Chapter 9 Relationship, helping and communication skills

Introduction

This chapter explores how knowledge of communication, language and interpersonal skills can enhance professional nursing practice and nursing relationships. Such knowledge and skills are relevant to all the other chapters of the book. This chapter considers how people understand language and communication and presents various frameworks and activities for the reader to practise with the aim of developing their interpersonal skills and thus the quality of the care and positive relationships and interactions they are able to engage in with patients/clients/children, carers and colleagues.

Well-developed interpersonal and communication skills are considered essential for all nurses, regardless of where they work. This is evidenced by the addition of benchmarks for best practice in communication to the original eight sets of benchmarks in the Essence of Care document (NHS Modernisation Agency 2003). Nurses need to be critical of their communication skills in the care environment and need to be able to provide evidence of how they actually meet the information, communication and linguistic needs of patients, clients, children, families and carers (Box 9.1).

Benchmarks for communication

Agreed patient-focused outcome (NHS Modernisation Agency 2003):

‘Patients and carers experience effective communication sensitive to their individual needs and preferences, which promotes high quality care for the patient.’

Student activities

[Resource: NHS Modernisation Agency 2003 Essence of care: patient-focused benchmarks for clinical governance – www.modern.nhs.uk/home/key/docs/Essence%20of%20Care.pdf Available July 2006]

There is a focus on a number of skills and techniques that will enhance the nurse’s ability to deliver care within the context of a positive and empowering communication environment. Developing communication skills takes practice, as does any nursing skill, but with practice comes the ability to quickly develop working and therapeutic relationships, thus enhancing people’s experience of healthcare.

The primary aim of this chapter is to enable the reader to recognize when communication is appropriate and also how to improve communicative and interpersonal skills. Most of the time people manage communication and relationships correctly; however, because these aspects of language are so innate, people often resort to habitual ways of being with people. Often these habits will be appropriate but they can also create problems that may result in difficulties in interacting effectively with people. For example, a nurse may offend or pos-sibly damage relationships with patients/clients/children, carers and colleagues. There is a great need for nurses to consider exactly what they say to people, how they say it and how this affects them.

If nurses are serious about good interpersonal skills they may start to feel a little anxious about communication if they are not sure about saying or doing the right thing. Feeling unsure is good, as it indicates that nurses are starting to think carefully and more critically about what they say to people, how they relate to them and how this affects their experience of health professionals.

Another aim of the chapter is to bring readers out of the unconscious competence zone and for them to work within the conscious competence and conscious incompetence areas. The zones of learning and experience are:

There is considerable debate about the origin of this model, which can be found at www.businessballs.com.

Focusing on Gibbs’ (1988) reflective model (see Ch. 4) will also encourage nurses to consider more deeply their thoughts, feelings and behaviours; it will bring communication to the forefront of the mind and, by so doing, move understanding from an innate level – an unconscious competence level – to a more considered consciously competent level.

Good communication offers pathways into relationships between individuals and ultimately the ability to effectively care for people. Caring for someone entails looking after their needs on many different levels – from physical needs to emotional support, from information giving to working in partnership. Caring is a deeply held value for nurses and, to communicate this care, nurses must show concern, attention, empathy and respect, and focus on people’s needs.

Communication theory

People are ‘wired’ to communicate, to develop language, reason, empathy and even storytelling skills. Parents and main carers are innately skilled in developing the language ability of their children; people have the capability and importantly the motivation to match the communication needs of other people in various situations and from diverse cultures, social strata and backgrounds. Pinker (1994) suggests that people are born with the ability and the language faculty to understand any natural language. This faculty is like no other learning experience: it does not require conscious effort and exceeds all other notions of learning theory – all it needs is to be stimulated by a language environment.

Despite these innate abilities, people still make errors when communicating with others; some errors are small, such as ‘pacifically speaking’ rather than ‘specifically speaking’, but others are more serious. Practitioners who assume that the patient/client/child cannot understand what is being said in their presence may cause them anxiety or fear, and can create feelings of hostility.

Models for communication

A number of models are outlined below. These include Lasswell’s model, the blueprint of behaviour model and a model derived from Shannon and Weaver’s model.

Lasswell’s model of communication

In 1948 Lasswell devised a very effective model of the communication process which can be used for any communication interaction (Fiske 1993). In daily life almost everything involves communication – from nursing hand-over to lectures, conversations with family to addressing a conference, from singing a nursery rhyme to a child to seeing a live band perform. Lasswell’s model looks at communication as a process that has an effect on (influences) the receiver’s behaviour to some degree (Fig. 9.1).

Box 9.2 explores some of the questions associated with the components of Lasswell’s model.

Exploring Lasswell’s model

Who?

Who is sending the message? Is it a friend, patient/client or someone trying to sell something? What are their language and communication skills? What is my relationship with this person? What is their agenda, their ultimate objective in communicating?

What?

What is the message they are sending? Does it relate to me? What knowledge will help me to understand the message and respond appropriately?

To whom?

To whom are they sending the message? Is it to me alone, or are millions of people receiving this message through an advertisement on television, or hundreds of people who work at a particular hospital?

Which channel?

Which channel of communication are they using – visual media, gestural/visual, spoken/hearing, light, sound, vibration, touch, smell, taste? Channels are as flexible as the senses – smells often communicate deep memories for people, and sounds (e.g. music, speech, rhythms) can influence people’s emotional states, both positively and negatively. People tend to have a stronger preference for receiving information either visually, through their auditory channel (see p. 224), or kinaesthetically, through touch or feelings. Usually people prefer a mix of channels and media: the more access to information they have through a variety of media, the more likely they are to understand the message and to remember it.

With what effect?

All communication has an effect on the parties involved. The effect for a nurse may be to respond appropriately to clients’ needs, to help a small child to accept a medical procedure or to encourage a client to make an informed choice about their health needs. In a wider context the communication may influence people to buy a new sofa, to eat in a certain restaurant or to develop a political opinion.

Lasswell’s model provides information about the communication process. However, to ‘understand how to understand’ this process and how people make choices in this process, it is important to consider the influences on people’s perception of the world. For example, the design of buildings communicates a message. Hospitals may communicate clinical specialities, care, security and cleanliness, or quite the opposite (Box 9.3).

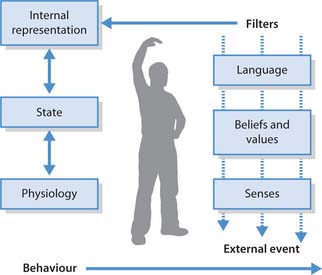

Blueprint of behaviour model

The neurolinguistic programming (NLP) model showing the blueprint of behaviour is a useful tool in appreciating how people understand the world around them, how this influences the way the person will communicate and therefore how others may respond to them (Fig. 9.2, see p. 224).

Everyone has unique life experiences that influence the way they understand the world. The senses are also unique: people see, hear, smell, touch and taste in ways that are particular to them. The language used and understood is also unique to and influenced by background, social class, education, family, spirituality and cultural heritage. Given so many individual distinctions, it is thepredisposition to communicate that enables people to create such effective connections with others.

