Nursing Care of the Family During Pregnancy

• Describe the process of confirming pregnancy and estimating the date of birth.

• Summarize the physical, psychosocial, and behavioral changes that usually occur as the mother and other family members adapt to pregnancy.

• Evaluate the benefits of prenatal care and problems of accessibility for some women.

• Outline the patterns of health care used to assess maternal and fetal health status at the initial and follow-up visits during pregnancy.

• Select the typical nursing assessments, diagnoses, interventions, and methods of evaluation in providing care for the pregnant woman.

• Plan education needed by pregnant women to understand physical discomforts related to pregnancy and to recognize signs and symptoms of potential complications.

• Examine the effect of culture, age, parity, and number of fetuses on the response of the family to the pregnancy and on the prenatal care provided.

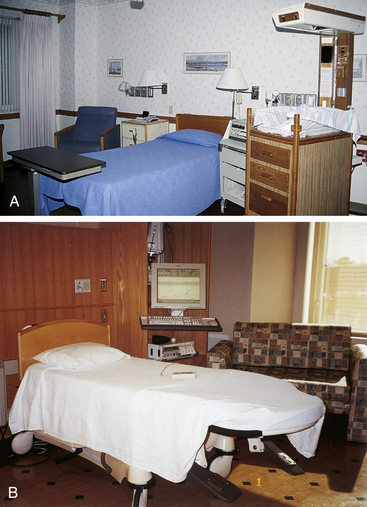

• Describe the options for health care providers and birth setting choices that are available.

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Lowdermilk/MWHC/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Lowdermilk/MWHC/

The prenatal period is a time of physical and psychologic preparation for birth and parenthood. Becoming a parent is considered one of the maturational milestones of adult life. It is a time of intense learning for parents and those close to them. The prenatal period provides a unique opportunity for nurses and other members of the health care team to influence family health. During this period essentially healthy women seek regular care and guidance. The nurse’s health promotion interventions can affect the well-being of the woman, her unborn child, and the rest of her family for many years.

Regular prenatal visits, ideally beginning soon after the first missed menstrual period, offer opportunities to ensure the health of the expectant mother and her infant. Prenatal health care enables discovery, diagnosis, and treatment of preexisting maternal disorders and any disorders that develop during the pregnancy. Prenatal care is designed to monitor the growth and development of the fetus and to identify abnormalities that will interfere with the course of normal labor. Prenatal care also provides education and support for self-management and parenting.

Pregnancy spans 9 months, but health care providers do not use the familiar monthly calendar to determine fetal age or to discuss the pregnancy. Instead, they use lunar months, which last 28 days, or 4 weeks. Normal pregnancy, then, lasts about 10 lunar months, which is the same as 40 weeks or 280 days. Health care providers also refer to early, middle, and late pregnancy as trimesters. The first trimester lasts from weeks 1 through 13; the second, from weeks 14 through 26; and the third, from weeks 27 through 40. A pregnancy is considered to be at term if it advances to the completion of 37 weeks. The focus of this chapter is on meeting the health needs of the expectant family over the course of pregnancy, which is known as the prenatal period.

Diagnosis of Pregnancy

Women suspect pregnancy when they miss a menstrual period. Many women come to the first prenatal visit after a positive home pregnancy test; however, the clinical diagnosis of pregnancy before the second missed period is difficult in some women. Physical variations, obesity, or tumors, for example, confound even the experienced examiner. Accuracy is important, however, because emotional, social, health, or legal consequences of an inaccurate diagnosis, either positive or negative, can be extremely serious.

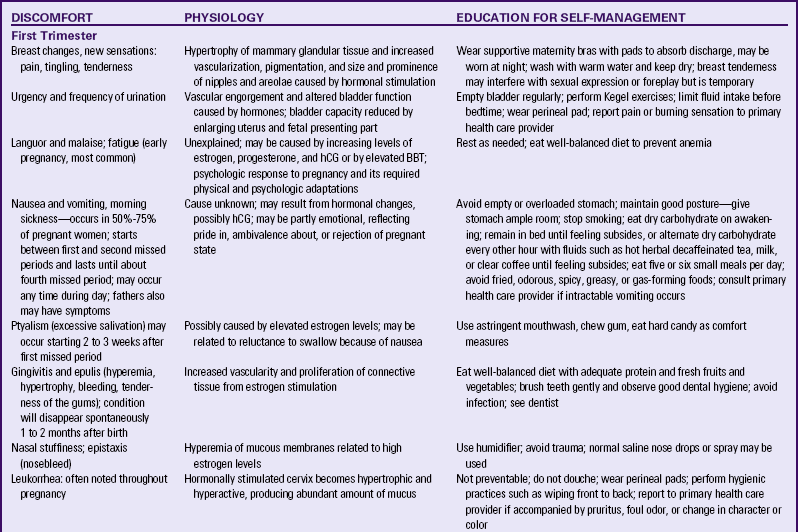

Signs and Symptoms

The physical cues of pregnancy vary greatly; therefore, the diagnosis of pregnancy is uncertain for a time. Many of the indicators of pregnancy are clinically useful in the diagnosis of pregnancy, and they are classified as presumptive, probable, or positive (see Table 13-2).

Presumptive indicators of pregnancy include subjective symptoms and objective signs. Subjective symptoms are reported by the woman and include amenorrhea, nausea and vomiting (morning sickness), breast tenderness, urinary frequency, and fatigue. Quickening, the mother’s first perception of fetal movement, is noted between weeks 16 and 20. Objective signs that are validated by the examiner include elevation of basal body temperature (BBT), breast and abdominal enlargement, and changes in the uterus and vagina. Other visible changes occur in the skin, such as striae gravidarum, deeper pigmentation of the areolae, chloasma (mask of pregnancy), and linea nigra (pigmented line on the abdomen).

The presumptive indicators of pregnancy can be caused by conditions other than gestation; therefore, these signs alone are not reliable for diagnosis of pregnancy.

Probable indicators of pregnancy are detected by an examiner and are related mainly to physical changes in the uterus. Objective signs include uterine enlargement, Braxton Hicks contractions, placental souffle (sound of blood passing through the placenta), ballottement (examiner is able to feel the fetus float during a vaginal examination), and a positive pregnancy test. When combined with presumptive signs and symptoms, they strongly suggest pregnancy, but they are not conclusive.

The positive indicators of pregnancy are directly attributed to the fetus and include the presence of a fetal heartbeat distinct from that of the mother, fetal movement felt by someone other than the mother, and visualization of the fetus with a technique such as ultrasound examination.

Estimating Date of Birth

After the diagnosis of pregnancy the woman’s first question usually concerns when she will give birth. This date has traditionally been termed the estimated date of confinement (EDC), although estimated date of delivery (EDD) also has been used. To promote a more positive perception of both pregnancy and birth, however, the term estimated date of birth (EDB) is suggested. Accurate dating of pregnancy and calculation of the EDB have implications for timing of specific prenatal screening tests, assessing fetal growth and critical decisions for managing pregnancy complications. Ultrasound dating of gestational age is accurate; however, researchers in the Routine Antenatal Diagnostic Imaging with Ultrasound Study (RADIUS) concluded that the cost associated with the routine use of ultrasound screening in the absence of clear clinical indications is prohibitive (Hunter, 2009).

Several formulas have been suggested for calculating the EDB based on the LMP. These rules assume regular 28-day ovulatory cycles and rely on a woman’s accurate recall of her LMP. The most common of these methods is Nägele’s rule, which is as follows: after determining the first day of the LMP, subtract 3 calendar months and add 7 days; or alternatively, add 7 days to the LMP and count forward 9 calendar months (Box 15-1). Only about 5% of women give birth spontaneously on the EDB as determined by Nägele’s rule. Most women give birth during the period extending from 7 days before to 7 days after the EDB.

Adaptation to Pregnancy

Pregnancy affects all family members, and each family member must adapt to the pregnancy and interpret its meaning in light of his or her own needs. This process of family adaptation to pregnancy takes place within a cultural environment influenced by societal trends. Dramatic changes have occurred in Western society in recent years, and the nurse must be prepared to support not only traditional families in the childbirth experience but also single-parent families, reconstituted families, dual-career families, and alternative families.

