. 4.4B) and is more detailed than Gibbs’ model. This model emphasizes the skills used in the reflective process, namely:

When using Atkins and Murphy’s model it is important to recognize that the first step of awareness of uncomfortable feelings and thoughts can be stimulated by positive as well as negative experiences. For example, during a teaching session it becomes apparent that evidence demonstrates that an aspect of care you have been performing in practice is no longer appropriate. The experience is positive in that the teaching session involved disseminating up-to-date good practice, but it also produced uncomfortable feelings as the evidence supporting the new practice was more than 6 months old and in that time you have been practising unaware of the new evidence.

The final step in Atkins and Murphy’s model is also action as in all reflective models. Finishing a reflective account with an action plan is a fundamental premise because, as a practice-based profession, nursing is about seeking to learn from experience in order to improve practice.

LEARN framework for reflection

The College of Nurses of Ontario, Canada (1996) developed this framework. It is presented as a cyclical process containing the five steps that should occur during the process of reflection. LEARN is an acronym for these five steps (see Box 4.8).

[Reproduced with permission from the College of Nurses of Ontario]

Using the LEARN framework

The process of reflection

Brown et al (2003) suggest the following as triggers or stimuli for reflection:

You should now carry out the activities in Box 4.9. The trigger or stimulus for reflection is often referred to as a critical incident. A critical incident is defined as an event that has an impact or significant effect on your learning or practice. Analysing critical incidents is a useful way of gaining an understanding of the dimensions of your role and interactions with patients/clients and other healthcare professionals.

Identifying an incident to reflect on

Student activities

Reflection begins with choosing an incident that represents an issue that warrants further exploration for any of the reasons listed above. The first step involves the nurse/practitioner becoming self-aware, accepting that there may be other ways of thinking about or practising nursing, and being honest about how a significant event affected them as an individual and the impact that this had within the practice setting. This is important for linking theory to practice.

The next step is description, where the individual comprehensively describes verbally and/or in writing all components of the significant event, constantly bearing in mind the importance of maintaining confidentiality (NMC 2004; see also Ch. 7). The incident should be described by including where and when it happened, what actually happened in detail (who did what, said what, etc.) and your own thoughts and feelings during and after the incident.

This is followed by broadening and deepening your understanding by exploring existing knowledge and theories that influenced what happened in the significant event, and exploring and challenging your assumptions. Probe the incident by answering the following questions:

In this phase new knowledge is integrated with existing knowledge to solve problems creatively and predict consequences. It is usually at this stage that the process identified in the above steps is written up using relevant literature to support assertions, judgements and conclusions (Box 4.10).

Reflecting on your practice

Student activities

When writing up a critical incident analysis or a reflective account, the first person (I) is used rather than the third person which is normally used in academic writing. Use of the third person provides distance from both the incident and the reflective process, which is inappropriate when the focus should be on the individual person’s journey. It is essential that written reflective accounts abide by The NMC Code of Professional Conduct: Standards for Conduct, Performance and Ethics (2004) and protect individual anonymity and confidentiality in relation to those involved in any incidents or events (Box 4.11).

Box 4.11 Maintaining confidentiality in reflective accounts

‘On an early shift in the third week of my surgical placement I watched Staff Nurse Robin Hood (pseudonym) teaching a patient called John Smith (pseudonym) how to change his colostomy bag. The way that Robin explained the procedure to John was very clear and as John had been encouraged to watch how his bag was changed since his operation the whole teaching process seemed to go well. Robin was very careful to explain each step to John, emphasizing particular points such as the importance of cleaning and drying the skin surrounding the stoma, making sure that there were no wrinkles in the adhesive dressing around the stoma and ensuring that the bag was securely fastened. I really thought the way that Robin stressed the importance of listening for the bag clicking into place was especially useful as that is one of the points that I always find reassuring when I change a colostomy bag.’

In longer reflective accounts or coursework, this may be achieved by inserting the following near the beginning: ‘In order to maintain confidentiality (NMC 2004) all the names of those involved have been replaced with pseudonyms.’

Once written, it is useful to share your reflective analysis with others as this facilitates learning from others’ perspectives, allowing further exploration to be undertaken as appropriate. It is also good practice to further reflect on the process of sharing your analysis with others (Box 4.12).

Sharing your reflective experience

The final step in the reflective cycle is evaluation, where a judgement takes place in order to develop a new perspective on the critical incident or significant event. The new perspective is developed from the broadening and deepening of understanding and the acknowledgement of how the individual would adopt different practices in the future. The cycle ends with the development of an action plan including specific learning outcomes (see Box 4.20, p. 117) for future development. Burns and Bulman (2000) suggest practical tips to assist in the process of reflection (Box 4.13).

