Physical Health Problems of Adolescence

http://evolve.elsevier.com/wong/ncic

Behavioral Health Problems of Adolescence, Ch. 21

Disorders Affecting the Skin, Ch. 18

Genitalia (Examination), Ch. 6

Health Promotion of the Adolescent and Family, Ch. 19

Infection Control, Ch. 27

Precocious Puberty, Ch. 38

Common Health Concerns of Adolescence

![]() Adolescents are subject to the same skin conditions that affect the school-age child, such as bacterial, viral, and fungal infections; contact dermatitis; and drug reactions. However, one skin disorder, although not limited to the adolescent age-group, appears predominantly at this time: acne vulgaris (common acne). Acne is the most common skin problem treated by physicians. Acne involves important anatomic, physiologic, biochemical, genetic, immunologic, and psychologic factors.

Adolescents are subject to the same skin conditions that affect the school-age child, such as bacterial, viral, and fungal infections; contact dermatitis; and drug reactions. However, one skin disorder, although not limited to the adolescent age-group, appears predominantly at this time: acne vulgaris (common acne). Acne is the most common skin problem treated by physicians. Acne involves important anatomic, physiologic, biochemical, genetic, immunologic, and psychologic factors.

More than half the adolescent population will have had acne by the end of the teenage years, and many children have evidence of the disorder before age 10. Acne usually occurs in middle to late adolescence, at age 16 to 17 years in girls and 17 to 18 years in boys. The disorder is more common in boys than in girls. After this age period the disease usually decreases in severity, but it may persist well into adulthood. Early acne occurs in the midface region (midforehead, nose, and chin) and later spreads to the lateral cheeks, lower jaw, back, and chest. The degree to which acne affects an individual may range from nothing more than a few isolated comedones to a severe inflammatory reaction. Although the disease is self-limiting and is not life threatening, its significance to the affected adolescent is great, and it is a mistake to underestimate its impact on teens.

Etiology

Numerous factors affect the development and course of acne. Research has shown a familial aspect to acne vulgaris, with a high occurrence of severe acne and increased sebum secretion among monozygotic twins. Forty-five percent of adolescent boys with acne have a positive family history, whereas only 8% of adolescent boys without acne have a positive family history. Premenstrual flares of acne occur in nearly 70% of girls, suggesting a hormonal cause. Scientific studies do not demonstrate a clear association between stress and acne; however, adolescents commonly cite stress as a cause for acne outbreaks. Cosmetics containing lanolin, petrolatum, vegetable oils, lauryl alcohol, butylstearate, and oleic acid can increase comedone production. Exposure to oils in cooking grease can be a precursor to acne in adolescents working in fast-food restaurants. There is no known link between dietary intake and the development or worsening of acne lesions.

Pathophysiology

Acne is a disease that involves the pilosebaceous unit, which consists of the sebaceous glands and hair follicles. Acne is most commonly found on the face, chest, upper back, and neck because of the large quantity of sebaceous glands on these skin areas. There are nearly 900 glands per square centimeter on the skin surfaces of the face, chest, neck, and upper back, compared with 100 glands per square centimeter on the rest of the body.

Three pathophysiologic factors have the greatest influence on acne development: excessive sebum production, comedogenesis, and the overgrowth of Propionibacterium acnes (Olutunmbi, Paley, and English, 2008). Increased sebum production begins at the time of adrenocortical maturation and subtly continues to increase until the late teens. Acne severity is proportional to the sebum secretion rate, which is genetically determined.

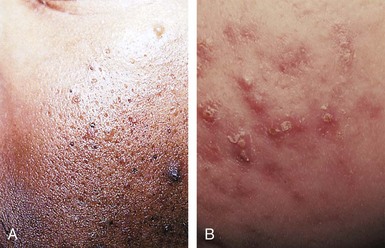

Comedogenesis (formation of comedones) results in a noninflammatory lesion that may be either an open comedone (blackhead) or a closed comedone (whitehead). Inflammation occurs with the proliferation of P. acnes, which draws in neutrophils, causing inflammatory papules, pustules, nodules, and cysts (Fig. 20-1). The traditional ice pick scarring results from macrophages that digest the inflamed skin along with the normal dermis in the process.

Psychosocial Ramifications

Adolescents are acutely aware of their physical appearance, and their cognitive development results in the feeling that they are constantly on stage. In one survey one third of teenagers reported that pimples were the first thing people noticed about them (Gupta and Gupta, 2003). A population-based study found that older adolescents with acne had lower self esteem, lower self-worth, and less body satisfaction than those without acne (Dalgard, Gieler, Holm, et al, 2008). The amount of psychologic stress does not directly correlate to the clinical severity of the acne. The importance of timely treatment has been underscored by research demonstrating the long-term psychologic impact of living with acne over critical developmental periods of life (Gupta and Gupta, 2003).

Therapeutic Management

Successful management of acne depends on a cooperative effort between the care provider, adolescent, and parents. The care provider must determine the adolescent’s goals and increase understanding of the cause and treatment of acne. Unlike many dermatologic conditions, the acne lesions resolve slowly, and improvement may not be apparent for at least 6 weeks. Individual comedones may take several weeks to months to resolve, and papules and pustules usually resolve in about 1 week.

The multifactorial causes of acne require a combined approach for successful treatment. Treatment consists of general measures of care and specific treatments determined by the type of lesions involved.

General Measures: The practitioner provides the adolescent with an overall explanation of the disease process, emphasizing the patient’s individual requirements. Parents should be present at the initial discussion to ensure their cooperation, understanding, and support. Remind adolescents that acne occurs, to some degree, in almost all teenagers.

Improvement of the adolescent’s overall health status is part of the general management. Adequate rest, moderate exercise, a well-balanced diet, reduction of emotional stress, and elimination of any foci of infection are all part of general health promotion. Review general skin care considerations, including limiting sun exposure and the use of noncomedogenic moisturizers and sunscreens.

Cleansing: Acne is not caused by dirt or oil on the surface of the skin. Gentle cleansing with a mild cleanser once or twice daily is usually sufficient. Antibacterial soaps are ineffective and may be drying when used in combination with topical acne medications. For some adolescents, hygiene of the hair and scalp appears to be related to the clinical activity of acne. Acne on the forehead may improve with brushing the hair away from the forehead and more frequent shampooing.

Medications

Treatment success depends on commitment from the adolescent. Before prescribing treatment, the clinician should determine the adolescent’s level of comfort and readiness to begin treatment. The teen should be reminded that clinical improvement may take weeks to months. Those who are impatient with speed of recovery may discontinue the medication or apply too much. Discussion about acne treatment should begin in early puberty. In young girls the early development of acne is the best predictor of future severe acne. Early intervention, most often with topical medications, may prevent the development of more severe acne.

Topical retinoids are the only drugs that effectively interrupt the abnormal follicular keratinization that produces microcomedones, the invisible precursors of the visible comedones. Retinoids are recommended as the first line of treatment for most forms of acne. Tretinoin has been the gold standard for topical retinoids and is available as a cream, gel, or liquid. The cream is less irritating than the gel, which is less irritating than the liquid. Newer formulations contain tretinoin trapped within porous copolymer microspheres that localize the medication to the follicle. These are less irritating to the skin because the medication is released over time, reducing the concentration on the skin (Guttman, 2009). The next-generation topical retinoids adapalene and tazarotene became available in the late 1990s. A comparison trial of the two medications found them to have similar efficacy, but adapalene gel 0.3% was better tolerated. After 12 weeks of treatment more than 50% of subjects in both treatment arms reported marked improvement or near clearing of acne (Thiboutot, Arsonnaud, and Pascale, 2008).

A gel combining 0.25% tretinoin and 1.2% clindamycin phosphate (Ziana gel) has been recently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). This gel has been shown to be more effective in treating acne than tretinoin or clindamycin monotherapy (Eichenfield and Wortzman, 2009).

Instruct the patient to begin with a pea-sized dot of medication, which is divided into the three main areas of the face and then gently rubbed into each area. The patient should not apply the medication until at least 20 to 30 minutes after washing to decrease the burning sensation. A daily moisturizer should be used along with retinoid treatment. Since sun exposure may easily result in severe sunburn, advise adolescents to avoid sun, apply the medication at night, and use a sunscreen with a sun protective factor (SPF) of at least 15 in the daytime.

