Chapter 25 Wound management

Introduction

Tissue viability encompasses a variety of clinical issues/problems. Although primarily related to the management of wounds, the term also includes preventing tissue damage and care of vulnerable skin. Skin can become damaged for many reasons, including trauma such as cuts, as a result of problems such as incontinence or during surgery, or may arise from an underlying disease, e.g. leg ulceration.

Although many aspects of wound care have been traditionally deemed a nursing role, good tissue viability care depends upon holistic assessment of the patient/client and involvement of the relevant members of the multidisciplinary team (MDT).

In order to care for patients/clients with the potential for or compromised tissue viability, healthcare professionals must understand the normal structure and role of the skin and changes during the lifespan (see Ch. 16). This knowledge assists in determining deviations from the normal processes and helps to inform appropriate care plans and management.

Tissue viability includes the whole spectrum of patient/client care, including all age groups and all branches of nursing. Specific issues and problems may arise in particular areas of nursing, e.g. babies, older people with dementia or people with limited mobility, but a broad understanding of the fundamental principles gives a basis from which any nurse can begin to provide appropriate care.

Types of wound

The many different types of wound are classified in a variety of ways. This may relate to the aetiology (cause), the amount of tissue loss, whether they heal by primary or secondary intention (see p. 705) or the length of time they usually take to heal. There are also many subcategories within the definitions which provide a more accurate description and assessment of the wound.

Wound classification and categories

Most commonly wounds are described as being either acute or chronic (Table 25.1). Acute wounds are those where healing is straightforward and follows an orderly sequence, whereas chronic wounds are slow to heal with some delay in the healing process. Chronic wounds – pressure ulcers and venous leg ulcers – are covered later in the chapter (see pp. 714–725). This definition of what is acute or chronic is overly simplified and there are many examples where these definitions are inappropriate. For example, a surgical wound that becomes infected, dehisces (bursts open) and fails to heal for many months does not fit the definition of an acute wound (Fig. 25.1); equally a laceration of the leg in an older woman with underlying venous disease is unlikely to heal in a straightforward way unless the underlying disease is also treated (Box 25.1).

| Type of wound | Acute or chronic | Primary or secondary healing |

|---|---|---|

| Surgical wound | Acute | Primary |

| Donor sites where skin has been removed for a skin graft | Acute | Secondary |

| Traumatic wound | Acute | Primary or secondary |

| Burn | Acute | Secondary |

| Fungating wound which occurs as cancer infiltrates the skin | Chronic | Secondary |

| Pressure ulcer (see pp. 714, 716–721) | Chronic | Secondary |

| Leg ulcer (see pp. 721–725) | Chronic | Secondary |

| Diabetic foot ulcer | Chronic | Secondary |

Acute wounds

Acute wounds may be categorized by type and cause of the injury. They include:

Burn wounds are classified according to the depth and surface area of the skin affected (see Ch. 13).

Surgical wound categories (see Ch. 24)

The most common acute wounds result from surgical procedures that are frequently an elective (planned) event. Surgical wounds are further subdivided into categories based on the risk of wound infection occurring. Leaper and Harding (1998) describe four risk categories which relate to the reason for surgery and the organs involved, as follows:

Wound healing

In order to deliver appropriate care to patients/clients it is vital that nurses understand the processes by which wounds heal. The process involves a sequence of overlapping events or stages. It is important to link the theory to clinical practice so that recognition of the stage of wound healing informs treatment objectives. This is particularly important when documenting assessment findings and clinical decisions. It is logical to understand normal wound healing before considering abnormal and compromised healing.

Some injured tissue heals by regeneration and this can be seen in very superficial wounds affecting only the epidermal layer of the skin because these wounds heal without leaving any visible signs on the skin. Wounds affecting deeper layers of the skin are not able to do this and heal by a process of repair. New connective tissue is formed and healing occurs by fibrosis with scarring.

There are major differences in the healing process within fetal tissue. Wounds heal without scarring during the first 6 months of gestation; thereafter, healing resembles that occurring after birth. Fetal tissue heals by regeneration characterized by little inflammation, fibrosis or scarring.

Wounds can heal by primary or secondary intention. Primary intention healing occurs where there is minimal tissue loss and it is possible to draw the wound edges together with sutures (stitches) or clips. Secondary intention healing occurs where there is tissue loss and it is not possible or desirable to draw the wound edges together. Wounds subject to extensive tissue loss usually heal by a process of granulation (formation of new capillaries and the growth of new healthy moist, red tissue in the wound bed), contraction and epithelialization (epithelial cells move across the wound once it is filled with granulation tissue to resurface the wound).

Stages of wound healing

Wound healing is often described in four stages. These are:

The four stages are considered separately but it is important to remember that the stages overlap, and progress and regress according to the circumstances of the patient’s environment, lifestyle and underlying conditions (Fig. 25.2, p. 706).

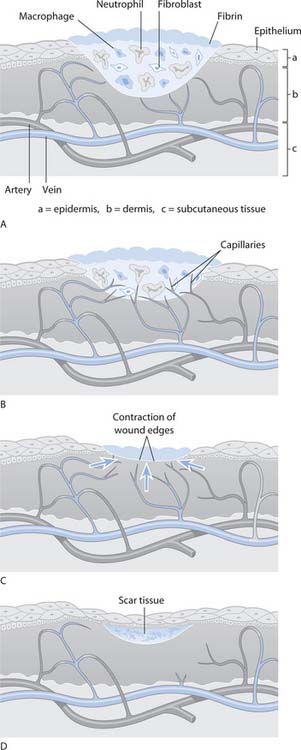

Fig. 25.2 Stages of wound healing: A. Inflammatory. B. Proliferative. C. Maturation. D. Mature (early)

(reproduced with permission from Brooker & Nicol 2003)

Stage 1 – Vascular response (0–3 days)

Stage 1 involves processes that stop bleeding (haemostasis) and encourage migration of the cells that initiate healing. The blood vessels constrict initially and platelets accumulate at the breach in the vessel and stick together (aggregate), forming a plug to stop the bleeding for a short time. This is followed by blood coagulation whereby coagulation factors cause the formation of a fibrin (insoluble substance formed from the soluble protein fibrinogen) clot. Bleeding ceases as blood cells are trapped in the fibrin mesh to form the clot, which eventually dries to a scab.

Stage 2 – Inflammation/inflammatory response (1–6 days)

Once the clot has formed and bleeding stopped, the blood vessels dilate (vasodilatation). This is caused by the release of histamine by mast cells (a type of white blood cell [WBC]) that migrate to the wound. Gaps open up between the cells in the capillary walls and fluid leaks out into the tissues. The extra fluid and increased blood supply from the dilated capillaries result in redness, heat, swelling and pain, with some loss of function/movement in the area. This response can continue for some days. Therefore it is important that wound assessment (see p. 708) includes wound history, otherwise these signs may lead to an assumption of wound infection.

