Chapter 11 Stress, anxiety and coping

Introduction

The word ‘stress’ was originally used by Selye (1956) to describe the ‘pressure’ experienced by a person in response to life demands. These demands are referred to as ‘stressors’ and include a range of life events, physical factors (e.g. cold, hunger, haemorrhage, pain), environmental conditions and personal thoughts.

Stress is a reactive state to demands or potential demands made on the adaptive capacities of the mind and body.It is not necessarily unhealthy, as without stress people would have little motivation to act and could not feel the pleasure of achievement. In many ways stress should be considered a useful and necessary reaction in that, not only does it motivate action, it also prepares the person to take this action. Selye used the term ‘eustress’ to describe some of the more useful and adaptive forms of stress which enhanced a person’s well-being.

However, if people lack the capacity to deal with the demands made upon them, their coping resources may be overwhelmed. In situations in which a person constantly feels under pressure with little respite, or when people experience severe trauma, the adaptive effects of stress can become harmful and may damage health. To describe these types of stressors Selye used the term ‘distress’.

The first part of the chapter provides a framework for understanding the causes and effects of stress and anxiety and how these can be used to understand the potential effects on health. These ideas are developed to show how nurses, working in every setting, can apply this knowledge and the associated skills to managing their own stress and to reduce the negative effects of stress on their patients/clients/carers.

Nature of stress

People tend to associate both stress and anxiety with negative effects on health. The media frequently link work stress with health problems, e.g. heart disease, and it is easy for people to make the association between stress and mental illness. Likewise, anxiety is almost always used to refer to an abnormal state rather than a common reactive response. Both stress and anxiety do generate unpleasant feelings and can lead to problem behaviours, but people have feelings for a reason, they have a function. Even when the effects of stress and anxiety seem maladaptive, e.g. difficulty with decision-making, they can usually be explained and understood.

A good place to start in understanding stress is to think about how it may function in shaping and directing our own lives (Box 11.1).

A typical day at university

Identify a typical day at the university and recall the things you did during the day. Include getting up, the journey, study periods and break times.

Student activities

Identifying why you did these things can be difficult; you need to consider your motivation. For example, if you are successful and become a nurse you will be able to earn a living, in a job, which you (hopefully) like and which is valued by others. If you do not attend or study you risk criticism and failure. It is the demands created by the need to succeed and avoid disapproval that motivate people to act, and the anticipation of success can be linked to excitement, pride and pleasure.

It is important to emphasize how central stress is to life; it is perhaps the main reason people do anything. The feelings associated with stress put pressure on people to act. Taking this idea further, it could also be argued that without successful stress management, there would be less pleasure in living.

Understanding emotion

Stress and anxiety are specific emotional states, with four main elements:

All of these elements interact; changes in one will affect other elements within an integrated system. Emotions provide an ideal example of how the mind and body interact.

Common causes of stress and anxiety

Identifying specific causes of stress is difficult because people, just in the process of living, constantly have to adapt to changes and deal with demands. People always have multiple stressors acting upon them at any one time. A common finding is that the events remembered most clearly are typically those associated with feelings.

Feeling irritated, interested, entertained, anxious and happy can all be considered as potential stressors. The fact that these feelings influence memory and make recall easier is a good example of how affect and cognition interact and influence each other.

In anxiety, a fear-like emotion, it is usually easier to identify specific causes because of the perceived threat. There also seem to be specific types of anxiety responses depending on the nature of the threat (Box 11.2).

Box 11.2 The emotional effects of specific threats

Fear is considered to be the basic reactive emotion leading to the typical ‘fight or flight’ response and is usually initiated by automatic systems. Anxiety, however, almost inevitably involves conscious judgements or appraisals about situations (see Box 11.2).

Common themes in understanding what causes stress

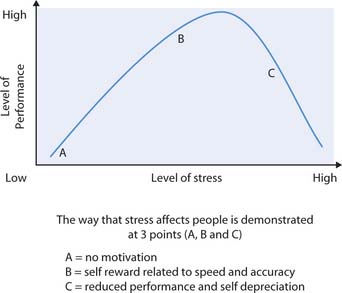

Despite the difficulties in identifying individual stressors there are some common themes that can be identified as causing most people some stress. People need some stimuli to keep them active and motivated. However, the ability to deal with stress differs between individuals and at a certain point coping resources can fail and performance becomes impaired. There appears to be an optimum level of arousal in which eustress is associated with staying in this optimum range and distress occurs when the stress falls outside the range (Fig. 11.1).

In this model, the arousal (heightened activity including cognitive, affective, physiological and behavioural changes) associated with stress produces the competitive edge; arousal speeds thought processes and quickens reaction. Indeed, when demands are made upon an individual, the increased arousal improves both physical and cognitive abilities in order to meet these demands. However, under- or overarousal is associated with a reduced ability to function effectively.

Change

Change is any event that requires an individual to adapt to an altered situation. Adaptation describes the changes in physiology, cognition and behaviour in response to changes in the environment. Holmes and Rahe (1967) identified a number of life changes and produced a frequently used scale to measure social readjustment. The Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS) allows a person to identify recent life events; a score is allocated to each and totalled to give an overall score (Table 11.1). People who had experienced high-scoring events in the previous year were significantly more likely to become physically ill in the following year than those with low scores. It is important to remember that even events seen as positive still require adaptation and are included as stressors.

Table 11.1 Social readjustment rating scale (adapted from Holmes & Rahe 1967)

| Rank | Life events | Life change unit |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Death of partner | 100 |

| 2 | Divorce | 73 |

| 3 | Marital separation | 65 |

| 4 | Imprisonment | 65 |

| 5 | Death of close family member | 63 |

| 6 | Illness requiring hospital admission | 53 |

| 7 | Marriage | 50 |

| 8 | Dismissal from work | 47 |

| 9 | Marital reconciliation | 45 |

| 10 | Retirement | 45 |

| 11 | Change in health of close family member | 44 |

| 12 | Pregnancy | 40 |

| 13 | Sexual difficulties | 39 |

| 14 | Gaining a new family member | 39 |

| 15 | Employment changes | 39 |

| 16 | Change in financial state | 38 |

| 17 | Death of a close friend | 37 |

| 18 | Change to a different line of work | 36 |

| 19 | Major arguments with spouse | 35 |

| 20 | Major long-term financial commitment of more than £10000 | 31 |

| 21 | Bankruptcy | 30 |

| 22 | Change in responsibility in work | 29 |

| 23 | Son or daughter leaving home | 29 |

| 24 | Major family disagreements | 29 |

| 25 | Outstanding personal achievement | 28 |

| 26 | Spouse begins or stops work | 26 |

| 27 | Moving house | 25 |

| 28 | Change in personal habits | 24 |

| 29 | Trouble with authority figures in work | 23 |

| 30 | Change in work hours or conditions | 20 |

| 31 | Change in school | 20 |

| 32 | Change in recreation | 19 |

| 33 | Change in faith activities | 19 |

| 34 | Change in social activities | 18 |

| 35 | Debts or loan of less than £10000 | 17 |

| 36 | Change in sleeping habits | 16 |

| 37 | Change in eating habits | 15 |

| 38 | Holidays | 13 |

| 39 | Christmas | 12 |

| 40 | Minor violation of law (e.g. speeding ticket) | 11 |

| TOTAL SCORE | ||

Note: Scores over 300 in one year indicate an increased risk of stress-related problems and scores less than 150 indicate a low risk.

