Screening for Liver and Biliary Causes of Back Pain

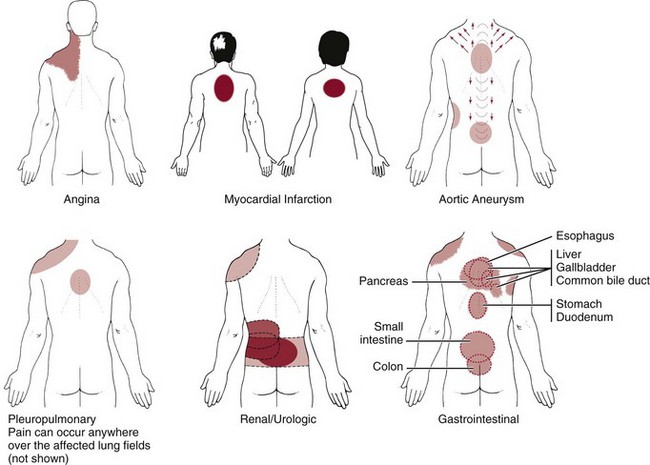

The primary pain pattern for liver disease is right over the liver. In primary liver pathology, palpation of the organ will reproduce the symptoms and the examiner can feel the liver distention. The normal, healthy liver is located up under the right side of the diaphragm and ribs. The gallbladder is tucked up under the liver (see also Fig. 9-2).

When a referred pain pattern occurs, there may be pain on palpation of the liver, but the primary complaint is of back pain. There is no report of anterior pain to alert the examiner to the need for liver palpation. In anyone with the referred pain patterns depicted and described in Fig. 9-10, liver palpation may be required as part of the physical assessment (see Figs. 4-51 and 4-52). In addition to a painful and distended liver, the client may report:

• Pain/nausea 1 to 3 hours after eating (gallstones)

• Pain immediately after eating (gallbladder inflammation)

• Muscle guarding/tenderness and fever/chills in the right upper quadrant (posterior)

Other signs and symptoms associated with liver impairment are discussed in detail in Chapter 9 and include:

Gallbladder and biliary disease may also refer pain to the interscapular or right subscapular area. The therapist should be observant for any report of fever and chills, nausea and indigestion, changes in urine or stool, or signs of jaundice. The client may not associate GI symptoms with the scapular pain or discomfort. The therapist can use specific questions to rule out potential GI problems (see Special Questions to Ask in this chapter and in greater detail in Chapter 8).

The Pancreas

Acute pancreatitis may appear as epigastric pain radiating to the mid-thoracic spine (see Fig. 8-17). Pain from the head of the pancreas is felt to the right of the spine, whereas pain from the body and tail is perceived to the left of the spine. More rarely, pain may be referred to the upper back and midscapular areas.

There may be a history of alcohol and tobacco use. Associated symptoms, which are usually GI related, may include diarrhea, anorexia, pain after a meal, and unexplained weight loss. The pain is relieved initially by heat, which decreases muscular tension, and may be relieved by leaning forward, sitting up, or lying motionless.

The therapist should remain alert for the client with LBP who reports benefit from a heating pad or other heat modalities but then suddenly gets worse and does not improve with physical therapy intervention.

Screening for Gynecologic Causes of Back Pain

Gynecologic disorders can cause midpelvic or LBP and discomfort. Gynecologic-induced back pain occurs most often in women of childbearing ages (commonly between ages 20 and 45). How can the therapist recognize when a woman may be experiencing back pain from a gynecologic cause?

As always, the model for screening includes history, presence of any risk factors, clinical presentation, and associated signs and symptoms. Obviously, female sex is a clear flag of possible gynecologic involvement in the case of back (or pelvic, groin, hip, sacral or SI) symptoms, especially with a history of insidious onset or previous history of reproductive cancer.

Whenever there is an absence of objective musculoskeletal findings, a history of gynecologic involvement, or associated signs and symptoms of gynecologic disorders, the therapist is encouraged to ask appropriate questions to determine the need for a gynecologic evaluation (Case Example 14-14).

The therapist must determine what phase the woman is in her reproductive life cycle (see previous discussions of Life Cycles and Menopause in Chapter 2). If the client is an adolescent, has she begun her menstrual cycle (menses)? If a young to middle-aged adult, is she menstruating, or has she had a hysterectomy and experienced surgically induced menopause?

Past Medical History

Gynecologic conditions causing back pain can include retroversion (tipping back) of the uterus, ovarian cysts, uterine fibroids, endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, or normal pregnancy (Case Example 14-15).

Usually, there is a history of a chronic or long-standing gynecologic disorder, and the association between back pain and gynecologic disorder has been established. There may be a history of sexual assault, incest, sexually transmitted disease (STD), ectopic pregnancy, use of an IUCD, dysuria, or abortion.

Risk Factors

Often the history and risk factors for back or pelvic pain are synonymous, especially multiple pregnancies and births, with administration of an epidural during delivery, prolonged pushing, and/or use of forceps. Other risk factors include abnormal uterine position, endometriosis, ovarian cysts and uterine fibroids, ectopic pregnancy, and the use of an IUCD.

Back pain is common during pregnancy beginning most often during the second trimester between the fifth and seventh months of gestation; intensity varies throughout pregnancy.129-132 Women who have had multiple pregnancies or births may have SI pain or LBP associated with poor abdominal or pelvic floor tone and ligamentous laxity. Studies repeated over time have not shown an increased risk of back pain in women who receive epidural anesthesia during delivery.133,134

Additionally, women who have had one or more abortions may seek health care months to years later with a variety of physical and psychologic symptoms referred to as postabortion syndrome or postabortion survivor’s syndrome. This condition has not been classified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual and its existence remains controversial.

Multiple Pregnancies and Births

Even though pregnancy and childbirth are natural physiologic processes, these events can be traumatic to the soft tissues of the pelvic floor. The risk of postpartum pain referred to the low back (with or without pelvic girdle pain) increases as a result of multiple pregnancies and births. If the woman’s history includes a recent birth or multiple previous births, she may not recognize the association between her current symptoms and her pregnancy/delivery history.

Abnormal Uterine Positions

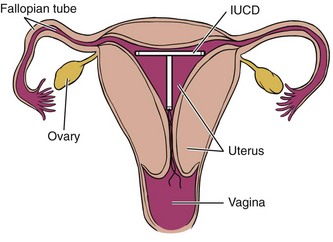

Having an understanding of the normal female reproductive anatomy (see Fig. 15-3) can help the therapist better appreciate musculoskeletal pain and dysfunction that can occur with abnormal uterine positions (see Fig. 15-4).

Taking a careful history and correlating symptoms with a woman’s monthly cycle can help the therapist determine when to refer a client for a possible gynecologic cause of back, pelvic, or sacral pain/symptoms. Many problems affecting the pelvic floor musculature can be treated successfully by a physical therapist and do not require medical referral.

Endometriosis

Endometriosis is an estrogen-dependent disorder defined by the presence of endometrial tissue (lining of the uterus) outside of the uterus. Each month as the woman’s body prepares for a fertilized egg, the uterus becomes engorged with blood, providing a fertile place for the egg to attach and begin growing. If and when the unfertilized egg passes out of the body, the uterus sloughs off the lining of blood and the woman has a flow of menstrual blood for about 3 to 5 days.

