Chapter 24 Caring for the person having surgery

Introduction

A person who has to undergo a surgical procedure or invasive investigation is likely to experience both psychological and physiological stress (see Ch. 11). Stressors can be reduced by careful planning and considered nursing intervention. Preoperative care is that carried out before an operation and postoperative care begins after surgery. Perioperative care is a nursing speciality that includes the care provided from arrival in the anaesthetic room, during an operation and in the recovery area afterwards, although this term is sometimes extended to include all the care given to a surgical patient during their admission to hospital or a treatment centre (specializing in certain types of surgery such as joint replacement) (see Ch. 3). Examples of invasive procedures, day surgery and inpatient stays are outlined, together with different reasons for and aims of surgery. The importance of the nurse’s role in preoperative and postoperative care is explored within this chapter. Maintaining patients’ safety and dignity is paramount in surgical nursing. Discharge planning usually begins before admission for surgery and is explained in the final section. Surgical nursing care should be seamless, despite it being carried out in several different settings, and the factors that facilitate this are considered.

Types of surgery

This section considers the different approaches to surgical interventions. There have been great advances in the way people can receive surgical treatment, including:

The expected outcome of surgery varies depending on the reason for intervention. This may be:

There is a wide range of terminology used to describe surgical procedures. By understanding the meaning of some commonly used prefixes and suffixes this becomes logical and much easier to understand (see Table 24.1). It is good practice to look up the meanings of new terms encountered in practice. Surgery and invasive procedures take place in a wide range of specialities (see Table 2.4, p. 61).

Table 24.1 Terminology used to describe surgical procedures

| Meaning | Example | |

|---|---|---|

| Prefixes | ||

| Angio∼ | Of a vessel | Angiography |

| Chol∼ | Bile | Cholecystectomy |

| Cysto∼ | Of the bladder | Cystectomy |

| Gastro∼ | Of the stomach | Gastrostomy |

| Laparo∼ | Abdominal | Laparotomy |

| Suffixes | ||

| ∼ectomy | Removal of | Appendicectomy |

| ∼oscopy | View of | Laparoscopy |

| ∼ostomy | Opening of | Ileostomy |

| ∼otomy | Incision into | Osteotomy |

| ∼plasty | Reconstruction of | Angioplasty |

| ∼therm | Heat | Diathermy |

Surgical interventions may be classified as:

Elective surgery

People who undergo elective surgery are usually admitted on the day of surgery having already had pre-assessment and the necessary investigations (see below). Careful preparation ensures patients are in optimal health for their operation. This minimizes cancellation when further investigations are needed or unforeseen problems arise, thereby reducing the likelihood of postoperative complications. The type and extent of surgery, together with the individual’s state of health before, during and after surgery, will determine the length of stay in hospital. When day surgery is undertaken the patient goes home again the same day, whereas inpatient surgery usually requires several days in hospital postoperatively. Some patients need a series of surgical interventions, e.g. reconstructive surgery following severe or disfiguring injuries.

Day surgery

Day surgery, which started with children, has increased steadily in the treatment of adults. Many minor surgical procedures, such as cataract extraction, hernia repair, vasectomy or endoscopy, may be carried out as day cases.

Day surgery patients are admitted for elective proced-ures, invasive investigations, minor operations or endoscopy (Box 24.1) and the majority return home again the same evening. Some day surgery units provide care for up to 23 hours. Many people prefer to have the shortest stay possible in hospital for several reasons, including:

Box 24.1 Endoscopy and laparoscopy

Endoscopy

Endoscopy is examination of internal structures using an endoscope. This instrument enables visualization of hollow organs and body cavities including the:

Endoscopes are usually made from flexible fibreoptic material but are sometimes rigid metal devices. Endoscopy is used for:

Endoscopy may cause pain and discomfort and is usually carried out under light sedation or anaesthesia (general or local).

Laparoscopy

The laparoscope is an endoscope used for investigations or ‘keyhole’ surgery within the peritoneal cavity, e.g. laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Laparoscopic surgery is carried out under general anaesthesia and the immediate postoperative careis the same as that following conventional surgery (see p. 692).

Advantages of laparoscopic surgery

The Audit Commission (2001) outlined advantages of day surgery for the NHS, which include:

There are also disadvantages of day surgery. Some procedures are not suitable for day surgery and neither are some patients. For example, some people may not be fit enough, or not fit enough on the day of surgery, due to exacerbation of an underlying medical condition, e.g. hypertension (high blood pressure). Each unit has its own criteria for acceptable travelling distance and availability of medical assistance should complications arise, and therefore people who live far from the unit may not be suitable candidates for day surgery. Some people, who although fit for day surgery, may refuse it for several reasons, including:

On discharge after day surgery, all patients – adults and children – must have a responsible adult to care for them for at least 24 hours afterwards. The patient must also have a suitable home environment within which to recover and no need to use public transport. The need for care by a significant other can cause financial hardship due to loss of earnings or high travel costs.

Emergency surgery

This is sudden and unplanned. Patients may find this very stressful for many reasons, including fear of the unknown, fear of pain or dying, fear of hospitals and fearthat far-reaching lifestyle changes may be needed. Bearingthis in mind, the nurse must assess not only patients’ physiological needs but also their psychological and emotional needs. In this situation social needs are also very important, e.g. children may be waiting at the school gate or older adults or pet animals may depend on the person being at home at certain times. It is very important to establish a trusting nurse/patient relationship quickly. This relationship can be enhanced by the way the nurse informs and involves the patient during admission and preparation for urgent surgery. Effective communication skills (see Ch. 9) are therefore essential.

Preoperative care

The aim of preoperative care is to ensure that each patient receives holistic preparation for a safe and dignified surgical experience. For emergency admissions this is accelerated and takes place very soon after admission; however, the principles are the same. It involves assessment, planning, intervention and evaluation. Preparation usually beginswith referral from the general practitioner (GP) for elective procedures. In the future this will become better organized as patients are able to provisionally pre-book admission dates through their GP.

Investigations

Some investigations are carried out routinely on all patients; others are used to confirm the diagnosis or are specific to the type of intervention being considered. Routine investigations include:

Depending on the type of surgery, some of the following may also be carried out:

A simple explanation of some of these investigations that will help you provide patient information can be found on the BBC website (see ‘Useful websites’, p. 701). More detailed information can be found in Brooker and Nicol (2003).

Pre-assessment clinics

Pre-assessment clinics enable both healthcare staff and patients to plan and prepare for elective interventions involving day surgery or an inpatient stay. This means that on admission for surgery, staff know that the patient has been well prepared and has an understanding of their care before, during and after surgery, and also following discharge. Some rural areas have pre-assessment outreach clinics that reduce time and expense for patients.

Many pre-assessment clinics are nurse led and provide a point of contact should the person/parent/carer require more information or subsequent clarification. Patients of all ages are encouraged, if they wish, to have a friend, partner or carer with them during the consultation. Children should be accompanied by their parent or legal guardian during the pre-assessment process. However, there are some circumstances in which this may not be case, e.g. where an older child is deemed mature enough to understand the procedure and its implications and is competent to make their own decisions about their care, for example, a girl of 15 years with sufficient maturity having a termination of pregnancy without her parents’ knowledge (see Ch. 6). Pre-assessment clinics for children are described in Box 24.2.

Box 24.2 Preoperative considerations for children

Paediatric pre-assessment clinics are a time for nurses to gather information about the child and for children and their parents to visit the ward and meet staff. Pre-assessment clinics are usually run as clubs, often on Saturdays, instead of formal clinics. At these clubs parents and children gain insight into the proposed intervention by learning through, for example, play (see Ch. 9) and stories with pictures. Pre-assessment visits also provide the opportunity for nurses to correct any misconceptions and allay potential fears or anxieties. Booklets are sometimes used to reinforce information and children may be sent special letters from a character that has been adopted by a ward.

