Biosynthesis and Degradation of Amino Acids

Introduction

Amino acids are a source of energy from the diet and during fasting

In addition to their roles as building blocks for peptides and proteins, and as precursors of neurotransmitters and hormones, the carbon skeletons of some amino acids can be used to produce glucose through gluconeogenesis, thereby providing a metabolic fuel for tissues that require or prefer glucose; such amino acids are designated as glucogenic or glycogenic amino acids. The carbon skeletons of some amino acids can also produce the equivalent of acetyl-CoA or acetoacetate and are termed ketogenic, indicating that they can be metabolized to give immediate precursors of lipids or ketone bodies. In an individual consuming adequate amounts of protein, a significant quantity of amino acids may also be converted to carbohydrate (glycogen) or fat (triacylglycerol) for storage. Unlike carbohydrates and lipids, amino acids do not have a dedicated storage form equivalent to glycogen or fat.

When amino acids are metabolized, the resulting excess nitrogen must be excreted. Since the primary form in which the nitrogen is removed from amino acids is ammonia, and because free ammonia is quite toxic, humans and most higher animals rapidly convert the ammonia derived from amino acid catabolism to urea, which is neutral, less toxic, very soluble, and excreted in the urine. Thus the primary nitrogenous excretion product in humans is urea, produced by the urea cycle in liver. Animals that excrete urea are termed ureotelic. In an average individual, more than 80% of the excreted nitrogen is in the form of urea (25–30 g/24 h). Smaller amounts of nitrogen are also excreted in the form of uric acid, creatinine, and ammonium ion.

The carbon skeletons of many amino acids may be derived from metabolites in central pathways, allowing the biosynthesis of some, but not all, the amino acids in humans. Amino acids that can be synthesized in this way are therefore not required in the diet (nonessential amino acids), whereas amino acids having carbon skeletons that cannot be derived from normal human metabolism must be supplied in the diet (essential amino acids). For the biosynthesis of nonessential amino acids, amino groups must be added to the appropriate carbon skeletons. This generally occurs through the transamination of an α-keto acid corresponding to that specific amino acid.

Metabolism of dietary and endogenous proteins

Relationship to central metabolism

Muscle protein and adipose lipids are consumed to support gluconeogenesis during fasting and starvation

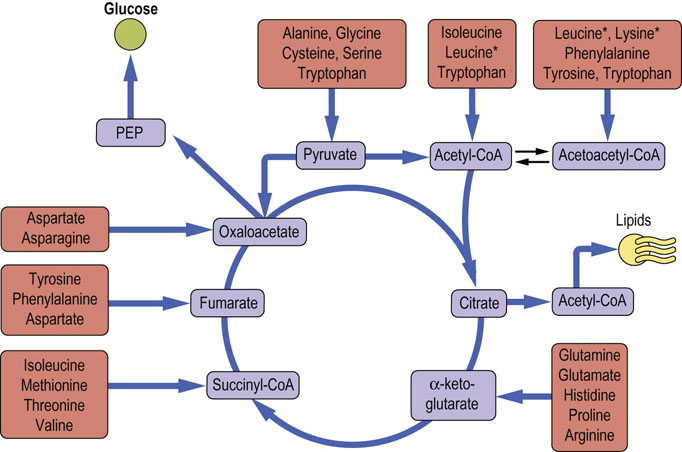

Although body proteins represent a significant proportion of potential energy reserves (Table 19.1), under normal circumstances they are not used for energy production. In an extended fast, however, muscle protein is degraded to amino acids for the synthesis of essential proteins, and to keto acids for gluconeogenesis to maintain blood glucose concentration as well to provide carbons for energy production. This accounts for the loss of muscle mass during fasting.

Table 19.1

Storage forms of energy in the body

Proteins represent a substantial energy reserve in the body.

*In a 70-kg individual.

(Adapted with permission from Cahill GF Jr, Clin Endocrinol Metab 1976;5:398.)

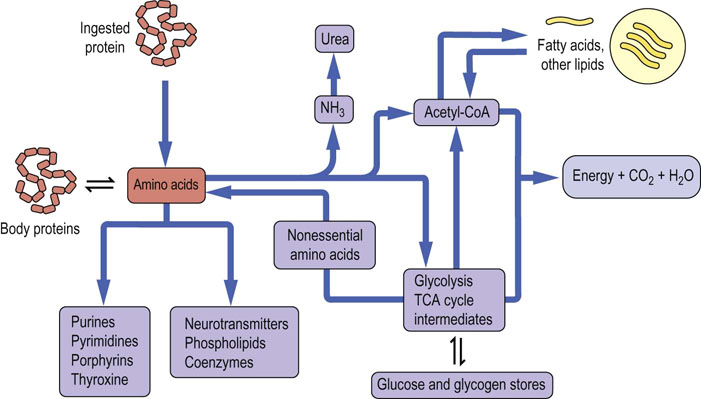

In addition to its role as an important source of carbon skeletons for oxidative metabolism and energy production, dietary protein must provide adequate amounts of those amino acids that we cannot make, to support normal protein synthesis. The relationships of body protein and dietary protein to central amino acid pools and to central metabolism are illustrated in Figure 19.1.

Fig. 19.1 Metabolic relationships among amino acids.

The pool of free amino acids is derived from the degradation and turnover of body proteins and from the diet. The amino acids are precursors of important biomolecules, including hormones, neurotransmitters and proteins, and also serve as a carbon source for central metabolism, including gluconeogenesis, lipogenesis and energy production.

Digestion and absorption of dietary protein

In order for dietary protein to contribute to either energy metabolism or pools of essential amino acids, the protein must be digested to the level of free amino acids or small peptides and absorbed across the gut. Digestion of protein begins in the stomach with the action of pepsin, a carboxyl protease that is active in the very low pH found in the gastric environment. Digestion continues as the stomach contents are emptied into the small intestine and mixed with pancreatic secretions. These pancreatic secretions are alkaline and contain the inactive precursors of several serine proteases including trypsin, chymotrypsin and elastase along with carboxypeptidases. The process is completed by enzymes in the small intestine (see Chapter 10). After any remaining di- and tripeptides are broken down in enterocytes, the free amino acids are transported to the portal vein and carried to the liver for energy metabolism or biosynthesis, or distributed to other tissues to meet similar needs.