One theory to explain endometriosis suggests there may be retrograde menses, which means the blood goes up into the body, rather than down and out through the vagina. Whatever the mechanism, implants of cells that line the uterine cavity become transplanted and form small cysts outside of the uterus. These cysts are found on other organs or structures within the pelvic cavity. The cysts respond each month the same way as the endometrium during the menstrual cycle. The misplaced tissue engorges with blood just as it would when lining the uterus. The blood cannot drain out of the body and the result is lesions filled with a thick chocolate-type material or “chocolate cysts” wherever the endometrial tissue is located, with subsequent swelling, bleeding, and scar tissue formation.135,136

These pockets of blood can be deposited anywhere in the body. Whereas it was once thought that the blood just reached the pelvic and abdominal cavities, coating the viscera contained within, it is clear now that endometrial tissue migrates throughout the body. It has been recovered from bone, lungs, and even the brain.137,138

Pain can occur anywhere, but often the woman experiences back, pelvic, hip, and/or sacral pain that can be mistaken for a musculoskeletal, musculoligamentous, or neuromuscular impairment of the lumbar spine (Case Example 14-16).

The key to recognizing this condition is that often it is cyclical. Symptoms come and go with the menstrual cycle. After menopause, pain can persist from scar tissue. There may be urinary tract and bowel involvement with associated symptoms ranging from urinary frequency, intermittent dysuria, and bloody stools to ureteral or bowel obstruction.

This condition is more common than previously thought. It is estimated that up to 50% of the female population who are infertile are affected by endometriosis.137,139 It is not clear what, if any, risk factors increase a woman’s risk of developing endometriosis. Endometriosis has been linked with other health problems such as chronic fatigue syndrome, hypothyroidism, fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, and systemic lupus erythematosus.140-142 Endometriosis is a risk factor for ovarian and breast cancer.137,143

A cure has not been found at the present time, but for many women, it can be managed with medications and/or surgery. The therapist can be helpful in providing pain management strategies that can reduce sick leave and improve daily function. See Box 15-5 for more information on this condition.

Ovarian Cysts and Uterine Fibroids

Ovarian cysts are often asymptomatic until they grow large enough to pull the ovary out of its normal position, sometimes cutting off the blood supply to the ovary. As the weight of the ovary causes a change in position, pressure is exerted against the uterus, bladder, intestines, or vagina, causing a variety of symptoms.

Lower abdominal or pelvic pain is most common, but back pain associated with ovarian cysts and uterine fibroids can occur, usually presenting in a cyclical pattern associated with the menstrual cycle similar to endometriosis. A physician must determine the underlying gynecologic cause of back (hip, pelvic, sacral) pain or symptoms.

In a screening context, we look for red-flag histories, clinical presentation, risk factors, and associated signs and symptoms. Obesity may be a risk factor because more than half of the women affected by this disorder are obese but other risk factors remain unknown. Ovarian cysts present as part of the polycystic ovarian syndrome put the woman at increased risk for insulin resistance and potentially at increased risk for cardiovascular disease as a result.144-146

If the Review of Systems points to a gynecologic source of pain/symptoms, further questions can be asked and a referral made if appropriate. Low back pain is a late finding for some women with ovarian cancer (see Chapter 15).

Ectopic Pregnancy

An ectopic pregnancy is a live pregnancy that takes place outside the uterus. As shown in Fig. 15-5, this may occur in a variety of places such as the ovary, the tube (tubal pregnancy), outside lining of the uterus, or along the peritoneal cavity. None of these locations can sustain a viable ovum, and the woman will have a spontaneous abortion (miscarriage).

Risk factors include STDs, prior tubal surgery, and current use of an IUCD. Depending on the location of the ectopic pregnancy, symptoms can include back, hip, sacral, abdominal, pelvic, and/or shoulder pain. Shoulder pain is more likely to occur if there is retroperitoneal bleeding when rupture of the developing embryo and hemorrhage occurs with pressure on the diaphragm.

It is usually unilateral on the same side as the bleeding but can cause bilateral shoulder pain if the hemorrhage is significant enough to impinge both sides of the diaphragm. The pain is usually of a sudden onset (when rupture and hemorrhage occur) with intense, constant pain. Situations of this type represent a medical emergency. Most likely the client did not come to the therapist for this problem but may develop emerging symptoms while being treated for some other orthopedic or neurologic problem.

Consider it a red flag when any woman of childbearing age who is sexually active has sudden, intense pain as described. Take her blood pressure and other vital signs while asking appropriate screening questions. Seek immediate medical assistance.

Intrauterine Contraceptive Device

The intrauterine contraceptive device (IUCD is the current medical term; known by most women as an IUD) has become popular once again, having gone out of favor in the 1970s when the copper T caused so many problems. Although this contraceptive device has been improved, there are still potential problems (Fig. 14-6). The body may recognize this as a foreign object and set up an immune response or try to wall it off. The IUCD can become embedded in the tissue of the uterus, causing inflammation, infection, and scarring.

Fig. 14-6 Intrauterine contraceptive device (IUCD or IUD), a potential source of low back, pelvic, sacral, or even hip pain in any woman of reproductive age who is using this form of birth control.

For any woman with low back, pelvic, sacral, or hip pain who is in the reproductive age range, it may be necessary to ask about her method of birth control: Are you using an IUD for birth control?

Clinical Presentation

Back pain that is associated with the menstrual cycle occurs most often at or around the point of ovulation (between day 10 and day 14 for most women) and again just prior to or during menstrual flow (between days 23 and 28 for most women). Day 1 is counted as the first day the woman experiences bleeding with her menstrual cycle.

Back pain associated with the menstrual cycle may be a regular feature for a woman, it may occur intermittently, or it may be new onset, and the woman is unaware of the link between the two until she charts her monthly cycle and correlates it with her back pain.

A woman may have back pain accompanied by or alternating with sharp, bilateral, and cramping pain in the lower abdominal and/or pelvic quadrants. Menstrual pain can be referred to the rectum, lower sacrum, or coccyx. Tumors, masses, or even endometriosis may involve the sacral plexus or its branches, causing severe, burning pain.

Screening for Male Reproductive Causes of Back Pain

Men can experience back pain (as well as hip, groin, SI, and sacral pain) caused by referred pain from the male reproductive system. See Chapter 10 for a complete discussion of prostate impairments (e.g., prostatitis, benign prostatic hypertrophy, chronic pelvic pain syndrome, prostate and testicular cancer).

Prostate cancer is the second most common cancer in males over the age of 60 in the United States.147 The incidence of prostate cancer has risen 60% to 75% in the Western world in the last 15 years148 and with continued improvements in early detection is expected to continue to rise over the next 20 years,149 making it very likely that the therapist will treat clients with prostate pathology.

Testicular cancer, though relatively rare, is the most common cancer in males ages 15 to 35 years and on the rise.147 Details of both conditions are discussed in Chapter 10. Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is one of the most common disorders of the aging male population affecting 50% of men over age 50.

Risk Factors

Risk factors for prostate dysfunction include advancing age, family history, ethnicity (greater risk for African-American men), diet, and possibly exposure to chemicals. Not all disorders of this system occur with aging, so the therapist must remain alert for red flag symptoms in males of any age.

Clinical Presentation

Back pain, changes in bladder function, and sexual dysfunction are the most common symptoms associated with male reproductive disorders. Any obstruction, growth, or inflammation of the prostate can directly affect the urethra, resulting in difficulty starting a flow of urine, continuing a flow of urine, frequency, and/or nocturia.

Prostate cancer is often asymptomatic and only diagnosed when the man seeks medical assistance because of symptoms of urinary obstruction or sciatica. Sciatic pain affects the low back, hip, and leg and is caused by metastasis to the bones of the pelvis, lumbar spine, or femur.

Associated symptoms may include melena, sudden moderate to high fever, chills, and changes in bowel or bladder function. Men who have reached the fifth decade or more are most commonly affected.

Testicular cancer presents most often as a painless swelling nodule in one gonad, noted incidentally by the client or his sexual partner. This is described as a lump or hardness of the testis, with occasional heaviness or a dull, aching sensation in the lower abdomen or scrotum. Acute pain is the presenting symptom in about 10% of affected men.

