Chapter 13 Safety in nursing practice

Introduction

The International Council of Nurses (2004) describes the nursing role as promoting health, preventing illness or caring for ill, disabled or dying people along with acting as an advocate and promoting a safe environment. An individual’s health and their safety are very closely linked, and a fundamental part of nursing care is to identify factors that influence a person’s safety. This may include actual factors, e.g. being unable to drink that has led to dehydration and confusion in an older adult, or potential hazards, e.g. if a toddler is given a very small toy they are at risk of choking.

Healthcare practitioners have a responsibility to look after their own safety and that of the people they work with. Many issues have the potential to affect everyone in a care setting, e.g. poor handling techniques could result in an injury to the patient/client, yourself and a colleague. Therefore, the overwhelming emphasis in this chapter is on promoting the health of everyone concerned through prevention, identifying the risks and eliminating or minimizing them through safe practice. This is achieved by exploring:

Subsequent chapters address harm reduction further, e.g. infection control (Ch. 15), safe administration of medicines (Ch. 22), patient assessment (Ch. 14) and nursing care. These are all elements of safe practice and require further reading to aid your development and understanding. Additionally, a safe practitioner is able to identify and minimize hazards for patients/clients, a fundamental part of the Nursing and Midwifery Council’s (NMC 2004) Code of Professional Conduct. This requires being able to demonstrate a number of other qualities and skills, as outlined below. These skills are used throughout this chapter while addressing diverse safety topics and will help you to develop into a safe practitioner.

A critical or questioning approach

This means that you will ask if something is unclear, or tactfully challenge practice. It is important to develop the confidence to speak up if you do not understand or you think safety may be compromised. It is possible to discuss such concerns with mentors, senior clinical staff or university teaching staff, depending on the situation.

Recognize limitations of knowledge and skills, and seek support

Self-awareness is an essential skill for all nurses and knowing the limitations of your knowledge and clinical skills means that you are less likely to try something beyond your capabilities (which may go wrong). Where you are unsure, always seek support from mentors, read around the topic and speak to teaching staff if necessary.

Use of evidence-based practice

Nursing practice should be based on interventions that are known to be safe, effective and informed by research findings (see Ch. 5), clinical expertise and the patient’s/client’s own wishes.

Use of reflection during and after practice situations

Reflection (Ch. 4) is a valuable learning tool and helps to make sense of situations, apply the theory behind a topic, highlight the positive points and identify areas for future action.

Before moving on, complete the exercise in Box 13.1 to explore the relationships between nursing, health and safety.

Relationships between nursing, health and safety

Student activity

Take a piece of paper and on the left-hand side write down the main activities nurses do in everyday practice. On the right hand side write down how this helps the person’s health and reduces harm (and is therefore concerned with their safety). The examples below should help you to start:

| Nursing activity | How this improves health and maintains safety |

|---|---|

| Helping someone to eat and drink | Provides energy and nutrients for daily life and recovery |

| Prevents malnutrition and health deteriorating | |

| Able to go home more quickly, maintains independence | |

| Pressure area care | Prevents pressure ulcers developing |

| Helping people with their medication |

Risk assessment

Risks are taken in our everyday lives: some result in positive gains such as winning a lottery; others have negative outcomes, e.g. taking part in a contact sport can result in injury. Risks are also managed regularly to reduce the likelihood of negative outcomes occurring, e.g. wearing seatbelts and having airbags decrease the risk of injury in the event of a car accident.

In clinical practice the word ‘risk’ tends to be associated with negative outcomes (Jacobs 2000) and there are many potential and actual hazards that can cause harm to patients/clients and staff. Nurses need to identify hazards and reduce the likelihood of harm occurring to any party. This may be as simple as mopping up water on the floor to stop people slipping or more complex such as using an electric hoist to help clients who cannot stand to transfer from their bed to a chair safely. Much of nursing practice focuses on helping people to remain safe and this section explores the way in which risks are identified and reduced to minimize potential harm. The principles of risk assessment are discussed here, illustrating common issues across all nursing specialties. However, people receiving care may have unique health issues and require an individual assessment, and this is explored on page 324.

Risk assessment principles

A hazard has been defined by the Health and Safety Executive (2003a, p. 3) as ‘anything that can cause harm, e.g. chemicals, electricity, working from ladders’ and a risk as ‘the chance, high or low, that somebody will be harmed by the hazard’. It is important to understand the relationship between hazards and risks. A lightning strike presents a serious hazard that can result in death but the risk, or likelihood, of it happening to an individual in their lifetime is very small. Even when you know what the hazards and risks are, other factors can increase or decrease a risk. Going out into wide, open spaces during a thunderstorm may increase the risk of being struck by lightning. Clinical practice can also illustrate this. When drawing up or giving injections, needles are never resheathed because of the potential hazard of a needlestick injury and transmission of blood-borne viruses, e.g. hepatitis B, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (see Ch. 15). The risk of a needlestick injury is greatly reduced if nurses adhere to the guidance, but lack of knowledge or understanding about the importance of this increases the risk of an injury occurring to the nurse. Before reading the rest of this section, complete the activity in Box 13.2.

Hazards that can cause accidents

It may not be possible to eliminate risks completely but by identifying the hazard, risk and associated factors the chances of harm occurring can be minimized. This process is called risk management and the first stage is known as risk assessment. There are several reasons why risk assessments are undertaken, including patient/client welfare and ethical and professional responsibilities, including a duty of care to protect vulnerable people (Ch. 7). The NMC Code of professional conduct (NMC 2004, p. 10) emphasizes nurses’ responsibilities in one of the key standards: ‘You must act to identify and minimize risk to patients and clients.’ Risk assessment is also an integral part of health and safety legislation (see p. 327).

The process of risk assessment may sound complicated, but it is essentially an examination of the factors that could cause harm to people in a care environment so that precautions can be taken to prevent injuries (HSE 2003a). The activity in Box 13.2 is the start of a risk assessment. There are usually five stages to risk assessment:

These stages are explored in a series of text boxes using a moving and handling example from each nursing specialty. The scenarios focus on hazards for staff and patients/clients and follow one of the basic principles, i.e. looking after your joints and your back (not stooping, twisting, reaching or lifting people).

Step one: Look for the hazard

This involves walking round a clinical area to identify what sort of things could cause harm to people, talking to the staff to find out what problems they experience and examining accident and sickness records to identify any particular patterns (HSE 2003a). Examples of this are provided in Box 13.3.

Box 13.3 Risk assessment in nursing settings –Step 1: Look for the hazard

Step two: Decide who may be harmed and how

This essentially refers to the staff and patients/clients involved, but must also include visitors and employees who may be in the clinical area temporarily, e.g. cleaners, contractors, etc. (HSE 2003a). Now read Box 13.4, which builds on the moving and handling scenarios above.

Risk assessment – Step 2: Decide who may be harmed and how

Student activities

For each setting in Box 13.3 identify:

The example from Sunshine Hospice is given below to start you off.

Step three: Evaluate the risks and decide what should be done

This stage of the risk assessment involves looking at the likelihood of harm occurring (remember the being struck by lightning scenario?) and deciding whether the risk is high, medium or low. Then the risk has to be made as small as possible by taking precautions (HSE 2003a). This could include using equipment and educating staff so that they are aware of the risks and can take precautions themselves. Box 13.5 gives two examples of how this may be done.

Box 13.5 Risk assessment – Step 3: Reducing the risks

Ward B2

There have already been two accidents with patients using toilets on B2 so the risk of further injury is high. Installing non-slip flooring, grab rails and a raised toilet seat can minimize the risk. Each patient must be assessed for using the toilet; they need to be independent as the area is too small for staff to assist safely. Reviewing staff knowledge of how to deal with a fallen patient would also be a useful exercise.

Step four: Record the findings

With each scenario above, the results of the risk assessment must be recorded. Healthcare organizations usually have specific documentation for this process. Written records also demonstrate that employers have abided by the law (HSE 2003a) and can complete the final stage.

Step five: Review the assessment and revise if necessary

Risk assessments need to be reviewed regularly and when there are any significant changes. A date is often set to remind people when to review the assessment.

The risk assessments described here could be applied to a number of patients/clients or staff and the focus is the specific task, e.g. transferring people from a wheelchair to the floor. This is often referred to as a generic assessment and comes under health and safety law. Therefore it is the responsibility of the employer to carry this out although senior management may delegate the assessment to a specific individual trained in risk assessment and who regularly works in that clinical area (Box 13.6). Nurses have a duty of care (see Ch. 6) to follow the procedures that reduce the risk, such as using equipment provided and to report situations where safety is compromised.