Vasodilatation and increased blood flow in the area mean that other WBCs (neutrophils and monocytes, which become macrophages) are attracted to the area by protein growth factors, which stimulate specific cell division and proliferation. The WBCs migrate to the site by a process called chemotaxis in order to defend the body against bacteria and remove debris from the wound. The neutrophils and macrophages do this by engulfing bacteria and debris, a process known as phagocytosis.

Other growth factors released by WBCs stimulate fibroblasts (immature cells that form connective tissue) and the growth of new blood vessels (angiogenesis) in the wound. Fibroblasts present in the fibrin clot begin to form collagen, a protein that provides the supportive framework in connective tissue. The wound contains fibrin debris known as slough (soft, creamy yellow tissue comprising cellular debris, which rises to the surface of the wound). Once enzymes in the wound fluid liquefy the slough, granulation tissue is visible in the wound bed. Increased capillary permeability leads to fluid loss, or exudate (fluid containing serum, nutrients such as proteins, proteolytic enzymes and cell debris), from the wound.

An extracellular matrix (ECM) is formed in the wound, which serves as a platform over and through which cells can move and be supported as they act in the wound. The ECM constantly breaks down and reforms during healing and serves as a scaffold for new blood vessels.

Stage 3 – Proliferation (3–20 days)

Growth factors continue to stimulate fibroblasts and the ECM supports the new tissue. Other growth factors encourage angiogenesis and epithelial cell proliferation and migration. The deficit resulting from tissue loss is filled with new blood vessels and granulation tissue. At the same time, fibroblasts change shape, link with other fibroblasts and form a net-like structure. The changes result in fibres of collagen which give the elasticity needed to retain shape and resist injury. The collagen fibres begin to contract, each cell pulling on others. The wound shrinks in size and now has a covering of new, paler epithelial tissue (epithelialization). The wound is healing by granulation, contraction and epithelialization.

Stage 4 – Maturation (21 days to .1 year)

In normal, healthy people this stage often begins at about 21 days. The wound appears ‘healed’ because it has a covering of epithelial tissue (new skin). The collagen matures, gains strength and has a more orderly structure, and the new blood vessels mature. Capillary dilatation reduces and the number of fibroblasts decreases. Because healing occurs by repair rather than regeneration, the healed wound leaves the skin looking different. This is scar tissue and, depending on the wound and the individual, takes a variety of forms. Scars are formed from fibrous tissue, which initially appears red and slightly raised, and are itchy. Eventually this will settle to an area commensurate with the original wound dimensions and flattens. Scar tissue takes a long time to mature, possibly up to 2 years, during which tissue is remodelling. Scars have little elasticity and are generally paler than surrounding skin once they have matured.

Factors influencing healing

The prerequisites for normal wound healing include:

Healing is influenced by a variety of factors and circumstances. Some factors that delay healing are local to the wound, including wound complications, whereas others are systemic or patient-related.

Local wound factors

A variety of local wound factors can impair or delay healing (Box 25.2), as follows:

Inappropriate wound management, poor assessment and clinical decision-making, and failure to set treatment objectives can all contribute to delayed and impaired wound healing.

Problems with wound healing may compromise scar formation. The scar, which remains proud of skin level, can be dry, flaky and itchy. In some darker skin types keloid scarring can occur. This is a hard, raised overgrowth of scar outside the proportions of the original wound, which can cause the person considerable emotional and physical problems.

Wound complications

Wound healing is seriously affected by complications that include:

Systemic or patient-related factors

Many patient-related factors have an impact on healing, e.g. age and nutritional status. Patient-related factors that may affect healing should be considered during the holistic assessment (see pp. 708–712). Factors may impact directly on the healing process, e.g. severe malnutrition, or may impact on the planned objectives of care, e.g. for a patient/client with arterial disease it may not be possible to heal the wound and an alternative objective would be determined or the suggested time to healing modified (see pp. 713–714).

Age

The skin of older people often thins and becomes more vulnerable to damage (Norman 2004). When trauma occurs, healing may be delayed because of slower cell turnover, reduced collagen synthesis and age-related poor circulation (Box 25.3).

Nutritional status (see Ch. 19)

Many individual nutrients are vital in wound healing (see p. 706) and a deficiency in any can affect healing. Protein–energy malnutrition (PEM), for example, results in insufficient resource for the increased needs of a healing wound.

Dehydration (see Ch. 19)

Dehydrated cells are not able to function efficiently and cell replication will be impaired. All cells need a moist environment for survival and movement.

Systemic diseases

Many diseases impair or delay wound healing. These include:

Medication (see Ch. 22)

Several commonly used drugs have a negative impact on wound healing (Box 25.4). These include:

Smoking

The adverse effects of smoking tobacco on wound healing include local hypoxia and altered platelet aggregation, which increase the risk of thrombus (clot) formation.

Stress

Psychological factors affecting patients/clients also influence wound healing. Stress and anxiety result in the production of glucocorticoid hormones, e.g. cortisol (see Ch. 11). These are anti-inflammatory and may inhibit fibroblasts, collagen synthesis and granulation (Keicolt-Glaser et al 1995). They may also reduce blood supply. Everything possible should be done to relieve stress and anxiety, including ensuring adequate sleep and rest (see Ch. 10).

Wound management

This part of the chapter outlines wound assessment, cleansing, débridement and dressing products.

Good wound management is dependent on a thorough holistic assessment of the patient/client and their wound. This is followed by the setting of appropriate patient/client-centred objectives and the use of evidence-based wound care to encourage healing or, where this is not possible, to manage the symptoms appropriately.

Wound assessment

Assessment of the wound is only one part of holistic assessment and should never be carried out in isolation. A full history is taken to identify any systemic patient-related factors which may influence healing, e.g. malnutrition, and also the causation and time scale of the wound.

Wound assessment is a multifaceted process and, in order to make best use of the information, it should be documented systematically and objectively. A variety of wound assessment charts exist but, whichever chart is selected, it should address all the elements of a holistic assessment outlined below. Reassessments should be carried out at least weekly but may be more frequent depending on the individual wound characteristics (see Ch. 14).

Wound characteristics

When assessing a wound, several characteristics should be considered, including:

Cause of the wound

The cause may impact on further assessment and care planning. The cause will also help determine the risk of complications. For example, if the knife causing the wound is contaminated with soil, the risk of infection is much higher than if it was a clean knife from a dishwasher. Sometimes the cause is immediately obvious, but in other cases the cause may only be determined by careful and systematic history taking and in some instances sensitive questioning (see Ch. 9).

Particular consideration should be given to patients/clients whose wounds are self-inflicted, as their need for psychological support may be greater than an immediate need for wound care (Box 25.5). Frequently a MDT approach to care is required, with involvement of mental health teams, psychologists and social services. The MDT is also important in managing patients with other types of wound and their individual input should always be considered. Many traumatic wounds require input from both physiotherapists and occupational therapists to maintain function and mobility; equally these team members help to manage chronic wounds such as venous leg ulcers where increased mobility may accelerate healing.

