Chapter 23 Pain management – minimizing the pain experience

Introduction

Pain is a common experience throughout life and often it was seen as a burden to be endured because little treatment was available. It may be argued that people start life with acute pain following birth, though this may only recently have been acknowledged. As people age, degenerative disorders of the musculoskeletal system often lead them to accept pain as a natural consequence of the ageing process. This acceptance can limit quality of life, an important issue in the ageing population. Over the past 50 years advances in pain management have been possible due to an improved understanding of the multidimensional nature of pain and subsequent advances in treatments available.

Pain is recognized as a useful indicator of tissue damage and, from childhood, pain ‘hurt’ is associated with injury. The pain experience is not just a sensory signal; pain triggers complex physiological, emotional and social responses. These are influenced by many factors that include pain type, age, past experiences, emotional state, environment, culture and cognitive appraisal.

Although pain is often a useful warning of tissue injury that allows people to respond to external harm or internal changes, it may also cause physiological stress and emotional distress, which can harm the individual if unrelieved. Indeed some diseases, e.g. cancer, are not associated with pain as a presenting feature though it is commonly associated and feared in advanced disease. Even trauma may not initially be associated with pain at the time of injury; often a sports injury is not recognized until the game is over unless it is serious.

Poor pain management can lead to physical and emotional problems; postoperatively it is linked to complications and delayed recovery. In children, pain may lead to regression; a poor experience can have serious implications for future contact with healthcare personnel and settings in adult life.

Nurses are frequently key workers in the management of pain. Pain recognition and prioritization are important aspects of patient care. Pain is a common experience across all care settings, both hospital and community based. An elementary understanding of pain and its management is relevant to foundation studies and central to all branches of nursing.

The nature of pain

This part of the chapter outlines the different types of pain, gate control theory, pain physiology and psychological and cultural aspects of pain.

Pain is a subjective, complex and multidimensional experience that has physical, psychosocial, emotional and spiritual elements. Due to its complexity, a simple agreed definition for pain is elusive. The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) (Merskey & Bogduk 1994) defines pain as ‘an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage’. In 1968, McCaffery proposed a simple statement which is widely accepted in nursing as it emphasizes the individual nature of pain and the patient is clearly identified as the key person in pain assessment – ‘Pain is: whatever the experiencing person says it is, existing whenever he says it does’ (McCaffery & Pasero 1999).

Types and characteristics of pain

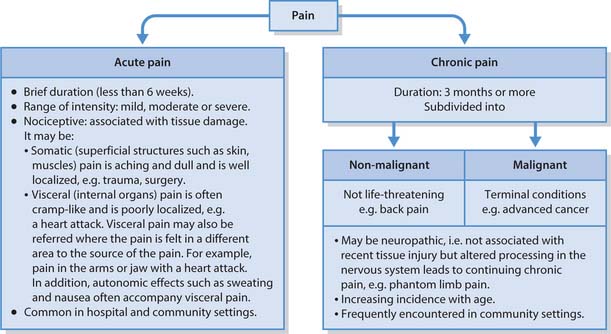

Clear distinctions between types may not be possible (McCaffery & Pasero 1999). However, general categories can help to identify suitable evidence on which to base care. One of the broadest categories is acute or chronic, which classifies pain according to a timescale (Fig. 23.1). This chapter will concentrate on acute and chronic pain; however, pain can be categorized in other ways that include:

In order to provide appropriate care, nurses need to appreciate the type of pain experienced as this influences assessment and suitability of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions.

Acute pain (Fig. 23.1)

Acute pain is usually of brief duration (less than 6 weeks) and is commonly nociceptive, associated with tissue injury such as surgery, which subsides as healing takes place (Box 23.1). Acute pain is very common; it can range in intensity from transitory pain felt after a minor bump or a mild headache to severe pain associated with trauma or disease, e.g. fractures or heart attack. Mild acute pain may be managed successfully with patient/parent-initiated interventions at home. However, the pain may also indicate problems and motivate the person to seek medical advice.

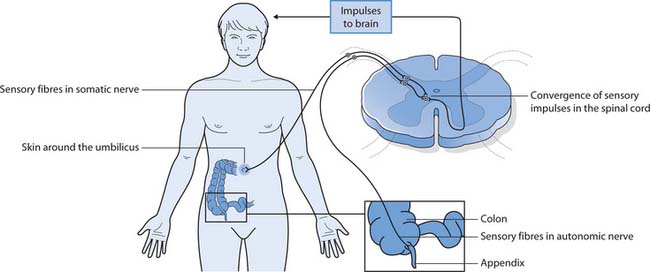

Acute nociceptive pain may be referred; this is when pain arises in internal organs (viscera) but is experienced some distance from the source of the pain. For example, a heart attack frequently causes pain down the arms (usually the left) and up the neck and jaw, despite there being no tissue injury in those areas. Sensory impulses from the left arm and heart enter the spinal cord at the same level. Normally, few sensory impulses are processed from the heart so when more impulses are received for processing, this results in perception of pain arising from the arm. Another example of referred pain is the initial pain of acute appendicitis, which is felt around the umbilicus, despite the appendix being sited in the right lower part of the abdomen (Fig. 23.2).

Chronic pain (Fig. 23.1)

When pain does not resolve and becomes chronic (usually lasting longer than 3 months) the effect on a person’s quality of life can lead to depression and social isolation. In a child this may seriously influence their education and their future potential as adults. In adults it can cause relationship problems, isolation and financial difficulties and it may be a cause of mental health problems including suicidal ideation. Chronic pain is further subdivided into non-malignant and malignant (life-threatening) pain.

Chronic non-malignant pain

Chronic non-malignant pain is not life threatening and may be due to continuing tissue injury, e.g. rheumatoid arthritis, where the degeneration may continue for the rest of a person’s life. The two most common reasons for this type of pain were identified as back pain in all age groups and arthritis, which increased proportionally with age (Elliot et al 1999). This research estimates that 46.5% of the general population suffers chronic pain, though for many this was mild pain (Elliot et al 1999). This has implications for support required by this group in the community. However, when back pain first occurs it could be considered as acute, its failure to subside can then lead it to become chronic. Effective management of acute back pain may reduce the risk of people developing chronic back pain. Horn and Munafo (1997) discuss pain dimensions and propose that acute and chronic pain may be usefully regarded as at the ends of a spectrum, rather than fundamentally separate conditions.

Chronic non-malignant pain can involve alterations in pain processing by the nervous system, which results in pain memories. This is known as neuropathic pain, e.g. phantom limb pain where pain is perceived as coming from the amputated part, or the nerve pain (neuralgia) after shingles (Box 23.2). Neuropathic pain may exist without any identifiable tissue damage.

Box 23.2 Neuropathic pain after shingles

The acute pain of shingles (herpes zoster) can also lead to chronic pain known as postherpetic neuralgia if the pain is not well managed. The chronic continuing pain becomes typical of neuralgia with:

This can have serious effects on quality of life, affecting sleep, normal mobility and social interaction, particularly a concern in older people. The aggressive management of the acute pain with appropriate drugs reduces the risk of postherpetic neuralgia developing.

It is suggested that the initial tissue or nerve damage can lead to persistent changes in the central nervous system (CNS). It is then argued that failure to effectively manage acute pain can lead to an increased sensitivity known as ‘wind-up’ in the CNS, which can be respon-sible for chronic pain (Carr & Mann 2000). Evidence supports this in the example of phantom limb pain, where the incidence is greater in patients who had pain prior to amputation, and incidence of neuropathic pain that has been reduced with the use of effective preoperative pain management (McCaffery & Pasero 1999).

Neuropathic pain is difficult to treat and can be particularly baffling for patients and carers as it does not follow the more familiar acute pain pattern and may continue for many years. In the past the person was often referred to mental health professionals, particularly if an organic cause (tissue injury) could not be identified. It is now recognized that all pain involves psychological and physiological factors, and that the role of psycho-logical factors increases when the condition is long lasting (Sarafino 2002).

All pain experiences may be modified by psycho-logical factors so treatment and management should incorporate this knowledge for both acute and chronic pain. Chronic pain can impact on the following:

This can be destructive to normal quality of life for the individual and their carers, and management should focus on all these areas to provide holistic care. For these people, pain management often involves more specialized pharmacological approaches. Many people with chronic pain are in the community and may require support from the primary care team (see Ch. 3) with referral to specialist multidisciplinary teams (MDT) (see p. 668) to achieve the best in pain management.

Chronic malignant pain

Chronic malignant pain is associated with terminal conditions, often linked to cancer, where the progression and spread of the disease lead to pain. However, pain is rarely a presenting symptom of cancer. Initially the ‘cancer journey’ involves acute pain (nociceptive) associated with diagnostic procedures and treatments, e.g. surgery. If the cancer spreads, pain can then become chronic and more complex, involving nociceptive, neuropathic and psychological components that require regular review and adjustment of treatment to meet the person’s needs (see Ch. 12). This is recognized as ‘total pain’ and requires skills across the MDT (Paz & Seymour 2004). The patient with cancer pain can also suffer acute pain episodes, e.g. pain following a pathological fracture.