Individual risk assessments

A person’s health and social care needs are unique and nursing assessment (Ch. 14) includes identifying actual or potential hazards that can affect their health. A wide range of assessment tools have been developed to help nurses and other healthcare professionals identify whether people are at risk of specific factors such as malnutrition or pressure ulcers (see Fig. 14.3, p. 357). Box 13.7 lists some of these tools and sources of further information. Most assessment tools offer a checklist and a scoring system, with the overall result giving an indication of the degree of risk, e.g. high, medium or low risk of developing pressure ulcers. The assessing nurse can then decide how to minimize those risks.

Box 13.7 Examples of specific risk assessment tools

| Area of risk assessment | Further information |

|---|---|

| Falls risk assessment | Cooper G 2003 Developing an evidence based approach to falls – risk assessment. |

| Professional Nurse 19(1):19–23 | |

| Moving and handling | Raine E 2001 Testing a risk assessment tool for manual handling. Professional Nurse 16(9):1344–1348 |

| Nutritional intake | Arrowsmith H 2000 A critical evaluation of the use of nutritional screening tools by nurses. British Journal of Nursing 8(22):1483–1490 |

| BAPEN, Malnutrition Advisory Group 2003 The Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST). Online. www.bapen.org.uk Available July 2006 | |

| Pressure ulcer development | Waterlow J 1998 History and use of the Waterlow card. |

| Nursing Times 94(7):63–67 | |

| Suicide risk assessment | Frierson RL, Melikian M, Wadman PC 2002 Principles of suicide risk assessment. Postgraduate Medicine 112(3): 65–66, 69–71 |

Assessment tools are designed to help nurses in practice identify particular risks but they do not replace clinical judgement. For example, a nutritional assessment tool might indicate that a patient admitted for surgery is currently at a low risk of malnutrition (see Ch. 19). However, the patient will spend at least 4 hours fasting prior to surgery (Ch. 24) and thereafter may not be able to eat or drink for several hours or experience nausea and vomiting. They will therefore be at higher risk of developing malnutrition and this indicates the importance of regular reassessment.

The discussion on generic risk assessments above highlighted a common issue across all nursing specialties, namely moving and handling. For individual assessments a number of branch-specific issues arise. Risks are taken as part of growing up and everyday life as we develop and learn. This may occur on many different levels, e.g. crossing a busy road, smoking cigarettes or drinking alcohol, starting a new relationship or embarking on a career, and these can often be a case of trial and error. Risk taking is a natural part of life and if people who have learning disabilities or mental health conditions are overprotected, this can lead to social exclusion and infringement of their rights and dignity (Alaszewski & Alaszewski 2000).

To promote social inclusion, people need to be allowed to take reasonable risks to aid their development by promoting independent living and social activities. The regulatory body that preceded the NMC, the United Kingdom Central Council for Nursing, Midwifery and Health Visiting, published guidance on risk management for people with learning disabilities and mental health problems (UKCC 1998). The guidelines suggested that risk assessment should consider client care, the care system and the local environment. Risks still need to be reduced to a minimum and agreed by the multidisciplinary team and client but the value of risk-taking should be recognized. Box 13.8 presents a case study and an opportunity for reflection on a number of issues discussed here.

Promoting independent living and social activities

You are on a 4-week placement at a busy day centre for young adults with mild to moderate learning disabilities. Tom is 17 years old and you have been working closely with him for the past week. When he first arrives he confides in you saying he had a fight with his mum before he left home. After discussing this further, you find out that he had asked for three things for his 18th birthday: a rally car, a mountain bike and to go to the cinema with his girlfriend Cheryl who also attends the day centre. His mum had said that he would not be allowed to drive but Tom was more upset about not being able to go to the cinema alone with Cheryl. The cinema is 4 miles from Tom’s home and he and his mum usually travel together on the bus. He has never used public transport alone.

Health and safety legislation

Legislation plays a major role in promoting safety of individuals and public health in general. This section briefly examines the regulations in place in the UK to prevent accidents and ill health and also the health and safety responsibilities of employers to protect staff and the public.

Maintaining safety and promoting health

Wide-ranging legislation exists to promote public health and safety including:

Governments also publish specific public health strategies such as Saving Lives: Our Healthier Nation (DH 1999a) and Choosing Health: Making Healthy Choices Easier (DH 2004) which focus on reducing death rates from cancer, coronary heart disease and strokes, mental health illness and accidents (see Ch. 1). Specific documentation and targets have followed in the form of National Service Frameworks, e.g. for children, older people, mental health, coronary heart disease, diabetes, cancer (see www.dh.gov.uk for publications).

One government target is to reduce death and injury rates from accidents in the home by 20%; another is a 40% reduction in road accidents (including a 50% reduction in the number of children seriously injured on roads). The proposals seek to reduce the 10000 lives lost per year to accidents and focus on the main causes within each age group:

The preventative measures proposed include an increase in traffic calming measures, design of safe play areas for children, changes in building regulations, the use of safety glass for doors and road safety training for children. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE 2004) provided guidance on assessment of older adults with the aim of preventing falls and minimizing their recurrence. Falls prevention campaigns have also been launched, aimed at educating older adults. Where accidents do occur, the target is for faster diagnosis and effective treatment to improve health outcomes. By undertaking the activities in Box 13.9 you will find out more about assessment and prevention of falls in older adults.

[Resources: Department of Trade and Industry 1999 Avoiding slips, trips and broken hips. DTI, London; Department of Health 2001 National service framework for older people. DH, London; NICE 2004 Falls: the assessment and prevention of falls in older people. Online: www.nice.org.uk/CG021 Available July 2006]

Falls prevention

80% of falls in the home involve an older adult; they may result in fractures, long-term disability and are a major cause of mortality in this age group (DTI 1999). Even minor falls can result in loss of confidence, loss of mobility leading to social isolation and increased dependency and disability. The National Service Framework for Older People (DH 2001) sets specific targets for reduction in the number of serious injuries resulting from falls and appropriate rehabilitation of people who have fallen. Many multidisciplinary teams have been established to assess individuals and run falls prevention programmes.

Student activities

Nurses across all specialties may have a number of roles to play in accident prevention as they come into contact with people at various stages of their lives for health promotion and treatment measures in various settings including the community, hospitals, clinics, schools and walk-in centres. This may be as part of a local education or screening programme on accident prevention for patients/clients or their families. Nurses are also heavily involved in people’s care after accidents have occurred and this provides opportunities for assessment and education to prevent further accidents.

Health and safety in healthcare settings

The Health and Safety at Work Act (1974) is the main piece of UK legislation that places specific responsibilities upon employers to protect the welfare of people at work and the public. Under this Act, many subsequent regulations have been issued which deal with specific topics such as manual handling and the safe use of equipment. Although employers are responsible for providing a safe working environment, employees have responsibilities for:

Health and safety is essentially everyone’s responsibility. This section presents the main legislation that applies to clinical practice (Table 13.1) and summarizes the key points.

Table 13.1 Main health and safety regulations under the Health and Safety at Work Act (1974) (based on HSE 2003b)

| Regulation | Date or most recent amendment | Main aim |

|---|---|---|

| Management of Health and Safety at Work | 1999 | Ensures employers carry out risk assessments, implement changes and appoint qualified people to provide information and staff training |

| Workplace (Health and Safety and Welfare) | 1992 | Ensures employers cover range of health and safety issues, e.g. ventilation, heating, lighting, seating, welfare facilities |

| Health and Safety (Display Screen Equipment) | 1992 | Lays down requirements for people who work with visual display units (computer screens) |

| Personal Protective Equipment at Work | 1992 | Ensures that employers provide protective clothing and equipment for employees |

| Provision and Use of Work Equipment | 1998 | Ensures that employers provide safe equipment for use at work |

| Manual Handling Operations | 1992, amended | Lays down requirements for the movement of loads by hand or involving bodily force |

| 2002 | ||

| Reporting of Injuries, Diseases and Dangerous Occurrences | 1995 | Employers must report work-related accidents, diseases and dangerous occurrences |

| Control of Substances Hazardous to Health | 2002 | Ensures that employers identify hazardous substances, assess risks to employees’ health and take appropriate action to reduce risks |

| Noise at Work | 1989 | Ensures that employers use systems that protect environments |

| Electricity at Work | 1989 | Electrical systems are safe and well maintained |

| Health and Safety (First Aid) | 1981 | Ensures employers provide adequate first aid equipment and personnel |

The Health and Safety Commission (HSC) and the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) enforce health and safety law in the UK under criminal law, as opposed to civil law, which focuses on personal claims for compensation (see Ch. 6). This means that employers may be heavily fined, or worse, for failing to comply with health and safety regulations. The HSW Act (1974) laid out general duties for employers to:

The Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations (1999) were more specific and requires employers to carry out:

These two pieces of legislation provide the background and general principles for health and safety but is useful to look at some of the more specific regulations highlighted in Table 13.1 and their implications for clinical practice.

