Chapter 2 Evolution of contemporary nursing

Introduction

Since early times nursing has developed in response to the changing needs of society. As the structure of society alters, new nursing habits, customs, values and knowledge emerge in response to the composition and health of the population. This chapter outlines the evolution of nursing from the 1700s to the present day and will demonstrate how nursing, which does not exist in isolation, has been influenced by society and the sociopolitical agenda of the day. It explores how contemporary nursing roles have developed in response to the challenges facing healthcare delivery – for example, increased workload, reduction in junior doctors’ working hours, nurses wishing to advance their practice, the focus on person-centred care, increasing the accessibility of healthcare for all and the shift of responsibility for those with chronic illness from the acute sector to the community. In addition, detail is provided about how to become a nurse in the 21st century. By outlining the key roles of the nurse and service users in different settings we hope that this will provide a useful introduction on which to build for those undertaking a common foundation programme.

Evolution of nursing

This section outlines the different values and beliefs about nursing and nurses at different periods since the 1700s, together with the events and context that influenced the changes in thinking. The roles of influential nurses including Florence Nightingale and Mary Seacole, and that of Mrs Ethel Fenwick – a force in the campaign to introduce the nurse registration – are explored. Also considered are major events in nursing such as professional registration and statutory regulation, and the influence of both World Wars (1914–1918, 1939–1945), the inception and development of the NHS and the more recent developments in professional regulation and education. The development of specialist nursing such as the care of children and people with mental health problems is also explored.

Nursing in the 18th and 19th centuries

In the 1700s, in times of accident or sickness, being in the comfort of one’s own home was normal and lay people largely carried out the nursing role in the community. Catholic nuns who had taken vows of poverty first staffed hospitals and many nurses were expected to work not for monetary gain but from religious inspiration or a ‘calling’. ‘Nursing’ was also associated with maternity care, where women were expected to show the same love and devotion when caring for complete strangers that they naturally showed to their children. The underlying values of the time have been described as asceticism (Pearson et al 1996), which were:

Carers often lived within the institution where care was provided and consequently their employers commonly exploited their 24-hour presence.

During the 1800s, the foundation of the Royal College of Surgeons led to a closer relationship between medical education and hospitals. The governors appointed matrons who were responsible for household affairs, supervision of nurses and other hospital servants. The best matrons tried to select women of good character to be head nurses and staff nurses. However, the majority of nurses were for the most part rough, dull and poorly educated women. Sairy Gamp, described by Charles Dickens in Martin Chuzzlewit, epitomized the nurses of the day. Many nurses worked in appalling surroundings with little or no education. Their work was considered to be a particularly repugnant form of domestic service. Motivated by the desire to earn money rather than by self-sacrifice or devotion to their job, they drank large amounts of alcohol, took snuff, were generally unkempt and lacked delicacy, discretion, tact and concern for their patients.

The influence of Florence Nightingale

Florence Nightingale was born in Florence, Italy, in 1820 of wealthy, middle-class parents. After several attempts to receive formalized training in 1850 and 1851, she spent brief periods in Germany at a Protestant institution that trained deaconesses in childcare and nursing. Soon afterwards Florence Nightingale became Superintendent of Nurses at the Institution for the Care of Sick Gentlewomen in Distressed Circumstances in London. For this she received no pay but was able to display her skills in nursing and nursing administration, which included greatly improved standards of nurses and nursing care and also the expectation that care should be based on compassion, observation and knowledge.

In 1854 the Secretary for War appointed Florence Nightingale to travel with a group of 38 women to Crimea to provide nursing services. Later, other nurses joined them so that by the end of the war Florence had 125 nurses under her supervision. Despite resistance from the medical establishment, Florence and her team worked long hours to establish hygienic standards of care. She was obsessed with discipline and through determination and persistence improved ventilation and reduced overcrowding, thereby reducing the mortality rate of wounded soldiers. One of her legacies was the ‘Nightingale ward’, a ward layout where long rooms have beds spaced out on each side, which are still found in some areas today. Florence recognized the soldier’s human dignity and in return they held her in high esteem. She became known as the ‘Lady with the Lamp’ and was glorified by the public and press back home and her reputation grew.

On her return to England, Florence had developed revolutionary ways of collecting statistics known as ‘model forms’ and consequently many now regard her as the first research nurse. Although Florence found she was a heroine, she never enjoyed her fame and disliked the sentimental reference that her name inspired. The only testimonial she would accept was a fund, heavily subscribed by the public and named in her honour, which she used to found training schools for nurses.

The success of the Nightingale reforms led to the rapid expansion of nurse training schools, initially in London voluntary hospitals, then to larger provincial voluntary hospitals and finally to new hospitals being built by local government and poor law authorities (Baly 1995). Despite this there was still a need for nursing at home and Florence worked closely with William Rathbone to establish training for district nurses. District nursing started as a voluntary service, run by voluntary committees, until the value of the service was recognized and local authorities gradually began to accept more responsibility for sick people in the community. It was also recognized that certain occupations carried a particular risk to health and some firms employed a nurse to look after the health of their employees.

As a result of her work, Florence was able to define the nature of nursing clearly and how nursing was distinct from and not subservient to medicine (Box 2.1). This paved the way for the establishment of nursing as a profession with a sound and specific educational base.

(Adapted from Selanders 1993)

Florence Nightingale’s values

Nursing is a calling

Mankind can achieve perfection

Mary Seacole

Mary Seacole was another nurse and healer who contributed to the welfare of allied soldiers in the Crimean War. She was of mixed Scottish and Jamaican descent. Although experienced in the treatment of fevers and wound care, the authorities in England rejected her, so she visited battlefields, dispensing comfort and provisions to the wounded. In 1856, she returned bankrupt to England and published a book about her travels, which was one of the few published writings of any black woman before the 20th century. She was helped financially through funds raised by the soldiers she had nursed and finally received a pension from Queen Victoria. Until the centenary of her death in 1981 Mary had been forgotten but renewed interest in her achievements resulted in a nursing award being named after her. In 2003 a campaign was launched for a permanent memorial of her in London and in February 2004 in an online poll she was voted the greatest black Briton.

Health visiting

The first home health visiting began in the mid-1850s as a public health service which focused on problems of sanitation and epidemics; nurses, sanitary engineers or lay visitors were sent into the homes of families with young children to offer advice about health and hygiene (Kamerman & Kahn 1993). At the same time a ‘Sanitary Association’ was formed to teach the ‘laws of health’, followed 10 years later by the ‘Ladies Sanitary Association’ enabling respectable women, known as ‘Health Missioners’, to teach health to mothers. From the voluntary work of these health missioners, health visitors (HVs) emerged and the importance of lowering the infant mortality rate ensured that their work became recognized and brought under the direction of the Medical Officer of Health. The work of early HVs was mainly educative and persuasive; they visited as counsellors to the whole family rather than either inspectors or nurses. The first training-specific health visiting course was established in 1892, around the same time as the first social work courses in the United States.

Development of nursing specialties

Specialist nursing services such as children’s nursing and mental health nursing have their origins in the 1800s.

Children’s nursing

Early accounts of paediatric home visiting started during the mid 1800s (Royal College of Nursing 1984). Charitable dispensaries were established as the most appropriate means of treating sick children (Carter & Dearmun 1995) and there was strong opposition to admission of children to hospital (Lansdown 1996). Other fears arose because children were often malnourished and susceptible to infection and hospitals were widely viewed as a major source of infection (Watt & Mitchell 1995). However, in recognition of need for specialist services for sick children, Dr Charles West founded The Hospital for Sick Children in Great Ormond Street, London, in 1852. This was followed by the Edinburgh Sick Children’s Hospital in 1860. The aims of Great Ormond Street Hospital were to teach women the specialist skill of children’s nursing and to provide advice for mothers. By 1888 it was recognized that sick children required specialized nursing and sick children’s nurses required specialist training. A 2-year training programme was introduced almost 10 years before the start of training for adult nurses (Carter & Dearmun 1995).