Involvement of the epididymis or spermatic cord may lead to pelvic or inguinal lymph node metastases, although most tumors confined to the testis itself will spread primarily to the retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Subsequent cephalad drainage may be to the thoracic duct and supraclavicular nodes. Hematogenous spread to the lungs, bone, or liver may occur as a result of direct tumor invasion.

In about 10% of affected individuals, dissemination along these pathways results in thoracic, lumbar, supraclavicular, neck, or shoulder pain or mass as the first symptom. Other symptoms related to this pathway of dissemination may include respiratory symptoms or GI disturbance.

As discussed earlier, back pain caused by neoplasm is typically progressive, is more pronounced at night, and may not have a clear association with activity level (as is more characteristic of mechanical back pain). The usual progression of symptoms in clients with cord compression is back pain followed by radicular pain, lower extremity weakness, sensory loss, and finally, loss of sphincter (bowel and bladder) control.

Associated Signs and Symptoms

Besides changes in urinary patterns, the therapist must ask about discharge from the penis, constitutional symptoms, and pain in any of the nearby soft tissue areas (groin, rectum, scrotum). Is there any blood in the urine (or change in color from yellow to orange or red)? Recurrent UTI is common in prostatitis but does not lead to prostate cancer.

Because the therapist is not going to be treating any of these problems, any red flags should be reported to the physician. A rectal exam may be needed. Access to the prostate is easiest through this type of exam. By pressing on the inflamed or infected prostate, the physician can reproduce painful symptoms as part of the differential diagnosis (see Fig. 10-5).

Many men are reluctant to pursue diagnosis and treatment whenever the male reproductive system is involved. Early detection and treatment of these conditions can result in a good outcome. Screening questions for men are a good way to elicit red-flag history, risk factors, and signs or symptoms. The therapist must follow up with the client and make sure contact is made with the appropriate health care professional.

Screening for Infectious Causes of Back Pain

Drug abuse, immune suppression, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) may predispose to infection. Fever in anyone taking immunosuppressants is a red flag symptom indicating a possible underlying infection. Many people with a spinal infection do not have a fever; they are more likely to have a red flag history or risk factors.1

Vertebral Osteomyelitis

Vertebral osteomyelitis is a bone infection most often affecting the first and second lumbar vertebrae, causing LBP. There are many causative factors. Osteomyelitis may occur in individuals with diabetes, injection drug users (IDUs), alcoholics, clients taking corticosteroid drugs, clients with spinal cord injury and neurogenic bladder, and otherwise debilitated or immune-suppressed clients. Older children can be affected, although the most common peak is after the third decade of life.

Vertebral osteomyelitis is increasingly being reported as a complication of nosocomial bacteremia. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is the most common causative organism. Osteomyelitis also can occur after surgery, open fractures, penetrating wounds, skin breakdown and ulcers, and systemic infections. It may result from a hematogenous spread through arterial and venous routes secondary to surgically implanted hardware for internal fixation of the spine, pelvic inflammatory disease, or genitourinary tract infection.

A physician should evaluate new onset of back pain in anyone who has been treated with vancomycin therapy for MRSA. Vancomycin therapy may give the appearance of being effective with resolution of fever and the return of white blood cell counts to normal ranges but in fact be insufficient to prevent or reverse the progression of hematogenous MRSA vertebral osteomyelitis.150,151

In the adult, usually two adjacent vertebrae and their intervening disk are involved, and the vertebral body(ies) may undergo destruction and collapse. Abscess formation may result, with possible neurologic involvement. The abscess can advance anteriorly to produce an abscess that can extend to the psoas muscle producing hip pain.

The most consistent clinical finding is marked local tenderness over the spinous process of the involved vertebrae with “nonspecific backache.” The classic history describes pain that has been increasing in severity over a period of 1 to 3 weeks. Movement is painful, and there is marked muscular guarding and spasm of the paravertebral muscles and the hamstrings. The involved vertebrae are usually exquisitely sensitive to percussion, and pain is more severe at night.

There may be no rise in temperature or abnormality in white blood cell count because generalized sepsis is not present, but an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is likely. A low-grade fever is most common in adults when body temperature changes do occur.

Children are more likely to present with acute, severe complaints including high fever, intense pain, and localized manifestations such as edema, erythema, and tenderness. Acute hematogenous osteomyelitis seen in children usually originates in the metaphysis of a long bone. Precipitating trauma is often present in the history, and well-localized, acute bone pain of 1 day to several days’ duration is the primary symptom. The pain is most commonly severe enough to limit or restrict the use of the involved extremity, and fever and malaise consistent with sepsis are usual.

Disk Space Infection

Disk space infection is a form of subacute osteomyelitis involving the vertebral end-plates and the disk in both children and adults. The lower thoracic and lumbar spines are the most common sites of infection.

Symptoms associated with postoperative disk space infection occur 2 to 8 weeks after diskectomy. Diskitis of an infectious type occurs following bacteremia secondary to UTI, with or without instrumentation (e.g., catheterization or cystoscopy). Low-grade viral or bacterial infection (e.g., gastroenteritis, upper respiratory infection, UTI) is most often implicated in young children with diskitis (4 years old and younger). Ask the parent, guardian, or caretaker of any young child with back pain if there has been a recent history of sore throat, cold, ear infection, or other upper respiratory illness.

Adults with disk space infection often complain of LBP localized around the disk area. The pain can range from mild to “excruciating” and sometimes is described as “knifelike.” Such severe pain is accompanied by restricted movement and constant pain, present both day and night. The pain is usually made worse by activity, but unlike most other causes of back pain, it is not relieved by rest. If the condition becomes chronic, pain may radiate into the abdomen, pelvis, and lower extremities.

Children present with a history of increasingly severe localized back pain often accompanied by a limp or refusal to walk. There may be an increased lumbar lordosis. Pain may occur in the flank, abdomen, or hip. Symptoms may get worse with passive SLR testing or other hip motion. A neurologic screening examination is usually negative.

Physical examination may reveal localized tenderness over the involved disk space, paraspinal muscle spasm, and restricted lumbar motion. SLR may be positive, and fever is common (Case Example 14-17).

Bacterial Endocarditis

Bacterial endocarditis often presents initially with musculoskeletal symptoms, including arthralgia, arthritis, LBP, and myalgias. Half of these clients will have only musculoskeletal symptoms, without other signs of endocarditis.

The early onset of joint pain and myalgia is more likely if the client is older and has had a previously diagnosed heart murmur or prosthetic valve (risk factors). Other risk factors include injection drug use, previous cardiac surgery, recent dental work, and recent history of invasive diagnostic procedures (e.g., shunts, catheters).

Almost one-third of clients with bacterial endocarditis have LBP. In many persons, LBP is the principal musculoskeletal symptom reported. Back pain is accompanied by decreased ROM and spinal tenderness. Pain may affect only one side, and it may be limited to the paraspinal muscles.

Endocarditis-induced LBP may be very similar to the pain pattern associated with a herniated lumbar disk; it radiates to the leg and may be accentuated by raising the leg, coughing, or sneezing. The key difference is that neurologic deficits are usually absent in clients with bacterial endocarditis. The therapist can review history and risk factors and conduct a Review of Systems to help in the screening process.

Physician Referral

Most adults with an episode of acute back pain experience recovery within 1 to 4 weeks. As many as 90% of affected individuals resume normal activity levels during this time.152,153

All clients who have not regained usual activity after 4 weeks should be formally reassessed, including a review of the history and examination, looking for yellow (caution) or red (warning) flags, testing for any neurologic deficit, and conducting a Review of Systems to identify any evidence of systemic disease or other medical condition requiring referral.

Reassessment of movement dysfunction is critical at this stage to look for alternate impairments not previously observed or identified. The therapist must consider whether the underlying primary problem is spinal or nonspinal, mechanical or medical, and what specific structures are involved.

