Chapter 8 The human lifespan and its effect on selecting nursing interventions

Introduction

This chapter aims to provide an overview of the multifaceted process of development that occurs throughout a person’s life. It begins with an outline of two social sciences, psychology and sociology, with explanation of contrasting approaches to both, which recur throughout. Key topics from each subject are explored, namely motivation, culture, socialization and family. Physical development is described from conception through infancy and childhood milestones, adolescence and adulthood to old age. Psychosocial development covers the emergence of the self-concept, cognition and morality, emotional attachment and separation, aspects of sexuality and personality, and social integration. Implications of this subject matter for student nurses and nursing practice are highlighted as they arise, i.e. why it is important for all nurses to be aware of patients’ developmental issues when planning and implementing their care.

Psychology and sociology related to development and nursing

This section outlines the psychological and sociological theories, approaches, frameworks and important topics such as motivation and culture required for understanding developmental processes.

What is psychology?

Gross (2001) has described how psychologists seem to provoke three typical reactions in others. These are:

The word psychology is a composite of the Greek term psyche, which refers to the ancient view of the soul, spirit or mind, and logos, which means discourse or intellectual debate, a then-favoured method of pursuing investigation or study. Thus, in modern terms, it can be taken to mean ‘the study of the mind’, or of mental processes, and it is clearly useful for nurses to understand what is going on in a patient’s/client’s mind and the resulting consequences, i.e. patient behaviour.

The father of psychology is usually identified as Wilhelm Wundt who, in 1879, initiated scientific research into the mind. Wundt aimed to study perceptual discrimination of sensory input, e.g. vision under controlled conditions, and so develop an understanding of what he termed the ‘elements of consciousness’, building blocks of the mind. He felt able to investigate discernible differences in intensity and quality of stimuli, and so begin to describe the structure of the human mind – termed the ‘structuralist’ approach to psychology.

William James likened Wundt’s method to trying to understand a house by contemplating its individual bricks, and considered that the ‘whole’ mind as an integrated entity was of more significance than the sum of its parts, inspiring the Gestalt viewpoint, which gained currency from the 1920s. James was more interested in what the mind could do and what it is for, i.e. the ‘functionalist’ approach. This focuses on studying thoughts and emotions, and how they help people to survive in their envir-onment. From these early origins, this hybrid discipline branched into at least three distinct schools or approaches – psychodynamic, behaviourist and humanistic.

Psychodynamic approach (see pp. 212, 214 and 218)

This stemmed from the publications of Sigmund Freud from the 1890s onwards. Essentially, this emphasized the importance of unconscious processes in emotions and behaviours. Freud developed a therapeutic approach called ‘psychoanalysis’, designed to gain access to the unconscious mind using means such as hypnosis, tranquillizing medication and dream analysis.

Behaviourist approach

By the early 1900s, American academics such as J.B. Watson had become increasingly critical of the subjective methods used by Freud and Wundt. They argued that mental events were inaccessible to and therefore inappropriate for scientific investigation. It was argued that psychologists should concentrate on dispassionately and accurately observing outward behaviour, for example responses to experimentally controlled stimuli. Much of the behaviourists’ focus was on studies of animal learning, which they viewed as taking two forms:

This approach assumed the validity of comparisons between humans and animals, and that environmental factors can and could be used to determine or ‘shape’ an individual’s behaviour, just as animals can be trained to perform skills beyond their normal repertoire. Psychologists could thus devise methods of engineering people’s behaviour in ‘desirable’ directions by means of ‘conditioning’ programmes. Behaviourism held sway in psychology until after World War 2, when its emphasis on animal observation and scientific rigour began to be questioned.

Humanistic approach

A new school of psychologists, including Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers, then emerged as a ‘third force’ in this subject. The humanists focused on aspects of purely human experience, such as free will and self-fulfilment. Their methods of enquiry were subjective and person-centred, such as interview and self-report. Offshoots included therapeutic self-help groups and learner-directed educational approaches. Humanism emphasizes the positive potential in people and the importance of fostering appropriate individual choices in maximizing each person’s well-being and life satisfaction.

Applying psychological approaches to health

The three approaches can be exemplified with reference to a health issue such as smoking, as follows.

Motivation

Motivation is the underlying cause of actions. Without it people would be inert and not function. It provides individuals with the stamina and focus required to perform their activities.

Essentially then, motivation is used to explain behaviour. Without apparent explanation, behaviour may appear to be fruitless, perplexing or dangerously unpredictable. Nurses need to understand what happens in their environment, including the actions of others, not only to be able to predict eventualities but also to plan their own behaviour and interventions appropriately. Box 8.1 provides an opportunity to consider the motiv-ation to become a nurse.

Motivation to become a nurse

Think about your reasons for becoming a nurse. It may be useful to compare your reasons with those of colleagues, and note any that are different from your own.

Student activities

The ‘instincts’ theory of motivation

Early psychologists studied animals and compared their behaviour with that of humans, who were viewed as the most evolved and complex members of the animal kingdom.

Consider the question, ‘What makes cats hunt, birds sing and monkeys climb?’ The usual response is their respective ‘instincts’. The next question to address is, ‘What is meant by the term instinct?’ A reasonable answer might be a complex, unlearned behaviour pattern, i.e. more than a single reflex, specific to a species, which is elicited by a specific stimulus or ‘releaser’, e.g. a mouse appearing in front of a cat. The word derives from the Greek to ‘impel’ or ‘instigate’.

‘Acting on instinct’ is often used to describe automatic behaviour, such as using touch to comfort a distressed patient. However, many consider that there are no evident instincts in humans, as it can be argued that even seemingly natural characteristics such as associating with others, sexual desire, masculine aggression, parenting and intuition all involve some process of learning and are not always present.

Early attempts by William McDougall to explain all human behaviour in terms of instincts foundered on two problems. Firstly, because of the complexity and variability of human behaviour, his approach with 800 separate instincts was unconvincing in explaining why humans differ from each other so widely in preferences and responses, as only some humans hunt, sing and climb, and very few enjoy all three. Second, this approach was criticized for its lack of explanatory value, because it led to a circular argument. The question, ‘What makes humans act in certain ways?’ would prompt the answer ‘instincts’. To the follow-up query, ‘What are instincts?’, MacDougall’s response might have been ‘things we naturally possess that make us act in those ways’.

Freud proposed that just two instincts motivated behaviour:

Behaviourist theories of motivation

In the 1950s, Lorenz demonstrated that newly hatched goslings follow the first large moving object, whether either himself or an inanimate figure that they are exposed to in a critical period during their early days of life – thought to be an instinctive releaser normally allowing them to be led to the relative safety of water. Subsequently they were described as behaviourally attached to or ‘imprinted on’ this initial figure as their particular, if experimentally odd, ‘Mother Goose’.

It is possible to suggest examples of critical periods, releasers or imprinting in human development. For instance, there is considerable evidence that language acquisition (see Ch. 9) and ‘healthy’ personality development – socialization (pp. 194–195) and attachment (pp. 212–214) – are dependent on exposure to normal human society in the first 4 years of life. Parental feelings and caring skills may be experienced or ‘released’ for the first time after having one’s own child and, in some cases, following a parent into nursing may be considered to be an example of imprinting.

Drive theory

Clark Hull argued that all behaviour was impelled by ‘drives’, hypothetical internal states arising from ‘needs’. Figure 8.1 shows how this approach can be used to explain increased fluid intake on a hot day, essentially a homeostatic mechanism (Ch. 19).

Hull’s theory explains biological or ‘primary’ needs relating to homeostasis, such as hunger, thirst and sleep, but seems less convincing when proposing ‘secondary’ drives to explain the wider range of human pursuits, e.g. intellectual or social activities.

Nonetheless, the terms ‘drive’ or ‘driven’ are often used conversationally with regard to motivation, and Hull’s framework accords well with the experience that it is sometimes better to want or pursue something than to attain it.

Humanistic approach to motivation

Humanists believe that people are unique in possessing a rich mental life, including free choice of action, dreams and personal goals, rendering behaviourist comparisons with other species futile.

