Sexually transmitted infections

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are among the most common causes of illness in the world and remain epidemic in all societies. The public health, social and economic consequences are extensive, both for acute infections and for their longer-term sequelae.

Those most likely to acquire STIs are young people, homo- and bisexual men and black and ethnic minority populations. Changes in incidence reflect high-risk sexual behaviour and inconsistent use of condoms. Increased travel both within and between countries, recreational drug use, alcohol and more frequent partner change are also implicated. Multiple infections frequently co-exist, some of which may be asymptomatic and facilitate spread. Many people attend genito-urinary medicine (GUM) clinics to seek information, advice and checks of their sexual health, but have no active STI.

Approach to the patient

Patients presenting with possible STIs are frequently anxious, embarrassed and concerned about confidentiality. Staff must be alert to these issues and respond sensitively. The clinical setting must ensure privacy and reinforce confidentiality.

History

The history of the presenting complaint frequently focuses on genital symptoms, the three most common being vaginal discharge (Table 4.45), urethral discharge (Table 4.46) and genital ulceration (Table 4.47). Details should be obtained of any associated fever, pain, itch, malodour, genital swelling, skin rash, joint pains and eye symptoms. All patients should be asked about dysuria, haematuria and loin pain. A full general medical, family and drug history, particularly of any recent antibacterial or antiviral treatment, allergies and use of oral contraceptives, must be obtained. In women, menstrual, contraception and obstetric history should be obtained. Any past or current history of drug and/or alcohol misuse should be explored.

Table 4.45 Causes of vaginal discharge

| Infective | Non-infective |

|---|---|

Candida albicans |

Cervical polyps |

Trichomonas vaginalis |

Neoplasms |

Bacterial vaginosis |

Retained products (e.g. tampons) |

Neisseria gonorrhoeae |

Chemical irritation |

Chlamydia trachomatis |

|

Herpes simplex virus |

|

Table 4.46 Causes of urethral discharge

| Infective | Non-infective |

|---|---|

Neisseria gonorrhoeae |

Physical or chemical trauma |

Chlamydia trachomatis |

Urethral stricture |

Mycoplasma genitalium |

Nonspecific (aetiology unknown) |

Ureaplasma urealyticum |

|

Trichomonas vaginalis |

|

Herpes simplex virus |

|

Human papillomavirus (meatal warts) |

|

Urinary tract infection (rare) |

|

Treponema pallidum (meatal chancre) |

|

Table 4.47 Causes of genital ulceration

| Infective | Non-infective |

|---|---|

Syphilis: |

Behçet’s syndrome |

Primary chancre |

Toxic epidermal necrolysis |

Secondary mucous patches |

Stevens–Johnson syndrome |

Tertiary gumma |

Carcinoma |

Chancroid |

Trauma |

Lymphogranuloma venereum |

|

Donovanosis |

|

Herpes simplex: |

|

Primary |

|

Recurrent |

|

Herpes zoster |

|

A detailed sexual history should be taken and include the number and types of sexual contacts (genital/genital, oral/genital, anal/genital, oral/anal) with dates, partner’s sex, whether regular or casual partner, use of condoms and other forms of contraception, previous history of STIs including dates and treatment received, HIV testing and results and hepatitis B vaccination status.

Enquiries should be made concerning travel abroad to areas where antibiotic resistance is known or where particular pathogens are endemic.

Risk assessment of STI acquisition should be routinely undertaken. Those identified as being at high risk (e.g. frequent partner change, unprotected sex, use of drugs and/or alcohol to a level that reduces safer sex) should be offered risk reduction advice based on motivational interview techniques.

Examination

General examination must include the mouth, throat, skin and lymph nodes in all patients. Signs of HIV infection are covered on page 175. The inguinal, genital and perianal areas should be examined with a good light source. The groins should be palpated for lymphadenopathy and hernias. The pubic hair must be examined for nits and lice. The external genitalia must be examined for signs of erythema, fissures, ulcers, chancres, pigmented or hypopigmented areas and warts. Signs of trauma may be seen.

In men, the penile skin should be examined and the foreskin retracted to look for balanitis, ulceration, warts or tumours. The urethral meatus is located and the presence of discharge noted. Scrotal contents are palpated and the consistency of the testes and epididymis noted. A rectal examination/proctoscopy should be performed in patients with rectal symptoms, those who practise anoreceptive intercourse and patients with prostatic symptoms. A search for rectal warts is indicated in patients with perianal lesions.

In women, Bartholin’s glands must be identified and examined. The cervix should be inspected for ulceration, discharge, bleeding and ectopy and the walls of the vagina for warts. A bimanual pelvic examination is performed to elicit adnexal tenderness or masses, cervical tenderness and to assess the position, size and mobility of the uterus. Rectal examination and proctoscopy are performed if the patient has symptoms or practises anoreceptive intercourse.

Investigations

Although the history and examination will guide investigation, it must be remembered that multiple infections may co-exist, some being asymptomatic. Full screening is indicated in any patient who may have been in contact with an STI.

A guide for the investigation of asymptomatic patients is given in Table 4.48.

HIV antibody testing should be performed on an ‘opt out’ basis. If declined, the reasons why should be documented (see p. 178).

HIV antibody testing should be performed on an ‘opt out’ basis. If declined, the reasons why should be documented (see p. 178).

Asymptomatic screening for hepatitis viruses in patients in groups at increased risk and who, if susceptible, should be offered vaccination.

Asymptomatic screening for hepatitis viruses in patients in groups at increased risk and who, if susceptible, should be offered vaccination.

Table 4.48 Recommendations for screening and testing for sexually transmitted infections

GC, gonococcus; NAAT, nucleic acid amplification test; EIA, enzyme immunoassay; LGV lymphogranuloma venereum; TPHA, Treponema pallidum haemagglutination; TPPA, Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay.

Adapted from UK national guidance, BASHH 2006: http://www.bashh.org/documents/59/59.pdf

Screening tests for hepatitis B. Tests should include hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), which enables identification of currently infected individuals, and IgG anti-hepatitis B core, a marker of past infection and hence natural immunity. Screening is recommended for: men who have sex with men (MSM) and their sexual partners; sex workers; injecting drug users and their contacts; recipients of blood/blood products; needle-stick recipients; people who have been sexually assaulted; HIV-positive people; sexual partners of those who are HBsAg-positive and individuals from areas where hepatitis B is endemic.

Hepatitis A immunity screening and vaccination should be offered to MSM men in regions where an outbreak of hepatitis A has been reported, injecting drug users and patients with chronic hepatitis B or C, or other causes of chronic liver disease.

Hepatitis C. Hepatitis C screening is recommended in injecting drug users, recipients of blood/blood products, needle-stick recipients, patients with HIV and the sexual partners of HCV-positive people, as treatment is frequently required.

Investigations for symptomatic patients

The investigations will depend on the clinical presentation. Common presentations include urethral discharge in men, vaginal discharge in women and genital ulceration. Recommended investigations are shown in Table 4.48.

Treatment, prevention and control

The treatment of specific conditions is considered in the appropriate section. Many GUM clinics keep basic stocks of medication and dispense directly to the patient. Treatment, particularly for those conditions that may be asymptomatic, is a major way to prevent onward transmission.

Tracing the sexual partners of patients is crucial in controlling the spread of STIs. The aims are to prevent the spread of infection within the community and to ensure that people with asymptomatic infection are properly treated. Appropriate antibiotic therapy may be offered to those who have had recent intercourse with someone known to have an active infection (epidemiological treatment). Interviewing people about their sexual partners requires considerable tact and sensitivity and specialist health advisers are available in GUM clinics.

Over half of all STI diagnoses in the UK are in young adults (16–24 years). Prevention starts with education and information. People begin sexual activity at ever-younger ages and education programmes need to include school pupils as well as young adults. Education of health professionals is also crucial. Public health campaigns aimed at informing groups at particular risk are being implemented at a national level. The National Chlamydia Screening Programme in England (NCSP) aims to provide earlier detection and treatment for Chlamydia by providing easy access for under 25s to Chlamydia testing in community settings.

