Chapter 20 Elimination – urine

Introduction

Continence and bladder (and bowel) care form one of the eight original Essence of Care best practice statements from the Department of Health (DH) (2001). The Essence of Care benchmarks arose from the commitment in Making a Difference (DH 1999), which is the national nursing, midwifery and health visiting strategy.

The Essence of Care aims to improve quality in care and has therefore been designed to share good practice amongst health trusts, identifying best practice and remedying poor practice, effectively improving the quality of care that people receive.

Central to this theme, or any that aims to improve care, is a sound understanding of the issues, in this instance related to continence and incontinence. Even though some nurses may not do ‘hands-on’ care they must understand the processes involved because they are accountable for delegated care (see Chs 6, 7). It is essential therefore to have a thorough grounding in the anatomy and physiology of the urinary system.

Two of the most commonly seen problems associated with urinary elimination are urinary tract infections and loss of continence. The importance of promoting continence cannot be overstated. The report Making a Difference (DH 1999) finds that although continence is considered one of the fundamental aspects of care, the provision of that care is below acceptable standards.

The urinary system is an integral component of homeostatic balance, ensuring that there is excretion of unwanted waste products, water balance and assisting with the control of blood pressure, to name a few examples. An understanding of the normal physiology of the urinary system will enable the nurse to care for the patient by anticipating potential problems and understanding the rationale for managing actual problems.

Elimination of urine crosses several traditional specialty boundaries, i.e. renal, urology, continence and gynaecology nursing, although an understanding of how this system works is essential for all nurses, whether children’s nurses, mental health or learning disabilities nurses, so that safe and appropriate nursing care can be offered.

The short answer and multiple choice questions have been designed to test your knowledge, and a Further reading section provided for those wishing to gain a greater insight into these common problems.

Overview – anatomy and physiology of the urinary system

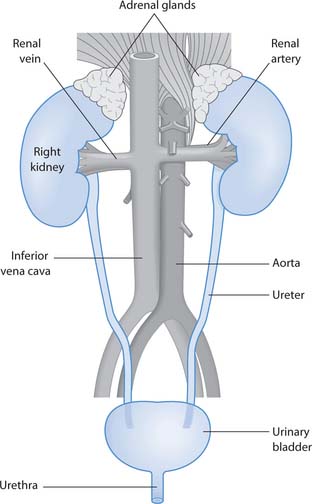

The urinary system comprises the kidneys (2), ureters (2), bladder and urethra (Fig. 20.1). Readers should consult their own anatomy and physiology books for further details.

The kidneys

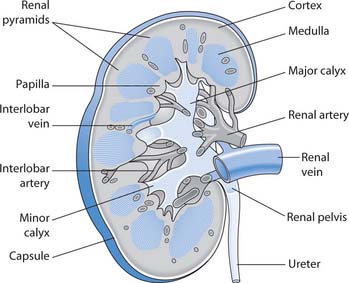

The kidneys are paired organs that lie against the back (dorsal) body wall behind the parietal peritoneum (retroperitoneal) in the superior lumbar region, i.e. they are either side of the spinal column at about the level of the lower ribs, but lying towards the back. When a kidney is cut longitudinally three distinct areas can be seen with the naked eye (Fig. 20.2):

Fig. 20.2 Longitudinal section through a kidney

(reproduced with permission from Brooker & Nicol 2003)

The kidneys are key organs with the functions that include:

In adults, the kidneys receive approximately 625 mL of blood per minute from branches of the renal artery. A high volume of blood supply to the kidneys is required to maintain glomerular filtration rates (GFR) (see below) and to supply oxygen to active cells.

Nephron

Each kidney is composed of approximately one million microscopic, functional units, the nephrons, and a system of collecting ducts that carry urine through the renal pyramids into the calyces and renal pelvis and hence to the ureter.

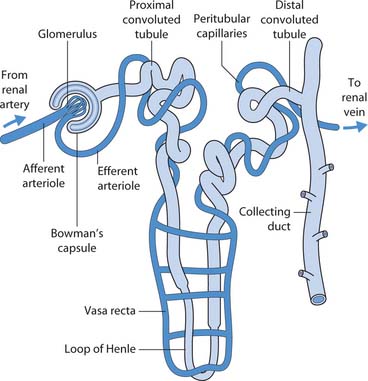

A nephron has a glomerulus (a knot of arterial capillaries) and a renal tubule that consists of a glomerular (Bowman’s) capsule enclosing the glomerulus, a proximal convoluted tubule (PCT), loop of Henle, distal convoluted tubule (DCT) and the accompanying blood vessels (Fig. 20.3).

Blood enters the glomerulus from the afferent arteriole, but this is dependent on blood pressure. Small holes (fenestrations) in the lining of the capillary allow small particles such as glucose to pass through into the renal tubule. However, larger molecules such as proteins cannot normally pass through the glomerular filtration barrier.

Blood leaves the glomerulus in the efferent arteriole, which forms a second capillary network around the renal tubule, the peritubular capillaries and more specialized capillaries called the vasa recta (see Fig. 20.3). The peritubular capillaries form larger and larger veins that carry blood to the renal vein.

The filtration membrane allows large quantities of fluid and small molecules such as sodium and glucose to leave the blood and enter the tubule. At this stage the fluid is called filtrate; it will become urine as it passes down the tubule. Substances needed by the body such as glucose are reabsorbed in the PCT and returned to the blood.

Control of blood flow into the glomerulus

The GFR is the volume of plasma filtered through the glomerulus in 1 minute; the adult GFR is about 120 mL/min. Although GFR changes with age, all age groups need to maintain GFR to excrete waste products and balance the amount of water in the body (Box 20.1).

Box 20.1 Glomerular filtration rate at the extremes of the lifespan

Newborn babies have a low GFR and are therefore vulnerable to fluid overload. Children reach adult GFRs between the first and second years of life. Older people usually have a decreased GFR, and also total body water, and are therefore at increased risk of having adverse drug reactions if a drug, e.g. the heart drug digoxin, accumulates in the body because it is not excreted quickly enough (see Ch. 19).

GFR can be controlled to ensure that a constant supply of blood is received at the correct pressure, ensuring that urine is constantly produced. This control is achieved by changing the diameter of the renal arteries and afferent and efferent arterioles by various processes that include:

The amount of urine output is therefore a guide for whether the kidneys are receiving blood at the correct volume and pressure. The minimum urine output, i.e. the smallest volume that will allow the body to excrete waste products, is 0.5 mL/kg/h in both children and adults, although there are exceptions to this rule.

Control of blood volume

The amount of fluid in the body is carefully controlled by many organ systems (see Ch. 19). Several substances help to balance the volume of fluid in the body, particularly antidiuretic hormone (ADH).

ADH, or vasopressin, is released from the brain (stored in the posterior pituitary gland) when blood fluid volumes fall, e.g. as may occur from blood loss. ADH increases the permeability of the renal tubule, increasing water reabsorption. When plasma ADH levels are low, a large volume of urine is excreted (diuresis), and the urine is dilute. When plasma levels are high, a small volume of urine is excreted (antidiuresis), and the urine is concentrated.

Alcohol inhibits the release of ADH and therefore should be avoided when dehydrated (see Ch. 19). Caffeine also acts as a diuretic, i.e. making people pass urine more frequently, by increasing the GFR and inhibiting sodium reabsorption.

Urine production in the nephron

There are three processes involved in the production of urine: filtration (see above), reabsorption and secretion. Table 20.1 (p. 572) outlines the specific functions of each segment of the nephron.

Table 20.1 Summary of the functions of the nephron and collecting ducts

| Part of nephron | Processes |

|---|---|

| Proximal convoluted tubule (PCT) | This is the site of most reabsorption – most of the fluid or filtrate that enters the PCT is reabsorbed (approximately 80% of the filtered load) |

| Some water, electrolytes, bicarbonate, glucose, etc. are essential to the body and are reabsorbed and returned to the circulation; the waste products (e.g. urea and creatinine) entering the filtrate are not reabsorbed because they need to be eliminated from the body | |

| By the time the filtrate reaches the end of the PCT it has been reduced to 20% of the volume that was filtered. It contains water, electrolytes, urea and other substances that are no longer required by the body | |

| Loop of Henle | Water can leave the descending limb of the loop of Henle via osmosis but sodium is trapped |

| In the ascending limb of the loop of Henle water is now trapped, but sodium can be reabsorbed | |

| The loop of Henle can selectively reabsorb water and sodium so that water balance is maintained | |

| Distal convoluted tubule (DCT) | Renin, aldosterone and ADH all act at the DCT (see p. 571) |

| Sodium and chloride can be reabsorbed here | |

| There is also reabsorption and/or secretion of potassium and hydrogen into the filtrate | |

| Secretion is important in acid–base balance | |

| Water is only reabsorbed in the presence of ADH | |

| Collecting ducts | It is only in exceptional circumstances that water and electrolytes can be reabsorbed |

| In the absence of ADH, dilute urine enters the collecting tubules | |

| When ADH is secreted, the collecting duct becomes more permeable to water and water is removed and the urine becomes more concentrated | |

| The fluid that enters the calyces (see Fig. 20.2, p. 570) is urine, which then drains into the renal pelvis and the ureters |

Lower urinary tract

The lower urinary tract comprises two ureters, the urinary bladder and urethra (see Fig. 20.1).

