Erythema nodosum

Erythema nodosum has a number of underlying causes (Table 24.9). It presents as painful or tender dusky blue-red nodules, commonly over the shins or lower limbs, which fade over 2–3 weeks leaving a bruised appearance (see Fig. 24.39). It is most common in young adults, especially females. It may be associated with arthralgia, malaise and fever. Inflammation occurs in the dermis and the subcutaneous layer (panniculitis).

Table 24.9 Causes of erythema nodosum

Streptococcal infectiona

Drugs (e.g. sulphonamides, oral contraceptive)

Sarcoidosisa

Idiopathica

Bacterial gastroenteritides, e.g. Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia

Fungal infection (histoplasmosis, blastomycosis)

Tuberculosis

Leprosy

Inflammatory bowel disease

Chlamydia infection

|

Treatment is of the symptoms with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (avoid in pregnancy), light compression bandaging and bed rest, as the condition resolves spontaneously. The underlying cause should be treated. In very persistent cases dapsone (100 mg daily), colchicine (500 µg twice daily) or prednisolone (up to 30 mg daily) can be useful.

Erythema multiforme

Erythema multiforme (EM) is a hypersensitivity rash of acute onset frequently caused by infection or drugs. A cell-mediated cutaneous lymphocytotoxic response is present.

In 50% of cases, the cause is not found but the following should be considered:

Herpes simplex virus (the most common identifiable cause)

Herpes simplex virus (the most common identifiable cause)

Other viral infections (e.g. Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), orf)

Other viral infections (e.g. Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), orf)

Drugs (e.g. sulphonamide, anticonvulsants)

Drugs (e.g. sulphonamide, anticonvulsants)

Mycoplasma infection

Mycoplasma infection

Autoimmune rheumatic disease (e.g. SLE, polyarteritis nodosa)

Autoimmune rheumatic disease (e.g. SLE, polyarteritis nodosa)

HIV infection

HIV infection

Wegener’s granulomatosis

Wegener’s granulomatosis

Carcinoma, lymphoma.

Carcinoma, lymphoma.

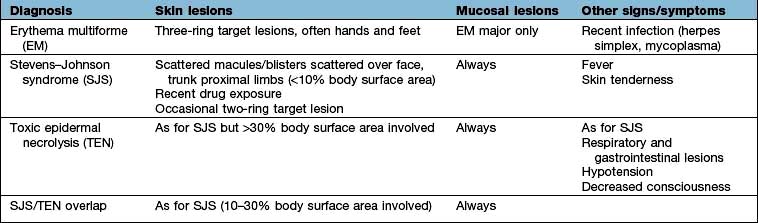

Clinically the lesions can be erythematous, polycyclic, annular or show concentric rings (‘target lesions’) (Fig. 24.22). Frank blistering is not uncommon. The rash tends to be symmetrical and commonly affects the limbs, especially the hands and feet where palms and soles may be involved. Occasionally, there is severe mucosal involvement leading to necrotic ulcers of the mouth and genitalia, and a conjunctivitis (‘EM major’ – not to be confused with Stevens–Johnson syndrome – see Table 24.10).

The term ‘EM minor’ is used for cases without mucosal involvement.

Erythema multiforme usually resolves in 2–4 weeks. Rarely, recurrent erythema multiforme can occur and this is triggered by herpes simplex infection in 80% of cases.

Treatment

This is symptomatic and involves treating the underlying cause. Some advocate the use of oral steroids in severe mucosal disease but this remains controversial.

Recurrent erythema multiforme can be treated with prophylactic oral aciclovir (200 mg twice daily) even if no cause has been found, as 80% of cases appear to be driven by herpes simplex virus. In resistant cases, azathioprine (1–2 mg/kg daily) is used.

