Chapter 10 Sleep, rest, relaxation, complementary therapies and alternative therapies

Introduction

Maslow’s hierarchy of basic human needs comprises five or seven levels. The first level physical/physiological needs, such as food and water, are necessary for life. These physiological needs, which also include sleep and rest, have the greatest priority.

Sleep, relaxation and rest maintain, enhance and restorethe person’s physiological, psychological and social well-being. Nurses in all care settings are involved in helping and guiding people to attain optimum health and well-being. An important aspect of this is to promote daily routines and lifestyle that enables the individual to enhance the body’s normal way of achieving rest by relaxation and sleep. The nurse’s role is especially important during illness or following injury when the restorative functions of sleep are most needed for reducing stress and promoting healing. Unfortunately, many patients/clients have problems getting sufficient rest and sleep, particularly so in hospital. Inadequate sleep and rest may, for example, be caused by anxiety, pain, the environment or specific treatments.

The first part of the chapter provides an overview of sleep, including physiological control, the sleep stages and functions. The factors that cause disturbances of sleep, effects of sleep deprivation and some specific sleep disorders are addressed.

The nursing interventions employed to promote rest and sleep throughout the lifespan are discussed in some depth and include the assessment of sleep, sleep hygiene/pre-sleep routines and the sleep environment, and the role of relaxation, orthodox medications and herbal products in promoting sleep. The outline of relaxation (see Ch. 11) and herbal products used in relation to rest and sleep provides a link to the section about complementary and alternative medicine (CAM).

In the last part of the chapter the integration of complementary and alternative therapies with conventional healthcare is discussed. There is information about the use of some therapies and how they can be accessed and utilized safely to promote rest, relaxation and sleep. In addition, some examples of the wider uses of CAM are provided.

Sleep, rest and relaxation

Sleep, rest and relaxation, as already stated, are necessary for well-being and health maintenance. Sleep is an altered state of consciousness, accompanied by a reduction in metabolism and skeletal muscle activity. It occurs naturally in humans and follows a 24-hour biological rhythm (see below).

During sleep, the arterial blood pressure, heart and respiratory rates all decrease and skin blood vessels dilate. It has long been accepted that sleep is important for restoration and repair of cells and tissues. Growth hormone (GH) secretion increases during sleep and cell division in many tissues takes place.

However, there is evidence that, apart from the brain, all other organs undergo just as effective restoration during relaxed wakefulness (Horne & Reyner 1988, 1997). This highlights the importance of relaxation and rest periods during the day, e.g. breaks from work and the need for relaxation and relief from anxiety. Babies and children need a balance between active play, restful relaxed activities such as sitting on a carer’s lap to listen to a story and sleep.

Protected time for rest and relaxation is important for patients/clients in hospital and other care settings. People can become exhausted by long visiting hours and the interventions from health professionals that are intended to restore health (Box 10.1).

Protected rest times

Periods of rest and relaxation are important for everyone but particularly so during illness.

Sleep is also thought to help revitalize mental activities such as learning, memory, reasoning and emotionaladjustments. Studies of junior doctors working extended shifts indicate that they have concentration lapses and make more serious errors than when their shift length was curtailed to less than 16 hours (Lockley et al 2004).

Biorhythms

Biorhythms are the cyclical patterns of biological functions unique to each individual, e.g. sleep–wake cycles, fluctuations in body temperature, blood pressure, heart rate, mood and some hormone secretion. Biorhythm cycles may follow a 24-hour day–night (circadian) pattern or a longer period such as a woman’s menstrual cycle.

The sleep–wake cycle is a good example of a physiological process that follows a circadian (Latin: circa [about] and dies [day]) or diurnal daily pattern. A ‘biological clock’ synchronizes the sleep–wake cycle with the 24-hour clock, which people use to determine daily and social activities. It follows a day–night/light–dark rhythm of around 24 hours, thus giving rise to individual sleep patterns and different times for going to bed such as 20.00 hours, midnight or even the early hours of the morning.

Physiology of sleep

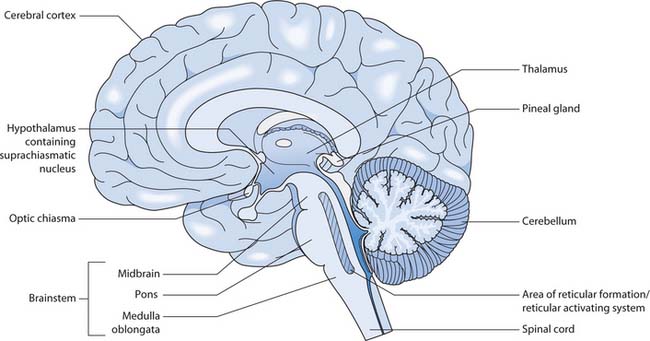

The physiological control of sleep involves a functional area in the brain, the reticular formation (RF), sometimes known as the reticular activating system (RAS), other brain structures, neurotransmitters (chemicals) and the hormone melatonin (Fig. 10.1). An outline is provided here and readers requiring more detail should consult Further reading (e.g. Montague et al 2005).

When a person is asleep, the body is relaxed and they are not conscious of external stimuli such as noise or internal stimuli such as hunger. The stimulating mental activity such as thoughts about events of the day or preparatory work for the next day diminishes as the person begins to feel drowsy and falls asleep. However, if these stimuli are very intense and strong the person wakes up and consciously responds to the stimuli. The sensory nerve pathways receive and convey nerve impulses upwards to the cerebral cortex (‘conscious brain’). They arise in response to stimuli such as light, noise, pain, temperature and hunger. Likewise, descending messages from the cerebral cortex enable the person to respond accordingly, e.g. getting up to have a snack if hungry or lying awake thinking of a solution to a problem. It appears then, that the balance of impulses to and from the cerebral cortex controls the sleep–wake cycle.

Reticular formation – the reticular activating system

The RF or RAS is a functional system, which comprises diffuse neurones found throughout the brain stem (midbrain, pons and medulla oblongata). It has connections with the cerebral cortex, thalamus, hypothalamus, cere-bellum and spinal cord. The RAS is important in the control of motor activity, some autonomic functions and the regulation of sensory inputs en route to the cerebral cortex.

The RAS controls the sleep–wake cycle, the state of cortical awareness and consciousness. Ascending sensory impulses, e.g. sound and light, stimulate the RAS and this increases cortical activity and the person wakes. Consciousness is maintained through the activity of various feedback mechanisms that involve the RAS, cerebral cortex and skeletal muscles. When the RAS is inhibited, RAS activity is low and the person becomes relaxed and falls asleep. Thus a quiet, dark room promotes sleep, whereas increased stimuli to the RAS increases its activity and the high level of excitation prevents the person from relaxing and falling asleep. Stimulating factors, e.g. anxiety, being upset, hunger, thirst, physical discomfort and noise can prevent sleep. RAS functioning is inhibited by drugs, e.g. anaesthetic agents, sedatives, anxiolytic drugs that reduce anxiety, and by alcohol and nervous system problems.

The biological ‘body clock’

Normally adults sleep at night and stay awake during the day. This timing of sleep that corresponds with darkness and light is what constitutes a circadian rhythm. It is thought that this is controlled by a group of cells called the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) found in the hypothalamus in the brain (see Fig. 10.1). The SCN, identified as the ‘biological clock’, is stimulated by visual information from the retina of the eye. This explains why light is the primary controlling stimulus for the biological clock’s daily rhythm and why humans go to bed at night.

