Blood and Plasma Proteins

Introduction

For a clinician, plasma is an important ‘window’ on metabolism

Blood is the transport and distribution medium for the body. It delivers essential nutrients to tissues and removes waste products. It is an aqueous solution containing molecules of varying sizes, and a number of cellular elements. Some of the components of blood perform important roles in the body's defense against external insult and in the repair of damaged tissues. For a clinician, plasma is also an important ‘window’ on metabolism. Because it is easy to collect, most of the diagnostic laboratory tests in biochemistry, hematology and immunology are performed on plasma samples.

Plasma is the natural environment of blood cells, but many chemical measurements are done with serum

The formed elements of blood are suspended in an aqueous solution: the plasma. Plasma is the supernatant obtained after centrifugation of blood collected into a test tube containing anticoagulant to prevent clotting. Several anticoagulants are used in laboratory practice, the most common being lithium heparinate and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). Heparinate prevents clotting by binding to thrombin. EDTA and citrate bind Ca2+ and Mg2+, thus interfering with the action of calcium and magnesium-dependent enzymes involved in the clotting cascade (Chapter 7). Citrate is used as an anticoagulant when blood is collected for transfusion.

Serum, on the other hand, is the supernatant obtained after a blood sample has been allowed to clot spontaneously (this usually requires 30–45 minutes). During clotting, fibrinogen is converted to fibrin as a result of proteolytic cleavage by thrombin, and so a major difference between plasma and serum is the absence of fibrinogen in serum.

Throughout this book, when we describe physiologic or pathologic mechanisms, we refer to plasma; e.g. we would say that albumin binds many drugs present in plasma. We may mention serum when we specifically refer to the results of laboratory tests specifically performed on serum; e.g. we would say that patient's serum albumin was 40 mg/dL.

Formed Elements of Blood

There are three major cellular components of blood: the red blood cells (erythrocytes), the white blood cells (leukocytes) and the blood platelets (thrombocytes).

Erythrocytes are not complete cells, as they do not possess nuclei and intracellular organelles

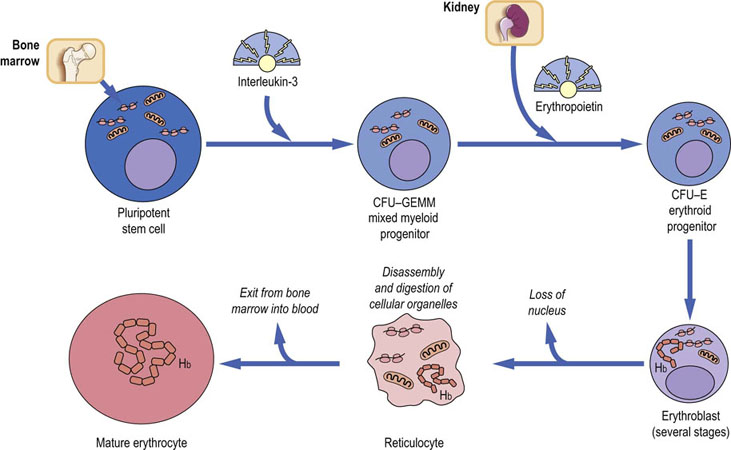

The erythrocytes are cellular remnants, containing specific proteins and ions, which can be present in high concentrations. They are the end-product of erythropoiesis in the bone marrow, which is under the control of erythropoietin produced by the kidney (Fig. 4.1). Hemoglobin is synthesized in the erythrocyte precursor cells (erythroblasts and reticulocytes) under a tight control dictated by the concentration of heme (Chapter 30). The main functions of erythrocytes are the transport of oxygen and the removal of carbon dioxide and hydrogen ions; as they lack cellular organelles, they are not capable of protein synthesis and repair (Chapters 5 and 25). As a result, erythrocytes have a finite life span of approximately 120 days before being trapped and broken down in the spleen.

Fig. 4.1 Simplified scheme of the formation of erythrocytes.

In an average day, 1011 erythrocytes are formed. Hemoglobin is synthesized in the erythrocyte and reticulocyte before the loss of ribosomes and mitochondria. CFU-GEMM, colony-forming unit: granulocyte, erythroid, monocyte, megakaryocyte; CFU-E, colony-forming unit erythroid.