Much of the research on family dynamics in pregnancy in the United States and Canada has been done with Caucasian, middle-class nuclear families. Therefore, the findings may not apply to families who do not fit the traditional North American model. Adaptation of terms is appropriate to avoid embarrassment to the nurse and offense to the family. Additional research is needed on a variety of families to determine if study findings generated in traditional families are applicable to others.

Maternal Adaptation

Women of all ages use the months of pregnancy to adapt to the maternal role, a complex process of social and cognitive learning. Early in pregnancy nothing seems to be happening, and a woman may spend much time sleeping secondary to the increased fatigue of this stage. With the perception of fetal movement in the second trimester, the woman turns her attention inward to her pregnancy and to relationships with her mother and other women who have been or who are pregnant.

Pregnancy is a maturational milestone that can be stressful but also rewarding as the woman prepares for a new level of caring and responsibility. Her self-concept changes in readiness for parenthood as she prepares for her new role. She moves gradually from being self-contained and independent to being committed to a lifelong concern for another human being. This growth requires mastery of certain developmental tasks: accepting the pregnancy, identifying with the role of mother, reordering the relationships between herself and her mother and between herself and her partner, establishing a relationship with the unborn child, and preparing for the birth experience. The partner’s emotional support is an important factor in the successful accomplishment of these developmental tasks. Single women with limited support may have difficulty making this adaptation.

Accepting the Pregnancy

The first step in adapting to the maternal role is accepting the idea of pregnancy and assimilating the pregnant state into the woman’s way of life. Mercer (1995) described this process as cognitive restructuring and credited Reva Rubin (1984) as the nurse theorist who pioneered our understanding of maternal role attainment. The degree of acceptance is reflected in the woman’s emotional responses. Many women are upset initially at finding themselves pregnant, especially if the pregnancy is unintended. Eventual acceptance of pregnancy parallels the growing acceptance of the reality of a child. However, do not equate nonacceptance of the pregnancy with rejection of the child, for a woman may dislike being pregnant but feel love for the child to be born.

Women who are happy and pleased about their pregnancy often view it as biologic fulfillment and part of their life plan. They have high self-esteem and tend to be confident about outcomes for themselves, their babies, and other family members. Despite a general feeling of well-being, many women are surprised to experience emotional lability, that is, rapid and unpredictable changes in mood. These swings in emotions and increased sensitivity to others are disconcerting to the expectant mother and those around her. Increased irritability, explosions of tears, and anger can alternate with feelings of great joy and cheerfulness apparently with little or no provocation.

Profound hormonal changes that are part of the maternal response to pregnancy may be responsible for mood changes. Other reasons such as concerns about finances and changed lifestyle contribute to this seemingly erratic behavior.

Most women have ambivalent feelings during pregnancy whether the pregnancy was intended or not. Ambivalence—having conflicting feelings simultaneously—is considered a normal response for people preparing for a new role. During pregnancy women may, for example, feel great pleasure that they are fulfilling a lifelong dream, but they also may feel great regret that life as they now know it is ending.

Even women who are pleased to be pregnant may experience feelings of hostility toward the pregnancy or unborn child from time to time. Such incidents as a partner’s chance remark about the attractiveness of a slim, nonpregnant woman or news of a colleague’s promotion can give rise to ambivalent feelings. Body sensations, feelings of dependence, or the realization of the responsibilities of child care also can generate such feelings.

Intense feelings of ambivalence that persist through the third trimester may indicate an unresolved conflict with the motherhood role (Mercer, 1995). After the birth of a healthy child, memories of these ambivalent feelings usually are dismissed. If the child is born with a defect, however, a woman may look back at the times when she did not want the pregnancy and feel intensely guilty. She may believe that her ambivalence caused the birth defect. She then will need assurance that her feelings were not responsible for the problem.

Identifying with the Mother Role

The process of identifying with the mother role begins early in each woman’s life when she is being mothered as a child. Her social group’s perception of what constitutes the feminine role can subsequently influence her toward choosing between motherhood or a career, being married or single, being independent rather than interdependent, or being able to manage multiple roles. Practice roles, such as playing with dolls, babysitting, and taking care of siblings may increase her understanding of what being a mother involves.

Many women have always wanted a baby, liked children, and looked forward to motherhood. Their high motivation to become a parent promotes acceptance of pregnancy and eventual prenatal and parental adaptation. Other women apparently have not considered in any detail what motherhood means to them. During pregnancy these women must resolve conflicts such as not wanting the pregnancy and child-related or career-related decisions.

Reordering Personal Relationships

Close relationships of the pregnant woman undergo change during pregnancy as she prepares emotionally for the new role of mother. As family members learn their new roles, periods of tension and conflict may occur. An understanding of the typical patterns of adjustment can help the nurse reassure the pregnant woman and explore issues related to social support. Promoting effective communication patterns between the expectant mother and her own mother and between the expectant mother and her partner are common nursing interventions provided during the prenatal visits.

The woman’s own relationship with her mother is significant in adaptation to pregnancy and motherhood. Important components in the pregnant woman’s relationship with her mother are the mother’s availability (past and present), her reactions to the daughter’s pregnancy, respect for her daughter’s autonomy, and the willingness to reminisce (Mercer, 1995).

The mother’s reaction to the daughter’s pregnancy signifies her acceptance of the grandchild and of her daughter. If the mother is supportive, the daughter has an opportunity to discuss pregnancy and labor with a knowledgeable and accepting woman (Fig. 15-1). Reminiscing about the pregnant woman’s early childhood and sharing the prospective grandmother’s account of her childbirth experience help the daughter anticipate and prepare for labor and birth.

FIG. 15-1 A pregnant woman and her mother enjoying their walk together. (Courtesy Michael S. Clement, MD, Mesa, AZ.)

Although the woman’s relationship with her mother is significant in considering her adaptation to pregnancy, the most important person to the pregnant woman is usually the father of her child. Women express two major needs within this relationship during pregnancy: feeling loved and valued and having the child accepted by the partner.

The marital or committed relationship is not static but evolves over time. The addition of a child changes forever the nature of the bond between partners. This may be a time when couples grow closer, and the pregnancy has a maturing effect on the partners’ relationship as they assume new roles and discover new aspects of one another. Partners who trust and support each other are able to share mutual-dependency needs (Mercer, 1995).

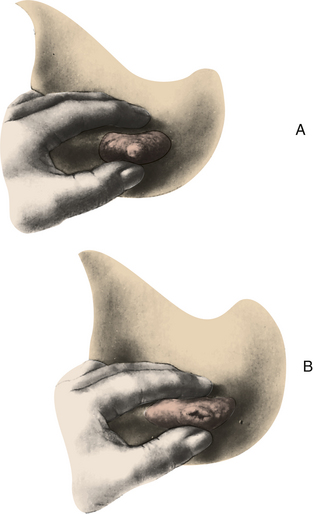

Sexual expression during pregnancy is highly individual. The sexual relationship is affected by physical, emotional, and interactional factors, including misinformation about sex during pregnancy, sexual dysfunction, and physical changes in the woman. An individual may also inaccurately attribute anomalies, mental retardation, and other injuries to the fetus and mother to sexual relations during pregnancy. Some couples fear that the birth process will drastically change the woman’s genitals. Some couples do not express their concerns to the health care provider because of embarrassment or because they do not want to appear foolish.

As pregnancy progresses, changes in body shape, body image, and levels of discomfort influence both partners’ desire for sexual expression. During the first trimester the woman’s sexual desire may decrease, especially if she has breast tenderness, nausea, fatigue, or sleepiness. As she progresses into the second trimester, however, her sense of well-being combined with the increased pelvic congestion that occurs at this time may increase her desire for sexual release. In the third trimester, somatic complaints and physical bulkiness may increase her physical discomfort and again diminish her interest in sex.

Partners need to feel free to discuss their sexual responses during pregnancy with each other and with their health care provider (see later discussion).

Establishing a Relationship with the Fetus

Emotional attachment—feelings of being tied by affection or love—begins during the prenatal period as women use fantasizing and daydreaming to prepare themselves for motherhood (Rubin, 1975). They think of themselves as mothers and imagine maternal qualities they would like to possess. Expectant parents desire to be warm, loving, and close to their child. They try to anticipate changes that the child will bring into their lives and wonder how they will react to noise, disorder, reduced freedom, and caregiving activities. The mother-child relationship progresses through pregnancy as a developmental process that unfolds in three phases.