Avoiding multiple partners, correct and consistent use of condoms and avoiding sex with people who have symptoms of infection may reduce the risks of acquiring an STI. For those who change their sexual partners frequently, regular check-ups (approximately 3-monthly) are advisable. Once people develop symptoms they should be encouraged to seek medical advice as soon as possible to reduce complications and spread to others.

Sexual assault

The medical and psychological management of people who have been sexually assaulted requires particular sensitivity and should be undertaken by an experienced clinician in ways that reduce the risks of further trauma. Specialist sexual assault centres exist, providing multidisciplinary medical, forensic and psychological care in secure and sensitive settings. Post-traumatic stress disorder is common. Although most frequently reported by women, both women and men may suffer sexual assault. Investigations for and treatment of sexually transmitted infections in people who have been raped can be carried out in GUM departments. Collection of material for use as evidence, however, should be carried out within 7 days of the assault by a physician trained in forensic medicine and must take place before any other medical examinations are performed.

History

In addition to the general medical, gynaecological and contraceptive history, full details of the assault, including the exact sites of penetration, ejaculation by the assailant and condom use should be obtained, together with details of the sexual history both before and after the event.

Examination

Any injuries requiring immediate attention must be dealt with prior to any other examination or investigations. Accurate documentation of any trauma is necessary. Forced oral penetration may result in small palatal haemorrhages. In cases of forced anal penetration, anal examination including proctoscopy should be carried out, noting any trauma.

Investigations

The risk of STI acquisition from rape is variable and depends on the incidence of STI in the population. Ideally, a full STI screen at presentation, with appropriate specimens collected from all sites of actual or attempted penetration and a second examination 2 weeks later, is recommended. Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) for Neisseria gonorrhoeae and for Chlamydia trachomatis can be carried out on urine specimens, avoiding the need for invasive examinations. A positive test should be confirmed by another method for medicolegal purposes. Gram-stained slides of urethral, cervical and rectal specimens for microscopy for gonococci should be performed. Bacterial vaginosis, yeasts and Trichomonas vaginalis (TV) tests should be carried out on vaginal material. Syphilis serology should be requested and a serum saved. Hepatitis B, HIV and hepatitis C testing should be offered. Specimens should be identified as having potential medicolegal implications.

Management

Preventative therapy for gonorrhoea and Chlamydia is advised using a single dose combination of ciprofloxacin 500 mg and azithromycin 1 g. An accelerated course of Hep B vaccine should be offered and may be of value up to 3 weeks after the event. HIV prophylaxis may be offered within 72 h of the assault, based upon risk assessment. Post-coital oral contraception may be given within 72 h of assault. Psychological care provision and appropriate referral to support agencies should be arranged. Sexual partners should be screened and treated if necessary. Follow-up at 2 weeks should be arranged to review the patient’s needs and the prophylaxis regimens that are in place, with further follow-up as needed (e.g. to confirm or exclude acquisition of HBV, HIV or HCV infection). Following sexual assault, most people have a range of emotional and psychological reactions and will require varying levels of psychological support. Referral to a specialist centre is recommended.

CLINICAL SYNDROMES

Gonorrhoea (GC)

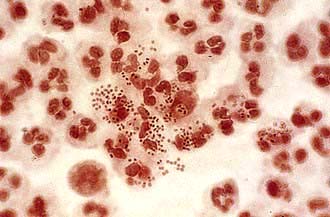

Neisseria gonorrhoeae (Gonococci, GC) is a Gram-negative intracellular diplococcus (Fig. 4.37), which infects epithelium particularly of the urogenital tract, rectum, pharynx and conjunctivae. Humans are the only host and the organism is spread by intimate physical contact. It is very intolerant to drying and although occasional reports of spread by fomites exist, this route of infection is extremely rare.

Clinical syndromes

Clinical features

Up to 50% of women and 10% of men are asymptomatic. The incubation period is 2–14 days with most symptoms occurring between days 2 and 5.

In men, the most common syndrome is one of anterior urethritis causing dysuria and/or urethral discharge (Fig. 4.38). Complications include ascending infection involving the epididymis or prostate leading to acute or chronic infection. In MSM rectal infection may produce proctitis with pain, discharge and itch.

In men, the most common syndrome is one of anterior urethritis causing dysuria and/or urethral discharge (Fig. 4.38). Complications include ascending infection involving the epididymis or prostate leading to acute or chronic infection. In MSM rectal infection may produce proctitis with pain, discharge and itch.

In women, the primary site of infection is usually the endocervical canal. Symptoms include an increased or altered vaginal discharge, pelvic pain due to ascending infection, dysuria and intermenstrual bleeding. Complications include Bartholin’s abscesses and in rare cases a perihepatitis (Fitzhugh–Curtis syndrome) can develop. On a global basis GC is one of the most common causes of female infertility. Rectal infection, due to local spread, occurs in women and is usually asymptomatic, as is pharyngeal infection. Conjunctival infection is seen in neonates born to infected mothers and is one cause of ophthalmia neonatorum.

In women, the primary site of infection is usually the endocervical canal. Symptoms include an increased or altered vaginal discharge, pelvic pain due to ascending infection, dysuria and intermenstrual bleeding. Complications include Bartholin’s abscesses and in rare cases a perihepatitis (Fitzhugh–Curtis syndrome) can develop. On a global basis GC is one of the most common causes of female infertility. Rectal infection, due to local spread, occurs in women and is usually asymptomatic, as is pharyngeal infection. Conjunctival infection is seen in neonates born to infected mothers and is one cause of ophthalmia neonatorum.

Disseminated GC leads to arthritis (usually monoarticular or pauciarticular) (see p. 533) and characteristic papular or pustular rash with an erythematous base in association with fever and malaise. It is more common in women.

Diagnosis

N. gonorrhoeae can be identified from infected areas by culture on selective media with a sensitivity of at least 95%. Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) using urine specimens are non-invasive and highly sensitive, although they may give false-positive results. Microscopy of Gram-stained secretions may demonstrate intracellular, Gram-negative diplococci, allowing rapid diagnosis. The sensitivity ranges from 90% in urethral specimens from symptomatic men to 50% in endocervical specimens. Microscopy should not be used for pharyngeal specimens. Blood culture and synovial fluid investigations should be performed in cases of disseminated GC. Co-existing pathogens such as Chlamydia, Trichomonas and syphilis must be sought.

Treatment is indicated in those patients who have a positive culture for GC, positive microscopy or a positive NAAT (this should be repeated because of false positives and all positives should be confirmed by cultures). Treatment is given to patients who have had recent sexual intercourse with someone with confirmed GC infection. Although N. gonorrhoeae is sensitive to a wide range of antimicrobial agents, antibiotic-resistant strains have shown a recent significant increase. Immediate therapy based on Gram-stained slides is usually initiated in the clinic, prior to culture and sensitivity results. Antibiotic choice is influenced by travel history or details known from contacts.

Single-dose ceftriaxone i.m. (500 mg) is recommended in the UK. Single-dose oral amoxicillin 3 g with probenecid 1 g, ciprofloxacin (500 mg) or ofloxacin (400 mg) may be used in areas with low prevalence of antibiotic resistance. (The CDC has reported high resistance, however, and recommends the addition of azithromycin 1 g orally.) Resistance to all antibiotics has recently been reported.

Longer courses of antibiotics are required for complicated infections. There should be at least one follow-up assessment and culture tests should be repeated at least 72 h after treatment is complete. All sexual contacts should be notified and then examined and treated as necessary.

Chlamydia trachomatis (CT)

This organism has a worldwide distribution. Genital infection with CT is common, with up to 14% of sexually active people below the age of 25 years in the UK infected. It is regularly found in association with other pathogens: 20% of men and 40% of women with gonorrhoea have been found to have co-existing Chlamydia infections. In men 40% of non-gonococcal and post-gonococcal urethritis is due to Chlamydia. As CT is often asymptomatic much infection goes unrecognized and untreated, which sustains the infectious pool in the population. The long-term complications associated with Chlamydia infection, especially infertility, impose significant morbidity in the UK. The UK government has introduced a national Chlamydia screening programme in an attempt to decrease the rates of asymptomatic infection.