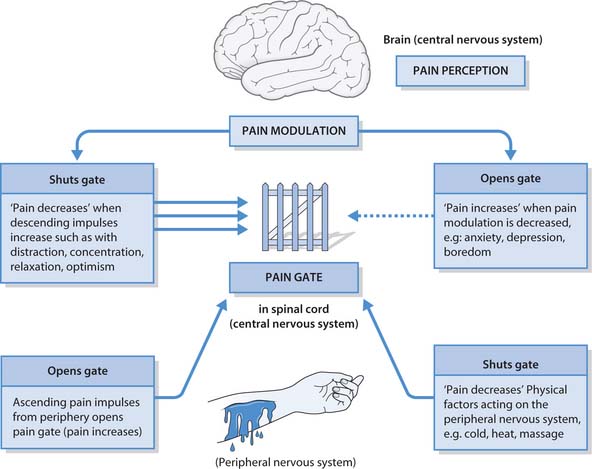

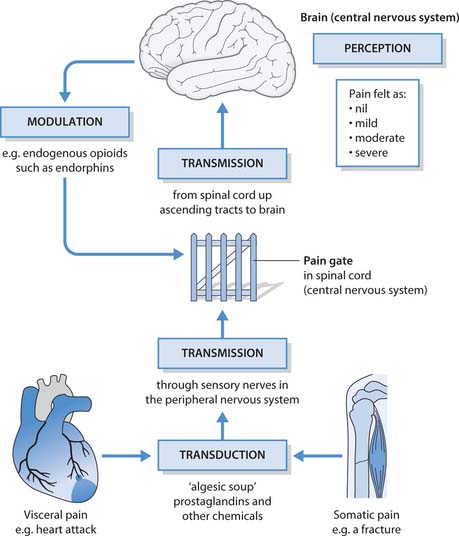

Gate control theory

In 1965, Melzack and Wall devised the gate control theory which proposed that the pain sensation is modulated (processed) in the spinal cord by a gate-like mechanism. The gate theory proposed that active processing of nerve impulses occurs in the spinal cord where the pain sensation first enters the CNS. The proposed ‘gates’ are thought to be in a region of the spinal cord known as the dorsal horn. The gate is opened or closed depending on the combination of sensory ascending impulses from the periphery or descending impulses from the brain. Pain will only be appreciated if the gate is open. This recognized the psychological influences on pain such as anxiety and proved a sound theory on which to explain clinical observations of pain perception. The theory is proving to be robust and has been refined by further research. The subsequent discovery of endogenous opioids, e.g. endorphins, in the 1970s enabled the actual mechanism of modulation to be understood in more detail. The gate control theory is acknowledged as providing a good theoretical basis for understanding pain perception in individuals as it recognizes factors that open or close the gate and guides approaches taken to managing pain (Fig. 23.3).

The theory recognizes the multidimensional nature of pain and explains the many aspects of pain that are known to influence pain perception and can be used in pain management. As psychological (emotional) and cognitive (evaluative) aspects appear to influence the opening and closing of the ‘pain gate’, it encourages nurses to take a holistic approach to pain management, which acknowledges these components. This supports the unique nature of a person’s pain experience; even when pain physiology appears to be closely matched, the emotional state and cognitive appraisal (past experience and meaning) of the experience can result in different pain perception by individuals. Table 23.1 summarizes the factors known to influence the ‘pain gate’. Some examples of the influences on a person’s perception of pain are provided in Box 23.3 and the effects of chronic pain in Box 23.4.

Table 23.1 Factors known to in. uence the ‘pain gate’ (summarized from Sara. no 2002, p. 347)

| Conditions | Conditions which may open the gate ‘Make the pain worse’ | Conditions which may close |

|---|---|---|

| Physical | Extent of injury | Medication |

| Inappropriate activity levels | Heat, cold, massage, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) | |

| Fatigue | Exercise including sexual intercourse | |

| Emotional | Anxiety | Positive emotions (happiness or optimism) |

| Depression | Relaxation, rest | |

| Mental | Boredom | Intense concentration |

| Focusing on pain | Distraction |

Influences on pain perception

Pain is influenced by a number of factors such as knowing the cause or not. Read the statements below and then carry out the activities.

Physiology of pain

The experience of pain results from integrated processes involving chemicals, sensory receptors, nerve fibres, spinal cord with the ‘pain gates’ and various areas in the brain. Knowledge of pain physiology enables the nurse to understand how pain can be relieved and how analgesics (drugs that relieve pain) act. Acute (nociceptive) pain is described as involving four processes:

The four processes are outlined and shown diagrammatically in Figure 23.4 (p. 658).

Transduction

Injury causes the release of inflammatory chemicals such as prostaglandins and 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) that form an ‘algesic soup’ (meaning pain causing). These chemicals stimulate nociceptors (receptors that respond to stimuli that are harmful and cause pain) on sensory nerves, which transmit impulses from somatic areas (skin, joints, bone) and the viscera (internal organs). Prostaglandins are among the key chemicals released by damaged tissues. Drugs collectively known as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) relieve pain by inhibiting prostaglandin production.

Transmission

Transmission is the spread of pain impulses through sensory nerves of various types in the peripheral nervous system (PNS) to the spinal cord and up the ascending tracts to the brain. Some pain nerve fibres are classified as fast fibres and others as slow fibres. Fast fibres, found in skin and mucous membranes, transmit pain that is sharp and well defined, whereas slow fibres conduct impulses more slowly and pain appears to grow in intensity. It is described as dull, diffuse and aching, and continues after the event, such as the pain felt after removing a foot from a bath that is too hot.

The nerve impulses are processed in the ‘pain gates’ in the spinal cord. Other fast fibres that transmit touch or pressure impulses from receptors in the periphery and descending impulses from the brain both influence the ‘pain gate’, which may remain open to transmit pain or close and prevent pain transmission. If the dominant sensation is from touch receptors that release inhibitory chemicals, the ‘pain gate’ may close. This is the basis for the use of local pressure, massage and other non-pharmacological coping strategies used by patients to help shut the ‘pain gate’ (see pp. 673–677).

Many of the pharmacological treatments for pain act by interfering with the transmission of pain impulses along the pathway between the tissue injury and the cortex of the brain, e.g. local anaesthetic drugs administered as topical cream or gel.

Modulation

Modulation describes the inhibition of pain impulses by neural and chemical influences on the ‘pain gate’. Nerves that descend from the brain stem to the spinal cord close the gate by releasing endogenous opioids, e.g. endorphins (Box 23.5). This is why nociceptive pain is responsive to opioids such as morphine. Endogenous opioid modulation may also explain the variation in pain perception seen in clinical practice. Some individuals have more effective modulation than others (McCaffery & Pasero 1999). In experimental studies, the placebo effect is identified where subjects show an analgesic response to a masked inert drug (e.g. sugar pill versus analgesic). Some subjects respond, whereas others are non-responders. Placebo responders represent a group with a highly developed endogenous opioid system.

Other modulating substances identified are the neurotransmitters 5-HT and noradrenaline (norepinephrine). Drugs such as amitriptyline can be used as adjuvants to assist the action of other analgesics for neuropathic pain by preventing the reuptake of released 5-HT and noradrenaline (norepinephrine).

Modulation is triggered from higher brain centres and allows the psychological influences on pain perception to be explained. For example, negative or positive past experi-ences – anxiety, fear and depression, or relaxation and optimism – all influence pain modulation, either opening or closing the ‘pain gate’. Modulation may also be influenced by genetic factors, age and pain type, which could influence the endogenous opioid mechanisms.

Perception

There is no central pain centre within the brain but opioid-binding sites have been found in several areas in the brain, indicating that they are involved in pain percep-tion. Pain perception is a complex process involving the sensory impulses relayed from the ‘pain gates’ and activation of pain responses via the limbic (‘primitive’ area of the brain that influences feelings and emotions) and autonomic nervous system (ANS) to develop a pain experience that includes emotional and subjective sensory components. Immediate responses associated with acute pain and activation of the sympathetic nervous system include heightened awareness and anxiety. Longer-term responses to chronic pain involve behavioural adaptations, and psychological and social changes.

Psychological factors influence pain perception; for example, emotional distress, anxiety and helplessness are recognized as increasing the pain experience and are of significance in clinical practice. Sarafino (2002) notes the importance of psychological, social and behavioural factors that become more dominant in chronic pain. Cognitive behavioural therapy (Morley et al 1999) may be used in chronic pain to change people’s thoughts and behaviour and to enhance coping skills, so improving quality of life.