Maslow proposed a ‘hierarchy of needs’ to explain human behaviour. Although this originally comprised five levels of need, two more levels have since been added. Note that some descriptions omit levels 5 and 6 shown in the 7-level adaptation (Box 8.2). The goal at the highest tier of the hierarchy is individual fulfilment or self-actualization, but this can normally only be attained following prior satisfaction of lower levels of need. The hierarchy of needs can be represented as a pyramid with self-actualization at the apex and the physiological needs at its base (see Atkinson et al 2000).

Box 8.2 Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs

3 Love and belongingness (affiliation) needs

Giving and receiving affection; trust and acceptance of others, being part of a group

* Omitted in some descriptions.

Examples of how nurses may help patients/clients to meet needs at each level include:

Maslow’s concept of self-actualization is embodied in peak experiences, cherishable moments of ecstatic happiness when everything seems to ‘gel’ and feels right, and a person’s essential current ambition is fulfilled. He considered that all humans were capable of these, although they are usually infrequent and some may occur ‘once in a lifetime’.

There are, however, exceptions to the hierarchical structure of lower needs always being fulfilled before higher needs. It is possible to identify valid exceptions to Maslow’s order of priorities. For instance:

What is sociology?

Definitions vary, and often reveal the standpoint of the writer. Macrosociology emphasizes the study of society overall, while microsociology focuses on the interactions of individuals within it. All degrees of magnification in between these extremes are possible, for instance when studying groups within society. Health workers can be considered through the one-to-one dealings of individual nurses with their patients/clients, the functioning of ward teams or types/grades of nurses, the profession as a whole, or the entire NHS workforce.

The focus could enlarge further to cover people in Britain, Westerners or, indeed, all mankind. Sociology can therefore be defined as the study of societies, their component groups and individual interactions.

However, all sociologists would agree that people cannot be understood as individuals in a vacuum; to be human is to be social. People arise from social groups and from within society, and are part of its fabric during their lifespan. In effect, people are society, i.e. each person is equivalent to a brick within the building and society is ‘within each person’, as contact with others in society shapes each person. Because of this, nurses can only understand others and themselves by appreciating this social dimension common to all people.

Several sociologists’ views have been particularly influential over the 19th and 20th centuries; an outline is provided in Box 8.3 (see p. 190).

Box 8.3 Influential sociologists

Auguste Comte

During the 19th century the French ‘Father of Sociology’ was positive that his ‘Queen of Sciences’ would establish truths about recently urbanized, ‘industrial’ society and so be able to prescribe remedies for its human difficulties. This gave him the confidence to dub himself the ‘Great Priest of Humanity’ and his optimistic outlook has been shared by many of his successors.

Karl Marx

Marx was particularly conscious of the extreme economic inequalities within newly industrialized mid-19th century society. He predicted that the masses of employed workers – ‘the proletariat’ – would come to realize their exploitation and the need to wrest ownership of factories and land, the source of societal wealth, from their employers, the capitalist minority. The post-revolutionary sharing of society’s ‘means of production’ would inaugurate an era of classless, socialist utopia.

Max Weber

Weber modified Marx’s economic ‘conflict’ interpretation of society by focusing more narrowly and deeply on the perspectives and interactions of individuals and groups within society. For example, he noted the diversity of skills, status and aspirations within the working class, which Marx had tended to treat as a homogeneous mass. Weber also emphasized the usefulness of greater subjectivity within sociology, empathy being a prerequisite to understanding the shared meanings in human interactions – verstehen. An example of this approach would be to consider the many possible factors contributing to the anxiety experienced by a patient newly admitted to hospital.

Emile Durkheim

Comparative study between societies was Durkheim’s hallmark. He used newly accumulated data on populations, such as census information, to make deductions about the actions, thoughts and feelings of individuals. In particular he came to view suicide as a reflection of the circumstances, expectations and laws of the groups, organizations and society to which one belongs, rather than a purely private, individual act. It is only possible to understand phenomena such as ‘suicide bombings’ by taking their social context into account.

Park, Cooley and Mead

In the United States, the 19th and early 20th centuries saw huge expansion of industrial cities, which together with mass immigration led to many social problems such as crime, ghetto squalor and intergroup hostility. Robert Park and his colleagues used the city of Chicago as a laboratory for research ‘in the field’, while Charles Cooley and G.H. Mead worked on the social interactions of key significance in childhood development (see the ‘self’, pp. 204–207).

Talcott Parsons

During the 20th century Parsons formulated a comprehensive theory of society as a functioning entity, with each individual, group and organization playing its part or ‘role’ to make the system work and deriving benefits in return for their contribution. This represents an alternative macrosociological (‘big picture’) structuralist perspective or viewpoint to that of Marx on societal study, looking at society as a single, whole entity. Parson’s ‘structural functionalist’ or ‘consensus’ approach views society as a harmonious arrangement wherein people basically agree on fundamental operational principles. This enables society to operate or function effectively. Each member works to benefit society, and in return active membership benefits each member, e.g. nurses provide health care, while potential patients transport them to work or provide food for them.

Conflict approaches

These consider society as characterized by competition between antagonistic groups, each in pursuit of opposing interests. These include:

Conflict perspectives characteristically argue the need for radical revision or overthrow of society’s attitudes, institutions and general way of life.

Microsociological approach

This focuses on the individuals and groups whose daily interactions comprise society’s life, e.g. how nurses behave towards patients/clients and their colleagues, the experiences of student nurses in clinical areas or whether nursing is a ‘profession’. Such studies view people as entering social situations with pre-existing ideas about themselves, others and the situation, e.g. their relative status and expected actions, and this subjective perspective largely determines their interpersonal behaviour. Members of a society possess shared meanings in the use of symbols such as language, gestures and other non-verbal behaviour including dress, focus on which is often termed ‘symbolic interactionism’ (see Ch. 9).

Why is sociology relevant to nursing?

Consider the following quotation:

No man is an island, entire of itself … any man’s death diminishes me because I am involved in mankind; and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls, it tolls for thee.

The excerpt from this 17th century poet’s meditation compares a man’s death to a clod of earth being washed into the sea. It emphasizes how inextricably each person is bound up with other members of their society and its groups, even if the person is not conscious of this communality in their individual day-to-day pursuits and concerns. It is reminiscent of the sociobiological explanation of why people are inclined to help others – the cardinal function of nursing. Due to a common evolutionary ancestry, this argues that all humans are genetically related to each other, so that assisting others to survive helps preserve some of their own genes.

Knowledge of sociology helps nurses to understand the behaviours of patients/clients, families and colleagues. For example, a patient’s/client’s outward distress is automatically attributed to physical pain, or else fear regarding the experience or findings of an operation (Box 8.4). In other words, physical or psychological factors specific to the individual tend to be the initial assumption.

Michael

Michael is recovering from surgery, which has been technically successful. Despite having received appropriate information and nursing care to maximize his physical comfort, he remains restless, tearful and frequently demands nursing attention.

However, patients’/clients’ concerns often arise from a wider social context, such as worries about family members, employment or even care of pets. A patient/client might be more concerned about being forbidden to move heavy items at work after back surgery and the effects on their livelihood and self-worth than about any transient postoperative pain or discomfort. Health professionals rarely gain such insights from case notes or superficial encounters with the patient/client; they often emerge only when imparted in the context of a trusting relationship with the patient/client, which takes time and effort to develop (see Ch. 9).

Sociology provides insights into aspects of the nurse’s own culture and, by logical extension, into different cultures, particularly significant with the increasing cultural diversity of British society. Examples of this include the social practices specific to some members of minor-ity groups. A patient/client or their relatives may be upset or feel offended if an otherwise caring environment fails to accommodate their cultural norms such as food preferences, consultation of their spouse or prayer requirements.

This awareness can also be turned to enhancing the nurse’s self-understanding, for instance by analysis of their own social experience (Box 8.5).