Pyoderma gangrenosum

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a condition of unknown aetiology that presents with erythematous nodules or pustules which frequently ulcerate (Fig. 24.23). The ulcers can be large and grow at an alarming speed. The ulcer has a typical bluish black (‘gangrenous’) undermined edge and a purulent surface (‘pyoderma’). There may be an associated pyrexia and malaise. Biopsy through the ulcer edge shows an intense neutrophilic infiltrate and occasionally a vasculitis but the diagnosis depends mostly on the clinical appearance. The main causes are:

Inflammatory bowel disease

Inflammatory bowel disease

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis

Myeloma, monoclonal gammopathy, leukaemia, lymphoma

Myeloma, monoclonal gammopathy, leukaemia, lymphoma

Liver disease (e.g. primary biliary cirrhosis)

Liver disease (e.g. primary biliary cirrhosis)

Idiopathic (>20% in some series).

Idiopathic (>20% in some series).

Treatment

This is with very potent topical steroids or 0.1% tacrolimus ointment. High-dose oral steroids may be needed to prevent rapidly progressive ulceration. Oral dapsone and minocycline are also used. Other immunosuppressants, such as ciclosporin, are useful in resistant cases. The underlying cause should be treated.

Acanthosis nigricans

Acanthosis nigricans presents as thickened, hyperpigmented skin predominantly of the flexures (Fig. 24.24). It can appear warty or velvety when advanced. In early life it is seen in obese individuals who have very high levels of insulin owing to insulin resistance (and this is sometimes termed ‘pseudo-acanthosis nigricans’). In older people it normally reflects an underlying malignancy (especially gastrointestinal tumours). Rarely it is associated with hyperandrogenism in females.

Treatment

Topical or oral retinoids (0.5 mg/kg per day) may help (p. 1213), and weight loss is advised in the obese. Any underlying malignancy should be treated.

Dermatomyositis (see also p. 540)

The rash is distinctive and often photosensitive. Facial erythema and a magenta-coloured rash around the eyes with associated oedema are usually present. Bluish red nodules or plaques may be present over the knuckles (Gottron’s papules) and extensor surfaces. The nail folds are frequently ragged with dilated capillaries. The diagnosis is made from the clinical appearance, muscle biopsy, electromyography (EMG) and a serum creatine phosphokinase. Skin biopsy is not diagnostic.

There is a childhood form, which usually occurs before the age of 10 and which eventually resolves. This type is associated with calcinosis in the skin, weak muscles and contractures. Life-threatening bowel infarction can also occur in the childhood form. The adult form usually occurs after the age of 40. Some cases are associated with an underlying malignancy whereas some are associated with other autoimmune rheumatic diseases. This latter group may overlap with scleroderma and lupus erythematosus.

Treatment

Skin disease may respond to sunscreens and hydroxychloroquine (200 mg twice daily) as well as immunosuppressants, e.g. prednisolone, azathioprine or ciclosporin.

Scleroderma

The term scleroderma (see also p. 538) refers to a thickening or hardening of the skin owing to abnormal dermal collagen. It is not a diagnostic entity in itself. Systemic sclerosis and morphea both show sclerodermatous changes but are separate conditions.

Systemic sclerosis (often called scleroderma) has cutaneous and systemic features and is discussed fully on page 538.

Morphea is confined to the skin and usually presents in children or young adults. It is commoner in females and the cause is unknown. Lesions are usually on the trunk and appear as bluish red plaques which progress to induration and then central white atrophy. A linear variant exists in childhood which is more severe as it can cause atrophy of underlying deep tissues and thus cause unequal limb growth or scarring alopecia.

Rarely sclerodermatous skin changes may be seen in Lyme disease (acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans), chronic graft-versus-host disease, polyvinyl chloride disease, eosinophilic myalgia syndrome (due to tryptophan therapy) and bleomycin therapy.

Lupus erythematosus (LE)

There are three clinical variants to this disease but some patients may show features of more than one type.

