CHAPTER 24 Effects of Age and Systemic Health on Endodontics

Dental service requirements are determined by four demographic and epidemiologic factors:

These factors are changing as a result of the aging of the population.

An Aging Society

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, America’s population aged 65 years or older grew by 82% between 1965 and 1995.75 Between 1980 and 1995, this same population grew by 28% to a historic high of 33.5 million people. The oldest old are defined as those who are at least 85 years of age. This group is the fastest-growing segment of America’s senior citizen population. The number of persons 85 years and older has more than doubled since 1965 and has grown by 40% since 1980.

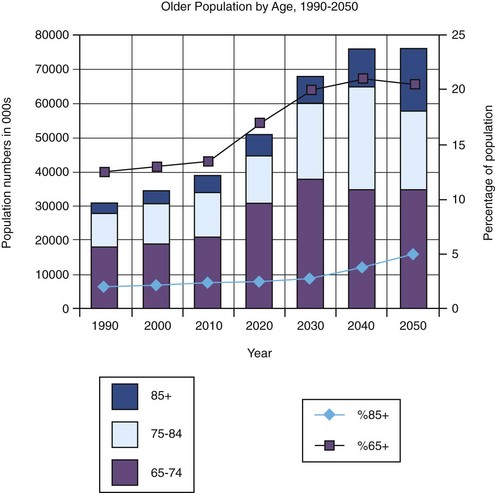

The 75 million people born in the United States between 1946 and 1964 constitute the baby boom generation. In 1994, baby boomers represented nearly one third of the U.S. population. Soon these people will enter the 65-years-and-older category. As the baby boomers begin to age, the United States will see an unparalleled increase in the absolute number of older persons.12 Although one in eight Americans was 65 years of age or older in 1994, in a little more than 30 years, about one in five is expected to be in this group (Fig. 24-1).3

FIG. 24-1 Projected percentage growth rates of U.S. adults age 65+ years and 85+ years from 1990 to 2050.

(From U.S. Bureau of the Census, Population Division Population Projections Program. Available at: http://www.census.gov/ Accessed August 2009.)

Information available from the U.S. Census Bureau and the National Institute on Aging indicates that America’s older population is unevenly distributed among geographic locations. The most populous states have the largest number of older adults; Florida and Midwestern states currently have the highest proportions of older adults. Florida was the only state where the population of older adults was greater than 16% of its population in 1993; however, it is predicted that 32 states will fall in this category by 2020.51

Increased longevity of the dentition with expanding fields of advanced restorative procedures and periodontology lends support that dentistry will see a substantial growth in the number of older patients.16 Until 1983, persons aged 65 years and older made an average of 1.5 dental visits annually, a lower utilization rate than that of any other age group.78 Between 1983 and 1986, a 29% increase in visits by those 65 years and older was noted by the National Health Survey.77 According to this survey, older adults currently make more visits per year on average than those in the “all ages combined” category. The percentage of office visits, services provided, and patient expenditures attributed to patients 65 years of age or older exceeded the percentage of the population in that age group.44 In the future, clinicians will routinely serve a growing number of older persons, who will account for one third to two thirds of their workload.42,43,45

The growth of the population aged 65 years and older has affected every aspect of U.S. society, presenting challenges as well as opportunities to policymakers, families, businesses, and health care providers.51 Future dental services (including root canal procedures) for older patients are anticipated to be of two general types:

The latter group will require care from clinicians who have advanced training in geriatric dentistry. This age group is being targeted in dental education programs and advanced training through improved curriculum, research, and publications on aging. The National Institute on Aging stated that all dental professionals should receive education concerning treatment of older adults as part of basic professional education.14,49

This chapter discusses the effect of aging on the diagnosis of pulpal and periapical disease and successful root canal treatment. The quality of life for older patients can be significantly improved by saving teeth through endodontic treatment and can have a large and impressive value to overall dental, physical, and mental health.

With age, the simple pleasure of being able to eat what one wishes often becomes an issue, as does the increased need for proper diet and nourishment. Every tooth may be strategic, and old age is no time to be forced to replace sound teeth with removable appliances or dentures. Age is a factor in reduced stability and retention of removable partial dentures.30 Consultation with older patients should help them overcome what may be a very limited knowledge of root canal treatment and lack of appreciation for regular dental care. Well-meaning friends and spouses who contend that their dentures are as good or better than their natural teeth may have had a lifetime of poor dental experiences or have forgotten what it is like to enjoy natural dentition.

Negative social attitudes toward older adults tend to carry over into their care. Older patients are in danger of being dismissed as hopeless or not worth the effort. At times, clinicians shy away from providing care for seniors because of the perceived difficulty or cost of certain treatment procedures or because of complicated medical conditions. Clinicians sometimes consider older patients less able to pay for treatment because of their age and appearance. However, most older adults engage in normal activities and can recognize and afford the value of good dentistry.7

Most older patients have had active, productive lives; they are very interested in maintaining their dignity and do not consider themselves a bad investment. Tooth loss is often associated with the prospect of aging and loss of vitality.21 As with any age group, older patients must be considered as individuals. This may prove difficult in the face of the tendency of many health care professionals to assign any person older than 65 years to the classification geriatric and to stereotype patients (e.g., confusion, dementia, poor treatment response). Each older adult patient comes with a unique psychologic and social life history and with a set of values, needs, and resources unlike those of any other patient the provider will see. Most seniors are more concerned with maintaining control of their lives than they are about being old.58 Clinicians’ perception of the effects of aging on diagnosis and treatment of pulp and periradicular disease is also improving along with the rate at which older patients need and seek specialty care.27

Because the primary function of teeth is mastication, it is presumed that loss of teeth leads to detrimental food changes and reduction in health.31 However, this may not be the driving force when seniors are seeking treatment. Many times, social issues are the motivation for a senior to visit a clinician. After suggesting a mandibular anterior tooth extraction to a 93-year-old man, one clinician was told, “I can’t, Doctor. You see, I go dancing every Saturday night, and I need that tooth. I can’t look like that.” The majority of people older than 60 years who still have their own natural anterior teeth would not wish for a change in appearance if they needed prosthodontic reconstruction.28

Clinicians should not presume that they know what is best for senior patients or what they can afford without the patient’s full awareness. The needs, expectations, desires, and demands of older people may exceed those of any age group, and the gratitude shown by older patients is among the most satisfying of professional experiences.

The desire for root canal treatment among aging patients has increased considerably in recent years. Older patients are aware that treatment can be performed comfortably and that age is not a factor in predicting success.5,69,71 Obtaining informed consent also requires that root canal treatment be offered as a favorable alternative to the trauma of extraction and the cost of replacement. The distribution of specialists and the improved endodontic training of all clinicians have broadened the availability of most endodontic procedures to everyone, regardless of age. Expanded dental insurance benefits for retirees and a heightened awareness of the benefits of saving teeth have encouraged many older patients to seek endodontia rather than extraction.80 People with private dental insurance are more likely to visit a clinician. There is a trend toward less insurance in most demographic groups except the elderly, who also enjoyed benefits during their working years.82

This chapter compares the typical geriatric patient’s endodontic needs with those of the general population. (Pulp changes attributed to age are discussed in Chapters 12 and 13; their effects on clinical treatment are also discussed in this chapter.)

Medical History

It is important to focus on those factors that will truly indicate the risks undertaken in treating the older patient. Clinicians must recognize that the biologic or functional age of an individual is far more important than chronologic age. A medical history should be taken before the patient is brought into the treatment room, and a standardized form (see Chapter 1, Fig. 1-2) should be used to identify any disease or therapy that would alter treatment or its outcome. In general, aging causes dramatic changes to the cardiovascular, respiratory, and central nervous systems that result in most drug therapy needs. However, the decline in renal and liver function in older patients should also be considered when predicting behavior and interaction of drugs (e.g., anesthetics, analgesics, antibiotics) that may be used in dental treatment.

The review of the patient’s medical history is the first opportunity for the clinician to talk with the patient. The time and consideration taken at the outset will set the tone for the entire treatment process. This first impression should reflect a warm, caring clinician who is highly trained and able to help patients with complex treatments. Some older patients may need assistance in filling out the forms and may not be fully aware of their conditions or history. Some patients may withhold their date of birth to conceal their age for reasons of vanity or even fear of ageism. Some may not fill out current medications because they think it would be unnecessary information for the clinician to know. Vision deficits caused by outdated glasses or cataracts can adversely affect a patient’s ability to read the small print on many history forms. Consultation with the patient’s family, guardian, or physician may be necessary to complete the history; however, the clinician is ultimately responsible for the treatment.

An updated history, including information on compliance with any prescribed treatment and sensitivity to medications, must be obtained at each visit and reviewed. The elderly usually take more drugs, prescription and nonprescription, than the general adult population, and drug interactions and adverse drug reactions are more likely to result from polypharmacy.29 It is very important that the clinician take a careful history and update it at every visit.46 The Physicians’ Desk Reference should be consulted and any precaution or side effect of medication noted. It is available online at http://www.pdr.net/ and several other websites have been developed specifically for drug interactions.

Although geriatric patients are usually knowledgeable about their medical history, some may not understand the implications of their medical conditions in relation to dentistry or may be reluctant to let the clinician into their confidence. Their perceptions of their illnesses may not be accurate, so any clue to a patient’s conditions should be investigated.

Symptoms of undiagnosed illnesses may present the clinician with a screening opportunity that can disclose a condition that might otherwise go untreated or lead to an emergency. Management of medical emergencies in the dental office is best directed toward prevention rather than treatment. Oral and pharyngeal cancers are primarily diagnosed in the elderly, and the prognosis is poor.76

Few families are without at least one member whose life has been extended as a result of medical progress. A great number have had diseases or disabilities controlled with therapies that may alter the clinician’s case selection. Root canal treatment is certainly far less traumatic in the extremes of age or health than is extraction.

Chief Complaint

Most patients who are experiencing dental pain have a pulpal or periapical problem that requires root canal treatment or extraction. Dental needs are often manifested initially in the form of a complaint, which usually contains the information necessary to make a diagnosis. The diagnostic process is directed toward determining the vitality of the pulp, whether pulpal or periapical disease is present, and which tooth is the source (see Chapter 1).

The clinician should, without leading, allow the patient to explain the problem in his or her own way. This gives the examiner an opportunity to observe the patient’s level of dental knowledge and ability to communicate. Visual and auditory handicaps may become evident at this time.

Patiently encouraging the patient to talk about problems may lead into areas of only peripheral interest to the clinician, but it establishes a needed rapport and demonstrates sincere interest. A patient may exhibit some feelings of distrust if there is a history of failed treatments or if well-meaning, denture-wearing friends or relatives have claimed normal function and freedom from the need for dental treatment. The effect of the “focal infection” theory is still evident when other aches and pains cannot be adequately explained and loss of teeth is accepted as inevitable. The best patients are those who have already had successful endodontic treatment. Older patients are more likely to have already had root canal treatment and have a more realistic perception about treatment comfort.

