The Child with Cognitive, Sensory, or Communication Impairment

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Wong/ncic/

Auditory Testing, Ch. 6

Dental Health: Toddler, Ch. 14; School-Age Child, Ch. 17

Developmental Assessment, Ch. 6

Family-Centered Care of the Child with Chronic Illness or Disability, Ch. 22

Family-Centered Home Care, Ch. 25

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder, Ch. 10

Hereditary Influences on Health Promotion of the Child and Family, Ch. 5

Human Immunodeficiency Virus Encephalopathy, Ch. 37

Limit Setting and Discipline, Ch. 3

Optic, Otic, and Nasal Administration (of Medication), Ch. 27

Otitis Media, Ch. 32

Play: Infant, Ch. 12; Toddler, Ch. 14; Preschooler, Ch. 15; School-Age Child, Ch. 17

Preparation for Hospitalization, Ch. 26

Toilet Training, Ch. 14

Vision Testing, Ch. 6

Cognitive Impairment

Cognitive impairment (CI) is a general term that encompasses any type of intellectual disability. The term intellectual disability is increasingly being used instead of mental retardation (Schalock, Luckasson, Shogren, et al, 2007). In this chapter CI is used synonymously with intellectual disability and the outdated term mental retardation. Although the family’s needs and concerns are a primary focus throughout the chapter, the reader should review Chapter 22, which details the family’s adjustment to disabilities in general.

The definition of intellectual disability developed by the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD), formally known as American Association on Mental Retardation, includes diagnostic criteria that place increased emphasis on the child’s functional strengths and weaknesses and the environmental supports the child needs (Schalock, Luckasson, Shogren, et al, 2007; Wehmeyer, Buntinx, Lachapelle, et al, 2008). Classification using the AAIDD definition requires a description of intellectual functioning and functional strengths and weaknesses in a number of real-world adaptive skills; onset of the condition must be before 18 years of age. The child must manifest subaverage intellectual functioning, which in practical terms means an intelligence quotient (IQ) of 70 to 75 or below. In addition, the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition, text revision (DMS-IV-TR), which is the diagnostic standard, states that the child with CI (intellectual disability) must demonstrate functional impairment in at least two of the following adaptive skill domains: communication, self-care, home living, social skills, use of community resources, self-direction, health and safety, functional academics, leisure, and work (American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

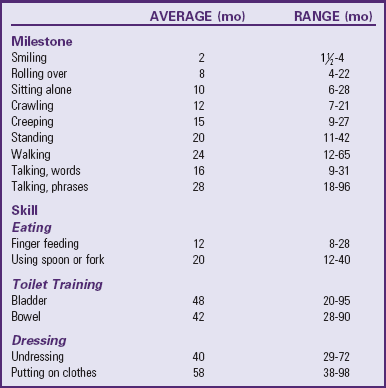

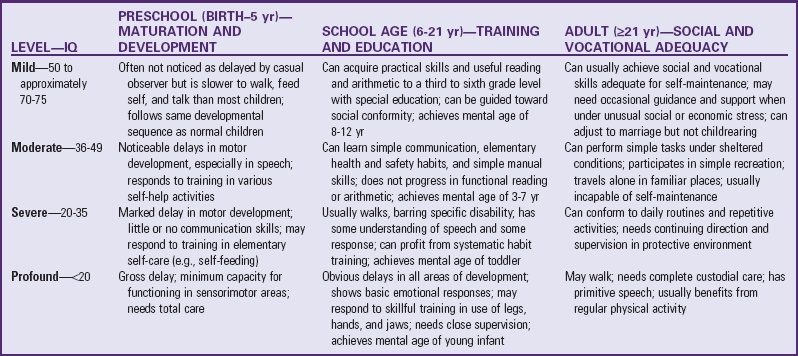

The AAIDD definition of CI (intellectual disability) emphasizes abilities, environments, supports, and empowerment. The intensity of support required is classified as intermittent, limited, extensive, or pervasive. The underlying assumption is that when appropriate supports are given over a prolonged period, the ability of the person with CI to function each day will generally improve. For educational purposes, the mildly impaired group encompasses about 85% of all people with CI, and the children with moderate levels of CI account for about 10% of the intellectual disabled population (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; Johnson and Walker, 2006) (Table 24-1).

TABLE 24-1

CLASSIFICATION OF COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT

Data modified from American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV-TR), ed 4, text rev, Washington, DC, 2000, The Association; and Rittey CD: Learning difficulties: what the neurologist needs to know, J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 74(Suppl 1):30-36, 2005.

The central role of the family in caring for the child with CI cannot be overlooked. Principles of family-centered care are key. (See Chapters 6, 22, and 25.) Nurses are instrumental in helping to socialize families of children with CI toward a collaborative model of care, which is critical in efforts to teach these children functional skills.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of CI is usually made after a period of suspicion by professionals or the family that the child’s developmental progress is delayed. In some cases it is made at birth when distinct syndromes such as Down syndrome are recognized, or when severe to profound delays in development are apparent. At the other extreme, it may be made after the child begins school and does poorly. In all cases a high index of suspicion for developmental disability is necessary for early diagnosis, and routine developmental screening can assist in early identification. (See Chapter 6.) Delays occur most commonly in language and cognitive skills, although delays in fine and gross motor skills are also typical. Developmental disability can be described as any significant lag or delay in a child’s physical, cognitive, behavioral, emotional, or social development, when compared against developmental norms. CI is an impairment encompassing intellectual ability and adaptive behavior that are functioning significantly below average.

Results of standardized tests are helpful in making the diagnosis of CI. The most commonly used test for infants is the Bayley Scales of Infant Development, although the Mullen Scales of Early Learning is also used for this population. (See also Chapter 6.) The Harris Infant Neuromotor Test (HINT) is another valid and reliable screening tool for identification of potential motor and cognitive developmental disorders in infants. A recent study suggested that the HINT norms developed from the data collected from Canadian infants may be applicable to U.S. infants (McCoy, Bowman, Smith-Blockley, et al, 2009). During the school years the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, fourth edition, is most often used. The Differential Ability Scales, Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale, and Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children are additional tests that can be used from toddlerhood through school age. Specialized tests such as the Leiter International Performance Scale, revised edition, can be useful for assessing children who speak a different language, nonverbal children, or those with significant language or motor impairment. All of these tests are individually administered (never given as a group test) in a standardized manner under favorable conditions by specially trained clinicians, such as psychologists, psychometrists, or child development specialists. Tests for assessing adaptive behavior functioning include the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales and the AAMR Adaptive Behavior Scale. Informal appraisal of adaptive behavior may be made by those fully acquainted with the child (e.g., teachers, parents, or other care providers). Frequently these observations lead parents to seek a developmental evaluation.

When a family suspects a diagnosis of CI, it can be devastating. Nurses should take care to provide support from sensitive professionals at the time of diagnosis. (See Chapter 22.) Provide information to address any misconceptions and answer parental questions and concerns. Make referrals for counseling or additional information if appropriate or desired. Nurses can be an important resource as parents sort through an often confusing array of educational, health, and therapeutic services to determine how best to meet the needs of their child.

Etiology

The etiology of CI includes familial, social, environmental, organic, and unknown causes. Among individuals with severe CI, chromosomal disorders and prenatal toxin exposure are common, with Down syndrome, fragile X syndrome, and fetal alcohol syndrome accounting for a sizable proportion of cases. Other identifiable disorders or syndromes, such as severe cerebral palsy, microcephaly, or infantile spasms, are also associated with CI. Box 24-1 lists the prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal causes of CI.