Chronic discoid lupus erythematosus (CDLE)

Chronic discoid lupus erythematosus (CDLE)

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE)

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE)

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

The aetiology is unknown but variable autoantibodies may be found in all types, suggesting that it is an automimmune disorder. Very rarely it can be induced by certain drugs such as phenothiazines, hydralazine, methyldopa, isoniazid, tetracycline, mesalazine and penicillin.

Chronic discoid lupus erythematosus (CDLE)

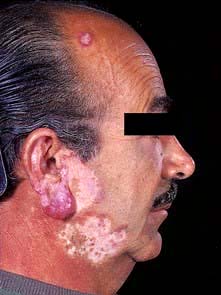

CDLE is the most common type of LE seen by dermatologists and more frequently affects females. Clinically it presents with fixed erythematous, scaly, atrophic plaques with telangiectasia, especially on the face or other sun-exposed sites (Fig. 24.25). Hypopigmentation is common and follicular plugging may be apparent. Scalp involvement may lead to a scarring alopecia. Oral involvement (erythematous patches or ulceration) occurs in 25% of cases.

CDLE may be triggered and exacerbated by UV exposure. A few patients may also suffer with Raynaud’s phenomenon or unusual chilblain-like lesions (chilblain lupus). Only 5% of cases will go on to develop SLE but this is more common in children. Serum anti-nuclear factor (ANF) is positive in 30% of cases.

Skin biopsy shows a dense patchy, dermal cellular infiltrate (mostly T cells) which often is centred on appendages. Epidermal basal layer damage, follicular plugging and hyperkeratosis may be present. Direct immunofluorescence studies of lesional skin may show the presence of IgM and C3 in a granular band at the dermoepidermal junction (‘lupus band’).

Treatment

First-line therapy is with sunscreens and potent topical steroids. Certain oral antimalarials (hydroxychloroquine 100–200 mg twice daily and mepacrine 100 mg daily) can prove very useful and are generally safe for long-term intermittent use. Oral prednisolone is beneficial but its use is limited by its side-effect profile. Azathioprine, retinoids, ciclosporin and thalidomide can be useful in resistant cases.

Prognosis

The disease is usually chronic although it often fluctuates in severity. CDLE remains confined to the skin in most patients and it will eventually go into remission in up to 50% of cases (after many years).

Subacute lupus erythematosus (SCLE)

SCLE is a rare cutaneous variant of LE. It presents with widespread indurated, sometimes urticated erythematous lesions, often on the upper trunk. The lesions can also be annular. Photosensitivity is often a prominent feature. Complications, such as arthralgia and mouth ulceration, are seen but significant organ involvement is rare. ANF and extractable nuclear antibodies (anti-Ro and anti-La) are usually positive (see p. 537).

Treatment is with oral dapsone, antimalarials or systemic immunosuppression (prednisolone and ciclosporin).

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

(see also p. 535)

The cutaneous involvement of SLE is one of the minor problems of the disease but it may be the presenting feature.

Features include macular erythema over the cheeks, nose and forehead (‘butterfly rash’ – Fig. 24.26). Palmar erythema, dilated nail-fold capillaries, splinter haemorrhages and digital infarcts of the finger tips may also be seen but are not always noticed by the patient. Joint swellings, livedo reticularis and purpura are occasionally seen. Rarely SLE can be complicated by an atypical erythema multiforme-like rash (‘Rowell’s syndrome’).

Treatment (p. 537) is usually managed by a rheumatologist.

FURTHER READING

Obermoser G, Sontheimer RD, Zelger B. Overview of common, rare and atypical manifestations of cutaneous lupus erythematosus and histopathological correlates. Lupus 2010; 19:1050–1070.

