32 ALTERATIONS OF THE REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEMS ACROSS THE LIFE SPAN

INTRODUCTION

Alterations of the reproductive systems span a wide range of concerns, from delayed sexual development and suboptimal sexual performance to structural and functional abnormalities. Many common reproductive disorders carry potentially serious physiological and psychological consequences. For example, sexual dysfunction such as impotence can dramatically affect self-confidence, relationships and overall quality of life. Conversely, organic and psychosocial problems, such as alcoholism, depression, chronic illness and medications, can affect ovulation and menstruation, sexual performance and fertility. In addition, these alterations may be risk factors for the development of some types of reproductive tract cancers. Unfortunately, cancers of the reproductive system in both sexes often cause considerable alteration to homeostasis and are potentially life-threatening. In Australia and New Zealand, breast cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer deaths in women and affects many women at a young age, and prostate cancer is one of the most common cancers in men. Therefore, a thorough understanding of the pathogenesis of these cancers is fundamental when caring for the individuals affected by them.

In this chapter we consider problems in both male and female reproductive structure and function. We briefly explore the likely causes of these problems and outline some of the symptoms and treatments. The reproductive systems and sexual function are often taboo subjects outside of the healthcare profession and this in itself is a major issue when dealing with associated problems. Many people find it difficult to talk about reproductive problems with their health professional — let alone their partner. Diagnosis and treatment of reproductive system disorders are often complicated by the stigma associated with the reproductive organs and by emotions related to reproductive health. Treatment and/or diagnosis may be delayed because of embarrassment, guilt, fear or denial.

CLASSIFICATION OF REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM ALTERATIONS

Alterations of the reproductive systems that are most commonly seen are broadly the result of one of three different initial causes that display similar symptoms. The most common causes of sexual dysfunction are: (1) growths, (2) problems associated with the endocrine system, and (3) structural and functional alterations of the reproductive system itself.

Growths

Growths within different parts of the reproductive system can be benign, pre-cancerous or cancerous. The growths themselves can be the problem (particularly if they are cancerous) or the effects of the growths can be the problem (if, for example, the growths impinge on another organ). Some growths lead to overproduction of hormones, resulting in a more varied set of symptoms in other parts of the reproductive system.

The endocrine system

Problems associated with the endocrine system can be present in utero and thus lead to abnormal structural development. For example, during development a genetically male fetus (XY) can fail to produce testosterone for a variety of reasons — some genetic, some environmental (see Chapter 37). This lack of testosterone during early fetal development can lead to partially functional female and, in some cases, male genitalia. Although this is an endocrine (or hormonal) dysfunction it leads to poor reproductive development in utero and to physical and psychological problems later in life.

In other cases, endocrine function may be normal during development in utero but then starts too early or too late during adolescence, leading to precocious (early) puberty or delayed puberty. At first, precocious puberty may seem to be less of a health issue and more of a psychosocial issue, but it can be an indication of hypothalamic dysfunction or tumour growth.1 It can also result in a reduced stature as the growth of bones ceases prematurely.2 In addition, precocious puberty has been associated with mental health problems in middle adolescence.3

During adulthood, endocrine dysfunction can result in the failure of normal menstrual and ovarian cycling in females or the failure to produce sperm in males. This can bring about infertility and/or result in pain during menstruation, intercourse and emptying of the bladder or bowel. In addition, an incorrect hormone balance throughout the body can have adverse effects on secondary sexual characteristics, such as the growth of facial hair in females or the growth of breasts in males.

The reproductive system

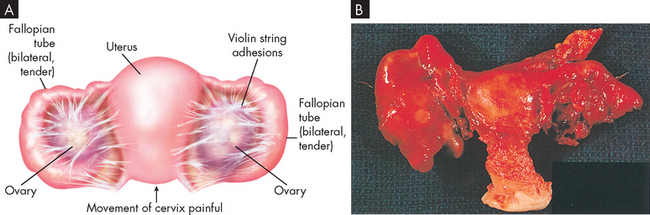

Structural and functional abnormalities of the reproductive system can be the result of the above-mentioned hormonal problems during development or they can arise as the result of trauma to the body or bacterial or viral infection of the reproductive tract. Trauma can give rise to ectopic implants of endometrial tissue in the myometrium, leading to dysfunctional bleeding and pain. This may also occur following a caesarean section. Infection causes inflammation in which immune cells are recruited to the site of infection and release inflammatory cytokines (see Chapter 13). Inflammation can lead to scarring or adhesions developing and these can interfere with normal ovarian or uterine function.

CANCER

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in females but is uncommon in males. Breast cancer has an incidence rate of almost 28% (expressed as a percentage of all cancers) — just over 12,000 new cases are detected in women in Australia each year.4 To put this in perspective, the number of females diagnosed with breast cancer each year is more than double the number diagnosed with colorectal cancer, the second most common cancer in females. In males, prostate cancer is by far the most commonly diagnosed cancer and accounts for 29.1% of all cancers.4 Like breast cancer in females, the rate of prostate cancer in males is more than double the rate of colorectal cancer, the second most common cancer in males.

Therefore, cancers of the reproductive system in both sexes are the most prevalent of all cancers. Breast cancer and prostate cancer are not the only cancers of the reproductive tract in either sex, but the incidence of other cancers is extremely low. For instance, of all female cancers, the incidence rates of other cancers of the reproductive tract are as follows: cervical cancer 1.7%, uterine cancer 3.8%, ovarian cancer 2.7%, vulvar cancer 0.6%, vaginal cancer 0.2% and cancer of all other gynaecological sites 0.2%.4 In males, the rates are testicular cancer 1.2%, breast cancer 0.2% and penile cancer 0.1%.4 The following discussion therefore focuses mainly on breast cancer and prostate cancer, which you are more likely to encounter in the healthcare setting. Additional discussion of general features of cancer can be found in Chapter 36.

Cancers of the female reproductive system

Breast cancer

Breast cancer is a disease in which abnormal cells in the breast tissues multiply and form an invasive or malignant tumour. Such tumours can invade and damage the tissue around them and then spread to other parts of the body through the lymphatic or vascular systems. If the spread is not controlled, they can result in death. Not all tumours are invasive; some are benign tumours that are not life-threatening.

The risk of being diagnosed with breast cancer before 85 years of age is 1 in 9, which equates to 35 females per day being diagnosed. Although some younger high-profile women have been diagnosed with breast cancer, the average age at diagnosis is 60 years. Unfortunately, of all cancers, breast cancer has a high mortality rate, second only to lung cancer, and in just one year in Australia, 2707 women die of breast cancer.5

Mammographic screening every 2 years is recommended for women aged 50–69 years, although it is also available to women from 40 years of age onwards. Younger women in high-risk groups may be screened by MRI. Symptoms can include: new lumps or thickening in the breast or under the arm, nipple sores, nipple discharge, breast skin dimpling, rash or red swollen breasts. Pain is rare, so regular checking of the breasts is recommended. If any symptoms are found, further diagnostic options such as imaging and biopsy are required.

Staging is rated according to the TMN (tumour, metastasis, node) classification system, which makes use of information on the size of the primary tumour (T), lymph node involvement (N) and the absence or presence of distant metastases (M). Invasive breast cancers are classified in a range from stage I (early disease) to stage IV (advanced disease). If the cancer is limited to the breast, 98% of patients will survive (survival is considered as being free of cancer 5 years after the cancer is detected). If the cancer has spread to the regional lymph nodes, the survival rate drops to 83%.6

Causes of breast cancer are similar to causes for many cancers in that there is a hereditary component, but there are also cases (known as sporadic cases) in which there is no family history (see below). Other factors are increasing age, inheritance of specific gene mutations (in the genes BRCA2, BRCA1 and CHEK2), exposure to female hormones (natural and administered), past exposure to radiation, obesity (diet and exercise) and excess alcohol consumption.

Risk factors

Risk factors and possible causes of breast cancer can be classified as reproductive, hormonal, environmental and familial (see Table 32-1).

Table 32-1 FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH INCREASED RISK OF BREAST CANCER

| CATEGORY | RISK FACTOR | RELATIVE RISK* |

|---|---|---|

| Family history | Postmenopausal in first-degree relative | ≤ 2.0 |

| Breast cancer in first-degree relative before age 60 years | 2.0–3.0 | |

| BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene | ≥ 4.0 | |

| Premenopausal or bilateral breast cancer | > 4.0 | |

| p53 (tumour-suppressor gene) | > 4.0 | |

| Breast cancer in 2 first-degree relatives | 4.0–6.0 | |

| Previous medical history | Moderate or florid mammary hyperplasia | 1.5–2.0 |

| Mammary papilloma | 1.5–2.0 | |

| Atypical mammary hyperplasia | 4.0–5.0 | |

| Ductal carcinoma in situ or lobular carcinoma in situ | 8.0–10.0 | |

| Oestrogen exposure | Early menarche (before age 12 years) | 1.1–1.9 |

| Late menopause (after age 55 years) | 1.1–1.9 | |

| Postmenopausal oestrogen therapy | 1.4 | |

| Oral contraceptive use | 1.5 | |

| Pregnancy | Nulliparous or late first pregnancy (after age 35 years) | 1.1–1.9 |

| Radiation | Repeated fluoroscopy (X-ray with a fluorescent screen) | 1.5–2.0 |

| Obesity and stature | Postmenopausal | 1.2 |

| Tallness | ≤ 2.0 | |

| Dietary/alcohol | High alcohol consumption | 1.4–2.0 |

| High energy intake | ≤ 2.0 | |

| Advanced age | 2.0–4.0 | |

| Social | Higher socioeconomic status | ≤ 2.0 |

| Low physical activity | ≤ 2.0 | |

| Smoking | 2.0–4.0 | |

| Environmental | Chemical carcinogens | ≤ 2.0 |

| Infectious agents | ≤ 2.0 | |

| * Relative risk is different to absolute risk (overall risk of developing a disease over time). Relative risk is the incidence rate of the disease among individuals exposed to the risk factor compared to the incidence rate of the disease in individuals not exposed to the risk factor. For instance, smokers have a higher risk of developing breast cancer than non-smokers. | ||

Source: Kumar V. Robbins & Cotran pathologic basis of disease. 7th edn. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2005.