Turnover of endogenous proteins

In addition to the ingestion, digestion and absorption of amino acids from dietary protein, all the proteins in the body have a half-life or life span and are routinely degraded to amino acids and replaced with newly synthesized protein. This process of protein turnover is carried out in the lysosome or by proteasomes. In the case of lysosomal digestion, protein turnover begins with engulfment of the protein or organelle in vesicles known as autophagosomes, by a process known as autophagy. The vesicles then fuse with lysosomes and the protein, lipid and glycans are degraded by lysosomal acid hydrolases. Cytosolic proteins are degraded primarily by proteasomes which are high-molecular-weight complexes containing multiple proteolytic activities. There are both ubiquitin-dependent (Chapter 34) and ubiquitin-independent pathways for degradation of cytosolic proteins.

Amino acid degradation

Amino acids destined for energy metabolism must be deaminated to yield the carbon skeleton

There are three mechanisms for removal of the amino group from amino acids.

Transamination – the transfer of the amino group to a suitable keto acid acceptor (Fig. 19.2).

Transamination – the transfer of the amino group to a suitable keto acid acceptor (Fig. 19.2).

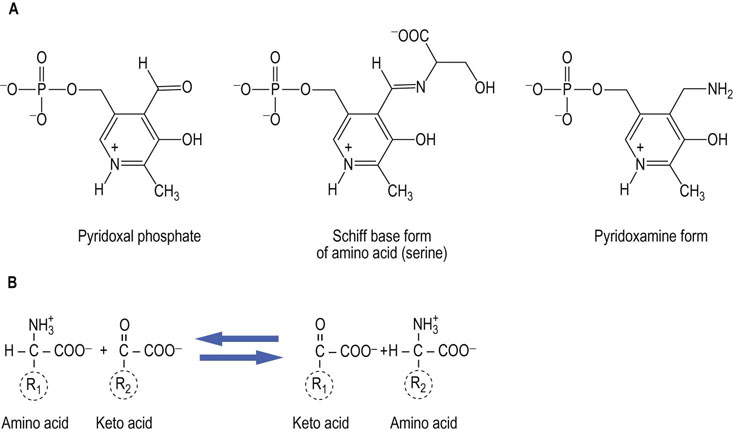

Fig. 19.2 The catalytic role of pyridoxal phosphate.

Aminotransferases or transaminases use pyridoxal phosphate as a cofactor. A pyridoxamine adduct acts as an intermediate in transfer of an amino group between an α-amino acid and an α-keto acid. (A) Structures of the components involved. The cofactor, pyridoxal phosphate, is used in a variety of enzyme-catalyzed reactions involving both amino and keto compounds, including transamination and decarboxylation reactions. (B) Transamination involves both a donor α-amino acid (R1), and an acceptor α-keto acid (R2). The products are an α-keto acid derived from the carbon skeleton of R1 and an α-amino acid from the carbon skeleton of R2.

Oxidative deamination – the oxidative removal of the amino group, resulting in keto acids and ammonia (see Fig. 19.3).

Oxidative deamination – the oxidative removal of the amino group, resulting in keto acids and ammonia (see Fig. 19.3).

Fig. 19.3 Deamination of amino acids.

The primary route for amino group removal is via transamination, but there are additional enzymes capable of removing the α-amino group. (A) L-amino acid oxidase produces ammonia and an α-keto acid directly, using flavin mononucleotide (FMN) as a cofactor. The reduced form of the flavin must be regenerated using molecular oxygen; this reaction is one of several that produce H2O2. The peroxide is decomposed by catalase. (B) A second means of deamination is possible only for hydroxyamino acids (serine and threonine), through a dehydratase mechanism; the Schiff base, imine intermediate hydrolyzes to form the keto acid and ammonia.

Removal of a molecule of water by a dehydratase – e.g. serine or threonine dehydratase; this reaction produces an unstable, imine intermediate that hydrolyzes spontaneously to yield an α-keto acid and ammonia (see Fig. 19.3).

Removal of a molecule of water by a dehydratase – e.g. serine or threonine dehydratase; this reaction produces an unstable, imine intermediate that hydrolyzes spontaneously to yield an α-keto acid and ammonia (see Fig. 19.3).

The principal mechanism for removal of amino groups from the common amino acids is via transamination, or the transfer of amino groups from the amino acid to a suitable α-keto acid acceptor, most commonly to α-ketoglutarate or oxaloacetate, forming glutamate and aspartate, respectively. Several enzymes, called aminotransferases (or transaminases), are capable of removing the amino group from most amino acids and producing the corresponding α-keto acid. Aminotransferase enzymes use pyridoxal phosphate, a cofactor derived from the vitamin B6 (pyridoxine), as a key component in their catalytic mechanism; pyridoxamine is an intermediate in the reaction. The structures of the various forms of vitamin B6 and the net reaction catalyzed by aminotransferases are shown in Figure 19.2.

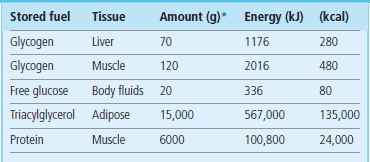

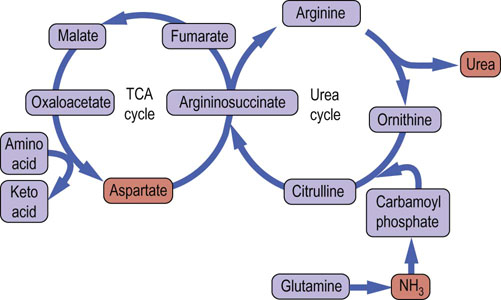

Nitrogen atoms are incorporated into urea from two sources, glutamate and aspartate

