Chapter 21 Elimination – faeces

Introduction

The elimination of faeces (defecation), which requires proper functioning of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, is vital in the maintenance of homeostasis. When defecation is disrupted it can adversely affect the person’s quality of life and ultimately their health. Unfortunately, many people still choose to ignore symptoms that may be indicative of disease because they are too embarrassed to discuss their bowel habit or fear the prospect of undergoing physical examination.

Meeting patients’ bowel needs was included in the original Essence of Care document in 2001, which detailed patient-focused benchmarks to assist health professionals in raising standards for basic but essential aspects of care. Bowel care is part of the Benchmark for Continence and Bladder and Bowel Care (NHS Modernisation Agency 2003). This chapter contributes to the attainment of those standards for patients/clients who require assistance with bowel care and defecation.

The chapter covers basic anatomy and physiology of normal defecation and the factors that affect it. The nursing interventions needed to assist patients with defecation, including relevant health promotion, are discussed in detail. The importance of a holistic approach to care is illustrated in the section dealing with patients/clients who experience a range of problems with defecation. The nurse’s knowledge and skill is fundamental in the assessment of bowel habit and the delivery of holistic care based on best evidence.

The nurse must work in partnership with the patient/client/parents and other health and social care professionals in the multidisciplinary team (MDT) to achieve independence of faecal elimination for the patient/client wherever possible, and to promote personal dignity when assistance is required.

An overview of defecation

This section covers the anatomy and physiology of the large intestine and defecation and the factors that affect it. In addition, holistic assessment of faecal elimination is explored and an outline of common conditions and investigations is provided.

One of the characteristics of a simple cell is that of excretion of waste products. An inability to excrete waste leads to a loss of homeostasis and disruption of cellular function. In the body, the large intestine (bowel) plays the major role in the elimination of solid waste (faeces). The elimination of faeces is known as defecation.

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract is a coiled muscular tube. It includes the:

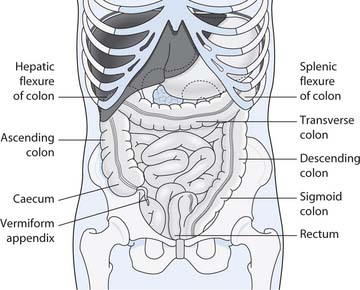

Fig. 21.1 Parts of the large intestine and their positions

(reproduced with permission from Waugh & Grant 2001)

(For further detail, see Chs 16, 19 and your anatomy and physiology book.)

Large intestine, rectum and anal canal

Much of the absorption of nutrients from the diet takes place within the small intestine (see Ch. 19). The remaining waste material then passes into the large intestine where it gradually solidifies as water is reabsorbed into the bloodstream through the bowel mucosa. The resultant material, faeces, is normally a semi-solid brown mass. Despite absorption of water, 60–70% of the weight of faeces is water. Among other constituents (see Table 21.1, p. 605), faeces contains undigested fibre residues and mucus which help lubricate the faeces or stool, aiding defecation.

Table 21.1 Characteristics of faeces and defecation

| Characteristic | Normal | Abnormal |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Infants vary: breast milk 4–6 times/day or less; formula milk 1–3 times/day | More than 6 times/day or less than once every 1–2 days |

| Adults: daily to 2/3 times/week | More than 3 times/day or less than once a week | |

| Consistency (see Fig. 21.3) | Soft, formed | A range between the two extremes of: |

| Separate hard lumps in constipation | ||

| Completely liquid in diarrhoea | ||

| Amount | Adults: depends on fibre intake, e.g. stool weight 39–223g with refined/processed diet and 71–488g with vegetarian mixed diet (Burkitt et al 1972) | Reduced volume with frequent stools |

| Colour | Infant: yellow | Clay/putty colour – absence of bile |

| Adult: brown | Green – gastroenteritis | |

| Red – eating beetroot | ||

| Blood: | ||

| Black/grey with oral iron | ||

| Pale if contains undigested fat | ||

| Shape | Resembles rectal diameter | Narrow ‘ribbon stools’ such as with increased peristalsis |

| Odour | Characteristic – depends on diet | Offensive if pus or blood is present |

| Constituents | Water | Less water in constipation |

| Epithelial cells from the intestine | More water in diarrhoea | |

| Mucus | Excess mucus and pus with inflammatory bowel disease | |

| Microorganisms | ||

| Undigested fibre (non-starch polysaccharide [NSP]) | Blood – see above | |

| Electrolytes | Foreign bodies | |

| Fat | Parasites, e.g. threadworms (see Box 21.6), tapeworm segments | |

| Stercobilin – pigment that colours faeces | ||

| Various chemicals | ||

| Flatus | Depends on diet, e.g. increases after beans, onions, etc. | May be reduced if the bowel is obstructed |

| Pain/discomfort on defecation (dyschezia) | Normally no pain or straining | Abdominal pain relieved by defecation |

| Pain in the rectum (proctalgia) and anus during defecation | ||

| Straining with constipation |

Structure

Four layers of tissue form the walls of the large intestine:

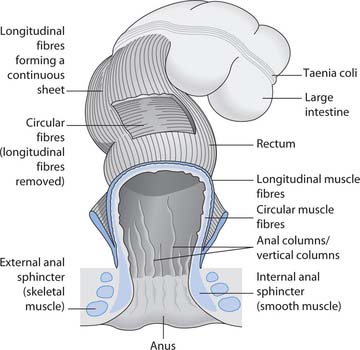

There are several modifications to the muscle layer. Two folds of the circular muscle layer form the ileocaecal valve, which controls the passage of material from the ileum to the caecum (first part of the large intestine). The circular muscle layer also forms the anal sphincters: the internal (involuntary, smooth muscle) and the external (voluntary, skeletal muscle). The longitudinal muscle layer in the colon consists of three bands called taeniae coli (Fig. 21.2). As the bands are shorter than the colon they produce a puckered or sacculated appearance. The sacculations are known as haustrations. The rectum and anal canal are completely surrounded by longitudinal muscle fibres, so there are no haustrations.

The submucosal layer contains lymphoid tissue that provides some defence from invading microbes. The mucosal lining of the colon and upper part of the rectum has a large number of mucus-secreting cells.

The mucosa in the upper part of the anal canal is arranged in vertical folds, known as the anal or vertical columns (see Fig. 21.2). Each column contains a terminal branch of the superior rectal vein and artery. The anus is lined with stratified squamous epithelium, which is continuous with the rectal mucosa above and merges with the perianal skin outside the external sphincter.

The large intestine is about 1.5 metres in length. It comprises the caecum, colon (ascending, transverse, descending and sigmoid), rectum and anal canal (see Fig. 21.1).

The caecum is the dilated first part of the large intestine. It has a worm-like appendix – the vermiform appendix – that extends from it. The appendix has a blind end and contains lymphoid tissue. Just above the lower end of the caecum there is a T-junction where the ileocaecal valve opens into it.

The colon is divided into the ascending, transverse, and descending colon in relation to its anatomical position (see Fig. 21.1). The ascending colon runs from the caecum, up the right side of the abdominal cavity. When it reaches just below the liver, it makes a 90° turn to form the hepatic (right colic) flexure. It then becomes the transverse colon where it crosses the body below the stomach until it reaches the spleen. It turns again at the splenic (left colic) flexure and becomes the descending colon as it passes down the left side of the abdominal cavity, moving towards the midline. As the descending colon enters the pelvis it becomes the sigmoid colon and then the rectum. The rectum is a slightly dilated section of colon, about 3 cm in length in infants, growing to 13 cm in adults, terminating at the anal canal.

The anal canal leads from the rectum to the exterior. It has two muscular sphincters, one internal, one external, which are involved in the process of defecation (see Fig. 21.2 and below).

