Screening the Lower Quadrant

Buttock, Hip, Groin, Thigh, and Leg

The causes of lower quadrant pain or dysfunction vary widely; presentation of symptoms is equally wide ranging. Vascular conditions (e.g., arterial insufficiency, abdominal aneurysm), infectious or inflammatory conditions, gastrointestinal (GI) disease, and gynecologic and male reproductive systems may cause symptoms in the lower quadrant and lower extremity,1 including the pelvis, buttock, hip, groin, thigh, and knee. Some overlap may occur, but unique differences exist.

Cancer may present as primary hip, groin, or leg pain or symptoms. Primary cancer can metastasize to the low back, pelvis, and sacrum, thus referring pain to the hip and groin. Primary cancer may also metastasize to the hip, causing hip or groin pain and symptoms.

Pain may be referred from other locations such as the scrotum, kidneys, abdominal wall, abdomen, peritoneum, or retroperitoneal region. Lower quadrant pain may be referred through conditions that affect nearby anatomic structures, such as the spine, spinal nerve roots, or peripheral nerves, and overlying soft tissue structures (e.g., hernia, bursitis, fasciitis).1a

One of the keys to accurate and quick screening is knowledge of the types of conditions, illnesses, and systemic disorders that can refer pain to the lower quadrant, especially the hip and groin. Much of the information related to screening of the back (see Chapter 14), sacrum, sacroiliac (SI), and pelvis (see Chapter 15) also applies to the hip and groin.

Using the Screening Model to Evaluate the Lower Quadrant

When screening is called for, the therapist looks at the client’s personal and family history, clinical presentation, and associated signs and symptoms. Knowledge of problems that can affect the lower quadrant, along with the likely history, pain patterns, and associated signs and symptoms, shows us the steps to follow in screening.

Most often, the screening process takes place through a series of special questions. A few special tests may be used as well. Recognition of red flag signs and symptoms of systemic or viscerogenic problems can direct the client toward the necessary medical attention early in the disease process. In many cases, early detection and treatment may result in improved outcomes.

Past Medical History

Some of the more common histories associated with lower extremity, hip, or groin pain of a visceral nature are listed in Box 16-1. A previous history of cancer, such as prostate cancer (men), any reproductive cancers (women), or breast cancer, is a red flag as these cancers may be associated with metastases to the hip.

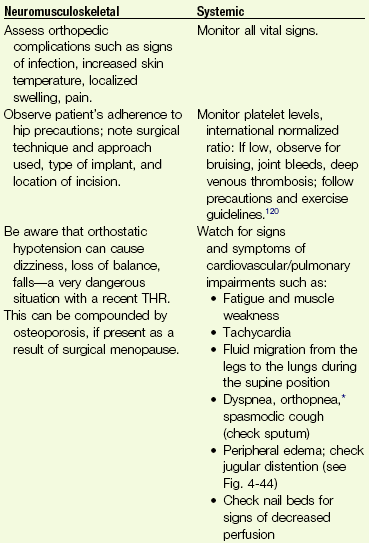

Past history of joint replacement (especially hip arthroplasty) combined with recent infection of any kind and new onset of hip, groin, or knee pain is suspicious. Postoperatively, orthopedic pins may migrate, referring pain from the hip to the back, tibia, or ankle. Loose components, improper implant size, muscular imbalance, and infection that occur any time after joint arthroplasty may cause lower quadrant pain or symptoms (Case Example 16-1).

There have been reports of hip, groin, and/or pelvic pain and/or mass associated with wear debris from hip arthroplasty. Polyethylene wear debris can also cause deep vein thrombosis, lower extremity edema, ureteral or bladder compression, or sciatic neuropathy.2

Risk Factors

Each condition, illness, or disease that can cause referred pain to the buttock, hip, thigh, groin, or lower extremity has its own unique risk factors. Many of the items listed as past medical history are risk factors. For example, femoral artery catheterization used to monitor ongoing hemodynamic status (arterial line; status post burn injuries, and/or individuals in the intensive care unit [ICU]) or used for individuals with poor upper extremity intravenous access can cause retroperitoneal hematoma formation or septic arthritis and subsequent hip pain.

Most known risk factors for systemically induced problems have been discussed in the individual chapters on each specific condition. For example, arterial insufficiency as a cause of low back, hip, buttock, or leg pain is presented as part of the discussion of peripheral vascular disease in Chapter 6 and again in Chapter 14 because it relates just to low back pain. Likewise, known risk factors for bone cancer or metastases as a cause of hip, groin, or lower extremity pain are presented in Chapter 13.

Many conditions with overlap symptoms (e.g., back and hip pain, pelvic and groin pain) are presented throughout this third text section (Systemic Origins of Neuromusculoskeletal Pain and Dysfunction) as part of the discussion of back pain (see Chapter 14) or pelvic pain (see Chapter 15).

Awareness of risk factors for various problems can help alert the therapist early to the need for medical intervention, as well as for direct education and prevention efforts. Many risk factors for disease are modifiable. Exercise often plays a key role in prevention and treatment of pathologic conditions. Recognizing red flags in the history and clinical presentation and knowing when to refer versus when to treat are topics of focus in this chapter.

Clinical Presentation

If no neuromuscular or musculoskeletal cause of the client’s symptoms can be identified, then the therapist must consider the following:

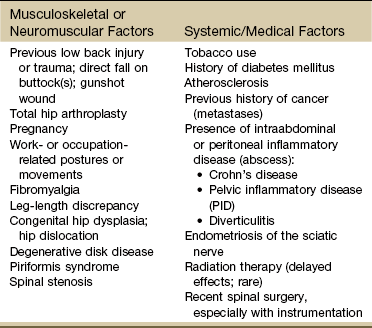

Hip and Buttock

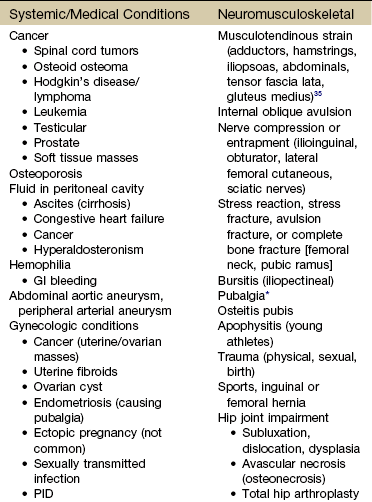

The physical therapist is well acquainted with hip or buttock pain (Table 16-1) as a result of regional neuromuscular or musculoskeletal disorders. The therapist must be aware that disorders affecting the organs within the pelvic and abdominal cavities can also refer pain to the hip region, mimicking a primary musculoskeletal lesion. A careful history and physical examination usually differentiate these entities from true hip disease.4

Pain Pattern: True hip pain, whether from a neuromusculoskeletal or systemic cause (Table 16-2), is usually felt posteriorly deep within the buttock or anteriorly in the groin, sometimes with radiating pain down the anterior thigh. Pain perceived on the outer (lateral) side or posterior aspect of the hip is usually not caused by an intraarticular problem but more likely results from a trigger point, bursitis, knee, SI, or back problem.

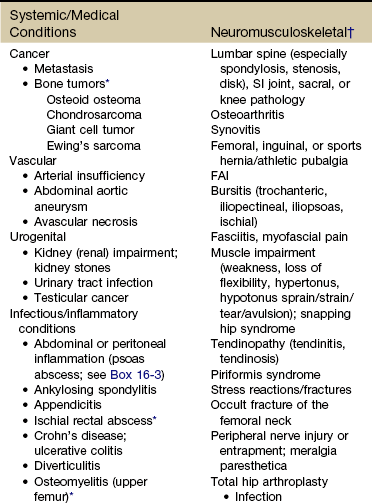

TABLE 16-2

PID, Pelvic inflammatory disease; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; SI, sacroiliac; FAI, femoroacetabular impingement; SCFE, slipped capital femoral epiphysis.

*Most common causes of the “Sign of the Buttock.”

†This is not an exhaustive, all-inclusive list, but rather, it includes the most commonly encountered adult neuromuscular or musculoskeletal causes of hip pain.

With true hip joint disease, pain will occur with active or passive motion of the hip joint; this pain increases with weight bearing.5 Often, an antalgic gait pattern is observed as the individual leans away from the affected hip and shortens the swing phase to avoid weight bearing.

When the underlying problem is related to soft tissue (e.g., abductor weakness) rather than to the joint as the source of symptoms, the client may lean toward the affected side to compensate for the downward rotation of the pelvis.6 With soft tissue involvement of the bursa or tendons (e.g., gluteus medius, gluteus minimus) pain may radiate from the buttock, greater trochanter, and/or lateral thigh down the leg to the level of insertion of the iliotibial tract on the proximal tibia.7-9

Pain with medial rotation and decreased hip medial range of motion is associated with hip osteoarthritis.10 Cyriax’s “Sign of the Buttock” (Box 16-2) can help differentiate between hip and lumbar spine disease.11-13 The presence of any of these signs may be an indication of osteomyelitis, neoplasm (upper femur, ilium), fracture (sacrum), abscess, or other infection.12

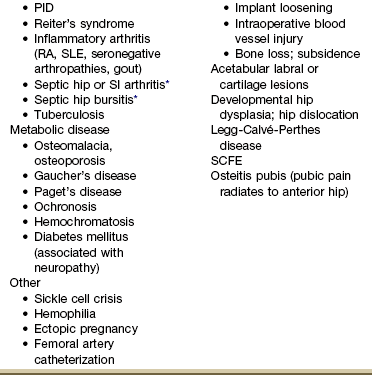

Neuromusculoskeletal Presentation: Identifying the hip as the source of a client’s symptoms may be difficult because pain originating in the hip may not localize to the hip but rather may present as low back, buttock, groin, SI, anterior thigh, or even knee or ankle pain (Fig. 16-1).

