Cardiovascular Disorders

Blood pressure is the force against the walls of the arteries and arterioles as these vessels carry blood away from the heart. When these muscular walls constrict, reducing the diameter of the vessel, BP rises; when they relax, increasing the vessel diameter, BP falls (see also section on Blood Pressure in Chapter 4).

A high BP reading is usually a sign that the vessels cannot relax fully and remain somewhat constricted, requiring the heart to work harder to pump blood through the vessels. Over time the extra effort can cause the heart muscle to become enlarged and eventually weakened. The force of blood pumped at high pressure can also produce small tears in the lining of the arteries, weakening the arterial vessels. The evidence of this effect is most pronounced in the vessels of the brain, the kidneys, and the small vessels of the eye.

Hypertension is a major cardiovascular risk factor, associated with elevated risks of cardiovascular diseases, especially MI, stroke, PVD, and cardiovascular death. Although diastolic changes were always evaluated closely, research now shows that the risks increase progressively as systolic pressure goes up, especially in adults over age 50.82,83

Hypertension is often considered in conjunction with peripheral vascular disorders for several reasons: both are disorders of the circulatory system, the course of both diseases are affected by similar factors, and hypertension is a major risk factor in atherosclerosis, the largest single cause of PVD.

Hypertension is defined by a pattern of consistently elevated diastolic pressure, systolic pressure, or both measured over a period of time, usually several months. Medical researchers have developed classifications for BP based on risk (see Table 4-5).

The guidelines were updated in 2003 by the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of Hypertension (Case Example 6-9).84 Preliminary recommendations for a “new definition” of hypertension were issued in 2005 by the American Society of Hypertension.85

The new proposed definition/classification is based on the idea that hypertension is a complex cardiovascular disorder, not a scale of BP values. The new definition takes into account risk factors, early disease markers, and attempts to reflect the effects of hypertension on other organ systems. The goal of this risk-based approach is to identify individuals at any level of BP who have a reasonable likelihood of future cardiovascular events.85

Simply stated the new guidelines emphasize the continuous relationship between BP level and cardiovascular risk. The BP classification scale used for diagnosis and treatment is based on total cardiovascular risk, not just BP values. So for example, an individual with BP values of 140/90 mm Hg (defined as Stage I or borderline hypertension) may not begin medical therapy in the absence of other risk factors. On the other hand, someone with much lower BP values (e.g., 120/75 mm Hg) might be treated immediately if other risk factors are present such as overweight or tobacco use.85

Blood Pressure Classification

Hypertension can also be classified according to type (systolic or diastolic), cause, and degree of severity. Primary (or essential) hypertension is also known as idiopathic hypertension and accounts for 90% to 95% of all hypertensive clients.

Secondary hypertension results from an identifiable cause, including a variety of specific diseases or problems such as renal artery stenosis, oral contraceptive use, hyperthyroidism, adrenal tumors, and medication use.

Originally, birth control pills contained higher levels of estrogen, which was associated with hypertension, but today the estrogen and progestin contents of the pill are greatly reduced. The risk of high BP with oral contraceptive use is now considered quite low, but using oral contraceptives does still increase the risk of heart attack, stroke, and blood clots in certain women (e.g., age over 35, tobacco use, diabetes).

The risk may be increased for older women who smoke, but the risk for all women returns to normal after they discontinue the pill. The risk of venous thromboembolism associated with newer oral contraceptives remains under investigation.

Drugs that constrict blood vessels can contribute to hypertension. Among the most common are phenylpropanolamine in over-the-counter (OTC) appetite suppressants, including herbal ephedra, pseudoephedrine in cold and allergy remedies, and prescription drugs such as monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors (a class of antidepressant) and corticosteroids when used over a long period.

Intermittent elevation of BP interspersed with normal readings is called labile hypertension or borderline hypertension. More and more adults over age 50 and many older adults have a type of high BP called isolated systolic hypertension (ISH) characterized by marked elevation of the systolic pressure (140 mm Hg or higher) but normal diastolic pressure (less than 90 mm Hg).86

ISH is a risk factor for stroke and death from cardiovascular causes. Elevated systolic pressure also raises the risk of heart attack, CHF, dementia, and end-stage kidney disease.87

Two other types of hypertension include masked hypertension (normal in the clinic but periodically high at home) and white-coat hypertension, a clinical condition in which the client has elevated BP levels when measured in a clinic setting by a health care professional. In such cases, BP measurements are consistently normal outside of a clinical setting.

Masked hypertension may effect up to 10% of adults; white-coat hypertension occurs in 15% to 20% of adults with Stage I hypertension.88 These types of hypertension are more common in older adults. Antihypertensive treatment for white coat hypertension may reduce office BP but may not affect ambulatory BP. The number of adults who develop sustained high BP is much higher among those who have masked or white-coat hypertension.88

At-home BP measurements can help identify adults with masked hypertension, white-coat hypertension, ambulatory hypertension, and individuals who do not experience the usual nocturnal drop in BP (decrease of 15 mm Hg), which is a risk factor for cardiovascular events.89 Excessive morning BP surge is a predictor of stroke in older adults with known hypertension and is also a red flag sign.89 Medical referral is indicated in any of these situations.

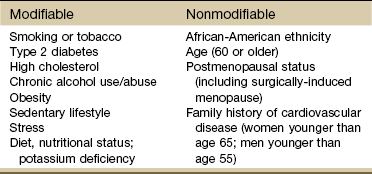

Risk Factors

Modifiable risk factors for hypertension are primarily lifestyle factors such as stress, obesity, and poor diet or insufficient intake of nutrients (Table 6-6). Stress has been shown to cause increased peripheral vascular resistance and cardiac output and to stimulate sympathetic nervous system activity. Potassium deficiency can also contribute to hypertension.

The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC-7; see Table 4-5) created a new BP category called “prehypertension” to identify adults considered to be at risk for developing hypertension and to alert both individuals and health care providers of the importance of adopting lifestyle changes. Screening for prehypertension provides important opportunities to prevent hypertension and cardiovascular disease.90

Nonmodifiable risk factors include family history, age, gender, postmenopausal status, and race. The risk of hypertension increases with age as arteries lose elasticity and become less able to relax. There is a poorer prognosis associated with early onset of hypertension.

A sex-specific gene for hypertension may exist91 because men experience hypertension at higher rates and at an earlier age than women do until after menopause. Hypertension is the most serious health problem for African-Americans (both men and women and at earlier ages than for whites) in the United States (see further discussion of hypertension in African Americans in Chapter 4).

Transient Ischemic Attack

Hypertension is a major cause of heart failure, stroke, and kidney failure. Aneurysm formation and CHF are also associated with hypertension. Persistent elevated diastolic pressure damages the intimal layer of the small vessels, which causes an accumulation of fibrin, local edema, and possibly intravascular clotting.

Eventually, these damaging changes diminish blood flow to vital organs, such as the heart, kidneys, and brain, resulting in complications such as heart failure, renal failure, and cerebrovascular accidents or stroke.

Many persons have brief episodes of transient ischemic attacks (TIAs). The attacks occur when the blood supply to part of the brain has been temporarily disrupted. These ischemic episodes last from 5 to 20 minutes, although they may last for as long as 24 hours. TIAs are considered by some as a progression of cerebrovascular disease and may be referred to as “mini-strokes.”

TIAs are important warning signals that an obstruction exists in an artery leading to the brain. Without treatment, 10% to 20% of people will go on to have a major stroke within 3 months, many within 48 hours.92 Immediate medical referral is advised for anyone with signs and symptoms of TIAs, especially anyone with a history of heart disease, hypertension, or tobacco use. Other risk factors for TIAs include age (over 65), diabetes, and being overweight.

Orthostatic Hypotension (See also discussion on Hypotension in Chapter 4)

Orthostatic hypotension is an excessive fall in BP of 20 mm Hg or more in systolic BP or a drop of 10 mm Hg or more of both systolic and diastolic arterial BP on assumption of the erect position with a 10% to 20% increase in pulse rate (Case Example 6-10). It is not a disease but a manifestation of abnormalities in normal BP regulation.