Topical benzoyl peroxide is an antibacterial agent that inhibits the growth of P. acnes. Benzoyl peroxide is effective against both inflammatory and noninflammatory acne and is an effective first-line agent. The medication is available as a cream, lotion, gel, or wash. Using benzoyl peroxide is less likely to result in the development of antibiotic-resistant strains of P. acnes, which makes it an ideal adjunct when topical or oral antibiotic treatment is employed (Bowe and Shalita, 2008). Benzoyl peroxide soaps are convenient because they can be applied in the shower and assist in the treatment of acne on the chest and back. Benzoyl peroxide and salicylic acid are the most common ingredients in popular and effective acne treatment kits available over the counter. Patient education should include information regarding the bleaching effect of the peroxide on sheets, bedclothes, and towels. The adolescent can be reassured that skin bleaching will not occur. The drying effects of the medication can be accommodated with gradual increases in strength and frequency of application.

When inflammatory lesions accompany the comedones, a topical antibacterial agent may be prescribed. These agents are used to prevent new lesions and to treat preexisting acne. Clindamycin, erythromycin-metronidazole, and azelaic acid are currently available topical antibiotics. Side effects of these medications include erythema, dryness, and burning; using the medications every other day will decrease the adverse effects. Topical antimicrobials combined with benzoyl peroxide are more effective than either product alone. Retinoids in combination with antimicrobials also improve the penetration of these topical agents and are the only means to address three of the pathogenic causes of acne: keratinization, P. acnes, and inflammation. Combination therapy is usually more effective than either component alone (Krakowski, Stendardo, and Eichenfield, 2008).

Systemic antibiotic therapy is initiated when moderate to severe acne does not respond to topical treatments. The foundation for using systemic antibiotics in acne treatment has been the elimination of the inflammatory effects of P. acnes by suppressing the bacteria. Tetracycline, erythromycin, minocycline, doxycycline, and amoxicillin are systemic antibiotics used to treat acne (Olutunmbi, Paley, and English, 2008; Yan, 2006). They are relatively free of side effects with the exception of occasional gastrointestinal upset, photosensitivity, or vaginal candidiasis. Minocycline is more expensive but is less likely to cause gastrointestinal side effects and is very effective against severe inflammatory acne. Resistance to antibiotics may develop, especially with tetracycline and erythromycin. Judicious use of oral antibiotics and avoidance of topical antibiotics in combination with oral treatment can prevent resistance. Providers should avoid use of multiple antibiotic classes and shorten the course by using the full dose of systemic antibiotics for 1 month and then begin to taper the dosage. The adolescent can then be maintained on topical treatment (Krakowski, Stendardo, and Eichenfield, 2008).

Girls with mild to moderate acne may respond to topical treatment and the addition of an oral contraceptive pill (OCP). OCPs reduce the endogenous androgen production and decrease the bioavailability of the woman’s circulating androgens. Combination OCPs containing levonorgestrel, gestodene, and desogestrel as the progestin decrease acne in women. The FDA has approved multiple combination OCPs for the treatment of acne in girls. Visible improvement may take up to 4 months.

Isotretinoin 12-cis-retinoic acid (Accutane), a potent and effective oral agent, is reserved for severe, cystic acne that has not responded to other treatments. Isotretinoin is the only agent available that affects all factors in the development of acne. Only physicians who have taken a comprehensive educational program about the medication, necessary monitoring of patients, and parameters for pregnancy prevention may manage treatment with isotretinoin. Adolescents with multiple, active, deep dermal or subcutaneous cystic and nodular acne lesions are treated for 20 weeks. Long-term remissions occur with this highly effective drug. However, multiple cutaneous side effects can occur, which vary from mild to moderate in severity. Dry skin, dry eyes, dry mucous membranes, nasal irritation, decreased night vision, photosensitivity, arthralgia, headaches, mood changes, depression, and suicidal ideation may occur. There is some concern that isotretinoin may be associated with increased incidence of depression and suicide despite several findings to the contrary (Webster, 2009). Careful monitoring for signs of depression among all adolescents taking isotretinoin is recommended as part of all health visits for acne treatment (Hull and D’Arcy, 2003; Jacobs, Deutsch, and Brewer, 2001). The most significant side effects are the teratogenic effects, causing limb and skull abnormalities. Isotretinoin is absolutely contraindicated in pregnant women. Sexually active young women must use an effective contraceptive method during treatment and for 1 month after treatment. Providers should also monitor patients receiving isotretinoin for elevated cholesterol and triglyceride levels. Significant elevation may require discontinuation of the medication.

Scarring begins early in all types of acne, from papulopustular to nodulocystic. Most of the scarring is a result of loss of tissue rather than thickening. Chemical peels have been traditionally used for the treatment of scarring in acne. Only the mildest acne scarring will actually resolve with chemical peels. Fractional photothermolysis using laser technology is considered to be as effective as carbon dioxide lasers for treating acne scarring; some side effects are associated with carbon dioxide laser therapy (Chapas, Brightman, Sukai, et al, 2008; Walgrave, Ortiz, MacFalls, et al, 2009).

Nursing Care Management

The health screening interview should contain questions regarding the adolescent’s concern about acne. Because acne is so common and its appearance may seem so mild, the health care provider may underestimate the relative importance of the disease to the adolescent. The nurse should assess the individual adolescent’s level of distress, current management, and perceived success of any regimen before initiating a referral. If the adolescent does not perceive the acne to be a problem, he or she may lack motivation to follow the treatment plan. The primary care provider can manage most cases of acne without referral to a dermatologist.

The nurse can provide ongoing support for the adolescent when a treatment plan has been initiated. Encourage the family to support the adolescent in his or her efforts. Discuss the use of the medications and basic skin care information in detail with the adolescent. Written information to accompany the discussion is helpful. Inform patients that it will take 6 to 8 weeks to appreciate improvement in their skin. Information to dispel myths regarding the use of abrasive cleansing products as a means of removing blackheads can prevent unnecessary costs and trauma to the skin. Teenagers also need to be educated about factors that may aggravate acne and damage skin, such as too vigorous scrubbing. Picking, squeezing, and manual expression with fingernails breaks down ductal walls and causes acne to worsen. Mechanical irritation, such as vinyl helmet straps that rub areas predisposed to acne, can cause the development of lesions.

Vision Changes

Vision changes are common during the teenage years. The onset of refractory errors or worsening of previous errors peaks in adolescence as a result of the growth spurt. Other than myopia, new eye problems in this age-group are rare. Vision screening is usually performed in the school by nurses, and referrals are made as required to correct vision problems. The main goal is to detect new refractive errors. Adolescents with vision changes are referred for contacts or glasses as appropriate.

Health Problems of the Male Reproductive System

Common congenital anomalies of the penis are almost always detected and corrected in infancy or early childhood. In some cases boys who need an operative procedure to repair hypospadias (the most common congenital deformity of the penis) may reach adolescence with a penis that looks different from those of their friends. A few who have received no medical care have uncorrected deformities that can cause serious psychologic problems during this sensitive period of development. These young boys need to be identified for surgical repair of the defect.

Uncircumcised males may encounter some problems during adolescence related to a tight foreskin that cannot be retracted over the enlarging glans; some males may not cleanse the area properly. These boys are at risk for more frequent infections. Penile carcinoma is associated with human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 (HPV 16, 18). Although HPV is a common sexually transmitted infection (STI) among American males, penile carcinomas are rare in the United States and most Western countries.

Trauma to the penis, including burns and accidental injuries, can occur in various ways. The frenulum (the fold on the lower surface of the glans that connects it with the prepuce) can be torn after retraction of the foreskin, unusually rough masturbation, or coitus. It can be frightening to the young boy but usually heals spontaneously with minimum care. However, any extensive bleeding may require suturing of the tissues. Penile fracture is a rupture of the corpus cavernosum as a result of blunt trauma to the erect penis, usually during vigorous sexual intercourse or manipulation. The condition is considered a urological emergency, and surgical repair is recommended to prevent further complications (Al-Shaiji, Amann, and Brock, 2009; Maruschke, Lehr, and Hakenberg, 2008).

Drugs such as trazodone (Desyrel), taken alone or in combination with cocaine or Ecstasy (MDMA [3-4 methylenedioxymethamphetamine]), may cause a prolonged erection (priapism), which can be extremely uncomfortable and in some cases may require surgical intervention to release blood trapped in the corpus cavernosum. Drugs available to adults for erectile dysfunction or other drugs not intended for recreational uses may have unintentional and undesirable side effects (James and Mendelson, 2004).