Fig. 16-1 Pain referred from the hip to other structures and anatomic locations. Pain from a pathologic condition of the hip can be referred to the low back, sacroiliac or sacral area, groin, anterior thigh, knee, or ankle.

On the other hand, regional pain from the low back, SI, sacrum, or knee can be referred to the hip. SI pain that localizes to the base of the spine may be accompanied by radicular pain extending across the buttock and down the leg. It can also cross the lateral hip area. Additionally, SI joint dysfunction can cause groin pain and, with referred pain to the hip, may be accompanied by an ipsilateral decrease in hip joint internal rotation of 15 degrees or more, thereby confusing the clinical picture even further.14,15

Overlying soft tissue structure disorders such as femoral hernia, bursitis, or fasciitis; muscle impairments such as weakness, loss of flexibility, hypertonus or hypotonus, strain, sprain, or tears; and peripheral nerve injury or entrapment, including meralgia paresthetica, can also cause localized hip (and/or groin) pain.

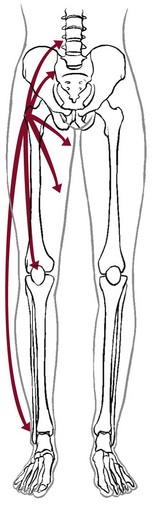

Hip pain referred from the upper lumbar vertebrae can radiate into the anterior aspect of the thigh, whereas hip pain from the lower lumbar vertebrae and sacrum is usually felt in the gluteal region, with radiation down the back or outer aspect of the thigh (Fig. 16-2).

Fig. 16-2 Pain referred to the hip from other structures and anatomic locations. A, Hip pain referred from the upper lumbar vertebrae can radiate into the anterior aspect of the thigh. B, Hip pain from the lower lumbar vertebrae and sacrum is usually felt in the gluteal region, with radiation down the back or outer aspect of the thigh.

The client with pain caused by component instability following total hip arthroplasty may report hip or groin pain with activity, pain at rest, or both. Clinically, a history of “start up” pain may indicate a loose component. After 5 or 10 steps, the groin pain subsides. Pain may increase again after a moderate amount of walking. Groin or thigh pain is most common with micromotion at the bone–prosthesis interface or other loose component, periosteal irritation, or an undersized femoral stem.16-18

The client reports a dull aching pain in the thigh with no history of systemic illness or recent trauma. Often, the pain is localized to the site of the prosthetic stem tip. The client points to a specific spot along the anterolateral thigh. Pain on initiation of activity that resolves with continued activity should raise suspicion of a loose prosthesis. Persistent pain that is not relieved with rest and continues through the night suggests infection, requiring medical referral.16,19

Systemic Presentation: A noncapsular pattern of restricted hip motion (e.g., limited hip extension, adduction, lateral rotation) may be a sign of pathology other than a joint problem associated with osteoarthritis, potentially a serious underlying disease (Case Example 16-2). The pattern of movement restriction most common with a capsular pattern for the hip is limitation of hip medial rotation, flexion, abduction, and, sometimes, slight limitation of hip extension. Empty end feel can be an indicator of potentially serious disease such as infection or neoplasm. Empty end feel is described as limiting pain before the end range of motion is reached but with no resistance perceived by the examiner.12

Whenever assessing hip joint pain for a systemic or viscerogenic cause, the therapist should look at hip rotation in the neutral position and perform the log-rolling test. With the client in the supine position, the examiner supports the client’s heels in the examiner’s hands and passively rolls the feet in and out. Decreased range of motion (usually accompanied by pain) is positive for an intraarticular source of symptoms. If normal hip rotation is present in this position but the motion reproduces hip pain, then an extraarticular cause should be considered.

Log-rolling of the hip back and forth, though not sensitive, is generally considered to be the most specific examination maneuver for intraarticular hip pathology because it rotates the femoral head back and forth in relation to the acetabulum and capsule, not stressing any of the surrounding extraarticular structures.20 The test does not identify the specific disease present but identifies the source of the symptoms as intraarticular.

Keep in mind that if normal rotations are present but painful, the problem may still be musculoskeletal in origin (e.g., SI, early sign of arthritic changes in the hip joint). Full motion is also possible in the early stages of avascular necrosis and sickle cell anemia. The log-rolling test should be combined with Patrick’s or Faber’s (flexion, abduction, and external rotation) test, long-axis distraction, compressive hip loading, and the scour (quadrant) test to determine whether the hip is a possible source of symptoms.

The presence of GI symptoms (e.g., nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, abdominal bloating or cramping) or urologic symptoms (e.g., urinary frequency, nocturia, dysuria, or flank pain) along with hip pain is cause to take a closer look. Palpable reproduction of painful symptoms is generally considered extraarticular.21

Negative radiographs of the hip may not rule out bone lesions. When intervention by the physical therapist does not yield relief of symptoms (or only temporary relief), further imaging studies may be needed. A careful review of risk factors and clinical presentation will guide this decision.22

Groin

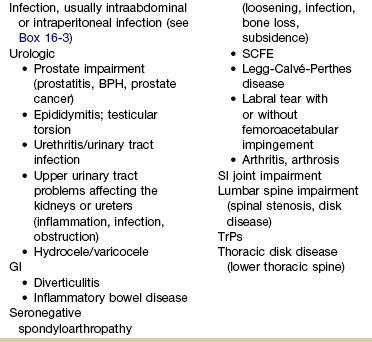

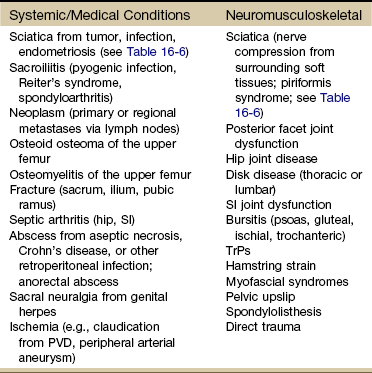

The physical therapist may see a client with an isolated groin problem, especially in the sports or military populations (Case Example 16-3), but more often, the individual has low back, pelvic, hip, knee, or SI problems with a secondary complaint of groin pain. Possible systemic and/or visceral causes of groin pain are wide ranging, whether appearing as an isolated symptom or in combination with pelvic, hip, low back, or thigh pain (Table 16-3 and Case Example 16-4).

TABLE 16-3

GI, Gastrointestinal; PID, pelvic inflammatory disease; BPH, benign prostatic hyperplasia; SCFE, slipped capital femoral epiphysis; SI, sacroiliac; TrPs, trigger points.

*Pubalgia is really a description of painful symptoms of the groin that can be caused by a wide range of muscular, tendinous, osseous, and even visceral structures. This condition may be labeled osteitis pubis when there is articular involvement such as arthritis, articular instability, or other articular lesions involving the pubic symphysis.35

Palpating the groin area is usually necessary in making a differential diagnosis. This can be a sensitive issue, and the therapist is advised to have a third person in the examination area. This person should be the same gender as the client. The therapist should explain the examination procedure and obtain the client’s permission.

During examination of the groin, the physical therapist may palpate enlarged lymph nodes, or the client may indicate these nodes to the examiner. Painless, progressive enlargements of lymph nodes or lymph nodes that are aberrant or suspicious for any reason, especially if present in more than one area or in the presence of a past medical history of cancer, are an indication of the need for medical referral.

Changes in lymph nodes without a previous history of cancer continue to represent a yellow or red flag. Tender, movable inguinal lymph nodes may be a sign of food intolerance or allergies or an indication that the body is fighting off an infectious process. The therapist should use his or her best clinical judgment in deciding what to do but should always err on the side of caution. When doubt arises, one should contact the physician and communicate any concerns, observations, or questions.

Neuromusculoskeletal Presentation: Neuromuscular or musculoskeletal causes of groin pain should also be considered (Case Example 16-5).23,24 Keep in mind that intraarticular pathology of the hip can manifest as groin pain owing to the innervation of the hip capsule. Extraarticular hip conditions radiate to the lateral or posterior aspects of the hip.25

Groin pain is a common complaint in sports that involve kicking and rapid change of direction (e.g., soccer, hockey). The most common musculoskeletal cause of groin pain is strain of the adductor muscles, most often involving the adductor longus. The history includes a specific trauma, repetitive motion, or injury, which occurs primarily at the junction of the muscle fibers and the extended tendon of origin. Acutely, this injury causes unilateral or bilateral pain during or after activity, with local palpation of the adductor longus origin, and during passive stretching or active contraction; eccentric activation may be even more painful.26,27 Acute injury may be followed in several days by ecchymosis.