Functions

Functions of the large intestine, rectum and anal canal include:

The waste material that reaches the large intestine normally remains there for approximately 12–24 hours prior to expulsion from the body as faeces. There is some digestion of the waste products by the bacteria that colonize the large intestine, but no further food breakdown occurs. The bacteria include Escherichia coli, Enterobacter aerogenes, Streptococcus faecalis and Clostridium perfringens. Many colonic bacteria have the capability to become pathogens should they be transferred to another part of the body (see Ch. 15). The bacteria metabolize remaining carbohydrates and amino acids, releasing gases, e.g. hydrogen, which contribute to faecal odour. Normally the build-up of gas is expelled from the anus as flatus. People vary but some foods such as onions tend to produce excessive flatus. Flatus has an offensive odour due to bacterial decomposition of food residues in the colon. In Western society the passing of flatus is considered as a natural bodily function, but offensive and unacceptable in public.

There is some microbial vitamin production, mostly vitamins K and B group. Absorption in the large intestine is mostly of these vitamins, some electrolytes and water.

The remaining faecal mass is propelled towards the rectum by mass movements, long, slow and powerful contractile waves that move over large areas of the colon three or four times daily. These movements usually occur during or just after eating, indicating that it is the presence of food in the stomach and small intestine that activates the gastrocolic and duodenocolic reflexes. This may then lead to defecation.

Normal process of defecation

Involuntary, reflex or automatic defecation occurs in infancy because the infant has not yet developed voluntary control of their external anal sphincter. It is usual in the second or third year of life for the child to develop the ability to override the defecation reflex (Box 21.1). The rectum is normally empty, and the defecation reflex is initiated when faeces moves into it, causing stretching of the rectal walls. The defecation reflex is mediated through the spinal cord and causes the walls of the sigmoid colon and the rectum to contract and the anal sphincter to relax, allowing faeces to pass into the anal canal. These contractions bring with them a feeling of fullness.

Box 21.1 Developing control of defecation in healthy children

In order to control defecation a child needs to:

This is assessed by an ability to convey the need to defecate, recognize an appropriate place, maintain a position for successful defecation and associate this with a positive response from grown-ups and the comfortable feeling of being clean and dry.

Once control has been achieved it is usually possible to delay the opening of the external anal sphincter (controlled through the pudendal nerve). Defecation is aided by voluntary contraction of the diaphragm and abdominal muscles to increase intra-abdominal pressure and force faeces down. This is achieved by the Valsalva manoeuvre – a forced expiration against a closed glottis (opening between the vocal cords). If defecation is delayed, the feeling of fullness will diminish as the rectal walls relax, until the next defecation reflex is initiated.

Reflex defecation may occur after a stroke, with sacral spinal cord damage or damage to the pudendal nerve.

Factors affecting defecation

Many psychological, social, cultural and physical factors can affect defecation and bowel habit; some of these are discussed below and others are outlined in Box 21.2 (p. 602).

Box 21.2 Factors that affect defecation and bowel habit

Physical factors

Facilities and environment

All the above can cause people to ignore the urge to defecate, leading to constipation.

Bowel conditions (see Table 21.21, p. 606)

Congenital and acquired bowel conditions both affect defecation, e.g. gastroenteritis; inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) causes diarrhoea; intestinal obstruction and diverticular disease cause constipation; colorectal cancer causes a change in bowel habit (alternating diarrhoea/constipation) and painful anorectal conditions, e.g. haemorrhoids, cause people to ‘put off’ defecation.

Neurological conditions

Many neurological conditions can affect the bowel or sphincter control, e.g. multiple sclerosis, paraplegia or stroke. Multiple sclerosis and paraplegia can cause constipation.

Systemic conditions

Medication (Box 21.3)

Medication and bowel habit

Think about common medications used for the patient/client group in your placement.

Despite the fact that faecal elimination is a normal bodily function, it carries a great taboo (Small 1999). In Western society this can be related to sociocultural factors, where both the anal region and the process of elimination are ‘private’.

Infants have no control over their bowel and defecation occurs involuntarily. Milk-fed infants normally have yellowish, malodorous faeces. Infants have small stomachs, reduced enzyme secretion and material moves rapidly through the GI tract, which means that four to six soiled nappies in 24 hours is not uncommon. Faecal soiling, if left in contact with the skin for a prolonged time, will lead to discomfort, distress and soreness.

The infant is dependent upon parents/carers to attend to their elimination needs until they have reached the stage of psychosocial and motor development that allows them to gain control over defecation. Parents/carers will wash the infant, change nappies and bedding in order to promote comfort. But those around the infant often show distaste when the odour of a full nappy is recognized. Potty training normally commences when the child is between 18 months and 2 years of age. However, for some children who have a motor or learning disability this may not be possible (Box 21.4).

Children with a learning disability – development in relation to defecation

Think about how this aspect of development in children with a learning disability may be different from that in other children.

Potty training is seen as a normal stage of development and parents will often produce a potty for the child to use in communal areas of the home (see also Ch. 20), sometimes encouraging the child to ‘perform’ in front of visitors and grandparents, and positively praising the successful result when the potty is used. Parents/carers often take great pride in their child’s successful potty training. As soon as potty training is achieved the child will progress to the lavatory and suddenly asking to use a potty or removing underwear in front of others results in a reprimand for the child, as this behaviour is now unacceptable. Elimination has become a private function, and this part of the body is no longer revealed to others. Behaviours learned as a child will continue to influence attitudes and behaviours related to defecation throughout life.

During childhood, experiences associated with defecation can influence a child’s toilet habits. For example, a child may refuse to use a school lavatory, or they develop a fear of a dark lavatory, which may lead to regression (return to behaviour associated with an earlier stage of development), resulting in soiling underclothes with urine and faeces as an alternative to visiting the lavatory. Constipation (see pp. 610–613) can develop if a child does not respond to the urge to defecate during school hours, retaining faeces within the bowel until they can go to their own lavatory. In a young child, control over the bladder and bowel may be lost if the child is engrossed in a game, greatly exited or experiences great fear.

During adolescence the large intestine grows rapidly to reach adult size. The lifestyle choices adopted during childhood and adolescence will influence health as an adult. For example, habits acquired during adolescence such as poor diet and inactivity can persist into adulthood, despite these being factors that a person has choice and control over in adult life.

Age changes can affect defecation. A reduction in muscle strength and mobility can make older people become susceptible to problems associated with elimination, e.g. constipation. In addition, the external sphincter may weaken or people can have reduced sensation, which may give rise to faecal soiling, e.g. when passing flatus. Older people are also more likely to take medications that affect bowel habit, e.g. non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can cause diarrhoea, which may result in loss of continence.

There is also a greater risk of developing bowel (colorectal) cancer in those over 50 years of age (see p. 607). An older person is often reluctant to seek help, due to embarrassment, concern over possible cancer diagnosis, and may associate faecal incontinence with child-like behaviour and dependence (van Dongen 2001).

Holistic assessment of faecal elimination

Many patients are embarrassed to discuss their elimination difficulties and the assessment interview requires privacy and a sensitive and skilled approach (Box 21.5). It is important to use age-appropriate language; for example, a child or indeed an adult with learning disabilities may have special names for faeces (e.g. ‘number 2’ or ‘poo’) and the nurse should always ask the parents/carers for this information.

Assessing bowel habit

How would you feel if you were asked how often you have your bowels open, and details about colour and consistency?

Threadworms

You have been asked by your mentor to help prepare an information sheet about threadworms (Enterobius vermicularis).

Student activity

Access the website below and prepare a summary of the main points concerning threadworm infestation in children and preventing reinfestation.

[Resource: Prodigy Guidance – www.prodigy.nhs.uk/guidance.asp?gt=Threadworm Available July 2006]

Colorectal cancer – early detection

Over 34500 people per year in the UK are diagnosed with colorectal cancer (Cancer Research UK 2005). It is essential to seek professional advice early if any of the following occur:

A screening programme for colorectal cancer, using faecal occult blood (FOB) samples, is being introduced in England. All people aged 60–69 years will be included by 2009 and will be screened every 2 years. People aged 70 years or over can request screening.