Individual pain responses are influenced by appraisal and past experiences. Responses are also modified by culture and social conditions and children learn during their upbringing about acceptable pain behaviour for their social group. McCaffery and Pasero (1999) note that some societies value a stoic response to pain, probably closely aligned with valuing high pain tolerance (see p. 660). This can lead to judgemental, negative attitudes to less stoic histrionic expression of pain. This is why the patient’s direct communication of their pain experience must be encouraged, as it is the most valid assessment. Individual differences lead to great variations in the pain experienced and in how it is expressed by similar pain-provoking stimuli. An individual’s pain cannot be predicted with accuracy.

Physiological and behavioural responses to acute pain

It is important for nurses to understand common physiological and behavioural responses to acute pain. This is important as part of pain assessment (see pp. 661–667), particularly so in patients or clients unable to describe their pain, e.g. babies, people with dementia or people with learning disabilities and associated communication problems. The responses may be:

Pain threshold and pain tolerance

Pain threshold, or pain perception, is described as the lowest intensity at which a stimulus is experienced as pain. This relates to the point at which the painful stimulus is first felt and the amount of pain that subsequently ensues. The pain perception threshold is relatively constant and not, as is commonly thought, something that varies widely between individuals and cultures (Davies & Taylor 2003).

Pain tolerance relates to intensity or duration of pain and the maximum amount of pain that an individual is willing, or capable, of enduring. Pain tolerance may vary between and within individuals at different times, and may be influenced by emotional and cultural factors (see p. 660); pain tolerance is often referred to as being high or low (Box 23.6, p. 660). Thus an individual with high pain tolerance can withstand intense or protracted pain over an extended period before requiring pain relief. Conversely, the opposite is likely to be true for those individuals with low pain tolerance. There is little evidence to suggest that children have different pain tolerance from adults although there may be a link between the age of the child and their pain threshold.

Pain psychology – personal and sociocultural influences

The pain experience is the end result of a number of dynamic interrelated factors. Recent thinking has moved away from the notion of personality and overt pain behaviours to focus interest on the mental processes, e.g. comprehension and memory, that mediate pain behaviours. It is now recognized that children can and do remember their pain experiences and learn from modifying their responses to future episodes, e.g. injections or visits to the dentist. There has been a view that neonates were unable to remember pain; however, there is now increasing evidence to support the fact that infants do remember pain (Carter 1994). Furthermore, the interrelationship between pain, fear and anxiety has been extensively investigated over time and evidence suggests that anxiety and fear undoubtedly magnify pain perceptions, particularly in children. Recent studies have included other variables including memory, locus of control, self-efficacy, coping mechanisms/styles and depression (Box 23.7).

Box 23.7  EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

Depression and chronic pain

Depression associated with chronic pain has been the subject of much research over the years. Lin et al (2003) report that treating depression in older people with arthritis can reduce their pain and improve functional status and quality of life.

Student activities

[Reference: Lin EHB, Katon W, Von Korff M et al 2003 Effect of improving depression care on pain and functional outcomes among older adults with arthritis. JAMA 290(18):2428–2429]

The influence of culture on the perception of pain has been extensively documented. There is evidence to support the fact that pain and culture are closely linked, especially when responses and behaviours are closely aligned to culturally specific traditions, rules and rites of passage associated with a particular culture. For example, in Africa the men of the Kikuya or Masai tribes are expected to respond to pain with dignity and composure, whereas it is acceptable for the women to wail and cry. There is some evidence to suggest that the further that an individual is away from the original immigrant population, the less culturally specific the behaviours become. Therefore, a pain response may be modified or diluted according to the multicultural society in which the person lives. Zborowski (1952) reported differences in pain responses between ‘old’ Americans and more recent Jewish or Italian immigrants: the ‘old’ Americans were unemotional and generally optimistic, whereas newer immigrants were frank in their pain expression and sought more sympathy.

Studies related to children, culture and pain found similar features to those found in adults. However, nurses view the child and family as part of a sociocultural group and a multicultural approach to pain management is crucial to manage the child‘s pain experience effectively. Of equal importance are the implications of culture and ethnicity for nurses who will all have their own values, attitudes, beliefs and explanatory models of health and illness (see Ch. 1) (Box 23.8).

Values, beliefs and attitudes towards pain

Think about your own values, beliefs and attitudes towards pain and the episodes that formed these. For example, can you remember people saying ‘rub it better’ when you fell over as a child?

Myths, misconceptions and facts about pain

The complexity of pain makes it difficult to define, describe, explain and measure, thus increasing the likelihood that pain is underdetermined and undertreated. However, there is a school of thought which proposes that complete relief from pain is not achievable or necessarily desirable, especially after minor injury or surgery where low intensity pain limits overexertion. Moreover, pain is a valuable diagnostic tool and can be a learning mechanism. However, pain that is severe and prolonged, or which limits activity and movement, can be detrimental to recovery and general well-being (Box 23.9).

Box 23.9 Detrimental effects of pain

Respiratory effects (see Ch. 17)

Cardiovascular effects (see Ch. 17)

Gastrointestinal effects

Nervous system and hormones

Poor/reduced mobility (see Ch. 18)

Moreover, enduring myths, misconceptions relating to false judgements, mistaken beliefs or misunderstandings surrounding pain all reflect prejudice, outmoded beliefs and lack of knowledge and understanding. Collectively these present healthcare professionals with enormous challenges to manage pain effectively, as knowledge and beliefs relating to pain and its subsequent management are the foundations upon which healthcare professionals make judgements and decisions.

A number of myths and misconceptions flourish, despite these having been disproved by sound evidence. In particular, two such myths that continue to perpetuate the undertreatment of pain relate to fears about respira-tory depression and addiction from the use of strong opioid analgesics, e.g. morphine. Box 23.10 (p. 662) outlines some pain myths and facts.

Box 23.10 Pain myths – fact or fiction

Myths (false)

Facts (true)

In order to dispel myths and misconceptions, nurses need to attain and maintain up-to-date evidence-based knowledge about pain and practical experience of relating this knowledge to preventing and managing pain. According to Davies and Taylor (2003), nurses require knowledge about:

Pain assessment

There are several good reasons why objective and systematic assessment of pain is necessary. Article 3 of the Human Rights Act (1998) states that ‘no one shall be subjected to torture or to inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment’. This part of the chapter provides an outline of how pain is assessed.

McCaffery and Pasero (1999) summarize the essential message about pain assessment as:

Pain assessment is cyclical, involving assessment, intervention and reassessment.

Pain assessment therefore sets the tone for the thera-peutic relationship formed with the patient/client/family in the assessment and treatment process, and underpins the respect and concern of the healthcare team. Further-more, assessment is the foundation for therapeutic pain management. In acute pain the objective of assessment might be to evaluate the need for and effectiveness of medication, whereas in chronic pain the focus is on how the pain affects the person’s ability to function normally. One of the purposes of assessment is to facilitate objective clinical decision-making in pain management.

Pain is not a unitary phenomenon; it is multidimensional and a holistic assessment needs to address all aspects of the pain experience, the critical components of which are:

Holistic pain assessment

Determining the level of pain that an individual may experience is one of the most challenging yet common tasks that nurses undertake. However, it is important to distinguish between pain measurement and holistic pain assessment. Pain measurement measures pain on a scale relating to the intensity of pain without considering any of the other components of pain. In contrast, pain assessment is a broader notion that requires different know-ledge and skills including pain measurement.

When assessing pain, nurses should be measuring not only the severity of the pain but also what the experience means to that person. However, it is notable that there is a difference between pain measurement and assessment, and when these definitions are applied to human suffering it requires the nurse to evaluate the whole experience and what it means to the person. Melzack and Katz (1994) proposed that the main aims of pain assessment are to:

The assessment of pain is important because it provides the person with the opportunity to verbalize their pain (if able), takes account of the personal pain experi-ence (Davies & Taylor 2003) and engages the person and/or their family with healthcare systems.

The ‘gold standard’ is always to ask the person about their pain experience. Assessment will be influenced by the person’s ability to respond and the type of pain will also influence assessment priorities, e.g. priorities will be different in the following situations:

Communication skills are essential for effective pain assessment; the person needs to be encouraged to report their pain (see Ch. 9). If the person’s condition allows, use open questions that allow them to elaborate upon their pain episode. For example:

The potential barriers and differences in pain expression, e.g. due to culture, age, personality, gender and cognitive ability, need to be acknowledged by the nurse. However, for some people verbal communication may be difficult, absent or not yet developed. Furthermore, cultural and language difficulties may hamper the assessment process.