Mental health nursing

During the 1800s there was also a change in attitude towards the mentally ill. At that time, people with mental distress were labelled as ‘insane’ and commonly marginalized. Those who could afford treatment were cared for in institutions known as asylums, while many of those who could not were sent to prison.

In the early 19th century there was a desire to tackle poverty, sickness and ignorance and general acceptance of a common ethical principle, namely that society had a responsibility for the weak. It was also recognized that mental health nursing (then known as asylum nursing) should be a skilled profession, needing intellectual and personal gifts rather than just strong nerves and powerful muscles.

Browne, Medical Superintendent at the Royal Edinburgh Asylum in 1838, recognized that the people who were closest to the patients, who spent most of their time with them and who managed them when they became distressed were untrained attendants (Nolan 2000). In attempting to improve this he started a course of lectures, which were a landmark in the history of mental health nursing. The first manual for attendants working in Mental Hospitals, The Handbook for the Instruction of the Attendants of the Insane, was published in 1885. This ‘Red’ Handbook became the content of training, run by the Medico-psychological Association in the late 1880s, for attendants working with the mentally ill. It included basic anatomy and physiology, principles of general nursing, the mind and its disorders, care of the insane and general duties of the attendant/nurse.

The beginning of education and regulation

By the 1880s nursing leaders were beginning to question whether nurses should be required to pass a public examination before entry to a register, as medical practitioners had been required to do since 1858. Opposition came from a number of quarters, perhaps most significantly from Florence Nightingale who thought that a central examination might undermine her philosophy of nursing. The matron of the London Hospital was also against registration but the matron at St Bartholomew’s Hospital in London, Ethel Gordon Manson, was convinced of the need to raise standards and gain professional status for nursing. In 1887 she married Dr Bedford Fenwick who was active in medical politics and shared his wife’s aspirations concerning the registration of nurses. In 1893, Mrs Fenwick took over the publication of the Nursing Record and then used this to underpin her campaign for registration. In 1903 the name changed to the British Journal of Nursing, with Mrs Fenwick remaining as editor, a position she occupied for nearly 50 years.

In 1887 Mrs Fenwick founded the Royal British Nursing Association (RBNA). Around the same time she refused to include graduates of an examination set by the Medico-psychological Association for asylum attendants. In 1895, Mrs Fenwick explained grounds for this exclusion:

No person can be considered trained who has only worked in hospitals and asylums for the insane … considering the present class of persons known as male attendants, one can hardly believe that their admission will tend to raise the status of the association.

The fact that asylum attendants had to care not only for people with mental health problems but also their physical needs suggests that they should have been eligible. However, Brooking et al (1992) argue that this snub did not greatly trouble the attendants as their main concerns related to pay and conditions of service.

The success of the nursing reforms led to a rapid increase in the number of training schools. Advances in medical science demanded a more conscientious type of nurse. Middle-class women viewed nursing as a worthy career and at that time only teaching or the newly developing civil service offered an alternative. However, as a result of the rapid change, the tradition of discipline began to disappear. Criticism was stifled and orthodoxy and conformity were the norm and, despite Miss Nightingale’s remarks about obedience being ‘suitable praise for a horse’, obedience was seen as a cardinal virtue.

Nursing in the 20th century

The Society for the State Registration of Nurses was formed in 1902, with Ethel Fenwick as Secretary and Treasurer. The National Council of Trained Nurses of Great Britain and Ireland was established 1904, with Ethel Fenwick as President (Royal British Nurses’ Association 2003).

Two other legacies of the Nightingale reforms soon became a travesty – the nurses’ home and the method of payment. The nurses’ home that was originally supposed to provide a cultural and educational background for young women who had left middle-class homes, and to raise the sights of those who had not, had become a cheap way of housing the labour force who had to work around the clock. The first student nurses, known as probationers, were supernumerary to the workforce but as low pay was introduced under the auspices of ‘getting the right type of girl’ it became questionable whether probationers were actually pupils or workers.

In trying to change the negative image of nursing and make it more respectable, nurses were torn between delivering care and maintaining their knowledge, independence and status. This was managed by linking nursing firmly to medicine and describing the function of nursing as ‘carrying out doctors’ orders’.

In 1902 the Midwives Act required that all practising midwives undertook training and registered with the Central Midwives Board. The Central Committee for the State Registration of Nurses was formed 1909 with Ethel Fenwick as joint honorary secretary. Between 1910 and 1914 the Central Committee introduced annual parliamentary bills on nurse registration but these were blocked. The impact of World War 1 (1914–1918) and the unqualified female volunteers, the Voluntary Aid Detachment, sent to assist nurses that threatened to dilute nursing led to the establishment of an organization for trained nurses.

The College of Nursing (that later became the Royal College of Nursing) was established 1916, and in 1917 there were inconclusive discussions about a merger between the RBNA and the College. The principal objectives of the college were to:

The College of Nursing refused further pleas by the Medico-psychological Association to allow attendants to join, despite an increasing number taking the Associations course and examination.

In 1919, the Nurses Bill received royal assent and the General Nursing Council (GNC), chaired by Mrs Fenwick, was established 1920, with the duty of setting up a register of qualified nurses and a syllabus for instruction and examination. The GNC register of qualified nurses included:

Later the register included parts for nurses of infectious disease and nurses trained in the care of ‘mental defectives’ (people with learning disabilities).

Women were attracted to sick children’s nursing because the age of entry into training was 21 years rather than 23–24 years for general nurses (Carter & Dearmun 1995). The new GNC started its own course and examination for asylum attendants but this carried little weight as the qualification was not required to gain a senior position in an asylum (Brooking et al 1992).

In 1921 the GNC set up a Disciplinary and Penal Committee, which had the power to deal with state registered nurses (SRNs) who were not ‘fit and proper persons’, and was able to prosecute those purporting to be registered nurses (RNs) when they were not. Although standards for competence were tested by examination, the most crucial characteristics of professional status were personal behaviour including obedience, tidiness and unquestioning loyalty. However, the profession had handed over control of entry qualifications and the requirements for basic training to the government who were also responsible for staffing hospitals as cheaply as possible. Although the GNC tried to overcome this disadvantage, statutory control was present and the first hallmark of a profession, that it controls its own standards of entry and training, was lost (Baly 1995).

A review of mental health nursing in 1924 identified the number of mental health nurses in England and Wales and recommended that:

However, due to the poor prevailing economic conditions at the time, none of these recommendations was seriously addressed (Nolan 2000).

General nursing gradually became acceptable work for middle-class women. The advantages included the ability to lead an independent life in respectable company and an occupation that was no longer menial, but one that involved training and exercise of intelligence. Working class women also flocked into nursing as they could earn more, do less menial work than in domestic service and move up the social ladder.

The British College of Nurses (BCN) was founded by Mrs Fenwick in 1926, with herself as President and Dr Fenwick as Treasurer. In 1927 the College of Nursing applied for its Royal Charter and the application, which was opposed by the RBNA, was granted in 1928 and it was renamed the Royal College of Nursing (RCN) in 1939. The BCN closed in 1956 (Royal British Nurses’ Association 2003).