Hassles

Lazarus (1981) identified two stress measurements:

While people find it easy to identify specific stressful situations, in reality it is ongoing problems of life that are the really significant causes of stress-related health problems (Box 11.3).

Everyday stresses

Think about the ongoing problems of life that cause stress and stress-related health problems. For example, being a long-term carer, reliance on public transport, stressful work, etc.

Stress can be seen as frustration when things do not turn out as planned; a positive slant is for individuals to view these as ‘stumbling blocks’.

People

In social situations people are always aware of others and conscious of the impression they may be making; when there is uncertainty about others’ evaluations they feel self-conscious and anxious. In the same way, the availability of social support is an important protector against the negative effects of stress (Box 11.4).

Reasons for living

Try to answer the following questions:

Thinking about these questions can help clarify how important social relationships and shared beliefs are.

Interpersonal issues are extremely important; the need for acceptance and approval is so powerful it can override even survival needs. People need to feel life has value and meaning. The sense of meaning derives from other people. People appear to devote a great deal of their cognitive resources to dealing with interpersonal issues, which may also be a reflection of, or supported by, some specific inherited elements.

Mediators and the stress response

A number of more general issues also affect the nature and intensity of the stress response. Individual responses to stress and anxiety have both inherited and acquired elements, which interact within the situational context. People clearly differ in a whole range of ways in respect to personality, autonomic reactivity, physical strength, dexterity and intelligence, all of which may affect the stress response. Humans may have certain predispositions that influence stress responses such as learning and remembering. Previous experience is extremely important in moderating a person’s reaction to stressors.

In addition, a number of features of the stressful events will influence the responses. These include:

The amount of control that a person feels they have over events is also important.

The role of the unconscious

Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) suggested that a person’s internal mental world was dominated by primitive, often socially and personally unacceptable, drives. In order to protect self-esteem and mental health these drives were kept out of awareness, in the part of the mind he called the unconscious. However, even though these unacceptable drives were unconscious they did continue to exert ‘pressure’ to come into conscious awareness and be acted upon.

In a similar way the memories of certain emotionally painful early experiences could also be kept out of awareness to defend the conscious mind from the associated pain. To manage the threat of unacceptable memories or impulses coming into consciousness, Freud suggested that people deploy a range of mental strategies he called defence mechanisms (Box 11.5 and Ch. 8). Defence mechanisms function by distorting a person’s view of reality, but even so, Freud considered them to have an important role in protecting a person from psychic pain. While defences can be functional and useful in protecting people from anxiety, Freud also recognized that this protection sometimes came at a very high cost to the individual.

More recent work has emphasized how certain events or experiences, e.g. the experience of illness, activate some of the more primitive unconscious fears that everyone has.

A seminal paper by Menzies-Lyth (1959) also identified a number of ways that organizational and social structures can evolve to support an individual’s defences. For nurses, these operate as depersonalization (a way of thinking about patients/clients that diminishes their basic humanity and identity). When a nurse relates to a patient/client as an individual the patient’s/client’s pain and distress can also be very distressing for the nurse to deal with. It is often suggested that nurses should avoid emotional involvement, which in a similar way diminishes or denies the nurse’s basic humanity. There is always some level of involvement for the nurse and finding appropriate ways of managing this can enhance the experiences and rewards of being a nurse. However, during periods of high work-related stress there is a tendency to reduce patient-related stress by minimizing the patient’s individual distinctiveness, so instead of using names the patient may be referred to by diagnosis or bed/room number.

There can also be a tendency to make moral judgements, that some patients/clients are more deserving of care than others. Patients/clients who engage in behaviours that are disapproved of may be excluded from good healthcare or treated badly. These groups include people who self-injure, smoke or those who do not cooperate with treatment. Because some types of behaviour would be seen as unethical or even abusive, it is only through using defences such as depersonalization, detachment and denial that nurses can continue to act professionally in ways that do not reflect their personal values.

One interesting example of this sort of defence may be found in the use of the obsolete term ‘psychosomatic’ to describe an illness. The assumption was that psychosomatic conditions were caused by, or aggravated by, stress and anxiety, i.e. ‘all in the mind’. Nurses invest a great deal of their self-esteem into their ability to help to treat illness. In addition to helping the patients/clients, this also helps to control the nurse’s own anxieties in the face of illness and death. A problem arises when, despite the nurse’s best efforts, patients/clients do not get better. This can be seen as a personal failure and a way of dealing with it is to blame the patient/client for the nurse’s lack of effectiveness – it is ‘all in their mind’ and therefore their responsibility.

Identifying stressors

An important function of the development of nursing knowledge is that it allows nurses to predict and manage potential problems that may arise. Nurses need to adopt a holistic approach in an assessment to identify stressors, which includes consideration of the following influences:

Stressors in healthcare rarely affect just the patient/client. They affect relatives, friends and of course nurses involved in their care. The way in which a person behaves in response to the stress will have a significant effect on their future. People often feel angry and irritable when stressed and if this results in aggressive behaviour, they might alienate the people that they rely upon for care and support, thus increasing future stress.

Box 11.6 (see p. 282) considers a range of potential stressors that may impact on specific care situations.

Identifying stressors

The stress response

The term stress response describes the adaptive physiological changes that take place to enhance a person’s ability to deal with demanding or dangerous situations. While the adaptive changes are occurring in response to the stress situation, the internal environment, e.g. blood chemistry, must be maintained within a normal range for optimum cell function. This ability to maintain the internal environment within the normal range is known as homeo-stasis. Allostatic load refers to the cumulative cost to the body of maintaining homeostasis while responding to stressors; when these resources are overloaded then there is a serious risk to health.

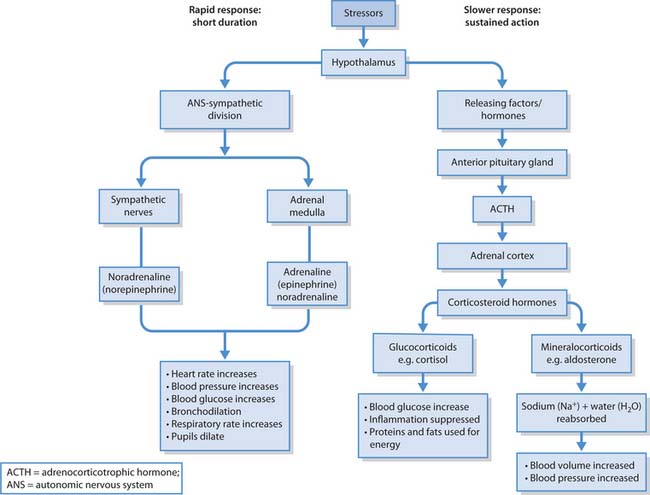

When the potential need for increased mental and phys-ical activity is established, the physiological responses that occur are regulated by two interdependent control systems:

The ANS is divided into the sympathetic and the para-sympathetic divisions, but while periods of stress and anxiety lead to a general stimulation of the nervous system it is the effects of the sympathetic division that predominate.