However, language, senses, experiences, beliefs and values can act as filters that affect the way people interpret and internalize external stimuli and this determines the way people communicate and behave with others. The term ‘filter’ represents the physiological and neurological processes that act on information as it comes through the senses and into language, values and belief systems. Filtered external stimuli are internally represented and understood by each individual in a different way. These representations influence emotions, which in turn influence the language used and people’s subsequent behaviour.

Understanding how these filters create accessible or inaccessible pathways between individuals and groups enables nurses to be clear and creative in communicating often vital information to patients/clients, carers and colleagues.

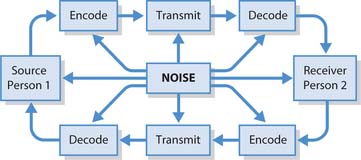

A model derived from Shannon and Weaver’s model

A simple communication model, derived from Shannon and Weaver’s model (Fiske 1993), provides a description of the communication process between two people (Fig. 9.3): person 1 encodes, creates their message and transmits it to person 2 who decodes the message for meaning, and encodes or creates a response, which is transmitted to person 1 to decode and understand.

It would be useful to consider this model while at the same time keeping the blueprint of behaviour model in mind. It helps to build a picture of the factors that affect:

Communication process – getting the message across

Most people have a preference for either the auditory or the visual channel for sending and receiving messages (see p. 223), but choosing the most appropriate channel is vital for effective communication.

For example, the sender thinks of an idea which will have been triggered by an internal or external event. The thought/message is encoded into words in the brain; the message is then transmitted from the brain to the structures involved in voice production (e.g. larynx, tongue, palate and lips), to the outside world and the listener The listener picks up the sound through the ears and the sound is transmitted along the vestibulocochlear (auditory) nerves to the brain. There it is decoded and understood by the listener who will react to the message and feed back to the sender.

At any point in this sequence noise can influence the quality of the message. A noise could be environmental interference, such as a noisy environment where people are competing to be heard, or clinical equipment beeping and buzzing. It may be that the person is experiencing pain and is concentrating on this rather than on the person speaking.

Other major influences on the communication process in care settings are language differences, anxiety, fear and anger. People who are experiencing extremes of emotions are not in a position to fully understand a message, e.g. a distressed relative in the Emergency Department. People who have mental distress or are experiencing hallucinations find that their ability to comprehend others can be limited.

Noise changes the message. To understand how it has been changed the sender relies on the listener’s feedback or a change in behaviour to check if the message has been understood. In a situation where the message is clear and understood, the sender may not need to go further. If the message was not understood, the sender takes the responsibility for adjusting the message and possibly the channel chosen to transmit the message in an attempt to succeed in communicating their idea (Box 9.4).

Getting the message across

The feedback from a patient/client was to tap their ear, shake their head and shrug their shoulders. The nurse may think that they have not heard the message:

By ruling out many possibilities, the nurse may conclude that the person is deaf or hard of hearing. If the nurse has sign language skills and encodes the message in sign, the visual channel can be used to transmit the message through hand shapes, facial expressions and body movement. The patient/client receives and understands the message via the visual channel. Feedback could be a smile and thumbs up.

Acknowledging potential noise in the communication process enables the nurse to adjust the message accordingly. Thus the nurse is ‘accommodating’ the communication rather than ‘diverging’ from the needs of the other person (see p. 230).

Similar, but more complex skills are needed in specific situations. For example, when nurses communicate with a person with a learning disability the communication is determined by the nurse’s knowledge of the person and their linguistic and cognitive ability. Carers, friends, family and speech and language therapists (SLTs) often inform this knowledge (Box 9.5).

Box 9.5 People with learning disabilities – assessing communication difficulties

Children and adults with a learning disability may face greater challenges in acquiring language. These difficulties not only relate to their cognitive development but also to the physical problems that coincide with some developmental differences. They may have problems with articulation, expressive language or receptive language (see pp. 227–228).

Structured assessments by the multidisciplinary team (MDT), comprising audiologist, SLT, ophthalmologist and physiotherapist, are therefore vital to this client group.

Following the assessments, the MDT plans interventions with the client, family and carers to facilitate the client’s move towards communicative competence. These are evaluated and the plan reviewed on a regular basis.

Language

Earlier sections have emphasized that each person has a different blueprint of behaviour with unique challenges, the ability to change, to develop and, in the case of the senses, to deteriorate. Choices in communication are dependent on many factors, one of the most important of which is language.

All human languages comprise words or signs, sounds, visual movement, rules, grammar, vocabulary, knowledge of meaning and creativity. All languages are complex and based on a finite number of sounds or hand shapes, if it is a sign language. All languages provide the users with the ability to produce an infinite number of sentences (Crystal 1999).

Many people feel that language is a complicated and difficult subject with hidden depth and unseen trickery that make the idea of learning a new language unattainable. Babies and children learning their first language do not have these anxieties; they usually have a natural curiosity that supports language acquisition. Play is an important component in the processes involved in language development. Depending on a child’s age and stage of development, one of the main sources of communication with children is through play (see pp. 226–227).

Language development in children

Language development is vital for a child to progress from a point where they are unable to express thoughts, feeling or behaviours to one where they can express abstract thoughts, complex emotions, describe intricate behaviours and develop engaging relationships with others (Box 9.6, see p. 226).

Box 9.6 Normal early language development

Box 9.7 (see p. 226) provides an opportunity to reflect on a situation involving communication with a child.

Communicating with children

Think of a child that you have spent time with in a caring capacity.

Student activities

Using Gibbs’ (1988) model of reflection, consider the following questions:

Children who are denied access to a language environment have problems acquiring language. ‘Feral’ children or children who experience severe neglect are confounded by the complexity of language rules and social relationships, particularly if they are not discovered until later childhood. It appears that, if not appropriately stimulated, nerve pathways become obsolete and children have problems developing and using the more complex language rules.

Play as a communication tool

Most people can recollect the games they played with other children and adults as they grew up. Rememberingimaginary stories that were re-enacted, games with rules, games with songs and deep attachments to favourite toys can give a sense of happiness. Play is crucial to language development, understanding relationships and developing an understanding of ‘self’ and how the ‘self’ relates to the outside world.

In all societies children have a drive to play. Essentially play enables the child to make sense of the world around them, the relationships with others, the meaning of idea, and to develop language and strategies to enable them to function in their society.

Play is of vital importance for children who are either in receipt of healthcare or for children who are trying to understand and come to terms with illness, disability and death (see Ch. 12) in their family. Nurses can provide enhanced support for children by their ability to utilize play in the child–nurse relationship.

Babies use ‘practice’ play to understand their movements and sensations. Play is vital in developing control over gross and fine motor movements to start interacting with the world. This involves grasping, taking objects to the mouth, pulling, hitting, clapping, pushing, grabbing and moving objects, fitting one inside the other, delighting in the movement of the objects and the interaction and responses of parental figures. Babies continue with the trial and error approach to affecting change on objects in their environment, e.g. rolling balls away by pushing or discovering that hard objects make louder noises than soft objects.

During the second year children continue to develop by using play to explore more complex ideas, e.g. learning to feed themselves by pretend feeding of adults or toys. Adults actively encourage pretend play but their interactions are often triggered and controlled by the child who leads the play. This play encourages person-to-person interactions; it helps the child to modify behaviour according to the reactions of others. It also enables the child to practise social skills such as turn taking, waiting, requesting, constructing and destructing scenarios.

