Spondyloarthritis

This is a group of conditions affecting the spine and peripheral joints which cluster in families and are linked to certain type 1 HLA antigens (Table 11.17).

The joint involvement is usually more limited than that seen in RA and its distribution is different. There are associated extra-articular and genetic features. These diseases occasionally present in childhood.

Histologically, the synovitis itself is similar to that of RA, but there is no production of rheumatoid factors – hence ‘seronegative’. ACPA is also usually negative. Inflammation of the enthesis (junction of ligament or tendon and bone) and joint ankylosis develop more commonly than in RA. All are associated with an increased frequency of sacroiliitis and an increased frequency of HLA-B27.

Aetiology

The common aetiological thread of these disorders is their striking association with HLA-B27, particularly ankylosing spondylitis (AS). HLA type B27 is present in >90% of Caucasians with AS but only 8% of controls. HLA-B27 exhibits a number of unusual characteristics including a high tendency to mis-fold but its aetiological relevance remains unclear. The role of class I HLA antigens in pathogenesis is supported by the fact that HLA-B27 transgenic mice spontaneously develop arthritis, skin, gut and genitourinary lesions.

There are clues that infections play a role, possibly by molecular mimicry, with parts of the organism which are structurally similar to the HLA molecule triggering cross-reactive antibody formation. This is unproven. AIDS is increasing the prevalence of reactive arthritis and spondylitis in sub-Saharan Africa even in the absence of HLA-B27. The explanation for this changing epidemiology is unclear.

The types of arthritis that follow a precipitating infection are called reactive arthritis (p. 529).

The specialized immune systems of the gut and genitourinary mucous membranes may also play a causal role, perhaps reacting to local infections or to antigens which cross the damaged mucosa.

Ankylosing spondylitis (as)

This is an inflammatory disorder of the spine affecting mainly young adults (late teens to early 30s). It occurs worldwide, with a male to female ratio of 5 : 1. Women present later and are underdiagnosed. The frequency of AS in different populations is roughly paralleled by the incidence of HLA-B27; Africans and Japanese have a low incidence of both HLA-B27 and ankylosing spondylitis, while the North American Haida Indians have a high incidence of both. There are at least 24 subtypes of HLA-B27 (B*2701-B*2724). Some appear to increase risk; others have a protective role. Twin studies indicate a much higher disease concordance in HLA-B27-positive monozygotic (up to 70%) twins than in dizygotic twins (about 20–25%). There are also other genes lying within the major histocompatibility complex (interleukin-1 gene cluster and the gene CYP2D6) which also influence susceptibility to AS but the disease is polygenic.

Epidemiology and pathogenesis

Environmental factors may also be involved but although Gram-negative organisms, e.g. Yersinia, Klebsiella, Salmonella, Shigella, can cause a reactive arthropathy, there is no conclusive evidence for their involvement in the pathogenesis of AS.

There is lymphocyte and plasma cell infiltration and local erosion of bone at the attachments of the intervertebral and other ligaments (enthesitis). This heals with new bone (syndesmophyte) formation.

Clinical features

Episodic inflammation of the sacroiliac joints in the late teenage years or early 20s is the first manifestation of AS. Pain in one or both buttocks and low back pain and stiffness are typically worse in the morning and relieved by exercise. Initially the diagnosis is often missed because the patient is asymptomatic between episodes and radiological abnormalities are absent. Retention of the lumbar lordosis during spinal flexion is an early sign. Later, paraspinal muscle wasting develops.

Criteria for classifying inflammatory back pain as ankylosing spondylitis are shown in Box 11.14.

![]() Box 11.14

Box 11.14

Back pain criteria for diagnosing ankylosing spondylitisa

The presence of four of the five criteria suggests AS with 80% sensitivity. aAll criteria have high sensitivity.

Spinal stiffness can be measured by Schober’s test: a tape measure is placed in the midline 10 cm above the dimples of Venus. Any movement of a marker at 15 cm during flexion is recorded. A reading of <5 cm implies spinal stiffness. Individuals may be able to touch the floor with a stiff back if they have good hip movements but serial measurement of the finger tip to floor distance highlights any change.