Chronic groin or inguinal pain in the active athletic, sports, or military groups is often referred to as athletic pubalgia. Athletic pubalgia is sometimes used interchangeably to describe a sports or athletic hernia, which is a tear in the muscles of the inner thigh, lower abdomen, and/or the fascia.28 The term sports hernia may be a bit misleading because experts in this area do not consider this condition the same as a true inguinal or femoral hernia.29

Symptoms associated with athletic pubalgia are often described as deep groin or lower abdominal pain with exertion (usually unilateral). There may be a localized sharp burning sensation in the lower abdomen and/or inguinal region. Symptoms are relieved with rest but aggravated by activity, especially sport-related activities. As the condition progresses, symptoms may radiate to the adductor region, testes (male), and labia (female).30,31

Labral tears of the acetabulum can also cause groin pain. There may be a history of trauma but acetabular labral tears can occur without trauma. The clinical presentation can vary and include night pain, activity-related pain, positive Trendelenburg sign, and positive impingement sign (pain reproduced with hip flexion, adduction, and internal rotation). In young, active individuals with a primary complaint of groin pain with or without a history of trauma, the diagnosis of a labral tear should be suspected and investigated further.32

Femoroacetabular impingement presents as groin pain in young adults. Onset is gradual and progressive with intermittent groin pain after prolonged walking, prolonged sitting, or athletic activities that stress the hip. The impingement test (internal hip rotation and adduction while the hip is flexed) is always positive. Referral for a medical orthopedic examination and imaging studies may be warranted.33

Another common problem in the young athlete or long distance runner is osteitis pubis. Repetitive stress of the adductor group can cause inflammation at the musculotendinous attachment on the pubic bone, contributing to sclerosis and bony changes.34

Osteitis pubis with inflammation and sclerosis of the pubic symphysis can cause both acute and chronic groin pain. Individuals affected most often include competitive sports athletes involved in running, leaping and landing with force, repetitive kicking motions, or training on concrete, uneven, or other hard surfaces. Osteitis pubis can also occur as a result of leg length differences, faulty foot and body mechanics, or muscular imbalances and during pregnancy. Tenderness on palpation of the pubic symphysis helps identify this condition.26 Onset of midline pain that radiates to the groin is typical. Pain is reproduced by palpation of the pubis (anterior), passive hip abduction, and resisted hip adduction. Articular lesions involving the pubis symphysis can also lead to pubalgia.35

Insertional injuries of the upper attachment of the rectus abdominis muscle over the anteroinferior pubis (just lateral to the pubic symphysis) can lead to tendinopathy presenting as pubalgia. Without magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), insertional abdominis pathology cannot be differentiated from adductor pathology as the abdominis pubic attachment and the thigh adductor tendon blend to form one unit.35

Chronic, unresolved groin pain in the athletic population also has been linked with altered neuromotor control.36 The therapist may need to evaluate groin pain from a motor control point of view. See further discussion of stress reaction/fractures in the section on Trauma as a Cause of Hip, Groin, or Lower Quadrant Pain in this chapter.

Older adults are more likely to experience hip, buttock, or groin pain associated with arthritis, lumbar stenosis, insufficiency fractures, or hip arthroplasty. Arthritis is characterized by radiating pain to the knee, but not below, with decreased hip range of motion. Gait disturbances may be seen as arthritis progresses.17 Insufficiency fracture of the pubic rami can also cause hip/groin pain, resulting in a reluctance to bear weight on the affected side along with an antalgic gait.37

Hip and groin pain secondary to lumbar stenosis can manifest as low back pain that radiates to the lower extremities. The pain begins and gets worse with ambulation. Standing and walking may also increase symptoms when the lumbar spine assumes a more lordotic position and the ligamentum flavus folds in on itself, pinching the foramina closed. The client who has stenosis bends forward or sits to avoid painful symptoms. Clients who have a total hip arthroplasty for hip pain may have continued groin and buttock pain, secondary to sciatica or lumbar spinal stenosis.17

Systemic Presentation: The clinical presentation of groin pain from a systemic source does not vary from musculoskeletally induced groin pain. Once again, the key is to look at the client’s age (e.g., atherosclerotically induced vascular problems in the older adult), past medical history (e.g., previous history of cancer, liver disease, hemophilia), and gender (e.g., ectopic pregnancy, prostate or testicular problems).

In addition, asking about the presence of other symptoms and conducting a Review of Systems may help the therapist identify any one of the systemic causes listed in Table 16-3.

Thigh

Once again, we cannot emphasize enough the importance of conducting a thorough physical examination to rule out systemic or viscerogenic disease as the source of thigh pain; client history and lower quadrant screening examination should be performed (see Box 4-16).

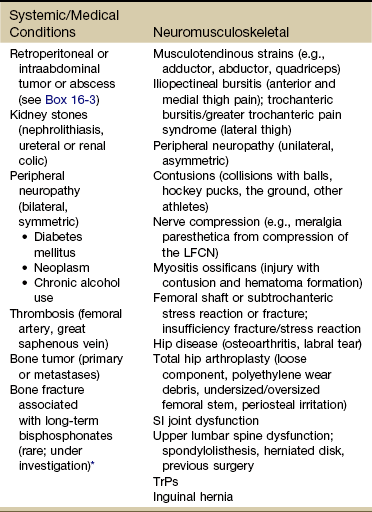

Anterior thigh pain is more common (Table 16-4), but posterior thigh pain may occur, with ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. Local anterior or posterior thigh pain of systemic origin generally occurs as a deep aching generated by soft tissue irritation or bone involvement. Radicular pain is usually a sharp, stabbing pain that projects in dermatomal distributions caused by compression of the dorsal nerve roots.

TABLE 16-4

SI, Sacroiliac; LFCN, lateral femoral cutaneous nerve; TrPs, trigger points.

*Reports of thigh pain and weakness in affected thigh for weeks to months before a low-energy fracture occurs. See Update: Thighbone fractures in women taking bisphosphonate drugs, Harvard Women’s Health Watch 17(7):6-7, 2010; and Abrahamsen B: Subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femur fractures in patients treated with alendronate: A register-based national cohort study, J Bone Miner Res 24(6):1095-1102, 2009.

Neuromusculoskeletal Presentation: The lower lumbar vertebrae and sacrum can refer pain to the gluteal and hip region, with pain radiating down the posterior or posterolateral thigh. Pain down the lateral aspect of the thigh to the knee may also be caused by inflammation of the tensor fascia lata with iliotibial band syndrome.5 A similar pattern has been reported in association with irritability, injury, or disease of the thoracolumbar transitional segments,38,39 and at least one case of synovial cell sarcoma presenting as iliotibial band syndrome has been reported.40

Anterior thigh pain is commonly disk related, resulting from L3-L4 disk herniation and occurring most often in older clients with a previous history of lumbar spine surgery. The clinical presentation varies among affected individuals, but thigh pain alone is most common (Case Example 16-6).

Use of the extreme lateral interbody fusion (XLIF) technique has been linked with thigh weakness and/or numbness postoperatively as a possible consequence of trauma to the psoas muscle or femoral nerve during the approach. Symptoms are temporary and appear to resolve with soft tissue healing following surgery.41

Back and thigh pain, a positive reverse straight leg raise (SLR) test, and depressed knee reflex are described more often in clients with disk herniation at the L3-L4 level than in clients with L4-L5 and L5-S1 levels.42,43 A positive reverse SLR is defined as pain traveling down the ipsilateral leg when the person is prone and the leg is extended at the hip and the knee. A positive test is caused by tension on the femoral nerve and its roots.44

Objective neurologic findings, such as hyperreflexia or hyporeflexia, decreased sensation to light touch or pinprick, and decreased motor strength, can occur with soft tissue problems such as bursitis. However, clients with true nerve root irritation experience pain extending into the lower leg and foot. Clients with bursitis exhibit a positive “jump” sign when pressure is applied over the greater trochanter; no jump sign is seen with nerve root irritation.7

A common neuromuscular cause of anterior or anterolateral thigh pain is lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN) neuralgia. Entrapment or compression of the LFCN causes pain or dysesthesia, or both, in the anterolateral thigh—a condition called meralgia paresthetica. Compression of the LFCN may occur at the level of the L2 and L3 roots through upper lumbar disk herniation or tumor in the second lumbar vertebra. LFCN neuropathy may occur after spine surgery to repair nerve damage that occurred during harvesting of the iliac bone graft or that resulted from pressure on the pelvis from prone positioning or with use of the Relton-Hall frame.45

Other causes of injury to the LFCN include positioning during hip arthroplasty (at risk: obese individuals)46; abnormal posture; chronic muscle spasm; tight-fitting braces, corsets, or pants; and thigh injury.47 For clients with hip arthroplasty, implant loosening, fracture, or subsidence (sinking down into the bone) can cause thigh pain as the first symptom of instability.19 Both passive and active range of motion should be evaluated to assess implant stability. X-rays are needed to look at component position, bone–prosthesis interface, and signs of fracture or infection.16

Systemic Presentation: The pain pattern for anterior thigh pain produced by systemic causes is often the same as that presented for pain resulting from neuromusculoskeletal causes. The therapist must rely on clues from the history and the presence of associated signs and symptoms to help guide the decision-making process.

For example, obstruction, infection, inflammation, or compression of the ureters may cause a pattern of low back and flank pain that radiates anteriorly to the ipsilateral lower abdomen and upper thigh. The client usually has a past history of similar problems or additional urologic symptoms such as pain with urination, urinary frequency, low-grade fever, sweats, or blood in the urine. Murphy’s percussion test (see Fig. 4-54) may be positive when the kidney is involved.

The same pain pattern can occur with lower thoracic disk herniation. However, instead of urologic signs and symptoms, the therapist should look for a history of back pain and trauma and the presence of neurologic signs and symptoms accompanying diskogenic lesions.

Retroperitoneal or intraabdominal tumor or abscess may also cause anterior thigh pain. A past history of reproductive or abdominal cancer or the presence of any condition listed in Box 16-3 is a red flag.

