Chapter 24 Skin disease

Introduction

Skin diseases have a high prevalence throughout the world. In developing countries infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, leprosy and onchocerciasis are common, whereas in developed countries inflammatory disorders such as eczema and acne are common. Skin disorders can be inherited, e.g. Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, a part of normal development, e.g. acne vulgaris, or may present as part of a systemic disorder, e.g. systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Approximately 25% of the UK population will develop a skin problem and skin disease accounts for 10% of the workload of family doctors. The common reasons that people with a rash present, are itching or pain, disturbed sleep, anxiety, depression, lack of self-confidence (if rash is obviously visible); and interfering with work (such as allergic hand eczema in a chef, builder or hairdresser).

Rarely, skin disease can be fatal. Examples are malignant melanoma, toxic epidermal necrolysis and pemphigus.

Structure and function of the skin

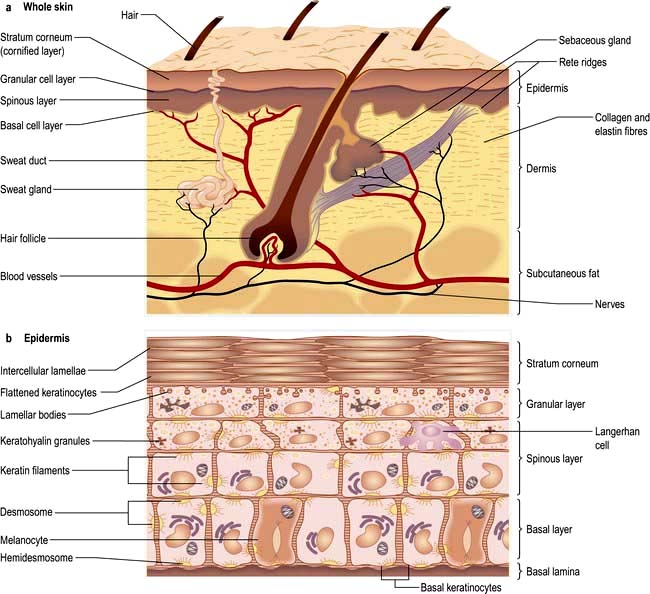

The skin consists of four distinct layers:

The functions of the skin are summarized in Box 24.1.

![]() Box 24.1

Box 24.1

Functions of the skin

Physical barrier against friction and shearing forces

Physical barrier against friction and shearing forces

Protection against infection (immune and innate), chemicals, ultraviolet irradiation

Protection against infection (immune and innate), chemicals, ultraviolet irradiation

Prevention of excessive water loss or absorption

Prevention of excessive water loss or absorption

Ultraviolet-induced synthesis of vitamin D

Ultraviolet-induced synthesis of vitamin D

Sensation (pain, touch and temperature)

Sensation (pain, touch and temperature)

The epidermis

The epidermis is a stratified epithelium of ectodermal origin that arises from dividing basal keratinocytes. The downward projections of the epidermis into the dermis are called the ‘rete ridges’. The lower epidermal cells (basal layer) produce a variety of keratin filaments and desmosomal proteins (e.g. desmoglein and desmoplakin), which make up the ‘cytoskeleton’. This confers strength to the epidermis preventing it shedding. Higher up in the granular layer, complex lipids are secreted by the keratinocytes and these form into intercellular lipid bilayers, which act as a semipermeable skin barrier. The upper cells (stratum corneum) lose their nuclei and become surrounded by a tough impermeable ‘envelope’ of various proteins (loricrin, involucrin, filaggrin and keratin). Changes in lipid metabolism and protein expression in the outer layers allow normal shedding of keratinocytes.

Keratinocytes can secrete a variety of cytokines (e.g. interleukins, gamma-interferon, tumour necrosis factor alpha) in response to tissue injury or in certain skin diseases. These play a role in specific immune function, cutaneous inflammation and tissue repair. There is a further layer of protection against microbial invasion – the innate immune system of the skin. This comprises neutrophils and macrophages as well as keratinocyte-produced antimicrobial peptides (called β-defensins and cathelicidins). Expression of these peptides is both constitutive and induced by skin inflammation and they are active against infection and play a role in wound healing. A deficiency of these peptides may account for the susceptibility of people with atopic eczema to skin infection.

Other cells in the epidermis

Melanocytes are found in the basal layer and secrete the pigment melanin. These protect against UV irradiation. Racial differences are due to variation in melanin production, not melanocyte numbers.

Merkel cells are also found in the basal layer and originate either from neural crest or epidermal keratinocytes. They are numerous on finger tips and in the oral cavity and play a role in sensation.

Langerhans’ cells are dendritic cells found in the supra-basal layer. They derive from the bone marrow and express the cytokine CCR6. They are guided to normal skin, which contains a CCR6 agonist called macrophage inflammatory protein 3α. Langerhans’ cells endocytose extracellular antigens in the skin and then migrate to local lymph nodes for T cell presentation and thus act as antigen-presenting cells.

Basement membrane zone

The basement membrane zone (see Fig. 24.27) is a complex proteinaceous structure consisting of type IV, VII and XVII collagen, hemidesmosomal proteins, integrins and laminin. Collectively, they hold the skin together, keeping the epidermis firmly attached to the dermis. Inherited or autoimmune-induced deficiencies of these proteins can cause skin fragility and a variety of blistering diseases (see p. 1221).

The dermis

The dermis is of mesodermal origin and contains blood and lymphatic vessels, nerves, muscle, appendages (e.g. sweat glands, sebaceous glands and hair follicles) and a variety of immune cells such as mast cells and lymphocytes. It is a matrix of collagen and elastin in a ground substance.

The sweat glands

Eccrine sweat glands are found throughout the skin except the mucosal surfaces.

Apocrine sweat glands are found in the axillae, anogenital area and scalp and do not function until puberty.

The sweat glands and vasculature are involved in temperature control.

The sebaceous glands

These are inactive until puberty. They are responsible for secreting sebum or grease onto the skin surface (via the hair follicle) and are found in high numbers on the face and scalp.

Nerves

The skin is richly innervated. Nerve fibres enable sensation of touch, pain, itch, vibration and change in temperature.

Hair

Hairs arise from a downgrowth of epidermal keratinocytes into the dermis. The hair shaft has an inner and outer root sheath, a cortex and sometimes a medulla. The lower portion of the hair follicle consists of an expanded bulb (which also contains melanocytes) surrounding a richly innervated and vascularized dermal papilla. The hair regrows from the bulb after shedding. There are three types of hair:

Terminal: medullated coarse hair, e.g. scalp, beard, pubic

Terminal: medullated coarse hair, e.g. scalp, beard, pubic

Vellus: non-medullated fine downy hairs seen on the face of women and in prepubertal children

Vellus: non-medullated fine downy hairs seen on the face of women and in prepubertal children

Lanugo: non-medullated soft hair on newborns (most marked in premature babies) and occasionally in people with anorexia nervosa.

Lanugo: non-medullated soft hair on newborns (most marked in premature babies) and occasionally in people with anorexia nervosa.

All hair follicles follow a growth cycle: anagen (growth phase), catagen (involution phase), telogen (shedding phase). At any one time, most hairs (>90%) will be in the anagen phase, which is typically 3–5 years for scalp hair.

Grey hair is due to decreased tyrosinase activity in the hair bulb melanocytes. White hair is due to total loss of these melanocytes.

The subcutaneous layer

The subcutaneous layer consists predominantly of adipose tissue as well as blood vessels and nerves. This layer provides insulation and acts as a lipid store.

FURTHER READING

Borkowski AW, Gallo RL. The coordinated response of the physical and antimicrobial peptide barriers of the skin. J Invest Dermatol 2011; 131:285–287.

Lin JY, Fisher DE. Melanocyte biology and skin pigmentation. Nature 2007; 445:843–850.

Shimomura Y, Christiano AM. Biology and genetics of hair. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 2010; 11:109–132.