Reproductive factors

A woman’s age when her first child is born affects her risk for developing breast cancer: the younger she is, the lower the risk. The main mechanism for the protective effect of pregnancy is controversial. The most widely accepted explanation proposes that the development and differentiation of the breast are completed only by the end of the first term of pregnancy. The protection seems to be the interval of time between menarche and the first pregnancy, because a greater risk is noted with an interval of more than 14 years. The protection conveyed early persists into old age, possibly because of lasting genetic change through differentiation.7 However, this is not entirely clear and research has shown evidence against this as well.

The duration of a woman’s reproductive life also affects her risk of developing breast cancer. Late menarche and early menopause (i.e. a short reproductive life) reduce risk. Menarche marks the onset of the mature hormonal environment — that is, cyclic hormonal changes that result in ovulation, menstruation and cellular proliferation in the breast. Thus, the younger the age at menarche, the earlier a young woman experiences steroid hormone levels and ovulatory cycles. Although data are limited, women with earlier menarche may have higher levels of endogenous oestrogen.8,9 Age of menarche is a relatively weak risk factor overall.

Hormonal factors

Endogenous hormones have long been implicated in the development of breast cancer. Most significant are the findings of: (1) the protective effect of an early first pregnancy; (2) the protective effect of bilateral oophorectomy (surgical removal of the ovary) before age 45 years; (3) the increased risk associated with early menarche, late menopause and nulliparity (never having carried a pregnancy); and (4) the hormone-dependent development and differentiation of mammary gland structures. A vast majority of breast cancers are initially hormone-dependent with oestrogen playing a crucial role in their development.10

Studies have shown that postmenopausal women who have elevated plasma levels of androgen of adrenal or ovarian origin or oestrogens have an increased risk of breast cancer.11 Studies assessing plasma levels of hormones among premenopausal women have produced conflicting results. These studies are more difficult because circulating levels of hormones vary greatly during the menstrual cycle and the low numbers of women with breast cancer among premenopausal women.

Insulin-like growth factors (IGFs) regulate cellular functions involving cell proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis. Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) is a protein hormone with a structure similar to insulin. The growth hormone-IGF-1 axis can stimulate proliferation of both breast cancer and normal breast epithelial cells.12 IGF-1 levels seem to be more of a risk factor for premenopausal women. In addition, premenopausal mammographic breast density (a risk factor for breast cancer) has been positively correlated with IGF-1 levels. This relationship has not been found in postmenopausal women.13

Controversy remains about the relationship between oral contraceptive use and breast cancer risk. In contrast, the efficacy of oral contraceptives in protecting against ovarian cancer and endometrial cancer is well established.

Environmental factors

The environmental causes of breast cancer probably affect the glandular epithelial cells of the breast during the early differential stages from undifferentiated cells to alveolar buds and lobules. During these early phases, mitotic activity and cell division are greater than later in life.14

Radiation. High doses of ionising radiation are associated with an increased risk of all cancers including breast cancer, especially if exposure occurs during adolescence or pregnancy, when breast cells are proliferating rapidly. Ionising radiation causes damage to a cell’s DNA (that is, it alters the sequence of genes). The genes most often affected are those that control the rate of cell division or the rate of cell death (apoptosis). Radiological exposure of the upper spine, heart, ribs, lungs, shoulders and oesophagus also exposes breast tissue to radiation.

Radiation. High doses of ionising radiation are associated with an increased risk of all cancers including breast cancer, especially if exposure occurs during adolescence or pregnancy, when breast cells are proliferating rapidly. Ionising radiation causes damage to a cell’s DNA (that is, it alters the sequence of genes). The genes most often affected are those that control the rate of cell division or the rate of cell death (apoptosis). Radiological exposure of the upper spine, heart, ribs, lungs, shoulders and oesophagus also exposes breast tissue to radiation. Smoking. This is known as a risk factor for development of all forms of cancer, not specifically breast cancer. The association is probably due to the harmful chemicals in cigarette smoke, which cause DNA damage and thereby initiate the development of a tumour.

Smoking. This is known as a risk factor for development of all forms of cancer, not specifically breast cancer. The association is probably due to the harmful chemicals in cigarette smoke, which cause DNA damage and thereby initiate the development of a tumour. Diet. The association between individual foods and breast cancer is inconsistent and new data on dietary patterns are emerging. The prudent pattern includes a higher intake of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low-fat dairy products, fish and poultry. The Western pattern includes a higher intake of red and processed meats, refined grains, sweets and desserts, and high-fat dairy products. In general, however, neither pattern has been associated with an overall risk of postmenopausal breast cancer. However, a lower risk of oestrogen receptor-negative cancer has been observed in those on a prudent diet.15

Diet. The association between individual foods and breast cancer is inconsistent and new data on dietary patterns are emerging. The prudent pattern includes a higher intake of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low-fat dairy products, fish and poultry. The Western pattern includes a higher intake of red and processed meats, refined grains, sweets and desserts, and high-fat dairy products. In general, however, neither pattern has been associated with an overall risk of postmenopausal breast cancer. However, a lower risk of oestrogen receptor-negative cancer has been observed in those on a prudent diet.15Most studies have not supported a link between fibre intake and breast cancer.16,17 Carbohydrate quality, however, rather than absolute amount, may be important for breast cancer risk, especially for premenopausal women. Substantial evidence exists that alcohol consumption increases breast cancer risk.18 Differences in alcohol intake, however, explain only a small fraction of breast cancer rates.19,20 The mechanisms by which alcohol intake increases the risk of breast cancer are unknown. It is not known whether decreasing or stopping alcohol consumption in midlife decreases the risk of breast cancer.

Obesity. Obesity has been associated with a reduced risk of premenopausal breast cancer. One mechanism suggested is the direct relationship between irregular menstrual cycling, especially anovulatory (lack of ovulation) cycling, and obesity. Anovulatory cycling would result in a decrease in both oestrogen and progesterone and thus a decreased risk of breast cancer. Some obese women have polycystic ovaries. With this condition they may have anovulatory cycling, abnormal menstrual periods, elevated androgens and hyperinsulinaemia (see Chapter 35). It is possible that higher insulin levels increase the enzymatic conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone, rather than oestradiol (a type of oestrogen), lowering their oestrogen levels.21

Obesity. Obesity has been associated with a reduced risk of premenopausal breast cancer. One mechanism suggested is the direct relationship between irregular menstrual cycling, especially anovulatory (lack of ovulation) cycling, and obesity. Anovulatory cycling would result in a decrease in both oestrogen and progesterone and thus a decreased risk of breast cancer. Some obese women have polycystic ovaries. With this condition they may have anovulatory cycling, abnormal menstrual periods, elevated androgens and hyperinsulinaemia (see Chapter 35). It is possible that higher insulin levels increase the enzymatic conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone, rather than oestradiol (a type of oestrogen), lowering their oestrogen levels.21

Obesity is associated with poor survival among women with breast cancer and the association of obesity with mortality from breast cancer appears to be stronger than its association with incidence.22,23 Obesity, however, is weakly related to increasing the risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women:24 despite strong links with endogenous oestrogen levels, body fat has been consistently but weakly related to increased postmenopausal risk.25 This observation has been surprising because obese postmenopausal women have endogenous oestrogen levels nearly double those of lean women.26,27 This weak association is possibly due to the following: the premenopausal reduction in breast cancer risk related to being overweight may persist, opposing the adverse effect of elevated oestrogen after menopause. Thus, weight gain should be more strongly related to postmenopausal breast cancer risk than attained weight. The increase in breast cancer risk with increasing body mass index (see Chapter 35) among postmenopausal women is possibly the result of increases in oestrogen, especially with oestradiol.24,27 Studies do not support the concept that fat intake in middle life has a major relationship with breast cancer risk.28

Physical activity. Regular physical activity may reduce the overall risk of breast cancer, especially in premenopausal or young postmenopausal women.29–31 4 6 Activity may also reduce invasive breast cancer.32 The mechanisms for this protective effect are not known but include alterations in endogenous free radical formation and oxidative damage (see Chapter 4), effects on DNA repair capacity, increased intestinal transit times (that is, reduced exposures to carcinogens), weight loss and changes in endogenous sex hormone levels.30,31

Physical activity. Regular physical activity may reduce the overall risk of breast cancer, especially in premenopausal or young postmenopausal women.29–31 4 6 Activity may also reduce invasive breast cancer.32 The mechanisms for this protective effect are not known but include alterations in endogenous free radical formation and oxidative damage (see Chapter 4), effects on DNA repair capacity, increased intestinal transit times (that is, reduced exposures to carcinogens), weight loss and changes in endogenous sex hormone levels.30,31Familial factors

Genetically, breast cancer can be divided into three main groups: (1) sporadic — the majority, or 40%, of women with breast cancer have no known family history; (2) inherited autosomal dominant cancer gene syndromes; and (3) polygenic, where there is a family history but it is not passed on to future generations as a dominant gene.

A history of breast cancer in first-degree relatives (mother or sister) increases a woman’s risk two to three times. Risk increases even more if two first-degree relatives are involved, especially if the disease occurred before menopause and was bilateral. A small proportion of breast cancers (5–10%) are the result of highly penetrant dominant genes (that is, hereditary breast cancers).