This condition may occur as a normal part of aging or secondary to the effects of drugs such as hypertensives, diuretics, and antidepressants; as a result of venous pooling (e.g., pregnancy, prolonged bed rest, or standing); or in association with neurogenic origins. The last category includes diseases affecting the autonomic nervous system, such as Guillain-Barré syndrome, diabetes mellitus, or multiple sclerosis.

Orthostatic intolerance is the most common cause of lightheadedness in clients, especially those who have been on prolonged bed rest or those who have had prolonged anesthesia for surgery. When such a client is getting up out of bed for the first time, BP, and heart rate should be monitored with the person in the supine position and repeated after the person is upright. If the legs are dangled off the bed, a significant drop in BP may occur with or without compensatory tachycardia. This drop may provoke lightheadedness, and standing may even produce loss of consciousness.

These postural symptoms are often accentuated in the morning and are aggravated by heat, humidity, heavy meals, and exercise.

Peripheral Vascular Disorders

Impaired circulation may be caused by a number of acute or chronic medical conditions known as PVDs. PVDs can affect the arterial, venous, or lymphatic circulatory system.

Vascular disorders secondary to occlusive arterial disease usually have an underlying atherosclerotic process that causes disturbances of circulation to the extremities and can result in significant loss of function of either the upper or lower extremities.

Peripheral arterial occlusive diseases also can be caused by embolism, thrombosis, trauma, vasospasm, inflammation, or autoimmunity. The cause of some disorders is unknown.

Arterial (Occlusive) Disease

Arterial diseases include acute and chronic arterial occlusion (Table 6-7). Acute arterial occlusion may be caused by

TABLE 6-7

Comparison of Acute and Chronic Arterial Symptoms

| Symptom Analysis | Acute Arterial Symptoms | Chronic Arterial Symptoms |

| Location | Varies; distal to occlusion; may involve entire leg | Deep muscle pain, usually in calf, may be in lower leg or dorsum of foot |

| Character | Throbbing | Intermittent claudication; feels like cramp, numbness, and tingling; feeling of cold |

| Onset and duration | Sudden onset (within 1 hour) | Chronic pain, onset gradual following exertion |

| Aggravating factors | Activity such as walking or stairs; elevation | Same as acute arterial symptoms |

| Relieving factors | Rest (usually within 2 minutes); dangling (severe involvement) | Same as acute arterial symptoms |

| Associated symptoms | 6 P’s: Pain, pallor, pulselessness, paresthesia, poikilothermia (coldness), paralysis (severe) | Cool, pale skin |

| At risk | History of vascular surgery, arterial invasive procedure, abdominal aneurysm, trauma (including injured arteries), chronic atrial fibrillation | Older adults; more males than females; inherited predisposition; history of hypertension, smoking, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, obesity, vascular disease |

From American Heart Association (AHA): Heart and stroke encyclopedia. Available at http://www.americanheart.org. Accessed November 11, 2010.

1. Thrombus, embolism, or trauma to an artery

2. Arteriosclerosis obliterans

Clinical manifestations of chronic arterial occlusion caused by peripheral vascular disease may not appear for 20 to 40 years. The lower limbs are far more susceptible to arterial occlusive disorders and atherosclerosis than are the upper limbs.

Risk Factors: Diabetes mellitus increases the susceptibility to coronary heart disease. People with diabetes have abnormalities that affect a number of steps in the development of atherosclerosis. Only the combination of factors, such as hypertension, abnormal platelet activation, and metabolic disturbances affecting fat and serum cholesterol, accounts for the increased risk.

Other risk factors include smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidemia (elevated levels of fats in the blood), and older age. Peripheral artery disease most often afflicts men older than 50, although women are at significant risk because of their increased smoking habits.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms: The first sign of vascular occlusive disease may be the loss of hair on the toes. The most important symptoms of chronic arterial occlusive disease are intermittent claudication (limping resulting from pain, ache, or cramp in the muscles of the lower extremities caused by ischemia or insufficient blood flow) and ischemic rest pain.

The pain associated with arterial disease is generally felt as a dull, aching tightness deep in the muscle, but it may be described as a boring, stabbing, squeezing, pulling, or even burning sensation. Although the pain is sometimes referred to as a cramp, there is no actual spasm in the painful muscles.

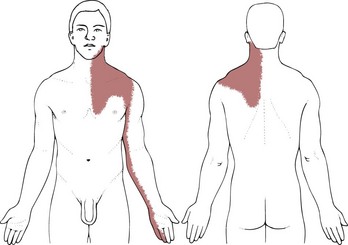

The location of the pain is determined by the site of the major arterial occlusion (see Table 14-7). Aortoiliac occlusive disease induces pain in the gluteal and quadriceps muscles. The most frequent lesion, which is present in about two thirds of clients, is occlusion of the superficial femoral artery between the groin and the knee, producing pain in the calf that sometimes radiates upward to the popliteal region and to the lower thigh. Occlusion of the popliteal or more distal arteries causes pain in the foot.

In the typical case of superficial femoral artery occlusion, there is a good femoral pulse at the groin but arterial pulses are absent at the knee and foot, although resting circulation appears to be good in the foot.

After exercise, the client may have numbness in the foot, as well as pain in the calf. The foot may be cold, pale, and chalky white, which is an indication that the circulation has been diverted to the arteriolar bed of the leg muscles. Blood in regions of sluggish flow becomes deoxygenated, inducing a red-purple mottling of the skin.

Painful cramping symptoms occur during walking and disappear quickly with rest. Ischemic rest pain is relieved by placing the limb in a dependent position, using gravity to enhance blood flow. In most clients the symptoms are constant and reproducible (i.e., the client who cannot walk the length of the house because of leg pain one day but is able to walk indefinitely the next does not have intermittent claudication).

Intermittent claudication is influenced by the speed, incline, and surface of the walk. Exercise tolerance decreases over time, so that episodes of claudication occur more frequently with less exertion. The differentiation between vascular claudication and neurogenic claudication is presented in Chapter 16 (see Table 16-5).

Ulceration and gangrene are common complications and may occur early in the course of some arterial diseases (e.g., Buerger’s disease). Gangrene usually occurs in one extremity at a time. In advanced cases the extremities may be abnormally red or cyanotic, particularly when dependent. Edema of the legs is fairly common. Color or temperature changes and changes in nail bed and skin may also appear.

Raynaud’s Phenomenon and Disease

The term Raynaud’s phenomenon refers to intermittent episodes during which small arteries or arterioles in extremities constrict, causing temporary pallor and cyanosis of the digits and changes in skin temperature.

These episodes occur in response to cold temperature or strong emotion (anxiety, excitement). As the episode passes, the changes in color are replaced by redness. If the disorder is secondary to another disease or underlying cause, the term secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon is used.

Secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon is often associated with connective tissue or collagen vascular disease, such as scleroderma, polymyositis/dermatomyositis, SLE, or rheumatoid arthritis. Raynaud’s may occur as a long-term complication of cancer treatment. Unilateral Raynaud’s phenomenon may be a sign of hidden neoplasm.

Raynaud’s phenomenon may occur after trauma or use of vibrating equipment such as jackhammers, or it may be related to various neurogenic lesions (e.g., thoracic outlet syndrome) and occlusive arterial diseases.

Raynaud’s disease is a primary vasospastic or vasomotor disorder, although it is included in this section under occlusive arterial because of the arterial involvement. It appears to be caused by

Eighty percent of clients with Raynaud’s disease are women between the ages of 20 and 49 years. Primary Raynaud’s disease rarely leads to tissue necrosis.

Idiopathic Raynaud’s disease is differentiated from secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon by a history of symptoms for at least 2 years with no progression of the symptoms and no evidence of underlying cause.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms: The typical progression of Raynaud’s phenomenon is pallor in the digits, followed by cyanosis accompanied by feelings of cold, numbness, and occasionally pain, and finally, intense redness with tingling or throbbing.