Approach to the patient

The history should aim to elicit the following points:

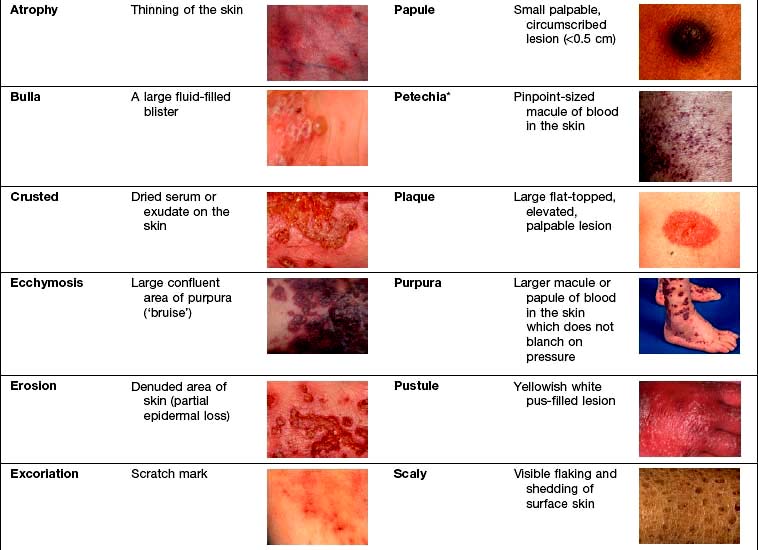

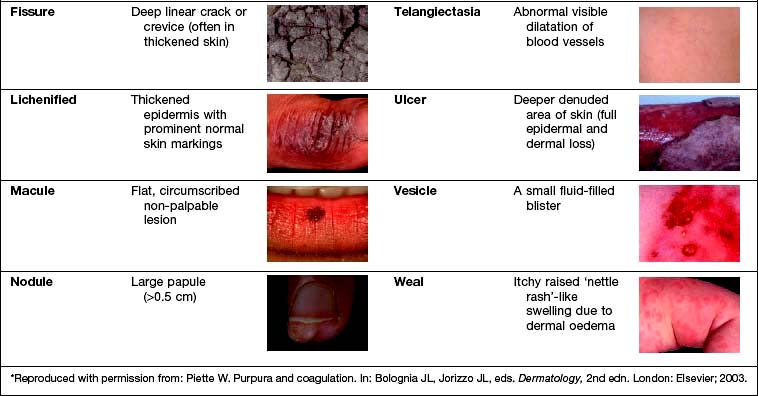

Examination entails looking and feeling a rash (for terminology, see Table 24.1). It should include an assessment of nails, hair and mucosal surfaces even if these are recorded as unaffected. The following terms are used to describe distribution: flexural, extensor, acral (hands and feet), symmetrical, localized, widespread, facial, unilateral, linear, centripetal (trunk more than limbs), annular and reticulate (lacey network or mesh like).

Investigation. With regard to investigation, clinical acumen remains the most useful tool in dermatology but a variety of tests are useful in confirming a diagnosis (Table 24.2).

Table 24.2 Investigations used in skin disorders

| Test | Use | Clinical example |

|---|---|---|

Skin swabs |

Bacterial culture |

Impetigo |

Blister fluid |

Electron microscopy, viral culture and PCR |

Herpes simplex |

Skin scrapes |

Fungal culture |

Tinea pedis |

Microscopy |

Scabies |

|

Nail sampling |

Fungal culture |

Onychomycosis |

Wood’s light |

Fungal fluorescence |

Scalp ringworm |

Erythrasma |

||

Blood tests |

Serology |

Streptococcal cellulitis |

Autoantibodies |

Systemic lupus erythematosus |

|

HLA typing |

Dermatitis herpetiformis |

|

DNA analysis |

Epidermolysis bullosa |

|

Skin biopsy |

Histology |

General diagnosis |

Immunohistochemistry |

Cutaneous lymphoma |

|

Immunofluorescence |

Immunobullous disease |

|

Culture |

Mycobacteria/fungi |

|

Patch tests |

Allergic contact eczema |

Hand eczema |

Urine |

Dipstick (glucose) |

Diabetes mellitus |

Cytology (red cells) |

Vasculitis |

|

Dermatoscopy (direct microscopy of skin) |

Assessment of pigmented lesions |

Malignant melanoma |

Infections

Bacterial infections (see also p. 114)

The skin’s normal bacterial flora prevents colonization by pathogenic organisms. A break in epidermal integrity by trauma, leg ulcers, fungal infections (e.g. athlete’s foot) or abnormal scaling of the skin (e.g. in eczema) can allow infection. Nasal carriage of bacteria can be a source of reinfection.

Impetigo

Impetigo is a highly infectious skin disease most common in children (Fig. 24.2). It presents as weeping, exudative areas with a typical honey-coloured crust on the surface. It is spread by direct contact. The term ‘scrum pox’ refers to impetigo spread between rugby players. Staphylococci or group A β-haemolytic streptococci are the causative agents: skin swabs should be taken.

Treatment

Impetigo is usually treated with oral antibiotics for 7–10 days (flucloxacillin 500 mg four times daily for Staphylococcus; phenoxymethylpenicillin 500 mg four times daily for Streptococcus). Other close contacts should be examined and children should avoid school for 1 week after starting therapy. If impetigo appears resistant to treatment or recurrent, take nasal swabs and check other family members. Nasal mupirocin (three times daily for 1 week) is useful to eradicate nasal carriage, especially in hospital staff. Community-acquired MRSA (in chapter 4) is increasingly recognized as a cause of superficial skin infections and treatment should be governed by bacterial sensitivities.

Bullous impetigo/staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

Rarely Staphylococcus releases an exfoliating toxin which acts high up in the epidermis: toxin A causes blistering at the site of infection (bullous impetigo), toxin B spreads through the body causing more widespread blistering (staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, SSSS). The latter is more common in childhood with very low mortality rates. In adults it is often associated with renal disease or immunosuppression, and mortality rates increase to 50%. Both these toxins cleave desmoglein 1 (a desmosomal protein) so mucosal involvement does not occur (this is analogous to pemphigus foliaceous which has the same target antigen, p. 1222).

SSSS can mimic toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN, see p. 1231). It can be differentiated in two ways: mucosal involvement only occurs in TEN, and skin biopsy shows a more superficial split in SSSS (intraepidermal) than in TEN (subepidermal). Both bullous impetigo and SSSS are treated with anti-staphylococcal antibiotics (e.g. flucloxacillin) and supportive care.

Cellulitis

Cellulitis presents as a hot, sometimes tender area of confluent erythema of the skin due to infection of the deep subcutaneous layer. It often affects the lower leg, causing an upward-spreading, hot erythema, and occasionally will blister, especially if oedema is prominent. It may also be seen affecting one side of the face. Patients are often unwell with a high temperature. It is usually caused by a β-haemolytic streptococcus, rarely a staphylococcus, and sometimes community-acquired MRSA (in chapter 4). In the immunosuppressed or diabetic patient Gram-negative organisms or anaerobes should be suspected.

There may be an obvious portal of entry for infection such as a recent abrasion or a venous leg ulcer. The web spaces of the toes should be examined for fungal infection. Skin swabs are usually unhelpful. Confirmation of infection is best done serologically: antistreptolysin O titre (ASOT) and antiDNAse B titre (ADB).

Erysipelas is the term used for a more superficial infection (often on the face) of the dermis and upper subcutaneous layer that clinically presents with a well-defined edge. However, erysipelas and cellulitis overlap so it is often impossible to make a meaningful distinction.

Necrotizing fasciitis (see p. 116).

Treatment

Treatment is with phenoxymethylpenicillin (or erythromycin) and flucloxacillin (all 500 mg four times daily). If disease is widespread, treatment with antibiotics should be given intravenously for 3–5 days followed by at least 2 weeks of oral therapy. It is also necessary to treat any identifiable underlying cause. If cellulitis is recurrent, low-dose antibiotic prophylaxis (e.g. phenoxymethylpenicillin 500 mg twice daily) is used as each episode will cause further lymphatic damage. Post-cellulitic oedema is common and predisposes to further episodes of cellulitis.

Ecthyma

Ecthyma is also an infection due to Streptococcus or Staphylococcus aureus or occasionally both. It presents as chronic well-demarcated, deeply ulcerative lesions sometimes with an exudative crust. It is commoner in developing countries, being associated with poor nutrition and hygiene. It is rare in the UK but is seen more commonly in intravenous drug users and people with HIV infection.

Treatment is with phenoxymethylpenicillin and flucloxacillin (both 500 mg four times daily) for 10–14 days.

Erythrasma

Erythrasma is caused by Corynebacterium minutissimum. It usually presents as an orange-brown flexural rash, and is often seen in the axillae or toe web spaces (Fig. 24.3). It is frequently misdiagnosed as a fungal infection. The rash shows a dramatic coral pink fluorescence under Wood’s (ultraviolet) light.

Treatment is with oral erythromycin 500 mg four times daily for 7–10 days.

Folliculitis

Folliculitis is an inflammation of the hair follicle. It presents as itchy or tender papules and pustules. Staphylococcus aureus is frequently implicated. It is commoner in humid climates and when occlusive clothes are worn. A variant occurs in the beard area (called ‘sycosis barbae’), which is commoner in black Africans. This is probably caused by the ability of shaved hair to grow back into the skin, especially if the hair is naturally curly. Extensive, itchy folliculitis of the upper trunk and limbs should alert one to the possibility of underlying HIV infection. Folliculitis following use of hot tubs is due to Pseudomonas ovale.

Treatment is with topical antiseptics, topical antibiotics (e.g. sodium fusidate) or oral antibiotics (e.g. flucloxacillin 500 mg or erythromycin 500 mg both four times daily for 2–4 weeks).

Boils (furuncles)

Boils are a rather more deep-seated infection of the skin, often caused by Staphylococcus. These can cause painful red swellings. They are commoner in teenagers and often recurrent. Recurrent boils may rarely occur in diabetes mellitus or in immunosuppression. Large boils are sometimes called ‘carbuncles’. Swabs should be taken to check antibiotic sensitivity as community-acquired MRSA is an increasingly common cause.

Treatment is with oral antibiotics (e.g. erythromycin 500 mg four times daily for 10–14 days) and occasionally by incision and drainage.