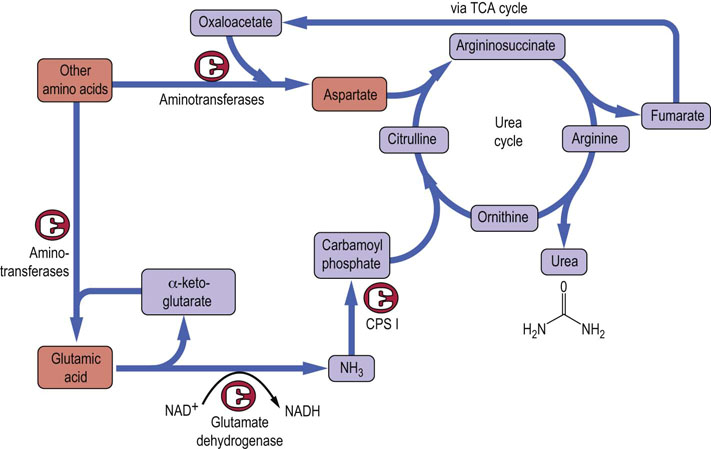

The transfer of an amino group from one keto acid carbon skeleton to another may seem to be unproductive and not useful in itself; however, when one considers the nature of the primary keto acid acceptors that participate in these reactions (α-ketoglutarate and oxaloacetate) and their products (glutamate and aspartate), the logic of this metabolism becomes clear. The two nitrogen atoms in urea are derived exclusively from these two amino acids (Fig. 19.4), thereby linking amino acid catabolism to energy metabolism. Ammonia, which is produced primarily from glutamate via the glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) reaction (Fig. 19.5B), enters the urea cycle as carbamoyl phosphate. The second nitrogen is contributed to urea by aspartic acid. Fumarate is formed in this process and may be recycled through the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle to oxaloacetate, which can accept another amino group and re-enter the urea cycle, or the fumarate may be used for energy metabolism or gluconeogenesis. Thus the funneling of amino groups from other amino acids into glutamate and aspartate provides the nitrogen for urea synthesis in a form appropriate for the urea cycle (Fig. 19.4). The other pathways that lead to the release of amino groups from some amino acids through the action of amino acid oxidase or dehydratases (Fig. 19.3) make relatively minor contributions to the flow of amino groups from amino acids to urea.

Fig. 19.4 Sources of nitrogen atoms in the urea cycle.

Nitrogen enters the urea cycle from most amino acids via transfer of the α-amino group to either oxaloacetate or α-ketoglutarate, to form aspartate or glutamate, respectively. Glutamate releases ammonia in the liver through the action of GDH (Fig. 19.5). The ammonia is incorporated into carbamoyl phosphate, and the aspartate combines with citrulline to provide the second nitrogen for urea synthesis. Oxaloacetate and α-ketoglutarate can be repeatedly recycled to channel nitrogen into this pathway. CPS I, carbamoyl phosphate synthetase-I.

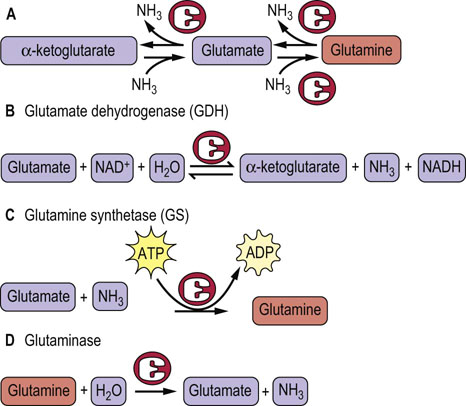

Fig. 19.5 Relationships between glutamate, glutamine and α-ketoglutarate.

The several forms of the carbon skeleton of glutamic acid have key roles in the metabolism of amino groups. (A) Three forms of the same carbon skeleton. (B) The glutamine dehydrogenase reaction is a reversible reaction that can produce glutamate from α-ketoglutarate or convert glutamate to α-ketoglutarate and ammonia. The latter reaction is important in the synthesis of urea because amino groups are fed to α-ketoglutarate via transamination from other amino acids. (C) Glutamine synthetase catalyzes an energy-requiring reaction with a key role in transport of amino groups from one tissue to another; it also provides a buffer against high concentrations of free ammonia in tissues. (D) The second half of the glutamine transport system for nitrogen is the enzyme glutaminase, which hydrolyzes glutamine to glutamate and ammonia. This reaction is important in the kidney for management of proton transport and pH control.

The central role of glutamine

Ammonia is detoxified by incorporation into glutamine, then eventually into urea

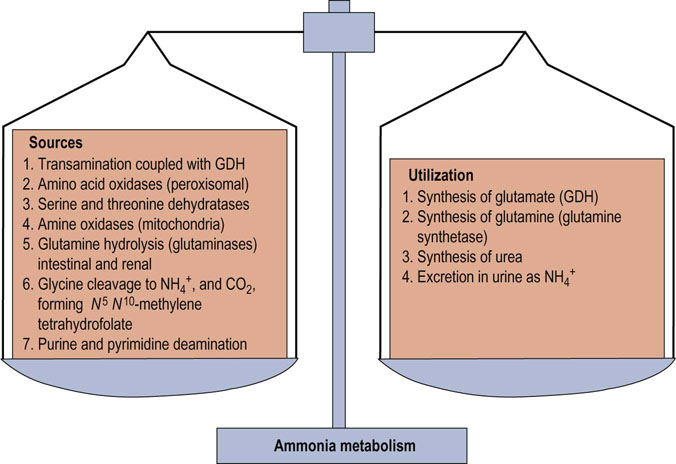

In addition to the role of glutamate as a carrier of amino groups to GDH, glutamate serves as a precursor of glutamine, a process that consumes a molecule of ammonia. This is important because glutamine, along with alanine, is a key transporter of amino groups between various tissues and the liver, and is present in greater concentrations than most other amino acids in blood. The three forms of the same carbon skeleton, α-ketoglutarate, glutamate, and glutamine, are interconverted via aminotransferases, glutamine synthetase, glutaminase, and GDH (see Fig. 19.5). Thus glutamine can serve as a buffer for ammonia utilization, as a source of ammonia, and as a carrier of amino groups. Because ammonia is quite toxic, a balance must be maintained between its production and utilization. A summary of the sources and pathways that use or produce ammonia is shown in Figure 19.6. It should be noted that the GDH reaction is reversible under physiologic conditions if amino groups are required for amino acid and other biosynthetic processes.

Fig. 19.6 Balance in ammonia metabolism.