Clinical features

In men, CT gives rise to an anterior urethritis with dysuria and discharge; infection is asymptomatic in up to 50% and detected by contact tracing. Ascending infection leads to epididymitis. Rectal infection leading to proctitis occurs in men practising anoreceptive intercourse. In women, the most common site of infection is the endocervix, where it may go unnoticed; up to 80% of infection in women is asymptomatic. Symptoms include vaginal discharge, post-coital or intermenstrual bleeding and lower abdominal pain. Ascending infection causes acute salpingitis. Reactive arthritis (see p. 529) has been related to infection with C. trachomatis. Neonatal infection, acquired from the birth canal, can result in mucopurulent conjunctivitis and pneumonia.

Diagnosis

CT is an obligate intracellular bacterium, which complicates diagnosis. The nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) is the diagnostic test of choice and is used as the ‘standard of care’ with a 90–95% sensitivity. Cell culture techniques provide the ‘gold standard’ and are 100% specific, but are expensive and require considerable expertise. Indirect diagnostic tests include direct fluorescent antibody (DIF) tests and enzyme immunoassays (EIA), but they are less reliable and none is diagnostic.

In men, first-voided urine samples are tested, or urethral swabs obtained. In women endocervical swabs are the best specimens and up to 20% additional positives will be detected if urethral swabs are also taken. Urine specimens are less reliable than endocervical swabs in women but are useful if a speculum examination is not possible.

Ligase chain reaction (LCR) can be used as an alternative to PCR.

Treatment

Tetracyclines or macrolide antibiotics are most commonly used to treat Chlamydia. Azithromycin 1 g as a single dose or doxycycline 100 mg 12-hourly for 7 days or are both effective for uncomplicated infection. Tetracyclines are contraindicated in pregnancy. Other effective regimens include erythromycin 500 mg four times daily. Routine test of cure is not necessary after treatment with doxycycline or azithromycin, although if symptoms persist or reinfection is suspected then further tests should be taken. NAATs may remain positive for up to 5 weeks after treatment as they pick up material from non-viable organisms. Sexual contacts must be traced, notified and treated, particularly as so many infections are clinically silent.

Urethritis

Urethritis is usually characterized in men by a discharge from the urethra, dysuria and varying degrees of discomfort within the penis. In 10–15% of cases there are no symptoms. A wide array of aetiologies can give rise to the clinical picture and are divided into two broad bands: gonococcal or non-gonococcal urethritis (NGU). NGU occurring shortly after infection with gonorrhoea is known as postgonococcal urethritis (PGU). Gonococcal urethritis and Chlamydia urethritis (a major cause of NGU) are discussed above.

Trichomonas vaginalis, Mycoplasma genitalium, Ureaplasma urealyticum and Bacteroides spp. are responsible for a proportion of cases. HSV can cause urethritis in about 30% of cases of primary infection, considerably fewer in recurrent episodes. Other causes include syphilitic chancres and warts within the urethra. Non-sexually transmitted NGU may be due to urinary tract infections, prostatic infection, foreign bodies and strictures.

Clinical features

The urethral discharge is often mucoid and worse in the mornings. Crusting at the meatus or stains on underwear occur. Dysuria is common but not universal. Discomfort or itch within the penis may be present. The incubation period is 1–5 weeks with a mean of 2–3 weeks. Asymptomatic urethritis is a major reservoir of infection. Reactive arthritis (see p. 529) causing conjunctivitis with arthritis occurs, particularly in HLA B27-positive individuals.

Diagnosis

NAATs for gonorrhoea and Chlamydia should be performed in all men with symptoms of urethritis. In those who are negative, smears should be taken from the urethra when the patient has not voided urine for at least 4 h and should be Gram-stained and examined under a high-power (×1000) oil-immersion lens. The presence of five or more polymorphonuclear leucocytes per high-power field or a Gram-stained preparation from a centrifuged sample of a first passed urine specimen, containing >10 PMNL per high-power is diagnostic. Men who are symptomatic but have no objective evidence of urethritis should be re-examined and tested after holding urine overnight. Cultures for gonorrhoea must be taken together with specimens for Chlamydia testing.

Treatment

Therapy for NGU is with either azithromycin 1 g orally as a single dose or doxycycline 100 mg 12-hourly for 7 days. Sexual intercourse should be avoided. The vast majority of patients will show partial or total response. Sexual partners must be traced and treated; C. trachomatis can be isolated from the cervix in 50–60% of the female partners of men with PGU or NGU, many of whom are asymptomatic. This causes long-term morbidity in such women, acts as a reservoir of infection for the community and may lead to reinfection in the index case if not treated.

Recurrent/persistent NGU

This is a common and difficult clinical problem which is empirically defined as persistent or recurrent symptomatic urethritis occurring 30–90 days following treatment of acute NGU. It can occur in 20–60% of men treated for acute NGU. The usual time for patients to re-present is 2–3 weeks following treatment. Tests for organisms, e.g. Mycoplasma, Chlamydia and Ureaplasma, are usually negative. It is necessary to document objective evidence of urethritis, check adherence to treatment and establish any possible contact with untreated sexual partners. A further 1 week’s treatment with erythromycin 500 mg four times a day for 2 weeks plus metronidazole 400 mg twice daily for 5 days may be given and any specific additional infection treated appropriately. If symptoms are mild and all partners have been treated, patients should be reassured and further antibiotic therapy avoided. In cases of frequent recurrence and/or florid unresponsive urethritis, the prostate should be investigated and urethroscopy or cystoscopy performed to investigate possible strictures, periurethral fistulae or foreign bodies.

Lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV)

Chlamydia trachomatis types LGV 1, 2 and 3 (different biovars or variant prokaryotic strain) are responsible for this sexually transmitted infection. It is endemic in the tropics, with the highest incidences in Africa, India and South-east Asia. There has been a recent upsurge in UK-acquired LGV, particularly among HIV-infected men who have sex with men (MSM), presenting with rectal symptoms and associated genital ulceration. Many have also been hepatitis C co-infected. The L2 serovar (different antigenic properties) has been the predominant strain. The Health Protection Agency has enhanced LGV surveillance to track the current UK outbreak.

Clinical features

There are three characteristic stages. The primary lesion is a painless ulcerating papule on the genitalia occurring 7–21 days following exposure. It is frequently unnoticed. A few days to weeks after this heals, regional lymphadenopathy develops. The lymph nodes are painful and fixed and the overlying skin develops a dusky erythematous appearance. Finally, nodes may become fluctuant (buboes) and can rupture. Acute LGV also presents as proctitis with perirectal abscesses, the appearances sometimes resembling anorectal Crohn’s disease. The destruction of local lymph nodes can lead to lymphoedema of the genitalia.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is often made on the basis of the characteristic clinical picture after other causes of genital ulceration or inguinal lymphadenopathy have been excluded. Syphilis and genital herpes must be excluded. The laboratory investigations have become more sensitive and specific:

Detection of nucleic acid (DNA). Nucleic acid amplification tests for LGV serovar are now available. Positive samples should be confirmed by real-time PCR for LGV-specific DNA.

Detection of nucleic acid (DNA). Nucleic acid amplification tests for LGV serovar are now available. Positive samples should be confirmed by real-time PCR for LGV-specific DNA.

Isolation of C. trachomatis from clinical lesions in tissue culture remains the most specific test; however, sensitivity is only 75–85%.

Isolation of C. trachomatis from clinical lesions in tissue culture remains the most specific test; however, sensitivity is only 75–85%.

Chlamydia trachomatis serology. Complement fixation (CF) tests, single L-type immunofluorescence test and micro-immunofluorescence test (micro-IF) (the latter being the most accurate). A four-fold rise in antibody titre in the course of the illness or a single point titre of >1/64 is considered to be diagnostic.

Chlamydia trachomatis serology. Complement fixation (CF) tests, single L-type immunofluorescence test and micro-immunofluorescence test (micro-IF) (the latter being the most accurate). A four-fold rise in antibody titre in the course of the illness or a single point titre of >1/64 is considered to be diagnostic.