Ureters

The ureters are hollow tubes that convey urine from the renal pelvis to the bladder. They are approximately 30 cm in length and implant into the posterior bladder at the ureteric orifices. Urine moves down the ureters by peristalsis, rhythmic contraction of the smooth muscle layer in the wall of the ureters.

Bladder

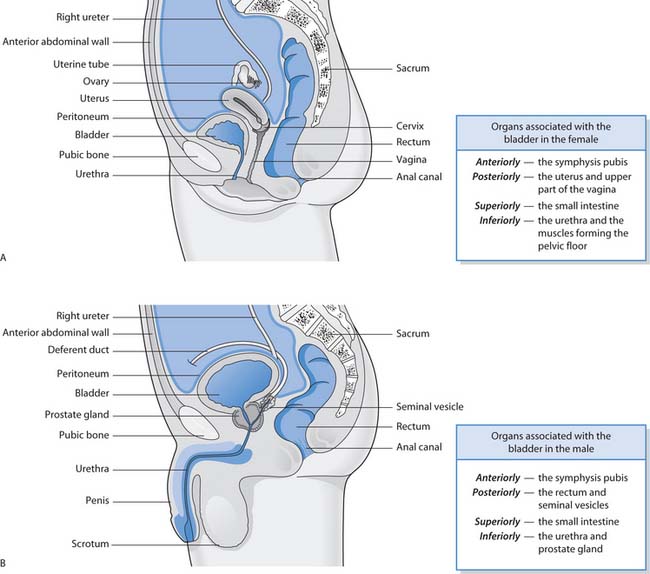

The bladder is a temporary reservoir for urine. It is a muscular sac lined with transitional epithelial cells (urothelium). When the bladder is empty the lining is arranged in folds called rugae. These folds disappear when urine fills the bladder. The smooth muscle layer is called the detrusor and is an exceptionally strong muscle that contracts to empty the bladder. The three openings in the bladder wall – two ureteric orifices and the urethra – form a triangle called the trigone. The organs associated with the bladder in women and men are illustrated in Figure 20.4.

Fig. 20.4 Organs associated with the bladder: A. The female. B. The male

(reproduced with permission from Waugh & Grant 2001)

The bladder is able to distend but when the adult bladder contains around 300–400 mL of urine the urge to pass urine occurs. The volume is much less in children and depends on the child’s age, but the bladder wall becomes stretched when approximately 50–200 mL of urine is in the bladder (Kozier et al 2000), although this will be dependent on the infant’s feeding regimen, with urine volumes increasing as the child’s urinary system matures.

The main defences against infection in the urinary system are the flow of urine, the acidity of urine and, in males, the length of the urethra. Urine is normally acidic (see p. 578) which inhibits bacterial growth.

Urethra

The urethra carries urine from the bladder to the outside. In males, the urethra is around 20–25 cm in length, has several curves and passes through the prostate gland. In addition to carrying urine the male urethra also carries semen. The female urethra is approximately 5–10 cm in length, is straight and not involved in reproduction.

The urethra passes through the muscular pelvic floor where internal and external urethral sphincters are located. The external sphincter is under voluntary control or, more accurately, the external control develops during childhood. Normally the sphincters keep the urethra closed so that urine does not leak from the bladder.

Urinary elimination

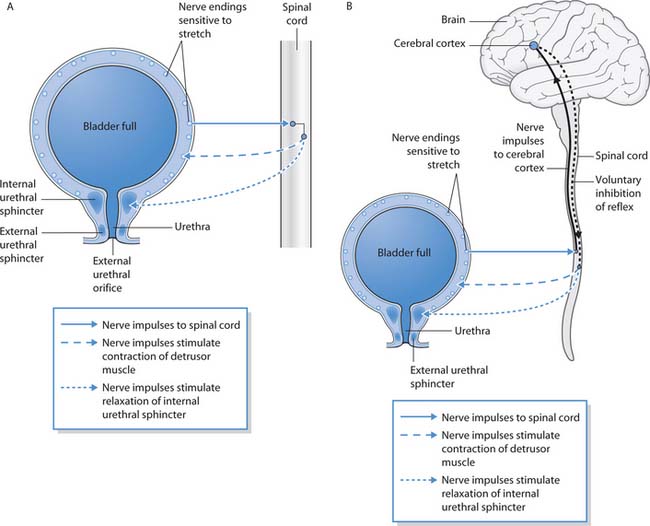

Micturition, voiding and urination all refer to the process of passing urine. It is an extremely complex process that involves nerve impulses, coordinated muscle contraction and relaxation of the internal and external urethral sphincters. This process develops over the first few years of life, which explains why babies are not continent. The nerve supply from the bladder to the spinal cord is incomplete until the age of around 2 years when the toddler gradually learns that the sensation in the bladder means that they need to pass urine.

When the infant’s bladder fills with urine the bladder wall is stretched and nerve impulses pass to the spinal cord. This initiates a spinal reflex that causes detrusor muscle contraction, internal sphincter relaxation and the baby voids urine (Fig. 20.5 A, p. 574).

Fig. 20.5 Control of micturition: A. Simple reflex control when conscious effort cannot override the spinal reflex. B. Control of micturition when conscious override is possible

(reproduced with permission from Waugh & Grant 2001)

When development is complete and continence is achieved, the urethral sphincters and the bladder are controlled by a more complex nervous system (Fig. 20.5 B, p. 574). As before, the bladder fills with urine and the bladder walls are stretched, resulting in a nerve impulse being sent to the spinal cord. Now, however, the nerve impulse is directed upwards to the cerebral cortex of the brain, where the impulse is interpreted as the desire to pass urine. This usually results in a behavioural response, i.e. going into the lavatory or asking the nurse for a bedpan. Conscious inhibition of reflex bladder contraction and sphincter relaxation is possible for a short time when it is not convenient to pass urine such as driving on a motorway until the service station is reached.

The cerebral cortex sends another nerve impulse to the spinal cord, and then on to the bladder and internal urethral sphincter. As the detrusor muscle contracts there is reflex relaxation of the internal sphincter and voluntary relaxation of the external sphincter, allowing urine to pass through the urethra. Once the bladder is empty the nerve impulses stop, the detrusor muscle stops contracting and the sphincters close.

Micturition can be aided by increasing pelvic pressure through contracting the abdominal muscles and lowering the diaphragm (Valsalva manoeuvre).

Factors affecting micturition

There are multiple factors affecting micturition (Box 20.2, p. 574).

Micturition is usually under a degree of conscious control. Usually an adult or older child passes urine alone, at a time determined by them and in surroundings that are usually comfortable and known to them. Hospitalization therefore can be a contributory factor affecting mictur-ition. People can become disorientated or positioned too far from the lavatory, which can cause loss of continence. Furthermore, a person’s normal urinary habits can be altered by anxiety, following surgery or illness, through constipation or dehydration, and these factors should be considered when caring for people irrespective of age. Obesity is associated with some types of incontinence (see p. 586) in women but not in men.

Many drugs can also affect the person’s ability to urinate normally, from diuretics (e.g. furosemide) which increase urinary volume and frequency, to analgesics that can cause confusion and disorientation. Caffeine, found in tea, coffee and cola-type drinks, as well as performance-enhancing drinks, can have an excitatory effect on the bladder muscle, causing urgency and frequency, as well as being a diuretic. Alcohol acts as a diuretic by affecting ADH release, irrespective of overall hydration. Box 20.3 provides an opportunity to consider how micturition may be affected.

Changes to micturition

Think about a situation in which your own micturition was affected, such as being anxious about a new placement, or having a full bladder and being unable to find a public lavatory, or perhaps you needed to pass urine where another person could hear or see you.

Student activities

Common urinary disorders

Urinary tract infection (UTI) and loss of continence (incontinence) are very common. These and other conditions that affect the normal urinary elimination are outlined in Table 20.2. Further detail about UTIs is provided in Box 20.4 (p. 576). More information is provided in Cotton et al (2003) and Fanning (2003). Some patient groups also provide useful information and some of their websites are included at the end of this chapter.