Thigh pain has been reported as a prodromal symptom of unilateral low-energy subtrochanteric and femoral shaft (diaphyseal) stress reactions and fractures in a small number of people on long-term bisphosphonate therapy.48

Knee and Lower Leg

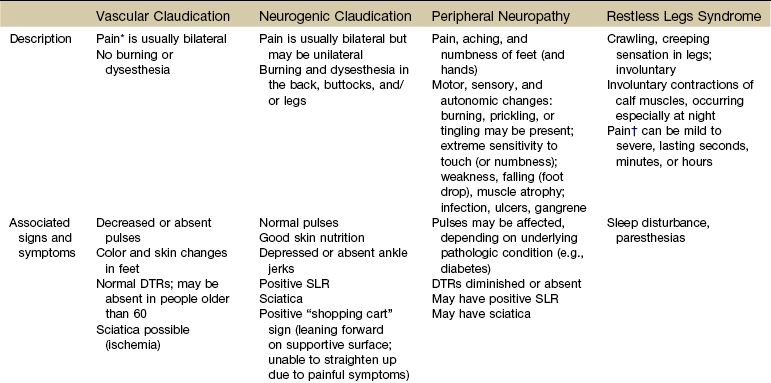

Pain in the lower leg is most often caused by injury, inflammation, tumor (malignant or benign), altered peripheral circulation, deep venous thrombosis (DVT), or neurologic impairment (Table 16-5). Assessment of limb pain follows the series of pain-related questions presented in Fig. 3-6. The therapist can use the information in Boxes 4-13 and 4-16 to conduct a screening examination.

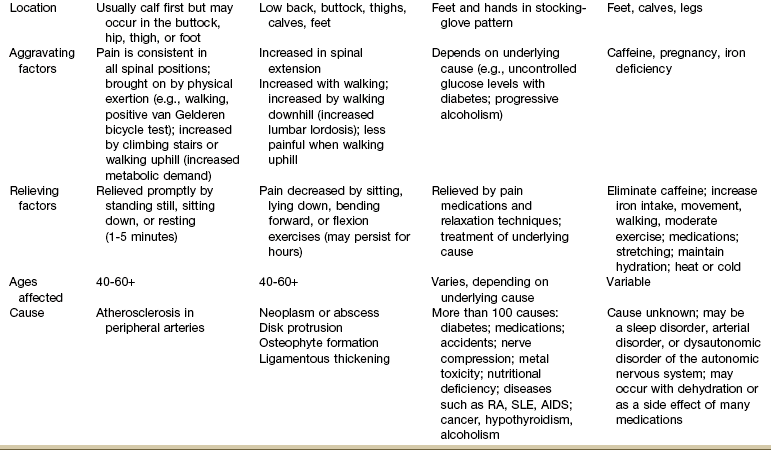

TABLE 16-5

Symptoms and Differentiation of Leg Pain

DTRs, Deep tendon reflexes; SLR, straight leg raise; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.

*“Pain” associated with vascular claudication may also be described as an “aching,” “cramping,” or “tired” feeling.

†“Pain” associated with restless legs syndrome may not be painful but may be described as a “frantic,” “unbearable,” or “compelling” need to move the legs.

Neuromusculoskeletal Presentation: In addition to screening for medical problems, the therapist must remember to clear the joint above and below the area of symptoms or dysfunction. True knee pain or symptoms are often described as mechanical (local pain and tenderness with locking or giving way of the lower leg) or loading (poorly localized pain with weight bearing).

There are many musculoskeletal or neuromuscular conditions well known to the therapist as a potential cause of generalized knee pain, including muscle spasm, strain, or tear; patellofemoral pain syndrome; tendinitis; ligamentous disruption, meniscal tear, or osteochondral lesion; stress fracture49; and nerve entrapment.50,51

Degenerative joint disease of the hip52 or other hip pathology can masquerade as knee pain in adults.53 Neurologic problems, including spinal stenosis, complex regional pain syndrome (Type 1), neurogenic claudication, and lumbar radiculopathy are common disorders that can produce knee pain. Isolated knee pain involving SI dysfunction has also been reported.54

Pain and impaired function from a variety of intraarticular or extraarticular etiologies can also develop following a total knee arthroplasty.55 Client history and clinical examination will help establish the diagnosis. Assessment of trigger points (TrPs) is also essential as pain referral to the knee from TrPs in the lower quadrant is well recognized but sometimes forgotten.56,57

Many therapists over the years have shared with us stories of clients treated for knee pain with a total knee replacement only to discover later (when the knee pain was unchanged) that the problem was really extraarticular (i.e., coming from the back or hip). On the flip side, it is not as likely but is still possible that hip pain can be caused by knee disease. Individual case reports of hip fracture presenting as isolated knee pain have been published58 (Case Example 16-7).

Systemic Presentation: Systemic or pathologic conditions presenting as generalized knee pain can include fractures, Baker’s cyst, tumors (benign or malignant), arthritis, infection, and/or DVT.50 Other types of cancer can also cause knee pain such as lymphoma, leukemia, and myeloma. Watch for unusual bleeding, easy bruising, unintentional weight loss, fatigue, fevers, worsening pain (duration and intensity), sweats, dyspnea, and lymphadenopathy.49

A history of trauma accompanied by persistent or worsening symptoms despite restricted loading of the area are typical with bone or soft tissue tumors. Night pain, localized swelling or warmth, locking, and palpable mass with any of the other symptoms listed raise the suspicion of bone or soft tissue tumor.59

Burning and pain in the legs and feet at night are common in older adults; this is also a potential side-effect of some chemotherapy drugs. The exact mechanism is often unknown; many factors should be considered, including allergic response to the fabric in clothing and socks, poorly fitting shoes, long-term alcohol use, adverse effects of medications, diabetes, pernicious anemia, and restless legs syndrome.

Leg cramps, especially those occurring in the lower leg and calf, are common in the adult population.60,61 Older adults, athletes, and pregnant women are at increased risk.62 The history and physical examination are key elements in identifying the cause. The most common causes of leg cramps include dehydration, arterial occlusion from peripheral vascular disease, neurogenic claudication from lumbar spinal stenosis,62 neuropathy, medications, metabolic disturbances, nutritional (vitamin, calcium) deficiency, and anterior compartment syndrome from trauma, hemophilia, sickle cell anemia, burns, casts, snakebites, or revascular perfusion injury.

Athletes often experience leg cramps preceded by muscle fatigue or twitching. Fractures and ligament tears can mimic a cramp. Cramping associated with severe dehydration may be a precursor to heat stroke.63

Heel pain is often a symptom of plantar fasciitis, heel spurs, nerve compression (e.g., tarsal tunnel syndrome), or stress fractures. Heel pain can also be a symptom of systemic conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), seronegative arthritides, primary bone tumors or metastatic disease, gout, sarcoidosis, Paget’s disease of the bone, inflammatory bowel disease, osteomyelitis, infectious diseases, sickle cell disease, and hyperparathyroidism.64

The resolution of heel pain of a musculoskeletal origin is variable and can take weeks to months. Knowing when to request additional diagnostic assessment is not always clear cut. The therapist must keep each potential systemic cause in mind when looking for clues in the client’s profile that might point to any one of these conditions.

For example, RA is more common between the third and fifth decades, affecting women 2 to  times more often than men. Ankylosing spondylitis usually affects the spine and SI joints first. Heel pain as a secondary symptom would be suspicious. Men are affected more often than women.

times more often than men. Ankylosing spondylitis usually affects the spine and SI joints first. Heel pain as a secondary symptom would be suspicious. Men are affected more often than women.

A history of inflammatory bowel disease (e.g., Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis) or cancer with new onset of ankle and/or heel pain must be evaluated medically. The calcaneus is the most common site of metastasis to the foot.65 Subdiaphragmatic disease (especially genitourinary or colorectal neoplasm) tends to metastasize to the feet,66 but cases of supradiaphragmatic disease, such as breast cancer metastasizing to the heel, have been reported.67 X-rays and blood tests will be needed to look for an inflammatory, infectious, or metastatic cause of heel pain.64

No matter what area of the lower quadrant is affected, asking about the presence of other signs and symptoms, conducting a Review of Systems, and identifying red-flag symptoms will help the therapist in the clinical decision-making process. The therapist can use the red flags (see Appendix A-2) to guide screening questions. Always ask every client the following:

If the client says, “No,” the therapist may want to ask some general screening questions, including questions about constitutional symptoms.

Failure to improve with physical therapy intervention may be part of the medical differential diagnosis and should be reported within a reasonable length of time, given the particular circumstances of each client.

Trauma as a Cause of Hip, Groin, or Lower Quadrant Pain

Trauma, including accidents, injuries, physical or sexual assault, or birth trauma, can be the underlying cause of buttock, hip, groin, or lower extremity pain.

Birth Trauma

Birth trauma is one possible cause of low back, pelvic, hip, or groin pain, with pain radiating down the leg in some cases. Multiple births, prolonged labor and delivery, forceps/vacuum delivery, and postepidural complications are just a few of the more common birth-related causes of hip, groin, and lower extremity pain. Gynecologic conditions are discussed more completely in Chapter 15.

Stress Reaction or Fracture

An undiagnosed stress reaction or stress fracture is a possible cause of hip, thigh, groin, knee, shin, heel, or foot pain. A stress reaction or fracture is a microscopic disruption, or break, in a bone that is not displaced; it is not seen initially on regular x-rays. Exercise-induced groin, tibial, or heel pain are the most common stress fractures.

There are two types of stress fractures. Insufficiency fractures are breaks in abnormal bone under normal force. Fatigue fractures are breaks in normal bone that has been put under extreme force. Fatigue fractures are usually caused by new, strenuous, very repetitive activities such as marching, jumping, or distance running.