The 1930s

During the 1930s the public image of general nursing continued to be that of ‘heroine’ but the media was recognizing that nurses required education, which included development of both skills and knowledge, for practice. Nurses were depicted as brave, rational, decisive, humanistic and autonomous. It was an era of fantasy, romance and adventure where the focus of nursing was loyalty to physicians and patients. Gradually the new values of ‘romanticism’ were taken on board and were likened to hero worship of the leaders and doctors as nurses had a subservient relationship to them. Nursing was dependent on medicine to take the main responsibility for decision-making and nurses became adept at suggesting a course of action to a doctor in a way that allowed the doctor to perceive he had initiated it (Stein 1967). During the 1930s there was a considerable influx of men into mental health nursing, especially from depressed areas.

High unemployment and a lack of alternative careers made it easy to recruit nurses. However, there was widespread dissatisfaction in the profession over recruitment, pay and conditions, which led the government to set up a committee chaired by Lord Athlone to consider issues of shortages, wastage and training of nurses. This committee made a number of recommendations to improve staff conditions that would encourage nurses to stay in the profession. This included:

However, the report was low key and by 1939 the country was under the shadow of World War 2.

The impact of World War 2 (1939–1945)

The war changed the situation from an apparently adequate supply of nurses to one of acute shortage. Nurses from all fields were recruited for the armed forces, which resulted in too few nurses to care for civilians. The Ministry of Health set up an Emergency Nursing Committee to organize a Civil Nursing Reserve to assist employing authorities to meet additional staffing needs occasioned by the war. This supplied upwards of 1800 nurses and unwittingly through this the Ministry of Health played an important part in the development of nursing by:

The consequence of this was that in 1941 the Ministry of Health recommended that all hospitals paid salaries equivalent to those in the reserve. To assist the Ministry of Health in its new role as employer, a Division of Nursing was created and the first Chief Nursing Officer appointed. In 1943 the pay of nurses was put on a level with that of teachers but this made little difference to the recruitment figures so steps were taken to improve conditions of service (see Box 2.2). The Nurses Act 1943 came into force and State Enrolled Assistant Nurses became subject to the discipline of the GNC.

[Resource: Oxtoby K 2005 A lifetime in nursing. Nursing Times 101(24):24–25]

Conditions of service in 1943

During World War 2 the recruitment and distribution of nurses was subject to specific controls:

By the end of World War 2 hospital beds had to be closed due to shortages of nursing staff. Through the necessity to attract sufficient recruits, entry qualifications and the age of entry were lowered. Students and auxiliaries were the main recruits and qualified nurses became frustrated. Training began to suffer as there was insufficient support and supervision for students who began to feel that their preparation was inadequate. Many of those who stayed were rapidly promoted to positions of responsibility for which they were ill prepared. During the war years, some nurses took on increased responsibilities, for example on military ships they were expected to conduct physical and psychiatric assessments and initiate treatments, often without any medical support. Their efficiency, confidence and skills demonstrated what could be achieved outwith institutional bureaucracy. However, their experience was by no means comprehensive and they lacked knowledge and skills in managing the chronic conditions prevalent in civilian life (Nolan 2000).

Post war, nurses continued to administer doctors’ orders and to monitor their patients closely. Military nurses maintained their allegiances and the number of male nurses increased as demobbed servicemen with medical experience joined the profession. Many joined the Society of Registered Male Nurses as the RCN remained closed to them until 1960. Through this they sought to improve the status and practice of mental health nursing.

The influence of the National Health Service (NHS) on nursing

The NHS was established in 1948 with the aim of healthcare being free at the point of delivery (see Ch. 3). Nurses were in favour of the NHS and felt part of the service. Hart (2004, p. 55) notes that in the Nursing Times that year Mary Witting said ‘the great principle has been accepted; never again need any of us suffer disease through lack of money’. However, from the outset there was a serious shortage of nurses and many hospitals were critically dependent on students. Significantly, during the planned introduction of the NHS, no provision for the education of nurses had been considered. In 1950 the following recommendations were made:

Large mental hospitals were usually located in the countryside and operated as self-sufficient communities, even down to having their own graveyards. There was strict regulation with rather impersonal procedures for patients, and tight discipline and a much-feared hierarchy for nurses. Nevertheless, there was a sense of common purpose in a community that was virtually self-contained and self-maintaining (Brooking et al 1992). Increasingly, mental hospitals developed open-door policies, enabling patients to take weekend leave and enjoy a broader range of activities including art and industrial therapies such as assembling components to provide rehabilitation and occupy their time with meaningful activities. Accommodation and recreational facilities improved for staff and alliances were built between doctors and nurses.

During the 1950s attitudes to children being cared for in hospital began to change. It was suggested that emotional damage might occur if children were separated from their parents for lengthy periods. The Ministry of Health commissioned the Platt Report (Ministry of Health 1959), a report on the welfare of children in hospital. At the same time it was recognized that nurses needed better communication skills and the ability to give patients information prior to admission. There needed to be better signposting within hospitals/care settings, flexible visiting times and easier access for families to speak to a doctor and/or nurse. In addition, attitudes to people with disabilities, older adults and those with rehabilitation needs were also changing, which had implications for hospital nurses, district nurses and HVs who all needed to be aware of increasing resources and appliances available for people with disabilities.

The influence of the medical model

During the late 1950s, with the growth of technology, romanticism began to lose favour and the value system of pragmatism began to evolve. Pragmatism is associated with a practical approach to assessing situations and acting on them in a practical way. Nurses were expected to extend their role to incorporate the impact of new technical knowledge. At this time, the nursing profession had a poor image regarding relationships with other hospital staff and colleagues (see Ch. 9). There were many complaints about ‘petty discipline’ and authoritarian attitudes existed for the following reasons:

The trend towards specialization reflected the reductionist approach where, as a result of the need for knowledge, the body is split into parts or systems and each part is studied independently. Subsequently, innumerable specialties in both nursing and medicine emerged, each concerned with only a small part of the whole person.

Research undertaken at this time recognized nursing as a particularly stressful occupation (see Ch. 11) as nurses were in constant contact with people who were ill or injured and whose recovery was not always certain or complete (Menzies 1961). To avoid intense anxiety, nursing care was based on a patient’s medical diagnosis rather than on their individual needs. Nursing actions were based around familiar ward routines and conformity was expected. Along with this went depersonalization and categorization of patients according to bed numbers and disease. This approach to practice reflected the medical model.

Davies (1976) emphasized the importance of the power and control invested in the role of the traditional hospital matron who was perceived to be managing an obedient and highly useful nursing workforce. The matron was seen as the powerful figure and nurses as quiet, obedient followers of routine. Nevertheless, by carrying out all jobs, however humble and routine, that were necessary for patient comfort and recovery, nurses gained public sympathy and state support. Their daily work was usually organized around ‘ward routines’ that focused on carrying out a series of tasks, e.g. bedpan rounds, dressing rounds, getting everyone who was able out of bed for breakfast. Some of the benefits of this task approach were:

In the 1960s a formal management structure was introduced as career development for senior nursing staff. This aimed to increase the status of the profession in hospital management and consequently the role of matron was abolished. The Salmon Report based nursing management on three tiers:

This extended the career prospects for nurses by creating nursing officers who had responsibility for nursing. Many nurses did not take readily to these new roles and there was no career progression for those who wanted to continue having patient contact. Also, at this time, nurse theorists were beginning to challenge the traditional view of nursing characterized by:

The influence of nursing theory

During the 1960s there was a dramatic change in attitudes acknowledging the shift away from nurses as doctors’ assistants, which was increasingly encouraging nurses to accept direct responsibility and accountability for their actions and their consequences, and for the decision-making processes that led to those actions. An influential quote from Henderson (1961, p. 42) at that time,

The unique function of the nurse is to assist the individual, sick or well, in the performance of those activities contributing to health or its recovery (or to a peaceful death) that he would perform unaided if he had the necessary strength, will or knowledge, and to do this in such a way to help him gain independence as rapidly as possible. This aspect of her work, this part of her function, she initiates and controls; of this she is master.