Prevention

Currently there is much concern about prevention of CI. Primary prevention strategies—those designed to avoid conditions that cause CI—include avoidance of prenatal rubella infection; maintenance of current immunizations; genetic counseling, especially regarding risk of Down or fragile X syndrome; use of folic acid supplements during pregnancy to prevent neural tube defects; education regarding the dangers of smoking or ingesting alcohol during pregnancy and ingesting lead during childhood; adequate prenatal care and childhood nutrition; and reduction of head injuries. In the future, gene therapy for selected conditions will probably be a significant advance in preventing genetic disorders, such as phenylketonuria.

Secondary prevention activities—those designed to identify the condition early and initiate treatment to avert cerebral damage—include prenatal diagnosis or carrier detection of disorders such as Down syndrome and newborn screening for treatable inborn errors of metabolism, such as congenital hypothyroidism, phenylketonuria, and galactosemia.

Tertiary prevention strategies—those concerned with treatment to minimize long-term consequences—include early identification of conditions and provision of appropriate therapies and rehabilitation services. These include medical treatment of coexisting problems, such as hearing and visual impairment in Down syndrome, and programs for infant stimulation, parent training, preschool education, and counseling services to preserve the integration of the family unit.

Nursing Care of Children with Cognitive Impairment

![]() The goal of caring for children with CI is to promote their optimum social, physical, cognitive, and adaptive development as individuals within a family and community. General guidelines for coping with and adjusting to the child with special needs are in Chapter 22.

The goal of caring for children with CI is to promote their optimum social, physical, cognitive, and adaptive development as individuals within a family and community. General guidelines for coping with and adjusting to the child with special needs are in Chapter 22.

![]() Nursing Care Plan—The Child with Impaired Cognitive Function

Nursing Care Plan—The Child with Impaired Cognitive Function

Nurses play a major role in identifying children with CI. In the newborn and early infancy period, few signs are present, except in various syndromes that have distinctive features, such as Down syndrome. Delayed developmental milestones are the major clues to CI. In addition, nurses must have a high index of suspicion for early signs suggestive of CI (Box 24-2). Take parental concerns, such as delayed development compared with siblings, seriously. All children should receive regular developmental assessment, and the nurse is often the person responsible for performing such assessments. (See Chapter 6.) When delays are found, the nurse must use sensitivity and discretion in revealing this finding to parents.

Nurses play a role in developing and implementing the individualized education plan for each child with special needs in the school system and the individualized family service plan designed for the family and child with special needs in an early intervention program (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2000) (see Community Focus box).

Standards of care have been developed for physicians and nurses working with persons with developmental disabilities or CI (Lambros and Leslie, 2005; Ranweiler, 2009) and also for nurses working in early intervention programs. Nursing organizations concerned with developmental disabilities are listed in Box 24-3.

Educate the Child and Family

To teach children with CI, one must investigate their learning abilities and deficits. This is important for the nurse who may be involved in a home care type of program or who may be caring for the child in a school or health care setting. The nurse who understands how these children learn can effectively teach them basic skills or prepare them for various health-related procedures.

Children with CI have a marked deficit in their ability to discriminate between two or more stimuli because of difficulty in recognizing the relevance of specific cues. However, these children can learn to discriminate if the cues are presented in an exaggerated, concrete form and if all extraneous stimuli are eliminated. For example, the use of colors to emphasize visual cues or the use of singing or rhymes to stress auditory cues can help them learn. Their deficit in discrimination also implies that concrete ideas are much easier to learn effectively than abstract ideas. Therefore demonstration is preferable to verbal explanation, and the nurse should direct learning toward mastering a skill rather than understanding the scientific principles underlying a procedure.

Another cognitive deficit is in short-term memory. Whereas children of average intelligence can remember several words, numbers, or directions at one time, children with CI are less able to do so. Therefore they need simple one-step directions. Learning through a step-by-step process requires a task analysis, in which each task is separated into its necessary components and each step is taught completely before proceeding to the next activity (Box 24-4). Considerable repetition and review of new instructional information is important for long-term retention.

One critical area of learning that has had a tremendous impact on the education of cognitively impaired individuals is motivation, or the use of positive reinforcement to encourage the accomplishment of specific tasks or the development of specific behaviors. Two techniques are especially important with this group of learners: fading and shaping. Fading is physically taking the child through each sequence of the desired activity and gradually fading out physical assistance so that the child becomes more independent. Shaping is waiting for the child to give a response that approximates the desired behavior, then reinforcing successive approximations of the end goal through the use of praise or tangible reinforcers. Repetition plays an important part in learning. As the child gains mastery, reinforcement gradually decreases. Such principles are easy to implement in the home in teaching self-help skills. Maintaining feelings of success in accomplishing specified goals also promotes self-esteem in the child. If a learning program does not move forward successfully, both parent and nurse can reevaluate the last sequence the child mastered to see if they are expecting too much too soon.

When behavior modification is employed, it is crucial to reinforce desirable behavior, because it has a considerable impact on the education of the cognitively impaired child. Employing positive reinforcement for specific tasks or behaviors tends to enhance the child’s ability to learn.

Advances in technology have greatly assisted in providing reinforcement, especially for children who have severe CI and physical disabilities that limit their range of capabilities. For example, specially designed switches give children control of some event in the environment, such as turning on the computer (Fig. 24-1). Activation of the computer becomes reinforcement for pushing the switch. Repetitive use of these switches provides an early, simplistic association with a technical device that may progress to the use of increasingly complex aids.

Early intervention programs have been widely promoted for children with developmental disabilities, and there is considerable evidence that these programs are valuable for children with CI. Early intervention program is a systematic program of therapy, exercises, and activities designed to address developmental delays in disabled children to help achieve their full potentials (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2001a; Hartway, 2009a; National Down Syndrome Society, 2009d). Nurses working with families of disabled children need to be aware of the types of programs available in their community. Early intervention programs are provided by a number of organizations. Under Public Law 101-476, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 1990, states are encouraged to provide full early intervention services* and are required to provide educational opportunities for all children with disabilities from birth to 21 years of age. Early intervention services may be provided by each state, such as through programs for children with special health needs (formerly crippled children’s programs) or Head Start, or by private organizations such as Easter Seals† and the ARC of the United States (formerly the Association for Retarded Citizens of the United States).‡ Local school districts provide educational services that begin when the child reaches age 3 years. Parents should inquire about these programs by contacting the appropriate agencies. To promote optimum outcomes, education should begin as soon as possible, not at 5 or 6 years of age. As children grow older, their education can focus on vocational training that prepares them for as independent a lifestyle as possible within their scope of abilities (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2001a; Johnson, Kastner, and American Academy of Pediatrics, 2005; Shapiro and Batshaw, 2007).

Promote the Child’s Optimum Development

Optimum development requires appropriate guidance for establishing acceptable social behavior and personal feelings of self-esteem, worth, and security. These attributes are not simply learned through a stimulating program but must arise from the genuine love and caring that exists among family members. However, families may need guidance in providing an environment that fosters optimum development. Often it is the nurse who can provide assistance in these areas of childrearing.

Another important area for promoting optimum development and self-esteem is ensuring the child’s physical well-being. Any congenital defects, such as cardiac, gastrointestinal, or orthopedic anomalies, should be repaired. Plastic surgery may be considered when the child’s appearance can be substantially improved. Dental health is significant, and orthodontic and restorative procedures can immensely improve facial appearance.

Communication: Development of verbal skills is often delayed more than development of other physical skills. Speech requires adequate hearing and interpretation of sounds (receptive skills) and facial muscle coordination (expressive skills). Both receptive and expressive skills may be significantly impaired, so frequent audiometric testing should be conducted, and hearing aids should be provided to children with hearing difficulties. Other children may require training in controlling their facial muscles. For example, some children may need tongue exercises to correct tongue thrust or gentle reminders to keep the lips closed.