Table 20.2 Common urinary disorders

| Disorder | Description |

|---|---|

| Benign prostatic enlargement (BPE) | An enlarged prostate gland caused by increased cell size or growth of new cells occurring mainly in older men |

| Leads to urinary problems such as poor stream, dribbling, frequency and retention (see p. 576) | |

| Cancer – kidney, bladder, prostate | Cancer may affect the kidney, ureter, bladder and prostate gland |

| A cancer affecting the kidney, known as a nephroblastoma (Wilms’ tumour), is common during childhood | |

| Bladder cancer can cause painless haematuria (blood in the urine) | |

| Cancer of the prostate gland is a common male cancer, which can cause symptoms similar to those of BPE | |

| Diabetic nephropathy (kidney disease) | Progressive kidney disease associated with diabetes |

| Caused by damage to the renal blood vessels, loss of glomeruli and renal failure | |

| Glomerulonephritis | Inflammation of the glomerulus (of the nephron), of which there are many different types |

| Incontinence of urine | An inability to control the voiding of urine |

| The main types are outlined on page 586 | |

| Reflux nephropathy (chronic pyelonephritis) | Kidney damage caused by the backflow of infected urine from the bladder up the ureters (vesicoureteric reflux – VUR) (see Box 20.4, p. 576) |

| Renal (kidney) failure | Renal failure can be acute or chronic: |

| • Acute renal failure (ARF) occurs when previously healthy kidneys suddenly fail because of reduced blood supply, e.g. severe haemorrhage; it is potentially reversible | |

| • Chronic renal failure (CRF) occurs when irreversible and progressive damage, such as from diabetic nephropathy, leads to end stage renal disease (ESRD) | |

| Renal stones (calculi) | Stones can form in the kidney |

| They may move down the ureters to cause intense pain (renal colic), obstruct the flow of urine from the kidney, predispose to infection and may cause renal damage | |

| Urinary tract infection (UTI) | Infection affecting the urinary tract is common across the lifespan (see Box 20.4, p. 576) |

Box 20.4 Urinary tract infection

UTIs are more common in females than in males, except in infants under 1 year due to periurethral colonization, breastfeeding or an immature immune system (Dairiki Shortliffe 2002). The site of the infection determines the term used to describe the infection:

Urinary tract infections are caused by bacterial invasion, e.g. Escherichia coli. Normally the urine does not contain bacteria; the presence of bacteria in the urine is termed bacteriuria. Bacteriuria can be symptomatic, e.g. painful voiding or dysuria, or asymptomatic. Pyuria is the presence of white blood cells (WBCs) in the urine, indicating inflammation of the bladder lining. Bacteriuria without pyuria suggests bacterial colonization, not infection (see Ch. 15).

In children, UTIs tend to be classified into initial infections and recurrent infections. Sometimes the cause of infection can be linked to a congenital abnormality that results in vesicoureteric reflux (VUR) or backflow of urine from the bladder into the ureters or kidney. It is essential to identify the presence of UTI in children so it can be investigated and the cause treated to prevent renal damage in later life. UTI in young children can be particularly difficult to diagnose because of several non-specific signs such as poor feeding, fever, vomiting or failure to thrive, as well as the development of language and children’s concepts of health and ill health. This may also be the case in some people with a learning disability.

UTIs in older people are common. The symptoms can range from asymptomatic bacteriuria to life-threatening sepsis. The majority of older people with bacteriuria remain asymptomatic, although symptoms such as lethargy, confusion, anorexia and incontinence may be caused by bacteriuria.

Assessment and observation of urine and urinary elimination

Before taking a urine sample, it is essential to ask the person about any problems with micturition and urinary symptoms. Box 20.5 (p. 576) provides an overview of problems with micturition and some urinary symptoms. The key features are the type of symptoms, duration of the problem, what makes it better or worse, and any other circumstances that could exacerbate the problem, e.g. the lavatory is upstairs so the person cannot get to it quickly enough due to arthritis. Bowel habit is also important to assess, since constipation can cause pressure on the urethra/bladder, thereby resulting in urinary symptoms (see Ch. 21).

Box 20.5 Problems with micturition and urinary symptoms

As well as the focused assessment, the nurse should note how mobile and dextrous the person is. Part of the assessment is gaining a picture of the person and their abilities; this will help guide nursing management and what continence products/support they will need.

Measuring urine output and observing voiding patterns

This can involve the use of a fluid balance chart, weighing nappies, weighing patients daily and completing frequency–volume charts. In addition, assessment of the skin and mucous membranes and blood pressure monitoring will also enable assessment of hydration (see Chs 17, 19).

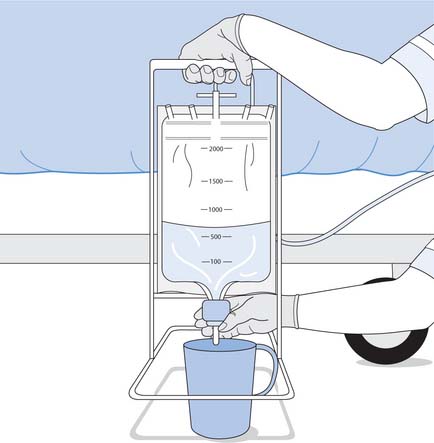

Fluid balance chart (see Ch. 19)

Urinary output must be recorded on a 24-hour input and output chart if there are concerns about the elimination of urine or renal function. The minimum amount of urine needed to excrete waste from the body was discussed on page 571, i.e. 0.5 mL/kg/h in both children and adults.

Therefore, an infant weighing 5 kg must produce 2.5 mL/h (60 mL in 24 hours) whereas an adult weighing 55 kg must produce 27.5 mL/h (660 mL in 24 hours). Obviously these are minimum amounts and people produce much larger volumes of urine under everyday conditions, approximately 1 mL/kg/h but up to 2 mL/kg/h (Box 20.6). The volume of urine produced depends on many factors that include fluid intake, fluid loss and renal function, but a healthy adult should aim to pass more than 1000 mL daily, with an ‘ideal’ urinary volume of 2000 mL. This ensures that the kidney and lower urinary tract are ‘flushed’ regularly, thus reducing the risk of UTI.

Variations in urinary volume

Measure your own urine output for 24 hours and calculate how much this is in terms of mL/kg/h.

Weighing nappies

Accurate measurement of urine volume in babies and young children is more difficult but can be achieved by weighing wet nappies. The known dry weight of the nappy is subtracted from the weight of the nappy after the baby or child has passed urine. The difference in weight in grams approximately corresponds to millilitres of urine voided.

Frequency–volume charts

Frequency–volume charts can be completed by the person or carer at home and brought to the clinic to be assessed. They are particularly helpful in gaining an insight into voiding patterns. The volume of fluid taken in, the urine output, and occasions when the person had an episode of incontinence should all be recorded. Although frequency–volume charts are widely advocated for assessing urinary incontinence (see p. 585), they can focus the person’s attention on their urinary symptoms, leading to inaccuracies and additional distress. To minimize this, the charts should be completed for at least 5 days, and when the person is seen again, time should be taken to discuss how they feel about their condition.

Observation of urine and urinalysis

Observation of urine and routine urinalysis by the nurse are both important in the routine screening for abnormalities and possible disease. Any abnormal findings should prompt further urinary analysis by the laboratory, e.g. by sending a midstream specimen of urine (MSU) (see p. 581).

The urine used for routine testing (urinalysis) should be a fresh ‘midstream’ sample. This can pose problems for many people who are unable to stop and start their urine and ‘catch’ the middle part of the flow. People can be assisted in catching the stream by use of a clean funnel. A ‘clean catch’ sample may the best alternative in babies, small children, some adults with dementia and some people with learning disabilities. Urine samples should not be the first void of the day unless the urine is being tested for renal tuberculosis (TB). Before performing the urinalysis the nurse should always observe the sample for colour, clarity and odour (Table 20.3, pp. 578–579) as these physical characteristics can give valuable clues about potential abnormalities.

Table 20.3 Normal characteristics of urine and the significance of abnormalities*

| Physical and chemical characteristics | Normal findings – observation and urinalysis | Possible significance of abnormal findings |

|---|---|---|

| Colour | Pale straw colour to deep amber depending on the concentration | Dark urine may indicate dehydration |

| Blood in the urine (haematuria) can be bright red or can give the urine a smoky appearance | ||

| Bilirubin turns the urine a brown/green colour or the urine may even be frothy | ||

| Certain foods or drugs may also influence colour: eating red beet (beetroot) can produce pinkish’ urine; the drug rifampicin can cause orange/red urine | ||

| Clarity (need urine in a clear container) | Usually clear with possible turbidity caused by mucus | Cloudiness or debris can indicate the presence of pus, protein or white cells and would need further investigation |

| Odour | Freshly voided urine may have a slight aromatic odour but does not usually smell, whereas stale urine can smell of ammonia | A ‘.shy’ smell would indicate an infection and a ‘pear- drop’ smell indicates ketones in the urine |

| Certain foods such as asparagus produce a characteristic odour | ||

| Specific gravity (SG) – the density of a substance as compared with an equal quantity of distilled water, the latter being represented by 1.000 | It is impossible to urinate pure water because the urinary system is ‘designed’ to remove waste products from the body | A high SG is found if the urine is con centrated; this may indicate that the person is dehydrated (see Ch. 19) |

| High levels of glucose or other abnormal substances can also result in a high SG | ||

| The normal SG range of urine is 1.001–1.035, depending on the solids contained in the urine, i.e. a high SG indicates a high level of solids | ||

| Conversely, dilute urine will have a low SG, which occurs normally when the fluid intake is increased, but can occur during a stage of renal failure | ||