Box 4.20 Smart learning outcomes

M: measurable – so that there is evidence that they have been achieved

A: action-orientated – verbs should lead or drive them

R: relevant – both in terms of the nature and the reason for them

T: time-restricted – so that that there is a target date for successful completion.

Box 4.13 Practical tips for reflection

[From Burns & Bulman (2001, p. 35)]

Factors influencing learning

There are a number of factors that influence learning. These include motivation and readiness to learn, difficulties people may have in the process of learning and the environment in which learning takes place.

Motivation

Motivation influences what people do (if there is a choice), how long they do something and how well they do it. Motivation is a key factor in successful learning and is a central feature in most theories of learning. Without motivation learning does not take place, as we need to be motivated enough to pay attention while learning. There are two sources of motivation:

Internal, or intrinsic, motivation arises from within the individual and is made up of personal factors that make them want to learn. Internal motivation is longer lasting and more self-directive than external motivation. This is because praise or concrete reward or incentive must be provided repeatedly to reinforce external motivation (see ‘Behaviourism’, p. 99). For individuals who are externally motivated, the desire to learn is secondary to the reward gained from learning. According to Knowles et al (1998), adults’ motivation to learn is largely internally generated through self-esteem, quality of life and job satisfaction. Adults who are motivated to seek out learning experiences do so primarily because they have a use for the knowledge or skill being sought.

Since motivation is essential to learning it is important to be aware of the factors that enhance and diminish it, since there are many barriers to motivation. Factors that enhance and sustain motivation include a warm and accepting learning environment, incentives such as praise, feedback and knowledge of one’s progress, and the way in which learning materials are organized. As can be seen from Box 4.14, the factors associated with diminishing motivation are more numerous than those which enhance it. The best way, therefore, to motivate adult learners is to enhance their reasons for learning and decrease the barriers.

When thinking of motivation related to patient/client education, additional barriers must also be considered. The individual’s perception of their state of health can shape their motivation to learn as can their stage of development (Ch. 8) and ability to understand (Ch. 9). Confusion, pain, lack of sleep, noise, interruptions or lack of privacy can interfere with a patient’s/client’s ability to concentrate and therefore learn. The nurse as teacher who is insensitive to people’s cultural, spiritual and/or social needs can also diminish motivation to learn (Box 4.15).

Motivators: patients and clients

Student activities

Readiness to learn

‘Readiness to learn’ means that a learner is receptive and wants to engage in the learning process. In other words, they are motivated and able to learn. This is usually signalled by the learner asking a question and is crucial to the learning process – if an individual is not alert and motivated, learning will not occur. Nurses need to be alert for these signals, or cues, from their patients/clients. Coates (1999, p. 75) presents four groups of factors affecting readiness to learn:

Readiness to learn influences the timing of useful teaching. Patients/clients are generally more receptive to information about their illness shortly after diagnosis or prior to treatment and want information that is immediate and personally relevant (Bastable 2003). There are a number of ways in which relevant information can be imparted and at a time when readiness to learn is often at its highest. For example:

Bastable (2003) presents four types of readiness to learn and uses the acronym PEEK to describe these:

All of these should be considered as they can have an adverse effect on the degree to which learning will take place.

Assessment of physical readiness is important, espe-cially when the proposed learning requires physical strength or capability. For example, learning to walk with crutches requires physical strength and coordination, learning to inject a drug requires fine motor skills and good vision. Children or people with a learning disability who are learning to do up buttons also need fine motor coordination. Learning also requires the individual to be alert and have enough energy to concentrate (Bastable 2003).

Emotional readiness relates to a number of areas. For example, a little anxiety can motivate learning but undue levels are counterproductive. If patients/clients are scared or anxious about something they have to learn, this must be managed before learning can begin. For example, learning to self-administer injections may produce fear because of the necessity to inflict pain on oneself. Furthermore, fear and/or anxiety may cause patients or clients to deny the existence of their illness, which severely limits their readiness to learn. Emotional readiness also extends to students and ‘fear of the unknown’ often causes them anxiety. Despite mentors orientating nursing students into a new placement, students’ high anxiety levels may mean that although they are listening to what is being said, they may be unable to hear what is actually being said.

Experiential readiness is related to individuals’ past learning experiences and whether these have been positive or negative. Someone who has had previous poor learning experiences is unlikely to be motivated or willing to risk trying to acquire new knowledge or skills. According to Bastable (2003), experiential readiness involves the level of aspiration, past coping skills, cultural background and motivation.