Adjusting to new nursing environments

All student nurses encounter unfamiliar settings at the beginning of new placements, which can provoke anxiety.

The layout, titles and respective roles of new colleagues, in addition to the names and needs of the current patients/clients, must all be learned. The management style of the charge nurse on any day may be important, for example whether the use of first name terms is mutually acceptable and how strict time constraints are for completing tasks or meal breaks. Appropriate use of initiative has to be gauged through experience, and may be quite different for a nurse in a student role compared with their concurrent part-time or former auxiliary role, perhaps in the same environment. Understanding the dynamics of this process may help to diminish the stress of the new placement.

Sociology can also shed light on larger scale social issues, possible remedial strategies and insight into the effectiveness of these measures, e.g. by performing research and analyzing its findings (see Ch. 5). Approaches include compiling and analysing quantitative data, e.g. the incidence of teenage pregnancy, and qualitative measures such as surveying attitudes, e.g. to binge drinking or unprotected sex.

Whatever their focus and theoretical standpoint, it would be hoped that social scientists would provide insightful appraisal of social realities to at least complement those offered by religions and secular common sense.

Common sense and sociology

Nurses need to consider how sociology can enhance commonsense thinking (Box 8.6). Further discussion of sociology and commonsense is available in Further reading (e.g. Giddens 1989).

Is commonsense all we need?

Read the statements below and decide whether they are true or false.

Perhaps the best way to ensure a long life is to pick healthy parents, as longevity or brevity tends to run in families. However, although genes play a role in determining susceptibility to many diseases, environmental factors appear to contribute equally as significantly. This explains the close association between health and wealth, apparent in the significantly raised incidence of nearly all serious disease categories among the poorest sections of society (Townsend & Whitehead 1990) (see Ch. 1). Relevant factors include quality of housing, diet, occupation, leisure activities and, more controversially, healthcare provision. Thus a person’s family environment may have much more significance to health than their genes.

Regarding the second statement, most older adults retain their mental vigour with only around 5% of those over 65, and 20% of those over 80 years of age, exhibiting dementia (Alzheimer’s Society 2006). They undoubtedly represent stores of accumulated knowledge and skills, distilled into wisdom by a lifetime’s reflection on their experience. Despite this, older adults in Western society have been typically viewed as a redundant group who are an economic burden on the productive section of society. They tend to be functionally marginalized, i.e. excluded from the social mainstream in, for example, occupation and leisure, rationed in resources such as facilities and benefits, and viewed not with respect but in a derogatory manner, ranging from well-meaning pity to outright contempt, some of the many expressions of ageism.

Although education is often regarded as the key to universal achievement and equality, there is much to suggest that the Western system tends to perpetuate and cement inequalities. Middle-class children tend to achieve more and better qualifications than their working class counterparts, perhaps in part because their parents provide better preparation, encouragement and facilities, but also because they seem to relate more easily to teachers and their style of communication. This disparity is accentuated by other social factors that predominate in the working class such as early pressure to earn, widely varying facilities even within the state system and peer group behaviours. Thus children from affluent backgrounds are more likely to progress directly to full-time higher education and from there to better paid jobs, often in their parents’ professions.

Culture

Take a moment to think of what the term ‘culture’ means to you. Common responses include normal patterns of behaviour within one’s country, including eating, drinking and speech, and ‘lofty’ forms of social expression such as art, music and literature.

Culture can be defined as the way of life of a society – a group of people who share a distinct identity, often within a circumscribed locality. Components of a culture include beliefs, values and norms.

It is, however, important to remember that the components of culture typically change within a society over time, allowing it to gradually adapt to changing circumstances and evolve. An example of this is the insistence in the late 19th and early 20th century that student or ‘probationer’ nurses were all female and would attend Christian services each Sunday, stay within the nurses’ home when not on duty and leave the profession once married (see Ch. 2). This is quite different to experiences of student nurses in the 21st century.

Beliefs

These are factual ideas such as religious beliefs about whether there is one God, or more, or none. Some beliefs may involve lifestyle issues, e.g. a nutritional belief about what is good or bad to eat, or how it should be prepared, which varies hugely between societies, as does the acceptability of alcohol. Traditional cultures may revere people who see visions and hear divine voices, whereas in Western cultures a psychiatrist is likely to be consulted.

Values

These are broad guidelines for activities, conveying what principles a society deems valuable or worth preserving. In the West, freedom of speech, occupation and choice of partner is highly prized, which may conflict with values such as patriotism, equality of wealth and respect for older people, which are more esteemed in other soci-eties. Values tend to be more absolute than beliefs, i.e. are subscribed to whole-heartedly or not at all, so that optimizing ‘health’ may either govern one’s lifestyle fully or not at all. The sanctity of life, i.e. that life is precious and should not be taken intentionally, is another value central to healthcare but not to all human situations.

Norms

These are more specific behavioural expectations rele-vant to particular circumstances, equivalent to everyday ‘do’s’ and ‘don’ts’. For instance, personal greetings such as tongue protrusion are expected in Maori ceremonies but not at social gatherings in the Western world, there are occasions where polite versus familiar speech is expected, eating etiquette including table manners and fashionable attire. Conformity increases the likelihood of social acceptance and success, e.g. belching is rarely appreciated at formal dinners in the UK, and often mirrors the underpinning value, e.g. paying for goods reflects honesty or adhering to nursing advice suggests that a patient/client values health. Norms are in turn often subdivided into folkways, customs, mores and rules (Box 8.7).

Cultural universals

As well as the foregoing components, some elements of culture are common to all societies. For example language, both verbal and non-verbal, enables interpersonal communication (see Ch. 9). Mutual understanding of the spoken and written word can give members of a society a unique communal currency, especially if fluency is restricted to small populations, e.g. the Celtic tongues in the UK.

Facial expressions conveying universal emotions such as joy, sorrow, fear and surprise are recognized across cultural groups, but conventions governing the meaning of gestures and acceptable degrees of interpersonal touch and distance vary widely. Other aspects probably common to all cultures, past and present, include:

Cultural bias and relativism

Comparing the different practices and underpinning belief systems of different cultures tends to encourage people to favour those of their own society. There are many possible reasons for this bias. These include respect for those people who have nurtured them, greater famil-iarity with their own ways and boosting group self-esteem through criticizing foreign behaviours. However, in a culturally diverse society, this may lead to intergroup hostility and discrimination, resulting in unequal treatment, not least in healthcare settings. Thus it is important to remain aware of this tendency, and to try to accept these differences as indicators of the distinctiveness of a particular group rather considering whether they are better or worse than one’s own experiences. Aspects of Western culture, which might strike an outsider as different or unusual, are considered in Box 8.8.

Subcultures

Individuals within a society form groups that have their own distinctive views and practices. These variations inside a culture give rise to subcultures – effectively ‘cultures within a culture’. A common example is youth culture, as young people have typical values, beliefs and norms such as a code of conduct in relation to dress, speech and musical taste. These may vary markedly from those of older adults who comprise the influential majority and so the cultural yardstick of society. Other ‘variant’ subcultures include those of minority ethnic groups, students and healthcare professionals. Some subcultures overtly refuse to comply with existing laws in a society, and are termed ‘deviant’ subcultures, such as criminal gangs. ‘Counter-cultures’ are antagonistic towards the prevailing dominant culture, although they may not break any of its legal statutes, e.g. travelling people, self-sufficient smallholders and pacifist campaigners in the UK (Giddens 2001).

Culture shock

This is the term given to the sense of disorientation experienced when exposed to an unaccustomed culture or subculture. Varying degrees of this occur when on holiday abroad, when entering a new workplace or setting (Box 8.9). Admission to hospital or to a care home may provoke anxiety. The possible stressors (see Ch. 11) associated with the hospital/care home subculture might include:

Culture shock

Think about a time when you became part of a new subculture, for example starting a new school, meeting your partner’s family or starting your nursing course.