Antiseptics such as chlorhexidine (as soap) can be useful in prophylaxis.

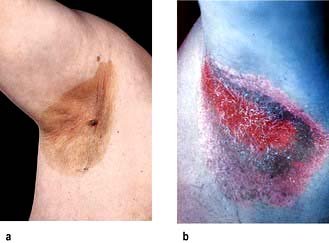

Hidradenitis suppurativa

This condition is characterized by a painful, discharging, chronic inflammation of the skin at sites rich in apocrine glands (axillae, groins, natal cleft). The cause is unknown but it is commoner in females and within some families it appears to be inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion. The initial lesion is occlusion of the hair follicle producing an inflammatory reaction that spreads to the apocrine glands. Clinically it presents after puberty with papules, nodules and abscesses which often progress to cysts and sinus formation. With time, scarring arises. The condition follows a chronic relapsing/remitting course and is worse in obese individuals.

Treatment is difficult but weight loss, ‘prophylactic’ antibiotics, oral retinoids, zinc and co-cyprindiol (2 mg cyproterone acetate + 35 µg ethinylestradiol in females only) have been tried. They should be used as for acne vulgaris (p. 1212). Severe recalcitrant cases have been treated with intravenous infliximab, a monoclonal antibody (p. 72). Surgery and skin grafting is sometimes required.

Pitted keratolysis

This is a superficial infection of the horny layer of the skin caused by a corynebacterium. It frequently involves the soles of the forefoot and appears as numerous small punched-out circular lesions of a rather macerated skin (e.g. as seen after prolonged immersion). There may be an associated hyperhidrosis of the feet and a prominent odour.

Treatment. Topical antibiotics (e.g. sodium fusidate or clindamycin, applied three times daily for 2–4 weeks) and topical anti-sweating lotions are effective therapies.

Mycobacterial infections

Leprosy (Hansen’s disease) (p. 130)

Leprosy usually involves the skin, and the clinical features depend on the body’s immune response to the organism Mycobacterium leprae.

Indeterminate leprosy is the commonest clinical type, especially in children. This presents as small, hypopigmented or erythematous circular macules with occasional mild anaesthesia and scaling. This may resolve spontaneously or progress to one of the other types. Biopsy reveals a perineural granulomatous infiltrate and scant acid-fast bacilli.

Tuberculoid leprosy presents with a few larger, hypopigmented (see Fig. 4.28) or erythematous plaques with an active erythematous, often raised, rim. Lesions are usually markedly anaesthetic, dry and hairless, reflecting the nerve damage. Nerves may be enlarged and palpable. Biopsy shows a granulomatous infiltrate centred on nerves but no organisms.

Lepromatous leprosy presents with multiple inflammatory papules, plaques and nodules. Loss of the eyebrows (‘madarosis’) and nasal stuffiness are common. Skin thickening and severe disfigurement may follow. Anaesthesia is much less prominent. Biopsy shows numerous acid-fast bacilli.

Diagnosis and treatment are discussed on page 131.

Skin manifestations of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis can occasionally cause skin manifestations:

Lupus vulgaris usually arises as a post-primary infection. It usually presents on the head or neck with red-brown nodules that look like apple jelly when pressed with a glass slide (‘diascopy’). They heal with scarring and new lesions slowly spread out to form a chronic solitary erythematous plaque. Chronic lesions are at high risk of developing squamous cell carcinoma.

Lupus vulgaris usually arises as a post-primary infection. It usually presents on the head or neck with red-brown nodules that look like apple jelly when pressed with a glass slide (‘diascopy’). They heal with scarring and new lesions slowly spread out to form a chronic solitary erythematous plaque. Chronic lesions are at high risk of developing squamous cell carcinoma.

Tuberculosis verrucosa cutis arises in people who are partially immune to tuberculosis but who suffer a further direct inoculation in the skin. It presents as warty lesions on a ‘cold’ erythematous base.

Tuberculosis verrucosa cutis arises in people who are partially immune to tuberculosis but who suffer a further direct inoculation in the skin. It presents as warty lesions on a ‘cold’ erythematous base.

Scrofuloderma arises when an infected lymph node spreads to the skin causing ulceration, scarring and discharge.

Scrofuloderma arises when an infected lymph node spreads to the skin causing ulceration, scarring and discharge.

The tuberculides are a group of rashes caused by an immune manifestation of tuberculosis rather than direct infection. Erythema nodosum is the commonest and is discussed on page 1216. Erythema induratum (‘Bazin’s disease’) produces similar deep red nodules but these are usually found on the calves rather than the shins and they often ulcerate.

The tuberculides are a group of rashes caused by an immune manifestation of tuberculosis rather than direct infection. Erythema nodosum is the commonest and is discussed on page 1216. Erythema induratum (‘Bazin’s disease’) produces similar deep red nodules but these are usually found on the calves rather than the shins and they often ulcerate.

Viral infections

Viral exanthem

This is the commonest type of virus-induced rash and presents clinically as a widespread nonspecific erythematous maculopapular rash. It probably arises due to circulating immune complexes of antibody and viral antigen localizing to dermal blood vessels. The rash can be caused by many different viruses (e.g. echovirus, erythrovirus, human herpes virus-6, Epstein–Barr virus; see chapter 4) and so is rarely diagnostic. The rash will resolve spontaneously in 7–10 days.

Herpes simplex virus (see also p. 97)

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) occurs as two genomic subtypes. Most people are affected in early childhood with HSV type 1 but the infection is usually subclinical. Occasionally it can present with either clusters of painful blisters on the face or a painful gingivostomatitis. In some individuals cell-mediated immunity is poor and they get recurrent attacks of HSV, often manifest as cold sores. Immunosuppression can also cause a recrudescence of HSV. HSV can also autoinoculate into sites of trauma and present as painful blisters/pustules which may be seen for example on the fingers of healthcare workers (‘herpetic whitlow’).

HSV type 2 infections are discussed on page 97. Other rare complications of HSV infection include corneal ulceration, eczema herpeticum, chronic perianal ulceration in AIDS patients and erythema multiforme.

Treatment

Oral valaciclovir (500 mg twice daily for 5 days) is used for primary HSV and painful genital HSV. Cold sores are treated with aciclovir cream but this must be used early to be effective in shortening an attack; recurrent sores are treated with oral therapy. Attacks of herpes become less frequent with time. Intravenous aciclovir must be used in immunosuppressed patients.

Varicella zoster virus

Varicella zoster virus (VZV) causes the common childhood infection called chickenpox. It is discussed on page 98. It also causes herpes zoster.

Herpes zoster (shingles)

‘Shingles’ results from a reactivation of VZV. It may be preceded by a prodromal phase of tingling or pain, which is then followed by a painful and tender blistering eruption in a dermatomal distribution (Fig. 24.4 and Fig. 4.15, p. 98). The blisters occur in crops, may become pustular and then crust over. The rash lasts 2–4 weeks and is usually more severe in the elderly. Occasionally more than one dermatome is involved.

Complications of shingles include severe, persistent pain (post-herpetic neuralgia), ocular disease (if the ophthalmic nerve is involved) and rarely motor neuropathy.

Treatment

Herpes zoster requires adequate analgesia and antibiotics (if secondary bacterial infection is present). Valaciclovir 1 g or famciclovir 250 mg three times daily for 7 days is used, or oral aciclovir 800 mg, five times daily for 7 days helps shorten the attack if given early in the illness. Brivudine 125 mg is also available. High-dose intravenous aciclovir is used in immunosuppressed patients. It remains unclear how useful aciclovir therapy is in preventing prolonged post-herpetic neuralgia.

Human papilloma virus

Human papilloma virus (HPV) is responsible for the common cutaneous infection of ‘viral warts’.

Common warts are papular lesions with a coarse roughened surface, often seen on the hands and feet, but also on other sites. Small black dots (bleeding points) are often seen within the lesion (Fig. 24.5). If they occur on the face they are often elongated (‘filiform’) Children and adolescents are usually affected. Spread is by direct contact and is also associated with trauma.

Plantar warts (verrucae) is the term used for lesions on the soles of the feet. They often appear flat (‘inward growing’) although they have the same papillomatous surface change and black dots are often revealed if the skin is pared down (unlike callosities). Warts may be painful or tender if they are over pressure points or around nail folds.

Plane warts are much less common and are caused by certain HPV subtypes. They are clinically different and appear as very small, flesh-coloured or pigmented, flat-topped lesions (best seen with side-on lighting) with little in the way of surface change and no black dots within them. They are usually multiple and are frequently found on the face or the backs of the hands.

Anogenital warts are usually seen in adults and are normally transmitted by sexual contact. They are rare in childhood and, whilst child sex abuse should always be considered, it should be remembered they may well have been transmitted through non-sexual contact. HPV subtypes 16 and 18 are potentially oncogenic and are associated with cervical and anal carcinomas.

Treatment

Common warts on the skin are surprisingly difficult to treat effectively but they almost always resolve spontaneously after months to years (with no scarring), presumably due to cell-mediated immune recognition. When they do resolve, they tend to do so rapidly within a few days.