Knowledge readiness relates to the individual’s current knowledge, their level of learning capability and their learning style. It is important to establish the individual’s knowledge base, as teaching what is already known is boring, demotivating and can be construed as insulting. Teaching should move from the known to the unknown. For example, when teaching a patient about their diabetes and the need for insulin, the nurse could ask them whether they already know that many people with diabetes require insulin. If is the case, moving from the known to the unknown could be explaining that the reason why insulin must be injected is because it is broken down and digested if taken orally and therefore would not work if given in tablet form.

Cognitive ability should be assessed because factors such as developmental stage, illness, dementia or learning disability can impair this to an extent that explanations need to be broken down into simple and smaller steps with frequent repetition built in. Simple language should be used. Including pictorial information can enhance understanding and convey meaning more readily. Nurses must seek ways to help individuals with a learning disability overcome any problems with processing of information (see below).

Individuals disadvantaged when considering information needs

Consideration requires to be given to people with particular needs, e.g. those who use wheelchairs, those with visual or hearing impairments (see Ch. 16), those with mental distress or illness, and those with learning disabilities. With a little thought, the needs of people with such difficulties can often be easily met. For example:

Computers are another learning tool that can be used for many people, particularly since technology permits accessibility, i.e. the ability to access material regardless of a person’s needs. They can be used in various ways such as accessing the Internet to find information and sending email messages to experts so that individual questions can be answered.

People who have problems in learning

There are a variety of problems that may impinge on how individuals learn. These include people with visual and/or hearing impairment, with mobility problems and those with mental health problems, e.g. dementia. Others may be those with:

Chapter 2 describes what learning disability nursing involves. In relation to teaching and learning, it is important to realize that many individuals with learning difficulties have average or above average intelligence. In fact, Albert Einstein, Richard Branson and Tom Cruise are among those known to have had problems with learning. So having a learning difficulty or problem does not mean a person cannot learn, it just means that they learn differently. Gates and Wilberforce (2003, p. 7) cite the Department of Health’s (2001) definition of the term learning disability, which is accepted to mean:

A significantly reduced ability to understand new or complex information, to learn new skills (impaired intelligence), with a reduced ability to cope independently (impaired social functioning) which started before adulthood, with a lasting effect on development.

It is important to recognize that people with learning disabilities form a very diverse group (Gates & Wilberforce 2003) and can have a number of problems such as difficulty in solving practical and abstract problems, difficulty in conceptualizing patterns and difficulty in communication generally. Having one or more of these difficulties means that such people acquire knowledge and skills more slowly than other people. Not surprisingly, feelings of frustration can emerge. However, being taught different learning strategies can help people learn more effectively, e.g. using pictorial instructions on cards or a computer screen to illustrate the key steps in the task to be learned. Good teaching practices should meet most of the disparate needs of all learners, including those with disabilities, whether these are caused by physical problems, dyslexia or learning disability (Doyle & Robson 2002).

Now read the information in Box 4.16 and carry out the activity at the bottom.

Language and reading difficulties

Language difficulty

Sheena has an expressive language difficulty. She has difficulty with expressing herself clearly and precisely because she finds it difficult to know which words are appropriate and how sentences should be structured. She also has problems copying from whiteboards, overheads and PowerPoint slides, and with note-taking, handwriting and spelling. To help Sheena she should be:

Reading difficulty

Fred has dyslexia. This causes him difficulty with decoding unfamiliar words, understanding what he reads, knowing the meaning of words read, and maintaining an efficient rate of reading. To help Fred, he should be encouraged to:

Student activities

[Resource: http://technet.gtcc.cc.nc.us/services/das/classroom_accommodations.html Available July 2006]

The learning environment

Regardless of where learning takes place – at university, in placements, clinics or day centres – creating a supportive environment is essential to successful learning. A supportive or conducive learning environment:

Anxiety has a direct bearing on an individual’s ability to learn as, physiologically, the stress response limits ‘the available nutrients for learning. This limits the connections between neurones resulting in slow thinking and depressed learning. Even short spans of stress will destroy a learner’s ability to distinguish between important and unimportant information’ (Dwyer 2001, p. 313). A conducive learning environment includes acquaintance of group members and this is why many courses start with ice-breaking exercises. Over time, the peer group develops cohesion in which each member begins to feel secure and knows that their contributions will be valued.

In applying Maslow’s hierarchy of needs to the educational environment (see p. 101), Hutchinson (2003) explains that an individual’s physical needs must be met first. Being in a cold or overheated room, sitting for long periods without adequate breaks or struggling to hear because of background noise all impinge on the ability to relax and pay attention. In terms of safety, Hutchinson (2003) points out that all those involved in teaching need to ensure that the learning environment is safe enough for learners to feel able to voice concerns or ask questions. Fostering mutual respect and acknowledging that learners’ self-esteem and pride can be injured through humiliation and lack of sensitivity can enhance the latter. Mutual respect also falls into Maslow’s belonging level by ensuring that all learners have their voice heard and their presence acknowledged. Additionally it is important to include and consult learners about planned and actual learning experiences. Self-esteem needs are met by providing feedback to make them feel valued. As Hutchinson (2003, p. 811) states, ‘praise, words of appreciation, and constructive rather than destructive criticism are important. It can take many positive moments to build self-esteem, but just one unkind and thoughtless comment to destroy it.’