The balance between production and utilization of free ammonia is critical for maintenance of health. This figure summarizes the sources and pathways that use ammonia. Although most of these reactions occur in many tissues, synthesis of urea and the urea cycle are restricted to the liver. Glutamine and alanine function as the primary transporters of nitrogen from peripheral tissues to the liver.

The urea cycle and its relationship to central metabolism

The urea cycle is an hepatic pathway for disposal of excess nitrogen

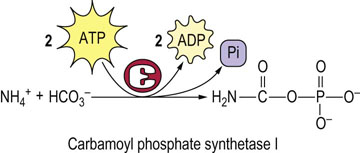

Urea is the principal nitrogenous excretion product in humans (Table 19.2). The urea cycle (see Fig. 19.4) was the first metabolic cycle to be well defined; its description preceded that of the TCA cycle. The start of the urea cycle may be considered the synthesis of carbamoyl phosphate from an ammonium ion, derived primarily from glutamate via GDH (Fig. 19.5), and bicarbonate from liver mitochondria. This reaction requires two molecules of ATP and is catalyzed by the enzyme carbamoyl phosphate synthetase I (CPS I) (Fig. 19.7), which is found at high concentration in the mitochondrial matrix.

Table 19.2

| Urinary metabolite | g excreted/24 h* | % of total |

| Urea | 30 | 86 |

| Ammonium ion | 0.7 | 2.8 |

| Creatinine | 1.0–1.8 | 4–5 |

| Uric acid | 0.5–1.0 | 2–3 |

Fig. 19.7 Synthesis of carbamoyl phosphate.

The first nitrogen, derived from ammonia, enters the urea cycle as carbamoyl phosphate, synthesized by carbamoyl phosphate synthetase I in the liver.

The mitochondrial isozyme, CPS I, is unusual in that it requires N-acetylglutamate as a cofactor. It is one of two carbamoyl phosphate synthetase enzymes that have key roles in metabolism. The second, CPS II, is found in the cytosol, does not require N-acetylglutamate, and is involved in pyrimidine biosynthesis (Chapter 31).

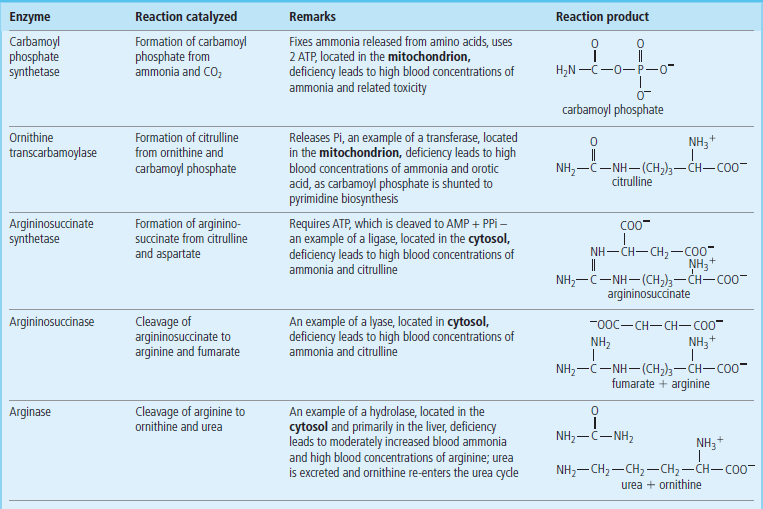

Ornithine transcarbamoylase catalyzes the condensation of carbamoyl phosphate with the amino acid ornithine, to form citrulline: see Figure 19.4 for pathway and Table 19.3 for structures. In turn, the citrulline is condensed with aspartate to form argininosuccinate. This step is catalyzed by argininosuccinate synthetase and requires ATP; the reaction cleaves the ATP to adenosine monophosphate (AMP) and inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi) (2 ATP equivalents). The formation of argininosuccinate incorporates the second nitrogen atom destined for urea. Argininosuccinate is cleaved by argininosuccinase to arginine and fumarate, and the arginine is then cleaved by arginase to yield urea and ornithine. The ornithine and fumarate can re-enter the urea cycle, while the urea diffuses into the blood, is transported to the kidney and excreted in urine. The net process of ureogenesis is summarized in Table 19.4.

The urea cycle is split between the mitochondrial matrix and the cytosol

The first two steps in the urea cycle occur in the mitochondrion. The citrulline which is formed in the mitochondrion then moves into the cytosol by a specific passive transport system. The cycle is completed in the cytosol with the release of urea from arginine and the regeneration of ornithine. Ornithine is transported back across the mitochondrial membrane to continue the cycle. Carbons from fumarate, released in the argininosuccinase step, may also re-enter the mitochondrion and be recycled by enzymes in the TCA cycle to oxaloacetate and ultimately to aspartate (Fig. 19.8), thus completing the second part of the urea cycle. Urea synthesis occurs virtually exclusively in the liver and the role of the enzyme, arginase, in other tissues is probably related more closely to ornithine requirements for polyamine synthesis than to the production of urea.

Fig. 19.8 The tricarboxylic acid and urea cycles.

Analysis of the urea cycle reveals that it is really two cycles, with the carbon flow split between the primary urea synthetic process and the recycling of fumarate to aspartate; the latter cycle occurs in the mitochondrion and involves parts of the TCA cycle.

Regulation of the urea cycle

N-acetylglutamate, and indirectly arginine, is an essential allosteric regulator of the urea cycle

The urea cycle is regulated in part by control of the concentration of N-acetylglutamate, the essential allosteric activator of CPS I. Arginine is an allosteric activator of N-acetylglutamate synthase and also a source of ornithine (via arginase) for the urea cycle. Concentrations of urea cycle enzymes also increase or decrease in response to a high- or low-protein diet, and urea synthesis and excretion are decreased and NH4+ excretion is increased during acidosis as a mechanism to excrete protons into the urine. Lastly, it should be noted that during a fast, protein is broken down to free amino acids which are used for gluconeogenesis. The increase in protein degradation during fasting results in increased urea synthesis and excretion, a mechanism to dispose of the released nitrogen.

