CHAPTER 46 Persons with Neurologic and Sensory Deficits

Describe fundamental characteristics of the more common neurologic disorders, including dysfunctions of the motor system, peripheral neuropathies, spinal cord dysfunctions, demyelinating disorders, seizures, higher cortical function disorders, vascular insufficiencies, and sensory disorders.

Describe fundamental characteristics of the more common neurologic disorders, including dysfunctions of the motor system, peripheral neuropathies, spinal cord dysfunctions, demyelinating disorders, seizures, higher cortical function disorders, vascular insufficiencies, and sensory disorders. Describe the oral clinical findings frequently observed in clients with the more common neurologic deficits.

Describe the oral clinical findings frequently observed in clients with the more common neurologic deficits.The nervous system makes each individual unique. It senses and evaluates the internal and external environment, controls one’s body, and is responsible for one’s abilities, intellect, and personality. These characteristics are the result of complex interactions within the nervous system, and any structural damage or physiologic change to a component of this system may cause functional loss and a variety of neurologic deficits. Persons with neurologic disorders present unique challenges for the clinician to deliver comprehensive dental hygiene care. The dental hygienist must be knowledgeable about the specific condition, its oral clinical findings, the special considerations for dental hygiene care, and oral self-care instructions.

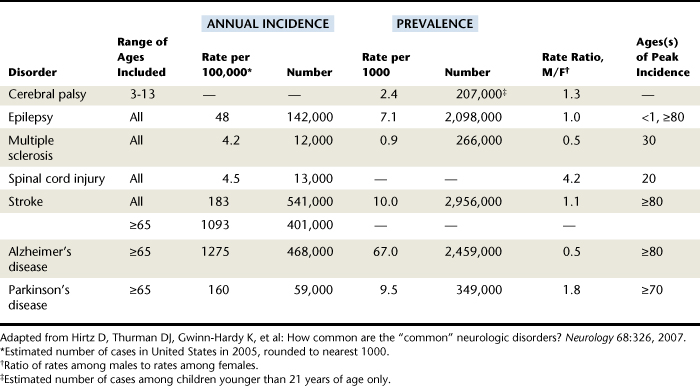

The incidence and prevalence of some of the more common neurologic diseases or conditions are listed in Table 46-1.

GENERAL DESCRIPTIONS OF DENTAL HYGIENE CARE

Although each neurologic deficit has a unique cause and pathology, the clinical manifestations may be similar. In these situations the oral clinical findings, special dental hygiene care considerations, and oral self-care instructions would also be similar and therefore are described first in general terms. The more specific descriptions, unique to a particular neurologic disorder, are discussed in the section on that disorder.

Oral Clinical Findings

Many clients with neurologic deficits exhibit extensive plaque biofilm accumulations, food debris, supragingival and subgingival calculus, dental caries, and gingival inflammation, possibly extending to the periodontal attachment. The major factor contributing to this poor oral health is the clients’ inability to perform adequate self-care because of impaired motor coordination, inadequate sensation, or generalized muscle weakness and fatigue. Further debilitation may necessitate dependence on the caregiver, who may be overwhelmed with the number of responsibilities. Access to care may be an additional problem because of limited finances, problems with mobility or transportation to dental care, and the attitudes of oral healthcare practitioners (see Chapter 41). Because of the neurologic deficit, the client may be receiving constant medical attention involving multiple medical appointments. With so many healthcare appointments, professional oral health maintenance may be less of a priority.

Moreover, oral musculature disturbances, observed in many of these clients, interfere with the self-cleansing mechanisms of the tongue, cheek, and lip and consequently the oral clearance of plaque biofilm and food debris. In addition, the client may have lost sensation and may not be aware of the debris collecting in the vestibule. Biofilm and food debris retention around the teeth and oral mucosa is accentuated by the consumption of a soft, carbohydrate-rich diet, which the client chooses because of problems with mastication and swallowing.

Client medications also may cause oral effects, the most common being xerostomia or dry mouth. Xerostomia in turn causes susceptibility to oral infections such as candidiasis, taste dysfunction, difficulty in swallowing, and dental caries.

Dental Hygiene Care Special Considerations

Frequent dental hygiene care appointments are usually needed to achieve and maintain optimal oral health, especially in clients whose neurologic deficit may limit their ability to perform oral self-care. Frequent dental hygiene visits are useful to monitor oral health and hygiene and to reinforce preventive self-care procedures for both client and caregiver. Weakness and fatigue increase during the day, so appointments are usually best scheduled early in the morning. Sufficient appointment time needs to be allowed so that the client does not feel rushed, in terms of both communication and physical movements. Also, the dental hygienist may need to provide the client with breaks from treatment.

Clients may be ambulatory but using assistive walking devices or may be confined to a wheelchair. Their needs for assistance will vary. Certain clients will do better without assistance because they have developed their own coping mechanisms; others will need aid in seating and rising from the dental chair or in being transferred to and from the wheelchair. Wheelchair transfer techniques are described in Chapter 41. Depending on the client’s condition, some may be more easily treated in the wheelchair.

During the appointment, clients with swallowing difficulty and a diminished gag reflex may need to be seated in a more upright position to avoid choking and aspiration of water and foreign substances. Optimal suctioning and limiting the amount of water also help prevent airway obstruction. Mouth props or bite blocks may be useful for clients with impaired oral reflexes, muscle weakness, and tremors and for those easily fatigued; however, extended use of these devices may create problems with the temporomandibular joint. Instrument fulcrums may need additional stabilization. To prevent clinician injury from the client’s mouth closing without warning, a finger guard, such as a metal tailor’s thimble secured with floss, may be helpful.

In many clients, maintenance of body stability is a great concern. The client may need to be secured in the dental chair with restraint or support devices, such as soft ties, belts, or pillows. Moreover, the use of the client’s caregiver to hold the client often is the best, least restrictive means. The use of assistance should always be explained to the client and/or caregiver as being facilitative for treatment, rather than restraint. The client’s head can be supported by the clinician sitting or standing at the 12-o’clock position and cradling the client’s head with the clinician’s nondominant arm. Further suggestions for stabilization are described in Chapter 41.

Oral Self-Care Instructions

Instructions for individualized self-care depend on the client’s level of energy and motor coordination (i.e., hand strength, abilities to grasp and to manipulate a toothbrush). It is important to encourage all clients to be as self-sufficient as possible in maintaining their own oral health. The client’s capabilities should be assessed so that devices may be recommended or created to compensate for physical limitations. Toothbrush handles with a larger diameter are easier to grip. Toothbrush can be enlarged with a bicycle grip, rubber or sponge ball, or modeling clay (see Chapter 41). Power toothbrushes usually have larger handles and do not require the client to produce a brushing stroke; however, supporting and controlling the weight of a power brush may be more difficult than holding a manual toothbrush with both hands. Clients may need to prop their elbows and arms during brushing to maintain motor control and minimize fatigue. For the client who wears dentures, a denture brush secured to the sink by suction would facilitate cleaning the prosthesis with one hand (see Chapter 55 for denture care).

Other adaptations to assist with plaque control are pump dispensers for toothpaste, toothpaste tubes with flip-top caps, and floss holders. Dental floss use may be too difficult to master, so another interdental aid may be more appropriate. Respiratory problems may contraindicate a foamy toothpaste, so a brand without the detergent sodium lauryl sulfate may be suggested. Only clients with adequate ability to control gagging and swallowing can safely use fluoride and chlorhexidine rinses at home. Those with severe oral motor dysfunction may be harmed by ingesting those products, so alternate preventive procedures, such as brush-on fluoride gels and fluoride trays, may be suggested.

Clients with mastication and swallowing difficulties may be consuming soft, carbohydrate-rich foods, so noncariogenic and nutritious foods should be recommended. The discomforts from xerostomia may be alleviated by the use of saliva substitutes (see Chapter 44). Fluoride mouth rinses and brush-on gels may also be recommended to xerostomic clients to prevent dental caries, especially root caries, which are prevalent in this population. Because alcohol might dry out the oral mucosa, alcohol-containing mouth rinses are relative contraindications for clients with low saliva production.

For clients requiring assistance with their self-care, their caregivers need to be instructed in effective plaque-control procedures (see Chapters 21, 22, and 41), as well as client positioning for maximal stability and access. The parent or caregiver may need to sit or stand behind the person or wheelchair. For the client with uncontrollable movements, a second person may be needed to stabilize the client.