Stuart (2003) identifies four categories that make up what is often a complex learning environment, namely:

At university, academic staff are responsible for creating a good learning environment and many institutions use a personal tutor system where a named lecturer guides and supports learners through their programme by providing feedback on draft assignments and one-to-one discussions regarding their personal and professional development.

In practice settings, ward managers, members of the multidisciplinary team and mentors are responsible for creating and fostering a supportive learning environment. Mentors play a pivotal role in supervising, supporting, facilitating and assessing students’ learning. In addition, healthcare assistants, patients/clients and their carers and families can also be sources from which to learn. An effective mentor is a good role model who has the ability to enhance the learning experience by being approachable, planning a variety of different learning experiences and maximizing learning opportunities. They appreciate the need to provide detailed feedback on how their mentee is progressing and offer guidance and support to improve their practice (Gray & Smith 2000). The same characteristics apply to any teaching, including that involving patients and clients.

Role models

Children are eager to find role models to copy or imitate, usually their parents. They watch them closely and follow their example. Role models (see Ch. 8) are also important to nursing and other healthcare students, as it is from them that students learn how to socialize into their profession. Nurses/healthcare workers tend to choose professional role models on the basis of their clinical skills, personality and teaching ability. From role models nursing students learn both appropriate and inappropriate behaviours, as role models can be good or poor. A good role model is someone a student can look up to, value and admire what they do and say, and may wish to emulate. A good role model is someone who demonstrates professionalism in all aspects of their practice whereas a poor role model does not. Nurses may think that they will only learn from good role models but by reflecting on what makes someone a good or poor role model means that students can learn from both. Negative role models can have unfortunate damaging effects as, rather than demonstrating good practice to nursing students, they exhibit poor practice. Inexperienced nursing students may not be knowledgeable enough to discriminate between what is safe and unsafe practice and therefore inadvertently learn poor practice (Box 4.17).

It is important to note that individuals do not deliberately choose to be role models. Healthcare professionals are role models, good or bad, at all times because others are constantly watching them and forming opinions. Not only are students observed by qualified healthcare professionals but also by other students, patients/clients, carers and their relatives and friends. Nurses are also expected to be role models in terms of pursuing healthy lifestyles, promoting health and wellness and, in time, implementing health promotion strategies. Nurses can also learn from patients/clients and carers as role models as they can inspire them in many different ways. Learning from people with longstanding health problems can be very valuable, as they often know more about their conditions than many healthcare professionals.

Summary

In terms of the learning environment, learning opportunities and experiences are paramount in learners achieving their learning outcomes. As well as academic and placement staff ensuring that there are appropriate learning opportunities and experiences available, learners also have a responsibility to take maximum advantage of the opportunities afforded to them.

Teaching and learning methods

There are different teaching and learning methods that include mass instruction, individualized and group methods. The method used impacts on the effectiveness of learning and retention of information. The more active people are in the learning process, the better the learning, which means that experiential learning is the most effective method. A variety of teaching and learning methods are discussed in this section, including action learning, problem-based learning and the use of portfolios.

Mass instruction methods

These include lectures using a variety of learning technologies such as PowerPoint, videos, patient information leaflets and posters. These methods do not encourage an active approach from participants. Lectures are only 5% effective as a teaching method while reading is 10% effective and a video or poster is 20% effective (Wood 2004).

Individualized methods

These include directed study such as computer-assisted learning, reflection, portfolios, workbooks, demonstrations, flexible learning materials and patient information leaflets. These methods encourage a more active approach from participants and are therefore more effective. Demonstrations are about 30% effective while practice by doing is around 75% effective (Wood 2004).

Group methods

These include reflective group sessions, group work, self-help groups, action learning (see below), problem-based learning (see below), tutorials and seminars. Again these methods require active participation. Wood (2004) states that discussion groups are about 50% effective in terms of the learning process.

Role of teacher

Student nurses will be involved in using these methods both to teach others (peers and patients) and as active participants. The teaching role is the most active of all and this is reflected in the effectiveness of teaching others (90% effective) as a way of improving one’s own learning (Wood 2004).