Pruritus

The pathophysiology of pruritus (itch) is poorly understood but may be due to peripheral mechanisms (as in skin disease), central or neuropathic mechanisms (as in multiple sclerosis), neurogenic (as in cholestasis/µ-opioid receptor stimulation) or psychogenic mechanisms (e.g. parasitophobia). Evidence suggests that low stimulation of unmyelinated C-fibres in the skin is associated with the sensation of itch (high stimulation produces pain). Histamine, tachykinins (e.g. substance P) and cytokines (e.g. interleukin-2) may also play a role peripherally in the skin. The major nerve pathways for itch and the influence of the central nervous system are not well characterized but opioid µ-receptor-dependent processes can regulate the perception and intensity of itch.

Pruritus (see p. 1207, lichen simplex, nodular prurigo/neurodermatitis) in the absence of a demonstrable rash can be caused by a number of different medical problems (Table 24.11).

Table 24.11 Medical conditions associated with pruritus

Iron deficiency anaemia

Internal malignancy (especially lymphoma)

Diabetes mellitus

Chronic kidney disease

Chronic liver disease (especially primary biliary cirrhosis)

Thyroid disease

HIV infection

Polycythaemia vera

|

Asteatotic eczema and cholinergic urticaria are common causes of pruritus where the rash is often missed. The term idiopathic pruritus or ‘senile’ pruritus probably overlaps with asteatotic eczema and this is common in the elderly.

Treatment involves avoiding soaps and symptomatic measures (as for asteatotic eczema). Phototherapy, low-dose amitriptyline or gabapentin may help intractable cases. Underlying medical problems should be treated.

Sarcoidosis

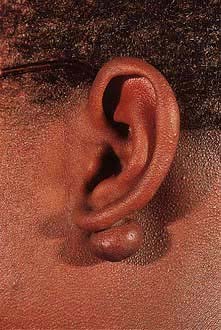

Sarcoidosis (see also p. 845) is a multisystem granulomatous disorder of unknown aetiology. It may present as reddish brown dermal papules and nodules, especially around the eyelid margins and the rim of the nostrils. More polymorphic lesions (papules, nodules and plaques) may appear on the body. It is most common in black Africans where it is often accompanied by hypo- or hyperpigmentation. Rarely it presents with a bluish red infiltrate or swelling, especially of the nose or ears, called lupus pernio. Both these types of lesion are to be seen anywhere on the body but are common on the face. Erythema nodosum (p. 1216) of the shins is sometimes seen in acute-onset sarcoidosis. Erythema nodosum is an immunological reaction and not due to sarcoid tissue infiltration. Swollen fingers from a dactylitis may also be present. Whilst sarcoidosis may be confined to the skin, all patients should be investigated for evidence of systemic disease (p. 847).

Treatment of cutaneous lesions includes very potent topical steroids (0.05% clobetasol propionate), intralesional steroids, oral steroids and occasionally methotrexate or antimalarials.

FURTHER READING

Badgwell C, Rosen T. Cutaneous sarcoidosis therapy updated. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 56:69–83.

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (von Recklinghausen’s disease)

Type 1 neurofibromatosis is an autosomal dominant condition with high levels of penetrance. It often presents in childhood with a variety of cutaneous features. Many cases are new mutations in the NF1 gene. Early signs include café-au-lait spots (brown macules, >2.5 cm in diameter and more than five lesions) and axillary freckling. Lisch nodules (hyperpigmented iris hamartomas) may be seen in the eyes by slit lamp examination. Learning difficulties and skeletal dysplasia occur. Later on, fleshy skin tags and deeper soft tumours (neurofibromas) appear and they can progress to completely cover the skin causing significant cosmetic disability. A number of endocrine disorders are rarely associated including phaeochromocytoma, acromegaly and Addison’s disease.

