Screening the Sacrum, Sacroiliac, and Pelvis

Following the model for decision making in the screening process outlined in Chapter 1 (see Box 1-7), we now turn our attention to pain from medical conditions, illnesses, and diseases referred to the sacrum, sacroiliac (SI), and pelvic regions.

The basic premise is that physical therapists must be able to identify signs and symptoms of systemic origin or associated with medical conditions that can mimic neuromuscular or musculoskeletal (neuromusculoskeletal [NMS]) impairment in these areas.

In the screening process, therapists will watch for yellow (caution) or red (warning) flags to direct them. Clinicians rely on special questions to ask men and women with significant risk factors, significant past medical history, suspicious clinical presentation, or associated signs and symptoms.

With a careful interview and the right screening questions, the therapist can identify clues suggestive of a problem outside the scope of a physical therapist’s practice that may require medical referral. Specific tests to screen for an underlying infectious or inflammatory source of pelvic or abdominal pain are also presented with a suggested order of testing.

When dealing with painful symptoms of the sacral and pelvic areas, the therapist may need to ask questions about sexual history or sexual practices. The therapist must remain aware of facial expressions, body language, and verbal remarks in response to a client’s answers to these questions.

The therapist must be prepared to respond in a professional and responsible way if a man or woman with pelvic or sacral pain reports that he or she has been the victim of repeated violent sexual acts, or if a client admits to physical or emotional assault. More about the client interview, the screening interview, and screening for assault and domestic (intimate partner) violence is included in Chapter 2 (see also Appendices B-3 and B-32).

The Sacrum and Sacroiliac Joint

Evaluating the SI joint can be difficult in that no single physical examination finding can predict a disorder of the SI joint. Pain originating from the SI joint can mimic pain referred from lumbar disk herniation, spinal stenosis, facet joint impairment, or even a disorder of the hip.1-3

The most common clinical presentation of sacroiliac pain is associated with a memorable physical event that initiated the pain such as a misstep off a curb, a fall on the hip or buttocks, lifting of a heavy object in a twisted position, or childbirth (Case Example 15-1). A history of previous spine surgery is very common in clients with SI intraarticular pain.1

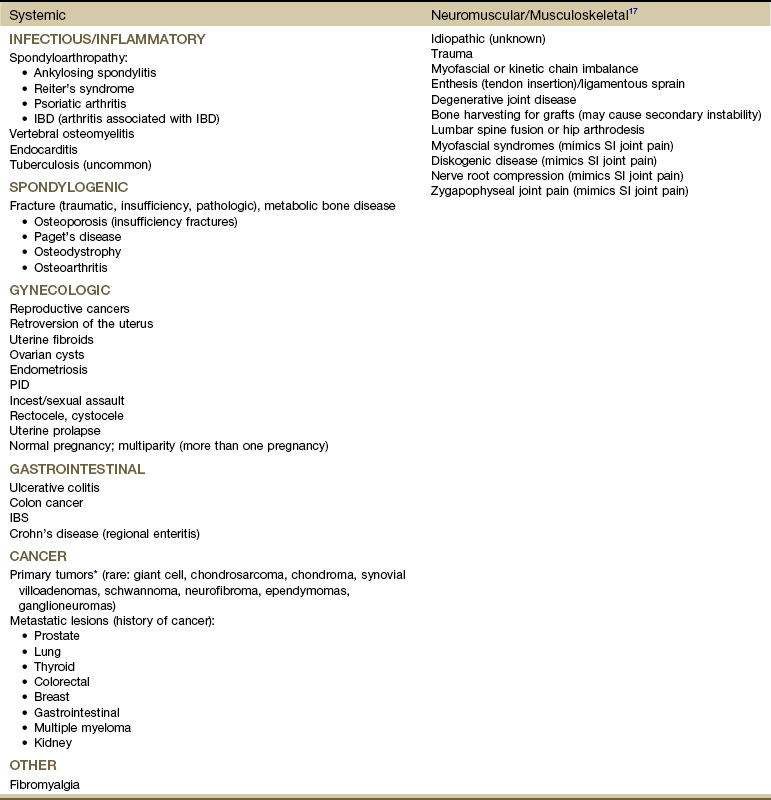

The most typical medical conditions that refer pain to the sacrum and SI joint include endocarditis, prostate cancer or other neoplasm,4 gynecologic disorders, rheumatic diseases that target the SI area (e.g., spondyloarthropathies such as ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter’s syndrome, or psoriatic arthritis), and Paget’s disease (Table 15-1).5

TABLE 15-1

Causes of Sacral and Sacroiliac Pain

IBD, Inflammatory bowel disease; SI, sacroiliac; PID, pelvic inflammatory disease; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome.

*Includes benign and malignant osseous and neurogenic tumors affecting the sacrum.

Disorders of the large intestine and colon, such as ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease (regional enteritis), carcinoma of the colon, and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), can refer pain to the sacrum when abscess develops or when the rectum is stimulated.6 Likewise, primary SI problems can refer pain to the lower abdomen.7

A medical differential diagnosis may be needed to exclude fracture, infection, or tumor. Insufficiency fractures of the sacrum can occur after pelvic radiotherapy for cancer8 and in osteoporotic bone with minimal or unremembered trauma.9 (See further discussion in this chapter on spondylogenic causes of sacral pain.)

Using the Screening Model to Evaluate Sacral/Sacroiliac Symptoms

The principles guiding evaluation of SI joint or sacral pain are consistent with the information presented throughout this text and, in particular, in the chapter on back pain (see Chapter 14).

Each of the disorders listed in Table 15-1 usually has its own unique clinical presentation with clues available in the past medical history. The presence of associated signs and symptoms is always a red flag. Most of these conditions have clear red flag clues that come to light if the client is interviewed carefully.

Clinical Presentation

Insidious onset or unknown cause is always a red flag. Without a clear cause, the therapist looks for something else in the history or accompanying signs and symptoms. Even with a known or assigned cause, it is important to keep other possibilities in mind and to watch for red flags (Box 15-1). Sacral pain in the absence of a history of trauma or overuse is a clue to the presentation of systemic backache.

The amount and direction of pain radiation can offer helpful clues. Low back or sacral pain radiating around the flank suggests the renal or urologic system. In such cases, the therapist should ask questions about bladder or urologic function.

Low back or sacral pain radiating to the buttock or legs may be vascular. Questions about the effects of activity on symptoms and history of cardiovascular or peripheral vascular diseases are important (see discussion in Chapter 14). Sorting out pain of a vascular versus neurogenic cause is also discussed in Chapter 14.

Most commonly, unless pain causes muscle spasm, splinting, and subsequent biomechanical changes, clients affected by systemic, medical, or viscerogenic causes of sacral or SI pain demonstrate a remarkable lack of objective findings to implicate the SI joint or sacrum as the causative factor for the presenting symptoms. Pain elicited by pressing on the sacrum with the client in a prone position suggests sacroiliitis (inflammation of the SI joint) or mechanical derangement.

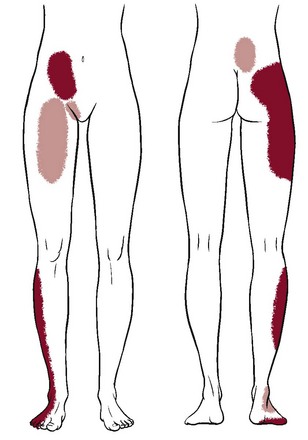

Sacroiliac Joint Pain Pattern: Whether from a mechanical or a systemic origin, the patient usually experiences pain over the posterior SI joint and buttock, with or without lower extremity pain. Pain may be unilateral or bilateral (Fig. 15-1)10 and can be referred to a wide referral zone, including the lumbar spine, abdomen, groin, thigh, foot, and ankle.1,11

Fig. 15-1 Unilateral sacroiliac (SI) pain pattern. Pain coming from the sacroiliac joint is usually centered over the area of the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS), with tenderness directly over the PSIS. Lower lumbar pain occurs in 72% of cases; it rarely presents as upper lumbar pain above L5 (6%). It may radiate over the buttocks (94%), down the posterior–lateral thigh (50%), and even past the knee to the ankle (14%) and lateral foot (8%). Paresthesias in the leg are not a typical feature of SI joint pain. The affected individual may report abdominal (2%), groin or pubic (14%), or anterior thigh pain (10%). Anterior symptoms may occur alone or in combination with posterior symptoms. Occasionally, a client will report bilateral pain. (Data from Slipman CW, Jackson HB, Lipetz JS, et al: Sacroiliac joint pain referral zones, Arch Phys Med Rehab 81:334-338, 2000.)

Clients with SI joint pain rarely have pain at or above the level of the L5 spinous process, although it is possible. The presence of midline lumbar pain tends to exclude the SI joint as a potential pain generator.12,13

A wide range of SI joint–referred pain patterns occur because innervation is highly variable and complex or because pain may be somatically referred, as discussed in Chapter 3. Adjacent structures, such as the piriformis muscle, sciatic nerve, and L5 nerve root, may be affected by intrinsic joint disease and can become active nociceptors. Pain referral patterns also may be dependent on the distinct location of injury within the SI joint.13,14

SI pain can mimic diskogenic disease with radicular pain down the leg to the foot.15 People who report midline lumbar pain when they rise from a sitting position are likely to have diskogenic pain. Clients with unilateral pain below the level of the L5 spinous process and pain when they rise from sitting are likely to have a painful SI joint.12,13

Pain from SI joint syndrome may be aggravated by sitting or lying on the affected side. Pain gets worse with prolonged driving or riding in a car, weight bearing on the affected side, the Valsalva maneuver, and trunk flexion with the legs straight.14

SI pain can also mimic the pain pattern of kidney disease with anterior thigh pain, but with SI impairment, no signs and symptoms (e.g., constitutional symptoms, bladder dysfunction) are associated, as would be the case with thigh pain referred from the renal system.