Treatment

Early treatment is critical to prevent the chronic phase. Doxycycline (100 mg twice daily for 21 days) or erythromycin (500 mg four times daily for 21 days) is efficacious. Follow-up should continue until signs and symptoms have resolved, usually 3–6 weeks. Chronic infection may result in extensive scarring and abscess and sinus formation. Surgical drainage or reconstructive surgery is sometimes required. HIV and hepatitis C screening should be recommended. Sexual partners in the 30 days prior to onset should be notified, examined and treated if necessary.

Syphilis

Syphilis is a chronic systemic disease, which is acquired or congenital. In its early stages diagnosis and treatment are straightforward but untreated it can cause complex sequelae in many organs and eventually lead to death. There has been a marked increase in the incidence of syphilis over the past decade. A majority of these infections occur in MSM, many of whom are co-infected with HIV.

The causative organism, Treponema pallidum (TP), is a motile spirochaete that is acquired either by close sexual contact or can be transmitted transplacentally. The organism enters the new host through breaches in squamous or columnar epithelium. Primary infection of non-genital sites may occasionally occur but is rare.

Both acquired and congenital syphilis have early and late stages, each of which has classic clinical features (Table 4.49).

Primary. Between 10 and 90 days (mean 21 days) after exposure to the pathogen a papule develops at the site of inoculation. This ulcerates to become a painless, firm chancre. There is usually painless regional lymphadenopathy in association. The primary lesion may go unnoticed, especially if it is on the cervix or within the rectum. Healing occurs spontaneously within 2–3 weeks.

Primary. Between 10 and 90 days (mean 21 days) after exposure to the pathogen a papule develops at the site of inoculation. This ulcerates to become a painless, firm chancre. There is usually painless regional lymphadenopathy in association. The primary lesion may go unnoticed, especially if it is on the cervix or within the rectum. Healing occurs spontaneously within 2–3 weeks.

Secondary. Between 4 and 10 weeks after the appearance of the primary lesion constitutional symptoms with fever, sore throat, malaise and arthralgia appear. Any organ may be affected – leading, for example, to hepatitis, nephritis, arthritis and meningitis. In a minority of cases the primary chancre may still be present and should be sought.

Secondary. Between 4 and 10 weeks after the appearance of the primary lesion constitutional symptoms with fever, sore throat, malaise and arthralgia appear. Any organ may be affected – leading, for example, to hepatitis, nephritis, arthritis and meningitis. In a minority of cases the primary chancre may still be present and should be sought.

Table 4.49 Classification and clinical features of syphilis

| Clinical features | |

|---|---|

Acquired |

|

Early stages |

|

Primary |

Hard chancre |

Painless, regional lymphadenopathy |

|

Secondary |

General: Fever, malaise, arthralgia, sore throat and generalized lymphadenopathy |

Skin: Red/brown maculopapular non-itchy, sometimes scaly rash; condylomata lata |

|

Mucous membranes: Mucous patches, ‘snail-track’ ulcers in oropharynx and on genitalia |

|

Late stages |

|

Tertiary |

Late benign: Gummas (bone and viscera) |

Cardiovascular: Aortitis and aortic regurgitation |

|

Neurosyphilis: Meningovascular involvement, general paralysis of the insane (GPI) and tabes dorsalis |

|

Congenital |

Stillbirth or failure to thrive |

Early stages |

‘Snuffles’ (nasal infection with discharge) |

Skin and mucous membrane lesions as in secondary syphilis |

|

Late stages |

‘Stigmata’: Hutchinson’s teeth, ‘sabre’ tibia and abnormalities of long bones, keratitis, uveitis, facial gummas and CNS disease |

Generalized lymphadenopathy (50%)

Generalized lymphadenopathy (50%)

Generalized skin rashes involving the whole body including the palms and soles but excluding the face (75%) – the rash, which rarely itches, may take many different forms, ranging from pink macules, through coppery papules, to frank pustules (Fig. 4.39)

Generalized skin rashes involving the whole body including the palms and soles but excluding the face (75%) – the rash, which rarely itches, may take many different forms, ranging from pink macules, through coppery papules, to frank pustules (Fig. 4.39)

Condylomata lata: warty, plaque-like lesions found in the perianal area and other moist body sites

Condylomata lata: warty, plaque-like lesions found in the perianal area and other moist body sites

Superficial confluent ulceration of mucosal surfaces – found in the mouth and on the genitalia, described as ‘snail track ulcers’

Superficial confluent ulceration of mucosal surfaces – found in the mouth and on the genitalia, described as ‘snail track ulcers’

Acute neurological signs in less than 10% of cases (e.g. aseptic meningitis).

Acute neurological signs in less than 10% of cases (e.g. aseptic meningitis).

Untreated early syphilis in pregnant women leads to fetal infection in at least 70% of cases and may result in stillbirth in up to 30%.

Latent. Without treatment, symptoms and signs abate over 3–12 weeks, but in up to 20% of individuals, may recur during a period known as early latency, a 2-year period in the UK (1 year in USA). Late latency is based on reactive syphilis serology with no clinical manifestations for at least 2 years. This can continue for many years before the late stages of syphilis become apparent.

Latent. Without treatment, symptoms and signs abate over 3–12 weeks, but in up to 20% of individuals, may recur during a period known as early latency, a 2-year period in the UK (1 year in USA). Late latency is based on reactive syphilis serology with no clinical manifestations for at least 2 years. This can continue for many years before the late stages of syphilis become apparent.

Tertiary. Late benign syphilis, so called because of its response to therapy rather than its clinical manifestations, generally involves the skin and the bones. The characteristic lesion, the gumma (granulomatous, sometimes ulcerating, lesions), can occur anywhere in the skin, frequently at sites of trauma. Gummas are commonly found in the skull, tibia, fibula and clavicle, although any bone may be involved. Visceral gummas occur mainly in the liver (hepar lobatum) and the testes.

Tertiary. Late benign syphilis, so called because of its response to therapy rather than its clinical manifestations, generally involves the skin and the bones. The characteristic lesion, the gumma (granulomatous, sometimes ulcerating, lesions), can occur anywhere in the skin, frequently at sites of trauma. Gummas are commonly found in the skull, tibia, fibula and clavicle, although any bone may be involved. Visceral gummas occur mainly in the liver (hepar lobatum) and the testes.

Cardiovascular and neurosyphilis are discussed on pages 669, 1129.

Congenital syphilis

Congenital syphilis usually becomes apparent between the 2nd and 6th week after birth, early signs being nasal discharge, skin and mucous membrane lesions and failure to thrive. Signs of late syphilis generally do not appear until after 2 years of age and take the form of ‘stigmata’ relating to early damage to developing structures, particularly teeth and long bones. Other late manifestations parallel those of adult tertiary syphilis.

Investigations for diagnosis

Treponema pallidum is not amenable to in vitro culture – the most sensitive and specific method is identification by dark-ground microscopy. Organisms may be found in variable numbers, from primary chancres and the mucous patches of secondary lesions. Individuals with either primary or secondary disease are highly infectious.

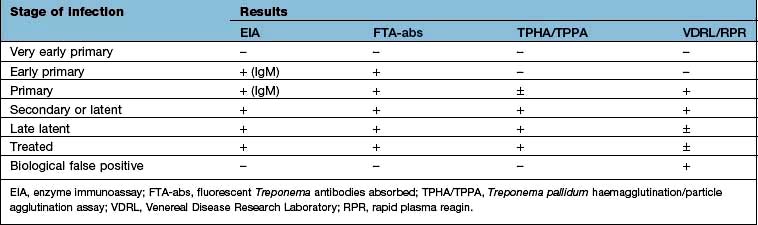

Serological tests used in diagnosis are either treponemal-specific or nonspecific (cardiolipin test) (Table 4.50):

Treponemal specific. The T. pallidum enzyme immunoassay (EIA). T. pallidum haemagglutination or particle agglutination assay (TPHA/TPPA) and fluorescent treponemal antibodies absorbed (FTA-abs) test are both highly specific for treponemal disease but will not differentiate between syphilis and other treponemal infection such as yaws. These tests usually remain positive for life, even after treatment.