Most geriatric patients do not complain readily about signs or symptoms of pulpal and periapical disease and may consider them to be minor compared with other health concerns and discomfort. A disease process usually arises as an acute problem in children but assumes a more chronic or less dramatic form in the older adult. The mere presence of teeth indicates proper maintenance or resistance to disease. A lifetime of experiencing pains puts a different perspective on interpreting dental pain.

Pain associated with vital pulps (i.e., referred pain; pain caused by heat, cold, or sweets) seems to be reduced with age, and severity seems to diminish over time. Heat sensitivity that occurs as the only symptom suggests a reduced pulp volume, such as that occurring in older pulps.33 Pulpal healing capacity is also reduced, and necrosis may occur quickly after microbial invasion, again with reduced symptoms.

Although complaints are fewer, they are usually more conclusive evidence of disease. The complaint should isolate the problem sufficiently to allow the clinician to take a periapical radiograph before proceeding. Studying radiographs before an examination can prejudice rather than focus attention; accordingly, they should be reviewed after the clinical examination has been completed.

Dental History

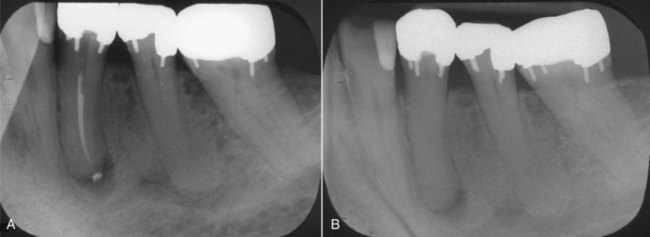

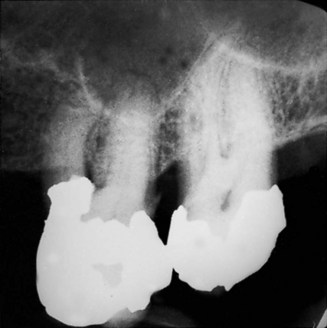

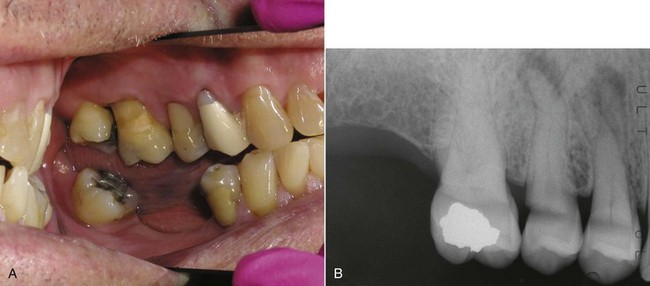

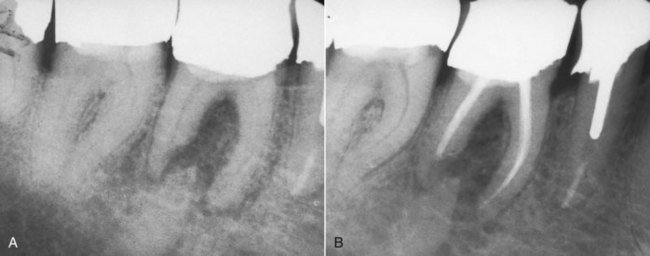

The clinician should search patients’ records and explore their memories to determine the history of involved teeth or surrounding areas. The history may be as obvious as a recent pulp exposure and restoration, or it may be as subtle as a routine crown preparation 15 or 20 years ago. Any history of pain before or after treatments may establish the beginning of a degenerative process. Subclinical injuries caused by repeated episodes of decay and its treatment may accumulate and approach a clinically significant threshold that can be later exceeded after additional routine procedures. Multiple restorations on the same tooth are common (Fig. 24-2).

FIG. 24-2 Multiple restorations on this 74-year-old patient suggest repeated episodes of caries and restorative procedures with pulpal effects that accumulated in the form of subclinical inflammation and calcification.

Recording information at the time of treatment may seem to be unnecessary “busy work,” but it could prove to be helpful in identifying the source of a complaint or disease many years later. A patient’s recall of dental treatments is usually limited to a few years, but the presence of certain materials or appliances, such as silver points, can sometimes date a procedure. Aging patients’ dental histories are rarely complete and may indicate treatment by several clinicians at different locations. These patients are likely to have outlived at least one clinician and been forced to establish a relationship with a new, younger clinician. This new clinician may find dental needs that require an updated treatment plan.

Subjective Symptoms

The examiner can pursue responses to questions about the patient’s complaint, the stimulus or irritant that causes pain, the nature of the pain, and its relationship to the stimulus or irritant. This information is most useful in determining whether the source of the pain is pulpal in origin, if the problem is reversible, and whether inflammation or infection has extended to the apical tissues. Thus the clinician can determine what types of tests are necessary to confirm findings or suspicions. (Chapter 1 gives further information.)

Diagnostic Procedures

It is important to remember that pulpal symptoms are usually chronic in older patients, and other sources of orofacial pain should be ruled out when pain is not soon localized. Much information obtained from the complaint, history, and description of subjective symptoms can be gathered in a screening interview by the clinician’s assistant or over the phone by the receptionist. The need for treatment can be established and can provide a focus for the examination.

Objective Signs

The intraoral and extraoral clinical examination provides valuable firsthand information about disease and previous treatment. The overall oral condition should not be overlooked while centering on the patient’s chief complaint, and all abnormal conditions should be recorded and investigated. Exposures to factors that contribute to oral cancers accumulate with age. Oral premalignant and malignant mucosal lesions require state-of-the-art diagnostic tools to ensure early diagnosis of these lesions.63 Furthermore, many systemic diseases may initially manifest with prodromal oral signs or symptoms.14

Missing teeth contribute to reduced functional ability (Fig. 24-3). The resultant loss of chewing efficiency leads to a higher carbohydrate diet of softer, more cariogenic foods. Increased sugar intake to compensate for loss of taste23,48 and xerostomia6 are also factors in the renewed susceptibility to decay. Saliva plays a significant role in the maintenance of oral and general health. Aging per se has no significant clinical impact on salivary secretion. The most common cause of salivary hypofunction in the elderly is medication use and is most commonly associated with dental caries and oral fungal infections.50,65

FIG. 24-3 Missing teeth and the subsequent tilt, rotation, and supraeruption of adjacent and opposing teeth contribute to reduced functional ability and increased susceptibility to caries and periodontal disease.