Screening for Infectious/Inflammatory Causes of Sacroiliac Pain

Joint infections spread hematogenously through the body and can affect the SI joint. Usually, the infection is unilateral and is caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, Cryptococcus organisms, or Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Risk factors for joint infection include trauma, endocarditis, intravenous drug use, and immunosuppression. Postoperative infection of any kind may not appear with any clinical signs or symptoms for weeks or months. Infections causing bacterial sacroiliitis as a complication of dilatation and curettage (D and C) after incomplete abortions have been reported.16

Infection can cause distention of the anterior joint capsule, irritating the lumbosacral nerve roots.17 Inflammation of the SI joint may result from metabolic, traumatic, or rheumatic causes. Sacroiliitis is present in all individuals with ankylosing spondylitis.18

Rheumatic Diseases as a Cause of Sacral or Sacroiliac Pain

The most common systemic causes of sacral pain are noninfected, inflammatory erosive rheumatic diseases that target the SI, including ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter’s syndrome, psoriatic arthritis, and arthritis associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) such as regional enteritis (Crohn’s disease).

Reiter’s syndrome (see Chapter 12) occurs most often in young men with venereal disease. Reiter’s syndrome often presents as a triad of symptoms, including arthritis, conjunctivitis, and urethritis. These three symptoms in the presence of sacral pain raise a red flag. The therapist must ask about pain in other joints, urologic symptoms, and a recent (or current) history of conjunctivitis (red, painful inflammation of the eye).

A positive sexual history or known diagnosis of venereal disease is helpful information. With sacral or SI pain, the therapist should always consider taking a sexual history (see Special Questions to Ask in Chapter 14 or Appendix B-32).

Crohn’s disease (see Chapter 8) may be accompanied by skin rash and joint pain. This enteric condition is well known for its arthritic component, which is present in up to 25% of all cases. The client may have had Crohn’s disease for years and may not recognize the onset of these new symptoms as part of that condition. Skin rash may precede joint pain by days or weeks. The hips, thighs, and legs are affected most often; the rash may be raised or flat, purple or red. Knowing the history and association between skin lesions and joint pain can help the therapist direct screening questions and make a reasonable decision about referral.

Screening for Spondylogenic Causes of Sacral/Sacroiliac Pain

Metabolic bone disease (MBD) such as osteoporosis, Paget’s disease, and osteodystrophy can result in loss of bone mineral density and deformity or fracture of the sacrum. The therapist should review cases of sacral pain for the presence of risk factors for any of these metabolic bone diseases (see the discussion on metabolic bone disease in Chapter 11). Neoplasm and fracture are two other possible bony causes of sacral pain. Neoplasm is discussed separately in this chapter.

Metabolic Bone Disease

Mild-to-moderate MBD may occur with no visible signs. Advanced cases of MBD include constipation, anorexia, fractured bones, and deformity.

Osteoporosis: Osteoporosis can cause insufficiency fractures of the sacrum. The therapist must assess for risk factors (see Boxes 15-2 and 11-3) in anyone with sacral pain, especially those in whom pain has an unknown cause, postmenopausal women, older men (over 65), and anyone with a known history of osteoporosis or Paget’s disease. See further discussion on osteoporosis in Chapter 11 and discussion on fractures at the end of this section.

Paget’s Disease: Paget’s disease as a cause of lumbar, sacral, SI, or pelvic pain occurs most commonly in men over 70 years of age (although it can occur earlier and in women). It is the second most common metabolic bone disease after osteoporosis.

Characterized by slowly progressive enlargement and deformity of multiple bones, it is associated with unexplained acceleration of bone deposition and resorption. The bones become weak, spongy, and deformed. Redness and warmth may be noted over involved areas, and the most common symptom is bone pain (see further discussion on Paget’s disease in Chapter 11 and an excellent online article as referenced here).19

Fracture

Three types of fractures affect the sacrum: Traumatic, insufficiency, and pathologic. Trauma resulting in fracture occurs most often with lateral compression injuries seen in motor vehicle accidents or vertical shear injuries resulting from a fall from height onto the lower limbs. Less commonly, direct stress to the sacrum from a fall landing on the buttocks or athletic injury can cause traumatic sacral fracture.20,21 Other risk factors for sacral fracture are listed in Box 15-2.

Trauma-related fatigue or stress fracture of the sacrum occurs most often in young active persons and older adults with osteoporosis. Fatigue or stress fractures can develop as a result of submaximal repetitive forces over time such as occur with overuse or overtraining in military personnel and athletes (e.g., runners, volleyball and field hockey players). Less often, pregnant or postpartum women experience sacral stress fractures, especially if they are participating in athletic training activities or running.22-24

Insufficiency fractures of the sacrum result from a normal stress acting on bone with deficient elastic resistance. Reduced bone integrity is most often associated with postmenopausal or corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis and radiation therapy.20 Insufficiency fractures occur insidiously or as a result of minor trauma, possibly even from weight bearing transmitted through the spine.25

Pathologic fracture describes fractures that occur as a result of bone weakened by neoplasm or other disease conditions (e.g., osteomyelitis, giant cell tumor, chordoma, Ewing sarcoma, multiple myeloma). Insufficiency fractures are actually a subset of pathologic fractures confined to bones with structural alterations due to MBD.20

Clinical manifestations of sacral fractures can present with a wide range of signs and symptoms, many of which are present inconsistently and are considered nonspecific.26 Bilateral or multiple stress fractures of the sacrum or pelvis have been reported.27

The client may report or demonstrate localized pain, tenderness with palpation, antalgic gait, and leg length discrepancy. With all sacral fractures, hip, low back, sacral, groin, or buttock pain may occur, especially with multiple stress fractures of the pelvic and sacral bones. Symptoms may mimic other conditions such as disk disease, recurrence of a local tumor, or metastatic disease.20

Diagnostic imaging may be needed to make the final medical diagnosis. Radiographic studies (x-rays) are often negative in the early phases of stress reactions or fractures. More advanced diagnostic bone imaging may show changes when the client becomes symptomatic.

New onset of sacral or buttock pain 1 to 2 weeks after multilevel lumbosacral fusion with instrumentation should be evaluated for sacral insufficiency fractures, especially if the patient has a recent history of osteoporosis, prolonged sitting, and kyphosis.28-30

Screening for Gynecologic Causes of Sacral Pain

See later discussion on gynecologic causes of pelvic pain in this chapter.

Screening for Gastrointestinal Causes of Sacral/Sacroiliac Pain

The primary pain pattern for gastrointestinal (GI) disease involves the midabdominal region around the umbilicus. It is not likely that the therapist will see clients with this chief complaint; they are more likely to see a doctor or go to the emergency department.

However, the therapist may be evaluating or treating a client for an orthopedic or neurologic problem who reports GI symptoms. When a client relates symptoms associated with the viscera or abdomen, the therapist must think in terms of screening questions to discern whether these symptoms require immediate medical assessment and intervention.

The therapist is more likely to see clients with referred low back or sacral pain from the small or large intestine as it presents in the low back or sacral area (see Figs. 8-15 and 8-16). Although these illustrations depict the pain in small, very round areas, actual pain patterns can vary quite a bit. The location will be approximately the same, but individual variation does occur.

The therapist must ask about the presence of abdominal pain or GI symptoms, occurring either simultaneously or alternating but at the same anatomic level as back or sacral pain. See Case Example 14-13 to review the importance of looking for this particular red flag.

Sacral pain from a GI source may be reduced or relieved after the person passes gas or completes a bowel movement. It may be appropriate to ask a client the following:

Screening for Tumors as a Cause of Sacral/Sacroiliac Pain

Primary sacral tumors include benign and malignant growths. Benign neoplasms include osteochondroma, giant cell tumor, and osteoid osteoma. The more common primary malignant lesions directly affecting the sacrum include chordoma, chondrosarcoma, osteosarcoma, and myeloma.

MBD to the sacrum from primary breast, lung, colon, and prostate is far more common. Sacral insufficiency fractures after pelvic radiation for rectal, prostate, or reproductive cancers can occur, although these are rare.8,31

Although rare, sacral neoplasms usually are not diagnosed early in the disease course because of mild symptoms resembling low back, buttock, or leg pain (sciatica).32,33 Sacral tumors are not easy to see on x-rays and are easily overlooked due to the curvature of the sacrum, location deep within the pelvis, and frequent presence of overlying bowel gas. It is not uncommon for diagnostic delays as the person is treated for a presumed lumbar pathology before the sacrum is finally identified as the source of pathology.33 Referral to a physical therapist before a correct medical diagnosis is made is not unusual.