Power toothbrushes may be easier for caregivers to use. Also, the use of a floss holder allows one hand of the caregiver to prop the mouth open while the other hand is grasping the floss holder. If a mouth prop is necessary to keep the mouth open, an inexpensive one can be made by securing five or six tongue depressors together with adhesive tape. Written as well as oral instructions need to be provided to both the caregiver and client so the information can be reviewed at home.

DYSFUNCTIONS OF THE MOTOR SYSTEM

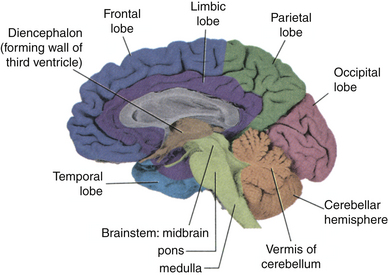

Motor actions require the integration of several central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS) components. The CNS is composed of the brain and the spinal cord (Table 46-2), and the PNS is composed of the spinal, cranial, and autonomic nerves and ganglia. Several brain regions are involved in voluntary movement control and in motor responses to sensory stimuli, particularly the motor region (frontal lobe) of the cerebral cortex, the cerebellum, and the basal ganglia. The outline of the CNS in Table 46-2 and the diagram of the brain in Figure 46-1 demonstrate the relationship of these specific regions to other components of the CNS. The basal ganglia are clusters of neuron cell bodies (gray matter) embedded deep within the CNS forebrain and midbrain. Although not evident in Figure 46-1, the basal ganglia are diagrammatically represented in Figure 46-2.

TABLE 46-2 Overview of the Major Subdivisions of the Central Nervous System

| Structure | Primary Function(s) |

|---|---|

| Brain | |

| Cerebral Hemispheres | |

| Lobes | |

| Frontal lobe | Voluntary motor control, including speech |

| Parietal lobe | Somatic sensations |

| Occipital lobe | Vision |

| Temporal lobe | Hearing, memory |

| Limbic lobe | Drives, emotions, memory |

| Basal ganglia | Motor control |

| Diencephalon | |

| Thalamus | Reciprocal connections with cerebral cortex |

| Hypothalamus | Integrative control of autonomic functions |

| Subthalamus | Motor control |

| Cerebellum | Control of range and force of movement and acquisition of motor skills |

| Brainstem | |

| Midbrain | Control of motor and sensory functions; substantia nigra |

| Pons | Motor relay from hemispheres to cerebellum |

| Medulla | Control of vital autonomic functions |

| Spinal cord | Integration of sensory and motor information from body and control of body movements |

Figure 46-1 Major regions of the brain, as observed in a midsagittal view. Lobes of the cerebral cortex, diencephalon, brainstem, and cerebellum are illustrated; the regions of the basal ganglia are not evident in this view.

(Adapted from Nolte J: The human brain, ed 6, Philadelphia, 2009, Mosby.)

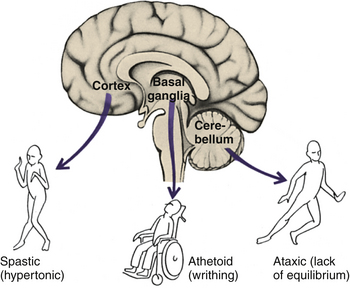

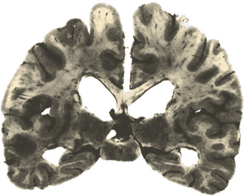

Figure 46-2 Parts of the brain affected in the major types of cerebral palsy. The types of the movement disorders depend on the part of the brain that has been damaged.

(Adapted from Nowak AJ: Dentistry for the handicapped patient, St Louis, 1976, Mosby.)

Disorders affecting cells of the cerebellum and basal ganglia, which project to the motor regions of the cerebral cortex, disturb movements and produce abnormalities of muscle tone, abnormal posturing, and tremors. There may be hyperkinesis (increase in movement), hypokinesis (lessening of muscular movement), a decrease in associated movements (e.g., arm swing when walking), or abnormal involuntary movements. Degenerative, metabolic, or vascular diseases; toxins; infections; trauma; or neoplasms may cause these abnormalities.

Parkinson’s Disease

Parkinson’s disease (Parkinson’s syndrome, paralysis agitans) is a chronic progressive disorder of the motor system. It is rather common in middle and old age, with the peak of onset in the sixth decade. Several conditions may present a clinical picture similar to that of Parkinson’s disease (e.g., reaction to certain drugs), but the most common type has an unknown cause. The incidence is higher among Caucasians than African Americans and Asians.

Characteristics

Pathologically the disorder is characterized by the progressive loss of dopamine-synthesizing neurons in the substantia nigra of the midbrain of the brainstem (see Figure 46-1). Dopamine is released from axons that originate from the cell bodies in the substantia nigra and terminate in the basal ganglia, where it serves as a neurotransmitter. A deficiency of dopamine at this site interferes with the conduction of nerve impulses related to muscle activity.

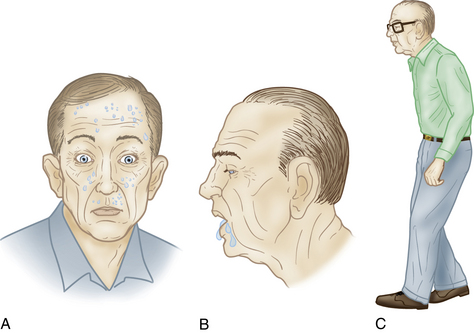

The cardinal manifestations of Parkinson’s disease are rigidity, akinesia (impaired muscle movement), and tremor, although tremor absence does not exclude the diagnosis of the disease. Muscle rigidity is felt in all passive movements. Akinesia or bradykinesia (movement slowness) leads to an expressionless face, infrequent blinking, and posture and gait disturbances, such as the characteristic rapid, short, shuffling steps (Figure 46-3). Other symptoms include a soft, barely audible voice, pitch monotony, and progressive difficulty with writing, which is often extremely small. The tremor is rhythmic, is seen at rest, usually involves primarily the hands, and has been given the name pill-rolling tremor. The tremor usually stops during intended movements.

Figure 46-3 Characteristic features of Parkinson’s disease. A, Expressionless face. B, Drooling. C, Stooped posture and gait with short, shuffling steps.

(From Little JW, Falace DA, Miller CS, Rhodus NL: Dental management of the medically compromised patient, ed 7, St Louis, 2008, Mosby.)

Patients often have great difficulty rising from a sitting position and trying to turn from one side to the other in the recumbent position. Patients usually stand in a slightly stooped posture with the arms flexed. When attempting to walk, they may have great difficulty getting started, and when they finally succeed, steps are short and arm swing is decreased or absent. When patients turn, the normal fluid movements become replaced by turning the body as a whole, and patients may have difficulty stopping immediately. Depression is common, and dementia is sometimes present.

Treatment and Prognosis

Usually patients progressively deteriorate over the course of the disease. Most efficacious treatment is dopamine replacement in the CNS through the use of levodopa, which is converted to dopamine. Most patients significantly improve on levodopa therapy, although there is some debate over when to use it. Because of its unpleasant peripheral side effects (e.g., nausea, vomiting, low blood pressure), other medications are also prescribed.

Oral Clinical Findings

One of the first noticeable signs of Parkinson’s disease is a lack of facial expression and animation, also known as “masked face.” The characteristic tremors also occur in the tongue, lips, and neck. Common manifestations are the “fly-catcher” tongue, tongue thrusting, and lip pursing. In the later stages of the disease, the muscles used in swallowing may work less efficiently, causing dysphagia (impaired swallowing) and drooling. Food and saliva may collect in the mouth and the back of the throat, which can cause choking and drooling. On the other hand, xerostomia often results from medications. Some clients experience a pulsating, burning pain involving the anterior tongue, hard palate, lip, and alveolar ridge, termed burning mouth syndrome.

Special Considerations for Dental Hygiene Care

The client’s involuntary muscle movements create a safety concern for the clinician, and methods to address this problem were discussed previously. In severe cases it may be necessary to refer the client to be treated under general anesthesia. In addition, the client may be susceptible to orthostatic hypotension and dizziness caused by low blood pressure induced by the medications. Therefore the clinician should be cautious when adjusting the dental chair. As tremors and postural instability become more pronounced, clients with Parkinson’s disease have more difficulty performing their own oral hygiene care and become more dependent on their caregivers (see Chapter 41).