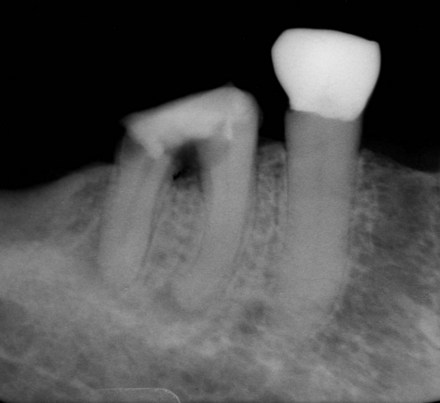

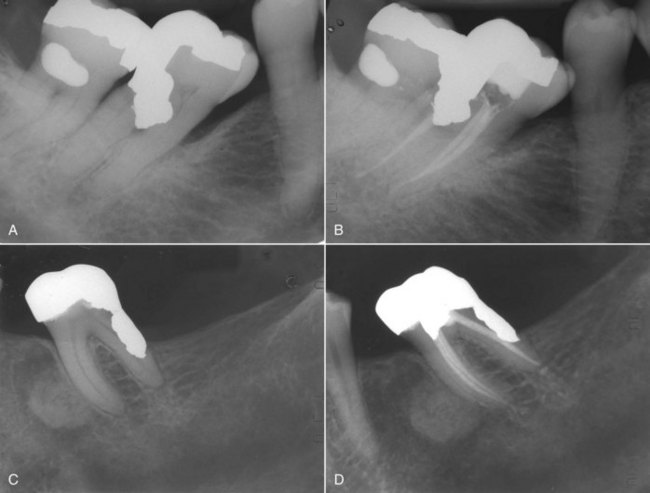

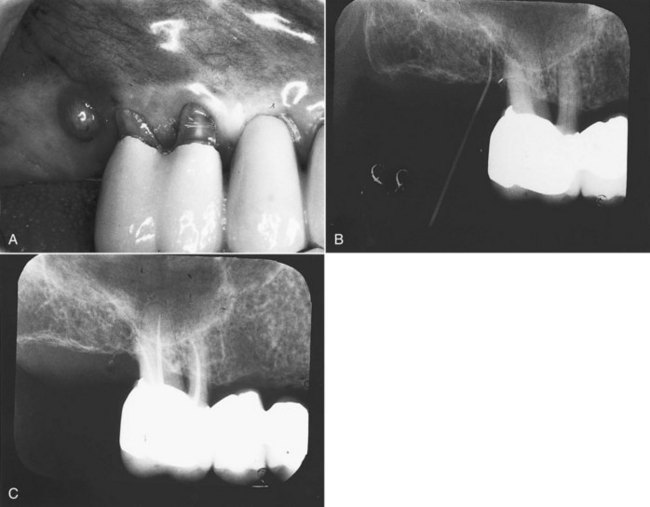

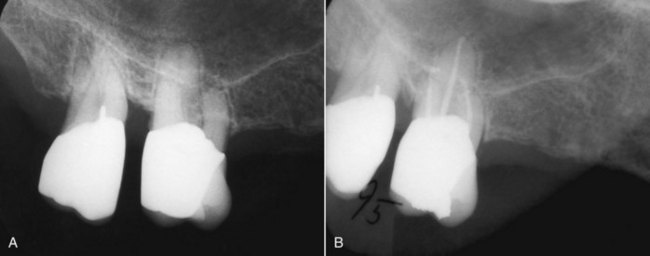

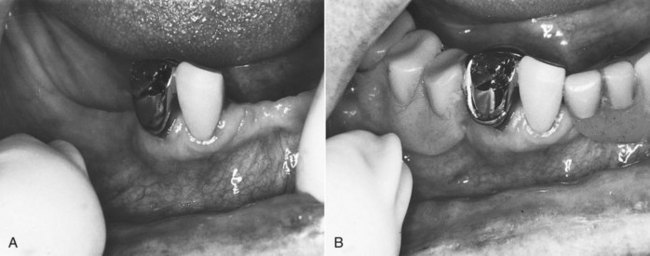

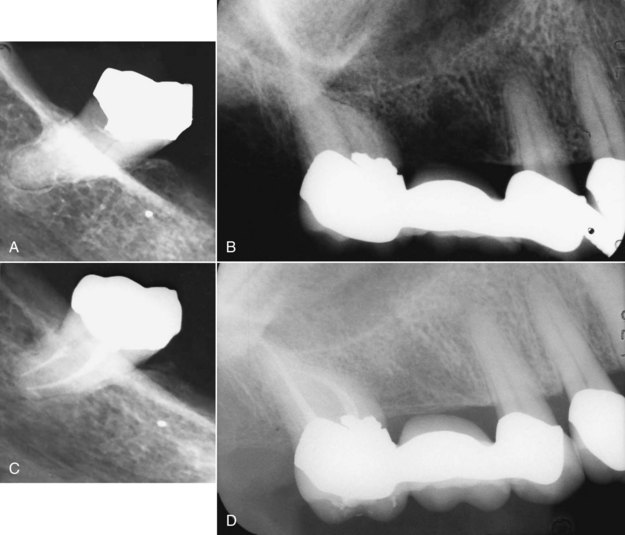

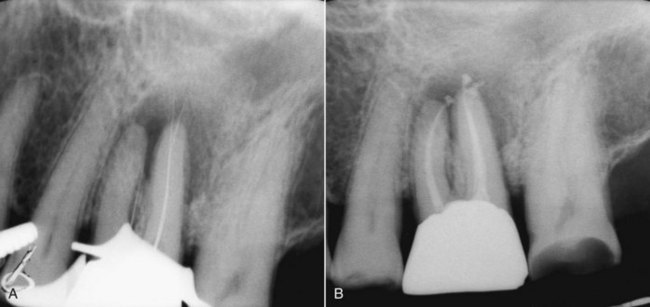

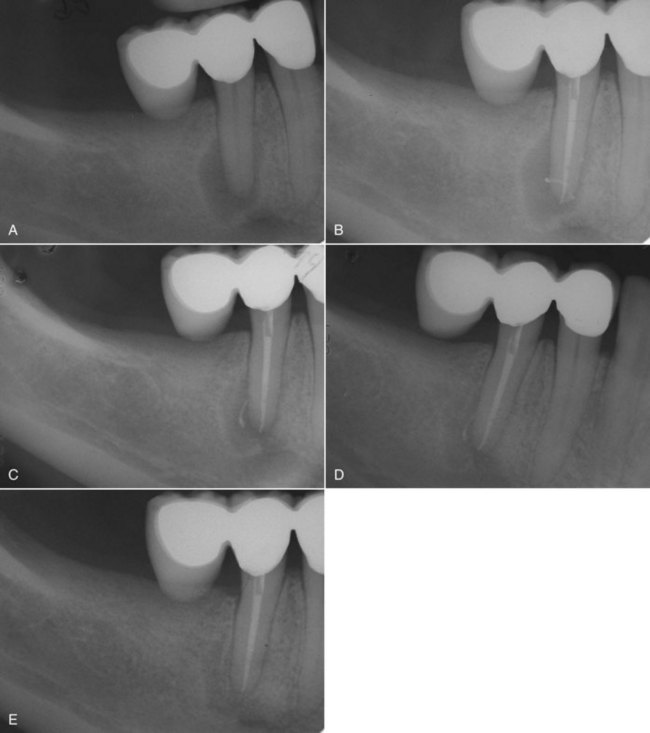

Gingival recession, which creates sensitivity and is hard to control, exposes cementum and dentin that are less resistant to decay than enamel. A clinical study of 600 patients older than age 60 years showed that 70% had root caries and 100% had some degree of gingival recession.81 The removal of root caries is irritating to the pulp and often results in pulp exposures or reparative dentin formation that affects the negotiation of the canal if root canal treatment is later needed (Fig. 24-4).20 Asymptomatic pulp exposures on one root surface of a multirooted tooth can result in the uncommon clinical situation of the presence of both vital and nonvital pulp tissue in the same tooth (Fig. 24-5).

FIG. 24-4 Gingival recession exposes cementum and dentin, which are less resistant to caries. A-B, Root caries often results in pulp exposures (C-D) that require endodontic treatment.

FIG. 24-5 A, Deep root caries that appears to involve the pulp. B, Mesial abutment for long fixed bridge. C, Canals negotiated through the buccal access cavity. D, Buccal canal access. E, Treatment is completed and access cavity permanently restored.

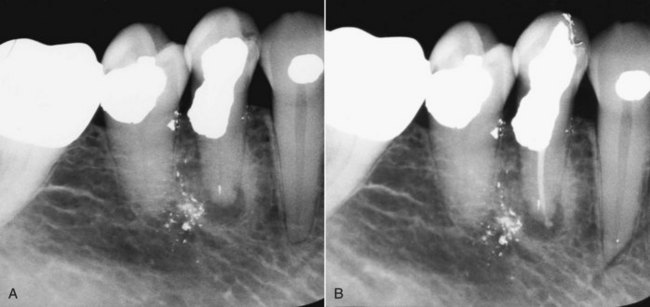

Interproximal root caries is difficult to restore, and restoration failure as a result of continued decay is common (Fig. 24-6). Although the microbiology of diseases is not substantially different in different age groups, the altered host response during aging may modify the progression of these diseases.74

FIG. 24-6 A, Attrition exposes dentin through a slow process that allows the pulp to respond with reparative dentin, but pulp exposure eventually becomes clinically evident (B).

Attrition (see Fig. 24-6), abrasion, and erosion (Fig. 24-7) also expose dentin through a slower process that allows the pulp to respond with dentinal sclerosis and reparative dentin.67 Secondary dentin formation occurs throughout life and may eventually result in almost complete pulp obliteration. In maxillary anterior teeth, the secondary dentin is formed on the lingual wall of the pulp chamber55; in molar teeth the greatest deposition occurs on the floor of the chamber.10 Although this pulp may appear to recede, small pulpal remnants can remain or leave a less calcific tract that may lead to pulp exposure.

FIG. 24-7 Gingival recession also exposes cementum and dentin that are less resistant to abrasion and erosion, which can expose pulp or require restorative procedures that could result in pulp irritation.

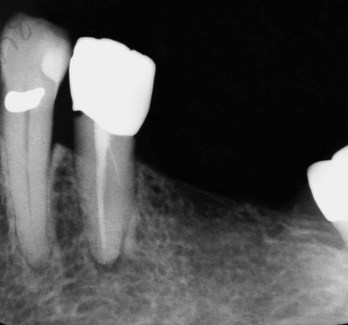

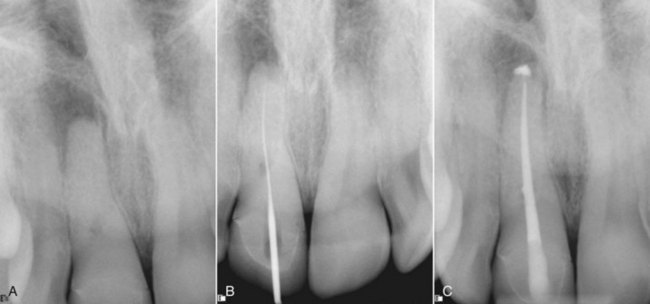

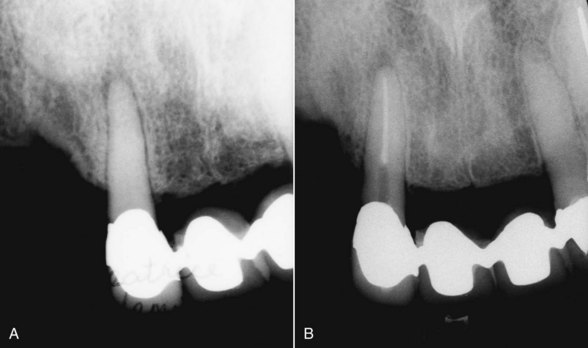

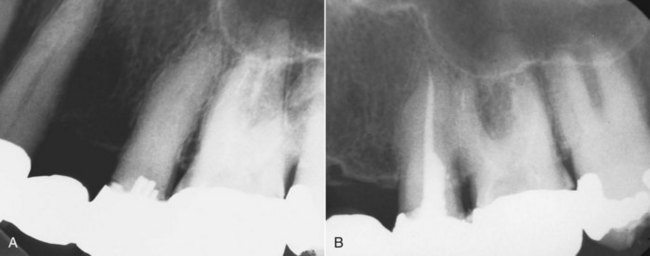

In general, canal and chamber volume is inversely proportional to age: as age increases, canal size decreases (Fig. 24-8). Reparative dentin resulting from restorative procedures, trauma, attrition, and recurrent caries also contributes to diminution of canal and chamber size. In addition, the cementodentinal junction (CDJ) moves farther from the radiographic apex with continued cementum deposition (Fig. 24-9).37 The thickness of young apical cementum60 is 100 to 200 µm and increases with age to two or three times that thickness.86

FIG. 24-8 A, In general, canal chamber volume is inversely proportional to age. As age increases, canal size decreases. The upper right central incisor exhibits a reduced canal and chamber volume. B, Negotiation using small hand files. C, Treatment completed for this calcified canal.

FIG. 24-9 Histologic image of the cementodentinal junction (CDJ) in an older tooth illustrates increased cementum deposition with age and increased distance from the apex.

(Courtesy Dr. Thomas Stein.)

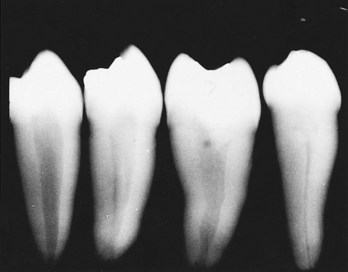

The calcification process associated with aging appears clinically to be of a more linear type than that which occurs in a younger tooth in response to caries, pulpotomy, or trauma (Fig. 24-10). Dentinal tubules become more occluded with advancing age, decreasing tubular permeability.47 Lateral and accessory canals can calcify, thus decreasing their clinical significance.

FIG. 24-10 This radiograph illustrates pulp volume changes in mandibular premolars. Left to right: a normal pulp, reparative dentin adjacent to a shallow restoration, more extensive reparative dentin adjacent to a more extensive restoration, and the overall reduced volume that occurs during aging.

The compensating bite produced by missing and tilted teeth (or attrition) can cause temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dysfunction (less common in older adults) or loss of vertical dimension. Diminished eruptive forces occur with age, reducing the amount of mesial drift and supraeruption.62 Any limitation in opening reduces available working time and the space needed for instrumentation.

The presence of multiple restorations indicates a history of repeated insults and an accumulation of irritants. Marginal leakage and microbial contamination of cavity walls are a major cause of pulpal injury.11 Violating principles of cavity design combined with the loss of resiliency that results from a reduced organic component to the dentin can increase susceptibility to cracks and cuspal fractures. In any further restorative procedures on such teeth, the clinician should consider the effect on the pulp and the effect on gaining access to and negotiating canals through such restorations if root canal therapy is indicated later.