Treponemal specific. The T. pallidum enzyme immunoassay (EIA). T. pallidum haemagglutination or particle agglutination assay (TPHA/TPPA) and fluorescent treponemal antibodies absorbed (FTA-abs) test are both highly specific for treponemal disease but will not differentiate between syphilis and other treponemal infection such as yaws. These tests usually remain positive for life, even after treatment.

Treponemal nonspecific. The Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) and rapid plasma reagin (RPR) tests are nonspecific, becoming positive within 3–4 weeks of the primary infection. They are quantifiable tests which can be used to monitor treatment efficacy and are helpful in assessing disease activity. They generally become negative by 6 months after treatment in early syphilis. The VDRL may also become negative in untreated patients (50% of patients with late-stage syphilis) or remain positive after treatment in late stage. False-positive results may occur in other conditions – particularly infectious mononucleosis, hepatitis, Mycoplasma infections, some protozoal infections, cirrhosis, malignancy, autoimmune disease and chronic infections.

Treponemal nonspecific. The Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) and rapid plasma reagin (RPR) tests are nonspecific, becoming positive within 3–4 weeks of the primary infection. They are quantifiable tests which can be used to monitor treatment efficacy and are helpful in assessing disease activity. They generally become negative by 6 months after treatment in early syphilis. The VDRL may also become negative in untreated patients (50% of patients with late-stage syphilis) or remain positive after treatment in late stage. False-positive results may occur in other conditions – particularly infectious mononucleosis, hepatitis, Mycoplasma infections, some protozoal infections, cirrhosis, malignancy, autoimmune disease and chronic infections.

The EIA is the screening test of choice and can detect both IgM and IgG antibodies. A positive test is then confirmed with the TPHA/TPPA and VDRL/RPR tests. All serological investigations may be negative in early primary syphilis; the EIA IgM and the FTA-abs being the earliest tests to be positive. The diagnosis will then hinge on positive dark-ground microscopy. Treatment should not be delayed if serological tests are negative in such situations.

Examination of the CSF for evidence of neurosyphilis is indicated in those patients with syphilis who demonstrate neurological signs and symptoms, have a high titre of non-treponemal tests (usually taken to be >1:32), those who have any evidence of treatment failure and HIV co-infected patients with late latent syphilis or syphilis of unknown duration. A chest X-ray should also be performed.

Treatment

Treponemocidal levels of antibiotic must be maintained in serum for at least 7 days in early syphilis to cover the slow division time of the organism (30 h). In late syphilis treponemes may divide even more slowly requiring longer therapy.

Early syphilis (primary or secondary) should be treated with long-acting penicillin such as procaine benzylpenicillin (procaine penicillin) (e.g. Jenacillin A, which also contains benzylpenicillin) 600 mg intramuscularly daily for 10 days.

Early syphilis (primary or secondary) should be treated with long-acting penicillin such as procaine benzylpenicillin (procaine penicillin) (e.g. Jenacillin A, which also contains benzylpenicillin) 600 mg intramuscularly daily for 10 days.

For late-stage syphilis, particularly when there is cardiovascular or neurological involvement, the treatment course should be extended for a further week.

For late-stage syphilis, particularly when there is cardiovascular or neurological involvement, the treatment course should be extended for a further week.

For patients sensitive to penicillin, either doxycycline 200 mg daily or erythromycin 500 mg four times daily is given orally for 2–4 weeks depending on the stage of the infection. Non-compliant patients can be treated with a single dose of benzathine penicillin G 2.4 g intramuscularly. Azithromycin is not recommended following evidence of resistance. The diagnosis and management of syphilis in HIV co-infected patients remains unaltered; however, if untreated it may advance more rapidly than in HIV-negative patients and have a higher incidence of neurosyphilis. The Jarisch–Herxheimer reaction, which is due to release of TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-8, is seen in 50% of patients with primary syphilis and up to 90% of patients with secondary syphilis. It occurs about 8 h after the first injection and usually consists of mild fever, malaise and headache lasting several hours. In cardiovascular or neurosyphilis the reaction, although rare, may be severe and exacerbate the clinical manifestations. Prednisolone given for 24 h prior to therapy may ameliorate the reaction but there is little evidence to support its use. Penicillin should not be withheld because of the Jarisch–Herxheimer reaction; since it is not a dose-related phenomenon, there is no value in giving a smaller dose.

The prognosis depends on the stage at which the infection is treated. Early and early latent syphilis have an excellent outlook but once extensive tissue damage has occurred in the later stages the damage will not be reversed although the process may be halted. Symptoms in cardiovascular disease and neurosyphilis may therefore persist.

All patients treated for early syphilis must be followed up at regular intervals for the first year following treatment. Serological markers with a fall in titre of the VDRL/RPR of at least four-fold is consistent with adequate treatment for early syphilis. The sexual partners of all patients with syphilis and the parents and siblings of patients with congenital syphilis must be contacted and screened. Babies born to mothers who have been treated for syphilis in pregnancy are retreated at birth.

Chancroid

Chancroid or soft chancre is an acute STI caused by Haemophilus ducreyi. Although a less common cause of genital ulceration than HSV-2, it is prevalent in parts of Africa and Asia. It is rare in the UK with cases usually associated with travel to or partners from endemic areas. Epidemiological studies in Africa have shown an association between genital ulcer disease, frequently chancroid and the acquisition of HIV infection. A new urgency to control chancroid has resulted from these observations.

Clinical features

The incubation period is 3–10 days. At the site of inoculation an erythematous papular lesion forms which then breaks down into an ulcer. The ulcer frequently has a necrotic base, a ragged edge, bleeds easily and is painful. Several ulcers may merge to form giant serpiginous lesions. Ulcers appear most commonly on the prepuce and frenulum in men and can erode through tissues. In women the most commonly affected site is the vaginal entrance and the perineum and lesions sometimes go unnoticed.

At the same time, inguinal lymphadenopathy develops (usually unilateral) and can progress to form large buboes which suppurate.

Diagnosis and treatment

Chancroid must be differentiated from other genital ulcer diseases (see Table 4.47). Co-infection with syphilis and herpes simplex is common. Isolation of H. ducreyi, a fastidious organism, in specialized culture media is definitive but difficult. Swabs should be taken from the ulcer and material aspirated from the local lymph nodes for culture. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques are available. Gram stains of clinical material may show characteristic coccobacilli, but this is an insensitive test. Detection of antibody to H ducreyi using EIA may be useful for population surveillance but, at an individual level, lacks sensitivity and specificity. A ‘probable diagnosis’ may be made if the patient has the appropriate clinical picture, without evidence of T. pallidum or herpes simplex infection.

Single-dose regimens include azithromycin 1 g orally or ceftriaxone 250 mg i.m. Other regimens include ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily for 3 days, erythromycin 500 mg four times daily for 7 days. Clinically significant plasmid-mediated antibiotic resistance in H. ducreyi is developing.

Patients should be followed up at 3–7 days, when the ulcers should be responding if the treatment is successful.

Sexual partners should be notified, examined and treated epidemiologically, as asymptomatic carriage has been reported.

HIV-infected patients should be closely monitored, as healing may be slower. Multiple-dose regimens are needed in HIV patients since treatment failures have been reported with single-dose therapy.

Donovanosis

Donovanosis is the least common of all STIs in North America and Europe, but is endemic in the tropics and subtropics, particularly the Caribbean, South-east Asia and South India. Infection is caused by Klebsiella granulomatis, a short, encapsulated Gram-negative bacillus. The infection was also known as granuloma inguinale. Although sexual contact appears to be the most usual mode of transmission, the infection rates are low, even between sexual partners of many years’ standing.

Clinical features

In the vast majority of patients, the characteristic, heaped-up ulcerating lesion with prolific red granulation tissue appears on the external genitalia, perianal skin or the inguinal region within 1–4 weeks of exposure. It is rarely painful. Almost any cutaneous or mucous membrane site can be involved, including the mouth and anorectal regions. Extension of the primary infection from the external genitalia to the inguinal regions produces the characteristic lesion, the ‘pseudo-bubo’.

Diagnosis and treatment

The clinical appearance usually strongly suggests the diagnosis but K. granulomatis (Donovan bodies) can be identified intracellularly in scrapings or biopsies of an ulcer. Successful culture has only recently been reported and PCR techniques and serological methods of diagnosis are being developed, but none is routinely available.