The SCN is connected to the pineal gland situated in the centre of the brain (see Fig. 10.1). The SCN controls secretion of melatonin, a hormone, from the pineal gland. The secretion of melatonin exhibits a 24-hour cycle and fluctuates in relation to light. It appears that darkness stimulates its secretion and light inhibits it. Thus levels ofmelatonin are high at night but low during the day. It is thought that melatonin may play an important role in regulating the sleep–wake cycle. It is noted to be higher in children than in adults and may explain why children sleep more than adults (see pp. 256–257). Ongoing research into the effects of melatonin include:

Seasonal affective disorder

In severe SAD, symptoms may also include:

Student activities

[Resources: Lambert K and Kingsley CH 2005 Clinical neuroscience. Worth, New York; NHS Direct. Online: www.nhsdirect.nhs.uk/he.asp?ArticleID5333 Available July 2006]

Neurotransmitters involved in sleep physiology

There are several neurotransmitters involved in controlling the sleep–wake cycle. These chemicals are produced in the RF and elsewhere in the brain. It is thought that neurotransmitters affect the sleep–wake cycle by influencing the level of activity in the RAS, causing the transition from sleep to arousal to waking and vice versa. Changing levels of neurotransmitters cause the shift from one state to another and give rise to two types of sleep: non-rapid eye movement sleep (NREM) and rapid eye movement sleep (REM) (see p. 254). The neurotransmitters include:

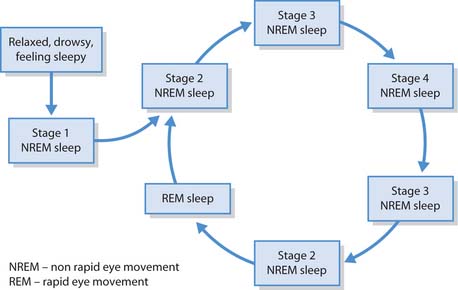

Stages of sleep

There are two types of sleep, named according to whether or not the eyeballs can be seen to move behind the closed eyelids, i.e. NREM sleep and REM sleep. For young adults, a normal night’s sleep of about 8 hours comprises around 70–80% of NREM sleep with the remainder spent in REM sleep. Subjects observed during NREM and REM sleep show distinctive features of brain wave patterns, changes in muscle tone, heart rate and breathing.

NREM sleep

NREM (orthodox) sleep, which occurs first, has four stages. Box 10.3 outlines the characteristics of these stages. Sleep begins with the person relaxed, feeling drowsy and then proceeds from stage 1 to stage 4. This normally takes 40 minutes. The process then reverses, moving back through NREM stages 3 and 2 followed by an episode of REM sleep. If the sleep is uninterrupted, it continues in this cyclical fashion (Fig. 10.2). In adults the cycle repeats four to five times in an average night’s sleep, each cycle lasting about 90 minutes. However, the time spent in stages 3 and 4 declines as the night progresses and more time is spent in REM sleep. The amount of REM sleep differs between age groups and during the individual’s lifespan. In NREM sleep, there is progressive muscle relaxation and reduced muscle tension. Blood pressure, heart and respiratory rates all decrease. The gonadotrophic hormones, whichstimulate the gonads (ovaries and testes), and GH are released during NREM sleep. When awakened during NREM sleep, dreaming is rarely reported.

Box 10.3 Characteristics of the different stages of the sleep cycle

Wakefulness – alert, awake, eyes open, relaxed, drowsy, feeling tired, eyelids getting ‘heavier’, eyes may close, head relaxed, droops, lacks concentration and attention, sleepy but not asleep.

NREM (orthodox) sleep – 50% in neonates, 20% in preschoolers, 70–80% in young adults and variable in older adults:

REM (paradoxical) sleep – about 50% in neonates, 20% in young adults and variable in older adults. This stage normally begins at the end of each sleep cycle. Therefore, REM sleep occurs approximately every 90 minutes, each episode lasting about 10 minutes. The deepest sleep and greatest relaxation occurs and the person is difficult to rouse. Dreaming occurs, rapid eye movements behind closed eyelids, possibly the person is visualizing and following the events of the dream. There is a marked increase in brain oxygen consumption. Blood pressure, pulse and respiratory rates vary more than during NREM sleep.

REM sleep

REM sleep is also known as paradoxical sleep, because the brain wave pattern resembles that of the waking state, but paradoxically the sleeper is difficult to arouse (see Box 10.3). During REM sleep oxygen consumption is high and, when awakened, subjects report that they have been dreaming. REM sleep is associated with an increase in and irregular blood pressure, heart and respiratory rates. There is rapid eye movement. Although twitches of facial muscles may occur, there is loss of skeletal muscle tone throughout the rest of the body.

Functions of sleep

The functions of sleep are not clearly understood, hence there are several hypotheses regarding this. One of these suggests that during REM sleep, dreaming enhances and facilitates the chemical and structural changes that the brain undergoes during learning and memory. Dreams may also provide the expression of concerns in the ‘subconscious’. In one study, soldiers who were woken during dream sleep found extreme difficulty in coping and completing tasks the next day. This demonstrates that dreaming is an important function of sleep, possibly a means of filing away the stimulating experiences of the day (Rottenberg 1992).

Neonates sleep for long periods, probably to recover from the process of birth. During sleep, relaxation of skeletal muscles and a reduction in metabolic processes occurs. This helps to conserve energy and, together with the release of GH, growth and cell/tissue repair such as during wound healing are enhanced (see Ch. 25).

The proper functioning of the immune system is also linked with sleep. For example, interleukin-1 (a signalling protein produced by some white blood cells), which has an important role in the inflammatory response (see Ch. 25), fluctuates in parallel with normal sleep–wake cycles (Widmaier et al 2005).

Effects of sleep deprivation

Most, if not all, nurses can relate to the effects of not enough sleep such as lack of concentration, irritability and poor performance of skilled tasks (Box 10.4). An increase in accidents, e.g. driving home after night duty, and domestic and work-related accidents due to impaired judgement and human errors are all related to sleep deprivation.

Sleep deprivation

Think about times when you have not had enough sleep for whatever reason.

Sleep deprivation is associated with reduced function of the immune responses, thereby reducing the individual’s resistance to infection. It may also induce mental health problems and even psychotic behaviour if it is accompanied by stress.

The effects of sleep deprivation vary from person to person and some examples are outlined in Box 10.5. These effects can become problematic and may cause the individual to seek help. If poor sleep habits are not resolved they can develop into a chronic problem such as insomnia (see p. 261). The most effective treatment for sleep deprivation is elimination or correction of factors that disrupt sleep patterns. Nurses should be proactive in helping the person to achieve and retrieve lost sleep.

Factors that affect normal sleep patterns

A person’s normal sleep pattern is determined by factors that include:

Cultural influences on sleep patterns

Consider the cultural influences on the sleep patterns of an adult patient/client.

Box 10.7 provides an opportunity to consider your own sleep pattern and the factors that influence it.

Sleep patterns during the lifespan

Normal sleep patterns change throughout the lifespan in order to meet the different requirements during growth, development and maturation. The amount of sleep required by a newborn baby is very different from that needed by an older adult. The duration, quality and quantity of sleep are all subject to change, not just the time spent sleeping (Fig. 10.3).

Infancy and childhood

In the first week of life, infants are usually asleep for 16 hours out of the 24 hours, but this is interspersed withwaking for frequent feeds. Establishing a sleep pattern is important and a pre-sleep bedtime routine can be introduced as early as 6 weeks. This helps the infant to learn the ‘sleep cues’ and enhances settling down at bedtime (Box 10.8).

Helping infants to sleep at night

You are on a community child health placement and many parents/carers have told the health visitor that they cannot get their baby to sleep at night or that the baby seems to cry excessively.

Student activities

[Resources: Cry-sis – www.cry-sis.org.uk/sleepproblems.html; NHS Direct Babies crying – www.nhsdirect.nhs.uk/en.aspx?articleID5645; Parentline New baby and sleep – www.parentlineplus.org.uk/index.php?id5123 All available July 2006]

By the age of 3–4 months a pattern of sleep begins to develop and infants sleep around 8–10 hours during the night and wake up early in the morning. Normally infants and toddlers have sleeps during the day but the duration reduces and eventually ceases when the toddler reaches the age of 3 years. However, those who are more active will sleep less. Sleep disorders affecting children are outlined later (see pp. 261–262).

Once the child starts school, the amount of daily activity and the overall health of the child will dictate how many hours of sleep are required. Children aged between 4 and 5 years spend, on average, about 10–11 hours sleeping at night.

Adolescents/young adults

Adolescents and young adults need sufficient sleep to cope with the period of rapid growth that occurs. Most young people are engaged in physical and mental activities at school, college or work and socializing in the evenings and at the weekend. Normally by bedtime, they should have no difficulty falling asleep. However, it is normal for those who extend their activities past midnight to sleep on in the mornings, especially at weekends when they may sleep until lunchtime. An average adolescent sleeps 8–9 hours per night but this will vary according to the demands of study, socializing, sport, part-time work, etc.