At the same time other nurse theorists also began to describe what nursing was about and saw the development of the first nursing models, which are descriptions of what nursing is (Pearson et al 1996). Nursing models are based on beliefs about the following factors:

Nursing models are explored in detail in Chapter 14. There are many models, each reflecting the diverse perspectives of nursing roles and care settings (Box 2.3).

Box 2.3 Examples of models used in different care settings

Adult nursing

| Biomedical | Medical model |

|---|---|

| Goal attainment | King – 1981 |

| Adaptation | Roy and Andrews – 1999 |

| Activities of living | Marriner Tomey et al – 2000 |

| Self-care | Orem – 1991 |

| Systems | Neuman – 1995 |

| Transformative | Dunphy & Winland- |

| Brown – 1998 |

Emergence of nursing models saw the beginning of the move away from the medical model (see p. 43 and Ch. 1) and a move towards the holistic approach (see p. 47) which focuses on the value of the person and the quality of their existence and experience. However, as medicine became more technical and more scientific, nurses increasingly took on more skills and procedures that had previously been carried out by doctors. At that time student nurses were part of the workforce and provided most of the nursing care with minimal supervision.

The early influence of nursing research

In the early 1970s the Briggs Report (Department of Health and Social Security 1972) set the expectation that nursing courses would incorporate research methods and that their findings would be used in nursing practice. The first nursing research was undertaken around that time; however, it had little impact on nursing practice. The Briggs Report also recommended the replacement of the existing regulatory body (the GNC) and the Nurses, Midwives and Health Visitors Act was passed in 1979. Consequently, the United Kingdom Central Council for Nursing, Midwifery and Health Visiting (UKCC) and four National Boards for nursing were established, one for each UK country, with a specific responsibility for education. The core functions of the UKCC were to maintain a register of UK nurses, midwives and health visitors, provide guidance to registrants and handle professional misconduct complaints (see Chs 6, 7). The main functions of the national boards were to monitor the quality of nursing and midwifery education courses and to maintain the training records of students on these courses.

The influence of humanism

Since the 1960s the underlying values and beliefs of nursing have become those of humanism, which explores the value of human beings, their uniqueness as individuals, quality of life and freedom of choice. These beliefs value the ability of others to know and understand people’s feelings and their lived experience. The values of humanism include:

Many nurses feel strongly that caring lies at the very heart of nursing. Kitson (1996) argues that in addition to the capacity of nurses to care for others, they also have the abilities to develop a nurse–patient helping relationship (see Ch. 9) and to share professional knowledge.

The nursing profession was recognized as being unique because it addresses the responses of individuals and families to actual and potential health problems in a humanistic and holistic manner (Marriner Tomey et al 2000). However, the NHS was originally built around the idea that the ‘professional management’ function was the same regardless of the organization or person to which it related. This new approach challenged the traditional professional ethos and healthcare professionals were forced to consider care in terms of its cost effectiveness. The new style also focused on quality assurance and the identification of standards of care. This raised a problem with the ethos of ‘caring’. Caring was difficult to measure and for influential managers who sought value for money it did not provide the hard evidence needed to measure outcomes (Norman & Cowley 1999). Consequently, the cost-driven management style of the late 1980s continues to influence nursing and to increase the drive for technical competence and scientific nursing skills.

Code of professional conduct

The UKCC developed the first code of conduct for nurses, midwives and HVs in 1984, which set out for the first time key expectations for professional practice and accountability. Its purpose was to protect the public through providing professional standards, to inform the public of the standard of professional conduct they could expect, to ensure accountability and to make it clear that RNs, midwives and HVs have a duty of care to their patients and clients. This has been refined and is currently published by the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) as The NMC code of professional conduct: standards for conduct, performance and ethics (NMC 2004a) (see Ch. 7).

Project 2000

In the 1980s it was recognized that, as a result of changing disease patterns and social contexts and the introduction of reforming modes of care delivery, there would be new healthcare needs that required a different kind of nurse. In order to meet this need the UKCC (1985) put forward a different approach to the education of nurses. The main proposals included:

Nursing skill mix before Project 2000

Before Project 2000 a typical ward might have had the following staff to cover the day shifts:

Moving from rituals to evidence-based practice

The development of education and regulation for nurses and midwives failed to bring nursing the power and prestige that were anticipated by early nursing leaders. Over the last 15–20 years there has been a shift from ‘the practitioner knows best’ to the belief that one can never take one’s own practice for granted. However, nursing had still only developed a limited body of knowledge that could be defined as nursing and which was exclusive of other disciplines. Consequently, the purpose of nursing research is to establish a body of nursing knowledge which in turn increases the professional status of nursing (see Box 2.5 and Ch. 5).

The attributes of a profession include:

The introduction of the nursing process during the 1980s enabled nurses to develop a more systematic approach to care (see Ch. 14). There was the expectation that nurses should carry out best practice that was in the interest of their patients and that they would be accountable for their actions. The systematic nursing process gradually evolved into evidence-based decision-making, a process of turning clinical problems into questions and then systematically locating, appraising and using current research findings as the basis for clinical decisions (see Ch. 5). By using a structured problem-based approach practitioners can logically apply the best available evidence to their care, i.e. evidence-based practice (see Ch. 5). Table 2.1 summarizes the major events influencing the evolution of nursing discussed in this section.

Table 2.1 Major events in the evolution of nursing

| Date | Context | Influences on nursing practice |

|---|---|---|

| 1700 | Care was largely carried out in people’s homes by lay people | Catholic nuns staffed hospitals and many nurses were expected to work not for money but from religious inspiration or a ‘calling’ |

| 1800 | Foundation of the Royal College of Surgeons led to a closer relationship between medical education and hospitals | Governors appointed matrons responsible for household affairs, supervision of nurses and other hospital servants |

| Ordinary nurses were of lower status, received some money and a beer allowance, endured appalling working conditions and had little or no education | ||

| 1834 | Poor Law Amendment Act | Workhouses with intolerable conditions for poor, sick and needy people |

| Sick people nursed by elderly pauper women | ||

| 1854–1856 | Crimean War | Florence Nightingale introduced measures such as sanitary principles, which contributed to a reduction in mortality rates of wounded soldiers |

| Mary Seacole visited battlefields, dispensing comfort and provisions to the wounded | ||

| 1856 | Florence Nightingale described as the first research nurse | Using statistics she collected during the Crimean War, she illustrated the need for sanitary reforms in all military hospitals |

| 1858 | Improvement of standards | Doctors who passed a public examination entered on a register. By 1880 nurse leaders were suggesting that nurses should be required to do the same |

| 1860 | Florence Nightingale founded the first nursing training school | The Nightingale Training School and Home for Nurses based at St Thomas’ Hospital in London |

| Attitudes towards the poor changed, poverty implied sickness | Poor Law Hospitals and ‘probationer’ nurses | |

| 1914–1918 | World War 1 | Young women known as Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) assisted nurses |

| 1919 | Nurses Act | Registration of UK nurses |

| 1920 | General Nursing Council was established | The three Councils had clearly prescribed duties and responsibilities for the training, examination and registration of nurses and the approval of training schools for the purpose of maintaining a register of nurses for England and Wales, for Scotland and for Ireland |

| 1939–1945 | World War 2 | Nurses joining military services led to recruitment problems at home |

| Dissatisfaction over nurses’ pay and conditions | ||

| 1943 | Recruitment of nurses remained a problem | Pay parity with teachers |

| Introduction of nursing assistants, later to become enrolled nurses (second level nurses) | ||