For some of these children, nonverbal methods of communication should be employed. The choice of an assistive device often depends on the child’s cognitive level and physical abilities. For the child without associated physical disabilities, a talking picture board is helpful. For children with physical limitations, several adaptations to and types of communication devices are available to facilitate selection of the appropriate picture or word. Some children may learn sign language or Blissymbolics, a system of graphic symbols representing words, ideas, and concepts. The symbols are typically arranged on a board, and the individual points or uses a selector to communicate a message.

Discipline: Discipline must begin early. Limit-setting measures must be simple, consistent, and appropriate for the child’s mental age. Control measures are based primarily on teaching a specific behavior, rather than on developing an understanding of the reasons behind it. Stressing moral lessons is of little value to a child who lacks the cognitive skills to learn from self-criticism and evaluation of previous mistakes. Behavior modification, especially reinforcement of desired actions and the use of time-out procedures, is an appropriate form of behavior control. (See Chapter 3.) Avoid aversive strategies.

Socialization: Acquisition of social skills is complex. Active rehearsal (with role playing and practice sessions) and positive reinforcement for desired behavior are successful approaches. Encourage parents early to teach their child socially acceptable behavior: waving good-bye, saying hello and thank you, responding to his or her name, and greeting visitors. The teaching of socially acceptable sexual behavior is especially important to minimize sexual exploitation. Parents also need to expose the child to strangers so that manners can be practiced, since transfer of learning from one situation to another is not automatic.

Social acceptance and self-esteem are enhanced when a child is appropriately dressed and well-groomed. Clean, stylish, well-fitting clothing that has self-adhering fasteners and elastic openings facilitates self-dressing and social acceptance.

Opportunities for social interaction and training should begin at an early age. Encourage parents to enroll their child in infant stimulation programs and other appropriate preschool programs as soon as possible. These programs provide education, training, and opportunities for social interaction with other children and adults.

As children grow older, they should have peer experiences similar to those of other children, including participation in group outings, sports, and organized activities such as scouts and Special Olympics. These children often enjoy participating in developmentally appropriate peer activities such as dance and karate classes (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2004; Rehm and Bradley, 2006; Shapiro and Batshaw, 2007). A close relationship with a best friend can be encouraged. Vacations, family outings, dances, and dating are important social opportunities.

Sexuality: Adolescence may be a particularly difficult time for parents, especially in terms of the child’s sexual behavior, possibility of pregnancy, future plans to marry, and ability to be independent. Often, minimal anticipatory guidance is available to parents to prepare the child for physical and sexual maturation, and the degree of the adolescent’s interest in and experience with sex has been underestimated.

The question of contraceptive protection for female adolescents is often a parental concern. Permanent contraception through sterilization is a special dilemma because of moral and ethical questions, as well as psychologic effects on the adolescent. State laws vary; some allow no sterilization, whereas others permit review of requests. Intramuscular injection of medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo-Provera) is a contraceptive choice that provides long-term protection, requires little compliance, and often produces amenorrhea.

Parents of these adolescents are often concerned about the advisability of marriage between two individuals with significant CI. There is no conclusive answer; each situation must be judged individually. In many instances marriage would help the couple achieve a mutually satisfying and supportive relationship, meaningful companionship, and a more normal social and sexual adjustment. Under the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, every individual has the right to marry and have a family, regardless of his or her mental capacity (Silber and Batshaw, 2004). The nurse should discuss this topic with parents and with the prospective couple, stressing the need for suitable living accommodations and use of appropriate contraceptive methods to prevent pregnancy. If children are conceived, these parents require specialized assistance and guidance in learning to meet the needs of their offspring (Johnson and Walker, 2006; Silber and Batshaw, 2004).

Nurses can help in this area by providing parents with information about sex education that is geared to the child’s developmental level. For example, the adolescent female needs a simple explanation of menstruation and instructions on personal hygiene during the menstrual cycle.*

These adolescents also need practical sexual information regarding anatomy, physical development, and conception. Because they are easy to persuade and lack judgment, they need a well-defined, concrete code of conduct with specific instructions for handling certain situations. Girls should know never to go alone anywhere with any person they do not know well. Boys should be warned of intimate advances from other males. Sexual assault of a cognitively impaired adolescent should be treated and investigated by law enforcement personnel (Eastgate, 2005).

Play and Exercise: Children who are cognitively impaired have the same need for play as any other children. Exercise is beneficial for development of coordination, cardiovascular fitness, and weight management. Because of the child’s slower development, however, parents may be less aware of the need to provide for such activities. They may also feel inadequate in playing with the child because the usual reciprocal interaction and resulting satisfaction between child and parent may be slower in developing.

In addition, children who are cognitively impaired may not be able to initiate appropriate play activities on their own. They may resort to self-stimulatory behavior, such as rocking, twirling, masturbating, or finger sucking, and self-injurious behaviors, such as head banging or biting, hitting, or scratching themselves (Murray, 2003; Shapiro and Batshaw, 2007). The nurse should inquire as to what precipitates the behaviors and review the parent’s techniques used to manage the behaviors (Johnson and Walker, 2006). The nurse may also guide parents toward selection of suitable toys and interactive activities (Fig. 24-2).

The type of play is based on the child’s developmental age, although the need for sensorimotor play may be prolonged. Parents should use every opportunity to expose the child to as many different sounds, sights, and sensations as possible. Appropriate toys include musical mobiles, stuffed toys, floating toys, a rocking chair or horse, a swing, bells, and rattles. The child should be taken on outings, such as trips to the grocery store or shopping center. Other people should visit in the home, and individuals should relate directly to the child, through such means as cuddling, holding, and talking to the child in the face-to-face position.

Parents should select toys for their recreational and educational value. For example, a large inflatable beach ball is a good water toy; encourages interactive play; and can be used to learn motor skills such as balance, rocking, kicking, and throwing. Attractive toys encourage a child to reach, thus assisting in the development of motor skills (Fig. 24-3). Musical toys that mimic animal sounds or respond with social phrases are excellent ways of encouraging speech. A doll with removable clothes and different types of closures can help the child learn dressing skills. Toys should be simple in design so that the child can learn to manipulate them without help. For children with severe cognitive or physical impairment, electronic switches can be used to allow them to operate toys (Fig. 24-4).

Fig. 24-3 Placing an attractive object outside of the child’s reach encourages crawling movements. (Courtesy James DeLeon, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston.)

Fig. 24-4 An electric switch allows a child with physical impairment to play with a battery-operated toy.

Suitable physical activity is based on the child’s size, coordination, physical fitness and maturity, motivation, and health. Some children may have physical problems that prevent participation in certain sports, such as atlantoaxial instability in children with Down syndrome. Children with CI often have greater success in individual and dual sports than in team sports and enjoy themselves most with children of the same developmental level. The Special Olympics* provides a unique competitive opportunity.

Safety is a major consideration in selecting recreational and exercise activities. Some toys that may be appropriate developmentally may present dangers to a child who is strong enough to break them or use them incorrectly.

Promote Independent Self-Help Skills

When a child with CI is born, parents often need assistance in promoting normal developmental skills that other children learn easily. There is no way to predict when a child should be able to master self-help skills; wide variability exists in the ages at which these children accomplish such functions (see Table 24-3). Parents need support, both as the primary caretakers and teachers of the child, and they need detailed written descriptions of a jointly developed training program. Parents should also receive information about commercially available devices that can aid in achievement of independence (Fig. 24-5).

Fig. 24-5 A child with cognitive and physical impairments can play a tape recorder by moving a device near her head.

Feeding: Self-feeding is the first major self-help skill that children learn. It involves the integration of fine and gross motor skills and visual perception. Most parents take for granted that they will be successful in teaching their children to feed themselves. Therefore the nurse and other team members must be especially sensitive to the needs of the parent, as well as the child, if assistance is offered.

Before beginning a self-feeding program, the nurse and parent should do a task analysis, breaking the process of feeding into its smallest components (see Box 24-4). It is important to observe the child in an eating situation to determine whether he or she has mastered any self-feeding skills.