The pallor is caused by vasoconstriction of the arterioles in the extremity, which leads to decreased capillary blood flow. Blood flow becomes sluggish and cyanosis appears; the digits turn blue. The intense redness (rubor) results from the end of vasospasm and a period of hyperemia as oxygenated blood rushes through the capillaries.

Venous Disorders

Venous disorders can be separated into acute and chronic conditions. Acute venous disorders include thromboembolism. Chronic venous disorders can be separated further into varicose vein formation and chronic venous insufficiency.

Acute Venous Disorders: Acute venous disorders are due to formation of thrombi (clots), which obstruct venous flow. Blockage may occur in both superficial and deep veins. Superficial thrombophlebitis is often iatrogenic, resulting from insertion of intravenous catheters or as a complication of intravenous sites.

Pulmonary emboli (see Chapter 7), most of which start as thrombi in the large deep veins of the legs, are an acute and potentially lethal complication of deep venous thrombosis.

Thrombus formation results from an intravascular collection of platelets, erythrocytes, leukocytes, and fibrin in the blood vessels, often the deep veins of the lower extremities. When thrombus formation occurs in the deep veins, the production of clots can cause significant morbidity and mortality resulting in a floating mass (embolus) that can occlude blood vessels of the lungs and other critical structures.93

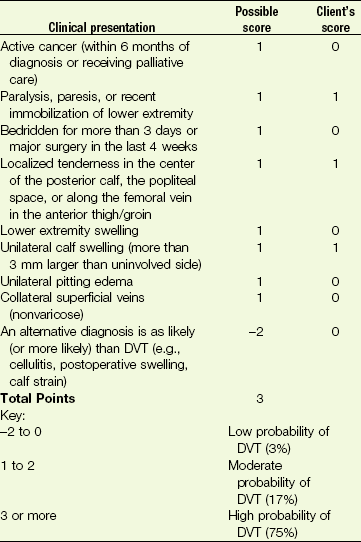

Risk Factors: Deep venous thrombosis (DVT) defined as blood clots in the pelvic, leg, or major upper extremity veins is a common disorder, affecting women more than men and adults more than children. Approximately one third of clients older than 40 who have had either major surgery or an acute MI develop DVT. The most significant clinical risk factors are age over 70 and previous thromboembolism94,95 (Box 6-2).

Thrombus formation is usually attributed to (1) venous stasis, (2) hypercoagulability, or (3) injury to the venous wall. Venous stasis is caused by prolonged immobilization or absence of the calf muscle pump (e.g., because of illness, paralysis, or inactivity). Other risk factors include traumatic spinal cord injury, multiple trauma, CHF, obesity, pregnancy, and major surgery (orthopedic, oncologic, gynecologic, abdominal, cardiac, renal, or splenic)96 (Case Example 6-11).

Hypercoagulability often accompanies malignant neoplasms, especially visceral and ovarian tumors. Oral contraceptives, selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs; e.g., raloxifene) often used for osteoporosis related to menopause, and hematologic (clotting) disorders also may increase the coagulability of the blood. In addition, previous spontaneous thromboembolism and increased levels of homocysteine are risk factors for venous as well as arterial thrombosis.97

The observed relationship of higher venous thrombosis risk with the use of third-generation oral contraceptives is an important consideration.98,99 Third-generation contraceptives refer to the newest formulation of oral contraceptives with much lower levels of estrogen than those first administered.

The risk of having a blood clot depends on a number of factors. It increases with age and it also depends on what kind of oral contraceptive is being taken. Women using progestogen-only pills are at little or no increased risk of blood clots. The venous clots associated with the newest oral contraceptives typically develop in superficial leg veins and rarely result in pulmonary emboli.

Injury or trauma to the venous wall may occur as a result of intravenous injections, Buerger’s disease, fractures and dislocations, sclerosing agents, and opaque mediator radiography.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms: Superficial thrombophlebitis appears as a local, raised, red, slightly indurated (hard), warm, tender cord along the course of the involved vein.

In contrast, symptoms of DVT are less distinctive; about one half of clients are asymptomatic. The most common symptoms are pain in the region of the thrombus and unilateral swelling distal to the site (Case Example 6-12).

Other symptoms include redness or warmth of the arm or leg, dilated veins, or low-grade fever, possibly accompanied by chills and malaise. Unfortunately, the first clinical manifestation may be pulmonary embolism. Frequently, clients have thrombi in both legs even though the symptoms are unilateral. For further discussion of DVT of the upper extremity, see Chapter 18.

Homans’ sign (discomfort in the upper calf during gentle, forced dorsiflexion of the foot) is still commonly assessed during physical examination. Unfortunately, it is insensitive and nonspecific. It is present in less than one third of clients with documented DVT. In addition, more than 50% of clients with a positive finding of Homans’ sign do not have evidence of venous thrombosis.

Other more specific risk assessment and physical assessment tools are available for assessment of DVT and PVD (see ankle-brachial index [ABI], Autar DVT Risk Assessment Scale, and Wells’ Clinical Decision Rule [CDR] in Chapter 4). A simple model to predict upper extremity DVT has also been proposed and remains under investigation (see Table 18-3).100

The CDR may be used more widely in the clinic, but the Autar scale is more comprehensive and incorporates BMI, postpartum status, and the use of oral contraceptives as potential risk factors.

The Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR) now recommends that anyone being evaluated for PVD should have an ABI measurement done, since this is a significantly more accurate screening measure for PVD.101 Symptoms of superficial thrombophlebitis are relieved by bed rest with elevation of the legs and the application of heat for 7 to 15 days. When local signs of inflammation subside, the client is usually allowed to ambulate wearing elastic stockings.

Sometimes, antiinflammatory medications are required. Anticoagulants, such as heparin and warfarin, are used to prevent clot extension.

Chronic Venous Disorders.: Chronic venous insufficiency, also known as postphlebitic syndrome, is identified by chronic swollen limbs; thick, coarse, brownish skin around the ankles; and venous stasis ulceration. Chronic venous insufficiency is the result of dysfunctional valves that reduce venous return, which thus increases venous pressure and causes venous stasis and skin ulcerations.

Chronic venous insufficiency follows most severe cases of deep venous thrombosis but may take as long as 5 to 10 years to develop. Education and prevention are essential, and clients with a history of deep venous thrombosis must be monitored periodically for life.

Lymphedema

The final type of peripheral vascular disorder, lymphedema, is defined as an excessive accumulation of fluid in tissue spaces. Lymphedema typically occurs secondary to an obstruction of the lymphatic system from trauma, infection, radiation, or surgery.

Postsurgical lymphedema is usually seen after surgical excision of axillary, inguinal, or iliac nodes, usually performed as a prophylactic or therapeutic measure for metastatic tumor. Lymphedema secondary to primary or metastatic neoplasms in the lymph nodes is common.

Laboratory Values

The results of diagnostic tests can provide the therapist with information to assist in client education. The client often reports test results to the therapist and asks for information regarding the significance of those results. The information presented in this text discusses potential reasons for abnormal laboratory values relevant to clients with cardiovascular problems.

A basic understanding of laboratory tests used specifically in the diagnosis and monitoring of cardiovascular problems can provide the therapist with additional information regarding the client’s status.

Some of the tests commonly used in the management and diagnosis of cardiovascular problems include lipid screening (cholesterol levels, LDL levels, high-density lipoprotein [HDL] levels, and triglyceride levels), serum electrolytes, and arterial blood gases (see Chapter 7).

Other laboratory measurements of importance in the overall evaluation of the client with cardiovascular disease include red blood cell values (e.g., red blood cell count, hemoglobin, and hematocrit). Those values (see Chapter 5) provide valuable information regarding the oxygen-carrying capability of the blood and the subsequent oxygenation of body tissues such as the heart muscle.

Serum Electrolytes

Measurement of serum electrolyte values is particularly important in diagnosis, management, and monitoring of the client with cardiovascular disease because electrolyte levels have a direct influence on the function of cardiac muscle (in a manner similar to that of skeletal muscle). Abnormalities in serum electrolytes, even in noncardiac clients, can result in significant cardiac arrhythmias and even cardiac arrest.