| Small children tend to have a relatively fixed SG of 1.008 because their renal system is relatively immature and the kidneys are unable to concentrated urine (Kozier et al 2000) | When assessing SG, the ambient or environmental temperature should be considered; individuals can very quickly become dehydrated in hot conditions | |

| pH | The pH of urine is normally acidic, but within the pH range of 5–8 urine is considered normal | Very acidic urine may suggest urinary stone formation, whereas alkaline urine suggests an infection with certain types of bacteria such as Proteus mirabilis |

| Urinary pH is influenced by dietary intake – high meat intake produces acid urine whereas a vegetarian diet produces alkaline urine | ||

| Protein | Negative | Normally protein (albumin) molecules are too large to pass through the glomerular filtration barrier, therefore the presence of protein in the urine is abnormal and is called proteinuria or albuminuria |

| It can indicate glomerular/renal damage, although a urinary tract infection can cause proteinuria | ||

| Transient proteinuria can occur in children during febrile illnesses or exercise, and would not normally require further investigation, although persistent pro- teinuria would necessitate a 24-hour urine collection (see p. 581) | ||

| Blood | Negative | Blood in the urine (haematuria) is abnormal |

| Haematuria usually indicates problems somewhere in the urinary tract, e.g. cancers, renal damage, stones, or it can be due to causes outside the urinary tract, e.g. as a side-effect of anticoagulant drugs or a blood clotting problem | ||

| Haematuria can be frank’, i.e. the urine clearly contains blood, smoky or microscopic | ||

| It is important to eliminate the possibility that haematuria is due to contamination with menstrual blood | ||

| In young baby boys, haematuria may be due to crystals forming in the urethra. The haematuria should only be slight and resolve within the first few weeks. Any concerns should be referred to the appropriate health professional | ||

| Glucose | Negative | Glucose is not normally present in the urine because in health it is reabsorbed in the nephron (see p. 572) |

| Glucose in the urine is termed glycosuria | ||

| Glycosuria can indicate diabetes mellitus but also can occur during pregnancy, in physiological stress and in people taking corticosteroids | ||

| Glycosuria can be accompanied by a high urine output, because the glucose molecules draw water with it, resulting in high volume urine output and subsequent dehydration | ||

| Ketones | Negative | The presence of ketones in the urine is called ketonuria |

| Ketones are acidic chemicals that are formed during the abnormal breakdown of fat in certain situations that include prolonged vomiting, fasting, starvation and poorly controlled diabetes mellitus | ||

| Urobilinogen | Small amounts of urobilinogen are normally found in the urine | Elevated levels may indicate liver damage or abnormal breakdown of red blood cells (haemolysis) |

| Urine that contains high levels turns dark when left to stand | ||

| A reduction or absence occurs in biliary obstruction, i.e. when bile does not reach the intestine | ||

| Bilirubin | Negative | The presence of bilirubin can indicate liver disease or biliary obstruction |

| White blood cells | None | The presence of white cells is associated with UTI, but may indicate more severe renal problems |

| Nitrites | Negative | A positive test for nitrite is associated with bacteriuria (see p. 576) |

Note: All abnormal findings must be reported.

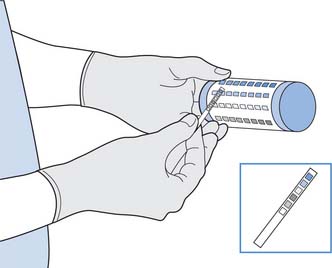

Urinalysis using a reagent test strip is a quick and simple test for assessment of renal function, hydration and nutritional state (Fig. 20.6, p. 579). Urine reagent sticks usually test for the following:

Some reagent sticks also include a test for nitrites and leucocytes (white blood cells), the presence of which might indicate bacteriuria and UTI, respectively. Since the kidneys excrete waste, the presence of substances not normally excreted, e.g. protein, glucose, can help with diagnosis of renal disease, diabetes mellitus, infection, etc. (see Table 20.3, pp. 578–579).

This test is relatively simple and accurate to use, although nurses should be familiar with the manufacturer’s recommendations for use (Box 20.7, p. 580). Care should be exercised to avoid contaminating samples, e.g. from menstrual blood that could give rise to inaccurate results.

Testing urine

Preparation

Explain what you are going to do and seek verbal consent; maintain respect and dignity at all times. The nurse washes and dries hands and puts on non-sterile gloves, plus plastic apron if assisting the person to collect the sample (see below).

Procedure

Note: Some hospital units or GP centres have automatic urine testing machines. It is essential to gain training in how to use these machines to ensure that accurate results are obtained.

[Further reading: Cook R 1996 Urinalysis: ensuring accurate urine testing. Nursing Standard 10(46):49–54]

Collection of urine samples for the laboratory

When a urine sample is required, the person or parents/carers of children should be advised why that sample is necessary, e.g. to confirm an infection etc. The accuracy of any test and subsequent diagnosis of urinary tract abnormality can be influenced by many factors, e.g. the amount of bacterial contamination when the urine is collected (see Ch. 15).

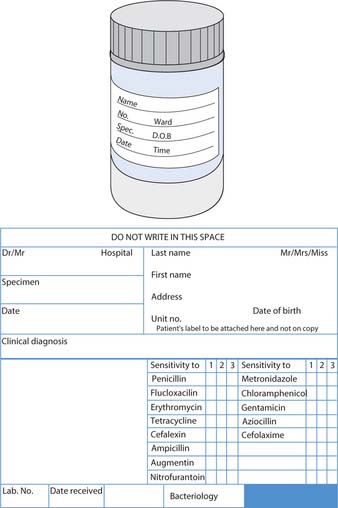

The options for urine collection from babies and young children are outlined in Box 20.8 (p. 580). In adults, most samples are voided midstream urine (MSU) (Box 20.9, p. 581) or a catheter specimen of urine (CSU) (see Box 20.28, p. 594). In order to identify infection, urine is sent to the laboratory for microscopy, culture and sensitivity (MC&S). The scientist will confirm the presence of microorganisms on microscopy, these will be grown on an appropriate culture medium and sensitivity tests will determine the most effective antibiotic to treat the infection. Urine may also be collected for cytology, looking for abnormal cells, such as cancer cells from the urinary system, that are passed in the urine. Urine samples, often collected over 24 hours, may be analysed for electrolyte levels, protein and various hormones and other chemicals (Box 20.10).

Box 20.8 Collecting urine samples from babies and young children

Urinary specimens are the main method used to diagnose UTI, but it is particularly difficult to obtain an uncontaminated sample from children, and the reliability of the test is related to the quality of the urine sample collected. The four ways in which to obtain a urine sample in children are:

The plastic bag specimen is least favoured because of the high degree of contamination of the sample from the perineum and rectum. For non-emergency urinary specimens the baby or child can be sat over a sterile receptacle and the urine collected and tested. This is referred to as a ‘clean catch’. The midstream urine sample is the most reliable but not always possible in young children. Girls must be encouraged to part the labia and in older boys the foreskin should be retracted to prevent contamination.

Suprapubic bladder aspiration is only performed when the sample is needed urgently in children less than 2 years of age. It is an advanced role undertaken by specially trained nurses who have demonstrated competence in this technique.

[Further reading: Huband S, Trigg E 2000 Practices in children’s nursing. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh, pp. 263–264, 307–308]

Collecting a midstream specimen of urine

Preparation

Explain what you are going to do and seek verbal consent; maintain respect and dignity at all times. The nurse washes and dries hands and puts on non-sterile gloves, plus plastic apron if assisting the person to collect the sample.

Procedure

Collecting a catheter specimen of urine

Preparation

Explain what you are going to do and seek verbal consent; maintain respect and dignity at all times. The nurse washes and dries hands, then puts on non-sterile gloves and plastic apron.

Procedure

24-hour urine collection

Preparation

Procedure

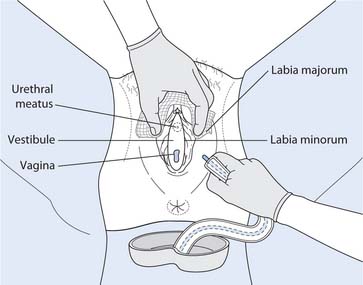

Voided urine specimens are the most acceptable and simplest form of collection for people. A midstream sample is used because it does not contain any debris that may be in the urethra, thus preventing a false result. It is essential for the external urethral meatus to be cleaned before collection of the sample. This helps to reduce the amount of contaminants in the sample.

Common urinary investigations

There are many different investigations used to identify disorders affecting the urinary tract and elimination (Box 20.11, p. 582).

Box 20.11 Common urinary investigations

The following investigations may be used to diagnose or evaluate treatment for disorders of the urinary tract and elimination:

The simple explanation of some these investigations as provided on the BBC website (BBC 2004) will help you provide patient information (Box 20.12); more detailed nursing explanation can be found in Further reading, Cotton et al (2003), Fanning (2003) and Wells (2003).

Intravenous urogram

Brian is 22 years old and has a mild learning disability. He lives at home with his parents and his younger sister. Brian has had several UTIs and is to have an intravenous urogram (IVU) in order to identify any abnormalities of his urinary tract.