Behavioural responses to pain

Behavioural responses to pain are important in the assess-ment of all patients/clients but can be especially relevant when people are unable to verbalize their pain. Although there are only limited pain assessment tools available for vulnerable groups, it is important to understand that people with special needs experience pain the same as everyone else. It is vital that nurses recognize that they may be unable to verbalize their pain or explain it clearly. Vulnerable people include the following:

Certain behaviours are useful for identifying patients/clients who may be experiencing pain (Box 23.11; see also p. 659). In situations where verbal communication is limited or impossible, observations of behaviour alone can be used.

In addition to the limited availability of assessment tools for vulnerable groups, there may also be a culture where lack of assessment hampers effective evaluation of pain management. Furthermore, pain assessment can fail if there is poor communication between the nurse and the patient/client or family.

Pain language

There are many words used to describe the pain experi-ence (Box 23.12). Many patients/clients and children develop their own pain language and behaviours that communicate pain. Instead of the word pain, depending upon the age and stage of development, children may use words such as ‘baddie’, ‘nasty’ or ‘hurt’ (Carter 1994). Descriptions of pain expressions may have little or no meaning outside the family and reinforce the need for partnerships and child and family-centred care in pain management with infants and children and others with communication difficulties. Therefore, identifying pain language in children and adults, including those with a learning disability or older people, is important for the delivery of high quality care and also informs the assessment process.

Assessing children’s pain

Until recently, pain in children was not recognized or prioritized, resulting in poor pain management (Twycross et al 1998). Infants and children have the right to careful consideration as they may experience pain differently from adults. The child’s experience of pain is often separate from their experience of their illness or disease. As with adults, children have different experiences and reactions to pain from the same stimulus, and the relationship between the pain stimulus and the response is neither direct nor simple.

An understanding of how children develop their understanding of health and illness will enhance the quality of care offered to each child (see Chs 1, 8). Evidence suggests that most health professionals do not approach children according to their developmental level but rather address all children according to Piaget’s (1924) concrete operational stage of development (see Ch. 8). Therefore, knowledge about how a child’s understanding of illness develops will mean that age-specific explanations can be given to the child, thus reducing the anxiety and distress that children suffer during hospitalization (Twycross et al 1998). A child’s developmental stage affects their perception and ability to adequately report or express the pain they are feeling.

Children have the right to feel secure and to be nursed in an atmosphere where compassion, trust and caring are at the centre of all decisions. These principles must underpin the child’s pain assessment and management, with the child central to all considerations and decisions.

The QUESTT model (Baker & Wong 1987) encompasses many important features of assessment and involves:

This model provides a comprehensive overview of the child’s pain and informs the treatment and therapeutic management.

Pain history

Establishing a pain history is important as it will not only identify previous pain experiences, but may also offer insights into how the person’s knowledge and perception have influenced and shaped coping strategies, and how this may influence the current situation. This is particularly important for vulnerable groups, e.g. older or confused clients. Children can be better prepared for painful procedures by comparing the previous experience with the new experience and often children develop strategies that compare one situation with another. Furthermore, pain behaviours may be an integral part of the pain history and behavioural cues may be important pain indicators. Being sensitive to pain indicators may mean that practitioners can intervene at an early stage before pain is fully established. It is also useful to establish if there are separate behaviours relating to sudden acute pain compared to chronic pain. Again this is important in patient/client populations where there may be difficulties in articulating pain.

Pain diaries

These are useful tools for the assessment of chronic pain and a means of reflecting upon the many components of pain, e.g. physical, emotional, social. They can also include numerical ratings and descriptions of pain (see Box 23.12, p. 663).

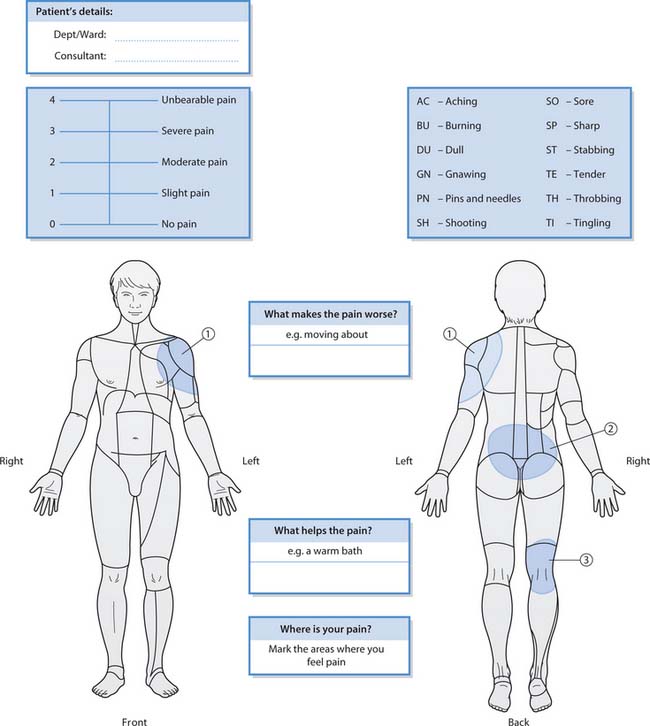

Pain maps

The patient, if able, is asked to identify, mark or sketch areas on a body outline or ‘body map’ that reflects the area(s) of pain (see p. 667). Pain maps are used increasingly as part of the assessment process, especially for patients with complex chronic pain. Pain maps can empower the patient during the assessment process; they can be used across the lifespan and are important tools for informing decisions about pain management and providing a basis for evaluating the effectiveness of treatment.

Pain assessment tools

A pain assessment tool must be reliable and valid. The term reliability relates to the issues of consistency, stability and the repeatability of measurements made by different nurses; validity refers to the appropriateness, applicability and the representativeness of measurements made as true findings of an individual’s pain at any given time. There are different types of pain assessment tools that can be classified as follows:

There are wide variations in the levels of sophistication of these tools and also between approaches to pain assessment. Pain assessment tool selection must be based on the patient’s age and ability, a child’s developmental stage, patient preferences, amount of time available to teach the patient about the scale and the knowledge of the nurse (Box 23.13).

Box 23.13  EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

Choosing the most appropriate pain assessment tool

Studies have identified that patient preference is important with practical acceptability of tools.

Student activity

Access one of the articles and discuss with your mentor how the findings could be used effectively with your patient/client group.

[References: Benesh L, Szigrti E, Ferraro R, Naismith Gullicks J 1997 Tools for assessing chronic pain in rural elderly women. Home Healthcare Nurse 15(3):207–211; Herr K, Mobily P 1993 Comparison of selected pain assessment tools for use with the elderly. Applied Nursing Research 6(1):39–46; Manfredi P, Breuer B, Meier D, Libow L 2003 Pain assessment in elderly patients with severe dementia. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 25:48–52]

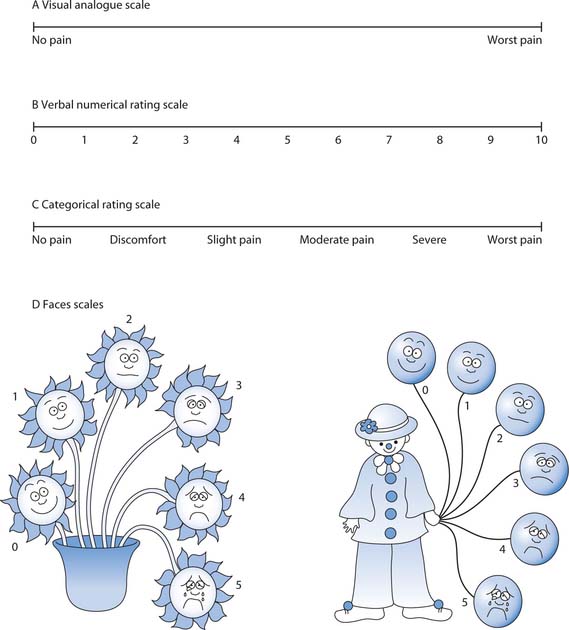

Self-report scales

Self-report assessment scales include visual analogue scales (VAS), verbal numerical rating scales and categorical verbal rating scales but can also include pain interviews or questionnaires that incorporate variables such as coping skills (Fig. 23.5). Self-report scales can be modified; for example, the pain ‘thermometer’ scale or by using a child’s own words on the scale, e.g. ‘worst hurt’ (Box 23.14, p. 666). They can also be used with pain maps or pain diaries.

Fig. 23.5 Self-report pain scales: A. Visual analogue scale. B. Verbal numerical rating scale. C. Categorical rating scale. D. Faces scales

Visual analogue scale

The visual analogue scale (VAS) is usually a 10 cm horizontal line with indicators of severity such as ‘no pain’ at one end to ‘worst pain possible’ at the other end (Fig. 23.5A). Patients mark the position on the scale that best reflects their current pain. This is also a useful tool for children, but the child needs the ability to translate their experience into an analogue format and to be able to understand proportions (from 9 or 10 years).