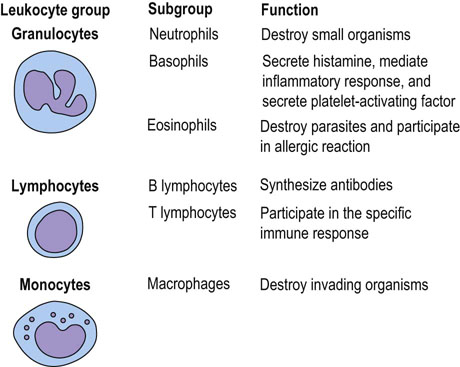

Leukocytes are cells, the main function of which is to protect the body from infection (Chapter 38)

Most leukocytes are produced in the bone marrow, some are produced in the thymus, and others mature within several tissues (Fig. 4.2) (Chapter 38). Leukocytes can control their own synthesis by secreting into the blood signal peptides that subsequently act on the bone marrow stem cells. In order to function correctly, leukocytes have the ability to migrate out of the bloodstream into surrounding tissues.

Fig. 4.2 Leukocytes.

Classification and functions of leukocytes (see also Chapter 38).

Thrombocytes are not true cells, but are membrane-bound fragments derived from megakaryocytes

They reside in the bone marrow. They play a key role in blood clotting (Chapter 7).

Plasma Proteins

Plasma proteins can be broadly classified into two groups: those, including albumin, that are synthesized by the liver, and the immunoglobulins, which are produced by plasma cells of the bone marrow, usually as part of the immune response.

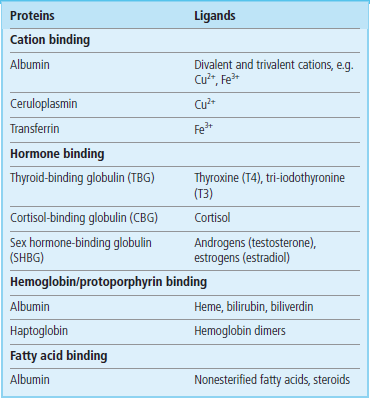

A number of plasma proteins have the ability to bind certain molecules (their ligands) with a high affinity and specificity. These proteins can then act as a reservoir for the ligand and help control its distribution and availability by transporting it to tissues. Binding to a protein can also render a toxic substance less harmful to the tissues. Major binding proteins and their ligands are shown in Table 4.1.

Albumin

Albumin serves as an osmotic regulator and is a major transport protein

Albumin is the predominant plasma protein. It has no known enzymatic or hormonal activity, and accounts for approximately 50% of the protein found in human plasma. Its normal concentration is 35–45 g/L. With a molecular weight of about 66 kDa, albumin has highly polar nature and dissolves easily in water. At pH 7.4, it is an anion with 20 negative charges per molecule; this gives it a high capacity for non-selective binding of many ligands. It also plays a critical role in maintaining colloid osmotic pressure of the plasma.

The rate of albumin synthesis (14–15 g daily) depends on nutritional status, especially on the extent of amino acid deficiencies. Its half-life is about 20 days. Importantly, although the albumin level reflects the nutritional status in the longer term, in hospitalized patients the short-term changes in plasma albumin concentration are usually due to changes in hydration (Chapter 24).

Albumin is the primary plasma protein responsible for the transport of hydrophobic fatty acids, bilirubin, and drugs

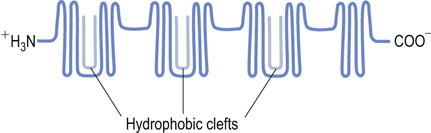

Albumin can bind (and thus solubilize) a range of substances that include the long-chain fatty acids, sterols, and several synthetic compounds. The transport of long-chain fatty acids underpins much of the body's distribution of energy-rich substrates. There are numerous fatty acid binding sites on the albumin molecule, with variable affinities. The highest affinity sites are believed to lie in the globular segments within specialized clefts of the albumin molecule (Fig. 4.3).

Fig. 4.3 Molecular model of human albumin.

The hydrophobic clefts are globular segments of albumin that bind fatty acids with high affinity.

In addition to binding fatty acids, albumin binds unconjugated bilirubin (Chapter 30). The sites within the albumin molecule are also capable of binding a variety of drugs, including salicylates, barbiturates, sulfonamides, penicillin and warfarin. This is of great pharmacologic relevance. Such interactions are weak and the ligands become easily displaced by substances competing for a binding site. Somewhat surprisingly, albumin is not essential for human survival and rare congenital defects have been described where there is hypoalbuminemia or complete absence of albumin (analbuminemia).