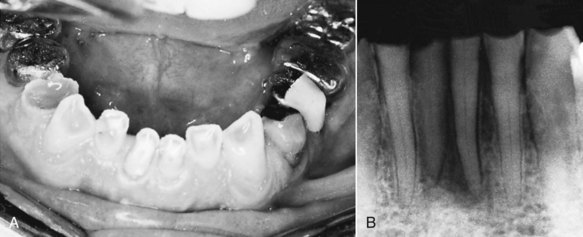

Many cracks or craze lines (see Fig. 24-7) may be evident as a result of staining, but they do not indicate dentin penetration or pulp exposure.13,32 Pulp exposures caused by cracks are less likely to present acute problems in older patients and often penetrate the sulcus to create a periodontal defect as well as a periapical one. If incomplete cracks are not detected early, the prognosis for cracked teeth in older patients is questionable (Fig. 24-11).

FIG. 24-11 A split tooth should always be considered when a nonvital pulp and chronic apical periodontitis are evident on a nonrestored tooth. The crack usually extends into the periodontium, and the prognosis is generally poor.

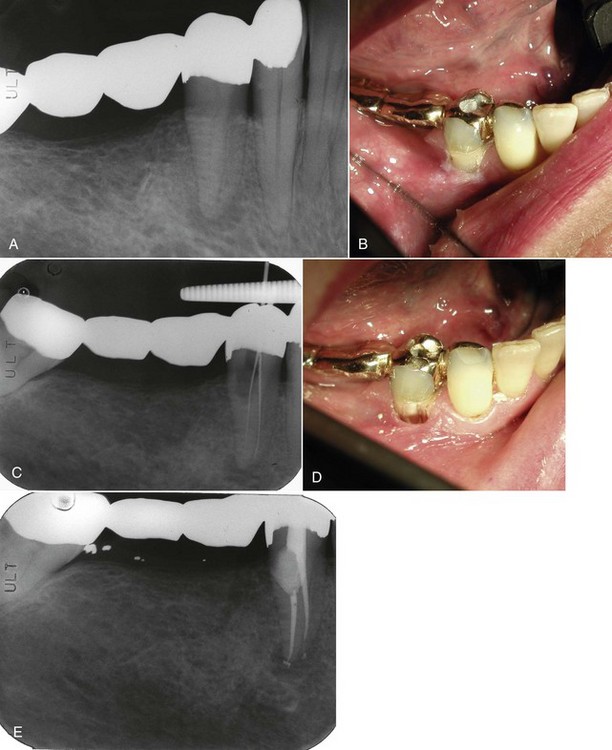

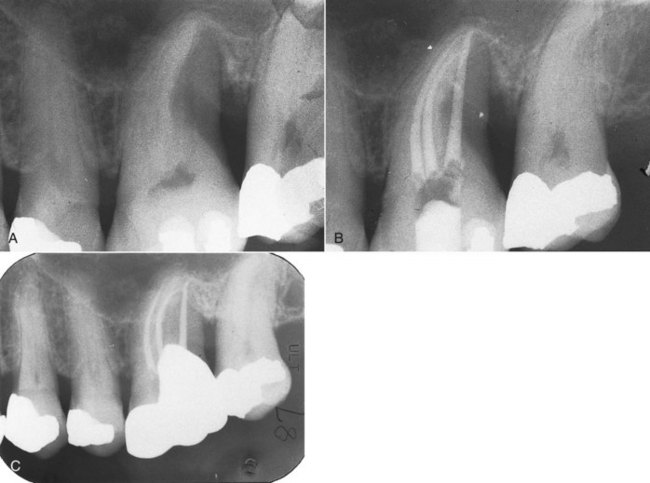

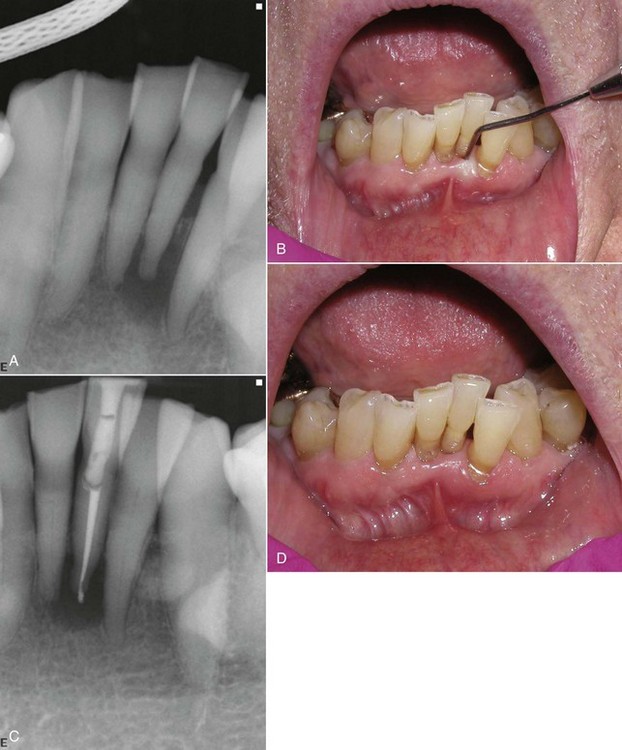

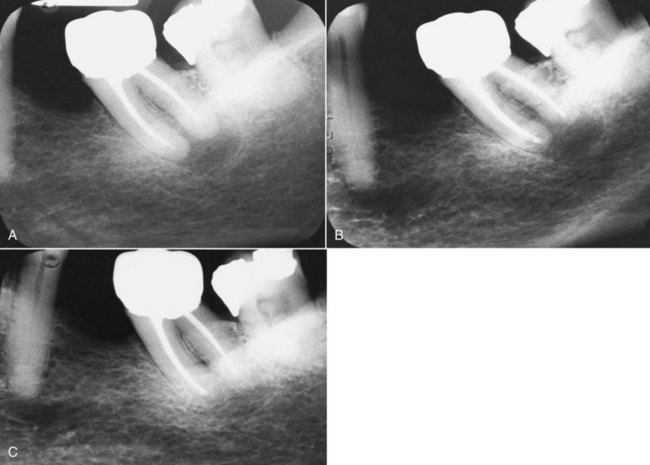

Periodontal disease may be the principal problem for dentate seniors.18 The relationship between pulpal and periodontal disease can be expected to be more significant with age. Retention of teeth alone demonstrates some resistance to periodontal disease. The increase in disease prevalence is largely attributable to an increase in the proportional size of the population who have retained their teeth.41 The periodontal tissues must be considered a pathway for sinus tracts (Fig. 24-12). Narrow, bony-walled pockets associated with nonvital pulps are usually sinus tracts, but they can be resistant to root canal therapy alone when, with time, they become chronic periodontal pockets. Patients with diabetes have increased periodontal disease in endodontically treated teeth and have a reduced likelihood of success of endodontic treatment in cases with preoperative periradicular lesions.22

FIG. 24-12 A, A periodontal pocket is probed, and a sinus tract is evident on this maxillary molar abutment. B, This could indicate pulpal or periodontal disease or both. C, Root canal treatment results in healing (D) that confirms the pulpal cause of this periradicular lesion.

Periodontal treatment can produce root sensitivity, disease, and pulp death.40 In developing a successful treatment plan, it is important to determine the effects of periodontal disease and its treatment on the pulp (Fig. 24-13). Age was not a factor in response to periodontal therapy for advanced periodontal tissue breakdown.39 The mere increase in incidence and severity of periodontal disease with age increases the need for combined therapy. The chronic nature of pulp disease demonstrated with sinus tracts can often be manifested in a periodontal pocket. Root canal treatment is commonly indicated before root amputations are performed. With age, the size and number of apical and accessory foramina are actually reduced as pathways of communication,59 as is the permeability of dentinal tubules.

FIG. 24-13 A, Unexpected root amputation on vital pulps may occur during periodontal surgery that will require root canal treatment on the remaining roots (B) and a crown with good marginal adaptation (C).

Examination of sinus tracts should include tracing with gutta-percha cones to establish the tracts’ origins (Fig. 24-14). Sinus tracts may have long clinical histories and usually indicate the presence of chronic periapical inflammation. Their disappearance after treatment is an excellent indicator of healing. The presence of a sinus tract reduces the risk of interappointment or postoperative pain, although drainage may follow canal débridement or filling.

FIG. 24-14 A, This clinical photograph shows a well-fitting abutment, gingival recession, and sinus tract. B, The radiograph illustrates origin of sinus tract demonstrated with gutta-percha point. C, Very challenging root canal treatment saves this valuable tooth.

Pulp Testing

Information collected from the patient’s complaint, history, and examination may be adequate to establish pulp vitality and direct the clinician toward the techniques that are most useful in determining which tooth or teeth are the object of the complaint. Slow and gentle testing should be done to determine pulp and periapical status and whether palliative or definitive therapy is indicated. Vitality responses must correlate with clinical and radiographic findings and be interpreted as a supplement in developing clinical judgment. (Techniques for clinical pulp-testing procedures are discussed in Chapter 1.)

Transilluminating56 and staining have been advocated as means to detect cracks, but the presence of cracks is of little significance in the absence of complaints, because most older teeth, especially molars, demonstrate some cracks. Vertically cracked teeth should always be considered when pulpal or periapical disease is observed and little or no cause for pulpal irritation can be observed clinically or on radiographs. The high magnification available with microscopes during access opening and canal exploration permits visualization of the extent of cracks in determining prognosis. Cracks that are detected while the pulp is still vital can offer a reasonable prognosis if immediately restored with full cuspal coverage. The chronic nature of any periapical pathologic condition caused by vertically cracked teeth indicates that it is longstanding, and the prognosis is questionable (even when pocket depths appear normal). Periodontal pockets associated with cracks indicate a poor prognosis.

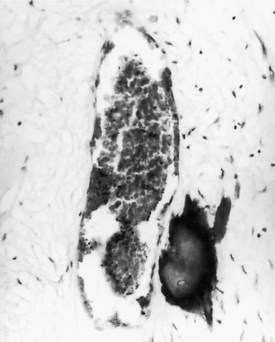

The reduced neural and vascular components of aged pulps,9 the overall reduced pulp volume, and the change in character of the ground substance66 create an environment that responds differently to both stimuli and irritants than that of younger pulps (Fig. 24-15). Arteriosclerosis, a common condition in older people, has not been shown to occur in the pulp.36

FIG. 24-15 The cellularity of older pulp tissue gradually decreases, and the odontoblasts decrease in size and number and may disappear altogether in certain areas, particularly on the pulpal floor in multirooted teeth.

Fewer nerve branches are present in older pulps. This may be due to retrogressive changes resulting from mineralization of the nerve and nerve sheath (Fig. 24-16).8 Consequently, the response to stimuli may be weaker than in the more highly innervated younger pulp.

FIG. 24-16 Fibrosis appears to occur along the pathways of degenerated vessels and may serve as foci for pulpal calcification.