Testicular Tumors

Tumors of the testes are not a common condition but are usually malignant when found in adolescence. Testicular carcinomas account for 7% of the malignancies that occur in 15- to 19-year-olds in the United States (Reaman and Bleyer, 2006). Testicular cancer is the most common solid tumor in males 15 to 34 years of age. The usual presenting symptom is a heavy, hard, painless mass that is palpable on the anterior or lateral aspect of a testis. The tumor may be smooth or nodular and does not transilluminate unless accompanied by a hydrocele. The involved testicle hangs lower and is therefore more susceptible to trauma. Although not all scrotal masses are malignant, any firm swelling of the testes demands immediate evaluation. If a firm swelling is noted, the adolescent should be evaluated by ultrasonography and immediately referred for direct biopsy if the mass is found to be solid.

Treatment for testicular cancer consists of surgical removal of the affected testicle (orchiectomy) and the adjacent lymph nodes if they are affected. If metastases are evident in more distant nodes or organs, chemotherapy and radiotherapy are implemented. (See Chapter 36.)

Nursing Care Management

To supplement routine health assessment, every adolescent boy should learn to perform monthly testicular self-examination (TSE). This provides an opportunity for the adolescent to familiarize himself with his own anatomy and to ensure early detection of any abnormality. In the TSE each testicle is examined individually, preferably after a warm bath or shower, when scrotal skin is more relaxed, using the thumbs and fingers of both hands and applying a small amount of firm, gentle pressure. The normal testicle is a firm organ with a smooth, egg-shaped contour. The epididymis can be palpated as a raised swelling on the superior aspect of the testicle and should not be confused with an abnormality. The nurse can play an important role in providing anticipatory guidance to all adolescent boys. This guidance includes an explanation of the rationale for TSE and how to perform this procedure (see Critical Thinking Exercise).

Varicocele

A varicocele is characterized by elongation, dilation, and tortuosity of the veins of the spermatic cord superior to the testicle. The finding is rare in prepubertal children, but the incidence increases dramatically at the onset of puberty. Idiopathic varicocele is the most common treatable cause of male-related impaired fertility, especially if caught and treated early (Zampieri, Mantovani, Ottolenghi, et al, 2009). Varicoceles occur most often on the left side because of the greater length of the left spermatic vein and its entry into the left renal artery; the right spermatic vein enters the vena cava directly and at a lesser angle, which may be a source of future difficulty. A varicocele can be palpated as a wormlike mass situated above the testicle that decreases in size when the male is recumbent and becomes distended and tense when he is upright. Some males may experience discomfort during sexual stimulation.

In pubertal boys the left testicle is usually larger than the right. However, when there is an associated varicocele, the left testicle is usually smaller than the right. Testicular size and levels of dihydrotestosterone in seminal plasma decrease with increasing duration of the varicocele. Varicocelectomy is indicated in adolescents when there is growth arrest of the affected testicle or when there is pain associated with the varicocele. Currently, improvement in testicular volume is the main outcome measure following varicocelectomy in children and adolescents. Several recent studies have shown significant catch-up growth after surgical treatment (Sakamoto, Ogawa, and Yoshida, 2008; Sakamoto, Saito, Ogawa, et al, 2008). Surgical repair of varicoceles in adult men is less successful than in children and adolescents. There is no statistical difference in catch-up growth postoperatively for males between 10 and 24 years of age (DeCastro, Shabsigh, Poon, et al, 2009). Whether there is a correlation between testicular catch-up growth and testicular function is still to be determined.

Epididymitis

Epididymitis is an inflammatory reaction of the epididymis of the testicle as a result of an infection (bacterial or viral), a chemical irritant (urine), or a nonspecific cause (local trauma). The clinical presentation is an insidious (slow) onset of unilateral scrotal pain, redness, and swelling. Associated symptoms include urethral discharge, dysuria, fever, and pyuria. Epididymitis is not associated with gastrointestinal symptoms as found in testicular torsion. The causative factor in males less than 35 years of age is thought to be predominantly Chlamydia trachomatis, although nearly 90% do not have laboratory evidence of the bacteria from urethral swab (Tracy, Steers, and Costabile, 2008). Mild presentation of symptoms may mimic testicular torsion, which requires immediate surgical intervention. Therefore immediate evaluation by a practitioner is indicated. Treatment consists of analgesics, scrotal support, bed rest, and appropriate antibiotic therapy. Conduct an assessment for other STIs, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), for adolescent males who test positive for chlamydia.

Testicular Torsion

Intravaginal torsion of the testicle is a condition in which the tunica vaginalis, which normally encases the testicle, fails to do so and the testis hangs free from its vascular structures. This condition can result in partial or complete venous occlusion with rotation around this vascular axis. In severe torsion the organ can become swollen and painful; the scrotum becomes red, warm, and edematous and appears to be immobile or fixed as a result of spasm of the cremasteric fibers.

Testicular torsion occurs in 1 in every 4000 males, with a peak onset at 13 years of age. Rapid growth and increasing vascularity of the testicle are thought to be precursors to torsion, accounting for the occurrence at puberty (Gatti and Murphy, 2008). Testicular torsion is the most common cause of testicular loss in young males (Adelman and Joffe, 2000; Mansbach, Forbes, and Peters, 2005). Typically, the adolescent complains of pain that was either acute or insidious in onset and that has radiated to the groin. Nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain may accompany the pain; the cremasteric reflex is often absent. Fever and urinary symptoms are generally not present. The history often reveals that similar painful episodes have occurred previously, resolving spontaneously. Emergency surgery is often necessary to preserve the testicle.

Nursing Care Management

Nurses should be alert to the possibility of testicular torsion in adolescents who complain of scrotal pain. Because torsion often results from trauma to the scrotum, school nurses are likely to encounter such injuries and should refer the adolescent for medical evaluation immediately.

Gynecomastia

Some degree of bilateral or unilateral breast enlargement occurs frequently in young boys during puberty. Approximately half of adolescent boys have transient gynecomastia, which usually lasts less than 1 year. When gynecomastia has a prepubertal onset, the adolescent should be evaluated for rare adrenal or gonadal tumors, liver disease, or Klinefelter syndrome. Gynecomastia may also be drug induced; calcium channel blockers, cancer chemotherapeutic agents, histamine2-receptor blockers, and oral ketoconazoles have all been shown to cause the disorder. Some report that marijuana causes gynecomastia.

If gynecomastia persists or is extensive enough to cause embarrassment, plastic surgery is indicated for cosmetic and psychologic reasons. Administration of testosterone has no effect on breast development or regression and may even aggravate the condition.

Health Problems of the Female Reproductive System

Whether it is her first experience or one of many, adolescent girls are often apprehensive before a pelvic examination. Adolescents are self-conscious about their bodies and the changes taking place. The adolescent needs anticipatory guidance regarding what to expect and what she can do to help herself relax during the procedure. Many fears and apprehensions are a result of information she has obtained from family members and friends. The discussion should begin by addressing these anxieties.

The ideal time to begin preparing a girl for examination of the genitalia is as she is entering puberty. External genitalia examination should always be included as part of a routine physical assessment; excluding the genitalia reinforces the attitude that sexuality is something to be avoided.

The timing of the initial pelvic examination is controversial; the ultimate decision depends on the adolescent and the health care provider. Indications for a pelvic examination during adolescence are listed in Box 20-1. The advent of effective urine based STI tests has added to the controversy, since assessment for many STIs can be done without the use of the speculum.

The pelvic examination provides an excellent opportunity for teaching about hygiene, body functions, and sexuality. Encourage the girl to ask questions about changes in her body and the implications. The pelvic examination also allows an opportunity to discuss practicing safer sex, preventing STIs, and postponing sexual involvement. Lack of knowledge is a factor in risky sexual experimentation in adolescence.

The pelvic examination should be as nonstressful as possible. Nurses should attempt to make the initial pelvic examination a positive experience for the adolescent, since this can increase the likelihood of compliance with annual visits. The teenager should have the option of choosing a supportive person to be present during the examination. Suggested individuals might include a parent, best friend, boyfriend, or other health professional. The use of models and drawings and a display of equipment to be used facilitate understanding. Allowing the adolescent to handle the speculum may help decrease some of the fear. The adolescent is given the choice of wearing a gown or her own clothing during the examination. A description of the examination, including information about the procedure and words that describe anticipated feelings and sensations experienced during the examination, may reduce anxiety. Of major concern to the adolescent is fear of discovery of a pathologic pelvic condition. Reassurance regarding normal physical findings is extremely important.