Antibiotic treatment should be given until the lesions have healed. A minimum of 3 weeks’ treatment is recommended. Regimens include doxycycline 100 mg twice daily, co-trimoxazole 960 mg twice daily, azithromycin 500 mg daily or 1 g weekly, or ceftriaxone 1 g daily.

Sexual partners should be notified, examined and treated if necessary.

Herpes simplex (also see p. 1199)

Genital herpes is one of the most common STIs worldwide and the most common ulcerative STI in the UK. The peak incidence is in 16- to 24-year-olds of both sexes, with women having higher rates of diagnosis than men. Infection, which is lifelong, may be either primary or recurrent. Transmission occurs during close contact with a person who is shedding virus (who may well be asymptomatic). Historically, most genital herpes is due to HSV type 2. However, genital contact with oral lesions caused by HSV-1 can also produce genital infection and rates of HSV-1-associated genital herpes are approaching 50% in some parts of the world.

Susceptible mucous membranes include the genital tract, rectum, mouth and oropharynx. The virus has the ability to establish latency in the dorsal root ganglia by ascending peripheral sensory nerves from the area of inoculation. It is this ability which allows for recurrent attacks.

Clinical features

Primary genital herpes is usually accompanied by systemic symptoms of varying severity including fever, myalgia and headache. Multiple painful shallow ulcers develop, which may coalesce (Fig. 4.40). Atypical lesions are common. Tender inguinal lymphadenopathy is usual. Over a period of 10–14 days the lesions develop crusts and dry. In women with vulval lesions the cervix is almost always involved. Rectal infection may lead to a florid proctitis. Neurological complications can include aseptic meningitis and/or involvement of the sacral autonomic plexus leading to retention of urine. Asymptomatic primary infection has been reported but is rare. Serological surveys indicate that only about 10% of individuals with antibodies to HSV-2 give a clinical history of genital lesions, indicating that asymptomatic primary infection is the norm.

Recurrent attacks occur in a significant proportion of people following the initial episode and are more likely with HSV type 2 infections. Precipitating factors vary, as does the frequency of recurrence. A symptom prodrome is present in some people prior to the appearance of lesions. Systemic symptoms are rare in recurrent attacks.

The clinical manifestations in immunosuppressed patients (including those with HIV) may be more severe, asymptomatic shedding increased and recurrences occurring with greater frequency. Systemic spread has been documented (see p. 191).

Diagnosis

The history and examination can be highly suggestive of HSV infection.

A firm diagnosis can routinely be made only on the basis of detection of virus from within lesions.

A firm diagnosis can routinely be made only on the basis of detection of virus from within lesions.

Swabs should be taken from the base of lesions and placed in viral transport medium. Virus is most easily isolated from new lesions.

Swabs should be taken from the base of lesions and placed in viral transport medium. Virus is most easily isolated from new lesions.

HSV DNA detection by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) has increased the rates of detection compared with virus culture.

HSV DNA detection by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) has increased the rates of detection compared with virus culture.

Real-time PCR assays are highly specific although not available in all laboratories.

Real-time PCR assays are highly specific although not available in all laboratories.

Type-specific immune responses can be found 8–12 weeks following primary infection and indicate HSV infection at some time. False negatives may be found early after infection. IgM assays are unreliable.

Management

Primary. Saltwater bathing or sitting in a warm bath is soothing and may allow the patient to pass urine with some degree of comfort. Aciclovir 200 mg five times daily, famciclovir 250 mg three times daily or valaciclovir 500 mg twice daily, all for 5 days, are useful if patients are seen while new lesions are still forming. If lesions are already crusting, antiviral therapy will do little to change the clinical course. Secondary bacterial infection occasionally occurs and should be treated. Rest, analgesia and antipyretics should be advised.

Primary. Saltwater bathing or sitting in a warm bath is soothing and may allow the patient to pass urine with some degree of comfort. Aciclovir 200 mg five times daily, famciclovir 250 mg three times daily or valaciclovir 500 mg twice daily, all for 5 days, are useful if patients are seen while new lesions are still forming. If lesions are already crusting, antiviral therapy will do little to change the clinical course. Secondary bacterial infection occasionally occurs and should be treated. Rest, analgesia and antipyretics should be advised.

Recurrence. Recurrent attacks tend to be less severe and can be managed with simple measures such as saltwater bathing. Psychological morbidity is associated with recurrent genital herpes and frequent recurrences impose strains on relationships; patients need considerable support. Long-term suppressive therapy is given in patients with frequent recurrences. An initial course of aciclovir 400 mg twice daily or valaciclovir 250 mg twice daily for 6–12 months significantly reduces the frequency of attacks, although there may still be some breakthrough. Therapy should be discontinued after 12 months and the frequency of recurrent attacks reassessed.

Recurrence. Recurrent attacks tend to be less severe and can be managed with simple measures such as saltwater bathing. Psychological morbidity is associated with recurrent genital herpes and frequent recurrences impose strains on relationships; patients need considerable support. Long-term suppressive therapy is given in patients with frequent recurrences. An initial course of aciclovir 400 mg twice daily or valaciclovir 250 mg twice daily for 6–12 months significantly reduces the frequency of attacks, although there may still be some breakthrough. Therapy should be discontinued after 12 months and the frequency of recurrent attacks reassessed.

HSV in pregnancy

The potential risk of infection to the neonate needs to be considered in addition to the health of the mother. Infection occurs either transplacentally (very rare) or via the birth canal. If HSV is acquired for the first time during pregnancy, transplacental infection of the fetus may, rarely, occur. Management of primary HSV in the 1st or 2nd trimester will depend on the woman’s clinical condition and aciclovir can be prescribed in standard doses. Aciclovir, given at a dose of 400 mg three times a day to accommodate altered pharmacokinetics of the drug in late pregnancy, during the last 4 weeks of pregnancy, may prevent recurrence at term.

Symptomatic primary acquisition in the 3rd trimester or at term with high levels of viral shedding usually leads to delivery by caesarean section.

For women with previous infection, the risk for the baby acquiring HSV from the birth canal is very low in recurrent attacks. Only those with genital lesions at the onset of labour are delivered by caesarean section. Sequential cultures during the last weeks of pregnancy to predict viral shedding at term are no longer indicated.

Prevention and control

Patients must be advised that they are infectious when lesions are present; sexual intercourse should be avoided during this time or during prodromal stages. Condoms may not be effective as lesions may occur outside the areas covered. Sexual partners should be notified, examined and given information on avoiding infection. Asymptomatic viral shedding is a cause of onward transmission. It is most common in HSV-2, during the first 12 months following infection and in those with frequent symptomatic HSV. Antiviral drugs reduce shedding and onward transmission.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) warts

Anogenital warts are among the most common sexually acquired infections. The causative agent is human papillomavirus (HPV), especially types 6 and 11 with types 16 and 18 causing a majority of cases of cervical carcinoma (see p. 100). HPV is acquired by direct sexual contact with a person with either clinical or subclinical infection. Genital HPV infection is common, with only a small proportion of those infected being symptomatic. Neonates may acquire HPV from an infected birth canal, which may result either in anogenital warts or in laryngeal papillomas. The incubation period ranges from 2 weeks to 8 months or even longer.

Clinical features

Warts develop around the external genitalia in women, usually starting at the fourchette, and involve the perianal region. The vagina may be infected. Flat warts may develop on the cervix and are not easily visible on routine examination. Such lesions are associated with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. In men, the penile shaft and subpreputial space are the most common sites, although warts involve the urethra and meatus. Perianal lesions are more common in men who practise anoreceptive intercourse but they can be found in any patient. The rectum may become involved. Warts become more florid during pregnancy or in immunosuppressed patients.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is essentially clinical. It is critical to differentiate condylomata lata of secondary syphilis. Unusual lesions should be biopsied if the diagnosis is in doubt. Up to 30% of patients have co-existing infections with other STIs and a full screen must be performed.