Control of Substances Hazardous to Health (COSHH)

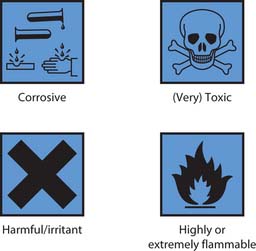

Chemicals and other substances used at work can be hazardous to people’s health and employers must control exposure to prevent harm occurring (HSE 2003c). Hazardous substances include chemicals, gases, dust and biological agents (blood and blood products, microorganisms) that can cause illnesses ranging from mild allergic reactions to occupational asthma and death. Risk assessments are therefore carried out and precautions put in place, including:

Manufacturers must also supply information and warning labels on hazardous substances, both domestic and industrial (Fig. 13.1). These highlight whether the chemical is an irritant, corrosive, highly toxic or flammable and it is important to be familiar with these (Box 13.10).

Recognizing hazardous chemicals

The hazard signs in Figure 13.1 appear on chemicals and toxic substances used at home and in placements. You should always read the labels on products you are using.

Reporting of Incidents, Diseases and Dangerous Occurrences Regulations (RIDDOR)

Accident statistics, covering the period 2001–2004 (HSE 2004a), are shown below:

In 2002/3 injuries for the health services included:

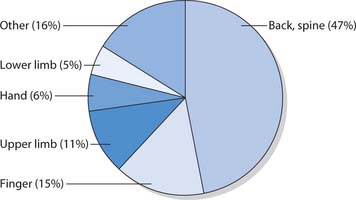

Figure 13.2 illustrates the areas of the body affected by handling accidents. The government and the HSC have set a target for a 10% reduction in health service accidents between 1999/2000 and 2009/2010.

Fig. 13.2 Sites of injuries lasting over 3 days caused by handling accidents (2001/2)

(reproduced with permission from HSE 2004b)

RIDDOR aims to ensure that accidents and near misses are documented and reported to the HSE so that these can be investigated if necessary and harm reduction measures implemented. Reportable incidents include a patient/client, visitor or member of the public or staff experiencing one of the following:

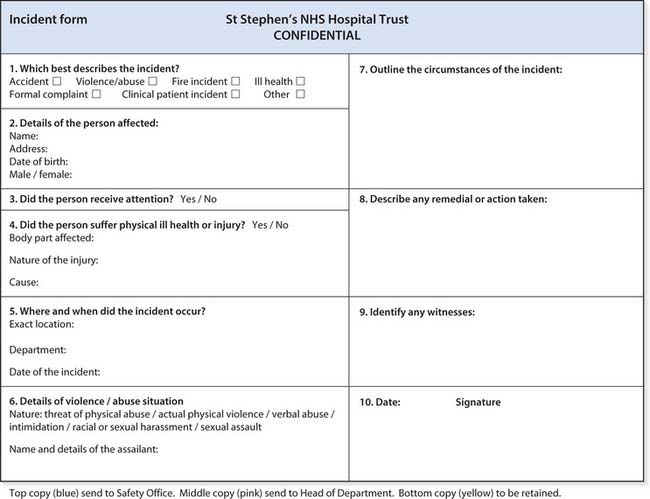

In nursing practice, all accidents and near misses are documented using the local NHS electronic or paper incident forms (Fig. 13.3) which health and safety representatives of the healthcare organization then review and report to the HSE as necessary.

In addition to the general targets for reducing accidents in the health service, the government established the National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA) to reduce the estimated 900000 patient safety incidents and near misses every year. As well as advising on particular universal issues, e.g. intravenous infusion pumps, the NPSA collect and analyse incident reports from across the country. This information is used to advise on preventative measures and to build a culture of safety and learning within the health services (NPSA 2004) (Box 13.11).

Reporting incidents in placements

Student activities

Equipment used at work

Provision and Use of Work Equipment Regulations (PUWER 1998) and Lifting Operations and Lifting Equipment Regulations (LOLER 1998) are designed to cover a range of industries but both ensure that equipment used at work is:

In addition, LOLER relates to equipment such as electric hoists that should be tested at 6-monthly intervals and have safe working loads (maximum patient/client weight) clearly marked on them (HSE 2000).

Manual Handling Operation Regulations 1992 (amended 2002)

Moving and handling includes lifting, lowering, pushing, pulling, carrying or moving loads such as inanimate objects, and helping people to move. Nursing involves many of these activities on a day-to-day basis and using incorrect techniques or failing to use equipment provided puts practitioners at high risk of injury. Musculoskeletal injuries occur frequently at work in the UK and have considerable economic implications (see Box 13.12). Many of these injuries are preventable and the Manual Handling Operation Regulations lay out the requirements under health and safety law and the responsibilities of employers and staff.

Box 13.12 Musculoskeletal injuries in the UK and NHS

[From DH 2002]

This section introduces the principles of safe practice but moving and handling must not be undertaken without completing a specific course that addresses the theory of safe handling and allows practice of techniques (Box 13.13). Readers should refer to Chapter 18 for further guidance on helping patients and clients to move.

Box 13.13 Recommended components of moving and handling training

[Based on DH 2002]

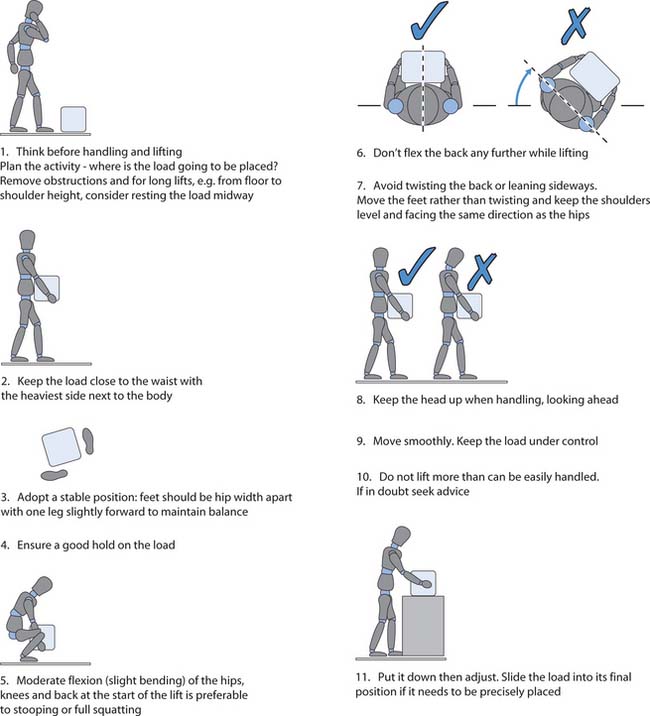

There are five key stages to planning and executing a handling manoeuvre to reduce the risk to the handler and patient/client.

Moving and handling require an approach similar to other health and safety issues and one of the first stages is a risk assessment. This may be:

The TILE framework

This helps to think through the move using biomechanics (the study of human movement) and ergonomics (the science of design and fitting the work environment to the worker). Both of these disciplines contribute to the understanding of how to prevent injuries. TILE is discussed below based on the guidance from the HSE (2004b) and Johnson (2005).

The task (T)

Assessing the task means identifying the factors that may cause injury and eliminating or reducing them. The HSE (2004b) suggest that the following questions be asked:

Holding an object close to the trunk means that it is easier to control and there is less risk of back injury compared to holding it at a distance or at arms’ length.

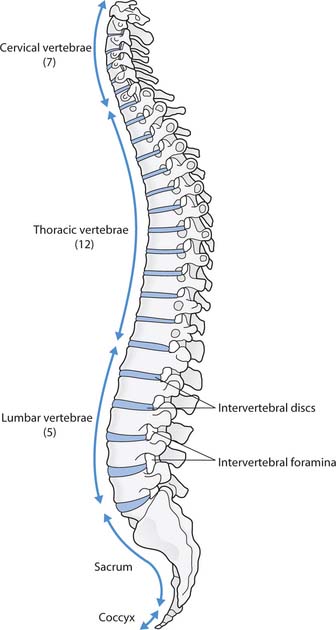

Stooping, twisting and reaching greatly increase the risk of injury because they place stress on the lower spine. These actions must be avoided in moving and handling tasks by using legs and feet to move rather than twisting at the trunk and by remaining close to the load or patient/client.

