58 Lifestyle drugs and drugs in sport

Overview

The term lifestyle drugs refers to an eclectic group of drugs that are used for non-medical purposes. It includes drugs of abuse, drugs used to enhance athletic or other performance, as well as those taken for cosmetic purposes or for purely social reasons. Alcohol, nicotine and various abused drugs are covered in Chapter 48. Many lifestyle drugs are also used as conventional therapeutics and the pharmacology is dealt with elsewhere in this book. In this chapter, we present an overall summary of the classes of drugs that are used for non-medical purposes, and discuss some of the social and medicolegal problems associated with their growing use. Drugs, officially prohibited, that are used to enhance sporting performance represent a special category of lifestyle drugs. Once again, a wide range of agents are used for this purpose, and their pharmacological properties are described in other chapters. Here we discuss specific issues relating to their use in competitive sports.

What Is A Lifestyle Drug?

Lifestyle drugs is a term of fairly recent origin and not precisely defined. The most commonly accepted definition refers to a drug or medicine1 that is used to satisfy an aspiration or a non-health-related goal. Examples include the use of the antihypertensive minoxidil for treating baldness or sildenafil for erectile difficulties in the absence of underlying disease. Oral contraceptives, which clearly lie in the domain of mainstream medicine, should also be considered lifestyle drugs. The term is sometimes also used to describe medicines that are used to treat ‘lifestyle illnesses’, that is to say diseases that arise through ‘lifestyle choices’ such as smoking, alcoholism or overeating, and there are many other shades of meaning as well. Also included in the lifestyle category are food supplements and other related preparations that are taken by the general public from choice because of some claimed benefit, even when there is no good evidence that they are effective.

Classification of Lifestyle Drugs

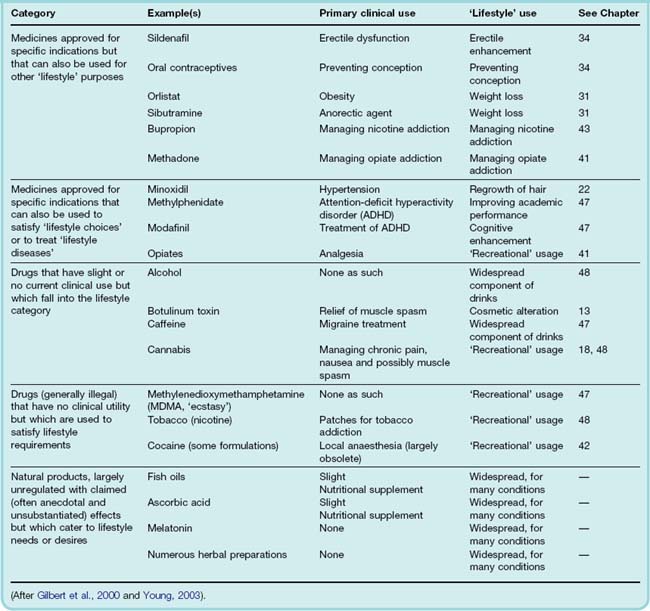

To classify all the different drugs or medicines that might fall into the lifestyle category, and provide a standard universally acceptable definition, is therefore difficult, and cuts across the pharmacological classification used throughout this book. The classification scheme summarised in Table 58.1 is based largely on the work of Gilbert et al. (2000) and Young (2003). This scheme embraces drugs that have been used for lifestyle choices based on historical precedent, such as oral contraceptives, as well as agents used to manage potentially debilitating lifestyle illnesses such as addiction to smoking (e.g. bupropion). It also includes drugs such as caffeine and alcohol that are consumed on a mass scale around the world, and drugs of abuse such as cocaine as well as nutritional supplements. Particularly controversial are drugs aimed at improving intellectual performance, such as modafinil and methylphenidate (Ch. 47), that are gaining favour as a route to academic success.2

Drugs can, over time, switch from ‘lifestyle’ to ‘mainstream’ use. For example, atropine (Ch.13) was first used as a beauty aid based on its ability to dilate the pupil. Cocaine was first described as a lifestyle drug in use by the South American Indians. Early explorers commented that it ‘satisfies the hungry, gives new strength to the weary and exhausted and makes the unhappy forget their sorrows’. Subsequently assimilated into European medicine as a local anaesthetic (Ch. 42), it is now largely returned to lifestyle drug status and, regrettably, is the basis of an illegal multimillion dollar international drugs industry. Cannabis is another good example of a drug that has been considered (in the West at least) as a purely recreational drug but which is now (as tetrahydrocannabinol) in trial for various clinical uses (see Chs 18 and 48).