Along with a task analysis, the nurse assesses a number of other factors, such as the shape of the child’s mouth and the child’s control of mouth, lip, and tongue movements (whether the tongue moves forward and backward or from side to side, whether there are rotary movements). The presence of teeth determines the textures and consistencies of foods that the child can eat. The child’s developmental readiness for self-feeding, such as the ability to maintain head and trunk support and to sit without support, the level of eye-hand coordination, the firmness of the grasp, and the ability to reach for an object, hold it, and release it, is examined. If the child has any physical impairments that interfere with holding or grasping the utensil, specially designed utensils can be substituted or homemade modifications can be used. For example, the handle can be built up with a sponge or piece of wood or bent to accommodate arm movement.

The nurse obtains further data from the parent by asking specifically about the family’s approach to feeding. For example, who feeds the child regularly? Is the child fed when hungry or according to a prescribed schedule? What are the child’s appetite patterns? Does the parent know when the child is full? What foods does the child like? How long does feeding take? A short feeding time, such as 10 minutes, might indicate that the child is being deprived of sensory experiences or appropriate interactions; a long time might indicate frustration and fatigue on the parent’s part. Is the feeding environment described as quiet and nondistracting? The nurse also helps determine the best time to begin teaching this new task. If the family is going on vacation, if someone is visiting, or if there has been a major stress in the family, this may not be the ideal time to begin a teaching program.

Also consider preparation for the feeding activity, such as proper placement of the child at the table and protection of the area against spills. Feeding should fit in with family life. (See Chapter 22.) For example, the child is fed in the kitchen, at the table, or in a high chair in a sitting position, and with other family members whenever possible. Food should be offered in separate servings, not pureed or mixed together; should be served at the appropriate temperature; and should be of sufficient variety and texture from each of the basic food groups.

Once the feeding program begins, the nurse is in an important position to give parents supportive feedback. The nurse acknowledges the parents’ observational skills and their ability to share observations, keep records of the child’s progress, and establish goals that are appropriate and realistic for both the child and the parents.

Toileting: Independent toileting is another major self-help skill that parents can teach using behavior modification principles. It usually begins after self-feeding because this is the normal sequence of development. Plans for a toileting program begin by assessing the child’s physical and psychologic readiness. (See Chapter 14.) Because of physical or developmental limitations, certain signals may not be possible. For example, children who cannot walk can be trained once they are able to sit with good balance, and children with poor speech may need to rely on hand gestures to signal their toileting needs.

Interview parents regarding their readiness to pursue a toilet-training program. Readiness is characterized by a positive, consistent, individualized, nonpunitive, nonpressured style of teaching. It is important to explore with parents the time they have to invest in the program, the advantages they see, the inconveniences that toilet training may cause them, the reason they wish to start, and whether this is the best time for both the parents and the child to begin.

Review any past attempts at toilet training the child: When and why did the parents start training? What methods did they use? Did they experience frustration, indifference, or discomfort? How long did they attempt training, and what were their reasons for discontinuing training efforts? Were their efforts consistent? Looking back, how did they view the experience for themselves and the child? If the parents acknowledge using punishment in any form, including spanking, scolding, withholding privileges, using suppositories, withholding fluid, or getting the child up in the middle of the night, the nurse offers positive alternatives.

As part of the procedure for determining the readiness of both parents and child to become involved in a successful toilet-training program, ask parents to keep detailed records for 7 days. They should discontinue record keeping if the child becomes ill or if fluid intake is changed. Record keeping includes documentation of:

• Behavioral indicators (e.g., the child was noticeably quieter or louder, started fussing or tugging at clothes, pointed toward the bathroom, cried, or squirmed)

• Positive parenteral feedback related to toileting behaviors only, in the form of praise, concrete rewards, affection, or approval

• Parental criticism in the form of scolding, threatening, or spanking if the child had wet or soiled the underclothes or did not tell them before eliminating

• Indication by the child of the need to go to the toilet by either gestures or words

If possible, a toilet-training program should begin after such records are completed because they show how parents are responding to the child’s behaviors and at what times the child is most likely to eliminate.

The objective of any toilet-training program is to help the child achieve small goals and experience comfort and success and to help the parents simultaneously experience feelings of adequacy, minimum tension, and success. Parents should understand that they will be capitalizing on the times the child is most likely to eliminate and that they should respond immediately to any cues indicating this need.

A task analysis for toileting includes the same type of discrete steps as outlined for feeding (see Box 24-4). A positive and relaxed attitude toward toilet training is important and differs little from the approach used with other children. (See Chapter 14.)

Dressing: Although dressing skills develop without special instruction in most children, special training is necessary to promote this skill in children with CI. Factors that interfere with spontaneous learning include immature motor skills, lack of motivation, physical impairments, and lack of opportunity.

The level of independence in dressing varies according to the degree of CI. Children with mild to moderate CI and no accompanying physical limitations can become independent in all dressing skills, except for more complex tasks such as color coordination. Those who have moderate CI can master most dressing skills, except fastening complicated closures such as buttons or ties. Those who have profound CI are usually able to assist in undressing and dressing but achieve no independent skills.

Children are considered developmentally ready for dressing training if they can sit quietly for 3 to 5 minutes while working on a task; can watch what they are doing while working on a task; can follow physical gestures or cues; can follow verbal commands; and can relate clothing to the appropriate body part, such as socks to feet. As with other self-help skills, the child may not be able to master every task but should be evaluated for evidence of willingness to participate at his or her level of readiness. The use of teaching devices, such as dolls with clothing with mock closures, and reinforcement for success in managing the fasteners can increase the child’s manipulative skills, which may be transferred to ready-to-wear clothing.

Grooming: The child usually learns self-grooming along with other independence-promoting skills, such as washing hands during toilet training. As with self-dressing, a major factor in learning independent grooming is the opportunity to practice the skills.

Dental hygiene is especially important. An odor-free mouth and clean teeth are essential in promoting a positive image. In addition, healthy teeth are necessary for proper chewing and speech. Missing teeth interfere with proper tongue positioning for clear speech. Most dental problems are preventable with the dental hygiene practices discussed in Chapter 14.

If the child has physical impairments that limit the ability to brush, special devices may be necessary, such as a larger-handled or curved toothbrush, to reach all surfaces of the teeth. Any strategies that help motivate the child to brush are used. For example, the parent can place a special calendar on the wall and mark each date with stars to represent the number of brushings per day. After earning a specified number of stars, the child can receive a special reward.

The child should routinely see a dentist. It is important to prepare the child for such visits, because it is much more difficult to change an unsatisfactory experience than to prevent one. The nurse can assist families by locating dentists who are familiar with treating children with CI and by discussing with parents procedures for preparing the child for the visit.

Help Families Adjust to Future Care

Not all families are able to cope with home care of children who are cognitively impaired, especially those who have severe or profound CI or multiple disabilities. Older parents may not be able to continue with care responsibilities once they reach retirement or old age. The decision regarding residential placement is difficult for families, and the availability of such facilities varies widely. The nurse’s role includes assisting parents in investigating and evaluating programs and helping parents adjust to the decision for placement. Guidelines for assessing out-of-home care facilities are given in the Nursing Care Guidelines box (also see Community Focus box).

Care for the Child During Hospitalization

Caring for the child during hospitalization can be a special challenge. Frequently nurses are unfamiliar with children who are cognitively impaired, and they may cope with their insecurity and fear by ignoring or isolating the child. Not only is this approach nonsupportive, it may also be destructive to the child’s sense of self-esteem and optimum development and may impair the parents’ ability to cope with the stress of the experience. To prevent engaging in this nontherapeutic approach, nurses can use the mutual participation model in planning the child’s care. Parents should stay with their child and assist with care, but they should not be made to feel as if the responsibility is totally theirs. Ideally the family should visit the hospital before admission. A visit minimizes the unfamiliarity of the hospital setting and is an opportunity for staff members to allay any fears the parents or child may have. When the child is admitted, a detailed history is taken, with special focus on all self-care abilities. (See Chapter 26.) During the interview the child’s developmental age is assessed.