The most important of the dominant genes are the breast cancer susceptibility genes: BRCA1 and BRCA2. BRCA1 is located on chromosome 17 and BRCA2 is located on chromosome 13. A family history of both breast and ovarian cancer increases the risk that an individual with breast cancer carries a BRCA1 mutation. Up to age 40, a woman with a BRCA1 mutation is estimated to have a 20-times greater risk of breast cancer compared to the general population and a lifetime risk of 60–85%.31 Carriers of the BRCA1 gene are also at higher risk for ovarian cancer. BRCA1 is a tumour-suppressor gene; therefore, any mutation in the gene may inhibit or retard its suppressor function, leading to uncontrolled cell proliferation.33 Interestingly, men who develop breast cancer are more likely to have a BRCA2 mutation than a BRCA1 mutation.

Another tumour suppressor gene, p53, is mutated in approximately 20–40% of individuals with breast cancer.34 p53 is a regulatory gene (that is, it acts to turn mechanisms on or off) that increases DNA repair and, if damage is great, cell death (apoptosis) occurs in mutated cells. Thus, it helps to get rid of cancer proliferating cells. When p53 is mutated, its regulatory properties are radically altered, conferring a loss of tumour-suppressor activity and, possibly, allowing tumour growth.

PATHOGENESIS

Most breast cancers (70%) arise from the epithelial linings of the lactiferous ducts. The reason that these types of tumours account for a high mortality is most likely due to the regular cycles of hormone-induced proliferation (see Chapter 31). It is important to realise that these types of tumours do not grow to a large size, but they often metastasise early, which makes treatment more difficult and contributes to an increased mortality. The pathogenesis (like that of other cancers) involves several main steps:

Unlike most human organs that are differentiated at the end of fetal life, the mammary glands develop and differentiate after puberty. Factors that affect full differentiation of the breast may be essential for countering the development of breast cancer.

Mammary epithelial cells achieve rapid renewal by a small number of mitotic divisions of immortal stem cells. Because the number of mutations is proportional to the rate and number of stem cell divisions, factors that accelerate cell division can have a carcinogenic effect. Hormones may act as accelerators, as well as initiators, and influence the susceptibility of the breast epithelium to environmental carcinogens, because hormones control the differentiation of the mammary gland epithelium and thereby regulate the rate of stem cell division.

In each ovulatory cycle between puberty and either the first full-term pregnancy or menopause among nulliparous women, mammary epithelium stem cells show their greatest rate of division during the luteal phase. In this phase progesterone levels predominate and the breast cells display increased mitosis (the reasons for this are not yet clear).35,36 During the oestrogen follicular phase, terminal ductules are few and there is no mitotic activity. During the luteal phase, because of increased progesterone levels perhaps resulting from the oestrogen priming or as a result of cooperation between the two hormones, there is increased mitotic activity.37,38

Emerging is the understanding that the biological and structural features of carcinomas usually begin at the in situ stage.39 The in situ lesion closely resembles the developing invasive carcinoma.39 For example, low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ (cells that have changed in the lining of the ducts of the breast) with well-differentiated carcinomas, high-grade ductal carcinoma in situ with high-grade carcinomas and lobular carcinomas are associated with lobular carcinoma in situ. Ductal carcinoma in situ is a clonal proliferation (genetically identical cells that rapidly multiply) usually confined to a single ductal system. Lobular carcinoma in situ, unlike ductal carcinoma in situ, has a uniform appearance in which the cells occur in non-cohesive clusters in ducts and lobules. It is important to understand that these are not invasive breast cancers, but rather abnormal changes in the cells. However, both are associated with an increased risk of developing invasive breast cancer.

The majority of carcinomas of the breast occur in the upper outer quadrant, where most of the glandular tissue of the breast is located. The lymphatic spread of cancer to the opposite breast, to lymph nodes in the base of the neck and to the abdominal cavity is caused by obstruction of the normal lymphatic pathways or destruction of lymphatic vessels by surgery or radiotherapy. The less common inner quadrant tumours may spread to mediastinal nodes, which are located between the pectoral muscles.

Internal mammary chain nodes are also common sites of metastasis. Metastases from the vertebral veins can involve the vertebrae, pelvic bones, ribs and skull. The lungs, kidneys, liver, adrenal glands, ovaries and pituitary gland are also sites of metastasis.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The first sign of breast cancer is usually a painless lump. Lumps caused by breast tumours do not have any classic characteristics. Other presenting signs include palpable nodes in the axilla (underarm), retraction of tissue (dimpling) or bone pain caused by metastasis to the vertebrae. Table 32-2 summarises the clinical manifestations of breast cancer. Manifestations vary according to the type of tumour and stage of disease.

Table 32-2 CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF BREAST CANCER

| CLINICAL MANIFESTATION | PATHOPHYSIOLOGY |

|---|---|

| Local pain | Local obstruction caused by the tumour |

| Dimpling of the skin | Can occur with invasion of the dermal lymphatics because of retraction of Cooper’s ligament or involvement of the pectoralis fascia |

| Nipple retraction | Shortening of the mammary ducts |

| Skin retraction | Involvement of the suspensory ligament |

| Oedema | Local inflammation or lymphatic obstruction |

| Nipple/areolar eczema | Paget’s disease |

| Pitting of the skin (similar to the surface of an orange) | Obstruction of the subcutaneous lymphatics, resulting in the accumulation of fluid |

| Reddened skin, local tenderness and warmth | Inflammation |

| Dilated blood vessels | Obstruction of venous return by a fast-growing tumour; obstruction dilates superficial veins |

| Nipple discharge in a non-lactating woman | Spontaneous and intermittent discharge caused by tumour obstruction |

| Ulceration | Tumour necrosis |

| Haemorrhage | Erosion of blood vessels |

| Oedema of the arm | Obstruction of lymphatic drainage in the axilla |

| Chest pain | Metastasis to the lung |

Source: Based on Griffiths MJ, Murray KH, Russo PC. Oncology nursing: pathophysiology, assessment, and intervention. New York: Macmillan; 1984.

EVALUATION AND TREATMENT

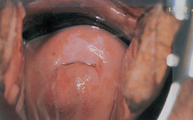

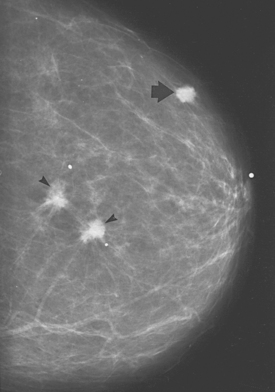

Mammography, ultrasound, percutaneous needle aspiration, biopsy or minimally invasive biopsy called Mammotome, palpation and hormone receptor assays are generally used in evaluating breast alterations and cancer (see Figure 32-1). Biopsy is the definitive diagnostic test (see Figure 32-2).

FIGURE 32-1 Invasive breast carcinoma.

Two irregular carcinomas (arrowheads) are present in one quadrant, representing ‘multifocal’ carcinoma. The presence of a third lesion (arrow) in another quadrant leads to the designation ‘multicentric’.

Source: Bassett LW. Diagnosis of diseases of the breast, 2nd edn. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2005.

FIGURE 32-2 Needle biopsy and aspiration with negative pressure.

The needle is rotated, moved back and forth, and slightly in and out to aspirate representative specimen.

Source: Katz VL et al. Comprehensive gynecology. 5th edn. St Louis: Mosby; 2007.

Treatment is based on the extent or stage of the cancer. The extent of the tumour at the primary site, the presence and extent of lymph node metastasis and the presence of distant metastases are all evaluated to determine the stage of disease. For localised breast cancer, the most extensive surgical option would be removing the breast and lymph nodes under the arm. Removing the lump and just a section of the breast followed by radiotherapy results in the same rate of survival. If the first draining lymph node can be identified using dye or a nuclear medicine scan, it can be sampled and, if negative, further surgery avoided.

For tumours at greater risk of recurrence, such as bigger more aggressive-looking tumours that have spread to the lymph nodes, additional treatment (adjuvant therapy) can be given after surgery. This may include hormone therapy of aromatase inhibitors or tamoxifen for women whose tumours have hormone receptors on their surfaces, chemotherapy and targeted therapies such as trastuzumab for those 25% of tumours that are HER2-positive (that is, have the target for trastuzumab on their surfaces). Patients presenting with locally extensive cancer will have chemotherapy and radiotherapy initially to see whether they can shrink the cancer to become operable. If breast cancer returns after initial treatment, local disease may be treated with surgery, while more widespread disease will be treated with combinations of similar drugs to those listed for the adjuvant setting, as is the case for patients who present with widespread disease. Common chemotherapy drugs include anthracyclines and taxanes. Patients with bone disease can receive bisphosphonates such as zoledronate to slow the erosion of bone as well as local radiotherapy for pain.

Cervical cancer

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), also known as cervical dysplasia, is the potentially premalignant transformation and abnormal growth (dysplasia) of squamous cells on the surface of the cervix.40 It is more common than invasive cancer and occurs more often in younger women, with 1 in 8 young women having cervical dysplasia by the age of 20 years. The premalignant features of CIN, such as genetic abnormalities, loss of cellular function and some phenotypic characteristics of cancer, predict the risk of developing an invasive cancer. Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a necessary precursor to the development of the vast majority of cases of cervical cancer (see the box ‘Health alert: vaccine offers promise of cervical cancer prevention’).41,42

Some risk factors have been found to be important in developing CIN — for example, having multiple sexual partners, being infected with higher risk types of HPV, smoking and being immunodeficient. In addition, engaging in sexual intercourse before the age of 16 and having intercourse with a male partner who has had multiple partners place a woman at risk.