Preschool children delight in ‘rough and tumble’ using large pieces of furniture or nursery props to design sets for play. This play is vital for the development of coordina-tion, muscle development, playing with others, fighting battles against good and evil. This helps children understand a wider range of emotions and strategies for life.

From the age of about 4 years children start to understand games with rules; these games have a number of ways to support the development of the person. All games for two or more players require communication and language skills. They develop the child’s understanding of competition, fair play, choosing a team, working together and developing a defensive or offensive strategy to win. The child develops a sense of what it means to belong to a group, and how to form and work in a group. Games with rules can be a major part in developing a child’s self-esteem and self-awareness, and understanding their own skills and limitations.

Pretend play allows the child to develop and practise life skills. Children use the scenarios around them to develop their meaning of the world. Children will role-play scenes from family interactions, taking on the role of carer or healer, and developing skills in looking after others. They will also use information from wider cultural roles, from the media and current characters such as Postman Pat or an action hero/heroine. Objects are used to trigger play, e.g. dressing-up boxes can provide an infinite range of possibilities. Children can use pretend play to work through conflict situations, negotiate results and stage the scenarios so that they can understand or impose their views and wishes on the events.

Nurses and play specialists utilize play with children in a number of ways, such as in relation to painful or invasive interventions. Play becomes the communication vehicle for identified aims for the child’s care (Table 9.1).

Table 9.1 Therapeutic play – uses in healthcare

| Aim | Process |

|---|---|

| Distracting the child from a procedure they may find upsetting or painful | Identifying the type of play appropriate to the age of the child, the nurse will use play to focus the child’s concentration away from the procedure |

| To give information | The nurse will use toys and other media such as paints, modelling materials, online games and specifically designed dolls to inform the child about their health |

| Play as a ‘normal’ child function, which promotes physical and psychological development | Nurses and play therapists will use play to create a sense of normality for children in situations that are not normal |

| Play can be a valuable coping strategy for children to use | |

| To assess a child’s development | Specialist practitioners use play as an assessment tool to ascertain the child’s stage of development, thus identifying any deficits in the child’s cognitive, linguistic, emotional or physical development |

| All nurses should be able to identify any obvious differences in the age of a child and their level of play, language and social interactions | |

| To encourage the child to express their fears and wishes | Provide toys and creative materials to assist a child in expressing their thoughts without the child having to resort to language |

| Children need space and time to develop their understanding and the language of new or emotionally difficult issues and toys provide this opportunity | |

| To assist the child’s parents in their appreciation of how the child understands their situation | Involve parents in the child’s play and help parents to understand the concepts the child is working on |

| Help parents link the play themes to the child’s situation so that they can support the child in this process |

Adults also play, and many care environments, e.g. mental health units, provide facilities for play, e.g. board games, pool or table tennis. Play with adults has a number of benefits; it:

Developmental problems – receptive and expressive language

Developmental problems of language may affect reception and/or expression of language.

Children who have hearing loss have problems developing language because they cannot receive sound information in a meaningful way. It is crucial to provide access to language for the child in a mode that is accessible. Children with a useful residual level of hearing may be helped by hearing aids or a cochlear implant depending on the cause of the hearing loss. These children develop speech, comprehension and expression by relying on aids and lipreading. For children from signing families, or for children whose residual hearing is not at a level that would facilitate understanding, sign language is preferable. Children who learn to sign from an early age follow the same developmental process as children learning speech.

Children who are deaf–blind face immense challenges in learning language. SLTs, parents/carers, educators and support groups such as Sense (www.sense.org.uk) support their language development very closely.

Children with cerebral palsy may have difficulties in speech production (expression) due to lack of muscle control. Nurses need to be aware that people with cerebral palsy may take longer to express themselves; people who are familiar with their speech may be helpful in understanding the person. However, it is important to be aware that family members acting as interpreter may be neither wanted nor appropriate (see pp. 247, 248–249).

Children with a cleft palate and/or cleft lip may also experience difficulty in speech production. Cleft palate is an abnormal opening in the palate that connects the nasal and oral cavities; this may also involve the upper lip. Most cleft palate problems are swiftly and effectively rectified by early surgery but input from specialist dental/orthodontic services and an SLT may be needed.

Language styles and influences

The way people communicate with others depends on a number of influences that are usually subconscious. Nurses will find it useful to understand why they speak to people the way they do and how this is dependent on the situation, the people they are communicating with and the background of everyone involved.

Formality

Consider the following statements:

The same person spoke each sentence but in different situations, at home with his partner, during shift handover and in a court of law. It is obvious which statement was used in each situation, but what is it about the sentence that fits the context in which it is spoken? The level of formality in each situation determines the level of formality in the language used.

The first sentence suggests an informal setting, a friendship or relationship with a person not involved in the speaker’s work life. Not a great deal of factual information is given because of confidentiality (see Ch. 6). Social information is provided to inform the listener of the speaker’s feelings.

The second sentence is more formal, the context supports increased information about the patient rather than the member of staff. The sentence does suggest some informality initially, which can have a positive effect on team and individual connections, though it moves quickly on to deal with the pertinent issue of care.

The final sentence is very formal, there is a high degree of clarity, and more words are used to provide detailed information. There are no feelings expressed at all. People would certainly find it odd if people spoke in this way on a daily basis; it is highly structured and by the absence of emotional information it lacks any social use and could estrange the listener. In a court situation, however, the facts of the matter are of ultimate importance and feelings are not relevant in this context. In each example the situation determines the language style used.

The people within the situation also determine the language used. For example:

One person is speaking to a small child of about 2 years old, another is speaking to a colleague and the third is speaking to an adult who has annoyed them considerably. How do people know?

Clearly, reading the statements above requires some degree of guesswork because it is not possible to hear or see the speaker. Different tones, facial expressions and gestures could change the meanings completely.

Age

Age has an interesting influence on language; people may speak to older people in the same ‘singsong’ style using short encouraging sentences that they would use with children. This can sound patronizing and does not respect the life experience the older person brings to the situation. However, when people are caring for individuals who may not be able to respond on the same level as the carer, the carer may inappropriately resort to language that reinforces a care relationship that the carer can understand. This tendency is neither appropriate nor useful to the client. Caring in a way that is respectful and dignified for older people is a high level skill that requires nurses who are particularly skilled in communication (Box 9.8).

Stefan

Stefan, who is 79 years old and has dementia, lives in a care home. It is nearly lunchtime and Stefan is very agitated about his house keys. Stefan’s carer is keen to take him to the lavatory before lunch. Stefan is frantically searching the drawers in his bedroom. The carer says: ‘Come on Stefan, don’t be silly. The house was sold years ago. You lunch is getting cold. Come on, there’s a good boy.’

Student activities

People with learning and physical disabilities, and mental distress

People with learning and physical disabilities also face similar situations. Again, carers must cope with a complex communication situation and sometimes, rather than adjust their language to suit a person with cognitive difficulties in an age-appropriate way, they resort to speaking to the individual as if the person was a child. These limitations in carers’ communication skills must be addressed, as they disempower the person they are working with.