Regular use of a topical keratolytic agent (e.g. 2–10% salicylic acid) over many months with weekly paring of the lesion helps speed up resolution in some patients and remains the mainstay of treatment. A course of cryotherapy (freezing) can also help. Cautery, surgery, carbon dioxide laser, alpha-interferon injection and bleomycin injection have all been used with variable success but are not recommended, as treatments may be very painful and can cause permanent scarring.

Genital warts are usually treated with cryotherapy, trichloroacetic acid, 5% imiquimod cream or topical podophyllin. People with genital warts (and their sexual partners) must be screened for other sexually transmitted diseases.

HPV vaccines against the high-risk oncogenic subtypes (6, 11, 16 and 18) are now available; they should help protect against cervical neoplasia but will have no impact on common warts.

Molluscum contagiosum (‘water blisters’)

Molluscum contagiosum is a common cutaneous infection of childhood caused by the pox virus. Clinically, lesions are multiple small (1–3 mm) translucent papules which often look like fluid-filled vesicles but are in fact solid. Individual lesions may have a central depression called a punctum. They exhibit the Köbner phenomenon (p. 1208). They can occur at any body site including the genitalia. Transmission is by direct contact. Occasionally lesions may be up to 1 cm in diameter (‘giant molluscum’).

They usually continue to occur in crops over 6–12 months and rarely require treatment as they spontaneously resolve. Any form of localized trauma, including scratching, helps speed up resolution, and cryotherapy is used in older children. One per cent stabilized hydrogen peroxide cream or 5% imiquimod cream is used in younger children. Molluscum in an adult, especially if giant, should raise the underlying possibility of immunosuppression, especially HIV infection.

Orf

Orf is a disease of sheep (and occasionally goats) due to a pox virus infection. It causes a vesicular and pustular rash around the mouths of young lambs. People who come into contact with the affected fluid may develop lesions on the hands. Clinically these appear as 1–2 cm reddish papules with a surrounding erythema which usually become pustular. The lesion(s) resolves spontaneously after 4–6 weeks and immunity is lifelong. Occasionally, orf is complicated by erythema multiforme.

Fungal infections

Fungal skin disease (mycosis) has a high prevalence in humans with ‘thrush’ and ‘athlete’s foot’ being two of the commonest examples. In the immunosuppressed, mycoses can be widespread and life-threatening. There are three groups of pathogenic fungi that commonly affect the outer layer of skin or keratinizing epithelium: dermatophytes, Candida albicans and pityrosporum.

Dermatophyte infection

By definition, dermatophytes cause a ‘ringworm’ type of rash. The three main genera responsible are Trichophyton, Microsporum and Epidermophyton. These organisms are identified by microscopy and culture of skin, hair or nail samples. The clinical appearance depends in part on the organism involved, the site affected and the host reaction. All are spread by direct contact from other humans or from infected animals.

Tinea corporis

Ringworm of the body usually presents with asymmetrical, scaly patches which show central clearing and an advancing, scaly, raised edge. Occasionally, vesicles or pustules may be seen in the edge. Central clearing is not a universal feature and it is recommended that all asymmetrical scaly lesions should be scraped for fungus. Ringworm of the face (tinea faciei) often arises after the use of topical steroids. It tends to be more erythematous and less scaly than trunk lesions and it may become itchy after sun exposure.

Tinea cruris

Ringworm of the groin is extremely common worldwide. Early on, the lesions appear as well-demarcated red plaques with an arc-like border extending down the upper thigh (Fig. 24.6). Central clearing may appear and a few pustules or vesicles may be seen if inflammation is intense. Satellite lesions, suggestive of Candida, are not present.

Tinea pedis

Athlete’s foot may be confined to the toe clefts where the skin looks white, macerated and fissured. It may also be more diffuse, usually causing a diffuse scaly erythema of the soles spreading on to the sides of the foot. Annular lesions are rarely present. There may be an associated hyperhidrosis and fungal involvement of one or more toe-nails. In severe infection a strong inflammatory reaction can occur causing pustules or blistering and this often leads to a misdiagnosis of pompholyx-type eczema.

Tinea manuum

Ringworm of the hands also presents with a diffuse erythematous scaling of the palms with variable skin peeling and skin thickening. Annular lesions are rare at this site.

Tinea capitis

Scalp ringworm infections are common. Fungus may confine itself to within the hair shaft (endothrix) or spread out over the hair surface (ectothrix). The latter can cause fluorescence under a Wood’s lamp (ultraviolet light). Scalp ringworm is spread by close contact (especially in schools and households) and may also be spread indirectly by hairdressers. Increase in travel and immigration has allowed the spread of different pathogenic fungi (e.g. Trichophyton tonsurans from Central America, Trichophyton violaceum from India and Pakistan) into new countries where there is overcrowding and poor social conditions. The majority of UK cases are due to T. tonsurans (which does not show fluorescence).

Tinea capitis is much commoner in children, especially those of black African origin whose scalp and hair seems more susceptible to fungal invasion. The clinical appearance of scalp ringworm is highly variable from a mild diffuse scaling with no hair loss (similar to dandruff) to the more typical appearance of circular scaly patches in the scalp with associated alopecia and broken hairs. As the host’s immune response increases a few pustules may appear and an exudate may be present. At worst, a full-blown ‘kerion’ develops; a boggy swollen mass with copious quantities of discharging pus and exudate accompanied by severe alopecia. This is still poorly recognized and inappropriately treated with antibiotics and attempted surgical drainage.

Extensive infection is occasionally accompanied by a widespread papulopustular rash on the trunk. This is a so-called ‘id reaction’ and probably relates to the host immune response to the fungus. It resolves when the fungal infection is treated.

Tinea unguium

Ringworm of the nails is increasingly common with age and frequently ignored as it is often asymptomatic. Clinically this presents as asymmetrical whitening (or yellowish black discoloration) of one or more nails which usually starts at the distal or lateral edge before spreading throughout the nail (Fig. 24.7). The nail plate appears thickened. Crumbly white material appears under the nail plate and this is the best fungal infections specimen to obtain for mycology sampling. The nail plate may become destroyed with advanced disease.

‘Tinea incognito’

This is the term used to describe a fungal skin infection that has been modified by therapy with a topical steroid. The clinical appearance is variable but may show a nonspecific erythema with little in the way of scaling or a few reddish nodules. The history of the rash improving with treatment (owing to the suppression of inflammation) but worsening and spreading every time it is stopped is typical. Skin scrapings for mycology or even a biopsy should confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment

Localized ringworm of the body or flexures is treated with topical antifungal creams (clotrimazole, miconazole, terbinafine or amorolfine applied three times daily for 1–2 weeks). More widespread infection, tinea pedis, tinea manuum and tinea capitis require oral antifungal therapy. Itraconazole (100 mg daily) and terbinafine (250 mg daily) are the most effective drugs used for periods of 1–2 months. High-dose griseofulvin is still used in children for scalp ringworm (15–20 mg/kg per day for 8 weeks).

Tinea unguium of the toe-nails is the most resistant to treatment. Itraconazole (100 mg daily or 200 mg twice daily for 1 week per month ‘pulsed therapy’) or terbinafine (250 mg daily) given for 3–6 months will cure up to about 80% of cases.

Candida albicans

Candida albicans (see also p. 170) is a yeast that is sometimes found as part of the body’s flora, especially in the gastrointestinal tract. It acts as an opportunist, taking hold in the skin when there is a suitable warm moist environment such as in nappy rash (p. 1234) or intertrigo in obese individuals (Fig. 24.8).

The flexural areas affected are red with a rather ragged peeling edge that may contain a few small pustules. Small circular areas of erythema or small papules and pustules may be seen in front of the advancing edge (satellite lesions).

Candida may also affect the moist interdigital clefts of the toes and mimic tinea pedis. In people who have their hands immersed frequently in water (e.g. cleaners, nurses) Candida may cause infection in the macerated skin of the finger web spaces or the damaged skin around the nail folds (‘chronic paronychia’). Nail infection may mimic tinea unguium. Candida can infect mucosal surfaces of the mouth or genital tract. This tends to occur in patients taking broad-spectrum antibiotics (due to suppression of protective bacterial flora) or in immunosuppressed patients. Clinically, superficial white or creamy pseudomembranous plaques appear which can be scraped off leaving raw areas underneath.

Treatment

Treatment is aimed at removing any underlying predisposing factor and applying topical antifungal creams, e.g. clotrimazole or miconazole (or the equivalent as mouth lozenges/pessaries). Candida nail infections require systemic antifungal therapy with an imidazole such as itraconazole (100 mg daily for 3–6 months). Recurrent candidiasis is relatively common, especially in women. Diabetes mellitus should always be excluded. Repeated topical treatment or an oral imidazole may be needed.

Pityrosporum

This yeast occurs as part of the normal flora of human skin. Colonization is prominent in the scalp, flexures and upper trunk. There are two morphological variants, Pityrosporum ovale and Pityrosporum orbiculare, and the mycelial form of this yeast is called Malassezia furfur. Pityrosporum can overgrow in some individuals and has been implicated in three dermatoses:

Pityriasis versicolor

This is a relatively common condition of young adults caused by infection with Pityrosporum. In white people, it presents most commonly on the trunk with reddish brown scaly macules, which are asymptomatic. In black-skinned individuals (or in whites who are sun-tanned) it more commonly presents as macular areas of hypopigmentation. Inappropriate use of topical steroids tends to spread the rash.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis can be confirmed by skin scrapings or Wood’s light examination (yellow fluorescence).