The sympathetic division is responsible for mobilizing the body’s resources in response to stress by releasing the neurotransmitter noradrenaline (norepinephrine) at the effector organs. The adrenal medulla (middle part of the adrenal glands) is also stimulated to release adrenaline (epinephrine) and noradrenaline into the bloodstream. Noradrenaline and adrenaline are related catecholamines, which cause effects that include the ‘fight or flight’ response of increased heart and respiratory rates, blood pressure, etc.

Releasing factors/hormones from the hypothalamus in the brain stimulate the pituitary gland, which regul-ates other endocrine structures. Pituitary hormones, e.g. adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH), stimulate the release of corticosteroid hormones from the adrenal cortex (outer part of the adrenal glands). Corticosteroid hormones – known as glucocorticoids, e.g. cortisol – increase the availability of the body’s energy resources, alter immune responses and generally prepare the body for action and potential injury. Other corticosteroids – known as mineralocorticoids, e.g. aldosterone – influence sodium and water retention.

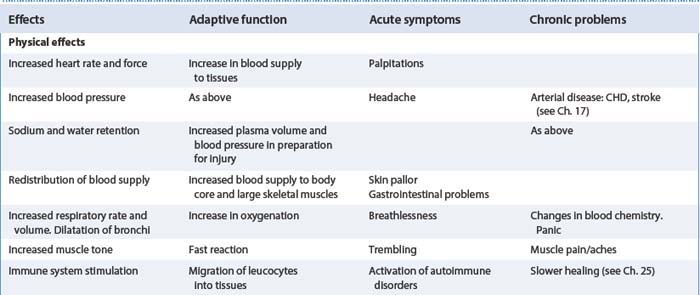

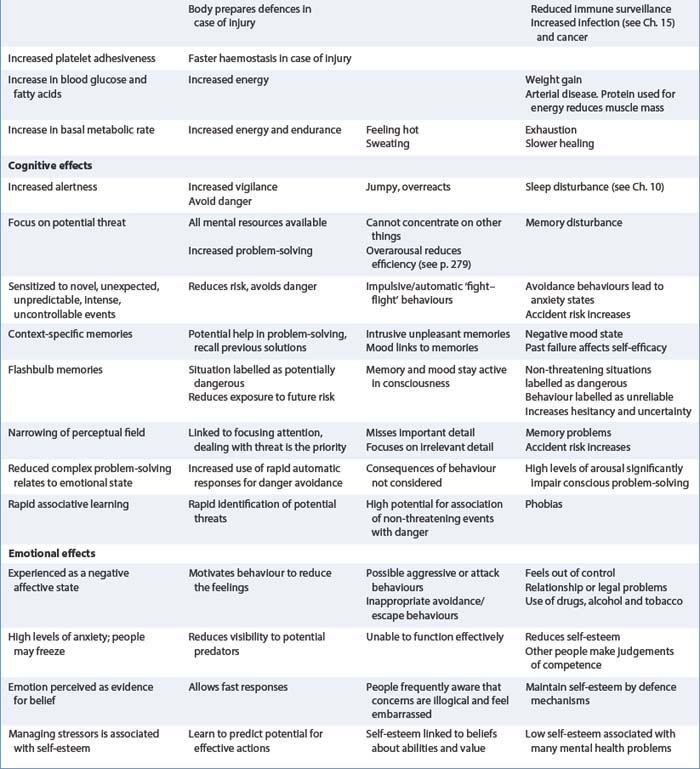

Corticosteroids are involved in chronic long-term stress and also influence mood and behaviour. Table 11.2 outlines some examples of the effects of the stress response, their adaptive function and the potential impact on health.

To summarize, the sympathetic nervous system and endocrine system coordinate a response that increases available energy, endurance and pain tolerance and enhances the ability to survive injury. However, as this increased state of arousal is often uncomfortable and is costly in terms of resources, there may be negative health effects associated with both acute short-term stress and chronic long-term stress. In acute states the most significant problems are often due to behavioural changes, whereas the physiological changes occurring in chronic stress appear to increase vulnerability to a range of disorders.

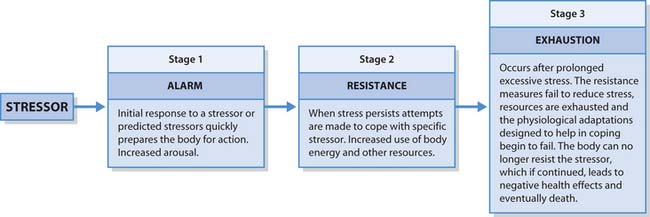

Selye (1956) described the stress response as being triphasic or having three stages: an alarm stage, a resistance stage and an exhaustion stage (Fig. 11.3, p. 285). Selye’s model – the General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS) – was the first real attempt to develop a general theory of stress and clarify the role of stress in health and illness. However, the model focused on the underpinning physiology and failed to adequately address psychological and social factors. Despite these problems the model has been highly influential in stress research.

Stress-related health problems

A general view of the effects of both stress and anxiety is that they evolved to influence physiology, cognition, affect and behaviour in order to increase the chances of surviving in difficult and dangerous environments. However, life has changed and the evolved mechanisms are less useful in dealing with the more complex and enduring stress associated with modern life. Stress depletes physical and mental resources while reducing control of behaviour.

Chronic stress in particular is strongly associated with a wide range of health problems because of physiological and psychological ‘wear and tear’ and inefficient use of energy. This may be associated with behavioural changes that increase other risks and reduce an individual’s ability to deal with new challenges.

In someone with a pre-existing vulnerability, exposure to increased stress may be the stimulus to trigger illness; it may then influence recovery and other health-related behaviours. Those with existing conditions may experience a worsening of symptoms, e.g. anginal pain (see Ch. 17) or increased frequency of migraine attacks.

Sociocultural, psychological and biological variables can combine to produce a range of disorders. The interaction between these factors is now widely accepted as the only way to make sense of body functioning. Increasingly, the immune system is becoming the focus for understanding the relationship between stress and illness; this area of study is called psychoneuroimmunology.

Managing stress and anxiety

This part of the chapter outlines the general principles and methods that individuals may use in managing stress and anxiety.

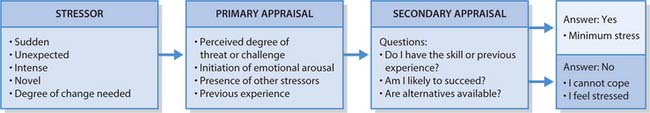

The huge variation in the ways that stress presents and the ways it might affect the person mean that a range of techniques need to be considered. The main reason for this variation is attributable to the fact that, after an initial, often automatic reaction to a situation (primary appraisal), people make a series of judgements which will largely control the responses (secondary appraisal).

While recognizing the role of physiology, Lazarus and Folkman (1984) suggested that an individual’s previous learning and experience significantly affect the way in which they react to life events; others can look at the same event and come up with differing interpretations. In this view of stress and anxiety it is not the stimulus itself that is problematic, it is the individual’s appraisal of the stimulus and their belief about their ability to manage its effect (Fig. 11.4).

This model emphasizes cognition. Judgements are made about the stressor and about the person’s ability to change their behaviour or thoughts in such a way as to master or reduce the effects of the stressor. These responses are coping strategies, which may be adaptive (as in managing the event without increasing other problems) or maladaptive (in which the coping strategies might fail or increase stress). This framework is particularly important in understanding many of the principles of stress management.

Everyone uses ways of minimizing stress and improving rest and relaxation (see Ch. 10), such as socializing, reading, listening to music, holidays, etc.