Oral Self-Care Instructions

In the early disease stages, individuals may be able to maintain their own oral hygiene, but the dexterity level needs to be continually assessed. As the disease progresses, more of the oral healthcare will be performed by the caregivers. Caregivers may find that brushing the teeth with a specially adapted manual or power toothbrush may be helpful. Because xerostomia is a common side effect of the medications, a saliva substitute can be recommended. It can enhance the comfort of wearing prosthetic appliances.

Tremors

Tremors are involuntary rhythmic repetitions or oscillations of movement at regular intervals. They may be physiologic, postural, static (resting), or intentional, and there are multiple causes. Intentional tremor is the most common tremor and the most common movement abnormality. It may start at any age but most commonly begins in the third or fourth decade. The cause and pathology are unknown. The tremor is most prominent during volitional movements, particularly skilled movements such as writing, and is aggravated when the individual is tense or after caffeine use. Head and voice tremor is common and is often confused with Parkinson’s disease tremor; however, essential tremor is faster, is not present during rest, and is not accompanied by other neurologic symptoms or signs. Alcohol, phenobarbital, and diazepam are effective in suppressing the tremor temporarily.

Cerebral Palsy

Cerebral palsy (CP) is a chronic disorder caused by damage to motor areas of the immature brain, primarily affecting the ability to control posture and movement. It is the second most common neurologic impairment in childhood, intellectual and developmental disability (formerly known as mental retardation) being the first. Most cases are caused by factors occurring before birth, although some are caused by factors occurring perinatally or during the first few years, such as traumatic brain injury, child abuse or neglect, and infections such as meningitis.

Characteristics

The symptoms of CP vary from mild, with only an awkwardness of movement or difficulty with fine motor skills, to severe, which may completely incapacitate the child. There may be associated conditions such as hearing and vision problems, communication problems, impairment of other senses, epilepsy, and intellectual and developmental challenges.

CP is classified into four broad categories according to the type of movement disorder and subdivided based on the number of limbs involved: monoplegia affects one limb; diplegia, two limbs and usually both legs; triplegia, three limbs; and quadriplegia, four limbs. Hemiplegia affects both limbs on one side of the body. The types of movement disorder are classified on the basis of motor activity and the brain part that was damaged (see Figure 46-2).

Most CP patients are of the spastic type, which is characterized by spasticity in the muscles leading to stiffness, resistance to movement, and contractures (Figure 46-4). The sudden, involuntary muscle contractions or spasms result from damage to the motor area (frontal lobe) of the cerebral cortex (see Figure 46-2).

Figure 46-4 A man with the spastic type of cerebral palsy. The spasticity of his antigravity muscles has caused his limbs to assume a severe flexed posture.

(From Porter SR, Scully C, Gleeson P: Medicine and surgery for dentistry, ed 2, Oxford, England, 1999, Churchill Livingstone.)

Athetoid or dyskinetic CP is characterized by slow, writhing, uncontrolled movements that usually affect the hands, feet, arms, or legs and sometimes the face, causing drooling and grimacing. The movements may increase with emotional stress and disappear during sleep. Children with CP may have dysarthria (difficulties with articulation) caused by problems in speech muscle coordination. People often think that children with CP have a mental or emotional problem because of their awkward movements, although this form of CP usually involves only the motor centers, resulting from damage to the basal ganglia (see Figure 46-2).

Ataxic CP is associated with problems in balance, coordination, and depth perception, caused by damage to the cerebellum (see Figure 46-2). The affected patients have poor coordination, walk with a wide-based gait, and may have difficulty with quick or precise movements. Mixed forms of CP, such as spastic-athetoid, have a combination of symptoms.

Treatment and Prognosis

Many types of therapy are used to help each child reach his or her optimum capabilities: physical and occupational therapy, speech and language therapy, biofeedback, orthopedic devices, and medications. Some children die in infancy, but most grow to adulthood. The main causes of death are respiratory and heart diseases.

Oral Clinical Findings

Most oral clinical findings in CP clients are related to disturbances of the oral musculature. Abnormal functioning of the tongue, lips, and cheeks can make oral clearance of food difficult, which is accentuated by the consumption of a soft, carbohydrate-rich diet. Those who have an associated convulsive disorder may be being treated with phenytoin and therefore are susceptible to gingival overgrowth, which will be discussed later in this chapter.

Fractures of the maxillary anterior teeth are common because of the uncoordinated ambulation and seizures that lead to frequent falls and the lack of lip protection to the protrusive teeth. Signs of attrition and bruxism result from severe involuntary grinding of the teeth. The teeth of children who are born with CP may exhibit enamel hypoplasia. This enamel defect may be related to the time of cerebral injury. Malocclusion commonly results from the abnormal functioning of the facial, masticatory, and lingual musculature, in conjunction with oral habits, such as tongue thrusting, mouth breathing, and faulty swallowing. Drooling, caused by impaired swallowing and hypotonic lip muscles, is frequently observed.

Special Considerations for Dental Hygiene Care

The client’s involuntary muscle movements create a safety concern for the clinician, and methods to address this problem were discussed previously. Abnormal muscle responses or reflexes are often triggered by changing the client’s head or neck position in the dental chair. The clinician can control the tonic labyrinthine and asymmetric tonic reflexes, as indicated in Table 46-3.

TABLE 46-3 Reflex Responses of Cerebral Palsy Conditions and Their Management

| Condition | Tonic Labyrinthine Reflex | Asymmetric Tonic Neck Reflex |

|---|---|---|

| Stimuli | Tilting head backward, so neck loses support | Turning head to one side, away from midline |

| Response | Body into full extension | Arm and leg on face side extend |

| Arms and legs extend and stiffen | Opposite arm and leg flex | |

| Prevention | Keep head supported and flexed | Use rear operating position |

| Maintain chair in upright position | Stabilize head in midline position | |

| Hands folded at midline | ||

| Management | Bring arms forward | Place face in midline |

| Separate legs | Help flex extended arm and leg | |

| Massage shoulders |

Adapted from DeBiase CB: Treating the patient with cerebral palsy, Dent Hyg News 5:13, 1987.

Informing the client when lowering, raising, or tilting the dental chair also may prevent a startle reflex.

Oral Self-Care Instructions

The client’s dexterity level needs to be assessed in order to develop an oral self-care plan. A specially adapted or power toothbrush, as well as a floss holder, may be needed. Fluoride or chlorhexidine rinses may be recommended, but rinsing would probably need to be monitored by a caregiver. Saliva substitutes can be recommended if medications have caused dry mouth. Written instructions should be given to clients and/or caregivers for them to refer to at home.

Multiple Sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a CNS disorder in which there is myelin sheath destruction of specific axons causing multiple neurologic symptoms that accrue over time. MS is the most common progressive and disabling neurologic condition affecting young adults. It typically begins in early adulthood, with a mean onset age of 33 years. Caucasian women are more frequently affected, and it is more common in the cold and temperate climates of the higher latitudes in both hemispheres, predominantly affecting individuals of northern European ancestry.

Characteristics

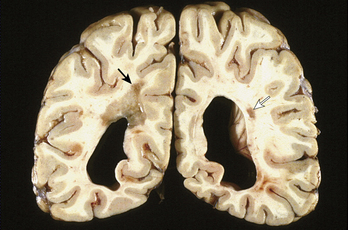

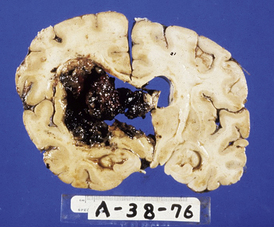

The main disease characteristic is the presence of numerous demyelinated nerve axons in the brain and spinal cord. The myelin sheath’s lipid composition provides axon insulation, so the sheath degeneration interferes in nerve impulse transmission. Current theories favor an immunologic pathogenesis of MS, with or without the presence of a triggering infectious agent. Demyelination results from autoimmune-related inflammation, involving the action of macrophages, lymphocytes, cytokines, antimyelin antibodies, or a combination of these agents. No two patients with MS are exactly alike, and the clinical manifestations in a particular individual are related to the lesion distribution within the CNS. Lesions may be found virtually anywhere within the white matter regions, which is so called because of the white appearance of the myelinated axons located there. The cerebral hemispheres, brainstem, cerebellum, and spinal cord are particularly vulnerable (see Figure 46-1 and Table 46-2). The affected areas consist of discrete demyelinated plaques that range in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters and are often around the lateral brain ventricles (Figure 46-5).

Figure 46-5 Coronal section of the brain of a patient who had multiple sclerosis. Note the large demyelinated plaque over the left ventricle (black arrow) and a smaller demyelinated plaque lateral to the right ventricle (white arrow).