Differential diagnosis includes pityriasis lichenoides chronica, which is a rare condition with recurrent crops of brown scaly papules and erythematous patches. It is seen up to the age of 30 years and can last for years. Treatment is with UVB and topical emollients.

Treatment

Treatment is with selenium sulphide or 2% ketoconazole shampoo (apply to body and remove after 30–60 min and repeat daily for 1 week) or a topical imidazole cream (twice daily for 10 days). Oral itraconazole (100 mg twice daily for 1 week) can be used for resistant cases. The pigmentation takes months to recover even after successful treatment. The condition may recur but can be re-treated.

Pityrosporum folliculitis

This is common in young adult males and characterized by small itchy papules and pustules on the upper back which are centred on hair follicles. It is commoner in people with Down’s syndrome. It responds well to ketoconazole shampoo or a topical imidazole cream (twice daily for 2 weeks).

Infestations

Scabies

Scabies is an intensely itchy rash caused by the mite Sarcoptes scabiei. It can affect all races and people of any social class. It is most common in children and young adults but can affect any age group. There are 300 million cases of scabies in the world each year. It is commoner in poorer countries with social overcrowding.

Scabies is spread by prolonged close contact such as within households or institutions, and by sexual contact. It presents clinically with itchy red papules (or occasionally vesicles and pustules) which can occur anywhere in the skin but rarely on the face, except in neonates. The distribution of lesions is often suggestive of the diagnosis (Fig. 24.9). Sites of predilection are between the web spaces of the fingers and toes, on the palms and soles, around the wrists and axillae, on the male genitalia, and around the nipples and umbilicus.

The pathognomonic sign is of linear or curved skin burrows but these are not always present. The pruritus is normally worse at night. Excoriations and secondary bacterial infection may complicate the rash. Scabies can be confirmed by taking skin scrapings of a lesion and examining a potassium hydroxide preparation for the mite and/or its eggs by microscopy.

Treatment

A topical scabicide (e.g. 5% permethrin) is applied and washed off after 10 hours. For the treatment to be successful the following factors should be noted:

All the skin below the neck should be treated, including the genitalia, palms and soles, and under the nails. Treat the head and neck regions in infants (up to age 2 years).

All the skin below the neck should be treated, including the genitalia, palms and soles, and under the nails. Treat the head and neck regions in infants (up to age 2 years).

All close contacts should be treated at the same time even if asymptomatic.

All close contacts should be treated at the same time even if asymptomatic.

Reapply scabicide to the hands if they are washed during the treatment period.

Reapply scabicide to the hands if they are washed during the treatment period.

Washing or cleaning of recently worn clothes (preferably at 60°C) is recommended to avoid reinfection.

Washing or cleaning of recently worn clothes (preferably at 60°C) is recommended to avoid reinfection.

Patients should be warned that the pruritus may persist for up to 4 weeks after successful treatment.

Patients should be warned that the pruritus may persist for up to 4 weeks after successful treatment.

Malathion can be used if permethrin is unavailable; benzyl benzoate is used occasionally but is very irritant and should not be used in children. Lindane is a cheap therapy but there are concerns about resistance to this drug and neurotoxicity. Oral ivermectin 200 µg/kg, as 2 doses 2 weeks apart, is as effective as topical therapy and is easy to use.

Crusted scabies (Norwegian scabies)

Crusted scabies is a clinical variant that occurs in immunosuppressed individuals where huge numbers of mites are carried in the skin. Patients are not always itchy but they are extremely infectious after relatively minimal contact, which is unfortunate as the diagnosis is often delayed. Clinically, the condition presents as hyperkeratotic crusted lesions, especially on the hands and feet. Lesions may progress such that the patient has a widespread erythema with irregular crusted plaques. It can therefore mimic infected eczema or psoriasis.

Treatment is with careful barrier nursing, repeated applications of a scabicide and oral ivermectin (200 µg /kg – at least 2 doses 1 week apart).

SIGNIFICANT WEBSITE

Crusted scabies guidelines: www.health.nt.gov.au/Centre_for_Disease_Control/Publications/CDC_Protocols/index.aspx

Lice infection

Lice are blood-sucking ectoparasites that can affect man in three ways.

Head lice (pediculosis capitis)

Head lice is a common infection worldwide affecting predominantly children and being commoner in females. Spread is by direct contact and encouraged by overcrowding. It usually presents with itch, scalp excoriations and papules on the neck.

Diagnosis can be confirmed by the presence of eggs (‘nits’) stuck to the hair shaft. Adult lice are seen rarely in heavy infection.

Treatment. Eradication is difficult because of non-compliance as well as resistance patterns. Malathion, carbaryl and phenothrin (two applications 7 days apart with a contact time of 12 hours) are the most commonly used agents. If one treatment fails, a different insecticide is used for the next course in an individual. Treatment is usually repeated after 7 days and metal nit combs may help remove the eggs. In resistant cases high-dose oral ivermectin (400 µg/kg as 2 doses 1 week apart) is used.

Body lice (pediculosis corporis)

Infestation with body lice is a disease of poverty and neglect. It is rarely seen in developed countries except in homeless individuals and vagrants. It is spread by direct contact or sharing infested clothing. The lice and eggs are rarely seen on the patient but are commonly found on the clothing. It presents with itch, excoriations and sometimes post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation of the skin.

Treatment consists of malathion or permethrin for the patient and high-temperature washing and drying of clothing.

Pubic lice (crabs, phthiriasis pubis) (p. 160)

Pubic lice are transmitted by direct contact, usually sexual. Infestation presents with itching, especially at night. Lice can be seen near the base of the hair with eggs somewhat further up the shaft. Occasionally eyebrows, eyelashes and the beard area are affected.

Treatment is as for head lice but all sexual contacts should be treated and other sexually transmitted diseases should be screened for. Pubic lice of the eyelashes is treated with white soft paraffin three times daily for 1–2 weeks.

Arthropod-borne diseases (‘insect bites’ or papular urticaria)

These depend on contact with an animal (e.g. dog, cat, bird) that is infested with fleas (Cheyletiella) or on bites from flying insects (e.g. midges, mosquitoes). In the case of flea bites the animal itself may be itchy with scaly and thickened skin. These fleas can also live in soft furnishings (e.g. carpets and beds) even after the animal has been removed. Bites present as itchy urticated lesions, which are often grouped in clusters. The legs are most commonly affected. It is not unusual for an individual to react badly to bites when other family members seem unaffected. Anti-flea treatment of the animal and furnishings is required. Insect repellents and appropriate clothing help lessen bites from flying insects.

Infestations with bed bugs have increased enormously in the past decade in the developed world. They can be seen as small brown/black lentil-sized insects at night-time as they are attracted to warmth and carbon dioxide of sleeping humans. Infestations require professional insecticide treatments of properties. Advice can be obtained from the National Pest Technicians Association (www.npta.org.uk).

Papulo-squamous/inflammatory rashes

Eczema

Introduction

Eczema is synonymous with the term dermatitis and the two words are interchangeable. In the developed world, eczema accounts for a large proportion of skin disease. It is estimated that 10% of people have some form of eczema at any one time, and up to 40% of the population will have an episode of eczema during their lifetime.

All eczemas (Table 24.3) have some features in common and there is a spectrum of clinical presentation from acute through to chronic. Vesicles or bullae may appear in the acute stage if inflammation is intense. In subacute eczema the skin can be erythematous, dry and flaky, oedematous and crusted (especially if secondarily infected). Chronic persistent eczema is characterized by thickened or lichenified skin. Eczema is nearly always itchy. Histologically ‘eczematous change’ refers to a collection of fluid in the epidermis between the keratinocytes (‘spongiosis’) and an upper dermal perivascular infiltrate of lymphohistiocytic cells. In more chronic disease there is marked thickening of the epidermis (‘acanthosis’).

Table 24.3 Classification of eczema

| Endogenous | Exogenous |

|---|---|

Atopic eczema

This type of eczema (‘endogenous eczema’) occurs in individuals who are ‘atopic’ (p. 823). It is common, occurring in up to 5% of the UK population. It is commoner in early life, occurring at some stage during childhood in up to 10–20% of all children.

Aetiology

The exact pathophysiology is not fully understood but there is an initial selective activation of Th2-type CD4 lymphocytes in the skin which drives the inflammatory process. This precedes the chronic phase when Th0 and Th1 cells predominate. In at least 80% of cases there is a raised serum total IgE level. Atopic eczema is a genetically complex, familial disease with a strong maternal influence. A positive family history of atopic disease is often present: there is a 90% concordance in monozygotic twins but only 20% in dizygotic twins. If one parent has atopic disease, the risk for a child of developing eczema is about 20–30%. If both parents have atopic eczema the risk is greater than 50%.