Action for Sick Children (2006) highlights the value of play in hospital to reduce anxiety about surgery or invasive procedures. This website also provides useful information for parents about what to expect during hospitalization for any reason. Trigg and Mohammed (2006) suggest that clubs include not only the child and their parents but also siblings, thus involving the whole family. Once in hospital, family links can be maintained by visits and use of the telephone, text messaging or the Internet.

At the pre-assessment clinic patients have the opportunity to:

Physical health is assessed to ensure the patient will be fit for the proposed intervention. Working together, nurses and patients discuss:

It is important that everyone, including both children and parents, is provided with information in a way that is understood (see below).

Smoking cessation

Patients who smoke should be advised to give up as smoking is a risk factor for many postoperative complications, e.g. chest infections, deep vein thrombosis (DVT, p. 698), poor wound healing and pressure ulcers (see Ch. 25). Smoking cessation should start at least 2 weeks before surgery; however, this advice can have either a negative or a positive effect as withdrawal of nicotine can increase people’s stress levels. Some people find nicotine replacement therapy helpful. Nurses must not be judgemental or critical if a patient cannot heed this advice; however, information about potential postoperative complications related to smoking should always be provided.

Communication

Psychological preparation for investigative procedures orsurgery requires effective communication skills that forman essential part of holistic care. This begins at the pre-assessment clinic where patients and their relatives are able to have information clarified and questions answered using language that they understand. On the other hand, poor communication – both verbal and written – can adversely affect the way people respond and may result in abnormal behaviour, people feeling threatened and increased anxiety levels.

The nurse explains to the patient what to expect, both immediately afterwards and during the convalescent period; this can vary considerably depending on the surgery to be performed. The immediate aftercare may involve equipment including intravenous (i.v.) infusions, a wound with skin closures, etc. There may also be exercises to be carried out and dietary or mobility considerations. The steps involved in returning to previous fitness are also discussed in detail. Even when patients appear to be fully informed, they often find the preoperative waiting period stressful. Some surgery may not have a favourable outcome and this may add to people’s fears and impair their ability to cope with bad news (see Ch. 9).

Written material can reduce misunderstanding and reinforces verbal and other sources of information from health professionals; CD-ROMs and videos may also be used. This allows people to read or watch when they feel able to concentrate and is a useful reminder of what to expect. For those for whom English is not their first language, material in their own language should be provided whenever possible; sometimes an interpreter may be needed (see Ch. 9).

When faced with an impending operation, some peopleseek information from other sources including the Internetalthough there may be difficulty in fully understanding the information found there. Nurses are in an ideal position to help patients work through information from any source and ensure that their understanding is accurate. Information may have been provided, but people’s perceptions can be that it is too much, duplicated or not enough. Patients are also at risk of overlooking important information because they are selective in what they read (Otte 1996).

Benefits of providing preoperative information

Lin and Wang (2005) studied the effect of pain information given before abdominal surgery, and concluded that this information-giving could reduce pain intensity experi-enced in the immediate postoperative period (at 4 and 24 hours). Several authors have noted other postoperative benefits of providing preoperative information, including fewer postoperative complications and reduced patient anxiety (Hayward 1975, Boore 1978, Wilson-Barnett 1979, Bysshe 1988, Devine 1992), as well as improved job satisfaction for nurses who were given the opportunity to meet their patients before the day of surgery (Crawford 1999, Holmes 2005).

Common sources of preoperative anxiety

Patients are encouraged to express their fears and concerns using good interpersonal communication skills (see Ch. 9). It is important to recognize that apprehension can build up while waiting for an operation despite effective planning (Box 24.3). Fear of the unknown and loss of independence are common anxieties that can causea person to develop either introverted or extroverted behaviour. In children, this may manifest itself by a change in behaviour, e.g. withdrawal, regression, overactivity or parent dependence. Reduced contact with family and changes in daily routines can instil a feeling of lossor abandonment, especially in young children and older adults. These feelings can become exaggerated, especiallyif someone will have few, or no, visitors. The nurse can discuss these potential problems and offer suggestions such as making phone calls to their friends and family from the ward.

Preoperative anxiety

Some patients undergoing surgery report anxiety about having an anaesthetic, the possibility of waking up during the operation and being unable to tell anyone, not recovering from the anaesthetic or that they may behave inappropriately under the anaesthetic. Anxiety may also be increased when the potential prognosis is poor. Patients in unfamiliar surroundings, who have had bad previous experiences or little technical knowledge, may feel powerless.

Franklin (1974) found that anxious patients needed more information about their treatment, progress and surroundings, and also reassurance from the care team. Patients who have communication difficulties may become frustrated or upset when they are not understood (Ashworth 1980).

Sometimes a recovery room nurse visits patients on the ward preoperatively. These visits facilitate seamless care from the ward to theatre and back again, and help the patient cope with an essentially unpleasant experi-ence (Weins 1998). The nurse can talk to the patient about any fears about the anaesthetic or other issues they would like clarified, e.g. relating to fear of needles or the wearing of dentures and hearing aids until induction of anaesthesia. Patients who need initial postoperative care in a high dependency or intensive care unit may find visiting the area useful but this should not be imposed as it may increase their anxiety (Skacel & McKenna 1990).

Many people prefer to have intimate care carried out by professionals of the same gender. Cultural norms can be a source of anxiety, especially to older women, who may have had little personal contact with men, and those whose religion or culture dictates restriction of physical contact with a male who is not their husband. Nurses need to be sensitive to people’s needs and preferences by ensuring they are taken into account whenever possible. For women, a female chaperone is arranged when this is not possible. Similarly, many men prefer not to have intimate care carried out by female staff.

Surgery that changes body appearance will affect people’s body image (see Ch. 11), e.g. removal of a breast due to cancer is often a source of great preoperative anxiety. However, to other people the same surgery may bring positive outcomes despite postoperative discomfort, e.g. breast reduction or amputation of a painful gangrenous extremity.

Mitchell (2000) advocates that ideally the amount of information provided for a patient should match their preferred coping strategies (see Ch. 11). Some patients use their spirituality to help them cope. Coping strategies can be observed and discussed at the pre-assessment clinic and also at the time of admission (see Box 24.4). Identifying postoperative coping strategies beforehand may help patients to work through postoperative problems using their own stress-reducing mechanisms, e.g. yoga exercises that reduce tension may be used to assist postoperative pain management (see Ch. 23). Other strategies may include arranging a meeting with an ex-patient who has undergone the same type of surgery or a parent may be put in contact with another family that has been in the same situation. This can be of great help, as many people benefit from a personal approach.

Obtaining consent

Prior to any operation or invasive investigation people must sign a consent form for both legal and ethical reasons (see Chs 6, 7). For consent to be valid it is essential that three criteria are satisfied: that it is voluntary, that it is informed and that there is mental capacity to make the decision (see Ch. 6). Rigge (1997) reminds readers that patients have the right to ask the surgeon about their success rates, and the likelihood and nature of potential complications. The patient not only agrees in writing to the proposed invasive investigation or surgery but also to the type of anaesthesia used.

The surgeon undertaking the procedure must mark the site of operation when a limb or paired organ is involved. This is usually performed on the day of, or evening before, the operation to safeguard against later errors regarding the correct surgical site. A waterproof marker pen prevents removal of the marks during bathing or showering. The patient must be in agreement with the correct site.