Such influences on the interaction are based on fundamental differences that include the:

Nurses who work with people with learning disabilities or with children, or nurses who work in more than one language, show skills in ‘convergence’ (see below).They develop skills in talking to each individual in a way that meets their communication and cognitive level.

Another example of this can be found in services for deaf people with mental health problems. Some specialist mental health nurses work with deaf people in services where clients may use British Sign Language (BSL), Sign-Supported English (SSE; a variation of BSL) and speech. Figure 9.4 represents a cline for these languages and language variations and other considerations such as distress.

Nurses move up and down each cline depending on the communication needs of the person with whom they are engaging. By doing this, they match the communication needs of the clients to provide as full access to communication as possible, given the skills and limitations of the nurse and the client. The nurse and the client accommodate to the needs of each other in this fluid situation – remember that clients also have the innate skill to match the needs of the nurse. Typically in settings where more than one language is used, clients do assist nurses and other professionals in understanding their [the client’s] language. This puts the client in an empowered position, thus giving respect to and acknowledgement of their language skills.

In addition to the considerations on the cline, nurses consider issues of gender, social background, education experience, family connections, spirituality and culture. This creates a very complex communication situation where highly skilled communicators are essential.

Accommodating and diverging in communication

People usually accommodate to the communication needs of others quite naturally (Fromkin & Rodman 1997). When travelling abroad with little or no knowledge of the language, people reduce conversation to more simple sentences, use clear pronunciation, and increase the use of gesture to emphasize the point. As already discussed, when talking to small children people adjust language to suit their needs, speaking in simpler terms, using fewer key concepts per sentence, and breaking down communication into chunks that the child can more readily access. When speaking to a person to whom they relate well, people ‘converge’ and start speaking in a similar manner. This is evident by similar use of vocabulary, pronunciation, conversation tempo and often an accent or dialect change to accommodate the other person.

Nurses accommodate to the needs of patients/clients/carers when they explain complex therapies. They speak in non-technical terms and use less jargon to enable the other party to understand. Where the nurse speaks Hindi and Punjabi and the client speaks Gujarat and Punjabi the client and the nurse will accommodate each other by using Punjabi even though it may not be either person’s preferred language.

On occasion, people do not accommodate to the needs of the listener – they ‘diverge’. Divergence often occurs when the:

There are numerous examples of speech divergence in healthcare. For instance, a healthcare professional provides technical information to the patient/client very quickly while moving in the opposite direction, thus disempowering the patient/client. It requires assertiveness and confidence to challenge the speaker, something that people in hospital may lack due to their illness, anxiety or because they may feel in a subordinate position (see Ch. 7).

It is clear that converging often creates an effective communication environment whereas diverging creates difference. However, people can use divergence to assist people to change their level of formality or informality to help them to adjust to the needs of the situation. When people converge too much it can sound patronizing. Where a patient/client is relying on the nurse to make them feel confident in the therapeutic process it is useful to use technical terms and to support the client with an explanation of the meaning of each term.

Interpersonal communication skills

Interpersonal communication can be divided into verbal, signed and non-verbal. This section outlines verbal and non-verbal communication and listening skills. In addition, common courtesy, which is key to all forms of interpersonal communication, is considered.

People represent their world in different ways and have different preferences in the way they access information about their world. People tend to use a visual system, an auditory system or a kinaesthetic system. Some people like to ‘see’ what people are saying, some like to ‘hear’ a good idea and some like to ‘feel’ a sense of what is going on.

When communicating with patients/clients it is useful to be able to use their preferred representational system because this will enable them to access the information with less effort. Initially this may seem rather complicated, but by looking at the words that may suit people it will be easier to understand and practise.

In order to recognize someone’s representational system it is necessary to listen to the words they use to describe their world, perhaps by asking them to talk about something that they have enjoyed, e.g. their favourite place. Listening for the ‘describing’ words the client uses will provide clues about their preference for one or two systems or all three (Table 9.2).

Table 9.2 Representational word systems

| Representational system | Examples of words used | Possible responses |

|---|---|---|

| Visual | ‘I see the idea’ | ‘Does that give you a clearer view of things?’ |

| Auditory | ‘That rings a bell’ | ‘I heard that you wanted to sound out the options’ |

| Kinaesthetic | ‘I have a bad feeling about this drug’ | ‘How would you feel about taking a similar drug?’ |

Common courtesy

That nurses adhere to the norms of common courtesy is the wish of most patients/clients and carers. People tend to identify issues to complain about when they feel others are being rude to them. The number of such complaints is increasing. The signs of courtesy include:

Consideration for others also depicts courtesy. Con-sidering the other person in all dealings with them sounds obvious, but unfortunately people feel that nurses do not always show consideration. This could be not listening to requests, rushing their bathing routine or not considering individual preferences, e.g. in food, cosmetics, clothing, etc. This all shows a lack of consideration for the person.

The signs of common courtesy are clearly identified although they are sometimes difficult to achieve due to the resources allocated, the emotional context in which nurses work and the barriers to communication that must be overcome (see pp. 245–249). However, being able to identify what elements of courtesy people expect as users, consumers and stakeholders in the healthcare system allows nurses to identify their strengths and limitations from which to develop improved skills and sensitivity.

Verbal communication

Spoken words are arbitrary representations of ideas that have been agreed by people who use a language. In other words, they are an agreed sound or group of sounds that we know, representing a thing or an action. Without such agreement on the meaning, the words would be nonsensical or idiosyncratic, understood only by the person who produced them. As such they would not be useful to others though they may hold a great deal of significance for the person who created the sound. Verbal communication usually has written equivalents to the words produced, although some languages do not.

Nurses employ various verbal communication strategies to develop relationships, seek and understand information, provide feedback to others and to demonstrate professional compassion and self-awareness. Some strategies are outlined below. It is useful for nurses to recognize when they use these strategies naturally, before developing their skills further.

Strategies – questioning with good intentions

People use positive intentions when questioning others. This helps them to show courtesy (see above) and respect and this develops trust; therefore they get the correct information in a short space of time with ‘ecology’, i.e. without damaging the relationship environment.

Open questions

Open questions are used to gain information about people, their feelings, their beliefs and values, their perceptions and wishes. Open questions usually begin with a ‘What …? Who …? How …? When …? Where …?’. To help people accept these questions nurses can also use a softener such as ‘It would be good to know how…’. Open questions ‘open up’ the listener’s mind to answers that they can give, information that they hold. Softeners, however, may be so gentle that it becomes a closed question, e.g. ‘Please could you tell me when …’. It is so easy to respond ‘no’ to this very polite request.

Closed questions

Closed questions are used when specific information is needed quickly or if there are other limitations causing barriers, e.g. the client is distressed. Closed questions are those to which the person can answer ‘yes’ or ‘no’, e.g. ‘Do you like soap on your face?’, ‘Are you unhappy?’. It may be the nurse’s intention to gather more information than purely a ‘yes’ or ‘no’. It can be very frustrating trying to get beyond the yes/no responses unless the speaker considers what they are going to ask and what strategy they will use to enhance the information given. Closed questions can be opened by leaving the end of the sentence unfinished, e.g. ‘Are you unhappy … or …?’. This is a useful strategy when the client/child/carer really does not want a lengthy conversation but the nurse needs to open a way for further discussion.

Funnelling

Funnelling is a strategy used firstly to obtain general information then to narrow the information down to an agreement or clear conclusion.