Student activities

Culture and healthcare (see Ch. 1)

A profound interconnection exists between these two. People from different cultures may have conflicting ideas about what constitutes health or illness, for example the diagnostic criteria for mental health problems such as schizophrenia differ enormously between Western and Eastern perspectives, and studies have shown wide cultural variations regarding pain tolerance (see Ch. 23), risk-taking behaviours, e.g. use of cannabis by Rastafarians, and unsafe sexual behaviours and the spread of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in sub-Saharan Africa.

Nurses have to be sensitive to the cultural expectations of individual patients/clients and families, without making stereotypical assumptions, if they are to deliver holistic care (Box 8.10). This may involve aspects that include:

Cultural awareness in nursing practice

You are helping the registered nurse (RN) to admit a client who is anxious about being admitted to the unit. The RN asks the client for his Christian name and is surprised when he challenges her by saying that he is Muslim.

Student activities

[Resource: BBC (Religion and Ethics) – www.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/people/features/world_religions/index.shtml Available July 2006]

Socialization

This is the process whereby a society transmits its culture (or group its subculture) to its future members. As a result, individuals acquire the knowledge and skills that allow them to function socially, leading to personal and communal success. Socialization is usually described in two phases: primary and secondary (Box 8.11).

Personal experience of socialization

Think back to an episode when you learned something from a parent or person close to you, from the mass media and from a RN while on placement.

Student activities

Note: You may find that feelings significantly colour such recollections. As socialization is an interpersonal process, it often imparts learning in a profound and emotional manner.

Socialization is a two-way process throughout, with the novice challenging the ‘mentor’ by asking questions and proposing alternatives, so that becoming a parent involves learning from interactions with one’s children, and the same give-and-take occurs during grandparenting.

Primary socialization

This occurs in early childhood, and the main ‘agents’ are usually close family members. The preschool child acquires fundamental skills relating to interaction with others including speech, gesture and appropriate behaviour, and self-care, e.g. continence, dressing, feeding. In addition, attitudes including moral and religious beliefs are transmitted. On occasions, teaching can be formal, or deliberate, such as instruction on tying shoelaces. At other times, it may be imparted unconsciously, or informally, as when a child overhears their parent’s private opinion about something. Because of the initial and personal nature of this process, primary socialization often carries profound emotional undertones, and may cement lifelong memories and bonds.

Secondary socialization

This refers to cultural transmission that occurs from entering school, and continues throughout life. It equips the growing person to survive and prosper outwith the family environment; its agents include teachers, peers (equals such as friends and fellow students), work supervisors and colleagues, and the mass media, e.g. authors, journalists and broadcasters.

The term tertiary or ‘professional’ socialization (see p. 207) is sometimes used in relation to the acquisition of knowledge, skills and attitudes required in performing high-level occupations such as nursing.

Roles

Functionalist sociology pictures socialization as gearing individuals to fulfil roles, which are social positions involving expected behaviours. Each person typically performs several roles, usually focusing on one at a time, including some that are:

It can be seen that many roles have reciprocal partners, in that one to some extent defines the other, so that it is hard to imagine the traditional role of nurse or doctor without someone filling the role of patient/client.

Each role can be viewed as beneficial to other members of society but also to the performer; although every role has its duties or obligations, it also confers rights and privileges if carried out adequately (Box 8.12).

Thus society can be viewed as a symbiotic community, each role-bearer contributing to its smooth running, and in turn receiving rewards such as healthcare when sick. Parsons extended this framework to formulate the ‘sick role’, which people could legitimately adopt when ill, as in such circumstances they could not fully perform their normal roles (see Ch. 1). As with all roles, this conferred rights and privileges, provided the sick person fulfilled certain duties and obligations.

Role conflict

Fulfilling several roles can be a tricky balancing act and sometimes ‘role conflict’ is inevitable. It occurs where the demands of fulfilling one role impairs the performance of another, such as family commitments undermining focus on study or nursing duties (Box 8.13, p. 196).

Potential role conflict

Student Nurse Sarah has two children of school age. Her husband is in full-time employment, and Sarah works as a care assistant two days a week to supplement the family income.

Often domestic commitments detract from energy and available time for family relationships, study and other work. Caring for dependent older relatives can also have a significant impact on a person’s own parenting, work and personal life.

The family

A person’s understanding of the term ‘family’ pervades the way in which they view the world. This is evident in the use of terms such as ‘Father Time’ and ‘Mother Earth’. Political parties vie to be the ‘party of the family’ and espouse ‘family values’, and the family is often regarded as the basic unit, or even a microcosm of society (Box 8.14).

What ‘family’ means

Although a term used in everyday speech, it is not easy to agree on a universally acceptable or concise definition of ‘family’.

The term ‘family’ means different things to different people, but the common associations it raises are emotions such as love and affection, or possibly mixed or negative ones, personal closeness, intimacy and shared experiences, communal housing, financial support, advice, the roles mentioned earlier and caring for one another.

Although people can have different family experiences, a general definition is ‘a group of people, bound by kinship ties, who live together, share resources and who look after each other in times of need’. All societies have some form of family unit that performs – although some would say controls – essential functions including the reproduction, economics and socialization of its members.

Family structures

Family structures vary widely both between and within cultures. Common variants include:

In addition to its universality and pivotal position in society, the family has received much consideration as either an integral part of healthcare provision or a contributing factor to many physical and mental health problems.

There are many ways in which the family may be significant for an individual’s health and healthcare, both positively and negatively. These include transmitting ‘healthy genes’ or those producing abnormal conditions; providing the emotional climate surrounding child-rearing and adult interactions, e.g. loving care or forms of abuse. Communication patterns may be supportive or disruptive to mental health, and family income is usually crucial in determining material comfort. Links between wealth and health are well documented (Ch. 1); lifestyle choices such as diet, smoking and exercise are often influenced by domestic attitudes. Close relatives may be understanding of, or intolerant of, certain conditions, e.g. learning disabilities, mental health problems, substance misuse or HIV infection. Family dynamics may involve either mutual devotion to or guilt at not shouldering the burden of a family member’s care needs. Relatives may also disagree with care decisions, e.g. prolonging active treatment or disclosing poor prognosis, and place great value on customs required for a loved one’s care or treatment (Denny & Earle 2005).

As with individuals and the culture in which they exist, the family does not remain static but continuously evolves to adapt to changing pressures and circumstances. In many ways it represents a mirror of society at any given time, reflecting its development, limitations and current challenges, its successes and its shortcomings.

Trends in family structures

Considerable changes in family structure have taken place over the last few decades.

Some examples of these trends, as suggested by Abercrombie and Warde (2005), and which do not necessarily apply to all social groups or countries, include the following:

Development across the lifespan

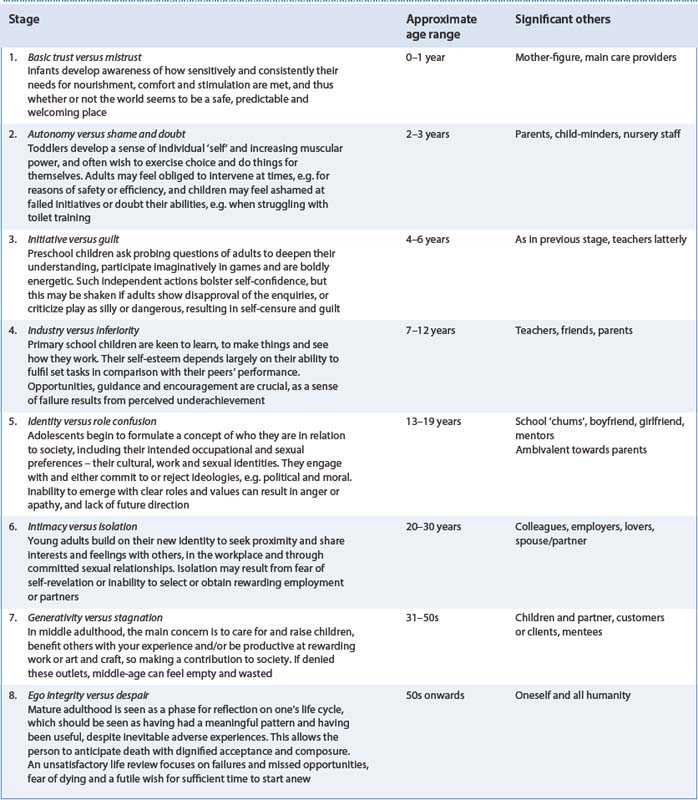

As late as Victorian times, children were viewed as small adults, pre-programmed for adult knowledge and behaviour to emerge with passing years. This view, which implies the importance of natural growth in physical size and strength, changed with greater awareness of child exploitation and misery, e.g. in the novels of Charles Dickens. Protective legislation began to confer rights on children, such as education. Prior to 1833, under nines could work up to 12 hours a day in factories. Only after the Education Act of 1870 did attendance at school become compulsory for most children until age 13 in the UK; the leaving age became 15 only after World War 2 and 16 years in 1972. Another factor in reappraising childhood was the increasing scientific interest in the process of adaptation that followed Darwin’s publications on evolution. From the early 1900s, much enquiry focused on how the individual’s concept of ‘self’ was formed, parallel with Freud’s contemporary ideas on unconscious processes being formative in adult sexual and personality patterns. The latter was to inspire Erikson’s model of a person integrating socially through their resolution of a series of ‘personal crises’. The middle part of the 20th century saw much investigation of how cognitive, moral and emotional maturity is acquired, such as through the work of Piaget, Kohlberg and Bowlby.

This section outlines the important stages of physical and psychosocial development throughout the lifespan. Factors affecting development and their potential signi-ficance to health are briefly considered. Developmental milestones from birth to school age are introduced, and the Denver II (1990), a developmental screening test (previously known as the DDST), is included (pp. 202–203). Detailed discussion of the developmental milestones is beyond the scope of this book and readers requiring more information should consult Further reading (e.g. Hockenberry et al 2002).

Physical development

This section outlines how the body grows and develops before birth and then through the stages commonly identified thereafter, namely infancy, childhood, adolescence, adulthood, middle and old age. Chapter 14 provides further information about monitoring children’s growth in height and weight gain.

Various hormones influence growth and development throughout the lifespan, such as those that stimulate growth during infancy and those that initiate the events of puberty. Some examples are outlined in Table 8.1 (see p. 198).

Table 8.1 Hormones affecting growth and development (after Hinchliff et al 1996)

| Hormone | Source | Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Growth hormone (GH) | Anterior pituitary gland | Stimulates growth in many tissues, e.g. bone and skeletal muscle |

| Stimulates protein synthesis | ||

| Cell growth and repair | ||

| Thyroid hormones | Thyroid gland | Needed for normal development of central nervous system |

| Deficiency during early childhood results in small stature and impaired mental development and learning disability | ||

| Parathyroid hormone with vitamin D and the hormone calcitonin secreted by the thyroid gland | Parathyroid glands | Bone growth and formation |

| Insulin | Pancreas | Glucose uptake |

| Inhibits protein breakdown and stimulates protein synthesis | ||

| Glucagon | Pancreas | Glucose usage |

| Rapid rise in blood glucose level | ||

| Glucocorticoids, e.g. cortisol (see also Ch. 11) | Adrenal glands (cortex) | Regulates tissue growth |

| Excess during periods of growth inhibits growth in height | ||

| Oestrogen | Ovaries | Female secondary sexual characteristics |

| Female body fat distribution | ||

| Bone density | ||

| Testosterone | Testes | Male secondary sexual characteristics |

| Widespread anabolic effects on many body (somatic) tissues to produce male physique |

Conception to birth

Almost every month following the establishment of menstrual cycles during puberty until the menopause (cessation of menstrual cycles), a non-pregnant woman ovulates or releases usually a single oocyte, or egg, from one of two ovaries. However, the frequency of ovulation decreases some years before the menopause. The oocyte enters the uterine tube, where it may be fertilized by one of the millions of spermatozoa or sperm deposited into the vagina by her sexual partner. The nucleus of the oocyte and that of the spermatozoon (the gametes) each has 23 chromosomes (the genetic material), so that when they merge forming a zygote at conception or fertilization, the normal human complement of 46 chromosomes per cell is usually restored. Thus an individual receives half of their genes from each of their parents.

After 24–36 hours, the first cell division occurs, and mitosis continues rapidly. Within 3 days a cluster of cells is formed, about the size of a pinhead. During the second week, the cluster of developing cells implants into the specially prepared lining of the uterus known as the decidua, which will provide nourishment until the development of the placenta. The term embryo is used from the early developmental stages until the eighth week of pregnancy (gestation). Thereafter, until birth it is known as a fetus.

The cluster of cells continues to develop and will eventually differentiate into all the specialized cells of the human body. Occurring alongside these events are the processes that result in the formation of two protec-tive membranes, the chorion and amnion that enclose the embryo/fetus, the umbilical cord and the placenta. The amnion contains the amniotic fluid in which the developing fetus floats throughout pregnancy. The placenta, which has close contact with maternal blood vessels in the uterus, delivers oxygen and nutrients to and removes waste from the fetus through blood vessels in the umbil-ical cord via the adapted fetal circulation of vessels and shunts that mostly bypasses the lungs and gastro-intestinal tract. These adaptations are normally reversed soon after birth.

During the early weeks after implantation, all the organ systems start to develop, so that a heart beat, lungs and limbs are detectable within 4 weeks, and the eyes, ears, nose and mouth as well as rudimentary digits can be visualized after 8 weeks of pregnancy. At this early stage, the embryo is particularly vulnerable to adverse factors such as toxins and microorganisms, and these may have major effects on developing organs, e.g. the rubella virus may cause heart defects and deafness.

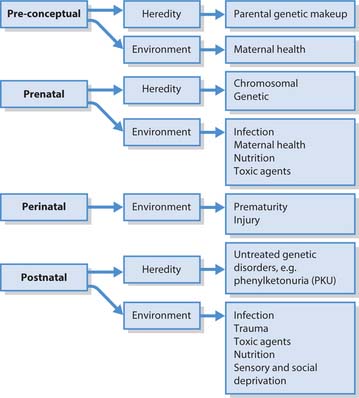

There are many possible causes of learning disabilities, either genetic (hereditary) or environmental (Fig. 8.2), which can occur during different stages of development. These include:

Down’s syndrome

A friend and her partner are planning to have a baby and she asks you what causes Down’s syndrome and the risk of having a baby with Down’s syndrome. She also asks what diagnostic tests are available during pregnancy.

Student activities

[Resources: Down’s Syndrome Association – www.downs-syndrome.org.uk; Down’s Syndrome Scotland – www.dsscotland.org.uk; UK National Screening Committee: Down’s Syndrome Screening Programme NHS – www.screening.nhs.uk/downs/home.htm All available July 2006]

From the end of the second month to the end of pregnancy (usually 40 weeks) the fetus grows from 2.5 cm in length and 7 g in weight to around 50 cm and over 3500 g. Sex can be ascertained after 3 months, while development of the brain, lungs and heart make viability possible from about 24 weeks of gestation (Bee & Boyd 2004). Detailed information about fetal development can be found in Further reading (e.g. Chamley et al 2005).

Infancy (0–12 months) (see also ‘Developmental milestones’, pp. 201–203)

Although infants typically lose some weight in the days immediately following birth, once feeding and digestive processes are established, growth is extremely rapid, with up to 0.5 kg being gained per week, so that birth weight is doubled on average by the age of 18 weeks. Similarly, an infant can increase in length by 1 cm over a single week during this stage.

The first teeth start to erupt around 6 months of age (see Ch. 16); a delay in the eruption of teeth may be an indicator of other developmental problems.

Motor strength and coordination also steadily advance during infancy. The head is disproportionately large, and requires a steadying hand to support it in the neonatal period (first 28 days). However, by 8–12 weeks, the infant’s neck muscles are able to prevent the head lolling backwards, and by 9–12 months the infant can sit and latterly stand unaided.