Action learning

Action learning describes a way of learning in which a group of people set about solving a problem. It involves learning in small cooperative groups, usually referred to as action learning sets. McGill and Beaty (1995, p. 11) define action learning as ‘a process of learning and reflection that happens with the support of a group or “set” of colleagues working with real problems with the intention of getting things done’. In other words, learners work together in a group to solve a real-life problem and reflect upon the actual actions required.

The fundamental premise of action learning sets is to work together on solving real-life issues and/or problems by learning from others and reflecting on the process. The emphasis on ‘real-life’ problems means that adult learners working in an action learning set bring their own problems to the learning set and work together on how these can be solved. There is no one correct answer or solution, so the task is to develop a workable solution for a particular context. Action learning is based on a number of educational beliefs:

Through team working individuals learn from each other by respecting different perceptions, perspectives, experiences and knowledge bases, all of which are harnessed in developing a solution to a problem or critical incident. Action learning is used to encourage team working in solving work-based problems, finding resources, preparing presentations and placement-related activities (Box 4.18).

Box 4.18 Principles of action learning

Problem-based learning

Problem-based learning (PBL) has its origins in medical education at McMaster University School of Medicine in Canada. Its use is widespread in a variety of disciplines, including nursing (Rideout 2001). PBL is a learning and teaching strategy that promotes learning by encour-aging learners to actively engage with others to analyse and solve problems – a fundamental skill required of all healthcare professionals.

PBL is a student-centred approach to learning that develops thinking and reflective skills with the aim of facilitating deep learning which is relevant to practice (Wilkie & Burns 2003). PBL involves active learning and develops team-working skills. It also requires students to solve problems, make decisions and explain new information gained to others, all of which facilitate a deep approach to learning.

The teacher, acting as a facilitator, introduces a problem-based scenario to learners without any previous teaching input or study. Working in small groups of 5–10, learners attempt to solve the problem(s) by suggesting a number of possible hypotheses and in doing so realize that their knowledge base is insufficient to solve or explain how the problem can be solved. This leads to learners identifying areas for further learning and collecting material to build the necessary knowledge and evidence base in order to solve the problem. Learners work though the problem in a systematic way and then reflect on both the content and the process so that they can meet the learning outcomes associated with the allocated problem scenario (Rideout 2001). Box 4.19 contains seven steps to solving a problem that can be used in any context, not just in PBL.

Portfolios

Tillema et al (2000, p. 270) define a portfolio as ‘a purposeful collection of learning examples collected over a period of time and gives visible and detailed evidence of a person’s competence. It serves as a tool to highlight progression in competence development under the control and responsibility of the person involved’. A portfolio can be used for a variety of purposes such as to:

Portfolios are a means by which learners accumulate evidence to demonstrate achievement of learning outcomes and/or competencies. As evidence is collected, a portfolio represents an individual’s learning, progress and achievement over a period of time. Portfolios encourage personal and professional development by the use of reflection, self-assessment, evidence of attainment of specific learning outcomes and competencies, and action plans for future learning. Reflection (see p. 106) is central to the learning processes involved in constructing and maintaining portfolios.

Having a portfolio to complete encourages deep learning, as the learner is required to actively engage in understanding the learning outcome and then compile evidence that demonstrates its achievement. Since portfolios are situated within practice, they encourage learners to make links between practice and its underpinning theory (Scholes et al 2004).

Portfolios provide a vehicle for discussion between learners and their mentor/tutor and, as such, are useful for monitoring progression. As a learner you should keep copies of all feedback from coursework and practice placements in your portfolio. Ensure that you read this through carefully before meeting with your personal tutor and/or mentor so that you can discuss the positive aspects of feedback and also those highlighted as requiring further development. Reflecting on your feedback, as well as the discussion with your tutor and/or mentor, should underpin your action plan to meet your personal learning needs. Portfolios are also the basis of Post-registration Education and Practice (PREP) and provide evidence of achieving both personal and specific professional learning outcomes.

The process of teaching

The following is common to all teaching methods/activities so while reading this section it is important to bear in mind that the information relates to readers in the roles of both student and teacher of others. This section explores what teaching includes and the steps involved.

Nursing students are often required to give presentations to their peers as part of their coursework. The rationale for this is that when preparing to teach others, teachers engage with the material very effectively and consequently their own learning becomes more in-depth and longer lasting. Likewise when students are involved in teaching patients, clients and/or carers they find that through the preparation required for the teaching session they also develop their knowledge of the subject matter.

Teaching is about passing on information, communicating, informing and instructing. Telling is not teaching. Teaching is usually perceived as a planned structured activity based on aims and learning outcomes (see p. 116), designed to bring about an increase or improvement in a person’s knowledge, skill or attitude on the subject.