(From Little JW, Falace DA, Miller CS, Rhodus NL: Dental management of the medically compromised patient, ed 7, St Louis, 2008, Mosby.)

Motor symptoms are common and include muscular weakness and spasticity caused by lesions of nerve fibers from the cerebrum motor cortex to the spinal cord motor neurons. Lesions in the cerebellar white matter or cerebellar pathways may produce prominent gait and extremity incoordination (ataxia) and a halting or scanning quality of speech. Severe upper extremity intention tremor may make the simplest self-care tasks impossible, and severe gait ataxia may prevent effective ambulation even when muscular strength is adequate.

Visual disturbances (e.g., impaired visual acuity, impaired color vision, visual field deficits, double vision, optic neuritis, and pain in or behind the eye) are common and may be the first symptom. Other sensory symptoms include numbness, tingling, impairment of temperature sensation, abnormal sense of limb position, and pain. Bladder, bowel, and sexual dysfunction also result from the nerve conduction disturbance. Severe fatigue complaints are common, and exhaustion after an ordinary day’s activities may frequently be disabling.

Treatment and Prognosis

The natural progression of MS is unpredictable. Trauma, infection, and surgery have all been associated with worsening of MS. Fever, heavy physical exertion, hot weather, a hot shower or bath, and exposure to sunlight may all cause a transient and reversible worsening of existing symptoms. In most MS patients the disease is initially exacerbating-remitting, and after several years there is a transition to a slow and relentless chronic progression. In some patients the disease maintains an exacerbating-remitting course, and in others the course is benign, with the patient having only one or two mild exacerbations and no permanent functional disability.

The management of MS includes treating the acute exacerbation with medications, such as steroids, and preventing and treating associated medical and psychologic complications with medications appropriate for the symptoms.

Oral Clinical Findings

Clients with MS exhibit extraoral complications. They often experience facial pain and temporomandibular joint and muscle dysfunction, and sometimes trigeminal neuralgia. With progression of MS, as the client loses muscular coordination, oral hygiene care is difficult, and the involvement of the tongue and facial muscles interferes with the self-cleansing mechanisms in the oral cavity. Medications may induce xerostomia or gingival enlargement.

Special Considerations for Dental Hygiene Care

Relapses in disease symptoms may be stimulated by various types of infections. Frequent dental hygiene appointments will help prevent oral infections and thus prevent exacerbations of the disease process. Short appointments scheduled in the morning may minimize fatigue, and a comfortable, quiet, relaxed environment may reduce stress. The client may be sensitive to heat, so the room temperature needs to be kept cool. Clients may have incontinence problems, so frequent bathroom breaks may be needed.

Oral Self-Care Instructions

Adaptations for problems in ambulation, muscle weakness, and tremors were discussed at the beginning of the chapter. Disturbances in the client’s visual acuity need to be considered in discussions of oral health maintenance. Because of the patients’ limited dexterity, power or modified toothbrushes may be easier for the patient to use. Saliva substitutes and xylitol-containing gum and mints are indicated for dry mouth. Patients may have a slow response to instructions, so visual aids in the office and pamphlets for home are appropriate.

PERIPHERAL NEUROPATHIES

Peripheral neuropathies are abnormalities that affect the PNS. Normally the dendrites of peripheral sensory cranial and spinal nerves receive input (i.e., pain, temperature, touch, pressure, vision, hearing) from the body or external environment, and the axon transmits this information to cells in the CNS. Cells in the CNS process this information and respond via motor nerves to the muscle or internal organs. Interference at any stage impairs the conduction of nerve impulses.

Pain is the most upsetting symptom to the patient and the hardest to treat. It can be described in several ways, including burning, constant pain; short jabbing pain; tight or bandlike pressure pain; cold, frostbitelike pain; and painful, sunburnlike hypersensitivity to touch. Other symptoms include paresthesias (prickles or “pins and needles”), sensation loss, unstable balance, sensory loss, or weakness, especially in the lower extremities.

Specific neuropathic conditions are associated with alcoholism (Chapter 51), diabetes (Chapter 43), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (Chapter 45). See specific chapters for details.

Facial Neuropathy or Bell’s Palsy

Bell’s palsy is one of the most common neurologic disorders affecting the cranial nerves and is the most common cause of an acute facial paralysis. Although the cause is generally unknown, research supports a viral cause. It is thought that the virus triggers edema and inflammation in the nerve, leading to infarction and damage to the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII). Herpes simplex virus is believed to be the most likely causative virus. Temporary or permanent facial paralysis also may be iatrogenically caused from damage to nerves during intraoral local anesthetic injection or during oral surgery procedures.

Characteristics

Patients may describe an abrupt functional impairment. Their face becomes distorted, and they think they have had a stroke (Figure 46-6). Other common signs and symptoms include pain behind the ears, drooling, altered taste, tearing from the eyes, numbness or paralysis on the affected side of the face, and a recent viral syndrome and/or upper respiratory infection.

Figure 46-6 Unilateral facial paralysis in a patient with Bell’s palsy. On the man’s attempt to smile there is a lack of movement of the entire right face and forehead muscles.

(From Little JW, Falace DA, Miller CS, Rhodus NL: Dental management of the medically compromised patient, ed 7, St Louis, 2008, Mosby.)

Treatment and Prognosis

Treatment includes steroids and sometimes antiviral agents, and eye protection with lubricants, artificial tears, and protective eyewear. Other treatments include seventh nerve surgical decompression and galvanic stimulation of paralyzed facial muscles. Most patients recover without cosmetically obvious deformities. With incomplete motor regeneration, patients may have nasal obstruction, excessive tearing, or problems with oral musculature. Incomplete sensory regeneration may result in taste loss or impairment and disagreeable or impaired sensations.

Oral Clinical Findings

Oral musculature numbness affects the ability to chew and to maintain a self-cleansing environment. This numbness could lead to oral trauma, such as cheek biting, and to increased debris on the side of the mouth that is affected. Other common effects are dry mouth, glossitis, and candidiasis.

Special Considerations for Dental Hygiene Care

Adaptations for impaired oral musculature were previously discussed. In addition, the client should wear protective eyewear to prevent foreign material, such as prophylaxis paste, from entering the eye, because the client’s eyelids may not close on the affected side of the face.

Oral Self-Care Instructions

Sensation loss impedes the individuals’ ability to feel what they are doing during brushing. Establishing a brushing pattern helps the client avoid missing areas. Rinsing with water after eating helps reduce trapped food, which the client may not feel. Use of an oral irrigator also is beneficial.

Trigeminal Neuralgia

Trigeminal neuralgia or tic douloureux is a mononeuropathy of the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V) that results in severe pain. Usually it is usually caused by nerve compression from crossing arteries, benign tumors, or vascular malformations. The condition is seen more often in females, with a mean onset of 50 years.

Characteristics

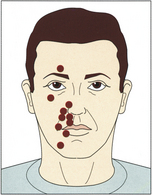

Trigeminal neuralgia is characterized by sudden, brief, severe lancinating (shooting or sharp stabbing) pains occurring in the distribution of one or more of the branches of the trigeminal nerve. The symptoms are usually unilateral, occur most often in the third or mandibular division, and occur more often on the right side of the face. The pain usually lasts less than a minute and can be triggered by speaking, eating, cold temperatures, or touching the face at specific sites (Figure 46-7). Pain remission may last months or years, but pain eventually becomes chronic.

Figure 46-7 Distribution of trigger zones for trigeminal neuralgia. Pain is triggered by irritation of cranial nerve V.

(From Perkin G: Mosby’s color atlas and text of neurology, London, 1998, Mosby-Wolfe.)

Neurologic examination is usually normal; however, there may be areas of hypesthesia (impaired sensation) in some patients.

Treatment and Prognosis

The first treatment of choice is drug therapy. Surgical procedures are tried if drug treatment is not tolerated or is ineffective.

Oral Clinical Findings

No significant oral findings are due to the disease alone. Oral ulcerations and xerostomia could result from medications. The patient may avoid oral hygiene owing to the fear that it may trigger pain, therefore increasing the likelihood of plaque-related diseases.

Special Considerations for Dental Hygiene Care

The clinician needs to be empathetic. Patients should be allowed extra time to express their feelings about their pain. Full supine position may relieve pressure on the nerve. Local anesthetic administration may be necessary to relieve tissue pain resulting from manipulation during treatment. Short appointments are recommended to prevent client fatigue. Referral to a pain management physician or support group also is recommended.