Mobility also increases: by 3–6 months, the infant should be able to roll over, crawl by 6–9 months and some infants can walk well by 12 months.

Childhood (1–10 years)

The rate of growth slows, but by the age of 2–3 years, children attain half their adult height, although less than one-fifth of their healthy adult weight.

During the preschool period, up to 5 years of age, there are continuing increases in size and strength, accompanied by apparently boundless energy, and punctuated by the appearance of skilled behaviours such as doing up buttons (see also ‘Developmental milestones’, pp. 201–203).

For further detail of growth during childhood the reader is referred to Further reading (e.g. Montague et al 2005).

Adolescence (11–18 years)

During adolescence, the period between the onset of puberty and adulthood, further growth spurts are stimu-lated by the sex hormones oestrogen and testosterone (see Table 8.1). These episodes of sudden growth may pose challenges in relation to coordination of a typically gangling frame. At the same time, self-consciousness is further increased by the appearance of secondary sexual characteristics (Box 8.16) with inherent and unavoidable challenges to self-image (see p. 201).

Younger adulthood (18–40 years)

Early in this stage, most people reach their maximum height, because the epiphyseal plates (cartilage) of long bones become bone (ossify), thus preventing further growth in stature. However, growth in height may cease earlier in young women. It is important to maximize bone density during the teens and twenties (Box 8.17, p. 200). Bone mass peaks during the late twenties but after 35–40 years of age it starts to decline. Not only are individuals now at their peak of skeletal muscle bulk and physical strength, speed and athletic potential, but the cardiovascular system also possesses its maximum oxygen-carrying capacity and immune responses are at their peak, so that young adults recover quickly from exercise, injury and illness. Brain mass and sensory powers are similarly at their highest point, resulting in optimal ability to discriminate stimuli.

Eating disorders and bone density

Eating disorders such as anorexia and bulimia nervosa can have far-reaching consequences for bone health. Apart from an inadequate intake of the nutrients needed for bone growth and density (e.g. calcium, vitamin D, protein, etc.), there are other issues for young women with eating disorders. Those with a very low body weight may stop having periods and the lack of oestrogen puts them at risk of loss of bone density, which may never be rectified even if they gain weight and their periods return. This may also occur when young women exercise excessively with or without an eating disorder. Loss of bone density or a failure to reach peak density increases the risk of osteoporosis (see Ch. 18).

[Resource: National Osteoporosis Society – www.nos.org.uk Available July 2006]

The middle years (40–65 years)

Most adults in Western society can currently look forward to living well into their seventies or eighties, owing to reduced mortality from disease, occupational accidents, etc. compared with past generations (see Ch. 1). By the mid-forties there are usually detectable, but not serious, signs of decline in all body systems (Box 8.18).

Box 8.18 Changes in body systems in middle years

The integumentary system

The senses

Cardiovascular and respiratory systems

Body weight in middle years

The reproductive system

Even into their fifties, however, many people consider themselves healthy and if no longer in their physical prime, not far short of their best in terms of intellectual and social functioning – their ‘prime of life’.

Older adulthood

Beyond the relative physical and functional plateau that extends from young adulthood to middle-age, individuals must progressively adapt to the more obvious changes that accompany ageing, often exaggerations of those which start to appear in the middle years.

As indicated by Mader (2000), physical aspects include:

Functional aspects typically include more troublesome reductions in:

However, although the incidence of illness and disability does increase with age, most older people, especially those under 75 years, are healthy and independent. They retain their mental faculties and continue to enjoy life, especially if they can reconcile themselves to adapting to their relative limitations. Although the proportion of older people in Western society is increasing, health-related factors such as diet, housing, technological and medical advances may allow their prospects to be brighter than for previous generations.

Developmental milestones

Human development is often thought of as a process involving the achievement of competencies or ‘milestones’, i.e. the ability to perform tasks that society expects of its members at a given point of their lives. Such competencies are progressively acquired during physical mat-uration (increasing age, size, strength and coordination) and through opportunities for practice. Development is therefore viewed as a complex interplay of biological, environmental and social factors.

The usual way of assessing an infant’s/child’s developmental progress is to compare their behaviours with those displayed by the majority of their contemporaries. Following detailed studies, abilities have been organized into comparative grids, for example the Denver II (1990) (Fig. 8.3), which divides infant’s/children’s milestones into four categories:

Fig. 8.3 The Denver II (1990) Developmental rating scale.

Copyright 1969, 1989, 1990. WK Frankenburg and JB Dodds; copyright 1978 WK Frankenburg (reproduced by kind permission of Denver Developmental Materials Inc.)

Cross-comparison can establish whether a particular infant/child has attained a series of milestones established as typical for their age. This is a matter of concern to many parents, but it should be appreciated that compiling ‘average’ scores involves rating some children as showing behaviour relatively early or late. Significance is only really attached to this if all related behaviours or overall progress follows the same pattern. Additionally, it is common for children to be advanced in some abilities and delayed in others, and for boys and girls to develop at slightly different rates (Box 8.19, p. 204).

Developmental assessment

In order to detect problems at an early stage, it is important to assess the progress of infants and children in attaining certain milestones, such as smiling or building a tower of bricks.

Student activities

Psychosocial development

This refers to the psychological and sociological perspectives on the process of development. The stages are considered by age group.

Infancy and childhood

The main issues relating to infancy are considered under self-concept and attachment below.

Early in childhood, preschool milestones must be attained, a process that may in some instances occur naturally, but in others such milestones are awaited anxiously and require greater facilitation. By the age of 5, children are required to attend school, mix with peers and accept direction from unrelated adults (see ‘Socialization’, p. 195), an experience that can initially prove traumatic.

As mentioned above, young children possess enormous energy (to be expended in a shorter day than their parents’/carers’ reserves) as well as steadily increasing bodily strength and frame size. Awareness of this potential power, constrained by restrictions imposed by adults and accentuated by intense emotions, can lead to behavioural problems. These range from the tantrums of the ‘terrible twos’ to destructive rages, scuffles and vandalism in school years. Such features can be pronounced in the behaviour of some young people with learning disabilities, whose psychological resources may be overstretched at times by the demands of normalization, i.e. adapting to the myriad stresses of life lived within mainstream society. In these situations it is important that parents/carers consider what is being communicated or how the environment can be adapted.

Adolescence

The physical changes during puberty generate psychosocial challenges for the adolescent, who must come to terms with new experiences, including:

All this is accompanied by concurrent cognitive, e.g. scholastic, and ethical developments that will be con-sidered later. Teenagers tend to be acutely aware of their bodily appearance and hygiene (taking much time over self-care), and concerned about issues of modesty and privacy, relevant to those nursing them. By the late teenage years many individuals have reached their highpoint in terms of physical suppleness, speed and reproductive ability, but outlets for these may be limited and external constraints resented.

Young adulthood

This phase is usually considered to begin around 20 years of age, although attainment of adulthood may be culturally defined in various ways, for example:

The nervous system functions at its peak, resulting in optimal ability to detect and memorize information, and to solve problems. Physical attractiveness is often regarded as most striking at this time. Consequently, self-confidence may simultaneously expand. While each of these attributes may gradually diminish from the age of 26 onwards, factors such as experience, reasoning ability and motivation may more than compensate.

The middle years

A common psychological challenge for women in their mid-forties to fifties is the ‘empty nest syndrome’, having to adjust to their children entering young adulthood and leaving home. This can prompt women to re-enter the labour market or restart their career, which, not uncommonly, coincides with marital separation or divorce. Career opportunities can, however, be offset by the need to provide care for older relatives. Childless women also come to the realization that they are now unlikely to have a child.

Male awareness of sexual difficulties, occupational and relationship stagnation, perhaps compared with their spouse’s new lease of life, and of approaching mortality can combine to precipitate the ‘male menopause’, either expressed in introverted self-doubt or the purchase of a Harley–Davidson motorcycle.