[Reference: Cancer Research UK 2005 – www.cancerresearchuk.org Available July 2006]

Assessing normal bowel habit – patterns of defecation and characteristics of faeces

Normal bowel habit varies from person to person and changes during the lifespan. However, in a study of adults admitted to hospital, the usual bowel habit prior to admission was five to seven stools weekly (Wright 1974).

The assessment of stool type can be enhanced by the use of a pictorial assessment tool such as the Bristol Stool Form Scale (Fig. 21.3A, p. 604) or the Children’s Bristol Stool Form Scale, which uses child-friendly language to describe stool type (Fig. 21.3B, p. 604). In addition, the nurse should measure fluid stools and record the volume lost on the fluid intake and output chart (see Ch. 19). Table 21.1 (p. 605) outlines the normal characteristics of faeces and defecation and some abnormalities.

Fig. 21.3 A. Bristol Stool Form Scale

(reproduced by kind permission of Dr KW Heaton, Reader in Medicine at the University of Bristol. ©2000 Norgine Ltd). B. Children’s Bristol Stool Form Scale (Concept by Professor DCA Candy and Emma Davey, based on the Bristol Stool Form Scale by Dr KW Heaton, Reader in Medicine at the University of Bristol. ©2005 Norgine Ltd) For further copies of the Bristol Stool Form Scales please freephone Norgine on 0800 269865 or email mss@norgine.com

Nursing history

When assessing and taking a history of a person’s bowel habit the nurse must ask about normal bowel habit and any changes that have occurred. It is important to note when any changes first occurred and for how long they have been present, as unexplained changes may indicate diseases such as cancer. The nursing history typically includes information about the following:

A holistic assessment will also ascertain how culture, beliefs and religious practices influence defecation (see p. 609). Acknowledging this individuality will ensure that the person’s needs are met.

Some people will resist the urge to defecate if this means using a lavatory other than their own and individual bowel assessment must incorporate any psychological and environmental factors affecting bowel habit.

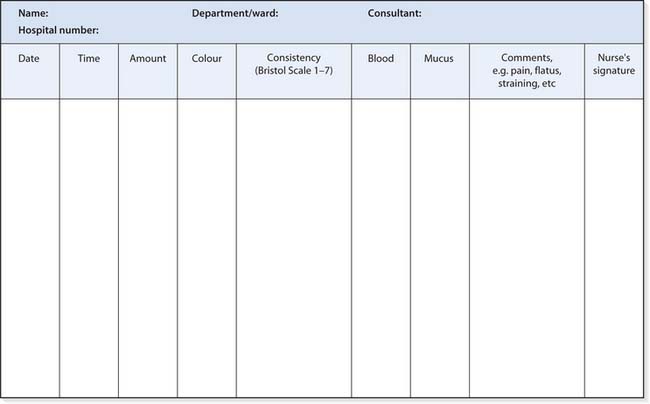

It can be helpful for patients/parents to keep a diary of bowel actions to establish a pattern; this is particularly helpful when bowel-training programmes are in progress. Nurses should record bowel actions in the nursing notes and on the appropriate charts, e.g. a stool record chart (Fig. 21.4, p. 606) and episodes of diarrhoea are measured and recorded on the fluid intake and output chart.

Common conditions affecting the bowel

Before considering individualized nursing care, nurses need some knowledge of conditions that can affect bowel habit. Some congenital and acquired conditions are outlined in Table 21.2. Readers requiring more information should consult the Further reading suggestions (e.g. McGrath 2003).

Table 21.2 Common bowel conditions

| Condition | Description |

|---|---|

| Appendicitis | Inflammation of the appendix |

| Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) | A common condition of bowel dysfunction for which no organic cause can be found |

| There is pain and passage of mucus rectally, with alternating diarrhoea and constipation | |

| Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): | Depending on the type and severity there is pain, diarrhoea, blood and mucus passed rectally, malabsorption, anaemia, weight loss and fever |

| Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis | |

| Complications include bowel obstruction and perforation, toxic dilatation, fluid and electrolyte disturbances (see Ch. 19) and colorectal cancer | |

| Diverticular disease | The presence of sacs (diverticula) in the wall of the colon |

| Increases with age | |

| May be asymptomatic, may bleed, or become inflamed to cause diverticulitis, or perforate | |

| Cancer of the colon or rectum (colorectal) | A common cancer in the UK (see Box 21.7) |

| Rectal prolapse | The rectum is displaced downward and the mucosa may be visible outside the anus |

| Associated with chronic constipation and straining to defecate | |

| Haemorrhoids (piles) | Varicosities in the rectum/anus; may be internal or external |

| Caused by increased venous pressure and may occur with chronic constipation and straining | |

| There may be itching, burning, pain and bleeding during defecation | |

| Anal fissure | Break in the skin or anal mucosa, associated with constipation |

| Causes pain/bleeding when passing faeces | |

| Imperforate anus | Congenital anomaly where an infant does not have a patent anal opening or the anus does not communicate with the bowel above |

| Corrected surgically | |

| Hirschsprung’s disease | Congenital megacolon |

| Defective nerve supply to the terminal colon leads to defective peristalsis, build-up of faeces, massive dilatation and bowel obstruction |

Common investigations

There are many different investigations used to identify disorders affecting the large bowel and elimination of faeces (Box 21.8, p. 607; see also Ch. 19).

Box 21.8 Common investigations

The following investigations may be used to diagnose or evaluate treatment for large bowel disorders:

A simple explanation of some of these investigations accessed on the BBC or the National Institutes of Health websites will help you provide patient information (see Box 21.9).

[Resources: BBC Talking to your doctor: medical tests – www.bbc.co.uk/health/talking/tests; National Institutes of Health – http://digestive.niddk.nih.gov/ddiseases/a-z.asp Both available July 2006]

Nursing interventions to promote defecation

This part of the chapter considers how nurses can assist people by promoting normal defecation (Box 21.10, p. 608), providing a suitable environment and facilities, preventing or dealing effectively with alterations such as constipation or diarrhoea and ensuring that privacy and dignity are maintained.

Promoting good habits in children

Children should be encouraged to use the lavatory prior to leaving home for school. They should be encouraged to use the school lavatory during play and lunch times but to always respond to the urge to defecate by asking to be excused if it occurs during class time. However, some children may be reluctant to defecate in the school lavatory.

Alterations in defecation can include changes in frequency or consistency, loss of continence and the care needed following the formation of a stoma. Many alterations can be anticipated by the nurse and either prevented or at least minimized, such as being aware that people who have to use a bedpan or commode (see pp. 609–610) are more likely to become constipated (Box 21.12, p. 608).

Box 21.12  EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

Bedpans, commodes and constipation

A study by Wright (1974) confirmed that use of a bedpan or commode increased the incidence of constipation in patients admitted to hospital. Wright found that 44% of people who used a bedpan or commode developed constipation whereas only 26% of patients able to use the lavatory became constipated.

Many patients will require assistance in meeting their faecal elimination needs and nurses must give full explanations and obtain consent prior to interventions. If possible, most people will want to use the lavatory. For those unable to use the lavatory, a bedpan, potty or commode will need to be provided promptly and efficiently to limit worries about ‘accidents’ and any embarrassment that the person may have. For example, where there is embarrassment about malodorous stools, the nurse can provide an air freshener to keep in the locker, which can be discretely sprayed following the use of the bedpan/commode or carried to the lavatory in a dressing gown pocket. However, the nurse must first check that the patient and those close by have no breathing difficulties or allergies.

Environment and facilities for faecal elimination

The importance of a suitable environment for bowel care is illustrated by it being a benchmark of best practice in the Essence of Care Guidance: Benchmark for Continence and Bladder and Bowel Care (NHS Modernisation Agency 2003) (Box 21.13).