In phase 1 the woman accepts the biologic fact of pregnancy. She needs to be able to state, “I am pregnant” and incorporate the idea of a child into her body and self-image. The woman’s thoughts center around herself and the reality of her pregnancy. The child is viewed as part of herself, not a separate and unique person.

In phase 2 the woman accepts the growing fetus as distinct from herself, usually accomplished by the fifth month. She can now say, “I am going to have a baby.” This differentiation of the child from the woman’s self permits the beginning of the mother-child relationship that involves not only caring but also responsibility. Attachment of a mother to her child is enhanced by experiencing a planned pregnancy and it increases when ultrasound examination and quickening confirm the reality of the fetus.

With acceptance of the reality of the child (hearing the heartbeat and feeling the child move) and an overall feeling of well-being, the woman enters a quiet period and becomes more introspective. A fantasy child becomes precious to the woman. As the woman seems to withdraw and to concentrate her interest on the unborn child, her partner sometimes feels left out. If there are children in the family, they may become more demanding in their efforts to redirect the mother’s attention to themselves.

During phase 3 of the attachment process, the woman prepares realistically for the birth and parenting of the child. She expresses the thought, “I am going to be a mother” and defines the nature and characteristics of the child. She may, for example, speculate about the child’s sex (if unknown) and personality traits based on patterns of fetal activity.

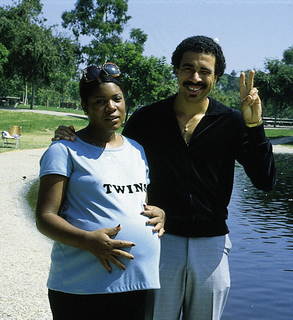

Although the mother alone experiences the child within, both parents and siblings believe the unborn child responds in a very individualized, personal manner. Family members may interact a great deal with the unborn child by talking to the fetus and stroking the mother’s abdomen, especially when the fetus shifts position (Fig. 15-2). The fetus may have a nickname used by family members.

Preparing for Childbirth

Many women actively prepare for birth by reading books, viewing films, attending parenting classes, and talking to other women. They seek the best caregiver possible for advice, monitoring, and caring. The multiparous woman has her own history of labor and birth that influences her approach to preparation for this childbirth experience.

Anxiety can arise from concern about a safe passage for herself and her child during the birth process (Mercer, 1995; Rubin, 1975). Some women do not express this concern overtly, but they give cues to the nurse by making plans for care of the new baby and other children in case “anything should happen.” These feelings persist despite statistical evidence about the safe outcome of pregnancy for mothers and their infants. Many women fear the pain of childbirth or mutilation because they do not understand anatomy and the birth process. Education can alleviate many of these fears. Women also express concern over what behaviors are appropriate during the birth process and whether caregivers will accept them and their actions.

Toward the end of the third trimester, breathing is difficult, and fetal movements become vigorous enough to disturb the woman’s sleep. Backaches, frequency and urgency of urination, constipation, and varicose veins can become troublesome. The bulkiness and awkwardness of her body interfere with the woman’s ability to care for other children, perform routine work-related duties, and assume a comfortable position for sleep and rest. By this time, most women become impatient for labor to begin, whether the birth is anticipated with joy, dread, or a mixture of both. A strong desire to see the end of pregnancy, to be over and done with it, makes women at this stage ready to move on to childbirth.

Paternal Adaptation

The father’s beliefs and feelings about the ideal mother and father and his cultural expectation of appropriate behavior during pregnancy affect his response to his partner’s need for him. One man may engage in nurturing behavior. Another may feel lonely and alienated as the woman becomes physically and emotionally engrossed in the unborn child. He may seek friends and relationships outside the home or become interested in a new hobby or involved with his work. Some men view pregnancy as proof of their masculinity and their dominant role. To others, pregnancy has no meaning in terms of responsibility to either mother or child. However, for most men, pregnancy can be a time of preparation for the parental role with intense learning.

Accepting the Pregnancy

The ways fathers adjust to the parental role has been the subject of considerable research. In older societies the man enacted the ritual couvade; that is, he behaved in specific ways and respected taboos associated with pregnancy and giving birth so his new status was recognized and endorsed. Now some men experience pregnancy-like symptoms, such as nausea, weight gain, and other physical symptoms. This phenomenon is known as the couvade syndrome. Changing cultural and professional attitudes have encouraged fathers’ participation in the birth experience.

The man’s emotional response to becoming a father, his concerns, and his informational needs change during the course of pregnancy. Phases of the developmental pattern become apparent. May (1982) described three phases characterizing the developmental tasks experienced by the expectant father:

• The announcement phase may last from a few hours to a few weeks. The developmental task is to accept the biologic fact of pregnancy. Men react to the confirmation of pregnancy with joy or dismay, depending on whether the pregnancy is desired, unplanned, or unwanted. Ambivalence in the early stages of pregnancy is common. If pregnancy is unplanned or unwanted, some men find the alterations in life plans and lifestyles difficult to accept. Some men engage in extramarital affairs for the first time during their partner’s pregnancy. Others batter their wives for the first time or escalate the frequency of battering episodes (Krieger, 2008). Chapter 5 provides information about violence against women and offers guidance on assessment and intervention.

• The second phase, the moratorium phase, is the period when he adjusts to the reality of pregnancy. The developmental task is to accept the pregnancy. Men appear to put conscious thought of the pregnancy aside for a time. They become more introspective and engage in many discussions about their philosophy of life, religion, childbearing, and childrearing practices and their relationships with family members, particularly with their father. Depending on the man’s readiness for the pregnancy, this phase may be relatively short or persist until the last trimester.

• The third phase, the focusing phase, begins in the last trimester and is characterized by the father’s active involvement in both the pregnancy and his relationship with his child. The developmental task is to negotiate with his partner the role he is to play in labor and to prepare for parenthood. In this phase the man concentrates on his experience of the pregnancy and begins to think of himself as a father.

Identifying with the Father Role

Each man brings to pregnancy attitudes that affect the way in which he adjusts to the pregnancy and parental role. His memories of the fathering he received from his own father, the experiences he has had with child care, and the perceptions of the male and father roles within his social group will guide his selection of the tasks and responsibilities he will assume. Some men are highly motivated to nurture and love a child. They are excited and pleased about the anticipated role of father (Fig. 15-3). Others are more detached or even hostile to the idea of fatherhood.

Reordering Personal Relationships

The partner’s main role in pregnancy is to nurture and respond to the pregnant woman’s feelings of vulnerability. The partner also must deal with the reality of the pregnancy. The partner’s support indicates involvement in the pregnancy and preparation for attachment to the child.

Some aspects of a partner’s behavior may indicate rivalry, and it may be especially evident during sexual activity. For example, some men protest that fetal movements prevent sexual gratification or feel that they are being watched by the fetus during sexual activity. However, feelings of rivalry are often unconscious and not verbalized, but expressed in subtle behaviors.

The woman’s increased introspection may cause her partner to feel uneasy as she becomes preoccupied with thoughts of the child and of her motherhood, with her growing dependence on her health care provider, and with her reevaluation of the couple’s relationship.

Establishing a Relationship with the Fetus

The father-child attachment can be as strong as the mother-child relationship, and fathers can be as competent as mothers in nurturing their infants. The father-child attachment also begins during pregnancy. A father may rub or kiss the maternal abdomen; try to listen, talk, or sing to the fetus; or play with the fetus as he notes movement. Calling the unborn child by name or nickname helps to confirm the reality of pregnancy and promote attachment.

Men prepare for fatherhood in many of the same ways as women do for motherhood—by reading and by fantasizing about the baby. Daydreaming about their role as father is common in the last weeks before the birth; however, men rarely describe their thoughts unless they are reassured that such daydreams are normal.

Nurses can help fathers identify concerns and prepare for the reality of a baby by asking questions such as the following:

• What do you expect the baby to look and act like?

• What do you think being a father will be like?

• Have you thought about the baby’s crying? Changing diapers? Burping the baby? Being awakened at night? Sharing your partner with the baby?

Some fathers will not wish to answer such questions when they are asked but may need time to think them through or discuss them with their partners.