In addition, certain medications prescribed for cardiac clients can alter serum electrolytes in such a way that rhythm problems can occur as a result of the medication. The electrolyte levels most important to monitor include potassium, sodium, calcium, and magnesium (see inside back cover).

Potassium

Serum potassium levels can be lowered significantly as a result of diuretic therapy (particularly with loop diuretics such as Lasix [furosemide]), vomiting, diarrhea, sweating, and alkalosis. Low potassium levels cause increased electrical instability of the myocardium, life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias, and increased risk of digitalis toxicity.

Serum potassium levels must be measured frequently by the physician in any client taking a digitalis preparation (e.g., digoxin), because most of these clients are also undergoing diuretic therapy. Low potassium levels in clients taking digitalis can cause digitalis toxicity and precipitate life-threatening arrhythmias.

Increased potassium levels most commonly occur because of renal and endocrine problems or as a result of potassium replacement overdose. Cardiac effects of increased potassium levels include ventricular arrhythmias and asystole/flat line (complete cessation of electrical activity of the heart).

Sodium

Serum sodium levels indicate the client’s state of water/fluid balance, which is particularly important in CHF and other pathologic states related to fluid imbalances. A low serum sodium level can indicate water overload or extensive loss of sodium through diuretic use, vomiting, diarrhea, or diaphoresis.

A high serum sodium level can indicate a water deficit state such as dehydration or water loss (e.g., lack of antidiuretic hormone [ADH]).

Calcium

Serum calcium levels can be decreased as a result of multiple transfusions of citrated blood, renal failure, alkalosis, laxative or antacid abuse, and parathyroid damage or removal. A decreased calcium level provokes serious and often life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias and cardiac arrest.

Increased calcium levels are less common but can be caused by a variety of situations, including thiazide diuretic use (e.g., Diuril [chlorothiazide]), acidosis, adrenal insufficiency, immobility, and vitamin D excess. Calcium excess causes atrioventricular conduction blocks or tachycardia and ultimately can result in cardiac arrest.

Magnesium

Serum magnesium levels are rarely changed in healthy individuals because magnesium is abundant in foods and water. However, magnesium deficits are often seen in alcoholic clients or clients with critical illnesses that involve shifting of a variety of electrolytes.

Magnesium deficits often accompany potassium and calcium deficits. A decrease in serum magnesium results in myocardial irritability and cardiac arrhythmias, such as atrial or ventricular fibrillation or premature ventricular beats (PVCs).

Screening for the Effects of Cardiovascular Medications

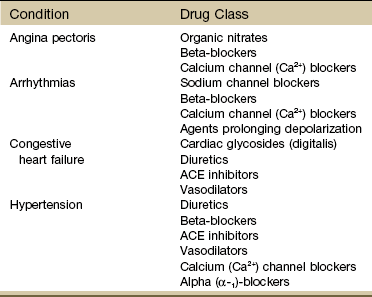

When a client is physically challenged, as often occurs in physical therapy, signs and symptoms develop from side effects of various classes of cardiovascular medications (Table 6-8).

TABLE 6-8

ACE, Angiotensin-converting enzyme.

Courtesy Susan Queen, Ph.D., P.T., University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Physical Therapy Program, Albuquerque, New Mexico.

For example, medications that cause peripheral vasodilation can produce hypotension, dizziness, and syncope when combined with physical therapy interventions that also produce peripheral vasodilation (e.g., hydrotherapy, aquatics, aerobic exercise).

On the other hand, cardiovascular responses to exercise can be limited in clients who are taking beta-blockers because these drugs limit the increase in heart rate that can occur as exercise increases the workload of the heart. The available pharmaceuticals used in the treatment of the conditions listed in Table 6-8 are extensive. Understanding of drug interactions and implications requires a more specific text.

The therapist must especially keep in mind that nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), often used in the treatment of inflammatory conditions, have the ability to negate the antihypertensive effects of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors. Anyone being treated with both NSAIDs and ACE inhibitors must be monitored closely during exercise for elevated BP.

Likewise, NSAIDs have the ability to decrease the excretion of digitalis glycosides (e.g., digoxin [Lanoxin] and digitoxin [Crystodigin]). Therefore levels of these glycosides can increase, thus producing digitalis toxicity (e.g., fatigue, confusion, gastrointestinal problems, arrhythmias).

Digitalis and diuretics in combination with NSAIDs exacerbate the side effects of NSAIDs. Anyone receiving any of these combinations must be monitored for lower-extremity (especially ankle) and abdominal swelling.

Diuretics

Diuretics, usually referred to by clients as “water pills,” lower BP by eliminating sodium and water and thus reducing the blood volume. Thiazide diuretics may also be used to prevent osteoporosis by increasing calcium reabsorption by the kidneys. Some diuretics remove potassium from the body, causing potentially life-threatening arrhythmias.

The primary adverse effects associated with diuretics are fluid and electrolyte imbalances such as muscle weakness and spasms, dizziness, headache, incoordination, and nausea (Box 6-3).

Beta-Blockers

Beta-blockers relax the blood vessels and the heart muscle by blocking the beta receptors on the sinoatrial node and myocardial cells, producing a decline in the force of contraction and a reduction in heart rate. This effect eases the strain on the heart by reducing its workload and reducing oxygen consumption.

The therapist must monitor the client’s perceived exertion and watch for excessive slowing of the heart rate (bradycardia) and contractility, resulting in depressed cardiac function. Other potential side effects include depression, worsening of asthma symptoms, sexual dysfunction, and fatigue. The generic names of beta-blockers end in “olol” (e.g., propranolol, metoprolol, atenolol). Trade names include Inderal, Lopressor, and Tenormin.

Alpha-1 Blockers

Alpha-1 blockers lower the BP by dilating blood vessels. The therapist must be observant for signs of hypotension and reflex tachycardia (i.e., the heart rate increases to compensate for the hypotension). The generic names of alpha-1 blockers end in “zosin” (e.g., prazosin, terazosin, doxazosin; trade names include Minipress, Hytrin, Cardura).

ACE Inhibitors

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are highly selective drugs that interrupt a chain of molecular messengers that constrict blood vessels. They can improve cardiac function in individuals with heart failure and are used for persons with diabetes or early kidney damage. Rash and a persistent dry cough are common side effects. The generic names of ACE inhibitors end in “pril” (e.g., benazepril, captopril, enalapril, lisinopril). Trade names include Lotensin, Capoten, Vasotec, Prinivil, and Zestril. Newest on the market are ACE II inhibitors, such as Cozaar (losartan potassium) and Hyzaar (losartan potassium-hydrochlorothiazide).

Calcium Channel Blockers

Calcium channel blockers inhibit calcium from entering the blood vessel walls, where calcium works to constrict blood vessels. Side effects may include swelling in the feet and ankles, orthostatic hypotension, headache, and nausea.

There are several groups of calcium channel blockers. Those in the group that primarily interact with calcium channels on the smooth muscle of the peripheral arterioles all end with “pine” (e.g., amlodipine, felodipine, nisoldipine, nifedipine). Trade names include Norvasc, Plendil, Sular, and Adalat or Procardia.

A second group of calcium channel blockers works to dilate coronary arteries to lower BP and suppress some arrhythmias. This group includes verapamil (Verelan, Calan, Isoptin) and diltiazem (Cardizem, Dilacor).

Nitrates

Nitrates, such as nitroglycerin (e.g., nitroglycerin [Nitrostat, Nitro-Bid], isosorbide dinitrate [Iso-Bid, Isordil]), dilate the coronary arteries and are used to prevent or relieve the symptoms of angina. Headache, dizziness, tachycardia, and orthostatic hypotension may occur as a result of the vasodilating properties of these drugs.

There are other classes of drugs to treat various aspects of cardiovascular diseases separate from those listed in Table 6-8. Hyperlipidemia is often treated with medications to inhibit cholesterol synthesis. Platelet aggregation and clot formation are prevented with anticoagulant drugs, such as heparin, warfarin (Coumadin), and aspirin, whereas thrombolytic drugs, such as streptokinase, urokinase, and tissue-type plasminogen activator (t-PA), are used to break down and dissolve clots already formed in the coronary arteries.