Defects in any of the enzymes of the urea cycle have serious consequences. Infants born with defects in any of the first four enzymes in this pathway may appear normal at birth, but rapidly become lethargic and hypothermic, and may have difficulty breathing. Blood concentrations of ammonia increase quickly, followed by cerebral edema. The symptoms are most severe when early steps in the cycle are affected. However, a defect in any of the enzymes in this pathway is a serious issue and may cause hyperammonemia and lead rapidly to CNS edema, coma and death. Ornithine transcarbamoylase is the most common of these urea cycle defects and shows an X-linked inheritance pattern. The remainder of the known defects associated with the urea cycle are autosomal recessive. A deficiency of arginase, the last enzyme in the cycle, produces less severe symptoms but is nevertheless characterized by increased concentrations of blood arginine and at least a moderate increase in blood ammonia. In individuals with high blood concentrations of ammonia, hemodialysis must be used, often followed by intravenous administration of sodium benzoate and phenyllactate. These compounds are conjugated with glycine and glutamine, respectively, to form water-soluble adducts, trapping the ammonia in a nontoxic form that can be excreted in the urine.

The concept of nitrogen balance

A careful balance is maintained between nitrogen ingestion and secretion

Because there is no significant storage form of nitrogen or amino compounds in humans, nitrogen metabolism is quite dynamic. In an average, healthy diet, the protein content exceeds the amount required to supply essential and nonessential amino acids for protein synthesis, and the amount of nitrogen excreted is approximately equal to that taken in. Such a healthy adult would be said to be ‘in neutral nitrogen balance’. When there is a need to increase protein synthesis, such as in recovering from trauma or in a rapidly growing child, the amount of nitrogen excreted is less than that consumed in the diet, and the individual would be in ‘positive nitrogen balance’. The converse is true in protein malnutrition: because of the need to synthesize essential body proteins, other proteins, particularly muscle proteins, are degraded and more nitrogen is lost than is consumed in the diet. Such an individual would be said to be in ‘negative nitrogen balance’. Fasting, starvation and poorly controlled diabetes are also characterized by negative nitrogen balance, as body protein is degraded to amino acids and their carbon skeletons are used for gluconeogenesis. The concept of nitrogen balance is clinically important because it reminds us of the continuous turnover of amino acids and proteins in the body (see Chapter 22).

Metabolism of the carbon skeletons of amino acids

Metabolism of amino acids interfaces with carbohydrate and lipid metabolism

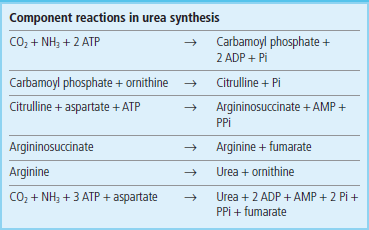

When one examines the metabolism of the carbon skeletons of the 20 common amino acids, there is an obvious interface with carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. Virtually all the carbons can be converted into intermediates in the glycolytic pathway, the TCA cycle or lipid metabolism. The first step in this process is the transfer of an α-amino group by transamination to α-ketoglutarate or oxaloacetate, providing glutamate and aspartate, the sources for the nitrogen atoms of the urea cycle (Fig. 19.9). The single exception to this is lysine, which does not undergo transamination. Although the details of pathways for the various amino acids vary, the general rule is that there is loss of the amino group, followed by either direct metabolism in a central pathway (glycolysis, the TCA cycle or ketone body metabolism), or one or more intermediate conversions to yield a metabolite in one of the central pathways. Examples of amino acids that follow the former scheme include alanine, glutamate and aspartate, which yield pyruvate, α-ketoglutarate and oxaloacetate, respectively. The branched-chain amino acids, leucine, valine and isoleucine, and the aromatic amino acids, tyrosine, tryptophan and phenylalanine, are examples of the latter, more complex pathways.

Amino acids may be either glucogenic or ketogenic

Depending on the point at which the carbons from an amino acid enter central metabolism, that amino acid may be considered to be either glucogenic or ketogenic, i.e. possessing the ability to increase the concentrations of either glucose or ketone bodies, respectively, when fed to an animal. Those amino acids that feed carbons into the TCA cycle at the level of α-ketoglutarate, succinyl-CoA, fumarate or oxaloacetate, and those that produce pyruvate can all give rise to the net synthesis of glucose via gluconeogenesis and are hence designated glucogenic. Those amino acids that feed carbons into central metabolism at the level of acetyl-CoA or acetoacetyl-CoA are considered ketogenic. Because of the nature of the TCA cycle, no net flow of carbons can occur between acetate or its equivalent (e.g. butyrate or acetoacetate) from ketogenic amino acids to glucose via gluconeogenesis (see Chapter 13).

Several amino acids, primarily those with more complex or aromatic structures, can yield both glucogenic and ketogenic fragments (see Fig. 19.9). Only the amino acids leucine and lysine are regarded as being exclusively ketogenic and, because of its complex metabolism and lack of ability to undergo transamination, some authors do not consider lysine to be exclusively ketogenic. These classifications may be summarized as follows:

Glucogenic amino acids: alanine, arginine, asparagine, aspartic acid, cysteine, cystine, glutamine, glutamic acid, glycine, histidine, methionine, proline, serine, valine.

Glucogenic amino acids: alanine, arginine, asparagine, aspartic acid, cysteine, cystine, glutamine, glutamic acid, glycine, histidine, methionine, proline, serine, valine.

Ketogenic amino acids: leucine, lysine.

Ketogenic amino acids: leucine, lysine.

Both glucogenic and ketogenic amino acids: isoleucine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, tyrosine.

Both glucogenic and ketogenic amino acids: isoleucine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, tyrosine.

Metabolism of the carbon skeletons of selected amino acids

The 20 amino acids are metabolized by complex pathways to various intermediates in carbohydrate and lipid metabolism

Alanine, aspartate and glutamate are examples of glucogenic amino acids. In each case, through either transamination or oxidative deamination, the resulting α-keto acid is a direct precursor of oxaloacetate via central metabolic pathways. Oxaloacetate can then be converted to PEP, and subsequently to glucose via gluconeogenesis. Other glucogenic amino acids reach the TCA cycle or related metabolic intermediates through several steps, after the removal of the amino group (Fig. 19.10).