Questions about the child’s abilities are approached positively. For example, rather than asking, “Is your child toilet trained yet?” the nurse may say, “Tell me about your child’s toileting habits.” The assessment should also focus on any special devices the child uses, effective measures of limit setting, unusual or favorite routines, and any behaviors that may require intervention. For example, if the parent states that the child engages in self-stimulatory or self-injurious activities, the nurse inquires about events that precipitate them and techniques the parents use to manage them. Once the child’s functional level is known, encourage him or her to be as independent as possible in the hospital setting.

The nurse can help the child feel less lonely during the hospital stay by making certain that the child has toys, is engaged in other activities, and has a roommate of approximately the same developmental age. The nurse should treat the child with dignity and respect in a manner that promotes acceptance and understanding of the child by children, parents, or others with whom the child comes into contact in the hospital.

Explain procedures to the child using methods of communication that are at the appropriate cognitive level. Generally explanations should be simple, short, and concrete, emphasizing what the child will physically experience. Demonstration either through actual practice or with visual aids is preferable to verbal explanation. Include parents in preprocedural teaching to aid in the child’s learning and to help the nurse learn effective methods of communicating with the child.

During hospitalization the nurse should also focus on growth-promoting experiences for the child. For example, hospitalization may be an excellent opportunity to emphasize to parents abilities the child does have but has not had the opportunity to practice, such as self-dressing. It may also be an opportunity for social experiences with peers, group play, or new educational or recreational activities. For example, one child who had the habit of screaming and kicking demonstrated a definite decrease in these behaviors after learning to pound pegs and use a punching bag. Through social services the parents may become aware of specialized programs for the child. Nutritional counseling is available if the child is overweight or has evidence of specific deficiencies, such as iron deficiency. Hospitalization may also offer parents a respite from everyday care responsibilities and an opportunity to discuss their feelings with a concerned professional.

Down Syndrome

![]() Down syndrome is the most common chromosomal abnormality of a generalized syndrome, occurring in 1 in 733 live births (Hall, 2007; Descartes and Carroll, 2007; National Down Syndrome Society, 2009d). It occurs slightly more often in Caucasians than in African-Americans, although the incidence does not vary with socioeconomic class.

Down syndrome is the most common chromosomal abnormality of a generalized syndrome, occurring in 1 in 733 live births (Hall, 2007; Descartes and Carroll, 2007; National Down Syndrome Society, 2009d). It occurs slightly more often in Caucasians than in African-Americans, although the incidence does not vary with socioeconomic class.

![]() Critical Thinking Exercise—Diagnosis of Down Syndrome in the Neonate

Critical Thinking Exercise—Diagnosis of Down Syndrome in the Neonate

Etiology

The cause of Down syndrome is not known. A number of theories have been proposed, including genetic predisposition to nondisjunction, exposure to radiation before conception, immunologic problems, and infection, but none of the hypotheses has been substantiated. Recent reports of cytogenetic and epidemiologic studies support the concept of multiple causality.

Although the etiology is unclear, the cytogenetics of the disorder is well established. Approximately 97% of all cases of Down syndrome are attributable to an extra chromosome 21 (group G), hence the name nonfamilial trisomy 21. Although children with trisomy 21 are born to parents of all ages, there is a statistically greater risk for older women, particularly those over 35 years of age (Table 24-2). For example, the incidence of Down syndrome is about 1 in 350 live births to women 35 years of age, but about 1 in 100 live births to women 40 years old. However, 80% of infants with Down syndrome are born to women under age 35 years because younger women have higher fertility rates (National Down Syndrome Society, 2009c). In less than 5% of cases, paternal age is a factor, especially if the father is 55 years of age or older (Grech, 2001; National Down Syndrome Society, 2009d).

TABLE 24-2

RELATION BETWEEN MATERNAL AGE AND ESTIMATED RISK OF DOWN SYNDROME

| AGE (yr) | RISK OF DOWN SYNDROME |

| 20 | 1 : 2000 |

| 25 | 1 : 1200 |

| 30 | 1 : 900 |

| 35 | 1 : 350 |

| 40 | 1 : 100 |

| 45 | 1 : 30 |

| 49 | 1 : 10 |

National Down Syndrome Society: About Down syndrome: incidences and maternal age, New York, 2009, The Society, available at www.ndss.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=61&Itemid=78 (accessed March 16, 2009).

Some 3% to 4% of cases may be caused by translocation of chromosome 21, which means chromosome 21 is attached to another chromosome. The majority of translocations in Down syndrome are fusions at the centromere between chromosomes 13, 14, 15, or 21; this is known as Robertsonian translocation (Descartes and Carroll, 2007; Hartway, 2009b; Ranweiler, 2009). About one-third of the translocation cases in Down syndrome are hereditary and are not associated with advanced parental age (Hartway, 2009b; National Down Syndrome Society, 2009c; Ranweiler, 2009). From 1% to 3% of affected persons demonstrate mosaicism, in which cell populations with both normal and abnormal chromosomes are present. The degree of physical and cognitive impairment is related to the percentage of cells with the abnormal chromosomal makeup. (For a discussion of the genetics involved in Down syndrome, see Chapter 5.)

Except for mosaicism, the mechanism by which the syndrome occurs has little effect on the characteristics displayed by the affected child and the management of the disorder. However, it is significant for purposes of genetic counseling. Whereas nondisjunction is usually a sporadic event associated with a low risk of recurrence (0.5% to 1%), a hereditary translocation is associated with a higher risk of recurrence (5% to 15%) (Hartway, 2009b; National Down Syndrome Society, 2009a). In Down syndrome caused by translocation, testing of the parents is necessary to identify the carrier and offer genetic counseling.

Clinical Manifestations

Down syndrome can usually be diagnosed by the clinical manifestations alone, although no one physical feature is diagnostic (Box 24-5 and Fig. 24-6), and there is considerable variation in phenotypic expression. In addition, some infants may have characteristics of Down syndrome, such as epicanthal folds, a narrow palate, short broad hands, and a transpalmar crease, but may be cytogenetically normal. A chromosomal analysis is therefore performed to confirm the genetic abnormality. The following are other outstanding features of the syndrome:

Intelligence—Mental capacity varies from severe CI to low-average intelligence but is generally within the mild to moderate range of CI and may be related to parental intelligence (National Down Syndrome Society, 2009a). Initial development may appear near normal. Although abilities can vary considerably, relative strengths often occur in visual over auditory processing, with relative weaknesses in grammar and expressive language and delays in motor development (National Down Syndrome Society, 2009a; Shapiro and Batshaw, 2007).

Social development—Development may be 2 to 3 years beyond the mental age, especially during early childhood. Temperamental characteristics show the same range as those found in unaffected peers. However, there is a relative strength in sociability (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2001a; Johnson and Walker, 2006) and a trend toward the easy-child pattern that may facilitate parent-child attachment and assist in integration with peers at school and in the community.

Congenital anomalies—About 40% to 45% have congenital heart disease (CHD), especially septal defects. Other structural defects include renal agenesis, duodenal atresia, Hirschsprung disease, and tracheoesophageal fistula. Skeletal defects include patella dislocation, hip subluxation, and atlantoaxial instability (instability of the first and second cervical vertebrae) in some children.

Sensory problems—Ocular problems include strabismus, nystagmus, astigmatism, myopia, hyperopia, head tilt, excessive tearing, and cataracts. Hearing loss occurs in a large percentage of children with Down syndrome. Conductive, sensorineural, and mixed losses each account for approximately one third of the diagnoses. Frequent otitis media, narrow canals, and impacted cerumen may contribute to the hearing problems.