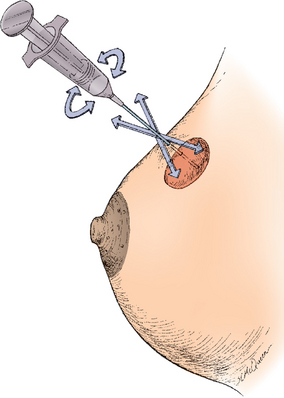

Cervical cancer is a progressive disease, moving from normal cervical epithelial cells to dysplasia to CIN to invasive cancer. Figure 32-3 summarises the progressive degrees of CIN. Premalignant lesions usually occur 10–12 years before the development of invasive carcinoma. Cervical neoplasms are often asymptomatic, so regular Pap smears are necessary to monitor development. About 90% of cervical cancers can be detected early through the use of Pap smears and HPV testing. The incidence of cervical cancer is in fact already declining in Australia and New Zealand, which is likely to be due to regular pap smear tests (see Chapter 36).

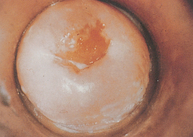

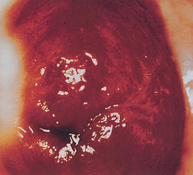

FIGURE 32-3 Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia.

A A diagram of cervical endothelium showing progressive degrees of CIN. B Normal multiparous cervix. C CIN stage 1. Note the white appearance of part of the anterior lip of the cervix associated with neoplastic changes.

Source: A Herbst AL et al. Comprehensive gynecology. 2nd edn. St Louis: Mosby; 1992. B & C Symonds EM, Macpherson MBA. Color atlas of obstetrics and gynecology. London: Mosby; 1994.

Vaccine offers promise of cervical cancer prevention

In 2006 the TGA approved a vaccine (Gardisil) developed in Australia and produced by Merck against human papillomavirus (HPV) types 6, 11, 16, and 18. HPV types 16 and 18 are responsible for 70% of all cervical cancers, and HPV types 6 and 11 are associated with benign genital warts. The vaccine is given in a series of 3 shots to girls and young women aged 9–26. In clinical trials, the vaccine was 90% effective in preventing these types of HPV. It does not, however, replace the need for screening with a Pap test.

Source: Joura EA et al. Efficacy of a quadrivalent prophylactic human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16 and 18) L1 virus-like-particle vaccine against high-grade vulval and vaginal lesions: a combined analysis of three randomised clinical trials. Lancet 2007; 369(9574):1693–1927; The FUTURE II Study Group. Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent high-grade cervical lesions. N Engl J Med 2007; 356(19):1915–1927; Villa LL et al. Prophylactic quadrivalent human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16 and 18) L1 virus-like particle vaccine in young women: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled multicentre phase II efficacy trial. Lancet 2005; 6(5):271–278.

There are often no symptoms but, if present, they may include a change in vaginal discharge or bleeding either after intercourse or between menstrual periods. At times, women will complain of abnormal menses or postmenopausal bleeding. A less common symptom may be a yellowish vaginal discharge. A new or foul odour also may be present. Pelvic or epigastric pain is experienced only with large lesions. Severe bleeding may cause anaemia. Advanced disease may cause urinary or rectal symptoms and pelvic or back pain. When dysplasia is detected, cervical biopsy and endocervical curettage are required. Colposcopy (visualisation of the cervix using a camera and light source) is used to suggest sites for biopsy. If invasive carcinoma is found, lymphangiography (X-ray of lymph nodes and lymph vessels), CT scanning, ultrasonography or radio-immunodetection methods (use of radioactive antibodies to detect neoplasms) are used to assess lymphatic involvement.

The treatment depends on the degree of neoplastic change, the size and location of the lesion and the extent of metastatic spread. With early detection and treatment, prognosis for invasive cervical cancer is excellent. Overall, the 5-year survival rate is 70% and it increases to 92% with early diagnosis.

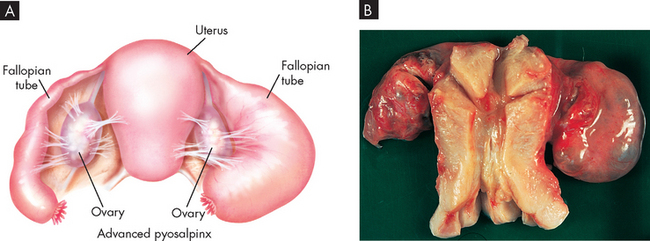

Ovarian cancer

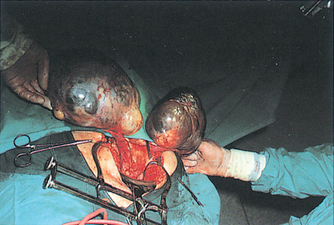

The cause of ovarian cancer is unknown, but multiple studies agree that an increased risk of epithelial ovarian cancer has been linked to advancing age, a family history of breast or ovarian cancer and frequency of ovulation.43 The dismal overall prognosis for women with ovarian cancer results from an inability to detect ovarian cancer early when treatment might result in cure and from our incomplete understanding of the early changes in the ovary before the development of cancer and the initiators of these changes.43 More than 90% of ovarian cancers arise from the ovarian surface epithelium,44 although cancers can also arise from germ cells of the ovarian stroma (connective tissue). Germ cell tumours occur in younger women, whereas those from epithelial tissue occur in women over 40 (see Figure 32-4).

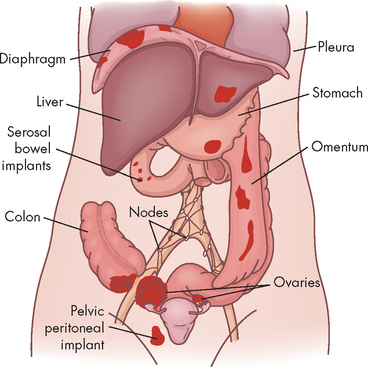

Ovarian cancers exhibit a distinctive pattern of progression, spreading intra-abdominally over the surface of the peritoneum. It is often considered a silent disease, meaning that by the time the individual experiences symptoms and seeks treatment, the disease has spread beyond the primary site (see Figure 32-5). The most obvious symptoms are pain and abdominal swelling (ascites) that arise from the primary ovarian tumour mass. Gastrointestinal complaints resulting from mechanical obstruction by the tumour may include dyspepsia (abdominal discomfort, such as indigestion), vomiting and alterations in bowel habits. Abnormal vaginal bleeding may occur if the postmenopausal endometrium is stimulated by a hormone-secreting tumour. The tumour may also cause ulcerations through the vaginal wall that result in bleeding. There also can be a feeling of pressure in the pelvis and leg pain.45

Because ovarian cancer has no early symptoms and there are no effective screening techniques to detect it, the disease is usually advanced by the time treatment is sought. Transvaginal ultrasound and a tumour marker (CA-125) may assist diagnosis but are not recommended for routine screening. The initial approach to treatment is surgery, performed to determine the stage of disease and to remove as much of the tumour as possible. Radiation therapy may follow if the tumour is smaller than 2 cm in size and is confined to the abdominopelvic area without involvement of the kidneys or liver. The success of chemotherapy depends on the extent of disease, whether the tumour is a discrete mass and whether there has been prior exposure to chemotherapeutic agents.

Cancers of the male reproductive system

Prostate cancer

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in men, with 85% of cases being diagnosed in those over the age of 65 years. Just over 16,000 cases of prostate cancer (nearly 30% of male cancers) are diagnosed each year in Australia.46 The risk of prostate cancer rises with age, increasing rapidly after age 50. Family history increases the chances of developing the disease. There has been some association with a diet high in fats and low in fresh fruit and vegetables. Men of African descent are at higher risk than men of European descent and there is an association with high testosterone levels. Other possible causes are those of genetic predisposition (familial and hereditary forms). As with breast cancer, there are a number of risk factors, with tobacco use having a significant impact on the occurrence of fatal prostate cancer.47

Risk factors

Diet

The worldwide distribution of prostate cancer suggests that diet may play a role in its development, especially if the diet affects hormone levels. Consistency across studies indicates that a high intake of fat (total and especially saturated fat) is a risk factor for prostate cancer.48–50 4 6 Several hypotheses exist concerning the enhancing effect of fat on prostate carcinogenesis, including hormonal and the generation of free radicals (see Chapter 4). Fat intake from dairy products increases calcium, itself a proposed risk factor. Calcium can suppress circulating levels of vitamin D, a possible protective factor for prostate cancer.51 In addition, a low intake of dietary fibre and complex carbohydrates and a high intake of protein are associated with an increased risk of prostate cancer.50 It remains controversial whether obesity or an increased body mass index is a risk factor for prostate cancer.

Nutritional and chemopreventive agents for risk reduction of prostate cancer

Several areas of investigation are identifying prospective therapies for prostate cancer prevention. Several studies found antioxidants to be potential chemopreventive agents. Individuals with high antioxidant levels (such as vitamin E and selenium) have a 42% reduction in prostate cancer risk. The effect was higher (59% reduction) in those with high-grade or high-stage cancer risk. Many chemopreventive agents that have been identified in laboratory studies — including silibinin (from milk thistle), inositol hexaphosphate (a form of carbohydrate in cereals, legumes, oil seeds and nuts), apigenin and acacetin (fruits and vegetables), grape seed extract, curcumin and green tea — could be useful against prostate cancer.

Source: Kantoff P. Prevention, complementary therapies, and new scientific developments in the field of prostate cancer. Rev Urol 2006; 8(suppl 1):S9–S14; Singh RP, Agarwal R. Mechanisms of action of novel agents for prostate cancer chemoprevention. Endocr Relat Cancer 2006; 13(3):751–778, review.