SPINAL CORD DYSFUNCTION

The spinal cord lies within the vertebral column and is the lowest level in the hierarchy of complexity in the CNS. It receives sensory impulses brought in from the periphery, integrates reflex activity, sends motor impulses out to the viscera and skeletal muscles, and/or passes information on to higher CNS structures for synthesis and integration. Connected to the spinal cord are 31 pairs of nerves, which are numbered according to the spinal column level at which they emerge from the spinal cavity. There are eight cervical, 12 thoracic, five lumbar, five sacral, and one coccygeal nerve pairs. All spinal nerves are both sensory and motor.

Spinal Cord Injury

Spinal cord injury (myelopathy) (SCI) may occur from trauma or from diseases such as spina bifida, polio, MS, and cancer. The major causes of SCI are motor vehicle accidents, acts of violence, falls, and sports, especially diving. Most victims are males between the ages of 16 and 30; injuries result in some function loss in arms and legs (quadriplegia) more commonly than in only trunk and legs (paraplegia). Most victims have some other systemic or head injury.

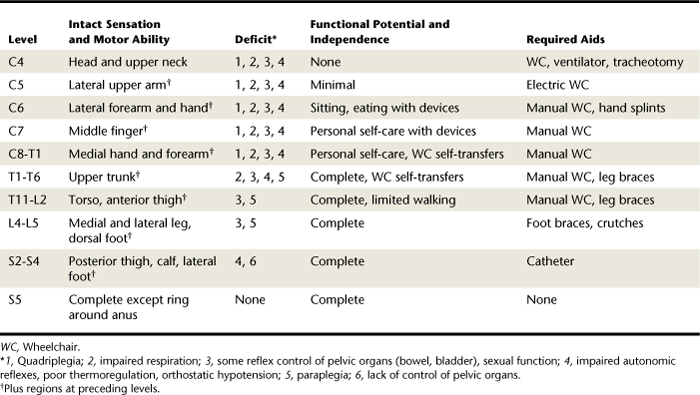

Characteristics

The effects of SCI depend on the level and type of injury. The extent of motor function at various levels and the person’s potential for independence are indicated in Table 46-4. Clients with SCI also may have problems with temperature and/or blood pressure control, chronic pain, and inability to sweat below the level of the injury.

Treatment and Prognosis

Even though the spinal cord remains intact, most people with SCI have a loss of function. Only in rare cases do individuals with SCI recover all functioning. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) has promoted mainstreaming people with SCI, but most are still not employed. People who use ventilators are at risk for respiratory infections and pneumonia. Cutaneous pressure sores (decubitus) are a major concern and if not properly treated can lead to death.

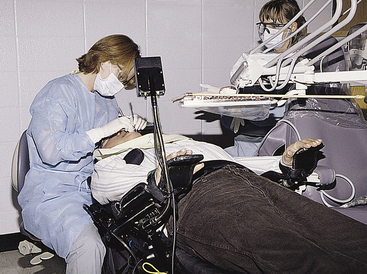

Dental Hygiene Care

The oral clinical findings and subsequent special considerations for dental hygiene care and oral self-care instructions all depend on the level and type of SCI. Adaptations for specific problems were previously described in this chapter and in Chapter 41. Wheelchair-bound patients may be more easily treated in the wheelchair if the wheelchair has a headrest and reclines (Figure 46-8).

Oral Self-Care Instructions

For clients without the use of their hands, the mouth and teeth play a critical role in performing a variety of tasks. Figure 41-3 in Chapter 41 illustrates a mouthstick for use by quadriplegic persons. The use of mouth-held appliances assists the client in grasping, stabilizing, and opening objects and contributes to the client’s maintenance of independence. The design, manufacture, and problems of mouthsticks are described in Chapter 41. Briefly stated, the appliance should be designed so that it does not harm the oral tissues. The occlusal forces need to be distributed throughout the mouth to prevent trauma to the periodontal supporting structures. Cleaning the appliance’s mouthpiece is an integral part of the oral self-care regimen. Compliance with these procedures to prevent oral disease and subsequent tooth loss is important because edentulousness severely affects the use of these appliances.

SEIZURE

A seizure is a brief (less than 2 minutes) disturbance of cerebral function caused by excessive abnormal neuronal discharge. Seizures are common, and during one’s lifetime there is a 6% chance of having one and a 3% chance of having more than one. About 1% of children younger than 5 years of age will have at least one seizure, usually associated with a high fever. Seizures result from primary CNS dysfunction or an underlying systemic or metabolic disorder (Box 46-1).

The specific cause is unknown in most cases. Characteristics include one or more of the following: a loss or altered state of consciousness, abnormal or cessation of motor activity, abnormal sensory perceptions, and/or loss of bowel and bladder control.

Epilepsy

Epilepsy is a seizure disorder in which the excessive abnormal neuronal discharges from cerebral function disturbances are recurrent. The specific underlying brain dysfunction causing the seizure disorder can be found in only approximately half of both childhood-onset and adult-onset seizures.

Characteristics

There are many types of seizures. Only three of the common ones are described here. Tonic-clonic seizures (grand mal) are the most common type and can be divided into several phases, beginning with vague prodromal symptoms (aura) that occur hours to days before the convulsion. A series of brief, bilateral muscle contractions may precede the tonic phase. Tonic (stiffening) contractions begin in the trunk and progress, including contraction of abdominal muscles, producing forced expiration across the spasmodic glottis and causing the characteristic vocalization (Figure 46-9). The clonic (convulsion) phase begins after generalized extension, with tonic contractions alternating with loss of muscle tone, causing rhythmic jerking of all four extremities, until contractions cease (Figure 46-10). Autonomic dysfunction (loss of bowel and bladder control) often occurs during the tonic and clonic phases. Persons experiencing seizures may bite the tongue or break bones as a result of the violence of the jerking during the clonic phase. Afterward the individual may enter a deep sleep or experience headaches, muscle aches, and stiffness.

Figure 46-9 A patient during the tonic phase of a generalized tonic-clonic seizure (grand mal). Note the extensor rigidity of the extremities and trunk.

(Adapted from Malamed SF: Medical emergencies in the dental office, ed 6, St Louis, 2007, Mosby.)

Figure 46-10 Diagrammatic representation of the violent flexor contractions of the clonic phase of a generalized tonic-clonic seizure (grand mal).

(Adapted from Malamed SF: Medical emergencies in the dental office, ed 6, St Louis, 2007, Mosby.)

Typical absence (petit mal) seizures are familial and occur almost exclusively in childhood between the ages of 3 and 12 years. The seizures consist of brief (10 to 30 seconds) episodes of altered states of consciousness during which the child has a vacant stare and sometimes eyelid blinking or lip smacking. Muscle tone is maintained. After the seizure the child goes on with normal activities and has no recollection of the seizure.

Generalized status epilepticus is defined as a single seizure lasting for at least 20 minutes or recurrent generalized seizures without regaining of consciousness between the seizure episodes. This is a life-threatening medical emergency and requires prompt and intensive therapy.

Treatment of Seizures

Anticonvulsant medications, such as phenytoin (Dilantin), are effective in preventing most seizures. Several are available, but sometimes the side effects are worse than the disorder (e.g., when a person has one seizure a year at night), in which case medication is not used.

Oral Clinical Findings

Seizures and epilepsy themselves do not produce oral changes, but the accidents resulting during the seizures and the medications to treat the condition may. Scarring of the lips, buccal mucosa, and especially the tongue may be indicative of past injury to the oral cavity during a seizure. Teeth also may have been injured—fractured from the forceful biting that frequently occurs during a grand mal seizure (Figure 46-11). Phenytoin, a common medication to control seizures, may cause severe gingival enlargement or overgrowth (Figure 46-12).The drug alters the metabolism of the gingival fibroblasts so that the cells produce excessive amounts of collagen. This drug-influenced gingival enlargement, which occurs in approximately half of these clients, may be disfiguring and may interfere with mastication and speech.

Special Considerations for Dental Hygiene Care

Major considerations in epileptic client management are prevention of seizures in the dental chair and preparation for managing seizures if they occur. When a client responds positively to seizures on a health history form, further information should be obtained. Examples of questions one could ask are listed in Chapter 10. Based on the client’s responses, one may choose to postpone treatment for fear of triggering a seizure in the dental chair. Nitrous oxide and oxygen sedation is known to elicit seizures in epileptics, so it is not recommended for them. Likewise, fatigue can induce seizures, so appointments should be made early in the day. Despite all preventive measures, seizures may still occur. Management focuses on preventing injury and maintaining adequate ventilation. Steps to follow are outlined in Box 46-2.