Adulthood and midlife

During adulthood and midlife sleep requirements vary between individuals. Some people may need 10 hours whereas others need as little as 4 hours of sleep at night. Some women find that their sleep patterns change during the time around the menopause. Sleep may be disrupted by hot flushes and night sweats.

Older adults

In common with other age groups the sleeping patterns and sleep requirements of older adults vary considerably. It is a misconception that older people require less sleep. In fact, the total amount of sleep does not change as age increases. However, the time spent sleeping at night decreases because people wake more often during the night. But the loss of nighttime sleep is offset by an increase in daytime naps and rest time. Also, the quality of sleep deteriorates, as there is a progressive decrease in REM sleep and NREM sleep (stage 4).

The fragmented sleep patterns in older adults may be explained by changes in sleep regulation due to age-related alterations in the circadian rhythm of melatonin secretion. There are changes in both the amount and timing of melatonin rhythm (Skene & Swaab 2003). There may be reduced sensory stimuli and less awareness of time. Patients with dementia are particularly likely to experience changes in sleep patterns and circadian rhythms (Box 10.9).

Sleep patterns in dementia

Frank has dementia and lives with his daughter. She tells you that he does not seem to know whether it is day or night. It is increasingly difficult to get him to go to bed and he wanders about the house at night.

Chronic illnesses may also interfere with the regulation of sleep and also reduce sleep quality. For example, people who suffer pain due to arthritis may find it difficult to get comfortable or they are woken by pain. Medication may affect sleep patterns, e.g. the person taking diuretic drugs, which increase urine production,may waken several times during the night to pass urine (see Ch. 20).

Factors disrupting normal sleep patterns

Many factors can disrupt normal sleep patterns, both in terms of quality and quantity of sleep. Disruption to normal sleep patterns is usually caused by a combination of several factors. These include lifestyle factors, environment, psychosocial factors, physiological factors, physical and mental health problems and the effects of medication.

Nurses in all care settings can help to eliminate factors which disrupt or prevent sleep and promote those which enhance relaxation, rest and sleep. However, there will be occasions when it might be necessary to disturb a person’s sleep in order to perform observations or give care or medication. This is best avoided if possible, and simple measures such as revising medication timing or doing observations without waking the person should be considered (Box 10.10).

Waking a patient/client

Dan, who has severely depressed moods, is an inpatient in an acute mental health unit. He finds it difficult to get to sleep and wakes very early in the morning. Dan went to bed quite early at 22.00 hours and had just fallen asleep when the nurses realize that he has not had his medication.

Lifestyle factors

Lifestyle factors and changes in daily routines can disrupt normal sleep patterns. These may include:

Travelling through time zones causes the biological body clock and circadian rhythms to be desynchronized with the new environmental timing. The effects, which are more marked if travelling east, include:

[Resources: (No author listed) 2004 Clinical facts. What you need to know about … jet lag. Nursing Times 100(36):30; Revell VL, Eastman CI 2005 How to trick Mother Nature into letting you fly around or stay up all night. Journal of Biological Rhythms 20(4):352–365

Shift working

People whose work routines involve rotational night shifts may experience difficulty adjusting to changes in sleep patterns. The work schedule forces the person to sleep against the biological ‘body clock’ when it perceives it is time to be awake and active. Sometimes it takes several weeks before a person’s biological body clock can adjust to the new bedtime hours.

Nurses who are subjected to changing shift work patterns may report feeling rundown, physically exhausted, irritable and have difficulty staying alert when at work. The health of nurses working shifts including nights has consequences for patient safety. Suzuki et al (2004) found there to be significant associations between medical errors, e.g. incorrect patient identification, drug errors, etc., and being mentally in poor health, with night or irregular shift work, and age. A review by Monk (2005) concludes, ‘older people have more trouble coping with shift work’. This has important implications for the UK nursing profession, where 28% of registered nurses are over 50 years of age (NMC 2005).

Research studies with night shift and overtime workers indicate that interruptions of sleep patterns can aggravate existing medical conditions and increase the risks of cardiovascular, gastrointestinal and reproductive dysfunctions (Scott 2000).

Environment

External factors including temperature, ventilation, lighting and the level of noise adversely affect the ability to fall asleep and remain so. These factors can be a problem in all care settings including the person’s own home. Nurses should be aware that people in health/social care settings might take some time to adjust to sleeping in a strange environment. People discharged home or being nursed at home can also find their sleep disrupted, e.g. by having to have their bed downstairs. Examples of the many external factors that disrupt sleep patterns include:

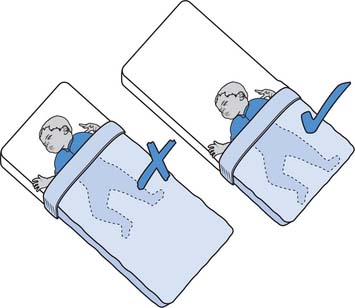

Minimizing the risk of sudden infant death syndrome

Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) (also known as ‘cot death’) is the unexpected sudden death of an infant. Overheating, a prone sleeping position, being in an environment where people smoke and respiratory illness and infection have all been highlighted as risk factors.

Advice for parents/carers includes:

[Resource: The Foundation for the Study of Infant Deaths. Online: www.sids.org.uk/fsid Available July 2006]

As discussed earlier, nurses should be aware that patients/clients might become exhausted when they are continually disturbed for observations and nursing care. Some health/care units advocate a rest period after lunch when the ward/floor/unit is closed to visitors and only essential observations or procedures are undertaken during this period (see Box 10.1, p. 252). This ensures that patients/clients are undisturbed and allowed to relax, rest or sleep for a period during the day. In areas such as high dependency or intensive care units an effort should be made to differentiate day from night by, where possible, decreasing noise and the light intensity and keeping interventions to a minimum for a period during the night.

Psychosocial factors

Most people have experienced a sleepless night prior to an interview or an exciting event. It is easy to appreciate that a person who is constantly worrying about finances, work-related issues or having surgery may find difficulty in falling asleep. Emotional problems and anxiety caused by stress and life events throughout the lifespan, e.g. starting school, a new sibling, moving house, children leaving home, retirement or bereavement, can disrupt sleep (see Chs 8, 11). Children may worry about being accepted at school or be affected by relationships with siblings and parents. Adolescents and young adults often have anxieties about relationships, their appearance, exams and employment prospects.

Mental health problems

People with some mental health problems such as anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder (depressed mood or mania), dementia (see p. 257), eating disorders and disordered thought processes may have disrupted sleep patterns. Sleep disruptions can include hyperactivity, difficulties getting to sleep, early waking and excessive sleeping (hypersomnia).

Physical and physiological changes

Changes in physiological parameters, e.g. changes in body temperature and biological rhythms such as hormonal cycles, can disrupt sleep. Some women experience disrupted sleep patterns in the days before menstruation. The hormonal and physical changes of pregnancy may disrupt sleep patterns, e.g. having to pass urine frequently during the early weeks and again towards the end, or difficulties in getting comfortable in bed. Sleep disruption can also be associated with the hot flushes and night sweats experienced by some women as hormone secretion declines during midlife.

Physical health problems

Physical health problems can disrupt normal sleep patterns. Any condition that causes pain or physical discomfort can result in problems with falling asleep or staying asleep. For example, the pain of arthritis, nighttime cramps or restless legs syndrome (RLS) and itching/irritation of skin rashes are among the diverse factors that disrupt sleep.

Most nurses can relate to having a cold and the discomfort of nasal congestion, which prevents or disturbs sleep. People with cardiac or respiratory disorders may be short of breath and may need to sleep sitting up in bed or a chair (see Ch. 17). Those who have episodes of chest pain and irregular heart beats are often afraid to go to sleep because of the fear of a heart attack at night. People with high blood pressure often feel tired and may wake up very early in the morning.

Problems such as indigestion or pain from a peptic ulcer may prevent sleep or wake the person in the night. Changes in weight can contribute to a poor night’s sleep. For example, severe weight loss and decreased body mass index (BMI) (see Ch. 19) associated with an eating disorder can disrupt sleep. Although people with a higher BMI tend to sleep better, those who are overweight or obese are at risk of sleep apnoea (see Box 10.15) due to the fat stored around the neck making breathing more difficult.