Most girls favor a semisitting position, which has the additional advantage of allowing eye contact during the procedure. Sometimes a pillow helps the patient feel more comfortable and less vulnerable. The provision of a mirror for the girl to see what is taking place if she so desires helps the examiner explain various aspects of anatomy. When possible, it is important to respect the adolescent’s request for a female provider.

Numerous techniques have been described to teach women to relax during a pelvic examination, including breathing exercises, imagery, and other strategies for reducing stress. (See Pain Management, Chapter 7.) However, these techniques are not effective with all individuals. When the examination is finished, the provider discusses the findings with the adolescent and makes referrals if indicated. Written materials are useful educational materials.

Menstrual Disorders

The mean age of menarche in the United States is 12.55 years for non-Hispanic Caucasian, 12.06 for African-American, and 12.25 for Mexican-American girls, with 80% of girls beginning between 11 and 13.75 years of age (Chumlea, Schubert, Roche, et al, 2003). Pubertal development proceeds in a predictable sequence and tempo. When evaluating an adolescent with amenorrhea, the nurse requires an accurate history of the timing of development of secondary sexual characteristics. Primary amenorrhea is defined as no menses by age 15. An evaluation is necessary at age 13 if the girl has no secondary sexual characteristics or if menarche does not follow within 3 years of the onset of secondary sexual characteristics. Secondary amenorrhea is no menses for 6 months in a previously menstruating female when pregnancy has been excluded. Secondary amenorrhea is much more common than primary amenorrhea.

It is not unusual for an adolescent to have irregular menses when establishing ovulatory cycles. This is a result of an immature hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis. In general, the later menarche occurs, the longer the period of anovulation. Two thirds of adolescent girls establish regular menstrual cycles by 2 years after menarche. Oligomenorrhea (abnormally light or infrequent menstruation) early after menarche is not uncommon. After a careful examination to rule out any physical abnormalities, including signs of androgen excess and congenital defects of the genital tract, the young girl and parent can be given reassurance with no additional evaluation.

Amenorrhea

The causes of amenorrhea can be divided into organ system and estrogen status. The most common cause of amenorrhea is pregnancy. A pregnancy test is an essential part of the evaluation for all females with amenorrhea, regardless of the sexual history. The next most prevalent causes of amenorrhea in adolescents are polycystic ovary syndrome and hypothalamic amenorrhea. For girls who are more than 2 or 3 years past menarche, the most common hypothalamic causes of amenorrhea are eating disorders, excessive exercise, medication, and stress (Wiksten-Almstromer, Hirschberg, and Hagenfeldt, 2007).

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a common endocrine disorder. There are no formal diagnostic criteria for teens with PCOS, and the cause is unclear. The characteristic findings are hyperandrogenism, chronic anovulation, and polycystic ovaries. Other ovarian causes of amenorrhea include gonadal dysgenesis; the most common form is Turner syndrome. Girls with Turner syndrome have delayed puberty, short stature, webbed neck, widely spaced nipples, and cardiac and kidney abnormalities. Premature ovarian failure, galactosemia, and ovarian tumor are other ovarian causes of amenorrhea.

Thyroid disease is not uncommon in adolescents and is more common in females than males. Both hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism may result in menstrual irregularities, with the latter more likely to cause amenorrhea.

Adrenal causes of amenorrhea include congenital adrenal hyperplasia, which is an autosomal recessive disorder of steroidogenesis. Nonclassic adrenal hyperplasia is characterized in adolescents by hirsutism or amenorrhea. Pituitary causes of amenorrhea include prolactinoma, Cushing syndrome, and sarcoidosis.

Primary amenorrhea in an adolescent complaining of periodic (usually monthly) lower abdominal pain with evidence of estrogen production and sexual maturation may be related to an imperforate hymen, closed hymen from female circumcision, or transverse vaginal septum. The treatment is simple surgical perforation and drainage. Other anatomic causes of the amenorrhea include intrauterine adhesions and congenital absence of a uterus.

Menstrual Irregularities in the Female Athlete

The most common clinical indications of potentially adverse effects of exercise on an adolescent’s reproductive cycle include (1) delayed menarche, (2) anovulation associated with dysfunctional uterine bleeding, and (3) oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea with hypoestrogenic states. Researchers have not been able to identify the exact mechanism of these menstrual changes. The most probable cause is at the hypothalamic level as a result of an imbalance of the amount of energy in (food) compared to the energy out (exercise). Amenorrhea is so common among female athletes that it is misinterpreted as normal by athletes, coaches, and some health care providers. Prevalence of amenorrhea has been found to be as high as 69% among ballet dancers and 65% among distance runners. Eating disorders are often part of the syndrome with exercise-induced amenorrhea (Warren and Chua, 2008). Adolescents who exercise intensely and have menstrual bleeding more frequently than every 21 days or at intervals of 35 to 120 days are likely to have chronic anovulation. They usually produce estrogen but have inadequate levels of progesterone. Unopposed estrogen can lead to endometrial hyperplasia and theoretic risk of endometrial adenocarcinoma.

In addition to menstrual dysfunction, female athletes also may be at risk for eating disorders and decreased bone mineral density (Joy, Van Hala, and Cooper, 2009). Any adolescent athlete who becomes amenorrheic requires medical evaluation to rule out other causes of amenorrhea and to assess for disordered eating (Sherman and Thompson, 2004). Sometimes a trial of decreasing the intensity or duration of exercise and improving nutrition will relieve irregularities. Careful evaluation by a health care provider who specializes in the treatment of eating disorders and athletes is essential. (See Chapter 39.)

Dysmenorrhea

Dysmenorrhea is defined as painful menstrual flow. Primary dysmenorrhea is painful menses without any identifiable pathologic disorder. Primary dysmenorrhea is the most common cause of painful menses in adolescents. Secondary dysmenorrhea is defined as painful menses with a pathologic condition such as endometriosis, salpingitis, or congenital anomalies of the müllerian system. The incidence of dysmenorrhea increases as adolescents mature; at age 12 years the prevalence is reported at 38%, and it increases to 66% to 77% by age 17 (Slap, 2003). It is a leading cause of recurrent absence from work and school.

Etiology: The factor present in all instances of primary dysmenorrhea is the onset of ovulatory cycles. Although it is not invariable, the symptoms do not occur during the first few postmenarchal months or during months of irregular anovulatory menses. After the progesterone withdrawal before menstruation, prostaglandins and leukotrienes are released in the uterus, causing an inflammatory response. This response is the cause of cramping and the systemic symptoms of nausea, vomiting, bloating, and headaches. Levels of prostaglandins are higher in the menstrual fluid of women with dysmenorrhea (Harel, 2008).

Clinical Manifestations: Typical complaints of the adolescent with dysmenorrhea are lower abdominal cramping and pain or discomfort. About 50% of girls also have systemic symptoms, including nausea and vomiting, fatigue, nervousness, diarrhea, and headache. The pain usually begins several hours before the appearance of visible vaginal bleeding, is most severe on the first day of menstruation, and may last from a few hours to a day or more but seldom exceeds 2 or 3 days. The symptoms and degree of discomfort vary considerably from one individual to another and from one period to another in the same female. The pain may be only a mild, fleeting discomfort or so severe as to be incapacitating, requiring absence from school. After adolescence the menstrual discomfort decreases with age, and it may resolve completely after childbirth.

Therapeutic Management: A careful history, including a menstrual and sexual history, is necessary. In addition, a careful review of gastrointestinal and genitourinary systems is necessary to rule out problems. A thorough gynecologic examination is carried out to exclude any pelvic abnormalities. The pelvic examination may not be indicated in an adolescent who is not sexually active and who responds to medical therapy.

The treatment of choice for adolescents is the administration of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). These drugs block the formation of prostaglandins, leading to a reduction in uterine activity and prevention of pain. Antiprostaglandins are taken for only 2 or 3 days of the menstrual cycle. Prophylactic use of NSAIDs has proved effective when begun a few days before the onset of the menses, approximately 11 days after ovulation. The relief appears to be a result of prostaglandin inhibition rather than analgesic effect.