Carrying objects over long distances or repetitive lifting or lowering can cause fatigue and increase the risk of injury. Equipment, such as a trolley, reduces the risk of injury from carrying. Also, heavier items should be stacked on shelves at waist height so they are not lifted from the floor or high shelves.

Pushing and pulling may be a safer technique than lifting but it can still put the handler at risk of injury. For example, pushing a heavy load along an uneven surface or up a slope could be unsafe.

If the contents of a half full box are not secure they may shift during movement so the load needs to be secure to be safe. If the task involves people, there is always a risk of unexpected movements so the likelihood of this occurring is reduced by making sure the patient/client knows their role and what to expect so they do not become frightened or uncooperative.

The greater the physical effort, the greater the risk of injury, and inadequate rest periods mean that muscles and joints do not get a chance to recover.

As part of the risk assessment, the equipment available for the task needs careful consideration. There is a wide range of aids available, from sliding sheets that reduce friction and help people move up in bed, to electric beds and hoists that assist people to sit up, transfer or stand (see Ch. 18). During your moving and handling practical training, you will have the opportunity to practise with a range of equipment used in placements. Equipment must be well maintained and checked before each use. It is important to be aware that all equipment has a safe working load, i.e. an upper weight limit for use, usually marked on larger pieces of equipment such as hoists. This is why it is important to document patients’/clients’ weight as part of nursing assessment (Ch. 14). Infection control precautions also need to be considered, e.g. whether equipment can be disinfected with alcohol wipes or if special laundering arrangements are necessary.

Individual capabilities (I)

This refers to the assessment of handlers’ abilities. Nursing activities should not require great physical strength but general fitness and regular exercise are important as these reduce the risk of injury. We must also assess our ability to be involved in moving and handling on a daily basis. Classroom trainers or clinical staff must be alerted to any pre-existing or current injuries that could prevent you from being involved in safe moving and handling. People with existing injuries and those who are, or have recently been, pregnant require an occupational health assessment.

Inappropriate clothing can restrict movement during handling manoeuvres or encourage adoption of awkward postures to protect the handler’s dignity, and both situations increase the risk of injury. Most uniform policies include trouser suits that allow freedom of movement and footwear that is flat and provides plenty of grip. It is therefore important to follow local uniform policies.

The load (L)

The manual handling guidelines identify a number of factors for consideration regarding the load (if it is an inanimate object) or the patient/client involved. For objects, it is important to have an indication of their weight. This is often printed on boxes or can be judged by gently rocking the item before deciding whether to lift it. The size of the load is considered and whether it is possible to split it in two to make handling easier. Other areas to consider are the type of grip to use and whether the item could be too hot or sharp to handle.

Patients/clients should not be lifted because of the risk of injury to the person and the handlers. Nurses must assess people’s capabilities and then determine the best technique or equipment to help them move. One difficulty is that people do not come as a standard size, with handles, or with their height and weight printed on the side. Many people receiving healthcare have the added complication of ill health and attachments such as intravenous infusions and urinary catheters. Therefore specific assessment must be carried out for each patient/client before carrying out manoeuvres. Care settings including NHS Trusts should have their own moving and handling assessment documentation as part of the nursing care plan; some of the key areas that require consideration are outlined in Box 13.14.

Box 13.14 Summary of the TILE assessment for moving and handling

Task (T)

Assess and minimize the risks that cause injury, e.g. holding the load or person away from the trunk, twisting, stooping or reaching, considerable lifting, lowering or carrying distances for objects and pushing or pulling. Assess the need for team handling and think about the range of equipment available including its safe working limits, its condition and last recorded service.

Individual (I)

Assess the capabilities of staff, e.g. their age, gender, height, physical fitness, previous injuries, current or recent pregnancy, training, knowledge or experience, and wearing of restrictive clothing or inappropriate footwear.

The environment (E)

There are many factors in the environment that can increase or decrease the risk of injury to handlers and patients/clients. It is important to assess whether there is adequate lighting; non-slip flooring; a floor gradient or potential obstacles, e.g. doors, furniture, stairs. Extremes of temperature can also alter people’s concentration levelsand physical abilities. Moving and handling need to be planned to ensure that none of these factors contributes to an injury. There must be sufficient space to avoid awkward postures or techniques and it is important to be alert tohazards that may cause you and the client to slip or trip.

Moving and handling procedures cannot be completely risk-free but the TILE framework allows major hazards to be identified and reduces injuries to staff and patients/clients through using the correct technique and equipment. Figure 13.5 illustrates a good handling technique for lifting an inanimate load and Chapter 18 examines specific techniques for helping people to move.

First aid

This term describes the initial treatment or assistance given to an individual who is injured or unwell before the arrival a qualified healthcare professional, e.g. paramedic or doctor. The aim is to preserve life, prevent worsening of a condition and promote recovery (Mohun et al 2002). This section discusses first aid at work, the general principles of first aid and how to deal with some specific emergencies, i.e. burns and scalds, and suspected poisonings.

All employers must provide first aid facilities, equipment and personnel under the Health and Safety (First-Aid) Regulations 1981 (HSE 2003b), including:

Green posters may also advertise where the nearest first aid box is located and the names of trained first aiders. Some clinical areas may be better equipped to deal with emergencies than others, e.g. comparing a hospital ward and a day centre for older adults. However, all are required to conduct risk assessments and provide appropriate facilities.

Administering first aid outside placements can be very different as equipment is not readily available. Also, not all nurses are trained first aiders although they do have knowledge that is useful in an emergency situation. First aid and emergency skills are part of pre-registration programmes as required by the NMC. The NMC Code of Professional Conduct (2004) also describes the duty of care that nurses have outside work in an emergency situation. Often nurses are concerned about expectations of them but any first aid provided is judged in relation to the particular circumstances and against what can reasonably be expected from someone with their level of knowledge, skills and abilities (NMC 2004). This means that expectations of an experienced nurse working in an Emergency Department would be much higher than a student nurse who has only completed a basic life support course.

Some people may be concerned about the legal aspects of first aid provided outside the healthcare environment and being held to account if events do not go as well as anticipated. Similar to the NMC guidance, so long as first aiders have acted in a reasonable manner and this conforms to any training given, they will be in a safe position. The casualty would have to have had experienced further harm as a direct result of first aid given to be in a situation to sue for compensation (Dimond 1993).

This section introduces the basic principles of first aid and subsequent chapters deal with specific situations (Box 13.15). As well as reading the information in these chapters, there are other considerations that can help to develop knowledge and confidence. Some first aid skills are included in nursing programmes and attending a recognized training course to become a qualified first aider may help (see ‘Useful websites’, p. 347). Remember that first aid should ‘do no harm’ and that recognizing the limitations of one’s knowledge and skills is important; however, you may be the only person present who has attended a basic life support or first aid course and simple measures will often help save someone’s life or prevent their condition worsening.

Box 13.15 First aid covered in this book

| Chapter | Topics |

|---|---|

| 13 | Principles of first aid, dealing with burns, scalds, poisoning |

| 14 | Effects of heat and cold: heat exhaustion, heatstroke, hypothermia, frostbite |

| 16 | Disorders of consciousness: head injury, seizures |

| 17 | Respiratory problems: choking, suffocation, smoke inhalation, asthma |

| Circulatory problems: cardiopulmonary resuscitation, shock and haemorrhage, fainting; myocardial infarction (heart attack), angina (chest pain) | |

| 18 | Musculoskeletal problems: sprains and strains, dislocations, fractures |

| 25 | Wounds: abrasions, lacerations, puncture wounds, bites and stings |

Dealing with emergencies and prioritizing

Emergency situations can be difficult to deal with as people may be distressed, in pain or confused and there may be more than one injury or a number of people involved. However, it is important that you remain calm and apply some simple principles (based on Mohun et al 2002) that will help to organize your thoughts and decisions on the most appropriate action. The principles of first aid are listed in Box 13.16 and described below.

Principles of first aid

Student activity

Test your knowledge of first aid by accessing quizzes online, e.g. www.bbc.co.uk/health/first_aid_action/first_for_fun.shtml Available July 2006.

Assess the situation

Make a brief visual assessment of what has happened, looking for evidence of danger or potential hazards for yourself and the casualty. The most important rule of first aid is that you never put yourself in danger otherwise you too may become a casualty. Once you have determined that it is safe, introduce yourself to the casualty or bystanders and ask them to describe what has happened.

Check the area is safe for you and the casualty

Can you safely remove potential dangers such as obstructions or switching off electric sockets? Only remove the casualty from the situation as a last resort and only if there is imminent life-threatening danger.