As the birth date approaches, men have more questions about fetal and newborn behaviors. Some men are shocked or amazed at the smallness of clothes and furniture for the baby. If an expectant father can imagine only an older child and has difficulty visualizing or talking about an infant, this situation must be explored. The nurse can tell the father about the unborn child’s ability to respond to light, sound, and touch and encourage him to feel and talk to the fetus. A tour of a newborn nursery or discussions with new fathers, as in childbirth classes, may be welcomed.

Some men become involved by choosing the child’s name and anticipating the child’s sex, if it is not already known. Some couples select the name of the child as early as the first month of pregnancy. Family tradition, religious customs, and the continuation of the parent’s name or names of relatives or friends are important in the selection process.

Preparing for Childbirth

The days and weeks immediately before the expected day of birth are characterized by anticipation and anxiety. Boredom and restlessness are common as the couple focuses on the birth process; however, during the last 2 months of pregnancy, many expectant fathers experience a surge of creative energy at home and on the job. They become dissatisfied with their present living space. If possible, they tend to act on the need to alter the environment (remodeling, painting, etc.). This activity is their way of sharing in the childbearing experience. They are able to channel the anxiety and other feelings experienced during the final weeks before birth into productive activities. This behavior earns recognition and compliments from friends, relatives, and their partners.

Major concerns for the man are getting the woman to a health care facility in time for the birth and not appearing ignorant. Many men want to be able to recognize labor and determine when it is appropriate to leave for the hospital or call the birth attendant. They fantasize different situations and plan what they will do in response to them, or rehearse taking various routes to the hospital, timing each route at different times of the day.

Some prospective fathers have questions about the labor suite’s furniture and equipment, nursing staff, and location, as well as the availability of the birth attendant and anesthesia provider. Others want to know what is expected of them when their partners are in labor. The man also may have fears concerning safe passage of his child and partner and the possible death or complications of his partner and child. It is important he verbalize these fears, otherwise he cannot help his mate deal with her own spoken or unspoken apprehension.

With the exception of childbirth preparation classes, a man has few opportunities to learn ways to be an involved and active partner in this rite of passage into parenthood. Mothers often sense the tensions and apprehensions of the unprepared, unsupportive father and it often increases their fears.

The same fears, questions, and concerns may affect birth partners who are not the biologic fathers. Birth partners need to be kept informed, supported, and included in all activities in which the mother desires their participation. Nurses can do much to promote pregnancy and birth as a family experience.

Sibling Adaptation

Sharing the spotlight with a new brother or sister may be the first major crisis for a child. The older child often experiences a sense of loss or feels jealous at being “replaced” by the new sibling. Some of the factors that influence the child’s response are age, the parents’ attitudes, the role of the father, the length of separation from the mother, the facility visitation policy, and the way the child has been prepared for the change.

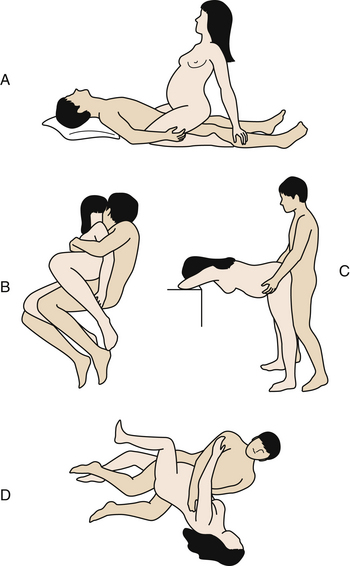

A mother with other children must devote time and effort to reorganizing her relationships with them. She needs to prepare siblings for the birth of the baby (Fig. 15-4 and Box 15-2) and begin the process of role transition in the family by including the children in the pregnancy and being sympathetic to older children’s concerns about losing their places in the family hierarchy. No child willingly gives up a familiar position.

FIG. 15-4 A sibling class of preschoolers learns infant care using dolls. (Courtesy Marjorie Pyle, RNC, Lifecircle, Costa Mesa, CA.)

Siblings’ responses to pregnancy vary with their age and dependency needs. The 1-year-old infant seems largely unaware of the process, but the 2-year-old child notices the change in his or her mother’s appearance and may comment that “Mommy’s fat.” Toddlers’ need for sameness in the environment makes children aware of any change. They may exhibit more clinging behavior and sometimes regress in toilet training or eating.

By age 3 or 4 years, children like to be told the story of their own beginning and accept a comparison of their own development with that of the present pregnancy. They like to listen to the fetal heartbeat and feel the baby moving in utero (see Fig. 15-2). Sometimes they worry about how the baby is being fed and what it wears.

School-age children take a more clinical interest in their mother’s pregnancy. They may want to know in more detail, “How did the baby get in there?” and “How will it get out?” Children in this age-group notice pregnant women in stores, churches, and schools and sometimes seem shy if they need to approach a pregnant woman directly. On the whole, they look forward to the new baby, see themselves as “mothers” or “fathers,” and enjoy buying baby supplies and readying a place for the baby. Because they still think in concrete terms and base judgments on the here and now, they respond positively to their mother’s current good health.

Early and middle adolescents preoccupied with the establishment of their own sexual identity may have difficulty accepting the overwhelming evidence of the sexual activity of their parents. They reason that if they are too young for such activity, certainly their parents are too old. They seem to take on a critical parental role and may ask, “What will people think?” or “How can you let yourself get so fat?” or “How can you let yourself get pregnant?” Many pregnant women with teenage children will confess that the attitudes of their teenagers are the most difficult aspect of their current pregnancy.

Late adolescents do not appear to be unduly disturbed. They are busy making plans for their own lives and realize that they soon will be gone from home. Parents usually report they are comforting and act more as other adults than as children.

Grandparent Adaptation

Every pregnancy affects all family relationships. For expectant grandparents a first pregnancy in a child is undeniable evidence that they are growing older. Many think of a grandparent as old, white-haired, and becoming feeble of mind and body; however, some people face grandparenthood while still in their 30s or 40s. Some individuals react negatively to the news that they will be grandparents, indicating that they are not ready for the new role.

In some family units, expectant grandparents are nonsupportive and may inadvertently decrease the self-esteem of the parents-to-be. Mothers may talk about their terrible pregnancies; fathers may discuss the endless cost of rearing children; and mothers-in-law may complain that their sons are neglecting them because their concern is now directed toward the pregnant daughters-in-law.

However, most grandparents are delighted at the prospect of a new baby in the family. It reawakens the feelings of their own youth, the excitement of giving birth, and their delight in the behavior of the parents-to-be when they were infants. They set up a memory store of the child’s first smiles, first words, and first steps that they can use later for “claiming” the newborn as a member of the family. These behaviors provide a link between the past and present for the parents and grandparents-to-be.

In addition, the grandparent is the historian who transmits the family history, a resource person who shares knowledge based on experience; a role model; and a support person. The grandparent’s presence and support can strengthen family systems by widening the circle of support and nurturance (Fig. 15-5).

Care Management

The purpose of prenatal care is to identify existing risk factors and other deviations from normal so that pregnancy outcomes may be enhanced (Johnson, Gregory, & Niebyl, 2007). Major emphasis is placed on preventive aspects of care, primarily to motivate the pregnant woman to practice optimal self-management and to report unusual changes early so that problems can be prevented or minimized. If health behaviors must be modified in early pregnancy, nurses need to understand psychosocial factors that may influence the woman. In holistic care, nurses provide information and guidance about not only the physical changes but also the psychosocial impact of pregnancy on the woman and members of her family. The goals of prenatal nursing care, therefore, are to foster a safe birth for the infant and to promote satisfaction of the mother and family with the pregnancy and birth experience.

More than two thirds of women in the United States received care in the first trimester. African- American, Hispanic, and Native-American women were twice as likely to get late prenatal care or no care at all than were Caucasian women (Heron, Sutton, Xu, Ventura, Strobino, & Guyer, 2010). Although women of middle or high socioeconomic status routinely seek prenatal care, women living in poverty or who lack health insurance are not always able to use public health care services or gain access to private care. Lack of culturally sensitive care providers and barriers in communication resulting from differences in language also interfere with access to care (Darby, 2007). Likewise, immigrant women who come from cultures in which prenatal care is not emphasized may not know to seek routine prenatal care. Birth outcomes in these populations are less positive, with higher rates of maternal and fetal or newborn complications. Problems with low birth weight (LBW; less than 2500 g) and infant mortality have in particular been associated with lack of adequate prenatal care.