Patient/client education is the ‘planned combinations of learning activities designed to assist people who are having or have had experience with illness or disease in making changes in their behaviour conducive to health’ (Coates 1999). Patients or clients often need to be taught skills and/or knowledge to help them maintain optimum health (health promotion, see Ch. 1), prevent disease, manage illness and/or facilitate their independence. According to Bastable (2003), patient/client education has the potential to:

The last bullet point above relates to information giving so that patients/clients can make informed decisions or give informed consent (see Ch. 6). Consent is normally prefixed by the word ‘informed’ and it is this which ensures that an individual who, before giving their informed consent, must:

Conflicts and challenges in giving information can arise for a number of reasons. Timing of information giving is important. Giving it too early can mean that key messages are forgotten and giving it too late can lead to individuals not having enough opportunity to reflect upon the information given and ask further questions for clarification. The Department of Health has key documents on the topic of consent (see ‘Useful websites’, p. 121).

Just as nurses assess, plan, implement and evaluate their care using the nursing process (see Ch. 14), the same stages apply to teaching. Bastable (2003) draws parallels between the process of education and the nursing process. The headings used in Table 4.2 are used to underpin discussion of the teaching process below.

Table 4.2 Nursing process and education process in parallel (from Bastable 2003)

| Nursing process | Education process | |

|---|---|---|

| Appraise physical and psychological needs |

|

Ascertain learning needs, readiness to learn and learning styles |

| Develop care plan based on mutual goal setting to meet individual needs | Develop teaching plan based on mutually predetermined behavioural outcomes to meet individual needs | |

| Carry out nursing care interventions using standard procedures | Carry out teaching using specific instructional methods and tools | |

| Determine physical and psychological outcomes and compare with intended plan | Determine behavioural changes (outcomes) in terms of knowledge, attitudes and skills, and compare with intended plan |

Assessment

Before setting out to ‘teach’ someone, it is essential to identify what the person/patient/client or groups of peers/patients/clients (hereafter referred to as learners):

Assessment of learners’ needs prevents unnecessary repetition of known material and saves time and energy for all parties. In order to teach, it is essential to read around the topic area including all the up-to-date literature and evidence (see Ch. 5 for literature searching and sources of evidence). Once what the learners already know has been established, assessment of what should be taught can begin.

Planning

The purpose of this phase is to plan what, how and when the intended teaching will take place. Following assessment, it will be evident what is already known and what remains to be taught. Knowing what to teach is not enough and planning will identify which particular elements of the topic are essential to teach and those that are interesting, but not essential. Writing aims and learning outcomes helps in deciding what is essential and what is not. The nature of the learning outcomes provides the basis of deciding which teaching methods are most appropriate to use.

Consideration needs to be given to creating a motivating learning environment (see p. 112). To achieve this, it is important to involve learners in setting their own learning outcomes when possible and to ensure that the outcomes are at the appropriate level so they move learners to a higher level of understanding.

Aims and learning outcomes

If there are no aims or learning outcomes, it is very difficult to focus one’s learning or indeed provide evidence that any learning has actually occurred. In other words, ‘if you don’t know where you are going, any bus will do’.

Aims attempt to provide shape and direction to teaching and learning. They are general statements representing an ideal, or aspiration, and illustrate the overall purpose of a course. Learning outcomes should be clear, speci-fic and contained within one sentence. Their purposes are to:

Bloom (1964) proposed three main areas, also called domains, which are helpful in writing learning outcomes:

Each of these domains is further broken down into a hierarchy with the simplest ones at the bottom. For example, the cognitive domain begins with knowledge and then moves upward to comprehension, application, analysis and ends with synthesis. This means that once knowledge of a topic is acquired, the individual can apply that knowledge by examining the relationship between elements and functions. Analysis is the next level that involves considering the context in which the topic area is being analysed, identifying and challenging assumptions by exploring alternatives and then making a judgement. Synthesis occurs when the findings from analysis are used to make suggestions or recommendations (Gopee 2002). An example of each level is given in Table 4.3.

Table 4.3 Examples of levels within the cognitive domain

| Domain level | Verbs associated with domain level | Example used in practice: On completion of the placement students should be able to: |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | Define, recall, identify, list, describe, draw, record | Recall knowledge and skills of assessment and its relation to planning, implementing and evaluating care |

| Comprehension | Describe, rephrase, explain, recognize, discuss, sort, rearrange, differentiate, estimate, conclude | Discuss barriers to communication within the assessment process |

| Application | Apply, generalize, demonstrate, illustrate, practise, relate, choose, develop, organize, use, transfer | Demonstrate a holistic approach to the assessment of patients and clients |

| Analysis (see below) | Analyse, distinguish, calculate, detect, deduce, classify, discriminate, categorize, test, inspect | Analyse the psychological and development needs of the sick child |

| Synthesis (see below) | Relate, produce, construct, organize, document, design, plan, propose, specify, derive, synthesize | Document the outcomes of nursing and other interventions relating to a patient or client with complex needs |

| Evaluation (see p. 119) | Judge, argue, justify, evaluate, assess, decide, compare, appraise, validate, select | Evaluate the role of the nurse within the multidisciplinary team context when caring for patients/clients with complex needs |

Effectively written learning outcomes must be unambiguous and should be SMART (Box 4.20). Chapter 14 identifies the need to be able to write SMART goals as part of the nursing process. Once SMART learning outcomes have been written, the next step is to devise a teaching (or lesson) plan.