Many widely used lifestyle ‘drugs’ or ‘sports supplements’ consist of natural products (e.g. ginkgo extracts, melatonin, St John’s wort, cinchona extracts), whose manufacture and sale has not generally been controlled by regulatory bodies.3 Their composition is therefore highly variable, and their efficacy and safety generally untested. Many contain active substances that, like synthetic drugs, can produce adverse as well as beneficial effects.

Lifestyle drugs ![]()

Drugs in Sport

The use of drugs to enhance sporting performance4 is evidently widespread although officially prohibited. The World Anti-Doping Agency (http://www.wada-ama.org), which was established partly in response to some high-profile doping cases and drug-induced deaths among athletes, publishes an annually updated list of prohibited substances that may not be used by sportsmen or sportswomen either in or out of competition. Drug testing is based mainly on analysis of blood or urine samples according to strictly defined protocols. The chemical analyses, which rely mainly on gas chromatography/mass spectrometry or immunoassay techniques, must be carried out by approved laboratories.

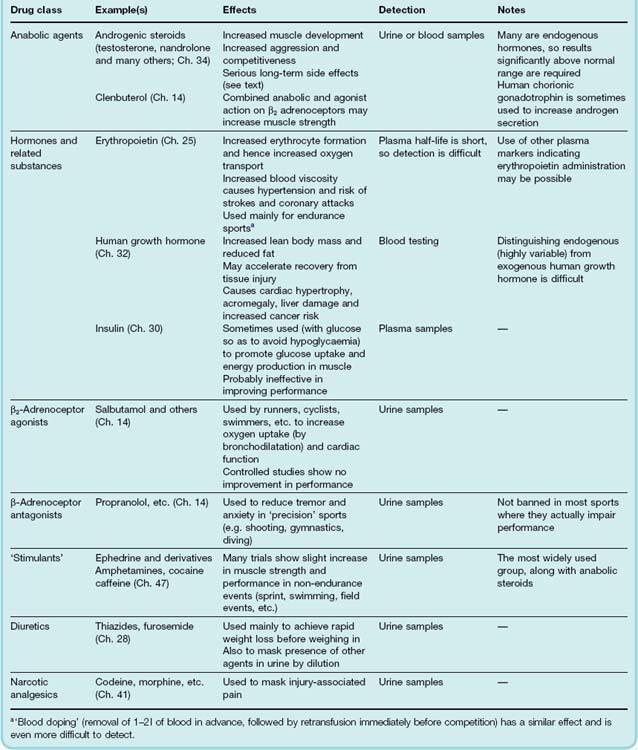

Table 58.2 summarises the main classes of drugs that are prohibited for use in sports. Athletes are easily persuaded of the potential of a wide variety of drugs to increase their chances of winning, but it should be emphasised that in very few cases have controlled trials shown that the drugs actually improve sporting performance among trained athletes, and indeed many such trials have proved negative. However, marginal improvements in performance (often 1% or less), which are difficult to measure experimentally, may make the difference between winning and losing, and the competitive instincts of athletes and their trainers generally carry more weight than scientific evidence.

A brief account of some of the more important drugs in common use follows. For a broader and more complete coverage, see British Medical Association (2002) and Mottram (2005).

Anabolic Steroids

Anabolic steroids (Ch. 34) include a large group of compounds with testosterone-like effects, including about 50 named compounds on the prohibited list. New chemical derivatives (‘designer steroids’) such as tetrahydrogestrinone (THG) are regularly developed and offered illicitly to athletes, which represents a continuing problem to the authorities charged with detecting and identifying them. A further problem is that some of these drugs are endogenous compounds or their metabolites, making it difficult to prove that the substance had been administered illegally. Isotope ratio techniques, based on the fact that endogenous and exogenous steroids have slightly different 12C:13C ratios, may enable the two to be distinguished analytically.

Anabolic steroids produce long-term effects and are normally used throughout training, rather than during competition, so out-of-competition testing is necessary.

Although anabolic steroids, when given in combination with training and high protein intake, undoubtedly increase muscle mass and body weight, there is little evidence that they increase muscle strength over and above the effect of training, or that they improve sporting performance. On the other hand, they have serious long-term effects, including male infertility, female masculinisation, liver and kidney tumours, hypertension and increased cardiovascular risk, and in adolescents premature skeletal maturation causing irreversible cessation of growth. Anabolic steroids produce a feeling of physical well-being, increased competitiveness and aggressiveness, sometimes progressing to actual psychosis. Depression is common when the drugs are stopped, sometimes leading to long-term psychiatric problems.