| 1960 | More policy decisions for nurses | Salmon Report – formal nursing management structure but no clinical career structure |

| 1979 | Nurses, Midwives and Health Visitors Act | Review of registration and education of nurses, midwives and health visitors |

| United Kingdom Central Council for Nursing, Midwifery and Health Visiting (UKCC) and four National Boards were established | ||

| 1983 | Griffiths report | Introduction of general management culture – NHS to be run as a business |

| 1986 | Project 2000 | Higher education qualification for nurses proposed; supernumerary status for nursing students |

| 1989 | Review of pay scales | Clinical grading structure for nurses introduced |

| 1990 | Working for patients; purchaser/provider | Financial performance prominent in healthcare |

| 1997–1999 | The new NHS: modern, dependable (DH 1997) | Expansion of the nursing workforce |

| Strengthening of nursing leadership | ||

| A first class service: quality in the new NHS (DH 1998a) | Clinical governance – corporate accountability for the quality of care | |

| Widening access to nursing education, common foundation programme followed by branch programmes | ||

| Making a difference (NHS Executive 1999) | ||

| Fitness for practice (UKCC 1999) | ||

| 2000 | The NHS plan (DH 2000) | Outlined healthcare reforms which would lead to extra beds, more hospitals, modernized GP urgeries, more consultants, more nurses, more IT support, better food and cleaner wards |

| 2002 | UKCC becomes Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) | The principal functions of the Council shall be to establish from time to time standards of education, training, conduct and performance for nurses and midwives and to ensure the maintenance of those standards |

| 2004 | Agenda for change | Modernized NHS pay system with new pay bandings, job evaluation scheme and knowledge and skills framework |

| 2005 | Reduction in junior doctors’ hours; review of nurses’ roles | Nurses increasingly undertaking advanced roles |

| 2006 | Reorganization of NHS structures | Redundancies amongst NHS staff including nursing posts |

| Some NHS trusts report financial overspends | Nurses speak out against the speed of reorganization and policy implementation, arguing that the change is detrimental to patient care |

Approaches to nursing practice

This section outlines holistic care and patient centredness and then explains the four main approaches to organizing nursing care.

Holistic care

Caring that involves looking after the ‘whole person’ is truly holistic and healing. Holistic care recognizes the uniqueness of each human being, their individuality, personality and human frailty (Makinen et al 2003). It can be argued that every nurse knows that the subtle process of caring has physical, psychological, social and spiritual dimensions but that this is often hard to express in words. It involves the integration and coordination of inter-personal, technical and professional skills that results in a complex network of interactions that contribute to successful nurse–patient relationships (Adams et al 1998). Holistic care (see also Ch. 1) therefore requires nurses to think beyond the concept of cure which is based on scientific facts and technical competence.

Person-centred care

Nursing is moving in this direction with increasing emphasis on therapeutic relationships with patients/clients and making changes in care delivery that give patients/clients more power and choice, and pays more regard to their needs and wishes (Salvage 2002). Recently, holistic care has been developed further to embrace the concept of person-centredness (Box 2.6). This is concerned with the rights of people to have their values and beliefs as individuals respected, i.e. their personhood (McCormack 2003). It is said that it is these values that give people their uniqueness and authenticity. Maintaining person-centredness is now central to decision-making and determining the actions of all healthcare professionals in their practice.

[After McCormack 2003]

Person-centredness involves respecting the rights of each person to make rational decisions, to determine their own goals and to enable them to reach their own decisions. This involves:

The principles of person-centredness can be applied across health and social care settings and all branches of nursing. Everyone experiencing healthcare is on a journey or pathway of care that involves new situations so uncertainty is to be expected. Uncertainty can be challenging but it also provides opportunities for learning and solutions, resolutions and outcomes that, with the appropriate support, can be uniquely created and tailored to meet individual needs.

Involving users and carers

The patient/client/carer (or consumer) is the most important person in the healthcare system. The nurse has an important role in ensuring continuity and maintaining consumer autonomy (the ethical principle that individuals should make their own decisions about their lives) within the maze of the healthcare system, which can be challenging. This may include helping the consumer to:

This helps to reduce feelings of anxiety and isolation. Patient/client/carer involvement has become the norm in contemporary nursing practice as it promotes patient decision-making and partnership working, ensuring that services provided meet the service user’s needs (DH 2004). This approach considers service users as experts in their own lives and also often in their disease/condition, i.e. it encourages expert patients to manage their own chronic condition. People’s perceptions of what constitutes quality care are formed by their encounters with an existing care structure and by their expectations and experiences (Larsson & Larsson 2003).

Contemporary health and social care provision encourages bridging the hospital/community divide through delivery of more flexible and seamless services, including intermediate care, that are built round the patient care pathway rather than institutions or budget systems.

Approaches to organizing nursing care

There are four approaches that have been used and elements of these underpin nursing practice in most settings today.

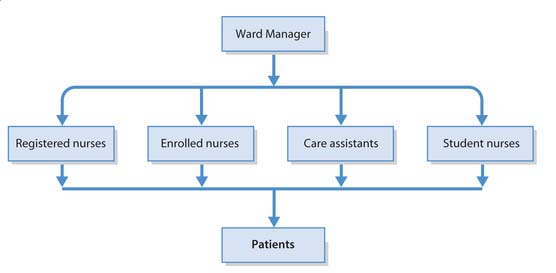

Task allocation

Task allocation was the main method of organization when hospitals were established and still persists to some extent in many areas of nursing (Fig. 2.1). Where it continues, this is usually due to autocratic leadership styles (see Ch. 9) and the continuing use of the biomedical model (see p. 43 and Ch. 1). Task allocation is based on a hierarchy of tasks where tasks are carried out according to the status of the caregiver and has much in common with an industrial production line, with each carer carrying out a limited range of care-related tasks for many patients/clients. It also reflects the hierarchical, ecclesiastical and military roots of nursing that value obedience and subservience. For example, in a hierarchy, tasks are allocated by seniority where:

Patient allocation

This was introduced in the 1970s to enable nurses to focus on caring for individual patients/clients rather than on a range of tasks. Nurses were allocated specific patients to care for. The aim was to provide continuity of care; however, both the nursing hierarchy and relationships between charge nurses and other nurses remained the same and essentially task allocation continued but for smaller groups of patients/clients.

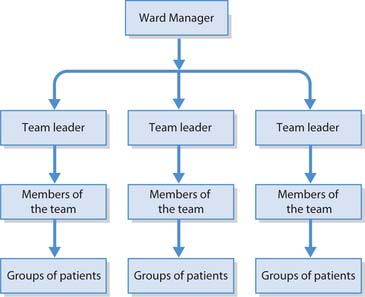

Team nursing

In 1956, the RCN developed a theory of team nursing but a number of issues prevented this approach being developed:

However, during the 1980s, team nursing evolved and allowed care to become more individualized. Nurses are allocated to a team who provide care to a specific group of patients/clients (Fig. 2.2). The team leader shares responsibility for patient care, communication and coordination with the ward manager. Ideally, the same team cares for the same group of patients for the duration of their stay. This increased continuity of care provides more meaningful work for nursing teams.

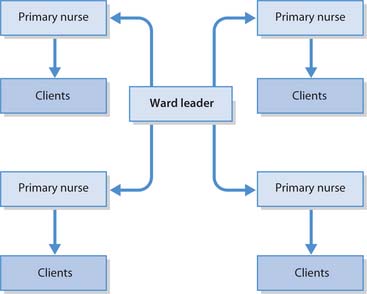

Primary nursing

This involves patients/clients being allocated to an individual RN rather than a team of nurses (Fig. 2.3). The focus is on individual holistic care, where the participation of patients/clients and relatives is encouraged. The primary nurse has 24-hour responsibility for their group of patients, known as a caseload, throughout their stay. Primary nurses have the knowledge and ability to make decisions, and also the authority to carry them out. In the primary nurse’s absence, an associate nurse, another RN or primary nurse carries out the planned care with the involvement of students and HCAs. In settings where primary nursing is practised, the sister/charge nurse acts as consultant, role model (managing a small caseload), ward manager and in-service educator. In common with other care delivery systems, primary nursing has advantages and disadvantages (Box 2.7).