Summarizing

This is a strategy whereby the listener summarizes information given by the speaker. The purpose of summarizing is to check the listener’s understanding at the same time as acknowledging what has been said, thus showing that the listener has heard.

Paraphrasing

This strategy is similar to summarizing but with more use of the listener’s own words. This often helps the listener get the information straight in their own mind.

Clarifying

This enables the listener to present the information back to the speaker then to question if this is what they heard. It is also useful for the speaker to identify with their own thoughts coming from another source; sometimes it sounds or feels different, thus providing another perspective.

Feedback

Feedback provides the listener with acknowledgement of their performance. It can reinforce the behaviour so that it is more likely to happen again and it helps to motivate people through the knowledge that their behaviour was appropriate.

Box 9.9 (see p. 232) provides an example of some of the strategies discussed above.

Verbal communication strategies

Occupational therapist (OT) – ‘Ghedi has been out with the student to the sports centre. He relaxed once he knew that he could choose a time that was set aside for people new to the gym. He said that he was happy to attend about twice a week, so he bought a 6-month off-peak pass. It was really reasonable; I have one they really are worth the money. Anyway he went to his first session, Tai Chi, then back for lunch. He says he feels confident and relaxed and he really does look it too.’

Summarizing

Keyworker – ‘Oh, thanks for that information, so [in summary], he’s got his membership, will be attending at off-peak times, he had his first session of Tai Chi and he is feeling confident and relaxed. Great.’

Paraphrasing

Keyworker – ‘OK, so Ghedi has been out, joined the sports centre, paid for 6 months off-peak and has already started to use the facilities. He’s fine with this and feeling confident’.

Assertive communication

The skill of assertiveness is important to nurses. Assert-iveness enables people to be honest with themselves and in their relationships with others. Assertiveness helps to enhance relationships, avoid power games and is a vehicle for clear outcomes. Hargie (1996) details four elements of assertive communication:

Negotiation and delegation

These are areas that depend on assertive communication. Negotiation is the process where people come together with their own ideas, discuss their ideas and agree on an outcome that is acceptable to both parties. It could be as simple as negotiating a change in the off duty, e.g.

Nurse A asks Nurse B to change a duty on Wednesday because she needs the morning off. Nurse B agrees if Nurse A will do the same for her next Sunday. They agree and the plan is negotiated.

Delegation is another way of getting things done. Delegation often occurs between people of different authority, for example:

Staff Nurse A: ‘Andrew, Ms Wilkinson’s medicines are ready to be picked up. Please could you go over for them?’

Staff Nurse A has delegated the task of collecting the prescription from pharmacy to Andrew, a first year student nurse. When delegating to another person it is imperative to be polite, assertive and clear. Offering information to support the request allows the other person to understand why they are being asked to perform a task. Delegation is reliant on a number of issues:

Non-verbal communication

Non-verbal communication is that part of communication that is not reliant on words. As approximately 60% of communication is non-verbal, non-verbal skills are essential for effective communication. It is clear that people determine a great deal of meaning from aspects of communication other than words. People who are blind or partially sighted generally place more emphasis on the intonation of a person’s voice to pick up the non-verbal messages (see Ch. 16). Argyle (1994) suggested that non-verbal communication was made up of:

This chapter focuses on gesture, touch, proxemics and posture. Paralinguistic issues, i.e. the voiced aspects of non-verbal behaviour, for instance guggles, are discussed later (see pp. 235, 238).

Gesture

Gesture is a crucial aspect of non-verbal communication. Some psychologists and linguists suggest that early humans used gesture before they used spoken or signed language (Armstrong et al 1996). Gestures can be classified into categories of increasing complexity.

Universal gestures that are understand by most people include opening arms and eyes wide to suggest bigness; furrowed brows, pursed lips, drawing body inwards and moving index fingers together would suggest smallness. Subtler gestures include a cupped hand to the mouth to indicate a drink, or a single upwards gesture of the hand with palm facing upwards suggests that someone stand up.

Certain gestures are recognized as specific to a language community, such as the ‘OK’ gesture with thumb and index finger touching to make a circle with the other fingers raised. However, it is important to be aware that some gestures that are acceptable in one community are possibly offensive in another. For example, the ‘OK’ gesture is offensive in Brazil. Each language community shares an understanding of its own group of gestures.

Touch

This is a complex and intricate communication subject and often difficult to tackle. Children tend to be touched more than adults. Interestingly, babies and young children who are not touched do not thrive as well as those who are (Hargie 1996).

Touch for many people is an essential aspect of their working lives. Nurses in particular must learn how to touch people in a professional context without causing embarrassment or concern to the patient/client. In addition, nurses must ensure their own safety. Nurses use two clear types of touch: first and often the most intimate type is the necessary touch nurses use when attending to people’s physical needs and during other nursing interventions; the second type is the touch that communicates a feeling or a meaning, such as, ‘I am here to care for you’ or ‘It will feel better soon’. Everyone has a very personal view about touch, when it is appropriate and when not. People from different cultures will touch each other according to their accepted norms.

It is suggested that a well-timed touch on the shoulder or hand can help a person in distress to feel comforted, or feel the care of another person, which creates a sense of trust. Touch in this scenario is thought to encouragekthe person’s cathartic release by communicating that you are right with them in the moment, close to them and sharing their feelings. This affirms their sense of self; it respects their distress and shows the nurse’s commitment to their needs.

There is also a view that touch can block an emotional release. The use of touch when someone is crying, for example, is a means to stop them crying rather than conveying the message that crying is fine and to be encouraged. If this were the case the nurse would be communicating a need to control the patient’s/client’s emotions for the nurse’s benefit, rather than it being a positive patient/client-centred intervention.

Touch is more appropriate in some clinical settings than in others. Understanding what is acceptable in each area is important and nurses can learn much from each other (Box 9.10). As a student new to a client group it is useful to know how people deal with the patients’/clients’ emotions. Also crucial is an understanding of common courtesy (see pp. 230–231) and the social norms of the patients/clients and carers who are most likely to attend the clinical setting. Nurses need to be able to consider this information while at the same time working with the emotional needs of the people in their care (Varcarolis 1998).

Appropriate touch – learning from others

Nurses who are consciously competent in respecting a client’s dignity will more readily engage their trust, and therefore be more likely to be able to work therapeutically and less likely to cause offence. Think about occasions when you worked with registered nurses who perform the most intimate of procedures while maintaining the dignity of the patient/client.

It is vital that nurses also recognize their own feelings around touch (Box 9.11).

Proxemics

Proxemics is a fascinating area of communication because people have very different views about their own personal space; how close people like to be to others and how close they like others to be to them can be very complex and bound by personal rules.

Boundaries enable people to feel comfortable in their environment. Some boundaries are fixed, such as walls and rooms within buildings; others are semi-fixed, such as the seating in the health centre or seating arrangements in a dining room and the location of the television. These arrangements are an indication of where to sit, where to eat and which way to face. Fixed and semi-fixed boundaries can help or hinder communication between people.

The other type of boundary is the informal space between people. This space is fluid and is utilized in different ways for different messages and in different settings.

The person listening will be aware of the distance between themselves and the speaker and vice versa. There are clear cultural differences in the distance people accept between each other.