Non-spinal complications (uveitis or costochondritis) suggest the diagnosis of spondyloarthritis (Box 11.15). Costochondral junction inflammation causes anterior chest pain. Measurable reduction of chest expansion is due to costovertebral joint involvement.

Peripheral joint involvement is asymmetrical and affects a few, predominantly large joints. Hip involvement leads to fixed flexion deformities of the hips and further deterioration of the posture. Young teenage boys occasionally present with a lower-limb monoarthritis (see p. 546), which later develops into AS.

Acute anterior uveitis is strongly associated with HLA-B27 in AS and related diseases and is occasionally the presenting complaint. Severe eye pain, photophobia and blurred vision are an emergency (see p. 1062).

Overall clinical assessment is based on pain, tenderness, stiffness and fatigue using, e.g. the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index.

Investigations

Blood. The ESR and CRP are usually raised.

Blood. The ESR and CRP are usually raised.

HLA testing is rarely of value because of the high frequency of HLA-B27 in the population, but may give supporting evidence in a difficult case.

HLA testing is rarely of value because of the high frequency of HLA-B27 in the population, but may give supporting evidence in a difficult case.

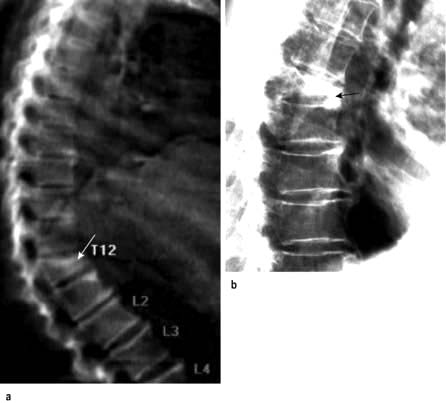

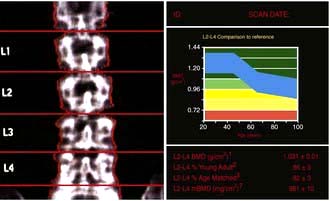

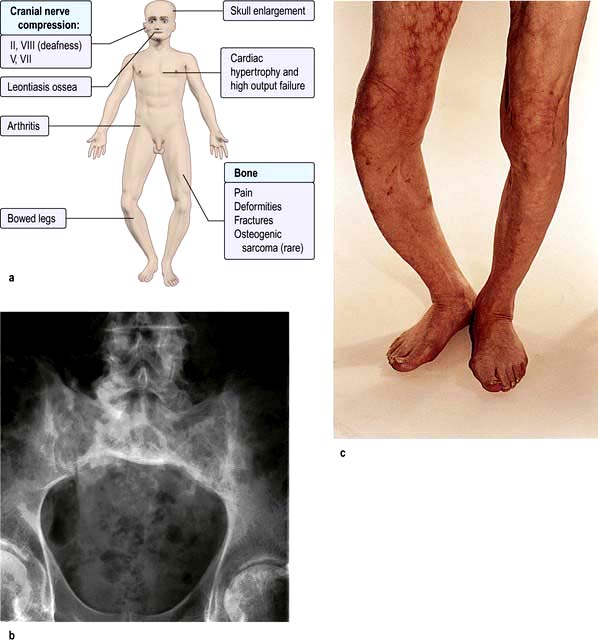

X-rays. The medial and lateral cortical margins of both sacroiliac joints lose definition owing to erosions and eventually become sclerotic (Fig. 11.20). The earliest radiological appearances in the spine are blurring of the upper or lower vertebral rims at the thoracolumbar junction (best seen on a lateral X-ray) caused by an enthesitis at the insertion of the intervertebral ligaments. These changes may eventually affect the whole spine. Persistent inflammatory enthesitis causes bony spurs (syndesmophytes). Syndesmophytes are more vertically oriented than the beak-like osteophytes of spondylosis and the disc is preserved, unlike in spondylosis (see p. 503). Syndesmophytes cause bony ankylosis and permanent stiffening. The sacroiliac joints eventually fuse, as may the costovertebral joints, reducing chest expansion. Calcification of the intervertebral ligaments and fusion of the spinal facet joints and syndesmophytes leads to what is often called a ‘bamboo’ spine (Fig. 11.21).