Make an initial assessment of the casualty and give emergency first aid if necessary

Chapter 16 discusses how to make an initial assessment of a collapsed individual by checking their responsiveness and then:

If the casualty has more that one problem, e.g. they are unconscious and their arm is bleeding, deal with problems in the ABC order, i.e. make sure their airway is clear, they are breathing and then attend to the source of the bleeding. If there is more than one casualty you will have to prioritize and decide who requires the most immediate attention. Again, use the ABC assessment. Quiet or unconscious casualties often require the quickest attention. You know that those who are crying or shouting at least have a clear airway, are breathing and also have a pulse. However, they will still need reassurance and assessment of their injuries so encourage bystanders to stay with, and reassure them.

Call for help

In a placement, call for help immediately by shouting and using emergency buzzers where available. You may be asked to put out a ‘crash call’, a telephone call to the switchboard that will alert the resuscitation team. Clearly state that there has been a cardiac arrest and give the name and location of the area. The National Patient Safety Agency (2004) asked NHS Trusts to standardize their crash call number to ‘2222’ so that the emergency number is always the same. Ensure that you find out the emergency number on the first day of each new placement.

Outside of placements, you will need to telephone 999 (in the UK) to summon emergency services. This phone call is free from public phone boxes and most mobile phones. State the emergency service required (ambulance, police, fire brigade, coastguard) and you will be put through to the appropriate call centre. You will be asked for your name and location and to provide the number of casualties and describe their injuries.

Provide first aid

Provide first aid and stay with the casualty until help arrives. Healthcare professionals will make their own assessment of the situation but your information about the event, your observations and the treatment given are useful to them.

After the event

Dealing with emergencies can be stressful and you may experience a range of emotions afterwards (Ch. 11). It is also quite natural to reflect on the situation, your role, what went well and what you would do differently if the situation occurred again. You might find it helpful to talk to your mentor or your personal tutor at university to help make sense of events or for advice about alternative sources of support.

Being a first aider in a serious incident can affect people weeks or even months later. Reliving the event in some way, avoiding situations that remind people of the event, sleeplessness and experiencing symptoms of stress may suggest that the first aider is experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder (Mohun et al 2002) (see Ch. 11). If this happens it is wise to seek the support of a general practitioner (GP) or counsellor.

Dealing with burns and scalds

Around 100000 people attend Emergency Departments in England and Wales annually because of burns. Most are caused either by dry heat (e.g. flames) or moist heat (e.g. steam, hot liquids or fat) (DTI 2003), although industrial and domestic chemicals can also cause burns along with high and low voltage electrical sources, radiation (including sunburn, X-rays and radioactive sources) and extreme cold (e.g. frostbite).

The skin is the largest organ in the body and is discussed in more detail in Chapter 16. The epidermis and dermis make up the two main layers of the skin and burns can involve both layers; in severe cases, the underlying subcutaneous fat and muscle layers are also affected.

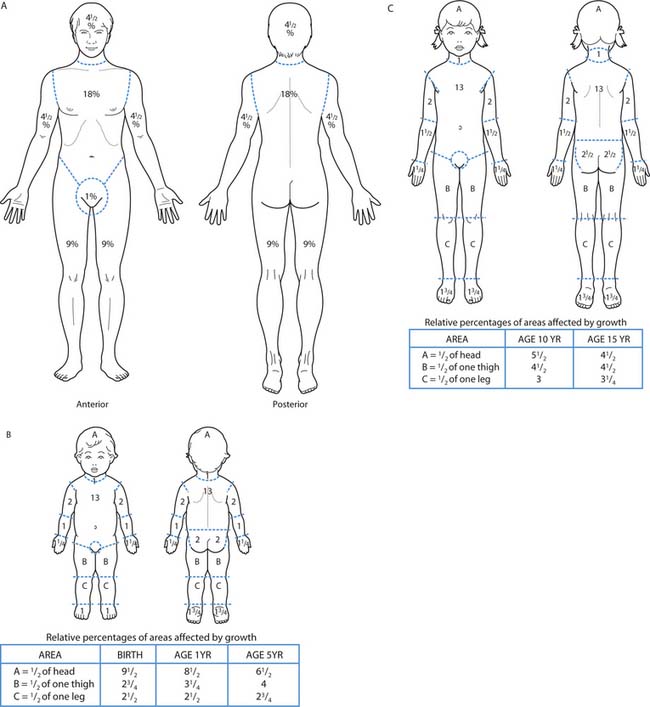

Burns are classified according to the depth and percentage of the body surface area involved. Box 13.17 illustrates the three depths of burn injury: superficial, partial thickness and full thickness.

The extent of burns may initially be estimated using the ‘rule of nines’ (Fig. 13.6): the greater the area affected, the greater the risk of shock caused by fluid loss. In adults, medical attention is needed for anything more that a minor superficial burn. A doctor should see children with what appears to be a superficial burn. Medical attention should always be sought for burns affecting the face, groin, hands and feet. When more than 15% burnsin adults is present specialist burns care in hospital is necessary. This figure is 10% burns in children where a modified chart is used to calculate the extent of burns because of the different sizes of children (Fowler 2003). Box 13.18 describes the management of burns and scalds.

Fig. 13.6 Estimating the extent of burns and scalds in adults and children: A. Adults: the rule of nines

(reproduced with permission from Waugh & Grant 2006). B. Children up to 5 years (reproduced with permission from Hockenberry et al 2003). C. Older children (reproduced with permission from Hockenberry et al 2003)

Burns and scalds

Aims of treatment

Treatment

Electrical burns

Extreme caution is required when there are electrical burns to ensure that the casualty is no longer in contact with the source of electricity. It may not be possible to attend to them until it has been confirmed that the current has been turned off (Mohun et al 2002). Anyone who has experienced an electrical burn must seek medical attention because the current may have interfered with the electrical activity of the heart.

Chemical burns

For burns caused by chemicals splashed onto skin or into the eyes, ensure that the water flushing the area runs away from the body so that it does not come into contact with any other region causing further burns. Unlike burns caused by heat, where clothes should be left untouched, it may be necessary to remove contaminated clothing. First aiders must wear protective clothing including heavy-duty rubber gloves and apron to protect themselves. When arranging for the casualty to be transported to hospital, ensure that paramedics are aware that chemicals are involved. Finally, burns caused by cold injuries, e.g. frostbite, require different treatment and should not be cooled (see Ch. 14).

Dealing with poisoning

A poison is any substance that enters the body in sufficient quantities to cause temporary or permanent damage. Poisons may be accidentally or deliberately ingested, inhaled, splashed on the skin or injected. Signs and symptoms vary according to the amount and type of poison involved and its route of entry. Box 13.19 shows the principles of dealing with a suspected or known poisoning.

Poisoning

Recognition

Ingested poisons

In clinical areas, healthcare practitioners have access to one of six UK centres that comprise the National Poisons Informati on Service (www.npis.org). This service includes a 24-hour emergency helpline and a toxicology database of known poisons and recommended treatments.

Infection control and standard precautions

Preventing the spread of infection is one of the most important nursing roles and is concerned with safety, preventing ill health, and promoting health and well-being in individuals or groups of people. This section briefly introduces key concepts of safe infection control practice and Chapter 15 examines them in more detail.

Standard precautions, previously known as universal precautions, were introduced in North America to reduce the risk of transmitting blood-borne viruses such as HIV and hepatitis B to healthcare workers. Both terms describe infection control guidelines that minimize the risk of coming into contact with body fluids (including blood, urine, faeces and other body secretions and excretions), non-intact skin and mucous membranes. The standard precautions outlined in Box 13.20 are used with every person receiving care, regardless of their infection status, in order to protect healthcare practitioners and prevent the spread of infection.

Box 13.20 Standard precautions

[Based on Wilson (2001) and Horton & Parker (2002)]

There are several routes by which bacteria, viruses, fungi and other infectious agents can be transmitted including inhalation, direct contact, ingestion and inoculation. However, effective handwashing has been repeatedly shown be the most important factor in reducing the spread of infection. Knowledge of appropriate handwashing techniques (see Ch. 15) and the necessary frequency is therefore essential (Box 13.21).

Many healthcare procedures are invasive, meaning that they use sharp devices that penetrate the skin or body in some way such as needles or surgery (Horton & Parker 2002). This carries the risk of needlestick injury to practitioners and also transmission of blood-borne viruses after devices have been in contact with patients/clients. Sharps therefore require careful handling and disposal (see Ch. 15). Sharps bins are special containers that conform to British Standard Institute specification which ensures that they are yellow in colour, puncture resistant, leak-proof, clearly marked with three-quarters lines indicating when they should be closed, suitable for incineration and marked with hazard signs.