While discussing impending surgery, if there is any doubt that a particular procedure may not be possible, for example when a more extensive procedure might be required, the patient should also sign for the proposed variation. Nurses must be aware that it is a patient’s right to withdraw their consent at any time. If this occurs, the charge nurse must be informed immediately. The Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) Code of Professi-onal Conduct: Standards for Conduct, Performance and Ethics (2004) points out that nurses must always respect patients’ wishes, however frustrating this may be. Consent may also be withheld in relation to an aspect of treatment (Box 24.5).

Obtaining consent

Mrs George signs a consent form for a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. During the operation complications arise and a more invasive procedure (laparotomy) is carried out to complete the surgery safely. Mrs George had been well prepared for this eventuality. She had already agreed and signed the consent form indicating that she understood and was prepared to have the more invasive procedure if the need arose.

In an emergency situation, a surgeon might operate on an unconscious patient without formal signed consent. In the absence of this the intervention must be justifiable and carried out on the basis that it is in the patient’s best interests.

Preoperative fasting

Usually patients can eat and drink normally until 2–6 hours before surgery unless the surgery involves the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. The Royal College of Nur-sing (RCN 2005) suggests that:

The reason for fasting is to ensure safety during induction of general anaesthesia by preventing inhalation of acid stomach contents into the lungs when the gag reflex is lost. Some patients, including those who are having day surgery, are admitted having fasted overnight for surgery in the morning although this is significantly longer than the RCN (2005) suggests is necessary.

Fasting (see Box 24.6) is also known as ‘nil by mouth’. Before fasting begins the local policy is explained, including the safety reasons outlined above. Water jugs and other fluids are removed from the bedside and, in the case of children, sweets and biscuits should also be removed. A sign is put above the bed or the side room door to remind those fasting and to inform others that someone is ‘nil by mouth’. Some patients may require an i.v. infusion during fasting to prevent or correct dehydration (see Ch. 19). Some patients are admitted to hospital so that their fasting regime may be monitored, e.g. people with diabetes.

Box 24.6  EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

Preoperative fasting

Hamilton Smith (1972) demonstrated that preoperative fasting time was based on ritual rather than evidenced-based practice. Recent evidence demonstrates that many patients still fast for longer than necessary (O’Callaghan 2002). The reasons for this include ritualistic practice, poor communication between theatre and ward staff and resistance to change.

Prolonged fasting can lead to fluid and electrolyte imbalance (see Ch. 19). Nausea is sometimes reported while fasting and may be due to the stress of being unable to have oral fluids, a dry mouth or the smell of food (Cronin 1996). Dean and Fawcett (2002) suggested that long periods of fasting might be a cause of postoperative nausea and vomiting. The RCN (2005) suggests that patients should normally be allowed clear fluids up to 2 hours preoperatively.

If someone who is meant to be fasting is found to have taken anything orally, this must be reported promptly to the charge nurse or anaesthetist who will decide whether it is safe for the intervention to go ahead.

Some patients who are having surgery under local ana-esthesia, e.g. removal of a toenail, may not need to fast. However, if sedation, e.g. midazolam, is required for a procedure, fasting may be necessary to avoid the risk of aspiration (inhalation of gastric contents into the respiratory tract).

In children and those who have communication problems, the nurse should also discuss effective ways of maintaining fasting with the parent or carer during pre-assessment and reinforce this on admission. Fasting should be implemented without causing undue stress, otherwise it may become an issue.

When a patient is admitted as an emergency, the last time they had food or fluids must be clearly established. In emergency situations a tube may be passed into the patient’s stomach to aspirate the contents, thereby redu-cing the risks from inhalation of gastric contents.

Skin preparation

Preoperative skincare involves cleaning the skin and sometimes removing hair from the surgical site. The aim is to reduce the normal flora but also potentially harmful (pathogenic) microorganisms (see Ch. 15) that may be present on the skin or hair. Practice in these respects varies and the available evidence is largely inconclusive.

If the person is fit, a warm shower is preferable to a bath as running water rinses off loose hair and dead skin cells more readily and showering is also a cultural requirement for many people. Care is taken not to wash off any marks indicating the operation site. The patient is encouraged to wash their hair, as some may be unable to wash their hair for several days postoperatively. People undergoing head and neck or eye (ophthalmic) surgery may be given specific instructions for hair washing.

Hair removal

Nurses must be sensitive to patients’ dignity and recognize that body hair contributes to people’s body image and cultural identity, and therefore hair removal may be distressing. The reasons for hair removal are explained and patients should be encouraged to do this them-selves when possible, although the outcome should be checked prior to the final preparations for surgery (Box 24.7).

Box 24.7  EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

Preoperative hair removal

AORN (2002) recommend that the site should be inspected for potential problems such as warts, rashes or acne prior to choosing the method of hair removal. Depilatory cream can be used but a small area (test patch) must be tested first to ensure there is no allergy. In areas where the hair is particularly thick, cream may not be effective. Wet shaving with warm soapy water softens the hair, making it easier to remove and reduces microabrasions. Hair can also be removed using clippers with disposable heads, thus reducing the incidence of cross-infection. McIntyre and McCloy (1994) stated that using razors carried a higher risk of infection than depilatory creams or clippers and that hair removal should take place not more than 2–3 hours before surgery to reduce bacterial colonization within microabrasions. In some specialities, e.g. orthopaedics and plastic surgery, preoperative skincare following hair removal is carried out using antiseptic solutions such as chlorhexidine. AORN (2002) stated that topical antiseptics should be chosen carefully to prevent hypersensitivity reactions such as blisters and rashes.

Preventing potential postoperative complications

Many postoperative complications can be prevented or minimized by effective preoperative care. This sec-tion explains nursing interventions undertaken to achieve this.

Chest infection

This can be both life threatening and debilitating, and people at increased risk include:

At the pre-assessment clinic patients are given information about deep breathing exercises that minimize the risk of chest infection (see Ch. 17). Some people attend physiotherapy classes to learn these exercises and how to support their wounds when they need to cough postoperatively. Others are provided with written instructions to follow at home. People’s knowledge is assessed on admission to ensure it is adequate and appropriate.

Deep vein thrombosis

A deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is the formation of a thrombus (clot) in the deep veins of the legs or pelvic veins (see Ch. 17). Pulmonary embolism (blockage of a pulmonary artery by a detached thrombus that has travelled there in the bloodstream) is a potentially fatal consequence of DVT that must be prevented when possible and is the reason for the care described below.

Several aspects of surgical treatment increase the risk of DVT. Immobility is a major risk factor that occurs during invasive procedures and surgery, and also postoperatively to a greater or lesser extent depending on the nature and length of the intervention. The nurse explains the leg exercises that will reduce the incidence of a DVT (see Ch. 18) so that patients can practise them preoperatively and implement them postoperatively to improve and maintain venous return and also to prevent stiffness of the joints. Further measures, e.g. stopping hormone replacement therapy (HRT), prophylactic heparin and anti-embolism stockings (see Box 24.8) may also be implemented to minimize occurrence of a DVT.

Anti-embolism stockings

Bowel preparation

Bowel preparation prior to surgery aims to prevent:

Emptying of the bowel can be achieved by administration of oral or rectal laxatives (see Chs 21, 22). For procedures involving the lower GI tract, specific bowel cleansing laxatives, such as sodium picosulfate, may be prescribed, together with prophylactic antibiotic therapy. These patients may undertake some of their bowel preparation in the comfort of their own homes.