Verbal numerical rating scales

Verbal numerical rating scales are based upon the VAS but use a scale where 0 is ‘no pain’ and 10 is ‘worst possible pain’ (Fig. 23.5B). These usually provide a more reliable means of measuring pain and can be used with descriptions as well as numbers.

Categorical rating scale

One of the most commonly used tools in the postoperative period, it offers the patient a series of terms that best describes their pain (Fig. 23.5C). It has been found to be simple and effective to use in clinical practice and can be incorporated into an observation chart. Pain on movement rather than at rest is an important area to assess. Pain intensity at rest is not a reliable indicator of effective pain management, especially postoperative pain.

Self-report scales for children

Self-report scales for children include:

For a comprehensive account of pain assessment tools for infants, children and adolescents, see Further reading (e.g. Hockenberry et al 2002).

Observation techniques

This involves recording variables that may include:

Observational tools used for adult pain assessment and measurement show potential when trained observers are used and there are clearly defined terms and boundaries. A number of observational tools have been developed to assess the pain of children aged 0–5 years, who are unable or less able to use self-report scales. Observation may also be useful in cases where self-report tools may be unreliable or unsuitable, as with people with a learning disability and those with communication or language difficulties.

Physiological measurements

The quest for objectivity in pain assessment has led some researchers to measure functions such as increased heart rate, feeling faint, etc. or disease activity as equivalents for the experience of pain (Box 23.15).

Physiological measurements and changes

Marie has just fallen and broken her arm. She does not speak English and is unable to tell you about her pain.

Student activities

Physiological measurements such as respiratory rate, blood pressure, heart rate and oxygen saturation (see Ch. 17) have their limitations. However, they are used for neonatal pain assessment because there are few other comprehensive neonatal assessment tools available.

Multimethod approaches to pain assessment

These approaches give richer information regarding the pain experience of the patient/client and often pain assessment tools combine quantitative and qualitative elements (see Ch. 5). One such tool is the Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale (PASS) which incorporates three modes: cognitive, overt behaviour and physiological, including reports of changes, e.g. sweating, feeling faint and dizzy, etc. Various multimethod approaches exist for assessing pain in children and young people (see Further reading), e.g. the Pain Assessment Tool for Children (PATCh) which includes:

Assessment for different types of pain

The choice of assessment method must be appropriate for the person and the pain type. In acute pain a self-report scale such as the categorical rating scale, which concentrates on pain intensity alone, is often sufficient for evaluation of interventions, especially if there is a single pain location.

However, with chronic pain a body map is frequently required to improve multidisciplinary recognition and communication of pain location and pattern. For patients with cancer-related pain, a body map is essential because as the cancer advances several pain locations may develop (see Ch. 12). The different pains locations require regular reassessment as the disease progresses. In addition, the impact of the pain on mood and behaviour are important considerations. These will be missed if a simple self-report scale is used.

Questions that explore quality of sleep and the impact of pain on mobility and social interaction are valuable. Patients are asked about what makes the pain better or worse, thus helping to identify characteristics that may be of value in evaluating treatment options and coping skills that people may have developed. The quality and character of pain may guide pharmacological management, e.g. a pain described as ‘shooting’ may be neuropathic such as after shingles (see p. 655). Pain clinics and specialist nurse practitioners use detailed tools and may ask people to complete pain diaries in order to evaluate the pain experience comprehensively.

Figure 23.6 illustrates an example of a more comprehensive assessment tool that combines a body map, self-report scale and description of the type of pain with factors that increase or decrease pain.

Pain management

This part of the chapter outlines holistic pain management, principles of pharmacological pain relief and a variety of non-pharmacological approaches used to enhance coping strategies. Pain may be a primary reason for care or it may be an existing problem not related to the person’s current healthcare needs. Bruster et al (1994), in a comprehensive survey of hospital experiences in England, found pain management to be an area of concern: 61% of patients interviewed suffered pain, 33% had it all or most of the time and for many the pain was severe or moderate.

Effective pain management is complex and requires a holistic approach, starting with a thorough assessment (see pp. 661–667). The type of pain and the person’s response are important factors to consider when planning strategies for pain management. Pain management usually involves a combination of pharmacological and non-pharmacological measures.

Mild acute pain following minor injury may be easy to resolve with simple painkillers, measures such as an ice pack and sympathetic listening and support from the nurse. Many hospitals now have acute pain teams to support pain management following surgery and act as a resource to clinical staff.

However, for chronic pain a multidisciplinary approach is most effective and that management takes place in hospital and in the community. The MDT may involve pain specialist consultants, pain nurse specialists (Box 23.16), physiotherapists, occupational therapists, clinical psychologists and pharmacists. Support for patients with chronic pain depends on the cause of the pain, but advice and help are available from palliative care specialists (see Ch. 12) and specialist pain clinics.

Pharmacological management

Depending on the pain type, patient’s age and setting, there are a range of pharmacological approaches available including the use of analgesics (widely described as painkillers). The nurse has a key role in teaching patients and family about the safe management of drugs including analgesics (Box 23.17; see also Ch. 22). The variability in individual responses to analgesics gives nurses a key responsibility in monitoring effects and side-effects in order to achieve successful pain management.

Aspirin and Reye’s syndrome

A friend asks you why he should not give aspirin to his 8-year-old son. He has heard someone talking about a serious side-effect and is confused about which over-the-counter painkillers are safe for children. He wants to know some basic facts and where to get information.

Student activities

[Resource: http://www.mhra.gov.uk/home/idcplg?IdcService=SS_GET_PAGE&nodeId=132 Available July 2006]

Increasingly, registered nurses (RNs) who have completed additional training are able to prescribe analgesics from the Nurse Prescribers’ Formulary for Community Practitioners and ‘qualified Nurse Independent Prescribers (formerly known as Extended Formulary Nurse Prescribers) are now able to prescribe any licensed medicine for any medical condition within their competence, including some Controlled Drugs’ (DH 2006). Communication between members of the MDT, which includes the patient and family, is essential. The nurse may need to act as an advocate for the patient to ensure adjustment of the analgesic prescription to achieve acceptable pain management.

Age and analgesic drugs

The patient’s age is an important consideration when analgesics are chosen: the drug type, dose required and the most suitable administration route. Infants, children, adults and older people have different body compositions (see Ch. 19) and the metabolism and elimination of drugs are affected by the stage of development.

The amount of water as a percentage of body weight decreases during the lifespan. For example, a neonate has around 75% water whereas an adult male has around 60% and an older adult between 45 and 50%.

Infants and children metabolize and eliminate drugs differently from adults and this must be considered in the dose calculations. For example, neonates and premature infants are particularly vulnerable to the harmful effects of drugs because liver enzyme systems and kidney function are immature and plasma protein concentrations are low. In children, weight, height and age are important in calculating drug doses (see Ch. 22).

There are also important considerations for the older person as reduced metabolism and excretion of drugs can result in accumulated effect and reduced doses may be required. In addition, polypharmacy causes concern with drug interactions. Poor pain management can significantly reduce quality of life, particularly in chronic pain. Effective pain management is essential in maintaining optimum independence and mobility in older people. This is a particular concern for older people with dementia who are more likely to suffer chronic pain but be unable to express their pain.

Drugs used in pain management

These can be divided into three groups: non-opioids, opioids and adjuvants (Table 23.2).

Table 23.2 Drug groups used in pain management

| Drug group | Examples | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Non-opioid | Aspirin, paracetamol, NSAIDs, e.g. ibuprofen, diclofenac, and local anaesthetics, e.g. lidocaine | Non-opioids work in a variety of ways, e.g. NSAIDs inhibit the production of ‘algesic’ stimulate the pain-sensitive nociceptors which mediate the inflammatory response |

| Opioid | Buprenorphine, codeine, dihydrocodeine, diamorphine, fentanyl, methadone, morphine, pethidine, tramadol | Opioids are a group of naturally occurring (extracted from opium poppies) and synthetic analgesics |

| They act on opioid receptors in the central nervous system and block pain transmission by mimicking the effects of naturally occurring endorphins at the receptors, thus making pain feel less | ||

| They range in strength and efficacy from the weak opioid codeine to morphine | ||

| Adjuvant | These include: | Adjuvants act to enhance the action of analgesics, e.g. amitriptyline enhances pain modulation and is useful for neuropathic pain |

| • Anticonvulsants, e.g. carbamazepine | ||

| • Antidepressants, e.g. amitriptyline | ||

| • Antispasmodics, e.g. hyoscine butylbromide | ||

| • Capsaicin (derived from chillies) | ||

| • Corticosteroids, e.g. dexamethasone |

Nurses need to develop an adequate knowledge of analgesic action and potential side-effects (Box 23.18). Unfortunately there are no perfect analgesics; all drugs that relieve pain also have side-effects. These range from mild light-headedness to more troublesome problems that occur with opioids that include constipation, nausea and sedation, up to life-threatening respiratory depression, or NSAID-induced gastric ulceration or kidney failure. The nurse is responsible not only for the evaluation of pain reduction but also the occurrence of side-effects.