A variety of drugs that are taken at the onset of symptoms are available without prescription, such as ibuprofen and naproxen. The fenamates have the additional benefit of antagonizing the action of already-formed prostaglandins. If NSAIDs are unsuccessful in relieving the pain or if the adolescent desires contraception, cyclic estrogen therapy to prevent ovulation can provide dramatic and predictable relief from pain. Oral contraceptives are effective in approximately 90% of cases.

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, which reduces the perception of pain, has been an effective nonpharmacologic source of relief of pain associated with dysmenorrhea but less effective than NSAIDs. Insufficient evidence is available to prove whether acupuncture is effective. Small clinical studies have demonstrated positive effects, but randomized, placebo-controlled trials are needed (Yang, Liu, Chen, et al, 2008). Exercise is widely believed to alleviate dysmenorrhea by improving pelvic blood flow and stimulating the release of β-endorphins, which have an analgesic effect.

Nursing Considerations: The nurse may be the person to whom a young woman turns for advice regarding menstrual problems. The nurse should provide anticipatory guidance concerning menstrual physiology and hygiene and the importance of a well-balanced diet, exercise, and general health maintenance. Adolescents need information regarding availability of effective treatment for dysmenorrhea. Only about 50% of females with dysmenorrhea take medication to relieve the symptoms, even though effective treatment is available. The nurse should review correct dosing, since many adolescents use subtherapeutic doses of medication. Timing of the onset of the treatment requires the use of a menstrual calendar.

Most of the prostaglandin inhibitors are available without prescription. Whatever drug the adolescent chooses, she needs to be told how the drug produces its effect, how to take the drug for maximum effect, and the side effects. The drug should be taken with food and a full glass of water. If no satisfactory relief is achieved, refer the adolescent for further evaluation.

Endometriosis

Dysmenorrhea that is not substantially relieved within 6 months of taking OCPs and NSAIDs requires an evaluation with laparoscopy to rule out endometriosis. The disease is much more common in adolescents than was previously thought, with incidence rates ranging from 47% to 67% (Templeman, 2009).

Endometriosis is defined as the presence of endometrial glands and stroma outside the normal intrauterine endometrial cavity. The etiology is still unclear; risk factors include early menarche and late menopause. Research now suggests there is a genetic component to the etiology. The use of OCPs is protective and decreases the risk of endometriosis for up to 1 year after the method is discontinued. The presentation of endometriosis is variable, but women with surgical diagnosis of endometriosis are more likely to have dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, and menorrhagia. In addition, women with endometriosis are likely to have subfertility or infertility (Ballard, Seaman, de Vries, et al, 2008).

Treatment is medical, surgical, or a combination. The goal of treatment is pain control and suppression of the disease. The patient and family need to understand that the recurrence rate is high and that currently no cure is available for the disease.

Premenstrual Syndrome

Although premenstrual syndrome (PMS) was first described in 1931, after several decades of research it remains poorly defined. The natural history of PMS is not known. It has more than 200 reported symptoms, and, with no confirmatory laboratory test, providers are hesitant to initiate treatment (Braverman, 2007). Research about PMS in adolescents is sparse; pharmacologic treatment trials have not included adolescent subjects. The symptoms are stable across cycles, occur regularly in the late luteal phase, and resolve within days of onset of menstrual bleeding. The manifestations most frequently cited are irritability, mood swings, headache, anxiety, and depression with the physical complaints of bloating, fatigue, and breast tenderness.

PMS is very common, occurring at some point in most women’s reproductive lives. When specific diagnostic criteria are used, about 30% of women are significantly affected by moderate to severe symptoms. Only 5% to 8% of women meet the criteria for premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) (Rapkin and Mikacich, 2008). PMDD is characterized by symptoms of marked and persistent anger, irritability, mood swings, anxiety, and affective lability sufficient to cause significant impairment in one’s ability to function occupationally or socially during the week preceding menses (Vigod, Ross, and Steiner, 2009).

Accurate diagnosis of PMS requires a thorough history and careful physical examination to exclude other medical or psychiatric conditions. A daily report form enables the young woman to pinpoint symptoms, which allows for monitoring during treatment. The diagnosis is made when at least one disabling physical or psychologic symptom is present up to 2 weeks before menses with remission when the menstrual flow begins (Rapkin and Mikacich, 2008). Currently, few well-controlled studies demonstrate effective treatment. Treatment options vary depending on the type and severity of symptoms.

Nutritional supplements have long been recommended as a treatment for PMS. Supplementation with 1200 mg/day of calcium and vitamin D has been demonstrated to reduce water retention, food craving, and pain (Bertone-Johnson, Hankinson, Bendich, et al, 2005). There is no clear evidence that dietary supplements such as vitamin B6, primrose oil, or multivitamins are effective in the treatment of PMS. High-intensity aerobic exercise improves symptoms of PMS in adult studies.

An OCP containing a new progestin called drospirenone in a regimen of 24 active and four inactive pills has been demonstrated to be effective in the treatment of PMDD (Rapkin and Mikacich, 2008). Case reports have shown that adolescents with PMDD respond well to fluoxetine given in the luteal phase (Hetrick, Merry, McKenzie, et al, 2007).

The nurse can provide information regarding direct-care measures, adequate rest, good nutrition, and regular exercise. Families often have questions about the myriad treatment options available. The nurse can provide information about current recommended therapies. The nurse can teach patients to cope with the psychosocial aspect of the syndrome through stress reduction techniques, counseling, and support groups.

Dysfunctional Uterine Bleeding

Dysfunctional uterine bleeding (DUB) is abnormal vaginal bleeding that occurs in the absence of pregnancy, infection, neoplasms, or any other demonstrable pathologic condition or disease. DUB is usually associated with anovulation and is the most frequent urgent gynecologic problem for adolescents. During adolescence, abnormalities in the menstrual flow’s timing (intervals of <20 or >40 days), length (>8 days’ duration), and amount (>80 ml) can occur frequently. This irregularity is usually attributed to immaturity of the positive feedback mechanism between the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis and absence of the luteinizing hormone surge late in the menstrual cycle. The result is anovulatory cycles in which the production of estrogen is unopposed because of a lack of progesterone. The effect of the estrogen is an increase in the thickness of the endometrial lining without structural integrity. Without progesterone, menstrual flow is not limited. Not all anovulatory females have DUB. One contributing factor is the amount of endogenous estrogen.

A comprehensive health history and physical examination, including a pelvic examination, are indicated to ascertain the cause of bleeding. The initial assessment should include the amount of blood loss and the possible need for hospitalization. Common causes of vaginal bleeding need to be ruled out before the diagnosis of DUB can be established. The most common reason for vaginal bleeding in adolescence is pregnancy. Other causes of vaginal bleeding can be related to anatomic anomalies, foreign bodies, endocrine disease, STIs, chronic illness, or previously undetected familial bleeding disorders (e.g., von Willebrand disease).

Treatment of vaginal bleeding depends on determination of the underlying mechanism. The initial management depends on the amount of blood lost and the patient’s symptoms. If the bleeding is infrequent and not associated with anemia, reassurance and a menstrual calendar for follow-up monitoring are often sufficient.

When moderate anemia occurs, hormonal therapy, in the form of OCPs or cyclic medroxyprogesterone, has been beneficial. The adolescent needs to know that, at completion of the recommended regimen, a heavy flow with cramping will probably occur for 3 or 4 days. Without this information, she may believe that her condition is worse and assume that the treatment was ineffective. Untreated patients are at increased risk for endometrial hyperplasia and adenocarcinoma from the persistent, unopposed estrogen stimulation of the endometrium. The OCPs are continued for several months, after which bleeding irregularities seldom recur. DUB may persist for up to 2 years in more than half the cases.

Dilation and curettage may be necessary to control hemorrhage in severe cases or in those that do not respond to more conservative management. Supplemental iron is sometimes needed to correct anemia. Normally menstruating females average a loss of 1 mg of iron daily; thus blood loss of more than 80 ml/month is a significant risk factor for the development of iron deficiency anemia and signifies the need for oral iron therapy (Ferrara, Coppola, Coppola, et al, 2006).

Nursing Care Management

Ordinarily, only reassurance and attention to general health status are needed, with emphasis on a well-balanced diet, adequate rest, and moderate exercise. The nurse should instruct the adolescent to use a menstrual calendar to track improvement and guide future interventions. When OCPs are prescribed, the adolescent and her parents need careful explanation of the use of these medications. The high-dose estrogen OCPs can result in nausea and vomiting. Anticipatory supportive care includes preparation for procedures if these are a possibility.