Giant cell tumor is a highly aggressive local tumor of the bone. The sacrum is the third most common site of involvement. Clients present with localized pain in the lower back and sacrum that may radiate to one or both legs. Swelling may be noted in the involved area. When asked about the presence of other symptoms anywhere in the body, the client may report abdominal complaints and neurologic signs and symptoms (e.g., bowel and bladder or sexual dysfunction, numbness and weakness of the lower extremity).4,34,35

Colorectal or anorectal cancer as a cause of sacral pain is possible as the result of local invasion. Severe sacral pain in the presence of a previous history of uterine, abdominal, prostate, rectal, or anal cancer requires immediate medical referral.

Prostatic (males) or reproductive cancers in men and women can result in sacral pain. See further discussions on testicular cancer in Chapters 10 and 14, prostate cancer in Chapter 10, and gynecologic conditions in this chapter.

The Coccyx

The coccyx or tailbone is a small triangular bone that articulates with the bottom of the sacrum at the sacrococcygeal joint. Injury or trauma to this area can cause coccygeal pain called coccygodynia.

Coccygodynia

Most cases of coccygodynia or coccydynia (pain in the region of the coccyx) seen by the physical therapist occur as a result of trauma, such as a fall directly on the tailbone, or events associated with childbirth.

Symptoms include localized pain in the tailbone that is usually aggravated by direct pressure such as that caused by sitting, passing gas, or having a bowel movement. Moving from sitting to standing may also reproduce or aggravate painful symptoms.

In the case of persistent coccygodynia with a history of trauma, the therapist must keep in mind the possibility of rectal or bladder lesions (Box 15-3). When asked about the presence of other symptoms, clients with coccygodynia after a traumatic fall may also report bladder, bowel, or sexual symptoms. The therapist must ask whether bladder, bowel, or rectal symptoms were present before the fall. Because 50% of all clients with back or sacral pain from a malignancy have preceding trauma or injury, the apparent trauma (especially if the client reports associated symptoms that were present before the trauma) may be something more serious.

For possible clues to treating a client with coccygodynia, the therapist should review Box 15-3, keeping in mind the risk factors for each of these conditions. The therapist should also conduct a neurologic screening examination to identify any signs or symptoms of disk disease. Past history of any of the problems listed is a yellow (warning) flag. Blood in the toilet after a bowel movement may be a sign of anal fissures, hemorrhoids, or colorectal cancer and requires medical evaluation.

The Pelvis

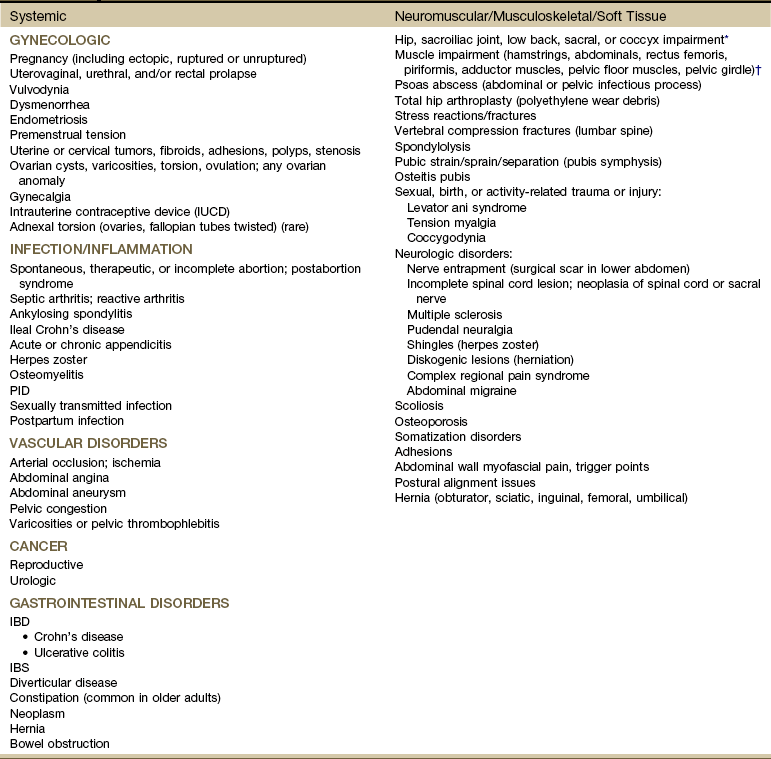

Once again, the principles used in screening for systemic, medical, or viscerogenic causes of back, sacral, and SI pain also apply to pelvic pain. The history and associated signs and symptoms may vary somewhat according to the cause, but many of the causes are the same (e.g., cancer, GI, vascular, urogenital) (Table 15-2).

TABLE 15-2

IUCD, Intrauterine contraceptive device; PID, pelvic inflammatory disease; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease, IBS, irritable bowel syndrome.

*The combined medical and physical therapy differential diagnosis includes many origins of pathokinesiologic conditions, including joint laxity; subluxations or displacements; thoracolumbar hypermobility; bursitis; osteoarthritis; spondyloarthropathy; fracture; and postural, ligamentous, or osteoporosis/osteomalacia. (This list is not exhaustive.)

†As with joint impairment, the differential diagnosis of muscle pathokinesiologic conditions can include many origins (e.g., trigger points, tendinous avulsion, strain/sprain/tear, weakness, loss of flexibility, pelvic floor overactivity [pain and spasm] or underactivity [laxity, weakness, and leaking], diastasis recti).

The most common primary causes of pelvic pain are musculoskeletal, neuromuscular, gynecologic, infectious, vascular, cancer, and GI (in descending order). For example, chronic pelvic pain is most commonly associated with endometriosis, adhesions, IBS, and interstitial cystitis. Infectious disease is the most common systemic cause of pelvic pain.36,37

The goal in screening is to identify individuals with infectious, vascular, or neoplastic causes of pelvic pain and refer those people appropriately while at the same time making sure that those individuals we treat have a problem within the scope of our practice. Therapists must keep in mind that pelvic pain and symptoms can be referred to the pelvis from the hip, sacrum, SI area, or lumbar spine. At the same time, pelvic diseases can refer pain or symptoms to the abdomen, low back, buttocks, groin, and thigh. This means that anytime a client presents with pain or impairment in any of these areas, pelvic disease must be considered as a possible cause. At the same time, keep in mind that pelvic floor muscle spasm can be associated with disorders such as IBS or adhesions secondary to interstitial cystitis; such problems can be aided by the therapist who is skilled in management of pelvic floor muscle impairments.

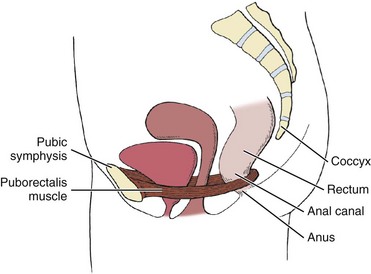

The anterior pelvic wall is part of the musculature of the abdominal cavity. The lateral walls are covered by the iliopsoas and obturator muscles, and inferiorly, the outlet is guarded by the levator ani and pubococcygeus (pelvic floor) muscles, with which the corresponding muscles of the opposite side form the pelvic diaphragm.

These two anatomic regions are separated only by walls of muscle. Because the pelvic cavity is in direct communication with the abdominal cavity (see Fig. 14-1), any organ disease or systemic condition of the pelvic or abdominal cavity can cause primary pelvic pain or referred musculoskeletal pain, as is described in this section.

The therapist should keep in mind that pelvic pain, pelvic girdle pain, and low back pain often occur together or alternately. Whenever discussing pelvic pain, the therapist should ask about the presence of unreported low back pain (including pelvic girdle pain). Pelvic girdle pain can occur separately or combined with low back pain and is defined as generally present between the posterior iliac crest (posterior superior iliac spine [PSIS]) and the gluteal fold in the vicinity of the SI joint.

Using the Screening Model to Evaluate the Pelvis

When our screening model is followed, the same steps are always taken. A personal or family history is obtained, and risk factor assessment is performed. Once the history has been established, the pelvic pain pattern is reviewed. The therapist looks for red flags that may suggest systemic, medical, or viscerogenic causes. Additional questions may be needed to complete the screening process. These questions are presented for all causes of pelvic pain at the end of this chapter.

History Associated With Pelvic Pain

With so many possible causes of pelvic pain, many different factors in the past medical history can raise a red flag. Pelvic pain is a very complex problem. Many medical texts are written about just this one anatomic area.

This text does not attempt to explain or discuss all the possible causes of pelvic floor or pelvic girdle pain. Rather, the intent is for the reader to learn how to screen for the possibility of systemic or viscerogenic sources of pelvic pain or symptoms. With a good understanding of what is important in the history and a list of possible follow-up questions, the therapist assesses each client, keeping in mind that medical referral may be needed.

Some of the more common red flag histories associated with pelvic pain are listed in Box 15-4. With the use of categories from the screening model, risk factors, clinical presentation, and associated signs and symptoms also are listed.

Most conditions that affect the pelvic structures are found in women, but men may also experience pelvic floor impairment and pain. Sexual assault, anal intercourse, prostate or colon cancer, and sexually transmitted disease (STD) are the most common causes for men. Prostate problems such as benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) or prostatitis can cause lower abdominal, back, thigh, or pelvic pain. These conditions are discussed in Chapter 10.