Other physical disorders—These children have altered immune function, which contributes to numerous other conditions (Rittey, 2003). Respiratory tract infections are prevalent; when combined with cardiac anomalies, they are the chief cause of death, particularly during the first year. Because a high incidence of CHD is associated with trisomy 21, echocardiography is recommended at the time of initial diagnosis (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2001a; Bernstein, 2007). The incidence of leukemia is several times more frequent than expected in the general population, and in about half of the cases the type is acute megakaryoblastic leukemia. Thyroid dysfunction, including Graves disease, goiter, chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis, and hypothyroidism, is common. Acquired thyroid dysfunction also occurs frequently.

Growth—Growth in both height and weight is reduced, but weight gain is more rapid than growth in stature, which often results in overweight by 36 months of age. Deficient growth is most marked during infancy and adolescence. Growth of children with moderate or severe CHD is more affected than growth of those with mild or no CHD.

Sexual development—Development may be delayed, incomplete, or both. Male genitalia and secondary sexual characteristics such as facial hair may be underdeveloped. Breast development in females is mild to moderate. Menstruation usually occurs at the average age, and postpubertal women can be fertile; a small number have had offspring, the majority of whom were born with some type of abnormality. Men with Down syndrome have significantly lower overall fertility rate than other men of comparable ages (Descartes and Carroll, 2007; National Down Syndrome Society, 2009b).

Therapeutic Management

![]() Although Down syndrome has no cure, these children may require surgery to correct serious congenital anomalies, and they benefit from regular health care. Evaluation of sight and hearing is essential, and treatment of otitis media is required to prevent hearing problems, which can influence cognitive function. Neonatal and subsequent periodic testing of thyroid function is recommended, especially if growth is delayed. Special growth charts are available to monitor nutrition, height, weight, and general aspects of well-child care. Growth hormone therapy may be considered to increase height. Plastic surgery to alter phenotypic stigma is performed in some cases.

Although Down syndrome has no cure, these children may require surgery to correct serious congenital anomalies, and they benefit from regular health care. Evaluation of sight and hearing is essential, and treatment of otitis media is required to prevent hearing problems, which can influence cognitive function. Neonatal and subsequent periodic testing of thyroid function is recommended, especially if growth is delayed. Special growth charts are available to monitor nutrition, height, weight, and general aspects of well-child care. Growth hormone therapy may be considered to increase height. Plastic surgery to alter phenotypic stigma is performed in some cases.

Fifteen percent to twenty percent of children with Down syndrome have occipitoatlantal and atlantoaxial instability. Symptoms of the disorder include neck pain, weakness, and torticollis; however, most affected children are asymptomatic. The American Academy of Pediatrics (2004) recommends screening children with Down syndrome for atlantoaxial instability with a neurologic examination and radiography after their second birthday and before they engage in physically energetic exercise or sports or undergo surgery or rehabilitative procedures; however, this recommendation is controversial (Thompson, 2007). If children are diagnosed with atlantoaxial instability, surgery may be required, and they should refrain from participating in activities that may involve stress on the head and neck. If children become symptomatic, they should receive prompt attention because they are at risk for spinal cord compression.

Prognosis: Life expectancy for those with Down syndrome has significantly increased in recent years but remains lower than for the general population (Wiseman, Alford, Tybulewicz, et al, 2009). More than 80% of individuals with Down syndrome survive to age 55 years and beyond. As the prognosis continues to improve for these individuals, it will be important to provide for their long-term health care, social, and leisure needs.

Nursing Care Management

Support the Family at the Time of Diagnosis: Because of the distinctive physical characteristics, the infant with Down syndrome is usually diagnosed at birth. Generally parents wish to know the diagnosis as soon as possible. Most parents prefer that both of them be present during the informing interview so they can support each other emotionally.

Parental responses to the child may greatly influence decisions regarding future care (see Cultural Competence box). Whereas some families willingly plan to take the child home, others consider foster care or adoption. Institutionalization is no longer an option. The nurse must answer questions regarding developmental potential carefully, since the responses may influence the parents’ decision. It is obvious from ranges such as those given in Table 24-3 that the potential for developmental achievement varies greatly. Therefore it would be inaccurate and unfair to predict the child’s intellectual capacity at birth. It is important to stress that a decision regarding placement will affect all of the family members’ lives and need not be made at the time of diagnosis (see Critical Thinking Exercise). The nurse should emphasize every available source of assistance, such as parent groups, professional counseling, and literature, to help the family learn about Down syndrome and deal with childrearing problems.*

Assist the Family in Preventing Physical Problems: ![]() Many of the physical characteristics of Down syndrome present challenges. The hypotonicity of muscles and hyperextensibility of joints complicate positioning. The limp, flaccid extremities resemble the posture of a rag doll; as a result, holding the infant is difficult and cumbersome. Sometimes parents perceive this lack of molding to their bodies as evidence of inadequate parenting. The extended body position promotes heat loss because more surface area is exposed to the environment. Encourage parents to swaddle the infant (wrap him or her tightly in a blanket) before picking up the infant to provide security and warmth. The nurse also discusses with parents their feelings concerning attachment to the child, emphasizing that the child’s lack of clinging or molding is a physical characteristic, not a sign of detachment or rejection.

Many of the physical characteristics of Down syndrome present challenges. The hypotonicity of muscles and hyperextensibility of joints complicate positioning. The limp, flaccid extremities resemble the posture of a rag doll; as a result, holding the infant is difficult and cumbersome. Sometimes parents perceive this lack of molding to their bodies as evidence of inadequate parenting. The extended body position promotes heat loss because more surface area is exposed to the environment. Encourage parents to swaddle the infant (wrap him or her tightly in a blanket) before picking up the infant to provide security and warmth. The nurse also discusses with parents their feelings concerning attachment to the child, emphasizing that the child’s lack of clinging or molding is a physical characteristic, not a sign of detachment or rejection.

![]() Critical Thinking Exercise—Down Syndrome

Critical Thinking Exercise—Down Syndrome

Decreased muscle tone compromises respiratory expansion. In addition, the underdeveloped nasal bone causes a chronic problem of inadequate drainage of mucus. The constant stuffy nose forces the child to breathe by mouth, which dries the oropharyngeal membranes and thus increases the susceptibility to upper respiratory tract and ear infections. Measures to lessen infection include clearing the nose with a bulb-type syringe, rinsing the mouth with water after feedings, increasing fluid intake and using a cool-mist vaporizer to keep the mucous membranes moist and the nasal secretions liquefied, changing the child’s position frequently, and practicing good hand-washing technique. If antibiotics are ordered, the importance of completing the full course of therapy for successful eradication of the infection and prevention of growth of resistant organisms is stressed. Because hearing impairment is common and can interfere with development, the nurse should emphasize the importance of auditory testing.

Feeding difficulties may occur. The large, protruding tongue and hypotonia interfere with breast-feeding, bottle-feeding, and introduction of solid foods. Parents need to know that the tongue thrust does not indicate refusal to feed but is a physiologic response. Advise parents to use a small but long, straight-handled spoon to push the food toward the back and side of the mouth. If food is thrust out, it should be refed. At times the family may require the assistance of a specially trained individual, such as a lactation expert or occupational therapist, to guide them in dealing with feeding problems.

Dietary intake, especially of solid foods, needs supervision. Decreased muscle tone affects gastric motility, predisposing the child to constipation. Dietary measures such as increased fiber and fluid intake promote evacuation. The child’s eating habits need careful monitoring to prevent obesity. Obtain height and weight measurements on a serial basis and plot them on specialized growth charts, especially during infancy, because excessive weight gain can impede motor development. The child should receive calories in accordance with height and weight, not chronologic age.