Any bowel preparation can cause distress, which can begreatly reduced by effective nursing intervention. Good communication is essential to ensure that the patient receives the correct preparation and understands why it is necessary (Finlay 1996). The patient’s ability to reach the lavatory promptly and safely is assessed (other nursing considerations are discussed in Ch. 21). Dehydration can occur during extensive bowel preparation, even when patients have achieved the recommended fluid intake. It is therefore important to be aware that headaches or changes in behaviour, such as loss of concentration, can be signs of dehydration. When extensive bowel preparation is carried out it may be necessary to commence an i.v. infusion to:

Final preoperative care

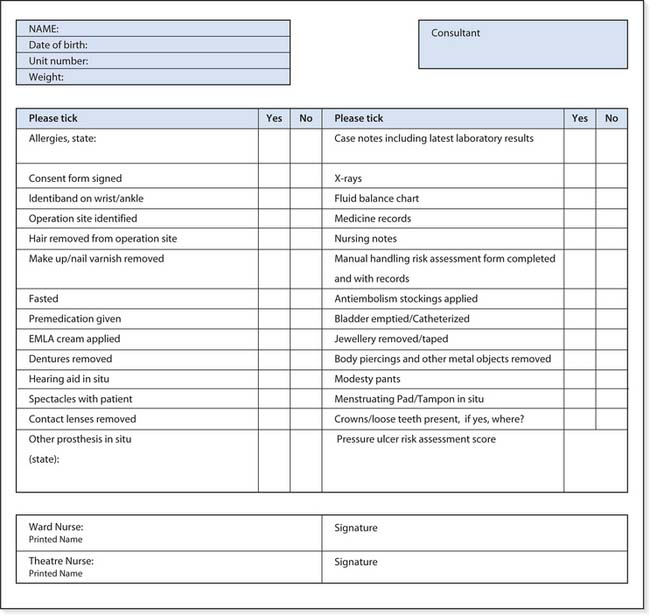

The nurse must implement local policies to prepare the patient safely for theatre. A checklist of specific measures is often used (Fig. 24.1).

Emptying the bladder

The bladder is emptied before showering so that the perineal area is clean. An empty bladder will prevent urinary incontinence during surgery and damage to the bladder during pelvic surgery. For patients having extensive surgery, pelvic surgery and epidural or spinal anaesthesia, a urinary catheter is passed (usually in theatre) to ensure that the bladder remains empty and that urinary output can be measured accurately postoperatively (see Ch. 20). However, if there is a long delay and/or the patient becomes anxious, they may need to pass urine again before transfer to theatre.

Theatre clothing

After showering or bathing, the patient wears a clean hospital gown. As the skin continuously sheds dead surface cells and commensal bacteria (see Ch. 15), a clean gown ensures that the skin is exposed to the minimum pos-sible number of bacteria after showering. The bed is madeusing clean sheets for the same reason. Theatre gowns usually open down the back so that they can be easily removed during surgery if necessary. Female patients can wear disposable paper pants or clean cotton knickers for some procedures, depending on local policy. If anti-embolism stockings are needed, the correct size should be used (see Box 24.8).

James (1995) advocates that children should be able to choose what to wear, arguing that theatre gowns are not necessary and removal of underwear can be distressing and bewildering.

Removal of cosmetics, jewellery and prostheses

Cosmetics are removed so that skin colour changes, e.g. pallor, can easily be observed. Nail varnish is also removed so that the nail beds can be assessed for early signs of cyanosis (see Ch. 17).

Jewellery, hairclips or ornaments are removed and stored safely according to hospital policy and taking into consideration cultural and religious needs. Plain rings that cannot be removed, or for patients who prefer them not to be removed, are taped securely to the finger using hypoallergenic tape. Removal of metal objects prevents:

Patients may be asked to remove prostheses such as wigs, false eyes or artificial limbs on the ward to prevent their damage or loss. Removing a wig may cause embarrassment and a patient’s dignity can be maintained by allowing it to be worn until after they are anaesthetized. If the wig has to be removed, the patient should be offered a paper cap to cover their head. Patients who have long hair should have this tied back on the top of their head so that it does not hinder extension of the neck during induction of anaesthesia.

Contact lenses are removed to prevent corneal abrasions during anaesthesia and are stored safely on the ward. Spectacles may also be removed and stored on the ward although many people are less anxious if any prosthesis can be worn to the anaesthetic room.

Hearing aids are worn to theatre to maintain effective communication and only removed after the patient is anaesthetized, when they are carefully removed, labelled and stored in the recovery room until consciousness is regained.

The presence of loose teeth, caps or bridges is written on the preoperative checklist as these can be damaged or dislodged during intubation or insertion of an airway. Removal of dentures can be a source of embarrassment and dignity should be considered by offering patients the option of keeping them in place until they are anaesthetized (Wood 2002). Dyke (2000) also considers their removal on the ward to be unnecessary as they maintain effective interpersonal communication.

Allergies

Any allergies must be checked with the patient and clearlyentered on the preoperative checklist to prevent administration of harmful medication or skin preparations. Common allergies include adhesive tape, antibiotics (especially penicillin), iodine and anaesthetic gases.

Identity bands

These are worn to ensure that patients can always be easily identified, especially when they are unable to communicate effectively, e.g. due to anaesthesia or sedation. Sometimes local policy requires identity bands on both wrists, ensuring that if one is cut off, a patient can still be easily identified. Identity bands must be checked for legibility and accuracy each time a patient is moved between environments and when medication is administered. Patients having upper limb surgery may have identity bands round their ankles.

Premedication

Premedication is rarely used before day surgery. Other patients may be prescribed premedication, usually a light sedative or hypnotic (see Ch. 22), to reduce preoperative anxiety. Sometimes an anticholinergic drug such as hyoscine is given to reduce oral and bronchial secretions and vagal overactivity. Reducing secretions lessens the incidence of their inhalation during induction of anaesthesia when the gag reflex is lost. Premedication is administered approximately 1 hour before transfer to the anaesthetic room. When preoperative prophylactic heparin is prescribed, it is administered at the same time as the premedication.

Patients who have been given sedative drugs must remain in bed afterwards as the effects can make them unstable should they stand up. It is essential to check that the patient has signed their consent form before administering sedation. The call button is placed within easy reach and bedrails may be raised depending on local policy. When bedrails are used, the nurse must explain that this is for safety reasons as use of bedrails for restraint is unethical (see Ch. 7).

Preparation for intravenous cannulation

Preparation for i.v. cannulation is especially important in children and those who have needle phobia. Topical anaesthetic cream such as EMLA (eutectic mixture of local anaesthetic) minimizes pain during i.v. cannulation and takes approximately an hour to act (Fitzsimmons 2001; also see Ch. 23).

Final preoperative checks

The completed preoperative checklist and the patient’s documentation, including their current observation charts, are collected together so that they are ready to accompany the patient to theatre. Doctors are responsible for preparation of the medical notes, which must include the signed consent form, relevant blood test results and X-rays. The nurse may also check that these are available on the day of surgery. The nursing records include the completed preoperative nursing checklist, nursing care plan and medicine records. Patients who have an i.v. infusion in progress or specific medication such as insulin may also have other records, e.g. a fluid balance chart.

Prior to transfer to the operating theatre the registered nurse and the theatre porter ensure that the correct patient is taken by checking their identity band for the correct:

The bed space is then prepared to receive the patient on their return from surgery (see Box 24.9). Carrying out the activities in Box 24.10 will help you understand a patient’s perioperative experience.

Preparation of the bed space

This enables straightforward monitoring of postoperative progress and may involve moving the bed nearer to the nurses’ station and assembling equipment, including:

Perioperative care

Student activities

Select a patient who is to undergo surgery and negotiate their permission for the activities below. Ask your mentor if you can follow them from your placement to theatre, recovery and back to the ward.

Consider the extent to which preparation was effective in providing the patient with a realistic expectation of their perioperative experience.

Perioperative care

Adults are usually transferred to theatre on their beds or theatre trolleys. In day surgery settings, patients may be able to walk to the operating theatre if they have not been given premedication. Children are usually accompanied to the anaesthetic room by a parent and they may be transferred on child-friendly equipment, e.g. a Thomas the tank engine truck. They often take something personal and comforting with them such as their favourite teddy, doll, toy or comfort blanket. Small children may be carried by a parent or taken on a trolley depending on local policy.