Fatigue fractures are more likely in distance runners, sprinters,68 military recruits, or other high-intensity athletes affecting the pubic ramus, calcaneus, femoral neck, anterior tibia most often.69,70 Older adults are more likely to present with insufficiency hip fractures. Depending on the age of the client, the therapist should look for a history of high-energy trauma, prolonged activity, or abrupt increase in training intensity. Traction from attached muscles such as the adductor magnus on the inferior pubic ramus is a contributing factor to pubic ramus stress fractures.

Other risk factors include changes in running surface, use of inadequately cushioned footwear, and the presence of the female athlete triad of disordered eating, osteoporosis, amenorrhea, and menopause.71-73 Anything that can lead to poor bone density should be considered a risk factor for insufficiency stress fractures including radiation and/or chemotherapy,74 prolonged use of corticosteroids, renal failure, metabolic disorders affecting bone, Paget’s disease, and coxa vara.75,76 A smaller cross-sectional diameter of the long bones of the leg in male distance runners is a unique risk factor for tibial stress fractures.77

Femoral shaft stress fractures are rare in the general population but are not uncommon among distance runners and military recruits involved in repetitive loading activities such as running and marching. Pain presentation is not always predictable.75 Vague anterior thigh pain that radiates to the hip or knee with activity or exercise is the most common clinical presentation. The affected individual usually has full but painful active hip motion.78 The fulcrum test (Fig. 16-3) has high clinical correlation with femoral shaft stress injury.79

Fig. 16-3 Fulcrum test for femoral shaft stress reaction or fracture. With the client in a sitting position, the examiner places his or her forearm under the client’s thigh and applies downward pressure over the anterior aspect of the distal femur. A positive test is characterized by reproduction of thigh pain often described as “sharp,” with considerable apprehension on the part of the client.79

Likewise, heel pain from calcaneal fractures can occur in the athlete following significant increases in athletic activities or after a plantar fascia rupture. Posterior and plantar heel pain and swelling are often misdiagnosed as plantar fasciitis. A medial-lateral squeeze test may help identify the need for further imaging studies, especially when x-rays have been read as “normal.”80

Osteopenia or osteoporosis, especially in the postmenopausal woman or older adult with arthritis, can result in injury and fracture or fracture and injury (Case Example 16-8). The client has a small mishap, perhaps losing her footing on a slippery surface or tripping over an object. As she tries to “catch herself,” a torsional force occurs through the hip, causing a fracture and then a fall. This is a case of fracture then fall, rather than the other way around. Often, but not always, the client is unable to get up because of pain and instability of the fracture site.81,82

Pain on weight bearing is a red flag symptom for stress reaction or fracture in any individual. In the case of bone pain (deep pain, pain on weight bearing), the therapist can perform a heel strike test. This is done by applying a percussive force with the heel of the examiner’s hand through the heel of the client’s foot in a non–weight-bearing (supine) position. Reproduction of painful symptoms with axial loading is positive and highly suggestive of a bone fracture or stress reaction.83

The therapist can ask a physically capable client to hop on the uninvolved side and to do a full squat to clear the hip, knee, and ankle. These tests are used to screen for pubic ramus or hip stress fracture (reaction). Palpation over the injured bone may reproduce the painful symptoms, but when the stressed bone lies deep within the tissue, the therapist may be able to reproduce the pain by stressing the bone with translational (resisted active adduction) or rotational force (resisted active adduction combined with hip external rotation). Swelling is not usually evident early in the course of a stress reaction or fracture, but it does develop if the person continues athletic activity.

Look for the following clues suggestive of hip, groin, or thigh pain caused by a stress reaction or stress fracture.

Radiographs may not show the fracture, especially during its early stages.35 The therapist should also keep in mind that some fractures of the intertrochanteric region do not show up on standard anteroposterior or lateral x-ray. An oblique view may be needed. If an x-ray has been ruled negative for hip fracture but the client cannot put weight on that side and a heel strike test is positive, communication with the physician may be warranted.

Assault

The client may not report assault as the underlying cause, or he or she may not remember any specific trauma or accident. It may be necessary to take a sexual history (see Appendix B-32) that includes specific questions about sexual activity (e.g., incest, partner assault or rape) or the presence of sexually transmitted infection. Appropriate screening questions for assault or domestic violence are included in Chapter 2; see also Appendix B-3.

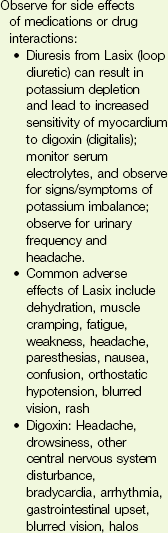

Screening for Systemic Causes of Sciatica

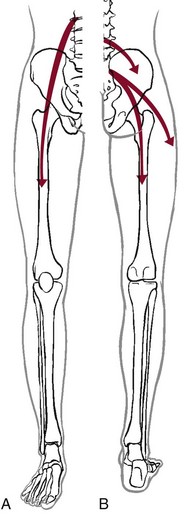

Sciatica, described as pain radiating down the leg below the knee along the distribution of the sciatic nerve, is usually related to mechanical pressure or inflammation of lumbosacral nerve roots (Fig. 16-4). Sciatica is the term commonly used to describe pain in a sciatic distribution without overt signs of radiculopathy.

Fig. 16-4 Sciatica pain pattern. Perceived or reported pain associated with compression, stretch, injury, entrapment, or scarring of the sciatic nerve depends on the location of the lesion in relation to the nerve root. The sciatic nerve is innervated by L4, L5, S1, S2, and sometimes S3 with several divisions (e.g., common fibular [peroneal] nerve, sural nerve, tibial nerve).

Radiculopathy denotes objective signs of nerve (or nerve root) irritation or dysfunction, usually resulting from involvement of the spine. Symptoms of radiculopathy may include weakness, numbness, or reflex changes. Sciatic neuropathy suggests damage to the peripheral nerve beyond the effects of compression, often resulting from a lesion outside the spine that affects the sciatic nerve (e.g., ischemia, inflammation, infection, direct trauma to the nerve, compression by neoplasm or piriformis muscle).

The terms radiculopathy, sciatica, and neuropathy are often used interchangeably, although there is a pathologic difference.84 Electrodiagnostic studies, including nerve conduction studies (NCS), electromyography (EMG), and somatosensory evoked potential studies (SSEPs), are used to make the differentiation.

Sciatica has many neuromuscular causes, both diskogenic and nondiskogenic; systemic or extraspinal conditions can produce or mimic sciatica (Table 16-6). Risk factors for a mechanical cause of sciatica include previous trauma to the low back, taller height, tobacco use, pregnancy, and work- and occupational-related posture or movement.85

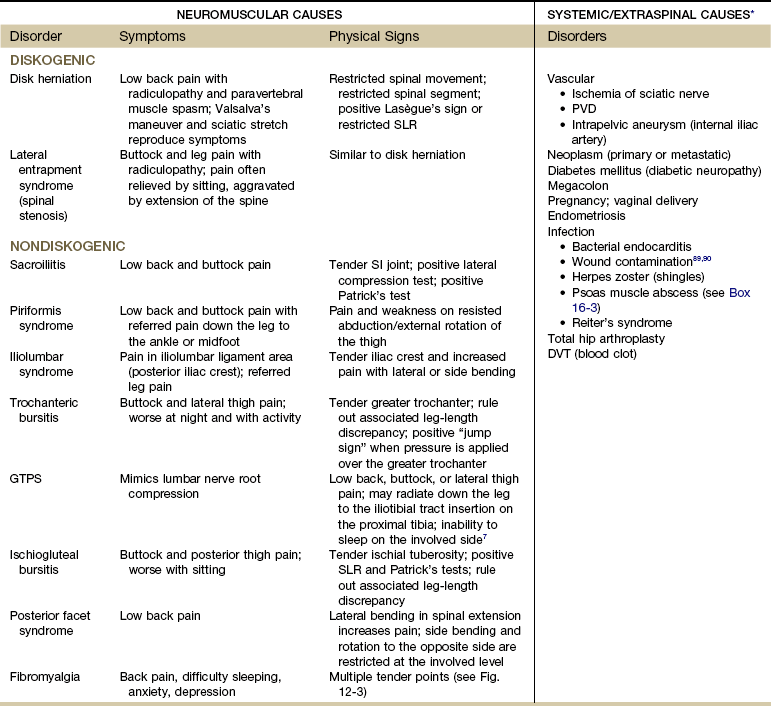

TABLE 16-6

SLR, Straight leg raise; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; SI, sacroiliac; DVT, deep venous thrombosis; GTPS, greater trochanteric pain syndrome.

*Clinical symptoms of systemic/extraspinal sciatica can be very similar to those of sciatica associated with disk protrusion.

Data from Namey TC, An HC: Sorting out the causes of sciatica, Mod Med 52:132, 1984.

Risk Factors

Risk factors for systemic or extraspinal causes vary with each condition (Table 16-7). For example, clients with arterial insufficiency are more likely to be heavy smokers and to have a history of atherosclerosis. Increasing age, past history of cancer, and comorbidities, such as diabetes mellitus, endometriosis, or intraperitoneal inflammatory disease (e.g., diverticulitis, Crohn’s disease, pelvic inflammatory disease), are risk factors associated with sciatic-like symptoms (Case Example 16-9).