BOX 46-2 Management of Generalized Tonic-Clonic (Grand Mal) Seizures

Adapted from Malamed SF: Medical emergencies in the dental office, ed 6, St Louis, 2008, Mosby.

Dental hygiene continued-care appointments should be established based on the presence or severity of gingival enlargement induced by phenytoin.

DISORDERS OF HIGHER CORTICAL FUNCTION

Dementia

Dementia is characterized by a progressive intellectual decline that eventually leads to deterioration of occupational, social, and interpersonal functions. Onset is usually insidious, with memory disturbances frequently attributed to the normal aging process. Sooner or later other areas of cognition become impaired: orientation, language, perceptions, ability to learn new skills, calculation, abstraction, and judgment. Consciousness is preserved until terminal stages, and other neurologic signs usually do not develop until the syndrome is well established.

Even though dementia may occur at all ages, the incidence of most dementias, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD), rises substantially with increasing age. Dementia may be caused by the following factors: metabolic disorders, anemia, hypoxia and anoxia, brain tumor, trauma, infections, deficiency diseases, toxins, and medications.

Characteristics

In early stages individuals often complain of diminished energy and enthusiasm, show less interest in subjects they previously cherished, and may show emotional instability and heightened anxiety levels because of the awareness of failing mental functions. As the disease progresses, the patient becomes increasingly self-absorbed, anxiety increases, and the recognition of personal failure may lead to depression. At this stage there may be pronounced mood swings and poor judgment, followed by diminished drive and feeling. As the mental deterioration progresses, anxiety and depression disappear and are replaced by complete flatness of mood. Personal cleanliness deteriorates and patients will do little, if anything, spontaneously. At this stage, other neurologic dysfunctions, such as hemiparesis (one-sided weakness) and seizures, may develop. Lower-level cerebral functions usually remain intact until very late. Once the patient has reached the point of complete flatness of mood, inability to communicate, and total dependence on others, even treatable dementias are usually irreversible.

Dementia differs from the decline of physiologic processes during aging. In old age mental processes become slowed, but the older healthy person still retains a firm grasp on reality, is oriented, can reason, has good judgment, and can continue to lead an active and self-supporting life. Further characteristics of the elderly are described in Chapter 54.

Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease is a brain degenerative disorder that gradually destroys the ability to remember, reason, learn, and imagine. It is the most common form of dementia, affecting 10% or more of those older than 65 years and approximately 50% of those older than age 85. Risk factors include family history, aging, genetics, and Down syndrome.

Characteristics

AD is characterized by the presence of abnormal clumps (called senile plaques) and irregular knots (called neurofibrillary tangles) that destroy the areas of the brain associated with intellectual functions (Figure 46-13).

Figure 46-13 Coronal section of the brain from a patient with Alzheimer’s disease. The degeneration of the cerebral cortex neurons leads to the thinning of the cortex and secondary enlargement of the lateral ventricles.

(From Perkin G: Mosby’s color atlas and text of neurology, London, 1998, Mosby-Wolfe.)

The stages of the disease process are described in Chapter 54. In the early and middle stages of AD, affected individuals may be painfully aware of their intellectual decline, and it is important to support their emotional and mental health with affection and warmth. In the beginning there is simple forgetfulness, especially of directions to familiar places or recent events. There may also be personality changes such as restlessness, increased stubbornness, distrust, poor judgment and impulse control, and increased difficulty with activities requiring planning and decision making. Affected individuals may begin to withdraw socially. As the disease progresses, the ability to perform daily living tasks is lost, and there may be trouble recognizing everyone except the person’s closest daily companions. Communication becomes difficult as written and spoken language decline. In the last stages of the disease, patients with AD become bedridden, unable to recognize themselves or their closest family members.

Treatment and Prognosis

Because there is no cure for AD, treatment is aimed at prevention, slowing progression of the disease, and improving quality of life for the patients. Some of the dying neurons use acetylcholine for a neurotransmitter, so acetylcholine drugs are used to improve cognition, although the effects are not permanent. The period from the earliest symptoms to death has an average duration of 8 years. Death results from a secondary illness such as urinary tract infection or pneumonia.

Oral Clinical Findings

Clients with AD have more gingival disease and caries than the normal elderly population, mainly because of poor oral hygiene from significant neglect. Clients forget to brush, forget how to brush, may not want to brush, or may be resistant to a caregiver brushing their teeth. Medications, such as phenytoin to control seizures, may cause gingival enlargement (see Figure 46-12), and many induce salivary gland dysfunction.

Special Considerations for Dental Hygiene Care

A frightened and frustrated client may demonstrate uncooperative, even combative, behavior, so clients with AD are managed best with a caring and understanding approach (Box 46-3). Appointments should be scheduled early in the day and preferably when the office is not busy. The office environment should be as free of unnecessary noise, people, and physical clutter as possible. The caregiver should accompany the client to discuss special client management issues as well as oral care procedures.

BOX 46-3 Techniques for Communicating with Clients with Alzheimer’s Disease

Oral Self-Care Instructions

In the early stages of AD the client should be encouraged to be self-sufficient. Toothbrushing instructions should be given slowly, step by step, in simple, concrete language. As the disease progresses, the client becomes more dependent on his or her caregiver for oral home care, so the caregiver needs to be familiar with these procedures. Although a power toothbrush may be easier for a caregiver to use on the client, electrical appliances are known to disturb or be a safety concern to some individuals with AD. Mouth rinses are not usually recommended because the client may not understand that it would be harmful to swallow.

Disorders of Speech and Language

Speech or vocalization is the mechanical aspect of oral communication. It is produced by the coordination among the respiratory muscles, vocal cords, soft palate, tongue, and lips. Speech abnormalities can result from dysfunction in any of these structures. Speech disorders result in dysphonia (a disturbance in phonation) or dysarthria (a dysfunction in articulation). Almost all speech abnormalities result from peripheral, brainstem, and/or cerebellar dysfunction.

Language is a cognitive function using abstract symbols to communicate (comprehend, read, write, repeat, and converse). Language depends on central processing either to comprehend or to formulate the sounds and symbols. Language dysfunction, termed aphasia, includes disturbances in comprehension and expression of spoken or written language. It affects the ability to express oneself through speech, writing, and gesture and to understand the speech, writing, and gestures of others.

CEREBROVASCULAR DISEASE

Cerebrovascular Accident

Cerebrovascular accident (CVA) or stroke is an abrupt onset of neurologic deficits resulting from either ischemia or hemorrhage. It is the third most frequent cause of death in the United States, heart disease and cancer being the first and second. Approximately one-half million people per year in the United States are expected to experience strokes of all causes. It is the major cause of serious disability in adults.

Risk factors for stroke are listed in Box 46-4. The major factor is hypertension. Because hypertension is in most instances a treatable condition, the single most important measure in preventing strokes is detection and treatment of hypertension. A transient ischemic attack (TIA) is a transient focal neurologic deficit that persists for less than 24 hours and is followed by complete clinical recovery. Most TIAs do not last longer than 10 to 20 minutes.

BOX 46-4 Risk Factors for Stroke

Adapted from Collins R: Neurology, Philadelphia, 1997, Saunders.

Characteristics

A CVA results from a lack of oxygen supply to the brain due to an occlusion of blood supply. The diminished or lack of blood flow into the brain tissues results from embolism (occlusion of an artery), atherothrombosis (fatty clot within a blood vessel), or systemic hypoperfusion (e.g., from cardiac pump failure). The ischemia leads to infarction (necrosis or death) of brain tissue supplied by the affected artery or arteries. Hemorrhage, or rupture of a brain vessel, causes leakage of blood into the brain tissue, the ventricles, or the space between the brain and skull. The resultant hematoma exerts pressure on brain tissue, causing infarction of adjacent tissue (Figure 46-14).

Figure 46-14 Cerebral infarction in an individual who had chronic hypertension. The blood from the intracerebral hemorrhage has displaced the brain tissue.

(From Little JW, Falace DA, Miller CS, Rhodus NL: Dental management of the medically compromised patient, ed 7, St Louis, 2008, Mosby.)

Regardless of the underlying cause, in the development of a stroke a certain part of the brain does not receive an adequate blood supply for a period of time. If brain tissue is deprived of blood supply for 10 to 20 minutes, infarction will occur. Occlusion of a given artery does not necessarily imply brain tissue infarction in the perfusion territory of that blood vessel because adequate collateral circulation may exist. If adequate blood supply is restored to the brain within time, there will be total resolution of the neurologic deficit.