Barriers to obtaining health care during pregnancy include lack of transportation, unpleasant clinic facilities or procedures, inconvenient clinic hours, childcare problems, and personal attitudes (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG] Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women, 2006; Daniels, Noe, & Mayberry, 2006; Johnson, Gregory, & Niebyl, 2007). The availability of advanced practice nurses (nurse practitioners and certified nurse-midwives) as independent providers of care or in collaborative practice with physicians improves the availability and accessibility of prenatal care. A regular schedule of home visiting by trained unlicensed health workers during pregnancy is effective in reducing barriers to prenatal care (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ] Healthcare Innovations Exchange, 2009).

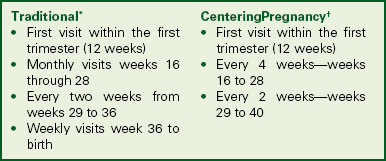

The current model for provision of prenatal care has been used for more than a century. The initial visit usually occurs in the first trimester, with monthly visits through week 28 of pregnancy. Thereafter, visits are scheduled every 2 weeks until week 36, and then every week until birth (American Academy of Pediatrics and ACOG, 2007) (Box 15-3). Research supports a model of fewer prenatal visits, and in some practices there is a growing tendency to have fewer visits with women who are at low risk for complications.

CenteringPregnancy is a care model that is gaining in popularity. This model is one of group prenatal care in which authority is shifted from the provider to the woman and other women who have similar due dates. The model creates an atmosphere that facilitates learning, encourages discussion, and develops mutual support. Most care takes place in the group setting after the first visit and continues for ten 2-hour sessions (Moos, 2006). At each meeting, the first 30 minutes is spent in completing assessments (by the woman herself and by the healthcare provider), and the rest of the time is spent in group discussion of specific issues such as discomforts of pregnancy and preparation for labor and birth. Families and partners are encouraged to participate (Massey, Rising, & Ickovics, 2006; Reid, 2007) (see Box 15-3).

Prenatal care is ideally a multidisciplinary activity in which nurses work with nurse-midwives, nutritionists, physicians, social workers, and others. Collaboration among these individuals is necessary to provide holistic care. The case management model, which makes use of care maps and critical pathways, is one system that promotes comprehensive care with limited overlap in services. To emphasize the nursing role, care management for the initial visit and follow-up visits is organized around the central elements of the nursing process: assessment, nursing diagnoses, expected outcomes, plan of care and interventions, and evaluation (see the Nursing Process box).

In recent years the concept of preconception care has been recognized as an important contributor to good pregnancy outcomes (see Chapter 4). If women can be taught healthy lifestyle behaviors and then practice them before conception—specifically good nutrition, entering pregnancy with as healthy a weight as possible, adequate intake of folic acid, avoidance of alcohol and tobacco use, prevention of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and other health hazards—a healthier pregnancy may result. Likewise, women who have health problems related to chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus can be counseled regarding their special needs with the intent to minimize maternal and fetal complications.

Initial Visit

Once the presence of pregnancy has been confirmed and the woman’s desire to continue the pregnancy has been validated, prenatal care is begun. The assessment process begins at the initial prenatal visit and is continued throughout the pregnancy. Assessment techniques include the interview, physical examination, and laboratory tests. Because the initial visit and follow-up visits are distinctly different in content and process, they are described separately.

Prenatal Interview

The pregnant woman and family members who may be present should be told that the first prenatal visit is longer and more detailed than future visits. The initial evaluation includes a

comprehensive health history emphasizing the current pregnancy, previous pregnancies, the family, a psychosocial profile, a physical assessment, diagnostic testing, and an overall risk assessment. A prenatal history form (paper or electronic) is used to document information obtained.

The therapeutic relationship between the nurse and the woman is established during the initial assessment interview. Two types of data are collected: the woman’s subjective appraisal of her health status and the nurse’s objective observations.

One or more family members often will accompany the pregnant woman. With her permission, include those accompanying the woman in the initial prenatal interview. Observations and information about the woman’s family are then included in the database. For example, if the woman has small children with her, the nurse can ask about her plans for child care during the time of labor and birth. Note any special needs at this time (e.g., wheelchair access, assistance in getting on and off the examining table, and cognitive deficits).

Reason for Seeking Care: Although pregnant women are scheduled for “routine” prenatal visits, they often come to the health care provider seeking information or reassurance about a particular concern. When the woman is asked a broad, open-ended question such as, “How have you been feeling?” she may reveal problems that could otherwise be overlooked. The woman’s chief concerns should be recorded in her own words to alert other personnel to the priority of needs as identified by her. At the initial visit the desire for information about what is normal in the course of pregnancy is typical.

Current Pregnancy: The presumptive signs of pregnancy may be of great concern to the woman. A review of symptoms she is experiencing and how she is coping with them helps establish a database to develop a plan of care. Some early teaching may be provided at this time.

Childbearing and Female Reproductive System History: Data are gathered on the woman’s age at menarche, menstrual history, and contraceptive history; the nature of any infertility or reproductive system conditions; a history of any STIs; a sexual history; and a detailed history of all her pregnancies, including the present pregnancy, and their outcomes. The date of the last Papanicolaou (Pap) test and the result are noted. The date of her LMP is obtained to calculate the EDB.

Health History: The health history includes those physical conditions or surgical procedures that may affect the pregnancy or that may be affected by the pregnancy. For example, a pregnant woman who has diabetes, hypertension, or epilepsy requires special care. Because most women are anxious during the initial interview, the nurse’s reference to cues, such as a MedicAlert bracelet, prompts the woman to explain allergies, chronic diseases, or medications being taken (i.e., cortisone, insulin, or anticonvulsants).

The woman should also describe the nature of previous surgical procedures. If a woman has undergone uterine surgery or extensive repair of the pelvic floor, a cesarean birth may be necessary; appendectomy rules out appendicitis as a cause of right lower quadrant pain in pregnancy; and spinal surgery may contraindicate the use of spinal or epidural anesthesia. Note any injury involving the pelvis.

Women who have chronic or handicapping conditions often forget to mention them during the initial assessment because they have become so adapted to them. Special shoes or a limp may indicate the existence of a pelvic structural defect, which is an important consideration in pregnant women. The nurse who observes these special characteristics and inquires about them sensitively can obtain individualized data that will provide the basis for a comprehensive nursing care plan (Smeltzer, 2007). Observations are vital components of the interview process because they prompt the nurse and woman to focus on the specific needs of the woman and her family.

Nutritional History: The woman’s nutritional history is an important component of the prenatal history because her nutritional status has a direct effect on the growth and development of the fetus. A dietary assessment can reveal special dietary practices, food allergies, eating behaviors, the practice of pica, and other factors related to her nutritional status (see Box 14-7). Obese women should receive counseling about weight gain, nutrition and food choices. They should also be advised about their risk for complications for themselves and increased risk for congenital abnormalities (Davies, Maxwell, McLeod, Gagnon, Basso, Bos, et al., 2010). Pregnant women are usually motivated to learn about good nutrition and respond well to nutritional advice generated by this assessment. Women who receive specific written and verbal information regarding nutrition, weight gain expectations, and exercise as well as weight gain reminders at each prenatal visit, are less likely to gain weight in excess of the IOM recommendations during pregnancy (Polley, Wing, & Sims, 2002).

History of Drug and Herbal Preparations Use: A woman’s past and present use of drugs (legal over-the-counter [OTC] and prescription medications; herbal preparations; caffeine; alcohol; nicotine) and illegal (e.g., marijuana, cocaine, heroin) is assessed. This is because many substances cross the placenta and may therefore harm the developing fetus. See Chapter 32 for discussion of substance abuse during pregnancy. Increasing numbers of individuals are using herbal preparations, and this includes pregnant women. Therefore, it is important for health care providers to question prenatal women regarding the use of herbal preparations and document their responses.

Family History: The family history provides information about the woman’s immediate family, including parents, siblings, and children. These data help identify familial or genetic disorders or conditions that could affect the present health status of the woman or her fetus.