Individual nutrients or foods and their associations with prostate cancer risk are not strong, yet migration of individuals from low-risk geographic areas of the world, such as Japan, to high-risk countries, such as Australia and New Zealand, increases risk considerably. These changes in risk probably reflect differences in lifestyle and dietary habits. Geographically, individuals who reside in regions with less sunlight have a higher risk of prostate cancer. The highest rates of mortality from prostate cancer are in Scandinavian countries, where exposure to ultraviolet light is low; the possible link is less vitamin D induced by less sun exposure.

Hormones

Prostate cancer develops in an androgen-dependent epithelium and is usually androgen sensitive. In addition, a few case reports of prostate cancer in men who used androgenic steroids as anabolic agents or for medical purposes suggest a causal relationship.49,52–54 4 6 Population studies have not, however, provided clear and convincing patterns involving associations between circulating hormone concentrations and prostate cancer risk.48,55

Investigations directed at understanding the hormonal basis of prostate (as well as breast) carcinogenesis have numerous problems. The complexities of interacting hormones and separating out the effects of a single hormone are profound. In addition, only single blood samples are generally available, tissue hormone samples are not consistently measured and within-subject variations over time and differences in circadian rhythms cannot be adequately measured. Therefore, while the role of hormones in the implication of prostate cancer development may be relevant, the evidence is yet to find a direct link.

Chronic inflammation

The results of a 5-year, longitudinal study of the influence of chronic inflammation and prostate cancer have been reported.56 Biopsies revealed prostatic hyperplasia (see ‘Disorders of the male reproductive system’ below) and inflammatory atrophy in those with chronic inflammation. Upon repeat biopsy, new cancers were diagnosed.56 In contrast, of the men initially showing no inflammation, only a small number were found to have adenocarcinoma. Thus, chronic inflammation may be an important risk factor for prostatic adenocarcinoma. An inflammatory process could possibly account for the evidence that antioxidants and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as aspirin, may be protective.51,56,57

Familial factors

Other possible causes are those of genetic predisposition (familial and hereditary forms). Genetic studies suggest that strong familial predisposition may be responsible for 5–10% of prostate cancers.58 Hereditary cancer differs from the familial form, which occurs in individuals with a positive family history but who do not exhibit early age of onset.59 The hereditary form constitutes about 9% of all prostate cancers and approximately 43% of cancers in men younger than 55 years of age.60 There is no clear evidence of a causal link between benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer, even though they may often occur together.

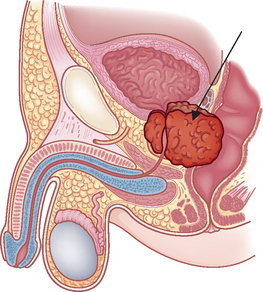

PATHOGENESIS

More than 95% of prostatic neoplasms are adenocarcinomas,61 and most occur in the periphery of the prostate. The biological aggressiveness of the neoplasm appears to be related to the degree of differentiation rather than the size of the tumour (see Box 32-1).

Box 32-1 PROSTATIC CANCER GRADES

Grade 1. The cancer cells closely resemble normal cells. They are small, uniform in shape, evenly spaced and well differentiated (that is, they remain separate from one another).

Grade 2. The cancer cells are still well differentiated, but they are arranged more loosely and are irregular in shape and size. Some of the cancer cells have invaded the neighbouring prostate tissue.

Grade 3. This is the most common grade. The cells are less well differentiated (some have fused into clumps) and are more variable in shape.

Grade 4. The cells are poorly differentiated and highly irregular in shape. Invasion of the neighbouring prostate tissue has progressed further.

Grade 5. The cells are undifferentiated. They have merged into large masses that no longer resemble normal prostate cells. Invasion of the surrounding tissue is extensive.

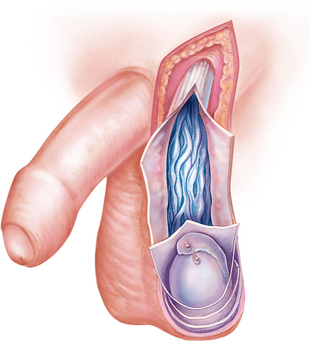

Although steroid hormonal factors are strongly implicated in prostate carcinogenesis, little is known about their involvement. Just as the testicles are the male equivalent of the female ovaries, the prostate is the male equivalent of the female uterus.

Testosterone is the major circulating androgen, whereas dihydrotestosterone (a biological active metabolite of testosterone, important in the development of male sexual characteristics) predominates in prostate tissue and binds to the androgen receptor with greater affinity than does testosterone.62 Testosterone is the major androgen that comes from the interstitial cells of the testis (Leydig cells). The adrenal cortex produces far less potent androgen than the testis.

There are significant age-dependent alterations in the hormones, although these vary in different prostate tissues. In epithelium, the level of dihydrotestosterone decreases with age; whereas in stroma (connective tissue), the dihydrotestosterone level is rather constant. Interestingly, the oestrogen content (males do produce small amounts of oestrogen) in the stroma increases with age. Therefore, the ratio of oestrogen to androgens alters substantially with age. In animal studies, chronic exposure to testosterone plus oestradiol is strongly carcinogenic.48 The mechanism is not clearly understood and may involve oestrogen-generated oxidative stress and DNA toxicity.48

From all of these observations, the following multifactorial general hypothesis of prostate carcinogenesis emerges. Androgens act as strong tumour promoters to enhance the weak but continuously present carcinogen to affect genes and possibly unknown environmental carcinogens. All of these factors are modulated by diet and genetic determinants, including multifactorial inheritance which is influenced by multiple genes (see Chapter 37). These genes encode receptors and enzymes involved in the metabolism and action of steroid hormones.48

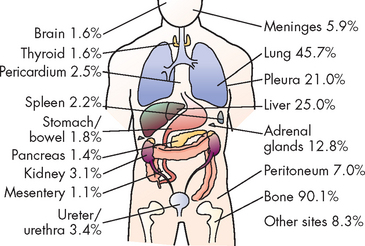

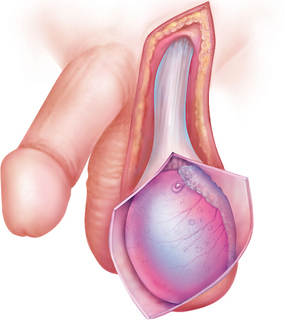

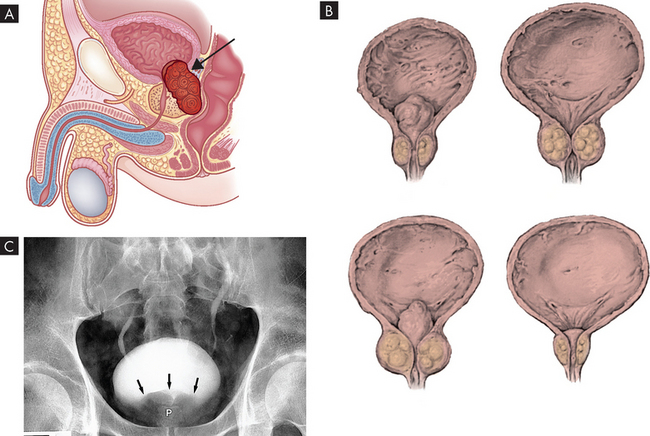

The microenvironment (stroma) surrounding the prostatic tumour actively fuels the progression of prostate cancer from localised growth, to invasion, to development of distant metastases.63 The most common sites of distant metastasis are the lymph nodes, bones, lungs, liver and adrenals. The pelvis, lumbar spine, femur, thoracic spine and ribs are the most common sites of bone metastasis. Local extension is usually posterior, although late in the disease the tumour may invade the rectum or encroach on the prostatic urethra and cause bladder outlet obstruction (see Figure 32-6). The spread of cancer through blood vessels is illustrated in Figure 32-7.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Prostatic cancer often causes no symptoms until it is far advanced. Therefore, routine screening is recommended for asymptomatic men beginning at age 50 — or 45 if they are considered at high risk. The first manifestations of disease are those of bladder outlet obstruction. Since the urethra passes through the prostate (see Chapter 31) any enlargement will have an effect on the flow of urine from the bladder. Symptoms therefore include frequent low-volume urination (particularly at night), pain on urination, blood in the urine and a weak stream. Local extension of prostatic cancer can obstruct the upper urinary tract ureters as well. Rectal obstruction also may occur, causing the individual to experience large bowel obstruction or difficulty in defecation. Symptoms of late disease include bone pain at the sites of bone metastasis, oedema of the lower extremities, enlargement of the lymph nodes, liver enlargement, pathological bone fractures and mental confusion associated with brain metastases. Prostatic cancer and its treatment can affect sexual functioning.

EVALUATION AND TREATMENT

Diagnosis is made using a digital rectal examination to feel the prostate and a blood test for prostate-specific antigen (PSA) (see Box 32-2). More than 95% of prostatic neoplasms are adenocarcinomas31 and most occur in the periphery of the prostate. Bone scans and CT scans are used to determine spread.

In Australia, it is clear that the profile of prostate cancer has risen significantly due to media coverage and that many more men over the age of 40 are seeking PSA and digital rectal exam (DRE) testing. There is growing pressure on state health authorities to initiate widespread screening, but this is being resisted for several reasons. For example, multiple stages of testing (PSA/DRE and biopsy) are required before a definitive diagnosis of prostate cancer can be given. In addition, PSA levels can be elevated for up to 10 years before any prostate cancer has developed, and invasive procedures (biopsy) can lead to urological problems and infections giving otherwise healthy men immediate problems. There is no clear evidence from population-based studies that a positive (raised) PSA level indicates that prostate cancer will develop. Thus, there can be no real justification for widespread PSA screening of all men over 40 years. The issue will be resolved only with more research into prostate cancer and more definitive and less invasive subsequent testing.