Tuberous sclerosis (epiloia)

The tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is an autosomal dominant condition of variable severity which may not present until later childhood. It is characterized by a variety of hamartomatous growths. The three cardinal features are (1) mental retardation, (2) epilepsy and (3) cutaneous abnormalities – but not all have to be present. In most cases, it is due to a mutation in either the TSC1 gene (encodes hamartin) or the TSC2 gene (encodes tuberin). Genetic testing is available but the diagnosis still remains clinical, requiring two major features or one major and two minor features. The skin signs include:

Adenoma sebaceum (reddish papules/fibromas around the nose)

Adenoma sebaceum (reddish papules/fibromas around the nose)

Periungual fibroma (nodules arising from the nail bed)

Periungual fibroma (nodules arising from the nail bed)

Shagreen patches (firm, flesh-coloured plaques on the trunk)

Shagreen patches (firm, flesh-coloured plaques on the trunk)

Ash-leaf hypopigmentation (pale macules best seen with UV light)

Ash-leaf hypopigmentation (pale macules best seen with UV light)

Forehead plaque (indurated flesh-coloured patch)

Forehead plaque (indurated flesh-coloured patch)

Café-au-lait patches

Café-au-lait patches

Pitting of dental enamel.

Pitting of dental enamel.

Internal hamartomas can arise in the heart, lung, kidney, retina and CNS. Parents of a suspected case should be carefully examined (under UV light) as they may have a ‘forme fruste’ of the condition, which can manifest just as hypopigmented patches. This and gonadal mosaicism can have genetic implications for future offspring. A large contiguous gene defect may involve TSC2 and PKD1 genes causing tuberous sclerosis and polycystic kidney disease together in the same patient.

FURTHER READING

Curatolo P, Bombardieri R, Jozwiak S. Tuberous sclerosis. Lancet 2008; 372:657–668.

Diabetes mellitus

Diabetes mellitus (see also p. 1001) can have a number of cutaneous features. Complications of diabetes itself include:

Fungal infection (e.g. Candidiasis)

Fungal infection (e.g. Candidiasis)

Bacterial infections (e.g. recurrent boils)

Bacterial infections (e.g. recurrent boils)

Xanthomas

Xanthomas

Arterial disease (ulcers, gangrene)

Arterial disease (ulcers, gangrene)

Neuropathic ulcers.

Neuropathic ulcers.

Specific dermatoses of diabetes include:

Necrobiosis lipoidica (a patch of spreading erythema over the shin which becomes yellowish and atrophic in the centre and may ulcerate)

Necrobiosis lipoidica (a patch of spreading erythema over the shin which becomes yellowish and atrophic in the centre and may ulcerate)

Diffuse granuloma annulare (p. 1212)

Diffuse granuloma annulare (p. 1212)

Diabetic dermopathy (red-brown flat-topped papules)

Diabetic dermopathy (red-brown flat-topped papules)

Blisters (usually on the feet or hands)

Blisters (usually on the feet or hands)

Diabetic stiff skin (tight waxy skin over the fingers with limitation of joint movement owing to thickened collagen – also called cheiroarthropathy).

Diabetic stiff skin (tight waxy skin over the fingers with limitation of joint movement owing to thickened collagen – also called cheiroarthropathy).

Chronic liver disease

Chronic liver disease may present with jaundice, palmar erythema, spider naevi, white nails, hyperpigmentation and pruritus.

Porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT, p. 1045) is a rare genetic disorder associated with liver disease usually due to hepatic damage from excessive alcohol consumption or hepatitis C infection. Some 75% of cases are sporadic, 25% familial. Overall, 20% of cases have underlying hereditary haemochromatosis (p. 303). PCT presents clinically on exposed skin with sun-induced blisters, skin fragility, scarring, milia and hypertrichosis. Treatment of the cutaneous features is with repeated venesection and/or very low-dose chloroquine plus avoidance of alcohol. There is anecdotal evidence that specific treatment of hepatitis C will also help the skin, presumably by improving liver function. All people with PCT are at risk of hepatic carcinoma.