Treatment

Significant failure and relapse rates are seen with current treatment modalities. Choice of treatment will depend on the number and distribution of lesions. Local agents, including podophyllin extract (15–25% solution, once or twice weekly), podophyllotoxin (0.5% solution or 1.5% cream in cycles) and trichloroacetic acid, are useful for non-keratinized lesions. Those that are keratinized respond better to physical therapy, e.g. cryotherapy, electrocautery or laser ablation. Imiquimod, an immune response modifier, induces a cytokine response when applied to skin infected with HPV (5% cream used three times a week) and is indicated in both types of lesion. Podophyllin, podophyllotoxin and imiquimod are not advised in pregnancy. Patients co-infected with HIV may have a poorer response to treatment and higher rates of intraepithelial neoplasia. Sexual contacts should be examined and treated if necessary. In view of the difficulties of diagnosing subclinical HPV, condoms should be used for up to 8 months after treatment. Because of the association of HPV with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, women with warts and female partners of men with warts are advised to have regular cervical screening, i.e. every 3 years. Colposcopy may be useful in women with vaginal and cervical warts.

Prevention/vaccination

Two vaccines exist against HPV. One is effective against HPV types 16 and 18 and the second against types 6, 11, 16 and 18. Both vaccines, based on a DNA-free HPV capsid, are strongly immunogenic and act by inducing a neutralizing antibody response and enhancing CD4 memory cell function. They are given over 6 months in three divided doses, with an excellent safety profile. Up to 98% serological responses, maintained for over 4 years, have been reported from early trials. In placebo-controlled clinical trials of the quadrivalent vaccine a highly significant reduction in low- and high-grade cervical dysplasia, vulval pre-cancers and external genital warts has been demonstrated. Vaccination is most beneficial in those who have not yet been exposed to HPV infection, with a recommendation that it be given before people become sexually active. Although initially considered to be most useful for women and girls, vaccination of boys to prevent both genital warts and the transmission of oncogenic HPV strains is under consideration. Routine HPV vaccination commenced in the UK in late 2008, initially for girls of about 12 years of age, with a second catch-up opportunity at about 18 years of age.

Hepatitis B

This is discussed in Chapter 7. Sexual contacts should be screened and given vaccine if they are not immune (see p. 318).

Trichomoniasis

Trichomonas vaginalis (TV) is a flagellated protozoon which is predominantly sexually transmitted. It is able to attach to squamous epithelium and can infect the vagina and urethra. Trichomonas may be acquired perinatally in babies born to infected mothers.

Infected women may, unusually, be asymptomatic. Commonly the major complaints are of vaginal discharge, which is offensive and of local irritation. Men usually present as the asymptomatic sexual partners of infected women, although they may complain of urethral discharge, irritation or urinary frequency.

Examination often reveals a frothy yellowish vaginal discharge and erythematous vaginal walls. The cervix may have multiple small haemorrhagic areas which lead to the description ‘strawberry cervix’. Trichomonas infection in pregnancy has been associated with pre-term delivery and low birth weight.

Diagnosis and treatment

Phase-contrast, dark-ground microscopy of a drop of vaginal discharge shows TV swimming with a characteristic motion in 40–80% of female patients. Similar preparations from the male urethra will only be positive in about 30% of cases. Many polymorphonuclear leucocytes are also seen. Culture techniques are good and confirm the diagnosis. Trichomonas is sometimes observed on cervical cytology with 60–80% accuracy in diagnosis. New, highly sensitive and specific tests based on polymerase chain reactions are being developed.

Metronidazole is the treatment of choice, either 2 g orally as a single dose or 400 mg twice daily for 7 days. There is some evidence of metronidazole resistance and nimorazole may be effective in these cases. Topical therapy with intravaginal tinidazole can be effective, but if extravaginal infection exists this may not be eradicated and vaginal infection reoccurs. Male partners should be treated, especially as they are likely to be asymptomatic and more difficult to detect.

Candidiasis

Vulvovaginal infection with Candida albicans is extremely common. The organism is also responsible for balanitis in men. Candida can be isolated from the vagina in a high proportion of women of childbearing age, many of whom will have no symptoms.

The role of Candida as pathogen or commensal is difficult to disentangle and it may be changes in host environment which allow the organism to produce pathological effects. Predisposing factors include pregnancy, diabetes and the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics and corticosteroids. Immunosuppression can result in more florid infection.

Clinical features

In women, pruritus vulvae is the dominant symptom. Vaginal discharge is present in varying degrees. Many women have only one or occasional isolated episodes. Recurrent candidiasis (four or more symptomatic episodes annually) occurs in up to 5% of healthy women of reproductive age. Examination reveals erythema and swelling of the vulva with broken skin in severe cases. The vagina may contain adherent curdy discharge. Men may have a florid balanoposthitis. More commonly, self-limiting burning penile irritation immediately after sexual intercourse with an infected partner is described. Diabetes must be excluded in men with balanoposthitis.

Diagnosis

Microscopic examination of a smear from the vaginal wall reveals the presence of spores and mycelia. Culture of swabs should be undertaken but may be positive in women with no symptoms. Trichomonas and bacterial vaginosis must be considered in women with itch and discharge.

Treatment

Topical. Pessaries or creams containing one of the imidazole antifungals such as clotrimazole 500 mg single dose used intravaginally are usually effective. Nystatin is also useful.

Oral. The triazole drugs such as fluconazole 150 mg as a single dose or itraconazole 200 mg twice in 1 day are used systemically where topical therapy has failed or is inappropriate. Recurrent candidiasis may be treated with fluconazole 100 mg weekly for 6 months or clotrimazole pessary, 500 mg weekly for 6 months.

The evidence for sexual transmission of Candida is slight and there is no evidence that treatment of male partners reduces recurrences in women.

Bacterial vaginosis

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is a disorder characterized by an offensive vaginal discharge. The aetiology and pathogenesis are unclear but a mixed flora of Gardnerella vaginalis, anaerobes including Bacteroides, Mobiluncus spp. and Mycoplasma hominis replaces the normal lactobacilli of the vagina. Amines and their breakdown products from the abnormal vaginal flora are thought to be responsible for the characteristic odour associated with the condition. As vaginal inflammation is not part of the syndrome, the term vaginosis is used rather than vaginitis. The condition has been shown to be more common in black women than in white. It is not regarded as a sexually transmitted disease.

Clinical features

Vaginal discharge and odour are the commonest complaints, although a proportion of women are asymptomatic. A homogeneous, greyish white, adherent discharge is present in the vagina, the pH of which is raised (>5). Associated complications are ill-defined but may include chorioamnionitis and an increased incidence of premature labour in pregnant women. Whether BV predisposes non-pregnant women to upper genital tract infection is unclear.

Diagnosis

Different authors have differing criteria for making the diagnosis of BV. In general, it is accepted that three of the following should be present for the diagnosis to be made:

Characteristic vaginal discharge

Characteristic vaginal discharge

The amine test: raised vaginal pH using narrow-range indicator paper (>4.7)

The amine test: raised vaginal pH using narrow-range indicator paper (>4.7)

A fishy odour on mixing a drop of discharge with 10% potassium hydroxide

A fishy odour on mixing a drop of discharge with 10% potassium hydroxide

The presence of ‘clue’ cells on microscopic examination of the vaginal fluid.

The presence of ‘clue’ cells on microscopic examination of the vaginal fluid.

Clue cells are squamous epithelial cells from the vagina, which have bacteria adherent to their surface, giving a granular appearance to the cell. A Gram stain gives a typical reaction of partial stain uptake.

Treatment

Metronidazole given orally in doses of 400 mg twice daily for 5–7 days is usually recommended. A single dose of 2 g metronidazole is less effective. Topical 2% clindamycin cream 5 g intravaginally once daily for 7 days is effective.

Recurrence is high, with some studies giving a rate of 80% within 9 months of completing metronidazole therapy. There is debate over the treatment of asymptomatic women who fulfil the diagnostic criteria for BV. Until the relevance of BV to other pelvic infections is elucidated, the treatment of asymptomatic women with BV is not to be recommended. Simultaneous treatment of the male partner does not influence the rate of recurrence of BV and routine treatment of male partners is not indicated.