Source: Holden CA et al. Men in Australia Telephone Survey (MATeS): predictors of men’s help-seeking behaviour for reproductive health disorders. MJA 2006; 185:418–422; Carrière P et al. Cancer screening in Queensland men. MJA 2007; 186(8): 404–407; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. BreastScreen Australia monitoring report, 2004–2005. Cancer series no. 42. Catalogue no. CAN 37. Canberra: AIHW; 2008; Smith D et al. Prostate cancer and prostate-specific antigen testing in New South Wales. MJA 2008; 189(6):315–318; www.andrologyaustralia.org/docs/AndrologyAustralia_PSAposition_webversion_140509.pdf; www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/bhcv2/bhcarticles.nsf/pages/Prostate_cancer_and_the_PSA_test.

Treatment of prostate cancer depends on the stage of the disease (see Box 32-1), the anticipated effects of treatment and the age, general health and life expectancy of the individual. Options range from hormonal or radiation therapy or chemotherapy to surgery (contemporary nerve sparing or robotic surgery), any combination of these or no treatment. Low-grade disease confined to the prostate can be watched (surveillance) if not causing symptoms. It is desirable to avoid the side effects of surgery; however, early surgery may be of benefit. Surgery with curative intent removes the whole prostate (radical prostatectomy). The main side effects are impotence and incontinence. Radical radiotherapy can also be given with curative intent, either with external radiation or by implanting radioactive seeds (brachytherapy). Side effects are similar to surgery, and bowel problems may also occur.

For widespread disease, hormone therapy reduces the stimulus of the male hormones. Removal of the testis or injecting luteinising hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) or anti-androgen hormones can hold the disease for 3–4 years and may improve outcomes if undertaken early with radiation in high-risk patients. When hormone resistance occurs, chemotherapy with docetaxel can be used or mitoxantrone can control symptoms. Bisphosphonates (e.g. zoldedronate) can be use to help control bone metastases. Nearly all patients who present with localised disease will live beyond 5 years, with the 10- and 15-year survival rates being 93% and 77%, respectively.64

Treatment for prostate cancer may lead to loss of urinary control, which can return to normal after several weeks or months. Mild stress incontinence can occur after surgery and mild urge incontinence after radiation therapy. Prostate cancer and its treatment can affect sexual functioning. Most men will need assistance (medication) with obtaining an erection for 3–12 months after surgery. Sensation of orgasm is not usually affected, but smaller amounts of ejaculate will be produced or men may experience a ‘dry’ ejaculate because of retrograde ejaculation.

Palliative treatment is aimed at relieving urinary, bladder outlet or colon obstruction, spinal cord compression and pain.

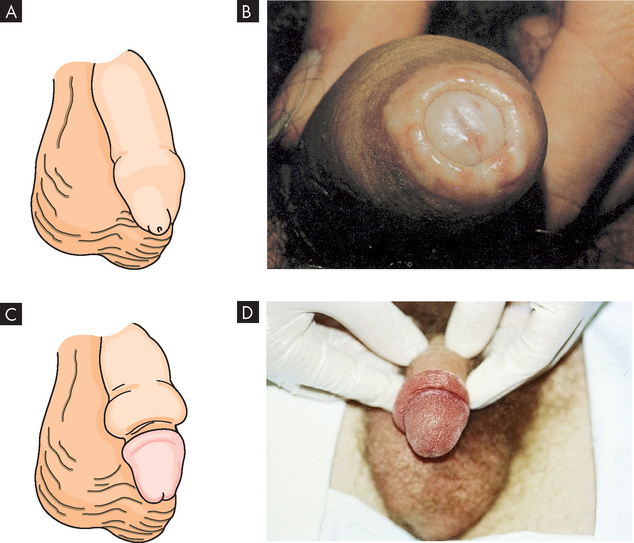

Testicular cancer

Testicular cancer is among the most curable of cancers, with cure rates greater than 95%. Overall, testicular cancer is uncommon, accounting for approximately 1.2% of all male cancers. However, it is the most common solid tumour of young adult men.65 Cancer of the testis occurs most commonly in men between the ages of 15 and 35 years.65 Testicular tumours are slightly more common on the right side than on the left, a pattern that parallels the occurrence of cryptorchidism (lack of one testis or both testes from the scrotum) and they are bilateral in 1–3% of cases. The profile of testicular cancer in the general public is high due mainly to one man: Lance Armstrong. An American professional road cyclist, Armstrong was diagnosed with testicular cancer at the age of 25. He underwent surgery and chemotherapy for a metastasised tumour, and has gone on to win the Tour de France, the most popular cycle race in the world, seven times, as well as to set up a cancer foundation, which has raised the profile of all cancers worldwide.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Some 90% of testicular cancers are germ cell tumours, arising from the male gametes. Germ cell tumours include seminomas, embryonal carcinomas, teratomas and choriosarcomas. Testicular tumours can also arise from specialised cells of the gonadal stroma. These tumours, which are named for their cellular origins, are the Leydig cell, sustentacular (Sertoli) cell, granulosa cell and theca cell tumours.

The cause of testicular neoplasms is unknown. A genetic predisposition is suggested by the fact that the incidence is higher among brothers, identical twins and other close male relatives. Genetic predisposition is supported by statistics showing that the disease is relatively rare among Africans, Asians and indigenous New Zealanders. A history of trauma or infection is also associated with the development of testicular neoplasms, but it may be that coexisting testicular tumours are discovered by accident in men who undergo examination because of trauma or infections.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

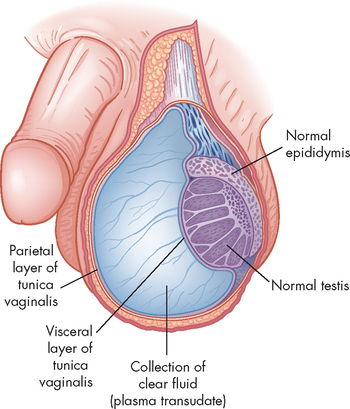

Painless testicular enlargement is commonly the first sign of testicular cancer (Figure 32-8). Occurring gradually, it may be accompanied by a sensation of testicular heaviness or a dull ache in the lower abdomen. Occasionally acute pain occurs because of rapid growth resulting in haemorrhage and necrosis. Of those affected, 10% have epididymitis (see ‘Disorders of the scrotom, testis and epididymis’ below), 10% have hydroceles (fluid collection in the scrotal sac) and 5% have breast enlargement (gynaecomastia). The testicular mass is usually discovered by the individual or by his sexual partner. At the time of initial diagnosis, approximately 10% of individuals already have symptoms related to metastases. Lumbar pain may also be present and is usually caused by retroperitoneal node metastasis. Signs of metastasis to the lungs include cough, dyspnoea (difficulty breathing) and haemoptysis (bloody sputum). Supraclavicular node involvement may cause difficulty swallowing (dysphagia) and neck swelling. With metastasis to the central nervous system, alterations in vision or mental status and seizures may be experienced.

EVALUATION AND TREATMENT

Evaluation begins with careful physical examination, including palpation of the scrotal contents with the individual in the erect (standing) and supine positions. Signs of testicular cancer include abnormal consistency, nodularity or irregularity of the testis. The abdomen and lymph nodes are palpated to seek evidence of metastasis and tumour type is identified after orchiectomy. Testicular biopsy is not recommended because it may cause dissemination of the tumour and increase the risk of local recurrence. Primary testicular cancer can be assessed rapidly and accurately by scrotal ultrasonography. Tumour markers, alpha (α)-fetoprotein and beta (β)-subunit gonadotropin, and lactate dehydrogenase are usually elevated. Chest X-ray films, lymphangiograms, intravenous pyelograms, abdominal ultrasound or CT scan and measurement of serum markers are used in clinical staging of the disease.

Besides surgery, treatment involves radiation and chemotherapy singly or in combination. Factors influencing the prognosis include histology of the tumour stage of the disease and selection of appropriate treatment. Most patients treated for cancer of the testis can expect a normal life span; some have persistent paraesthesia (tingling or numbness over the skin) or infertility. Almost 90% of disease-related deaths occur in the first 2 years after cessation of therapy. A person who is disease-free after 3 years is considered to be cured. Orchiectomy does not affect sexual function.

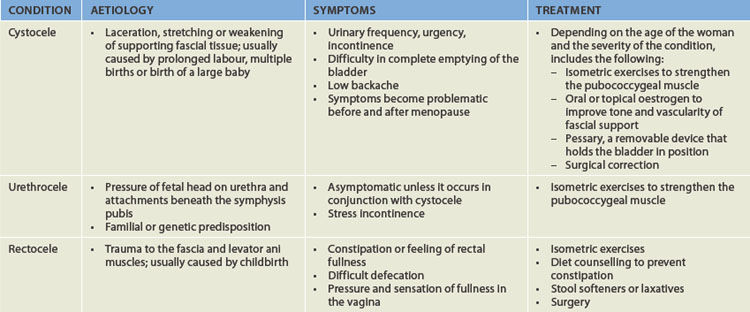

DISORDERS OF THE FEMALE REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM

Benign growths and proliferative conditions

Benign ovarian cysts

Benign (non-cancerous) cysts of the ovary may occur at any time of life but are most common during the reproductive years and, in particular, at the extremes of those years. An increase in benign ovarian cysts occurs when hormonal imbalances are more common, around puberty and menopause. Two common causes of benign ovarian enlargement in ovulating women are follicular cysts and corpus luteum cysts. These are called functional cysts because they are caused by variations of normal physiological events. Follicular and corpus luteum cysts are usually unilateral and are produced when a follicle or a number of follicles are stimulated but no dominant follicle develops and completes the maturity process to ovulation. Benign cysts of the ovary are typically 5–6 cm in diameter but can grow as large as 8–10 cm.