No correlation exists between the degree of response to electric pulp testing and the degree of inflammation. The presence or absence of response is of limited value and must be correlated with other tests, examination findings, and radiographs. Extensive restorations, pulp recession, and excessive calcifications are limitations in both performing and interpreting results of electric and thermal pulp testing. An alternative to the electric pulp test is assessment of pulp vitality by applying a thermal stimulus to the tooth surface. The electric pulp tester, CO2 snow, and difluorodichloromethane were found to be more reliable than ethyl chloride or ice in producing a positive response.26 Attachments that reduce the amount of surface contact necessary to conduct the electric stimulus are available (SybronEndo, Orange, CA), and bridging the tip to a small area of tooth structure with an explorer has been suggested.53 Use of even this small electric stimulus in patients with pacemakers83 is not recommended; any such risk would outweigh the benefit. The same caution holds true for electrosurgical units.

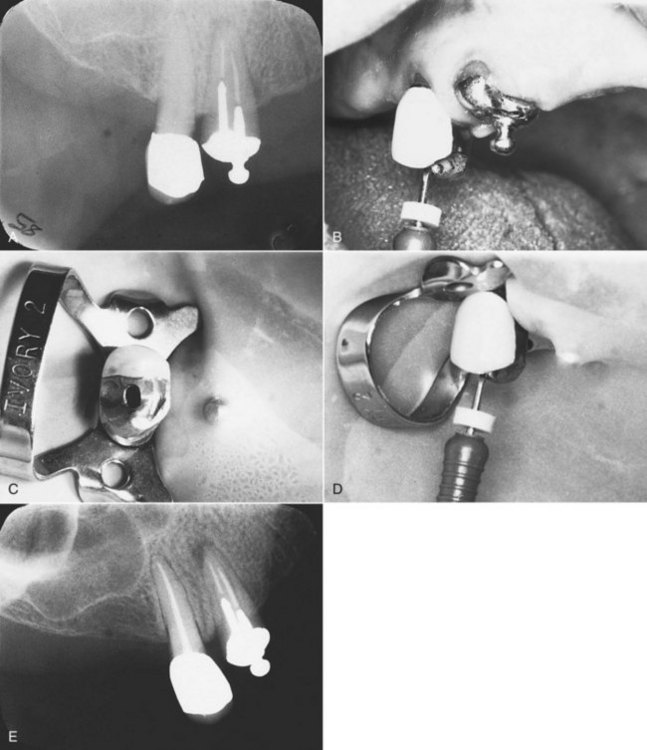

A test cavity is generally less useful as the test of last resort because of reduced dentin innervation. Vital pulps can sometimes be exposed and even negotiated with a file with minimal pain (Fig. 24-17); then the root canal treatment becomes part of the diagnostic procedure. Test cavities should be used only when other findings are suggestive but not conclusive.

FIG. 24-17 A-B, Vital pulp testing was inconclusive for the 91-year-old patient. C-D, Treatment was performed without local anesthesia to confirm pulp status.

Diffuse pain of vague origin is also uncommon in older pulps and limits the need for selective anesthesia. Pulpal disease is progressive and produces diagnostic signs or symptoms in a relatively short time. Nonodontogenic sources should be considered when factors associated with pulpal disease are not readily identified or when acute pain does not localize within a short time.

Discoloration of single teeth may indicate pulp death, but this is a less likely cause of discoloration with advanced age. Dentin thickness is greater, and the tubules are less permeable to blood or breakdown products from the pulp. Dentin deposition produces a yellow, opaque color that would indicate progressive calcification in a younger pulp, but this is common in older teeth.

Radiographs

Indications for and techniques of taking radiographs do not differ much among adult age groups. However, several physiologic, anatomic changes can significantly affect their interpretation. Film placement may be adversely affected by tori but can be assisted by the apical position of muscle attachments that increase the depth of the vestibule. Older patients may be less capable of assisting in film placement, and holders that secure the position should be considered. The presence of tori, exostoses, and denser bone (Fig. 24-18) may require increased exposure times for proper diagnostic contrast. The subjective nature of interpretation can be reduced with correct processing, proper illumination, and magnification.

FIG. 24-18 Dense bone may indicate the need for increased exposure times to improve contrast needed to see the canal and root anatomy.

The periapical area must be included in the diagnostic radiograph, which should be studied from the crown toward the apex. Angled radiographs should be ordered only after the original diagnostic radiograph suggests that more information is needed for diagnosis or to determine the degree of difficulty of treatment. Digital radiography may be more useful than conventional radiography in detecting early bone changes.85

In older patients, pulp recession is accelerated by reparative dentin and complicated by pulp stones and dystrophic calcification. Deep proximal or root decay and restorations may cause calcification between the observable chamber and root canal.

The depth of the chamber should be measured from the occlusal surface and its mesiodistal position noted. Receding pulp horns that are apparent on a radiograph may remain microscopically much higher. Deep restorations or extensive occlusal crown reduction may produce pulp exposures that were not expected. The axial inclinations of crowns may not correlate with the clinical observation when tilted teeth have been crowned or become abutments for fixed or removable appliances. Access to the root canals is the most limiting condition in root canal treatment of older patients.

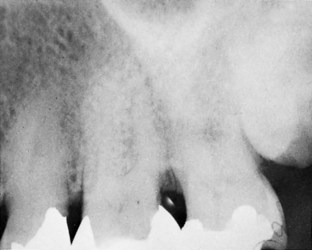

Canals should be examined for their number, size, shape, and curvature. Pulp has been demonstrated histologically even when not visible on radiographs, but in general, the two measurements did not differ even when pulp calcifications were present.38 Comparisons with adjacent teeth should be made. Small canals are the rule in older patients. A midroot disappearance of a detectable canal may indicate bifurcation rather than calcification. Canals calcify evenly throughout their length unless an irritant (e.g., caries, restoration, cervical abrasion) has separated the chamber from the root canal. Root-end fillings during root-end resection (more common during retreatment of older patients) indicate missed canals and roots as a common cause of failure.2

The lamina dura should be examined in its entirety and anatomic landmarks distinguished from periapical radiolucencies and radiopacities. The incidence of some odontogenic and nonodontogenic cysts and tumors characteristically increases with age, and this should be considered when vitality tests do not correlate with radiographic findings. However, the incidence of osteosclerosis and condensing osteitis decreases with age.

Resorption associated with chronic apical periodontitis may significantly alter the shape of the apex and the anatomy of the foramen through inflammatory osteoclastic activity (Fig. 24-19).15 The narrowest point in the canal may be difficult to determine; it is positioned farther from the radiographic apex because of continued cementum deposition.

FIG. 24-19 A, Resorption associated with chronic apical periodontitis may alter the shape and position of the foramen through osteoclastic activity. B, The narrowest point in the canal is now positioned farther from the radiographic apex.

A continued normal rate of cementum formation may be demonstrated by a canal or foramen that appears to end or exit short of the radiographic apex, and hypercementosis (Fig. 24-20) may completely obscure the apical anatomy.

Diagnosis and Treatment Plan

A clinical classification that accurately reflects the histologic status of the pulp and periapical tissues is not possible and not necessary beyond determining whether root canal treatment is indicated. A clinical judgment can be made based on the patient’s complaint, history, signs, symptoms, testing, and radiographs as to the vitality of the pulp and the presence or absence of periapical pathologic conditions. This classification has not been shown to be a factor in predicting success, interappointment or postoperative pain, or the number of visits necessary to complete treatment when the objectives of cleansing, shaping, and filling are clearly understood and consistently met.24 Of great clinical significance in treatment procedures is the assessment of pulp status to determine the depth of anesthesia necessary to perform the treatment comfortably.

One-appointment procedures offer obvious advantages to older patients. The length of a dental appointment does not usually cause inconvenience, as may more numerous appointments, especially if a patient must rely on another person for transportation or needs physical assistance to get into the office or operatory.

Root canal treatment as a restorative expediency on teeth with normal pulps must be considered when cusps have fractured or when supraerupted or malaligned teeth, intracoronal attachments, guide planes for partial abutments, rest seats, or overdentures require significant tooth reduction (Fig. 24-21). Predicting the need for future root canal treatment and a clinician’s ability to perform treatment later is even more important because the risk of losing the restoration during later access preparation increases with the thickness of the restoration and the reduction in canal size (Fig. 24-22). Because of a reduced blood supply, pulp capping is not as successful in older teeth as in younger ones, so it is not recommended. Any risk to the patient’s future health and the effect health may have on his or her ability to withstand future procedures should also be considered. Endodontic surgery at a later time is not as viable an alternative as for a younger patient.

FIG. 24-21 A, Valuable maxillary first- and second-molar abutments in an 85-year-old patient. B, Later need for endodontic therapy was made very challenging because of access difficulties.

FIG. 24-22 A, Intracoronal attachments, guide planes, and rest seats for partial abutments require significant tooth reduction and a bulk of metal that makes endodontic treatment more likely and difficult. B, Successful treatment and preservation of the restoration when the canal is small are challenges to the most skilled clinician.

Consultation and Consent

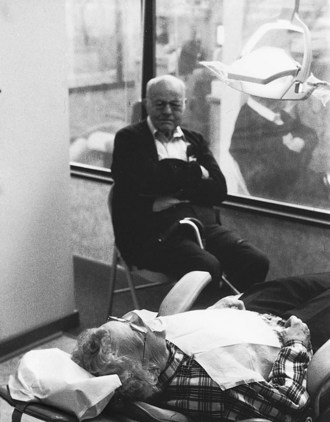

Good communication should be established and maintained with all patients, regardless of whether they are physically impaired or unable to make treatment decisions for themselves. Relatives or trusted friends should be included in consultations if their judgment is valued by the patient or needed for consent, but the clinician should direct the discussion toward the patient (Fig. 24-23).

FIG. 24-23 Some patients may request or require that a family member be present during consultation or treatment.

Clinicians should explain procedures in a way that is completely comprehensible and provides an opportunity for questions from the patient. Patient-friendly pamphlets are available from the American Association of Endodontists (AAE) that thoroughly explain and illustrate most endodontic procedures. Obtaining signed consent to outlined treatment is encouraged and may be especially useful if the patient is forgetful.

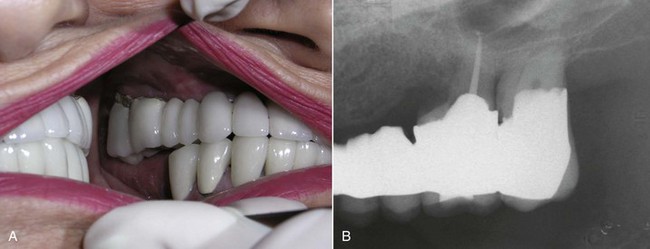

Determining the patient’s desires is as important as determining his or her needs, and it is required in obtaining informed consent (Fig. 24-24). Priorities in treating pain and infection to properly and esthetically restore teeth to health and function should be unaffected by age (Fig. 24-25). A patient’s limited life expectancy should not appreciably alter treatment plans and is no excuse for extractions or poor root canal treatment. It is important that all older patients be well informed of risks and alternatives (Fig. 24-26). Patients deserve a better explanation for their disease than that it is caused by age. When a physician told one patient that the problem with his knee was due to age, he said, “The other knee is the same age and nothing is wrong with it.”