Proteins that transport metal ions

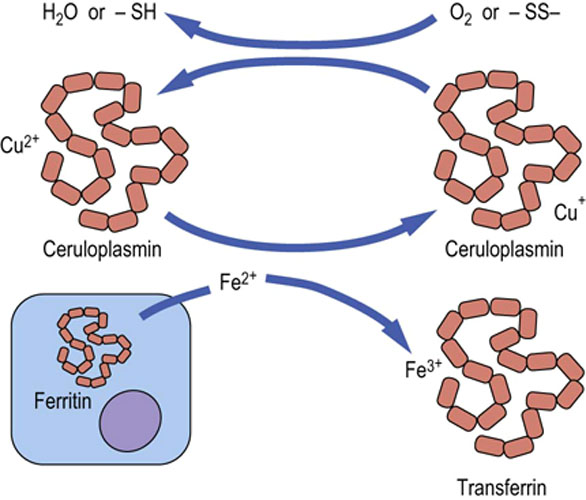

Transferrin transports iron

The binding of ferric ions (Fe3+) to transferrin protects against the toxic effects of these ions. In inflammatory reactions, the iron–transferrin complex is degraded by the reticuloendothelial system without a corresponding increase in the synthesis of either of its components; this results in low plasma concentrations of transferrin and iron (Chapter 11).

Ferritin is the major iron storage protein found in almost all cells of the body

Ferritin acts as the reserve of iron in the liver and bone marrow. The concentration of ferritin in plasma is proportional to the amount of stored iron; therefore measurement of plasma ferritin is one of the best indicators of iron deficiency.

Ceruloplasmin is the major transport protein for copper

Ceruloplasmin helps export copper from the liver to peripheral tissues, and is essential for the regulation of the oxidation reduction reactions, transport, and utilization of iron (Fig. 4.4). Increased concentrations of ceruloplasmin occur in active liver disease and in tissue damage.

Immunoglobulins

Immunoglobulins are proteins produced in response to foreign substances (antigens; see Chapter 38)

Immunoglobulins (antibodies) are secreted by the B lymphocytes. They have defined specificity for foreign substances that stimulated their synthesis. Not all foreign substances entering the body can elicit this response, however; those that do are called immunogens, whereas any agent that can be bound by an antibody is termed an antigen. The immunoglobulins form a uniquely diverse group of molecules, recognizing and reacting with a wide range of specific antigenic structures (epitopes) and giving rise to a series of effects that result in the eventual elimination of the presenting antigen. Some immunoglobulins have additional effector functions; for example, IgG is involved in complement activation.

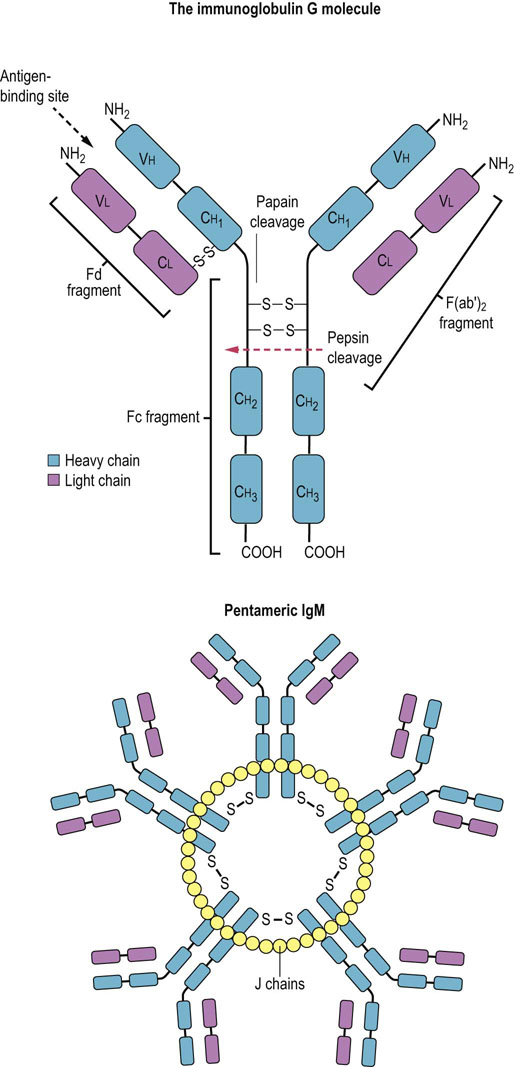

Immunoglobulins share a common Y-shaped structure of two heavy and two light chains