The reaction to stressors/threats and other ongoing actions that people engage in are attempts to manage or modify the stressful situation or the feelings generated by it. While these responses are highly individual they can be categorized into some basic types of coping.

Avoidance

Avoidance commonly involves reducing exposure to stimuli that cause stress or anxiety, attempts to ignore the demands/threats or attempts to suppress the negative feelings. Avoidance is a very common reaction to threat when often the first reaction is to escape, thus avoiding further exposure. To ignore stressors people might engage in distracting tasks, use defence mechanisms (see pp. 280–281) or simply refuse to recognize the importance of the stimulus. People might try to induce positive feelings, e.g. by comfort eating, treating themselves or using stimulant (usually illegal) drugs, sedatives or alcohol.

People frequently resort to sedating drugs and alcohol to help manage the unpleasant feelings associated with stress and anxiety. They might attempt to ‘drown out’ overwhelming feelings associated with severe trauma, loss or threat by using a sufficiently high dose to induce insensibility.

Anxiolytic drugs, e.g. diazepam, can be used in similar ways during short episodes of intense anxiety or distress but, like alcohol, continued use over long periods is associated with a range of health and interpersonal problems.

Sedation does not address any of the causes or problems faced by people and while they might allow a person to cope with an acute and intense trauma they have no place in long-term management. Continued use is associated with a reduction in effective functioning and an increased risk of dependence.

Currently the role of medical intervention in responding to the normal effects of life events as illnesses to be treated is hotly debated; health staff seem motivated to attempt to remove all types of distress a person might experience. However, chronic stress and anxiety are strongly associated with problems that are considered to be diagnosable illness, depression being very common. Currently the main interventions are based on using antidepressant drugs, e.g. fluoxetine, as improving mood will improve coping.

Dealing with the stressor

The most direct approach to dealing with demands is to take action to meet those demands. This approach is often the most adaptive, particularly for low-level stressors when people can use problem-solving and evaluate the potential consequences of their actions. When the stress experienced is associated with very high levels of arousal, problem-solving is impaired and actions may not be well considered.

Among the most effective and easiest interventions nurses can use to reduce anxiety and stress is to provide useful and understandable information (see Chs 9, 23, 24). Patients/clients should know what to expect in relation to illness, recovery and specific interventions. This is important in allowing the person and their family to prepare themselves and recognize the difference between normal and abnormal sensations – without information every unusual sensation causes anxiety. Nurses may need to adapt information or ways of communicating, and seek help from family and carers when clients find it difficult to understand what is happening to them, e.g. a person with a learning disability or a person with dementia.

To deal successfully with a range of demands people learn and use a series of skills. When demands and expec-tations are predictable, learning useful skills can be structured and planned (Box 11.7).

Dealing with stressors

A student nurse may feel anxious about doing something for the first time, e.g. giving an injection. Preparatory information can reduce anxiety and frequent practice with supervision allows the nurse to feel sufficiently confident that eventually little or no anxiety is experienced.

When people feel confident in their abilities to control and meet demands, little stress is experienced and successful outcomes become more likely. People often experience positive feelings of achievement when they manage challenging situations and their beliefs about their coping abilities are enhanced. Assertion training by increasing skills in negotiation and relating to others may enhance this perception of control.

Explaining that anxiety is a normal response to many situations is also a useful way of giving people ‘permission’to talk about anxieties. Again the nurse must be imaginative in finding ways to help people with learning disabilities or dementia to express/communicate their anxieties.

Imposing structure

In situations that involve multiple and complex stressors the ability to prioritize is important. This could involve making ‘to do’ lists, prioritizing demands in order of importance and managing the time available to deal with the demands. The principle here is a simple one: for life to be manageable, it needs to be managed (Box 11.8).

Time management

Using a diary to note important events, e.g. appointments, submission dates, and keeping track of arrangements is the most effective way of controlling the demands made on time. A diary allows the person to consider the practicalities of accepting extra commitments and to prioritize how much time to devote to each issue. This allows realistic judgements to be made about how many issues can be addressed in the given time.

The diary is only a tool; the person needs to be able to use the information in negotiating their commitments with others and must be prepared to say no when necessary. These ideas help people to deal with stressors in which direct action is appropriate and likely to be useful.

Controlling the emotion

Strategies are principally about changing appraisals about the situation. This could involve reassessing the importance of an event and reassessing personal ability to cope with the perceived demands. People may deliberately remind themselves of past successes in managing similar events or make positive statements about their coping abilities. Improving self-awareness helps people recognize the stressors that appear particularly import-ant to them and to recognize the effects of stress early, allowing them to address the situation before the feelings become overwhelming.

Most current research supports the view that it is people’s beliefs about the situation and their abilities to cope that control emotional reactions. Changing these beliefs can therefore alter the meaning of the situation and the responses to it. Unfortunately, the underpinning beliefs that inform the way in which people appraise threats or demands lead to habitual and automatic responses based on previous experience. Thus many people are basically unaware of why they feel like they do and as a consequence do not check the accuracy of their beliefs.

The cognitive therapies provide frameworks to help people understand these principles and techniques for re-evaluating belief systems. This involves helping individuals recognize that it is not the event that causes distress, but their beliefs about the event that lead to the emotional consequences. These beliefs then need to be made explicit and logically examined; examining the evidence for and against beliefs is the basis for disputing their validity. When individuals adopt these methods and use them continuously it is suggested that responses become more grounded in reality, rational and more likely to lead to effective management.

Ellis (1994), who developed a cognitive approach called Rational Emotive Therapy, suggests that people evaluate situations by using simple exclamatory statements about the event. Characteristically, they first make an evaluation of the event, which is sensible and rational, followed by an irrational statement about its meaning. It is the irrational statements which have little or no supporting evidence that cause the emotional reaction. Moreover, people tended to have generalized, irrational beliefs that add to stress interpretations (Box 11.9).

Table 11.3 outlines the sequence of events in creating distress and an example of ways in which people can challenge these beliefs and therefore change the feelings.

Table 11.3 Example of cognitive sequencing

| Stage | Example |

|---|---|

| A= Activating event – actual or inferred, current or predicted | Student has to present course work to peers and lecturers |

| B= Beliefs – often in the form of rigid and unqualified demands in the form of ‘musts’, ‘shoulds’ and ‘oughts’ | Rational appraisal: |

| Appraisals are often automatic and habitual – people need to learn how to identify them | Irrational appraisal: |

| D= Disputing the disturbance-producing appraisals. Subjecting beliefs to rational evaluation. Questioning the evidence for the belief | |

People need to identify the beliefs that cause problems and then learn to challenge them. A useful strategy is to note the events/situations which cause stress and then try to identify why they are important. As in the example, this leads to a change from thinking the event controls the feelings to recognition that it is their own beliefs and appraisals that are important. Only then can they start to evaluate their beliefs by examining the evidence on which they are based.

Enhancing coping resources

A wide range of strategies can be used to enhance coping, including:

Relaxation techniques

Over the centuries in a wide range of cultures and under various guises, the ability to relax the body and mind has been seen as an important skill, particularly for those who had to problem-solve and make effective decisions.

If an individual can reduce emotional arousal and focus their thoughts onto problem-solving, then they would be able to more clearly analyse the situations and generate solutions.