Box 2.7 Advantages and disadvantages of primary nursing

[After Sparrow 1986]

Advantages

Care delivery in practice

It has been recognized that when team or primary nursing is used as a method for organizing patient care, less stress is reported by the practitioners involved. Alongside this, there is the belief that patients feel better cared for and their individual needs are met, practice is enhanced, teamwork is more evident and there is greater job satisfaction.

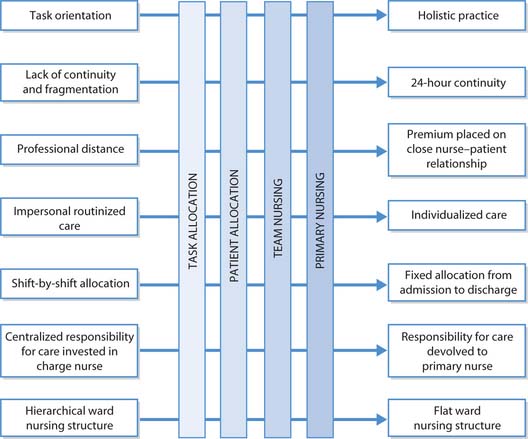

Figure 2.4 summarizes the key characteristics of the four approaches to organizing care. There is growing evidence that nurses do not work in the four ways described above, but that care settings are organized in more complex ways using attributes from more than one of the different approaches to care delivery (Adams et al 1998) (Box 2.8). It is interesting to note that patients’ perceptions of the quality of care are often dependent on individual nurses rather than the system of care delivery (Jupp 1994).

Fig. 2.4 The key characteristics of the four main ways of delivering nursing care (after Adams et al 1998)

Contemporary nursing

This section explores the fundamental role of the nurse, how society influences nursing and contributes to the development of nursing in different settings and the role of the nurse as a member of the MDT. In addition, there is consideration of how nurses and nursing continue to influence policy and practice in health and social care by responding positively to the needs of society and the requirements of health policy.

Nursing today

The fundamental role of the nurse is about ‘caring’, which involves spending time with the person promoting health or supporting those who are ill, distressed or disturbed by disease or injury (Box 2.9). It involves demonstrating a capacity to observe, listen and think about individual patient’s/client’s needs, being able to engage them in a way that enables the nurse and the patient/client to work together to reach an understanding of the problems from the patient’s/client’s own perspective before identifying ways by which these can be addressed. It is important also to recognize that cure is not always an attainable goal.

[Resource: International Council of Nurses 2004 The ICN definition of nursing. Online: www.icn.ch/definition.htm Available: July 2006]

ICN definition of nursing

Nursing encompasses autonomous and collaborative care of individuals of all ages, families, groups and communities, sick or well and in all settings. Nursing includes the promotion of health, prevention of illness, and the care of ill, disabled and dying people. Advocacy, promotion of a safe environment, research, participation in shaping health policy and in patient and health systems management, and education are also key nursing roles.

Student activities

After reading the ICN Definition of Nursing, look back at Henderson’s definition (p. 44) and:

Nurses remain the core of the NHS workforce and are essential in maintaining services on a 24-hour basis. Role changes are emerging from the demand for high quality care in response to patients’/clients’ needs and there are numerous opportunities for motivated RNs to lead innovative services that cross the boundaries of hospital and community settings, following patient journeys, providing continuity and ensuring a seamless service for those in their care. A nurse from any branch can be a practitioner, manager, researcher, educator, coordinator of services and health promoter, all within the same shift. These diverse roles put a nurse in a unique position to influence healthcare that is responsive to individual needs. In order to fulfil such diverse roles, special attributes are needed:

Influences on nursing today

The future of nursing holds a myriad of challenges, which include external forces as well as influences from within the profession as the role of the nurse evolves further. External factors that will continue to influence healthcare and nursing include increasing technology, demographic changes, changing patterns of disease, consumerism and increasing recognition of people’s rights, e.g. the Human Rights Act 1998 (see Ch. 6), safety at work, globalization and the impact of increased travel.

Technology

Technological advances, e.g. in telecommunications and imaging techniques, are shaping the ways in which nurses work. To measure up to the future needs of the profession, nurses must be computer literate and able to embrace the new technologies and ways of working. Patients’ records are being computerized and patient data are becoming available via information systems, e.g. laboratory results, prescriptions and integrated care pathways (ICPs, see Chs 3 and 14). ICPs enable healthcare professionals in any setting to document care against agreed standards, not only to monitor patients’ health but also the performance of individuals and teams.

Demography

In mid-2004 the UK population was 59.8 million people (National Statistics Office 2004) with an average age of 38.4 years; one in five people in the UK was under 16 and one in six was aged 65 or over. As a result of declining fertility rates and increasing life expectancy, the UK has an ageing population. International migration into the UK from abroad has been an increasingly important factor in the population change. In response to this, healthcare has to develop new ways of working; for example, to increase the expertise and partnership working with frail older adults and to promote understanding of other cultures and changing disease patterns. With the breakdown of the extended family and the increased need to demonstrate status through the acquisition of material possessions, people are becoming more isolated and stressed.

Changing disease patterns

Modern healthcare and medical technology have begun to transform the health of the nation and life expectancy for many has increased but not to the same degree in all social groups (see Ch. 1) and geographical areas. The development of vaccines has dramatically improved health by reducing mortality and morbidity from infectious diseases. People are less physically active and are eating more sugar and fat and insufficient fresh fruit and vegetables, which has led to increasing obesity. This is also contributing to the increased incidence of chronic conditions such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease and cancers. Chapter 1 discusses the UK Government health targets that have been devised as a focus for health promotion and aim to reduce the incidence of these common and largely preventable conditions.

Smoking is the greatest preventable cause of illness and premature death and despite an overall fall in prevalence (DH 1998b) there is an increase among younger people (DH 1998c). Adolescent pregnancy is a major cause for concern, as is the increased incidence of drug and alcohol misuse and other mental health problems (The Scottish Office 1999).

Consumerism

The users of health services today are sophisticated and informed, having been educated by the media, advertising campaigns and other spheres of consumer behaviour. There is much more interaction between healthcare consumers (patients/clients/parents) and healthcare providers than in the past. Over time, patients/clients have been transformed into consumers whose perceived needs, wishes and expectations influence the delivery of healthcare. It appears that health is an important concern of all age groups, that many individuals see themselves as responsible for their own health and that people are more actively taking control of their healthcare. Those people with an internal locus of control, who take responsibility for their own health, are usually well informed, educated and articulate, and among the healthiest groups in society, whereas those groups with the poorest health may have an external locus of control where they feel that they have little or no control over health and well-being.

Diversity and equity

Diversity is about recognizing and valuing human differences for the benefit of patients/clients, carers, staff and the public at large. Diversity goes hand in hand with equity and equality, which is about creating a fairer society in which everyone can participate and has the same opportunity to fulfil their potential. In reality, there is no equity or equality of opportunity if differences cannot be recognized and valued (Scottish Executive Health Department 2005).