Total hip arthroplasty is a common cause of sciatica because of the proximity of the nerve to the hip joint. Possible mechanisms for nerve injury include stretching, direct trauma from retractors, infarction, hemorrhage, hip dislocation, and compression.86 Sciatica referred to as sciatic nerve “burn” has been reported as a complication of hip arthroplasty caused by cement extrusion. The incidence of this complication has decreased with its increased recognition and the increasing use of cementless implants,19 but even small amounts of cement can cause heat production or direct irritation of the sciatic nerve.87

Propionibacterium acnes, a cause of spinal infection, has been linked to sciatica.88 Bacterial wound contamination during spinal surgery has been traced to this pathogen on the patient’s skin. Minor trauma to the disk with a breach to the mechanical integrity of the disk may also allow access by low virulent microorganisms, thereby initiating or stimulating a chronic inflammatory response. These microorganisms may cause prosthetic hip infection but also may be associated with the inflammation seen in sciatica; they may even be a primary cause of sciatica.89,90

Endometriosis at the sciatic notch and pelvic endometriosis affecting the lumbosacral plexus or proximal sciatic nerve can present as sciatica/buttock pain that extends down the posterior aspect of the thigh and calf to the ankle. The pain is cyclic and corresponds with the menstrual cycle.91,92

Anyone with pain radiating from the back down the leg as far as the ankle has a greater chance that disk herniation is the cause of low back pain. This is true with or without neurologic findings. Unremitting, severe pain and increasing neurologic deficit are red-flag findings. Sciatica caused by extraspinal bone and soft tissue tumors is rare but may occur when a mass is present in the pelvis, sacrum, thigh, popliteal fossa, and calf.93,94

The therapist can conduct an examination to look for signs and symptoms associated with systemically induced sciatica. Box 4-13 offers guidelines on conducting an assessment for peripheral vascular disease. Box 4-16 provides a checklist for the therapist to use when examining the extremities. These tools can help the therapist define the clinical presentation more accurately.

The SLR test and other neurodynamic tests are widely used but do not identify the underlying cause of sciatica. For example, a positive SLR test does not differentiate between diskogenic disease and neoplasm.

Without a combination of imaging and laboratory studies, the clinical picture of sciatica is difficult to distinguish from that of conditions such as neoplasm and infection. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR or sed rate) is the rate at which red blood cells settle out of unclotted blood plasma within 1 hour. A high ESR is an indication of infection or inflammation (see top table, Inside Front Cover). Elevated ESR and abnormal imaging are effective tools to use in screening for occult neoplasm and other systemic disease.95

Imaging studies are an essential part of the medical diagnosis, but even with these diagnostic tests, errors in conducting and interpreting imaging studies may occur. Symptoms can also result from involvement outside the area captured on computed tomography (CT) scan or MRI.

Screening for Oncologic Causes of Lower Quadrant Pain

Many clients with orthopedic or neurologic problems have a previous history of cancer. The therapist must recognize signs and symptoms of cancer recurrence and those associated with cancer treatment such as radiation therapy or chemotherapy. The effects of these may be delayed by as long as 10 to 20 years or more (see Table 13-8; Case Example 16-10).

Until now, the emphasis has been on advancing age as a key red flag for cancer. Anyone older than 50 years of age may need to be screened for systemic origin of symptoms. With cancer and specifically, musculoskeletal pain caused by primary cancer or metastases to the bone, young age is a red flag as well. Primary bone cancer occurs most often in adolescents and young adults, hence the new red flag: age younger than 20 years, or bone pain in an adolescent or young adult.

Cancer Recurrence

The therapist is far more likely to encounter clinical manifestations of metastases from cancer recurrence than from primary cancer. Breast cancer often affects the shoulder, thoracic vertebrae, and hip first, before other areas. Recurrence of colon (colorectal) cancer is possible with referred pain to the hip and/or groin area.

Beware of any client with a past history of colorectal cancer and recent (past 6 months) treatment by surgical removal. Reseeding the abdominal cavity is possible. Every effort is made to shrink the tumor with radiation or chemotherapy before attempts are made to remove the tumor. Even a small number of tumor cells left behind or introduced into a nearby (new) area can result in cancer recurrence.

Hodgkin’s Disease

Hodgkin’s disease arises in the lymph glands, most commonly on a single side of the neck or groin, but lymph nodes also enlarge in response to infection throughout the body. Lymph nodes in the groin area can become enlarged specifically as a result of sexually transmitted disease.

The presence of painless, hard lymph nodes that are also similarly present at other sites (e.g., popliteal space) is always a red-flag symptom. As always, the therapist must question the client further regarding the onset of symptoms and the presence of any associated symptoms, such as fever, weight loss, bleeding, and skin lesions. The client must seek a medical diagnosis to be certain of the cause of enlarged lymph nodes.

Spinal Cord Tumors

Spinal cord tumors (primary or metastasized) present as dull, aching discomfort or sharp pain in the thoracolumbar area in a beltlike distribution, with pain extending to the groin or legs. Depending on the location of the lesion, symptoms may be unilateral or bilateral with or without radicular symptoms. The therapist should look for and ask about associated signs and symptoms (e.g., constitutional symptoms, bleeding or discharge, lymphadenopathy).

Symptoms of thoracic disk herniation can mimic spinal cord tumor. In isolated cases, thoracic disk extrusion has been reported to cause groin pain and lower extremity weakness that gets progressively worse over time. A tumor is suspected if the client has painless neurologic deficit, night pain, or pain that increases when supine.

Testing the cremasteric reflex may help the therapist identify neurologic impairment in any male with suspicious back, pelvic, groin (including testicular), or anterior thigh pain. The cremasteric reflex is elicited by stroking the thigh downward with a cotton-tipped applicator (or handle of the reflex hammer). A normal response in males is upward movement of the testicle (scrotum) on the same side. The absence of a cremasteric reflex is an indication of disruption at the T12-L1 level.

Additionally, groin pain associated with spinal cord tumor is disproportionate to that normally expected with disk disease. No change in symptoms occurs after successful surgery for herniated disk. Age is an important factor: teenagers with symptoms of disk herniation should be examined closely for tumor.96,97

Spinal metastases to the femur or lower pelvis may appear as hip pain. With the exception of myeloma and rare lymphoma, metastasis to the synovium is unusual. Therefore joint motion is not compromised by these bone lesions. Although any tumor of the bone may appear at the hip, some benign and malignant neoplasms have a propensity to occur at this location.

Bone Tumors

Osteoid osteoma, a small, benign but painful tumor, is relatively common, with 20% of lesions occurring in the proximal femur and 10% in the pelvis. The client is usually in the second decade of life and complains of chronic dull hip, thigh, or knee pain that is worse at night and is alleviated by activity and aspirin and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Usually, an antalgic gait is present, along with point tenderness over the lesion with restriction of hip motion.

A great many varieties of benign and malignant tumors may appear differently, depending on the age of the client and the site and duration of the lesion (Case Example 16-11).98,99 Malignant lesions compressing the LFCN can cause symptoms of meralgia paresthetica, delaying diagnosis of the underlying neoplasm. Other bone tumors that cause hip pain, such as chondroblastoma, chondrosarcoma, giant cell tumor, and Ewing’s sarcoma, are discussed in greater detail in Chapter 13.

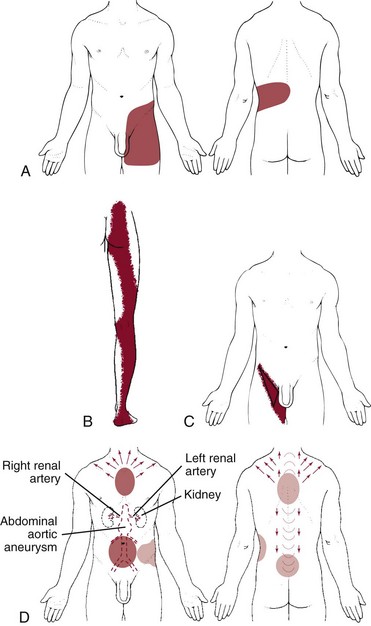

Screening for Urologic Causes of Buttock, Hip, Groin, or Thigh Pain

Ureteral pain usually begins posteriorly in the costovertebral angle but may radiate anteriorly to the upper thigh and groin (see Fig. 16-6), or it may be felt just in the groin and genital area. These pain patterns represent the pathway that genitals take as they migrate during fetal development from their original position, where the kidneys are located in the adult, down the pathways of the ureters to their final location. Pain is referred to a site where the organ was located during fetal development. A kidney stone down the pathway of the ureters causes pain in the flank that radiates to the scrotum (male) or labia (female).

The lower thoracic and upper lumbar vertebrae and the SI joint can refer pain to the groin and anterior thigh in the same pain pattern as occurs with renal disease. Irritation of the T10-L1 sensory nerve roots (genitofemoral and ilioinguinal nerves) from any cause, especially from diskogenic disease, may cause labial (women), testicular (men), or buttock pain.100 The therapist can evaluate these conditions by conducting a neurologic screening examination and using the screening model.

Referred symptoms from ureteral colic can be distinguished from musculoskeletal hip pain by the history, the presence of urologic symptoms, and the pattern of pain. Is there any history of urinary tract impairment? Is there a recent history of other infection? Are any signs and symptoms noted that are associated with the renal system?

Active TrPs along the upper rim of the pubis and the lateral half of the inguinal ligament may lie in the lower internal oblique muscle and possibly in the lower rectus abdominis. These TrPs can cause increased irritability and spasm of the detrusor and urinary sphincter muscles, producing urinary frequency, retention of urine, and groin pain.57

The therapist can perform Murphy’s percussion test to rule out kidney involvement (see Chapter 10; see also Fig. 4-54). A positive Murphy’s percussion test (pain is reproduced with percussive vibration of the kidney) points to the possibility of kidney infection or inflammation. When this test is positive, ask about a recent history of fever, chills, unexplained perspiration (“sweats”), or other constitutional symptoms.