X-rays. The medial and lateral cortical margins of both sacroiliac joints lose definition owing to erosions and eventually become sclerotic (Fig. 11.20). The earliest radiological appearances in the spine are blurring of the upper or lower vertebral rims at the thoracolumbar junction (best seen on a lateral X-ray) caused by an enthesitis at the insertion of the intervertebral ligaments. These changes may eventually affect the whole spine. Persistent inflammatory enthesitis causes bony spurs (syndesmophytes). Syndesmophytes are more vertically oriented than the beak-like osteophytes of spondylosis and the disc is preserved, unlike in spondylosis (see p. 503). Syndesmophytes cause bony ankylosis and permanent stiffening. The sacroiliac joints eventually fuse, as may the costovertebral joints, reducing chest expansion. Calcification of the intervertebral ligaments and fusion of the spinal facet joints and syndesmophytes leads to what is often called a ‘bamboo’ spine (Fig. 11.21).

MRI with gadolinium demonstrates sacroiliitis before it is seen on X-rays, and persistent enthesitis.

MRI with gadolinium demonstrates sacroiliitis before it is seen on X-rays, and persistent enthesitis.

Figure 11.20 X-ray of ankylosing spondylitis. The sacroiliac joints are eroded and show marginal sclerosis (white arrows). There is bridging syndesmophyte formation at the thoracolumbar junction (black arrows).

Treatment

The key to effective management of AS is early diagnosis so that a regimen of preventative exercises is started before syndesmophytes have formed. Morning exercises aim to maintain spinal mobility, posture and chest expansion.

The key to effective management of AS is early diagnosis so that a regimen of preventative exercises is started before syndesmophytes have formed. Morning exercises aim to maintain spinal mobility, posture and chest expansion.

Failure to control pain and to encourage regular spinal and chest exercises leads to an irreversible dorsal kyphosis and wasted paraspinal muscles. This, along with stiffening of the cervical spine, makes forward vision difficult.

Failure to control pain and to encourage regular spinal and chest exercises leads to an irreversible dorsal kyphosis and wasted paraspinal muscles. This, along with stiffening of the cervical spine, makes forward vision difficult.

When the inflammation is active and the morning pain and stiffness are too severe to permit effective exercise, an evening dose of a long-acting or slow-release NSAID or an NSAID suppository improves sleep, pain control and exercise compliance. Peripheral arthritis and enthesitis are managed with NSAIDs or local steroid injections.

When the inflammation is active and the morning pain and stiffness are too severe to permit effective exercise, an evening dose of a long-acting or slow-release NSAID or an NSAID suppository improves sleep, pain control and exercise compliance. Peripheral arthritis and enthesitis are managed with NSAIDs or local steroid injections.

Methotrexate is effective for peripheral arthritis but not for spinal disease.

Methotrexate is effective for peripheral arthritis but not for spinal disease.

The TNF-α blocking drugs adalimumab and etanercept (Table 11.16) have revolutionized the lives of people with AS. They produce a rapid, dramatic and sustained reduction of symptoms and of spinal and peripheral joint inflammation. Around half the patients are able to stop NSAIDs. Relapse occurs on stopping therapy but may be delayed by several months making intermittent treatment feasible. Golimumab is also available for severe active disease unresponsive to conventional therapy. Rituximab does not help spondyloarthritis.

The TNF-α blocking drugs adalimumab and etanercept (Table 11.16) have revolutionized the lives of people with AS. They produce a rapid, dramatic and sustained reduction of symptoms and of spinal and peripheral joint inflammation. Around half the patients are able to stop NSAIDs. Relapse occurs on stopping therapy but may be delayed by several months making intermittent treatment feasible. Golimumab is also available for severe active disease unresponsive to conventional therapy. Rituximab does not help spondyloarthritis.