Side-effects of analgesic drugs

Select two or three examples from each group in Table 23.2 (non-opioids, opioids and adjuvants).

Student activities

Mild sedation can be a useful side-effect in the management of acute pain, e.g. following major trauma, surgery or heart attack, as it will reduce anxiety and distress. However, for chronic pain management, independence with minimum disruption to daily living is important; frequent administration is therefore undesirable and side-effect management is essential, e.g. minimal sedation.

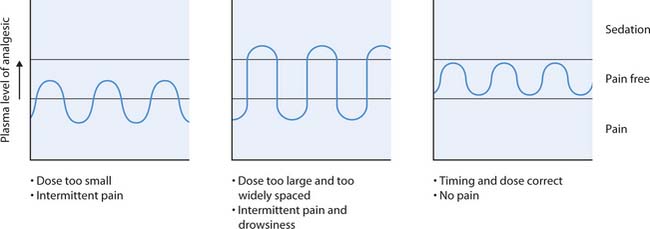

With opioid analgesics such as morphine, the higher the dose, the greater the risk of side-effects. The dose is therefore increased in graduated amounts known as titration, which allows optimum pain relief without adverse side-effects (Fig. 23.7, p. 670). However, knowledge of likely side-effects allows pre-emptive action to be taken, e.g. ensuring that laxatives are always prescribed for patients who are having regular long-term codeine or morphine.

When an adjuvant drug, e.g. amitriptyline, is prescribed it may take days or weeks before there is a therapeutic effect. This must be explained, as patients will be disappointed if they were expecting a prompt response and may discontinue the therapy. Starting adjuvants at a low dose and gradually increasing the dose helps to reduce side-effects and improves patient tolerance.

Routes of administration

The routes used for the administration of analgesic drugs include:

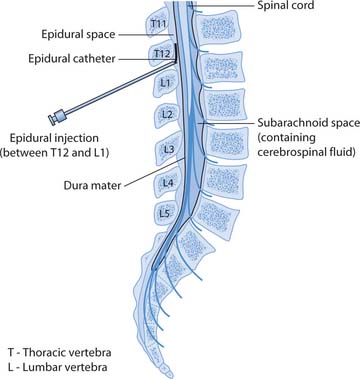

Nurses need to know about different routes of administration and should be familiar with relative advantages and disadvantages of each route (Ch. 22). Analgesic administration may be low technology, e.g. independent self-administration of oral drugs at home where the nurse’s role is educational, or – in contrast – invasive, high technology approaches where drugs are introduced into the epidural space outside the dura mater (the outer meningeal layer covering the spinal cord; Fig. 23.8), used in clinical areas to manage severe pain with additional staff training and support from pain teams. In general, the analgesic approach should be appropriate for the pain type and intensity, and should suit the person concerned.

An important consideration is the flexibility and availability provided by different routes of administration. In acute severe pain the route needs to be fast acting and the dose easily adjustable to allow optimum effect without development of adverse side-effects. The most widely available routes for adults are i.m. and s.c. opioid administration; the effectiveness of these routes has been greatly improved by the use of algorithms by RNs to provide greater flexibility to meet individual patients needs. Readers requiring more information about the use of algorithms for postoperative pain relief are directed to Davies and Taylor (2003).

Opioids may be required for chronic severe pain, e.g. modified release morphine given twice daily or transdermal fentanyl (patch). Transdermal fentanyl takes 12 hours to reach therapeutic levels but lasts 3 days, thereby avoiding the inconvenience of frequent administration and allowing the patient to get on with their life.

The most common routes of administration (p.o., i.m., i.v.) rely upon sufficient quantity of the drug reaching the circulation to achieve therapeutic effect. An injection is not necessarily more powerful than an oral drug, a common misconception; the analgesic should be matched to pain intensity and a suitable route chosen. The i.v. route allows for rapid therapeutic effect to be achieved within 5 minutes, which makes patient-controlled i.v. administration a fast and flexible method of managing acute pain. Intramuscular and s.c. routes have a delayed onset as the drug has to be absorbed from the muscle or fat before it can reach the circulation.

The oral route can be as fast as i.m. if the drug is designed for rapid absorption. Avoidance of painful injection is essential in children and often desirable in adults because treating pain with injections can lead to reluctance to report pain. It is important to note that oral morphine is subject to first pass effect/metabolism in the liver (see Ch. 22), thus explaining why the oral route requires a dose higher than that given by i.v. or i.m. injection. This has important safety issues for the nurse (see www.bnf.org.uk).

Patient-controlled analgesia

Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) usually means i.v. administration but also includes inhaled nitrous oxide and oxygen (Entonox®), and s.c. or epidural administration (Ch. 24). Specialized equipment is needed for safe administration of analgesics by these routes and PCA requires patient education and reassurance. Children can safely self-administer inhalation, i.v. or s.c. PCA.

Because PCA administration relies on the fact that a sedated patient will not be able to administer more analgesia, so therefore cannot overdose; carers and staff must understand they should not administer for the patient.

Regular assessment and management of nausea, a common side-effect of opioids, is important. This is particularly so with i.v. PCA, as the patient is unlikely to use it effectively if they feel sick every time they press the button. It is important that there is regular assessment of postoperative nausea and vomiting (see Ch. 24).

Readers requiring more information about PCA are directed to Davies and Taylor (2003) and Greenstein and Gould (2004).

Administration of analgesic drugs

Analgesics with a fast onset and short duration of action need to be administered frequently to maintain therapeutic effect and prevent pain, e.g. oral morphine liquid 4-hourly. This is why the ‘as required’ (p.r.n.) approach to pain management, which relies on patients reporting pain, is criticized; the intermittent administration results in regular pain with periods of relief. Good pain management requires regular administration of a suitable analgesic to avoid pain (Fig. 23.9). Regular administration ‘by the clock’, or techniques which allow the patient to administer as soon as pain is present, e.g. by using i.v. PCA, have greatly improved pain management. Many patients manage pain at home following early discharge or day case surgery. Advice is required about taking painkillers regularly to avoid pain at first and how to step down the ‘analgesic ladder’ (see below) to milder analgesics as the pain subsides. Advice regarding avoidance of constipation (see Ch. 21) should also be included if opioids are prescribed.

Fig. 23.9 Adjusting the dose to keep the patient pain-free

(reproduced with permission from Greenstein & Gould 2004)

Analgesic potency

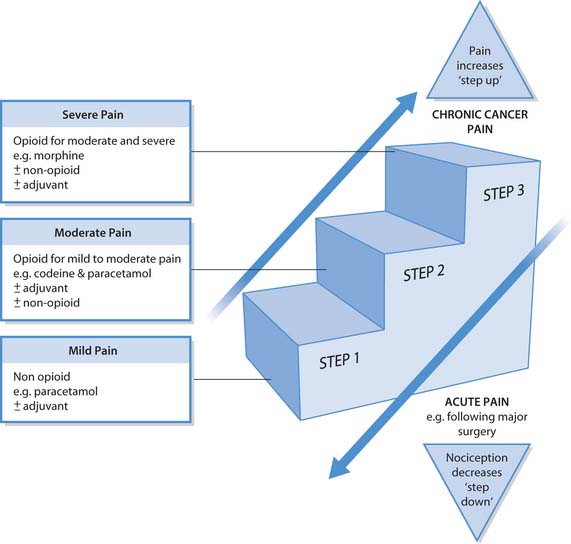

Pain management is achieved by administration of the most suitable analgesic drug combination. The pain type (acute or chronic) and intensity (mild, moderate or severe), the patient’s age and individual sensitivities are all important considerations. A useful tool when considering the choice of analgesic is the ‘analgesic ladder’ (World Health Organization [WHO] 2005), which groups drugs into categories that match analgesic potency with pain intensity (Fig. 23.10, p. 672; see also Ch. 12):

This ladder was first proposed for use by the World Health Organization in the management of cancer pain in the 1980s; however, it is also useful to consider when matching analgesic prescription to pain intensity for other pain types. It can be used to guide analgesic prescribing in any patient setting, e.g. community, Emergency Depart-ment and hospital. Postoperative pain relief often starts at the top of the ladder and steps down as pain subsides. In contrast, for chronic malignant cancer pain the analgesia will be adjusted as pain intensity increases with advan-cing disease; for many patients this approach has been successful in achieving good pain control (see Ch. 12).

Box 23.19 outlines a study by Moore et al (2003) that compared analgesic effectiveness in acute pain.