Studies have shown abnormal skin-homing T cells in eczema compared to controls. Genetic research points towards a primary problem of skin barrier function, suggesting the above immunological changes are secondary. Loss-of-function mutations in the epidermal barrier protein filaggrin cause ichthyosis vulgaris but can predispose to atopic eczema in Caucasian individuals. Different mutations in the same gene have been found in Japanese people with eczema. Filaggrin is coded by FLG gene in the epidermal differentiation complex on chromosome 1q21. Very strong linkage to this region would suggest that other genes in this area are also involved in the development of atopic eczema (e.g. loricrin, involucrin, S100 calcium-binding proteins). Linkage is also found to 3q21, 3p22–24, 17q25, 20p. Other candidate genes include SPINK 5 (a serine protease inhibitor), mast cell chymotryptase and peptidoglycan recognition proteins.

Exacerbating factors

Infection either in the skin or systemically can lead to an exacerbation, possibly by a superantigen effect. Paradoxically, lack of infection (in infancy) may cause the immune system to follow a Th2 pathway and allow eczema to develop (the so-called ‘hygiene hypothesis’). Strong detergents, chemicals and even woollen clothes can be irritant and exacerbate eczema. Teething is another factor in young children. Severe anxiety or stress appears to exacerbate eczema in some individuals. Cat and dog fur can certainly make eczema worse, possibly by both allergic and irritant mechanisms. The role of house dust mites and diet is less clear cut. There is some evidence that food allergens may play a role in triggering atopic eczema and that dairy products or eggs cause exacerbation of eczema in a few infants under 12 months of age.

FURTHER READING

Batchelor JM, Grindlay DJ, Williams HC. What’s new in atopic eczema? An analysis of systematic reviews published in 2008 and 2009. Clin Exp Dermatol 2010; 35:823–828.

Bieber T. Mechanisms of disease: atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:1483–1494.

Brown SJ, McLean WH. Eczema genetics: current state of knowledge and future goals. J Invest Dermatol 2009; 129:543–552.

Irvine AD et al. Filaggrin mutations associated with skin and allergic diseases. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:1315–1327.

Clinical features

Atopic eczema can present as a number of distinct morphological variants. The commonest presentation is of itchy erythematous scaly patches, especially in the flexures such as in front of the elbows and ankles, behind the knees (Fig. 24.10) and around the neck. In infants eczema often starts on the face before spreading to the body. Very acute lesions may weep or exude and can show small vesicles. Scratching can produce excoriations, and repeated rubbing produces skin thickening (lichenification) with exaggerated skin markings.

In people with pigmented skin, eczema often shows a reverse pattern of extensor involvement. Also the eczema may be papular or follicular in nature, and lichenification is common. A final problem in pigmented skin is of postinflammatory hyper- or hypopigmentation which is often very slow to fade after control of the eczema.

Associated features

In some atopic individuals, the skin of the upper arms and thighs may feel roughened due to follicular hyperkeratosis (‘keratosis pilaris’). The palms may show very prominent skin creases (‘hyperlinear palms’). There may be an associated dry ‘fish-like’ scaling of the skin which is non-inflammatory and often prominent on the lower legs (‘ichthyosis vulgaris’).

Complications

Broken skin commonly becomes secondarily infected by bacteria, usually Staphylococcus aureus, although streptococci can colonize eczema, especially in macerated flexural areas such as the neck and groin. Clinically, this infection may appear as crusted, weeping impetigo-like lesions. Cutaneous viral infections (e.g. viral warts and molluscum) are often widespread in atopic eczema and are probably spread by scratching. HSV can cause a widespread eruption called eczema herpeticum (Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption. This can occasionally be a very severe infection and rarely can be fatal. It appears as multiple small blisters or punched-out crusted lesions associated with malaise and pyrexia, and needs rapid treatment with oral (or intravenous if severe) aciclovir. Ocular complications of atopic eczema include conjunctival irritation and less commonly keratoconjunctivitis and cataract. Retarded growth may be seen in children with chronic severe eczema; it is due to the disease itself and not the use of topical steroids.

Investigations

The diagnosis of atopic eczema is clinical. However atopy is characterized by high serum IgE levels or high specific IgE levels to certain ingested or inhaled antigens and a blood eosinophilia in about 80% of cases.

Prognosis

The majority (80–90%) of children with early-onset atopic eczema will spontaneously improve and ‘clear’ before the teenage years, 50% being clear by the age of 6. A few will get a recurrence as adults, even if just as hand eczema. However, if the onset of eczema is late in childhood or in adulthood, the disorder follows a more chronic remitting/relapsing course.

Treatment (Box 24.2)

General measures

These include avoiding known irritants (especially soaps or furry animals), wearing cotton clothes, and not getting too hot. Manipulating the diet (e.g. dairy-free diet) is rarely beneficial except in a few children, especially those under 12 months of age where cows milk and egg allergy are common. Any change in diet should be made under supervision, especially with growing children who may need supplements such as calcium.

Topical therapies

Topical therapies (p. 1235) are sufficient to control atopic eczema in most people. The ‘triple’ combination of topical steroid, frequent emollients (see Table 24.18) and bath oil and soap substitute (e.g. aqueous cream) helps.

Table 24.18 Emollients commonly used in the UK

| Greasy emollients | Lighter creams |

|---|---|

Epaderm ointmenta |

E45 creama |

Oily cream |

Diprobase creama |

Unguentum Mercka |

Aveeno creama |

50:50 white soft paraffin/liquid paraffin |

Aqueous cream |

Written information or a practical demonstration of how to apply these treatments improves compliance.

Use of topical steroids. Unjustified fear about the dangers of topical steroids has often led to undertreatment of eczema. Providing appropriate-strength steroid preparations are used for the right body site, these compounds can be used quite safely on a long-term intermittent basis. Topical steroids can be divided into five groups depending on their potency (Table 24.4).

Table 24.4 Classification of topical steroids by potency

Very potent |

0.05% clobetasol propionate |

0.3% diflucortolone valerate |

|

Potent |

0.1% betamethasone valerate |

0.025% fluocinolone acetonide |

|

Diluted potent |

0.025% betamethasone valerate |

0.00 625% fluocinolone acetonide |

|

Moderately potent |

0.05% clobetasone butyrate |

0.05% alclometasone dipropionate |

|

Mild |

2.5% hydrocortisone |

1% hydrocortisone |

The following guidelines should be followed to allow their safe use in common chronic inflammatory skin conditions.

The face should be treated only with mild steroids.

The face should be treated only with mild steroids.

In adults the body should be treated with either mild, moderately potent or diluted potent steroids.

In adults the body should be treated with either mild, moderately potent or diluted potent steroids.

In young children the body should be treated with mild and moderately potent steroids.

In young children the body should be treated with mild and moderately potent steroids.

Potent steroids are used for short courses (7–10 days).

Potent steroids are used for short courses (7–10 days).

Treatment of the palms and soles (but not the dorsal surfaces) may require potent or very potent steroids as the skin is much thicker.

Treatment of the palms and soles (but not the dorsal surfaces) may require potent or very potent steroids as the skin is much thicker.

Regular use of emollients may lessen the need for steroid use.

Regular use of emollients may lessen the need for steroid use.

Only use steroids on inflamed skin. Do not use as an emollient.

Only use steroids on inflamed skin. Do not use as an emollient.

‘Apply sparingly’ means use sufficient to leave a glistening surface to the skin after application.

‘Apply sparingly’ means use sufficient to leave a glistening surface to the skin after application.

Use weaker steroid preparations in flexures (e.g. the groin, and under breasts) as apposition of the skin at these sites tends to occlude the treatment and increase absorption.

Use weaker steroid preparations in flexures (e.g. the groin, and under breasts) as apposition of the skin at these sites tends to occlude the treatment and increase absorption.

Topical immunomodulators

Tacrolimus ointment (0.1% and 0.03%) and the less potent pimecrolimus cream can be used for atopic eczema in patients over 2 years old. They have the advantage over potent steroids of not causing skin atrophy and are thus very useful for treating sensitive areas such as the face and eyelids. They can be irritant when first used (although this settles with continued use) and 9% of patients develop flushing after alcohol. The long-term side-effects remain unknown but there have been no major problems. They do not work so well on lichenified eczema, probably due to poor absorption. Current advice is to avoid vaccinations and sun exposure when using these agents. The milder potency steroid creams are still first-line therapy but tacrolimus is a useful alternative to excessive use of potent steroids. Tacrolimus ointment is also used twice weekly to prevent eczema flares.

Antibiotics

These are needed for bacterial infection and are usually given orally for 7–10 days. Flucloxacillin (500 mg four times daily) is effective against Staphylococcus and phenoxymethylpenicillin (500 mg four times daily) acts against Streptococcus. Erythromycin (500 mg four times daily) is useful if there is allergy to penicillin. Topical antiseptics are used in cases of recurrent infection but they can be irritant. They are usually added to the bath water rather than applied directly to the skin.

Sedating antihistamines

These (e.g. oral hydroxyzine hydrochloride 10–25 mg) are useful at night-time.

Bandaging

Paste bandaging can be useful for resistant or lichenified eczema of the limbs. It helps absorption of treatment and acts as a barrier to prevent scratching. Wet tubular gauze bandages are used for inpatient therapy but are difficult and time-consuming to use at home.