Self-harm emergency care

A friend has told you that her daughter is cutting herself. On occasions the injury has bled for some time but the girl was too frightened to go to the Emergency Department. Your friend asks you what will happen if they seek help.

Student activity

[Resource: National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) 2004 Self harm: short-term treatment and management. Online: www.nice.org.uk/pdf/CG016publicinfoenglish.pdf Available July 2006]

Location

Initially wound location is considered in relation to its proximity to vital structures, as life-saving care takes priority. Location may provide clues to the cause of the wound. Buttock wounds tend to be automatically classified as pressure ulcers but this is often incorrect, as pressure ulcers usually (but not exclusively) occur over bony prominences (see pp. 719–720). Wounds appearing on or between the buttocks are more frequently caused by incontinence (see Chs 20, 21).

The position of the wound may also impact on the dressing choice (see p. 714), e.g. keeping a dressing on the sacrum is notoriously difficult because it is subject to shear and friction forces. Equally if the wound is easily visible, such as on the face or hand, the cosmetic impact of the dressing may be the overriding consideration. When managing wounds over or close to joints, consideration must be given to maintaining mobility and joint function.

Condition of the surrounding skin

The condition of the surrounding skin may indicate the patient’s/client’s general health or the presence of problems, e.g. eczema. This impacts on dressing choices; for example, if the surrounding skin is very fragile it may not be possible to use adhesive dressings. If there is gross oedema present there may be seepage of fluid onto the skin, which will lead to maceration (damage caused by excess moisture leading to overhydration and increased susceptibility to trauma) if not adequately managed. Fluid is trapped on the skin surface when the dressing used does not manage the exudate adequately or is not changed frequently enough. Maceration also increases the risk of infection.

Size

The size of the wound is accurately measured and recorded in order to evaluate progress. Sometimes wounds appear to get bigger during healing; this may be because the full extent was previously masked by necrotic tissue or thick slough.

Measurement can be undertaken by using a disposable paper ruler to record the length and width. However, as most wounds are irregular in shape this does not record the overall size.

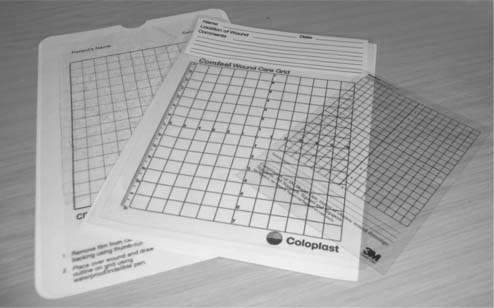

More frequently a tracing is taken of the outline of the wound using a transparent overlay (Box 25.6, p. 710). An overlay may be either a commercial wound tracing sheet (Fig. 25.3) or the clear part of a dressing packet. As the packet contained a sterile dressing the inside should be sterile and therefore safe to put in contact with the wound. This outline may then be traced onto paper and stored in the notes. If commercial tracing sheets are used, the backing film that had contact with the wound is removed and the initial tracing stored in the notes.

Measuring wounds

Preparation

Ensure the patient/client understands what is happening and has given consent. If necessary, ensure that appropriate analgesia is administered. Ensure privacy. It may be necessary to clean the wound to remove any surface debris (see p. 713). Mark the grid with head and foot, left and right.

Procedure

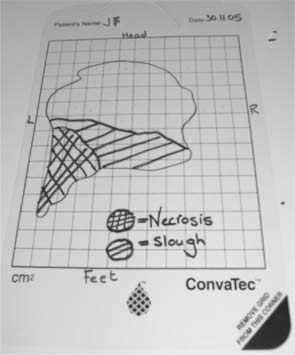

A tracing can also be used to record areas of different tissue types, e.g. slough or necrosis (Fig. 25.4, p. 710 and p. 713). The change in percentages of these tissues may indicate wound progress as much as a change in overall size.

If tracing materials are not available, a simple line drawing can be made with measurements marked on, as well as the areas of different tissues. Alternatively, a photographic record of wound size and condition can be obtained. If photography is used, written consent must be obtained from the person (see Chs 6, 7) and this must detail what the photograph may be used for, i.e. for use in the records or used for teaching purposes or for publication, when further written consent will be required by the publisher.

Types of tissue present in wounds

In addition to the size of the wound, it is important to record the type of tissue visible in the wound bed. For example:

Exudate

All wounds produce protein-rich exudate throughout the healing process. Exudate bathes the wound, keeping it moist and supplying the substances needed for healing (see p. 706). In acute wounds, the level of exudate decreases as healing progresses; however, in chronic wounds exudate may persist or increase.

It is important to monitor the quantity of exudate but in practice this is not easy. Most wound assessment charts use subjective assessment of exudate quantity, e.g. low, moderate or high level, or symbols (1, 11, 111). While most experienced nurses would claim to understand the meaning of these descriptions, they are not objective measurements and different nurses may have differing views of what constitutes a particular level. For this reason it is better to use an objective descriptor.

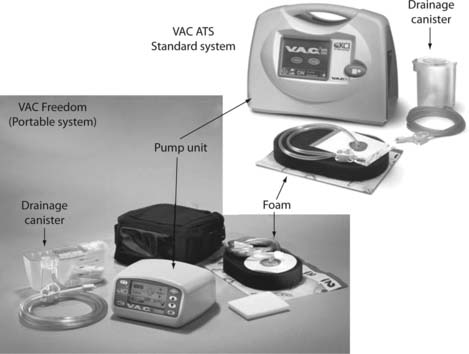

It is not usually possible to record the volume of exudate unless a wound drainage bag or vacuum-assisted closure system is being used (Fig. 25.5). What can be recorded is the frequency with which the dressing becomes saturated and requires changing. For example, if initially the dressing requires changing twice daily and later progresses to once every 2 days, a clear reduction in exudate can be recorded or vice versa. This is dependent upon the same dressing type and size being used for consistency.

When observing for differences in exudate volume it is important to consider what else is happening to the wound. There may be an apparent increase in exudate but this may be due to the presence other fluid, e.g. that produced by some dressings.

The type, colour and consistency of the exudate should also be recorded. Changes in the exudate are often the first signs of changes occurring within the wound. Exudate may be described as:

The consistency may vary from watery to thick and almost semi-solid.