Review concepts from the screening physical assessment in Chapter 4 to make sure the evaluation is complete. Inspection, palpation, and auscultation may reveal key findings previously missed. Assessment of fear-avoidance may be needed as discussed in Chapter 3. The therapist should not rely on his or her own perception of patient/client’s fear-avoidance behaviors. Tools such as the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ; see Table 3-7), Tampa Scale of Kinesophobia (TSK-11), and Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PSC) are available to identify fear-avoidance beliefs.154

Medical referral is made on the basis of a comparison of baseline data with findings upon reassessment. Providing the physician with concise but comprehensive information about findings and concerns is a helpful part of the medical differential diagnostic process.

Guidelines for Immediate Medical Attention

Immediate medical referral is not always required when a client presents with any one of the red flags listed in Box 14-1. When viewed as a whole, the history, risk factors, and any cluster of red flag findings will guide the therapist in making a final intervention versus referral decision.

• Neck pain with evidence of VBI (e.g., reproduction of symptoms with vertebral artery testing such as vertigo, visual changes, headaches, nausea) requires medical attention. VBI can develop into cerebral or brainstem ischemia, leading to severe morbidity or death.155

• Immediate medical attention is required when anyone with LBP presents with symptoms of cauda equina syndrome (e.g., saddle anesthesia, fecal incontinence, motor weakness of the legs, radiculopathy, unable to heel or toe walk, altered knee or ankle deep tendon reflexes). Acute mechanical compression of nerves in the lower extremities, bowel, and bladder as they pass through the caudal sac may be a surgical emergency.

• Massive midline rupture of a disk in the lower lumbar levels can lead to LBP, rapidly progressive bilateral motor weakness and sciatica, saddle anesthesia (buttock and medial and posterior thighs; the area that would come in contact with a saddle when sitting on a horse), and bowel and bladder incontinence or urinary retention.156

• Men between the ages of 65 and 75 who ever smoked should undergo medical screening for AAA. Any male with these two risk factors, especially presenting with signs or symptoms of AAA, must be referred immediately.

• Sudden, intense back and/or shoulder pain in a sexually active woman of childbearing age may signal the end of an ectopic pregnancy. Sudden change in blood pressure, pallor, pain, and dizziness will alert the therapist to the need for immediate medical attention.

• Inability to bear weight, especially with fever and/or a history of cancer, diabetes, immunosuppression, or trauma (even if radiographs have already been obtained and declared “negative”) [infection, fracture].

Guidelines for Physician Referral

• Red flags requiring physician referral or reevaluation include back pain or symptoms that are not improving as expected, steady pain irrespective of activity, symptoms that are increasing, or the development of new or progressive neurologic deficits such as weakness, sensory loss, reflex changes, bowel or bladder dysfunction, or myelopathy.

• A positive Sharp-Purser test for AA subluxation in the client with rheumatoid arthritis (sensation of head falling forward during neck flexion and clunking during neck extension) must be evaluated by an orthopedic surgeon.14

• The ESR, serum calcium level, and alkaline phosphatase level are usually elevated if bone cancer is present.157 Back pain in the presence of elevated alkaline phosphatase levels can also indicate hyperparathyroidism, osteomalacia, pregnancy, and/or rickets.

• Reproduction of pain or exquisite tenderness over the spinous process(es) is a red-flag sign requiring further investigation and possible medical referral.

Clues to Screening Head, Neck, or Back Pain

• Age younger than 20 and older than 50 with no history of a precipitating event

• Back pain in children is uncommon and constitutes a red-flag finding, especially back pain that lasts more than 6 weeks

• Nocturnal back pain that is constant, intense, and unrelieved by change in position

• Pain that causes constant movement or makes the client curl up in the sitting position

• Back pain with constitutional symptoms: Fatigue, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, fever, sweats

• Back pain accompanied by unexplained weight loss

• Back pain accompanied by extreme weakness in the leg(s), numbness in the groin or rectum, or difficulty controlling bowel or bladder function (cauda equina syndrome; rare but requires immediate medical attention)

• Back pain that is insidious in onset and progression (remember to assess for unreported sexual assault or physical abuse)

• Back pain that is unrelieved by recumbency

• Back pain that does not vary with exertion or activity

• Back pain that is relieved by sitting up and leaning forward (pancreas)

• Back pain that is accompanied by multiple joint involvement (GI, rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia) or by sustained morning stiffness (spondyloarthropathy)

• Severe, persistent back pain with full and painless movement of the spine

• Sudden, localized back pain that does not diminish in 10 days to 2 weeks in postmenopausal women or osteoporotic adults (osteoporosis with compression fracture)

Past Medical History

• Previous history of cancer, Crohn’s disease, or bowel obstruction

• Long-term use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (GI bleeding), steroids, or immunosuppressants (infectious cause)

• Recent history or previous history of recurrent upper respiratory infection or pneumonia

• Recent history of surgery, especially back pain 2 to 8 weeks after diskectomy (infection)

• History of osteoporosis and/or previous vertebral compression fracture(s) (fracture)

• History of heart murmur or prosthetic valve in an older client who currently has LBP of unknown cause (bacterial endocarditis)

• History of intermittent claudication and heart disease in a man with deep midlumbar back pain; assess for pulsing abdominal mass (AAA)

• History of diseases associated with hypercalcemia such as hyperparathyroidism, multiple myeloma, senile osteoporosis, hyperthyroidism, Cushing’s disease, or specific renal tubular disease not appearing with back pain radiating to the flank or iliac crest (kidney stone)

Oncologic

• Back pain with severe lower extremity weakness without pain, with full ROM and recent history of sciatica in the absence of a positive SLR

• Bilateral leg pain with motor and reflex impairments

• Bone tenderness over the spinous processes (infection or neoplasm)

• Temperature differences: Involved side warmer when tumor interferes with sympathetic nerves

• Associated signs and symptoms: significant weight loss; night pain disturbing sleep; extreme fatigue; constitutional symptoms such as fever, sweats; other organ/system-dependent symptoms such as urinary changes (urologic), cough, and dyspnea (pulmonary); abdominal bloating or bloody diarrhea (GI)

Cardiovascular

• Back pain that is described as “throbbing”

• Back pain accompanied by leg pain that is relieved by standing still or rest

• Back pain that is present in all spinal positions and increased by exertion

• Back pain accompanied by a pulsating sensation or palpable abdominal pulse (possibly a palpable pulsating abdominal mass)

• Low back, pelvic, and/or leg pain with temperature changes from one leg to the other (involved side warmer: Venous occlusion or tumor; involved side colder: arterial occlusion)

• Back injury that occurred during weight lifting in someone with known heart disease or past history of aneurysm

Pulmonary

• Associated signs and symptoms (dyspnea, persistent cough, fever and chills)

• Back pain aggravated by respiratory movements (deep breathing, laughing, coughing)

• Back pain relieved by breath holding or Valsalva maneuver

• Autosplinting by lying on the involved side or holding firm pillow against the chest/abdomen decreases the pain

• Spinal/trunk movements (e.g., trunk rotation, trunk side bending) do not reproduce symptoms (exception: An intercostal tear caused by forceful coughing from underlying diaphragmatic pleurisy can result in painful movement but is also reproduced by local palpation)

• Weak and rapid pulse accompanied by fall in blood pressure (pneumothorax)

Renal/Urologic

• Renal and urethral pain is felt throughout T9 to L1 dermatomes; pain is constant but may crescendo (kidney stones)

• Kidney pain of an inflammatory nature can be relieved by a change in position. However, renal colic (e.g., infection) remains unchanged by a change in position. But there are usually constitutional symptoms associated with either inflammation or infection to tip off the alert therapist.