The right and left hemispheres specialize in different functions, and the two sides of the brain are interconnected. Sensory and motor axons cross on their way to or from the cerebral cortex, so the left side of the brain controls motor and sensory input for the right side of the body and vice versa. Therefore the side of the face and body affected is opposite that of the brain injury. Box 46-5 illustrates the differences between right-sided and left-sided brain damage.

Common Impairments

Signs and symptoms depend on the brain sites affected, but the following are the more common ones:

Motor impairments. These are the most common deficits and usually involve face, arm, and leg, alone or in combination on the same side. Motor functions affected include cranial nerve functions to muscles of the head and neck, reflexes, gait, balance, and coordination. Often there is apraxia (the inability to perform purposeful movements), although no muscular paralysis or sensory disturbance is present.

Motor impairments. These are the most common deficits and usually involve face, arm, and leg, alone or in combination on the same side. Motor functions affected include cranial nerve functions to muscles of the head and neck, reflexes, gait, balance, and coordination. Often there is apraxia (the inability to perform purposeful movements), although no muscular paralysis or sensory disturbance is present. Sensory deficits. Impairments range from loss of primary senses (e.g., vision, pain, temperature, touch) to more complex losses of perception.

Sensory deficits. Impairments range from loss of primary senses (e.g., vision, pain, temperature, touch) to more complex losses of perception.Treatment and Prognosis

Occupational and physical therapy can help the stroke patient learn new ways of performing activities of daily living, sometimes with the aid of assistive devices such as braces, wheelchairs, and special utensils.

Oral Clinical Findings

The specific oral findings of a CVA survivor depend on the areas of the brain affected and the type of CVA, as well as the resultant dysfunction. Motor dysfunction effects were previously described. Many prescribed medications cause xerostomia. Periodontal disease is associated with the risk of stroke, as well as heart disease (see Chapter 18). Although periodontal pathogen invasion into the periodontium induces bacteremia and a systemic inflammatory response, a causal relationship has not been established.

Special Considerations for Dental Hygiene Care

It is recommended that the stroke survivor not undergo any elective dental care within 6 months of the episode. A positive response to stroke on the health history form should elicit several follow-up questions, which are listed in Chapter 10. This information will determine the need for treatment modifications. A client who has had a stroke or TIA is at a greater risk for having another one, so prevention of a recurrence is of utmost concern. Factors such as pain and anxiety add to the risk and so need to be managed by creating a safe and comfortable environment. Efforts should be made to minimize fatigue and optimize energy and patience for both clinician and client. Adaptations for these clients’ problems in ambulation and muscle weakness were previously described.

Blood pressure should be carefully monitored because marked deviations in blood pressure increase the risk for recurrent CVAs. Blood pressure of 200 mg systolic and/or 115 mg diastolic or higher warrants immediate medical consultation before dental treatment is initiated. Many CVA and TIA survivors receive anticoagulant therapy, which predisposes them to excessive bleeding. Physician consultation is needed to determine whether the therapy should be altered. The physician also is consulted regarding prophylactic premedication necessity. Oral infection presence may cause changes in blood coagulation factors, which may trigger a repeat CVA. The minimum amount of a local anesthetic with vasoconstrictor is recommended.

Oral Self-Care Instructions

During the immediate poststroke phase, caregivers perform all the daily hygiene functions; therefore they need proper toothbrushing demonstrations and instructions and/or information about maintenance of any dental prosthesis so that they can perform these tasks until the client has relearned them. Even during the rehabilitation phase, clients with residual physical deficits may need assistance performing oral hygiene procedures. Special adaptations that foster the stroke survivor’s self-sufficiency were described previously.

The discomfort from xerostomia can be alleviated by saliva substitutes and associated dry mouth products. Fluoride therapy and xylitol gum and mints are beneficial to prevent root caries.

SENSORY DISORDERS

Deficits in Hearing

Hearing loss is the third most common chronic condition in the older population. Although only 5% of people aged 18 to 44 have a deficiency, the prevalence is 54% for people older than age 65. Five percent of children have a hearing loss. This loss can cause developmental delays of speech and language. Language deficits lead to learning problems, which cause decreased academic achievement. Communication problems also can lead to poor self-concept and social isolation.

Characteristics

Hearing loss is classified based on what part or where in the auditory system there is damage. Sensorineural hearing loss occurs when there is damage to the inner ear (cochlea) or to nerve pathways in the auditory nerve (cranial nerve VIII) between the cochlea and the brainstem. In addition to loss of volume, nerve damage is associated with high-frequency loss, and there are deficits in hearing clearly or understanding speech. This type of loss can be caused by drugs that are toxic to the auditory system (aspirin), viruses, diseases, birth injury, noise exposure, head trauma, tumors, genetic syndromes, and aging. Sensorineural hearing loss is a permanent loss. Central auditory processing disorders occur when the central auditory processing center (the temporal lobe of the cerebral hemisphere) (see Figure 46-1) is damaged by tumors, diseases, infarcts, heredity, or unknown causes. This type of loss involves problems with sound localization, auditory discrimination, temporal aspects of sound, auditory pattern recognition, and the ability to hear decreasing or competing acoustic signals.

The severity of hearing loss is described as the lowest value (decibels or dB) of sound heard at three different frequencies. The normal range is 10 dB to 15 dB, and values progressively increase with greater impairment. For example, 71 dB to 90 dB is the severe loss range. Both exposure time length and noise amount determine effects on hearing loss. Sounds greater than 80 dB are potentially dangerous. Hair cells of the inner ear can be damaged by brief intense sounds, like an explosion, or by continuous or repeated noise exposure.

Oral Clinical Findings

No specific oral clinical findings are associated with hearing deficits; however, the overall oral health of deaf or hearing-impaired clients may be compromised because of their limited access to dental care and information.

Special Considerations for Dental Hygiene Care

Communication is the major challenge in achieving and maintaining optimal oral health in clients with hearing deficits. Scheduling and confirming appointments for both deaf and hearing-impaired clients should be conducted by mail, either regular or electronic. Suggestions for facilitating communication with clients with impaired hearing are listed in Box 46-6.

BOX 46-6 Techniques for Communicating with Impaired Hearing Clients

Adapted from Potter PA, Perry AG: Fundamentals of nursing, ed 7, St Louis, 2009, Mosby.

Each communication mode has advantages and disadvantages. For each deaf client the preferred mode of communication initially needs to be established.

Lipreading or speech reading is difficult to learn and use. Only about 30% of sounds in the English language are visible on the lips. Many sounds appear the same on the lips, and others are not visible at all. Speaking should occur at a natural pace without exaggerated lip movements. Any exaggeration distorts the visible lip pattern for the reader. Although most deaf people can lipread to some extent, few will rely on this method alone.

Lipreading or speech reading is difficult to learn and use. Only about 30% of sounds in the English language are visible on the lips. Many sounds appear the same on the lips, and others are not visible at all. Speaking should occur at a natural pace without exaggerated lip movements. Any exaggeration distorts the visible lip pattern for the reader. Although most deaf people can lipread to some extent, few will rely on this method alone. American Sign Language (ASL) is the primary means of interpersonal communication for persons who have had a hearing loss since early life. ASL consists of its own vocabulary, idioms, grammar, and syntax, distinct from written and spoken English. Body gestures and facial expressions help convey meaning. The knowledge of a few specific signs may be beneficial for health professionals. ASL classes are widely available, offered at community colleges, universities, and Red Cross chapters.

American Sign Language (ASL) is the primary means of interpersonal communication for persons who have had a hearing loss since early life. ASL consists of its own vocabulary, idioms, grammar, and syntax, distinct from written and spoken English. Body gestures and facial expressions help convey meaning. The knowledge of a few specific signs may be beneficial for health professionals. ASL classes are widely available, offered at community colleges, universities, and Red Cross chapters. Finger spelling (American manual alphabet) is the manual reproduction of English using the hands and fingers. It is tiring and time-consuming; therefore, it is used primarily to supplement ASL for proper names and for words that do not have a present sign.

Finger spelling (American manual alphabet) is the manual reproduction of English using the hands and fingers. It is tiring and time-consuming; therefore, it is used primarily to supplement ASL for proper names and for words that do not have a present sign. Interpreter use to translate the spoken words into sign language is costly and limits the client’s privacy; however, according to the ADA, the dental office, being a place of public accommodations, must retain and pay for an interpreter if one is needed to achieve equally effective communication. When using an interpreter, focus still should be directed at the client.