Follicular cysts can be caused by a transient condition in which the dominant follicle fails to rupture or one or more of the non-dominant follicles fail to regress. This disturbance is not well understood. It may be that the hypothalamus does not receive or send a message strong enough to increase follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels to the degree necessary to develop or mature a dominant follicle. Clinical symptoms of follicular cysts or even a single cyst are pelvic pain, a sensation of feeling bloated or irregular menses. After several subsequent cycles in which hormone levels once again follow a regular cycle and progesterone levels are restored, cysts are usually absorbed or will regress. Follicular cysts can be random or recurrent events.

Corpus luteum cysts can develop due to an intracystic haemorrhage that occurs in the vascularisation stage; the affected cyst then consists of blood. In normal cycles, the vascularisation is replaced by a clear fluid that accumulates in the cavity of the corpus luteum. Corpus luteum cysts are less common than follicular cysts, but luteal cysts typically cause more symptoms, particularly if they rupture. Manifestations include dull pelvic pain and amenorrhoea (absence of menstruation) or delayed menstruation, followed by irregular or heavier-than-normal bleeding. Rupture can cause massive bleeding with excruciating pain and can require immediate surgery. Corpus luteum cysts usually regress spontaneously in non-pregnant women. The combined contraceptive pill may be used to prevent cysts from forming as the contraceptive prevents the development of the follicles.

Endometrial polyps

An endometrial polyp is a mass of endometrial tissue containing a variable amount of glands, stroma and blood vessels. Endometrial polyps are usually found singly at the fundus but about 20% are multiple or originate from lower in the uterine body or upper endocervix and contain mixed epithelium. Most polyps are asymptomatic. However, some endometrial polyps cause intermenstrual bleeding or even excessive menstrual bleeding. Although polyps most often develop in women between the ages of 40 and 60 years, they can occur at all ages.66

Leiomyomas

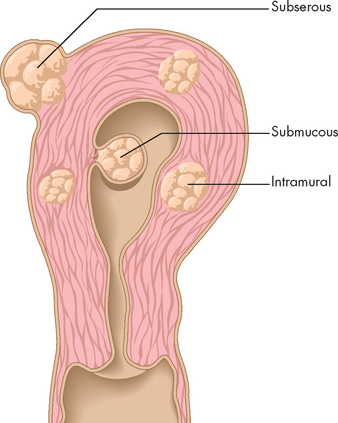

Leiomyomas (or uterine fibroids) are benign tumours that develop from smooth muscle cells in the myometrium. They are the most common benign tumours of the uterus and usually occur in multiples in the fundus; the majority remain small and asymptomatic. Prevalence increases in women aged 30–50 years but decreases with menopause.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The cause of uterine leiomyomas is unknown, although their size appears to be related to hormonal fluctuations (particularly oestrogen). Uterine leiomyomas are not seen before menarche and those that develop during the reproductive years generally shrink after menopause. Leiomyomas are classified as subserous, submucous or intramural, according to their location within the various layers of the uterine wall (see Figure 32-9). Degenerative changes, such as ulceration and necrosis, may occur when the leiomyoma outgrows its blood supply and are therefore more common in larger tumours.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Although leiomyomas rarely present problems, they occasionally cause cramping, excessive bleeding and symptoms related to pressure on nearby structures. Because the tumour is relatively slow growing, enabling adjacent structures to adapt to pressure, symptoms of abdominal pressure develop slowly. Pressure on the bladder may contribute to urinary frequency, urgency and dysuria. If the tumour is large enough, pressure on the lower colon may lead to constipation and abdominal heaviness.

EVALUATION AND TREATMENT

Uterine leiomyomas are suspected when manual examination finds irregular, non-tender nodes on the uterus. Scanning, using MRI, confirms the diagnosis. Treatment depends on symptoms, tumour size and the individual’s age, reproductive status and overall health. Most leiomyomas can be treated conservatively by shrinking the tumour using pharmacological agents, such as the gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist, progesterone, or oral contraceptives. Mifepristone, an antiprogesterone, may also be useful as a conservative treatment.

Adenomyosis

In this condition endometrial tissue (the inner lining of the uterus) is present within the myometrium (the thick, muscular layer of the uterus). Some endometrial tissue is therefore ectopic (out of place), possibly as a result of uterine trauma. Adenomyosis commonly develops during the late reproductive years, with the highest incidence among women in their 40s and women taking tamoxifen (used to treat hormone-positive breast cancer). It may be asymptomatic or it may be associated with abnormal menstrual bleeding, dysmenorrhoea, uterine enlargement and uterine tenderness during menstruation. Secondary dysmenorrhoea becomes increasingly severe as the disease progresses. On examination, the uterus is enlarged, globular and most tender just before or after menstruation. Diagnosis is confirmed with ultrasonography or MRI. Treatment, when necessary, includes surgical resection of localised areas of adenomyosis or, if severe, hysterectomy. Adenomyosis is typically unresponsive to hormone treatment.

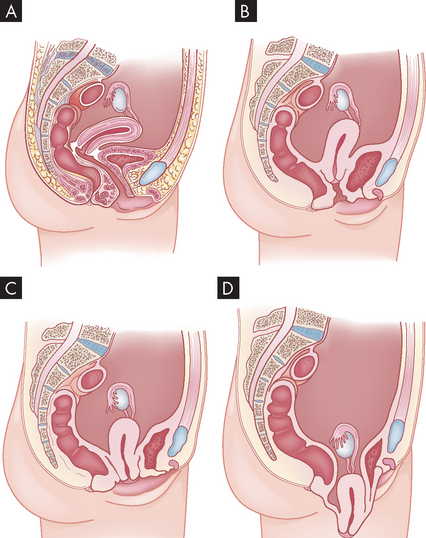

Endometriosis

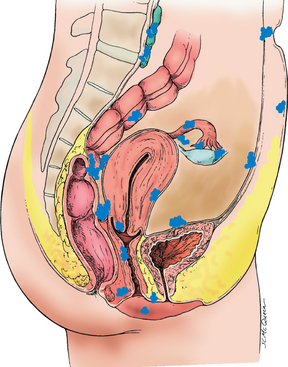

Endometriosis is a condition in which endometrial-like cells appear and flourish in areas outside the uterine cavity (see Figure 32-10). Like normal endometrial tissue, the ectopic endometrial implants respond to the hormonal fluctuations of the menstrual cycle. Thus they behave like normal endometrium and proliferate, break down and bleed in conjunction with the normal menstrual cycle. The bleeding causes inflammation and pain in surrounding tissues. The inflammation may lead to fibrosis, scarring and adhesions. Endometriosis affects 10–15% of reproductive-age women and 50% of infertile women.67

FIGURE 32-10 Common pelvic sites of endometriosis.

Source: Katz VL et al. Comprehensive gynecology, 5th edn. St Louis: Mosby; 2007.

The clinical manifestations of endometriosis vary in frequency and severity and include primarily infertility and pain, dysmenorrhoea, dyschezia (pain on defecation), dyspareunia (pain on intercourse) and, less commonly, constipation and abnormal vaginal bleeding. Dyschezia, a hallmark symptom of endometriosis, occurs with bleeding of ectopic endometrium in the rectosigmoid musculature and subsequent fibrosis. Medical therapies for endometriosis include suppression of ovulation with various medications.

Up to one-third of individuals with endometriosis are infertile, presumably because of a combination of the following:

Polycystic ovary syndrome

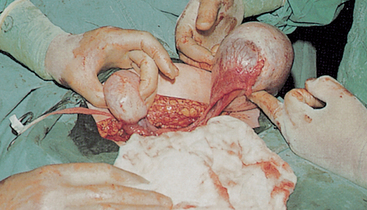

Polycystic ovary syndrome is a condition in which excessive androgen production is triggered by inappropriate secretion of gonadotropins (see Chapter 31 for normal cycling of gonadotropins). It is the most common endocrine disturbance affecting women. This hormonal imbalance prevents ovulation and causes enlargement and cyst formation in the ovaries (Figure 32-11), excessive endometrial proliferation and often hirsutism (excessive female hair growth in areas where hair growth is minimal or absent). It is defined as the presence of any two of the following:

FIGURE 32-11 Polycystic ovary. Both ovaries shown are enlarged with multiple cysts.

Source: Symonds EM, Macpherson MBA. Color atlas of obstetrics and gynecology. London: Mosby; 1994.

Polycystic ovary syndrome affects an estimated 400,000 Australian women, approximately 5–10% of the reproductive age group.68 Eighty per cent of women with normal ovaries experience one or more symptoms of polycystic ovary syndrome and the signs and symptoms of women with polycystic ovary syndrome may change over time.

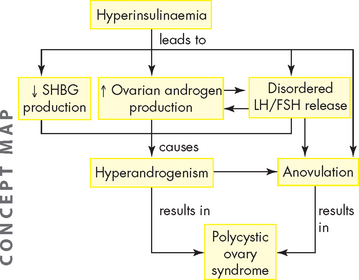

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Although common, polycystic ovary syndrome remains poorly understood with no clear aetiology. While it has been classified as an ovarian disease, it is associated with other long-term health issues, including hypertension, dyslipidaemia and hyperinsulinaemia.69 Hyperinsulinaemia plays a key role in androgen excess, anovulation and pathogenesis of polycystic ovary syndrome.70 Insulin stimulates androgen secretion by the ovarian stroma and reduces serum sex hormone-binding globulin directly and independently. The net effect is an increase in free testosterone levels. Excessive androgens affect follicular growth and insulin affects follicular decline by suppressing apoptosis and enabling follicles, which would normally disintegrate, to survive (see Figure 32-12). Furthermore, there seems to be a genetic ovarian defect in polycystic ovary syndrome that makes the ovary either more susceptible to or at least sensitive to insulin’s stimulation of androgen production in the ovary.71

FIGURE 32-12 Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinaemia in polycystic ovary syndrome.