Anyone receiving cardiovascular medications, especially in combination with other medications or OTC drugs, must be monitored during physical therapy for red flag signs and symptoms and any unusual vital signs.

The therapist should be familiar with the signs or symptoms that require immediate physician referral and those that must be reported to the physician. Special Questions to Ask: Medications are available at the end of this chapter.

Physician Referral

Referral by the therapist to the physician is recommended when the client has any combination of systemic signs or symptoms discussed throughout this chapter at presentation. These signs and symptoms should always be correlated with the client’s history to rule out systemic involvement or to identify musculoskeletal or neurologic disorders that would be appropriate for physical therapy intervention.

Clients often confide in their therapists and describe symptoms of a more serious nature. Cardiac symptoms unknown to the physician may be mentioned to the therapist during the opening interview or in subsequent visits.

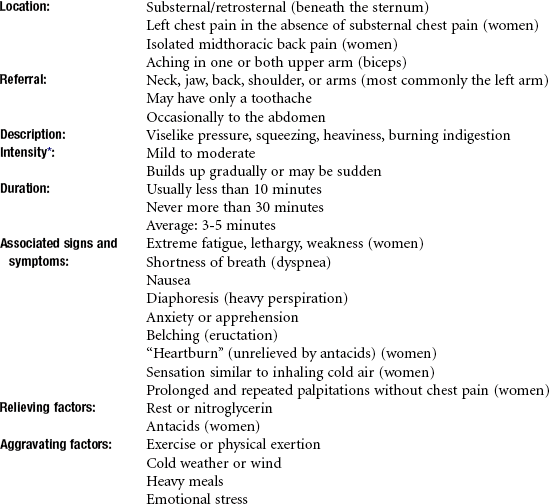

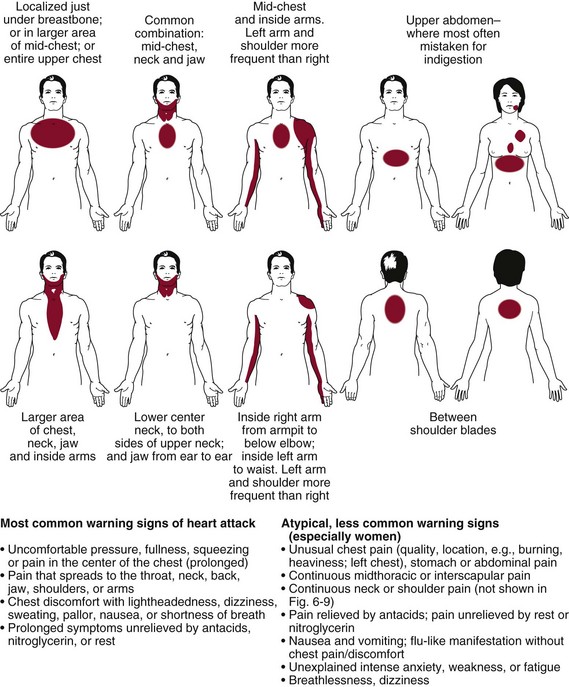

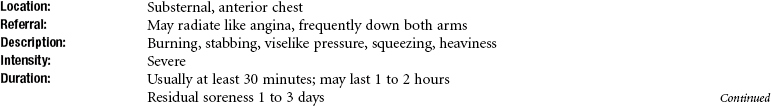

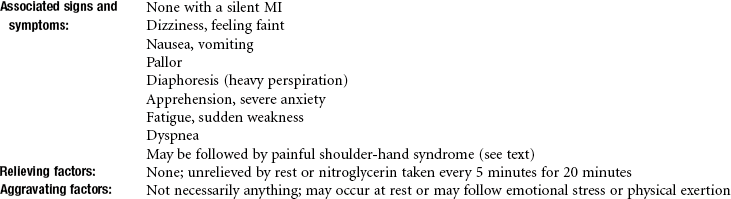

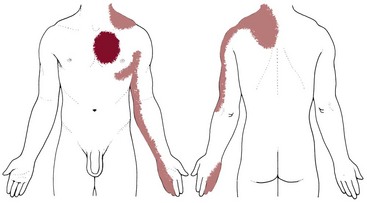

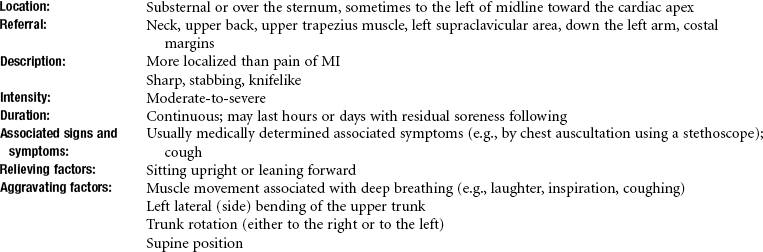

The description and location of chest pain associated with pericarditis, MI, angina, breast pain, gastrointestinal disorders, and anxiety are often similar. The physician is able to distinguish among these conditions through a careful history, medical examination, and medical testing.

For example, compared with angina, the pain of true musculoskeletal disorders may last for seconds or for hours, is not relieved by nitroglycerin, and may be aggravated by local palpation or by exertion of just the upper body.

It is not the therapist’s responsibility to differentiate diagnostically among the various causes of chest pain, but rather to recognize the systemic origin of signs and symptoms that may mimic musculoskeletal disorders.

The physical therapy interview presented in Chapter 2 is the primary mechanism used to begin exploring a client’s reported symptoms; this is accomplished by carefully questioning the client to determine the location, duration, intensity, frequency, associated symptoms, and relieving or aggravating factors related to pain or symptoms.

Guidelines for Immediate Medical Attention

Sudden worsening of intermittent claudication may be due to thromboembolism and must be reported to the physician immediately. Symptoms of TIAs in any individual, especially those with a history of heart disease, hypertension, or tobacco use, warrant immediate medical attention.

In the clinic setting, the onset of an anginal attack requires immediate cessation of exercise. Symptoms associated with angina may be reduced immediately but should subside within 3 to 5 minutes of cessation of activity.

If the client is currently taking nitroglycerin, self-administration of medication is recommended. Relief from anginal pain should occur within 1 to 2 minutes of nitroglycerin administration; some women may obtain similar results with an antacid. The nitroglycerin may be repeated according to the prescribed directions. If anginal pain is not relieved in 20 minutes or if the client has nausea, vomiting, or profuse sweating, immediate medical intervention may be indicated.

Changes in the pattern of angina, such as increased intensity, decreased threshold of stimulus, or longer duration of pain, require immediate intervention by the physician. Pain associated with an MI is not relieved by rest, change of position, or administration of nitroglycerin or antacids.

Clients in treatment under these circumstances should either be returned to the care of the nursing staff or, in the case of an outpatient, should be encouraged to contact their physicians by telephone for further instructions before leaving the physical therapy department. The client should be advised not to leave unaccompanied.

Guidelines for Physician Referral

• When a client has any combination of systemic signs or symptoms at presentation, refer him or her to a physician.

• Women with chest or breast pain who have a positive family history of breast cancer or heart disease should always be referred to a physician for a follow up examination.

• Palpitation in any person with a history of unexplained sudden death in the family requires medical evaluation. More than 6 episodes of palpitations in 1 minute or palpitations lasting for hours or occurring in association with pain, shortness of breath, fainting, or severe lightheadedness require medical evaluation.

• Anyone who cannot climb a single flight of stairs without feeling moderately to severely winded or who awakens at night or experiences shortness of breath when lying down should be evaluated by a physician.

• Fainting (syncope) without any warning period of lightheadedness, dizziness, or nausea may be a sign of heart valve or arrhythmia problems. Unexplained syncope in the presence of heart or circulatory problems (or risk factors for heart attack or stroke) should be evaluated by a physician.