FURTHER READING

Elder GH. Alcohol and porphyria cutanea tarda. Clin Dermatol 1999; 17:431–436.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD)

Chronic kidney disease (see also p. 320) is commonly associated with intractable pruritus. Pallor, hyperpigmentation and ecchymoses are commonly seen. Rarely it is associated with non-inflammatory blisters, pseudo-porphyria cutanea tarda and cutaneous calcification. Longstanding renal transplant patients often suffer with recurrent viral warts and squamous cell carcinomas due to the immunosuppression.

‘Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy’ (also known as ‘nephrogenic systemic fibrosis’) is a newly described severe scleroderma-like skin disease in a subset of patients who have CKD (usually on dialysis). The disease is rapid in onset (days to weeks) with skin discoloration and thickening, joint contractures, muscle weakness and generalized pain. Widespread tissue fibrosis may ensue, causing severe morbidity. Patients may rapidly become wheelchair-bound. The condition is strongly associated with the contrast medium gadolinium used in MRI scans, and such contrast agents are best avoided in people with low GFRs. There is no accepted treatment but some advocate PUVA and extracorporeal photophoresis. No spontaneous remissions have been recorded. Rapid correction of renal function generally stops the condition progressing.

Calciphylaxis is discussed in Chapter 12.

Thyroid disease (see also p. 937)

Hypothyroidism may cause dry firm gelatinous (myxoedematous) skin with diffuse hair thinning and loss of the outer third of the eyebrows. Hyperthyroidism may be associated with warm sweaty skin and a diffuse alopecia. Graves’ disease is rarely associated with thyroid acropachy (‘clubbing’ with underlying bone changes) and pretibial myxoedema (a red-brown mucinous infiltration of the shins which can become lumpy and tender).

Cushing’s syndrome (see also p. 957)

This may cause hirsutism, a moon face, a buffalo hump, stretchmarks (striae) and a pustular folliculitis (often called steroid acne) of the skin.

Hyperlipidaemias

Hyperlipidaemias (see also p. 1034) can present with xanthomas, which are abnormal collections of lipid in the skin. All people with xanthomas should be investigated for hyperlipidaemia although the most common type, called xanthelasmas (yellow plaques around the eyes), are usually associated with normal lipids. There are a number of other clinical variants of xanthomas such as (1) tuberous xanthoma (firm orange-yellow nodules and plaques on extensor surfaces); (2) tendon xanthoma (firm subcutaneous swellings attached to tendons); (3) plane xanthoma (orange-yellow macules often affecting palmar creases); (4) eruptive xanthoma (numerous small yellowish papules commonly on the buttocks).

Amyloidosis

Macular amyloid is a common purely cutaneous variant seen in Asians. It is characterized by itchy brown rippled macules on the upper back.

Systemic amyloid may be associated with reddish brown papules, nodules or plaques especially around the eyes, the flexural areas and mucosal surfaces. Distinctive periorbital bruising and macroglossia may also be present.

Systemic malignant disease

Certain rashes may be a non-metastatic manifestation of an underlying malignancy: paraneoplastic dermatoses (Table 24.12). Rarely tumours can metastasize to the skin where they normally present as papules or nodules which may proceed to ulcerate.

Table 24.12 Non-metastatic cutaneous manifestations of underlying malignancy

| Dermatosis |

Tumour |

Dermatomyositis |

Lung, GI tract, GU tract |

Acanthosis nigricans |

GI tract, lung, liver |

Paget’s disease (localized patch of eczema around the nipple) |

Ductal breast carcinoma |

Erythroderma |

Lymphoma/leukaemia |

Tylosis (thickened palms/soles) |

Oesophageal carcinoma |

Tripe palms (velvet palms) |

Pulmonary, gastric |

Ichthyosis (dry flaking of skin) |

Lymphoma |

Erythema gyratum repens (concentric rings of erythema, which change rapidly) |

Lung, breast |

Necrolytic migratory erythema (burning, geographic and spreading annular areas of erythema) |

Glucagonoma |

FURTHER READING

Abreu Velez AM, Howard MS. Diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous paraneoplastic disorders. Dermatol Ther 2010; 23:662–675.