The techniques are widely used in healthcare, e.g. pain management (see Ch. 23), insomnia (see Ch. 10), even though the underpinning evidence is inconclusive. However, the feelings induced by effective relaxation techniques are usually perceived by clients as pleasant and restful and there is little evidence of side-effects or safety concerns. Using relaxation becomes more effect-ive with regular practice.

Although there are considerable differences between individual relaxation techniques there does appear to be some common themes. These usually include:

Box 11.10 describes one relaxation technique but for more information about other techniques such as imagery, see Further reading suggestions (e.g. Payne 2005). These techniques can be used to help patients/clients or for personal stress management; generally they tend to be most appropriate in situations where direct action or problem-solving is unlikely to be helpful.

Box 11.10 A relaxation technique – the parasympathetic flop

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) therapies

The role of CAM therapies in healthcare is discussed in more detail in Chapter 10. However, it is important to remember that some of these therapies are linked to particular faiths and will not be acceptable to all groups. There can also be ethical concerns about using methods that do not have an evidence base of research about safety and efficacy.

On the other hand, inducing relaxation is perhaps the one area in which many CAM therapies have shown considerable promise. Meditation, massage, reflexology, yoga and ti chi exercises can all be useful in helping a person manage the effects of stress. Massage techniquesare particularly useful in children and in individuals with sensory impairment; the fact that they may reduce pain might also reduce the impact of pain as a stressor.

Ability to tolerate stress

Despite the wish for a predictable controllable life, everyone is faced with periods of uncertainty and feelings of helplessness in dealing with the problems of living and indeed dying. There are techniques such as the AWARE technique that people can use to improve stress tolerance. The person is encouraged to:

The role of the nurse

The publication of Our Healthier Nation (DH 1998) marked a change in the philosophy of healthcare provided within the NHS. For the first time there was explicit policy direction for a service that previously had focused on treating illness to begin to focus on improving health and preventing illness. The broad and pervasive effects of stress on health, illness and recovery mean that stress management is a key theme in health promotion. Nurses in many diverse settings are often ideally placed to educate patients/clients about the nature and effects of stress. This in itself is a powerful intervention; people commonly misinterpret the effects of stress and anxiety as indicators of serious illness, increasing their anxiety still further.

Nurses can also offer advice or self-help materials to individuals in order to enhance coping skills. Holistic nursing assessment of the healthcare needs of both individuals and of specific groups should include the identification of stressors and current coping strategies used, thus allowing the nurse to offer pragmatic and practical actions that their patients/clients will find useful. The nurse in helping the patient/client to clarify the causes and effects of stress can identify the management strategies most likely to help.

A wide range of health promotion activities can influence stress and coping indirectly – information about health and illness can increase the person’s sense of control. In a similar way, interventions designed to promote healthy living such as exercise advice contribute to ‘wellness’ and increase resistance to the adverse effects of stress.

Stress and people

This part of the chapter describes the more specific aspects of stress that relate to nurses and nursing. This includes work-related stress, which is extremely important in healthcare settings. Stress affecting patients/clients and their carers is addressed with suggested interventions for reducing its adverse effects. In many instances the more general information on causes, effects and interventions can be used to inform the nurse’s actions, both in self-care and the care of others.

Stress and nursing

The Health and Safety Executive (2002) estimated that around 500000 people in the UK were experiencing work-related stress at a level that was making them ill. They also identified that approximately 5 million workers claimed to be stressed or highly stressed in their workplace.

The type of the work that nurses undertake would suggest that it has the potential to be particularly stressful. This is borne out by research that suggests levels of occupational stress to be higher in the NHS than in similar professions. Borrill et al (1996) surveyed over 11000 NHS staff and found that more than 28% of nurses suffered at least minor mental health problems (typically anxiety and depression) compared to about 18% of the general employed population.

This can be particularly problematic in areas of staff shortages. Harris (2001) observed that ‘Health care professionals experiencing high levels of occupational stress can lead to illness, increased absenteeism, high staff turnover, unsafe behaviour and increased accident rates’ (see ‘Burnout’, p. 290).

Employers have a statutory responsibility to provide a working environment in which hazards to health have been identified and actions taken to control exposure to these hazards. Stress has been identified as one such hazard that should be subject to the risk management process (see Ch. 13).

In addition to the increased rate of change, nursing has some features that might account for the high levels of reported stress. One important feature is that nursing is fundamentally an interpersonal activity – nurses deal with people. Many of these encounters are with strangers and in situations that are already emotionally charged where patients/clients and their families are frequently anxious, angry or distressed.

In order to understand the potential for stress it is important to realize that while most nurses would identify angry or aggressive patients/clients as causing stress there are other less obvious issues to consider. These include:

These issues are common to many areas of nursing and often have an emotional impact on the nurses involved in providing care (Box 11.11, p. 290).

Nurses and stress

Identify a patient/client from a clinical placement who caused you to feel uncomfortable or stressed.

There are also significant stressors that arise from the working environment. Those commonly identified by trained nurses include:

Whereas student nurses frequently have other concerns, some feel that their role is poorly defined, they change work areas frequently and need to balance practice with working on assignments.

The effects of this stress can manifest in both physical and emotional forms. These forms can be seen in physiological changes and in positive and negative adaptive behaviours.

In the right environment, stress can be highly motivating, with the nurse perceiving the stressors as a challenge, which brings excitement and a sense of achievement and reward. Other less useful ways of coping involve attempts to reduce exposure to further stress by disengaging from emotional aspects of their work; this is commonly seen in the stress-related state of ‘burnout’.

Burnout

It is no surprise that some individuals working in high stress environments, particularly if combined with significant external stress and poor levels of support, can begin to feels powerless to contribute effectively at work. This failure of coping resources in the work environment is often referred to as burnout.

Many nurses start training with high hopes and expectations; indeed many people still consider it to be a vocation in which helping others becomes the person’s primary goal in life. While humanity should be thankful that such people exist, they often set themselves unrealistically high goals and expectations, dramatically increasing their risk of experiencing burnout.

There is no general definition of burnout but Maslach et al (1996) suggest that it is a syndrome characterized by:

Physical symptoms are common and are similar to anxiety:

Experienced over time, the negative effects on performance and relationships can increase the stress and burnout may become associated with more generalized anxiety and depression.

Burnout tends to develop and worsen over time. It commonly starts with feelings that initial expectations are not being met, disillusionment and disappointment. These vague feelings might lead to harder work to attempt to change the situation; if this fails the energy gives way to tiredness and irritability. It is at this point that the symptoms become more pronounced. An important feature of this insidious development is that, as the feelings of helplessness increase, awareness of the problems and their effects diminishes; individuals feel bad but fail to respond to the causes. Burnout can affect the individual, their relationships and the work environment in a range of ways (Box 11.12).

Dave

You are on placement with Dave, a fellow first year student. Over the last month he has become snappy with patients/clients, is often late on duty and looks unkempt. He seems harassed and frequently gets personal phone calls that he either asks others to say that he is not there, or takes them on his own.

Student activities

[Resource: Nursing and Midwifery Council 2004. The NMC code of professional conduct: standards for conduct, performance and ethics. NMC, London (clauses 8.2, 8.3, p. 11)]

Managing work-related stress

However, while nursing is considered to be a stressful job, several important features of the work counter the negative effects of work-related stress. Nursing can be very rewarding work and if there are good supportive relationships nurses appear to tolerate and cope with potential stressors very well. The ability to discuss work pressures and develop new adaptive skills have been identified as protective so frequently in studies that providing mentorship and clinical supervision opportunities is considered central to good practice. Another important consideration is that an individual who identifies that they are stressed can use the problem-solving process of care planning to meet their own needs.