Benchmarks of best practice in bowel care

‘All bladder and bowel care is given in an environment conducive to the patient’s individual needs’ (NHS Modernisation Agency 2003, p. 3).

Patients/clients must be informed about where the lavatory facilities are located. The nurse should always show them and assess whether they need help to access the lavatory. In addition, the patient is told how to call for help: verbally or by the use of the call system.

It is vital that the environment for elimination is suitable for the purpose. This requires a lavatory area to be clean, warm, dry, comfortable and private, with appropriate handwashing facilities to reduce the risk of infection (see Ch. 15). Comfortable, effective lavatory tissue must be available and, for some people, running water to wash the perianal area. The provision of adequate ventilation and/or air fresheners can reduce potential embarrassment regarding odour.

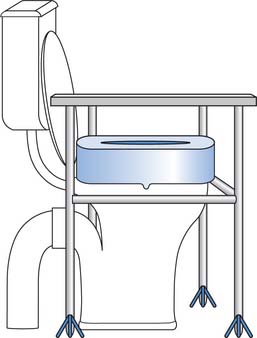

The normal position for defecation is sitting or squatting, leaning slightly forward to increase the intra-abdominal pressure with the Valsalva manoeuvre (see p. 601). The height of a standard lavatory will need to be adapted for a child in order to aid hip flexion, normally by using a footstool. A higher lavatory seat may be better for people with reduced mobility as rising from a low lavatory will be difficult; again a footstool may be needed to aid correct positioning for defecation. The provision of a higher seat and handrails can maintain independence for many people (Fig. 21.5).

Fig. 21.5 Use of raised seat and hand rails to promote independence

(reproduced with permission from Jamieson et al 2002)

Space may be an issue for a person with a disability who requires assistance to transfer to and from the lavatory. Handles fixed to the lavatory wall are a cheap and effective means of assisting with transfer. The availability of disabled lavatories is now a legal requirement in all buildings to which the public have access.

A change in environment, e.g. change in diet, being away from home, can compromise bowel habit, particularly if accompanied by a change in the person’s level of dependence. Becoming reliant on another to assist in meeting elimination needs is an area of great concern for people, and this can be directly associated with the facilities provided.

Some people will need assistance to use the lavatory (Box 21.14) or help with clothing. People may be unable to remove clothing before using the lavatory due to lack of mobility or dexterity, or lack of understanding. Various adaptations to clothing may need to be considered by the nurse in order to maintain the person’s independence and dignity (Box 21.15).

Taking a patient to the lavatory

Adaptation to clothing

Think about a person who had difficulty removing clothing in order to use the lavatory. They may have had a learning disability or dementia, or had poor dexterity following a stroke, etc.

The nurse must consider cultural needs. Many people, e.g. Sikhs, Hindus and Muslims, require that nurses of the same sex meet their intimate hygiene needs (see Ch. 16). Personal hygiene is very important and washing with water after using the lavatory is normal practice for many groups. In Islam a cleansing ritual is performed before prayers and this becomes void after urination, defecation, passing flatus or vomiting and needs to be repeated (Akhtar 2002). Muslims also prefer to wash their genitalia and perianal area with running water after using the lavatory. Offering a jug of water following elimination will meet this need. The left hand is used for personal cleansing.

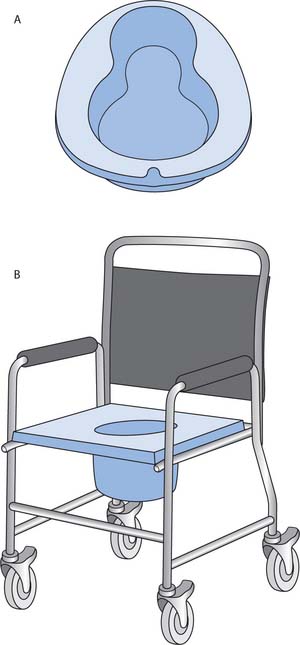

Bedpans and commodes

Some patients will need to use a bedpan or commode (Fig. 21.6, p. 610). Most people will find this embarrassing and nurses must be aware of these worries and take all necessary steps to maintain the person’s privacy and dignity and provide culturally sensitive care.

Using a bedpan may lead to worries over spillage in the bed or the escape of offensive sounds or smells in the ward. Bedpans are difficult to balance on, and getting a patient on a bedpan requires the nurse to complete an appropriate risk assessment for moving and handling (see Chs 13, 18), ensuring that neither patient nor nurse safety is compromised. Box 21.16 (p. 610) outlines how the nurse can provide a bedpan or commode safely while maintaining privacy and dignity.

Providing a bedpan or commode

If a commode is used, ensure that slippers are worn by the patient to prevent slipping. Assist the patient from the bed to the commode, offering assistance to remove/move clothing. Once the patient is safely seated on the commode cover their knees with a blanket to promote dignity and keep them warm

A commode can be used for patients with more mobility. It has the advantage of providing a more normal position for defecation and can be used in the lavatory for greater privacy. The commode can be used beside the bed, if privacy and dignity can be ensured (see Box 21.16). Alternatively, the patient may be transferred from the bed to a wheelchair, taken to the lavatory and there transferred to the commode, which may then be moved over the lavatory. Again a risk assessment is undertaken and safe moving and handling procedures adhered to (see Chs 13, 18). The commode should never be used for transport between the bed and lavatory due to the risk of cross-infection.

Constipation

Constipation can be difficult to define. There is no accepted definition for constipation as it depends on individual interpretation (Winney 1998). For example, some people may pass stools more frequently than others. Normal bowel movement can occur anything from three times a day to twice a week (Crouch 2003). A useful definition may be ‘an alteration in normal bowel movements, resulting in the less frequent and uncomfortable passage of hard stools’.

For the most part, constipation is a temporary condition and not life threatening. People often treat it with over-the-counter laxatives without any advice from a healthcare professional. This, however, can lead to recurrence of the condition and a key part in the management of constipation is education for prevention (see Box 21.10, p. 608). When there is no underlying medical cause for recurrent episodes of constipation, the term chronic idiopathic constipation is used. Many people do seek medical advice, with constipation accounting for approximately three million general practitioner (GP) consultations each year in the UK, with an estimated 10% of the population taking laxatives regularly (Moayyeddi 1998).

Constipation may be secondary to systemic or bowel disease and a thorough assessment on presentation is undertaken to ensure that underlying disease is detected.

Contributing factors and causes of constipation

The dry, hard stools of constipation occur when the colon absorbs too much water. This happens when the muscular contractions of the colon are sluggish, causing the stool to move too slowly through the colon. Lack of fibre in the diet reduces bulk, slowing down motility. Most people will experience an episode of constipation at some time or another such as following childbirth or surgery.

Constipation affects all age groups but it is the very young and older adults who are affected most. People worry more about their bowels as they age, but ageing does not in itself slow down stool movement in the colon (Norton 1996). This is usually due to other factors such as lack of exercise and a reduction in the consumption of fruit, vegetables and bread, increasing the risk of constipation. Fibre intake is positively associated with increased frequency of bowel movement and faecal mass (Bennett & Cerda 1996). The prevalence of constipation may be increasing as modern food processing methods have produced a refined fibre-free diet (Taylor 1997). Other risk factors contributing to the development of constipation may be reduced fluid intake. Older people may drink less in an attempt to control urinary incontinence (see Ch. 20), particularly if mobility is poor and assistance with reaching the lavatory is required.

Box 21.2 (p. 602) outlines the many factors that affect defecation and bowel habit, including those that cause constipation. However, nurses should always be aware of situations when constipation is likely to occur and anticipate the need for interventions, e.g. laxatives when opioid drugs are used for pain relief (see Ch. 23).

Effects of constipation

The effects of constipation are outlined in Box 21.17.