Social, Experiential, and Occupational History: Situational factors such as the family’s ethnic and cultural background and socioeconomic status are assessed while the history is obtained. The following information may be obtained in several encounters. The woman’s perception of this pregnancy is explored by asking questions such as the following:

• Is this pregnancy planned or not, wanted or not?

• Is the woman pleased, displeased, accepting, or nonaccepting?

• What problems related to finances, career, or living accommodations will occur as a result of the pregnancy?

The family support system is determined by asking the following questions:

• What primary support is available to her?

• Are changes needed to promote adequate support?

• What are the existing relationships among the mother, father or partner, siblings, and in-laws?

• What preparations are being made for her care and that of dependent family members during labor and for the care of the infant after birth?

• Is financial, educational, or other support needed from the community?

• What are the woman’s ideas about childbearing, her expectations of the infant’s behavior, and her outlook on life and the female role?

Other questions that should be asked include the following:

• What does the woman think it will be like to have a baby in the home?

During interviews throughout the pregnancy nurses should remain alert to the appearance of potential parenting problems, such as depression, lack of family support, and inadequate living conditions. Nurses must assess the woman’s attitude toward health care, particularly during childbearing, her expectations of health care providers, and her view of the relationship between herself and the nurse.

Coping mechanisms and patterns of interacting are identified. Early in the pregnancy the nurse should determine the woman’s knowledge in various areas: pregnancy, maternal changes, fetal growth, self-care, and care of the newborn, including feeding. Asking about attitudes toward unmedicated or medicated childbirth and about her knowledge of the availability of parenting skills classes is important. Before planning for nursing care, the nurse needs information about the woman’s decision-making abilities and living habits (i.e., exercise, sleep, diet, diversional interests, personal hygiene, clothing). Common stressors during childbearing include the baby’s welfare, labor and birth process, behaviors of the newborn, the woman’s relationship with the baby’s father and her family, changes in body image, and physical symptoms.

Explore attitudes concerning the range of acceptable sexual behavior during pregnancy by asking questions such as the following: What has your family (partner, friends) told you about sex during pregnancy? Give emphasis to the woman’s sexual self-concept by asking questions such as the following: How do you feel about the changes in your appearance? How does your partner feel about your body now? How do you feel about wearing maternity clothes?

Women should be questioned regarding their occupation—past and present—because this may adversely affect maternal and fetal health. For some women, heavy lifting and exposure to chemicals and radiation may be part of their daily work, and these activities may negatively affect the pregnancy. Standing for long periods of time at a retail checkout line or in front of a classroom are associated with orthostatic hypotension. For others long hours of sitting at a desk working on a computer can contribute to carpal tunnel syndrome or circulatory stasis in the legs.

History of Physical Abuse: All women should be assessed for a history or risk of physical abuse, particularly because the likelihood of abuse increases during pregnancy. Although visual cues from the woman’s appearance or behavior may suggest the possibility, no one profile of the battered woman exists. During pregnancy the target body parts change during abusive episodes. Women report physical blows directed to the head, breasts, abdomen, and genitalia. Sexual assault is common.

Battering and pregnancy in teenagers constitutes a particularly difficult situation. Adolescents may be trapped in the abusive relationship because of their inexperience. Routine screening for abuse and sexual assault is recommended for pregnant adolescents (Family Violence Prevention Fund, 2010). Because pregnancy in young adolescent girls is commonly the result of sexual abuse, the nurse should assess the desire to maintain the pregnancy (see Chapter 5 for further discussion).

Review of Systems: During this portion of the interview, ask the woman to identify and describe preexisting or concurrent problems in any of the body systems, and assess her mental status. Question the woman about physical symptoms she has experienced, such as shortness of breath or pain. Pregnancy affects and is affected by all body systems; therefore, information on the present status of the body systems is important in planning care. For each sign or symptom described, the following additional data should be obtained: body location, quality, quantity, chronology, aggravating or alleviating factors, and associated manifestations (onset, character, course) (Seidel, Ball, Dains, Flynn, Soloman, & Stewart, 2011).

Physical Examination

The initial physical examination provides the baseline for assessing subsequent changes. The nurse should determine the woman’s needs for basic information regarding reproductive anatomy and provide this information, along with a demonstration of the equipment that may be used and an explanation of the procedure itself. The interaction requires an unhurried, sensitive, and gentle approach with a matter-of-fact attitude.

The physical examination begins with assessment of vital signs and height and weight (for calculation of body mass index [BMI]) (see Chapter 14). The bladder should be empty before pelvic examination. A urine specimen may be obtained to test for protein, glucose, or leukocytes or other tests.

Each examiner develops a routine for proceeding with the physical examination; most choose the head-to-toe progression. Heart and lung sounds are evaluated, and extremities are examined. Distribution, amount, and quality of body hair are of particular importance because the findings reflect nutritional status, endocrine function, and attention to hygiene. The thyroid gland is assessed carefully. The height of the fundus is noted if the first examination is done after the first trimester of pregnancy. During the examination the nurse must remain alert to the woman’s cues that give direction to the remainder of the assessment and that indicate a potential threatening condition such as supine hypotension—low blood pressure (BP) that occurs while the woman is lying on her back, causing feelings of faintness. See Chapter 4 for a detailed description of the physical examination.

Whenever a pelvic examination is performed, the tone of the pelvic musculature and the woman’s knowledge of Kegel exercises is assessed. Particular attention is paid to the size of the uterus because this is an indication of the duration of gestation. During the examination the nurse can coach the woman in breathing and relaxation techniques, as needed. One vaginal examination during pregnancy is recommended, but another is usually not performed unless medically indicated.

Laboratory Tests

The laboratory data yielded by the analysis of the specimens obtained during the examination provide important information concerning the symptoms of pregnancy and the woman’s health status.

Specimens are collected at the initial visit so that the cause of any abnormal findings can be treated (Table 15-1). Blood is drawn for a variety of tests. A sickle cell screen is recommended for women of African, Asian, or Middle Eastern descent, and testing for antibody to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is strongly recommended for all pregnant women (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], Workowski, & Berman, 2006) (Box 15-4). In addition, pregnant women and fathers with a family history of cystic fibrosis and of Caucasian ethnicity may elect to have blood drawn for testing to ascertain if they are a cystic fibrosis carrier (Norton, 2008). A urine specimen is collected for cultures and metabolic function tests. A purified protein derivative (PPD) tuberculin test may be administered to assess exposure to tuberculosis. During the pelvic examination, cervical and vaginal smears can be obtained for cytologic studies and for diagnosis of infection (e.g., gonorrhea, chlamydia).

TABLE 15-1

LABORATORY TESTS IN PRENATAL PERIOD

| LABORATORY TEST | PURPOSE |

| Hemoglobin, hematocrit, WBC, differential | Detects anemia; detects infection |

| Hemoglobin electrophoresis | Identifies women with hemoglobinopathies (e.g., sickle cell anemia, thalassemia) |

| Blood type, Rh, and irregular antibody | Identifies those fetuses at risk for developing erythroblastosis fetalis or hyperbilirubinemia in neonatal period |

| Rubella titer | Determines immunity to rubella |

| Tuberculin skin testing; chest film after 20 weeks of gestation in women with reactive tuberculin tests | Screens for exposure to tuberculosis |

| Urinalysis, including microscopic examination of urinary sediment; pH, specific gravity, color, glucose, albumin, protein, RBCs, WBCs, casts, acetone; hCG | Identifies women with glycosuria, renal disease, hypertensive disease of pregnancy; infection; occult hematuria |

| Urine culture | Identifies women with asymptomatic bacteriuria |

| Renal function tests: BUN, creatinine, electrolytes, creatinine clearance, total protein excretion | Evaluates level of possible renal compromise in women with a history of diabetes, hypertension, or renal disease |

| Pap test | Screens for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; if a liquid-based test is used, may also screen for HPV |

| Cervical cultures for Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia | Screens for asymptomatic infection at first visit |

| Vaginal/anal culture | GBS test done at 35-37 weeks for infection |

| RPR, VDRL, or FTA-ABS | Identifies women with untreated syphilis, done at first visit |

| HIV antibody, hepatitis B surface antigen, toxoplasmosis | Screens for the specific infections |

| 1-hour glucose tolerance | Screens for gestational diabetes; done at initial visit for women with risk factors; done at 24-28 weeks for pregnant women at risk whose initial screen was negative; women with low risk usually not tested |

| 3-hour glucose tolerance | Tests for gestational diabetes in women with elevated glucose level after 1-hour test; must have two elevated readings for diagnosis |

| Cardiac evaluation: ECG, chest x-ray, and echocardiogram | Evaluates cardiac function in women with a history of hypertension or cardiac disease |

BUN, Blood urea nitrogen; ECG, electrocardiogram; FTA-ABS, fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test; GBS, group B streptococci; hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HPV, human papillomavirus; RBC, red blood cell; RPR, rapid plasma reagin; VDRL, Venereal Disease Research Laboratory; WBC, white blood cell.