Older adulthood

Psychological aspects of old age are well documented (Gross 2001). These may include diminished ability to solve new problems, memorize and retrieve information. As all of the above changes seem to be negative and relate to loss, perhaps it is unsurprising that depression is relatively common in older adults, and the prospect of ageing may be ignored, dreaded or defused through humour.

Retirement can also be a rewarding period where the person has more time to devote to relationships, e.g. with partners, children, grandchildren and friends, hobbies and part-time or voluntary work. Lifestyles associated with contentment in old age vary between authorities, for instance the contrast between ‘disengagement’ and ‘activity’ models (Gross 2001).

The ‘self’ and ‘self-concept’

These terms are often used interchangeably when examining how people think about themselves, and consider their own nature and actions. This process is also referred to as ‘self-awareness’ or ‘self-consciousness’. It might be viewed as a straightforward, natural part of a person’s existence, but the ‘self’ is a complex notion, unique to human beings, which they have to develop and continuously modify throughout their lives. It involves forming the ability to take the role of subject and object, observer and observed, at the same time. Self-consciousness is particularly intense when a person is especially aware of being viewed as an object, for example suddenly finding themselves in front of a group of ‘spectators’, such as when arriving late for a class (Box 8.20).

Possible instances might include:

The self can be conceived as comprising three interrelated elements: self-image, self-esteem and ideal self.

Self-image

The first of these is effectively the impression people hold of them, and includes how they think that they appear outwardly to others and the kind of person that they believe they are (Box 8.21).

The TST

One way of investigating a person’s self-image would be to ask people to describe themselves. Kuhn and McPartland in their ‘twenty statements test’ (TST) used this approach in 1954.

Personality traits

These are adjectives that allow people to subjectively describe their mental processes such as thoughts and feelings, or their behaviour. Examples might include ‘I am… kind, caring, practical, hard working, which are all good characteristics for a nurse, outgoing or shy. Sometimes these can be grouped to form a so-called personality ‘type’, for example traits such as ‘shy and retiring’, ‘thoughtful’, ‘serious’ and ‘cautious’ may combine to constitute an introvert, contrasting descriptions such as ‘sociable’, ‘lively’, ‘fun-loving’ and ‘impulsive’ relating to the opposite extrovert type (Eysenck 2000). Eysenck (senior)’s, other main distinctions were between:

Trait and type approaches to self-description are commonly used in everyday language as well as in psychological research, and imply that aspects of the self are relatively fixed once established, and can be compared and contrasted between individuals, e.g. colleagues or clients.

Roles (see pp. 195–196)

Such answers may include familial roles such as ‘mother’, ‘daughter’, ‘aunt’ or ‘sister’, or occupational ones such as ‘student’, ‘nurse’ or ‘doctor’. Also common may be statements of religious identity, e.g. ‘I am a ‘Christian’ or ‘Muslim’.

Factual

Factual matters include gender, marital status and age (perhaps commoner if the respondent is towards the extremes of lifespan). Literal answers are characteristic of younger age groups, for instance children under 8 years tend to answer the TST in terms of activities, e.g. ‘I am playing’, ‘… at school’, or even ‘… talking to you!’ Between 8 years and adolescence, answers usually revolve around facts such as their:

(Miell 1990).

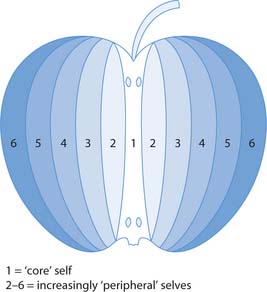

The relative importance of a person’s TST answers can be gauged by asking them to rank each in order of importance. This then enables the construction of a concentric model of the self-image (Fig. 8.4), with the central one representing the most important self-descriptor and the true ‘core- self’, compared with the progressively less important ‘peripheral- selves’ outside this.

Physical characteristics, such as size or appearance, form part of the ‘bodily self’, or ‘body image’, and may appear in response to the TST if perceived to be a particularly significant part of the outward self. The bodily self also includes sensations such as hunger, thirst, satiety, warmth, cold, pleasure and pain – common preoccupations during ill-health, and which help to direct conscious awareness towards survival-related actions. It also covers anatomical components (body structure), which might be automatically regarded as an, or indeed the essential part of people’s living selves, although they lose parts of it without concern, as when cutting their hair and nails. Possession of bodily parts or even fluids can be an ambiva-lent matter, e.g. when considering donating or receiving organs or blood.

However, there will be circumstances where an adolescent or adult patient/client would particularly fixate on the bodily self when responding to the TST. For example, chronic pain, preoccupation with weight in anorexia nervosa or obesity, disfiguring burns, paralysis, loss of continence, breast removal or stoma-forming surgery, and depression may engender self-loathing.

Self-esteem

The ability to evaluate their self-image leads people to examine the second component of the self – their ‘self-esteem’. This is how people feel about the image they hold of themselves, the degree to which it pleases or displeases them, and whether they take pride in or feel shame towards it. Thus people can run a range of emotions when appraising themselves, from conceit to despair with all points between these extremes, and these judgements vary with time, their behaviour and circumstances. This self-evaluation may be directed at specific aspects of the self, for instance appearance, thoughts about issues or other people, emotions such as desires, or actions that have been performed. Alternatively, it may be a ‘global’ amalgamation of such detailed appraisals, generating an overall estimation of self-value at a given moment.

Self-esteem is enormously influenced by the culture to which people belong. Western culture is often said to value material wealth and individual attainment. Thus an individual member of this society is likely to have their self-esteem bolstered by financial security, ownership of impressive clothes, house and car, academic qualifications and a high status job, many of which can be contingent on each other. Absence of such indicators of personal success is liable to lower a person’s self-esteem, unless they belong to a non-materialistic subculture, e.g. a religious organization or an anti-capitalist protest group, from which they may derive a quite different yardstick of personal worth.

Self-esteem clearly has a major bearing on emotional well-being and so is integral to personal happiness. If people aim to be personally fulfilled and happy, this seems to imply a potentially aspirational element to the self-concept. If self-image represents the ‘person’ that people consider themselves to be, sometimes termed the ‘actual self’, it may not be all they would like to be or could be. The wished-for improved version was termed the ‘ideal self’ by Rogers (see p. 184). Another way of tackling the problem of lowered self-esteem is to avoid exacerbating factors. People often evaluate their self-image by comparing themselves with others. If inappropriately successful figures are chosen for reference purposes, it is likely that disappointment will ensue, for example, comparing one’s physical attractiveness with that of a film star or one’s material success with a millionaire. Similarly, a student nurse is liable to feel inferior in poise and skills to an experienced registered nurse.

William James suggested a formula akin to:

In other words, the higher their expectations, the more likely they are to exceed the person’s achievements, and the likelier they are to be disappointed. This indicates some need to be realistic in personal targets, e.g. the goals negotiated with a patient/client for their rehabilitation, although equally it could be argued that without aspirations people are unlikely to improve themselves or achieve anything significant in their lives. Rearranging the formula gives:

Therefore, harbouring high self-regard and goals is likely to make people more successful, so that a positive view of the present and future self may be conducive to generating good fortune, e.g. in a student’s nursing career aims.

Development of the self

As people are not born with an intact, innate self-concept, how is it formed? Piaget (p. 207) proposed that the infant below the age of 6 months is egocentric or self-centred in that they are unaware that a world separate from themselves actually exists. It takes at least a further year to create an understanding of the reality of the surrounding environment, including the people within it. Work on object permanence (see p. 208) suggests that young children only develop a consistent interest in (which implies a concept of) absent things and people, i.e. the ‘not self’, by about 18 months. Furthermore, research by Lewis and Brooks-Gunn in the late 1970s suggested that only above this age do children recognize their own image, for instance in a photograph or their reflection in a mirror, as distinct from images of other children of the same age.

This work followed up findings by Gallup in the early 1970s on primates, which found that only higher apes seemed able to develop similar self-recognition, and only then if they had been exposed previously and early in life to other members of their own species. This usually occurs naturally, and seems essential to future social functioning such as mating and parenting (see attachment, pp. 212–214). On the basis of his results, Gallup asserted that the self is ‘a social structure, and arises through social experience’. In other words, humans at least begin to form their self-image through being reared by other humans, and gradually recognize their form as similar to those of the children and adults they see around them, until they can conceive their own physical boundaries and appearance towards the end of their second year of life.