Human rights

People’s rights have become more widely acknowledged, particularly since the passing of the Human Rights Act in 1998 (see Ch. 6) and the European Union Social Charter. These have wide-ranging implications for the profession as they impact on nursing practice and nursing research. Examples include conscientious objection, age and disability, right to life, patient advocacy, role expansion, healthcare resource allocation, emergency contraception, do-not-resuscitate orders, rights to privacy and dignity, confidentiality and anonymity, ethics, genetics and informed consent, advance directives (called advance decision to refuse treatment in the Mental Capacity Act 2005) and patients’/clients’ right to choice (see Chs 6, 7).

The healthcare system must challenge discrimination, promote diversity and respect human rights. It is not uncommon for certain groups of people to be discriminated against, including older adults, drug users, homeless and unemployed people, minority ethnic groups and those with mental health problems. In practice, diversity should mean that all people are treated as equal and can access free healthcare at the point of need.

Nursing in different settings

In response to societal influences new nursing roles have developed in different settings. Society has changed and a new approach to healthcare is needed. Health choices will be made easier by providing better information and advice. This means developing the talents, commitments and strength among nurses to ensure they maximize their contacts with patients, clients and local communities to make every contact a health-promoting opportunity wherever they work, be it in the community, at home, GP surgeries or hospitals.

Roles in the community

The National Health Service and Community Care Act (1990) has led to significant changes in the place of care delivery, heralding a move from largely hospital-based provision to care within community settings (see Ch. 3). The emphasis on community services will further increase with the implementation of the English White paper Our Health, Our Care, Our Say: a New Direction for Community Services, which provides for a shift of resources from hospital- to community-based services (DH 2006). Nurses are increasingly the first point of contact for patients/clients, whether in NHS walk-in clinics or via NHS direct (England and Wales) or NHS 24 (Scotland). In addition, nurses are increasingly taking a lead in providing services for some people with mental health problems and chronic physical health conditions. These services tend to focus on the health of the patient/client, rather than their illness, and are largely community based. Nursing roles in the community include those of specialist community public health nurses (school nurses with specialist practice qualifications, HVs and occupational health nurses) and community practitioners such as district nurses, community mental health nurses (see Ch. 3) and community learning disability nurses. Some of these roles are discussed below.

School nursing

School nurses provide an essential link between schools, home and the community, which helps to safeguard the health and well-being of children and young people. In order to do this they work with children/young people, parents/carers, teachers and a multidisciplinary team (MDT) of other health and social care professionals. Their responsibilities include supporting children with complex health needs, immunization and drop-in clinics, assessing the health needs of every 5-year-old and providing health promotion programmes for young people, e.g. on health issues such as safe sex, stress management, discrimination and bullying.

Health visiting

HVs focus on health and social needs, working in collaboration with other NHS disciplines and other agencies. Their clients include children and mothers, families, older adults and marginalized groups including asylum seekers and travelling people.

The HV undertakes health promotion activities. This may include assessing the health needs of children in the community to identify vulnerable groups and provide effective programmes of support and care that will protect and promote health and well-being. HVs work with social workers and others to safeguard children by identifying if they are vulnerable, i.e. their safety or welfare is at risk. They also deliver public health programmes that address national and local health priorities such as reducing inequalities, smoking cessation and tackling obesity. They help healthy people to stay well and ill people to come to terms with their illness. They generally have a caseload of clients of one age group, usually children, but some have caseloads of older adults and people with other needs.

Public health nursing

Specialist community public health nurses aim to reduce health inequalities by working with individuals, families and communities to promote health, prevent ill-health and protect health. The emphasis is on partnership working that cuts across disciplinary, professional and organizational boundaries that impact on social and political policy to influence the determinants of health (see Ch. 1) and promote the health of whole populations (NMC 2004b). The HV role may evolve and develop through further education to become this newly defined practitioner.

Family health nursing

The World Health Organization Europe (2000) proposed a new type of nurse that would be based in local communities. The envisaged role of this family health nurse (FHN) was multifaceted and included helping individuals, families and communities to cope with illness and to improve their health. The FHN and the family health physician were presented as the key professionals at the hub of a network of primary care services.

In 2001, the Scottish Executive Health Department saw this as a potential solution to some of the problems of providing healthcare in Scotland’s remote and rural regions and undertook a pilot project which was then evaluated (Scottish Executive Health Department 2003). This role is still in its infancy and further development and evaluation are required.

District nursing

District nurses (DNs), also known as community nurses, provide nursing care for people of all ages in a variety of non-hospital settings including patients’ homes, GP surgeries and residential nursing homes. Their work involves, for example, health assessments and health promotion, wound management, administering medication, risk assessment and palliative care. It may also involve running clinics for people with chronic conditions such as diabetes. DNs often manage a caseload of patients and they work with other healthcare professionals in supporting patients’ families and carers.

Hospital nursing

In hospitals many nurses are expanding their roles to meet demands for increasingly complex care needs based on innovative technologies and to compensate for a shortage of medical staff. Many RNs, along with midwives and therapists, undertake a wide range of clinical activities including the right to make and receive referrals, admit and discharge patients, order investigations and diagnostic tests, run clinics and prescribe drugs.

Intermediate care

Intermediate care is sometimes required on discharge from an acute hospital for patients who cannot return home immediately and require some form of rehabilitation. These are often GP beds in a community hospital. Increasingly, nurses work across hospital and community settings, an example of which is the clinical nurse specialist role (see p. 66).

Nurses as members of a multidisciplinary team

The multidisciplinary approach is increasingly recognized in healthcare as a valuable way of working. Nurses are often part of a MDT that may include doctors, physiotherapists, pharmacists, dietitians and many other health and social care professionals (see Ch. 3). It is important to understand the roles of all the members and how they interlink to provide ‘seamless’ healthcare.

The key to multidisciplinary care is collaboration, the coming together of different health and social care professionals as partners to develop a collective understanding, which requires effective coordination, a flattened hier-archy and transformational leadership style (West 1994). The following characteristics are outcomes by which success can be measured:

Effective teamwork within the MDT

Teamwork is about working together and requires cooperation and understanding (see Ch. 9). The readiness to develop a collaborative approach is recognized by a group’s capacity to experience and manage competition, conflict, risk and stress, and their willingness to communicate (Rowe 1996). Team members must be aware that their behaviour not only affects others but also the overall performance of the team. The aim should be to adopt the helpful roles outlined in Table 2.2. Moving towards the helpful behaviours involves self-awareness and a team with members who are ready to change and learn from others (see Ch. 9).

Table 2.2 Helpful and hindering roles in team working

| Helpful roles | Hindering roles |

|---|---|

| Establishing: | Aggression: |

| Persuading: | Manipulation: |

| Committing: | Dependence: |

| Attending: | Avoidance: |

Adapted from Hersey & Blanchard (1988).

However, effectiveness is not down to individuals alone. An effective team requires skilful coordination which West and Field (1995) argue involves:

Carrying out the activities in Box 2.10 will help you to understand the characteristics of effective teamwork.

Becoming a nurse in the 21st century

The present education of nurses has been influenced by many factors, not least public expectation and scrutiny of what has gone before. The major changes have involved the educational outcomes at the point of registration. This section discusses a number of issues including pre-registration nursing programmes, the NMC outcomes and proficiencies, the role of the HCA and National Vocational Qualifications (NVQs).