Nursing interventions – micturition

Assisting people with urinary elimination starts with ensuring that adequate hydration has been provided (see Ch. 19). For many people their fluid requirements are higher when hospitalized than at home, e.g. people may be sweating, vomiting, have diarrhoea, blood loss, etc., all of which lead to fluid loss from the body.

People may also be weakened by their condition or treatment and may well require assistance in meeting their elimination needs. Many people will feel more comfortable using the lavatory on the ward rather than a urinal, commode or bedpan, and should be escorted or assisted to the lavatory by the nursing staff, to assess their mobility and maintain safety (see Chs 13, 18). For those unable to use the lavatory, a urinal, bedpan, potty or commode will need to be provided. This should be provided quickly and efficiently to limit any embarrassment that the person may have. The nurse should ensure privacy and maintain the person’s dignity at all times. The nurse must consider cultural needs, e.g. Hindus and Muslims require that nurses of the same sex meet their intimate care needs (see Ch. 16).

Use of urinal, bedpan and commode

Passing urine is usually a private experience and therefore asking people to pass urine in an outpatient department or ward can put them under considerable pressure, especially when they have a longstanding continence problem. The person should be assured that there would be a bedpan/urinal/commode or a lavatory available for them, that they will not be interrupted, and that the nurse will assist them as much as they want, provided that their safety can be maintained.

If the person is unable to walk to or be taken to the lavatory, a commode/bedpan (see Ch. 21) or urinal will be required. Respect and dignity need to be maintained by ensuring the curtains are completely closed round the bed space and the person allowed time to pass urine without interruption. It is also important to ensure that other members of staff and visitors are aware that the person requires privacy.

For males, using a urinal is relatively simple, provided they are able to sit up. Some men find it difficult to pass urine unless they are standing. It may be necessary to help the person position the penis and hold the urinal. Once completed, the urinal should be covered with a paper towel and removed. The person should then be provided with handwashing facilities. Some cultures, e.g. Muslims, wash their genitalia using running water after passing urine or faeces. A jug of water for washing is provided if the person is confined to bed.

The use of a slipper bedpan (Fig. 20.8, p. 583) for womenis easier and more comfortable to use, since it can be inserted from the side. If the woman is immobile, assistance with mobilizing will require additional staff and handling aids (see Chs 13, 18).

Tissues/lavatory roll is provided but should not be placed in the bedpan if the person’s fluid intake and output is being recorded because this will give an inaccurate result. Used tissue should be placed in a separate receptacle (disposable or a specific bowl that can be sterilized before use); the used tissue is disposed of by flushing it down the sluice. The use of an incontinence pad will catch any urine that accidentally spills from the bedpan, but should on no account be left under the person once they have been assisted off the bedpan because ‘inco’ pads can contribute to the development of pressure ulcers (see Ch. 25) and are uncomfortable to sit on.

Again, the person should be allowed privacy and time to pass urine. The person is provided with handwashing facilities and the necessary assistance to clean and dry the perianal area to remove urine, which can contribute to the development of pressure ulcers (see Ch. 25).

If the person is able to use a commode, this can often assist with passing urine. For most people, voiding when lying flat is extremely difficult (Box 20.13, p. 583). Using the commode can help the person by returning a degree of ‘normality’ to passing urine. Before giving the commode to the person, it must be thoroughly cleaned with soap and warm water and carefully dried (see Ch. 15). Attention should be paid to safety, ensuring the bed space is free from obstruction. The wheel brakes on the commode should be in working order and applied to maintain the person’s safety. Lavatory tissue must be provided in a separate receptacle for the person to use. In all instances the nurse call bell must be left within easy reach of the person. If a fluid balance chart is being kept, do not assess the volume of urine at the bedside, but make a note of the volume in the sluice room before discarding. The nurse must dispose of gloves and wash their hands before recording the voided volume on the person’s chart.

Position for passing urine

Think about a person you have helped to care for who had difficulty passing urine because of their position or lack of mobility.

Readers are directed to Nicol et al (2004) for comprehensive information about helping people who require bedpans, urinals or commodes for urinary elimination.

Promoting continence

Incontinence is not uncommon, particularly in women. Although the actual number of women with incontinence is unknown, approximately 6 million women in the UK are estimated to be affected annually by some form of incontinence (The Continence Foundation 2004). It is often preventable, and can be improved in many cases. However, maintaining continence is always the preferred option and nursing care should be individualized to meet the person’s needs, in accordance with the Essence of Care benchmarking statements (DH 2001). Loss of continence affects all age groups and includes school-aged children, new ‘mums’, postmenopausal women, older men with prostate problems, etc.

When assessing the person using a model of nursing, elimination must be included. As discussed above, there are many factors that can affect micturition, but nurses themselves cause some of these. People should feel confident that their request for a commode, urinal or bedpan will be promptly met, or that assistance in getting to the lavatory will be swiftly provided so that their anxiety about hospitalization is not worsened.

Consideration should also be given to the proximity of the lavatory to the person’s bed space, i.e. a person who has difficulty in mobilizing should not be situated at the end of a ward. Accessibility of the lavatory is also important at home. A commode may be used at home if the person is unable to climb stairs to the lavatory. Adaptations to the lavatory, such as a raised seat and handrails, can increase independence and help to maintain continence (see Fig. 21.5).

Making appropriate choices or small changes to clothing can help people to remain continent. For example, a woman with poor manual dexterity may be unable to remove trousers, tights and pants in time but a wrap-around skirt allows her to use the lavatory (Fig. 20.9). The use of Velcro fastenings instead of buttons and zips can also be helpful.

Furthermore, the nurse should consider the effects of medication on elimination. Many drugs can affect the ability to urinate normally, from diuretics (‘water tablets’) that increase urinary volume and frequency, to analgesics and sedatives that can cause confusion and disorientation (Box 20.14).

Diuretics – maintaining continence

Arrange to talk to a person who takes a loop diuretic such as furosemide (these affect processes in the loop of Henle). This might be a client, friend or relative.

Box 20.15 (p. 584) outlines some factors that affect the person’s ability to maintain continence. Many of these factors can cause urinary incontinence (involuntary loss of urine).

Box 20.15 Factors affecting ability to maintain continence

Normal voiding habits

Essentially there is no ‘normal’ pattern of voiding; however, there are clearly abnormal patterns. Between the ages of 18 months and 3 years, children become aware of the sensations to pass urine as their nervous system develops (see below). It would still be within the range of ‘normal’ for children to wet the bed until the age of 5 years. Daytime wetting decreases as the child ages and the majority of children over 5 should be continent during the daytime. Only 1% of girls and 0.8% of boys wet during the day (Cook 1999).

As the child ages, voiding volumes increase, estimated to be:

age in years × 30 + 30 = volume in mL

until they reach the adult range of around 400 mL every 4–6 hours or so (Cook 1999). The normal voided volume for babies is approximately 60 mL per day, increasing to 500 mL in the first year, and rising steadily to the adult norm of approximately 1500 mL every 24 hours (Kozier et al 2000).

The main feature, however, is that the amount voided is dependent on the amount of fluid consumed and whether the kidneys are functioning properly. People with voiding problems often reduce their fluid intake, which almost universally worsens the situation by increasing the risk of UTI and reducing the benefits of flushing the urinary system.

Achieving urinary continence during childhood

Continence is achieved by socialization of the child and maturation of the nervous system (which usually occurs between the age of 2 and 3 years) (Rogers 2002).

For a child to develop continence, they must:

Introducing the child to the potty at a time when a routine is often already established, e.g. before a bath at bedtime, can facilitate this learning. The child is encouraged to sit on the potty. It can be helpful to bring a book to read with the child, so that their concentration can be maintained. Once the child has passed urine (or faeces) it is essential to reward them in the form of praise. This helps the child to understand what the potty is for, and that passing urine/faeces in the potty is ‘good’. The ‘right’ time to start potty training depends on each child, but once the child notices that they are wet or soiled is an indication of maturity and therefore a good time to start. Children can control their bowels before their bladders. It may take a long time, many months, before the child notices the desire to void, but a toileting routine will help in establishing some patterns that will promote continence (Box 20.16).

Potty training

Boys need to learn to stand to pass urine, that it is acceptable to pass urine in front of other males, but not females, and that the whole process is usually conducted behind closed doors. This will take some time; the essential element is not to make this too stressful or put too much pressure on the child since they will not cope with the extra demand. In addition, both boys and girls need to be able to undo buttons or zips, pull down pants or tights, wipe themselves afterwards and flush the lavatory (Rogers 2002).

‘Accidents’ should be anticipated until the age of 5 years or so. These include episodes when the child is too engrossed in playing, for example, to pay attention to the signals from the bladder, or not sure where the lavatory is located, introduction of a new baby or just starting school.

Enuresis is leakage of urine occurring on regular basis (at least once per week). It is important to check physical causes, such as proximity to a lavatory, as well as physical disabilities that may interfere with manual dexterity or movement.

Nocturnal enuresis is the passing of urine involuntarily at nighttime. Again, for a diagnosis, the child will be older than 5 years and not have any congenital abnormality that may affect the nervous or urinary system, e.g. spina bifida (Box 20.17).