Infestations (see also Chapter 24)

Pediculosis pubis

The pubic louse (Phthirus pubis) is a blood-sucking insect which attaches tightly to the pubic hair. They may also attach to eyelashes and eyebrows. It is relatively host-specific and is transferred only by close bodily contact. Eggs (nits) are laid at hair bases and usually hatch within a week. Although infestation may be asymptomatic, the most common complaint is of itch.

Diagnosis

Lice may be seen on the skin at the base of pubic and other body hairs. They resemble small scabs or freckles but if they are picked up with forceps and placed on a microscope slide, will move and walk away. Blue macules may be seen at the feeding sites. Nits are usually closely adherent to hairs. Both are highly characteristic under the low-power microscope.

As with all sexually transmitted infections, the patient must be screened for co-existing pathogens.

Treatment

Both lice and eggs must be killed with 0.5% malathion, 1% permethrin or 0.5% carbaryl. The preparation should be applied to all areas of the body from the neck down and washed off after 12 h. In a few cases, a further application after 1 week may be necessary. For severe infestations, antipruritics may be indicated for the first 48 h. All sexual partners should be seen and screened.

Scabies

This is discussed in Chapter 24.

FURTHER READING

British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH). BASHH Clinical Effectiveness Guidelines. London: BASHH; 2008. Also online. Available at: http://www.bashh.org/guidelines.asp

Gupta R, Warren T, Wald A. Genital herpes. Lancet 2007; 370:2127–2137.

Low N, Broutet N, Adu-Sarkodie Y et al. Global control of sexually transmitted infections. Lancet 2006; 368:2001–2016.

Robertson C, Jayasuriya A, Allan PS. Sexually transmitted infections: where are we now? J R Soc Med 2007; 100:414–417.

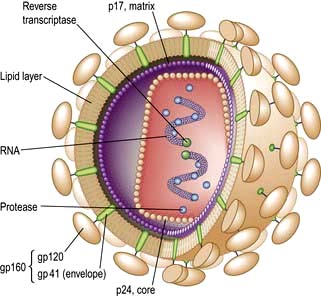

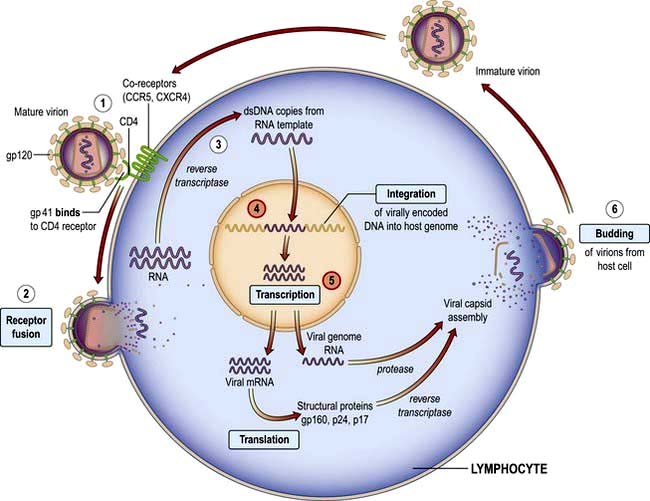

Human immune deficiency virus (HIV) and AIDS

Epidemiology

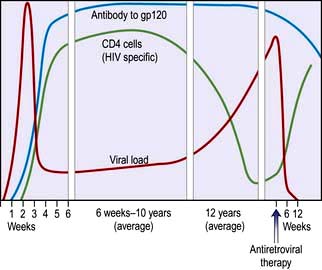

Since the first description of AIDS in 1981 and the identification of the causative organism HIV in 1984, more than 20 million people have died. At least 33 million people worldwide are living with HIV infection. Sub-Saharan Africa remains the most seriously affected, but in some areas, the number of new diagnoses has stabilized. However, in Eastern Europe and parts of central Asia, infection rates are rising exponentially. The human, societal and economic costs are huge: 33% of 15-year-olds in high-prevalence countries in Africa will die of HIV. Demographics of the epidemic have varied greatly, influenced by social, behavioural, cultural and political factors. Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has dramatically reduced mortality for those who are able to access care. Current global estimates suggest that about a quarter of those who need HAART are on treatment but that for each individual starting therapy there are two new infections, highlighting the size of the problem and the global inequalities that exist in healthcare.

In the UK falling death rates and continued new infections mean that the total number of people living with HIV continues to rise. Men who have sex with men (MSM) and culturally diverse heterosexual populations from sub-Saharan Africa, are the two largest groups of people living with HIV in the UK, and accessing treatment and care. Of those diagnosed with HIV in the UK, 30% are women. As mortality rates fall so the population of people with HIV is becoming older, further changing the clinical picture.

Approximately one-quarter of those with HIV infection in the UK are undiagnosed and unaware of their infection, which contributes to late diagnosis, poorer clinical outcomes and onward transmission. Late diagnosis is now the most common cause of HIV-related morbidity and mortality in the UK. Reducing undiagnosed HIV through wider testing, particularly in patients presenting with clinical conditions that are associated with HIV and in areas with high seroprevalence, is critical to both the individual and public health (Box 4.21).

![]() Box 4.21 HIV testing

Box 4.21 HIV testing

UK guidelines on where and who to test

2. people in whom hiv testing is recommended

All patients diagnosed with a sexually transmitted infection

All patients diagnosed with a sexually transmitted infection

Sexual partners of men and women known to be HIV positive

Sexual partners of men and women known to be HIV positive

Men who have disclosed sexual contact with other men

Men who have disclosed sexual contact with other men

Female sexual contacts of men who have sex with men

Female sexual contacts of men who have sex with men

People reporting a history of injecting drug use

People reporting a history of injecting drug use

Men and women known to be from a country of high HIV prevalence (>1%)

Men and women known to be from a country of high HIV prevalence (>1%)

Men and women who report sexual contact abroad or in the UK with individuals from countries of high HIV prevalence

Men and women who report sexual contact abroad or in the UK with individuals from countries of high HIV prevalence

Patients presenting for healthcare where HIV enters the differential diagnosis (see below for table of indicator conditions)

Patients presenting for healthcare where HIV enters the differential diagnosis (see below for table of indicator conditions)

Hiv-associated indicator conditions

Neurology

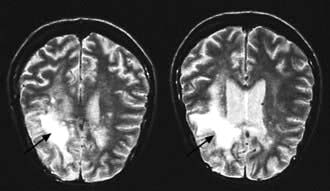

Cerebral toxoplasmosisa; primary cerebral lymphomaa; cryptococcal meningitisa; progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathya; aseptic meningitis/encephalitis; cerebral abscess; space-occupying lesion of unknown cause; Guillain–Barré syndrome; transverse myelitis; peripheral neuropathy; dementia.

Dermatology

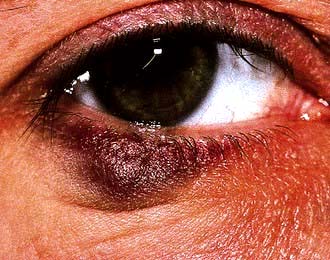

Kaposi’s sarcomaa; severe/recalcitrant seborrhoeic dermatitis; severe/recalcitrant psoriasis; multidermatomal/recurrent herpes zoster.

Gastroenterology

Persistent cryptosporidiosisa; oral candidiasis; oral hairy leukoplakia; chronic diarrhoea of unknown cause; weight loss of unknown cause; Salmonella; Shigella; Campylobacter; hepatitis B infection; hepatitis C infection.

Oncology

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphomaa; anal cancer; anal intraepithelial dysplasia; lung cancer; seminoma; head and neck cancer; Hodgkin’s lymphoma; Castleman’s disease.

Gynaecology

Cervical cancera; vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia; cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, grade 2 or above.

Haematology

Any unexplained blood dyscrasia including thrombocytopenia, neutropenia and lymphopenia.

Opthalmology

Cytomegalovirus retinitisa; infective retinal diseases including herpesviruses and toxoplasma; any unexplained retinopathy.

http://guidance.nice.org.uk/PH33; http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/PH34; http://www.bhiva.org/HIVTesting2008.aspx

a AIDS-defining condition.