Odour

Most wounds produce a typical smell, and odour within the wound is not necessarily abnormal. However, changes or increase in odour may suggest the presence of infection or progress within the wound. The odour normally becomes stronger and less pleasant as necrotic tissue is rehydrated and liquefies. Equally, some dressing products produce a typical odour. Assessment of odour is subjective and is often recorded as 1, 11 or 111, but again this does not allow for comparison. One way of objectively describing the odour is to record when it is first detectable. For example:

Wound pain

It is only recently that pain has been widely acknowledged as being a problem in all wound types (see Ch. 23). A recent consensus document (World Union of Wound Healing Societies 2004) suggests that nurses:

When assessing wound pain, the type, nature and intensity should be determined. The type of pain relates to what causes the pain: is it constant background pain, related to procedures such as dressing changes, or incident pain related to things such as coughing? This is important, as it influences the type of analgesic required. The patient should be encouraged to describe the nature of the pain; common words include dull or aching (e.g. with venous leg ulcers), burning, itching pain (with skin reactions) or sharp, stabbing pain. Pain should be assessed using an appropriate pain-rating scale (see Ch. 23).

Social factors

Wounds may impact on social aspects of life, and social factors may influence a person’s wound and its management. For example, many older adults with leg ulcers become socially isolated, as they stay at home because of pain and embarrassment about the look and/or odour of the ulcer. Other groups have difficulty accessing services for wound care due to social circumstances, e.g. homeless people and people with wounds related to drug misuse where there is considerable stigma associated with the cause.

In children, older adults and other vulnerable groups such as people with a learning disability, the presence of traumatic wounds should alert the nurse to the possibility of non-accidental injury; however, it should be borne in mind that children, for example, frequently injure themselves (see Chs 3, 6).

Most dressing products and care from a tissue viability nurse are increasingly available in both hospital and community settings. However, some products remain non-prescribable in the community.

Environmental factors

The care environment may influence the management and also the risk factors such as infection. In hospital, the patient/client is vulnerable to cross-infection from contact with other patients and exposure to different microorganisms, which are more virulent/pathogenic than typical microorganisms found outside hospital (see Ch. 15). At home, the infection risk differs and there is less risk of cross-infection; however, the home environment is not always ideal. Many people have pet animals and both personal hygiene and general cleanliness vary considerably.

If the person is well and mobile, consideration must be given to where they go and what they do and what impact this will have on their wound. Children need a dressing that will withstand play and school activities. Work environments, e.g. where dressings are likely to become wet or contaminated, are considered in planning wound management. Caring for people with mental health problems presents particular difficulties and many usual nursing interventions cannot be used. For example, it may be judged unsafe to use a compression bandage for a patient with suicidal ideation or if other patients in close proximity are at similar risk.

Organizational factors

Nurses in both community and hospital usually deliver wound care. Care delivery should be at a time that meets the needs of both the patient/client and the need to provide appropriate care. Patients and families should be as fully involved as possible in the care provided. Involvement requires that they receive adequate and appropriate information, at an appropriate level and in a language they understand.

For children and those with ongoing care needs, the family and/or friends are frequently involved in providing wound care; this relies upon the carer being both willing and able to do this. For children, involvement of the family or their own participation in care of the wound can help to reduce pain and relieve anxiety. Family or patient participation in wound care, especially at home, means that the care can be provided at the most appropriate time and is not dependent on a nurse visiting. However, additional support is required to ensure that ongoing wound assessment is maintained and that the family feels fully supported and confident to call for nursing assistance when it is needed.

The need for input from other healthcare workers should be assessed. These include:

Input from most of these groups is equally important in caring for patients/clients with any type of wound. Other individuals whose participation may be needed include pharmacists, vascular surgeons and plastic surgeons, as well as domestic staff whose role in maintaining cleanliness is crucial.

Wound cleansing

Cleansing is important to clear loose debris from the wound. Frequently this must be undertaken to facilitate wound assessment, particularly in acute traumatic wounds where the area may be obscured by blood or debris. However, in the absence of debris, it is not always essential to cleanse the wound each time the dressing is changed (Flanagan 1997). Wound healing occurs in a warm, moist environment and cleansing may cool the wound. The surrounding skin should always be cleansed to remove dressing material or exudate which has a detrimental effect on the skin. Wound cleansing is achieved by irrigating the wound with warm fluid, either normal saline or tap water to prevent cooling. Aseptic technique is used when there is an invasive component, such as in theatre, but otherwise a clean technique is used (see Ch. 15).

Many people cleanse their wounds by showering or by irrigating/soaking in warm tap water (Günnewicht & Dunford 2004). Soaking is particularly suitable for leg wounds as the limb can be immersed in a bucket or bowl lined with a new plastic liner for each patient/client to reduce the risk of cross-infection.

Cotton wool/fibrous material must not be used to cleanse wounds as debris can become incorporated into the wound bed, causing inflammation. Slough or necrotic tissue may persist in the wound and this should be removed or débrided (see below). Dead tissue may act as a focus for infection, physically impede wound healing and cause, or increase, odour.

Wound débridement

Débridement is the removal of devitalized (dead) tissue which is adherent to the wound bed or the removal of foreign material from the wound. There are various methods that include:

Patients/clients require careful preparation for larval therapy. The practitioner must be confident in handling the larvae and be able to reassure and support the patient/client and their carers (Box 25.7).

Wound dressings

Given the huge variety of wound dressings it is important to know how dressings work so that appropriate choices can be made. No single dressing will be appropriate for all wound types so nurses need know the wound circumstances for which each dressing is designed.

Aims of treatment

Following assessment, it is usual to develop a care plan to meet specific wound objectives. While it is tempting to set the overall aim of ‘to heal the wound’, this is too long term and lacks guidance for immediate wound management. More detailed objectives for specific wounds would typically include:

Additional objectives may be required for the prevention or management of infection. Specific objectives related to the wound aetiology should also be set, e.g. pressure reduction in the management of a pressure ulcer. These objectives must be considered together with other aspects of patient care and may have to be modified to meet more pressing objectives, e.g. increasing mobility.

Choosing an appropriate dressing

Essentially the choice of dressing is determined by assessment findings, the aims of treatment and patient/client preferences. However, three key factors must be con-sidered in dressing selection:

An estimation of exudate level (see p. 711) can assist in dressing choice. Selecting a dressing designed for low levels of exudate, e.g. film dressing, may cause maceration and leakage on a wet wound, whereas choosing a dressing designed to cope with high exudate levels may allow drying of a wound with only minimal exudate.

The condition of the surrounding skin helps in determining the dressing type. Adhesive dressings may cause trauma on removal if applied to fragile skin. Where infection or copious exudate necessitates frequent dressing changes, it would be inappropriate to use adhesive dressings as these are designed to remain in place for a few days. The surrounding skin may be macerated or excoriated due to damage from excess fluid and for this reason the selected dressing should be designed to hold exudate within its structure away from the skin. It is important to read the manufacturer’s instructions for use, as some dressings are cut to the shape of the wound and some to lie over the wound and surrounding skin.

Patient preference is an important consideration when assessing the patient, the wound and selecting dressings (Box 25.8). Before using any product there must be explanation for, and negotiation with, the patient who is to wear the dressing.