• Clients who are neurologically unstable as a result of a recent CVA, head trauma, spinal cord injury, or other central nervous system insult often exhibit new arrhythmias during the period of instability. When the client’s pulse is monitored, any new arrhythmias noted should be reported to the nursing staff or the physician.

• Cardiac clients should be sent back to their physician under the following conditions:

• Nitroglycerin tablets do not relieve anginal pain.

• Pattern of angina changes is noted.

• Client has abnormally severe chest pain with nausea and vomiting.

• Anginal pain radiates to the jaw or to the left arm.

• Anginal pain is not relieved by rest.

• Upper back feels abnormally cool, sweaty, or moist to touch.

• Client develops progressively worse dyspnea.

• Individual with coronary artery stent experiencing chest pain.

• Client demonstrates a difference of more than 40 mm Hg in pulse pressure (systolic BP minus diastolic BP = pulse pressure).

Clues to Screening for Cardiovascular Signs and Symptoms

Whenever assessing chest, breast, neck, jaw, back, or shoulder pain for cardiac origins, look for the following clues:

• Personal or family history of heart disease including hypertension

• Age (postmenopausal woman; anyone over 65)

• Other signs and symptoms such as pallor, unexplained profuse perspiration, inability to talk, nausea, vomiting, sense of impending doom or extreme anxiety

1. Pleuritic pain (exacerbated by respiratory movement involving the diaphragm, such as sighing, deep breathing, coughing, sneezing, laughing, or the hiccups; this may be cardiac if pericarditis or it may be pulmonary); have the client hold his or her breath and reassess symptoms—any reduction or elimination of symptoms with breath holding or the Valsalva maneuver suggests pulmonary or cardiac source of symptoms.

2. Pain on palpation (musculoskeletal origin).

3. Pain with changes in position (musculoskeletal or pulmonary origin; pain that is worse when lying down and improves when sitting up or leaning forward is often pleuritic in origin).

• If two of the three P’s are present, an MI is very unlikely. An MI or anginal pain occurs in approximately 5% to 7% of clients whose pain is reproducible by palpation. If the symptoms are altered by a change in positioning, this percentage drops to 2%, and if the chest pain is reproducible by respiratory movements, the likelihood of a coronary event is only 1%.72

• Chest pain may occur from intercostal muscle or periosteal trauma with protracted or vigorous coughing. Palpation of local chest wall will reproduce tenderness. However, a client can have both a pulmonary/cardiac condition with subsequent musculoskeletal trauma from coughing. Look for associated signs and symptoms (e.g., fever, sweats, blood in sputum).

• Angina is activated by physical exertion, emotional reactions, a large meal, or exposure to cold and has a lag time of 5 to 10 minutes. Angina does not occur immediately after physical activity. Immediate pain with activity is more likely musculoskeletal, thoracic outlet syndrome, or psychologic (e.g., “I do not want to shovel today”).

• Chest pain, shoulder pain, neck pain, or TMJ pain occurring in the presence of coronary artery disease or previous history of MI, especially if accompanied by associated signs and symptoms, may be cardiac.

• Upper quadrant pain that can be induced or reproduced by lower quadrant activity, such as biking, stair climbing, or walking without using the arms, is usually cardiac in origin.

• Recent history of pericarditis in the presence of new onset of chest, neck, or left shoulder pain; observe for additional symptoms of dyspnea, increased pulse rate, elevated body temperature, malaise, and myalgia(s).

• If an individual with known risk factors for congestive heart disease, especially a history of angina, becomes weak or short of breath while working with the arms extended over the head, ischemia or infarction is a likely cause of the pain and associated symptoms.

• Insidious onset of joint or muscle pain in the older client who has had a previously diagnosed heart murmur may be caused by bacterial endocarditis. Usually there is no morning stiffness to differentiate it from rheumatoid arthritis.

• Back pain similar to that associated with a herniated lumbar disk but without neurologic deficits especially in the presence of a diagnosed heart murmur, may be caused by bacterial endocarditis.

• Watch for arrhythmias in neurologically unstable clients (e.g., spinal cord, new CVAs, or new traumatic brain injuries [TBIs]); check pulse and ask about/observe for dizziness.

• Anyone with chest pain must be evaluated for trigger points. If palpation of the chest reproduces symptoms, especially symptoms of radiating pain, deactivation of the trigger points must be carried out and followed by a reevaluation as part of the screening process for pain of a cardiac origin (see Fig. 17-7 and Table 17-4).

• Symptoms of vascular occlusive disease include exertional calf pain that is relieved by rest (intermittent claudication), nocturnal aching of the foot and forefoot (rest pain), and classic skin changes, especially hair loss of the ankle and foot. Ischemic rest pain is relieved by placing the limb in a dependent position.

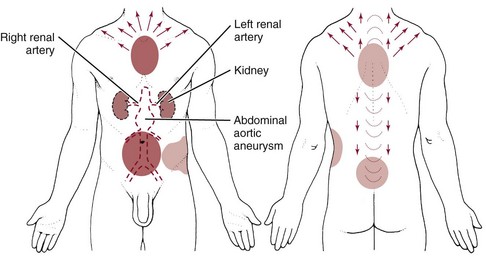

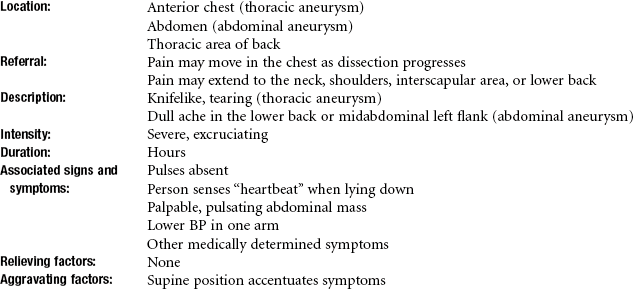

• Throbbing pain at the base of the neck and/or along the back into the interscapular areas that increases with exertion requires monitoring of vital signs and palpation of peripheral pulses to screen for aneurysm. Check for a palpable abdominal heartbeat that increases in the supine position.

• See also section on clues to differentiating chest pain in Chapter 17.

1. Pursed-lip breathing in the sitting position while leaning forward on the arms relieves symptoms of dyspnea for the client with:

2. Briefly describe the difference between myocardial ischemia, angina pectoris, and MI.

3. What should you do if a client complains of throbbing pain at the base of the neck that radiates into the interscapular areas and increases with exertion?

4. What are the 3Ps? What is the significance of each one?

5. When are palpitations clinically significant?

6. A 48-year-old woman with TMJ syndrome has been referred to you by her dentist. How do you screen for the possibility of medical (specifically cardiac) disease?

7. A 55-year-old male grocery store manager reports that he becomes extremely weak and breathless when he is stocking groceries on overhead shelves. What is the possible significance of this complaint?

8. You are seeing an 83-year-old woman for a home health evaluation after a motor vehicle accident (MVA) that required a long hospitalization followed by transition care in an intermediate care nursing facility and now home health care. She is ambulating short distances with a wheeled walker, but she becomes short of breath quickly and requires lengthy rest periods. At each visit the client is wearing her slippers and housecoat, so you suggest that she start dressing each day as if she intended to go out. She replies that she can no longer fit into her loosest slacks and she cannot tie her shoes. Is there any significance to this client’s comments, or is this consistent with her age and obvious deconditioning? Briefly explain your answer.

9. Peripheral vascular diseases include:

a. Arterial and occlusive diseases

b. Arterial and venous disorders

10. Which statement is the most accurate?

a. Arterial disease is characterized by intermittent claudication, pain relieved by elevating the extremity, and history of smoking.

b. Arterial disease is characterized by loss of hair on the lower extremities and throbbing pain in the calf muscles that goes away by using heat and elevation.

c. Arterial disease is characterized by painful throbbing of the feet at night that goes away by dangling the feet over the bed.

d. Arterial disease is characterized by loss of hair on the toes, intermittent claudication, and redness or warmth of the legs that is accompanied by a burning sensation.