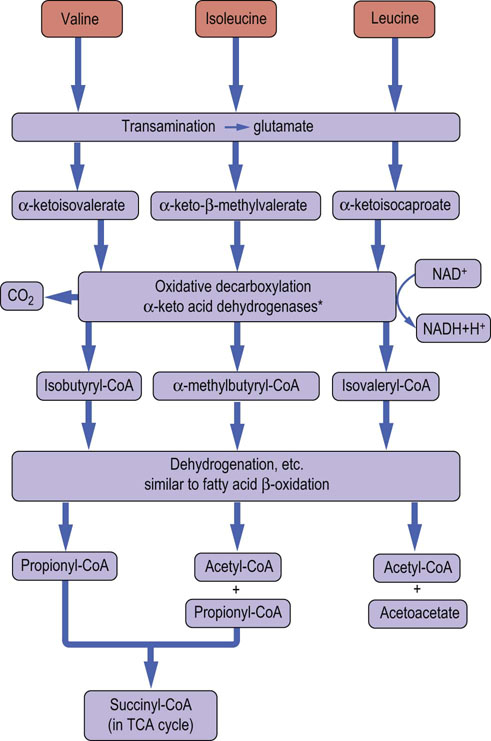

Fig. 19.10 Degradation of branched-chain amino acids.

Metabolism of the branched-chain amino acids produces acetyl-CoA and acetoacetate. In the case of valine and isoleucine, propionyl-CoA is produced and metabolized, in two steps, to succinyl-CoA (Fig. 15.5). *The branched-chain amino acid dehydrogenases are structurally related to pyruvate dehydrogenase and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase, and use the cofactors thiamine pyrophosphate, lipoic acid, flavin adenine dinucleotide, NAD+ and CoA.

Leucine is an example of a ketogenic amino acid. Its catabolism begins with transamination to produce 2-keto-isocaproate. The metabolism of 2-ketoisocaproate requires oxidative decarboxylation by a dehydrogenase complex to produce isovaleryl-CoA. Further metabolism of isovaleryl-CoA leads to formation of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA, a precursor of both acetyl-CoA and the ketone bodies. The metabolism of leucine and the other branched-chain amino acids is summarized in Figure 19.10. Propionyl-CoA derived from either amino acid degradation or odd-chain fatty acid metabolism is converted to succinyl-CoA (see Fig. 15.5).

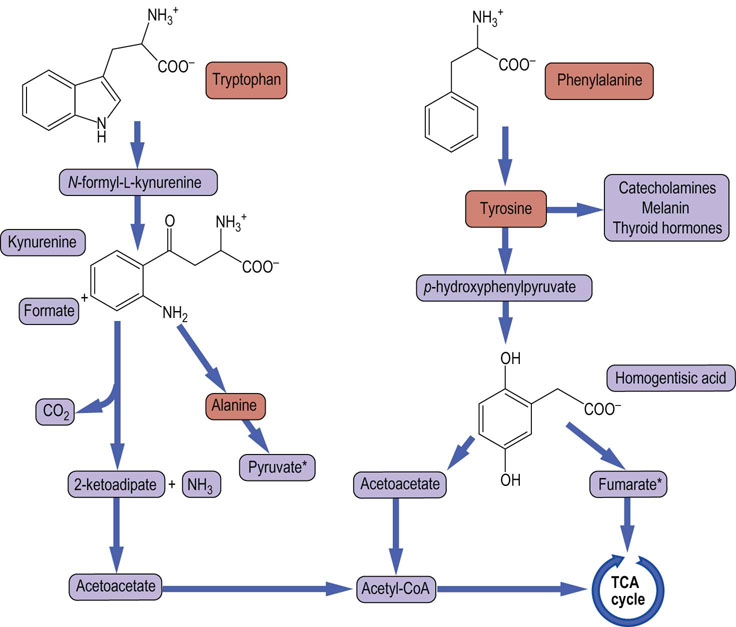

Tryptophan is a good example of an amino acid that yields both glucogenic and ketogenic precursors. After cleavage of its heterocyclic ring and a complex set of reactions, the core of the amino acid structure is released as alanine (a glucogenic precursor), while the balance of the carbons are ultimately converted to glutaryl-CoA (a ketogenic precursor). Figure 19.11 summarizes key points in the catabolism of the aromatic amino acids.

Fig. 19.11 Catabolism of aromatic amino acids.

This figure summarizes the catabolism of the aromatic amino acids, illustrating the pathways that lead to ketogenic and glucogenic precursors derived from both tyrosine and tryptophan. *Both pyruvate and fumarate can lead to net glucose synthesis. They constitute the gluconeogenic portions of the metabolism of these amino acids.

Biosynthesis of amino acids

Evolution has left our species without the ability to synthesize almost half the amino acids required for synthesis of proteins and other biomolecules

Humans use 20 amino acids to build peptides and proteins that are essential for the many functions of their cells. Biosynthesis of the amino acids involves synthesis of the carbon skeletons for the corresponding α-keto acids, followed by addition of the amino group via transamination. However, humans are capable of carrying out the biosynthesis of the carbon skeletons of only about half of those α-keto acids. Amino acids that we cannot synthesize are termed essential amino acids, and are required in the diet. While almost all the amino acids can be classified as clearly essential or nonessential, a few require further qualification. For example, although cysteine is not generally considered an essential amino acid because it can be derived from the nonessential amino acid serine, its sulfur must come from the required or essential amino acid methionine. Similarly, the amino acid tyrosine is not required in the diet, but must be derived from the essential amino acid phenylalanine. This relationship between phenylalanine and tyrosine will be discussed further in considering the inherited disease phenylketonuria (PKU). Tables 19.5 and 19.6 list the nonessential and essential amino acids, and the source of the carbon skeleton in the case of those not required in the diet.

Table 19.5

Origins of nonessential amino acids

| Amino acid | Source in metabolism, etc. |

| Alanine | From pyruvate via transamination |

| Aspartic acid, asparagine, arginine, glutamic acid, glutamine, proline | From intermediates in the citric acid cycle |

| Serine | From 3-phosphoglycerate (glycolysis) |

| Glycine | From serine |

| Cysteine* | From serine; requires sulfur derived from methionine |

| Tyrosine* | Derived from phenylalanine via hydroxylation |

*These are examples of nonessential amino acids that depend on adequate amounts of an essential amino acid.