Knowingly intruding into someone’s personal space can be very intimidating for the listener. This approach is used to interrogate or bully people, resulting in their disempowerment. It may be necessary to gently remind colleagues or children or clients that their comfort zone may be smaller than that of other people. Some people are so at ease with another person that they may use them as a ‘human prop’ when recounting a story. To re-enact a story they may talk to the listener and relate to them physically as if they were there at the time to show the listener the gravity of the situation, the humour or the distress. Some people are happy to be human props but others find it disconcerting and embarrassing because it focuses attention directly on them.

Posture

How a person holds their body in relation to other people and in relation to the fixed and semi-fixed boundaries communicates a great deal about what they are feeling and thinking. Posture sends a very clear message; for example, leaning forward indicates interest and respect for the other person. On the other hand, despite looking at the other person, a lack of interest is portrayed if the listener’s body is orientated towards the door, and sitting back in the chair with feet turned towards the door suggests they would rather be somewhere else.

How a person filters the information provided by the external event will affect their thoughts, feelings and behaviours; therefore their posture is a mirror of their inner beliefs (see p. 235).

When a nurse wants to create a sense of confidence they walk into the situation with their head held high, at a moderate pace, and do not slouch because they recognize that this would convey a message that is unsuitable.

People will look at the nurse’s posture and decide very quickly whether they like them or not and whether they can be trusted or not. Where clients have poor short-term memory and have difficulty remembering people’s faces, names or roles it is imperative to use posture that is confident and respectful because the client has to make continual assessments of people to see if they ought to trust them or not.

Once people have made a judgement it is difficult to convince them otherwise. This may seem a little harsh but it is a survival technique that has helped people to function in social settings for thousands of years.

Listening skills

How do people know that they are really listening to someone, or that someone is really listening to them? Many nurses claim to be good listeners, because in the clinical environment to suggest otherwise is almost as bad as saying they are poor nurses.

People often know when someone is not listening to them; they feel ignored, undervalued, frustrated and disempowered. Not listening to the other person can seriously affect the relationship. In a nurse–patient/client relationship the outcome of not listening to a client can result in their choices being reduced, e.g. not eating their choice of food, the nurse not understanding their fears and anxieties, the potential for misdiagnosis and ultimately ineffective or even harmful treatment. If nurses fail to listen to colleagues, not only is vital information missed but it can also affect the colleagues’ motivation, trust, self-esteem and skills.

There are a number of reasons for listening and different types of listening skills are needed. Wolvin and Coakley (1985) identified four types of listening:

Characteristics of good listening

Good listening skills are vital to rapport and empathy, which are discussed later (see pp. 237–238). The following characteristics of good listening are based on English speaking Western cultural norms. People from different linguistic and cultural groups have different norms of communicative behaviour (see pp. 247–248).

Appropriate eye contact

Appropriate eye contact is where the person listening looks at the person who is speaking. They blink just after the speaker blinks or when they are ending a sentence. The listener’s blink rate matches that of the speaker and corresponds with their head nods of encouragement. The eye gaze is generally soft, slightly heavy lidded as opposed to staring and hard (eyes slightly wider than usual denotes some muscular tension). However, the listener’s gaze also mirrors the verbal and non-verbal expressions of the speaker.

Mirroring

When engaged in listening, people naturally find themselves ‘mirroring’ the speaker’s posture. This does not mean copying their every movement as if playing a game; instead the listener may be leaning slightly in the same direction, tapping their pen at the same time the speaker is tapping their foot, folding one arm across the body as the speaker folds both arms (Box 9.12).

This behaviour is a natural sign for the speaker that the listener is with them, acknowledging their mood, recognizing their feelings and trying to understand them. This behaviour increases rapport between the speaker and listener and encourages the process to continue.

Nurses and other healthcare professionals often need to develop trust and rapport quickly in order to work effectively with people. Being aware of their skills in mirroring another person is vital in enhancing the therapeutic or professional relationship (see pp. 236–245).

Guggles

Guggles are the sounds (non-words) uttered when listening, e.g. ‘mmmms’, ‘ahs’, hmm’. These affirm the speaker’s point, agree with them and confirm their view or idea. To do this, guggles rely heavily on intonation and tunes (see p. 248). The use of guggles by the listener encourages the speaker to continue by providing evidence that the listener is listening (Box 9.13).

Skills that encourage and discourage conversation

Next time you are listening to a friend telling you a story (one that is not too sensitive), listen to your own guggles.

Student activities

Active listening

Nurses and others often highlight active listening as an essential skill, as the term implies a requirement forenergy and concentration on the part of the nurse. The aim is to enhance the quality of the therapeutic relationship and to facilitate problem-solving by being with the speaker on a social, psychological and emotional level (Egan 1998). In active listening, the listener:

Nursing relationships

The first half of this chapter has provided the knowledge and encouragement needed to develop skills in a variety of components that create a good communicator. This section draws upon this learning for enhancing communication in a variety of relationships with different outcomes.

The types of relationship that people connect with on a day-to-day basis are intimate, social, professional and therapeutic. In this section the focus is on the thera-peutic and professional relationships that nurses experience and how these relate to care and health outcomes.

Therapeutic relationships

Nurses have therapeutic relationships with the patients/clients/children, families and carers they work with. The therapies they offer cover a wide range of interven-tions from an adult nurse providing education about insulin therapy to mental health nurses providing cognitive behavioural therapy. Interventions also include assisting people and children with the activities, e.g. eating and drinking, in ways that maintain the individual’s independence, dignity and health. An essential component that underpins all nursing interventions, from daily living needs to sophisticated procedures, is the ‘therapeutic relationship’ (Box 9.14).

This relationship is the foundation on which the nurse and patient/client can work together to identify issues that are affecting the patient/client and that require change. The therapeutic relationship facilitates the patient/client to move from their current state of ill health, distress or need to their desired state of maximum attainable health, well-being and strength. Where patients/clients are unlikely to achieve full health, the therapeutic relationship is used to assist reconciliation, alleviate stress and provide solace and support.

The therapeutic relationship relies on specific components being in place, including rapport, empathy, trust, genuineness, warmth and positive regard (see pp. 237–239). The therapeutic relationship requires the nurse to have active listening skills and proficient interpersonal skills (see pp. 234–235). It is also vital for the practitioner to know their own values and beliefs and how these can produce filters that may affect their resourcefulness.

Skills that develop ‘connectedness’, the emotional connection between two people, are great; however, thenurse also needs to develop a range of communication strategies. This may sound quite manipulative and in the wrong hands good communication skills can be devastating if the aim of the strategy is to gain at the expense of another person. An excellent example of good communication skills in the wrong hands is the stereotypical ‘cold-calling sales person’. When developing relationships and communication strategies it is necessary to reflect on the desired outcome and decide whether it is ethically and morally correct.

Attributes of a nurse–patient/client relationship

Not all nurse–patient/client relationships are the in-depth type utilized by nurses who work in learning disability or mental health settings. The focus of nursing relationships is to bring about change in a person’s health or facilitate an optimum quality of life. Sometimes this is about empowering the person to do this independently; on other occasions the nurse will be undertaking a nursing intervention for a client. There are some attributes common to all nurse–patient/client relationships that are also witnessed in nurse–family/carer relationships.