An immunoglobulin is a Y-shaped molecule containing two identical units termed heavy (H) chains and two identical, but smaller, units termed light (L) chains. Several H chains exist, and the nature of the H chain determines the class of immunoglobulin: IgG, IgA, IgM, IgD and IgE are characterized by α, γ, δ, µ, and ε heavy chains, respectively. L chains are of only two types, κ and λ. Each polypeptide chain within the immunoglobulin is characterized by a series of globular regions, which have considerable sequence homology and, in evolutionary terms, are probably derived from protogene duplication.

The N-terminal domains of both H and L chains contain a region of variable amino acid sequence (the V region); together, these regions determine antigenic specificity. Both H and L chains are required for full antibody activity, as the physically apposed V regions in the L and H chains form a functional pocket into which the epitope fits; this is termed the antibody recognition (F(ab′2)) region. The domain immediately adjacent to the V region is much less variable, in both H and L chains. The remainder of the H chain consists of a further constant region (Fc region) consisting of a hinge region and two additional domains. The constant region is responsible for immunoglobulin functions other than epitope recognition, such as complement activation (Chapter 38). This basic structure of immunoglobulins is depicted in Figure 4.5. When antigen binds to the immunoglobulin, conformational changes are transmitted through the hinge region of the antibody to the Fc region, which is then said to have become activated.

Fig. 4.5 The structure of immunoglobulins.

Diagrammatic representation of the basic structure of a monomeric immunoglobulin and that of pentameric immunoglobulin (IgM). V, variable region; C, constant region; H, heavy chain; L, light chain; J chain, joining chain; F(ab′)2, fragment generated by pepsin cleavage of the molecule; Fc, Fd, fragments generated by papain proteolysis.

Major immunoglobulins

IgG is the most common immunoglobulin that protects tissue spaces and freely crosses the placenta

IgG, with an overall molecular mass of 160 kDa, consists of the basic 2H2L immunoglobulin subunit joined by a variable number of disulfide bonds. The γ H chains have several antigenic and structural differences, allowing classification of IgG into a number of subclasses according to the type of H chain present; however, functional differences between the subclasses are minor.

IgG circulates in high concentrations in the plasma, accounting for 75% of immunoglobulin present in adults, and has a half-life of 22 days. It is present in all extracellular fluids, and appears to eliminate small, soluble antigenic proteins through aggregation and enhanced phagocytosis by the reticuloendothelial system. From weeks 18–20 of pregnancy, IgG is actively transported across the placenta and provides humoral immunity for the fetus and neonate before maturation of the immune system.

IgA is found in secretions and presents an antiseptic barrier, which protects mucosal surfaces

IgA has an H chain similar to the γ chain of IgG, and α chains possess an extra 18 amino acids at its C-terminus. The extra peptide sequence enables the binding of a ‘joining’ or J chain. This short (129-residue) acidic glycopeptide, synthesized by plasma cells, allows dimerization of secretory IgA. IgA is often found in noncovalent association with the so-called secretory component, a highly glycosylated 71 kDa polypeptide, synthesized by mucosal cells and capable of protecting IgA against proteolytic digestion.

IgA represents 7–15% of plasma immunoglobulins and has a half-life of 6 days. It is found, in particular in the dimerized form, in parotid, bronchial, and intestinal secretions. It is a major component of colostrum (the first milk from the mother's breasts after the birth of a child). IgA appears to function as the primary immunologic barrier against pathogenic invasion of mucous membranes. It can promote phagocytosis, cause eosinophilic degranulation, and activate complement via the so-called alternative pathway.

IgM is confined to the intravascular space and helps eliminate circulating antigens and microorganisms

Immunoglobulins belonging to this final major class are polyvalent, with a high molecular mass. IgM has a basic form similar to that of IgA, having the extra H chain domain that allows for J chain binding, and is thus capable of polymerization. IgM normally circulates as a pentamer, with a molecular mass of 971 kDa, linked by disulfide bonds and the J chain (Fig. 4.5).