Box 23.19  EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

Analgesic effectiveness

Moore et al (2003) compared the effects of various analgesics used in acute pain management. Their findings include:

Student activities

[From Moore et al (2003)]

A combination of analgesic drugs, known as the balanced or multimodal approach, may be required for effective pain management. This can enhance pain management because less opioid is required (opioid sparing) when given in combination with other drugs and thus reduces side-effects (Broadbent 2000). Examples include oral co-codamol (paracetamol and codeine) and epidural administration of an opioid with local anaesthetic. In combination, the drugs target different areas involved in pain physiology (see pp. 657–659), which appears to improve the analgesic effect.

Pre-emptive and procedural pain management

The principle of providing analgesia before tissue injury to minimize pain is generally accepted as good practice. Some patients require repeat procedures and previous poor pain management can make patients fearful and reluctant to participate again. This is a particularly important issue for children and leads to further distress. Furthermore, poorly managed procedural pain is thought to contribute to physiological changes, which in some patients have been linked to chronic pain development (Carr & Mann 2000). Certain procedures in clinical practice, e.g. taking blood samples, cannulation, painful dressings and postoperative physiotherapy, are recognized as causing pain, and planning care to minimize this is essential. Both pharmacological treatment and psychological support are required. The management of proced-ural or transitory pain can be achieved by a variety of techniques:

Topical local anaesthesia before cannulation

Sophie, who is 19 years old and has a learning disability, needs to have an i.v. cannula sited for drug administration.

Drug tolerance and dependence

The use of analgesics is influenced by drug tolerance, dependence and addiction. A common misperception that opioid analgesics lead to addiction has a negative influence on pain management. Several authors (Carr & Mann 2000, Mann 2003) identify that nurses and patients have exaggerated fears about addiction risk with opi-oids. This affects drug prescribing by medical staff, pain reporting by patients and drug administration by nurses leading to unrelieved pain.

The management of pain in people who misuse drugs often requires support from the acute pain team, as drug tolerance means that larger doses will be needed. The route of administration also requires careful consider-ation: regular i.m. administration, for example, would not be desirable, as it encourages dependence on an invasive approach (Box 23.21, p. 674).

Opioid misuse and pain relief

Leo has been admitted for major surgery but providing postoperative pain relief is complicated by his regular misuse of heroin. The acute pain team is able to prescribe an analgesic regimen to relieve his pain. Although the focus of immediate care remains effective postoperative pain management, rehabilitation will hopefully become a goal for the future. Drug rehabilitation requires skilled specialist support.

Non-pharmacological methods of pain control

Over recent years non-pharmacological methods of pain control such as massage and the use of essential oils have become more widely accepted within conventional healthcare systems, although many still lack robust evidence of efficacy. Information giving is pivotal in pain control, as fear of pain increases pain perception (see pp. 659, 675). An outline of some methods is provided here but readers are directed to Further reading (e.g. Rankin-Box 2001).

It is vital that nurses understand the importance of simple (but by no means trivial) comfort measures that can be initiated as part of pain management, e.g. a carefully placed pillow (Box 23.22, p. 674).

Comfort measures

Think about the comfort measures that you use to decrease pain and discomfort. For example, after a busy shift you may rest your aching legs on a chair or in a warm bath, or use a hot water bottle to relieve ‘period pain’.

Pain type, severity and the patient’s age are import-ant factors to consider when planning the use of non-pharmacological approaches to pain management. It is also important to note that the patient’s mental and emotional state are important in pain management and, as these are likely to vary over time, can affect the severity, tolerance and expression of pain.

Non-pharmacological methods can be classified into two groups: physical (counterirritation) and psycho-logical. However, some methods, such as massage, have both physical and psychological benefits. Box 23.23 outlines some physical and psychological methods.

Box 23.23 Examples of non-pharmacological methods – psychological and physical (counterirritation)

Many non-pharmacological methods are complementary therapies or alternative therapies and more detailed coverage of some of these is provided in Chapter 10 and in Further reading suggestions (e.g. Rankin-Box 2001).

Effective holistic pain management usually requires a combined pharmacological and non-pharmacological approach. In acute severe pain the dominant intervention is usually pharmacological along with explanation, anxiety reduction, emotional support and appropriate touch. Distraction and relaxation require patient participation as well as energy, which may limit their usefulness in severe pain. Relaxation is further limited in acute severe pain as there may be insufficient time to teach relaxation techniques. However, appropriate techniques can be taught in advance, e.g. prior to planned surgery.

Non-pharmacological methods of pain control (e.g. a visit to the hydrotherapy pool), which reduce pain perception by closing the ‘pain gate’, are probably most effect-ive as coping strategies in chronic non-malignant pain rather than for reducing the intensity of pain (see Fig. 23.3, p. 656 and Table 23.1, p. 657). There are some exceptions to this, such as cold applications, but the most likely outcome of techniques such as relaxation and distraction is that the pain may become more bearable but not necessarily less severe in intensity. Specialized practitioners may be available via the pain specialist services for chronic pain or for cancer patients.

Despite the obvious benefits of pain relief achieved by using non-pharmacological methods, nurses must ensure that they possess the appropriate knowledge and skills to deliver such techniques (NMC 2004; see also Ch. 7). It is also important to note that non-pharmacological methods may be overused in some circumstances and with certain people. For example, clients and patients who are cooperative and adapt to techniques such as distraction may suffer their pain in silence and not be provided with appropriate or adequate analgesia.

Simple comfort measures

These can improve the experience of the person in pain and include:

These measures are also valuable for patient/clients and their carers who can become actively involved, especially in the management of chronic pain.

Information giving

Effective communication (see Ch. 9) and the provision of high quality information are vital components of holistic pain management. Inadequate information leads to the fear of pain, especially when the cause is unknown, or fear of not coping and poor understanding of pain relief methods, which can all worsen pain (Box 23.24). RNs must ensure that patients/clients/parents have sufficient information about pain and pain relief. They should discuss options, give explanations and provide written information about methods of managing pain, all of which can help to minimize anxiety and fear. There are also many self-help books designed to help patients cope with pain.

Box 23.24  EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

Information and pain

Over 30 years ago, Hayward (1975) published the seminal study that considered how the provision of information affects pain.

Hayward’s study concluded that information about pain and its duration given preoperatively reduced the need for analgesic drugs after surgery.

Relaxation

Relaxation may provide relief from pain and/or reduce anxiety. It may not lessen pain intensity but may decrease the distress associated with the pain. A patient/client cannot usually be relaxed and anxious at the same time. Relaxation aims to decrease skeletal muscle tension, as muscle pain can heighten painful stimuli, and the gate control theory predicts that decreasing muscle tension will reduce pain sensation. Relaxation is an effective coping mechanism for chronic or procedural pain. It can be initiated with music therapy, and relaxation techniques (see Ch. 11) can be taught prior to, and in preparation for, painful procedures. A warm bath can also aid relaxation. For infants, holding them in a well-supported comfortable position and/or rocking them rhythmically can facilitate relaxation.

Snoezelen multisensory room/environments, initially developed for people with a learning disability to create an environment for sensory stimulation, have recently been used to promote rest and relaxation for patients with chronic pain as a way to promote their coping strategies (Schofield 1996).

Hypnosis

Hypnosis is defined as focused attention, an altered state of consciousness or a trance that is followed by a period of relaxation. Hypnosis is one way of achieving relax-ation and is useful in relieving the distress caused by pain and improving confidence. It may not take the pain away but reduces or removes pain perception by stimulating the higher centres of the brain so that they inhibit opening of the ‘gate’.

Distraction

Distraction is a means of putting the pain at the periphery of awareness (McCaffery 1990) and focusing attention on something other than the pain. The focus of attention is diverted to the ‘distracter’ rather than the pain. Distracters include:

Children in particular tend to be talented at using distracters as a means of pain relief. Additional distracters for children include:

The distracter can be increased or reduced according to the intensity of the pain (Box 23.25, p. 676).

Distraction in children

The use of play is important to help children bring some familiarity to an unfamiliar situation, such as the experience of illness and pain and the healthcare environment. Therapeutic play is structured by adults and followed through by the child who is given the opportunity to overcome fears and anxieties by bringing unconscious feelings to the surface such as in needle phobia (Trigg & Mohammed 2006).

Student activities

[Reference: Trigg E, Mohammed T 2006 Practices in children’s nursing: guidelines for hospital and community, 2nd edn. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh]

In children’s wards a play specialist may be available to support nurses with ‘play as distraction’. This is beneficial, as boredom can be a factor that opens the ‘pain gate’. Similarly, an activities coordinator working in a care home can arrange outings and social events that act as distracters for residents with pain.