Insomnia

This may take several forms – difficulty in falling asleep, difficulty remaining asleep or an inability to go back to sleep after awakening. It may be temporary, lasting a few nights, or may become chronic. Typically the complaint is of insufficient quantity and quality of sleep, but frequently the person obtains more sleep than they realize. Insomnia can affect any age group and causes tiredness/sleepiness, depression, anxiety, lethargy and irritability during the day. A vicious circle develops where worrying about not sleeping prevents the person from getting to sleep.

Management includes interventions to promote sleep, such as good sleep hygiene (rituals to enhance settling and sleep), pre-sleep routines, reducing anxiety, relaxation and improving the sleep environment (see pp. 264–266). If sleep does not occur it is better to get up, read or have a drink and then go back to bed. Sleeping tablets should only be prescribed in the short term such as during hospitalization for surgery. Specialist help may be needed if the problem is not resolved and becomes chronic.

Narcolepsy (excessive somnolence)

This results when sleep–wake regulation mechanisms are not functioning properly. It commonly occurs during the teenage or young adult years. There is excessive daytime sleepiness culminating in a ‘sleep attack’. During the ‘sleep attack’, the person exhibits sudden muscle weakness (sleep paralysis), being unable to move and falling to the ground. REM sleep can occur within minutes. The ‘sleep attacks’, which happen several times a day, can happen at inappropriate times, e.g. during meals. The person may experience hallucinations and insomnia.

Narcolepsy requires investigation and treatment by a specialist sleep clinic. The person is advised to inform others of the condition. Good sleep hygiene, such as pre-sleep routines and enhancing the sleep environment, is crucial for these patients. Maximum support is needed at home, in the workplace or at school/college.

Sleep apnoea

This is characterized by pauses in breathing – apnoea due to periodic upper airway closure during sleep. This results in a cycle of apnoea–awakening–apnoea throughout the night, disturbing sleep and making it difficult to reach NREM stages 3 and 4. There is also daytime sleeping and risk of accidents. The sudden awakenings are associated with an increase in blood pressure that may eventually lead to an increased risk of strokes and coronary heart disease (see Ch. 17). The condition is more common in men and in people who are overweight or obese (see Ch. 19). Their partners may report very loud snoring and disturbances to their own sleep as a result.

Sleep apnoea requires investigation and treatment by a specialist sleep clinic. Patients should lose weight and avoid alcohol in the evening. If severe, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) may be considered (see Ch. 17). Upper airway surgery may be performed.

Sleepwalking (somnambulance)

This occurs during stage 4 NREM sleep and mostly affects children. About 15% of children aged 5–12 years do quiet sleepwalking. After a brief sleep period, they sit up, eyes open, walk purposefully with an unsteady gait and do strange things, e.g. urinating in the wardrobe. Afterwards they may proceed directly to bed again. Adults can also be affected, particularly if anxious or stressed, and may resume sleepwalking as they once did as children. Sleepwalking may be accompanied by violent behaviour.

Management focuses on preventing injury while the person is sleepwalking. It is best to simply watch sleepwalkers to ensure their safety (and that of others), and perhaps guide them gently back to bed, rather than trying to wake them up.

Sleep/night terrors

These commonly occur in stage 4 NREM sleep. The child sits up and screams. They are clearly terrified but are unable to vocalize the source of the fear. They may have some recollection but it is usually very brief and quickly forgotten. However, the arousal is sudden and causes the body to respond physiologically with sweating, an increased heart and respiratory rate and the strong feeling of fear (this also occurs in nightmares). The child may appear to be hallucinating and pushing an imaginary object or person away. Sleep terrors may be accompanied by violent behaviour. Parental attempts to console are not recognized and rejected. Eventually the child falls asleep.

When caring for a patient/client suffering a night terror, it is important to remain calm and reassuring with a quiet, steady voice. It is best to be sure that the person is alert and knows who you are prior to touching or comforting.

Nightmares

These occur predominately during REM sleep. These are dreams that induce a powerful emotional arousal, often causing sudden awakening.

Nurses can provide reassurance by reminding patients/clients where they are and telling them that they are safe, as they may be disorientated when they wake up. Sometimes a drink or a chance to talk helps to calm their fears. An increase in the amount of lighting in the room may help.

Bruxism (teeth grinding)

This usually occurs in stages 1 and 2 of NREM sleep. It may occur in children when the first dentition has erupted. In older children it may be related to anxiety and stress. Bruxism can cause tooth damage and misalignment. Relaxation therapies and talking through anxieties may be helpful (see p. 265 and Ch. 11). Dental and/or orthodontic interventions such as a nighttime mouthguard may be needed to prevent damage to the teeth.

Other sleep disorders

These include jet lag (see p. 258), shift work sleep disturbance (see p. 258), sleep paralysis, nocturnal enuresis (see Ch. 20), those associated with mental health problems (see pp. 257, 259) and neurological conditions such as epilepsy.

Note: Children with Down’s syndrome and other learning disabilities may show several sleep disorders, some of which may be due to physical problems, e.g. disordered breathing and sleep apnoea. Sleep deprivation and related daytime behaviour problems are also apparent (Stores et al 1996).

People who have problems with the urinary system often have to get up during the night to pass urine (nocturia) (see Ch. 20). Nocturia disrupts the sleep cycle and getting back to sleep may be difficult. In older people, nocturia may be caused by heart or kidney disorders, or enlargement of the prostate gland in older men. It is worth noting that this further disrupts sleep in a group who are already sleeping less well at night.

Many problems such as back injuries or joint deformities may force people to sleep in positions to which they are unaccustomed. Assuming an awkward position while attached to monitoring equipment in hospital, or an i.v. infusion, or having a leg in plaster or in traction can interfere with sleep.

People who cannot change their own position in bed, such as those with severe physical disabilities or following a stroke, can suffer discomfort and disrupted sleep. Box 10.13 provides an opportunity for you to consider how a restricted sleep position could affect sleep.

Effects of medication

People who take medication, either prescribed or over-the-counter (OTC), herbal products or illicit drugs may experience sleep disruption. This may be due to side-effects or interactions of the medications with other medication or alcohol, food or beverages. If the medications are required for treatment of chronic illness, e.g. diuretics, it may be necessary to review the dosages and time of administration in order to prevent disruption of sleep. Drug groups that may disrupt sleep include:

The effects of caffeine, nicotine and alcohol on sleep patterns are outlined above (see p. 258).

Nurses should ensure that people are forewarned about any prescribed or OTC medicines that can affect sleep and advise them to read enclosed information and any warning labels (Box 10.14). Patients should be asked to seek advice if sleep disruption occurs.

Medicines that disrupt sleep patterns

Think about common medications used for the patient/client group in your placement.

Student activities

[Resources: British National Formulary (BNF) – www.bnf.org.uk; BNF for Children – www.bnfc.org Both available September 2006]

Sleep disorders – an outline

Sleep disorders cover a wide range of conditions affecting both adults and children. These include insomnia, snoring, sleep apnoea, narcolepsy, sleepwalking, etc. The commoner sleep disorders are outlined in Box 10.15 but readers requiring more information are directed to Further reading (e.g. World Health Organization 1992, Chokroverty 2000). Fuller coverage of the general interventions to promote sleep is provided below (pp. 262–266).

Sleep disorders will have individual physical effects but they also have a huge psychosocial impact on every area of life. This might include problems with education and study, work and relationships. For example, parents/carers or partners may be prevented from sleeping by snoring, or by anxiety about a loved one who has sleep apnoea or who sleepwalks.

It is important for the nurse to be aware of any limitation of skill in this specialist area. The person/carer/parent who complains of a sleep disorder should be advised to seek specialist help at a sleep clinic and offered information about support groups, e.g. The British Snoring and Sleep Apnoea Association (see ‘Useful websites’, p. 274). Parents/carers should be encouraged to discuss any sleep problems with their health visitor, children’s community nurse or learning disability liaison nurse (Box 10.16).

Sleep problems and learning disability

7-year-old Molly has a learning disability. She lives at home, attends school and regularly goes into respite care to give her parents a break. Molly has always been difficult to settle at night but now she becomes distressed at bedtime, pulling her hair and screaming. She only sleeps for 2–3 hour periods and wakes her parents every night. Molly’s parents are exhausted and feel that they need help to deal with Molly’s sleep problem.