• Back pain at the level of the kidneys can be caused by ovarian or testicular cancer

• Back pain and shoulder pain, either simultaneously or alternately, may be renal/urologic in origin

• Side bending to the same side and pressure placed along the spine at that level is “more comfortable”; pain may be reduced, but it is not eliminated when the kidney is involved. The client with kidney disease/disorder may prefer this position because it moves the kidney out away from the spine and away from any compressive forces causing painful symptoms.

• Associated signs and symptoms (blood in urine, fever, chills, increased urinary frequency, difficulty starting or continuing stream of urine, testicular pain in men, painful erection and/or ejaculation)

• Assess for costovertebral angle tenderness; pain is affected by change of position (pseudorenal pain)

• History of traumatic fall, blow, lift (musculoskeletal)

• Persistent back (pelvic, groin, or testicular) pain in a male with history of chronic prostatitis that does not respond to medical treatment such as antibiotics suggests the need to assess (or reassess) for pelvic floor impairment; watch for a history of improved symptoms without complete resolution with an orthopedic treatment approach

Gastrointestinal

• Back and abdominal pain at the same level (may occur simultaneously or alternately); check for GI history or associated signs and symptoms

• Back pain with abdominal pain at a lower level than the back pain; look for its source in the back

• Back pain associated with food or meals (increase or decrease in symptoms)

• Back pain accompanied by heartburn or relieved by antacids

• Associated signs and symptoms (dysphagia, odynophagia, melena, unexplained or unintended weight loss especially if accompanied by early satiety, abdominal distention, tenderness over McBurney’s point, positive iliopsoas or obturator sign, bloody diarrhea, nausea, vomiting)

• LBP accompanied by constipation may be a manifestation of pelvic floor overactivity or spasm; this requires a pelvic floor screening examination.

• Sacral pain occurs when the rectum is stimulated, such as during a bowel movement or when passing gas, and relieved after each of these events

Gynecologic

• History or current gynecologic disorder (e.g., uterine retroversion, ovarian cysts, uterine fibroids, endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, sexual assault/incest, IUCD, multiple births with prolonged labor or forceps use)

• Associated signs and symptoms (missed or irregular menses, tender breasts, cyclic nausea and vomiting, chronic constipation, vaginal discharge, abnormal uterine bleeding or bleeding in a postmenopausal woman)

• Low back and/or pelvic pain developing soon after a missed menstrual cycle; blood pressure may be significantly low, and there may be concomitant shoulder pain when hemorrhaging occurs (ectopic pregnancy)

• Low back and/or pelvic pain occurring intermittently but with regularity in response to menstrual cycle (e.g., ovulation around days 10 to 14 and onset of menses around days 23 to 28)

Nonorganic (Psychogenic) (see discussion in Chapter 3)

• Widespread, nonanatomic low back tenderness with overreaction to superficial palpation

• Assess for nonorganic signs such as axial loading (downward pressure on the top of the head) or shoulder-hip rotation (client rotates shoulder and hips with feet planted); Waddell’s nonorganic signs (see Table 3-12)

• Regional (whole leg) pain, numbness, weakness, sensory disturbances

Infectious

• Infection, such as osteomyelitis or inflammatory arthritis (e.g., ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic or reactive arthritis), may present as back pain with intermittent reports of fever, chills, sweats, fatigue, and/or adenopathy. Watch for other associated signs and symptoms specific to each condition (e.g., urethritis, psoriasis, severe morning stiffness).

Pediatrics

• Children presenting with back pain are very different from adults with the same problem; children are less likely than adults to report symptoms when there is no organic cause for the complaint.158

• Eighty-five percent of children with back pain lasting more than 2 months have a diagnosable lesion.159

• Children with persistent reports of LBP must be evaluated and reevaluated until a diagnosis is reached; x-rays and laboratory values are needed.

1. The most common sites of referred pain from systemic diseases are:

2. To screen for back pain caused by systemic disease:

a. Perform special tests (e.g., Murphy’s percussion, Bicycle test)

b. Correlate client history with clinical presentation and ask about associated signs and symptoms

3. What are two ways of classifying back pain (as presented in the text)?

4. Which statement is the most accurate?

a. Arterial disease is characterized by intermittent claudication, pain relieved by elevating the extremity, and history of smoking.

b. Arterial disease is characterized by loss of hair on the lower extremities, throbbing pain in the calf muscles that goes away by using heat and elevation.

c. Arterial disease is characterized by painful throbbing of the feet at night that goes away by dangling the feet over the bed.

d. Arterial disease is characterized by loss of hair on the toes, intermittent claudication, and redness or warmth of the legs that is accompanied by a burning sensation.

5. Pain associated with pleuropulmonary disorders can radiate to:

6. Which of the following are clues to the possible involvement of the GI system?

a. Abdominal pain alternating with TMJ pain within a 2-week period of time

b. Abdominal pain at the same level as back pain occurring either simultaneously or alternately

7. Percussion of the costovertebral angle resulting in the reproduction of symptoms signifies:

8. A 53-year-old woman comes to physical therapy with a report of leg pain that begins in her buttocks and goes all the way down to her toes. If this pain is of a vascular origin she will most likely describe it as:

9. Twenty-five percent of the people with GI disease, such as Crohn’s disease (regional enteritis), irritable bowel syndrome, or bowel obstruction, have concomitant back or joint pain.

10. Skin pain over T9 to T12 can occur with kidney disease as a result of multisegmental innervation. Visceral and cutaneous sensory fibers enter the spinal cord close to each other and converge on the same neurons. When visceral pain fibers are stimulated, cutaneous fibers are stimulated, too. Thus visceral pain can be perceived as skin pain.

11. Autosplinting is the preferred mechanism of pain relief for back pain caused by kidney stones.

12. Back pain from pancreatic disease occurs when the body of the pancreas is enlarged, inflamed, obstructed, or otherwise impinging on the diaphragm.

13. A 53-year-old postmenopausal woman with a history of breast cancer 5 years ago with mastectomy presents with a report of sharp pain in her mid-back. The pain started after she lifted her 2-year-old granddaughter 3 days ago. Tylenol seems to help, but the pain is keeping her awake at night. Once she wakes up, she cannot find a comfortable position to go back to sleep. What are the red flags? What will you do to screen for a medical cause of her symptoms?

References

1. Waddell, G. The back pain revolution, ed 2. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2004.

2. Jette, AM, Davis, KD. A comparison of hospital-based and private outpatient physical therapy practices. Phys Ther. 1991;71(5):366–381.

3. Jette, AM, Smith, K, Haley, SM, et al. Physical therapy episodes of care for patients with low back pain. Phys Ther. 1994;74(2):101–115.

4. Freburger, JK, Carey, TS, Holmes, GM. Management of back and neck pain: who seeks care from physical therapists? Phys Ther. 2005;85(9):872–886.

5. Deyo, RA, Weinstein, JN. Low back pain. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(5):363–370.

6. Jarvik, J, Deyo, R. Diagnostic evaluation of low back pain with emphasis on imaging. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:586–597.

7. Spitzer, WO. Quebec Task Force on Spinal Disorders: Scientific approach to the assessment and management of activity-related spinal disorders: a monograph for clinicians. Spine. 1987;12(suppl 1):51–59.

8. Sembrano, JN, Polly, DW. How often is low back pain not coming from the back? Spine. 2009;34:E27–E32.

9. Bernard, TN, Jr., Kirkaldy-Willis, WH. Recognizing specific characteristics of nonspecific low back pain. Clin Orthop. 1987;217:266–280.

10. Shaw, JA. The role of the sacroiliac joint as a cause of low back pain and dysfunction. In: Vleeming A, Mooney V, Snijders C, et al, eds. The First Interdisciplinary World Congress on low back pain and its relation to the sacroiliac joint. Rotterdam, Netherlands: ECO; 1992:67–80.