In the community, some pharmacies and organizations offer needle exchange programmes for intravenous drug users. These harm-reduction programmes aim to help individuals reduce the risk of contracting hepatitis B or HIV by supplying clean needles and safely disposing of used equipment (see www.drugsinfo.org.uk for an example).

Clinical waste must be carefully managed to ensure that toxic or hazardous materials are handled, transported and disposed of safely. There are regulations surrounding clinical waste that needs to be segregated under the Environmental Protection Act (1990). This includes using appropriate bags for household waste such as paper and flowers which can be sent to landfill, yellow clinical waste bags for materials contaminated with blood or body fluids, and sharps containers that need to be incinerated (Wilson 2001). Hospital linen also has a colour coding system which determines how laundry bags are handled (see Ch. 15).

Infection control and standard precautions are an essential part of all healthcare practitioners’ everyday practice to ensure the safety of staff, patients/clients and the wider community. Chapter 15 is therefore an important chapter to read. Carrying out the activities in Box 13.22 will help you examine practice and familiarize yourself with infection control procedures and policies for handling, storage and disposal of clinical waste in your placement.

Principles of managing violence and aggression

Developing safe practice involves identifying potential risks and minimizing them, and the issue of violence and aggression is no exception. People are at highest risk of this when engaged in work that involves:

Nurses from all branches may be involved in these situations. However, the fear of violence and aggression can be out of proportion to the risks: although verbal aggression is more common and physical harm comparatively rare (Bibby 1995, HSE 2004c), both can have detrimental effects on practitioners. This section is about awareness and prevention. Being aware of the factors that can lead to aggression helps to develop the interpersonal communication skills that prevent incidents where aggression may occur and defuse tense situations.

As the phrase ‘violence and aggression’ may hold slightly different meanings for different people, it is useful to briefly describe and define the term so that we are able to recognize it when it occurs and deal with incidents appropriately. The RCN (2003a, p. 3) offers the following definition: ‘Any incident in which a health professional experiences abuse, threat, fear or the application of force arising out of the course of their work, whether or not they are on duty.’

Some organizations such as the RCN (2003a) and the Department of Health (1999b) simply use the term violence, others use violence and aggression interchangeably and some differentiate between the two. Both terms are used here referring to non-physical (aggressive) and physical (violent) behaviours (Box 13.23).

Minimizing violence and aggression

The reasons why violence and aggression occur are usually complex; for an in-depth discussion, refer to Mason and Chandley (1999) who examine the wider issue of violence in society. For healthcare practitioners there may be a number of additional factors that contribute to an increased risk of witnessing or being involved in an incident. People receiving healthcare may be anxious, tired, in pain, confused, frustrated by waiting times, under the influence of drugs or alcohol, have mental distress or a history of violence – and all of these predispose to unpredictable behaviour. Nursing often takes place in stressful situations and treatment or facilities may be granted, denied or delayed (RCN 2003a).

Over recent years there has been increasing concern in the nursing media and general press about increases in violent incidents towards healthcare staff. However, this is difficult to illustrate because previously there was no clear definition, as well as considerable underreporting (Bibby 1995). The national media also focus heavily on serious incidents and often on individuals with mental health problems; however, it is important to be mindful of the stereotypes that can arise from this. Most people with mental health conditions are at greater risk of harming themselves than other people (Jones & Jackson 2004).

NHS Trusts have explicit strategies for reducing the number of violent incidents towards staff and systems for recording these events. Violence and aggression in the workplace have an immediate impact on individuals involved, their colleagues and also potential long-term consequences. Employers have a duty of care under the HSW Act (1974) (p. 326) to identify risks and take preventative measures. A risk assessment must involve all staff and key stages of the process (see p. 322). NHS Trusts must focus on specific areas including the environment, education provided to staff and methods of communication (DH 1999b).

Environment

The Department of Health (1999b) made a number of recommendations relating to clinical areas. Examining the environment in which care is delivered can identify factors that may trigger or contribute to aggressive or violent incidents (Box 13.24).

Box 13.24 Improving the healthcare environment to decrease violence

[From DH (1999b), RCN (2003a)]

Although creating a pleasant but safe patient/client environment is important (Box 13.25), this involves a balance between providing a friendly area and adequate security (National Audit Office 2003). In one department, protective glass screens actually increased tension for staff and clients and were therefore removed and replaced with other preventative measures (HSE 2004c).

Education

One of the key strategies for reducing violence towards healthcare staff is education to ensure that practitioners are aware of the safety issues and how to prevent or defuse a situation. Violence and aggression training is usually included in nursing programmes and is likely to involve the theory and practice of:

The training received by clinical staff and student nurses depends on the nature of the areas in which they will be working and the risk assessment results. In low-risk environments, e.g. operating theatres, staff training may include basic theory and de-escalation techniques. In high-risk areas, e.g. where challenging behaviour is common, or in mental health secure units, training will also usually include breakaway and restraint techniques.

The NHS Security Management Service (NHS SMS; www.cfsms.nhs.uk) was created in April 2003 with the policy and operational responsibility for the management of security within the NHS. NHS SMS has launched a comprehensive strategy to better protect staff and property in the NHS, with a particular emphasis on tackling violence. This replaces work previously undertaken under the NHS Zero Tolerance campaign.

Improving communication and preventing incidents

Safe nursing practice includes promoting effective communication between staff and patients/clients at all times (Ch. 9). Observation and interpersonal skills are often the key to preventing or defusing a situation by firstly looking for verbal and non-verbal cues that suggest that people may be agitated (Box 13.26).

Box 13.26 Verbal and non-verbal cues that suggest that people are agitated

[From Mason & Chandley (1999), RCN (2003a)]

Awareness of factors that can predispose people to violence and aggression (p. 339) is useful. Mason and Chandley (1999) remind readers of the need to be mindful of stereotypes and prejudices that may arise. For example, not everyone with dependence on alcohol or mental distress becomes violent, and external appearances, e.g. tattoos, piercing, do not represent particular attitudes or behaviours.

Interpersonal skills and non-verbal behaviour can help to resolve situations and prevent them from escalating. Key to all situations is the need to maintain respect and dignity for the people involved and to appear calm and confident (Mason & Chandley 1999). Box 13.27 identifies good practices that may help to prevent or de-escalate a situation.

[Based on Bibby (1995), DH (1999b), Mason & Chandley (1999), RCN (2003a)]

Preventing and de-escalating potentially violent situations

If more critical situations arise, these principles still apply and a confident, calm approach is still needed although it may not be appropriate to intervene. When possible, withdraw from the situation and think about moving other people away from the area too. Being aware of the environment you work in is also important – knowing how to summon help (e.g. other members of staff, security, police) and the general layout of the area along with the exit points. Avoid talking to people in confined spaces or corners if you recognize that a situation may become hostile. It is a good idea to suggest that all concerned move into a more suitable area to discuss the issue. Communication between staff is equally important to ensure everyone’s safety. Always inform staff when you are leaving a clinical area, where you will be and when you will return. This is good practice so that if an emergency occurs, e.g. fire or cardiac arrest, colleagues are aware of your location.

Staff working in the community may have specific needs as they usually work individually or as part of a small team. Risk assessments are still carried out, as in other clinical areas, and specific arrangements made for times when practitioners are out on duty. This should include the use of mobile phones to keep in contact, a system of informing other staff where they are and the approximate time they expect to return. The NHS Security Management Service (2003) introduced a pilot scheme for community staff where they carry identity cards with built-in mobile phone technology. If staff feel threatened they can press a button on the back that covertly records interactions, which can later be used as evidence, and a device that allows their whereabouts to be located in emergencies. Other arrangements may include a ‘buddy’ system where two members of staff are present during the initial client assessment or it may take place in a local clinic (DH 1999c).

Communication between agencies such as emergency departments, police, GPs and social services is also important. The RCN and NHS Executive (1998) describe a case where a district nurse was requested to visit a patient in their home to re-dress a dog bite wound. The gentleman’sGP notes revealed reports from the emergency depart-ment recording several attendances there following dogbites from his son’s bull terrier and also after being involvedin fights. Social services documentation revealed that his grandchildren were also on the Child Protection Register. As a result of the communication between agencies, the district nurse arranged wound care at the health centre rather than visiting him at home and advised the gentleman to return to the emergency department for out-of-hours care if necessary in order to maintain her own safety.

Dealing with and reporting violent incidents

Much of the discussion on violence and aggression has dealt with preventing incidents and defusing or de-escalation. Unfortunately, because of the complex nature of violence it can still occur despite the use of these techniques. The actions required in these incidents focuses on the immediate responses and then detailed follow-up and evaluation (RCN 2003a).