Student activities

[Resources: Gates B (ed) 2002 Learning disabilities. Towards inclusion. 4th edn. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh, Chs 10, 20; Sleep Scotland – www.sleepscotland.org Available July 2006]

Nursing interventions to promote sleep, rest and relaxation

The nurse plays a key role in helping patients/clients to obtain sufficient sleep and rest. A holistic nursing assessment that includes normal rest and sleep patterns and pre-sleep routines is central to planning interventions that promote rest and sleep. Patients/clients or parents and carers may also be asked to keep sleep diaries where sleep patterns are disrupted. In addition, this part of the chapter will consider sleep hygiene/pre-sleep routines/rituals and the sleep environment and the role of relaxation, orthodox medications and herbal medicines in promoting sleep. In all of these measures, it is vital to involve the patient/client/child, parent or carer in the assessment and decision-making about appropriate interventions and in evaluating their effectiveness.

Nursing assessment of sleep

It is important for the nurse to have an understanding of the patient’s/client’s normal sleep pattern and habits in order to plan appropriate interventions and detect departures from normal. Most people suffer disruptions to sleep patterns at some time and the nurse should note whether there is difficulty in falling asleep, frequent waking during the sleep cycle, early wakening or oversleeping and the degree to which the quantity, quality and consistency of sleep are affected.

A holistic assessment should include information that includes:

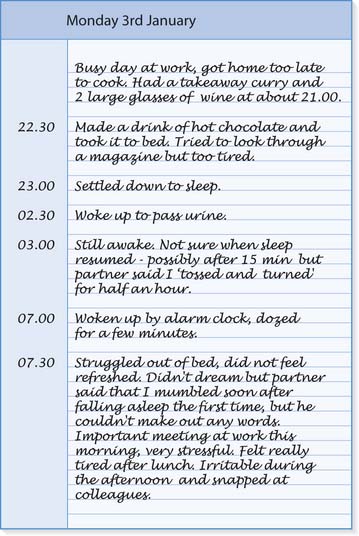

Keeping a sleep diary

When sleep patterns are disrupted or a sleep disorder is suspected, patients/clients, parents or carers are encouraged to keep a diary. Initially, this can be for 1 week. The contents can help to identify the main problems and highlight factors that relieve or exacerbate sleeplessness. The diary can be used as a tool to assess progress and efficacy of interventions used to improve the person’s sleep pattern. Initially this can prove tedious to document but once a routine is developed, it becomes easier. In the author’s experience, most people who have a severe sleep problem would do anything to resolve it. It is very important to accept the person’s interpretation of their sleep pattern/sleep disruption, even if it does not agree with your own analysis.

It is important to explain from the outset what the aims of the diary are and to support and give positive feedbackto the person for persisting with the documentation. It is helpful to provide written instructions (prompters of key phrases and questions) for completing the diary (Box 10.17). Involving children in describing their sleep patterns will be enhanced by providing age-appropriate documentation, such as colouring books, cartoons depicting children sleeping/not sleeping, clock faces with movable hands or the use of stickers for hours slept.

Box 10.17 Keeping a sleep diary

Note: Include other relevant information, e.g. upset after a row with partner, period started, really worried about the electricity bill, etc.

After some time people become familiar with the requirements and ‘automatic’ documentation occurs without the instruction sheet. Some people may prefer to use special charts with dates, times and prompters instead of a standard diary. The completion of the diary should coincide with follow-up sessions at the clinic to discuss the results with the nurse, doctor or therapist. Figure 10.5 illustrates a typical sleep diary entry.

Improving sleep hygiene and the sleep environment

Simple changes can improve sleep hygiene such as trying to go to bed and get up at about the same time each day. It is also helpful to avoid using the bedroom/bed for other activities such as working or eating. Developing a pre-sleep routine that helps the person to fall asleep and stay asleep is important. This might involve a bedtime story, a milky drink, warm bath, changing into nightclothes, teeth/denture cleaning and passing urine. In hospital or care home, the nurse should try to maintain the person’s pre-sleep routine as far as is possible, and offer assistance as required.

People should be given advice about eliminating factors known to disrupt normal sleep patterns (see pp. 257–260). This might include reducing strenuous physical activityin the evening and encouraging quiet play for children. Some people may need to reduce caffeine intake, e.g. by replacing tea or coffee with fruit or herbal teas. Avoiding an excessive fluid intake just before bedtime can minimize nocturia in children and older people. However, they must have sufficient fluids during the day (see Ch. 19). Others may need to eat their main meal earlier in the evening and have a small bedtime snack. A bedtime snack should be available in hospital or care home if necessary. Excessive daytime sleeping or naps may disrupt sleep at night and people may need advice about reducing naps.

Some patients/clients may wish to carry out religious activities such as prayers before sleep, or need their bed in a position that allows them to face the correct way, i.e. towards Mecca. Some people will want to see a local religious leader or read from a particular holy book. These facilities and privacy should be made available.

It is important to promote sleep by ensuring comfort and providing an environment conducive to sleep before medication is considered. The many simple interventions that promote sleep, either at home or in a care setting, include the following:

Aiming for silence

Sleep can be difficult to achieve if noise levels are too high or if the type of noise changes. Noise will affect sleep in every setting including the person’s home.

Relaxation and sleep

Anyone who is suffering from altered sleep or significant sleep disorders often complains of feeling stressed, anxious and tense and not being able to relax (Box 10.19). Several research studies have highlighted the efficacy of complementary therapies in improving sleep patterns. Most of these therapies are effective in inducing relaxation and so offer an important clinical contribution to stress-related sleep disorders. For further coverage of relaxation techniques and their uses in a variety of situations such as stress and pain, see Chapters 11 and 23.

Relaxation and sleep

Think about a patient/client who has difficulties with relaxing and getting to sleep.

In a study by Lichstein et al (1999) participants who received relaxation therapy reported additional benefits that included improved sleep efficiency and reduced withdrawal symptoms during a sleep medication withdrawal programme. Massage and relaxation therapy comprising muscle relaxation, mental imagery and music improved sleep in older patients with cardiovascular illness nursed in a critical care unit (Richards 1998). In a study by Chen et al (1999) acupressure and massage therapy improved the quality of sleep in older people. Herbal medicines are considered below and the wider uses of herbal medicine on pages 269–270.

Orthodox medications

Medication may be used to aid rest and sleep for patients/clients who cannot sleep despite the non-pharmacological interventions discussed above. The cause of insomnia should be known; for example, ‘sleeping tablets’ may be prescribed for a patient who is in hospital following surgery and cannot sleep because of noise. The drugs used to aid sleep include hypnotics (drugs that induce sleep), anxiolytics (drugs such as tranquillizers that reduce anxiety) and analgesic drugs (painkillers) (see Ch. 23). In addition, the dose of antidepressant drugs, such as amitriptyline and mirtazapine, can be adjusted and taken at night to improve sleeping in people suffering from depression. However, hypnotic and anxiolytic use has a number of disadvantages, including:

Examples of the medications used to aid sleep are provided in Box 10.20 (see p. 266) but readers requiring more specific information about indications, side-effects, contraindications, etc. should consult the British National Formulary.

Box 10.20 Examples of orthodox medication used to aid sleep

Note: Barbiturates are very rarely used for insomnia and only for people already prescribed them for severe insomnia which is resistant to treatment. They should not be prescribed for older people. Hypnotics are not generally used for children, but may be prescribed for sleepwalking and night terrors.

[Resource: British National Formulary – www.bnf.org.uk Available September 2006]

Herbal medicines

Valerian (Valeriana officinalis), hops (Humulus lupulus), lemon balm (Melissa officinalis), passion flower (Passiflora incarnata), chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla) and lavender (Lavandula angustifolia) have all been traditionally used in herbal medicine for treating restlessness and sleep disturbances.

It is very important to advise people to avoid self-medication with OTC products, especially herbal products, which are advertised to promote sleep. These products may interact with the person’s prescribed conventional medications. It is always safer to consult a trained herbal practitioner who can advise the patient and ensure that the most appropriate herbal remedy is available to help promote sleep in that individual. The principles of herbal medicine are covered more fully on page 269–270.