Second-line agents

These are used in severe non-responsive cases, especially if the eczema is significantly interfering with an individual’s life (e.g. growth, sleeping, schoolwork or job). Ultraviolet phototherapy (see p. 1215), prednisolone (initial doses up to 30 mg daily), ciclosporin (3–5 mg/kg daily) and azathioprine (1–3 mg/kg daily) (in chapter 6) can all be effective treatments. However they all have side-effects and the risk/benefit ratio must be openly discussed with the patient before they are used.

Use of ciclosporin. Ciclosporin is a selective immunosuppressant that inhibits interleukin-2 production by T lymphocytes. A large number of other drugs interact with ciclosporin (e.g. erythromycin, NSAIDs) and should be avoided. Renal damage and hypertension are the two most serious side-effects so blood pressure, serum creatinine and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) should be measured every 6–12 weeks. Renal damage becomes increasingly common with time and tends to be dose-dependent but is mostly reversible. Hypertrichosis, paraesthesia and nausea are less serious side-effects. Pregnancy should be avoided.

SIGNIFICANT WEBSITE

Atopic eczema in children – Clinical guidelines: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG 57

Discoid eczema (nummular eczema)

Discoid eczema is a morphological variant of eczema characterized by well-demarcated scaly patches, especially on the limbs, and this can be confused sometimes with psoriasis. It is commoner in adults and can occur in both atopic and non-atopic individuals. It tends to follow an acute/sub-acute course rather than a chronic pattern. There is often an infective component (Staphylococcus aureus).

Hand eczema

Eczema may be confined to the hands (and feet). It can present with:

itchy vesicles or blisters on the palm and along the sides of the fingers (also called ‘pompholyx’) (Fig. 24.11)

itchy vesicles or blisters on the palm and along the sides of the fingers (also called ‘pompholyx’) (Fig. 24.11)

a diffuse erythematous scaling and hyperkeratosis of the palms

a diffuse erythematous scaling and hyperkeratosis of the palms

Hand eczema is not unusual in atopics but more frequently occurs in non-atopic individuals, and a cause is not always found. A history of contact with irritants (e.g. detergents, chemicals) and an occupational history should be sought, especially in finger-tip eczema. Patch testing for specific allergic or contact eczema should always be performed as up to 10% of individuals with hand eczema will show a positive test. Finally, look for evidence of fungal infection as this can occasionally induce a secondary pompholyx of the hands or feet (a so-called ‘id reaction’).

Seborrhoeic eczema

Aetiology

Overgrowth of Pityrosporum ovale (also called Malassezia furfur in its hyphal form) together with a strong cutaneous immune response to this yeast produces the characteristic inflammation and scaling of seborrhoeic eczema. The condition is more common in Parkinsonism as well as in HIV disease.

Clinical features

Seborrhoeic eczema affects body sites rich in sebaceous glands, although these do not appear to be causal. Three age groups are affected:

In neonates it is common and presents as yellowish thick crusts on the scalp (cradle cap). A more widespread erythematous, scaly rash can be seen over the trunk, especially affecting the nappy area. Unlike with atopic eczema, the child is normally unbothered as there is little associated pruritus. The rash normally improves spontaneously after a few weeks.

In neonates it is common and presents as yellowish thick crusts on the scalp (cradle cap). A more widespread erythematous, scaly rash can be seen over the trunk, especially affecting the nappy area. Unlike with atopic eczema, the child is normally unbothered as there is little associated pruritus. The rash normally improves spontaneously after a few weeks.

In young adults (especially males) it occurs in 1–3% of the population. The rash is more persistent and presents as an erythematous scaling along the sides of the nose (Fig. 24.12), in the eyebrows, around the eyes and extending into the scalp (which shows marked dandruff). It may affect the skin over the sternum, axillae and groins, and the glans penis. A blepharitis may also be present.

In young adults (especially males) it occurs in 1–3% of the population. The rash is more persistent and presents as an erythematous scaling along the sides of the nose (Fig. 24.12), in the eyebrows, around the eyes and extending into the scalp (which shows marked dandruff). It may affect the skin over the sternum, axillae and groins, and the glans penis. A blepharitis may also be present.

In elderly people seborrhoeic eczema can be more severe and progress to involve large areas of the body and even cause erythroderma.

In elderly people seborrhoeic eczema can be more severe and progress to involve large areas of the body and even cause erythroderma.

Treatment

This is suppressive rather than curative. A combination of a mild steroid ointment (e.g. 1% hydrocortisone applied twice daily) and a topical antifungal cream (e.g. miconazole cream applied twice daily) will help to control the eruption. Topical 0.1% tacrolimus ointment or pimecrolimus cream can also be used.

Ketoconazole shampoo and arachis oil are useful for the scalp. Emollients and a soap substitute are useful adjuncts.

Venous eczema (varicose eczema, gravitational eczema)

This type of eczema occurs on the lower legs due to chronic venous hypertension (usually of more than 2 years’ duration) (see p. 1226).

Clinical features

Venous eczema tends to occur in older people, especially women. It usually appears on the lower legs around the ankles. There may be a past history of venous thrombosis or previous surgery for varicose veins. Brownish pigmentation (haemosiderin) may be seen in the skin and a venous leg ulcer or varicose veins may be present.

Superimposed contact eczema is common in venous eczema patients, especially when there have been chronic venous leg ulcers. This is usually due to an allergic reaction to topical therapies or skin dressings. Patch testing should always be done in treatment-resistant cases.

Treatment

This should include emollients and a moderately potent topical steroid. Support stockings or compression bandages, together with leg elevation, help decrease the underlying venous hypertension (p. 1226).

Asteatotic eczema (winter eczema, eczema craquelé, senile eczema)

This is a dry plate-like cracking of the skin with a red, eczematous component, which occurs in elderly people. It occurs predominantly on the lower legs and the backs of the hands, especially in winter. The exact cause is unknown but the repeated use of soaps in the elderly with the loss of the stratum corneum lipids with age is probably involved. Rarely asteatotic eczema can be the presenting sign of hypothyroidism or can follow the commencement of diuretic therapy.

Allergic contact and irritant contact eczema

If the eczema is in an unusual or localized distribution (Fig. 24.13), especially if there is no personal or family history of atopic disease, one of a variety of environmental agents (exogenous eczema) is the likely cause. A history of an exacerbation of eczema at the workplace is also suggestive (‘occupational dermatitis’). There are two possible mechanisms: direct irritation or an allergic reaction (type IV delayed hypersensitivity). A detailed history of occupation, hobbies, cosmetic products, clothing and contact with chemicals is necessary.

Allergic contact eczema occurs after repeated exposure to a chemical substance but only in those people who are susceptible to develop an allergic reaction. It is common, occurring in up to 4% of some populations. Many substances can cause this type of reaction but the commoner culprits are nickel (in costume jewellery and buckles); chromate (in cement); latex (in surgical gloves); perfume (in cosmetics and air fresheners); and plants (such as primula or compositae). A good history is necessary and if suspicious, patch testing should be arranged to prove any allergy.

Irritant contact eczema can occur in any individual. It often occurs on the hands after repeated exposures to irritants such as detergents, soaps or bleach. It is therefore common in housewives, cleaners, hairdressers, mechanics and nurses.

Lichen simplex/nodular prurigo (neurodermatitis)

These terms are applied to a disorder characterized by chronic scratching or rubbing in the absence of an underlying dermatosis. They are more common in Asians and also in black African and Oriental patients.

Lichen simplex appears as thickened, scaly and hyperpigmented areas of lichenification (Fig. 24.14). It starts with intense itching that becomes tender with increased rubbing or scratching, and a self-perpetuating ‘itch-scratch cycle’ develops. It is rare before adolescence and is commoner in females. Common sites are the nape of the neck, the lateral calves, the upper thighs, the upper back and the scrotum or vulva but any accessible site can be affected.

Nodular prurigo is a different pattern of cutaneous response to scratching, rubbing or picking. Individual, itchy papules and domed nodules appear, especially on the upper trunk and the extensor surfaces of the limbs. They show significant surface damage from scratching. This is a chronic unremitting condition, which is often resistant to treatment.

These two conditions overlap, with some patients showing mixed features. Atopic individuals seem predisposed to develop these conditions (in the absence of obviously active eczema). However, they can occur in non-atopics. Emotional stress appears to be a contributory factor in many of these patients (hence the name neurodermatitis).

The diagnosis is made by exclusion of other pathologies and may require a skin biopsy. General medical causes of pruritus should be excluded including HIV infection (p. 154 and p. 177). In the elderly, nodular prurigo may be an early sign of bullous pemphigoid, before the more typical blistering phase has appeared.

Treatment

Treatment is often difficult as symptoms can be intractable. Very potent topical steroids (e.g. 0.05% clobetasol propionate) with occlusive tar bandaging may sometimes help. Intralesional steroids can also be useful but there is a risk of atrophy. For resistant cases (especially of prurigo lesions) topical doxepin, phototherapy (p. 1215), low-dose oral amitriptyline (50 mg nightly) and ciclosporin (3–5 mg/kg per day) are used.

Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a common papulo-squamous disorder affecting 2% of the population and is characterized by well-demarcated, red scaly plaques. The skin becomes inflamed and hyperproliferates at about ten times the normal rate. It affects males and females equally and can affect all races. The age of onset occurs in two peaks. Early onset (age 16–22) is commoner and is often associated with a positive family history. Late-onset disease peaks at age 55–60 years.

Aetiology

The condition appears to be polygenic but is also dependent on certain environmental triggers. Twin studies show 73% concordance in monozygotic twins compared with 20% in dizygotic pairs. Nine genetic psoriasis susceptibility loci have been identified (PSORS 1–9). Some loci seem shared with other diseases: atopic eczema (1q21, 3q21, 17q25, 20p), rheumatoid arthritis (3q21, 17q24–25) and Crohn’s disease (16). The most studied locus, PSORS1 (which accounts for 35–50% of the heritable component), lies in the MHC region of chromosome 6 (HLA Cw6).

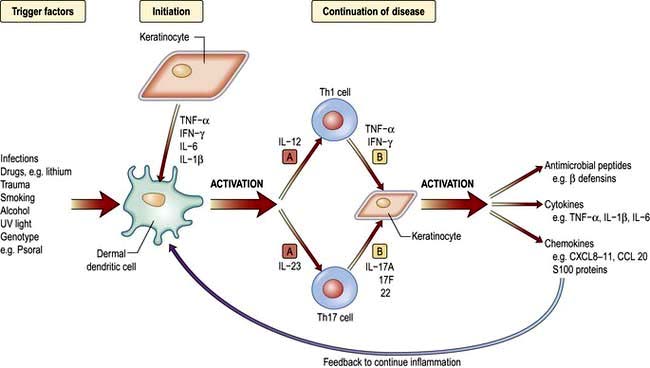

The exact aetiology is unknown but evidence suggests that psoriasis is a T-lymphocyte-driven disorder to an unidentified antigen(s). Figure 24.15 shows the trigger factors that activate the antigen-presenting cell (dendritic/Langerhans). This activation results in upregulation of Th1-type T cell cytokines, e.g. interferon-γ, interleukins (IL-1, -2, -8), growth factors (TGF-α and TNF-α) and adhesion molecules (ICAM-1). The pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α is also produced by keratinocytes and this may be involved in both initiation and maintenance of psoriatic lesions. TNF-α blocking drugs have proved highly effective in treatment (Fig. 24.15). IL-17 and IL-22 are thought to work together to produce clinical psoriasis (see p. 1210).

Figure 24.15 Pathogenesis or psoriasis. Trigger factors activate the dendritic cell which, in turn, Th1 and Th17 T cell via IL-12 and IL-23. These T cells secrete mediators to activate keratinocytes to produce antimicrobial peptides, cytokines and chemokines. These maintain the inflammation and feedback to activate the dendritic cell. [A], Site of action of ustekinumab, brikinumab. [B], Infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab.

Pathology

Skin biopsy shows epidermal acanthosis and parakeratosis, reflecting the increase in skin turnover, and the granular layer is often absent. Polymorphonuclear abscesses may be seen in the upper epidermis. The epidermal rete ridges appear elongated and clubbed as they fold down into the dermis. Dermal changes include capillary dilation surrounded by a mixed neutrophilic and lymphohistiocytic perivascular infiltrate.

Clinical features

Psoriasis can present in different clinical patterns but there is overlap between the different forms. Certain drugs can make psoriasis worse, notably lithium, antimalarials and rarely beta-blockers.

Chronic plaque psoriasis

This is the ‘common’ type of psoriasis. It is characterized by pinkish red scaly plaques, with a silver scale seen, especially on extensor surfaces such as knees (Fig. 24.16a) and elbows. The lower back, ears and scalp are also commonly involved. New plaques of psoriasis occur at sites of skin trauma – the so-called ‘Köbner phenomenon’. The lesions can become itchy or sore.

Flexural psoriasis

This tends to occur in later life. It is characterized by well-demarcated, red glazed plaques confined to flexures such as the groin, natal cleft and sub-mammary area. As these sites are apposed, there is rarely any scaling. In the absence of psoriasis elsewhere the rash is often misdiagnosed as candida intertrigo but the latter will normally show satellite lesions.

Guttate psoriasis

‘Raindrop-like’ psoriasis is a variant most commonly seen in children and young adults (Fig. 24.16b). An explosive eruption of very small circular or oval plaques appears over the trunk about 2 weeks after a streptococcal sore throat.

Erythrodermic and pustular psoriasis

These are the most severe types of psoriasis reflecting a widespread intense inflammation of the skin. They can occur together (‘Von Zumbusch’ psoriasis) and may be associated with malaise, pyrexia and circulatory disturbance. This form can be life-threatening. The pustules are not infected but are sterile collections of inflammatory cells. There is also a more localized variant of pustular psoriasis that confines itself to the hands and feet (palmo-plantar psoriasis) but is not associated with severe systemic symptoms. This latter type is more common in heavy cigarette smokers.

Associated features

Nails. Up to 50% of individuals with psoriasis develop nail changes (Fig. 24.17) and rarely these can precede the onset of skin disease. There are five types of nail change: (a) pitting of the nail plate; (b) distal separation of the nail plate (onycholysis); (c) yellow-brown discoloration; (d) subungual hyperkeratosis; (e) rarely a damaged nail matrix and lost nail plate. Treatment of nail dystrophy is very difficult.

Figure 24.17 Psoriasis of the nail – yellowish brown discoloration and distal nail plate separation (onycholysis).

Arthritis. Some 5–10% of individuals develop psoriatic arthritis and most of these will have nail changes (p. 602).

Treatment

This is concerned with control rather than cure and should be tailored to the patient’s wishes (Box 24.3). Severe cases may require hospitalization.

Chronic plaque psoriasis: emollients should always be used to hydrate the skin. Mild to moderate topical steroids, synthetic vitamin D3 analogues (e.g. calcipotriol, calcitriol, tacalcitol), 0.05% tazarotene (a retinoid) and purified coal tar are the most popular therapies. Salicylic acid can be a useful adjunct. All should be applied once to twice daily to palpable lesions. Once lesions have flattened, therapy can be discontinued. Tazarotene and calcipotriol can be very irritant (calcitriol somewhat less so) so they are often used in combination with steroid creams. Vitamin D analogues should be used with caution in extensive psoriasis because there is a risk of hypercalcaemia if greater than 100 g is used per week.

Dithranol causes staining of the skin and clothing and is more difficult to use at home on a regular basis. It is normally applied for 20–60 min and then washed off. It must be applied carefully to the lesions as it causes irritation to normal skin. Dithranol is more likely to induce remission than other therapies but is being recommended less because of poor compliance.

Topical therapies are sometimes used in combination with UVB or PUVA. The ‘Goeckerman regimen’ consists of tar and UVB; the ‘Ingram regimen’ consists of dithranol and UVB. The latter has similar results to oral PUVA in terms of clearance rates and lengths of remission – approximately 75% in 6 weeks.

Flexural psoriasis is usually treated with mild steroid and/or tar topical creams. Calcitriol and 0.1% tacrolimus ointment are also useful for treating flexural (facial and genital) psoriasis where irritation can be a problem.

Guttate psoriasis is usually treated with topical therapies and/or UVB phototherapy.

Palmo-plantar psoriasis is treated with very potent topical steroids, coal tar paste or local hand and foot PUVA.

Systemic therapy. Agents such as methotrexate, acitretin, mycophenolate, ciclosporin or hydroxycarbamide (hydroxy-urea) are used for resistant cases.

Erythrodermic psoriasis also requires systemic therapy (but not phototherapy) as well as general supportive measures (p. 1215).

All systemic treatments must be monitored for toxicity.

Use of methotrexate. Methotrexate is normally given once weekly. Some patients experience severe nausea on the day they take it which can be lessened by folic acid therapy. Both men and women should avoid conception during and for 3 months after therapy. Some patients are allergic to methotrexate and develop a pyrexia and mouth ulceration. Regular blood tests need to be done to monitor for bone marrow suppression and liver damage. Alcohol must be avoided as this increases the risk of hepatotoxicity. NSAIDs should also be avoided as these inhibit excretion. Lower doses should be used in the elderly. Long-term use causes hepatic fibrosis, and regular monitoring of patients’ serum procollagen III peptide level or elastography (p. 327) is being used to assess fibrosis development. People with concomitant psoriatic arthritis are more likely to develop pulmonary fibrosis.

Cytokine modulators (see Fig. 24.15)

Cytokine modulators are at present only used in patients who have severe disease who have failed (or cannot tolerate due to toxicity) conventional systemic treatments.

Etanercept, infliximab and adalimumab (TNF-α blockers) are highly effective and tend to be used first-line in the UK as they have the longest safety data.

Etanercept, infliximab and adalimumab (TNF-α blockers) are highly effective and tend to be used first-line in the UK as they have the longest safety data.

Ustekinumab (a human interleukin-12/23 monoclonal antibody) is highly effective. Its safety data is limited so it is most commonly used in those patients that fail a TNF-α blocker.