Clinical Presentation

In the screening process, clinical presentation and especially pain patterns are very important. Mechanisms of viscerogenic pain (i.e., how these patterns develop) are discussed in Chapter 3.

Pelvic pain may be visceral pain, caused by stimulation of autonomic nerves (T11 to S3); somatic pain, caused by stimulation of sensory nerve endings in the pudendal nerves (S2, S3); or peritoneal pain, caused by pressure from inflammation, infection, or obstruction of the lining of the pelvic cavity.

Peritoneal pain may be caused by disruption of the autonomic nerve supply of the visceral pelvic peritoneum, which covers the upper third of the bladder, the body of the uterus, and the upper-third of the rectum and the rectosigmoid junction. It is not sensitive to touch but responds with pain on traction, distention, spasm, or ischemia of the viscus.

Peritoneal pain may also occur in relation to the parietal pelvic peritoneum, which covers the upper half of the lateral wall of the pelvis and the upper two thirds of the sacral hollow—all supplied by somatic nerves. These somatic nerves also supply corresponding segmental areas of skin and muscles of the trunk and the anterior abdominal wall. Painful stimulation of the parietal pelvic peritoneum may cause referred segmental pain and spasm of the iliopsoas muscle and muscles of the anterior abdominal wall.

Knowing the characteristics of pain patterns typical of each system is essential. When the client describes these patterns, it is possible for the therapist to recognize them for what they are and to see how the clinical presentation differs from neuromuscular or musculoskeletal impairment and dysfunction.

Pelvic disease may cause primary pelvic pain and may also refer pain to the low back, thigh, groin, and rectum. Usually, pelvic disease appears as acute illness with sudden onset of severe pain accompanied by nausea and vomiting, fever, and abdominal pain. Mild-to-moderate back or pelvic pain that gets worse as the day progresses may be associated with gynecologic disorders. The therapist is more likely to see the atypical presentation of systemically related central lumbar and sacral pain, which is easily mistaken for mechanical pain.

Associated Signs and Symptoms

While collecting pertinent personal and family history, conducting a risk factor assessment, and evaluating the client’s pain pattern, the therapist listens and looks for any yellow or red flags. From there, the therapist formulates any additional questions that may be appropriate on the basis of data collected so far. Before leaving the screening task, the therapist asks a few final questions. The first is about the presence of any associated signs and symptoms.

For example, perhaps the client has pelvic pain and unreported shoulder pain. She may not think her previously unreported shoulder pain has any connection with the current pelvic pain, or she may not see that the presence of a vaginal discharge is linked in any way to her low back and pelvic pain. Discharge from the vagina or penis (yellow or green, with or without an odor) in the presence of low back, pelvic, or sacral pain may be a red flag.

To bring this information out and make any of these connections, the therapist must ask about the presence of any associated signs and symptoms. Ask the client the following:

If the client says “No,” then ask about the presence of urologic symptoms and constitutional symptoms, and look for a connection between the menstrual cycle and symptoms. If it appears that there may be a gynecologic basis for the client’s symptoms, the therapist may want to ask some additional questions about missed menses, shoulder pain, and spotting or bleeding.

The therapist should assess for the presence of dysmenorrhea, defined as painful cramping during menstruation. Dysmenorrhea may be primary (of unknown cause) or secondary as a result of a pelvic pathologic condition related to endometriosis, intrauterine tumors or polyps (myomas), uterine prolapse, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), cervical stenosis, and adenomyosis (benign invasive growths of the endometrium into the muscular layers of the uterus).

Dysmenorrhea is characterized by spasmodic, cramp-like pain that comes and goes in waves and radiates over the lower abdomen and pelvis, thighs, and low back, sometimes accompanied by headache, irritability, mental depression, fatigue, and GI symptoms.

Screening for Neuromuscular and Musculoskeletal Causes of Pelvic and Pelvic Floor and Pelvic Girdle Pain

The therapist is most likely to see pelvic floor pain and/or pelvic girdle pain that are caused by neuromuscular or musculoskeletal problems. Pelvic pain or symptoms may be referred from systemic or neuromusculoskeletal origins from the hip, SI joint, sacrum, or low back.

Pelvic floor pain can present suprapubically, perineally, and/or in the low buttock/anal areas. Pelvic girdle pain can occur separately or combined with low back pain and is defined as generally present between the posterior iliac crest (PSIS) and the gluteal fold in the vicinity of the SI joint. Pain may radiate to the posterior thigh; endurance for standing, walking, and sitting is decreased.38 Pelvic girdle pain occurs most often during pregnancy or continues many years postpartum. Many women have both pelvic floor and pelvic girdle pain, requiring each to be addressed externally and internally.

Likewise, pelvic diseases can refer pain and symptoms to the low back, groin, and thigh. When evaluating low back or pelvic pain, the therapist must assess for pelvic floor laxity or tension, psoas abscess, trigger points, history of birth or sexual trauma, and the presence of any associated signs and symptoms.

Neurologic disorders (e.g., nerve entrapment, incomplete spinal cord lesion, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s, stroke, pudendal neuralgia) can cause pelvic pain and dysfunction. Pudendal nerve entrapment is characterized by pain relief when one is sitting on a toilet seat or standing; elimination of symptoms after a pudendal nerve block is diagnostic.

Pregnancy-related and postpartum low back pain, pelvic floor pain, and pelvic girdle pain are also common and have an impact on daily life for many women. Prevention and treatment of symptoms is an important issue for therapists who work in the area of women’s health.39,40

Musculoskeletal impairment of the pelvic floor and low back may manifest as dyspareunia (pain before, during, or after intercourse). Overactivity (pain and spasm; muscles contract when they should relax or do not relax completely)41 of the pelvic floor and pelvic floor trigger points can contribute to entrance (superficial or deep) dyspareunia. Deep thrust dyspareunia may also be related to SI or low back impairment. Dyspareunia symptoms that are reduced in alternate positions may indicate a musculoskeletal component, especially when other signs and symptoms characteristic of musculoskeletal impairment are also present.42,43

One of the most common musculoskeletal sources of pelvic floor pain in men and women is the trigger point. Muscles most likely to cause or refer pain to the pelvic area include the levator ani, abdominals, quadratus lumborum, and iliopsoas.44-46

Typical aggravating and relieving factors for pain from a neuromuscular or musculoskeletal source include the following:

• Aggravated by exercise, weight bearing

• Aggravated by trunk/lumbar rotation

• Relieved by rest or stretching

• Pain or altered movement pattern produced by trunk and lumbar rotation

The therapist looks for a contributing history such as a fall on the buttocks, pregnancy, or trauma. Avulsion of hamstrings from a sports injury may be reported. Trauma from physical or sexual assault may remain unreported. Screening for assault is an important part of many evaluations (see Chapter 2).

The therapist also looks for muscle impairment. For therapists trained in pelvic floor muscle examination, external and internal palpation of the pelvic floor musculature is helpful.47,48 Examination also includes observation for varicosities and assessment of muscle tone (muscle overactivity [pain and spasm] or underactivity [laxity with weakness and leaking] and the presence of trigger points.44,49,50 Transabdominal ultrasound and vaginal dynamometer are two tools used by some physical therapists to assess pelvic floor muscle contraction. Many clients who experience low back, pelvic, SI, sacral, or groin pain have unrecognized pelvic floor impairment.51

Pain provocation tests for the symphysis pubis and SI joint (e.g., Patrick’s/Faber’s, modified Trendelenburg, Gaenslen’s, shear, P4, gapping, and compression tests), palpation, and mobility testing help point to pelvic girdle impairment, but this could be associated with primary pelvic floor impairment so that both problems coexist.52

The treatment strategy may be to address the pelvic girdle pain first; if it does not resolve, then a pelvic floor muscle examination may be needed to confirm pelvic floor impairment. P4 is a pelvic floor muscle examination that refers to the “provocation of posterior pelvic pain” screening test for pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain.52 Reliability and validity of the provocation tests mentioned here have been evaluated and reported; for details see Vleeming38 and Olsen.52 Imaging tests, such as x-rays, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), help rule out problems such as fractures, ankylosing spondylitis, and reactive arthritis.38

Fig. 15-2 gives a simple representation of how the puborectalis muscle acts as a sling around various structures of the pelvis. The condition and position of the pelvic sling are very important in the maintenance of normal pelvic floor health.

Fig. 15-2 Pelvic sling. Puborectalis muscle forms a U-shaped sling encircling the posterior aspect of the rectum and returns along the opposite side of the levator hiatus to the posterior surface of the pubis. This shows how the condition and position of the pelvic sling contribute to the function of the pelvic floor and the encircled viscera. Obesity, multiparity, and prolonged pushing during labor and delivery are just a few of life’s events that can disrupt the integrity of the pelvic sling and the pelvic floor. (From Myers RS: Saunders manual of physical therapy practice, Philadelphia, 1995, WB Saunders.)

Fig. 14-1 provides a visual reminder that the muscles of the pelvic floor support the reproductive organs and the viscera in the peritoneum. Any impairment of these organs may cause impairment of the pelvic floor and vice versa. Any weakness or impairment of the pelvic floor can lead to problems with the viscera located in the abdominal or pelvic cavities.

Anterior Pelvic Pain

Anterior pelvic pain occurs most often as a result of any disorder that affects the hip joint, including inflammatory arthritis; upper lumbar vertebrae disk disease (rare at these segments); pregnancy with separation of the symphysis pubis; local injury to the insertion of the rectus abdominis, rectus femoris, or adductor muscle; femoral neuralgia; and psoas abscess.