FIG. 24-25 This 84-year-old patient was pleased to find that all these teeth could be saved with endodontic therapy and crowns. She was eager to make the investment in time and money, despite her limited life expectancy. Her concern focused on why these procedures had not been recommended by her previous dentist, whom she visited regularly.

FIG. 24-26 A, These two remaining abutments were the only teeth this 99-year-old patient needed to retain a removable prosthesis (B).

Acceptance of the eventual loss of teeth has been replaced by an understanding of the psychologic and functional importance of maintaining dentition. Older patients whose lives have been changed for the worse by a previous surgical procedure may readily recognize the implications of the loss of teeth.

The capability of the clinician and the availability of endodontic specialists should also be considered. The obligation to offer root canal treatment as an alternative to extraction may exceed a clinician’s ability to perform the procedure efficiently or successfully, and referral may be indicated. Older patients are more likely to be aware that there are specialists for performing root canals but will trust and do what their clinician recommends. In advance of the scheduled visit, referring clinicians should provide the endodontist with as much information about the patient as possible (and thoroughly explain the reason for referral to the patient). To support treatment adherence and understanding, clinicians should consider making the referral appointment for the patient while he or she is in the dental office.

Obtaining informed consent before dental procedures usually is not a problem. However, medically compromised or cognitively impaired patients may make it difficult to acquire valid informed consent. Neuropsychiatric impairment may result in gross manifestations and indicate a reduced level of competency. Physicians or mental health experts should be consulted as needed, and no elective procedures should be performed until valid consent is established. Fortunately, acute pulpal and periapical episodes in which immediate treatment is indicated for pain or infection are less common than the low-grade signs and symptoms of chronic disease.

Treatment

The vast majority of geriatric patients who need and demand endodontic therapy are ambulatory and not institutionalized. Institutionalized and nonambulatory patients require clinicians trained in those environments and facilities designed for access to dental health care (Fig. 24-27). Such access is a benefit required in most institutions, but alternatives to root canal therapy may be the only services available. Extended health care facilities are now required to have clinicians on staff before Medicare certification can be obtained. The dental office building, including both the interior design and the exterior approach, must be able to accommodate people with special needs.52 Access for those who use ambulation aids (e.g., canes, walkers, wheelchairs) should include comfort and safety in the parking lot, reception room, operatory, and rest room. Dental units can be designed to accommodate patients while in their own wheelchairs so that they do not require any transfer.72

FIG. 24-27 A, Office design should consider access for wheelchairs and walkers. B, Staff should be experienced in assisting patients into and out of the dental chair and operatory.

A physical and mental evaluation of the patient should determine the ideal time of day and length of time necessary to schedule treatment. A patient’s daily personal, eating, and resting habits should be considered, as well as any medication schedule. Morning appointments are preferable for some older patients, and their comfort, which varies with the procedure indicated, dictates the length of the appointment. Some patients prefer late morning or early afternoon visits to allow “morning stiffness” to dissipate.19

Older patients are more likely to tolerate long appointments, although chair positioning and comfort may be more important for older adults than for younger patients. Patients should be offered assistance into the operatory and into or out of the chair, and chair adjustments should be made slowly (and the ideal position established and used if possible). Pillows should be offered, as well as assistance in positioning them comfortably. Every effort should be made to accommodate the ideal position, even at some expense to the clinician’s comfort or access.

The patient’s eyes should be shielded from the intensity of the clinician’s light. If the temperature selected for the comfort of the office staff is too cool for the patient, a blanket should be available. As much work as possible should be performed at each visit, and a restroom break should be offered at intervals as the patient’s needs indicate. Jaw fatigue is readily recognizable and may be the most limiting factor in a long procedure, requiring periods of rest; however, once such fatigue is evident, the procedure should be terminated as soon as possible. Bite blocks are useful in comfortably maintaining freeway space and reducing jaw fatigue.

Retired persons may rely on rides from friends or relatives or public transportation to get to the dental office. Although they often arrive early for appointments, most older patients are in no hurry once they arrive. Enough time should be scheduled to allow some social exchange, and a sincere personal interest should be demonstrated before proceeding. Endodontic specialists need to consider separate consultations for making this initial social contact and evaluating the degree of difficulty that will determine the chair time needed to perform treatment. Staff should allow patients to initiate handshakes, which may be very uncomfortable to people with arthritic joints. From a behavioral and management standpoint, geriatric patients are among the most cooperative, available, and appreciative.

Older, medically compromised patients are at no more risk of complications than those in any other age group, and the chronicity of their diseases can alert the clinician to necessary precautions. Once again, clinicians should recognize that root canal therapy is far less traumatic than extraction for older patients.

The pulp vitality status and the cervical positioning of the rubber dam clamp determine the need for anesthesia. Older patients more readily accept treatment without anesthesia, and sometimes they must be persuaded that anesthesia is necessary for root canal treatment if their routine operative procedures have been performed without it. Generally, older patients demonstrate less anxiety about dental treatment and may have previous experience with root canal treatment.

The cutting of dentin does not produce the same level of response in an older patient for the same reason that a test cavity is not as revealing during examination. The number of low-threshold, high-conduction-velocity nerve endings in dentin is reduced or absent, and they do not extend as far into the dentin. In addition, the dentinal tubules are more calcified.9,66 A painful response may not be encountered until actual pulp exposure has occurred.

Anatomic landmarks that are used as guides to needle placement during block and infiltration injections are usually more distinguishable in older patients. The effects of epinephrine should be considered when selecting anesthetics for routine endodontic procedures. Anesthetics should be deposited very slowly (and skeletal muscle avoided) if epinephrine is the vasoconstrictor.

The reduced width of the periodontal ligament35 makes needle placement for supplementary intraligamentary injections more difficult. Placing an anesthetic under pressure produces an intraosseous anesthesia that extends to the apex and to adjacent teeth, but it also distributes small amounts of solution systemically.64 Intraosseous injections can significantly increase the success of pulpal anesthesia but can be associated with a transient increase in heart rate when anesthetics contain epinephrine. Smaller amounts of anesthetic should be deposited during intraosseous injections, and the depth of anesthesia should be checked before repeating the procedure. Like intrapulpal anesthesia, intraosseous anesthesia is not prolonged; the pulp tissue must be removed within 20 minutes. The majority of patients receiving an intraosseous injection of 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine (correct ratio) solution experience a transient increase in heart rate. This would not be clinically significant in most healthy patients, but in the older patient whose medical condition, drug therapies, or epinephrine sensitivity suggests caution, 3% mepivacaine is a good alternative for intraosseous injections.57 Chapter 20 gives further information.

The reduced volume of the pulp chamber makes intrapulpal anesthesia difficult in single-rooted teeth and almost impossible in multirooted teeth. Initial pulp exposures are also hard to identify. Wedging a small needle into each canal to produce the necessary pressure for anesthesia is the method of last resort. Every effort should be made to produce profound anesthesia. Patients should be encouraged to report any unpleasant sensation, and a prompt response should be made to any complaint. Patients should never be expected to tolerate pulpal pain.

Isolation

Either single-tooth or multitooth rubber dam isolation can be used. Badly broken-down teeth may not provide an adequate purchase point for the rubber dam clamp, so alternate rubber dam isolation methods should be considered (see Chapter 5). Multiple-tooth isolation may be used if adjacent teeth can be clamped and saliva output is low or a well-placed saliva ejector can be tolerated (Fig. 24-28). A three-holed rubber dam with the tooth in question in the middle allows for better maneuverability, especially when using the dental operating microscope. A petroleum-based lubricant for the lips and gingiva reduces chafing from saliva or perspiration beneath the rubber dam. Reduction in salivary flow and gag reflex reduces the need for a saliva ejector. Artificial saliva is available and should be used just before isolation, because it is difficult to apply after the dam is in place.

FIG. 24-28 Multiple-tooth isolation techniques protect the patient from instruments but do not provide the fluid-tight environment preferred for the safe use of sodium hypochlorite.

Canals should be identified and their access maintained if restorative procedures are indicated for isolation. The clinician should not attempt isolation and access in a tooth with questionable marginal integrity of its restorations. Fluid-tight isolation cannot be compromised when sodium hypochlorite is used as an irrigant. Difficult-to-isolate defects produced by root decay present a good indication, in initial preparation, for the use of sonic handpieces that use flow-through water as an irrigant.

The many merits of single-visit root canal procedures is generally recommended when isolation is compromised (see Chapters 4 and 5). The few minor benefits of multiple-visit treatment are further reduced if an interappointment seal is difficult to obtain.

Access

Adequate access and identification of canal orifices are likely the most challenging aspects of providing root canal treatment for older patients. Although the effects of aging and multiple restorations may reduce the volume and coronal extent of the chamber or canal orifice, its buccolingual and mesiodistal positions remain the same and can be predicted from radiographs and clinical examination. Canal position, root curvature, and axial inclinations of roots and crowns should be considered during the examination (Fig. 24-29). The effects of access on existing restorations and the possible need for actual removal of the restoration should be discussed with the patient before initiating treatment (Fig. 24-30). Coronal tooth structure or restorations should be sacrificed when they compromise access for preparation or filling (Fig. 24-31). Perhaps all restorations should be removed before endodontic treatment in order to remove the common factors (caries, marginal breakdown, cracks) that may have caused the pulp and periradicular disease and to assess the tooth’s prognosis and future treatment needs. One study found that almost all teeth (93%) had these factors; only 56% were detectable clinically or on radiographs.1 (See Chapter 7 for more details on proper access openings.)

FIG. 24-29 A, This mandibular third molar in a 78-year-old patient has tilted mesially and has been restored with a full crown, upright to allow a path of insertion for a removable partial denture. B, Successful root canal treatment is the primary objective. Retaining the crown when possible also represents significant savings to the patient. This crown will be replaced; a post space has been prepared. C, This maxillary third molar on the same patient is tilted mesially and rotated, making access (D) the most difficult part of this treatment.

FIG. 24-30 A, Radiograph of strategic abutment and calcified canal. B, To increase visibility and alignment, access is initiated before isolation. C, An access opening that conserves tooth structure and provides straight-line access is then isolated with the rubber dam (D) and treated (E).

FIG. 24-31 A, Caries control and isolation of this tooth necessitated crown removal. B, Endodontic treatment was completed in one visit.

Magnification in the range of 2.5× to 4.5× (e.g., Designs for Vision, Ronkonkoma, NY) has become a common tool and can be designed to fit the clinician’s most comfortable working distance. The growing acceptance and availability of endodontic microscopes34 offer clear magnification ranging up to 25× or greater and have obvious advantages in treating smaller and narrower geriatric canals (see Chapter 6, Fig. 6-4).