Being there

O’Brien (2000) suggests that patients/clients like the nurse to ‘be there’ for them. This appears a simple task but it is an intense and emotionally powerful task to do for someone. Being there is being present for the patient/client when needed. This need will sometimes leave the nurse feeling exhausted because they have given so much emotionally (see Ch. 11) and may occur while the nurse is supporting the patient/client in and through their distress.

Self-disclosure

O’Brien (2000) also found that, in developing and sustaining a nurse–patient/client relationship, the nurse needed to give the client some information about him/herself. This was to show humanity and put the two people on an equal footing. The more people share with another person, the closer they can feel to them, thus increasing rapport.

Patients/clients sometimes think that they are the only ones who are having difficulties; by some self-disclosure the patient/client is able to see that others share their difficulties. This also validates their feelings and provides perspective for the problem.

It is also easy to disclose too much information, particularly when nurses have developed a good rapport with the patient/client or carer. Having good rapport (see pp. 237–238) enables nurses to feel comfortable with the other person and to discuss things not usually discussed. This can be damaging to the nurse and to the patient/client if the information shared can be used to make the other person feel vulnerable in any way.

Being concerned

Being concerned enhances the nurse–patient/client relationship (O’Brien 2000). Nurses develop a protective feeling towards the people they work with while at the same time recognizing the need for the patient/client to make their own decisions about their lives and their health. Nurses were clear that their role was to offer choice and alternatives to facilitate the patient/client in problem-solving.

Trust

Trusting another person is sometimes hard and at other times easy. Some people automatically trust medical professionals because they believe they are in a position of expert knowledge and power, and are caring. In trusting someone, people tend to expect certain behaviours. For example, they want the person to be:

Trust is hard to win and very easy to lose, and regaining lost trust is very difficult. Losing trust is best avoided by giving time, energy, concern and regard to everyone involved.

Being ‘as if’

It would be naïve to assume that nurses will never be challenged by wanting to ignore the person, to snap at a patient/client or child who appears overly demanding, to wish that the patient’s/client’s family would realize that the nurse has other people to look after, or that they feel like crying too. At the most challenging times nurses who manage to maintain their professionalism tend to use clear strategies for dealing with the situation. Some strategies to maintain a professional profile include:

Whatever the strategy chosen, it is important to remain outwardly congruent (outward behaviour should be true to the situation) or others may construe that the nurse does not care.

Empathy

Empathy is when a person puts themselves in the other person’s position, attempting to understand the world as they see it. Empathy is an emotional response to another person’s situation; people often describe feeling a physical sensation in their abdomen or chest when they see someone in a bad emotional or physical state.

It is not uncommon for people to want to laugh if they see or hear others laughing, yawn when they see others yawning and cry when others are upset. They are ‘wired’ to echo the movements and the expressed emotions of others. By doing this people feel the same physical feeling, have thoughts that relate to the feeling and behave in ways that relate to the thoughts and feelings. People can influence others with their happy mood or bad temper. Emotions are ‘catching’ because people have a tendency to automatically empathize. Other people’s movements also influence people, e.g. by making chewing movements while feeding a child or nodding at a conversation on television.

For some people empathizing does not come easily. These people are naturally self-orientated. This does not mean they are self-centred, it means they are more internally focused. People with autism and Asperger’s syndrome have challenges in empathizing because they have a limited ‘theory of mind’. This constrains their ability to understand that they and other people have thoughts, feelings and behaviours, which results in serious limitations in their social and communicative competence.

Another result is the chaos that people with autism feel with regard to other people’s behaviour that can look random and bewildering to them. Some people with autism will go through life without social connections or needing to be with others, preferring the calm of their own world, routines and structures. Other individuals can be aware that there is a difference in the way they relate to others. This realization of poor psychological connectedness can be challenging and confusing and can result in an increased sense of difference for the individual.

Children with autism show this lack of psychological connectedness with those around them and also in their play; they do not role-play because they cannot attribute behaviours, thought and feelings to the toys. The inability to imitate others such as playing ‘mum’ or ‘teacher’ stifles the child’s development in attributing roles to people, standing in other people’s shoes and seeing the world through their eyes, i.e. empathizing (Box 9.15, see p. 238).

Toby

7-year-old Toby has autism. He is extremely distressed, having fallen and hit his head. Toby needs to attend the Emergency Department, but his mother, who is also very upset, feels that there is no possibility of Toby cooperating with a visit to hospital. Toby is clinging desperately to his red lorry, looking straight ahead and avoiding contact with his mum.

Rapport

Rapport is the connection between two people, where they talk on the same ‘wavelength’, share the same humour and share in each other’s pain and sorrow. Couples, family members and lifelong friends often hold deep rapport.

Rapport plays a significant part in developing a therapeutic relationship but this does not mean that without rapport nurses cannot facilitate change in people’s health. However, rapport promotes productive relationships and thereby better outcomes for all.

Table 9.3(see p. 238) outlines the different levels of rapport.

| Level of rapport | Description | Who |

|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | No rapport | Strangers who have just met. They neither need to know each other nor want to |

| The beginnings of a connection | People who have spent a little time together and are exploring common ground | |

| Level 2 | A connection creating good communication | People are making the effort to understand each other socially, professionally |

| Finding out about each other and using interpersonal skills to express ideas, needs, to investigate and gather evidence either on a social or professional level; this might be from meeting someone for the first time and realizing you both enjoy the same music | ||

| Sales people may have excellent communication skills and are adept at creating rapport at speed because that is when you are most likely to purchase their product | ||

| You could be working with a family who are being educated regarding the health of their child who has a long-term illness | ||

| Good connection, good communication, mutual feelings of relating well | The people involved are actively listening to each other, good eye contact, personal space is within 3 metres | |

| Level 3 | Excellent connection, relaxed, easy communication, parties sense a physical closeness | People involved feel the other person really knows them, feels they can share everything, almost as if the other person automatically knows what they are thinking |

| They can pre-empt the other person’s next move |

The third level is often associated with being deeply attached to someone. Although most people have the opportunity to feel this depth of closeness during their lives, others are less fortunate. This level of rapport is not appropriate for a nurse to share with a patient/ client or carer. Feeling this close to someone negates any possibility of a professional therapeutic relationship, as the nurse would not be a resource for the patient/client/child or carer. Nurses who share this level of rapport with people they work for can experience immense stress, destroy professional trust and can seriously affect the health of the patient/client (see ‘Boundaries are healthy’, pp. 240–241).

A working level of rapport gives power to each person in the relationship; it gives the nurse room to provide the correct care within the limitations of their role and responsibilities and encourages them to refer to another person when necessary. The professional alliance that isformed respects the participants for the skills and knowledge they bring to the situation. Importantly, people remain independent of each other; they do not merge into one entity.

Rapport is easier between individuals who share similar life experiences, values, belief systems and language. This is because trust comes easier in these situations. In developing rapport and empathy with patients/clients and carers it is important to realize that people relate to each other on very different levels and to different degrees depending on their circumstances and their ability to comprehend others. Some people have difficulty in understanding how to relate to other people in a healthy way. These difficulties in relating to others may be due to anxiety, anger, confusion or poor relational skills.