Pre-registration nursing programmes

The new direction for the nursing profession, established in the wake of Project 2000, brought a profound shift in ethos and culture. Following a review of nursing education, the UKCC (1999) recommended measures that would enable fitness for practice through better preparation of student nurses which was to be based on healthcare need. There was also a move to ensure that placement experience and mentors prepared competent practitioners who were able to provide safe care. This resulted in the development of proficiencies for pre-registration nursing programmes. Two major changes were:

Nursing programmes now include a common foundation programme, which is followed by one of four branch programmes:

The NMC has a responsibility to ensure that registered nurses, midwives and specialist community public health nurses provide high standards of care to their patients and clients. To this end, the NMC (2004c) has set out CFP outcomes necessary for entry into a branch programme and the standard of proficiency that must be achieved prior to registration (Table 2.3). They are described under four domains:

Table 2.3 Standard 7 – First level nurses – nursing standards of education to achieve the NMC standards of proficiency

| Domain | Outcomes to be achieved for entry to the branch programme | Standards of proficiency for entry to the register: professional and ethical practice |

|---|---|---|

| Professional and ethical practice | ||

| Domain | Outcomes to be achieved for entry to the branch programme | Standards of proficiency for entry to the register: care delivery |

|---|---|---|

| Care delivery | ||

| Domain | Outcomes to be achieved for entry to the branch programme | Standards of proficiency for entry to the register: care management |

|---|---|---|

| Care management | ||

| Domain | Outcomes to be achieved for entry to the branch programme | Standards of proficiency for entry to the register: care management |

|---|---|---|

| Care management | ||

| Domain | Outcomes to be achieved for entry to the branch programme | Standards of proficiency for entry to the register: personal and professional development |

|---|---|---|

| Personal and professional development |

Reproduced with kind permission of the Nursing and Midwifery Council (2004).

Common foundation programme

All nursing students undertake the same CFP. This is because all branches of nursing share common skills and knowledge. The CFP lasts for 1 year and the main areas of study are:

This book explores all these areas in sufficient depth to enable you to learn about them with examples that relate to each branch of nursing. The relevance to clinical nursing practice is reinforced throughout the CFP and half of the programme takes place in clinical settings. All students undertake placements that reflect nursing as it applies to the care of adults, children, people with mental health problems and those with learning disabilities. Before progressing to a branch programme, the NMC outcomes (NMC 2004c) (see Table 2.3) must have been met.

Branch programmes

Branch programmes last for 2 years and, like the CFP, are half theory and half practice. The theoretical subjects studied are the same as during the CFP, but they are applied to the different branch programmes and include more detailed knowledge that underpins the more specialized care provided by RNs. Before registration, students are required to demonstrate achievement of professional standards of proficiency (see Table 2.3) and complete a self-declaration of good health and good character (NMC 2004c).

Branches of nursing

The main differences between the current branches of nursing are explored below. While most nurses undertake only one branch of nursing, the patient/client boundaries are not mutually exclusive; there is therefore a need for all RNs to have an understanding of each of the branches. For example, both adult and children’s nurses will encounter clients with learning disability when they access primary healthcare through GP surgeries or require admission to hospital, and mental health nurses may have clients with coexisting physical conditions such as diabetes, chronic bronchitis or leg ulcers.

Adult nursing

Adult nurses are primarily responsible for health promotion and providing holistic care for physically ill or injured adults with wide-ranging levels of dependency in both hospital and community settings. The focus is on the individual patient, rather than the condition from which they may be suffering; and the needs and anxieties that their condition may generate, including the pressures on their family and friends.

Adult nursing placements include care homes, hospital wards and specialist clinics, and community placements that may involve visiting people at home or attachments to health centres. Nurses play an increasingly prominent role in the provision of health-focused care in the community. Many hospital-based nurses are found in specialist areas such as intensive care, cancer care and care of older adults (Table 2.4). Adult nurses work with people over 18 years of ages who have acute (short-term) and chronic (long-term) conditions.

Table 2.4 Some adult nursing specialties

| Specialty | Focus of care |

|---|---|

| Palliative care (see Ch. 12) | Holistic relief of symptoms such as pain or breathlessness (rather than effecting a cure), support for patients and their families and friends. This is often, but not necessarily, for people with cancer |

| Accident and emergency nursing | Any presenting problem that requires urgent intervention |

| Women’s health (gynaecology) | Women requiring health screening, family planning, sexual health advice and interventions involving the reproductive organs |

| Orthopaedics | Maximizing mobility and independence in people with bone problems such as fractures, congenital bone malformations |

| Older adults (gerontology) | Holistic approach to problems which are often multiple or specific conditions which tend to become increasingly common with age |

| Ophthalmic nursing | Problems affecting the eye and vision |

| Dermatology nursing | Conditions affecting the skin, which often affect body image (see Ch. 11) |

| Cancer nursing (oncology) | Helping people to cope with the diagnosis of and treatment for cancer and any related nursing problems |

| Rehabilitation (see Ch. 11) | Assisting people to achieve optimal functioning and reduce the risk of mortality/morbidity through health promotion |

| Cardiology (see Ch. 17) | Caring for people with heart disorders, supporting families with a child with a congenital heart defect, cardiac rehabilitation |

| Perioperative care (see Ch. 24) | Nursing care required before, during and after surgery |

Despite the wide range of specialties, there are a number of features common to most adult nursing roles (Box 2.11). While this often includes physical care, it extends well beyond that, including counselling, advice and education that draws upon interpersonal and communication skills to address psychological, social and spiritual aspects of holistic care.

Rehabilitation nursing

As a primary nurse (p. 49), Sandra is the RN responsible for every aspect of nursing care for a group of eight older adults on a rehabilitation ward, who are cared for in two bays of four beds, one male and one female. She directs the work of associate nurses (p. 49), who are less experienced and assist with care delivery. Sandra is accountable for patient care, i.e. she ensures that the care is of good quality and appropriate to patients’ needs. Today Sandra’s patients range in age from 69 to 84 and present a variety of nursing problems due to their underlying medical conditions:

Sandra begins her day by reading the notes made by the night staff about her patients’ progress and reflecting on the care they have received. Next she visits each of the patients with the associate nurse, taking the care plans along with her. The purpose of the visit is to discuss the day’s care with each patient and to agree the priorities that will meet their needs. Sandra knows from nursing research that it is good practice to involve patients and their families in decisions about their care (Bakalis & Watson 2005).

Most patients have specific problems but can eventually look forward to an independent future. The nurse’s role is to offer support while it is needed and give people the skills, strength or knowledge that will help them to regain independence. Box 2.12 provides the opportunity to consider the types of health-related problems that people may experience as a result of sudden illness and change in independence.

Learning disability nursing

Health policy in the UK is explicitly directed at social inclusion and social justice for all citizens. This policy is clearly outlined in Valuing People (DH 2001) and The Same as You? (Scottish Executive Health Department 2000a). These documents state that people with learning disabilities should be respected and valued and afforded the same opportunities as others, as well as receiving additional support and services to meet their individual needs.

In Scotland the policy around promoting health and supporting inclusion for people with learning disabilities has developed considerably over recent years. As there are, as yet, no similar developments elsewhere in the UK, it is useful to examine how policy and practice in Scotland has been developing. Caring for Scotland is the strategy for nursing and midwifery in Scotland (Scottish Executive Health Department 2000b). This strategy outlined the intention of the Scottish Executive to undertake a review of the contribution of all nurses and midwives to the care and support of people with learning disabilities. Promoting Health, Supporting Inclusion was published by the Scottish Executive in 2002 and details the actions required from all nurses and midwives to improve the health and well-being of children, adults and older people with learning disabilities in Scotland. Recommendation 1 of Promoting Health, Supporting Inclusion invited NHS Health Scotland, Scotland’s national health improvement organization, to undertake a strategic needs assessment of the health needs of children, adults and older people with learning disabilities. This comprehensive health needs assessment was published in 2004 and details the inequalities that require to be addressed strategically and locally in order to promote social justice for this group of Scottish citizens (NHS Health Scotland 2004). Thus it is evident that these health inequalities need to be redressed so that people with learning disabilities can indeed be included in our society in an equitable, respectful and dignified fashion.