Location and penetration of the canal orifice are often difficult and time consuming in calcified canals. The most important instrument for initial penetration is the DG-16 explorer. The explorer will not stick in solid dentin, but it will resist dislodgment in the canal. Once the canal has been distinguished, negotiation is attempted with a stainless steel (SS) #8, #10, or #15 K-file. The #6 file lacks stiffness in its shaft and easily bends and curls under gentle apical pressure. Nickel-titanium (NiTi) files lack strength in the long axis and are contraindicated for initial negotiation. The canal can be negotiated using a watch-winding action with slight apical pressure. Chelating agents are seldom of value in locating the orifice but can be useful during canal negotiation. Dyes may distinguish an orifice from the surrounding dentin.

Pain, bleeding, disorientation of the probing instruments, or an unfamiliar feel to the canal may indicate a perforation (Fig. 24-32). The size of the perforation and the extent of contamination determine the success of repair (which should be done immediately) and do not necessarily indicate failure (Fig. 24-33). Supraerupted teeth can be easily perforated (Fig. 24-34) if the reduced distance to the furcation is not noted.

FIG. 24-32 A, Pain, bleeding, or disorientation of the probing instrument may indicate a perforation, which should be immediately investigated with a radiograph. B, Repair has the best success when the perforation opening is pinpoint and periodontal tissues are normal.

FIG. 24-33 A, Perforation occurred during access of these calcified canals. B, Endodontic treatment was immediately completed after the perforation repair.

A lengthy, unproductive search for canals is fatiguing and frustrating to both the clinician and the patient. Scheduling a second attempt at this procedure is often productive. Personal clinical experiences and judgment determine when the search for the canals must be terminated and referral or alternatives to nonsurgical root canal treatment considered (Fig. 24-35).

FIG. 24-35 A, Midtreatment referral of a mandibular first premolar only after perforation and repair with amalgam. B, Canal was still detectable with enhanced vision technique, and treatment was completed.

Modifications to enhance access vary from widening the axial walls to increasing visibility or light to complete removal of the crown. Alterations may be indicated after canal penetration to the apex if tooth structure interferes with instrumentation or filling procedures.

Teeth with chronic apical periodontitis will usually have patent canals (Fig. 24-36). Surgical access (Fig. 24-37) may be preferred if the risk of deviation from the long axis exists when canals are calcified and the tooth is heavily restored (Fig. 24-38).

FIG. 24-36 A, Strategic middle abutment for a long fixed bridge presents a challenge to the most skilled clinician to perform predictable root canal treatment. B, Poor crown/root ratio makes root-end surgery a poor option. Root canal treatment should have been considered before using this lone-standing premolar as an abutment. C, Calcified canals can usually be detected and treated when a nonvital pulp and chronic apical periodontitis are present, even when the canals are not apparent on the radiograph. Asymptomatic, calcified canals on teeth with vital pulps are much more difficult to find and negotiate. D, External resorption repair before endodontic treatment made negotiation and instrumentation of this incisor tooth more difficult.

FIG. 24-37 A, Extremely calcified canals and thin roots make the risk of perforation high. B, Surgical access and root-end filling was performed rather than weakening the tooth trying to locate the root canal system via an orthograde approach.

FIG. 24-38 A, Multiple pins were used to restore this middle abutment on a fixed bridge. B, Extreme care and exceptional skill are required to maintain proper alignment to find and treat the canal with a deep access opening.

Very few canals of older teeth, even maxillary anterior teeth, have adequate diameter to allow the safe and effective use of broaches. Older pulps may give a clinical appearance that reflects their calcified, atrophic state with the stiffened, fibrous consistency of a wet toothpick. Any broached canals should be thoroughly cleaned and shaped at the same appointment.

Preparation

The calcified appearance of the canals resulting from the aging process presents a much different clinical situation than that of a younger pulp in which trauma, pulpotomy, decay/caries, or restorative procedures have induced premature canal obliteration. Unless further complicated by reparative dentin formation, this calcification appears to be much more concentric and linear. This allows easier penetration of canals once they are found. An older tooth is more likely to have a history of earlier treatments, with a combination of calcifications present. (Chapter 9 includes a description of cleaning and shaping root canals.)

The length of the canal from the actual anatomic foramen to the CDJ increases with the deposition of cementum throughout life.37 The advantage of this situation in the treatment of teeth with vital pulps is countered by the presence of necrotic, infected debris in this longer canal when periapical pathosis is already present. The actual CDJ width or most apical extent of the dentin remains constant with age.68

Flaring of the canal should be performed as early in the procedure as possible to provide for a reservoir of irrigation solution and reduce the stress on metal instruments that occurs when they bind with the canal walls. Thorough and frequent irrigation should be performed to remove the debris that could block access. Files with a triangular or square cross-section may penetrate into the walls with greater force than the fracture resistance of small files (when used with a reaming action) and result in instrument fatigue and fracture. The benefits of instruments with no rake angle and a crown-down technique are recommended.

Because this CDJ is the narrowest constriction of the canal, it is the ideal place to terminate the canal preparation. This point may vary from 0.5 to 2.5 mm from the radiographic apex and be difficult to determine clinically. Calcified canals reduce the clinician’s tactile sense in identifying the constriction clinically, and reduced periapical sensitivity in older patients reduces the patient’s response that would indicate penetration of the foramen. Increased incidence of hypercementosis, in which the constriction is even farther from the apex, makes penetration into the cemental canal almost impossible. Achieving and maintaining apical patency are more difficult. Apical root resorption associated with periapical pathosis further changes the shape, size, and position of the constriction. The use of electronic apex-finding devices is sometimes limited in heavily restored teeth when contact with metal can bleed off the current.

The frequency and intensity of discomfort after cleaning and shaping have not been shown to be related to the amount of preparation, the type of interappointment medication or temporary filling, the pulp or periapical status, the tooth number or age, or whether the root canal filling is completed at the same appointment.71 The more constricted CDJ permits a much smaller pulp wound and resists penetration, even with the initial small files. Patency is difficult to establish and maintain. Dentin debris creates a matrix early in the preparations84 and further reduces the risk of overinstrumentation or the forcing of debris into the periapical tissues,54 which could cause an acute apical periodontitis or abscess. Further access to periapical tissues through the canal is likewise limited.

Obturation

For the older patient, the prudent clinician selects gutta-percha filling techniques that do not require unusually large midroot tapers and do not generate pressure in this area, which could result in root fracture (Fig. 24-39). (See Chapter 10 for the most appropriate technique to use to seal the canal.)

FIG. 24-39 A, Third molar abutment for 7-unit bridge in an 84-year-old patient with limited opening. B, Instrumentation of this molar without excessive removal of coronal or midroot dentin.

The coronal seal plays an important role in maintaining an apically healthy environment, and it has a significant impact on long-term success.70 Even a root-filled tooth should not have its canals exposed to the oral environment. A thermoplastic synthetic polymer-based root-filling material (Resilon) may significantly reduce the coronal leakage that can result from root caries after root canal treatment, as well as increase resistance to root fracture.61,73 Permanent restorative procedures should be scheduled as soon as possible, and intermediate restorative materials should be selected and properly placed to maintain a seal until that time. When mechanical retention is not ensured with the preparation, glass ionomer cements are recommended.

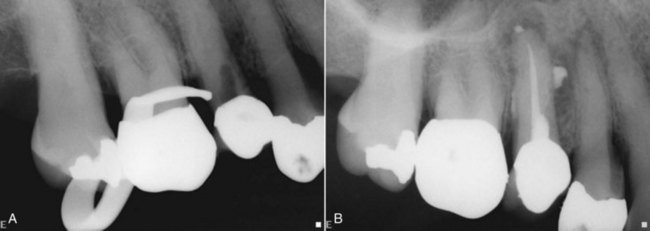

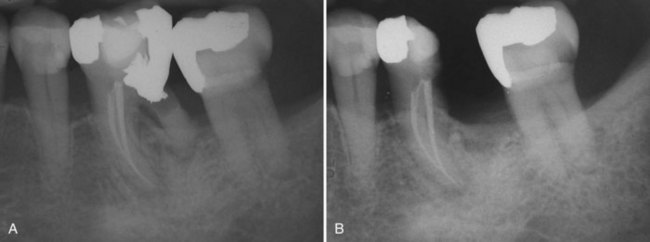

Success and Failure

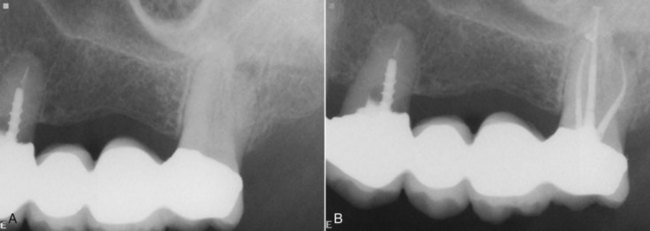

Repair of periapical tissues after endodontic treatment in older patients is determined by most of the same local and systemic factors that govern the process in all patients. With vital pulps, periapical tissues are normal and can be maintained with an aseptic technique, confining preparation and filling procedures to the canal space. Infected nonvital pulps with periapical pathosis must have this process altered in favor of the host tissue, and repair is determined by the ability of this tissue to respond. Factors that influence repair have their greatest effect on the prognosis of endodontic therapy when periapical abnormalities are present. With aging, arteriosclerotic changes of blood vessels increase and the viscosity of connective tissue is altered, making repair more difficult. The rate of bone formation and normal resorption decreases with age, and the aging of bone results in greater porosity and decreased mineralization of the formed bone. Although periradicular tissues will heal as readily in elderly as in young patients,71 a 6-month recall period to evaluate repair by means of radiographs may not be adequate (Fig. 24-40).25

FIG. 24-40 A, Mandibular premolar in an older patient exhibits apical periodontitis. Following endodontic treatment (B), healing was incomplete at 6 months (C) and after 1 year (D). Complete healing of the apical periodontitis was seen 5 years postoperatively (E).

Studies that suggest differences in success among age groups must note the smaller numbers (usually in this older treatment group) and the local factors that make treatment difficult. Overlooked canals are a more common cause of failure in older patients (Fig. 24-41), which explains the increased clinical indications for retrograde fillings when surgical treatment is attempted.2 As an isolated symptom, heat sensitivity may indicate a missed canal. (For further information on assessing failures and possible retreatment, see Chapter 25.)

Endodontic Surgery

Generally, considerations and indications for endodontic surgery are not affected by age. The need for establishing drainage and relieving pain are not common indications for surgery. Anatomic complications of the root canal system, such as small (Fig. 24-42) or completely calcified canals, nonnegotiable root curvatures, extensive apical root resorption, or pulp stones, occur with greater frequency in older patients. Perforation during access, losing length during instrumentation, ledging, and instrument separation are iatrogenic treatment complications associated with treatment of calcified canals.