Prognosis

With exercise and pain relief, the prognosis is excellent and over 80% of patients are fully employed. Anti-TNF therapies are likely to reduce the morbidity of severe disease, reducing the risk of permanent spinal stiffness and progressive peripheral joint disease.

Patients should be made aware that they risk passing the HLA-B27 gene to 50% of their children. HLA-B27 positive offspring then have a 30% risk of developing AS.

Psoriatic arthritis

The prevalence of psoriasis is 2–3% worldwide, and in this population around 10% have arthritis (see p. 506). A family history of psoriasis may be a clue to the diagnosis. The aetiology and pathogenesis is described on page 509.

Clinical features

Patterns of psoriatic arthritis include:

Polyarthritis virtually indistinguishable from RA

Polyarthritis virtually indistinguishable from RA

Ankylosing spondylitis: uni- or bilateral sacroiliitis and early cervical spine involvement; only 50% are HLA-B27 positive

Ankylosing spondylitis: uni- or bilateral sacroiliitis and early cervical spine involvement; only 50% are HLA-B27 positive

Distal interphalangeal arthritis, which is the most typical pattern of joint involvement in psoriasis, often with adjacent nail dystrophy (see p. 1209) reflecting enthesitis extending into the nail root

Distal interphalangeal arthritis, which is the most typical pattern of joint involvement in psoriasis, often with adjacent nail dystrophy (see p. 1209) reflecting enthesitis extending into the nail root

Arthritis mutilans, which affects about 5% of patients who have psoriatic arthritis and causes marked periarticular osteolysis and bone shortening (’telescopic’ fingers) (Fig. 11.22).

Arthritis mutilans, which affects about 5% of patients who have psoriatic arthritis and causes marked periarticular osteolysis and bone shortening (’telescopic’ fingers) (Fig. 11.22).

Figure 11.22 Hand showing psoriatic arthritis mutilans. All the fingers are shortened and the joints unstable, owing to underlying osteolysis.

Radiologically, psoriatic arthritis is erosive but the erosions are central in the joint, not juxta-articular, and produce a ‘pencil in cup’ appearance (Fig. 11.23). The skin and nail disease can be mild and may develop after the arthritis.

Treatment and prognosis

NSAIDs and/or analgesics help the pain but they can occasionally worsen the skin lesions. Local synovitis responds to intra-articular corticosteroid injections.

In milder, polyarticular cases, sulfasalazine or methotrexate slows the development of joint damage.

When the disease is severe, methotrexate or ciclosporin is given because they control both the skin lesions and the arthritis. Anti-TNF-α agents, e.g. etanercept and golimumab (see p. 1210) and ustekinumab, are highly effective and safe for severe skin and joint disease. They should be given when methotrexate has failed. Corticosteroids orally may destabilize the skin disease and are best avoided but are valuable when injected into a single inflamed joint. Rituximab has no role in treating psoriatic arthritis.

The prognosis for the joint involvement is generally better than in RA.

Reactive arthritis

Reactive arthritis is a sterile synovitis, which occurs following an infection (see also post-streptococcal arthritis, p. 546).

Spondyloarthritis develops in 1–2% of patients after an acute attack of dysentery, or a sexually acquired infection – nonspecific urethritis (NSU) in the male, nonspecific cervicitis in the female. In male patients who are HLA-B27 positive, the relative risk is 30–50. Not all patients are HLA-B27 positive. Women are less commonly affected.

Aetiology

A variety of organisms can be the trigger, including some strains of Salmonella or Shigella spp. in bacillary dysentery. Yersinia enterocolitica causes diarrhoea and a reactive arthritis. In NSU, the organisms are Chlamydia trachomatis or Ureaplasma urealyticum.