Anaesthetic room

On arrival the receiving nurse checks the name, unit number, date of birth and the proposed surgery with the patient. The preoperative checklist is checked again and countersigned by the receiving nurse to ensure that all the measures required to protect the patient have been carried out. The patient is transferred to the operating table in preparation for the operation and is then ready for their anaesthetic.

Anaesthesia

Anaesthetics block sensation from the operative site so that surgery or investigations are not painful. There are three different types:

Theatre

In theatre all care is provided by experience practitioners. More information about what is involved can be found in Further reading suggestions (e.g. Morris & Ward 2003).

Recovery room

Postoperative care is carried out to ensure safe recovery from the anaesthetic and operation or invasive procedure, and to minimize potential postoperative complications. Parents are encouraged to come to the recovery room to be with their child as they wake up after surgery.

Information about the patient’s anaesthetic including all drugs, i.v. fluids and blood given during surgery is given to the recovery room nurse by the anaesthe-tist. Oxygen is often prescribed at this time. The surgeon explains the details of the operation including the type of skin closures, wound drains used and any specific care required. This information enables the recovery room nurse to plan the immediate postoperative care. The priorities of postoperative recovery (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network 2004) are to maintain:

The patient is orientated and made comfortable in the recovery position (see Fig. 16.17) until they are fully conscious again. Pain is assessed and analgesia given if required. Personal effects such as a hearing aid, wig, false eye or facial prosthesis worn from the ward are returned to maintain dignity.

After a spinal or epidural anaesthetic the patient will have loss of sensation in their lower limbs for several hours. Positioning and support of the legs is important. Blood pressure recordings may also be affected during this period.

Discharge from the recovery room

A scoring system is normally used to assess when patients are fit enough to be transferred safely from the recovery room. Prior to discharge the equipment needed for safe transfer back to the ward is assembled, e.g. a portable oxygen system or drip stand. Extra blankets may be needed to prevent heat loss. The notes are checked and assembled, ensuring prescriptions for oxygen, i.v. fluids and analgesia, if needed, are completed. The ward nurse identifies the correct patient. The recovery room nurse provides a handover to the ward nurse prior to transfer.

Postoperative care

Postoperative care begins in the high dependency setting of the recovery room (see above) and continues through discharge from hospital until convalescence is complete. Its aims are to promote recovery and minimize post-operative complications. The principles and milestones after return to the ward are explored in this section.

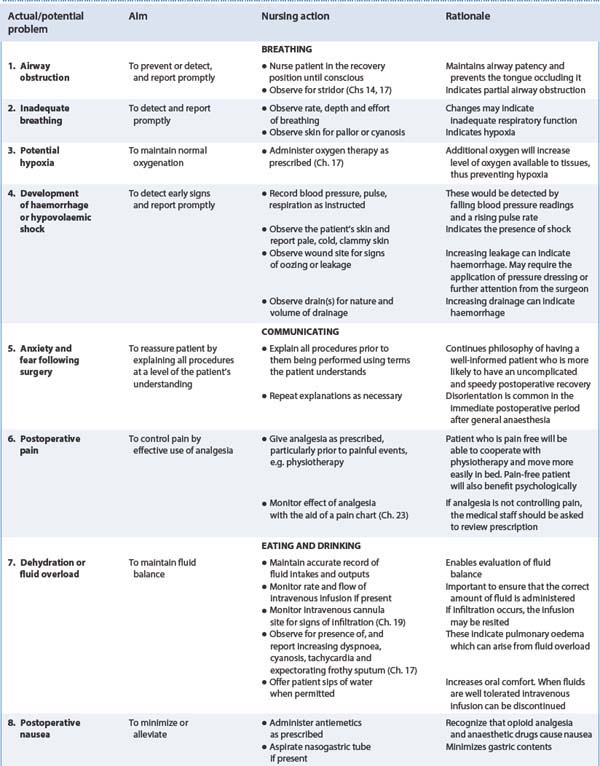

Postoperative baseline assessment

On return to the ward a registered nurse completes the initial assessment of the patient’s condition, which forms the basis of their postoperative care. This starts with airway, breathing and circulation, and comprises a new set of observations, which include:

Any abnormal trends or readings are reported to the charge nurse immediately.

Airway

Assessment begins with checking that the airway is clear and that breathing is quiet. The airway is maintained by ensuring that the head is positioned so that air entry into the lungs is not impeded. The position of the head should allow the tongue to drop forward so that secretions can drain or pool in the side of the mouth where they can be removed using suction. Adequate oxygenation is assessed using a pulse oximeter to measure oxygen saturation levels. Patients are not discharged from the recovery room until they can maintain their own airway.

Breathing

Respiratory rate is recorded every 15 minutes initially to ensure that it is stable, regular and within acceptable limits for the particular patient.

Circulation

This is assessed by feeling the skin, which should be warm to touch, and observing the nail beds, which should be pink. Insufficient oxygen in the blood (hypoxaemia) can give the skin a bluish tinge, especially around the lips and nail beds.

Measurement of blood pressure and pulse also indicate whether the circulation is adequate. Changes that suggest development of shock are:

There are different causes of shock but postoperatively the most common is due to hypovolaemia, which occurs when the circulating blood volume is reduced following excessive blood loss. For more detail, see Further reading suggestions (e.g. Adam 2003).

Observations

The intervals between recordings (see above) must be clearly stated on the care plan. Initially these may be every 15 minutes for the first hour then adjusted when they are within an acceptable range for that patient.

Drains should be supported to avoid traction on the tubing and to prevent potential dislodgement or poor drainage. The amount, consistency and type of drainageinto the drain, as well as any fresh staining on the theatredressing, are noted during the initial postoperative assess-ment so that subsequent loss can be measured. Drains are checked for flow and patency if a vacuum system is used (see Fig. 24.2). If patency is lost, leakage from the wound may increase. The type of drain and volumes draining dictate the frequency of checking.

Urinary catheter drainage tubing should be positioned to allow free drainage, ensuring that the collecting bag doesnot come in contact with the floor (see Ch. 20). Urinary output may be measured hourly depending on the patient’s condition and the type of surgery. All drainage is recorded on the fluid balance chart as per local protocol.

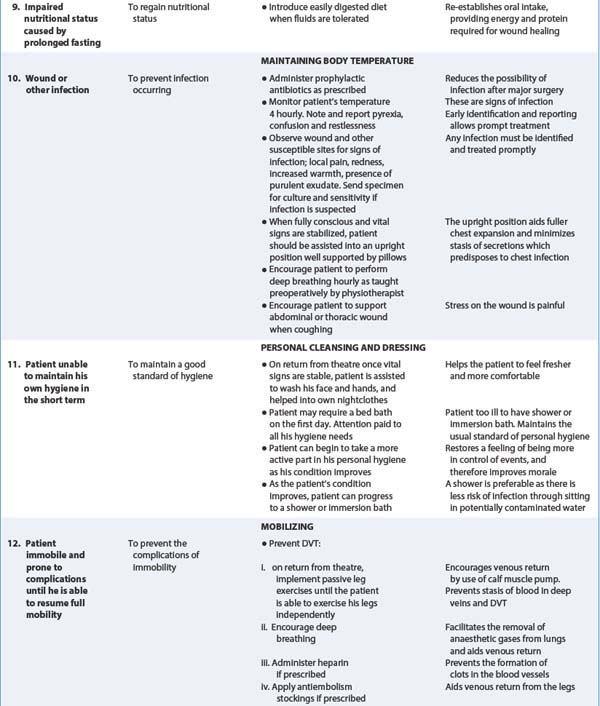

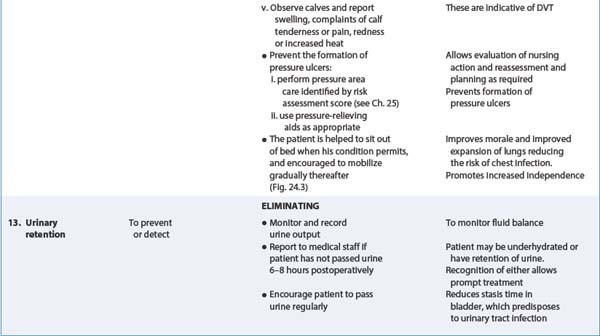

Postoperative care is outlined in Table 24.2, the most important principles of which are explored in more detail below.