Stress reactions of the pubis or ilium, sometimes called stress fractures (disruption of the bone at the tendon-bone interface without displacement from repetitive contraction), can occur during traumatic labor and delivery, but they are more common in osteomalacia and Paget’s disease and produce anterior pelvic pain. Traumatic stress reactions may also occur in joggers, military personnel, and athletes.

Although the underlying pathology differs, symptoms are similar to separation of the symphysis pubis and pelvic ring disruption and may include pain in the involved areas that is aggravated by active motion of the limb or deep pressure and weight bearing during ambulation. Symptoms from pelvic instability as a result of pelvic ring injury or disruption (whether from birth trauma in women of childbearing age or pelvic stress fracture in an older adult with osteoporosis) may be aggravated by single-leg-stance.53,54

Femoral hernia, which accounts for 20% of hernias in women, may cause lateral wall pelvic pain when the hernia strangulates. The referred pain pattern is located down the medial side of the thigh to the knee; inguinal hernias are likely to cause groin pain. Immediate surgical repair is indicated.

Posterior Pelvic Pain

Posterior pelvic pain originating in the lumbosacral, sacroiliac, coccygeal, and sacrococcygeal regions usually appears as localized pain in the lower lumbar spine, pelvic girdle, and over the sacrum, often radiating over the sacroiliac ligaments. Pain radiating from the SI joint can commonly be felt in both the buttock and the posterior thigh and is often aggravated by rotation of the lumbar spine on the pelvis. A proximal hamstring injury, including avulsion of the ischial epiphysis in the adolescent, may also cause posterior pelvic and buttock pain.

Coccygodynia and sacrococcygeal pain are common presentations in women and are often associated with a fall on the buttocks or traumatic childbirth. They manifest with the person having difficulty sitting on firm surfaces and having pain in the coccygeal region on defecation or straining.

Levator ani syndrome and tension myalgia may produce symptoms of pain, pressure, and discomfort in the rectum, vagina, perirectal area, or low back and can mimic a diskogenic problem. Overactivity (pain and spasm) and tenderness in the levator ani may occur in men and women and may be caused by chronic prostatitis that does not resolve with antibiotics (men), birthing trauma (women), neurologic abnormalities in the lumbosacral spine, sexual assault or trauma, or anal fissures from anal intercourse. Pain or rectal pressure may occur during sexual intercourse, as may throbbing pain during bowel movement with accompanying constipation and impaired bowel and bladder function.

Screening for Gynecologic Causes of Pelvic Pain

Pregnancy, multiparity, and prolonged labor and delivery (especially combined with obesity) are risk factors for gynecologic conditions that can alter the normal position of the bladder, uterus, and rectum in relation to one another (Fig. 15-3), resulting in pelvic organ prolapse such as rectocele, cystocele, and prolapsed uterus with concomitant pelvic floor pain and impairment.

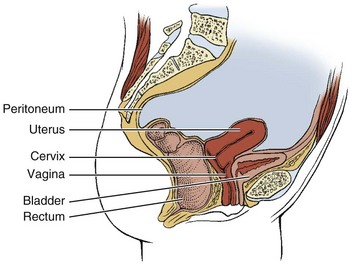

Fig. 15-3 Normal female reproductive anatomy (sagittal view). Locate the rectum, uterus, bladder, vagina, and cervix in this illustration. Note the size, shape, and orientation of each of these structures. The rectum turns away from the viewer in this sagittal section, giving it the appearance of ending with no connection to the intestines. Understanding the normal orientation of these structures will help when each of the diseases that can cause low back pain is considered.

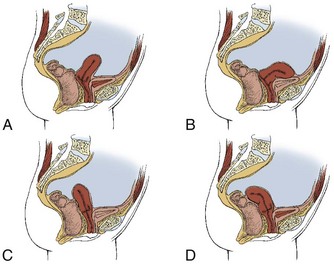

Gynecologic causes of pelvic floor pain are most often produced by congenital anomaly, inflammatory processes (including infection), neoplasia, or trauma. In addition, pelvic girdle pain may be associated with pregnancy, endometriosis, and altered uterine position (Fig. 15-4). Variations in the angle and position of the uterus occur from woman to woman. Many women are unaware of their uterine position. Only if the physician tells her, “You have a tipped uterus,” or “You have a retroverted uterus,” will she know whether any change from the normal position of the uterus has occurred. Other women experience extreme pain associated with the menstrual cycle, which may be linked with uterine position.

Fig. 15-4 Abnormal positions of the uterus. Variations in the angle and position of the uterus occur from woman to woman. Each illustration depicts a slightly different anatomic position of the uterus. A, Midline position. Usually, the uterus is above and parallel to the bladder. In the midline position, the uterus is more vertical. B, Anteflexed uterus. The uterus is in its proper position above the bladder, but the upper one-third to one-half of the body is flexed forward. C, Retroverted uterus. About 20% of American women have a tilted, or retroverted, uterus. The top of the uterus naturally slants toward the spine rather than toward the umbilicus. D, Retroflexed uterus. An extremely tilted uterus called retroflexion may even bend down toward the tailbone. A woman with a retroflexed uterus may be unable to use a tampon or a diaphragm. Back pain is more likely to occur with pregnancy and labor for the woman with a retroverted or retroflexed uterus.

Children younger than 14 years rarely experience pelvic pain of gynecologic origin. Infection is the most likely cause and is limited to the vulva and vagina. Theoretically, infection can ascend to involve the peritoneal cavity, causing iliopsoas abscess and pelvic, hip, or groin pain, but this rarely happens in this age group.

Pregnancy

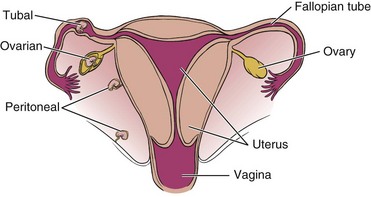

Pelvic pain associated with normal pregnancy is similar to low back pain, as was discussed earlier in Chapter 14. About 1% of all pregnancies take place outside the endometrium (or ectopic), with most ectopic implantations occurring in the fallopian tube (Fig. 15-5). Risk factors include tubal ligation; STD; pelvic inflammatory disease; infertility or infertility treatment; previous tubal, pelvic, or abdominal surgery; or the use of intrauterine contraceptive devices (IUCDs) such as rings, loops, coils, or Ts (see Fig. 14-6).

Fig. 15-5 Ectopic pregnancy. An ectopic pregnancy can occur when the egg is fertilized and implanted outside the uterus. The ovum can be embedded inside the ovary (ovarian pregnancy), inside the fallopian tube (tubal pregnancy), or anywhere between the ovary and the uterus, including along the outside lining of the uterus (extrauterine) or inside the abdominal cavity along the peritoneum as shown. Rupture of the ovum and hemorrhage is the usual result. If this occurs early in the menstrual cycle, the woman may experience heavier bleeding than usual but remain unaware of the failed pregnancy.

Symptoms of ectopic pregnancy most often include unexplained vaginal spotting, bursts of bleeding, and sudden lower abdominal and pelvic cramping shortly after the first missed menstrual period. At first, the pain may be a vague “twinge” or soreness on the affected side; later it can be sharp and severe.

Gradual hemorrhage causes pelvic (and sometimes low back or shoulder) pain and pressure, but rapid hemorrhage results in hypotension or shock. Tubal rupture is common and requires medical attention and diagnosis.

Prolapsed Conditions

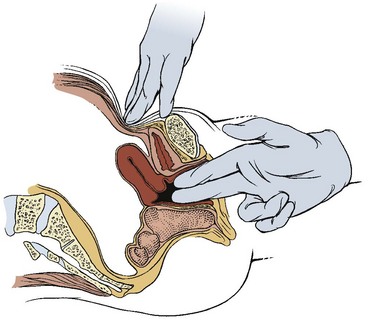

Prolapse is the collapse, falling down, or downward displacement of structures such as the uterus, bladder, or rectum. A pelvic examination is performed by a physician or other trained professional, such as a physical therapist, to identify prolapse (Fig. 15-6).

Fig. 15-6 Pelvic examination. With the woman in the lithotomy position (supine with hips and knees flexed and feet in stirrups), the examiner inserts one or two gloved fingers into the vaginal canal up to the point of the cervix or soft tissue obstruction. The examiner applies firm pressure in the lower abdomen above the bladder while the woman bears down slightly as if performing a Valsalva maneuver. The examiner evaluates the tone of the pelvic floor and the position of the uterus during this test. Integrity of the pelvic floor (e.g., muscle tone, laxity, trigger points) can also be tested.

Uterovaginal prolapse can cause low-grade and persistent pelvic pain. Prolapse may result from a combination of basic anatomic structure, effects of pregnancy and labor, postmenopausal hormone deficiency, and poor general muscular fitness. Pelvic floor tension myalgia and prolapse often occur together. Obesity combined with chronic cough, constipation, and multiparity is a common contributing factor to pelvic floor problems.