Complementary and alternative medicine

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) refers to the health-related therapies, which are not considered to be part of conventional (mainstream) or allopathic medicine. These therapies tend to be health interventions practised by different cultures over thousands of years. Some CAM therapies offered in conjunction with conventional medicine are described as complementary, e.g. aromatherapy (see pp. 271–272), whereas others, such as osteopathy, provide diagnostic information and are offered as an alternative to conventional medicine. CAM therapies are very diverse. The British Medical Association (1993) concluded that there was no common principle linking the therapies and that there was diversity in approach and delivery.

It is clear that most CAM therapies differ from conventional medicine management in their approach and underlying beliefs, principles and philosophies. It should be noted that there is no one single philosophy shared by all CAM disciplines. Some CAM philosophies are linked to religious practices of the country of origin. They have evolved over centuries of use and are incorporated into interpretations of body functions, health and disease. The majority, if not all, of CAM therapists believe that their view of care embraces all dimensions of the person sothere is less divide between the body, mind and spirit, hence the term ‘holistic’ is often used.

The emergence, development and regulation of CAM

In the late 1980s and early 1990s there was an increase in interest and wider use of CAM in the UK by both the general public and health professionals, especially nurses. Several studies suggest that there were approximately 50000CAM practitioners and, of these, 10000 self-registered practitioners offered CAM alongside conventional care. Five million people consulted a CAM practitioner in 1995. People accessed CAM through CAM practitioners, through other health professionals, including doctors, nurses and physiotherapists who offered CAM, or by purchasing OTC products. These data, though limited, suggest that the public are very interested in CAM. This popularity is not confined to the UK; surveys conducted in Australia, the United States and Europe suggest that the public there are equally keen to use CAM. In Europe, however, a slightly different approach exists in that CAM is practised alongside conventional medicine (DH 1996, Budd & Mills 2000). Several surveys reporting on patient/client satisfaction and the popularity of CAM have identified certain themes and characteristics of CAM therapies (Box 10.21).

[From House of Lords (2000)]

This widespread use of CAM raised concerns about having in place rigorous structured regulations to protect public safety and interests. There was a need to consider several related issues such as an evidence base for research, adequate training for practitioners, information resources for the public and what prospects there were for NHS provision of these therapies. These concerns prompted a House of Lords Select Committee report (House of Lords 2000) and the government’s response the year after (DH 2001). The report noted that there was a wide range of therapies under CAM (Box 10.22). Some therapies had complete systems of assessment and treatment whereas others complement conventional treatment with various supportive techniques. While some were well regulated, others were very fragmented with no consensus about regulation.

Box 10.22 Categories of CAM therapies

[Adapted from House of Lords (2000)]

Group 1 therapies

These include acupuncture, chiropractic, herbal medicine, homeopathy and osteopathy.

Viewed as the ‘big five’ in CAM, these offer diagnostic skills, appear to be the most organized and already have an established research base for some aspects of practice. There is increasing NHS provision for the therapies in this group.

Group 2 therapies

Aromatherapy, the Alexander technique, massage, counselling, stress therapy, hypnotherapy, reflexology, shiatsu, meditation and healing form this group. They are often used to complement conventional medicine and do not include diagnostic techniques. There is some NHS provision for these therapies, especially in palliative care settings and with people with a learning disability.

Chiropractic and osteopathy are already self-registered and self-regulated which means that their professional activity and education are regulated by Acts of Parliament. Practitioners must be registered with the General Chiropractic Council or General Osteopathic Council, respectively, in order to practise in the UK.

Integrated medicine

Despite the wide diversity of CAM and its popularity, access to CAM via the NHS remains limited. It would seem that CAM could have a potential role in the management of care in the NHS alongside conventional therapies. A steering committee was set up by the Prince of Wales to consider how CAM and orthodox healthcare in the UK could work more closely together.

The Foundation for Integrated Medicine (now known as the Prince of Wales’s Foundation for Integrated Medicine) aims to promote the development and integrated delivery of safe, effective and efficient forms of healthcare. The Foundation encourages greater collaboration between practitioners of all forms of healthcare. Operating as a forum, it actively promotes and supports discussion and acts as a centre to facilitate development and action. Its objective is to enable individuals to promote, restore and maintain health and well-being through integrating the approaches of orthodox, complementary and alternative therapies (Foundation for Integrated Medicine 1998). Hence many practitioners now consider the term CAM to be slightly outmoded and that it is more appropriate to use ‘integrated medicine’ or indeed ‘interprofessional health care’ instead.

CAM therapies

This part of the chapter outlines the scope and main characteristics of the ‘big five’ CAM therapies – acupuncture, chiropractic, herbal medicine, homeopathy and osteopathy – and some of the others, e.g. aromatherapy, that have been integrated into conventional healthcare.

It does not lay claims for efficacy. Where treatment and conditions are linked, it serves only to highlight that a particular treatment exists rather than the author’s or editor’s opinion or recommendation.

The language used to describe elements of a particular therapy such as ‘vital force’, ‘holism’ and ‘energies’ are existing terms related to that therapy.

Readers requiring information about other therapies such as humour therapy, shiatsu, massage, therapeutic touch, etc. are directed to Further reading (e.g. Rankin-Box 2001).

Acupuncture

Acupuncture has been widely practised in China since the first century bc. It involves the insertion of small needles into specific points on the surface of the body. In the 1970s, it gained wide publicity in the West where it is used mainly for pain relief. Currently in the UK, registered medical practitioners and other healthcare professionals practise acupuncture. At the time of writing acupuncture is not subject to statutory regulation. However, the results of a consultation on the statutory regulation of herbal medicine and acupuncture were published in 2005 (DH 2005) and publication of draft legislation, followed by legislation, is planned.

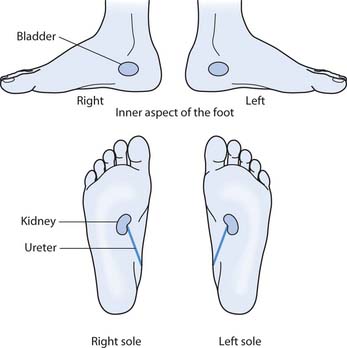

Acupuncture is a heritage of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), which also includes the use of herbs, diet, massage, acupressure and relaxation through special exercises. The fundamental principles of TCM are based on the belief that a person functions in harmony with the universe. So health, disease and treatment relates to a person’s harmony or disharmony with external forces of wind, damp, dryness and cold, and internal anger, excitement, worry, sadness and fear. Elements such as wood, fire, earth, metal and water are used to describe various states of health and illness. Illness is also defined by two complementary, but opposite, forces – yin and yang – and their perfect balance within the body, which is essential for good health. Yin represents cold, damp, darkness, passivity and contraction whereas yang signifies heat, dryness, light, action and expansion. The interaction of yin and yang gives rise to ‘qi’ (pronounced ‘chee’). Qi is an invisible life energy and is a vital force that flows around the body through meridians or energy channels. There are 12 regular meridians, which run down the body in pairs, six on the left and six on the right.

The meridians are mostly named for the main internal organs through which they pass, e.g. the lungs or kidneys. The even circulation of qi around the body is essential for health. Disruption of flow on a meridian can create illness at any point along it, e.g. a disorder in the stomach meridian (passing through the upper gums) could cause toothache. There are about 365 points along the meridians at which qi is concentrated and can enter and leave the body. It is possible to affect the circulation of qi at these points and acupuncturists insert the acupuncture needles to stimulate or suppress its flow. This is thought to influence the health problem by restoring energetic balance and organ function.

During the first consultation, a standard and thorough interview to establish the presenting problem, past medical history and a physical examination is required. Specific questions and examination related to acupuncture would include:

The treatment involves the insertion of tiny needles in the area of the body where the blocked energy to the circulation network is identified (Fig. 10.6). The needle is usually left in place for 5–20 minutes. However, it is important to protect the person/client from energy depletion so a much shorter time is used for a person who is very tired or frail and old.

If additional activation of the acupuncture system is required, the stimulation is achieved by connecting the needles to an electrical device, by moxibustion (heating the needles with burning mugwort – an aromatic herb) or by gentle manual manipulation of the needles.

Weekly treatments are scheduled until a good response to treatment is obtained, after which follow-up treatments can be every 4–6 weeks or further apart.