Communication

When the patient is safely settled, the nurse reorientates them to the ward and explains that the procedure is complete. The environment may be full of unfamiliar sounds which will have been explained preoperatively but this is often forgotten in the immediate postoperative period and should be included in the reorientation information. For patients who wear hearing aids, it is important to check that they have been reinserted and are working correctly. Hearing is the first of the senses to return after a period of unconsciousness and for this reason staff must avoid discussing patients’ conditions near the bedside. At this stage, children often ask for their parents. The sound of the parent’s voice gives reassurance and comfort that allows a child to rest and recover.

Maintaining dignity

Patients are vulnerable postoperatively and it is important to maintain their dignity at all times. Replacing a patient’s prosthesis aids their dignity and also improves their body image. Dentures are usually returned in the recovery room when the patient regains consciousness. However, if this was not the case, then oral hygiene should be given and their freshly rinsed dentures returned. Xavier (2000) points out that people who have worn dentures for a long time are able to manoeuvre them into the correct place even when they are very drowsy.

Pain management

Chapter 23 addresses this topic in depth and should be consulted for further information about all aspects of pain management. Postoperative pain management begins preoperatively when the available options are discussed with the patient. Postoperatively, the nurse must ensure the patient is comfortable and given adequate pain relief. Effective pain management reduces postoperative anxiety (Hayward 1975) and aids mobility. Patients expect to encounter some pain following a surgical intervention but only to their degree of tolerance. Carr and Thomas (1997) found that although patients expected to have pain following day surgery, some stated this was significantly greater than expected. Furthermore, Coll and Ameen (2006)found that many patients have inadequate pain relief after discharge. Pain is not necessarily wound related and can be due to dehydration, a full bladder or the after-effects of being on the operating table. Pain may adversely affect postoperative recovery and is assessed and documented using a pain assessment chart.

Individual coping mechanisms in relation to pain vary widely. Some people lie as still as possible, hoping that the pain will subside, whereas others become very vocal. Other people cannot verbalize their pain, e.g. young children and those with learning disabilities, and nurses need to be alert to behavioural cues. Drugs used in pain management range from mild analgesics such as ibuprofen for mild pain to opioids, e.g. morphine, for moderate to severe pain. Several routes may also be used, including:

PCA devices deliver preset doses of analgesic drugs and allow patients to give themselves analgesia by pressing a button on the handset. Tye and Gell-Walker (2000) suggest that PCA reduces patients’ anxiety about experi-encing postoperative pain. It can be used by people of all ages provided they have sufficient understanding and the manual dexterity to push the delivery button. Some patients may use non-pharmacological methods of pain relief, such as visual imaging or yoga exercises (see Chs 10, 23), which may reduce the amount of analgesic drugs needed. The activities in Box 24.11 will help you understand postoperative pain management.

By anticipating the need for analgesia and speaking to patients about their pain levels well before increased activity is needed, e.g. chest physiotherapy, bed bathing/ showering, getting out of bed and mobilizing, nurses can minimize pain experienced during these activities.

Patients should be encouraged to change their position in bed and to carry out their therapeutic exercises, e.g. leg and deep breathing exercises. This helps to reduce general discomfort and enables people to feel more in control of their postoperative recovery. The nurse will help the patient feel safe at all times by leaving the call button within reach and answering it promptly.

Fluid balance

All intakes and outputs are recorded accurately on the fluid balance chart until urine output and oral fluids are re-established. Fluid balance charts are explained fully in Chapter 19 and this section outlines the fluid intakes and outputs recorded postoperatively.

Fluid intake

Re-establishing oral fluids following surgical interventions depends on the type of procedure and local policy. Some day surgery patients or those who have had a spinal or epidural anaesthetic may be able to drink immediately they are fully orientated. Those who have had anaestheticthroat spray administered prior to upper endoscopic investigations or ear, nose and throat procedures must remain ‘nil by mouth’ until the swallowing reflex returns (usually around 2 hours afterwards). When there has been handling of the intestines, the period of fasting is more prolonged due to paralytic ileus (see p. 699).

The site of an i.v. infusion can reduce mobility and manual dexterity such as cleaning the teeth. Once an adequate oral intake is re-established without complications, the i.v. infusion can be discontinued but a fluid balance chart is still required until the patient can maintain the required fluid intake.

For adults, an i.v. fluid regime over a 24-hour period normally comprises approximately 3L of fluid consisting of 0.9% saline (normal saline) and 5% dextrose. Smaller volumes are required for children, older adults and those with cardiovascular problems (see Ch. 19). Adequate i.v. fluids ensure an adequate blood supply to the kidneys that maintains renal perfusion and urinary output (see below). This is essential to prevent kidney failure. Intravenous fluids are administered to replace fluid deficits due to:

Infusion pumps may be used to administer prescribed i.v. fluids but nurses using them must have a working knowledge of their use and the potential complications (see Ch. 19).

Intravenous medications, e.g. antibiotics, are also recorded on the fluid balance chart as they can be a significant part of fluid intake. The fluid balance is reviewed regularly to ensure that the patient is not in negative balance or fluid overloaded (see Ch. 19).

Nausea and vomiting

Nausea and vomiting sometimes occur following an anaesthetic or handling of the viscera during abdom-inal surgery, and also when people are in pain or anxious about the future (Jolley 2000). Postoperative nausea and vomiting may be due to accumulation of gas within the GI tract or from hiccups due to the irritation of the diaphragm. Fluid loss due to vomiting is measured and recorded on the fluid balance chart. Vomiting can cause depletion of water and electrolytes.

Postoperative nausea and vomiting can be reduced if the patient is administered a prophylactic antiemetic, e.g.domperidone, before or during surgery. However, even if an antiemetic has been given, some patients may still continue to experience nausea for several days postoperatively. They can be reassured that the feeling will subside and there are several nursing interventions that may help:

Urine output

Adults, including those who have an indwelling urinary catheter, should pass a minimum of 30 mL of urine per hour. Smaller volumes are normal in children (see Ch. 20). The well-hydrated patient should be able to void urinewithin 6–8 hours following a general anaesthetic. Inability to void following surgery may be due to:

When there is failure to pass urine following surgery or a significant drop in hourly urine output, this is reported to the charge nurse. It is important to note that small volumes may represent overflow due to a full bladder and urinary retention (see Ch. 20) or negative fluid balance (see Ch. 19). If there is difficulty in passing urine and the patient is in pain, analgesia should be administered as this may help them to relax and void. If all these interventions fail, it may become necessary to pass a catheter to drain the bladder. This is retained until hydration is satisfactory and urine volumes are sustained. The closed catheter system must be allowed to drain freely and specific nursing care is required (see Ch. 20). Urine output is recorded on the fluid balance chart.