Immediate responses involve dealing with the emotional and physical needs of the practitioner(s) affected. In the case of violent assault, this may mean first aid and people usually experience a range of emotional reactions. This could include a ‘crisis’ phase where people feel shocked and numb but after the adrenaline has subsided, they feel physically and mentally exhausted (RCN 2003a). People need to feel that they are not alone when incidents have happened and healthcare organizations should have support mechanisms in place for staff who have experienced violence. This may include debriefing sessions for staff and patients/clients involved to make sense of events, long-term counselling and follow-up.

An important part of the evaluation is documenting and reporting aggressive and violent incidents using appropriate documentation so that follow-up action can be taken, hopefully preventing further incidents. However, staff may not want to document incidents for a number of reasons. These were highlighted by the National Audit Office (2003) who found that some staff thought:

A number of campaigns and education programmes aimed to address these concerns have highlighted that violence and aggression are not acceptable and do not reflect upon either the individual concerned or their skills.

Details of incident documentation include:

It may also be necessary to complete health and safety forms associated with RIDDOR. Given the emotional nature of events, the person completing the form should always receive help from senior staff to recall and document the incident (RCN 2003a). It may also be appropriate to inform the police.

The continued care of someone who has become violent is often not considered. They too may be shocked and upset by their behaviour and may wish to discuss the event from their perspective (RCN 2003a). Agreements can be drawn up between patients/clients and healthcare organizations regarding anti-social behaviour, discussing terms and conditions under which they will receive healthcare. These written agreements may mean that care is withdrawn if violent behaviour continues; however, it must always be made clear that it is the behaviour that is being rejected, not the person (Taylor 2000).

In extreme circumstances, e.g. a client is seriously endangering their own safety or that of others, other methods may be used to protect them and others. In specialist areas such as forensic mental health nursing, ‘time out’ and seclusion are used for short periods to help divert aggressive behaviour, reduce sensory stimuli, encourage internal control and disrupt the source of provocation (Mason & Chandley 1999).

However, if more extreme measures are employed, such as observation and restraint, healthcare providers must have clear policies regarding their use and practitioners involved require specialist training. These techniques remain controversial because they prevent a person doing what they want to do, restrict their liberty and, when used inappropriately, can be considered a breach of human rights and abuse (NMC 2002, RCN 2004). Unfortunately, people have also been injured or have died during physical restraint, which has led to a number of investigations and recommendations for practice.

Where techniques such as observing people at regular intervals (see Box 13.28) are used because people have become aggressive or are at risk of suicide, the emphasis is on a therapeutic intervention (rather than a custodial approach) and encouraging positive interactions. A balance needs to be struck between ensuring people’s safety and maintaining their privacy, dignity and autonomy (Jones & Jackson 2004).

Close observation

Lucy McFarland is 22 years old and has been treated for severe depression for 6 years. She has been admitted to an acute mental health unit after a second attempt to take her own life with an overdose of antidepressants. With Lucy’s agreement, staff searched her belongings to remove any articles she may use to harm herself and have been maintaining close observation. This means that staff check her activities every 15 minutes and she is not allowed to leave the unit unaccompanied. This duty is shared by several staff who rotate hourly. The ward is often short staffed and regularly employs agency staff which means that Lucy often does not know the nurse observing her.

Restraint

Restraint is a technique that also raises issues of human rights (see Ch. 6) and its use requires careful thought about safety issues. Restraint can include a wide range of explicit and subtle controls such as bedrails (Box 13.29), medication, locked doors, stair gates, arranging furniture to impede movement, controlling language or body language or withdrawal of aids such as walking frames or spectacles (RCN 2004). Most of these practices are unethical and solutions to safety issues must be found that do not affect people’s dignity and independence (see Ch. 7). RCN (2004) guidelines contain a range of strategies for nurses working with older adults, including investigating physical causes of behaviour changes, e.g. dehydration, urinary tract infection, hunger and thirst.

Box 13.29 Risk assessment: safety rails

Safety rails (also known as bed rails or cot sides) are used in hospitals, people’s homes and care homes when people, of all ages, are at high risk of falling out of bed. However, they can also be a source of injury and people have climbed over the top and fallen or become trapped between the bars and asphyxiated. Therefore their use needs careful consideration and the following points are based on guidance from the Medical Devices Agency (2001), now merged with the Medicines Control Agency.

Risk assessment

The RCN (2003b) also published guidance for nurses regarding the restraint of children and young people, particularly for painful procedures. Chapter 7 discusses the ethical issues surrounding restraint in clinical practice in more depth.

Careful consideration needs to be given to the types of situation where restraint (overt or hidden) or seclusion and observation can be used, assessing the risk to the person and their human rights (Box 13.30).

Restraint

Terrance Thornton is an 83-year-old man who has developed dementia and has recently moved into a residential home. He is confused in his new surroundings, especially at night when he has been becoming agitated, shouting at staff and prone to wandering. Care home staff installed safety rails to stop him getting out of bed but as a result he is unable to go to the toilet independently. Staff insist on providing continence pads when helping Mr Thornton to get ready for bed.

Fire safety

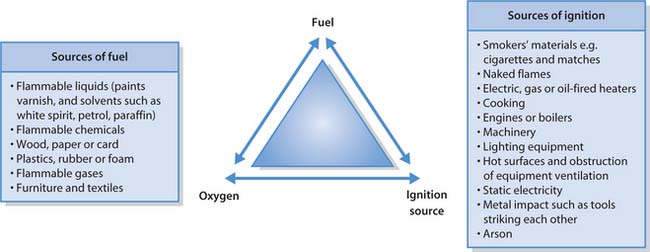

Fire represents one of the greatest hazards to people’s safety with potentially devastating consequences. There need to be three ingredients for a fire to start:

Removing any one of these ingredients means that a fire cannot start and, by lowering the chances of the three coming together, the risk from fires is reduced.

Similar to many other safety issues, legislation (Fire Precautions Act 1971 and Fire Regulations 1992 and 1997) aims to prevent fires by ensuring that employers:

In addition, all healthcare premises must obtain a Certificate of Firecode Compliance to ensure that they have met all current regulations.

Fire risk assessment

A fire risk assessment must identify all the fire hazards (e.g. sources of fuel, ignition) and the people at significant risk, especially those who have impaired mobility, sight or hearing. This information is used to identify improvements needed and to formulate an emergency evacuation plan (Home Office et al 1999).

Fire detection and warning systems

All large buildings must have fire detection systems that trigger an alarm system or alarms that can be activated at fire points, usually by breaking the safety glass. There may be different fire alarm sounds, e.g. continuous for the immediate area and intermittent for other sections, so it is important to know the local arrangements.

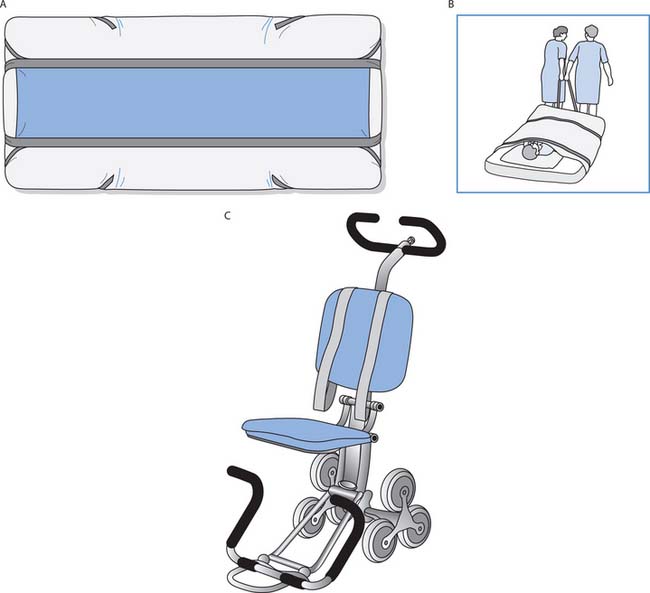

Emergency plans and means of escape

Hospitals are often organized into compartments that provide fire-resistant walls, ceilings and floors for a specified period of time. This reduces damage to buildings and increases survival rates, as initial evacuation is usually horizontal into the next compartment rather than down stairs (Home Office et al 1999). Emergency plans should discuss evacuation of people of differing mobility and availability of equipment such as evacuation chairs and ski sheets for immobile people on mattresses (see Fig. 13.9). Local training enables you to understand the arrangements for specific placements.