Assessment of constipation

A thorough and complete assessment and history are essential to determine the normal bowel habit for the person (see pp. 603–605) and to identify contributing factors or causes for the condition (see Box 21.2, p. 602). Consti-pation can be a chronic problem for many individuals.

Self-assessment of bowel habit is also helpful and the person or parent can be taught the use of the Bristol Stool Form Scale (see Fig. 21.3, p. 604). The person may be asked to log their dietary and fluid intake and keep a record of daily exercise.

A doctor or a registered nurse who is appropriately trained and competent will perform a physical examination. This will include:

Management of constipation

Most people who experience constipation will not require extensive investigation and can be successfully treated with lifestyle changes that include increasing fluid intake, exercise and fibre content of the diet (Box 21.18, p. 612).

Increasing fibre intake

Increasing fibre intake is necessary to prevent constipation and is also part of any care plan for the management of constipation. Fibre contributes to the formation of a bulkier stool, as it is not digested. The bulkier stool stimulates the colon to produce a strong peristaltic movement leading to the need to defecate (Crouch 2003).

The following foods contain high levels of fibre (see Ch. 19):

In the short term, laxatives may be prescribed to relieve constipation. They are only used if the person is constipated and the cause is not an undiagnosed condition such as intestinal obstruction. Laxatives (or aperients) are drugs that cause the bowel to empty in a variety of ways. There are four basic types, plus bowel cleansing solutions (Table 21.3):

Table 21.3 Laxatives – oral and rectal

| Type | Examples and routes | Action/comments |

|---|---|---|

| Bulking agents | Bran, ispaghula and methylcellulose (also a faecal softener) – oral | Increase fibre in the stool, thereby increasing the water absorption by the stool |

| Produces softer, bulkier stool, which stimulates peristalsis and is easier to pass | ||

| Note: Sufficient oral fluids are required to prevent intestinal obstruction | ||

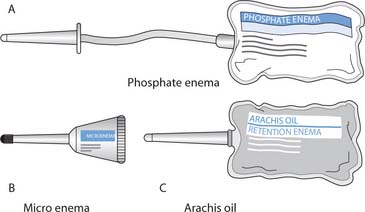

| Faecal softeners | Arachis oil retention enema | Softens the stool and also lubricates the hard stool, making it easier to pass |

| Note: Rectal Arachis oil is obtained from peanut/groundnut oil and must never be administered to a person with peanut allergy | ||

| Stimulants | Senna – oral | Stimulate the nerves in the colon and increase intestinal motility |

| Bisacodyl – oral and rectal (suppositories) | ||

| Docusate sodium (also a softener) – oral and rectal (micro-enema) | ||

| Dantron – oral | ||

| Glycerol suppositories (rectal) | ||

| Sodium picosulfate – oral | ||

| Osmotic laxatives | Lactulose – oral | Act by drawing water into the colon or retaining water in the colon by osmosis, thus distending the colon and stimulating peristalsis |

| Phosphate and sodium citrate enemas, e.g. Fleet® Ready-to-use Enema, Micralax® | ||

| Micro enema® – rectal | ||

| Macrogols, e.g. Idrolax®, Movicol®, Movicol® | ||

| Paediatric Plain – oral | ||

| Bowel cleansing solutions | Various preparations, e.g. Fleet Phospho-soda®, Picolax® | Used before examination, barium enema or bowel |

Laxatives can be administered orally, rectally as suppositories or as an enema for severe constipation. Many patients will be able to self-administer enemas or suppositories and parents/carers can also be shown how to administer them to children and others. However, it does require a degree of mobility and manual dexterity. People who self-administer should be directed to the manufacturer’s instructions and advised to contact their practice nurse or general practitioner if problems arise.

Bowel cleansing solutions are used to empty the lower bowel before investigations that include colonoscopy and barium enema X-ray (see Boxes 21.8 and 21.9, p. 607) and before surgery. Laxatives are also prescribed to prevent constipation, e.g. when people are receiving morphine or other opioid drugs to relieve pain.

Mary – preparation for colonoscopy

Mary noticed blood on the tissue after defecation and eventually plucked up courage to see her GP who referred Mary to the hospital for a colonoscopy.

Student activities

[Resource: Bulmer F 2000 Bowel preparation for rectal and colonic investigation. Nursing Standard 14(20):32–35]

Readers requiring more information about a specific laxative are directed to the British National Formulary (www.bnf.org.uk).

Enemas

An enema is the introduction of fluid into the rectum or lower bowel for the purpose of producing a bowel movement or instilling medication. The drugs administered rectally include corticosteroids used in inflammatory bowel disease, etc. (see Ch. 22).

The are two types of enema available for the management of constipation: evacuant and retention.

Before administering an enema it is necessary to obtain informed patient/parent consent.

In order to give informed consent the patient must understand what an enema involves. A clear explanation is required so that the patient understands what is required of them, i.e. retention of the enema solution. The patient must understand the benefits and risks of the intervention in relation to symptom relief, and that this will be short term. The nurse should also consider who is best to administer the enema. For example, a nurse of the same gender as the patient may minimize embarrassment and should be offered whenever possible.

There are contraindications to giving an enema. These include:

The enema must be prescribed by an appropriately qualified practitioner and local policy followed regarding checks on medication and patient identity for the administration of medicines (see Ch. 22). Box 21.19 (p. 614) outlines how the nurse can administer an enema safely and effectively while maintaining privacy and dignity.

Enema administration – adults

Preparation

Procedure

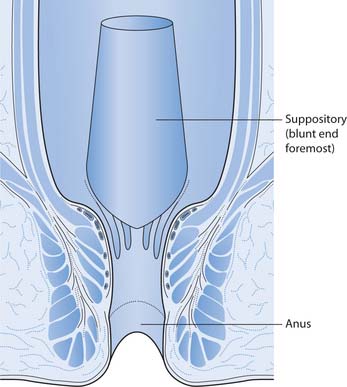

Suppositories

Rectal suppositories, like enemas, are used to evacuate the lower bowel. They are also used to administer medications, e.g. bronchodilators, antibiotics and analgesics (see Chs 22, 23). More commonly they are used to relieve constipation. Lubricant suppositories such as glycerol can be purchased without prescription (see Table 21.3).

The procedure for administering suppositories is similar to that for an enema in respect of physical and psychological preparation (Box 21.20, p. 615). If adminis-tering a medicated suppository, the patient should be encouraged to first empty their bowel, as this enables better retention of the suppository while the drug is released and absorption is more effective if the rectum is clear of faeces.

Administration of suppositories

Preparation

Procedure

There are contraindications to giving suppositories. These include:

Manual faecal evacuation

For patients who suffer chronic constipation a manual faecal evacuation may be required. Manual faecal evacuation must only be undertaken by a registered practitioner who is trained and competent in the procedure. Prior to this procedure, the patient’s pulse rate is recorded, noting rhythm, regularity and strength as well as rate (see Chs 14, 17). This will serve as a baseline, as it is important to respond to changes in the patient’s condition during this procedure, as manual evacuation can cause vagal stimulation and slow the heart rate. The presence of a second person allows for constant monitoring during the procedure, and provides reassurance for the patient. Privacy and dignity for the patient must be maintained at all times.

Diarrhoea

Diarrhoea is defined as an abnormal faecal discharge, usually characterized by the frequency at which it occurs and its watery appearance (King 2002), i.e. a loose watery stool that occurs more frequently than normal. Diarrhoea occurs in many gastrointestinal disturbances and may be acute or chronic. Loose stools indicate that the bowel mucosa is irritated and is not absorbing enough water from the stool. There can be rapid transit of material through the bowel.