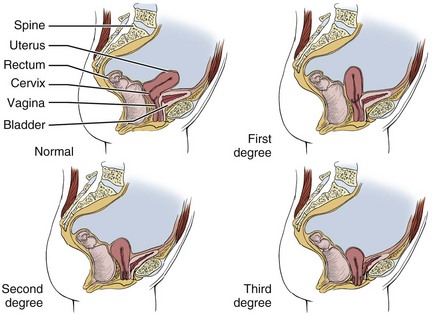

Uterine Prolapse: Uterine prolapse occurs most often after childbirth and is graded as first-, second-, or third-degree prolapse (Fig. 15-7). Secondary prolapse may occur with prolonged pushing during labor and delivery, large intrapelvic tumors, or sacral nerve disorders, or it may follow pelvic or abdominal surgery.

Fig. 15-7 Uterine prolapse. First-degree prolapse: The uterus has dropped up to one-third of the way into the vaginal canal. Second-degree prolapse: The uterus has descended fully into the vaginal canal, right down to the vaginal opening. Third-degree prolapse: the uterus is displaced downward even further and bulges outside the vaginal opening.

The pain of prolapse is central, suprapubic, and dragging in the groin, and a sensation of a lump at the vaginal opening is noted. Pain is primarily due to stretching of the ligamentous supports (uterosacral ligament attaches to the sacrum; loss of ligamentous integrity contributes to significant biomechanical changes) and secondarily to excoriation (scratch or abrasion) of the prolapsed cervical or vaginal tissue, which may occur.

Third-degree prolapse is often accompanied by low back pain with or without pelvic, sacral, or abdominal cramping or heaviness. Symptoms are relieved by rest and lying down and are often aggravated by prolonged standing, walking, coughing, sexual intercourse, or straining. Urinary incontinence is commonly associated with uterine prolapse.

Sexual intercourse is possible because the soft tissues of the uterus and vagina can be pushed or pressed out of the way. However, excoriation (scratching or abrasion) of the tissue may occur, accompanied by bleeding and local pain. Care must be taken when anything is inserted into the vagina. Excessive, repetitive force should be avoided.

Some women use a removable device called a pessary for a prolapsed uterus, bladder, or rectum. It is placed in the vagina to support the prolapsed structure. These devices are usually considered temporary and should be used in conjunction with a program to rehabilitate the pelvic floor impairment. Long-term use of such devices may be required when surgical repair is not possible or the woman is not a good surgical candidate.

Identifying the presence of uterine prolapse does not necessarily require medical referral. Conservative care such as a program of pelvic floor recovery and management of sexual intercourse can be very helpful for the woman and may be the first step in treatment. Client education about positions in which gravity is used to assist the uterus in resuming its normal position can be very helpful. For example, supine with a pillow or wedge support under the pelvis is a helpful rest position and can be used while the patient is doing pelvic floor exercises. It is also a more comfortable position for sexual intercourse for some women.

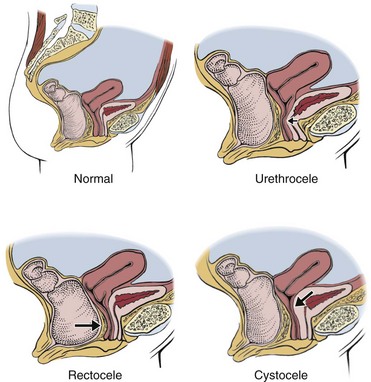

Cystocele and Rectocele: Cystocele is the protrusion or herniation of the urinary bladder against the wall of the vagina. Rectocele is a protrusion or herniation of the rectum and posterior wall of the vagina into the vagina (Fig. 15-8).

Fig. 15-8 Pelvic organ prolapse. A, Normal alignment of uterus, bladder, and rectum. B, Urethrocele. Urethra pressing against the vaginal canal. C, Rectocele. The uterus and bladder are in their proper anatomic place, but the rectum has prolapsed and is compressing against the vaginal canal. Many women have more than one of these conditions at the same time as a result of pregnancy and childbirth. D, Cystocele. The arrow shows displacement of the bladder against the vaginal canal.

Similar to the prolapsed uterus, these two pelvic floor disorders occur most often after pregnancy and childbirth but may also be associated with surgery and obesity (especially obesity combined with multiple pregnancies and births). These conditions are the result of pelvic floor relaxation or structural overstretching of the pelvic musculature or ligamentous structures. Patient history may include prolonged labor, bearing down before full dilation, forceful delivery of the placenta, instrument delivery (e.g., forceps, vacuum suction), chronic cough, or lifting of heavy objects.

Trauma to the pudendal or sacral nerves during birth and delivery is an additional risk factor. Decreased muscle tone due to aging, complications of pelvic surgery, or excessive straining during bowel movements may also result in prolapse. Pelvic tumors and neurologic conditions, such as spina bifida and diabetic neuropathy, which interrupt the innervation of pelvic muscles, can also increase the risk of prolapse.

Endometriosis

Endometriosis (see Chapter 14) is a pathologic condition of retrograde menstruation. Tissue resembling the mucous membrane lining the uterus occurs outside the normal location in the uterus but within the pelvic cavity, including the ovaries, pelvic peritoneum, bowel, and diaphragm. It occurs most often during the reproductive years and in up to 50% of women with infertility.55-57 Severity of pain is related more to the site than to the extent of disease.

Pelvic pain associated with endometriosis can be referred to the low back, rectum, and lower sacral or coccygeal region, starting before or after the onset of menstruation and improving after cessation of menstrual flow, with cyclic recurrence (a key finding). As the condition progresses, pain continues throughout the cycle, with exacerbation at menstruation and, finally, constant severity.

Other symptoms may include rectal discomfort during bowel movements, diarrhea, constipation, recurrent miscarriage, and infertility. Box 15-5 has more information on this condition.

Gynecalgia

Although a pathologic cause can be identified for most cases of chronic pelvic pain, a small percentage remains for which no physical cause can be determined, and the term gynecalgia is used. Women with gynecalgia syndrome are usually 25 to 40 years of age and have at least one child. The symptoms are of at least 2 years’ duration (and often many more), with acute exacerbation from time to time.

Pain associated with gynecalgia is vague and poorly localized, although it is usually confined to the lower abdomen and pelvis, radiating to the groin and upper and inner thighs. Other symptoms include dyspareunia, menstrual changes, low back pain, urinary and bowel changes, fatigue, and obvious anxiety and depression.

Screening for Infectious Causes of Pelvic Girdle Pain

Infection is the most common cause of systemically induced pelvic pain. Infection or inflammation within the pelvis from acute appendicitis, diverticulitis, Crohn’s disease, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis of the SI joint, urologic disorders, sexually transmitted infection (STI; e.g., Chlamydia trachomatis), and salpingitis (inflammation of the fallopian tube) can produce visceral and somatic pelvic pain because of the involvement of the parietal peritoneum.

Secondary pelvic infection may follow surgery, septic abortion, pregnancy, or recent birth as a result of the entry of endogenous bacteria into the damaged pelvic tissues. PID and STI are the most common causes of infection in women.

All these disorders have similar signs and symptoms during the acute phase. The client may not have any pain but will report low back or pelvic “discomfort,” or there may be a report of acute, sharp, severe aching on both sides of the pelvis. Accompanying groin discomfort may radiate to the inner aspects of the thigh.

Keep in mind that in the older adult, the first sign of any infection might not be an elevated temperature, but rather, confusion, increased confusion, or some other change in mental status.

Right-sided abdominal or pelvic inflammatory pain is often associated with appendicitis, whereas left-sided pain is more likely associated with diverticulitis, constipation, or obstipation (left sigmoid impaction). Left-sided appendicitis is possible and not that uncommon.58 Bilateral pain may indicate infection. The pain may be aggravated by increased abdominal pressure (e.g., coughing, walking). Knowing these pain patterns helps the therapist quickly decide what questions to ask and which associated signs and symptoms to look for. The therapist should test for iliopsoas or obturator abscesses (see Chapter 8).

Other red flag symptoms may be reported in response to specific questions about disturbances in urination, odorous vaginal discharge, tachycardia, dyspareunia (painful or difficult intercourse), or constitutional symptoms such as fever, general malaise, and nausea and vomiting.

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

PID consists of a variety of conditions (i.e., it is not a single entity), including endometritis, salpingitis, tubo-ovarian abscess, and pelvic peritonitis. Any inflammatory condition that affects the female reproductive organs (uterus, fallopian tubes, ovaries, cervix) may come under the diagnostic label of PID.59

PID is a bacterial infection that occurs whenever the uterus is traumatized; it is often associated with STI/STD and may occur after birth or after an abortion. Infection can be introduced from the skin, vagina, or GI tract. It can be an acute, one-time episode or may be chronic with multiple recurrences.

It is estimated that two-thirds of all cases are caused by STIs such as chlamydia and gonorrhea.60 Chlamydia is a bacterial STI that is acquired through vaginal, oral, or anal intercourse. It is often asymptomatic but can present with vaginal bleeding and discharge and burning during urination. Pelvic pain does not occur until chlamydia leads to PID. When detected and treated early, chlamydia is relatively easy to cure.