The finding of risk factors during pregnancy may indicate the need to repeat some tests at other times. For example, exposure to tuberculosis or an STI would necessitate repeat testing after treatment. STIs are common in pregnancy and may have negative effects on mother and fetus. Careful assessment and screening are essential.

Follow-up Visits

In traditional prenatal care, monthly visits are scheduled routinely during the first and second trimesters, although clients can make additional appointments as the need arises. During the third trimester, however, the possibility for complications increases, and closer monitoring is necessary. Starting with week 28, maternity visits are scheduled every 2 weeks until week 36 and then every week until birth, unless the health care provider individualizes the schedule. Visits can occur more or less frequently, often depending on individual needs, complications, and risks of the pregnant woman. The pattern of interviewing the woman first and then assessing physical changes and performing laboratory tests continues.

In prenatal care models that use a reduced frequency screening schedule or in CenteringPregnancy, the timing of follow-up visits will be different, but assessments and care will be similar.

Interview

Follow-up visits are less intensive than the initial prenatal visit. At each of these follow-up visits, the woman is asked to summarize relevant events that have occurred since the previous visit. She is asked about her general emotional and physiologic well-being, complaints, problems, and questions she may have. Personal and family needs also are identified and explored (Fig. 15-6).

Emotional changes are common during pregnancy, and therefore asking whether the woman has experienced any mood swings, reactions to changes in her body image, bad dreams, or worries is reasonable. Note any positive feelings (her own and those of her family). Record the reactions of family members to the pregnancy and the woman’s emotional changes.

During the third trimester, assess current family situations and their effect on the woman. For example, assess siblings’ and grandparents’ responses to the pregnancy and the coming child. In addition, assess of the woman and her family’s knowledge of warning signs of emergencies; signs of preterm and term labor; the labor process and concerns about labor; and fetal development and methods to assess fetal well-being. The nurse should ask if the woman is planning to attend childbirth preparation classes and what she knows about pain management during labor.

A review of the woman’s physical systems is appropriate at each prenatal visit, and any suspicious signs or symptoms are assessed in depth. Identify any discomforts reflecting adaptations to pregnancy. Inquire about success with self-care measures as well as outcomes of prescribed therapy.

Physical Examination

Reevaluation is a constant aspect of a pregnant woman’s care. Physiologic changes are documented as the pregnancy progresses and reviewed for possible deviations from normal progress.

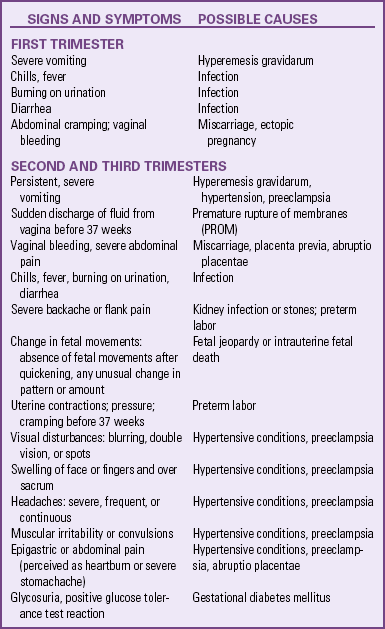

At each visit physical parameters are measured. BP is measured using the same arm at every visit (see Box 13-1). The woman’s weight is assessed, and the appropriateness of the gestational weight gain is evaluated in relationship to her BMI. Urine may be checked by dipstick, and the presence and degree of edema are noted. For examination of the abdomen, the woman lies on her back with her arms by her side and head supported by a pillow. The bladder should be empty. Abdominal inspection is followed by measurement of the height of the fundus (see Fig. 15-7). While the woman lies on her back, the nurse should be alert for the occurrence of supine hypotension. When a pregnant woman is lying in this position, the weight of the abdominal contents may compress the vena cava and aorta, causing a decrease in BP and a feeling of faintness (see the Emergency box).

The information provided through the interview and the physical examination reflects the status of maternal adaptations. When any of the findings are suspicious, an in-depth examination is performed. For example, careful interpretation of BP is important in the risk factor analysis of all pregnant women. Signs and symptoms other than hypertension also may be present that indicate potential complications (see the Signs of Potential Complications box).

Fetal Assessment

Listening for Fetal Heart Tones: Toward the end of the first trimester, before the uterus is an abdominal organ, the fetal heart tones (FHTs) can be heard with an ultrasound fetoscope or an ultrasound stethoscope (see Fig. 15-8). To hear the FHTs, place the instrument in the midline, just above the symphysis pubis, and apply firm pressure. Offer the woman and her family the opportunity to listen to the FHTs.

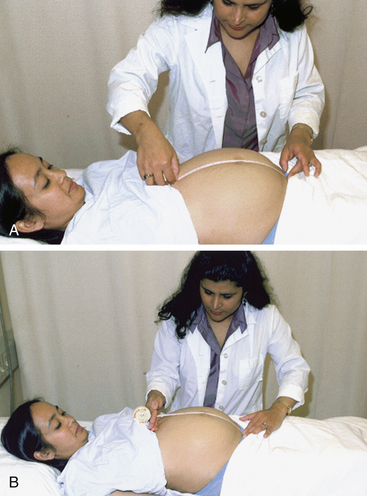

Measuring Fundal Height: During the second trimester the uterus becomes an abdominal organ. The fundal height (measurement of the height of the uterus above the symphysis pubis) is used as one indicator of fetal growth. The measurement also provides a gross estimate of the duration of pregnancy. From gestational weeks (GW) 18 to 32, the height of the fundus in centimeters is approximately the same as the number of weeks of gestation (± 2 GW), if the woman’s bladder is empty at the time of measurement. As much as a 3-cm variation is possible if the bladder is full (Cunningham, Leveno, Bloom, Hauth, Rouse, & Spong, 2010). For example, a woman of 28 weeks of gestation, with an empty bladder, would measure from 26 to 30 cm. In addition, the fundal height measurement may aid in the identification of high risk factors. A stable or decreased fundal height

may indicate the presence of intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR); an excessive increase could indicate the presence of multifetal gestation (more than one fetus) or polyhydramnios.

A disposable paper metric tape measure is preferred for measuring fundal height; plastic retractable tape measures should be cleaned after use and prior to retraction. To increase the reliability of the measurement, the same person examines the pregnant woman at each of her prenatal visits, but often this is not possible. All clinicians who examine a particular pregnant woman should be consistent in their measurement technique. Ideally, a protocol should be established for the health care setting in which the measurement technique is explicitly set forth, and the woman’s position on the examining table, the measuring device, and method of measurement used are specified. Conditions under which the measurements are taken also can be described in the woman’s records, including whether the bladder was empty and whether the uterus was relaxed or contracted at the time of measurement.

Various positions for measuring fundal height have been described. The woman can be supine, have her head elevated, have her knees flexed, or have both her head elevated and knees flexed. Measurements obtained with the woman in the various positions differ, making it even more important to standardize the fundal height measurement technique.

Placement of the tape measure also can vary. The tape can be placed in the middle of the woman’s abdomen and the measurement made from the upper border of the symphysis pubis to the upper border of the fundus, with the tape measure held in contact with the skin for the entire length of the uterus (Fig. 15-7, A). In another measurement technique, the upper curve of the fundus is not included in the measurement. Instead, one end of the tape measure is held at the upper border of the symphysis pubis with one hand, and the other hand is placed at the upper border of the fundus. The tape is placed between the middle and index fingers of the other hand, and the point where these fingers intercept the tape measure is taken as the measurement (see Fig. 15-7, B).