Spina bifida

Spina bifida is a neural tube defect (NTD). During the first few weeks of the pregnancy, folic acid helps to ‘build’ the vertebrae of the developing fetus. Women who have diets low in folic acid, or whose partners may have spina bifida, need additional folic acid to prevent this condition. The child can be born with a hole or opening in their back, with exposure of the spinal cord where the spinal vertebrae have failed to close.

The defect is surgically closed, but it is only after closure, and as the child develops, that the extent of damage to the spinal cord is noted. Since the nerves that control the bladder (and bowel) connect with the spinal cord, there can be persistent incontinence.

Student activities

[Resources: Association for Spina Bifida and Hydrocephalus – www.asbah.org Available July 2006]

Enuresis is often subdivided into types, which include diurnal enuresis, true or ‘giggle’ incontinence and functional incontinence (Box 20.18).

The aetiology of enuresis is complex, but includes genetics, bladder structure and function, congenital abnormalities (e.g. spina bifida), UTI and sleep patterns (Lukeman 2003). There is also thought to be a behavioural/emotional component to enuresis. Separation from the family or tension in the family, such as a new sibling, may provoke or maintain enuresis; furthermore, poor self-esteem in the child will exacerbate bedwetting.

Types

Management

The management of enuresis is aimed at keeping the child dry throughout the day and night, and is often achieved through change in behaviours (Box 20.19, p. 586).

Devices can be used that sense when urine has leaked which then sound an alarm that wakes the child. On waking, the urinary sphincters tend to close, which allows the child to empty their bladder in the lavatory or potty. It can take time for the child to get used to these devices (Cook 1999).

Nurses should support parents or carers by providing information about treatment and support groups (see ‘Useful websites’, p. 597).

Behavioural programme for enuresis

As with any behavioural programme, it is essential to establish a baseline from which to compare change. A chart could be used to record episodes of bedwetting and rewards given for goals achieved, e.g. using a potty, or keeping dry overnight.

The child is taught how to sit on the lavatory, with feet flat on the floor to promote a relaxed position that limits abdominal straining. This allows the detrusor muscle to work properly. The child should be encouraged to pass their urine in one go, not to stop and start the flow. Occasionally the child cannot completely empty their bladder. They should be encouraged to pass urine, then wait for a few minutes, and then try again. Fluids are encouraged because reducing fluid intake can lead to infections and dehydration.

Finally it is essential to reward the child, e.g. by making a chart and affixing self-adhesive stars to it, to show how the child is progressing. In addition, positive rewarding, such as simple praise, can also help the child.

[Further reading: Rogers J 2002 Managing daytime and nighttime enuresis. Nursing Standard 16(32):45–52]

Pelvic floor awareness and exercise

Pelvic floor exercises or Kegel exercises are designed to ‘retrain’ the pelvic floor muscles after injury/childbirth (Dorey 2003) or after trauma to the bladder after prostate surgery. They are useful in men and women with bladder/continence problems. The exercises involve contracting the pelvic floor to strengthen it, therefore strengthening the muscles that surround the internal and external urinary sphincters (Box 20.20, p. 586).

Pelvic floor awareness and exercises

The individual should imagine that they are trying to stop passing flatus. They squeeze and lift the muscles around the rectum, holding this contraction for as long as possible (up to 10 seconds). The contraction is then released, and then repeated as often as possible.

This should not be tried when micturating because the detrusor will merely strengthen to overcome the resistance, which will make the incontinence worse.

Pelvic floor exercises require training and therefore referral for specialist advice from the continence nurse specialist. As it can be particularly difficult to exercise the ‘correct’ muscle group, individuals may need an invasive investigation to assess the strength of the muscles. For men, this will involve the continence nurse specialist inserting a finger into the rectum and assessing muscle tone. For women, there may be assessment of the rectal and/or vaginal muscles.

[Further reading: Getliffe K, Dolman M 2003 Promoting continence: a clinical research resource. Bailliére Tindall, Edinburgh]

Use of frequency–volume charts

Frequency–volume charts can assist in the promotion of continence (see p. 577). The chart can be used to prompt the person to attempt to void every couple of hours to prevent ‘accidents’, then gradually increase the time between voids. This timing would need to be titrated to the fluid input; a high fluid input will result in increased urine output if renal function is normal, so more voids would be required.

Types of urinary incontinence

The major types of incontinence with causes are outlined in Table 20.4 (p. 586) (see also Box 20.18).

Table 20.4 Types and causes of incontinence

| Type of incontinence | Causes |

|---|---|

| Enuresis | See Box 20.18 (p. 585) |

| Stress incontinence – leaking when coughing, laughing, sneezing or during physical activity (increases intra-abdominal pressure) | More common in women and is often associated with damage to the pelvic floor follo wing childbirth |

| Symptoms of stress incontinence worsen with age and are aggravated by obesity | |

| Stress incontinence rarely occurs in men, but may occur following prostate surgery | |

| Urge incontinence (overactive bladder/detrusor instability) – rushing to the lavatory, frequency, leaking urine | More common in women, again in part caused by anatomical changes related to childbirth, but also because of the shorter urethra and weaker pelvic floor, compared to men |

| Neurological conditions | |

| Commonest type of incontinence in older people | |

| Voiding difficulties (inefficiency) – incomplete bladder emptying, hesitancy | Commonly occurs in neurological conditions such as stroke, multiple sclerosis, e tc. |

| Occurs in women with a prolapse and men with prostatic enlargement | |

| Overflow incontinence – involuntary leak of urine from an overdistended bladder | Occurs in both men and women (less common) |

| Causes include obstruction of the urethra or bladder outlet, e.g. BPE | |

| Can occur in women with pelvic prolapse or as a complication of surgery to correct the prolapse | |

| Can be caused by underactive detrusor muscle that is associated with conditions such as multiple sclerosis and strokes or as a side-effect of some medicines | |

| Reflex incontinence – incontinence without warning | Can be caused by urethral strictures (narrowing) or an enlarged prostate |

| Functional incontinence – as an impairment of physical or mental ability | Causes include spina bifida, muscular dystrophy, etc. |

| Mixed with both urge and stress | Common in postmenopausal women |

Common findings of the effects of incontinence can include isolation and feelings of loneliness, threatening self-image and disrupting usual activities of living. However, for some, accessing healthcare can be problematic, especially if English is not their first language. Wilkinson (2001) contends that culture, religion and ethnicity can all impact on delivery and access to healthcare for certain groups, recommending a higher profile of continence services, particularly in areas where there is a high immigrant population who may not know how to access healthcare.

Management of urinary incontinence

The aim of management is to promote continence, ideally without surgical means. Simple interventions include the following:

Information about other treatment options such as bladder retraining, biofeedback, electrical stimulation, medication, e.g. trospium chloride, solifenacin succinate, duloxetine, etc. and surgery can be found in Further reading suggestions (e.g. Fillingham & Douglas 2004).

Continence nurse specialist

The management of urinary incontinence requires a multidisciplinary approach to care, i.e. specialist continence nurse, doctor (hospital doctor or GP), physiotherapist and pharmacist. An accurate diagnosis of the type of incontinence is essential. A registered practitioner should prescribe pharmacologic management options and a multidisciplinary plan devised for each person.

The specialist nurse will coordinate and manage these approaches, forming longstanding links with the person (Boxes 20.21 and 20.22, p. 588).

Specialist continence services

Think about a person you have met on placement who was unable to achieve continence.

Student activities

[Resources: Shields N, Thomas C, Benson K, Major K, Tree J 1998 Development of a community nurse-led continence service. British Journal of Nursing 7(14):824–826, 828–830; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) Management of urinary incontinence in primary care (Guideline 79, Dec 2004). Online: www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/published/index.html Available July 2006]

Mrs Begum

Mrs Begum is a 65-year-old Muslim woman who has had five children. She attends the outpatient clinic and gives a history of incontinence when she coughs or sneezes and when she holds on to her urine for too long. This has been getting worse for several years, and she admits to staying at home rather than risk incontinence. She is extremely embarrassed. Her relationship with her husband has also deteriorated.

Student activities

Continence aids (devices)

When the person, despite every effort, cannot achieve continence, the use of appropriate pads and other devices may be indicated. Devices can either be to contain the urine, e.g. with a pad that absorbs the urine, or devices that carry the urine away from the body, e.g. urinary sheaths (Conveen®) or a pubic pressure urinal, catheters (see pp. 588–592), urological stomas (see p. 596) or implantation of artificial sphincters (Sanders 2002).