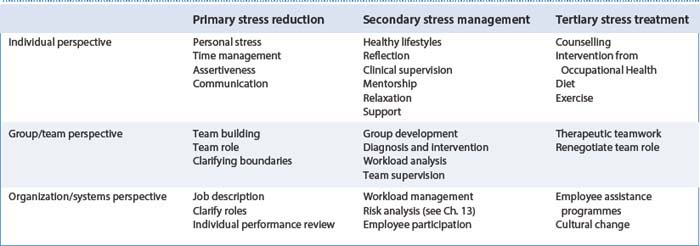

Schaufeli and Enzmann (1998) developed a matrix that provides a useful summary of the interventions that can be implemented to reduce stress-related problems caused through work (Table 11.4).

Traumatic stress

Some events, particularly if they are sudden, intense and life threatening may so overwhelm a person’s coping ability that the capacity to process emotions is impaired. These events include being involved in serious accidents, natural disasters, violent crime or life-threatening illness/injury. In nurses, the sudden unexpected death of a patient, dealing with major incidents/accidents and exposure to threats or violence may generate the same types of response, generally described as an acute stress reaction.

Normal and frequently adaptive responses to extreme stress are shock and denial, both of which ‘switch off’ the immediate emotional response. Emotional shock is described as feeling stunned, dazed or numb. In health staff dealing with disasters, denial may leave them feeling disconnected from the horror of the situation but more importantly it allows them to function. However, these initial effects are temporary and because they prevent people making sense of the emotions at the time of the event, are typically followed by a number of other effects, which may include the following.

For the majority, these symptoms will gradually reduce but how they are experienced and how long they last is highly variable. These variations, as in other stress reactions, are dependent on the person, their interpretation of the situation, other stressors and the availability of support.

Managing traumatic stress

Symptoms persisting longer than 6 months are called post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which may require more specialist help. Therapies are based on cognitive behavioural psychotherapy and some people benefit from antidepressant drugs. Even when the symptoms are severe, many people will recover with appropriate help.

Until very recently the individual was helped to review traumatic experiences in order to make sense of them in a process known as ‘critical incident debriefing’. Unfortunately, a critical fact was ignored, which is that the response to serious trauma is adaptive, it protects a person from being overwhelmed. Recent studies on formal debriefing have suggested that not only is there no evidence that it protects people from long-term problems but it also may increase risk (Bisson et al 2000).

The guiding principle in dealing with others who have experienced traumatic stress is to provide a safe, supportive environment with the opportunity to talk if required.

The best interventions appear to be in preparing people to deal with potential trauma. Individuals who understand what reactions can be expected, and how feelings of guilt and responsibility are common but usually inaccurate, are less likely to develop long-term problems. For example, training in the management of aggressive clients should not only address the skills involved, they also need to address the psychological effects of aggression on the nurse.

Stress and patients, clients and carers

Feeling well, being physically fit and well-nourished all contribute to the ability to deal with stressors and contribute to confidence and self-worth.

When an individual’s health is compromised they must deal with the added stress associated with their condition, at a time when their coping resources are also reduced. Illness is a poorly defined concept: it may describe the presence of specific disease but the word has much broader connotations. The word can be linked with or used to describe anything that causes evil, harm, pain or trouble, and historically was used to describe things going badly or getting worse. Even when describing specific conditions, the link is with dis-ease, i.e. to have no ease.

Many of the common effects of illness present significant physical and psychological challenges that can reduce or exhaust a person’s coping resources. These can include:

In primary care the interplay between physical and emotional health is well understood; it is estimated that up to 80% of consultations have a significant psychological component. This provides an example of how anx-iety can be adaptive: if people were not concerned about their health they might not seek help.

Yet even when the problem is primarily stress-related the person usually presents with physical symptoms, which can make choosing the best interventions very difficult. Healthcare services also often deal with the consequences of social problems, such as poverty or relationship difficulties, which overwhelm coping resources and adversely affect health.

When admission to hospital is required it is likely that this will be accompanied by the sense of threat. This may be intensified for people with learning disabilities and also for carers of people with complex needs. Again the main mediator of the anxiety experienced will be based on the meaning the person attaches to the condition. However, other features appear to significantly increase the potential for stress and anxiety (Box 11.13).

Stress following admission

Two related issues, body image and expressing sexuality/sexual identity, can also be highly significant in the person’s response to illness (see below).

Body image

Body image is the mental representation people have of their body and physical appearance. The view of physical self is central to the person’s sense of identity, social value and self-esteem. Changes in body image, particularly if they involve loss of function, impaired ability to communicate or visible signs of illness and injury can be particularly traumatic. Where the change is likely to be temporary, individuals may simply detach from the situation, putting their life on ‘hold’ by adopting the sick rolekand making no attempt to adapt. This avoidance strategy can be highly adaptive in such situations. However, a change that is likely to be permanent often leads to grief-like reactions in which initial shock is followed by profound depression and feelings of anger. In these cases, adaptation can be difficult and delayed.

Expressing sexuality

Expressing sexuality is linked to gender identity, attractiveness, fertility and sexual functioning and gives a person a sense of value and self-esteem. Changes caused by trauma or illness that impact on these areas appear to have emotional effects much more pronounced than would be expected from just functional loss. The presence of visible lesions, stoma formation or loss of body parts, e.g. female breast, or sudden weight changes are all particularly difficult to cope with. Loss of sexual functioning, factors affecting sexual performance, e.g. erectile dysfunction, and infertility may reduce self-efficacy and increase stress and depression.

Coping with illness

Illness can often highlight major differences in the demands made by the situation and the resources a person has available to deal with them. Coping often involves ongoing appraisals and reappraisals of a situation in which individuals may attempt to alter the problem or their emotional responses to the problem.

Attempting to alter the problem is problem-focused coping and depends on the person believing that the problem is controllable or changeable. Ideally, actions should be based on analysis of the situation and planning solutions before the problem is dealt with. However, often actions are based on attempts to confront situations assertively which may involve actions based on anger, thus increasing risk.

Emotion-focused coping strategies that aim to control the emotion are frequently used when the person believes that they cannot change the stressor, either because they believe that they lack the resources/skills or the situation is insoluble, e.g. bereavement (see Ch. 12). Coping can involve attempts to avoid exposure to the stressors or suppressing its effects with alcohol or drugs. Alternatively, a person may seek social support or alter their appraisals of the situation by attempting to reduce its importance.

Social support provides emotional support through empathy, understanding, caring, etc., supporting self-esteem and offering practical help or information. People differ in their needs for social support; for those who like to cope alone, social support can be detrimental.

Helping patients/clients and carers to cope – role of the nurse

The nurse is an important resource which patients/clients and carers often rely upon to reduce the demands made upon them and enhance their coping resources. In serious acute situations where life-saving treatments are required this might be difficult; however, in the longer term, enhancing and supporting the patient’s/client’s coping skills becomes more relevant.