Nasogastric aspirate

Wide-bore nasogastric tubes are used postoperatively to withdraw (aspirate) gastric secretions that accumulate when paralytic ileus (see p. 699) is present, e.g. following surgery that involves the stomach or the small or large bowel. The frequency of aspiration is dictated by the type of surgery and patient discomfort. This may be continuous using a low-pressure suction unit or intermittent using a suction unit or syringe. The nasogastric tube may be attached to a collecting bag to allow the free passage of gas and drainage of gastric secretions. These may increase with abdominal pressure, e.g. when the patient coughs, breathes deeply or moves around to change position.

The colour and presence of blood of each aspirate is noted and the volume recorded on the fluid balance chart. Sometimes the consistency is also recorded.

The disadvantages of a nasogastric tube include:

The nursing care required by a patient with a nasogastric tube is shown in Box 24.12.

Care of a patient with a nasogastric tube

Wound drainage

Wound drains (see Fig. 24.2) are used to drain fluid away from surgical sites, especially vascular areas. Fluid may be:

A collection of fluid in a confined space causes pain, acts as a potential source of infection and impairs wound healing (see Ch. 25). The function of the drain is explained to the patient preoperatively and also the need to avoid putting traction (pulling) on it, especially when moving around in bed and up walking.

Preventing chest infections

Patients are encouraged to take deep breaths hourly postoperatively and to cough as necessary to aid lung expansion and to expel anaesthetic gases and pooled respiratory tract secretions. Poor lung expansion and pooling of secretions predispose to chest infections. The physiotherapist educates patients preoperatively (see p. 688) about these exercises. Chest physiotherapy and/or early mobilization can help to reduce the incidence of chest infection and the need for antibiotics (see Ch. 17). In order to carry out deep breathing and coughing, the patient should have enough pain relief and support for chest or abdominal wounds. Placing a hand or pillow firmly over the wound can provide support.

Signs of chest infection include:

A sputum specimen may be required for culture and testing of sensitivity to an appropriate antibiotic (see Ch. 17).

Prevention of deep vein thrombosis

Preoperative preparation helps to reduce the incidence of DVT (see p. 688). Preventative postoperative measuresinclude:

The incidence of DVT is higher after major surgery of the lower abdomen, pelvis and hip joints than other surgery. Not all patients who undergo surgery need these interventions as early mobilization and day surgery reduce the incidence of DVT.

The presence of pain, swelling or redness in the lower limbs is reported urgently, as these may be early signs of a DVT. It is important, however, to realize that the majority of DVTs cause no local signs and that some arise in the pelvic veins.

Nutrition

Preoperative nutritional assessment is carried out so that nutritional intake can be adjusted to meet each patient’s needs. Poor nutrition affects many body processes and has widespread postoperative consequences, including:

Patients who are not undergoing major surgery are usually able to eat normally again within 12 hours. Those who have been fasting for some time may be reluctant to recommence solid food for fear that their preoperative symptoms will return. Patients may need assistance to select a diet that meets their nutritional needs in the postoperative period. Meals and snacks should be served appropriately, taking people’s medical and cultural needs into consideration (see Ch. 19).

Sometimes it will not be possible for patients to eat for several days or even weeks, such as after removal of large parts of the GI tract, and a preoperative referral to the dietitian should be made. Others cannot eat sufficient food to meet their energy requirements and food fortification or nutritional support may be used to prevent malnutrition (see Ch. 19).

Preventing constipation

Patients may not pass faeces or flatus (gas) for several days postoperatively, especially when there is paralytic ileus or following preoperative bowel cleansing. Paralytic ileus occurs after surgery that involves extensive hand-ling of the bowel when peristalsis (the muscular movements that normally move contents along the intestines) is temporarily lost. Flatus is passed when peristalsis returns. Before then many patients experience discomfort caused by trapped wind.

Opioid drugs predispose to firm stools or constipation. Postoperative passing of faeces is recorded in the nursing notes. The faeces may be watery at first and stools may take time to form normally again, even after a normal diet has been re-established. Laxatives (oral or rectal, see Ch. 21) are not normally necessary when patients are well hydrated, eating normally and ambulant again.

Regaining mobility

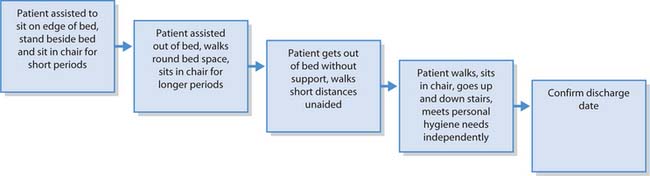

The type of surgery dictates the level of mobility and the timescale over which this can be achieved. Nurses must be aware of a patient’s preoperative mobility when planning their postoperative mobility goals. Patients having day surgery are mobilized soon after the procedure is completed. Those who undergo major surgery without complications can usually walk to the bathroom the day after surgery; however, following some specific types of surgery, e.g. major vascular surgery (femoral popliteal bypass), bed rest for 24–48 hours may be required.

Preoperatively, patients are supplied with information about exercises that they can practise and implement soon after surgery (see p. 688). The nurse should encourage the patient to carry out these exercises to reduce limb stiffness and aid venous return. When patients are unable to exercise by themselves the physiotherapist and nurse perform passive exercises (see Ch. 18).

Postoperative mobility extends from moving around in bed to walking independently and being able to climb stairs. Gradual mobilization (Fig. 24.3) may start with a short walk from the bed to a chair when the patient is able to sit out of bed for short periods. When a patient stands up too quickly, this can cause faintness due to postural hypotension (a rapid drop in blood pressure on standing upright). The patient should be moved slowly from a semi-recumbent position to the edge of the bed before being helped to stand up (see Ch. 18). Moving from the bed to a chair must be assessed and carefully planned, especially when assistance of nurses or a hoist is needed (see Ch. 18). Walking distances and periods spent out of bed are increased gradually as the patient’s condition allows until independence is regained. Patients who have had orthopaedic surgery may have specific mobil-ization programmes. The physiotherapist implements the planned activities with the nurse in a supporting role until the patient is confident and can mobilize safely.

Wound care

On completion of surgery, the incision is usually covered with a light dressing that consists of a thin non-adherent pad with a hypoallergenic adhesive cover if the skin is healthy and intact. The pad absorbs any exudate, which is usually minimal in a surgical wound and may be bloodstained initially. The dressing provides an ideal environment for healing and protects the wound from minor trauma and entry of bacteria (see Ch. 25). The aim of wound care is to promote healing and prevent infection. Healing can be compromised by many factors, including:

According to local protocol, the theatre dressing should be left in situ for at least 24–72 hours unless there is excessive staining as this has been shown to reduce infection rates following surgical interventions. If the wound is clean and dry after the initial dressing has been removed, the patient can shower and carefully pat the wound area dry with a clean towel to prevent trauma or potential infection.

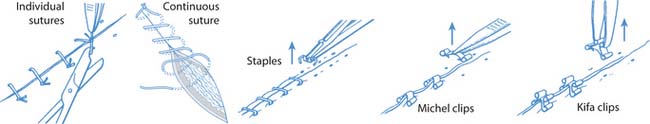

Surgical wounds normally heal by primary intention because skin closures, e.g. sutures, staples, glue or clips (Fig. 24.4), are used to hold and support the skin edges together as healing takes place. The superficial layers close within 24–72 hours as epithelial cells migrate across the wound and initially the wound may appear inflamed, e.g. red and swollen. Wound healing is discussed in detail in Chapter 25.

Both adults and children may find the removal of skin closures frightening and the procedure is explained to reduce fear and anxiety. Distraction, e.g. talking to the patient while removing skin closures, often greatly reduces anxiety.

Sutures are usually removed after 5–10 days unless theyare absorbable whereas staples are normally removed after 2–5 days. More specifically, their removal depends on the reason for surgery, its location and the patient’s age and general condition. If a patient is discharged before skin closures are removed, then arrangements must be made for their removal by a community nurse.