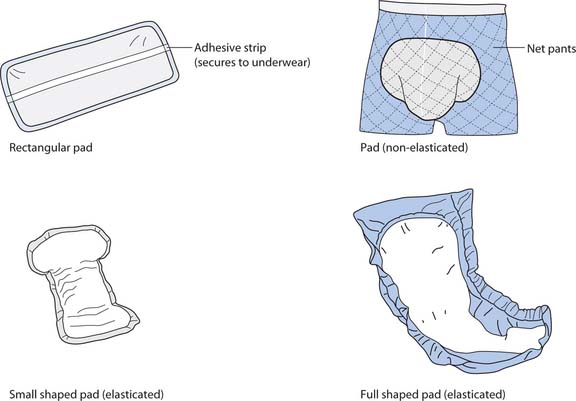

Pads

Protective pads to keep clothing or bed linen dry decrease the person’s embarrassment, the risk of pressure ulcers (see Ch. 25) and the amount of laundry needed. It is important to select the most suitable pad for the person. A woman who only has stress incontinence when she exercises can often manage with a slim pad worn inside her normal underwear, whereas a person who is incontinent of all urine may need to wear a body pad (similar in shape to a nappy) that will absorb more urine (Fig. 20.10, p. 588).

If pads are worn, particular attention should be paid to skin care. It is better to protect the skin rather than treat sore or damaged skin (Sanders 2002); this is particularly problematic in children. The perianal region is the site most commonly affected, along with the thighs and legs. To limit damage to the skin, personal hygiene should be considered a priority and advice sought from the tissue viability nurse specialist (see Chs 16, 25).

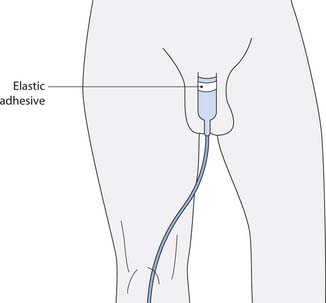

Urinary sheath

A urinary sheath (also called external catheter or condom catheter) is a sleeve of latex or silicone that fits over the penis and is attached to a night drainage or, preferably, a leg drainage bag to aid mobility. They can remain on the penis for between 24 and 48 hours and are used to promote continence where the use of pads is unwanted.

The urinary sheath is similar to a condom except that there is a short tube on the tip that allows urine to escape (Fig. 20.11, p. 588). Like most devices, urinary sheaths come in varying sizes (based on the diameter of the flaccid penis) and it is essential that the correct size be used to allow some natural movement in the penis, but not too loose that the sheath becomes detached or leaks urine (Box 20.23, p. 589). Most manufacturers of sheaths provide a ‘size’ guide to assist in correct selection of the sheath. There are various types of sheath available: self-adhesive or ones where there is a separate adhesive, some come with an applicator, whereas others depend on correct positioning manually, but they do not suit all men. Commonly reported problems include leakage, detachment or sore skin, due to the adhesive damaging the skin on the shaft of the penis, or constant irritation of the skin due to prolonged contact with urine (Sander 1999).

Application of a urinary sheath

Preparation

Explain what you are going to do and seek verbal consent; maintain respect and dignity at all times. The nurse washes and dries hands, then puts on non-sterile gloves and plastic apron.

All equipment should be taken to the bedside. Curtains must be drawn to maintain dignity. Assist the man into a sitting position.

Procedure

Care of people with a urinary catheter

Catheterization is common and all nurses will care for a person who has a catheter. Therefore this section will deal, in some depth, with the care involved. There are many reasons why a person would require catheterization, but the most common are:

The introduction of infection (see p. 576), thereby caus-ing harm to the person, is a potentially serious problem that can occur whenever a person is catheterized. For these reasons, catheterization should never be undertaken without consideration of the potential risks and alternatives to catheterization. The most common cause of hospital-acquired infections in the urinary tract is urethral instrumentation and catheterization. The incidence of UTIs in people with indwelling catheters is directly related to the duration of catheterization (Sedor & Mulholland 1999), with an average daily rate of infection of 4% for men and 10% for women; the calculated chance of remaining free of infection is only 50% (Schaeffer 2002). Hospital-acquired UTI leads to prolonged hospital stay and increased treatment costs. Once the catheter is in the bladder, the person should be encouraged to drink as much as they can, if possible more than 2L per day. This will help to ‘flush’ the urinary tract and limit the chances of UTI.

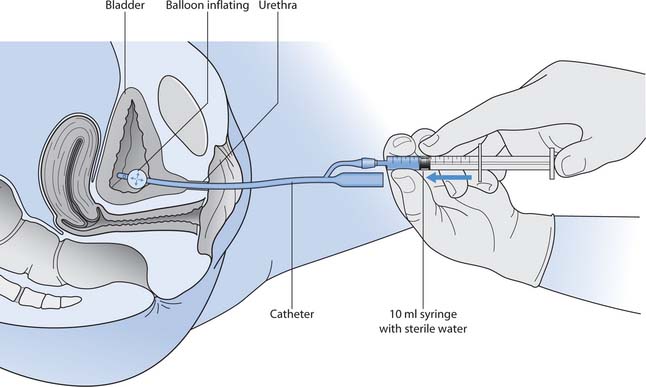

Catheters are hollow tubes that are usually inserted through the urethra into the urinary bladder, and are normally used to let urine drain from the bladder as part of medical treatment or instilling fluids (Pomfret 1996).

Occasionally a catheter will be inserted suprapubically through an artificial tract in the abdomen, above the pubic bone, into the top of the bladder. For some people, particularly those with an enlarged prostate gland or urethral stricture (narrowing), suprapubic catheterization may be the preferred option for draining urine from the bladder. The insertion of a suprapubic catheter tends to be completed by medical staff, although some senior nurses have been trained in this procedure.

Clean intermittent self-catheterization (ISC) is another method of draining urine from the bladder (Box 20.24).

Box 20.24 Intermittent self-catheterization

The person or their carer passes a catheter into the bladder to drain residual urine, preventing damage to the bladder by overstretching (distension), reducing infection and minimizing incontinence (Barton 2000). ISC can be used for people with, for example, multiple sclerosis, spina bifida or spinal injury.

ISC can enhance independence, since there are no obvious signs of a urinary catheter and the person can ‘control’ when they void (of great benefit to children and adults who wish to remain active), but the major advantage of ISC from a clinical perspective is that the incidence of UTI is reduced compared to indwelling urethral catheters. Additional benefits of ISC (for adults) include maintenance of sexual activity (Naish 2003).

The frequency of ISC is dependent on the person’s needs, although it is important that the amount of urine drained from the bladder does not exceed 400–500 mL because this can cause nerve damage from overstretching (Barton 2000).

In general, catheterization is an aseptic technique (see Ch. 15) although ISC may be a clean procedure. Catheterization of females is a basic nursing skill. Before nurses can perform female catheterization they must have training and supervised practice and be assessed as competent. Once assessed as competent, then female catheterization can be performed as a student nurse (Box 20.25). Male urethral catheterization is a skill that requires further training after registration. This is due to the potential harm, i.e. damage to the urethra or prostate gland, that can occur when catheterizing a male.

Female catheterization

Equipment

Preparation

Explain what you are going to do and seek verbal consent; maintain respect and dignity at all times. Ask the woman to wash and dry genitalia, assist as necessary. The nurse washes and dries hands.

Procedure

[Resource: British Association of Urological Nurses – www.baun.co.uk Available July 2006]

Types of catheter

Selection of the catheter needs to be based on the indications for catheterization and the length of time it will be in situ – this will determine whether an intermittent, short- or long-term self-retaining catheter will be used. Self-retaining Foley catheters have a balloon at the end of the catheter that is inflated after it has been inserted (Fig. 20.14). The balloon stops the catheter from falling out.

The types of catheter and their uses are:

Catheter length

Catheters come in different lengths for men and women (Box 20.26). The ‘male’ length catheter is almost twice as long as the ‘female’ length catheter. No attempt should be made to insert a female length catheter into a male.

[From Robinson (2001)]

Catheter materials

The length of time that a catheter can remain in situ is dependent on the material that it is made from (Table 20.5, p. 592).

| Length of use | Catheter material |

| Short term (0–14 days) | Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) |

| Latex – check for allergies (both person and staff) | |

| Short term (0–4 weeks) | Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)-coated latex |

| Long term (0–12 weeks) | Silicone-coated latex |

| Hydrogel-coated latex | |

| 100% silicone |

The ‘short-term’ catheters easily become encrusted or coated with the debris from the urine in the bladder. Longer-term catheters, e.g. the silicone- or hydrogel-coatedcatheters, tend to encrust at much slower rates than short-term catheters, and are therefore used in people who need a catheter in situ for more than 2 weeks.

Catheter lumen size

Each type of catheter is produced in different sizes. The size of the internal diameter is measured in Charriére scale (Ch) or French Gauge (FG). One Ch or FG equals 0.3 mm, so a 12Ch catheter is approximately 4 mm in diameter. The important point here is that the larger the Ch/FG size, the more the urethra will be dilated or stretched when a catheter is in situ.

The ‘golden rule’ for catheterization is always to select the smallest size catheter to do the job. Examples include:

Balloon size

A self-retaining catheter will come with instructions of how much to inflate the balloon once it is in situ. It is normally inflated with 10 mL of sterile water, but there is a chance that, over time, some of this fluid will leech out. The importance of filling the balloon with the correct volume is that the drainage ports in the catheter should be level; underfilling of the balloon results in a leaning over of the catheter tip, preventing drainage.