During infancy the child’s skin is pliable and soft. However, it gradually becomes rough and dry and is prone to cracking and infection. Skin care involves minimum use of soap and application of lubricants. Apply lip balm to the lips, especially when the child is outdoors, to prevent excessive chapping.

Promote the Child’s Developmental Progress: Hypotonicity affects muscular development. Supporting skills, such as rolling over, sitting up, standing, or pulling oneself to a sitting or standing position, may be delayed. These children should be involved in an early stimulation program that provides physical therapy to help them learn motor skills.

Assess the child’s developmental progress at regular intervals, and encourage therapeutic adherence to a stimulation program. Developmental screening tests are inadequate to evaluate indications of progress such as increased strength, balance, coordination, or muscle tone. Therefore keep detailed written records of the child’s motor abilities to distinguish subtle changes in functioning. Periodic formal testing should also occur.

Parents can investigate appropriate daycare programs for the child as soon as possible. They should also investigate the public school system for special education classes, including early intervention programs and preschools. The nurse should give attention to preventing the problem of overprotection and including family members, especially the father and siblings, in the caring role.

Assist in Prenatal Diagnosis and Genetic Counseling: Prenatal diagnosis of Down syndrome is possible through chorionic villus sampling and amniocentesis, since chromosomal analysis of fetal cells can detect the presence of trisomy or translocation. Sporadic cases occur in young mothers that are not identified because there is no indication for prenatal testing. However, maternal testing for low serum α-fetoprotein levels, high chorionic gonadotropin levels, and low unconjugated estriol levels may identify potential cases, and these women can then undergo amniocentesis (Descartes and Carroll, 2007; Hall, 2007).

Offer prenatal testing and genetic counseling to women of advanced maternal age or those with a family history of Down syndrome. Although many women elect to have testing, some do not. If testing is conducted and the fetus is affected, the nurse must allow the parents to express their feelings concerning elective abortion and support their decision to terminate or proceed with the pregnancy. It is important for nurses to be aware of their own attitudes regarding testing and related decisions.

Fragile X Syndrome

![]() Fragile X syndrome is the most common inherited cause of CI and the second most common genetic cause of CI or intellectual disability after Down syndrome. It has been described in all ethnic groups and races. Fragile X syndrome occurs in 1 in 2000 to 5000 live births and affects males more severely than females (Menon, Leroux, White, et al, 2004; Rapaport, 2007). Fragile X syndrome occurs approximately 1 in 4000 males and 1 in 8000 females (National Fragile X Foundation, 2009). Because its identification as a disorder is relatively rare, many health care professionals and educators lack the necessary familiarity with the manifestations for appropriate referral and management once it is diagnosed.

Fragile X syndrome is the most common inherited cause of CI and the second most common genetic cause of CI or intellectual disability after Down syndrome. It has been described in all ethnic groups and races. Fragile X syndrome occurs in 1 in 2000 to 5000 live births and affects males more severely than females (Menon, Leroux, White, et al, 2004; Rapaport, 2007). Fragile X syndrome occurs approximately 1 in 4000 males and 1 in 8000 females (National Fragile X Foundation, 2009). Because its identification as a disorder is relatively rare, many health care professionals and educators lack the necessary familiarity with the manifestations for appropriate referral and management once it is diagnosed.

![]() Critical Thinking Exercise—Fragile X Syndrome

Critical Thinking Exercise—Fragile X Syndrome

The syndrome is caused by an abnormal mutation in the fragile X mental retardation 1 protein gene (FMR1) on the lower end of the long arm of the X chromosome (National Fragile X Foundation, 2009). Chromosomal analysis may demonstrate a fragile site (a region that fails to condense during mitosis and is characterized by a nonstaining gap or narrowing) in the cells of affected males and females and in carrier females. Since 1991, direct deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) analysis for the FMR1 gene mutation causing fragile X syndrome has greatly increased the accuracy of diagnostic testing of both affected and carrier individuals; this testing also permits prenatal diagnosis. However, when cognitively impaired individuals without an established family history of fragile X syndrome are being evaluated, cytogenetic and DNA studies should be performed to determine whether another chromosomal abnormality may be the cause of the CI.

This fragile site is caused by a gene mutation that results in excessive repeats of nucleotide base pairs in a specific DNA segment of the X chromosome. The number of repeats in a normal individual is between 5 and about 40 times. An individual with 55 to 200 base pair repeats is said to have an FMR1 premutation and is therefore a carrier. When passed from a parent to a child, these base pair repeats can expand from 200 to 2000 or more, which is termed a full mutation. This expansion occurs only when a carrier mother passes the mutation to her offspring; it does not occur when a carrier father passes the mutation to his daughters. Most males (80%) with a full mutation are affected (e.g., have the physical and behavioral features and intellectual disability); however, only 30% of females with a full mutation are affected. Interestingly, even females with a full mutation who do not appear to be affected, as well as carrier males and females with normal intelligence, may exhibit some learning disabilities and psychosocial disorders. This inheritance pattern has been termed X-linked dominant with reduced penetrance. It is in distinct contrast to the classic X-linked recessive pattern, in which all carrier females are normal, all affected males have symptoms of the disorder, and no males are carriers. Consequently, genetic counseling of affected families is more complex than that for families with a classic X-linked disorder such as hemophilia. Prenatal diagnosis of the fragile X gene mutation is possible through direct DNA testing in a family with an established history of the disorder, using amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling (Hall, 2007; National Fragile X Foundation, 2009). Affected members of both sexes are capable of transmitting the fragile X disorder.

Clinical Manifestations

The classic pattern of physical findings in adult males with fragile X syndrome consists of a long face with a prominent jaw (prognathism); large, protruding ears; and large testes (macroorchidism). However, these features may be less obvious in prepubertal children, and behavioral manifestations may initially suggest the diagnosis (Box 24-6). Developmental delay and language delay are common. Autism-like behavior (e.g., rocking, talking to self, spinning, hand flapping, hand biting, poor eye contact, echolalia) occurs in some individuals with fragile X syndrome (Chiu, Wegelin, Blank, et al, 2007; Hatton, Sideris, Skinner, et al, 2006; Wiesner, Cassidy, Grimes, et al, 2004). Some individuals also show social anxiety, whereas others have appropriate social skills and adaptive behavior, which means they may function or appear to function at a higher level than their IQ scores would predict.

In carrier females the clinical manifestations are extremely varied. Carrier and affected females may exhibit psychosocial deficits such as anxiety, withdrawal, and depression (Roberts, Mirrett, and Burchinal, 2001). In fact, some evidence suggests that low-expressing fragile X may be associated with personality changes in the absence of cognitive deficits (Goodlin-Jones, Tassone, Gane, et al, 2004).

Therapeutic Management

Fragile X syndrome has no cure. Medical treatment may include the use of serotonin agents such as carbamazepine (Tegretol) or fluoxetine (Prozac) to control violent temper outbursts, and central nervous system (CNS) stimulants to improve attention span and decrease hyperactivity. The use of folic acid, which affects the metabolism of CNS transmitters, is controversial. Medical treatment also addresses physical problems associated with the syndrome, which may include musculoskeletal concerns, mitral valve prolapse, recurrent otitis media, and seizures.

All affected children require early speech and language therapy, occupational therapy, and special educational assistance. Without appropriate intervention, a progressive decline in IQ can occur. Children with fragile X syndrome mimic the behavior of other children. Therefore mainstreaming them with children of similar age may improve their behavior.

Prognosis: Individuals with fragile X syndrome are expected to live a normal life span. Their CI may improve with behavioral and educational interventions, which should begin in preschool. Newborn inexpensive screening methods for fragile X syndrome is being researched in the United States, in line with the broadening of newborn screening criteria to include neurodevelopmental disorders that would benefit from early intervention (Bailey, Beskow, Davis, et al, 2006; Tassone, Pan, Amiri, et al, 2008). The availability of this test will likely facilitate expansion of the newborn screening in other high-risk populations (Hagerman, Berry-Kravis, Kaufmann, et al, 2009).