Table 19.6

| Mnemonic | Amino acid* | Notes or comments |

| P | Phenylalanine | Required in the diet also as a precursor of tyrosine |

| V | Valine | One of three branched-chain amino acids |

| T | Threonine | Metabolized like a branched-chain amino acid |

| T | Tryptophan | Its heterocyclic indole side chain cannot be synthesized in humans |

| I | Isoleucine | One of three branched-chain amino acids |

| M | Methionine | Provides the sulfur for cysteine and participates as a methyl donor in metabolism; the homocysteine is recycled |

| H | Histidine | Its heterocyclic imidazole side chain cannot be synthesized in humans |

| A | Arginine | Whereas arginine can be derived from ornithine in the urea cycle in amounts sufficient to support the needs of adults, growing animals require it in the diet |

| L | Leucine | A pure ketogenic amino acid |

| L | Lysine | Does not undergo direct transamination |

*The mnemonic PVT TIM HALL is useful for recalling the names of the essential amino acids.

Amino acids are precursors of many essential compounds

In addition to their role as the building blocks for peptides and proteins, amino acids are essential precursors of a number of neurotransmitters, hormones, inflammatory mediators, and carrier and effector molecules (Table 19.7). Examples of this include histidine, which serves as the precursor of histamine (the mediator of inflammation released by mast cells and lymphocytes), glutamate, glycine and aspartate, which serve directly as a neurotransmitters. Additional examples include gamma amino butyric acid (GABA), which is derived from glutamate, and tyrosine, which is derived from phenylalanine. Tyrosine is then the precursor of the neurotransmitters 1,3-dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA), dopamine, epinephrine, the thyroid hormones triiodothyronine and thyroxine, and melanin.

Table 19.7

Examples of amino acids as effector molecules or precursors

| Amino acid | Effector molecule or prosthetic group |

| Arginine | Immediate precursor of urea, precursor of nitric oxide |

| Aspartate | An excitatory neurotransmitter |

| Glycine | An inhibitory neurotransmitter; precursor of heme |

| Glutamate | Excitatory neurotransmitter; precursor of γ-amino butyric (GABA), an inhibitory neurotransmitter |

| Histidine | Precursor of histamine, a mediator of inflammation and a neurotransmitter |

| Tryptophan | Precursor of serotonin, a potent smooth muscle contraction stimulator; precursor of melatonin, a regulator of circadian rhythm |

| Tyrosine | Precursor of the hormones and neurotransmitters catecholamines, dopamine, epinephrine and norepinephrine, thyroxine |

Inherited diseases of amino acid metabolism

In addition to deficiencies in the urea cycle, defects in the metabolism of the carbon skeletons of various amino acids were among the first disease states to be associated with simple inheritance patterns. These observations gave rise to the concept of the genetic basis of inherited metabolic disease states, also known as inborn errors of metabolism. Garrod considered a number of disease states that appeared to be inherited in a Mendelian pattern, and proposed a correlation between these abnormalities and specific genes, in which the disease state could be either dominant or recessive. Dozens of inborn errors of amino acid metabolism have now been described, and the molecular defect has been described for many of them. Three classic inborn errors of metabolism will be discussed in some detail here.

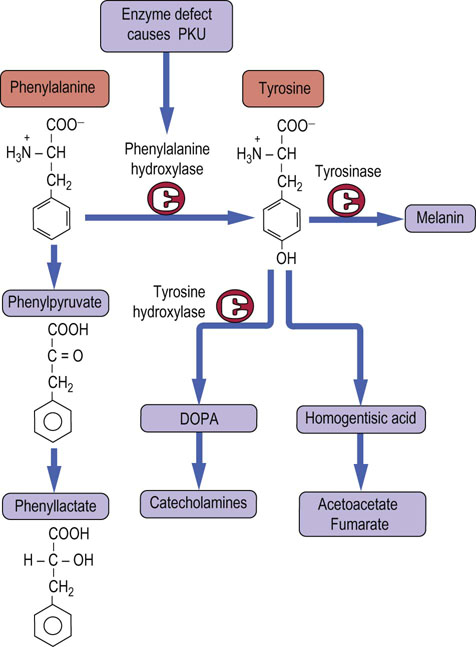

Phenylketonuria (PKU)

The common form of PKU results from a deficiency of the enzyme phenylalanine hydroxylase. The hydroxylation of phenylalanine is a required step in both the normal degradation of the carbon skeleton of this amino acid and the synthesis of tyrosine (Fig. 19.12). When untreated, this metabolic defect leads to excessive urinary excretion of phenylpyruvate and phenyllactate, and severe mental retardation. In addition, individuals with PKU tend to have very light skin pigmentation, unusual gait, stance, and sitting posture, and a high frequency of epilepsy. In the USA, this autosomal recessive defect occurs in about 1 in 30,000 live births. Because of its frequency, and the ability to prevent the most serious consequences of the defect by a low-phenylalanine diet, newborns in most developed countries are routinely tested for blood concentrations of phenylalanine. Fortunately, with early detection and the use of a diet restricted in phenylalanine but supplemented with tyrosine, most of the mental retardation can be avoided. Mothers who are homozygous for this defect have a very high probability of bearing children with congenital defects and mental retardation unless their blood phenylalanine concentrations can be controlled by diet. The developing fetus is very sensitive to the toxic effects of high concentrations of phenylalanine and related phenylketones. Not all hyperphenylalaninemias are caused by a defect in phenylalanine hydroxylase. In some cases, there is a defect in biosynthesis or reduction of a required tetrahydrobiopterin cofactor.

Fig. 19.12 Degradation of phenylalanine.

In order to enter normal metabolism, phenylalanine must be hydroxylated by the enzyme phenylalanine hydroxylase. A defect in this enzyme leads to phenyl-ketonuria (PKU). Tyrosine is a precursor of acetyl-CoA and fumarate, catecholamine hormones, the neurotransmitter dopamine, and the pigment melanin. DOPA, dihydroxyphenylalanine.