A direct relationship has been observed between early age of first sexual intercourse, the number of sexual partners a woman has, recent new partner (within previous 3 months), and a past history of STD (in the client or her partner) or risk of STD (especially human papillomavirus, or HPV, a risk factor for cervical cancer).61-63 PID may occur if chlamydia is not treated; even if it is treated, damage to the pelvic cavity cannot be reversed. The more partners a woman has, the greater is the risk of PID.59

Other risk factors include interruption of the cervical barrier by means of pregnancy termination, insertion of intrauterine device within the past 6 weeks, in vitro fertilization/intrauterine insemination, or any other instrumentation of the uterus.59

PID associated with scarring in the pelvic organs, including the ovaries, fallopian tubes, bowel, and bladder, may cause chronic pain. Women can be left infertile because of damage and scarring to the fallopian tubes. After a single episode of PID, a woman’s risk of ectopic pregnancy increases sevenfold compared with the risk for women who have no history of PID.64,65

STIs such as chlamydia and syphilis are on the rise among America’s sexually active young adult population (ages 18 to 25). In fact, chlamydia was the most commonly reported infectious disease in the United States in 2004. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) annual report, the highest rates of chlamydia occur in sexually active women ages 15 to 19. Syphilis predominates in men who engage in risky sexual behavior (e.g., unprotected vaginal, anal, oral sex) with men or with men and women.65-69

It does not happen often, but there may be times when the therapist must ask about the possibility of an STI. Sexually active women with vague symptoms are the most likely group to be interviewed about STIs/STDs. See specific screening questions in Chapter 14 and Appendix B-32.

Any of the red flags listed in Box 15-4 in the presence of pelvic pain raises the suspicion of a medical problem. Medical referral must be made as quickly as possible. Early medical intervention can prevent the spread of infection and septicemia, and can preserve fertility. Damage to the pelvic floor from any of these conditions can result in pelvic floor impairment that is within the scope of a physical therapist’s practice. See Box 15-5 for resources that can provide more information on this and other conditions.

Screening for Vascular Causes of Pelvic Girdle Pain

Vascular problems that affect the pelvic cavity and pelvic floor musculature have two primary causes. The first is the general condition of peripheral vascular disease (PVD); the second is a specific example of PVD called pelvic congestion syndrome from ovarian and/or vulvar varicosities (abnormal enlargement of veins). Other conditions, such as abdominal angina and abdominal aneurysm, are less common vascular causes of pelvic pain; these conditions are discussed in greater detail in Chapter 6.

Peripheral Vascular Disease

The iliac arteries may become gradually occluded by atherosclerosis or may be obstructed by an embolus. The resultant ischemia produces pain in the affected limb but may also give rise to pelvic pain. Whether the occlusion is thrombotic or embolic, the client may report pain in the pelvis, affected limb, and possibly the buttocks.

The pain is characteristically aggravated by exercise (claudication). Typically, symptoms develop 5 or 10 minutes after the client has started the activity. This lag time is characteristic of a vascular pain pattern associated with atherosclerosis or blood vessel occlusion.

Musculoskeletal causes of pelvic pain are also made worse by activity and exercise, especially weight-bearing exercise, but the timing is not as predictable as with pain from vascular causes. Musculoskeletal conditions may cause pain immediately (e.g., with muscle strain or trigger points) or, more likely, after prolonged activity or exercise. The affected limb becomes colder and paler. In sudden occlusion, diminished sensation to pinprick may be observed on examination. Femoral and distal arteries should be palpated for pulsation.

Thrombosis of the large iliac veins may occur spontaneously after injury to the lower limb and pelvis, or it may appear after pelvic surgical procedures. An estimated 30% of clients have asymptomatic deep vein thrombosis after major surgery. Thrombosis that occludes the iliac vein produces an enlarged, warm, and painful leg; occasionally, discomfort in the pelvis is noted.

Anyone with PVD can demonstrate the same kind of symptoms in the pelvic floor structures. The most likely age group to be affected by vascular disease is adults over 60, especially women who are postmenopausal.

Watch for a history of heart disease with a clinical presentation of pelvic, buttock, and leg pain that is aggravated by activity or exercise (claudication). Look for changes in skin and temperature on the affected side (arterial occlusion or venous thrombosis), especially in the presence of known heart disease or recent pelvic surgery (see Box 4-13; Case Example 15-2).

Pelvic Congestion Syndrome

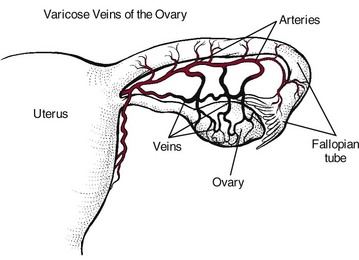

Varicose veins of the ovaries (varicosities) cause the blood in the veins to flow downward rather than up toward the heart. They are a manifestation of PVD and a potential cause of chronic pelvic pain. The condition has been called pelvic congestion syndrome (PCS) or ovarian varicocele.

The specific impairment associated with PCS is an incompetent and dilated ovarian vein with retrograde blood flow (Fig. 15-9). Ovarian venous reflux and stasis produce venous dilatation, congestion, and pelvic pain. Imaging studies have verified the fact that very few venous valves are found in the blood vessels of the pelvic area.70-73

Fig. 15-9 Ovarian varicosities associated with pelvic congestion syndrome are the cause of chronic pelvic pain for women. This form of venous insufficiency is often accompanied by prominent varicose veins elsewhere in the lower quadrant (buttocks, thighs, calves). Men may have similar varicosities of the scrotum (not shown).

Any compromise of the valves (or blood vessels) in the area can lead to this condition. It can also occur as the result of kidney removal or donation because the ovarian vein is cut when the kidney is removed. Varicosity of the gonadal venous plexus can occur in men and is more readily diagnosed by the presentation of observable varicosities of the scrotum.

Many women are unaware that they have this problem and remain asymptomatic. Women of childbearing age are affected most often. Many have had three or four (or more) pregnancies and are 40 years old or older.

Symptoms of ovarian varicosities reflect the vascular incompetence associated with venous insufficiency. These symptoms include pelvic pain that worsens toward the end of the day or after standing for a long time, pain after intercourse, sensation of heaviness in the pelvis, and prominent varicose veins elsewhere on the body, especially the buttocks and thighs.70,73-75

Other associated symptoms may vary and include vaginal discharge, headache, emotional distress, GI distress, constipation, and urinary frequency and urgency. An undetermined number of women also have endometriosis, but the relationship is unknown.77,78 Varicosities may be large enough to compress the ureter, leading to these urologic symptoms. Fatigue (loss of energy) and insomnia are common in women who experience headache with PCS (Case Example 15-3).

Screening for Cancer as a Cause of Pelvic Pain

The female pelvis is a depository for malignant tissue after incomplete removal of a primary carcinoma within the pelvis, for recurrence of cancer after surgical resection or radiotherapy of a pelvic neoplasm, or for metastatic deposits from a primary lesion elsewhere in the abdominal cavity.

Metastatic spread can occur from any primary tumor in the abdominal or pelvic cavity (see Fig. 13-2). For example, colon cancer can metastasize to the pelvic cavity by direct extension through the bowel wall to the musculoskeletal walls of the pelvic cavity or to surrounding organs. This may produce fistulas into the small intestine, bladder, or vagina. Advanced rectal tumors can become “fixed” to the sacral hollow. Deep pain within the pelvis may indicate spread of neoplasm into the sacral nerve plexuses.

Cancer recurrence can also occur after radiotherapy or surgery to the abdominal or pelvic cavity. This happens most often when incomplete removal of the primary carcinoma has occurred.

Using the Screening Model for Cancer

In the case of cancer as a cause of pelvic pain, a past history of cancer is usually present, most commonly, cancer within the pelvic or abdominal cavity (e.g., GI, renal, reproductive). A history of cancer with recent surgical removal of tumor tissue followed by back, hip, sacral, pelvic, or pelvic girdle pain within the next 6 months is a major red flag. Even if it appears to be a clear neuromuscular or musculoskeletal problem, referral is warranted for medical evaluation.

A common clinical presentation of pelvic or abdominal cancer referred to the soma is one of back, sacral, or pelvic pain described as one or more of the following: Deep aching, colicky, constant with crescendo waves of pain that come and go, or diffuse pain. Usually, the client cannot point to it with one finger (i.e., pain does not localize).

The therapist must remember to ask whether the client is having any symptoms of any kind anywhere else in the body. This is vitally important! Signs and symptoms associated with pelvic pain can range from constitutional symptoms to symptoms more common with the GI, genitourinary (GU), or reproductive system.

The therapist must ask about blood in the urine or stools. Once the physical therapy examination has been completed, including the history, risk factor assessment, pain patterns, and any associated signs and symptoms, it is time to step back and conduct a Review of Systems (see Chapters 1 and 4).

The Review of Systems is part of the evaluation described in the Guide’s Elements of Patient/Client Management that leads to optimal outcomes (see Fig. 1-4). It is part of the dynamic process in which the therapist makes clinical judgments on the basis of data gathered during the examination.

In the screening process, the therapist reviews the following:

• Do any red flags in the history or clinical presentation suggest a systemic origin of symptoms?

• Are any red flags associated signs and symptoms?

• What additional screening tests or questions are needed (if any)?

• Is referral to another health care provider needed, or is the therapist clear to proceed with a planned intervention (Case Example 15-4)?

Keep in mind the Clues Suggesting Systemic Pelvic Pain, which are listed at the end of this chapter. If hip or groin pain is an accompanying feature with pelvic pain, review Clues to Screening Lower Quadrant Pain (see Chapter 16); likewise for anyone with pelvic and back pain see Clues to Screening Head, Neck, or Back Pain (see Chapter 14).