From early infancy, children naturally interact with those around them, initially exchanging gaze and facial expressions like smiling with their mother, then during their second year beginning to use recognizable words of their ‘mother tongue’. Such symbols, along with gestures such as waving, provide the means of communicating shared meanings during interpersonal interactions, the basis for what is termed the ‘social interactionist’ perspective, initiated by George Herbert Mead in the 1930s. Mead developed the observations made in the 1890s by William James on the linguistic distinction between the terms ‘I’ and ‘me’ – both in this context sometimes given the prefix ‘the’. The first-person pronoun ‘I’ is used to denote the self as the subject of the act of thought, speech or behaviour. James likened this to a knowing but hidden observer, almost like an ever-alert motion camera, placed within what he termed a person’s ‘stream of consciousness’. This ‘I’ might be equivalent to the essential ‘core- self’ referred to earlier, a secret entity in some ways, unattainable even to its owner.

On the other hand, the pronoun ‘me’ refers to the self when viewed or treated as an object, and amounts to what in a person is outwardly observable, such as their physical appearance, clothes (e.g. when you ask another person whether a new coat is ‘me’ or ‘not me’), overt behaviour and even reputation. This use of ‘me’ in speech has already been noted in relation to the bodily image, and its evaluation is much affected by social influences such as the perceived or anticipated opinions of others. Thus the ‘me’ may be modified in order to maximize one’s self-esteem, and it is the ‘I’ in this framework that makes these judgements and decisions.

Although fully understanding the social interactionist argument with its peculiar linguistic interrelations is challenging, it suggests that once consistently mastering the use of the terms ‘I’ and ‘me’, the child must be displaying awareness of the parallel existence of both ‘self’ and others, and how their standpoint and those of other people interacts.

As well as through the acquisition of language skills, Mead contended that the self-concept developed by means of assuming roles. He described three stages of his own conception of ‘primary socialization’ (see p. 195) during which this occurred. In the initial preparatory stage, the young child can be seen closely imitating parental actions, such as washing dishes and vacuum cleaning. At this time, the child is very sensitive to parental feedback, whether encouraging or disapproving, and internalizes their judgements (Miell 1990).

In the second stage, play often involves the re-enactment of adult behaviour when the child is alone, frequently accompanied by a commentary conveying previously expressed parental attitudes, such as praise or criticism of what a toy is being made to do.

Finally, by participating in relatively formal games, the older child has to adhere to rules established by others. To be successful, the child must learn to take the viewpoint of others, both on their side and in opposition, for instance in cards or ball games, in order to anticipate what the others are likely to do. Thus, through each stage, the child engages more and more with the viewpoints of other people, developing the power of empathy. Eventually they are able to appreciate the typical perspective of those within their culture, for example what the average person might think of their thoughts, appearance and behaviour (Cooley’s looking-glass ‘self’). Mead termed this adoption of the ‘role of the generalized other’, and this ability provides a yardstick against which to evaluate one’s self or a virtual mirror to reflect one’s self-image as viewed by others. This limitless source of socially grounded feedback enables the person to subtly and continuously modify and refine their ‘selves’ throughout life, both in later interactions with the agents of secondary socialization (p. 195) and in moments of solitary ‘self-reflection’.

Refinement of self in adulthood occurs during ‘pro-fessional’ or ‘tertiary’ socialization, whereby people acquire the knowledge, skills and attitudes peculiar to an occupational role (p. 195). Goffman (1971) described the process of assuming the behavioural component of such a role in terms of taking part in a drama. Initially an actor may feel not entirely natural in a part, and uncertain about how convincingly they can fulfil a well-established role, just as a student might that of ‘nurse’. A professional ‘mask’ is self-consciously adopted to begin with, and feedback gained on performance from observers, e.g. mentor. Aspects of performance can be modified until the person feels confident about fulfilling the role’s requirements and can routinely ‘play’ it naturally.

To summarize, the ‘self’ is an elusive and vague concept. It comprises psychological and physical components that are interrelated. People develop their self-concept in the course of continuing social experience, through their interactions with others. Their view of themselves is much influenced by the culture in which they exist, and the reactions to them of the people they encounter, both real and imagined. The self-concept is fluid; they can adapt their ‘selves’ to varying situations, such as behaving quite differently in professional and domestic roles. Lastly, because of the tendency to constantly evaluate the self-image, which generates conscious self-esteem, the self-concept is crucial in determining a person’s emotional well-being – it is intrinsic to their inner contentment.

Cognitive (intellectual) development

The most influential researcher in this field has been the Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget (1896–1980) who worked on the development of early intelligence tests. These instruments implicitly assume that intelligence is an attribute determined at birth, or early in life, and unchanging thereafter, and that it can be estimated through standardized questions. Rather than taking this usual focus, Piaget became fascinated with children’s typically incorrect answers to items beyond their chronological ability. He felt that these yielded unique insights, as they reflected the characteristic, if immature, ways in which children think. Consequently, he devised a series of tests specifically designed to shed light on intellectual processes at different ages.

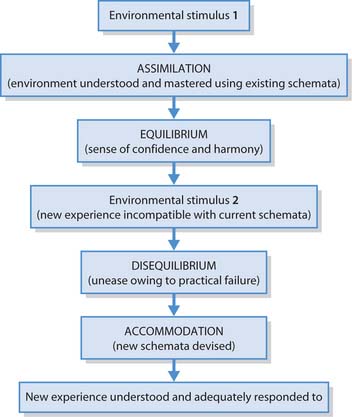

Piaget believed that human understanding of reality was not inborn, but had to be actively ‘discovered’ through interactions with the real, outside world, the child effectively learning as a scientist would. In other words, intelligence ‘evolves’, just like the characteristics of a species in response to environmental challenges, ensuring survival and success. Initially, reflexes (‘automatic’ responses) suffice in these interactions, so that the infant can both derive nourishment from its mother’s breast or a bottle teat and investigate objects such as toys through automatic sucking and licking. A psychologically comforting state of ‘equilibrium’ results through being able to ‘accommodate’ or successfully respond to every encountered challenge by existing strategies – ‘schemata’ (singular schema) are the building blocks of Piagetian intelligence. However, the growing infant comes to find sucking and licking less successful in dealing with solid food or unpleasant-tasting objects that they handle, resulting in inner dissatisfaction or ‘disequilibrium’. This necessitates the formation of new strategies, such as biting and chewing food, scrutinizing and fingering objects, better suited to new challenges – the process of ‘accommodation’. According to Piaget, this continuous process, known as ‘equilibration’, of employing old schemata until they fail and then replacing them with new, more suitable ones characterizes adaptation, and so intellectual development, throughout life (Fig. 8.5).

Assimilation allows people to practise recently acquired skills, e.g. in nursing, until they achieve routine competence in them. Accommodation enables people to formulate innovative approaches towards solving new problems. Both processes are thus complementary and integral to lifelong learning and the development of the mastery that characterizes the expert nurse.

An everyday example might be being offered chopsticks for the first time in a Chinese restaurant, where a person might try them, especially if everyone else around does. Assimilation would involve trying to use the sticks as a blunt spoon, attempting to scoop the food up with them. Much of it, especially the rice and sauce, will fall before it reaches their mouth, creating embarrassment and frustration (disequilibrium). With practice, the person learns to move each chopstick separately, allowing the tips to grasp food securely (accommodation). Success makes the person feel competent and appeases their hunger (equilibrium). Feeding dependent patients also involves new strategies, such as prior consideration of comfort, hygiene and dignity, then asking them in what sequence or mixtures they would like their food, when they might like a drink and observing repeatedly when their mouth is empty. All of these strategies occur automatically when people can feed themselves (adapted from Napier University Module booklet 2, 1997, 2001).