Teaching plans

The purpose of these is to provide a guide so that nothing is missed out under the pressure of delivery. Writing the content clearly on cards, using colour to highlight keywords or important points can be helpful as is identifying those parts of the plan that could be omitted if required. For example, essential information could be in one colour and less important information in another. However it is best to use only two or three colours otherwise, rather than helping key points to stand out, it could cause more confusion.

Consideration should be given to a number of factors when planning a teaching session. These include the:

A teaching plan can be constructed using the following headings: content, teacher activity, learner activity, audiovisual aids, time.

Collecting, selecting and preparing relevant material

Once the learners’ existing knowledge has been assessed (p. 116), the topic areas that form the content of the teaching session are collected, prioritized and prepared. This stage involves searching the literature and evidence databases, collecting appropriate materials (such as already available patient information leaflets or compiling reference lists) and preparing notes.

Preparing material and planning methods to be used

The learning outcomes should be used to determine which teaching methods are appropriate. If, for example, one of the learning outcomes used the verb ‘debate’, then it would be appropriate to use a debate as part of the teaching session. Depending on the time allocated for the teaching session, a number of activities should be planned in order to maintain the learners’ attention. It is recommended that there is a change of activity every 15–20 minutes and more frequently when children or people with a learning disability are involved. The learning outcomes will guide decisions on appropriate content and level.

The structure of the lesson should be planned in a logical sequence with reference to the following maxims:

Your teaching plan should also contain:

Implementation

The introduction to any teaching session should demonstrate the significance and relevance of what is to be learned. An explanation of the purpose of the lesson, its relationship to previous teaching sessions (if any), an outline structure of the teaching session and the learning outcomes for the session should all be provided as this creates shared meaning and an early rapport with the learners. Whatever teaching method is used, it is essential that through a warm and accepting learning environment, key points or issues are communicated by speaking clearly, using pauses and ensuring the pace is not too fast. The teacher should continually gauge their audience’s understanding by observing their non-verbal reactions and repeating or re-phrasing as necessary.

Effective teaching depends on two interlocking factors: explanations and questions. Learning how to ask questions (see also Ch. 9) and give explanations requires practice. Hints on how to use questions and give effective explanations can be found in Box 4.21.

Box 4.21 How to use questions and give effective explanations

Using questions

Logical steps to provide clear and effective explanations

[From Spencer (2003)]

Teaching and learning clinical/practical skills

‘To be skilled is to be able to perform a learned activity well and at will’ (Cottrell 2001, p. 9). Skilled behaviour has to be learned and must be practised, e.g. learning to ride a bicycle (see Box 4.4, p. 103). What is learned in a skill is the selection of correct movements, at the right time and in the correct order. Tips for teaching a practical skill are as follows:

Evaluation

In this last phase, the teacher needs to decide whether the teaching plan has been effective and achieved what it set out to do, i.e. have the learning outcomes been achieved? This judgement uses the reflective cycle to assess one’s performance and asking the learner(s) for feedback on the teaching session. Reflecting on the outcomes of evaluation is the basis for improving your practice as a teacher.

A judgement is made about how the learner has progressed in their learning including, if appropriate, how well they have assimilated learning a new skill. This can be assessed by asking the learner questions that test their knowledge and then observing them performing the skill. Having undertaken evaluation, it is then essential to give feedback.

Giving feedback

Learning is an active process which requires feedback for the learner to know how effective their learning has been. As well as providing information about how well a learner has performed, feedback should also identify areas for further improvement. Moreover, feedback can be motivating.

Feedback must be specific rather than general. It should be immediate and contain details of what was good about the performance and which elements require further practice and attention. A rationale for the latter should always be provided. It is also a good idea to ask the learner to evaluate their own performance so that they develop the ability to make judgements about their performance. The quality of the feedback is important, as praise is motivating and can encourage the learner to try to do better the next time. Although giving feedback on both positive and negative aspects of a performance is important, the manner in which this is done is probably even more important. The key factors are listed in Box 4.22 (p. 119).

After giving feedback, the mentor should work with the learner to devise an action plan for areas requiring improvement.