IgM accounts for 5–10% of plasma immunoglobulins and has a half-life of 5 days. With its polymeric nature and high molecular mass, most IgM is found confined to the intravascular space, although lesser amounts may be found in secretions, usually in association with secretory component. It is the first antibody to be synthesized after an antigenic challenge.

Minor immunoglobulins

IgD is the surface receptor for antigen in B lymphocytes

IgD differs from the standard immunoglobulin structure chiefly by its high carbohydrate content of numerous oligosaccharide units, resulting in an increased molecular mass of 190 kDa. Its δ chains are characterized by having only a single interconnecting disulfide bridge, and an elongated hinge region that is particularly susceptible to proteolysis.

IgD accounts for less than 0.5% of circulating plasma immunoglobulin mass. Its role remains elusive although, as a surface component of the mature B cells, it probably has some role in the response to antigens. Rare cases of isolated IgD deficiency seem to be associated with no obvious pathology.

IgE binds antigens and promotes release of vasoactive amines from mast cells

IgE is similar to IgM in its unit structure. It has ε heavy chains that consist of five, rather than four, domains, but J chain binding and polymerization do not occur. The extended H chain helps to explain its high molecular mass of approximately 200 kDa. It is present only in trace amounts in plasma.

IgE has a high affinity for binding sites on mast cells and basophils. Antigenic binding at the Fab2 region induces crosslinking of the high-affinity receptor, granulation of the cell, and release of vasoactive amines. By this mechanism, IgE plays a major part in allergy/atopy and mediates antiparasitic immunity.

Monoclonal immunoglobulins are the product of a single B cell, and arise from benign or malignant transformations of B cells

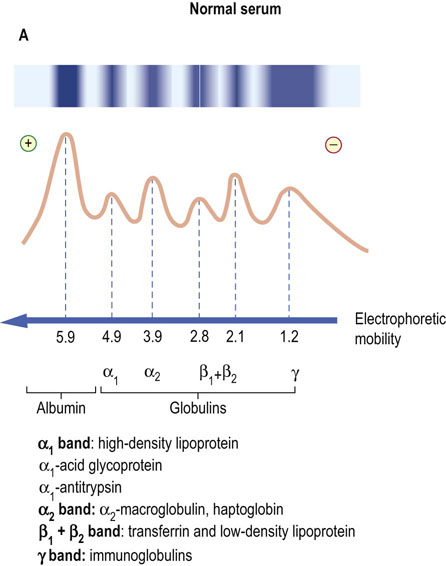

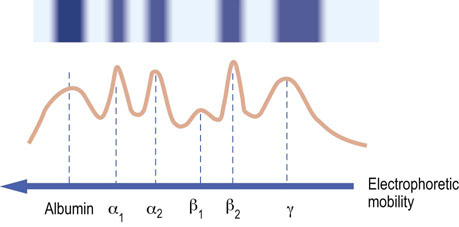

Monoclonal immunoglobulins result from the proliferation of a single B cell clone, which thus produces identical antibodies. Usually these are structurally normal molecules but sometimes they may be in some way fragmented or truncated. On gel electrophoresis, monoclonal immunoglobulin forms a single band in the γ region (the paraprotein band) (Fig. 4.6).

Fig. 4.6 Comparison of gel electrophoretic appearance of normal serum and that containing monoclonal immunoglobulins.

The scanning pattern peaks (solid line) represent the relative concentrations of the separated proteins. (A) Normal serum. (B) Monoclonal gammopathy: a strongly stained band is present in the γ-globulin region on electrophoresis, and there is an associated reduction of staining in the remainder of the γ-region (immunoparesis).

Monoclonal immunoglobulins are associated with malignant pathologies such as myeloma and Waldenström's macroglobulinemia, and also with more benign transformations that are known as monoclonal gammopathies of uncertain significance (MGUS).

The Acute Phase Response and C-Reactive Protein

The acute phase response is a nonspecific response to tissue injury or infection; it affects several organs and tissues

During the acute phase response, there is a characteristic marked increase in the synthesis of some proteins (predominantly in the liver), along with a decrease in the plasma concentration of some others (Fig. 4.7). An increase in the synthesis of proteins such as proteinase inhibitors (α1-antitrypsin), coagulation proteins (fibrinogen, prothrombin), complement proteins, and C-reactive protein is of obvious clinical benefit. The synthesis of albumin, transthyretin (prealbumin), and transferrin decreases during the acute phase response, and they are thus termed the ‘negative acute phase reactants’.