Although dealing with distressed individuals can be emotionally draining, the nurse needs to maintain an aspect of calm and helpful concern. Nurses can help the patient/client or carer focus on the important issues, provide useful though often limited information, help the person to identify what immediate actions are needed and offer practical help as in acute stress attention and memory may be impaired.

Nurses should anticipate the potential for stress and anxiety in their patients/clients and plan actions to prevent or minimize the more damaging effects. It is import-ant to recognize that many of the anxieties a patient/client may have are realistic and so prevention may be difficult. As there is also the problem that anxiety and stress often interfere with logical thinking and memory, interventions are best made before feelings become too strong, ideally before the stressful event. Patients/clients and their carers, with appropriate and timely help from the nurse, may cope much more effectively.

Patients/clients/carers may also be reluctant to discuss anxieties so as to avoid embarrassment; again the nurse can prevent problems by introducing such subjects into conversation. The effective use of nursing models to inform assessment and interventions should mean that a wide range of issues are specifically addressed, even when they may not appear to be related to the presenting problem. Using a structured approach gives the person ‘permission’ to talk about difficult subjects.

There are important mediators of stress and anxiety that the nurse must consider in planning care. Cognitively, both stress and anxiety reflect feelings of vulnerability. There is a perception that demands/threats will overwhelm a person’s ability to cope.

Stress and vulnerable individuals

Children, some people with learning disabilities and other vulnerable people, who do not understand stressful events and have limited coping resources, will be particularly vulnerable and are more likely to respond differently to life events.

The effects of long-term stress on a child’s development have been well documented and have been associated with a wide range of problems in adult life. Gunnar (2004) argues that long-term stress affects emotional areas of the brain. This can alter the child’s future ability to deal with stress-related events.

In common with adults, stress in childhood may relate to issues other than illness, such as bullying (see pp. 294–295) or examination pressures. Children’s behaviour may change, e.g. becoming withdrawn, tearful, depressed, headaches, etc. Children are affected by stress within the family such as that caused by abusive relationships and domestic violence (see Further reading suggestions, e.g. DH 2000).

Children have limited experience of dealing with demands and limited coping strategies, thus anxiety is a common and frequent experience for children. Young children in particular may also have a very limited ability to communicate their distress to adults. So to understand stress in children it is important to consider the age, the developmental stage and their communication skills.

Children are skilled at judging the emotional state of their parents/carers and can become distressed in response to their parents’/carers’ anxiety. This is important for a child who is admitted to hospital, as they have an increased level of stress caused by the reason for the admission and the environment.

Children attempt to make sense of illness and to cope by using much more basic defence strategies, such as regression and repression (see pp. 280–281). Nurses assessing stress and anxiety in children often find that behaviour is a better indicator of a child’s distress than their verbal reports (Box 11.14, p. 294). Children commonly become uncooperative. These behaviours may lead to reduced social support or anger in their carers and so can be seen as maladaptive and damaging. Teenagers in particular can be especially difficult by refusing help and by engaging in high-risk behaviours, which include:

Box 11.14 Age-related stress behaviours

Table 11.5(see p. 294) outlines some age-related techniques that nurses, parents or other carers might use to reduce the child’s distress.

Table 11.5 Reducing distress in children (Adapted from Huband & Trigg 2000)

| Stage | Techniques and aids |

|---|---|

| Infant | Rocking, patting, holding |

| Use of pacifier (sucking) | |

| Use of basic distractions (rattles) | |

| Toddler | Rocking, holding, involvement of parents |

| Distraction: music, bells, rattles, books, party blowers | |

| Use of bubbles | |

| Preschool | Touch, stroking |

| Cognitive distraction: counting, imagination games | |

| Distraction: favourite games, puppets | |

| Story from a favourite book | |

| Basic imagery | |

| School age | Stroking hair, back, shoulders |

| Imagery | |

| Distraction: music, hand-held games | |

| Adolescents | Massage, imagery, cognitive distraction, relaxation techniques |

| Use of stress ball, music, relaxation and discussion |

Children with long-term health problems, e.g. diabetes, when faced with the increased stress associated with the major transition into adolescence, may also start to neglect their condition and increase their health risks.

For nurses working with people with learning disabilities there may be problems in both recognizing and helping to manage stress in their clients. Depending on the nature of the disability the person may have restricted understanding of situations and limited communication skills. In addition, damage to the central nervous system may lead to a reduced tolerance to environmental stimulation, overwhelming their ability to cope. Alternatively, they may become insensitive to stressors, leading to disinhibition and risk taking.

For those with reduced tolerance to environmental stimuli one approach to reducing distress is the use of Snoezelen. This multisensory stimulation technique utilizes lights, tactile surfaces, music and sometimes essential oils (see Ch. 10) to provide an environment that is soothing and relaxing (Box 11.15). Moreover, the client’sfamily can be involved in sessions in order to increase their understanding of the client’s feelings, abilities, etc. and enhance family relationships.

Box 11.15  EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

Snoezelen use for people with learning disability or dementia

Advocates for Snoezelen argue that it can reduce challenging behaviour and enhance mood and concentration, although reliable evidence is lacking. In a review of the literature, Hogg et al (2001) found that some studies demonstrated a wide range of positive outcomes whereas several studies reported entirely negative outcomes.

Student activities

[Reference: Hogg J, Cavet J, Lambe L, Smeddle M 2001. The use of ‘Snoezelen’ as multisensory stimulation with people with intellectual disabilities: a review of the research. Research in Developmental Disabilities 22(5):353–372]

Many older people with learning disabilities evaluate their sense of value and their abilities by comparison with people of their own age. This can lead to problems with self-concept and an acute sensitivity to perceived criticism. For some clients the frustrations associated with these social comparisons and their perceived lack of ability may be expressed in low self-esteem, dependency, self-destructive behaviours or difficult behaviours towards their carers. All of these features are associated with reduced ability to deal with potential stressors; the behaviours used in coping often increase stress in both carers and client.

There is still considerable stigma associated with learning disabilities, which can lead to exclusion, rejection and prejudice. Even when prejudice is not present there can be a general insensitivity to the needs of people with a learning disability, which can add considerably to the stress they experience.

Bullying is a stressor commonly identified in children, people with a learning disability and in other vulnerable adults who are considered different in some way (physically, culturally, intellectually), especially if they are seen as less able or weak (Box 11.16).

Bullying can take many forms. Young people have described bullying in the following ways:

Bullying, particularly if it is prolonged, can lead to behavioural problems, which might develop into lifelong problems. Some commonly identified effects include:

These effects can lead to worsening academic grades and school attendance and to a great deal of unhappiness to the point of depression. Unfortunately, bullied individuals are also more likely to be neglected or even rejected by their peers (Shuster 1999), which also reduces potential support.

Individuals who behave differently, either due to learning disabilities or mental illness, often evoke anxiety in other people. Nurses are frequently in situations in which they need to identify those at risk and be able to refer the problem to appropriate agencies.

Coping with serious illness, chronic problems and disability

There are real differences in the way individuals deal with acute illness and the demands of having to adapt to chronic illness, disability and terminal illness (see Ch. 12). Rather than anticipating recovery, the patient/client and family have to learn instead to live with the continued physical, social and emotional effects of their condition.

Having to deal with a serious or life-threatening condition can generate a great deal of anxiety in both the patient and the people to whom they are closest. Following a period of shock or detachment, those involved try to give the situation a meaning; they try to make some sense of the value of their life in the face of death.