Contributing factors and causes of diarrhoea

Chronic diarrhoea may be associated with underlying pathology such as IBD (see Table 21.2, p. 606) or mal-absorption due to lactose intolerance. The causes of acute diarrhoea include:

Box 21.2 (p. 602) outlines other factors that cause diarrhoea. Nurses should always be aware of situations when diarrhoea may occur and anticipate the need for interventions that include ensuring the person’s bed/room is close to the lavatory.

Effects of diarrhoea

The effects of diarrhoea are outlined in Box 21.21 (p. 616).

Assessment of diarrhoea

A thorough and complete assessment and history are essential to determine the normal bowel habit for the person (see pp. 603–605) and to identify any contributing factors or causes for the diarrhoea (see Box 21.2, p. 602).

Episodes of diarrhoea are recorded on a stool chart (see Fig. 21.4, p. 606). Frequent, loose watery stools should be measured and recorded on the fluid intake/output chart in order to assess fluid loss. Self-assessment of bowel habit using, for example, the Bristol Stool Form Scale (see Fig. 21.3, p. 604) can be helpful. The person may also be asked to record their dietary intake.

A specimen of faeces may be collected for microbiological examination (Box 21.22, p. 617).

Collection of stool/faecal sample

The patient or parent/carer often collects the sample at home and should follow the instructions provided with the sample container. Stool samples are also collected for faecal occult blood testing and for the presence of parasites.

Preparation

Management of diarrhoea

Management depends on whether the diarrhoea is acute or chronic. It is important to prevent dehydration and adults and children are advised to take frequent sips of water. Oral dehydration salts can be purchased over-the-counter following advice from the pharmacist (see Ch. 19).

The advice about eating has changed and both adults and children are encouraged to eat high carbohydrate foods, e.g. rice, pasta, etc. if they feel well enough (NHS Direct 2005). Where people do not feel like eating they should continue to drink and try to eat when they feel able.

Babies with diarrhoea should be fed as normal if they will breastfeed or take formula milk. The formula feed should be made up at the usual strength. If oral rehydration preparations are used, breast or formula milk should continue to be offered between oral rehydration fluids (British National Formulary 2005).

Adults may use antidiarrhoeal drugs, e.g. loperamide. However, anyone with a high temperature, or blood or mucus in their stool, should first seek medical advice. Parents and carers should not give over-the-counter antidiarrhoeal drugs to children. If symptoms persist, or signs of dehydration are present, medical advice must be sought.

Other nursing interventions for a person with diarrhoea include the following:

Faecal incontinence

There is a lack of consensus about a definition for faecal incontinence, but it can be described as the inappropriate or involuntary passage of faeces (Royal College of Physicians 1995). The defining characteristics for faecal incontinence include:

Faecal incontinence is a taboo subject with a high degree of social stigma; it is often associated with regression and lack of control. Faecal incontinence tends to be underreported because people find it repugnant and are often reluctant to seek help. The reluctance to report faecal incontinence means that prevalence is underestimated. Faecal incontinence is more common in older people and affects more women than men. Studies have reported the prevalence amongst those aged over 65 years to be higher. The Royal College of Physicians (1995) found that 15% of people in the community aged over 65 years were affected.

Faecal incontinence in children is referred to as encopresis, defined as repeated involuntary or voluntary faecal soiling of clothing by a child over 4 years of age (see p. 619). Around 1.5% of children still lack bowel control by their 7th birthday (Royal College of Physicians 1995).

Continence services are available, and need to be accessible for all and this is made clear in the benchmark of best practice: ‘Patients have direct access to professionals who can meet their continence needs and their services are actively promoted’ (NHS Modernisation Agency 2003). There is a need for an integrated continence service that spans both primary and secondary care settings, focusing on healthy living and ensuring specialist continence advice for maintaining both faecal and urinary continence and care if continence is lost (Box 21.24). The philosophy underpinning such services is that promoting continence will reduce the incidence of incontinence.

Contributing factors and causes of faecal incontinence

The causes of faecal incontinence include:

Factors that contribute to faecal incontinence include dementia, lack of facilities or poor access, immobility and poor manual dexterity.

Box 21.2 (p. 602) outlines factors that affect bowel habit, many of which can lead to loss of continence, e.g. faecal impaction with overflow (spurious) diarrhoea. Nurses should always be aware of situations when continence may be lost and anticipate the need for interventions that include the use of laxatives to minimize constipation when patients are prescribed opioids.

Effects of faecal incontinence

The effects of faecal incontinence are outlined in Box 21.25.

Access to a lavatory or other facility is a major concern for all patients who experience urgency to defecate. This is a common problem for people with IBD who also have bowel actions that are explosive, noisy and malodorous (Box 21.26).

Urgency and defecation

23-year-old Rosa has IBD and needs to plan any journeys very carefully because if she is unable to respond at once to the urge to defecate she will soil her underwear. She needs to know the location of every public lavatory and always has clean underwear, a bag for soiled pants and wet wipes in her bag.

Assessment of faecal incontinence

A full patient history and physical assessment are essential to determine the normal bowel habit for the person (see pp. 603–605), and to identify any contributing factors or causes for faecal incontinence (see Box 21.2, p. 602). Physical factors such as mobility and manual dexterity and access to appropriate facilities for defecation must form part of any assessment, along with assessment of factors such as cognition and motivation.

Episodes of incontinence can be recorded on a stool chart (see Fig. 21.4, p. 606) and self-assessment of bowel habit using, for example, the Bristol Stool Form Scale (see Fig. 21.3, p. 604) can be helpful. The person, parent or carer may also be asked to record food and fluid intake and regular exercise pattern.

Managing faecal incontinence

The management of faecal incontinence will depend upon the cause. It is often secondary to constipation and may be resolved through the following:

A toileting programme that closely follows the person’s previous normal bowel habit, such as sitting on the lavatory after breakfast, can be very helpful. For patients requiring assistance to the lavatory, an immediate response from the nurse to the patient’s request is essential before the gastrocolic reflex subsides.

The specialist continence nurse/adviser can provide information and education about prevention of faecal incontinence and measures to regain continence (see Further reading, e.g. Wells 2003).

When patients have impairment of both sensation and sphincter control, as in conditions such as multiple sclerosis, the bowel is usually emptied by routine administration of enemas or suppositories (see pp. 214, 215). The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence provide guidance for the management of bowel problems for people with chronic conditions which recommend that the patient be assessed and considered for the routine use of enemas or suppositories (NICE 2003).

Antidiarrhoeal drugs such as loperamide may be used to produce a more formed stool if the faecal incontinence is due to a very liquid stool.

More advanced methods such as biofeedback may be used by specialist nurses and physiotherapists to retrain the anal sphincter muscles that control release of bowel movement. Other methods for managing faecal incontinence may be more radical and involve surgery; these interventions will be specific to the cause, i.e. rectal prolapse.

Continence may not be achievable and nurses will need to plan care that minimizes the effects while continuing to promote continence. The care will include:

Encopresis

There is sometimes confusion caused in diagnosis of encopresis and faecal soiling with other childhood problems. For example, fear associated with using the lavatory may lead to a child soiling their clothes. Children who are isolated and lonely may smear faeces; however, this is different from encopresis, as they have control of their bowel and their behaviour is a symptom of an emotional disorder (Heins & Ritchie 1985).

In most cases of encopresis, prolonged constipation and faecal impaction is the most likely cause. Stretch receptors in the rectum are continually stimulated because the rectum is full of faeces and this leads to the prohibition of signals and loss of the normal response of muscle contraction. It can take 2–6 months for an overstretched rectum to return to normal functioning (Heins & Ritchie 1985).

For a school-age child, social acceptance is important; a feeling of belonging and inclusion among peers will aid development of self-esteem and confidence (Gross 2001). A child with encopresis is likely to experience difficulties (Box 21.27). The child may be unable to wash/change in privacy after faecal soiling and this may lead to ‘being smelly’ and a focus of fun for other children. The child may avoid activities such as games where there is a need to undress in public. Opportunities to go on school trips and sleepovers may be rejected to avoid embarrassing situations. The response from parents/carers is important, as family support is vital; reprisal and rejection from constant criticism and telling off will only lead to further isolation and lowering of self-esteem (Gross 2001).