11. Depalma, MJ. What is the source of chronic low back pain and does age play a role? Pain Med. 2011;12(2):224–233.

12. Vora, AJ. Functional anatomy and pathophysiology of axial low back pain: discs, posterior elements, sacroiliac joint, and associated pain generators. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2010;21(4):679–709.

13. Vanelderen, P. Sacroiliac joint pain. Pain Pract. 2010;10(5):470–478.

14. Kim, DH, Hilibrand, AS. Rheumatoid arthritis in the cervical spine. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005;13(7):463–474.

15. Magarelli, N. MR imaging of atlantoaxial joint in early rheumatoid arthritis. Radiol Med. 2010;115(7):1111–1120.

16. Krauss, WE. Rheumatoid arthritis of the craniovertebral junction. Neurosurgery. 2010;66(3 Suppl):83–95.

17. Guzman, J. A new conceptual model of neck pain. Spine. 2008;33(4S):S14–S23.

18. Boissonnault, WG, Koopmeiners, MB. Medical history profile: orthopaedic physical therapy outpatients. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1994;20:2–10.

19. Boissonault, WG. Prevalence of comorbid conditions, surgeries, and medication use in a physical therapy outpatient population: a multi-centered study. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1999;29:506–519. [discussion 520–525].

20. Boissonnault, WG, Meek, PD. Risk factors for antiinflammatory drug or aspirin induced gastrointestinal complications in individuals receiving outpatient physical therapy services. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2002;32:510–517.

21. Biederman, RE. Pharmacology in rehabilitation: non-steroidal antiinflammatory agents. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2005;35:356–367.

21a. Daniels, JM. Evaluation of low back pain in athletes. Sports Health. 2011;3(4):336–345.

22. Witkin, LR. Abscess after a laparoscopic appendectomy presenting as low back pain in a professional athlete. Sports Health. 2011;3(1):41–45.

23. Cosar, M. The major complications of transpedicular vertebroplasty. J Neurosurg: Spine. 2009;11(5):607–613.

24. Johnson, BA. Epidurography and therapeutic epidural injections: technical considerations and experience with 5334 cases. Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:697–705.

25. Davenport, TE. Subcutaneous abscess in a patient referred to physical therapy following spinal epidural injection for lumbar radiculopathy. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38(5):287.

26. van den Bosch, MAAJ. Evidence against the use of lumbar spine radiography for low back pain. Clin Radiol. 2004;59:69–76.

27. Bishop, PB, Wing, PC. Compliance with clinical practice guidelines in family physicians managing worker’s compensation board patients with acute lower back pain. Spine J. 2003;3(6):442–450.

28. Bishop, PB, Wing, PC. Knowledge transfer in family physicians managing patients with acute low back pain: a prospective randomized control trial. Spine J. 2006;6(3):282–288.

29. Leerar, PJ, Boissonnault, W, Domholdt, E, et al. Documentation of red flags by physical therapists for patients with low back pain. J Man Manip Ther. 2007;15(1):42–49.

30. Bogduk, N, McQuirk, B. Medical management of acute and chronic low back pain: an evidence based approach. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2002.

31. Burton, AK. Psychosocial predictors of outcome in acute and subchronic low back trouble. Spine. 1995;20:722–728.

32. McCarthy, CJ. The reliability of the clinical tests and questions recommended in International Guidelines for Low Back Pain. Spine. 2007;32(6):921–926.

33. Moore, JE. Chronic low back pain and psychosocial issues. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2010;21(4):801–815.

34. Kendall, NAS, Linton, SJ, Main, CJ. Guide to assessing psychosocial yellow flags in acute low back pain: risk factors for long-term disability and work loss. Wellington, New Zealand: Accident Rehabilitation and Compensation Insurance Corporation of New Zealand and the National Health Committee; 1998.

34a. Burns, SA. A treatment-based classification approach to examination and intervention of lumbar disorders. Sports Health. 2011;3(4):363–372.

34b. George, SZ, Fritz, JM, Childs, JD. Investigation of elevated fear-avoidance beliefs for patients with low back pain: a secondary analysis involving patients enrolled in physical therapy clinical trials. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38(2):50–58.

35. Bogduk, N. Evidence-based clinical guidelines for the management of acute low back pain: The national musculoskeletal medicine initiative. Australia: Australian Association of Musculoskeletal Medicine; 2002.

36. Henschke, N. Prevalence of and screening for serious spinal pathology in patients presenting to primary care settings with acute low back pain. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(10):3072–3080.

37. Sizer, PS, Brismee, JM, Cook, C. Medical screening for red flags in the diagnosis and management of musculoskeletal spine pain. Pain Pract. 2007;7(1):53–71.

38. Henschke, N. A systematic review identifies five “red flags” to screen for vertebral fracture in patients with low back pain. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:110–118.

39. Papaionnou, A. Diagnosis and management of vertebral fractures in elderly adults. Am J Med. 2002;113:220–228.

40. Grigoryan, M. Recognizing and reporting osteoporotic vertebral fractures. Eur Spine J. 2003;12(Suppl 2):S104–S112.

41. Sanpera, I. Bone scan as a screening tool in children and adolescents with back pain. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26(2):221–225.

42. Feldman, DS. The use of bone scan to investigate back pain in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;20:790–795.

43. Taimela, S. The prevalence of low back pain among children and adolescents: a nationwide, cohort-based questionnaire survey in Finland. Spine. 1997;22:1132–1136.

43a. Micheli, LJ. Back pain in young athletes: significant differences from adults in causes and patterns. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995;149(1):15–18.

43b. Bhatia, N. Diagnostic modalities for the evaluation of pediatric back pain: a prospective study. J Pediatr Orthop. 2008;28(2):230–233.

43c. Nigrovic, PA. Evaluation of the child with back pain. http:www.uptodate.com/index, 2010. [Accessed July 15, 2011 Published January 25].

44. Deyo, RA, Diehl, AK. Lumbar spine films in primary care: current use and effects of selective ordering criteria. J Gen Intern Med. 1986;1:20–25.

45. Royal College of General Practitioners. Clinical guidelines of the management of acute low back pain. National Low Back Pain Clinical Guidelines; 1997.

46. Leon-Diaz, A, Gonzalez-Rabelino, G, Alonso-Cervino, M. Analysis of the etiologies of headaches in a pediatric emergency service. Rev Neurol. 2004;39(3):217–221. [1–15].

47. Olesen, J, Steiner, TJ. The international classification of headache disorders, ed 2 (ICHD-II). J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(6):808–811.

48. Silberstein, SD, Olesen, J, Bousser, MG, et al. The international classification of headache disorders, ed 2 (ICHD-II)—revision of criteria for 8.2 medication overuse headache. Cephalalgia. 2005;25(6):460–465.

49. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgias, and facial pain. Cephalalgia. 1988;8(Suppl 7):1–96.

50. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgias and facial pain, ed 2 (revised). Cephalalgia. 2004;25(12):460–465.

51. Petersen, SM. Articular and muscular impairments in cervicogenic headache. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2003;33(1):21–30.

52. Agostoni, E. Headache in cerebral venous thrombosis. Neurol Sci. 2004;25(suppl 3):S206–S210.

53. Agostoni, E, Aliprandi, A. Alterations in the cerebral venous circulation as a cause of headache. Neurol Sci. 2009;30(suppl 1):S7–S10.

54. Jacobson, SA, Folstein, MF. Psychiatric perspectives on headache and facial pain. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2003;36(6):1187–1200.

55. Farmer, K. Psychologic factors in childhood headaches. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2010;17(2):93–99.

56. Hering-Hanit, R, Gadoth, N. Caffeine-induced headache in children and adolescents. Cephalalgia. 2003;23(5):332–335.

57. Ryan, LM, Warden, DL. Post concussion syndrome. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2003;15(4):310–316.

58. Seiffert, TD, Evans, RW. Posttraumatic headache: a review. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2010;14(4):292–298.