Vaginitis and Vulvitis (Vulvovaginitis)

A small quantity of vaginal mucus is normal and in adolescent girls usually increases at the time of ovulation and before the onset of menstruation. It is characteristically clear and, except in rare instances when it appears in large amounts, causes no discomfort. However, some teenagers mistakenly believe that the discharge is a sign of vaginal infection. After an examination the girl can generally be reassured and given anticipatory guidance about hygiene and the increased secretions associated with sexual excitement.

Leukorrhea is the term used to describe a glutinous, gray-white discharge, which can be caused by physical, chemical, or infectious agents. Physical causes include foreign bodies such as a forgotten tampon. Irritation from pinworms, bubble bath, douching, deodorant pads or tampons, or improper wiping after defecation can also cause leukorrhea. The resulting discharge may be purulent, blood tinged, or brown with an offensive odor. Removal of the offending material is usually all that is necessary.

The normal vaginal flora is predominantly composed of Lactobacillus acidophilus, which produces lactic acid and hydrogen peroxide to maintain an acidic environment. Vaginitis occurs when pathogens or changes in the environment disrupt this balance. Oral antibiotics, oral and vaginal contraceptive agents, sexual intercourse, douching, and stress may allow pathogen proliferation and the development of vaginitis.

Vulvovaginal candidiasis results when Candida organisms begin to proliferate, resulting in overgrowth and infection. The most common organism is Candida albicans, accounting for 80% to 90% of infections; Candida glabrata occurs in 10% to 20% of cases. Susceptibility to candidiasis can be increased by a number of factors, including estrogen status, presence of glycogen, and the loss of protective bacterial flora from broad-spectrum antibiotics. A small percentage of women have recurrent yeast infections, four or more episodes in a year, and would benefit from culture identification of the Candida species. The nurse should be alert to risk factors for HIV, since recurrent or persistent vulvovaginal candidiasis may be the first symptom of the infection.

The adolescent with vulvovaginal candidiasis generally has vaginal pruritus and sometimes dysuria. The presence of the classic thick “cottage cheese–like” discharge is seen in a minority of patients. Most females have a minimum amount of an uncharacteristic discharge. The diagnosis is easy to confirm with microscopic evaluation.

First-line treatment of candidiasis remains the administration of over-the-counter topical antifungal drugs. The medications are available in cream, lotion, suppository, and tablet formulations. Shorter treatment regimens are associated with increased compliance; those with recurrence may benefit from a longer course (7 to 14 days). Oral 1-day treatment regimens are safe and as effective as topical treatments but may result in more systemic side effects. Treatment of the male partner in sexually active adolescents is not necessary unless the glans penis is inflamed. The adolescent should be advised to expect decreased symptoms in 24 to 72 hours and complete resolution in 6 to 8 days, regardless of treatment type.

Trichomonas vaginalis is an anaerobic parasitic protozoan involved in 20% to 30% of all cases of vaginitis. It is the most prevalent nonviral STI in adolescents. The infection was once considered a nuisance infection but is now recognized to play a role in several poor health outcomes. Females with T. vaginalis are more likely to acquire HIV, herpes, and pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). Infection with T. vaginalis doubles the risk of persistent HPV infection in women and increases the shedding of HIV among both men and women with HIV infection (Pattullo, Griffeth, Ding, et al, 2009).

The infection is often asymptomatic and self-limiting in men. Women may be asymptomatic, but many have a vaginal discharge and vulvovaginal soreness. Dysuria and an odor may accompany the symptoms. T. vaginalis diagnosis has traditionally been made by microscopic visualization of the motile trichomonads from a vaginal wet mount specimen. This has low sensitivity depending on the clinician’s skills with microscopy and the length of time from specimen collection to observation. Culture is the gold standard but is expensive, is not widely available, and requires 4 days for a final reading. More commercially available tests for T. vaginalis are now offered; these are more sensitive than wet prep and less costly than culture.

Metronidazole or tinidazole is used for the treatment of T. vaginalis, in either a 2-g single dose or 500 mg twice daily for 7 days. Single-dose treatment is ideal in the adolescent population. Tinidazole has fewer gastrointestinal side effects than metronidazole. Sexual partners should also be treated and should abstain from sexual intercourse until 7 days after treatment is completed.

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is a common vaginal infection in young women. The infection is noninflammatory and caused by an overgrowth of a variety of organisms. The symptoms include a thin, homogeneous, malodorous vaginal discharge. Providers commonly use the Amsel criteria for the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis. It requires three out of four positive findings: homogeneous thin, gray vaginal discharge; pH more than 4.5; more than 20% clue cells on wet mount; and a positive Whiff test (fishy odor after application of potassium hydroxide). BV is associated with abnormal Papanicolaou (Pap) smears, PID, premature rupture of membranes, preterm labor, and postoperative infections. BV is not an STI; however, sexual transmission occurs as a result of disruption of normal vaginal flora. Other associated factors are smoking, oral receptive sex, and douching.

Treatment is recommended only for symptomatic women or those undergoing gynecologic surgery or abortion. The most effective treatment is metronidazole, 500 mg twice daily for 7 days, or as an intravaginal preparation for 5 days. Single-dose therapy is not recommended. Treatment of the male sexual partner is not necessary. Instruct the adolescent to abstain from sexual intercourse while taking the medication. Recurrence of BV is not uncommon.

Nursing Care Management

The adolescent who comes in for treatment of a vaginal discharge provides an opportunity for health teaching. Teach the young woman how to differentiate normal vaginal discharge from a potential infection. The discussion may elicit questions and concerns the adolescent has regarding other aspects of her developing body and sexuality. The nurse should stress the importance of an evaluation whenever the adolescent notices a change in her normal vaginal discharge.

When an infection is identified, the nurse can explain how the etiologic agents produced the irritation and the principles behind management. The prescription of a vaginal cream requires a careful explanation and demonstration of use. Girls who have never used a tampon will be less familiar with insertion of the vaginal applicator. Instruct the adolescent to apply the cream before bedtime to avoid leakage of the medication while in an upright position. The use of oil-based vaginal creams may break down the latex condom.

Health teaching should include the prevention of future infections. Teach girls at an early age to wipe front to back after toileting. Avoiding tight fitting clothes and nylon panties can assist in prevention. Douching is a common practice among adolescents and should be discouraged because it leads to changes in the normal vaginal microflora. Also, stress the use of condoms for prevention of T. vaginalis and other STIs.

Health Problems Related to Sexuality

The biologic maturation that forms the foundation of adolescent development and the transition to adulthood is accompanied by conflicting feelings, attitudes, and social practices related to developing sexuality. During adolescence the sexual drive emerges, and adolescents begin to explore their ability to attract a partner. The physical urges often precede emotional maturity.

The Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention conducts a national school-based survey to monitor key health-risk behaviors among youth. The 2007 survey results found that 47.8% of students had had sexual intercourse, with 7.1% having their first sexual encounter before the age of 13. Not all young people who have ever had sexual intercourse are currently sexually active; in this survey 35% of the students had sexual intercourse with at least one person during the 3 months before the survey. Among those students, 61.5% used a condom during the last sexual intercourse (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008).

The causes of adolescent sexual risk taking are multifactorial. There is great social pressure to experiment with sex, and enticements by the media to enhance physical attractiveness conflict with traditional religious and societal expectations for chastity. Easy access to cars, unsupervised time at home, and changing family composition also contribute to the incidence of sexual experimentation among the adolescent population. Egocentrism and the concept of the personal fable (feelings of omnipotence, invulnerability, and immortality) lead to risk taking and experimentation. Past research has found that low self-esteem in females was associated with intercourse at an early age; more recent studies have reported similar findings for adolescent males (Spencer, Zimet, Aalsma, et al, 2002; Laflin, Wang, and Barry, 2008).

Family influences can delay the initiation of sexual activity. Adolescents who have at least one warm, supportive parent engage in less risky behavior. Effective parent-child communication about sexual topics can delay the onset of sexual intercourse. In addition, supervision of the adolescent’s social activities and peer group, frequently referred to as parental monitoring, has consistently been shown to postpone sexual involvement. However, parents often underestimate the level of risk for their child and may not provide the appropriate monitoring and communication to assist in postponing sexual involvement (O’Donnell, Stueve, Duran, et al, 2008).