Overfilling the balloon can worsen detrusor instability or cause urine to bypass. In addition, the added volume will put pressure onto the bladder neck that can result in necrosis of the bladder neck and incontinence.

Drainage systems

The selection of a closed drainage system should be on an individual basis, but the main consideration should be whether the person is mobile or not. Leg bags are available in 350, 500 and 700 mL sizes. Women usually wear the leg bags on their thigh and men usually wear their leg bags around their calf region. The bags are secured with Velcro tapes or leg straps. Irrespective of leg bag size or location used, it is important to make sure the tubing does not become kinked, because this will prevent drainage. Dragging on the catheter, which can cause injury to the urethra and external urethral opening, must be avoided by securing the bag.

If a person is mobile they should not be encumbered by carrying a catheter bag round with them. This limits their ability to mobilize safely because they are carrying the catheter bag (see Chs 13, 18). A leg bag must be used. This allows the person to have both hands free to assist them with mobility. It also confers dignity since a leg bag is relatively discrete. Immobile or non-ambulatory people would normally use a 2L ‘night-bag’, which must be attached directly to a catheter stand to prevent dragging on the urethra and cross-infection from the floor.

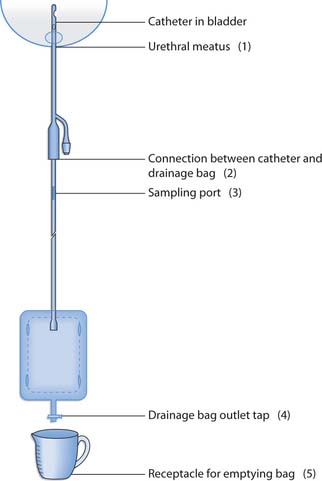

All catheter drainage bags are a ‘closed system’ and should be carefully looked after in order to minimize infection. Each time the bag is opened or drained, the potential for infection increases. Figure 20.15. illustrates the points in the ‘closed system’ at which pathogenic micro-organisms can gain entry.

Fig. 20.15 Closed drainage system showing potential entry points (1–5) for pathogenic microorganisms

If the person is using a 2L drainage bag at night, they could use a 500 mL drainage bag during the day. The 2L night bag is capped using a sterile spigot (bung) and not allowed to touch the floor as this is a potential source of infection. At all times the urine bag should be kept below the level of the bladder to prevent urine from tracking back into the bladder and causing infection. Although the catheter bags have one-way filters to prevent backflow of urine, they should be changed weekly (Drug Tariff 2003) to prevent harbouring bacteria that could cause UTI. The simplest way to ensure that this is completed is to put the date that the bag was opened on the drainage bag and record the date in the nursing notes; alternatively, the date that the bag needs to be changed can be recorded on the bag itself. Essentially, the most important aspect is that the bag is changed once per week if the individual is in hospital.

As emptying the drainage bag breaches the ‘closed’ system and increases the infection risk, it must be done carefully (Box 20.27).

Emptying the catheter bag

Preparation

Explain what you are going to do and seek verbal consent; maintain respect and dignity at all times. The nurse washes and dries hands, then puts on non-sterile gloves and plastic apron.

Procedure

All equipment should be taken to the bedside. If the drainage bag is a 2L bag, then it should already be attached to a catheter bag stand. The bag will not need to be removed.

Collecting a catheter specimen of urine

A catheter specimen of urine (CSU) for bacteriological investigation is obtained from the sampling port on the drainage tubing using a sterile syringe (Box 20.28, p. 594).

Catheter hygiene

Urinary tract infection is almost inevitable with a catheter in situ (Penfold 1999). This is because the normal protective measures, e.g. closed urethra, are bypassed. To limit the chance of infection, twice daily catheter care should be completed, e.g. during personal hygiene in the morning and before going to bed. The person who is able to use their hands and see the catheter can be taught to carry out their own catheter care.

Warm soapy water should be used to clean around the catheter where it enters the urethra. In uncircumcised males, this also involves retracting the foreskin, cleaning the glans penis and replacing the foreskin. This should be completed at least twice per day, thus preventing encrustation around the urethral meatus and removing a potential source of infection. If the person wants a bath it is important to ensure that all wounds have completely healed so that infection is not introduced or spread. In someone with a long-term catheter who wants a bath, the catheter must be disconnected from the catheter bag and a spigot used to prevent water from entering the catheter, or urine exiting the catheter when the person is in the bath. After the bath, the catheter spigot can be removed and the catheter bag reattached. It is important to ensure that the catheter bag does not touch the floor while the person is having their bath as this would allow bacteria to enter the bag and become a potential cause of infection.

The principles of care of a person with a catheter in situ are summarized in Box 20.29.

Box 20.29 Care of a person with a catheter in situ

Goal

To reduce the risk of infection, blockage (i.e. urine not flowing, low abdominal pain, spraying of urine from the urethra), trauma and discomfort.

Nursing actions

[Further reading: Atkinson K 1997 Incorporating sexual health into catheter care. Professional Nurse 13(3):146–148; Getliffe K 1995 Care of urinary catheters. Nursing Standard 11(11):47–50; Penfold P 1999 UTI in patients with urethral catheters. British Journal of Nursing 8(6): 362–374]

Removal of a self-retaining catheter

A registered nurse or doctor will decide on the removal of a self-retaining catheter. They will also decide if a catheter specimen of urine is required. If a specimen is required, collect a CSU before removing the catheter. The technique for removal is clean rather than aseptic but sterile syringes must be used. As with all procedures, the nurse must wash their hands and prepare their equipment before attempting the procedure.

All catheters should have the balloon deflated before removing the catheter, using a sterile 10 mL syringe for short-term self-retaining catheters or three sterile 10 mL syringes for long-term self-retaining catheters. It is essential to check the medical/nursing notes to see how much water was used to inflate the balloon. Although the catheter itself indicates how much water should be inserted, the correct amount is not always used. Usually, when the syringe is attached to the inflation/deflation port, the pressure in the balloon means that the syringe will automatically fill with the fluid in the balloon. If the balloon does not deflate then report this to the registered nurse.

Depending on how long the catheter has been in situ, there will be a period of time before bladder function returns to normal. People should be encouraged to drink plenty (2–3L) of fluid per day and to use a measuring jug to check how much urine has been voided at each attempt. Although the amount of urine voided varies according to age, adults should not be discharged home until they are voiding a minimum of 150 mL. The catheter can cause localized trauma or damage to the urethra and bladder. The effect of this trauma can be haematuria, but this should be minimal and resolve after a few days. People should be encouraged to seek advice from a nurse or doctor if they have any deterioration in their urinary function or if haematuria persists for more than a couple of days.

Sexual activity and urethral catheterization

There is no reason why people should abstain from sexual activity if they have a catheter in situ. The key point is that sexual activity does not have to end if one partner has been catheterized. As people will not be sure how to broach this issue with the nurses caring for them, the registered nurse should adopt a proactive approach. A simple statement such as, ‘Some people feel their sex lives change once they are catheterized, but this does not need to be the case. If you would like to discuss this, let me know and I can go through the options with you’, can help in broaching the subject, although any discussion should be with your mentor initially (Box 20.30).

Discussing sexuality

Discussing sexuality with people can be anxiety provoking for nurses – but consider their journey. For example, they might be anxious about loss of continence, undergoing invasive tests and then being ‘saddled’ with a urethral catheter. This is likely to have profound effects on their relationship with their partner.

Student activities

[Resource: Milligan F 1999 Male sexuality and urethral catheterisation: a review of the literature. Nursing Standard 13(38):43–47]

Complications of catheterization

The complications of catheterization are outlined in Table 20.6.

Table 20.6 Complications of catheterization

| Complication | Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Infection | Incorrect insertion, size, poor technique | Only undertake catheterization when assessed as competent |

| Use strict aseptic technique | ||

| Observe the urine for signs of infection | ||

| Change the catheter in accordance with manufacturer’s instructions | ||

| Change the catheter bag weekly, or more frequently if the person’s condition dictates | ||

| Pain | Detrusor spasm due to irritation; irritation to urethra/external meatus | Ensure the correct size catheter is used – large catheters will cause more pain |

| Make sure the catheter has not been in too long | ||

| Provide analgesia as prescribed and note efficacy | ||

| Medication to reduce detrusor spasm, e.g. oxybutynin | ||

| Local anaesthetic gel may be applied on the glans or external urethral meatus to reduce irritation | ||

| Blockage | Debris, e.g. blood clots, bladder tissue; catheter tubing may be kinked or the catheter bag blocked | Ensure that the catheter or drainage tube is not twisted or caught up with any equipment |

| Make sure the catheter has not been in too long | ||

| Observe the urine for blood or debris | ||

| The catheter may need to be flushed’ or a bladder washout performed | ||

| If these measures fail, the catheter will need to be changed | ||

| Bypassing | Detrusor instability | Make sure the catheter has not been in too long |

| If possible, put in a smaller size catheter | ||

| Detrusor muscle relaxants, e.g. oxybutynin | ||