Wound complications

Discharge planning

Discharge planning should begin at the pre-assessment clinic or on admission to hospital in emergency situations. Successful discharge planning provides a seamless transition between day or inpatient care and primary health care. Attending a pre-assessment clinic facilitates planning and enables patients, their families and carers to understand planned interventions, the likely aftercare and its implications. Care required after discharge is planned in partnership with the patient and their family or carers, the primary healthcare team and social services. Many factors must be taken into account, including:

Some patients may be too distressed to think about their aftercare due to fear of an adverse postoperative outcome; in such cases the nurse can talk through potential scenarios to provide insight into potential needs.

Following surgery, including day surgery, people need at least a short period of convalescence. Planning an admission date helps patients to organize help at home during their convalescence. People with specific needs may have a home assessment arranged. Occupational therapists (OTs) can assess the patient’s home environment and postoperative needs. They can then provide advice and supply aids, e.g. raised toilet seats or walk-ing frames to assist following surgery such as hip replacement.

Other members of the MDT, such as social workers, may also be involved in discharge planning as some patients will be unable to care for themselves independently following surgery and therefore require a package of short- or long-term aftercare. Sometimes a period of rehabilitation (see Ch. 11) or convalescence in a care home is arranged until the patient can safely return home. Delayed discharge planning prolongs hospital admission until suitable arrangements can be completed and inadequate planning not infrequently results in readmission. Hospitals usually have discharge policies working in partnership with other agencies such as primary healthcare and social services to provide a seamless return home from hospital.

Discharge planning is important for all patients, but especially following day surgery and those who require arranged transport home and/or assistance from community services after discharge.

Before discharge surgical patients are given information about mobility, pain and wound management. This should be both verbal and in writing as this gives the patient a point of reference after discharge. Time should be spent discussing lifestyle issues including:

Having this information before discharge reduces stress and gives patients the opportunity to plan their convalescence and resumption of their normal activities and routines.

| Ethnic minority groups | www.minorityhealth.gov.uk |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Investigations BBC 2005 | www.bbc.co.uk/health/talking/tests |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Patient information leaflets | www.patient.co.uk/pils.asp |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Surgery | www.yoursurgery.com |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Wound care | www.smtl.co.uk |

| Available July 2006 |

Action for Sick Children. 2006 What to do when your child goes into hospital. Online. Available: http://www.actionforsickchildren.org/parentshospital.html.

AORN. Recommended principles for skin preparation of patients. AORN Journal. 2002;75(1):184-188.

Ashworth PM. Care to communicate. London: RCN, 1980.

Audit Commission. Audit Commission for Local Authorities and the National Health Service in England: A short cut to better services: day surgery in England and Wales. London: TSO, 2001.

Boore JRP. Prescription for recovery. London: RCN, 1978.

Brooker C, Nicol M, editors. Nursing adults. The practice of caring. Edinburgh: Mosby, 2003.

Bysshe J. The effect of giving information to patients before surgery. Nursing. 1988;3(30):36-39.

Carr CJ, Thomas VJ. Anticipating and experiencing postoperative pain: the patient’s perspective. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 1997;6:191-201.

Coll A, Ameen J. Profiles of pain after day surgery: patient’s experience of three different operation types. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2006;53(2):178-187.

Crawford B. Highlighting the role of the perioperative nurse – is preoperative assessment necessary. British Journal of Theatre Nursing. 1999;9(7):309-311.

Cronin P. How it feels to be nil by mouth. Nursing Times. 1996;96(46):44.

Dean A, Fawcett T. Nurses’ use of evidence in preoperative fasting. Nursing Standard. 2002;17(12):33-37.

Devine EC. Effects of psychological care for adult surgical patients: a meta-analysis of 191 studies. Patient Education and Counselling. 1992;19(2):129-142.

Dyke M. Pre-operative communication. In: Hind M, Wicker P, editors. Principles of perioperative practice. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2000. pp. 66–76

Finlay T. Making sense of bowel preparation. Nursing Times. 1996;92(45):38-39.

Fitzsimmons R. Intravenous cannulation. Paediatric Nursing. 2001;13(3):21-22.

Franklin B. Patient anxiety on admission to hospital. London: RCN, 1974.

HamiltonSmith S. Nil by mouth. London: RCN, 1972.

Hayward J. Information: a prescription against pain. London: RCN, 1975.

Holmes J. Preoperative visiting: landmarks of the journey. British Journal of Perioperative Nursing. 2005;15(10):434-443.

James J. Day care admission. Paediatric Nursing. 1995;7(1):25-29.

Jolley BA. Postoperative nausea and vomiting: a survey of nurses’ knowledge. Nursing Standard. 2000;14(23):32-34.

Lin L, Wang R. Abdominal surgery, pain and anxiety: preoperative nursing intervention. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2005;51(3):252-260.

McIntyre FJ, McCloy R. Shaving patients before operation: a dangerous myth. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 1994;76:3-4.

Mitchell M. Nursing intervention for preoperative anxiety. Nursing Standard. 2000;14(37):40-43.

Nursing and Midwifery Council. Code of professional conduct: standards for conduct, performance and ethics. London: NMC, 2004.

O’Callaghan O. Pre-operative fasting. Nursing Standard. 2002;16(36):33-37.

Otte DI. Patients’ perspective and experiences of day case surgery. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1996;23:1228-1237.

Rigge M. Dr. Who. The Health Service Journal. 1997;107(5570):24-26.

Royal College of Nursing. 2005 Perioperative fasting for adults and children. Online. Available: http://www.rcn.org.uk/publications/pdf/guidelines/PerioperativeFastingAdultsandChildren-002779.pdf.

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). Postoperative management in adults. Guideline No. 77. Edinburgh: SIGN, 2004.

Skacel C, McKenna F 1990 Patients’ perception of orientation to the intensive therapy unit pre-operatively. Nursing Monograph 10.

Trigg E, Mohammed T. Practices in children’s nursing. Guidelines for hospital and community, 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2006.

Tye T, Gell-Walker V. Patient controlled analgesia. Nursing Times. 2000;96(25):38-39.

Weins A. Preoperative anxiety in women. AORN. 1998;68(1):74-88.

Wilson-Barnett J. Stress in hospital: patients’ psychological reactions to illness and healthcare. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1979.

Wood M. What do patients want to happen to their dentures before surgery. British Journal of Nursing. 2002;11(15):1027-1031.

Xavier G. The importance of mouth care in preventing infection. Nursing Standard. 2000;14(18):47-52.

Adam S. Shock, systemic inflammatory response and multiorgan dysfunction. In: Brooker C, Nicol M, editors. Nursing adults. The practice of caring. Edinburgh: Mosby, 2003. Ch. 9

Greenstein B, Gould D. Trounce’s clinical pharmacology for nurses, 17th edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2004.

Jamieson EM, McCall JM, Whyte LA, editors. Clinical nursing practices, 4th edn, Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2002.

Morris D, Ward K. Perioperative nursing. In: Brooker C, Nicol M, editors. Nursing adults. The practice of caring. Edinburgh: Mosby, 2003.

Nicol M, Bavin C, Bedford-Turner S, Cronin P, Rawlings-Anderson K. Essential nursing skills, 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Mosby, 2004.

Peattie PI, Walker S. Understanding nursing care, 3rd edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1995.

Sheppard M, Wright M, editors. Principles and practice of high dependency nursing, 2nd edn, Edinburgh: Baillière Tindall, 2006.

Stott R. Pre-op visiting - revisited (1). British Journal of Theatre Nursing. 2002;12(8):306.

REFLECTIVE PRACTICE

REFLECTIVE PRACTICE CRITICAL THINKING

CRITICAL THINKING NURSING SKILLS

NURSING SKILLS