59. Phillips, E, Levine, AM. Metastatic lesions of the upper cervical spine. Spine. 1989;14(10):1071–1077.

60. O’Reilly, MB. Nonresectable head and neck cancer. Rehab Oncology. 2004;22(2):14–16.

61. Neville, BW, Day, TA. Oral cancer and precancerous lesions. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002;52(4):195–215.

62. Purdy, RA, Kirby, S. Headaches and brain tumors. Neurol Clin. 2004;22(1):39–53.

63. Kirby, S. Headache and brain tumours. Cephalalgia. 2010;30(4):387–388.

64. Valentinis, L. Headache attributed to intracranial tumours: a prospective cohort study. Cephalalgia. 2010;30(4):389–398.

65. Narin, SO, Pinar, L, Erbas, D, et al. The effects of exercise and exercise-related changes in blood nitric oxide level on migraine headache. Clin Rehabil. 2003;17(6):624–630.

66. Sandor, PS, Afra, J. Nonpharmacologic treatment of migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2005;9(3):202–205.

67. Andrasik, F. Biofeedback in headache: an overview of approaches and evidence. Cleve Clin J Med. 2010;77(Suppl 3):S72–S76.

68. Biondi, DM. Physical treatments for headache: a structured review. Headache. 2005;45(6):738–746.

69. Gorski, JM, Schwartz, LH. Shoulder impingement presenting as neck pain. J Bone Joint Surg. 2003;85A(4):635–638.

70. Lee, L, Elliott, R. Cervical spondylotic myelopathy in a patient presenting with low back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38(12):798.

71. Cook, C. Reliability and diagnostic accuracy of clinical tests for myelopathy in patients seen for cervical dysfunction. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009;39(3):172–178.

72. Slipman, CW, Issac, Z, Patel, R, et al. Chronic neck pain: the specific syndromes. J Musculoskel Med. 2003;20(1):24–33.

73. Koopmeiners, MB, Personal communication, 2003.

74. Boissonnault, WG, Personal communication, 2003.

75. Kerry, R. Manual therapy and cervical arterial dysfunction, directions for the future: a clinical perspective. J Man Manip Ther. 2008;16(1):39–48.

76. Kerry, R, Taylor, AJ. Cervical arterial dysfunction assessment and manual therapy. Man Ther. 2006;11:243–253.

77. Kerry, R, Taylor, AJ. Cervical arterial dysfunction: knowledge and reasoning for manual physical therapists. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009;39(5):378–387.

78. Mooney, V, Robertson, J. The facet syndrome. Clin Orthop. 1976;115:149–156.

79. Fruth, SJ. Differential diagnosis and treatment in a patient with posterior upper thoracic pain. Phys Ther. 2006;86(2):154–268.

80. Hartvigsen, J, Christensen, K, Frederiksen, H. Back pain remains a common symptom in old age. A population-based study of 4,486 Danish twins aged 70-102. Eur Spine J. 2003;12(5):528–534.

80a. Braun, J, Inman, R. Clinical significance of inflammatory back pain for diagnosis and screening of patients with axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(7):1264–1268.

81. O’Neill, CW, Kurgansky, ME, Derby, R, et al. Disc stimulation and patterns of referred pain. Spine. 2002;27(24):2776–2781.

82. Koes, BW. Diagnosis and treatment of sciatica. BMJ. 2007;334:1313–1317.

83. Crowell, MS, Gill, NW. Medical screening and evacuation: cauda equina syndrome in a combat zone. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009;39(7):541–549.

84. O’Laughlin, SJ, Kokosinski, E. Cauda equina syndrome in a pregnant woman referred to physical therapy for low back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38(11):721.

85. McCarthy, MJH. Cauda equina syndrome: Factors affecting long-term functional and sphincteric outcome. Spine. 2007;32(2):207–216.

86. Kauppila, LI. Atherosclerosis and disc degeneration/low-back pain—a systematic review. Eur J Endovasc Surg. 2009;37(6):661–670.

87. Bingol, H, Cingoz, F, Yilmaz, AT, et al. Vascular complications related to lumbar disc surgery. J Neurosurg: Spine. 2004;100(3):249–253.

88. Lacombe, M. Vascular complications of lumbar disk surgery. Ann Chir. 2006;131(10):583–589.

89. Kauppila, LI, Mikkonen, R, Mankinen, P, et al. MR aortography and serum cholesterol levels in patients with long-term nonspecific lower back pain. Spine. 2004;29(19):2147–2152.

90. Silverman, SL. The clinical consequences of vertebral compression fracture. Bone. 1992;13:S27–S31.

91. Badke, MB, Boissonnault, WG. Changes in disability following physical therapy intervention for patients with low back pain: dependence on symptom duration. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2006;87(6):749–756.

92. Whooley, MA. Case-finding instruments for depression. Two questions are as good as many. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:439–445.

93. Haggman, S. Screening for symptoms of depression by physical therapists managing low back pain. Phys Ther. 2004;84:1157–1165.

94. Hoogendoorn, WE, van Poppel, MN, Bongers, PM, et al. Systematic review of psychosocial factors at work and private life as risk factors for back pain. Spine. 2000;25:2114–2125.

95. Marras, WS, Davis, KG, Heaney, CA, et al. The influence of psychosocial stress, gender, and personality on mechanical loading of the lumbar spine. Spine. 2000;25(23):3045–3054.

96. Thorbjornsson, CO, Alfredsson, L, Fredriksson, K, et al. Physical and psychosocial factors related to low back pain during a 24-year period. Occup Environ Med. 1998;55(2):84–90.

97. McCarthy, CJ. The reliability of the clinical tests and questions recommended in International Guidelines for Low Back Pain. Spine. 2007;32(6):921–926.

98. Ramond, A. Psychosocial risk factors for chronic low back pain in primary care—a systematic review. Fam Prac. 2011;28(1):12–21.

99. van Tulder, M, European guidelines for the management of acute nonspecific low back pain in primary care. European Commission, Geneva. European Spine Journal. 2006;15;Suppl 2:S169–S191. 6Available on-line at http://www.backpaineurope.org/. [Accessed December 1, 2010].

100. Kendall, NAS, Linton, SJ, Main, CJ. Guide to assessing psychological yellow flags in acute low back pain: risk factors for long-term disability and work loss. Wellington, New Zealand: Accident Rehabilitation and Compensation Insurance Corporation of New Zealand and the National Health Committee; 1997.

101. Borkan, J, Van Tulder, M, Reis, S, et al. Advances in the field of low back pain in primary care. A report from the Fourth International Forum. Spine. 2002;27(5):E128–E132.

102. Slipman, C. Epidemiology of spine tumors presenting to musculoskeletal physiatrists. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:492–495.

103. Rose, PS, Buchowski, JM. Metastatic disease in the thoracic and lumbar spine: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19(1):37–48.

104. Henschke, N. Screening for malignancy in low back pain patients: a systematic review. Eur Spine J. 2007;16(10):1673–1679.

105. Briggs, HK. The physical therapist’s management of a patient with low back pain following an atypical response to treatment: a case report. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2011;41(1):A16.

106. Mazanec, DJ, Segal, AM, Sinks, PB. Identification of malignancy in patients with back pain: red flags. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36(suppl):S251–S258.

107. Skoffer, B. Low back pain in 15- to 16-year-old children in relation to school furniture and carrying of the school bag. Spine. 2007;32(24):E713–E717.

108. Neuschwander, TB. The effect of backpacks on the lumbar spine in children. Spine. 2009;35(1):83–88.

109. Patchell, RA. Direct decompressive surgical resection in the treatment of spinal cord compression caused by metastatic cancer: a randomized trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9486):643–648.

110. Rex, L. Evaluation and treatment of somatovisceral dysfunction of the gastrointestinal system. Edmonds WA: URSA Foundation; 2004.