Ethical and religious considerations

Some dressings may contain human and/or cow or pig tissue. It is important that nurses provide full information about a particular dressing and ensure that patients/clients or carers give informed consent prior to its use.

It is vital that the manufacturer’s instructions for dressing use are read and understood before the final decision is made to apply any dressing. These instructions state at least:

If nurses have questions about a dressing they should seek the advice of the tissue viability nurse who may contact the manufacturer directly. Nurses must read professional literature and other sources information in addition to that from manufacturers. It is vital to appraise the clinical use of products and consider carefully the evidence base to support them. Manufacturers provide telephone and email facilities to answer questions.

Types of dressing

The main dressing categories and their functions are summarized in Table 25.2. Some are primary (applied directly onto the wound surface), some are secondary (cover a primary dressing) and some can be used as either a primary or a secondary dressing.

| Dressing | Function | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Gauze type/padding | ||

| Low adherent (film with thin layer of padding) | ||

| Paraffin gauze (gauze mesh coated with white soft paraffin and sometimes other substances, e.g. chlorhexidine) | ||

| Silicone (thin layers of netting coated with soft silicone gel) | ||

| Hydrogel (soft amorphous gel, squeezed from a tube onto the wound bed or available in sheets) | ||

| Film (adhesive polyurethane film) | ||

| Foam (polyurethane foams that absorb exudate but hold fluid away from the skin to minimize maceration) | ||

| Hydrocolloid (mixture of components that include cellulose, gelatin and/or pectin combined with adhesives and other materials) |

They are intended to stay in place for a few days and frequent removal may cause skin redness and discomfort

|

|

| Alginate (derived from seaweed; available in flat sheets or ribbons/ropes for use in cavity wounds) | ||

| Hydrofibre (cellulose spun to produce sheet and ribbon forms) | ||

| Topical antimicrobials (dressings containing silver or iodine) | ||

| Deodorizing dressings (dressings containing carbon/charcoal which attracts chemicals causing malodour) | Use on malodorous wounds, e.g. those containing dead tissue, fungating or infected wounds | |

| Honey (Manuka) sometimes mixed with waxes/oils (a paste squeezed from a tube or as dressing material coated with honey) | ||

| Vacuum-assisted closure (topical negative pressure; see Fig. 25.5, p. 711) |

Note: Always refer to the manufacturer’s application instructions.

In addition, there are ancillary products used in wound management. These include:

Chronic wounds

Chronic wounds are those where healing is delayed or interrupted for some reason; most have persistent or recurrent inflammation and tend to have high levels of exudate. Most chronic wounds, including pressure ulcers and leg ulcers, will heal by secondary intention. Management of these wounds depends as much on management of the underlying cause as care of localized wound factors.

Pressure ulcers

Pressure ulcers (pressure sores, decubitus ulcers) are an area of localized damage to the skin and underlying tissue caused by pressure, shear or friction, or a combination of these (European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel [EPUAP] 1999) (Fig. 25.6, p. 716). They are common and a survey suggests that, on average, 22% of hospitalized patients develop pressure ulcers (EPUAP 2002).

All grade 2 and above pressure ulcers should be documented as a clinical incident and the circumstances thoroughly investigated (NICE 2005). They occur in all age groups and across all specialities and care settings. They cause patients and carers distress, pain and embarrassment; they increase morbidity and increasingly are recorded as a cause of death. In addition, they are costly, as management requires specialist equipment and dressings. Real costs are difficult to quantify, as costs also arise from the extra time that patients are hospitalized for what is an eminently preventable condition.

Risk factors for pressure ulcers

Several factors increase the risk of pressure ulcer development; these may be extrinsic (external to the patient, related to their environment) and intrinsic (directly about the patient).

Extrinsic factors

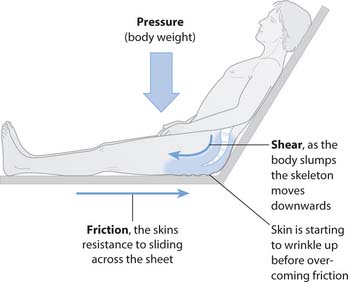

The extrinsic risk factors are (Fig. 25.7):

Fig. 25.7 Relationship between pressure, shear and friction

(reproduced with permission from Brooker & Nicol 2003)

The role of moisture is less clear. However, when moisture is trapped against the skin, the skin becomes macerated, thus increasing susceptibility to trauma, e.g. from nurses’/carers’ nails, rings, etc., and friction forces.

Intrinsic factors

Intrinsic factors are numerous and individual to the patient:

Pressure ulcer risk assessment tools

In order to identify which patients/clients may be at risk of developing a pressure ulcer, a risk assessment tool is used (Table 25.3, p. 718). Many such tools exist, e.g. Waterlow (see Fig. 14.3, p. 357), Braden, etc.

The tools are based on a list of risk factors, each of which is allocated a numerical score. The numbers are summed to reach a total which defines the patient’s level of risk, e.g. low, medium or high. Differences exist between the tools, perhaps the most crucial of which is the way the numbers relate to risk. In the Braden score, the lower the number, the higher the risk; however, in the majority of such tools, the higher the score, the higher the risk of developing a pressure ulcer. Each tool and its risk factors were designed for a particular area of care, e.g. the Walsall tool for use in the community. Therefore the risk factors in each tool vary to take account of the particular issues associated with either a speciality such as intensive care or a particular care setting such as community (Table 25.3).

Although risk assessment tools cannot replace clinical assessment, they do provide a structure for recording the factors which together determine whether the patient/client is ‘at risk’ or not. Once a level of risk has been identified, appropriate preventative actions are implemented (see pp. 718–719). For example, if sections are scored indicating that the patient has discoloured skin, the care plan should include regular repositioning, skin assessment and skin care. Evaluation of risk should be carried out on a regular basis determined by the patient’s overall condition; in acute care this will usually be at least weekly, but may be less frequent in a care home where the resident’s condition is stable (Box 25.9, p. 718). Assessment must be carried out if the patient’s condition changes (deterioration/improvement) and on transfer to another care setting.

Evaluating pressure ulcer risk

Which pressure ulcer risk assessment tool is used in your placement?

Student activities

[Resource: NHS Modernisation Agency 2003 Essence of care: patient-focused benchmarks for clinical governance. Online: www.modern.nhs.uk/home/key/docs/Essence%20of%20Care.pdf Available July 2006]

Pressure ulcer prevention

The prevention of pressure ulceration requires multidisciplinary working. The patient/client should, where necessary, have input from the appropriate health professional.

Repositioning

Where equipment is neither available nor suitable, it is still possible to prevent pressure damage by regular manual repositioning (see Ch. 18). Even when using specialist beds and mattresses, the patient should be regularly repositioned as this serves other functions, e.g. preventing sputum retention (see Ch. 17) and providing the patient with a changing view.