Integration of acupuncture into conventional healthcare

The type of acupuncture which is more commonly integrated into orthodox healthcare is ‘Western medical acupuncture’. This is acupuncture that has been adapted and is practised by orthodox medical and other health professionals in the West. In some areas of the UK it is available on the NHS. It uses the same needling technique as traditional acupuncture described above but worksby affecting nerve impulse transmission and the central nervous system. Acupuncture is effective for anaesthetic and analgesic (see Ch. 23) purposes, especially for musculoskeletal complaints (Box 10.23). Other uses include substance misuse (e.g. smoking cessation), in maternity care, migraine, high blood pressure and digestive disorders. Although traditional acupuncture described above is now a widely accepted Eastern therapy, medical opinion is still divided on its efficacy.

Acupuncture in orthodox healthcare

Orthodox practitioners, e.g. physiotherapists and anaesthetists, use acupuncture to relieve pain and induce sleep. Research by Andrzejowski and Woodward (1996) concluded that sleep patterns in healthy adults improved.

Student activities

[See Further reading, e.g. Rankin-Box (2001)]

Chiropractic

The term chiropractic comes from the Greek words cheiro, meaning ‘hands’ and prakticos, meaning ‘doing’. Together this means ‘done by hand’ or manipulation. Developed in the late 19th century by David Palmer, a Canadian osteopath, chiropractic diagnoses and treats disorders of the spine, joints and muscles. Chiropractics use their hands to manipulate joints and adjust muscles by high velocity, short amplitude thrust and gentle soft tissue massage.

With these techniques the health of the central nervous system and body organs is maintained through realignment of the nerve supply to the affected area. Chiropractic is used to treat musculoskeletal complaints by relieving pain, increasing mobility and improving function.

A chiropractic views the body as a mechanical structure with the key being the spine, which links the brain to the rest of the body. Therefore, any distortion of the spine affects the working of other parts of the body and the reduced ‘nerve flow’ leads to disease. Chiropractics believe that treatment can ease muscle tension caused by stress or those linked to problems in some internal organs such as the intestine. When the skeletal structure functions smoothly, the body’s natural healing processes are free to keep all body systems working in harmony. When body systems are in harmony it is believed that the body has the ability to heal itself from within.

During the initial consultation a detailed case history of the presenting problem, past medical and surgical history as well as lifestyle factors are explored. For example, the person/client is asked about exercise and type of bed used. A full clinical examination of the condition and function of the spinal column will be carried out by asking the person/client to adopt different postures, e.g. lying down, sitting and standing.

Diagnostic procedures include X-rays, neurological tests including reflexes, ‘motion palpation’ to check the spine and use of a rubber-tipped instrument called an activator. The ‘activator’ delivers a very small thrust and is used to manipulate the vertebrae. The activator can be used for very frail older people and even babies.

Treatment, usually during the second session, entails using controlled techniques with the hands to adjust and ‘unlock’ any joint problems. The person/client may hear the joints ‘click’ during the manoeuvres but these are painless. The first session takes about an hour and subsequent sessions about 20 minutes. The person/client may experience some muscle aches and pains for a few days after the treatment and should be told that this can occur and be reassured that it is normal. Initially the person/client is required to attend two to three times per week with follow-up visits of weekly sessions until the problem is resolved. Chiropractics recommend ‘maintenance’ visits 6–12 monthly to keep recurring problems at bay. Surgery is never used by the chiropractic and if the problem requires specialist treatment the person/client will be referred to their GP.

Integration of chiropractic into conventional healthcare

A study by Meade et al (1990) reported that chiropractic treatment for low back pain (severe or chronic) was more effective than standard outpatient care. They concluded that consideration be given to introducing chiropractic into the NHS. A follow-up study (Meade et al 1995) confirmed the earlier findings.

Chiropractic can also be used to treat neck and spine problems, muscle, joint and postural problems, sciatica, migraine, sports injuries and gastrointestinal disorders. In the UK, chiropractics are subject to statutory regulation and must register with the General Chiropractic Council in order to practise. Some orthodox practitioners are also trained chiropractics.

Herbal medicine

Over 80% of the world’s population use herbs for health maintenance. Herbal medicine, one of the most ancient forms of treatment, is used by every culture to treat disease and promote well-being. It is a system of medicine that uses plants and plant extracts as remedies to treat disorders, promote and maintain good health. There are several subcategories practised in the UK, namely Chinese herbal medicine, Tibetan herbal medicine, Ayurvedic herbal medicine and Western herbal medicine (also called phytotherapy or phytomedicine). Chinese herbal medicine is an integral part of and practised with TCM and acupuncture. This chapter focuses on Western herbal medicine. At the time of writing herbal medicine is not subject to statutory regulation. However, the results of a consultation on the statutory regulation of herbal medicine and acupuncture were published in 2005 (DH 2005) and publication of draft legislation, followed by legislation, is planned.

Conventional medicine uses laboratory-produced drugs which, although derived from plants, are often refined until a single active ingredient has been isolated. Herbal remedies differ from these synthetic drugs in that parts of a whole plant are used as the remedy. Western herbal medicine is a holistic treatment system that seeks to restore the body’s self-healing mechanism or ‘vital force’. Remedies are prescribed, tailored to the holistic needs of the person, not just the symptoms of the illness. Rather than treating symptoms in isolation, the herbal practitioner looks for the cause of illness such as poor diet, an unhealthy lifestyle or excessive stress, which may have overburdened and imbalanced the body’s delicate homeostatic physiological, psychosocial and spiritual domains. Practitioners attribute disease to a disruption in the maintenance of the body’s state of harmony or homeostasis. Herbal remedies promote healing by supporting the body’s vital force in its efforts to restore homeostasis.

The herbal practitioner’s skills lie in knowing the actions of different plant constituents on specific body systems. For example, a plant, or indeed a part of it, may stimulate the circulation or calm the digestive system.

Herbal synergy is a key factor in medical herbalism. According to this theory, parts of whole plants are more effective than the isolated constituents used in synthetic drugs. Herbal practitioners believe that the synergy gives a greater and better therapeutic effect. For example, meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria), which can be used to treat digestive disorders, contains salicylic acid, the basis of the widely used drug aspirin. However, while aspirin can cause gastrointestinal bleeding, meadowsweet contains tannins and mucilage that protect the stomach lining (Mills et al 2000).

Herbal remedies are extracted from leaves, flowers, fruits, stems, bark, roots, rhizomes, seeds or exudates (e.g. frankincense resin) and other parts of a whole plant which contain a complex mix of active ingredients that produce the plant’s medicinal effects. This use of strictly plant products is unlike other herbal traditions (e.g. Chinese herbal medicine) where non-plants (e.g. insects, shells, minerals, animal bone or organs) are also used.

Herbal remedies can be made from combinations of herbs or from a single herb.

Remedies can be given to people/clients in several different ways. These include:

Every herbal remedy is said to have three effects on the body: to detoxify and eliminate wastes, to strengthen it and help it heal itself and to build up the organs.

The first consultation takes about 1½ hours. A detailed case history of the presenting complaint, past medical history, social history, medications and lifestyle factors are discussed. Diet history is an important aspect of the assessment. If deemed necessary, physical examinations related to the presenting complaint – for example, using a stethoscope to auscultate the lung fields or the heart, or a neurological examination – will be carried out. The management plan is then discussed with the person/client. The relevant remedy could be a tincture or a combination of herbs, teas or creams. The first review is normally at 2 weeks and if the condition is responding well to treatment, follow-up will be at intervals of 4–6 weeks. People’s/clients’ involvement in their own healing is important and they are advised to actively engage in making lifestyle changes encompassing social context and self-responsibility. Complex cases should be referred to the GP or another appropriate health practitioner and the person/client advised that herbal treatment is not suitable in some cases.

Integration into conventional healthcare

In the UK, some hospitals and GP practices have part-time Western herbal practitioners working within the multidisciplinary setting. However, people/clients who are using herbal treatment are usually self-funding. In Europe, e.g. Germany and France, Western herbal medicine is practised by conventionally trained physicians and integrated into routine medical care. These consultations and treatment, therefore, generally follow the principles of a conventional medical appointment. Herbal medicines can be used to treat a range of diverse conditions including musculoskeletal disorders, menstrual irregularities, anxiety and nervous tension, as well as gastrointestinal upsets. For example, colic in babies may be reduced by the use of dill (Anethum graveolans) and fennel (Foeniculum vulgare). These may be prescribed as teas for breastfeeding mothers or as tincture drops in juice for older children (Scott & Barlow 2003).