See text for explanation. SHBG = sex hormone-binding globulin; LH = luteinising hormone; FSH = follicle-stimulating hormone.

Inappropriate gonadotropin secretion triggers the beginning of a vicious cycle that perpetuates anovulation. Typically, levels of FSH are low or below normal and the LH level is elevated. Persistent LH elevation causes an increase in androgens. Androgens are converted to oestrogen in peripheral tissues and increased testosterone levels cause a significant reduction (approximately 50%) in sex hormone-binding globulin, which, in turn, causes increased levels of free oestradiol. Elevated oestrogen levels trigger a positive-feedback response in LH and a negative-feedback response in FSH. Because FSH levels are not totally depressed, new follicular growth is continuously stimulated, but not to full maturation and ovulation (see Figure 32-12).71

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Clinical manifestations of polycystic ovary syndrome are related to anovulation and elevated testosterone levels and include dysfunctional bleeding or amenorrhoea, hirsutism and infertility (see Box 32-3). Approximately 38% of women with polycystic ovary syndrome are obese and 20% are asymptomatic. In addition, 30% of women with polycystic ovary syndrome will develop diabetes by the age of 30 years. Other pathological conditions resulting from polycystic ovary syndrome include type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease and endometrial carcinoma. Pregnant women with polycystic ovary syndrome may be at increased risk for glucose intolerance.

Box 32-3 CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF POLYCYSTIC OVARY SYNDROME

Presenting signs and symptoms (percentage of women affected)

Hormonal disturbances

Increased insulin (independent of obesity)

Increased androgens (testosterone androstenedione)

Increased leptin, especially in obesity (independent of insulin)

Possible decreased oestrogen receptors (intraovarian and along hypothalamic-pituitary axis)

EVALUATION AND TREATMENT

Diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome is based on evidence of androgen excess, chronic anovulation and inappropriate gonadotropin secretion. Treatment with insulin sensitisers seems to increase fertility while decreasing predisposition to type 2 diabetes. Adding an anti-androgen agent may enhance results. Hormonal contraception may be used to suppress androgen production and reduce endometrial hyperplasia.

Hormonal and menstrual alterations

Dysmenorrhoea

Primary dysmenorrhoea is painful menstruation associated with the release of prostaglandins in ovulatory cycles but not with pelvic disease. Between 50% and 75% of women aged 15–25 years are affected — some (up to 15%)72 are affected severely enough to cause missed work or school. Primary dysmenorrhoea begins with the onset of ovulatory cycles. The incidence steadily rises, peaks in women in their mid-20s and decreases slowly thereafter.

Primary dysmenorrhoea results from excessive prostaglandin F production by the secretory endometrium. Prostaglandins are lipid-based hormones that can increase contractions of the myometrium and constrict endometrial blood vessels. Reduced blood flow to the endometrium causes ischaemia resulting in the shedding of the endometrium. In addition, prostaglandins and prostaglandin metabolites can cause gastrointestinal complaints, headache and syncope (fainting).

The chief symptom of dysmenorrhoea is pelvic pain associated with the onset of menses. The severity is directly related to the length and amount of menstrual flow, and pain often radiates into the groin and may be accompanied by backache, anorexia, vomiting, diarrhoea, syncope and headache. Usually, the discomfort begins shortly before the onset of menstruation and rarely persists beyond the second day. Dysmenorrhoea may be relieved with hormonal contraceptives, which stop ovulation and prevent growth of the endometrium, thereby decreasing prostaglandin synthesis and myometrial contractility. Prostaglandin inhibitors work in a majority of women with primary dysmenorrhoea and should be taken before or at the onset of bleeding or cramping. Regular exercise seems to prevent or reduce symptoms. Other comfort measures include local application of heat, massage or relaxation techniques. Orgasm may relieve or worsen symptoms.

Secondary dysmenorrhoea is related to pelvic pathology, manifests later in the reproductive years and may occur any time in the menstrual cycle. Secondary dysmenorrhoea results from disorders such as endometriosis, pelvic adhesions, pelvic inflammatory disease, uterine fibroids or adenomyosis.

Primary amenorrhoea

Amenorrhoea means lack of menstruation from any cause. Primary amenorrhoea, however, is defined as either the failure of menarche and the absence of menstruation by age 14 years with no development of secondary sex characteristics, or the absence of menstruation by age 16 years regardless of the presence of secondary sex characteristics. Causes include congenital defects of gonadotropic hormone production, genetic disorders (such as Turner’s syndrome), congenital or acquired central nervous system defects (e.g. hydrocephalus, trauma, infection and tumours) and congenital malformations of the reproductive system (e.g. absence of vagina or uterus). A major cause of primary amenorrhoea is the failure of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis (see Chapter 31), as a result of which the ovaries do not receive the hormonal signals (FSH and LH) that normally initiate menarche. Essentially, any defect in the development of the gonads or their ability to respond to the gonadotropins FSH and LH will result in primary amenorrhoea.

Diagnosis of primary amenorrhoea is based on the history and physical examination to investigate:

Treatment involves correction of any underlying disorders and hormone replacement therapy to induce the development of secondary sex characteristics. Although surgical alteration of the genitalia may be undertaken to correct abnormalities, it should be postponed until the individual can make a truly informed decision.

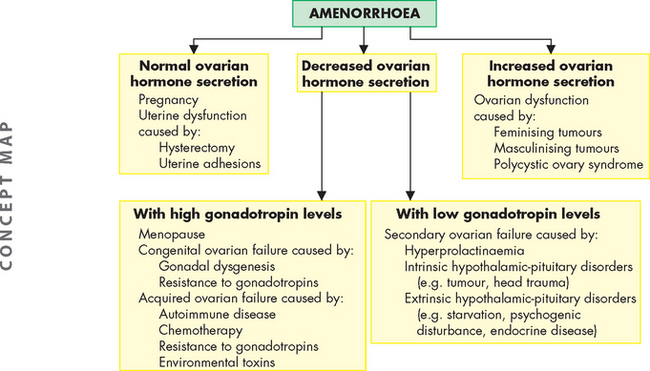

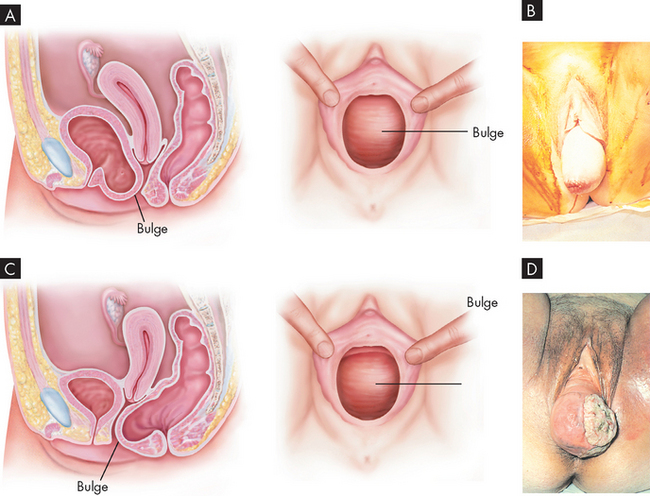

Secondary amenorrhoea

Secondary amenorrhoea is the absence of menstruation for a time equivalent to 3 or more cycles or 6 months in women who have previously menstruated. Many disorders and physiological conditions are associated with secondary amenorrhoea. Secondary amenorrhoea is normal during early adolescence, pregnancy, lactation and in older women approaching menopause. Pregnancy is the most common cause of secondary amenorrhoea and must be ruled out before any further evaluation. The pathophysiology of secondary amenorrhoea is summarised in Figure 32-13.

The major manifestation of secondary amenorrhoea is the absence of menses. Depending on the underlying cause of the amenorrhoea, infertility, vasomotor flushes (dilation of blood vessels leading to ‘hot flushes’), vaginal atrophy, acne and hirsutism may also be present. Diagnosis involves identifying underlying hormonal or anatomical alterations. Depending on the cause of the amenorrhoea, treatment may involve hormone replacement therapy or a corrective procedure, such as surgical removal of pituitary tumours.

Abnormal uterine bleeding

The most common cause of abnormal uterine bleeding is failure to ovulate related to age or pathology of the endocrine (hormone) function. Common causes of abnormal bleeding based on age group and frequency are presented in Table 32-3.

Table 32-3 COMMON CAUSES OF ABNORMAL VAGINAL/GENITAL BLEEDING

| AGE GROUP | CAUSE |

|---|---|

| Prepubescence | |

| Adolescence | |

| Reproductive years | |

| Premenopause | |

| Postmenopause | Malignancy |

Dysfunctional uterine bleeding is abnormal uterine bleeding resulting from a disturbance of the menstrual cycle, usually anovulation. Although dysfunctional uterine bleeding may occur at any time during the reproductive years, it is most likely to affect women at the extremes of the reproductive years.

Abnormal bleeding in ovulatory cycles is less common and mechanisms underlying this bleeding are unclear. Excessive fibrinolytic activity and changes in prostaglandin production may be implicated. Infection or structural abnormalities may also be present.

Dysfunctional uterine bleeding is characterised by unpredictable and variable bleeding in terms of amount and duration. When a woman is close to menopause, dysfunctional bleeding may involve flooding and the passing of large clots.73 Heavy bleeding may be preceded by episodes of amenorrhoea and be perceived by individuals as a miscarriage. Dysfunctional uterine bleeding is the diagnosis when other conditions that could cause abnormal bleeding are eliminated. Goals of therapy are to control bleeding, prevent hyperplasia, prevent or treat anaemia and treat concurrent endocrine problems if present. The usual therapy is treatment with hormones.

Premenstrual syndrome