Screening for Male Reproductive Causes of Groin Pain

Men can experience groin pain caused by disease of the male reproductive system such as prostate cancer, testicular cancer, benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), or prostatitis. Isolated groin pain is not as common as groin pain that is accompanied by low back, buttock, or pelvic pain. Risk factors, clinical presentation, and associated signs and symptoms for these conditions are discussed in Chapter 14.

Screening for Infectious and Inflammatory Causes of Lower Quadrant Pain

Anyone with joint pain of unknown cause who presents with current or recent (i.e., within the past 6 weeks) skin rash or recent history of infection (e.g., hepatitis, mononucleosis, urinary tract infection, upper respiratory infection, sexually transmitted infection, streptococcus, dental infection)101,102 must be referred to a health care clinic or medical doctor for further evaluation.

Conditions affecting the entire peritoneal cavity such as pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) or appendicitis may cause hip or groin pain in the young, healthy adult. Widespread inflammation or infection may be well tolerated by athletes, sometimes for up to several weeks (Case Example 16-12).

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation can be deceptive in young people. The fever is not dramatic and may come and go. The athlete may dismiss excessive or unusual perspiration (“sweats”) as part of a good workout. Loss of appetite associated with systemic disease is often welcomed by teenagers and young adults and is not recognized as a sign of physiologic distress.

With an infectious or inflammatory process, laboratory tests may reveal an elevated ESR. Questions about the presence of any other symptoms may reveal constitutional symptoms such as elevated nocturnal temperature, sweats, and chills, suggestive of an inflammatory process (Case Example 16-13).

Psoas Abscess

Any infectious or inflammatory process affecting the abdominal or pelvic region can lead to psoas abscess and irritation of the psoas muscle. For example, lesions outside the ureter, such as infection, abscess, or tumor, or abdominal or peritoneal inflammation, may cause pain on movement of the adjacent iliopsoas muscle that presents as hip or groin pain. (See discussion of Psoas Abscess in Chapter 10.)

PID is another common cause of pelvic, groin, or hip pain that can cause psoas abscess and a subsequent positive iliopsoas or obturator test. In this case, it is most likely a young woman with multiple sexual partners who has a known or unknown case of untreated Chlamydia.

The psoas muscle is not separated from the abdominal or pelvic cavity. Fig. 8-3 shows how most of the viscera in the abdominal and pelvic cavities can come into contact with the iliopsoas muscle. Any infectious or inflammatory process (see Box 16-3) can seed itself to the psoas muscle by direct extension, resulting in a psoas abscess—a localized collection of pus.

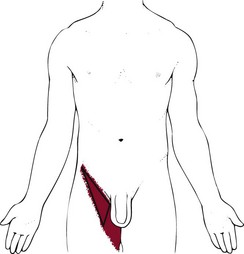

Hip pain associated with such an abscess may involve the medial aspect of the thigh and femoral triangle areas (Fig. 16-5). Soft tissue abscess may cause pain and tenderness to palpation without movement. Once the abscess has formed, muscular spasm may be provoked, producing hip flexion and even contracture. The leg also may be pulled into internal rotation. Pain that increases with passive and active motion can occur when infected tissue is irritated. Pain elicited by stretching the psoas muscle through extension of the hip, called the positive psoas sign, may be present.

Fig. 16-5 Femoral triangle: Referred pain pattern from psoas abscess. Hip pain associated with such an abscess may involve the medial aspect of the thigh and femoral triangle areas. The femoral triangle is the name given to the anterior aspect of the thigh formed as different muscles and ligaments cross each other, producing an inverted triangular shape.

A positive response for any of these tests is indicative of an infectious or inflammatory process. Direct back, pelvic, or hip pain that results from these palpations is more likely to have a musculoskeletal cause. Besides the iliopsoas and obturator tests, another test for rebound tenderness used more often is the pinch-an-inch test (see Fig. 8-11). It may be appropriate to conduct these tests with a variety of clinical presentations involving the pelvic area, sacrum, hip, or groin.

Psoas abscess must be differentiated from TrPs of the psoas muscle, causing the psoas minor syndrome, which is easily mistaken for appendicitis. Hemorrhage within the psoas muscle, either spontaneous or associated with anticoagulation therapy for hemophilia, can cause a painful compression syndrome of the femoral nerve.

Systemic causes of hip pain from psoas abscess are usually associated with loss of appetite or other GI symptoms, fever, and sweats. Symptoms from an iliopsoas trigger point are aggravated by weight-bearing activities and are relieved by recumbency or rest. Relief is greater when the hip is flexed.57

Screening for Gastrointestinal Causes of Lower Quadrant Pain

The relationship of the gut to the joint is well known but poorly understood. Intestinal bypass syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, ankylosing spondylitis, celiac disease, postdysenteric reactive arthritis, bowel bypass syndrome, and antibiotic-associated colitis all share the fact that some “interface” exists between the bowel and the hip articular surface. It is possible that the clinical expression of immune-mediated joint disease results from an immunologic response to an antigen that crosses the gut mucosa with an autoimmune response against self.103-110

For the client with hip pain of unknown cause or suspicious presentation, ask whether any back pain or abdominal pain is ever present. Alternating abdominal pain with low back pain at the same level, or alternating abdominal pain with hip pain is a red flag that requires medical referral.

The therapist may treat a patient with joint or back pain with an underlying enteric cause before he or she realizes what the underlying problem is. Palliative intervention can make a difference in the short term but does not affect the final outcome. Symptoms that are unrelieved by physical therapy intervention are always a red flag. Symptoms that improve after physical therapy but then get worse again are also a red flag, revealing the need for further screening.

In the case of enterically induced joint pain, the client will get worse without medical intervention. Without early identification and referral, the client will eventually return to his or her gastroenterologist or primary care physician. Medical treatment for the underlying disease is essential in affecting the musculoskeletal component. Physical therapy intervention does not alter or improve the underlying enteric disease. It is better for the client if the therapist recognizes as soon as possible the need for medical intervention.

Crohn’s Disease

In anyone with hip or groin pain of unknown cause, look for a known history of PID, Crohn’s disease (regional enteritis), ulcerative colitis, irritable bowel syndrome, diverticulitis, or bowel obstruction.

It is possible that new onset of low back, sacral, buttock, or hip pain is merely a new symptom of an already established enteric (GI) disease. Twenty-five percent of those with inflammatory enteric disease (particularly Crohn’s disease) have concomitant back or joint pain that are symptoms of spondyloarthritis/spondyloarthropathy.

A skin rash that comes and goes can accompany enterically induced arthritis. A flat rash or raised skin lesion of the lower extremities is possible; it usually precedes joint or back pain. Be sure to ask the client whether he or she has had skin rashes of any kind over the past few weeks.

Several tests can be done to assess for hip pain resulting from psoas abscess caused by abdominal or intraperitoneal infection or inflammation. These were discussed in the previous section.

A positive response for each of these tests is NOT a reproduction of the client’s hip or groin pain, but rather, lower quadrant abdominal pain on the side of the test. This is a symptom of an infectious or inflammatory process. Hip or back pain in response to these tests is more likely musculoskeletal in origin such as a trigger point of the iliopsoas or muscular tightness.

Reactive Arthritis

In the case of reactive arthritis, joint symptoms occur 1 to 4 weeks after an infection, usually GI or genitourinary (GU).110 The joint is not septic (infected), but rather, it is aseptic (without infection). Affected joints often occur at a site that is remote from the primary infection. Prosthetic joints are not immune to this type of infection and may become infected years after the joint is implanted.

Whether the infection occurs in the natural joint or in the prosthetic implant, the client is unable to bear weight on the joint. An acute arthritic presentation may occur, and the client often has a fever (commonly of low grade in older adults or in anyone who is immunosuppressed). Screening questions for clients with joint pain are listed in Box 3-5 and in Appendix B-18. These questions may be helpful for the client with joint pain of unknown cause or with an unusual presentation/history that does not fit the expected pattern for injury, overuse, or aging.

Screening for Vascular Causes of Lower Quadrant Pain

Vascular pain is often throbbing in nature and exacerbated by activity. With atherosclerosis, a lag time of 5 to 10 minutes occurs between when the body asks for increased oxygenated blood and when symptoms occur because of arterial occlusion. The client is older, often with a personal or family history of heart disease. Other risk factors include hyperlipidemia, tobacco use, and diabetes.

Peripheral Vascular Disease

Peripheral vascular disease (PVD), also known as peripheral arterial disease (PAD) or arterial insufficiency, in which the arteries are occluded by atherosclerosis, can cause unilateral or bilateral low back, hip, buttock, groin, or leg pain, along with intermittent claudication and trophic changes of the affected lower extremities.

Intermittent claudication of vascular origin may begin in the calf and may gradually make its way up the lower extremity. The client may report the pain or discomfort as “burning,” “cramping,” or “sharp.” Pain or other symptoms begin several minutes after the start of physical activity and resolve almost immediately with rest. As discussed in Chapter 14, the site of symptoms is determined by the location of the pathology (see Fig. 14-3) (Case Example 16-14).

PVD is a rare cause of lower quadrant pain in anyone under the age of 65, but leg pain in recreational athletes caused by isolated areas of arterial stenosis has been reported.111

The therapist must include assessment of vital signs and must look for trophic skin changes so often present with chronic arterial insufficiency. Pulse oximetry may be helpful when thrombosis is not clinically obvious; for example, pulses can be present in both feet with oxygen saturation (SaO2) levels at 90% or less.112 When assessing for PVD as a possible cause of back, buttock, hip, groin, or leg pain, look for other signs of PVD. See further discussion of this topic in Chapters 4, 6, and 14.