The skin should be examined at regular intervals and at every repositioning for the first signs of pressure damage (see below). Repositioning schedules should be tailored to the individual and should take account of when they may need to be in a particular position, e.g. sitting upright at mealtimes. While traditionally patients are repositioned from side to side and on their back, this increases the risk as they are being placed directly onto bony prominences. A more appropriate way of repositioning is to use the 30° tilt, where the patient’s weight is supported on areas of large muscle bulk such as the buttocks. If the patient/client can tolerate the prone position it should be considered, as it gives full pressure relief to the back and increases the number of positions available and therefore the body surface area used to distribute pressure.

Pressure-redistributing equipment

This may include any type of equipment that enables the patient/client to maintain their independence, e.g. specialist seating, electric bed frames, etc., but more commonly includes a wide range of pressure area care mattresses and seating. Pressure-redistributing equipment is available to help reduce susceptibility to pressure ulcers and it is important that an appropriate product is chosen to meet individual patient’s needs (Box 25.10). Particular problems may arise when supplying equipment for use at home, especially if the patient sleeps in a double bed with their partner. Very few pieces of equipment are designed for this situation, with most mattresses taking up more than half the bed, leaving the carer with insufficient sleeping space; however, some do exist and must be considered. Equally, there are far fewer products for use with infants and children; most mattresses fit a standard hospital bed.

Preventing pressure ulcers

Equipment must be provided for both bed and chair. Pressure ulcer prevention is required throughout the 24 hours, as when seated there is increased risk of pressure damage as the body weight is supported on a much smaller area.

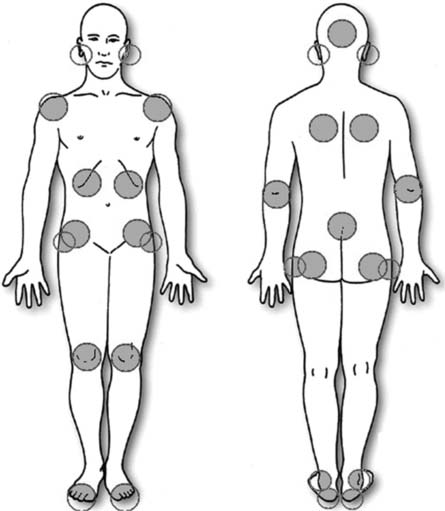

Skin assessment

Skin assessment is essential in preventing pressure damage. Key areas of the body are at greater risk of developing pressure damage because of an underlying bony prominence (Fig. 25.8, p. 720). These include the:

Fig. 25.8 Areas of the body most at risk from pressure damage

(reproduced with permission from the European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel)

The most common place for pressure ulcers is the sacrum (approximately 29%), with the heels as the second most common location (EPUAP 2002). There is, however, some variation; for example, in people who sit for long periods the ischial tuberosities are the most at-risk area. At-risk areas are different in babies whose head to bodyweight ratio differs from adults, making the head the most vulnerable area. Where pressure damage occurs over non-bony prominences it is usually caused by equipment, e.g. urinary catheter or oxygen mask/tubing (see Chs 17, 20).

Pressure ulcer grading

While it is estimated that 95% of all pressure ulcers are preventable, some people because of their poor general condition will develop one. Where a patient is admitted with existing pressure damage it is vital that this is clearly and comprehensively documented and, where possible, photographed.

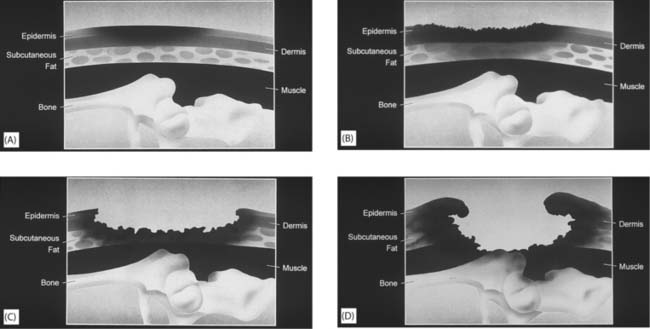

The extent of damage is usually described as the depth of tissue damage using a grading/classification system. Several grading tools exist, the most common of which are the Stirling grading tool (Reid & Morison 1994) and the EPUAP grading tool (EPUAP 1999) (Fig. 25.9, p. 720).

Fig. 25.9 EPUAP four-grade classification tool: A. Grade 1: non-blanchable erythema of intact skin. Discoloration of skin, warmth, oedema, induration (hardness) may also be used as indicators, particularly in people with darker skin. B. Grade 2: partial-thickness skin loss involving the epidermis or dermis, or both. The ulcer is superficial, which presents as an abrasion or blister. C. Grade 3: full-thickness skin loss involving damage to, or necrosis of, subcutaneous tissue that may extend down to, but not through, the underlying fascia. D. Grade 4: extensive destruction, tissue necrosis or damage to muscle, bone or supporting structures with or without full-thickness skin loss

(reproduced with permission from Huntleigh Healthcare)

Although the tools may appear straightforward, training is required to ensure reliability between users in describing the extent of damage. This is particularly so with the lesser degrees of damage where differentiating between blanching and non-blanching erythema (redness) may be difficult, and in people with darker skin. Blanching erythema is a patch of redness that resolves once the pressure is removed. Blanching refers to the test used to differentiate between this and persistent redness. Light finger pressure is applied to the reddened area. Where the microcirculation is intact the area blanches (whitens). However, if the microcirculation is damaged, the colour does not change. Non-blanching erythema is a prime warning sign of imminent skin breakdown.

Another difficulty arises when the area is covered with necrotic tissue. It is not possible to see the full extent of damage and so the area is classified as probably EPUAP grade 4. To assist with these difficulties, the EPUAP has recently proposed additional criteria for identifying the grade of damage and also to exclude damage due primarily to moisture (Defloor et al 2005). As the pressure ulcer heals, it is usual practice to refer to its original grade but designated as healing, e.g. healing grade 4.

The grading tools indicate the extent of the damage but provide little information about the appearance of the pressure ulcer and therefore cannot be used alone to set care objectives or to describe the wound. A thorough description should be supported by holistic wound assessment including a photograph (see pp. 708–712). Pressure ulcer management follows the wound care guidelines and dressing selection outlined above (see pp. 712–716) but with the additional objective of relieving pressure (Box 25.11).

Box 25.11  EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

Management of pressure ulcers

NICE (2003, 2005) has evidence-based guidelines which summarize the evidence supporting assessment and holistic management of pressure ulcers.