Interpreter use to translate the spoken words into sign language is costly and limits the client’s privacy; however, according to the ADA, the dental office, being a place of public accommodations, must retain and pay for an interpreter if one is needed to achieve equally effective communication. When using an interpreter, focus still should be directed at the client. Writing is probably the best method of communication when the speaker does not know sign language; however, it is time-consuming. Some deaf persons do not read or write beyond the fifth-grade level, so your notes need to be kept simple and easy to read. Paper and pencil should be conveniently located and disposed of after the visit to prevent cross-contamination. Laminated cards of expressions and phrases commonly used during treatment are also useful.

Writing is probably the best method of communication when the speaker does not know sign language; however, it is time-consuming. Some deaf persons do not read or write beyond the fifth-grade level, so your notes need to be kept simple and easy to read. Paper and pencil should be conveniently located and disposed of after the visit to prevent cross-contamination. Laminated cards of expressions and phrases commonly used during treatment are also useful. Electronic aids are available to facilitate communication. Teletypewriters (TTYs) and telecommunications devices (TDDs), containing an alphanumeric keyboard and an LCD screen, function to send text messages back and forth by telephone; however, both parties must have the equipment. In recent years, electronic mail probably has assumed that function as computers and Internet access are more widely available. Clients with limited hearing also may prefer this mode of communication.

Electronic aids are available to facilitate communication. Teletypewriters (TTYs) and telecommunications devices (TDDs), containing an alphanumeric keyboard and an LCD screen, function to send text messages back and forth by telephone; however, both parties must have the equipment. In recent years, electronic mail probably has assumed that function as computers and Internet access are more widely available. Clients with limited hearing also may prefer this mode of communication.Hearing-impaired clients who wear hearing aids require specific adaptations in the dental environment. Although most hearing aids amplify all sounds, some of the newer ones do have a directional microphone to decrease extraneous sounds. In either case, all extrinsic noise should be eliminated or reduced to minimize the client’s discomfort. Background music should be turned off, as should the saliva ejector and suction when not in use. Unnecessary instrument rattling should be avoided. The hearing aid should be turned down or removed when ultrasonic scalers or dental handpieces are used but turned on again for oral hygiene instruction.

Oral Self-Care Instructions

Correct brushing and flossing techniques should be demonstrated step by step on clients while they watch in the mirror. Disclosing agents help identify plaque biofilm, and visual aids such as pictures and diagrams are useful to discuss the disease process. Written instructions and pamphlets or brochures on brushing, flossing, and causes of gum disease will promote clients’ understanding of plaque control and the importance of preventing gingivitis and periodontitis.

Deficits in Vision

Visual deficits can occur anywhere from the eye via the optic nerve (cranial nerve II) to the visual region (occipital lobe) of the cerebral cortex (see Figure 46-1).Terms used to describe common visual deficits are defined in Box 46-7.

BOX 46-7 Descriptive Terms for Visual Deficits

There are about 10 million blind and visually impaired individuals in the United States, and about 1.3 million of them are legally blind. About 5.5 million individuals 65 years of age or older are blind or visually impaired.

Characteristics

Age-related vision loss can be caused by the following conditions:

Macular degeneration (age-related macular disease) is the leading cause of vision impairment and legal blindness in individuals 50 years of age and older. There is damage to the central visual area, the macula, which is responsible for the ability to see central vision and detail.

Macular degeneration (age-related macular disease) is the leading cause of vision impairment and legal blindness in individuals 50 years of age and older. There is damage to the central visual area, the macula, which is responsible for the ability to see central vision and detail. Glaucoma is the leading cause of blindness among African Americans and the second most common leading cause of blindness in the United States. It is caused by a buildup of pressure in the eye, with resultant optic nerve damage. Side vision is affected before central vision. It cannot be prevented but can usually be controlled with medication.

Glaucoma is the leading cause of blindness among African Americans and the second most common leading cause of blindness in the United States. It is caused by a buildup of pressure in the eye, with resultant optic nerve damage. Side vision is affected before central vision. It cannot be prevented but can usually be controlled with medication.Oral Clinical Findings

Oral abnormalities would not be expected to occur at a greater rate than in the sighted population, unless a blind or visually impaired person has other medical conditions or disabilities. There may be a greater incidence of poor oral hygiene and the subsequent gingivitis and periodontitis because of the client not being able to see her or his oral hygiene efforts and possibly from not having received effective oral hygiene instructions.

Special Considerations for Dental Hygiene Care

Minor adaptations in client management need to be made to effectively accommodate clients with visual impairments, mostly increased verbal descriptions of surroundings and procedures. When a blind or visually impaired person arrives in the dental office, he or she should be greeted by someone who acclimates them to the layout of the reception area, especially furniture location and available chairs. When clinicians greet the client in the reception area, they should introduce themselves each time. If at the initial appointment the clinician describes himself or herself, the client is better able to form an image of the clinician as a person. Other office staff should be introduced so that the client can recognize their voices whenever they speak because the client will be hearing the noises, movements, and conversations of others in the background.

Box 46-8 offers suggestions to be used when leading the client to the treatment room. All obstacles should previously have been cleared away. New clients are informed how the operatory is set up, and for returning clients, any changes, especially new furniture arrangements, are described. Guide dogs are permitted to remain in the treatment area so they can be kept close to their master at all times. The dog should not be distracted or touched but led to a nearby but out-of-the way corner.

BOX 46-8 Sighted Guide Techniques to Assist a Blind Person

Adapted from Sighted guide techniques, Braille Institute, 741 N. Vermont Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90029.

For clinical procedures, each step is described in detail before proceeding, as well as all instruments and materials and their application. Clients can be allowed to handle instruments, but assistance is required when the client explores instruments with sharp ends. A second set of sterilized instruments is used for the actual care. Also, clients are allowed to feel a moving prophylactic cup on a fingernail. Each dental material flavor, taste, and feeling also is described. The mirror and explorer are tapped together so clients gets a sense of what these objects sound like when they come in contact with each other. Informing clients first will avoid surprising them with sounds, such as from the evacuator, and with movements, such as of the chair, air, water, or power-driven instruments. Maintaining contact of a finger on a tooth or through retraction, while changing instruments, avoids repeated orientation. Clients always are told when the clinician is leaving and reentering the room to avoid embarrassment.

Oral Self-Care Instructions

Oral hygiene instruction for blind clients can be approached in several ways, all involving clear verbal, step-by-step technique descriptions. One method begins with the client demonstrating current brushing technique in his or her own mouth. Deficiencies are refined and corrected by the clinician, who places a hand on the client’s hand to guide hand position and movements while concurrently verbally describing the technique. Another way of demonstrating proper brushing is for the clinician to perform the task inside the client’s mouth. To help children become aware of a clean feeling in the mouth, they can be taught to feel their teeth with the tongue. Flossing is approached in a similar manner. All clients are told that they should hear the teeth squeak with the floss when the tooth surface is clean. Audiotapes or materials prepared in Braille can be provided to supplement verbal plaque biofilm and oral disease process explanations.

When oral hygiene instructions are given to visually impaired clients, the following factors are considered. Clients should be positioned for the best view and should be wearing their eyeglasses before instructions are started. Clients should not be expected to be able to see fine detail, such as on a radiograph. Written instructions and educational materials in large print need to be provided for clients to take home and read at their own pace.

CLIENT EDUCATION TIPS

Individualize recommendations and expectations for self-care based on evaluating the physical and mental condition of the client.

Individualize recommendations and expectations for self-care based on evaluating the physical and mental condition of the client. Facilitate the client’s self-sufficiency by modified oral hygiene aids: toothbrushes with adapted handles, power toothbrushes, toothpaste tubes with flip-top caps or pump dispensers, and floss-holders. Twice-daily use of an antimicrobial mouth rinse is also recommended.

Facilitate the client’s self-sufficiency by modified oral hygiene aids: toothbrushes with adapted handles, power toothbrushes, toothpaste tubes with flip-top caps or pump dispensers, and floss-holders. Twice-daily use of an antimicrobial mouth rinse is also recommended.LEGAL, ETHICAL, AND SAFETY ISSUES

The dental hygienist should not refuse to care for persons with disabilities because Title III of the Americans with Disabilities Act “makes it illegal to discriminate against persons with disabilities, and those with whom they associate, in the provision of services in places of public accommodation.”