Alkaptonuria (black urine disease)

A second inherited defect in the phenylalanine–tyrosine pathway involves a deficiency in the enzyme that catalyzes the oxidation of homogentisic acid, an intermediate in catabolism of tyrosine and phenylalanine. In this condition, which occurs in 1 in 1,000,000 live births, homogentisic acid accumulates and is excreted in urine. This compound oxidizes to alkaptone on standing or on treatment with alkali, and gives the urine a dark color. Individuals with alkaptonuria ultimately suffer from deposition of dark (ochre-colored) pigment in cartilage tissue, with subsequent tissue damage, including severe arthritis; the onset of these symptoms is generally in the third or fourth decade of life. This autosomal recessive disease was the first of several that Garrod considered in proposing his initial hypothesis for inborn errors of metabolism. Although alkaptonuria is relatively benign compared with PKU, little is available in the way of treatment, other than symptomatic relief.

Maple syrup urine disease (MSUD)

The normal metabolism of the branched-chain amino acids leucine, isoleucine and valine involves loss of the α-amino group, followed by oxidative decarboxylation of the resulting α-keto acid. This decarboxylation step is catalyzed by branched-chain keto acid decarboxylase, a multienzyme complex associated with the inner membrane of the mitochondrion. In approximately 1 in 300,000 live births, a defect in this enzyme leads to accumulation of the keto acids corresponding to these branched-chain amino acids in the blood, and then to branched-chain ketoaciduria. When untreated or unmanaged, this condition may lead to both physical and mental retardation of the newborn and a distinct maple syrup odor of the urine. This defect can be partially managed with a low-protein or modified diet, but not in all cases. In some instances, supplementation with high doses of thiamine pyrophosphate, a cofactor for this enzyme complex, has been helpful.

Summary

In this chapter, we have seen that the metabolism of amino acids is integrally related to the mainstream of metabolism.

The catabolism of amino acids generally begins with the removal of the α-amino group, which is transferred to α-ketoglutarate and oxaloacetate, and ultimately excreted in the form of urea.

The catabolism of amino acids generally begins with the removal of the α-amino group, which is transferred to α-ketoglutarate and oxaloacetate, and ultimately excreted in the form of urea.

The resulting carbon skeletons are converted to intermediates that enter central metabolism at various points.

The resulting carbon skeletons are converted to intermediates that enter central metabolism at various points.

Because carbon skeletons corresponding to the various amino acids can be derived from or fed into the glycolytic pathway, the TCA cycle, fatty acid biosynthesis and gluconeogenesis, amino acid metabolism should not be considered as an isolated pathway.

Because carbon skeletons corresponding to the various amino acids can be derived from or fed into the glycolytic pathway, the TCA cycle, fatty acid biosynthesis and gluconeogenesis, amino acid metabolism should not be considered as an isolated pathway.

Although amino acids are not stored like glucose (glycogen) or fatty acids (triglycerides), they have an important and dynamic role, not only in providing the building blocks for the synthesis and turnover of protein but also in normal energy metabolism, providing a carbon source for gluconeogenesis when needed and an energy source of last resort in starvation.

Although amino acids are not stored like glucose (glycogen) or fatty acids (triglycerides), they have an important and dynamic role, not only in providing the building blocks for the synthesis and turnover of protein but also in normal energy metabolism, providing a carbon source for gluconeogenesis when needed and an energy source of last resort in starvation.

Amino acids provide precursors for the biosynthesis of a variety of small signaling molecules, including hormones and neurotransmitters.

Amino acids provide precursors for the biosynthesis of a variety of small signaling molecules, including hormones and neurotransmitters.

The severe consequences of inherited diseases such as phenylketonuria and maple syrup urine disease illustrate the effects of abnormal amino acid metabolism.

The severe consequences of inherited diseases such as phenylketonuria and maple syrup urine disease illustrate the effects of abnormal amino acid metabolism.

Dietzen, DJ, Rinaldo, P, Whitley, RJ, et al. National academy of clinical biochemistry laboratory medicine practice guidelines: follow-up testing for metabolic disease identified by expanded newborn screening using tandem mass spectrometry; executive summary. Clin Chem. 2009; 55:1615–1626.

Gropman, AL, Summar, M, Leonard, JV. Neurological implications of urea cycle disorders. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2007; 30:865–879.

Kuhara, T. Noninvasive human metabolome analysis for differential diagnosis of inborn errors of metabolism. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2007; 855:42–50.

Mitchell, JJ, Trakadis, YJ, Scriver, CR. Phenylalanine hydroxylase deficiency. Genet Med. 2011; 13:697–707.

Morris, SM, Jr. Regulation of enzymes of the urea cycle and arginine metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr. 2002; 22:87–105.

Morris, SM, Jr. Arginine: beyond protein. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006; 83(suppl):508S–512S.

Lindemann, B, Ogiwara, Y, Ninomiya, Y. The discovery of Umami. Chem Senses. 2002; 27:843–844.

Ogier de Baulny, H, Saudubray, JM. Branched-chain organic acidurias. Semin Neonatal. 2002; 7:65–74.

Saudubray, JM, Nassogne, MC, de Lonlay, P, et al. Clinical approach to inherited metabolic disorders in neonates: an overview. Semin Neonatal. 2002; 7:3–15.

Singh, RH. Nutritional management of patients with urea cycle disorders. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2007; 30:880–887.

Summar, ML, Dobbelaere, D, Brusilow, S, et al. Diagnosis, symptoms, frequency and mortality of 260 patients with urea cycle disorders from a 21-year, multicentre study of acute hyperammonaemic episodes. Acta Paediatr. 2008; 97:1420–1425.

Wilcken, B. Screening for disease in the newborn: the evidence base for blood-spot screening. Pathology. 2012; 44:73–79.

Society for the Study of Inborn Errors of Metabolism (SSIEM) www.ssiem.org

www.uptodate.com/contents/urea-cycle-disorders-clinical-features-and-diagnosis

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1217/

Nitrogen metabolism. http://themedicalbiochemistrypage.org/nitrogen-metabolism.html.

Maple syrup urine disease. www.msud-support.org/overview.htm.

Parkinson's disease. www.enotes.com/parkinsons-disease-reference/parkinsons-disease-172267.

Phenylketonuria. www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/phenylketonuria.html.