Taylor (1983) investigated coping and adaptation in women diagnosed with breast cancer. She suggested that adaptation often involved the patient addressing three main issues:

Taylor found more positive outcomes in those women who sought a sense of meaning, who believed they had some control and who had high self-esteem than others in their situation. Why these elements have a direct impact on disease-free survival is not clear, though improved immune function due to effective control of stress may be the most likely explanation.

Improved prognosis has also been seen in patients with good emotional support providing a buffer against stress (Spiegel et al 1989). However, an alternative view is that in avoiding high levels of anxiety individuals are more likely to engage in effective health-promoting behaviours and less likely to become depressed. Depression is associated with just giving up, self-care is neglected and treatments may be ignored. Depression worsens outcomes in a wide range of health problems.

Chronic illness and disability

An acquired disability often means that the client’s social roles change and the pressures placed upon the family and carers increase. Throughout there is a need to adapt to many new situations that affect not only health and functioning but also roles and self-concept. Initially, adaptation is resisted but at some point the patient/client must learn to accept the changes and work towards the best outcomes. Patients/clients who fail to make these mental changes often become depressed and possibly self-destructive.

Assessment requires a measure/tool that is inclusive, identifies normal functioning and establishes a baseline from which to evaluate the effect of care at a later date. The assessment also needs to address the needs of the patient’s family, as providing long-term care can have profound effects on family and carers. Long-term interventions include many specialist services and collaborative multiprofessional working (see Ch. 3). However it is good practice for a specifically named person to act as care coordinator and to engage the patient and family in all aspects of care.

Rehabilitation

A full discussion of rehabilitation is beyond the scope of this book and readers are directed to Further reading (e.g. Davis 2006). Rehabilitation involves learning ways of coping with chronic (long-term) illnesses or injury. This may involve maximizing physical abilities, learning new skills, problem-solving and changing appraisals about the condition and its consequences. Many conditions may run a prolonged and chronic course, requiring considerable adaptation by the patient/client and those around them. Conditions may be present from birth, requiring life-long help, or they may be acquired after birth as in psychosis, multiple sclerosis or spinal injuries. Many common conditions such as chronic respiratory disease (see Ch. 17), chronic heart failure and arthritis occur in older adults. Unfortunately, the effects of the increased stress, associated particularly with the acquired conditions, may also be instrumental in maintaining or worsening the condition.

Nurses involved in long-term care should adopt an honest and trusting position, which engages the patient/client and maintains motivation to remain as involved in self-care as is practical (see Further reading, NHS Modernisation Agency 2003). This is important, whether recovery is possible or not: patients/clients who maintain a sense of control are generally less distressed and feel less isolated. Honest and accurate information should never be given in a way that removes all hope.

Models in rehabilitation

It is particularly important in long-term care that the guiding model is person-centred, holistic and allows for multiagency collaboration with patients/clients and their carers. The underpinning processes involved in care planning are outlined in Box 11.17 (see Ch. 14).

An example of using a structured approach is in the development of a Wellness Recovery Action Plan (WRAP). The WRAP was developed by Copeland (1997) as a structured system that enables the active monitoring of distressing symptoms in people with long-term mental health problems. However, many of the principles are applicable to most care situations. The development of a WRAP culminates in a plan that aims to modify or eliminate the most distressing symptoms the patient/client identifies. There are five pivotal principles that need consideration when developing a WRAP:

The development of a WRAP is dependent on framing what is wanted and needed by the patient/client. Patients/clients, although frequently anxious, do know what they can and cannot do and in developing the plan the patient/client can begin to recognize the collaborative nature of the nurse–patient relationship. In time, and with help from the nurse, the patient/client becomes the expert in their illness or disability.

| BBC – useful information about stress and coping | www.bbc.co.uk/health/conditions/mental_health |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Canadian Mental Health Association | www.cmha.ca/english/ |

| coping_with_stress/links.htm | |

| Available July 2006 | |

| The American Institute of Stress | www.stress.org |

| Available July 2006 | |

| The Nursefriendly Stress Resources for Nurses (North American) | www.nursefriendly.com/nursing/stress.htm |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Useful resources website | www.teachhealth.com |

| Available July 2006 |

Bisson JI, McFarlane AC, Rose S. Psychological debriefing. In: Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, editors. Effective treatments for PTSD. New York: Guilford Press, 2000.

Borrill CS, Wall TD, West MA, et al. Mental health of the workforce of NHS Trusts – Phase 1, Final report. University of Sheffield and University of Leeds, 1996.

ChildLine. 2005 Stress. Online: www.childline.org.uk.

Copeland ME. Wellness recovery action plan. Dummerston, VT: Peach Press, 1997.

Department of Health. Our healthier nation. London: TSO, 1998.

Ellis A. Reason and emotion in psychotherapy, 2nd edn. New York: Carol Publishing, 1994.

Gunnar M. 2004 Gunnar Lab. Online: education.umn.edu/icd/GunnarLab. Available September 2006.

Harris N. Management of work-related stress in nursing. Nursing Standard. 2001;16(10):47-52.

Health and Safety Executive. 2002 Work-related stress. Online: www.hse.gov.uk/stress/links.htm.

Holmes TH, Rahe RH. The social readjustment and rating scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1967;11:213-218.

Huband S, Trigg E. Practices in children’s nursing: guidelines for hospital and community. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2000.

Lazarus AA. The practice of multi-modal therapy. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1981.

Lazarus R, Folkman S. Stress appraisal and coping. New York: Springer Verlag, 1984.

Maslach C, Jackson S, Leiter MP. Maslach burnout inventory manual, 3rd edn. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1996.

Menzies-Lyth I. The functions of social systems as a defence against anxiety: a report on a study of the nursing service of a general hospital. Human Relations. 1959;13:95-121.

Salmon G, Jones A, Smith DM. Bullying in school: self-reported anxiety and self-esteem in secondary school children. British Medical Journal. 1998;317(7163):924-925.

Schaufeli WB, Enzmann D. The burnout companion to study and practice: a critical analysis. Philadelphia: Taylor and Francis, 1998.

Selye H. (revised 1975) The stress of life. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1956.

Shuster B. Outsiders at school: the prevalence of bullying and its relation with social status. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations. 1999;2:175-190.

Spiegel D, Bloom JR, Kraemar HC. Effect of psychosocial treatment on survival of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Lancet. 1989;2:888-891.

Taylor SE. Adjustment of threatening events: a theory of cognitive adaptation. American Psychologist. 1983;38:1161-1173.

Yerkes RM, Dodson JD. The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit-formation. Journal of Comparative Neurology and Psychology. 1908;18:459-482.

Davis S. Rehabilitation. The use of theories and models in practice. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2006.

Department of Health. 2000 Domestic violence: a resource manual for health care professionals. Online: www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/06/53/79/04065379.pdf.

NHS Modernisation Agency. 2003 Essence of care: patient-focused benchmarks for clinical governance. Online: www.modern.nhs.uk/home/key/docs/Essence%20of%20Care.pdf.

Payne RA. Relaxation techniques, 3rd edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2005.

REFLECTIVE PRACTICE

REFLECTIVE PRACTICE

CRITICAL THINKING

CRITICAL THINKING

HEALTH PROMOTION

HEALTH PROMOTION ETHICAL ISSUES

ETHICAL ISSUES