Fig. 4.7 Acute phase response.

Gel electrophoretic pattern observed in serum during the acute phase response. Albumin is decreased, the sum of α1- and α2-globulins is increased, β1-globulins are decreased, β2-globulins are increased and there is a mild increase in γ-globulins. Compare this to the normal pattern shown in Fig. 4.6A.

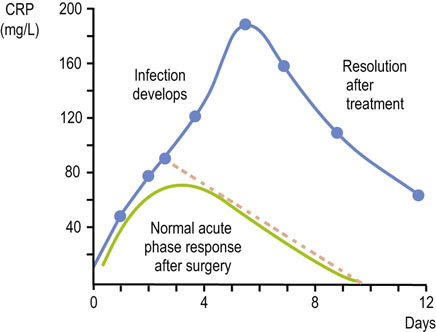

C-reactive protein (CRP) is a major component of the acute phase response and a marker of bacterial infection

CRP is synthesized in the liver and is constructed of five polypeptide subunits. It has a molecular mass of around 130 kDa. It is present in only minute quantities (<1 mg/L in normal serum) and is believed to bind to phospholipids, and some proteins on invading microorganisms or damaged cells, facilitating activation of the complement via the classic pathway (Chapter 38). Measurement of CRP concentration in plasma is an essential laboratory test in diagnosis and monitoring of infection and sepsis (Fig. 4.8).

Fig. 4.8 C-reactive protein (CRP) and the postoperative acute phase reaction.

The concentration of CRP increases as part of the acute phase response to surgical trauma, and a further increase may be observed if recovery is complicated by infection (the dotted line represents a response to uncomplicated surgery).

High sensitivity CRP assay is used in the assessment of cardiovascular risk

An assay for CRP, which is approximately 100 times more sensitive than the conventional CRP measurement method, detects minimal fluctuations in the concentration of this protein in infection-free individuals. Very small increases in CRP concentration seem to reflect a state of chronic low-grade inflammation associated, for instance, with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (Chapter 18). Other inflammatory conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease, type 2 diabetes and the metabolic syndrome have been associated with these minute increases in serum CRP concentration.

Clinical Tests: Biomarkers

Clinical laboratories perform a large number of biochemical analyses on body fluids to provide answers to specific clinical questions

The majority of specimens received by the laboratory are blood and urine samples. Whereas some measurements are performed on whole blood, serum or plasma are preferred for most analyses of metabolites and ions. In general, the time devoted to the analysis of each sample is short, but the entire process from a request for analysis to receipt of a result involves many steps. Throughout the process, constant checking and quality assurance are performed to ensure that the produced results are analytically and clinically valid. An outline of the laboratory workflow is shown in Figure 4.3.

Today's clinical laboratories rely, much like modern genetics research labs, on high throughput-automated instruments and robotic technologies

A high degree of automation and the underlying information technology allow us to perform large numbers of analyses, while enabling customized sets of hematology and biochemistry tests, (see Appendix 1). It is the logistics of specimen transport to the laboratory, rather than analysis itself, which in many instances becomes the factor that limits the workflow.

Discovering new biomarkers

A biomarker is an indicator of biological state, or a characteristic that is measured as an indicator or normal or pathologic process

Such a marker can be used for screening and risk assessment, diagnosis and detection of clinical conditions, or for monitoring of treatment and its side effects. The process of discovery of new biomarkers is now driven by the application of -omic technologies: genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics and metabolomics (Chapter 36). Blood and urine samples remain the most important materials for biomarker discovery.

Metabolomics explores patterns of small molecules

Metabolomics is the study of all metabolites generated in the organism, including the metabolites of drugs, food-derived compounds and substances generated by the microbial flora

The Human Metabolome Database (version 2.5) contains around 7900 metabolites. The exploration of metabolites is a process located downstream from genomics and transcriptomics – the study of genes and their expression, respectively (Chapter 36). Metabolomic methodologies allow exploration of entire pathways, producing patterns of metabolite concentrations. Thus they provide a dynamic picture of the entire metabolite pattern in any given condition. The drawback of such a complex picture is that it can be confounded by compounds derived from ingested food or by metabolites of drugs and other foreign substances (xenobiotics).