Facilitating change

In the therapeutic relationship nurses are trusted to assist change in patients/clients and carers by facilitating the understanding of information. They are also entrusted with the task of helping a person involved in this health process to move from the current state A to the desired state B (Fig. 9.5).

Essential communication and interpersonal skills underpin facilitation. Box 9.16 considers the nurse–patient/client relationship in different settings. A patient/client is unable to move from A to B if they cannot relate to the nurse, i.e. if rapport, trust, the nurse’s concern and the nurse’s skills in ‘being there’ for the client are not evident. Nor will they move from A to B if the nurse does not have the communication strategies to be a resourceful facilitator.

Nurse–patient/client relationship and care delivery

It is clear that all the scenarios provide different levels of contact between nurse and patient/client/carer, all of which require different levels of relationship building. No one way fits all and nurses have to accept that while they continue to value good interpersonal communication skills and strategies, not all nurse–patient/client/carer relationships need to be in-depth to be resourceful but it is vital that some are.

Positive regard

Positive regard is the ability to hold and convey feelings for other people that are not based on negative beliefs about the person. Having positive regard for patients/clients, carers, parents and colleagues enables the nurse to approach others with positive intentions towards them. Maintaining positive regard for people can help nurses manage their thoughts, feelings and behaviours even insituations where the other person may be behaving in a way that is not appropriate.

Attachment

People learn how to relate to others from the attachments they develop as children (see Ch. 8). These attachments focus on principal caregivers and result in the ability to relate to themselves and to others. Where they have strong, nurturing, encouraging and fulfilling relationships with others they are confident in their skills and developing abilities, which is expressed through their mental well-being. Environments without emotional sustenance, encouragement, love or stability can result in people having emotional problems and an impoverished sense of mental well-being, thus creating people who experience vulnerability and dysfunctional relationships.

Nurses meet people who are in extreme situations – people who are frightened, ill, angry and anxious, whose ability to deal with their current crisis is based on their mental and physical well-being, which by the very fact that they are seeing a nurse could be compromised. Therefore it is reasonable to suggest that nurses work with people who have difficulty with relationships, whether this is situational and transient or long-term and embedded in the thoughts, feelings and behaviours of the individual.

Not all nurses have high levels of mental well-being nor have they experienced positive nurturing upbringings in secure and loving environments as this is clearly not plausible, nor should it be a prerequisite for the profession. What is important is that nurses understand themselves and the positive and negative experiences that contribute to their current ability to relate to others, to develop insight and to be resourceful for the people they work for and with (Box 9.17).

Mapping relationships

Consider for a moment your own ability to relate to others.

Student activities

On a piece of paper, draw yourself in the centre and add your current social network. This may include family members, friends, colleagues and pets. Consider each person individually:

Now draw another map of your social network from 5 years ago and repeat the questions. Are you surprised at any differences? How do feel about the way your network has developed? Is there anything you would change? If so, how would you go about changing things and why?

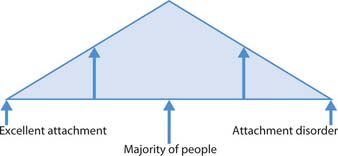

Some children have families that are highly nurturing and safe, with the potential to be resilient to emotional challenges. Most people have families that experience the ups and downs of emotions, love, loss and nurturing with some resilience to these challenges. A few people with little innate resilience to emotional challenges experience the most challenging of environments and these people may develop attachment disorders. It is clear that whether it is an issue of physical illness, developmental need or mental well-being, nurses can be involved with people at all stages on this attachment continuum (Fig. 9.6). Mental health nurses will be more involved with people with attachment problems and emotional distress, depression and behavioural disturbances because of the clear link between these issues and challenges to mental health.

Nurses provide care for others, i.e. they are caregivers. This is a very powerful position to be in because of the responsibility given to the nurse while the patient is in need. For people who have experienced good attachment there is little to do other than reinforce their sense of emotional well-being through being there for them, being concerned for their care and health outcomes, and being skilled in the delivery of that care. For people who have experienced more negative attachments and who do not express a sense of well-being, nurses must realize that their actions can have considerable impact on the patient/client and carer as they take on the role of caregiver. Nurses need to develop skills in areas that include:

The points above are a guide to skills that are useful in providing services for all and particularly for people with more complex relationship needs. With this in mind, consider the nurse who feels special because they are the only person who can work with or care for a patient/client, or who a patient/client wants near them. This nurse should reflect on their own need to feel needed, to feel special and how the patient/client may be fulfilling these needs and why this may lead to an unhelpful service for the patient/client. Student nurses are often able to spend more time with patients/clients and carers and so can find that they develop strong attachments. Hopefully, with the issues raised above, nurses will be able to develop their resourcefulness further, thus protecting themselves and the people they work with from emotional stress or harm.

Boundaries are healthy

Boundaries are useful and positive rules that enhance resourceful relationships to improve health outcomes. Some nurses find the correct level of boundary between themselves and patients/clients easy to judge, whereas others find it more challenging and many nurses can remember experiences where they ‘got it wrong’.

Boundaries begin to develop as soon as the nurse meets the patient/client or carer and explains their role and responsibilities. A clear and concise explanation gives information about what the nurse does, thus enabling the patient/client or carer to begin to develop a picture of why each healthcare professional is involved and, crucially, how they, the patient/client or carer will be involved in the process.

On one level the public needs to know the roles, responsibilities and level of involvement they can expect from healthcare practitioners, as outlined above. At a deeper level nurses are enhancing the ability to be in a resourceful position for the people they work with. Boundaries enable nurses to maintain a professional commitment to the public; nurses are resources who offer healthcare, expertise and skills to facilitate change in ways that would be difficult if they became ‘friends’ with the people they work with. Professional and therapeutic boundaries are safety nets for the protection of everyone involved.

Boundaries also provide clarity for professionals. People working in healthcare often find themselves working across professional boundaries; nurses may overlap with occupational therapists (OTs) or social workers in the same way as they may overlap with traditional nursing roles. For example, supporting people in their own homes with developing independence skills could be facilitated by a nurse, an OT or a social worker, particularly when they work in multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) such as assertive outreach teams or home treatment teams in community mental health services (see Ch. 3).

These teams function with clear communication systems and full understanding of each member’s roles and responsibilities, skills, specific training and the therapeutic relationships they have with the patients/clients. Of primary importance to such teams is the consistent engagement of difficult-to-engage clients rather than individual professionals being territorial about their traditional roles. The client is paramount; the clinician’s skills support the patient/client and each other through enhanced teamwork and communication.

Boundaries sometimes go wrong by being unclear, breached, ignored, too stringent or, more seriously, abused. Unclear boundaries do not provide the supportive structure needed for clinicians to deliver the service required. Moreover, lack of clarity disempowers the patient/client and carer because they do not have the information required to be fully involved in their care. Unclear boundaries can lead to breaches of professional conduct (see Ch. 7), including over-involvement or abuse by either the care provider or the person receiving care.

Professionals who are unclear about each other’s roles create confusion, which can lead to breakdown in communication and service delivery. This means that patients/clients and carers suffer. Unclear professional boundaries can lead to missing information, which can have extremely serious consequences such as role confusion, misdiagnosis, incomplete risk assessments or poor care and health outcomes.