The social environment also has an effect on sexual risk-taking behavior. Adolescents who attend schools where they feel connected and involved in the programming are more likely to postpone sexual involvement. Youth with high academic achievement are more likely to postpone sexual involvement as well (Laflin, Wang, and Barry, 2008). Community support, resources, and supervision will also decrease risk taking among adolescents. Current data suggest that personal and perceived peer norms about sexual intercourse, condom use, and oral sex along with the use of alcohol and other drugs are strong predictors of initiation of sexual intercourse among adolescents (Santelli, Kaiser, Hirsch, et al, 2004; Potard, Courtois, and Rusch, 2008).

Prevention strategies must be comprehensive to decrease high-risk sexual behaviors. Delaying sexual intercourse, using condoms, choosing partners carefully, limiting sexual partners, and using reliable contraception help to reduce the impact of sexual activity on the adolescent. Nurses working with individual adolescents benefit from taking a sexual history so that prevention strategies are appropriate for the level of risk. Questioning adolescents who have not initiated sexual intercourse about their intention to initiate it is helpful, since their intentions are positively associated with actual sexual initiation in boys and girls (Gray, Austin, Huang, et al, 2008). Instruction in the skills needed to resist sexual intercourse has a stronger influence on reducing sexual activity than simply providing information on acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) or birth control methods.

Adolescent Pregnancy

In recent years the teenage pregnancy rate has shown a continual downward trend. Between 1990 and 2004, birth rates for teenagers 15 to 19 years of age declined nationally for all races and Hispanic-origin populations. The rates for younger teens have declined more than the rate for older teens (Ventura, Abma, Mosher, et al, 2008). However, adolescent birth rates still remain high in the United States compared with those in other developed countries (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2005).

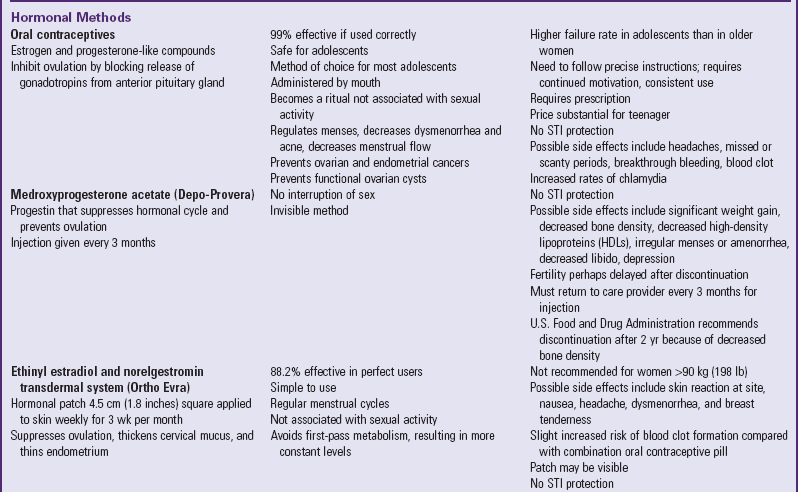

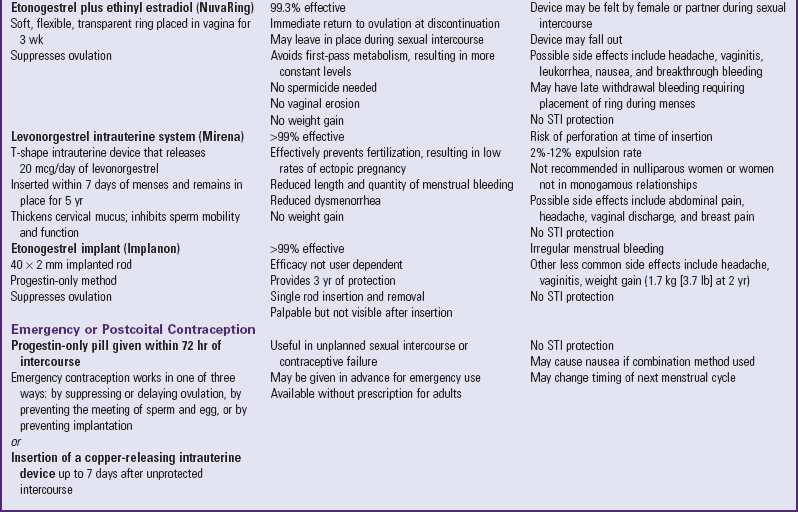

Contraception use among adolescents is variable, with decisions made within the context of the relationship. The less familiar an adolescent is with his or her partner, the less likely it is that they will use contraception during intercourse. Contraception use increases among girls as the duration of the relationship increases. A hormonal method (OCPs, contraceptive patch, injectable progesterone) is more likely to be used in later relationships than in first sexual relationships. Discontinuation of contraception is common; 46% of women have discontinued at least one method because of dissatisfaction (Moreau, Cleland, and Trussell, 2007).

In most cases, with early prenatal care, teenage pregnancy is no longer considered to be biologically disadvantageous to the child. However, teenage parenting is still regarded as socially, educationally, psychologically, and economically disadvantageous to both mother and child. Poverty is often the result of teenage childbearing (Aquilino and Bragadottir, 2000). African-American and Hispanic adolescents were more likely to become pregnant than their Caucasian counterparts. Eighty-two percent of all teenage pregnancies are unplanned (Alan Guttmacher Institute, 2006). Many of these social risk factors can be improved if a second pregnancy is prevented during the adolescent years or if the second pregnancy does not occur until 26 months postpartum. Other predictors of maternal success include participation in a program for pregnant teens, a social support system, and a sense of control over one’s life (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2001).

Medical Aspects

Adolescents often receive delayed or inadequate prenatal care. Prenatal care may be delayed because the adolescent does not realize she is pregnant or denies the pregnancy until the second or third trimester. Health care providers working with adolescents should have a high index of suspicion for pregnancy. She may or may not have considered the possibility of pregnancy no matter how at risk for pregnancy she is. A pregnant adolescent may give vague reports of irregular periods or missed periods; the bleeding that occurs with implantation may be mistaken for a period, further delaying the diagnosis. Lacking adequate care, adolescent mothers and their unborn infants are at greater risk for low-birth-weight infants and infant deaths. It remains unclear whether this is a result of biologic immaturity or sociodemographic factors.

The obstetric risk and risk to the infant during a second pregnancy for the teenager is much higher. An adolescent with a poor outcome in the first pregnancy has a threefold risk of repeating the poor outcome in the second pregnancy. In teenagers the risk for a preterm delivery recurring is double the rate found in mature women. However, the mean birth weight for second deliveries is higher, related to an increase in the maternal prepregnancy body mass index (BMI).

Diagnosis of Pregnancy

A detailed menstrual and sexual history should be a routine part of health care for adolescents. Review specific symptoms of pregnancy, including amenorrhea, breast tenderness, urinary frequency, fatigue, and nausea. Absence of these symptoms does not exclude pregnancy. It is best not to perform a pregnancy test without the adolescent’s knowledge. Before the pregnancy test, discuss with the adolescent what she will do if the test is positive and determine who else is aware she is sexually active and possibly pregnant.

After confirming that a pregnancy test is positive, inform the adolescent privately. Common reactions are ambivalence, shock, fear, or apparent apathy. The nurse should be supportive at this time and assure her the feelings are normal. Review the facts about the pregnancy, including the duration of pregnancy and anticipated due date. The next step is to determine who she plans to inform and, if she is under 18, how she would like to tell her parents. Some girls may want to take some time before notifying their parent. The nurse should schedule a follow-up appointment in 24 to 48 hours to assist with parental notification. Usually, the adolescent informs her parent on her own terms during this period. The nurse can assist with notification by offering to tell the parent for the teen or to be present when she tells her parent. Nonjudgmental support is critical at this time for the safety of the teen and her pregnancy.

Complications of Pregnancy

Bleeding is common in early pregnancy (occurring in 20% to 25% of cases), and about half of these pregnancies end in spontaneous abortion. Most spontaneous abortions occur in the first trimester as a result of abnormal chromosomal complement, uterine or cervical abnormalities, maternal systemic illness, or infection. Ultrasound evaluation can assist in determining the prognosis for the pregnancy. Bed rest is usually recommended when bleeding occurs; however, there is little evidence to demonstrate its effectiveness in preventing spontaneous abortions (Sotiriadis, Papatheodorou, and Makrydimas, 2004).