The key process is the comparison of such patterns between the reference and affected populations using techniques such as mass spectrometry combined with gas chromatography (GCMS) or liquid chromatography (LC-MS). Individual metabolites can subsequently be identified using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR).

Validation of the potential markers requires studies on large cohorts of nonaffected and affected individuals. The required population sizes usually exceed the capabilities of a single study. Therefore meta-analysis (comparison of different studies) is extensively used. Such meta-analysis can be simply a comparison of several published studies, or can involve a combined analysis of group data from different studies, or – the most laborious but also most reliable method – it can constitute the analysis of individual participant data from different studies combined into a ‘new’ very large group.

Summary

The formed elements of blood are erythrocytes, leukocytes and platelets. They are suspended in an aqueous solution (plasma) and have several specialized functions such as transport of oxygen, destruction of external agents, and the clotting of blood. Plasma allowed to clot yields serum. Most biochemical tests are done on serum. To obtain plasma, blood must be taken into a test tube containing an anticoagulant.

The formed elements of blood are erythrocytes, leukocytes and platelets. They are suspended in an aqueous solution (plasma) and have several specialized functions such as transport of oxygen, destruction of external agents, and the clotting of blood. Plasma allowed to clot yields serum. Most biochemical tests are done on serum. To obtain plasma, blood must be taken into a test tube containing an anticoagulant.

Plasma contains many proteins broadly classified into albumin and globulins (predominantly immunoglobulins). Albumin functions as a determinant of the osmotic pressure and a major transport protein for trace metals, hormones, bilirubin, and free fatty acids.

Plasma contains many proteins broadly classified into albumin and globulins (predominantly immunoglobulins). Albumin functions as a determinant of the osmotic pressure and a major transport protein for trace metals, hormones, bilirubin, and free fatty acids.

Other binding proteins bind specific ligands, e.g. ceruloplasmin binds Cu2+ and thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG) binds thyroid hormones.

Other binding proteins bind specific ligands, e.g. ceruloplasmin binds Cu2+ and thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG) binds thyroid hormones.

Immunoglobulins participate in the defense against antigens that may enter or attempt to enter the body. They have a common structure: five classes of immunoglobulin exist and perform different protective functions.

Immunoglobulins participate in the defense against antigens that may enter or attempt to enter the body. They have a common structure: five classes of immunoglobulin exist and perform different protective functions.

Changes in the concentration of plasma proteins give important clinical information. A characteristic pattern with decreased albumin, transthyretin and transferrin and increased α1-antitrypsin, fibrinogen and C-reactive protein indicates the acute phase response.

Changes in the concentration of plasma proteins give important clinical information. A characteristic pattern with decreased albumin, transthyretin and transferrin and increased α1-antitrypsin, fibrinogen and C-reactive protein indicates the acute phase response.

Serum and urine protein electrophoresis is an important way of identifying the presence of monoclonal immunoglobulins.

Serum and urine protein electrophoresis is an important way of identifying the presence of monoclonal immunoglobulins.

Abu Aboud, O, Weiss, RH. New opportunities from the cancer metabolome. Clin Chem. 2013; 59:138–146.

Anderson, NL. The clinical plasma proteome: a survey of clinical assays for proteins in plasma and serum. Clin Chem. 2010; 56:177–185.

El-Youssef, M. Wilson's disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003; 78:1126–1136.

Gilstrap, LG, Wang, TJ. Biomarkers and cardiovascular risk assessment for primary prevention: an update. Clin Chem. 2012; 58:72–82.

Nature Outlook. Multiple myeloma. Nature. 2011; 480:833–858.

Pavlou, MP, Diamandis, EP, Blasutig, IM. The long journey of cancer biomarkers from the bench to the clinic. Clin Chem. 2013; 59:147–157.

Suhre, K, Shin, S-Y, Petersen, A-K, et al. Human metabolic individuality in biomedical and pharmaceutical research. Nature. 2011; 477:54–60.

Zimmermann, MA, Selzman, CH, Cothren, C. Diagnostic implications of C-reactive protein. Arch Surg. 2003; 138:220–224.

Biomarkers. www.niehs.nih.gov/health/topics/science/biomarkers/index.cfm.

National Cancer Institute, NCI NIH. NCI Dictionary of Cancer Term. www.cancer.gov/dictionary?cdrid=45618