Encopresis – the emotional and social effects

Sam is 8 years old and attends primary school. Over the last few months Sam has developed faecal soiling.

The MDT will usually be involved in planning strategies and supporting the child and family in resolving the problem. The composition of the team will depend on the cause of the child’s encopresis. They may include the specialist continence nurse, GP, psychologist, school nurse, community nurse and dietitian.

Strategies used to resolve encopresis will include dealing with constipation and education (see pp. 611–612) about diet and exercise to avoid recurrence once the current episode has been relieved.

The bowel has to regain the ability to respond to stretch receptor signals, and also to contract and relax to expel faeces from the bowel. Recording the times that faecal soiling occurs will give some indication of when the child should be encouraged to visit the lavatory. Visiting the lavatory each morning will reduce the amount of faeces left in the bowel and hence the risk of soiling later in the day. A breakfast comprising a high-fibre cereal such as porridge will help but a laxative may be necessary.

Choosing high-fibre options such as fruit and vegetables from school dinner menus or healthy sandwiches made with granary bread with salad and a fruit snack, plus sufficient water for the day, is essential. Again, visiting the lavatory after meals (usually 20 minutes) when the bowel muscles begin to respond to the feeling of fullness is important. Informing teachers of the need to access lavatory facilities, even though this may disrupt lessons, is important, as is access to somewhere private to change for physical education lessons.

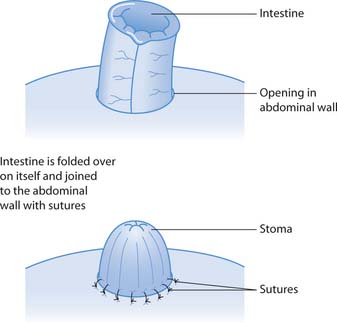

Caring for a person with a stoma

A stoma is an artificial opening of an internal organ, such as the bowel discharging faeces onto the surface of the body (Fig. 21.10). An outline of stoma care is provided here but more information is available in the Further reading suggestions (e.g. Bruce & Finlay 1997).

Approximately 80000–100000 people in the UK have a stoma. Colostomy patients form the largest proportion of patients requiring a stoma (Black 2000).

A colostomy may be performed as a temporary measure to divert faeces away from a healing anastomosis (join) or diseased area, allowing bowel continuity to be restored at a later date. When this is not possible the colostomy will be permanent.

The anatomical position of the stoma will determine the consistency of faecal output. An ascending colostomy will produce soft/liquid stool, while transverse and descending colostomies produce an increasingly formed stool because a greater length of colon is available to absorb water from the faeces. Some patients may require an ileostomy, in which the end of the ileum or a loop of the ileum is brought out to the surface of the abdominal wall. The stool from an ileostomy will be a liquid/soft stool.

Stoma formation may be undertaken for a variety of conditions. These include:

Specific preoperative care for patients having a stoma

Preparation for stoma formation will depend on the reason for surgery, and whether it is planned or undertaken as an emergency. Readers are directed to Chapter 24 for details of general preoperative care.

Physical and psychological preparation should include:

Box 21.28 Role of the specialist stoma care nurse

The stoma care nurse is part of the MDT involved in supporting adults, children and families in their preparation and adaptation to life with a stoma. They work in acute hospitals and the community.

The role involves the following:

Manufacturers of stoma care products often employ stoma care advisers (not to be confused with specialist stoma care nurses) to support patients and professionals but also to promote particular products.

Mary – information needs before stoma formation

Mary has been diagnosed with colorectal cancer. The position and extent of Mary’s cancer means that the colon cannot be joined together (an anastomosis) and a permanent colostomy is necessary.

Student activities

Specific postoperative care for a patient having a stoma

Postoperative care following stoma formation is also influenced by the reason for surgery, and whether it was planned or undertaken as an emergency. Readers are directed to Chapter 24 for details of general post-operative care.

Specific postoperative care should include:

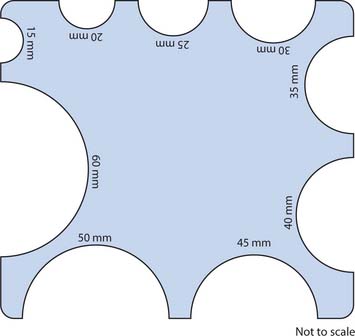

Appliances and skin care

It is usually 48 hours postoperatively that the drainable appliance put on in theatre is changed for the first time (Black 2000). It is usual practice to use a clear plastic pouch when in hospital as this allows the nurses to observe the stoma and any output directly. Patients are initially very distressed by the odour produced when the pouch is emptied or changed, and should be reassured that this will decrease as diet is reintroduced (Black 2000). Pouches that are opaque and have flatus filters and contain charcoal to reduce odour can be introduced later should they be required (see p. 622).

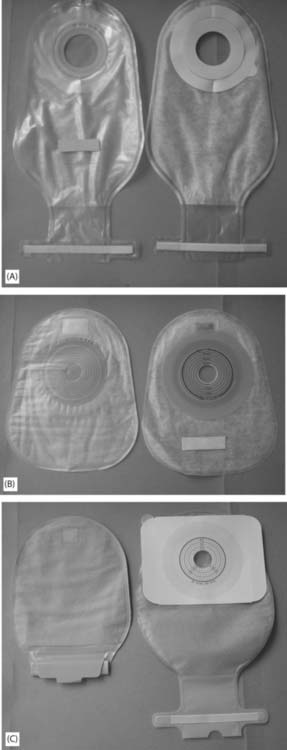

Appliances may be either one- or two-piece, with a flange, sealed or drainable (Fig. 21.11). A two-piece appliance allows the flange to remain in contact with the skin and the pouch can be removed and changed without disturbing the flange. The flange is usually changed every 2–3 days; however, it may be left for longer when skin is sore to avoid further irritation (manufacturer’s guidelines must always be followed). Sealed pouches are often used with a colostomy, and although the contents can be flushed down the lavatory, the bags must be placed in a plastic disposal bag and disposed of with normal household waste.

Fig. 21.11 Selection of stoma pouches/bags – front and back views: A. Drainable pouch/bag. B. Sealed pouch/bag. C. Opaque pouch/bag (drainable).

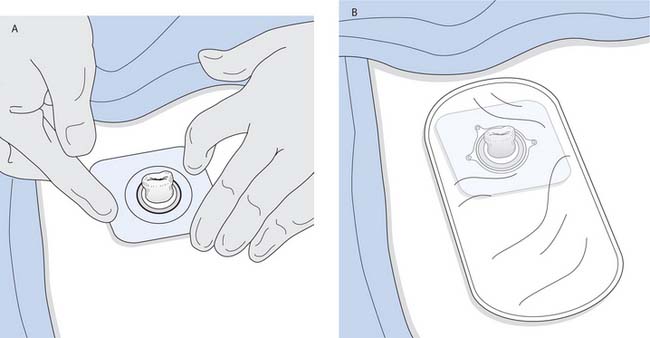

Fig. 21.13 Changing a stoma pouch/bag: A. Fitting the flange. B. Stoma pouch/bag in place

(reproduced with permission from Nicol et al 2004)

Patients with an ileostomy generally use a drainable pouch. Patients are encouraged to protect the skin around the stoma with a barrier cream.

Skin must be kept in optimum condition to tolerate the stoma appliance. Karaya, a natural absorbent rubber, revolutionized stoma care in the 1950s. However, some patients developed allergies and difficulties with adherence (Black 2000). It is still used by some patients who have had a stoma for many years.

In 1972 Stomahesive® was introduced. It is a flat wafer that is resistant to temperature, perspiration and the gastrointestinal fluids which come into direct contact with it. Stomahesive can be tolerated by inflamed and weepy skin and can be left in place for up to 15 days without requiring change.