11. What are the primary signs and symptoms of CHF?

a. Fatigue, dyspnea, edema, nocturia

b. Fatigue, dyspnea, varicose veins

12. When would you advise a client in physical therapy to take his/her nitroglycerin?

References

1. Heart disease & stroke statistics—2009. a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119:e21–e181.

2. Aspinall, W. Clinical testing for the craniovertebral hypermobility syndrome. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1989;12:180–181.

3. Magee, DJ. Orthopedic physical assessment, ed 5. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2008.

4. Childs, JD, Flynn, TW, Fritz, JM, et al. Screening for vertebrobasilar insufficiency in patients with neck pain: manual therapy decision-making in the presence of uncertainty. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2005;35(5):300–306.

5. Rivett, DA. The premanipulative vertebral artery testing protocol: a brief review. Physiotherapy. 1995;23:9–12.

6. Thiel, H, Wallace, K, Donut, J, et al. Effect of various head and neck positions on vertebral artery blood flow. Clin Biomech. 1994;9:105–110.

7. Childs, JD. Screening for vertebrobasilar insufficiency in patients with neck pain: manual therapy decision-making in the presence of uncertainty. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2005;35(5):300–306.

8. Richter, RR, Reinking, MF. How does evidence on the diagnostic accuracy of the vertebral artery test influence teaching of the test in a professional physical therapist education program? Phys Ther. 2005;85(6):589–599.

9. Trumbore, DJ. Statins and myalgia: a case report of pharmacovigilance with implications for physical therapy case report presented in partial fulfillment of DPT 910, Principles of Differential Diagnosis, Institute for Physical Therapy Education. Chester, Pennsylvania: Widener University; 2005.

10. Zhao, H, Thomas, G, Leung, Y, et al. Statins in lipid-lowering therapy. Acta Cardiol Sin. 2003;19:1–11.

11. Rosenson, RS. Current overview of statin-induced myopathy. Am J Med. 2004;116:408–416.

12. Roten, L, Schoenenberger, RA, Krahenbuhl, S, et al. Rhabdomyolysis in association with simvastatin and amiodarone. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:978–981.

13. Tomlinson, S, Mangione, K. Potential adverse effects of statins on muscle: update. Phys Ther. 2005;85(5):459–465.

14. Pasternak, RC, Smith, SC, Bairey-Merz, CN, et al. ACC/AHA/NHLBI clinical advisory on the use and safety of statins. Circulation. 2002;106:1024.

15. Mills EJ: Efficacy and safety of statin treatment for cardiovascular disease: a network meta-analysis of 170,255 patients from 76 randomized trials, QJM Oct. 7, 2010. Epub ahead of print.

16. Chatham, K. Suspected statin-induced respiratory muscle myopathy during long-term inspiratory muscle training in a patient with diaphragmatic paralysis. Phys Ther. 2009;89:257–266.

17. Tomlinson, SS. Potential adverse effects of statins on muscle. Phys Ther. 2005;85:459–465.

18. Bruckert, E. Mild to moderate muscular symptoms with high-dosage statin therapy in hyperlipidemic patients: the PRIMO study. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2005;19:403–414.

19. Mann, D. Trends in statin use and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels among US adults. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42:1208–1215.

20. Buettner, C. Prevalence of musculoskeletal pain and statin use. J Gen Intl Medicine. 2008;23:1182–1186.

21. Baxter, R, Moore, J. Diagnosis and treatment of acute exertional rhabdomyolysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2003;33(3):104–108.

22. Evans, M, Rees, A. Effects of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors on skeletal muscle: are all statins the same? Drug Saf. 2002;25:649–663.

23. Using Crestor—and all statins—safely, Harvard Heart Letter, September 2005; p 3. More information available at www.health.harvard.edu/heartextra. [Accessed: October 17, 2010].

24. Cholesterol drugs. very safe and highly beneficial. Johns Hopkins Medical Letter: Health After 50. 2002;13(12):3.

25. DiStasi, SL. Effects of statins on skeletal muscle: a perspective for physical therapists. Phys Ther. 2010;90(10):1530–1542.

26. Dobkin, BH. Underappreciated statin-induced myopathic weakness causes disability. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2005;19:259–263.

27. Kelln, BM. Hand-held dynamometry: reliability of lower extremity muscle testing in healthy, physically active, young adults. J Sport Rehab. 2008;17:160–170.

28. Prager, GW, Binder, BR. Genetic determinants: is there an “atherosclerosis gene”? Acta Med Austriaca. 2004;31(1):1–7.

29. Kurtz, TW, Gardner, DG. Transcription-modulating drugs: a new frontier in the treatment of essential hypertension. Hypertension. 1998;32(3):380–386.

30. Benson, SC, Pershadsingh, HA, Ho, CI. Identification of telmisartan as a unique angiotensin II receptor antagonist with selective PPAR gamma-modulating activity. Hypertension. 2004;43(5):993–1002.

31. Davidson, M. Confirmed previous infection with Chlamydia pneumoniae (TWAR) and its presence in early coronary atherosclerosis. Circulation. 1998;98(7):628–633.

32. Muhlestein, JB. Bacterial infections and atherosclerosis. J Invest Med. 1998;46(8):396–402.

33. Grayston, JT, Kronmal, RA, Jackson, LA, et al. Azithromycin for the secondary prevention of coronary events. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(16):1637–1645.

34. Toss, H, Gnarpe, J, Gnarpe, H. Increased fibrinogen levels are associated with persistent Chlamydia pneumoniae infection in unstable coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 1998;19(4):570–577.

35. Anderson, JL, Carlquist, JF, Muhlestein, JB, et al. Evaluation of C-reactive protein, an inflammatory marker, and infectious serology as risk factors of coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32(1):35–41.

36. Toth, PP. C-reactive protein as a potential therapeutic target in patients with coronary heart disease. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2005;7(5):333–334.

37. Morrow, DA, Rifai, N, Antman, EM, et al. C-reactive protein is a potent predictor of mortality independently of and in combination with troponin T in acute coronary syndromes: a TIMI 11A substudy-thrombolysis in myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31(7):1460–1465.

38. Elliot, WJ, Powel, LH. Diagonal earlobe creases and prognosis in patients with suspected coronary artery disease. Am J Med. 1996;100(2):205–211.

39. Bahcelioglu, M, Isik, AF, Demirel, D, et al. The diagonal ear lobe crease as sign of some diseases. Saudi Med. 2005;26(6):947–951.

40. Shrestha, I. Diagonal ear-lobe crease is correlated with atherosclerotic changes in carotid arteries. Circ J. 2009;73(10):1945–1949.

41. Friedlander, AH. Diagonal ear lobe crease and atherosclerosis: a review of the medical literature and oral and maxillofacial implications. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010. [Epub ahead of print Oct 22].

42. Koracevic, G. Point of disagreement in evidence-based medicine. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2009;30(1):89.

43. Yeh, ET, Bickford, CL. Cardiovascular complications of cancer therapy: incidence, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(24):2231–2247. [16].

44. American Heart Association (AHA). Heart and stroke encyclopedia. Available at http://www.americanheart.org. [Accessed November 11, 2010].

45. Gender matters. Heart disease risk in women. Harvard Women’s Health Watch. 2004;11(9):1–3.

46. Cheek, D. What’s different about heart disease in women? Nursing2003. 2003;33(8):36–42.

47. LaGrossa, J. Heart attack in women. Advance Online Editions for Physical Therapists. February 2 www.advanceforpt.com, 2004. [Available at Accessed October 17, 2010].

48. Barclay, L, Vega, C. AHA Updates Guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in women, CME 2004. Available at www.medscape.com. [Accessed October 17, 2010].

49. Cohen, MC, Rohtla, KM, Mittleman, MA, et al. Meta-analysis of the morning excess of acute myocardial infarction and sudden cardiac death. Am J Cardiol. 1997;79(11):1512–1516.

50. McSweeney, JC. Women’s early warning symptoms of acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2003;108(21):2619–2623.

51. Is it a heart attack? If you’re a woman, will you know? Berkeley Wellness Letter. 2000;17(2):10.

52. Marrugat, J. Mortality differences between men and women following first myocardial infarction. JAMA. 1998;280:1405–1409.