People with reactive arthritis are not more susceptible to infection but appear to respond differently. Bacterial antigens or bacterial DNA have been found in the inflamed synovium of affected joints, suggesting that this persistent antigenic material is driving the inflammatory process. The methods by which HLA-B27 increases susceptibility to reactive arthritis may include:

T cell receptor repertoire selection

T cell receptor repertoire selection

Molecular mimicry causing autoimmunity against HLA-B27 and/or other self antigens

Molecular mimicry causing autoimmunity against HLA-B27 and/or other self antigens

Mode of presentation of bacteria-derived peptides to T lymphocytes.

Mode of presentation of bacteria-derived peptides to T lymphocytes.

These are not mutually exclusive.

There are other organisms that also trigger reactive arthritis but have a different genetic basis; see post-streptococcal arthritis (p. 533), gonococcal arthritis (p. 546) and brucellosis (p. 533). In these, the borderline between reactive arthritis and septic arthritis is more indistinct and they can cause both.

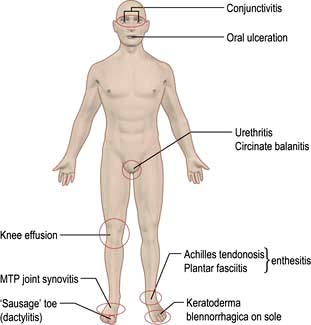

Clinical features (Fig. 11.24)

The arthritis is typically an acute, asymmetrical, lower-limb arthritis, occurring a few days to a couple of weeks after the infection. The arthritis may be the presenting complaint if the infection is mild or asymptomatic. Enthesitis is common, causing plantar fasciitis or Achilles tendon enthesitis (see p. 509). Seventy per cent recover fully within 6 months but many have a relapse.

In susceptible individuals with reactive arthritis, sacroiliitis and spondylitis may also develop. Sterile conjunctivitis occurs in 30%. Acute anterior uveitis complicates more severe or relapsing disease but is not synchronous with the arthritis.

The skin lesions resemble psoriasis:

Circinate balanitis in the uncircumcised male causes painless superficial ulceration of the glans penis. In the circumcised male the lesion is raised, red and scaly. Both heal without scarring.

Circinate balanitis in the uncircumcised male causes painless superficial ulceration of the glans penis. In the circumcised male the lesion is raised, red and scaly. Both heal without scarring.

Keratoderma blennorrhagica – the skin of the feet and hands develops painless, red and often confluent raised plaques and pustules histologically similar to pustular psoriasis.

Keratoderma blennorrhagica – the skin of the feet and hands develops painless, red and often confluent raised plaques and pustules histologically similar to pustular psoriasis.

Treatment

Treating persisting infection with antibiotics alters the course of the arthritis, once it has developed. Cultures should be taken and any infection treated. Sexual partners must be screened.

Pain responds well to NSAIDs and locally injected or oral corticosteroids. The majority of individuals with reactive arthritis have a single attack which settles, but a few develop a disabling relapsing and remitting arthritis. Relapsing cases are sometimes treated with sulfasalazine or methotrexate (Table 11.16). TNF-α blocking agents remain the drugs of next choice in severe and persistent disease but are rarely necessary.

Enteropathic arthritis associated with inflammatory bowel disease

Enteropathic synovitis occurs in up to 10–15% of patients who have ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease (see p. 275). The link between the bowel disease and the inflammatory arthritis is not clear. Selective mucosal leakiness may expose the individual to antigens that trigger synovitis.

The arthritis is asymmetrical and predominantly affects lower-limb joints. An HLA-B27-associated sacroiliitis or spondylitis also occurs. The joint symptoms may predate the development of bowel disease and lead to its diagnosis.

Remission of ulcerative colitis or total colectomy usually leads to remission of the joint disease, but arthritis can persist even in well-controlled Crohn’s disease.

Treatment

The inflammatory bowel disease should be treated (see p. 272). In all cases of enteropathic arthritis, the symptoms are helped by NSAIDs, although they may make diarrhoea worse. A monoarthritis is best treated by intra-articular corticosteroids. Sulfasalazine is more frequently prescribed than mesalazine as it may help both bowel and joint disease. The TNF-α blocking drug infliximab is used in inflammatory bowel disease (p. 272) and can help the arthritis.