When appliances are changed the skin should be cleansed and dried. Protective wafers should be used to fix appliances to the skin. If skin is prone to inflammation the longer the wafer can remain in situ the better, meaning a two-piece appliance would be worn.

The therapeutic relationship between the patient and the healthcare team is important in assisting the patient in accepting the stoma. By seeing the nurses at ease when providing early stoma care, patients/parents and carers are more likely to accept the changes to their physical appearance. Box 21.30 outlines the procedure for changing a stoma pouch.

Changing a stoma pouch

A planned teaching programme ensures that the patient does not feel rushed and has the opportunity to develop confidence and dexterity with the procedure. Initially, pouch changes are managed by the bedside but the aim is for the patient to change the appliance in the bathroom. This will increase confidence for coping at home. In the case of a child, the parents/carers will be taught to care for the stoma until the child is able to self-care.

Equipment

Preparation

Continuing stoma care – advice and support for patients

Various designs and colours of pouches are available, including some designed specifically for children. Pouches and appliances are designed to lie flat, be odour-free, rustle-free and to be unnoticeable under clothing. Some pouches have an inner lining that can be flushed with the contents down the lavatory, and soft cloth covers are available for some pouches. Appliances can be left in place or removed during bathing/showering. Once the patient has found a suitable appliance, the stoma care nurse will advise them about obtaining supplies after discharge.

Prior to discharge all stoma patients should be given contact numbers/email address for the stoma care nurse. When patients are discharged from hospital they are supplied with sufficient appliances for at least the first week with extra to cover any public holidays. The district nurse or GP will provide prescriptions for appliances. Continuation of supplies may be direct from the manufacturer or from the local pharmacy.

Following discharge, the GP, district nurse and the stoma care nurse who works between the hospital and community assist the patient/parent to prevent or overcome any problems that arise. Other members of the MDT such as the dietitian may also provide specialist advice. In the case of children the specialist community public health nurse (health visitor) and school nurses will also be involved in their ongoing care.

Clothing which has some stretch and give provides most comfort by avoiding the restrictions of waistbands and belts.

Most patients will quickly discover any food or drink that upsets the function of their stoma, e.g. changes in stool consistency, odour, blockage or excess flatus. However, they should be given advice regarding eating a balanced diet (see Ch. 19) and informed about food and drink that are known to cause problems. For example, beer and onions can cause flatus, and eggs and onions are associated with odour. Many patients find that a bulkier stool is more manageable and will want to increase their intake of fibre with, for example, bananas, boiled rice, pasta, etc.

Support groups are very useful sources of information and support (see ‘Useful websites’, p. 625). These groups provide information about travelling and holidays, special appliances for sports and swimming for adults and children, etc. Patients whose stomas function at regular times can use a special cap while swimming instead of a pouch.

| BBC | www.bbc.co.uk/health |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Ileostomy and Internal Pouch | www.the-ia.org.uk |

| Support Group | Available July 2006 |

| National Advisory Service for | www.patient.co.uk/show |

| Parents of Children with a Stoma (NASPCS) | doc/267391771 |

| Available July 2006 | |

| National Association for Colitis and Crohn’s | www.nacc.org.uk |

| Available July 2006 | |

| National Digestive Diseases | http://digestive.niddk.nih.gov |

| Information Clearing House | Available July 2006 |

| National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence | www.nice.org.uk |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Prodigy – practical support for clinical governance | www.prodigy.nhs.uk |

| Available July 2006 | |

| The Continence Foundation | www.continence-foundation.org.uk |

| Available July 2006 |

Abd-el-Maeboud KH, el-Naggar T, el-Hawi EM, et al. Rectal suppositories: commonsense mode of insertion. Lancet. 1991;338(8770):798-800.

Akhtar SG. Nursing with dignity – Islam. Nursing Times. 2002;98(16):40.

Bennett WG, Cerda JJ. Dietary fibre: fact and fiction. Digestive Disorders. 1996;14:43-58.

Black P. Continuing professional development. Stoma care. Nursing Standard. 2000;14(41):47-53.

British National Formulary. 2005. Online: http://www.bnf.org.uk. Available July 2006.

Burkitt D, Walker A, Painter N. Effect of dietary fibre on stool and transit time and its role in the causation of disease. Lancet. 1972;2(7792):1408-1412.

Crouch D. Easing the pain of constipation. Nursing Times. 2003;99(11):23-25.

Gross RD. Psychology: the science of mind and behaviour, 4th edn. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 2001.

Heins T, Ritchie K. Beating sneaky poo. ACT Health Authority, Canberra Publishing and Printing Co, 1985. (see Useful websites available from NASPCS)

Jamieson E, McCall J, Whyte L. Clinical nursing practice, 4th edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2002.

King D. Determining the cause of diarrhoea. Nursing Times. 2002;98(23):47-48.

Mallet J, Doherty L, editors. The Royal Marsden Hospital manual of clinical nursing procedures, 5th edn, London: Blackwell Science, 2000.

Moayyeddi P. The patient with constipation. Nursing Update. 1998;24 June:1302-1306.

National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Multiple sclerosis: management of multiple sclerosis in primary and secondary care. Clinical Guideline No 8. London: NICE, 2003.

NHS Direct. 2005 Health Encyclopaedia. Online: www.nhsdirect.nhs.uk/en.aspx?ArticleID5131.

NHS Modernisation Agency. 2003 Essence of care guidance – patient-focused benchmarks for clinical governance. Online: www.modern.nhs.uk/home/key/docs/Essence%20of%20Care.pdf.

Nicol M, Bavin C, Bedford-Turner S, Cronin P, Rawlings-Anderson K. Essential nursing skills, 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Mosby, 2004.

Norton C. The causes and nursing management of constipation. British Journal of Nursing. 1996;5(20):1252-1258.

Royal College of Physicians. Incontinence: causes, management and provision of services. Journal of the Royal College of Physicians London. 1995;29(4):272-274.

Small A. Are you sitting comfortably. Nursing Times. 1999;95(1):24-25.

Taylor C. Constipation and diarrhoea. In: Bruce L, Finley TMD, editors. Nursing in gastroenterology. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1997.

van Dongen E. It isn’t something to yodel about, but it exists! Faeces, nurses, social relations and status within a mental hospital. Aging and Mental Health. 2001;5(3):205-215.

Waugh A, Grant A, editors. Ross and Wilson anatomy and physiology, 9th edn, Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2001.

Winney J. Constipation. Elderly Care. 1998;10(4):26-31.

Wright L. Bowel function in hospital patients. Royal College of Nursing Research Project Series 1, number 4. London: RCN, 1974.

Bruce L, Finlay T, editors. Nursing in gastroenterology. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1997.

Colley W. Practical procedures for nurses. Constipation – 1: Causes and assessment. Nursing Times. 95(20), 1999. Supplement 27.1

Colley W. Practical procedures for nurses. Constipation – 2: Treatment. Nursing Times. 95(21), 1999. Supplement 27.2

Jooton D. Nursing with dignity – Hinduism. Nursing Times. 2002;98(15):38.

Kaur B Gill. Nursing with dignity – Sikhism. Nursing Times. 2002;98(14):39-41.

McGrath A. Nursing patients with gastrointestinal disorders. In: Brooker C, Nicol M, editors. Nursing adults. The practice of caring. Edinburgh: Mosby, 2003.

Wells M. Maintaining continence. In: Brooker C, Nicol M, editors. Nursing adults. The practice of caring. Edinburgh: Mosby, 2003.

REFLECTIVE PRACTICE

REFLECTIVE PRACTICE HEALTH PROMOTION

HEALTH PROMOTION

NURSING SKILLS

NURSING SKILLS

CRITICAL THINKING

CRITICAL THINKING