General findings and recommendations

Leg ulcers

Leg ulcers are a huge economic burden on NHS budgets. It is estimated that 1–2% of the UK population will experience a leg ulcer at some time, with the higher figure more likely in older people. Seventy percent of leg ulcers have a venous aetiology, arterial disease accounts for 8–10%, some have a mixed venous and arterial cause (10–15%) and others are secondary to other diseases (2–5%), (Günnewicht & Dunford 2004). As nurses in the community usually manage venous leg ulcers, the emphasis here is on the principles of managing venous leg ulcers. Readers requiring more information should consult Further reading suggestions (e.g. Morison et al 2006). The management of venous leg ulcers entails increasingly sophisticated care pathways involving the MDT and improved wound care products and bandaging techniques. Importantly, the impact of leg ulceration on quality of life is well recognized.

Causation of venous leg ulceration

It is important to understand how venous leg ulceration occurs in order to carry out assessment and make safe and effective clinical decisions.

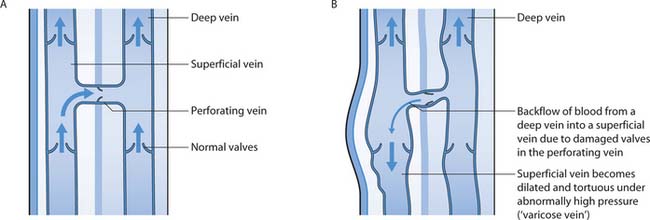

Blood returning to the heart in the leg veins is aided by the pressure changes occurring in the abdomen and thorax during respiration (‘respiratory pump’) and by muscle contraction in the lower limbs (‘calf muscle pump’). The legs contain deep (high pressure) veins and superficial (low pressure) veins connected by perforating veins (Fig. 25.10A). Some blood returns to the heart through superficial veins but most drains from the superficial to the deep veins through the perforating veins and on to the heart. The calf and foot ‘pumps’ squeeze blood along the veins. The lining of the limb veins is modified to form valves which allow flow in one direction only and normally prevent backflow and pooling of blood in the legs.

Fig. 25.10 A. Deep, superficial and perforating veins of the leg. B. Valve damage and backflow

(reproduced with permission from Bale & Jones 1997)

The valves can be damaged by trauma or surgery, and by deep vein thrombosis (DVT) (see Chs 17, 24). Once the valve is damaged, it malfunctions and backflow occurs (Fig. 25.10B). Backflow between the high and low pressure veins results in increased blood volume in the leg and increased pressure in the thin-walled superficial veins; this is called venous hypertension. Further stretching of the vein and valve occurs, and if backflow continues, signs and symptoms of venous insufficiency and ulceration develop.

Characteristics of venous ulceration

The physical characteristics and symptoms of venous ulceration are outlined in Box 25.12; Figure 25.11 shows a ‘typical’ venous ulcer. However, it is very important to remember that ulcer appearance can vary significantly and it is impossible to determine ulcer aetiology on appearance alone.

Box 25.12 Physical characteristics of venous ulceration

Specific assessment

Assessment and documentation are vital in identifying the factors contributing to the ulcer; knowledge of underlying aetiology leads to safer management decisions.

The physical characteristics outlined in Box 25.12 are associated with venous disease and are important to consider during assessment. Their presence indicates risk of ulceration through trauma, however trivial.

The assessment of a person with a leg ulcer must take account of factors influencing healing and general wound assessment, including description, wound measurement and photography, etc. (see pp. 708–712). In addition, specific factors include:

Once comprehensive knowledge is available, decisions can be made about further investigations that may be required. These include:

A vascular assessment using Doppler ultrasound is undertaken by an experienced nurse who has had specialist training to determine the type of ulcer involved.

Doppler ultrasound is used to determine the arterial blood flow to the lower limb. The blood pressure (BP) is measured in the arms and compared to the BP at the ankles. The comparison between the arm and the ankle pressures gives a ratio, or index – the ankle brachial pressure index (ABPI):

Ankle systolic BP/Brachial systolic BP = ABPI

For example, an ABPI of 1 means that 100% of blood is reaching the lower leg and there is unlikely to be arterial disease (unless the rest of the assessment indicates otherwise); an ABPI of 0.85 indicates that arterial disease exists and only 85% of blood is reaching the lower leg (Box 25.13). It is vitally important to exclude arterial disease before treating venous ulceration with compression therapy, which compresses both veins and arteries. If arterial disease is present, compression will further reduce tissue oxygenation, leading to serious limb damage, amputation or even death.

ABPI measurement

The district nurse visits Winnie at home to measure her ABPI as part of a holistic assessment of an ulcer on her right leg. Winnie’s ABPI measurement is:

Right leg 135/150 = 0.9 (indicates some problems with arterial blood supply)

Left leg 150/150 = 1.0 (indicates normal arterial blood supply)

The nurse explains the result, provides information and discusses the possible use of compression therapy with Winnie.

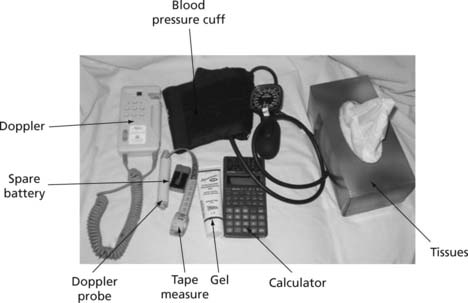

The equipment needed for ABPI measurement using a hand-held Doppler is shown in Figure 25.12.

Management of venous leg ulcers

The aim of management is, where possible, to restore valve function in the veins to allow ulcer healing. It is also to protect the skin from further damage and manage venous hypertension. This will include:

Box 25.14  EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

Reasons for non-concordance with compression therapy

In a small study, Edwards (2003) found 9that patients did not have a clear understanding of their condition or treatment regimens. Concurrent problems associated with compression bandaging adversely affected patients’ lifestyles and contributed to non-compliance. 9

Student activities

Think about a patient with a leg ulcer.

[Resource: Moffatt CJ 2004 Factors that affect concordance with compression therapy. Journal of Wound Care 13(7):291–294]

Compression therapy

Compression therapy is generally used for uncomplicated venous ulcers where the ABPI is >0.8. This can be applied by bandaging or compression hosiery once the ulcer is healed. A qualified nurse who has received additional training applies compression bandaging.

The veins are compressed to prevent/reduce backflow, thus reducing congestion in the leg and pressure in the superficial veins. Compression also enhances the action of the calf muscle pump, which squeezes the deep leg veins. The effects of this will be less oedema and increased comfort for the patient/client. Improvement in the circulation should allow the ulcer to heal and skin condition to improve. The precise pressures required to achieve these effects are unknown. Currently in the UK there is an approximate value of 40 mmHg; however, this will vary according to the circumference of the limb and the material used. The consensus is that some compression is better than none and it is what the patient/client will tolerate, the consistency in application and the wearing of compression bandaging/hosiery that really help healing.

Compression therapy must always include protection of the limb with a layer of padding. This helps to protect bony prominences such as the malleoli. The effectiveness of compression relies on a uniform pressure around the leg, with the pressure graduating from the ankle to the knee. The limb is not completely round so evenness can be difficult to achieve. Padding can help to distribute pressure evenly (Moffatt & Harper 1997).