53. Cahalin, LP. Heart failure. Phys Ther. 1996;76(5):517–533.

54. Hiratzka, LF, Bakris, GL, Beckman, JA, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with thoracic aortic disease: executive summary. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American College of Radiology, American Stroke Association, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Interventional Radiology, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and Society for Vascular Medicine. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;76(2):E43–86.

55. Lederle, FA. Smokers’ relative risk for aortic aneurysm compared with other smoking-related diseases: a systematic review. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:329–334.

56. Dua, MM, Dalman, RL. Identifying aortic aneurysm risk factors in postmenopausal women. Womens Health. 2009;5(1):33–37.

57. Lederle, FA. Abdominal aortic aneurysm events in the women’s health initiative: cohort study. BMJ. 2008;337:1724–1734.

58. US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). One-time screening in select subsets of men. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:198–202.

59. Edwards, JZ. Chronic back pain caused by an abdominal aortic aneurysm: case report and review of the literature. Orthopedics. 2003;26:191–192.

60. Chervu, A. Role of physical examination in detection of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Surgery. 1995;117(4):454–457.

61. O’Gara, PT, Aortic aneurysm. Circulation 2003;107:e43. Available on-line at http://circ.ahajournals.org/cgi/content/full/107/6/e43. [Accessed January 6, 2010].

62. Moore, KL. Clinically oriented anatomy, ed 6. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010.

63. O’Rourke, MF. The cardiovascular continuum extended: aging effects on the aorta and microvasculature. Vasc Med. 2010;15(6):461–468.

64. Hickson, SS. The relationship of age with regional aortic stiffness and diameter. J Am Coll Cardiol: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2010;3(12):1247–1255.

65. Lam, CS. Aortic root remodeling over the adult life course: longitudinal data from the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2010;122(9):884–890.

66. Guinea, GV. Factors influencing the mechanical behavior of healthy human descending thoracic aorta. Physiol Meas. 2010;31:1553–1565.

67. Fink, HA. The accuracy of physical examination to detect abdominal aortic aneurysm. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:833–836.

68. Lederle, FA. Selective screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms with physical examination and ultrasound. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:1753.

69. Mechelli, F. Differential diagnosis of a patient referred to physical therapy with low back pain: abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38(9):551–557.

70. Hillman, ND, Tani, LY, Veasy, LG, et al. Current status of surgery for rheumatic carditis in children. Ann Thoracic Surg. 2004;78(4):1403–1408.

71. Sapico, FL, Liquette, JA, Sarma, RJ. Bone and joint infections in patients with infective endocarditis: review of a 4-year experience. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:783–787.

72. Vlahakis, NE, Temesgen, Z, Berbari, EF, et al. Osteoarticular infection complicating enterococcal endocarditis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(5):623–628.

73. Petrini, JR. Racial differences by gestational age in neonatal deaths attributable to congenital heart defects in the United States. MMWR. 2010;59(37):1208–1211.

74. Cava, JR, Danduran, MJ, Fedderly, RT, et al. Exercise recommendations and risk factors for sudden cardiac death. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2004;51(5):1401–1420.

75. Berger, S, Kugler, JD, Thomas, JA, et al. Sudden cardiac death in children and adolescents: introduction and overview. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2004;51(5):1201–1209.

76. Bader, RS, Goldberg, L, Sahn, DJ. Risk of sudden cardiac death in young athletes: which screening strategies are appropriate? Pediatr Clin North Am. 2004;51(5):1421–1441.

77. Hayek, E. Mitral valve prolapse. Lancet. 2005;365(9458):507–518.

78. Freed, LA, Benjamin, EJ, Levy, D, et al. Mitral valve prolapse in the general population: the benign nature of echocardiographic features in the Framingham Heart Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40(7):1298–1304.

79. Freed, LA, Levy, D, Levine, RA, et al. Prevalence and clinical outcome of mitral valve prolapse. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(1):1–7.

80. Hayek, E, Gring, CN, Griffin, BP. Mitral valve prolapse. Lancet. 2005;365(9458):507–518.

81. Montenero, A, Mollichelli, N, Zumbo, F, et al, Helicobacter pylori and atrial fibrillation: a possible pathogenic link. Heart. 2005;91;7:960–961. Available at http://www.heart.bmjjournals.com. [Accessed October 17, 2010].

82. Strandberg, TE. Isolated systolic blood pressure measurement. Lancet. 2008;372(9643):1033–1034.

83. Ntatsaki, E. Isolated systolic blood pressure measurement. Lancet. 2008;372(9643):1033.

84. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure, NIH Publication No. 03-5233, May 2003. Available at www.nhlbi.nih.gov/, 2010. [Accessed October 17].

85. Brookes, L, The definition and consequences of hypertension are evolving. Medscape Cardiology. 2010;9;1:2005. Available at http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/506463. [Accessed October 20].

86. Chaudhry, SI, Krumholz, HM, Foody, JM. Systolic hypertension in older persons. JAMA. 2004;292(9):1074–1080.

87. Your blood pressure: check that top number. Johns Hopkins Medical Letter: Health After 50. 2005;16(11):6–7.

88. Mancia, G. Long-term risk of sustained hypertension in white-coat or masked hypertension. Hypertension. 2009;54(2):226–232.

89. Furie KL: Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack. A guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association, Stroke epub ahead of print; October 21, 2010.

90. Miller, ER, Jehn, ML. New high blood pressure guidelines create new at-risk classification: changes in blood pressure classification by JNC 7. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2004;19(6):367–371.

91. O’Donnell, CJ, Lindpaintner, K, Larson, MG, et al. Evidence for association and genetic linkage with hypertension and blood pressure in men but not women in the Framingham heart study. Circulation. 1998;97(18):1766–1772.

92. Treating a “mini stroke” to prevent a “major” stroke. Johns Hopkins Medical Letter: Health After 50. 2005;17(8):6–7.

93. Tepper, S, McKeough, M. Deep venous thrombosis: risks, diagnosis, treatment interventions, and prevention. Acute Care Perspectives. 2000;9(1):1–7.

94. Rosenzweig, K. Differential diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis in a spinal cord injured client, Case report presented in partial fulfillment of DPT 910, Principles of Differential Diagnosis, Institute for Physical Therapy Education. Chester, Pennsylvania: Widener University; 2005.

95. Powell, M. Duplex ultrasound screening for deep vein thrombosis in spinal cord injured patients at rehabilitation admission. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 1999;80:1044–1046.

96. Agnelli, G, Sonaglia, F. Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Thromb Res. 2000;97(1):V49–V62.

97. Bauer, K. Hypercoagulable states. Hematology. 2005;10(Suppl 1):39.

98. Wu, O, Robertson, L, Langhorne, P, et al. Oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy, thrombophilias, and risk of venous thromboembolism: a systematic review. The Thrombosis: Risk and Economic Assessment of Thrombophilia Screening (TREATS) Study. Thromb Haemost. 2005;94(1):17–25.

99. Gomes, MP, Deitcher, SR. Risk of venous thromboembolic disease associated with hormonal contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy: a clinical review. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(18):1965–1976.

100. Constans, J. A clinical prediction score for upper extremity deep venous thrombosis. Thromb Haemost. 2008;99:202–207.

101. Sacks, D, Bakal, C, Beatty, P, et al. Position statement on the use of the ankle brachial index in the evaluation of patients with peripheral vascular disease. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2003;14(9 Pt 2):S389.

102. Horn, HR. The impact of cardiovascular disease. On-line http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/466799_2. [April 2004. Accessed Nov. 05, 2011].

103. de Virgilio, C. Ascending aortic dissection in weight lifters with cystic medial degeneration. Ann Thorac Surg. 1990;49(4):638–642.

104. Kario, K, Tobin, J, Wolfson, L, et al. Lower standing systolic blood pressure as a predictor of falls in the elderly: a community-based prospective study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38(1):246–252.

105. Ageno, W. Treatment of venous thromboembolism. Thromb Res. 2000;97(1):V63–V72.

Key Points to Remember

Key Points to Remember