111. Deyo, RA, Diehl, AK. Cancer as a cause of back pain: frequency, clinical presentation, and diagnostic strategies. J Gen Intern Med. 1988;3(3):230–238.

112. Wong, DA, Fornasier, VL, MacNab, I. Spinal metastases: the obvious, the occult, and the imposters. Spine. 1990;15(1):1–4.

113. Ross, MD, Bayer, E. Cancer as a cause of low back pain in a patient seen in a direct access physical therapy setting. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2005;35(10):651–658.

114. Cosford PA, Leng GC: Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 18(2):CD002945, 2007.

115. Fleming, C, Whitlock, EP, Beil, TL, et al. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: a best evidence systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(3):203–211.

116. Lederle, FA. Smokers’ relative risk for aortic aneurysm compared with other smoking-related diseases: a systematic review. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:329–334.

117. Dua, MM, Dalman, RL. Identifying aortic aneurysm risk factors in postmenopausal women. Womens Health. 2009;5(1):33–37.

118. Lederle, FA. Abdominal aortic aneurysm events in the women’s health initiative: cohort study. BMJ. 2008;337:1724–1734.

119. Mofidi, R. Influence of sex on expansion rate of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Brit J Surg. 2007;94:310–314.

120. Wanhainen, A, Lundkvist, J, Bergqvist, D, et al. Cost-effectiveness of screening women for abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 2006;43:908–914.

121. Dyck, P, Doyle, JB. “Bicycle test” of van Gelderen in diagnosis of intermittent cauda equina compression syndrome. J Neurosurg. 1977;46:667–670.

122. Dyck, P. The stoop-test in lumbar entrapment radiculopathy. Spine. 1979;4:89–92.

123. Yung, E. Screening for head, neck, and shoulder pathology in patients with upper extremity signs and symptoms. J Hand Ther. 2010;23(2):173–186.

124. Eskelinen, M. Usefulness of history-taking, physical examination and diagnostic scoring in acute renal colic. Eur Urol. 1998;34(6):467–473.

125. Houppermans, RP, Brueren, MM. Physical diagnosis—pain elicited by percussion in the kidney area. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2001;145(5):208–210.

126. Herkowitz HN, ed. The spine. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1999.

127. Sex and back pain video. Dixfield, Maine, IMPACC, Inc. Available at www.impaccusa.com. [Accessed March 9, 2011].

128. Sex and back pain patient manual. Dixfield, ME, IMPACC, Inc. Available at www.impaccusa.com. [Accessed March 9, 2011].

129. Padua, L, Caliandro, P, Aprile, I, et al. Back pain in pregnancy. Eur Spine J. 2005;14(2):151–154.

130. Borg-Stein, J, Dugan, SA, Gruber, J. Musculoskeletal aspects of pregnancy. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;84(3):180–192.

131. Quaresma, C. Back pain during pregnancy: a longitudinal study. Acta Rheumatol Port. 2010;35(3):346–351.

132. Han, IH. Pregnancy and spinal problems. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;22(6):477–481.

133. Macarthur, AJ. Is epidural anesthesia in labor associated with chronic low back pain? A prospective cohort study. Anesth Analg. 1997;85(5):1066–1070.

134. Leighton, BL, Halpern, SH. The effects of epidural analgesia on labor, maternal, and neonatal outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(5 Suppl Nature):S69–S77.

135. Deevey, S. Endometriosis: Internet resources. Medical Ref Serv Quart. 2005;24(1):67–77.

136. Jones, KD, Sutton, CJ. Recurrence of chocolate cysts after laparoscopic ablation. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2002;9(3):315–320.

137. Giudice, LC, Kao, LC. Endometriosis. Lancet. 2004;364(9447):1789–1799.

138. Sarma, D. Cerebellar endometriosis. Am Roentgen Ray Society. 2004;182:1543–1546.

139. Carrell DT, Peterson CM, eds. Reproductive endocrinology and infertility. New York: Springer Science, 2010.

140. Sinaii, N, Cleary, SD, Ballweg, ML, et al. High rates of autoimmune and endocrine disorders, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, and atopic diseases among women with endometriosis: a survey analysis. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(10):2715–2724.

141. Sundqvist, J. Endometriosis and autoimmune disease. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(1):437–440.

142. Barrier, BF. Immunology of endometriosis. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;53(2):397–402.

143. Nissenblatt, M. Endometriosis-associated ovarian carcinomas. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(5):482–485.

144. Svendsen, PF, Nilas, L, Norgaard, K, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome. New pathophysiological discoveries. Ugeskr Laeger. 2005;167(34):3147–3151.

145. Dokras, A, Bochner, M, Hollinrake, E, et al. Screening women with polycystic ovary syndrome for metabolic syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(1):131–137.

146. Wild, RA. Assessment of cardiovascular risk and prevention of cardiovascular disease in women with the polycystic ovary syndrome: a consensus statement by the Androgen Excess and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Society. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(5):2038–2049.

147. Siegel, R, et al. Cancer statistics 2011. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:212–236.

148. Swan, J. Data and trends in cancer screening in the United States. Cancer. 2010;116(20):4872–4881.

149. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prostate cancer: statistics. Available online at http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/prostate/. [Accessed March 9, 2011].

150. Gelfand, MS, Cleveland, KO. Vancomycin therapy and the progression of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus vertebral osteomyelitis. South Med J. 2004;97(6):593–597.

151. Van Hal, SJ. Emergence of daptomycin resistance following vancomycin-unresponsive Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia in a daptomycin-naive patient—a review of the literature. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;30(5):603–610.

152. Patel, RK, Everett, CR. Low back pain: 20 clinical pearls. J Musculoskel Med. 2003;20(10):452–460.

153. Walton, DM. Recovery from acute injury: clinical, methodological and philosophical considerations. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(10):864–874.

154. Calley, D. Identifying patient fear-avoidance beliefs by physical therapists managing patients with low back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2010;40(12):774–783.

155. Asavasopon, S, Jankoski, J, Godges, JJ. Clinical diagnosis of vertebrobasilar insufficiency: resident’s case problem. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2005;35(10):645–650.

156. Wiesel, BB, Wiesel, SW. Radiographic evaluation of low back pain: a cost-effective approach. J Musculoskel Med. 2004;21(10):528–538.

157. Mazanec, DJ. Recognizing malignancy in patients with low back pain. J Musculoskel Med. 1996;13(1):24–31.

158. King, H. Evaluating the child with back pain. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1986;33(6):1489–1493.

159. Behrman R, Kliegman RM, Arvin AM, eds. Nelson’s textbook of pediatrics, ed 17, Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2004.

160. McTimoney, CA, Micheli, LJ. Managing back pain in young athletes. J Musculoskel Med. 2004;21(2):63–69.

161. Goode, B. Personal communication. Raleigh, NC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2006.

162. Knight, D. Health care screening for men who have sex with men. Amer Fam Phys. 2004;69(9):2149–2156.

163. Ozgen, S. Lumbar disc herniation in adolescence. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2007;43:77–81.

164. Seeman, E. The dilemma of osteoporosis in men. Am J Med. 1995;98(2A):765S–788S.

165. Orwoll, ES, Klein, RF. Osteoporosis in men. Endocr Rev. 1995;16:87–116.

166. Kiebzak, G, Beinart, G, Perser, K, et al. Undertreatment of osteoporosis in men with hip fracture. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(19):2217–2222.

167. Ebeling, PR. Osteoporosis in men. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(14):1474–1482.

168. Ebeling, PR. Androgens and osteoporosis. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2010;17(3):284–292.

169. Blain, H. Osteoporosis in men: epidemiology, physiopathology, diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. Rev Med Interne. 2005;25(suppl 5):S552–S559.

Key Points to Remember

Key Points to Remember