Clenbuterol, a β-adrenoceptor antagonist (see Ch. 14), has recently come into use by athletes. Through an unknown mechanism of action, it produces anabolic effects similar to those of androgenic steroids, with apparently fewer adverse effects. It can be detected in urine and is banned for use in sport.

Human Growth Hormone

The use of human growth hormone (hGH; see Ch. 32) by athletes followed the availability of the recombinant form of hGH, used to treat endocrine disorders. It is given by injection and its effects appear to be similar to those of anabolic steroids. hGH is also reported to produce a similar feeling of well-being, although without the accompanying aggression and changes in sexual development and behaviour. It increases lean body mass and reduces body fat, but its effects on muscle strength and athletic performance are unclear. It is claimed to increase the rate of recovery from tissue injury, allowing more intensive training routines to be followed.

The main adverse effect of hGH is the development of acromegaly, causing overgrowth of the jaw and thickening of the fingers (Ch. 32), but it may also lead to cardiac hypertrophy and cardiomyopathy, and possibly also an increased cancer risk.

Detection of hGH administration is difficult because physiological secretion is pulsatile, so normal plasma concentrations vary widely. The plasma half-life is short (20–30 min), and only trace amounts are excreted in urine. However, secreted hGH consists of three isoforms varying in molecular weight, whereas recombinant hGH contains only one, so measuring the relative amounts of the isoforms can be used to detect the exogenous material.

Growth hormone acts partly by releasing insulin-like growth factor from the liver, and this hormone itself is coming into use by athletes.

Another hormone, erythropoietin, which increases erythrocyte production (see Ch. 25) is given by injection for days or weeks to increase the erythrocyte count and hence the O2-carrying capacity of blood. The development of recombinant erythropoietin has made it widely available, and detection of its use is difficult. It carries a risk of hypertension, neurologic disease and thrombosis.

Stimulant Drugs

The main drugs of this type used by athletes and officially prohibited are ephedrine and methylephedrine; various amphetamines and similar drugs, such as fenfluramine and methylphenidate;5 cocaine; and a variety of other CNS stimulants such as nikethamide, amiphenazole (no longer used clinically) and strychnine (see Ch. 47). Caffeine is also used: some commercially available ‘energy drinks’ contain taurine as well as caffeine. However, taurine is an agonist at glycine and extrasynaptic GABAA receptors (see Ch. 38). Its effects on the brain are therefore likely to be inhibitory rather than stimulatory. In this regard, taurine may be responsible for the post-energy-drink low that is experienced once the stimulatory effect of caffeine has worn off.

In contrast to steroids, some trials have shown these drugs to improve performance in events such as sprinting and weightlifting, and under experimental conditions they increase muscle strength and reduce muscle fatigue significantly. The psychological effect of stimulants is probably more relevant than their physiological effects. Surprisingly, caffeine appears to be more consistently effective in improving muscle performance than other more powerful stimulants.

Several deaths have occurred among athletes taking amphetamines and ephedrine-like drugs in endurance events. The main causes are coronary insufficiency, associated with hypertension; hyperthermia, associated with cutaneous vasoconstriction; and dehydration.

Drugs in sport ![]()

The recent lifestyle drugs debate is one aspect of the broader long-standing question of what actually constitutes ‘disease’ and how far medical science should go in attempting to alleviate human distress and dysfunction in the absence of pathology, or to satisfy the needs and aspirations of otherwise healthy individuals. Discussion of these issues is beyond the scope of this book but can be found in articles cited at the end of this chapter (see Smith, 2002).

There are several reasons why the lifestyle drug phenomenon—no matter how we choose to define it—is of increasing concern. The increasing availability drugs from Internet ‘e-pharmacies’, coupled with direct advertising by the pharmaceutical industry to the public that occurs in some countries, will ensure that demand is kept buoyant, and the pharmaceutical sector will undoubtedly develop more lifestyle agents. The lobbying power of patients advocating particular drugs, regardless of the potential costs or proven utility, is causing major problems for drug regulators and those who set healthcare priorities for state-funded systems of social medicine. The use of drugs that improve short-term memory to treat patients with dementia (Ch. 39) is generally seen as desirable (even though current drugs are only marginally effective). Extending the use of existing and future drugs to give healthy children and students a competitive advantage in tests is much more controversial. Further off is the prospect of drugs that retard senescence and prolong life—another social and ethical minefield in an overpopulated world.

From a pharmacological perspective, it is fair to say that the use of drugs to enhance sporting performance carries many risks and is of very doubtful efficacy. Its growing prevalence reflects many of the same pressures as those driving the introduction of lifestyle drugs, namely the desire to improve on human attributes that are not impaired by disease, coupled with disregard for scientific evidence relating to efficacy and risk.