The therapist can use the Special Questions to Ask at the end of Chapter 14. It may not be necessary to ask all these questions. The therapist can use the overall clues gathered from the history, risk factor assessment, clinical presentation, and associated signs and symptoms, while reviewing the list of special questions to see whether there is anything appropriate to ask the individual client.

Gynecologic Cancers

Cancers of the female genital tract account for about 12% of all new cancers diagnosed in women. Although gynecologic cancers are the fourth leading cause of death from cancer in women in the United States, most of these cancers are highly curable when detected early. The most common cancers of the female genital tract are uterine endometrial cancer, ovarian cancer, and cervical cancer.79

Endometrial (Uterine) Cancer: Cancer of the uterine endometrium, or lining of the uterus, is the most common gynecologic cancer, usually occurring in postmenopausal women between the ages of 50 and 70 years. Its occurrence is associated with obesity, endometrial hyperplasia, prolonged unopposed estrogen therapy (hormone replacement therapy without progesterone), and more recently, tamoxifen used in the treatment of breast cancer.80,81

Clinical Signs and Symptoms: Seventy-five percent of all cases of endometrial cancer occur in postmenopausal women. The most common symptom is abnormal vaginal bleeding or discharge at presentation. However, 25% of these cancers occur in premenopausal women, and 5% occur in women younger than 40 years.

In a physical therapy practice, the most common presenting complaint is pelvic pain without abnormal vaginal bleeding. Abdominal pain, weight loss, and fatigue may occur but remain unreported. Unexpected or unexplained vaginal bleeding in a woman taking tamoxifen (chemoprevention for breast cancer) is a red flag sign. Tamoxifen as a risk factor for endometrial carcinoma has come under question.82

Ovarian Cancer: Ovarian cancer is the second most common reproductive cancer in women and the leading cause of death from gynecologic malignancies, accounting for more than half of all gynecologic cancer deaths in the Western world.79 It affects women of all races and ethnic groups.

Risk Factors: Risk increases with advancing age, and the incidence of ovarian cancer peaks between the ages of 40 and 70 years. Other factors that may influence the development of ovarian cancer include the following:

• Nulliparity (never being pregnant), giving birth to fewer than two children, giving birth for the first time when over age 35

• Personal or family history of breast, endometrial, or colorectal cancer

• Family history of ovarian cancer (mother, sister, daughter; especially at a young age); carrying the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene

• Early menarche, late menopause, prolonged postmenopausal hormone (estrogen) therapy (long-term, additive exposure to estrogen)

• Obesity (body mass index [BMI] of 30 or more)

• Exposure to cosmetic talc or asbestos (conflicting evidence)83-87

Identification of the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene and subsequent evidence for a family of genes that may play a role in the breast–ovarian syndrome and familial ovarian cancer offer the possibility of identifying women truly at risk for this disease.88,89

No reliable screening test can detect ovarian cancer in its early, most curable stages. Two diagnostic tests are used, but both lack sensitivity and specificity. The CA-125 blood test (carcinoembryonic antigen, a biologic marker) shows elevation in about half of women with early-stage disease and about 80% of those with advanced disease. Transvaginal ultrasonography helps determine whether an existing ovarian growth is benign or cancerous. Because early-stage symptoms are nonspecific, most women do not seek medical attention until the disease is advanced.

The ovaries begin in utero, where the kidneys are located in the fully developed human, and then migrate along the pathways of the ureters. Following the viscerosomatic referral patterns discussed in Chapter 3, ovarian cancer can cause back pain at the level of the kidneys. Murphy’s percussion test (see Chapter 10) would be negative; other symptoms of ovarian cancer might be present but remain unreported if the woman does not recognize their significance.

An ovarian symptom index for advanced ovarian cancer has also been developed.93

Rarely, reproductive carcinomas, including ovarian carcinoma, will present first with a paraneoplastic syndrome such as polyarthritis syndrome, carpal tunnel syndrome, myopathy, plantar fasciitis, or palmar fasciitis (swelling, digital stiffness or contractures, palmar erythema). The condition may be misdiagnosed as chronic regional pain syndrome (formerly reflex sympathetic dystrophy), Dupuytren’s contracture, or a rheumatologic disorder.94,95

Hand and upper extremity manifestations often appear before the tumor is clinically evident. Treatment of the symptoms will have little effect on these conditions. Only successful treatment of the underlying neoplasm will affect symptoms favorably.94

The therapist should consider it a red flag whenever someone does not improve with physical therapy intervention. Failure to respond or worsening of symptoms requires a second screening examination. Progression of disease is often accompanied by a cluster of new signs and symptoms.

Extraovarian Primary Peritoneal Carcinoma: Extraovarian primary peritoneal carcinoma (EOPPC) is an abdominal cancer (peritoneal carcinomatosis) without ovarian involvement. It arises in the peritoneum and mimics the symptoms, microscopic appearance, and pattern of spread of endothelial ovarian cancer with no identifiable disease of the ovaries.96

EOPPC develops only in women and accounts for most extraovarian causes of symptoms with a presumed but inaccurate diagnosis of ovarian cancer.97 EOPPC has been reported after bilateral oophorectomy performed for benign disease or prophylaxis.98 The occurrence of EOPPC with the same histology as neoplasms arising within the ovary may be explained by the common origin of the peritoneum and the ovaries from the coelomic epithelium.99

Cervical Cancer: Cancer of the cervix is the third most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States. It is the most common cause of death from gynecologic cancer in the world. Since the widespread introduction of the Papanicolaou (Pap) smear as a standard screening tool, the diagnosis of cervical cancer at the invasive stage has decreased significantly. Even so, nearly half of all women diagnosed with cervical cancer are diagnosed at a late stage, with locally or regionally advanced disease and a poor prognosis.79

At the same time that rates of invasive cervical carcinoma have been on the decline, the highly curable preinvasive carcinoma in situ (CIS) has increased. CIS is more common in women 30 to 40 years of age, and invasive carcinoma is more frequent in women over age 40 years.

Risk Factors: Risk factors associated with the development of cervical cancer are many and varied and include the following:

• Early age at first sexual intercourse

• Early age at first pregnancy

• Tobacco use, including exposure to passive smoke100

• Low socioeconomic status (lack of screening)

• History of any STD, especially human papillomavirus (HPV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

• History of multiple sex partners

• History of childhood sexual abuse

• Women whose mothers used the drug diethylstilbestrol (DES) during pregnancy

Research into the health effects of intimate partner abuse points to a higher risk of STD and prevention of women from seeking health care; both contribute to an increased risk of cervical cancer.101 Women with a past history of childhood sexual abuse may avoid regular gynecologic care because being examined triggers painful memories. A history of childhood sexual abuse also increases a woman’s risk of exposure to STIs that may contribute to the development of cervical cancer.101

The American Cancer Society (ACS) has issued updated recommendations for the early detection of cervical cancer.102,103 The ACS advises all women to start cervical cancer screening 3 years after beginning to have vaginal intercourse, but no later than age 21. Pap smears should be done regularly, usually every year. After a total hysterectomy (including removal of the cervix) or after age 70, the Pap smear is discontinued.104

In the normal healthy adult female age 30 years or older, after three negative annual examinations, the Pap may be performed less frequently at the advice of the physician. Women with certain risk factors for cervical cancer (e.g., HIV infection, long-term steroid use, immunocompromised status, DES exposure before birth) should be advised to have an annual Pap smear.102,104

Clinical Signs and Symptoms: Early cervical cancer has no symptoms. Clinical symptoms related to advanced disease include painful intercourse; postcoital, coital, or intermenstrual bleeding; and a watery, foul-smelling vaginal discharge.

Disease usually spreads by local extension and through the lymphatics to the retroperitoneal lymph nodes (see Table 13-4). Metastases to the central nervous system can occur hematogenously late in the course of the disease and are generally rare. Clinical presentation of brain metastases depends on the site of the metastasized lesion; hemiparesis and headache are the most commonly reported signs and symptoms.105

Screening for Gastrointestinal Causes of Pelvic Pain

GI conditions can cause pelvic pain. The most common causes of pelvic pain referred from the GI system are the following:

The small bowel, sigmoid, and rectum can be affected by gynecologic disease; abdominal, low back, and/or pelvic pain may result from pressure or displacement of these organs. Swelling, reaction to an adjacent infection, or reaction to the spilling of blood, menstrual fluid, or infected material into the abdominal cavity can cause pressure or displacement.

Bowel function is usually altered, but sometimes, the client experiences periods of normal bowel function alternating with intermittent bowel symptoms, and the client does not see a pattern or relationship until asked about current (or recent) changes in bowel function.

For all of these conditions, the symptoms as seen or reported in a physical therapy practice are usually the same. The client may present with one or more of the following:

• GI symptoms (see Box 4-19)

• Symptoms aggravated by increased abdominal pressure (coughing, straining, lifting, bending)

• Iliopsoas abscess (see Figs. 8-3 through Fig. 8-7; a positive test is indicative of an inflammatory/infectious process)

• Positive McBurney’s point (see Figs. 8-9 and 8-10; appendicitis)

• Rebound tenderness or Blumberg’s sign (see Fig. 8-12; appendicitis or peritonitis)