FIG. 24-42 A, Even though a small canal is detectable on the radiograph, it appears that an earlier unsuccessful attempt has been made to find it. B, It was decided that the risk of damage to a satisfactory restoration justified surgical treatment for this patient.

Medical considerations may require consultation but do not contraindicate surgical treatment when extraction is the alternative (Fig. 24-43). In most instances, surgical treatment may be performed less traumatically than an extraction, which may also result in the need for surgical access to complete root removal. Many older patients receive low-dose aspirin therapy to prevent blood clot formation and may be subject to embolic formation if the treatment is interrupted. Aspirin therapy should be continued throughout dental procedures, even during extraction or surgery. Local measures are sufficient to control bleeding.4 Interrupting therapeutic levels of continuous anticoagulation therapy for dental surgery is not based on scientific fact but seems to be based on its own mythology.79 A thorough medical history and evaluation should reveal the need for any special considerations such as prophylactic antibiotic premedication, sedation, hospitalization, or more detailed evaluation.

FIG. 24-43 A, Unsuccessful and symptomatic treatment on a mandibular second molar of a 78-year-old patient was surgically treated (B), with less trauma than the extraction alternative. C, Complete healing at 1 year, apparently unaffected by age.

Local considerations in treatment of older patients include an increase in the incidence of fenestrated or dehisced roots and exostoses (Fig. 24-44). The thickness of overlying soft and bony tissue is usually reduced, and apically positioned muscle attachments extend the depth of the vestibule. Smaller amounts of anesthetic and vasoconstrictor are needed for profound anesthesia. Tissue is less resilient, and resistance to reflection appears to be diminished. The oral cavity is usually more accessible with the teeth closed together, because the lips can more easily be stretched. The apex can actually be more surgically accessible in older patients. Ability to gain such access varies with the skill of the surgeon; however, some areas are unreachable by even the most experienced clinicians.

FIG. 24-44 Exostoses, as illustrated in this mandibular anterior tooth (A) and maxillary molar (B), covered with thin tissue that can easily be torn during flap reflection, as well as the more obvious heavy bone and its effect on surgical access.

The position of anatomic features—the sinus, floor of the nose, and neurovascular bundles—remains the same, but their relationship to surrounding structures may change when teeth have been lost. The need may arise to combine endodontic and periodontal flap procedures, and every effort should be made to complete these procedures in one sitting.

When root-end surgery is to be performed, the surgeon must consider whether the root that will be left is long enough and thick enough for the tooth to continue to remain functional and stable (Fig. 24-45). This factor is especially important when the tooth will be used as an abutment (Fig. 24-46). (Detailed surgical procedures are presented in Chapter 21.)

FIG. 24-45 A, Periradicular periodontitis and distal root caries evident in this 78-year-old patient. B, Apicoectomy, retrocavity preparation, and retrofilling, and C, cervical caries restoration were done for this lower molar tooth.

FIG. 24-46 A, External root resorption accompanied by periradicular periodontitis in an important canine abutment tooth. Endodontic retreatment, surgical repair of the resorptive defect (B), and apicoectomy (C) were performed.

Ecchymosis is a more common postoperative finding in older patients and may appear to be extreme. The patient should be reassured that this condition is normal and that normal color may take as long as 2 weeks to return. The blue discoloration will change to brown and yellow before it disappears. Immediate application of an ice pack after surgery reduces bleeding and initiates coagulation to reduce the extent of ecchymosis. Later, application of heat helps to dissipate the discoloration.

Restoration

Root canal treatment saves roots, and restorative procedures save crowns. Combined, these procedures are returning more teeth to form and function than were thought possible just a few decades ago. Special consideration must be given to post design, especially when small posts are used in abutment teeth; root fracture is common in older adults when much taper is used. Post failure or fracture occurs when small-diameter parallel posts are used (Fig. 24-47). Posts are not usually needed when root canal treatment is performed through an existing crown that will continue to be used (Fig. 24-48). (General considerations and procedures for postendodontic restoration are detailed in Chapter 22.)

FIG. 24-48 A, Intact margins permitted the continued use of this crown. B, The access was restored with an amalgam-bond core.

The value of the tooth, its restorability, its periodontal health, and the patient’s wishes should be part of the evaluation preceding endodontic therapy. The restorability of older teeth can be affected when root decay has limited access to sound margins or reduced the integrity of remaining tooth structure (Figs. 24-49 and 24-50). There can also be insufficient vertical and horizontal space when opposing or adjacent teeth are missing. Patient desires to save appliances can sometimes be fulfilled with creative attempts that may outlive them (Fig. 24-51).

FIG. 24-49 A, This older woman insisted on saving her tooth in spite of extensive root caries on the distobuccal root. B, Root canal treatment was performed, and the root caries was removed and restored with Geristore.

FIG. 24-50 A, Root caries and periodontal involvement of this mandibular molar tooth necessitated hemisection to retain the mesial root for restoration (B).

FIG. 24-51 A, Unrestorable caries contraindicated endodontic treatment on this molar abutment. B, Root amputation of buccal roots was performed to increase the lifespan of this bridge.

In conclusion, geriatric endodontics will gain a more significant role in complete dental care as an aging population recognizes that a complete dentition, and not complete dentures, is a part of its destiny.

1. Abbott PV. Assessing restored teeth with pulp and periapical disease for the presence of cracks, caries and marginal breakdown. Aust Dent J. 2004;49:33.

2. Allen RK, Newton CW, Brown CEJr. A statistical analysis of surgical and nonsurgical endodontic retreatment cases. J Endod. 1989;15:261.

3. A Profile of Older Americans: 2001, Administration on Aging, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

4. Ardekian L, Gaspar R, Peled M, et al. Does low-dose aspirin therapy complicate oral surgical procedures? J Am Dent Assoc. 2000;131:331.

5. Barbakow FH, Cleaton-Jones P, Friedman D. An evaluation of 566 cases of root canal therapy in general dental practice: postoperative observations. J Endod. 1980;6:485.

6. Baum BJ. Evaluation of stimulated parotid saliva flow rate in different age groups. J Dent Res. 1981;60:1292.

7. Berkey DB, Berg RG, Ettinger RL, Mersel A, Mann J. The old-old dental patient. J Am Dent Assoc. 1996;127:321.

8. Bernick S. Effect of aging on the nerve supply to human teeth. J Dent Res. 1967;46:694.

9. Bernick S, Nedelman C. Effect of aging on the human pulp. J Endod. 1975;3:88.

10. Bhaskar SN. Orban’s oral histology and embryology, ed 11. St Louis: Mosby; 1990.

11. Browne RM, Tobias RS. Microbial microleakage and pulpal inflammation: a review. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1986;2:177.

12. Campbell PR. Bureau of the census, population projections for states, by age, race, and hispanic origin: 1993 to 2020. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1994.

13. Clark DJ, Sheets CG, Paquette JM. Definitive diagnosis of early enamel and dentin cracks based on microscopic evaluation. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2003;15(7 Special Issue):391.

14. Crispin S, Ettinger R. The influence of systemic diseases on oral health care in older adults. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007;138(Suppl):7S-14S.

15. Delzangles B. Scanning electron microscopic study of apical and intracanal resorption. J Endod. 1989;14:281.

16. Dolan TA, Berkey DB, Mulligan R, Saunders ML. Geriatric dental education and training in the United States: 1995 white paper findings. Gerodontology. 1996;13:94.

17. Douglas CW, Furino A. Balancing dental service requirements and supplies: epidemiologic and demographic evidence. J Am Dent Assoc. 1990;121(5):587.

18. Douglas CW, Gammon MD, Orr RB. Oral health status in the U.S.: prevalence of inflammatory periodontal disease. J Dent Educ. 1985;49:365.

19. Ettinger R, Beck T, Glenn R. Eliminating office architectural barriers to dental care of the elderly and handicapped. J Am Dent Assoc. 1979;98(3):398.

20. Fedele DJ, Sheets CG. Issues in the treatment of root caries in older adults. J Esthet Dent. 1998;10:243.

21. Feski J, Davies DM, Frances C, Gelbier S. The emotional effects of tooth loss in edentulous people. Br Dent J. 1998;184:90.

22. Fouad AF, Burleson J. The effects of diabetes mellitus in endodontic treatment outcome: data from electronic patient record. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:43.

23. Frank ME, Hettinger TP, Mott AK. The sense of taste: neurobiology, aging, and medication effects. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1992;3(4):371.

24. Friedman S. Prognosis of initial therapy. Endod Topics. 2002;2:59-88.

25. Frisk F, Hakeberg M. A 24-year follow-up of root filled teeth and periapical health amongst middle aged and elderly women in Göteborg, Sweden. Int Endod J. 2005;38:246-254.

26. Fuss Z, Trowbridge H, Bender IB, Rickoff B, Sorin S. Assessment of reliability of electrical and thermal pulp testing agents. J Endod. 1986;12:301.

27. Goodis HE, Rossall JC, Kahn AJ. Endodontic status in older U.S. adults: report of a survey. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132:1525.

28. Hartmann R, Muller F. Clinical studies on the appearance of natural anterior teeth in young and old patients. Gerodontology. 2004;21:10.

29. Heft MW, Mariotti AJ. Geriatric pharmacology. Dent Clin North Am. 2002;46:869.

30. Hummel SK, et al. The quality of the majority of removable partial dentures worn by the adult US population. J Prosthet Dent. 2002;88:73.

31. Joshipura KJ, Willett WC, Douglass CW. The impact of edentulousness on food and nutrient intake. J Am Dent Assoc. 1996;127:459.

32. Kahler W. The cracked tooth conundrum: terminology, classification, diagnosis, and management. Am J Dent. 2008;21:275-282.

33. Keir DM, Walker WA3rd, Schindler WG, Dazey SE. Thermally induced pulpalgia in endodontically treated teeth. J Endod. 1991;17:38.

34. Kersten DD, MInesand P, Sweet M. Use of the microscope in endodontics: results of a questionnaire. J Endod. 2008;34:804.

35. Klein A. Systematic investigations of the thickness of the periodontal ligament. Z Stomatol. 1928;26:417.

36. Krell KV, McMurtrey LG, Walton RE. Vasculature of the dental pulp of arteriosclerotic monkeys: light and election microscopic findings. J Endod. 1994;20:469.

37. Kuttler Y. Microscopic investigation of root apexes. J Am Dent Assoc. 1955;50:544.

38. Kuyk JK, Walton RE. Comparison of the radiographic appearance of root canal size to its actual diameter. J Endod. 1990;16:528.

39. Lindhe J, Socransky S, Nyman S, Westfelt E, Haffajee A. Effect of age on healing following periodontal therapy. J Clin Periodontol. 1985;12:774.