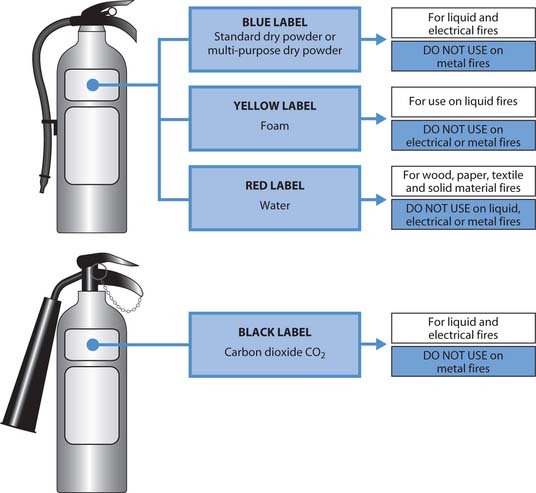

Facilities for fighting fire

Healthcare premises must provide facilities for fighting fires such as sprinkler systems and hose reels. In addition, fire extinguishers and fire blankets are located in appropriate areas such as kitchens so that people who have been trained to use them can tackle small fires. Figure 13.10 illustrates the different types of fire extinguisher.

Fire safety training

This section has introduced the basic principles of fire safety but within your nursing programme and throughout your career, fire training should be undertaken annually. This ensures that you are aware of local procedures, any new changes and can rehearse emergency situations. Carrying out the activities in Box 13.31 will highlight your fire safety awareness.

Fire safety

Student activities

Consider an area of your college or university that you visit regularly and find out:

In each new placement, it is essential to familiarize yourself with the locations of fire points and read the fire action notices that give instructions. You should also:

| BackCare | www.backcare-helpline.org/index2.php |

| Available July 2006 | |

| British Red Cross | www.redcrossfirstaidtraining.co.uk |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Department of Health | www.nhs.uk/backinwork |

| Back in Work – moving and handling in the NHS | Available July 2006 |

| Counter Fraud and | http://www.cfsms.nhs.uk/ |

| Security Management | Available July 2006 |

| Service (CFSMS) – replaced the Department of Health zero tolerance campaign in 2003 | |

| Health and Safety Executive | www.hse.gov.uk |

| Available July 2006 | |

| National Patient Safety Agency | www.npsa.nhs.uk |

| Available July 2006 | |

| NPSA Patient Safety e-learning programme | www.npsa.nhs.uk/health/resources/ipsel |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents | www.rospa.com |

| Available July 2006 | |

| St Andrew’s Ambulance Association – various regional addresses and telephone numbers | www.rstaid.org.uk |

| Available July 2006 | |

| St John Ambulance | www.sja.org.uk |

| Available July 2006 |

Alaszewski A, Alaszewski H. Risk: empowerment and control. In: Alaszewski A, Alaszewski H, Ayer S, Manthorpe J, editors. Managing risk in community practice: nursing, risk and decision-making. Edinburgh: Baillière Tindall/RCN, 2000.

Bibby P. Personal safety for health care workers. Aldershot: Arena, 1995.

Department of Health. Saving lives: our healthier nation. London: TSO, 1999.

Department of Health. Managers’ guide – stopping violence against staff working in the NHS. London: DH, 1999.

Department of Health. Managing violence in the community. London: DH, 1999.

Department of Health. Back in work campaign. London: DH, 2002.

Department of Health. Choosing health: making healthy choices easier. London: DH, 2004.

Department of Trade and Industry. 24th (final) annual report of the home and leisure accident surveillance system: 2000–2002 data. London: DTI, 2003.

Dimond B. Legal aspects of first aid and emergency care: 2. British Journal of Nursing. 1993;2(13):692-694.

Fowler A. The assessment and classification of non-complex burn injuries. Nursing Times. 2003;99(25):46-47.

Health and Safety at Work Act. London: HMSO, 1974.

Health and Safety Commission. 2004 Comprehensive injury statistics in support of the revitalizing health and safety programmes: health services. Online: http://www.hse.gov.uk/statistics/industry/index.htm. Available September 2006

Health and Safety Executive. 2000 Simple guide to the Lifting Operations and Lifting Equipment Regulations 1998. HSE, Sudbury. Online: www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/index.htm.

Health and Safety Executive. Simple guide to the Provision and Use of Work Equipment Regulations 1998. Sudbury: HSE, 2002.

Health and Safety Executive. Five steps to risk assessment. Sudbury: HSE, 2003.

Health and Safety Executive. Health and safety regulation: a short guide. Sudbury: HSE, 2003.

Health and Safety Executive. COSHH: a brief guide to the regulations. Sudbury: HSE, 2003.

Health and Safety Executive. 2004a HSE statistics. Online: http://www.hse.gov.uk/statistics/index.htm. Available July 2006.

Health and Safety Executive. Manual handling: guidance on regulations. Norwich: HSE Books, 2004.

Health and Safety Executive. Violence at work: a guide for employers. Sudbury: HSE, 2004.

Home Office, Scottish Executive, Department of Environment (Northern Ireland) and Health and Safety Executive. Fire safety: an employer’s guide. London: TSO, 1999.

Horton R, Parker L. Informed infection control practice, 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2002.

International Council of Nurses. 2004 The ICN definition of nursing. Online: http://www.icn.ch/definition.htm. Available July 2006

Jacobs L. An analysis of the concept of risk. Cancer Nursing. 2000;23(1):12-19.

Johnson C. manual handling risk assessment – theory and practice. In Smith J, editor: The guide to the handling of people, 5th edn, Teddington: BackCare, 2005.

Jones J, Jackson A. Observation. In: Harrison M, Howard D, Mitchell D, editors. Acute mental health nursing: from acute concerns to capable practitioner. London: Sage, 2004.

Lawrence JC. First-aid measures for the treatment of burns and scalds. Journal of Wound Care. 1996;5(7):319-322.

Mason T, Chandley M. Managing violence and aggression: a manual for nurses and health care workers. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1999.

Medical Devices Agency. Advice on the safe use of bed rails. London: MDA, 2001.

Mohun J, John K, Lee T, editors. First aid manual, 8th edn, London: Dorling Kindersley, 2002.

National Audit Office. A safer place to work: protecting NHS hospital and ambulance staff from violence and aggression. London: TSO, 2003.

National Health Service Security Management Service. 2003 Using technology to protect staff. Online: http://www.cfsms.nhs.uk.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. 2004 Falls: the assessment and prevention of falls in older people. Online: http://www.nice.org.uk. Available September 2006

National Patient Safety Agency. 2004 Alerts and advice. Online: www.npsa.nhs.uk.

Nursing and Midwifery Council. Practitioner–client relationships and the prevention of abuse. London: NMC, 2002.

Nursing and Midwifery Council. The code of professional conduct: standards for conduct, performance and ethics. London: NMC, 2004.

Royal College of Nursing. Dealing with violence against nursing staff: an RCN guide for nurses and managers. London: RCN, 2003.

Royal College of Nursing. Restraining, holding still and containing children and young people. London: RCN, 2003.

Royal College of Nursing. Restraint revisited – rights, risk and responsibility: guidance for nursing staff. London: RCN, 2004.

Royal College of Nursing and National Health Service Executive. Safer working in the community: a guide for NHS managers and staff in reducing the risks from violence and aggression. London: RCN, 1998.

Taylor D. Student preparation in managing violence and aggression. Nursing Standard. 2000;12(14):39-41.

United Kingdom Central Council for Nurses, Midwives and Health Visitors. Guidelines for mental health and learning disabilities nursing. London: UKCC, 1998.

Wilson J. Infection control in clinical practice, 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Baillière Tindall, 2001.

BackCare. Safer handling of people in the community. Teddington: BackCare, 1999.

BackCare and Royal College of Nursing. The guide to the handling of people, 5th edn. Teddington: BackCare, 2005.

Health and Safety Executive. Violence and aggression to staff in the health services: guidance on assessment and management. Norwich: HSE Books, 1997.

Hockenberry MJ, Wilson D, Winkelstein ML, et al. Wong’s nursing care of infants and children, 7th edn. St Louis: Mosby, 2003.

Horton R, Parker L. Informed infection control practice, 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2002.

Mason T, Chandley M. Managing violence and aggression: a manual for nurses and health care workers. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1999.

Waugh A, Grant A. Ross and Wilson anatomy and physiology in health and illness, 10th edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2006.

REFLECTIVE PRACTICE

REFLECTIVE PRACTICE CRITICAL THINKING

CRITICAL THINKING

HEALTH PROMOTION

HEALTH PROMOTION

FIRST AID

FIRST AID

NURSING SKILLS

NURSING SKILLS