DVT as a cause of lower leg pain may present as loss of knee or ankle motion, swelling of the knee, calf, or ankle, with calf tenderness and erythema. There can be increased local skin temperature, local edema, and decreased distal pulses in the lower extremity.51 Further discussion and information on assessment of DVT are presented in Chapters 4 and 6.

Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) may be asymptomatic; discovery occurs on physical or x-ray examination of the abdomen or lower spine for some other reason. The most common symptom is awareness of a pulsating mass in the abdomen, with or without pain, followed by abdominal and back pain. Groin pain and flank pain may occur because of increasing pressure on other structures. (For more detailed information, see Chapter 6.)

Be aware of the client’s age. The client with an AAA can be of any age because this may be a congenital condition, but usually, he or she is over age 50 and more likely, is 65 or older. The condition remains asymptomatic until the wall of the aorta grows large enough to rupture. If that happens, blood in the abdomen causes searing pain accompanied by a sudden drop in blood pressure. Other symptoms of impending rupture or actual rupture of the aortic aneurysm include the following:

• Rapid onset of severe groin pain (usually accompanied by abdominal or back pain)

• Radiation of pain to the abdomen or to posterior thighs

• Pain not relieved by change in position

An increasingly prevalent risk factor in the aging adult population is initiation of a weight-lifting program without prior medical evaluation or approval. The presence of atherosclerosis, elevated blood pressure, or an unknown aneurysm during weight training can precipitate rupture.

The therapist can palpate the aortic pulse to identify a widening pulse width, which is suggestive of an aneurysm (see Fig. 4-55). Place one hand or one finger on either side of the aorta as shown. Press firmly deep into the upper abdomen just to the left of midline. You should feel aortic pulsations. These pulsations are easier to appreciate in a thin person and are more difficult to feel in someone with a thick abdominal wall or a large anteroposterior diameter of the abdomen.

Obesity and abdominal ascites or distention make this more difficult. For therapists who are trained in auscultation, listen for bruits. Bruits are abnormal blowing or swishing sounds heard on auscultation of the arteries. Bruits with both systolic and diastolic components suggest the turbulent blood flow of partial arterial occlusion. If the renal artery is occluded as well, the client will be hypertensive.

Avascular Osteonecrosis

Avascular osteonecrosis (also known as osteonecrosis or septic necrosis) can occur without known cause but is often associated with trauma (e.g., hip dislocation or fracture), as well as various other nontraumatic risk factors.113 Chronic use and abuse of alcohol is a common risk factor for this condition. Screening for alcohol or drug use and abuse is discussed in Chapter 2 (see also Appendices B-1 and B-2).

Osteonecrosis is also associated with many other conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus, pancreatitis, kidney disease, blood disorders (e.g., sickle cell disease, coagulopathies, leukemia), diabetes mellitus, Cushing’s disease, and gout. Long-term use of corticosteroids or immunosuppressants or use of medications for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), or any condition that causes immune deficiency, can also result in osteonecrosis.113 Other individuals who are taking immunosuppressants include organ transplant recipients, clients with cancer, and those with RA or another chronic autoimmune disease.114

The femoral head is the most common site of this disorder. Bones with limited blood supply are at enhanced risk for this condition. Hip dislocation or fracture of the neck of the femur may compromise the already precarious vascular supply to the head of the femur. Ischemia leads to poor repair processes and delayed healing. Necrosis and deformation of the bone occur next.

The client may be asymptomatic during the early stages of osteonecrosis. Hip pain is the first symptom. At first, it may be mild, lasting for weeks. As the condition progresses, symptoms become more severe, with pain on weight bearing, antalgic gait, and limited motion (especially internal rotation, flexion, and abduction). The client may report a distinct click in the hip when moving from the sitting position and increased stiffness in the hip as time goes by.

Screening for other Causes of Lower Quadrant Pain

Osteoporosis may result in hip fracture and accompanying hip pain, especially in postmenopausal women who are not taking hormone replacement. Osteoporosis accompanying the postmenopausal period—when combined with circulatory impairment, postural hypotension, or some medications—may increase a person’s risk of falling and incurring hip fracture.

Transient osteoporosis of the hip can occur during third-trimester pregnancy, although the incidence is fairly low. There have been reports (rare) of transient osteoporosis in nonpregnant women, children, adolescents, and men as well.115 Symptoms include spontaneous acute and progressive hip pain. In some cases, pain is referred to the lateral thigh and severe enough to result in an antalgic gait (limp). There is usually minimal night discomfort. Hip range-of-motion is usually spared though the individual may report pain at the end of internal rotation. Often, the pain subsides in 6 to 8 weeks; this corresponds with resolution of bone edema. During pregnancy, the pain develops shortly before or during the last trimester and is aggravated by weight bearing. There is a classic left-sided predominance seen in pregnant women that is not present in nonpregnant individuals. The pain subsides, and the x-ray appearance returns to normal within several months after delivery.115,116

The natural history in nonpregnant individuals is for spontaneous regression and recovery within 6 to 9 months with no permanent problems. X-rays are often normal at presentation but later show progressive osteoporosis of the femoral head (and sometimes the femoral neck and acetabulum).115

Any evaluation procedures that produce significant shear through the femoral head of a pregnant woman must be performed by the physical therapist with extreme caution. The transient osteoporosis of pregnancy is not limited to the hip, and vertebral compression may also occur.

Extrapulmonary Tuberculosis

Tubercular disease of the hip or spine is rare in developed countries, but it may occur as an opportunistic disease associated with AIDS that causes hip or back pain. Usually, the diagnosis of AIDS and tuberculosis is known, which alerts the therapist about the underlying systemic cause.

With hip involvement, the client usually appears with a chronic limp and describes pain in the hip that persists at rest. Approximately 60% of affected individuals do not have constitutional symptoms, although the tuberculin skin test is usually positive, and radiographs are similar to those for septic arthritis.

Sickle Cell Anemia and Hemophilia

Sickle cell anemia resulting in avascular necrosis (death of cells caused by lack of blood supply) of the hip and hemarthrosis (blood in the joint) associated with hemophilia are two of the most common hematologic diseases that cause pain in the hip, groin, knee, or leg.

Hemophilia may involve GI bleeding accompanied by low abdominal, hip, or groin pain caused by bleeding into the wall of the large intestine or the iliopsoas muscle. This retroperitoneal hemorrhage produces a muscle spasm of the iliopsoas muscle. The subsequent bleeding–spasm cycle produces increased hip pain and hip flexion spasm or contracture. Other symptoms may include melena, hematemesis, and fever.

Liver (Hepatic) Disease

Tarsal tunnel syndrome characterized by pain around the ankle that extends to the plantar surfaces of the toes possibly made worse by walking may be the result of tibial nerve compression from any space-occupying lesion. Causes of compression include a history of trauma (nonunion or displaced fracture), varicosities, lipomas, ganglion cysts, or tumors.117

Additional symptoms can include burning pain and numbness on the plantar surface of the foot. Similar symptoms misinterpreted as tarsal tunnel syndrome can occur with neuropathy associated with diabetes mellitus and/or alcoholism. Tinel’s sign (reproduction of characteristic pain or tingling with tapping or compression of the tibial nerve) may be positive but does not differentiate between a musculoskeletal cause versus systemic origin of symptoms.118

Ascites is an abnormal accumulation of serous (edematous) fluid in the peritoneal cavity; this fluid contains large quantities of protein and electrolytes as the result of portal backup and loss of proteins (see Fig. 9-8). This condition is associated with liver disease and alcoholism. For the physical therapist, the distended abdomen, abdominal hernias, and lumbar lordosis observed in clients with ascites may present musculoskeletal symptoms such as groin or low back pain.

The presence of ascites as it is linked with groin pain would be physically evident. If abdominal distention is present, then the therapist should ask about a past medical history of liver impairment, chronic alcohol use, and the presence of carpal or tarsal tunnel syndrome associated with liver impairment. The therapist can carry out the four screening tests for liver impairment discussed in Chapter 9, including the following:

Physician Referral

Guidelines for Immediate Medical Attention

• Painless, progressive enlargement of lymph nodes, or lymph nodes that are suspicious for any reason and that persist or that involve more than one area (groin and popliteal areas); immediate medical referral is required for a client with a past medical history of cancer

• Hip or groin pain alternating or occurring simultaneously with abdominal pain at the same level (Aneurysm, colorectal cancer)

• Hip or leg pain on weight bearing with positive tests for stress reaction or fracture

Guidelines for Physician Referral

• Hip, thigh, or buttock pain in a client with a total hip arthroplasty that is brought on by activity but resolves with continued activity (Loose prosthesis), or who has persistent pain that is unrelieved by rest (Implant infection)

• Sciatica accompanied by extreme motor weakness, numbness in the groin or rectum, or difficulty controlling bowel or bladder function

• One or more of Cyriax’s Signs of the Buttock (see Box 16-2)

• New onset of joint pain in a client with a known history of Crohn’s disease, requiring careful screening and possible referral based on examination results

Clues to Screening Lower Quadrant Pain

• See also Clues to Screening Head, Neck, or Back Pain; general concepts from the back also apply to the hip and the groin (see especially the discussion on Cardiovascular)

• Client does not respond to physical therapy intervention or gets worse, especially in the presence of a past medical history of cancer or an unknown cause of symptoms

Past Medical History