Stone JH, Zen Y, Deshpande V. IgG4-related disease. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:539–551.

Topham E. Cutaneous manifestations of cancer and chemotherapy. Clin Med 2009; 9:375–379.

Infantile acne. Facial acne is occasionally seen in infants and is sometimes cystic. It is thought to be due to the influence of maternal androgens and resolves spontaneously.

Infantile acne. Facial acne is occasionally seen in infants and is sometimes cystic. It is thought to be due to the influence of maternal androgens and resolves spontaneously. Steroid acne. Acne may occur secondary to corticosteroid therapy or Cushing’s syndrome. Clinically the rash often appears as a pustular folliculitis on the trunk without comedones.

Steroid acne. Acne may occur secondary to corticosteroid therapy or Cushing’s syndrome. Clinically the rash often appears as a pustular folliculitis on the trunk without comedones. Oil acne. This is an industrial disease seen in workers who have prolonged contact with oils or other hydrocarbons and is common on the legs and other exposed sites.

Oil acne. This is an industrial disease seen in workers who have prolonged contact with oils or other hydrocarbons and is common on the legs and other exposed sites. Acne fulminans. This is a rare variant seen most commonly in young male adolescents. Severe necrotic and crusted acne lesions appear associated with malaise, pyrexia, arthralgia and bone pain (due to sterile bone cysts). It requires urgent treatment with oral prednisolone (30–40 mg daily) and analgesics followed by a course of oral isotretinoin (see below).

Acne fulminans. This is a rare variant seen most commonly in young male adolescents. Severe necrotic and crusted acne lesions appear associated with malaise, pyrexia, arthralgia and bone pain (due to sterile bone cysts). It requires urgent treatment with oral prednisolone (30–40 mg daily) and analgesics followed by a course of oral isotretinoin (see below). ‘Acne conglobata’. Cystic acne with abscesses and interconnecting sinuses.

‘Acne conglobata’. Cystic acne with abscesses and interconnecting sinuses. ‘Acne excoriée’. Deeply excoriated and picked acne with associated scarring. It is much more common in females.

‘Acne excoriée’. Deeply excoriated and picked acne with associated scarring. It is much more common in females. ‘Follicular occlusion triad’. This is a rare disorder most commonly seen in black Africans. It is characterized by the presence of severe nodulocystic acne, dissecting cellulitis of the scalp (p. 1233) and hidradenitis suppurativa (p. 1198). This may be caused by a problem of follicular occlusion.

‘Follicular occlusion triad’. This is a rare disorder most commonly seen in black Africans. It is characterized by the presence of severe nodulocystic acne, dissecting cellulitis of the scalp (p. 1233) and hidradenitis suppurativa (p. 1198). This may be caused by a problem of follicular occlusion. Low-dose oral antibiotic therapy often helps but must be given for at least 3–4 months. Oxytetracycline 500 mg twice daily is often used first. Minocycline 100 mg daily, erythromycin 500 mg twice daily or trimethoprim 100 mg twice daily are also used.

Low-dose oral antibiotic therapy often helps but must be given for at least 3–4 months. Oxytetracycline 500 mg twice daily is often used first. Minocycline 100 mg daily, erythromycin 500 mg twice daily or trimethoprim 100 mg twice daily are also used. An extra treatment, cyproterone acetate 2 mg/ethinylestradiol 35 µg (co-cyprindol), is of value in females if there is no contraindication to oral contraception. This acts as a normal combined contraceptive but has antiandrogen activity. It may take 6–8 months to have its maximum effect. There is an increased incidence of DVT.

An extra treatment, cyproterone acetate 2 mg/ethinylestradiol 35 µg (co-cyprindol), is of value in females if there is no contraindication to oral contraception. This acts as a normal combined contraceptive but has antiandrogen activity. It may take 6–8 months to have its maximum effect. There is an increased incidence of DVT.