When a young woman is seen with bleeding and abdominal pain, an ectopic pregnancy must be ruled out. Ectopic pregnancy occurs when the fertilized egg implants outside of the uterus, usually in the fallopian tube. Damage to the fallopian tube is the most frequent cause of ectopic pregnancy. This damage occurs as a result of tubal surgery, PID, and previous ectopic pregnancy. Smoking is another risk factor for ectopic pregnancy; however, the mechanism is not known (Vichnin, 2008). When ectopic pregnancy is suspected, prompt evaluation and treatment are necessary. If the adolescent is seen with hypotension and abdominal pain, the ectopic pregnancy may have ruptured and emergency surgery is indicated.

Structural Factors: Labor may be prolonged in younger teenagers, particularly those 12 to 16 years of age; this is directly related to fetopelvic incompatibility and is a reflection of the teenager’s smaller stature and incomplete growth process. The incidence of prolonged labor is highest in girls younger than age 14. Girls who are 12 to 13 years old have the highest rate of cesarean births, primarily because of cephalopelvic disproportion. However, older adolescents, 15 to 21 years of age, and especially those who have previously delivered a baby, often have labors that are shorter than average. The transition between pelvic disproportion and pelvic adequacy appears to occur around 15 years of age in the average adolescent.

Nutritional Needs: Caloric requirements during adolescence closely parallel the growth curve, and the need for protein, calcium, and iron is increased. Young adolescents tolerate caloric restriction poorly, and the anabolic need for calories during pregnancy places an added burden on their bodies. The preconception weight is a major determinant of birth weight for infants born to adolescents. Weight gain recommendations for pregnant girls should be based on their weight-for-height percentile or BMI, not on their age. Primiparous adolescents are more likely than first time adult pregnant women to gain more than 18 kg (40 lb). Excessive weight gain during pregnancy is associated with labor and delivery complications, preterm labor, maternal anemia, and infant mortality. Excessive weight gain during pregnancy is also linked with postpartum obesity and the associated health risks (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2009). Recommended weight gain in pregnancy varies according to the woman’s prepregnancy BMI; a higher weight gain is recommended for thin women and a lower weight gain for women who are overweight or obese (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2009).

Because of the marked variation in the dietary needs of individual teenagers, there are no hard-and-fast rules to describe an adequate diet for all pregnant girls. The diet must provide sufficient nutrients to meet growth needs of both the prospective mother and the unborn child without the threat of excessive weight gain or fetal malnutrition. An additional 340 kcal/day (second trimester) to 452/day kcal (third trimester) are recommended for nutritional intake (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2009). The best guides for determining nutritional needs for the adolescent and pregnant adolescent are the Recommended Dietary Allowances and the Dietary Guidelines for Americans; the dietary reference intakes (DRIs) from the Institute of Medicine include recommended intakes of vitamins, minerals, and macronutrients for women of all ages and for those who are pregnant.* (See also Nutritional Assessment, Chapter 6.) Pregnant teenagers exhibit food preferences, eating behaviors, and lifestyle habits that are similar to those of their nonpregnant peers. Frequent snacking on foods high in fat and sugar and low in essential nutrients results in less than the recommended intake of calcium; iron; zinc; folic acid; and vitamins B6, A, and C—nutrients of special concern during pregnancy.

Social and Economic Aspects

Poor school performance usually precedes adolescent pregnancy. Unable to achieve academically, the girl views motherhood as a rite of passage into adult status. Adolescents with high educational expectations are less likely than others to become pregnant. Another significant aspect of school dropout and accelerated maturity is the girl’s alienation and isolation from her peers during a stage of development when identity formation is closely allied with peer identification. She is deprived of the interrelationship with the adolescent social system that is so essential to the development of a sense of identity. The girl may believe that she no longer “belongs” to the peer group and does not qualify for membership in the older peer group of mothers. On the other hand, the pregnancy may give the adolescent an entrance into a peer group. One study found that absenteeism and dropout rates were lower when adolescents received prenatal care in a school-based health center in an alternative school. Programs such as this can help reduce the long-term negative outcomes of adolescent parenting (Barnet, Arroyo, Devoe, et al, 2004).

Mother-Infant Relationship

Adolescents often have unrealistic expectations for the child. The young mother may view the infant as a plaything or a love object for herself. Children of adolescent mothers experience more developmental problems than children of adult mothers. The amount of cognitive stimulation in the child’s early home environment is associated with the child’s level of cognitive attainment. Many children of adolescents are raised by a grandparent. Although living with a grandparent may have positive effects on child outcomes, coresidence with the grandmother may have negative effects if the mother and grandmother are in conflict. Nurses need to stress the importance of the adolescent caring for the child even when other adults (e.g., mother or grandmother) are involved. The other adults present need education and support to allow optimum development of the infant and adolescent mother.

Several factors influence the mother-infant relationship. Maternal stresses, including changes in circumstances, influence coping ability and sensitivity to the infant’s needs. Teenage mothers may consider an argument with a parent, boyfriend, or husband stressful, whereas adult mothers focus on problems directly involving the infant. Vocational and educational disadvantages of both teenage mothers and fathers further affect their coping abilities. It is important to recognize that not all adolescent mothers are alike. Some teenagers adjust well to the stresses and responsibilities of parenting, whereas others may lack the maturity or confidence to nurture optimally.

When socioeconomic status is controlled for, it has been found that younger adolescent mothers have lower acceptance of their children compared with older adolescent mothers. Studies in the literature indicate that specific family variables, including the mother’s age (<19 years), are risk indicators for child abuse and neglect (Lounds, Borkowski, and Whitman, 2006; Murray, Baker, and Lewin, 2000).

A positive correlation exists between the total amount of social support and the frequency of appropriate maternal behavior. An assessment of whom the adolescent thinks she receives the most support from (her family, her partner, his family, or a close friend) allows the nurse to help the young mother benefit from this support (see Family-Centered Care box).

The cognitive development of the adolescent influences the development of attitudes and realistic expectations regarding childbearing. To cope effectively and solve situational dilemmas, pregnant teenagers must be able to use the problem-solving approach to assess and evaluate consequences. The concrete thought and egocentrism of early adolescence can influence the mother’s ability to evaluate the infant’s needs. Adolescent mothers lack knowledge of normal infant growth and development. This deficit may directly affect their perception, interpretation, and responsiveness to infant cues.

Infant characteristics also influence parental behavior. Teenage parents view their children as more temperamentally difficult than do adult parents. Temperamentally difficult infants have an adverse effect on the parents’ sensitivity and responsiveness. Parent-infant interaction that is not mutually satisfying can also alter the parents’ feelings of effectiveness and self-worth.

Adolescent Fathers

Little information is available about adolescent fathers. Most studies have small sample sizes and rely on reporting from the mother rather than the young man himself. Most teen fathers are involved with and interested in their children (Savio Beers, and Hollo, 2009). This involvement has positive effects on the mother’s self-esteem and decreases her level of distress and depression. The teen mother and her mother largely influence the level of participation a teen father has with his children. Social supports and parenting classes are often lacking for adolescent fathers. The nurse should take advantage of opportunities to involve young fathers in educational programs.

Nursing Care Management

It is evident from the preceding discussion that nurses play a central role in meeting the needs of pregnant teenagers. The nurse may be the one to whom the young girl turns for help and guidance in her dilemma and on whom she relies for support and reassurance.

The first goal in nursing care of the pregnant teenager is to help her obtain health care whether she elects to continue or terminate the pregnancy. Typically, adolescents are reluctant to seek medical help, in part because of anxiety but more often because of a tendency to deny the pregnancy. Early prenatal care is essential for the welfare of both mother and infant. For guidelines, teaching, and general support measures during pregnancy, the reader is directed to the excellent textbooks available on nursing care throughout the maternity cycle.

Basic to the implementation of any care program is communication and the establishment of a trusting relationship. Initially the adolescent may appear apathetic and display little interest in discussing her pregnancy. The nurse must make every effort to put the adolescent at ease and avoid undue pressure. The young girl may have encountered rejection and open criticism from authority figures and peers. Conveying a nonjudgmental and genuine caring acceptance of the adolescent and her goals will assist the nurse in gaining the adolescent’s confidence and trust.