Older people who live alone may find that social isolation is a negative influence on pain perception, as it is likely to open the ‘pain gate’. Therefore, encouraging social interaction and hobbies, e.g. lunch clubs, day centres, reading groups, that stimulate and distract may be valuable strategies in pain management

Imagery

Imagery is the use of imagination to modify pain responses and involves using sensory images to modify the pain – for example, that the pain is a balloon and the person is trying to blow the balloon (pain) as far away as possible. In doing so it makes the pain more bearable by providing a focus or substitution and organizes energies that facilitate the healing process. Imagery provides relief through relaxation, distraction and producing an image of the pain. Imagery can also empower patients/clients to take some control over their pain.

Imagery can be used in a guided way with children and is usually described as guided therapeutic imagery. The child imagines something about their pain that will help to reduce it, e.g. their pain flowing out of their bodies.

Massage

Massage may modify the pain experience by stimulating the nerve fibres responsible for inhibiting pain perception by closing the gate and potentially stimulating endorphin production. The relief obtained by rubbing an area after a minor knock demonstrates this.

Where possible, the patient/client/parents should be involved in the decision-making process and appropriate permission should be sought. Using massage involves a level of physical contact that is an essential element of the therapy. Massage can provide carers with a useful role and make them feel that they are contributing something positive to the experience, e.g. the carer or relative can massage their loved one’s back and shoulders. Older adults especially may be deprived of physical contact and massage can have a dual effect of contact with another human being and lead to relaxation.

Massage provides healing and relaxes tightly contracted muscles that may result from pain-induced stress. There-fore, massage can lead to relaxation and provide renewed energy needed for coping strategies.

Therapeutic touch

Touch is a means of communication (see Ch. 9). It is normally a two-way process involving feelings and sensation, and indicates a caring or loving relationship; on the other hand, touch used therapeutically aims to aid healing.

Therapeutic touch is a non-invasive means by which the nurse can help to manage a person’s pain. This is particularly important for certain groups such as children, people with mental distress or those with a learning disability. Some patients in hospital are deprived of therapeutic touch even though they are exposed to high levels of touch, especially in relation to observations and technical procedures (Box 23.26). In fact parents, especially those of children who are severely ill, touch their children more than the nursing staff.

Acupuncture (see Ch. 10)

Acupuncture aims to treat the person and not the disease or the symptoms. Using acupuncture for the treatment of painful conditions is based upon a greater understanding of physiological mechanisms involved in the pain transmission and modulation (Henderson 2002). There is also some evidence to suggest that acupuncture encourages the production of endorphins (see pp. 656, 658, 659).

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation

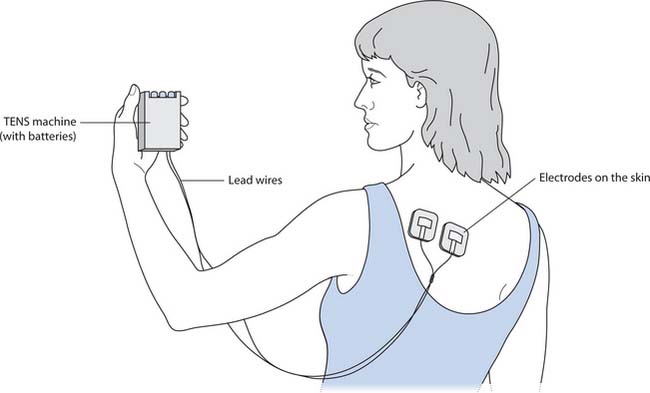

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) is useful in localized pain and is thought to increase endorphin levels and act as a counterirritant. Ideally TENS should be used in combination with other treatments. The non-invasive device delivers controlled low-voltage electricity to the body via electrodes placed on the skin (Fig. 23.11). People using TENS often describe a tingling sensation when the device is active. It is useful for both acute and chronic pain and is used in labour (Box 23.27).

Non-pharmacological pain relief during labour

Women may choose to use TENS or other non-pharmacological methods as part of the management of labour pain.

In chronic pain management TENS provides a modality with fewer side-effects than other treatments and is attractive because it is controlled by the patient and does not limit mobility. However, some people may be unable to tolerate the electrodes on their skin.

Aromatherapy (see Ch. 10)

Aromatherapy is a holistic form of healing using essential oils extracted from aromatic plants. The oils can be used in massage, in the bath, through inhalation and compresses. Aromatherapy massage can offer several ways of reducing the experience of pain, e.g. by acting on the ‘pain gate’ mechanism, positively affecting the cognitive control mechanisms and by the release of endorphins. Aromatherapy is frequently used to reduce stress, promote relaxation, treat symptoms and relieve pain.

Aromatherapy must only be practised by trained practitioners, although once the oils have been made safe into an effective blend patients/clients/parents can use them as prescribed by the therapist. However, nurses must consult local guidelines and polices before using essential oils.

Surgical intervention

Sometimes this is necessary for intractable pain. Surgical interventions include:

These interventions are only used when other pain control methods have proved unsuccessful and usually fall within the remit of the specialist pain clinic.

| Bandolier – The Oxford Pain Internet Site | www.jr2.ox.ac.uk/bandolier/booth/painpag/index2.html |

| Available July 2006 | |

| British National Formulary | www.bnf.org.uk |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Cancerbackup | www.cancerbackup.org.uk |

| Available July 2006 | |

| National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence | www.nice.org.uk |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Pain site | www.pain-talk.co.uk |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Scottish Intercollegiate | www.sign.ac.uk |

| Guidelines Network | Available July 2006 |

| The British Pain Society | www.britishpainsociety.org |

| Available July 2006 |

Baker C, Wong D. QUESTT: a process of pain assessment in children. Orthopaedic Nurse. 1987;6(1):9-11.

Broadbent C. The pharmacology of acute pain. Nursing Times. 2000;96(26):39-41.

Brooker C, Nicol M, editors. Nursing adults. The practice of caring. Edinburgh: Mosby, 2003.

Bruster S, Jarman B, Bosanquet N, et al. National survey of hospital patients. British Medical Journal. 1994;309:1542-1549.

Carr E, Mann E. Pain: creative approaches to effective management. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 2000.

Carter B. Child and infant pain. Principles of nursing care and management. London: Chapman & Hall, 1994.

Davies K, Taylor A. Pain. In: Brooker C, Nicol M, editors. Nursing adults. The practice of caring. Edinburgh: Mosby, 2003.

Department of Health. 2006 Non-Medical Prescribing Programme. Online: http://www.dh.gov.uk/PolicyandGuidance. Available September 2006

Elliot A, Smith B, Penny K, et al. The epidemiology of chronic pain in the community. Lancet. 1999;354:1248-1252.

Greenstein B, Gould D. Trounce’s clinical pharmacology for nurses, 17th edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2004.

Henderson H. Acupuncture evidence base for its use in low back pain. British Journal of Nursing. 2002;11(21):1395-1403.

Horn S, Munafo M. Pain theory, research and intervention. Buckingham: Open University Press, 1997.

Human Rights Act. 1998 TSO, London. Online: www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/acts1998/19980042.htm.

Mann E. Chronic pain and opioids: dispelling myths and exploring the facts. Professional Nurse. 2003;18(7):408-411.

McCaffery M. Nursing approaches to nonpharmacological pain control. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 1990;27(1):1-5.

McCaffery M, Pasero C. Pain clinical manual, 2nd edn. St Louis: Mosby, 1999.

Melzack R, Katz J. Measurement in persons in pain. In Wall P, Melzack R, editors: Textbook of pain, 3rd edn, Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1994.

Melzack R, Wall P. Pain mechanisms: a new theory. Science. 1965;150:971-979.

Merskey H, Bogduk N, editors. Classification of chronic pain: descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms. Report by the International Association for the Study of Pain, 2nd edn. Seattle: IASP Press, 1994.

Moore A, Edwards J, Barden J, McQuay H. League table of analgesia in acute pain. In: Bandoliers little book of pain. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Morley S, Eccleston C, Williams A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of cognitive behavior therapy and behavior therapy for chronic pain in adults excluding headache. Pain. 1999;80:1-13.

Nursing and Midwifery Council. The NMC code of professional conduct: standards for conduct, performance and ethics. London: NMC, 2004.

Paz S, Seymour J. Pain theories, evaluation and management. In: Payne S, Seymour J, Ingleton C, editors. Palliative care nursing. New York: Open University Press, 2004.

Piaget J. Judgement and reasoning in the child. London: Routledge, 1924.

Rutishauser S. Physiology and anatomy. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1994.

Sarafino E. Health psychology, 4th edn. New York: Wiley, 2002.

Schofield P. Snoezelen. Its potential for people with chronic pain. Complementary Therapies in Nursing and Midwifery. 1996;2(1):9-12.

Twycross A, Moriarty A, Betts T. Paediatric pain management a multidisciplinary approach. Oxon: Radcliffe Medical Press, 1998.

World Health Organization. 2005 Pain ladder. Online: www.who.int/cancer/palliative/painladder/en.

Zborowski M. Cultural components of pain. Journal of Sociological Issues. 1952;8:16-30.