Nursing Care Management

Because CI is a fairly consistent finding in individuals with fragile X syndrome, the care for these families is the same as that for any child with intellectual disability. Because the disorder is hereditary, genetic counseling is important to inform parents and siblings of the risks of transmission. In addition, any male or female with unexplained or nonspecific mental impairment should be referred for chromosomal analysis and DNA testing, as well as appropriate genetic counseling. Families with a member affected by the disorder should be referred to the National Fragile X Foundation.*

Sensory Impairment

Hearing impairment is one of the most common disabilities in the United States. An estimated 3 in 1000 infants have hearing loss of varying degrees (Gregg, Wiorek, and Arvedson, 2004; Tierney and Brown, 2008). For those patients admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit, the incidence rises to approximately 2 to 4 per 100 neonates (Cunningham, Cox, Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine, et al, 2003). There are about 1 million children with hearing impairment ranging in age from birth to 21 years in the United States. Almost a third of these children have other disabilities, such as visual or cognitive impairments.

Definition and Classification

Hearing impaired is a general term indicating the presence of disability that may range in severity from slight to profound hearing loss. Severe to profound hearing loss describes a person whose hearing disability precludes successful processing of linguistic information through audition, with or without use of a hearing aid. Slight to moderately severe hearing loss describes a person who has residual hearing sufficient to enable successful processing of linguistic information through audition, generally with the use of a hearing aid. Hearing-impaired persons who are speech impaired tend not to have a physical speech defect other than that caused by the inability to hear.

Hearing defects may be classified according to etiology, pathology, or symptom severity. Each is important in terms of treatment, possible prevention, and rehabilitation.

Etiology: A number of prenatal and postnatal conditions can cause hearing loss. It is often associated with a family history of childhood hearing impairment, anatomic malformations of the head or neck, low birth weight, severe perinatal asphyxia, perinatal infection (cytomegalovirus, rubella, herpes, syphilis, toxoplasmosis, and bacterial meningitis), maternal prenatal substance abuse, chronic ear infection, cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, or administration of ototoxic drugs (Haddad, 2007; Smith, Bale, and White, 2005). In addition, high-risk neonates who survive once-fatal prenatal or perinatal conditions may be susceptible to hearing loss from the disorder or its treatment. For example, sensorineural hearing loss may result from exposure to the continuous humming noises or high noise levels associated with incubators, oxygen hoods, or intensive care units, especially when combined with the use of potentially ototoxic antibiotics.

Environmental noise is a special concern. Sounds loud enough to damage sensitive hair cells of the inner ear can produce irreversible hearing loss. Very loud, brief noise, such as gunfire, can cause immediate, severe, and permanent loss of hearing. Longer exposure to less intense but still hazardous sounds, such as loud persistent music via headphones, sound systems, concerts, or industrial noises, can also produce hearing loss (Daniel, 2007; Holte, 2003; Kenna, 2004). The exact sound level that produces hearing loss is unknown.

Pathology: Disorders of hearing are categorized according to the location of the defect. Conductive or middle ear hearing loss results from interference with transmission of sound to or by the middle ear. It is the most common of all types of hearing loss and most frequently is a result of recurrent serous otitis media. Conductive hearing impairment mainly involves interference with the loudness of sound.

Sensorineural hearing loss involves damage to the inner ear structures or the auditory nerve. The most common causes are congenital defects of inner ear structures and consequences of acquired conditions, such as kernicterus, infection, administration of ototoxic drugs, or exposure to excessive noise. Sensorineural hearing loss results in distortion of sound and problems in auditory discrimination. Although the child hears some of everything going on around him or her, the sounds are distorted, which severely affects discrimination and comprehension.

Mixed conductive-sensorineural hearing loss results from interference with transmission of sound in the middle ear and along neural pathways. It frequently results from recurrent otitis media and its complications.

Central auditory imperception includes all hearing losses for which defects in the conductive or sensorineural structures are not demonstrated. They are usually divided into organic and functional losses. In the organic type of central auditory imperception, the defect involves the reception of auditory stimuli along the central pathways and the processing of the message into meaningful communication. Examples are aphasia, the inability to express ideas in written or verbal form; agnosia, the inability to interpret sound correctly; and dysacusis, difficulty in processing details of sound or in discriminating among sounds. The functional type of hearing loss has no organic lesion to explain a central auditory loss. A functional hearing loss may occur in conversion disorder (an unconscious withdrawal from hearing to block remembrance of a traumatic event).

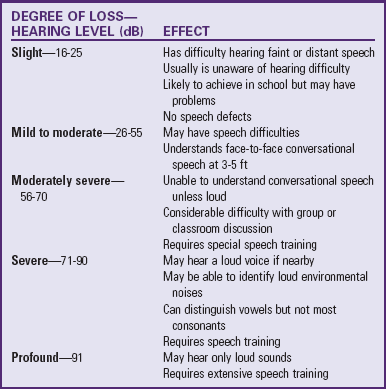

Symptom Severity: Hearing impairment is expressed in terms of the decibel (dB), a unit of loudness (Table 24-4). It is measured at various sound frequencies, such as 500, 1000, and 2000 cycles/sec, the critical listening range for speech. Hearing impairment can be classified according to hearing level (the individual’s hearing threshold as measured by an audiometer) and the degree of symptom severity as it affects speech (Table 24-5). These classifications offer only general guidelines regarding the effect of the impairment on any individual child, because children differ greatly in their ability to use residual hearing.

TABLE 24-4

INTENSITY OF SOUNDS EXPRESSED IN DECIBELS

| DECIBELS | REPRESENTATIVE SOUNDS |

| 0 | Softest sound normal ear can hear |

| 10 | Heartbeat, rustling of leaves |

| 20 | Whisper at 1.5 m (5 ft) |

| 30-45 | Normal conversation |

| 60 | Noise in average restaurant |

| 70-80 | Street noises |

| 80 | Loud radio in home |

| 90-100 | Train |

| 120 | Thunder, rock music |

| 140 | Jet plane during departure |

| >140 | Pain threshold |

Therapeutic Management

Treatment of hearing loss depends on the cause and type of hearing impairment. Many conductive hearing defects respond to medical or surgical treatment, such as antibiotic therapeutic management. When conductive loss is permanent, hearing can be improved with the use of a hearing aid to amplify sound.

Treatment for sensorineural hearing loss is much less satisfactory. Because the defect is not one of sound intensity, hearing aids are of less value in this type of defect. The use of cochlear implants (surgically implanted prosthetic devices) provides a sensation of hearing for children with severe to profound hearing loss (Hayes, Geers, Treiman, et al, 2009; Zeng and Liu, 2006). Children with sensorineural hearing loss have damage to the tiny hair cells lining the cochlea or to nerve cells that transmit auditory stimuli to the brain. Therefore hearing aids often provide little benefit, because even amplified sounds cannot be processed as a result of damage to the inner ear. A cochlear implant bypasses the damage and directly stimulates undamaged auditory nerve fibers that transmit signals to the brain, where they can be perceived as sound. Technologic refinements have produced multichannel cochlear implants that stimulate the auditory nerve at multiple locations. This produces improved processing of different frequencies represented in speech sounds so the individual can better understand and develop oral speech (Hayes, Geers, Treiman, et al, 2009; Winters, Collett, and Myers, 2005). Implantation of cochlear devices as early as possible in children with congenital or prelingual hearing impairment appears to facilitate development of speech (Haensel, Engelke, Ottenjann, et al, 2005; Hayes, Geers, Treiman, et al, 2009; Winters, Collett, and Myers, 2005).

Nursing Care Management