Key words and phrases for literature searching

| Learning | Learning theories |

| Learning outcomes | Patient education |

| Learning styles | Teaching |

| British Dyslexia Association | www.bdadyslexia.org.uk/ |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Informed consent | www.dh.gov.uk/ |

| PolicyAndGuidance/Health | |

| AndSocialCareTopics/ | |

| Consent/ConsentGeneral | |

| Information/fs/en | |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Learning styles | www.support4learning.org.uk/sites/support4learning/education/learning_styles.cfm |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Sense UK (charity that provides services to support individuals with sensory impairment) | www.sense.org.uk |

| Available July 2006 |

Atkins S, Murphy K. Reflection: a review of the literature. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1993;18(8):1188-1192.

Ausubel DP, Novack JD, Hanesian H. Educational psychology: a cognitive view, 2nd edn. Rinehart and Winston, New York: Holt, 1978.

Bastable SB. Nurse as educator, 2nd edn. Boston: Jones & Bartlett, 2003.

Bloom BS. Taxonomy of educational objectives. New York: McKay, 1964.

Boud D, Keogh T, Walker D. Reflection, turning experience into learning. Worcester: Billing, 1985.

Brown G, Esdaile SA, Ryan SE. Becoming an advanced healthcare practitioner. Edinburgh: Butterworth Heinemann, 2003.

Burns S, Bulman C, editors. Students’ perspectives on reflective practice. Reflective practice in nursing, 2nd edn, Oxford: Blackwell Science, 2000. Chapter 6

Cannon R. 2000 Guide to support: the implementation of learning and teaching plan Year 2000. ACUE, The University of Adelaide. Online: http://www.adelaide.edu.au/clpd/materia/leap/leapinto/StudentCentredLearning.pdf. Available September 2006

Coates VE. Education for patients and clients. London: Routledge, 1999.

College of Nurses Ontario. The LEARN model of reflection. Ontario: College of Nurses, 1996.

Cottrell S. Teaching study skills and supporting learning. New York: Palgrave, 2001.

Cowan J. Assessment for learning: giving timely and effective feedback. Exchange. 2003;4:33.

Department of Health. Valuing people: a new strategy for learning disability for the 21st Century. Cm5086. London: TSO, 2001.

Dewey J. How we think. Lexington, DC: Heath & Co., 1933.

Doyle C, Robson K. 2002 Accessible curricula: good practice for all. University of Wales Institute, Cardiff. Online: http://www.ltsn.ac.uk/application.asp?app5resources.asp&process5full_record§ion5generic&id5128. Available June 2006

Dwyer B. Successful training strategies for the twenty-first century: using recent research on learning to provide effective training strategies. International Journal of Educational Management. 2001;15(6):312-318.

Foster J, Greenwood J. Reflection: a challenging innovation for nurses. Contemporary Nurse. 1998;7(4):165-172.

Gates B, Wilberforce D. The nature of learning disabilities. In Gates B, editor: Learning disabilities, 4th edn, London: Churchill Livingstone, 2003. Chapter 1

Gibbs G. Learning by doing. Sheffield: Further Education Unit, 1988.

Gopee N. Demonstrating critical analysis in academic assignments. Nursing Standard. 2002;16(35):45-52.

Gray MA, Smith LN. The qualities of an effective mentor from the student nurses’ perspective: findings from a longitudinal qualitative study. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2000;32(6):1542-1549.

Greenwood J. The apparent desensitisation of student nurses during their professional socialisation: a cognitive perspective. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1993;18(9):1471-1479.

Honey P, Mumford A. The manual of learning styles, 3rd edn. Maidenhead: Peter Honey, 1992.

Hutchinson L. Educational environment. British Journal of Medicine. 2003;326(7393):810-812.

Johns C. Reflection as empowerment. Nursing Inquiry. 1999;6(4):241-249.

Kaufman DM. Applying educational theory in practice. British Medical Journal. 2003;326:213-215.

Kirby JR, Knapper CK, Evans CJ, et al. Approaches to learning at work and workplace climate. International Journal of Training and Development. 2003;7(1):31-52.

Knowles MS, Holton EF, Swanson RA. The adult learner: the definitive classic in adult education and human resource development. Houston, TX: Gulf Publishing, 1998.

Kolb DA. Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1984.

LaVigna GW, Donnellan AM. Alternatives to punishment: solving behavior problems with non-aversive strategies. New York: Irvington, 1986.

Maslow A. Motivation and personality. New York: Harper and Row, 1954.

McGill I, Beaty L. Action learning – a guide for professional, management and educational development. London: Kogan Page, 1995.

McMullan M, Endacott R, Gray M, et al. Portfolios and the assessment of competence: a review of the literature. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2003;41(3):283-294.