The highest pressure is required at the ankle as it is furthest away from the heart with less pressure required at the knee. If the compression bandage is applied at an even pressure the shape of the limb (narrower at the ankle than the calf) ensures the pressure is graduated. If necessary, padding can be used to create a smaller ankle diameter in relation to the calf. The crucial point is that the application technique must be precise and consistent and always in accordance with manufacturer’s instructions; as these vary, it must be checked before application.

Reducing recurrence of venous leg ulcers

Skin care (see Ch. 16)

Student activity

Access the article by Brooks et al (2004) and consider how the findings could be used to improve concordance with one of the aspects listed above.

[Adapted from Flanagan & Fletcher (2003)]

[Resource: Brooks J, Ersser SJ, Lloyd A, Ryan TJ 2004 Nurse-led education sets out to improve patient concordance and prevent recurrence of leg ulcers. Journal of Wound Care 13(3):111–116]

Hosiery items are classified by the pressure they deliver: Class I (14–17 mmHg), Class II (18–24 mmHg) and Class III (25–35 mmHg) (Moffatt & Harper 1997). Class III can be difficult to apply even for relatively young and able people. It can be helpful to apply two stockings of a lower class to reach the desired pressure to make application easier. There are aids available to help with application but most have to be purchased by the patient.

| European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel | www.epuap.org |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Leg Ulcer Forum | www.legulcerforum.org |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Surgical Materials Testing | www.smtl.co.uk |

| Laboratory | Available July 2006 |

| Tissue Viability Nurses Association | www.tvna.org |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Wound Care Society | www.woundcaresociety.org |

| Available July 2006 |

Bale S, Jones V. Wound care nursing. A patient-centred approach. London: Baillière Tindall, 1997.

Bergastrom N, Braden BJ, Laguzza A, Holman V. The Braden scale for predicting pressure sore risk. Nursing Research. 1987;36(4):205-210.

Brooker C, Nicol M (eds) Nursing adults. The practice of caring. Mosby, Edinburgh

Chaloner DM, Franks PJ. Validity of the Walsall community pressure sore risk calculator. British Journal of Community Nursing. 2000;5(6):266-276.

Defloor T, Schoonhoven L, Fletcher J, et al. Statement of the European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. Pressure ulcer classification: differentiating between pressure ulcers and moisture lesions. Journal of Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nursing. 2005;32(5):302-306.

Edwards LM. Why patients do not comply with compression bandaging. British Journal of Nursing. 2003;12(11):S5-S16. Tissue Viability Supplement.

EPUAP. 1999 Pressure ulcer treatment guidelines. EPUAP, Oxford. Online: www.epuap.org/gltreatment.html.

EPUAP. 2002 Summary report on the prevalence of pressure ulcers. EPUAP Review 4(2). Online: www.epuap.org/review4_2/index.html.

EPUAP. Nutritional guidelines for pressure ulcer prevention and treatment. Oxford: EPUAP, 2003.

Flanagan M. Wound management. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1997.

Flanagan M, Fletcher J. Tissue viability: managing chronic wounds. In: Brooker C, Nicol M, editors. Nursing adults. The practice of caring. Edinburgh: Mosby, 2003.

Fletcher J. Exudate theory and the clinical management of exuding wounds. Professional Nurse. 2002;17(8):475-478.

Gosnell D. Pressure sore risk assessment: a critique. The Gosnell scale, Part 1. Decubitus. 1982;2(3):32-38.

Günnewicht B, Dunford C. Fundamental aspects of tissue viability nursing. London: Quay Books, 2004.

Keicolt-Glaser JK, Marucha PT, Malarkey WB, et al. Slowing of wound healing by psychological stress. Lancet. 1995;346(8984):1194-1196.

Leaper DJ, Harding KG, editors. Wounds: biology and management. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

McClemont E, Woodcock N, Oliver S, et al. The Lincoln experience – Part 1. Journal of Tissue Viability. 1992;2(4):114-118.

Moffatt C, Harper P. Leg ulcers. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1997.

Morison M, Moffatt C, Bridel-Nixon J, Bale S. Nursing management of chronic wounds, 2nd edn. London: Mosby, 1999.

National Institute for Clinical Excellence [now the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; NICE]. 2003 The use of pressure-relieving devices (beds mattresses and overlays) for the prevention of pressure ulcers in primary and secondary care. Online: www.nice.org.uk/pdf/PRD_Fullguideline.pdf.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). 2005 Pressure ulcers: the management of pressure ulcers in primary and secondary care. Online: www.nice.org.uk/page.aspx?o5CG029.

Norman D. The effects of age-related skin changes on wound healing rates. Journal of Wound Care. 2004;13(5):199-204.

Norton D. Calculating the risk. Reflections on the Norton scale. Decubitus. 1989;2(3):24-31.

Reid J, Morison M. Towards a consensus: classification of pressure sores. Journal of Wound Care. 1994;3(3):157-160.

Singhal A, Reis ED, Kerstein MD. Options for non-surgical debridement of necrotic wounds. Advances in Skin and Wound Care. 2001;14:96-103.

Thomas S, Jones M, Shutler S, Jones S. Using larvae in modern wound management. Journal of Wound Care. 1996;5(2):60-69.

Waterlow J. Pressure ulcer prevention manual. Taunton: Waterlow, 2005.

Williams C, Fonseca J 1993 Evaluation of the Medley Score. Part 1: the study plan. In: Proceedings of the 3rd European Conference on Advances in Wound Management, Harrogate 19–22 October.

World Union of Wound Healing Societies. Principles of best practice: minimising pain at wound dressing – related procedures. London: MEP, 2004.

Bale S, Jones V. Wound care nursing. A patient-centred approach, 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Mosby, 2006.

Morgan DA. 2004 Formulary of wound management products. 9th edn. Euromed Communications, Haslemere. Online: www.euromed.uk.com/formulary.htm.

Morison MJ, Ovington LG, Wilke K. Chronic wound care. A problem-based learning approach. Edinburgh: Mosby, 2004.

Morison MJ, Moffatt C, Franks P. Leg ulcers. A problem-based learning approach. Edinburgh: Mosby, 2006.

NHS Quality Improvement Scotland. 2005 Best practice statement: pressure ulcer prevention. Online: www.nhshealthquality.org./nhsqis/qis_display_home.jsp;jsessionid5D0C3FE2356207E2E980186B8D453C740?p_applic5CCC&p_service5Content.show&pContentID543.

REFLECTIVE PRACTICE

REFLECTIVE PRACTICE CRITICAL THINKING

CRITICAL THINKING NURSING SKILLS

NURSING SKILLS

ETHICAL ISSUES

ETHICAL ISSUES

HEALTH PROMOTION

HEALTH PROMOTION