There is a dearth of controlled studies on the efficacy of herbs, especially those used to enhance sleep, andthis is an area where nurses can engage in collaborative research with herbal practitioners (Box 10.24).

Box 10.24  EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

Herbal medicine

‘As a registered nurse, midwife or specialist community public health nurse you have a responsibility to deliver care based on current evidence, best practice and, where applicable, validated research when it is available.’

Nursing and Midwifery Council (2004, clause 6.5, p. 10)

Student activities

[Resources: Coxeter PD, Schluter PJ, Eastwood HL et al 2003 Valerian does not appear to reduce symptoms for patients with chronic insomnia in general practice using a series of randomized n-of-1 trials. Complementary Therapies in Medicine 11(4):215–222; Houghton PJ 1999 The scientific basis for the reputed activity of valerian. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 51(5):505–512; Leathwood PD, Chauffard F, Heck E, Munoz-Box R 1982 Aqueous extract of valerian root (Valeriana officinalis) improves sleep quality in man. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior 17(1):65–71; [Reference: Nursing and Midwifery Council 2004 The NMC code of professional conduct: standards for conduct, performance and ethics. NMC, London]

Homeopathy

Derived from the Greek words homoios, meaning ‘like’ and pathos, meaning ‘suffering’, homeopathy is a system of medicine that uses remedies prepared from plant, mineral and animal substances. These remedies are taken by mouth in tablet, powder or liquid form or applied as creams.

Hippocrates, in the 4th century bc, proposed that a substance which mimics an illness can be used to cure it. This principle of treating ‘like with like’ was later developed into homeopathy in the 18th century by a German doctor, Samuel Hahnemann. According to this principle or Law of Similars, ‘like cures like’, so a substance that produces symptoms similar to the disease can be used to cure the disease. Thus a person’s symptom is used as a guide to finding the remedy. For example, being stung by nettles produces a rash, redness and inflammation. The same herb when prepared as a homeopathic remedy can be used to treat allergic reactions producing the same symptoms. Another example is eyebright (Euphrasia officinalis), an irritant herb, which can be used to soothe inflamed eyes.

The Law of Potentization in homeopathy relates to the idea that the more a remedy is diluted the more potent it is to heal but at the same time the ‘potential’ to cause side-effects is reduced. In a typical dilution, one drop of the ‘mother tincture’ (preparation of the plant material in alcohol) is diluted in 99 drops of alcohol, and then shaken vigorously in a process known as succussion.

Homeopaths view symptoms of illness as a sign that the body is using its natural powers of self-healing to fight back. Accordingly, the body is integrated with a vital force, which maintains it in a state of health. If the body is put under strain, illness can result. Homeopathic treatments stimulate the body’s self-healing ability rather than suppress symptoms of the illness.

The first consultation takes about 1½ hours. The person’s/client’s detailed medical history as well as lifestyle, diet, physical and emotional factors (e.g. mood, likes and dislikes), sleeping patterns, reactions to weather conditions and personality traits are discussed. This exploration of the person’s/client’s problems and needs is essential so that the best matching remedy can be prescribed. The appropriate remedy may be an animal, plant or mineral preparation, e.g. sepia (cuttlefish ink), aconite (monkshood) and nat mur (sodium chloride) (Phatak 1988). Homeopaths put less emphasis on physical examination and believe that for longstanding problems it is necessary to review the treatment over numerous consultations where the prescription can be altered according to the changes in the symptoms presented.

Osteopathy

The term is derived from the Greek osteon ‘bone’ and pathos ‘disease’. Dr Andrew Taylor Still, a doctor in the American Civil War in the 19th century, developed this therapy. Osteopaths see the organs of the body as supported and protected by the musculoskeletal system. The bones, joints, muscles, ligaments and other connective tissue provide a framework or scaffolding for the body. If this scaffolding is correctly aligned and working well, the tissues and systems of the body will be healthy.

The initial consultation takes about 1 hour. After diagnosis, massage and manipulation are used to improve mobility of joints and soft tissues. The osteopath will try to look for the reasons behind the fault in the musculoskeletal system. A holistic approach will help to restore the body’s ability to heal itself. All aspects of lifestyle, physical, mental and emotional health are seen as important factors influencing physiological health. Poor posture or injury can affect the musculoskeletal system causing pain, strain, impaired local or systemic nerve function and affect the vital organs and body systems. Manipulation of misaligned joints and a focus on soft tissues (muscles, tendons, etc.), treatment to relax muscles and bring back joint mobility will be used. Initially weekly sessions may be necessary until the problem is resolved; follow-up can be 4–6 weekly.

Integration into conventional healthcare

Osteopathy was the first complementary therapy to be subject to statutory regulation (Osteopaths Act 1993). The General Osteopathic Council ensures that practitioners are trained and regulated according to statutory requirements in order to protect public safety and interests. In the UK, osteopaths must be registered with the General Osteopathic Council in order to practise.

The therapy is well supported by many GPs who refer people for NHS-funded osteopathy.

Alexander technique

This is a form of education rather than a therapy where the person is trained to avoid ‘bad habits’ which give rise to poor posture and then learn to readjust to body alignment. An Australian actor called Frederick Alexander developed the Alexander technique in the late 19th century. The technique is based on the theory that the way a person uses their body affects their general health.

The Alexander technique encourages people to optimize their health by teaching them to stand, sit and move according to the body’s natural design and function. This is, in essence, a taught technique and can be taught on a one-to-one basis to any age group.

During the first consultation, the person is asked to go through a series of movements so that their posture and body alignment can be assessed. The first treatment session involves lying down, relaxing the body and light adjustments are made if necessary. Subsequent sessions involve the person sitting or standing while the teacher adjusts posture and re-educates the person to use muscles with minimum effort and maximum efficiency. Further sessions entail different movements involved with standing, moving, sitting, lying down, walking and lifting objects. A session lasts 30–45 minutes, usually twice weekly, and a course may be 15–30 sessions depending on the person’s progress.

Aromatherapy

Ancient cultures in China, Egypt and India used plant oils combining their medicinal properties with the ancient art of massage. The modern use of plant oils is attributed to a French chemist, Rene Gattefosse, who coined the term ‘aromatherapy’ in 1937.

Plant material such as flowers, leaves, stems, roots and barks yield oily substances that are refined into ‘essential oils’. Distillation (subjecting the plant material to steam till vaporization) is one method of extracting the oils. There are many essential oils, including those extracted from tea tree (Melaleuca alternifolia), common lavender (Lavendula angustifolia) and frankincense (Boswellia carterii). Other oils – known as ‘carrier’ or ‘base’ oils – used with essential oils for making massage blends are marigold (Calendula officinalis) and grapeseed (Vitis vinifera) (Mills et al 2000). A study of lavender essential oil concluded that it reduced restlessness during sleep in a small sample of older people (Hudson 1996). Lewith et al (2005), in a pilot study to evaluate methodology and the efficacy of the aroma of lavender on insomnia, report that women and younger participants improved more than others. In their conclusion the authors indicate that the outcomes favour lavender, and recommend that a larger trial be conducted to draw definitive conclusions.

A few drops of the essential oils diluted in the carrier oil can be absorbed into the body in several ways. These include:

Oils with specific properties can be selected to invigorate or relax the person and induce sleep by influencing mood, emotions and physical well-being (Price & Price 2006). Aromatherapy may be used for simple relaxation but it can be useful in a wide range of conditions that include insomnia, restlessness, stress, anxiety, muscle pain, migraine and other headaches, etc.

The first session involves a holistic history-taking regarding medical history, lifestyle factors and essential oils likes and dislikes. An essential oil blend is selected and used in a full body massage or selected areas of the body appropriate to the client’s needs. Advice about home treatments using oils for baths or diffusers may be recommended as appropriate. An initial consultation and massage session may take up to 2 hours. Follow-up sessions usually take about 1 hour if it is for a full body massage. A course of treatment may entail weekly sessions for 4 weeks and fortnightly or monthly thereafter. It is common for clients to have a series of treatment sessions.

Integration into conventional healthcare