Gestational Age: In an uncomplicated pregnancy fetal gestational age is estimated after the duration of pregnancy and the EDB are determined. Fetal gestational age is determined from the menstrual history, contraceptive history, pregnancy test result, and the following findings obtained during the clinical evaluation:

• First uterine evaluation: date, size

• Fetal heart first heard: date, method (Doppler stethoscope, fetoscope)

• Current fundal height, estimated fetal weight (EFW)

• Current week of gestation by history of LMP and/or ultrasound examination

• Ultrasound examination: date, week of gestation, biparietal diameter (BPD)

Quickening usually occurs between 16 and 20 weeks of gestation and is initially experienced as a fluttering sensation. The mother’s report should be recorded. Multiparas often perceive fetal movement earlier than primigravidas.

The use of ultrasound examination (also called a sonogram) in early pregnancy has become routine, and many health care providers have this equipment available in the office. This procedure may be used to establish the duration of pregnancy if the woman cannot give a precise date for her LMP or if the size of the uterus does not conform to the EDB as calculated by Nägele’s rule. Ultrasound also provides information about the well-being of the fetus (see Chapter 26 for further discussion). However, the routine use of ultrasound has not been found to substantively improve fetal outcome (Hunter, 2009).

Health Status: The assessment of fetal health status includes consideration of fetal movement. The mother is instructed to note the extent and timing of fetal movements and to report immediately if the pattern changes or if movement ceases. Regular movement has been found to be a reliable indicator of fetal health (Frøen, Heazell, Tveit, Saastad, Fretts, & Flenday, 2008) (see Chapter 26).

The fetal heart rate (FHR) is checked on routine visits once it has been heard (Fig. 15-8). Early in the second trimester, the heartbeat may be heard with a Doppler stethoscope (see Fig. 15-8, B). To detect the heartbeat before the fetal position can be palpated by Leopold maneuvers (see Chapter 19), the scope is moved around the abdomen until the heartbeat is heard. Each nurse develops a set pattern for searching the abdomen for the heartbeat—for example, starting first in the midline about 2 to 3 cm above the symphysis, then moving to the left lower quadrant, and so on. The heartbeat is counted for 1 minute, and the quality and rhythm noted. Later in the second trimester, the FHR can be determined with a fetoscope or a Pinard fetoscope (see Fig. 15-8, A and C). A normal rate and rhythm are other good indicators of fetal health. Once the heartbeat is noted, its absence is cause for immediate investigation.

FIG. 15-8 Detecting fetal heart rate. A, Father listens to the fetal heart (first detectable around 18 to 20 weeks) with a fetoscope. B, Doppler ultrasound stethoscope (fetal heartbeat detectable at 12 weeks). C, Pinard fetoscope. Note: Hands should not touch fetoscope while listening. (A, Courtesy Shannon Perry, Phoenix, AZ; B, courtesy Dee Lowdermilk, Chapel Hill, NC; C, courtesy Julie Perry Nelson, Loveland, CO.)

Fetal health status is investigated intensively if any maternal or fetal complications arise (e.g., gestational hypertension, IUGR, premature rupture of membranes [PROM], irregular or absent FHR, or decreased/absent fetal movements after quickening). Careful, precise, and concise recording of client responses and laboratory results contributes to the continuous supervision vital to ensuring the well-being of the mother and fetus.

Laboratory Tests

The number of routine laboratory tests done during follow-up visits in pregnancy is limited. A clean-catch urine specimen is obtained to test for glucose, protein, nitrites, and leukocytes at each visit. Urine specimens for culture and sensitivity are obtained, and cervical and vaginal smears and blood tests are repeated as necessary.

First-trimester screening for chromosomal abnormalities is offered as an option between 11 and 14 weeks. This multiple marker screen includes sonographic evaluation of nuchal translucency (NT) and biochemical markers—pregnancy-associated placental protein (PAPP-A) and free beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG).

Maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein (MSAFP) screening is recommended between 15 and 22 GW, ideally between 16 and 18 weeks of gestation. Elevated levels are associated with open neural tube defects and multiple gestations, whereas low levels are associated with Down syndrome. The multiple-marker, or triple-screen, blood test is also recommended. Done between 16 and 18 weeks of gestation, it measures the MSAFP, hCG, and unconjugated estriol, the levels of which are combined to yield one value. Maternal serum marker levels that are higher or lower than normal are associated with chromosomal abnormalities (see Chapter 26). If not done earlier in pregnancy, a glucose screen is obtained for women at high risk for gestational diabetes between 24 and 28 weeks of gestation. GBS testing is done between 35 and 37 weeks of gestation; cultures collected earlier will not accurately predict GBS status at time of birth (Van Dyke, Phares, Lynfield, Thomas, Arnold, Craig, et al., 2009).

Other diagnostic tests, such as amniocentesis, are available to assess the health status of both the pregnant woman and the fetus (See Chapter 26 for further discussion).

Collaborative Care

After obtaining information through the assessment process, the data are analyzed to identify deviations from the norm and unique needs of the pregnant woman and her family.

The nurse-client relationship is critical in setting the tone for further interaction. The techniques of listening with an attentive expression, touching, and using eye contact have their place, as does recognizing the woman’s feelings and her right to express these feelings. The interaction may occur in various formal or informal settings. A clinical setting, home visits, or telephone conversations all provide opportunities for contact and can be used effectively.

In supporting a woman, the nurse must remember that both the nurse and the woman are contributing to the relationship. The nurse has to accept the woman’s responses as a factor in trying to be of help. An example of one nurse-client relationship is as follows:

Keisha has been very forthright in saying that this pregnancy was unplanned but had countered this observation with comments such as, “All things happen for the best,” and “Children bring their own love.” Over time, as our relationship developed to one of mutual trust, she complained increasingly of her fear of pain, of hating to wear maternity clothes, and of having to give up helping the family. Finally I ventured to say, “Sometimes when a pregnancy is unplanned, women resent it and are angry about it.” Her relief was evident. She said, “You don’t know how angry I’ve been.” As a result, the whole tenor of support being offered changed, and the plan was adjusted to meet her real needs.

The nurse also must accept that the woman must be a willing partner in a purely voluntary relationship. As such, the relationship can be refused or terminated at any time by the pregnant woman or her family.

Supportive care involves developing, augmenting, or changing the mechanisms used by women and their families in coping with stress. The nurse tries to promote active participation by the family in the solution of their own problems. The nurse can help a woman gather pertinent information, explore options, decide on a course of action, and assume responsibility for the outcomes. These outcomes may include living with a problem as it is, easing the effects of a problem so that it can be accepted more readily, or eliminating the problem by effecting change.

At other times a successful outcome can be documented readily. For example, a woman who early in her pregnancy had predicted a severe depressive state in the post-birth period was elated when such a state did not materialize. She remarked to the nurse who had provided support during the labor and birth, “You’re the best nerve medicine I’ve ever had!”

Education About Maternal and Fetal Changes

Expectant parents are typically curious about the growth and development of the fetus and the subsequent changes that occur in the mother’s body. Mothers in particular are sometimes more tolerant of the discomforts related to the continuing pregnancy if they understand the underlying causes. Educational literature that describes fetal and maternal changes is available and can be used in explaining changes as they occur. The nurse’s familiarity with any material shared with pregnant families is essential to effective client education. Educational material may include electronic and written materials appropriate to the pregnant woman’s or couple’s literacy level and experience and the agency’s resources. It is important that available educational materials reflect the pregnant woman’s or couple’s ethnicity, culture, and literacy level to be most effective.

Education for Self-Management

The expectant mother needs information about many subjects. The nurse who is observant, listens, and knows typical concerns of expectant parents can anticipate questions that will be asked and prompt mothers and partners to discuss what is on their minds. Many times, printed literature can be given to supplement the individualized teaching the nurse provides, and women often avidly read books and pamphlets related to their own experience. When nurses read the literature before they distribute it, they can point out areas that may not correspond with local health care practices. Because family members are common sources for health information, it is also important to include them in the health education endeavors (Yamashita, 2009). In addition, as more individuals use the computer for information, the pregnant woman or couple may have questions from their Internet reviews. Nurses may also share recommended electronic sites from reliable sources.

Pregnant women who receive conflicting advice or instruction are likely to grow increasingly frustrated with members of the health care team and the care provided. Several topics that may cause concerns in pregnant women are discussed in the following sections.